Abstract

Competitive interactions between species can be mitigated or even reversed in the presence of anthropogenic influences. The thrips species Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips tabaci are highly invasive and damaging agricultural pests throughout the world. Where the species co-occur, one species tends to eventually predominate over the other. Avermectin and beta-cypermethrin are commonly used insecticides to manage thrips in China, and laboratory bioassays demonstrated that F. occidentalis is significantly less susceptible than T. tabaci to these insecticides. In laboratory cage trials in which both species were exposed to insecticide treated cabbage plants, F. occidentalis became the predominant species. In contrast, T. tabaci completely displaced F. occidentalis on plants that were not treated with insecticides. In field trials, the species co-existed on cabbage before insecticide treatments began, but with T. tabaci being the predominant species. Following application of avermectin or beta-cypermethrin, F. occidentalis became the predominant species, while in plots not treated with insecticides, T. tabaci remained the predominant species. These results indicate that T. tabaci is an intrinsically superior competitor to F. occidentalis, but its competitive advantage can be counteracted through differential susceptibilities of the species to insecticides. These results further demonstrate the importance of external factors, such as insecticide applications, in mediating the outcome of interspecific interactions and produce rapid unanticipated shifts in the demographics of pest complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High competitive ability is believed to be an important characteristic of invasive species1. Many researchers have demonstrated the competitive superiority of an invading species by comparing its competitive abilities with those of a native species that is being displaced2,3,4,5. The coexistence of an invasive species and native species is rarely stable, with one species typically displacing the other within a relatively short period of time1. Although interspecific competition is major factor in displacements, other ecological mechanisms contribute to displacements.

Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) is native to western North America but in the last 30 years, has become a worldwide invasive pest6,7. This species has become the dominant phytophagous thrips in many of the regions it has invaded, including Japan8, Spain9, Turkey10 and Argentina11. In European greenhouses, F. occidentalis has replaced Thrips tabaci Lindeman as the major thrips pest. Van Rijn, Mollena & Steehuis-Broers12 suggest that F. occidentalis is a superior competitor, after finding no difference between the two species in either the intrinsic rate of increase, net reproductive time, or development times. More recently, Northfield et al.13 showed that F. occidentalis is competitively superior to F. bispinosa (Morgan), a common thrips species of southern Florida, USA. In contrast, Paini et al.14 showed that the invasive F. occidentalis appears to be competitively excluded by the native F. tritici (Fitch), and they suggest that the likely mechanism of competition between the two species was interference rather than exploitative competition. In China, F. occidentalis was first found in Beijing in 2003, and has since spread throughout China15. By 2014, F. occidentalis was found in more than 10 provinces throughout China16, where it has rapidly become a significant horticultural pest.

Thrips tabaci is native to southern Asia, and can occur at high densities resulting in significant damage to crops15. Currently, this species is still an important pest thrips throughout vegetable growing regions of China. Although T. tabaci and F. occidentalis share many of the same host crops, and co-exist in some crops and regions, interspecific interactions between them remain unclear. F. occidentalis is largely absent or occurs in low numbers in some regions, where the native T. tabaci predominates15. In contrast, T. tabaci is largely absent or occurs in low numbers in some regions where the invasive F. occidentalis has become predominant15. It is possible that external factors determine which species competitively excludes the other from a particular region.

One factor that can mediate competitive interactions is the use of insecticides in cropping systems. Research has demonstrated that differential susceptibility to insecticides may increase the likelihood of one species being replaced by another, thus driving changes in population demographics17,18,19. Two of the most commonly applied insecticides for management of thrips in China are avermectin and beta-cypermethrin15. Using both laboratory and field experiments, we investigated interspecific differences in susceptibility to these insecticides and determined if differential susceptibility could explain the observed changes in thrips demographics.

Results

Baseline toxicity bioassays

Probit analyses showed that the respective lethal concentrations of both insecticides were significantly higher for F. occidentalis than for T. tabaci (Table 1). Control mortality was <5% in all replicates. Avermectin was significantly more toxic than beta-cypermethrin to T. tabaci. However based on the 95% confidence limits, the respective LC90 values were not significantly different from the recommended field rates of 1 ppm for avermectin and 5 ppm for beta-cypermethrin. Based on the susceptibility ratios, the differences between the species were greater for avermectin than for beta-cypermethrin. F. occidentalis was approximately 10 times less susceptible than T. tabaci to beta-cypermethrin (Table 1). The difference in susceptibility between the species to beta-cypermethrin was four fold greater than that for avermectin.

