Abstract

The cubic B20 compound FeGe, which exhibits a near room temperature skyrmion phase, is of great importance not only for fundamental physics such as nonlinear magnetic ordering and solitons but also for future application of skyrmion states in spintronics. In this work, the critical behavior of the cubic FeGe is investigated by means of bulk dc-magnetization. We obtain the critical exponents (β = 0.336 ± 0.004, γ = 1.352 ± 0.003 and β = 5.276 ± 0.001), where the self-consistency and reliability are verified by the Widom scaling law and scaling equations. The magnetic exchange distance is found to decay as  r−4.9, which is close to the theoretical prediction of 3D-Heisenberg model (r−5). The critical behavior of FeGe indicates a short-range magnetic interaction. Meanwhile, the critical exponents also imply an anisotropic magnetic coupling in this system.

r−4.9, which is close to the theoretical prediction of 3D-Heisenberg model (r−5). The critical behavior of FeGe indicates a short-range magnetic interaction. Meanwhile, the critical exponents also imply an anisotropic magnetic coupling in this system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recently years, skyrmion state, which is a topologically protected nanoscale vortex-like spin structure, has attracted great interest due to its potential application in spintronic storage function1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. It has been demonstrated that the skyrmion phase is thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex state in magnetic crystals13,14. In addition, writing and deleting single magnetic skyrmion have been realized in PdFe bilayer on Ir(111) surface15,16. These findings pave a significant path to design quantum-effect devices based on the tunable skyrmion dynamics. The room-temperature skyrmion materials hosting stable skrymion phase are paid considerable attention17. The cubic FeGe belongs to the space group  , in which the non-centrosymmetric cell results in a weak Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interaction. The competition of DM interaction between the much stronger ferromagnetic exchange finally causes a long modulation period of a helimagnetic ground state1,2,18. A bulk FeGe sample exhibits a long-range magnetic order at Curie temperature TC = 278.2 K and displays a complex succession of temperature-driven crossovers in the vicinity of TC19,20. The skyrmion phase emerges in a narrow temperature range just below TC in the filed range from 0.15 to 0.4 kOe. The existence of the near room temperature skyrmion phase in FeGe, to our knowledge the highest TC in B20 skyrmion compounds, makes it one of the most promising candidate of the next generation spintronic devices. Recently, more stable skyrmion phase has been realized in FeGe thin film and it has been claimed that the skyrmions can be tuned by the crystal lattice21,22,23. On the other hand, multiple and complex magnetic interactions have also been found in FeGe. An inhomogeneous helimagnetic state has been discovered above TC due to the strong precursor phenomena19,24. More interestingly, it has been revealed that the helical axis (q-vector direction) orientates depending on temperature. At zero magnetic field, the helical axis is along the

, in which the non-centrosymmetric cell results in a weak Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interaction. The competition of DM interaction between the much stronger ferromagnetic exchange finally causes a long modulation period of a helimagnetic ground state1,2,18. A bulk FeGe sample exhibits a long-range magnetic order at Curie temperature TC = 278.2 K and displays a complex succession of temperature-driven crossovers in the vicinity of TC19,20. The skyrmion phase emerges in a narrow temperature range just below TC in the filed range from 0.15 to 0.4 kOe. The existence of the near room temperature skyrmion phase in FeGe, to our knowledge the highest TC in B20 skyrmion compounds, makes it one of the most promising candidate of the next generation spintronic devices. Recently, more stable skyrmion phase has been realized in FeGe thin film and it has been claimed that the skyrmions can be tuned by the crystal lattice21,22,23. On the other hand, multiple and complex magnetic interactions have also been found in FeGe. An inhomogeneous helimagnetic state has been discovered above TC due to the strong precursor phenomena19,24. More interestingly, it has been revealed that the helical axis (q-vector direction) orientates depending on temperature. At zero magnetic field, the helical axis is along the  direction below 280 K. With decreasing temperature, it changes to the

direction below 280 K. With decreasing temperature, it changes to the  direction at 211 K20.

direction at 211 K20.