Thrips response to insecticides in laboratory experiments

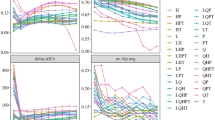

There was a significant interaction between insecticide treatments and time on the proportions of F. occidentalis (F = 9.88, df = 10, 30, P < 0.001). The proportions of F. occidentalis in the avermectin and beta-cypermethrin treatments were significantly greater than in the control treatment (F = 54.24, df = 2,6, P < 0.0001). This pattern was evident on each of the sample dates after the insecticide applications began (Fig. 1). Not only were the proportions of F. occidentalis in the insecticide treatments greater than those in the control treatment, the magnitude of the differences increased over time, which accounted for the significant insecticide treatment by time interaction. Despite being introduced at the initial population ratio of 1:1, there were significantly more T. tabaci in the control treatment by the second generation. T. tabaci completely displaced F. occidentalis by the sixth generation in the control treatment. However, this pattern was reversed when plants were treated with either avermectin or beta-cypermethrin. In those treatments, F. occidentalis became the dominant species and completely displaced T. tabaci after the fifth generation (Fig. 1.). However, there were no significant differences in the proportions of F. occidentalis between the avermectin and beta-cypermethrin treatments on any of the sample dates (Fig. 1).

Columns represent mean proportions and error bars represent standard error of the means. Means within the same date marked by different lower case letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 level according to least squares means procedures. Values on the x-axis denote generations of thrips following initial release of insects into cages. Insecticides were applied after the initial thrips release and following insect collections after the F1 and F2 generations.

Thrips response to insecticides in field experiments

The only thrips species collected in the field experiments were F. occidentalis and T. tabaci. Initially, T. tabaci was the predominant species at both locations, comprising 74 and 88% of adult thrips at Wucheng and Xiajin, respectively before the insecticide applications began (Figs 2 and 3). At Wucheng County, there was a significant interaction between insecticide treatments and time (F = 12.75, df = 10, 30, P < 0.0001). Although the proportions of F. occidentalis adults collected did not differ among the three treatments on the first sample date, which was before any insecticides were applied, the insecticide treatments significantly altered the relative abundance of F. occidentalis over the course of the experiment (F = 109.18, df = 2, 6, P < 0.0001). In the control treatment, the relative proportions of the species remained consistent over time and T. tabaci remained the predominant species (Fig. 2). However, there were increasingly greater proportions of F. occidentalis in the avermectin and beta-cypermethrin treatments on days 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 of the experiment (Fig. 2). By the end of the trial, the percentages of F. occidentalis in the avermectin and beta-cypermethrin treatments were approximately 93%, whereas it remained approximately 23% in the control treatment.

Columns represent mean proportions and error bars represent standard error of the means. Means within the same date marked by different lower case letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 level according to least squares means procedures. Sample dates listed on the x-axis denotes days after the initiation of the experiment. Insecticides were applied after the collection of thrips samples on days 1, 15 and 30 of the experiment.

Columns represent mean proportions and error bars represent standard error of the means. Means within the same date marked by different lower case letters are significantly different at P = 0.05 level according to least squares means procedures. Sample dates listed on the x-axis denotes days after the initiation of the experiment. Insecticides were applied after the collection of thrips samples on days 1, 15 and 30 of the experiment.