In view of the potential application and abundant physics in FeGe, a deep investigation of its magnetic exchange is of great importance not only for fundamental physics such as nonlinear magnetic ordering and solitons but also for creation of a basic for future application of skyrmion states and other chiral modulations in spintronics. In this work, the critical behavior of FeGe has been investigated by means of bulk dc-magnetization. The critical exponents ( ,

,  and

and  ) are obtained, where the self-consistency and reliability are verified by the Widom scaling law and the scaling equations. These critical behavior of FeGe indicates a short-range magnetic interaction with a magnetic exchange distance decaying as

) are obtained, where the self-consistency and reliability are verified by the Widom scaling law and the scaling equations. These critical behavior of FeGe indicates a short-range magnetic interaction with a magnetic exchange distance decaying as  . The obtained critical exponents also imply an anisotropic magnetic coupling in FeGe system.

. The obtained critical exponents also imply an anisotropic magnetic coupling in FeGe system.

Results and Discussion

It is well known that the critical behavior for a second-order phase transition can be investigated through a series of critical exponents. In the vicinity of the critical point, the divergence of correlation length  leads to universal scaling laws for the spontaneous magnetization MS and initial susceptibility

leads to universal scaling laws for the spontaneous magnetization MS and initial susceptibility  . Subsequently, the mathematical definitions of the exponents from magnetization are described as25,26:

. Subsequently, the mathematical definitions of the exponents from magnetization are described as25,26:

where  is the reduced temperature;

is the reduced temperature;  and D are the critical amplitudes. The parameters β (associated with

and D are the critical amplitudes. The parameters β (associated with  ), γ (associated with

), γ (associated with  ) and

) and  (associated with TC) are the critical exponents. Universally, in the asymptotic critical region

(associated with TC) are the critical exponents. Universally, in the asymptotic critical region  , these critical exponents should follow the Arrott-Noakes equation of state27:

, these critical exponents should follow the Arrott-Noakes equation of state27:

Therefore, the critical exponents β and γ can be obtained by fitting the  and

and  curves using the modified Arrott plot of

curves using the modified Arrott plot of  vs

vs  . Meanwhile, δ can be generated directly by the

. Meanwhile, δ can be generated directly by the  at the critical temperature TC according to Eq. (3).

at the critical temperature TC according to Eq. (3).

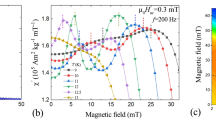

Generally, the critical temperature TC can be roughly determined by the temperature dependence of magnetization [ ]. Figure 1(a) shows the

]. Figure 1(a) shows the  curves for FeGe under zero-field-cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) with an applied field H = 100 Oe. The

curves for FeGe under zero-field-cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) with an applied field H = 100 Oe. The  curves exhibit an abrupt decline with the increase of temperature, corresponding to the paramagnetic-helimagnetic (PM-HM) transition. A sharp peak is observed at T = 278.5 K. The inset of Fig. 1(a) gives

curves exhibit an abrupt decline with the increase of temperature, corresponding to the paramagnetic-helimagnetic (PM-HM) transition. A sharp peak is observed at T = 278.5 K. The inset of Fig. 1(a) gives  vs T, where TC ≈ 283 K is determined from the minimum of the

vs T, where TC ≈ 283 K is determined from the minimum of the  curve. Wilhelm et al. has demonstrated that a long-rang magnetic order occurs below 278.2 K, however, an inhomogeneous helical state has existed above that temperature due to the strong precursor phenomena19,28. The higher TC determined here indicates the appearance of precursor phenomena which may be caused by the strong spin fluctuation24. Figure 1(b) shows the isothermal magnetization

curve. Wilhelm et al. has demonstrated that a long-rang magnetic order occurs below 278.2 K, however, an inhomogeneous helical state has existed above that temperature due to the strong precursor phenomena19,28. The higher TC determined here indicates the appearance of precursor phenomena which may be caused by the strong spin fluctuation24. Figure 1(b) shows the isothermal magnetization  at 4 K, which exhibits a typical magnetic ordering behavior. The inset of Fig. 1(b) plot the magnified

at 4 K, which exhibits a typical magnetic ordering behavior. The inset of Fig. 1(b) plot the magnified  in lower field regime, which shows that the saturation field HS ≈ 3000 Oe. No magnetic hysteresis is found on the

in lower field regime, which shows that the saturation field HS ≈ 3000 Oe. No magnetic hysteresis is found on the  curve, indicating no coercive force for FeGe.

curve, indicating no coercive force for FeGe.

Usually, the critical exponents can be determined by the Arrott plot. For the Landau mean-field model with  and

and  29, the Arrott-Noakes equation of state evolves into

29, the Arrott-Noakes equation of state evolves into  , the so called Arrott equation. In order to construct an Arrot plot, the isothermal magnetization curves

, the so called Arrott equation. In order to construct an Arrot plot, the isothermal magnetization curves  around TC are measured as shown in Fig. 2(a). The Arrott plot of M2 vs

around TC are measured as shown in Fig. 2(a). The Arrott plot of M2 vs  for FeGe is depicted in Fig. 2(b). According to the Banerjee’s criterion, the slope of line in the Arrott plot indicates the order of the phase transition: negative slope corresponds to first-order transition while positive to second-order one30. Therefore, the Arrott plot of FeGe implies a second-order phase transition, in agreement with the specific heat measurement28. According to the Arrott plot, the M2 vs

for FeGe is depicted in Fig. 2(b). According to the Banerjee’s criterion, the slope of line in the Arrott plot indicates the order of the phase transition: negative slope corresponds to first-order transition while positive to second-order one30. Therefore, the Arrott plot of FeGe implies a second-order phase transition, in agreement with the specific heat measurement28. According to the Arrott plot, the M2 vs  generally present a series of parallel straight lines around TC, where

generally present a series of parallel straight lines around TC, where  vs. M2 at TC just pass through the origin31. One can see that all M2 vs

vs. M2 at TC just pass through the origin31. One can see that all M2 vs  curves show quasi-straight lines with positive slopes in high field range. However, all lines show an upward curvature and are not parallel to each other, indicating that the

curves show quasi-straight lines with positive slopes in high field range. However, all lines show an upward curvature and are not parallel to each other, indicating that the  and

and  within the framework of Landau mean-field model is unsatisfied. Therefore, a modified Arrott plot should be employed.

within the framework of Landau mean-field model is unsatisfied. Therefore, a modified Arrott plot should be employed.

Four kinds of possible exponents belonging to the 3D-Heisenberg model  ,

,  , 3D-Ising model

, 3D-Ising model  ,

,  , 3D-XY model

, 3D-XY model  ,

,  and tricritical mean-field model

and tricritical mean-field model  ,

,  29,32 are used to construct the modified Arrott plots, as shown in Fig. 3 (a–d). All these four constructions exhibit quasi-straight lines in the high field region33,34,35. Apparently, the lines in Fig. 3(d) are not parallel to each other, indicating that the tricritical mean-field model is not satisfied. However, all lines in Fig. 3(a–c) are almost parallel to each other. To determine an appropriate model, the modified Arrott plots should be a series of parallel lines in the high field region with the same slope, where the slope is defined as

29,32 are used to construct the modified Arrott plots, as shown in Fig. 3 (a–d). All these four constructions exhibit quasi-straight lines in the high field region33,34,35. Apparently, the lines in Fig. 3(d) are not parallel to each other, indicating that the tricritical mean-field model is not satisfied. However, all lines in Fig. 3(a–c) are almost parallel to each other. To determine an appropriate model, the modified Arrott plots should be a series of parallel lines in the high field region with the same slope, where the slope is defined as  . The normalized slope (NS) is defined as

. The normalized slope (NS) is defined as  , which enables us to identify the most suitable model by comparing the NS with the ideal value of ‘1’33. Plots of NS vs T for the four different models are shown in Fig. 4. One can see that the NS of 3D-Heisenberg model is close to ‘1’ mostly above TC, while that of 3D-Ising model is the best below TC. This result indicates that the critical behavior of FeGe may not belong to a single universality class.

, which enables us to identify the most suitable model by comparing the NS with the ideal value of ‘1’33. Plots of NS vs T for the four different models are shown in Fig. 4. One can see that the NS of 3D-Heisenberg model is close to ‘1’ mostly above TC, while that of 3D-Ising model is the best below TC. This result indicates that the critical behavior of FeGe may not belong to a single universality class.