Similar patterns were evident in the field trial at Xiajin County. There was a significant interaction between insecticide treatment and time (F = 27.09, df = 10, 30, P < 0.0001). The composition of the thrips complex changed over time (F = 45.70, df = 10, 30, P < 0.0001), but the changes were consistent with time. T. tabaci was the predominant species at the beginning of the trial, comprising 88% of the thrips collected before insecticide applications began. T. tabaci remained the predominant species in the control treatment over the duration of the experiment, where its relative abundance increased from 86% to 97% at the conclusion of the trial (Fig. 3). An opposite trend occurred in the avermectin and beta-cypermethrin treatments. The relative abundance of F. occidentalis was significantly greater in the two insecticide treatments than in the control treatment (F = 155.74, df = 2, 6, P < 0.0001). The proportions of F. occidentalis adults differed between the insecticide treatments and the control treatment following the first insecticide application, and this difference increased over time, with the proportion of F. occidentalis exceeding 80% by the end of the trial. These results indicate that applications of avermectin and beta-cypermethrin reduced the abundance of T. tabaci relative to the abundance of F. occidentalis (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that T. tabaci is competitively superior to F. occidentalis on cabbage foliage in the absence of insecticides. However, the field and laboratory populations of F. occidentalis in our trials were significantly less susceptible to avermectin and beta-cypermethrin than were sympatric populations of T. tabaci. These differences in insecticide susceptibility could be driving the displacement of T. tabaci by F. occidentalis in agricultural settings, although T. tabaci currently is still the predominant thrips of horticultural crops in China, and avermectin and beta-cypermethrin have been used for thrips management for many years throughout China. These two insecticides constitute more than 40–60% of the insecticide use against thrips on horticultural crop growing regions, with avermectin being the predominant insecticide. The thrips populations that we used in our laboratory trials were collected from the same fields in Shandong Province. Consequently, they would have experienced similar insecticide exposures. Further, the field trials were conducted in areas where F. occidentalis and T. tabaci still co-occur, and thus those populations would have had similar histories of insecticide exposure.

Our laboratory cage experiments demonstrated that, in the absence of insecticides treatments, T. tabaci outcompeted F. occidentalis and completely displaced the invasive F. occidentalis in a very short time period. Cabbage has been shown to be a highly suitable host for both species when examined in single species trials20,21,22. However in mixed species trials, the reproductive capacity and ratio of females to males of F. occidentalis decreases significantly in the presence of T. tabaci22. Thus, the possible mechanisms responsible for competitive displacement of F. occidentalis by T. tabaci may include differential fecundity between the two species and differential larval survivorship on cabbage foliage.

The results of the laboratory cage show how the demographics of thrips populations can change rapidly in response to insecticide applications. Samples collected before the application of any insecticide indicated that the two species were present in near equal proportions for the three treatments. However, immediately after insecticide applications began, the proportion of F. occidentalis in the insecticide treatments increased. These changes were likely driven by the greater susceptibility of T. tabaci to avermectin and beta-cypermethrin. The field experiment further indicated that F. occidentalis was significantly more tolerant to avermectin and beta-cypermethrin than was T. tabaci, and such differences in susceptibility could be driving the displacement of T. tabaci by F. occidentalis. Frankliniella occidentalis tends to proliferate in vegetable crops in Florida, USA when broad-spectrum insecticides eliminate more susceptible competitor thrips species and predator species23. In that region, F. occidentalis becomes exceedingly rare on non-crop hosts outside of agricultural fields24,25.

Differential responses of insect populations to insecticides may not be limited to the toxic effects of the insecticides26,27. Our baseline toxicity bioassays showed that the LC90 values for T. tabaci were similar to the recommended field rates for avermectin and beta-cypermethrin, whereas the values were significantly higher for F. occidentalis, which suggests that F. occidentalis may have been subject to sublethal effects of the insecticides. Sublethal concentrations of insecticides may still have deleterious effects on survivors, including prolonging development times or reducing subsequent adult fecundity, as has been demonstrated for avermectin and beta-cypermethrin28,29. However, sublethal concentrations of insecticides may also induce positive effects on insect bionomics26,27. Sublethal concentrations of beta-cypermethrin lead to increased fecundity of Harmonia axyridis30. When treated with sublethal concentrations of avermectin as immatures, Panonychus citri have shorter generation doubling times and greater intrinsic growth rates than untreated immatures28.