The precise critical exponents β and γ should be achieved by the iteration method36. The linear extrapolation from the high field region to the intercepts with the axes  and

and  yields reliable values of

yields reliable values of  and

and  , which are plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 5(a). By fitting to Eqs. (1) and (2), one obtains a set of β and γ. The obtained β and γ are used to reconstruct a new modified Arrott plot. Consequently, new

, which are plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 5(a). By fitting to Eqs. (1) and (2), one obtains a set of β and γ. The obtained β and γ are used to reconstruct a new modified Arrott plot. Consequently, new  and

and  are generated from the linear extrapolation from the high field region. Therefore, another set of β and γ can be yielded. This procedure is repeated until β and γ do not change. As one can see, the obtained critical exponents by this method are independent on the initial parameters, which confirms these critical exponents are reliable and intrinsic. In this way, it is obtained that

are generated from the linear extrapolation from the high field region. Therefore, another set of β and γ can be yielded. This procedure is repeated until β and γ do not change. As one can see, the obtained critical exponents by this method are independent on the initial parameters, which confirms these critical exponents are reliable and intrinsic. In this way, it is obtained that  with

with  and

and  with

with  for FeGe. The critical temperature TC from the modified Arrott plot is in agreement with that obtained from the derivative

for FeGe. The critical temperature TC from the modified Arrott plot is in agreement with that obtained from the derivative  curve, indicating strong critical fluctuation before the formation of the long-range ordering in FeGe24. This critical fluctuation is in agreement with the precursor phenomenon reported by Wilhelm et al.28. The modulated precursor states and complexity of the magnetic phase diagram near the magnetic ordering are explained by the change of the character of solitonic inter-core interactions and the onset of specific confined chiral modulations19,28.

curve, indicating strong critical fluctuation before the formation of the long-range ordering in FeGe24. This critical fluctuation is in agreement with the precursor phenomenon reported by Wilhelm et al.28. The modulated precursor states and complexity of the magnetic phase diagram near the magnetic ordering are explained by the change of the character of solitonic inter-core interactions and the onset of specific confined chiral modulations19,28.

Figure 5(b) shows the isothermal magnetization  at the critical temperature

at the critical temperature  K, with the inset plotted on a

K, with the inset plotted on a  scale. One can see that the

scale. One can see that the  at TC exhibits a straight line on a

at TC exhibits a straight line on a  scale for

scale for  . We determine that

. We determine that  in the high field region

in the high field region  . According to the statistical theory, these critical exponents should fulfill the Widom scaling law37:

. According to the statistical theory, these critical exponents should fulfill the Widom scaling law37:

As a result,  is calculated according to the Widom scaling law, in agreement with the results from the experimental critical isothermal analysis. The self-consistency of the critical exponents demonstrates that they are reliable and unambiguous.

is calculated according to the Widom scaling law, in agreement with the results from the experimental critical isothermal analysis. The self-consistency of the critical exponents demonstrates that they are reliable and unambiguous.

Finally, these critical exponents should obey the scaling equations. Two different constructions have been used in this work, both of which are based on the scaling equations of state. According to the scaling equations, in the asymptotic critical region, the magnetic equation is written as25:

where  are regular functions denoted as

are regular functions denoted as  for

for  and

and  for

for  . Defining the renormalized magnetization as

. Defining the renormalized magnetization as  and the renormalized field as

and the renormalized field as  , the scaling equation indicates that m vs h forms two universal curves for

, the scaling equation indicates that m vs h forms two universal curves for  and

and  respectively38,39. Based on the scaling equation

respectively38,39. Based on the scaling equation  , the isothermal magnetization around TC for FeGe is replotted in Fig. 6(a), where all experimental data collapse onto two universal branches. The inset of Fig. 6(a) shows he m2 vs

, the isothermal magnetization around TC for FeGe is replotted in Fig. 6(a), where all experimental data collapse onto two universal branches. The inset of Fig. 6(a) shows he m2 vs  , where all

, where all  curves should collapse onto two independent universal curves. In addition, the scaling equation of state takes another form25,38:

curves should collapse onto two independent universal curves. In addition, the scaling equation of state takes another form25,38:

where  is the scaling function. Based on Eq. (7), all experimental curves will collapse onto a single curve. Figure 6(b) shows the

is the scaling function. Based on Eq. (7), all experimental curves will collapse onto a single curve. Figure 6(b) shows the  vs

vs  for FeGe, where the experimental data collapse onto a single curve and TC locates at the zero point of the horizontal axis. The well-rescaled curves further confirm the reliability of the obtained critical exponents.

for FeGe, where the experimental data collapse onto a single curve and TC locates at the zero point of the horizontal axis. The well-rescaled curves further confirm the reliability of the obtained critical exponents.

The obtained critical exponents of FeGe and other related materials, as well as those from different theoretical models are summarized in Table 1 for comparison. One can see that the critical exponent γ of FeGe is close to that of 3D-Heisenberg model, while β approaches to that of 3D-Ising or 3D-XY mode, indicating that the critical behavior of FeGe do not belong to a single universality class. Anyhow, all these three models indicate a short-range magnetic coupling, implying the existence of short-range magnetic interaction in FeGe. As we know, for a homogeneous magnet, the universality class of the magnetic phase transition depends on the exchange distance  . M. E. Fisher et al. have treated this kind of magnetic ordering as an attractive interaction of spins, where a renormalization group theory analysis suggests

. M. E. Fisher et al. have treated this kind of magnetic ordering as an attractive interaction of spins, where a renormalization group theory analysis suggests  decays with distance r as40,41:

decays with distance r as40,41:

where d is the spatial dimensionality and σ is a positive constant. Moreover, there is41,42:

where  and

and  , n is the spin dimensionality. For a three dimensional material (d = 3), we have

, n is the spin dimensionality. For a three dimensional material (d = 3), we have  . When

. When  , the Heisenberg model (

, the Heisenberg model ( ,

,  and

and  ) is valid for the three dimensional isotropic magnet, where

) is valid for the three dimensional isotropic magnet, where  decreases faster than r−5. When

decreases faster than r−5. When  , the mean-field model

, the mean-field model  ,

,  and

and  is satisfied, expecting that

is satisfied, expecting that  decreases slower than

decreases slower than  . From Eq. (9)

. From Eq. (9)  is generated for FeGe, thus close to the short-range magnetic coupling of

is generated for FeGe, thus close to the short-range magnetic coupling of  . Subsequently, it is found that the magnetic exchange distance decays as

. Subsequently, it is found that the magnetic exchange distance decays as  , which indicates that the magnetic coupling in FeGe is close to a short-range interaction. Moreover, we get the correlation length critical exponent

, which indicates that the magnetic coupling in FeGe is close to a short-range interaction. Moreover, we get the correlation length critical exponent  (where

(where  ,

,  ) and

) and  ± 0.008. Theory gives that

± 0.008. Theory gives that  for 3D-Heisenberg model and

for 3D-Heisenberg model and  for 3D-Ising model43,44. Therefore, these critical exponents indicates that the critical behavior in FeGe is close to the 3D-Heisenberg model with short-range magnetic coupling. However, the discrepancy of the critical exponents to 3D-Ising or 3D-XY models indicates an anisotropic magnetic exchange interaction.

for 3D-Ising model43,44. Therefore, these critical exponents indicates that the critical behavior in FeGe is close to the 3D-Heisenberg model with short-range magnetic coupling. However, the discrepancy of the critical exponents to 3D-Ising or 3D-XY models indicates an anisotropic magnetic exchange interaction.

As can be seen from Table 1, the critical exponents of Fe0.8Co0.2Si and Cu2OSeO3, which also exhibit a helimagnetic and skyrmion phase transition with similar crystal symmetry, are close to the universality class of the 3D-Heisenberg model45,46, indicating a isotropic short-range magnetic coupling. However, the critical behavior of MnSi belongs to the tricritical mean field model47,48. In macroscopic view, the magnetic ordering in cubic FeGe is a DM spiral similar to the structure observed in the isostructural compound MnSi49. However, in microscopic view, the magnetic coupling types in these two helimagnets are different. The critical behavior of FeGe is roughly similar to those of Fe0.8Co0.2Si or Cu2OSeO3, except a magnetic exchange anisotropy. In MnSi the spiral propagates are along equivalent  directions at all temperatures below

directions at all temperatures below  K. However, it has been revealed that the helical axis (q−vector direction) in FeGe depends on temperature. It is along the