However, the phenomenon of T. tabaci completely displacing F. occidentalis that occurred in the control treatment of our cage experiment was not observed in the field experiments. Although T. tabaci was a superior competitor to the invasive F. occidentalis on purple cabbage plants, competitive asymmetry alone may not result in the complete exclusion of a species on a single host. Frankliniella occidentalis may have colonized the untreated cabbage from other sources, including from the insecticide treated cabbage. Therefore, it is not surprising that F. occidentalis was still present in the control treatments in this field community, though at very low densities. Likewise, T. tabaci was not completely excluded in the insecticide treatment plots. This result may also reflect dispersal of T. tabaci into plots from outside sources, including the untreated cabbage. It also is possible that other biological mechanisms or anthropogenic factors operating in the open field conditions could influence competitive interactions between these species.

Differential susceptibility to insecticides has been linked to changes in other pest complexes. For example, in the USA, the spirea aphid, Aphis spireacola Patch has displaced A. pomi De Geer in apple (Malus domestica Borkh)31,32,33. These studies showed that A. spireacola is significantly less susceptible than A. pomi to a range of commonly used aphicides. Further, A. pomi is able to persist at low levels in the apple system because it is less likely to disperse from apple than is A. spireacola33. Exposure to sublethal doses of nitenpyram increases the susceptibility of Trialeurodes vaporariorum to other insecticides but it does not affect the susceptibility of Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius). This differential susceptibility to insecticides may have allowed B. tabaci to become the predominant whitefly species in northern China19. Similarly, the B biotype of B. tabaci has been displaced by the Q biotype in many regions has been attributed to the greater insecticide resistance of the Q biotype34,35. This displacement has occurred despite the fact that B biotype is a superior competitor36. Furthermore, the displacement of Liriomyza sativae Blanchard by Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess) in China and USA where has been attributed to the greater insecticide tolerance of L. trifolii17.

Given that we found T. tabaci were more sensitive than F. occidentalis to avemectin and beta-cypermethrin, changes in population demographics following insecticide applications would be expected to occur. These findings indicate the importance of accurate species identification in pest management programs. Continued use of either avermectin or beta-cypermethrin at the recommended rates could lead to apparent control failures in the field, especially in cases where F. occidentalis displaces T. tabaci because of differential insecticide susceptibility and become the predominant species in a growing region. The results of the current experiments indicate that differential susceptibility to insecticides may trigger the competitive exclusion of T. tabaci, with continued insecticide use accelerating the rate of displacement. Development of resistance to either of these two major insecticides used in China, would be problematic because of the lack of alternatives37. To help mitigate problems with either species, integrated pest management (IPM) programs that emphasize the conservation of biological control agents or use of microbial biopesticides should be implemented23,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

The results reported here provide evidence that T. tabaci is competitively superior to the invasive F. occidentalis, and in areas where T. tabaci currently predominates, it may be deter the establishment of large populations of F. occidentalis. However, the results reported here also provide evidence that the direction of species displacement between these thrips species can change due to their differential susceptibility to commonly used insecticides.

Methods

Insect strains and rearing

Populations of both F. occidentalis and T. tabaci were collected from purple cabbage, Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata, in Dezhou, Shandong Province, in June 2013. The field where thrips were collected was not treated with insecticides, but surrounding fields in the area did receive insecticide treatments. F. occidentalis and T. tabaci were reared separately on purple cabbage plants in the absence of insecticides at the Dezhou Agricultural Experiment Station under controlled conditions (25 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 10% RH, 16:8 h L:D). Thrips were reared for one generation before being used in experiments. T. tabaci were an all female thelytokous population. F. occidentalis were arrhenotokous, with a female-biased sex ratio (~75% female). Adult females of F. occidentalis are typically larger than those of T. tabaci although there is overlap in their sizes45.

Baseline toxicity bioassays

The bioassay technique used to determine differential susceptibility of F. occidentalis and T. tabaci to avermectin and beta-cypermethrin was similar to the adult bioassay methods described by Wang et al.46. Only recently eclosed (1 day post eclosion) adult females were used in bioassays. Each insecticide was serially diluted to 6–7 concentrations with distilled water containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Beijing Solar Bio Science and Technology Co. Ltd., China). Commercial formulations of avermectin and beta-cypermethrin insecticides (Hebei Veyong Bio-Chemical) were used in all trials. Leaves were cut from purple cabbage plants grown in a greenhouse without any insecticides, and then were dipped in the appropriate insecticide concentration for 10 s. Control leaves were treated in the same manner with a 0.1% Triton X-100 solution. Leaves were allowed to dry at room temperature for approximately 1 hour.