K. However, it has been revealed that the helical axis (q−vector direction) in FeGe depends on temperature. It is along the  direction below 280 K and changes to the

direction below 280 K and changes to the  direction in a lower temperature range at 211 K with the decrease of temperature at zero magnetic field20. This unique change of helical axis in FeGe may be correlated with the anisotropy of magnetic exchange in this system, since the magnetic exchange anisotropy also plays an important role in determination of the spin ordering direction. In addition, it should be expounded that the magnetic exchange anisotropy is essentially different from the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. The magnetocrystalline anisotropy is correlated to the crystal structure, while magnetic exchange anisotropy originates from the anisotropic magnetic exchange coupling

direction in a lower temperature range at 211 K with the decrease of temperature at zero magnetic field20. This unique change of helical axis in FeGe may be correlated with the anisotropy of magnetic exchange in this system, since the magnetic exchange anisotropy also plays an important role in determination of the spin ordering direction. In addition, it should be expounded that the magnetic exchange anisotropy is essentially different from the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. The magnetocrystalline anisotropy is correlated to the crystal structure, while magnetic exchange anisotropy originates from the anisotropic magnetic exchange coupling  .

.

Conclusion

In summary, the critical behavior of the near room temperature skyrmion material FeGe has been investigated around TC. The reliable critical exponents ( ,

,  and

and  ) are obtained, which are verified by the Widom scaling law and scaling equations. The magnetic exchange distance is found to decay as

) are obtained, which are verified by the Widom scaling law and scaling equations. The magnetic exchange distance is found to decay as  , which is close to that of 3D-Heisenberg model (r−5). The critical behavior indicate that the magnetic interaction in FeGe is of short-range type with an anisotropic magnetic exchange coupling.

, which is close to that of 3D-Heisenberg model (r−5). The critical behavior indicate that the magnetic interaction in FeGe is of short-range type with an anisotropic magnetic exchange coupling.

Methods

A polycrystalline B20-type FeGe sample was synthesized with a cubic anvil-type high-pressure apparatus. The detailed preparing method was described elsewhere and the physical properties were carefully checked [H. Du. et al., Nat. Commun. 6, 8504 (2015)]. The chemical compositions were determined by the Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) Spectrometry as shown in Fig. S1 and Table SI, which shows the atomic ratio of Fe : Ge ≈ 50.52: 49.48. The magnetization was measured using a Quantum Design Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (SQUID-VSM). The no-overshoot mode was applied to ensure a precise magnetic field. To minimize the demagnetizating field, the sample was processed into slender ellipsoid shape and the magnetic field was applied along the longest axis. In addition, the isothermal magnetization was performed after the sample was heated well above  for 10 minutes and then cooled under zero field to the target temperatures to make sure curves were initially magnetized. The magnetic background was carefully subtracted. The applied magnetic field

for 10 minutes and then cooled under zero field to the target temperatures to make sure curves were initially magnetized. The magnetic background was carefully subtracted. The applied magnetic field  has been corrected into the internal field as

has been corrected into the internal field as  (where M is the measured magnetization and N is the demagnetization factor) [A. K. Pramanik et al., Phys. Rev. B 79, 214426 (2009)]. The corrected H was used for the analysis of critical behavior.

(where M is the measured magnetization and N is the demagnetization factor) [A. K. Pramanik et al., Phys. Rev. B 79, 214426 (2009)]. The corrected H was used for the analysis of critical behavior.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhang, L. et al. Critical phenomenon of the near room temperature skyrmion material FeGe. Sci. Rep. 6, 22397; doi: 10.1038/srep22397 (2016).

References

Roβler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature (London) 442, 797–801 (2006).

Muuhlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Munzer, W. et al. Skyrmion lattice in the doped semiconductor Fe1−xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 81, 041203 (2010).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature (London) 465, 901–904 (2010).

Seki, S., Yu, X. Z., Ishiwata, S. & Tokura, Y. Observation of skyrmions in a multiferroic material. Science 336, 198–201 (2012).