Modified ventilated glass cells were used as the bioassay chambers. A glass cell consisted of a center glass plate (4 mm thick) with two holes (20 mm diameter) drilled through the plate. The center glass plate was covered by a solid top and a bottom glass plate. The three plates were kept together with strong rubber bands forming two cells. Two ventilation holes were drilled opposite each other in the sides of the plate into the cell. The holes were covered inside the cell by copper wire screen with a mesh size of 200 μm.

After air-drying, each leaf was placed with its adaxial surface downward onto filter paper. The leaf and filter paper were placed individually between the center and bottom glass of a plate. Thrips were then introduced into the cells with the experimental leaves. Thirty adult female thrips were moved into each cell with an aspirator. Three cells were prepared for each concentration (total 90 adult thrips for each concentration) and kept under the environmental conditions described above. Mortality was recorded 48 h later. Thrips unable to move and showing characteristic effects of insecticide intoxication were scored as dead.

The data from these insecticide toxicity assays were subjected to probit analysis using POLO-PC (LeOra Software, Berkeley, CA) after correcting for control mortality with Abbott’s formula47. Lethal concentration values (LC) were compared based on their 95% confidence limits, with non-overlapping intervals used to establish significance. Relative susceptibility ratios for the two species were calculated by dividing the LC estimates of F. occidentalis by the corresponding LC estimates for T. tabaci.

Thrips response to insecticides in laboratory experiments

Maximum field rates of avermectin (1 ppm) and beta-cypermethrin (5 ppm) were used to determine the response of each species to these insecticides when both species were present on the same plant. Rates are based on the insecticide registration labels. Five hundred recently eclosed adults of each F. occidentalis and T. tabaci were added to a cage (100 × 100 × 100 cm) containing 15 purple cabbage plants (15–18 days old). After adults dispersed inside the cage, plants were sprayed until runoff with one of three insecticide treatments: avermectin (1 ppm), beta-cypermethrin (5 ppm) or a control (distilled water). Sampling for adult thrips was conducted on the F1, F2, F3, F4, F5 and F6 generations of the experiments. Generations were based on the eclosion of adult progeny, with generation times for these trials lasting approximately 15 days. Insecticide treatments were applied again after thrips samples were collected from the F1 and F2 generations. No additional insecticide applications were made after the F2 generation. To determine the relative species composition, fifty adult thrips were randomly collected from within each cage on each sampling date, and they were identified to species, under a dissecting microscope. All treatments were replicated three times.

The proportions of F. occidentalis among the mixed species in each generation were then compared using generalized linear models, incorporating a binomial distribution of the response data and a logit link. Treatment means were separated using the least squares means option48.

Thrips response to insecticides in field experiments

Field experiments were conducted in Wucheng and Xiajin Counties, located in Dezhou City, Shandong Province in 2015, where F. occidentalis and T. tabaci co-occur (Gao et al., unpublished data). Purple cabbage was planted in both counties on 1 April at sites where F. occidentalis and T. tabaci were previously observed to co-occur. A randomized complete block experimental design was utilized, with three replications of each of three treatments. The three treatments were avermectin applied at 1 ppm, beta-cypermethrin applied at 5 ppm, and distilled water. The hand-pump type sprayer used to apply treatments was calibrated to deliver 1300 L/ha at 20–30 kPa, with 90 μm openings in the nozzles. A 5 m space without any crops was set up between plots to minimize potential insecticide contamination among plots. Each plot was approximately 66.7 m2 and seeded at a rate expected to produce 200 plants per plot (30,000 per hectare), as is common in this farming system. Purple cabbage was maintained using the standard agronomic practices for each of the local areas, except no other insecticides were used throughout the season.

Sampling began on 10 May and was conducted on days 1, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 75 of the experiment. Insecticides were applied after the collection of thrips samples on days 1, 15 and 30 of the experiment; no insecticide was applied on day 45, 60 and 75. Five sites were randomly chosen for sampling within each plot on each sampling date. Ten adult thrips were collected from each of the sampling sites for a total of 50 adults collected per plot per date. Thrips were identified to species under a dissecting microscope.