Du, H. F., Ning, W., Tian, M. L. & Zhang, Y. H. Field-driven evolution of chiral spin textures in a thin helimagnet nanodisk. Phys. Rev. B 87, 014401 (2013).

Neubauer, A. et al. Topological Hall effect in the A phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186602 (2009).

Du, H. F. et al. Highly stable skyrmion state in helimagnetic MnSi nanowires. Nano Lett. 14, 2026–2032 (2014).

Nagaosa N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Jonietz, F. et al. Spin transfer torques in MnSi at ultralow current densities. Science 330, 1648–1651 (2010).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 152–156 (2013).

White, J. S. et al. Electric-field-induced skyrmion distortion and giant lattice rotation in the magnetoelectric insulator Cu2OseO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 107203 (2014).

Bogdanov, A. & Yablonsky, D. Thermodynamically stable vortexes in magnetically ordered crystals-mixed state of magnetics. Sov. Phys. JETP 96, 253 (1989).

Bogdanov, A. & Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 138, 255–269 (1994).

Romming, N. et al. Writing and deleting single magnetic skyrmions. Science 341, 636–639 (2013).

Romming, N., Kubetzka, A., Hanneken, C., von Bergmann, K. & Wiesendanger, R. Field-dependent size and shape of single magnetic skyrmions. Phy. Rev. Lett. 114, 177203 (2015).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Skyrmion flow near room temperature in an ultralow current density. Nat. Commun. 3, 988 (2012).

Bak, P. & Jensen, M. H. Theory of helical magnetic structures and phase transitions in MnSi and FeGe. J. Phys. C: Solid St. Phys. 13, L881 (1980).

Wilhelm, H. et al. Precursor phenomena at the magnetic ordering of the cubic helimagnet FeGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127203 (2011).

Lebech, B., Bernhard, J. & Freltoft, T. Magnetic structures of cubic FeGe studied by small-angle neutron scattering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1, 6105–6122 (1989).

Yu, X. Z. et al. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mater. 10, 106–109 (2011).

Shibata, K. et al. Large anisotropic deformation of skyrmions in strained crystal. Nat. Naonotechol. 10, 589–592 (2015).

Koretsune, T., Nagaosa, N. & Arita, R. Control of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in Mn1−xFexGe: a first-principles study. Sci. Rep. 5, 13302 (2015).

Barla, A. et al. Pressure-induced inhomogeneous chiral-spin ground state in FeGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 016803 (2015).

Stanley, H. E. Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena (Oxford University Press, London, 1971).

Fisher, M. E. The theory of equilibrium critical phenomena. Rep. Prog. Phys. 30, 615–730 (1967).

Arrott, A. & Noakes, J. Approximate equation of state for Nickel near its critical temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 786 (1967).

Wilhelm, H. et al. Confinement of chiral magnetic modulations in the precursor region of FeGe. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 294204 (2012).

Kaul, S. N. Static critical phenomena in ferromagnets with quenched disorder. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 53, 5–53 (1985).

Banerjee, S. K. On a generalised approach to first and second order magnetic transitions. Phys. Lett. 12, 16–17 (1964).

Arrott, A. Criterion for ferromagnetism from observations of magnetic isotherms. Phys. Rev. 108, 1394–1396 (1957).

Huang, K. Statistical Mechanics 2nd ed. (Wiley, New York, 1987).

Fan, J. Y. et al. Critical properties of the perovskite manganite La0.1Nd0.6Sr0.3MnO3 . Phys. Rev. B 81, 144426 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Critical behavior in the antiperovskite ferromagnet AlCMn3 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 104419 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Critical properties of the 3D-Heisenberg ferromagnet CdCr2Se4 . Europhys. Lett. 91, 57001 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Critical behavior of single crystal CuCr2Se4−x Brx (x = 0.25). Appl. Phys. A 113, 201–206 (2013).

Kadanoff, L. P. Scaling laws for Ising models near TC . Physics 2, 263–272 (1966).

Phan, M. H. et al. Tricritical point and critical exponents of La0.7Ca0.3−xSrxMnO3 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.25) single crystals. J. Alloys Compd. 508, 238–244 (2010).

Khan, N. et al. Critical behavior in single-crystalline La0.67Sr0.33CoO3 . Phys. Rev. B 82, 064422 (2010).