For these field experiments, the proportions of F. occidentalis on each sample date were compared by utilizing generalized linear models, incorporating a binomial distribution of the response data and a logit link. Data were analyzed separately for the trials conducted at Wucheng and Xiajin. Treatment means were separated using the least squares means option45.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhao, X. et al. Pesticide-mediated interspecific competition between local and invasive thrips pests. Sci. Rep. 7, 40512; doi: 10.1038/srep40512 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Reitz, S. R. & Trumble, J. T. Competitive displacement among insects and arachnids. Annu Rev Entomol. 47, 435–465 (2002).

Porter, S. D., Van Eimeren, B. & Gilbert, L. E. Invasion of red imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): microgeography and competitive displacement. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 81, 913–918 (1988).

Elliott, N., Kieckhefer, R. & Kauffman, W. Effects of an invading coccinellid on native coccinellids in an agricultural landscape. Oecologia. 105, 537–544 (1996).

Levine, J. M., Adler, P. B. & Yelenik, S. G. A meta-analysis of biotic resistance to exotic plant invasions. Ecol Lett. 7, 975–989 (2004).

Paini, D. R. & Roberts, J. D. Commercial honey bees (Apis mellifera) reduce the fecundity of an Australian native bee (Hylaeus alcyoneus). Biol Conserv. 123, 103–112 (2005).

Kirk, W. D. J. & Terry, L. I. The spread of the western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande). Agric For Entomol. 5, 301–310 (2003).

Reitz, S. R. Biology and ecology of the western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): The making of a pest. Florida Entomol. 92, 7–13 (2009).

Morishita, M. Seasonal abundance of the western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande), and onion thrips, Thrips tabaci (Lindeman) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), on weeds in persimmon and mandarin orange orchards. Jap J Appl Entomol Z. 49, 195–203 (2005).

Lacasa, A., Esteban, J. R., Beitia, F. J. & Contreras, J. Distribution of western flower thrips in Spain. Thrips Biology and Management (eds Parker, B. L., M. Skinner, M. & Lewis, T. ), 465–468 (Plenum Press, New York 1995).

Atakan, E. & Uygur, S. Winter and spring abundance of Frankliniella spp. & Thrips tabaci Lindeman (Thysan., Thripidae) on weed host plants in Turkey. J Appl Entomol. 129, 17–26 (2005).

Borbon, C. M., Gracia, O. & Piccolo, R. Relationship between tospovirus incidence and thrips populations on tomato in Mendoza, Argentina. J Phytopathol. 154, 93–99 (2006).

Van Rijn, P. C. J., Mollema, C. & Steenhuis-Broers, G. M. Comparative life history studies of Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on cucumber. Bull Entomol Res. 85, 285–297 (1995).

Northfield, T. D., Paini, D. R., Reitz, S. R. & Funderburk, J. E. Within plant interspecific competition does not limit the highly invasive thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis in Florida. Ecol. Entomol. 36, 181–187 (2011).

Paini, D. R., Funderburk, J. E. & Reitz, S. R. Competitive exclusion of a worldwide invasive pest by a native. Quantifying competition between two phytophagous insects on two host plant species. J Anim Ecol. 77, 184–190 (2008).

Reitz, S. R., Gao, Y. L. & Lei, Z. R. Thrips: Pests of concern to China and the United States. Agr Sci China. 10, 867–892 (2011).

Wang, Z. H. et al. Field-evolved resistance to insecticides in the invasive western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis in China. Pest Manag Sci. 72, 1440–1444, doi: 10.1002/ps.4200 (2016).

Gao, Y. L., Lei, Z. R., Abe, Y. & Reitz, S. R. Species displacements are common to two invasive species of leafminer fly in China, Japan, and the United States. J Ecol Entomol. 104, 1771–1773 (2011).

Gao, Y. L. et al. Local crop planting systems enhance insecticide-mediated displacement of two invasive leafminer fly. PLoS ONE 9, e92625 (2014).