Ghosh, K. et al. Critical phenomena in the double-exchange ferromagnet La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4740 (1998).

Fisher, M. E., Ma, S. K. & Nickel, B. G. Critical exponents for long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 29, 917–920 (1972).

Fischer, S. F., Kaul, S. N. & Kronmuller, H. Critical magnetic properties of disordered polycrystalline Cr75Fe25 and Cr70Fe30 alloys. Phys. Rev. B 65, 064443 (2002).

Fisher, M. E. The renormalization group in the theory of critical behavior. Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 597–616 (1974).

LeGuillou J. C. & Zinn-Justin, J. Critical exponents from eld theory. Phys. Rev. B 21, 3976–3998 (1980).

Jiang, W. J., Zhou, X. Z. & Williams, G. Scaling the anomalous Hall effect: A connection between transport and magnetism. Phys. Rev. B 82, 144424 (2010).

Zivkovic, I., White, J. S., Ronnow, H. M., Prsa, K. & Berger, H. Critical scaling in the cubic helimagnet Cu2OseO3 . Phys. Rev. B 89, 060401(R) (2014).

Bauer, A., Garst, M. & Pfleiderer, C. Specific heat of the skyrmion lattice phase and field-induced tricritical point in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 177207 (2013).

Zhang, L. et al. Critical behavior of the single-crystal helimagnet MnSi. Phys. Rev. B 91, 024403 (2015).

Bauer, A. & Pfleiderer, C. Magnetic phase diagram of MnSi inferred from magnetization and ac susceptibility. Phys. Rev. B 85, 214418 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the State Key Project of Fundamental Research of China through Grant No. 2011CBA00111, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 11574322, U1332140, 11004196, U1232142, 11474290, 11104281 and 11204288), the Foundation for Users with Potential of Hefei Science Center (CAS) through Grant No. 2015HSC-UP001 the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS No.2015267.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.Z. conducted the analyses. L.Z. conducted all of the experiments and wrote the paper. H.F.D., C.M.J. and W.S.W. synthesized the sample. H.H. collected the EDX spectrum. M.G. performed the magnetic measurements. J.Y.F., C.J.Z. and L.P. analyzed the experimental results.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Han, H., Ge, M. et al. Critical phenomenon of the near room temperature skyrmion material FeGe. Sci Rep 6, 22397 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22397

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22397

This article is cited by

-

An atomically tailored chiral magnet with small skyrmions at room temperature

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Origin of metamagnetism in skyrmion host Cu\(_2\)OSeO\(_3\)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Critical Phenomena and Estimation of Spontaneous Magnetization by Magnetic Entropy Analysis of La0.7Sr0.3Mn0.94Cu0.06O3

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2018)

-

Critical Behavior and Macroscopic Phase Diagram of the Monoaxial Chiral Helimagnet Cr1/3NbS2

Scientific Reports (2017)

] for FeGe under H = 100 Oe [the inset shows the derivative magnetization (

] for FeGe under H = 100 Oe [the inset shows the derivative magnetization ( ) vs T]; (b) the isothermal magnetization

) vs T]; (b) the isothermal magnetization  at 4 K (the inset gives the magnified region in the lower field regime).

at 4 K (the inset gives the magnified region in the lower field regime).

for FeGe; (b) Arrott plots of M2 vs

for FeGe; (b) Arrott plots of M2 vs  [the

[the  curves are measured at interval

curves are measured at interval  K and

K and  K when approaching TC].

K when approaching TC].

vs

vs  with (a) 3D-Heisenberg model; (b) 3D-Ising model; (c) 3D-XY model; and (d) tricritical mean-field model.

with (a) 3D-Heisenberg model; (b) 3D-Ising model; (c) 3D-XY model; and (d) tricritical mean-field model.

] as a function of temperature.

] as a function of temperature.

and χ0−1 for FeGe with the fitting solid curves; (b) the isothermal

and χ0−1 for FeGe with the fitting solid curves; (b) the isothermal  at TC with the inset plane on

at TC with the inset plane on  scale (the solid line is fitted).

scale (the solid line is fitted).

); (b) the rescaling of the the

); (b) the rescaling of the the  curves by

curves by  vs

vs  .

.