Liang, P., Tian, Y. A., Biondi, A., Desneux, N. & Gao, X. W. Short-term and transgenerational effects of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on susceptibility to insecticides in two whitefly species. Ecotoxicology 21, 1889–1898, doi: 10.1007/s10646-012-0922-3 (2012).

Li, X.-W., Fail, J., Wang, P., Feng, J.-N. & Shelton, A. Performance of arrhenotokous and thelytokous Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on onion and cabbage and its implications on evolution and pest management. J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 1526–1534 (2014).

Wang, J. L., Li, H. G., Ma, Z. G. & Zheng, C. Y. Interspecific competition between Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips tabaci on purple cabbage. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 44, 5006–5012 (2011).

Zhang, Z. J. et al. Life history of western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysan., Thripae), on five different vegetable leaves. J Appl Entomol. 131, 347–354 (2007).

Demirozer, O., Tyler-Julian, K., Funderburk, J., Leppla, N. & Reitz, S. Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) integrated pest management programs for fruiting vegetables in Florida. Pest Manag. Sci. 68, 1537–1545, doi: 10.1002/ps.3389 (2012).

Northfield, T. D., Paini, D. R., Funderburk, J. E. & Reitz, S. R. Annual cycles of Frankliniella spp. (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) thrips abundance on north Florida uncultivated reproductive hosts: Predicting possible sources of pest outbreaks. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 101, 769–778 (2008).

Paini, D. R., Funderburk, J. E., Jackson, C. T. & Reitz, S. R. Reproduction of four thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on uncultivated hosts. J Entomol Sci. 42, 610–615 (2007).

Desneux, N., Decourtye, A. & Delpuech, J. M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 52, 81–106 (2007).

Guedes, R. N., Smagghe, G., Stark, J. D. & Desneux, N. Pesticide-induced stress in arthropod pests for optimized intergrated pest management programs. Annu Rev Entomol. 61, 43–62 (2016).

He, H. G., Jiang, H. B., Zhao, Z. M. & Wang, J. J. Effects of a sublethal concentration of avermectin on the development and reproduction of citrus red mite, Panonychus citri (McGregor) (Acari: Tetranychidae). Int J Acarol. 37, 1–9, doi: 10.1080/01647954.2010.491798 (2011).

Zuo, Y. Y. et al. Sublethal effects of indoxacarb and beta-cypermethrin on Rhopalosiphum padi (Hemiptera: Aphididae) under laboratory conditions. Florida Entomol. 99, 445–450 (2016).

Xiao, D. et al. Sublethal effect of beta-cypermethrin on development and fertility of the Asian multicoloured ladybird beetle Harmonia axyridis . J Appl Entomol. 140, 598–608, doi: 10.1111/jen.12302 (2016).

Hogmire, H. W., Brown, M. W., Schmitt, J. J. & Winfield, T. M. Population development and insecticide susceptibility of apple aphid and spirea aphid (Homoptera, Aphididae) on apple. J Entomol Sci. 27, 113–119 (1992).

Lowery, D. T., Smirle, M. J., Foottit, R. G. & Beers, E. H. Susceptibilities of apple aphid and spirea aphid collected from apple in the Pacific Northwest to selected insecticides. J Econ Entomol. 99, 1369–1374 (2006).

Brown, M. W., Hogmire, H. W. & Schmitt, J. J. Competitive displacement of apple aphid by spirea aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) on apple as mediated by human activities. Environ Entomol. 24, 1581–1591 (1995).

Chu, D., Wan, F. H., Zhang, Y. J. & Brown, J. K. Change in the biotype composition of Bemisia tabaci in Shandong Province of China from 2005 to 2008. Environ Entomol. 39, 1028–1036 (2010).

Horowitz, A. R., Kontsedalov, S., Khasdan, V. & Ishaaya, I. Biotypes B and Q of Bemisia tabaci and their relevance to neonicotinoid and pyriproxyfen resistance. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 58, 216–225 (2005).

Pascual, S. & Callejas, C. Intra- and interspecific competition between biotypes B and Q of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from Spain. B Entomol Res. 94, 369–375 (2004).

Gao, Y. L., Lei, Z. R. & Reitz, S. R. Western flower thrips resistance to insecticides: detection, mechanisms and management strategies. Pest Manag Sci. 68, 1111–1121 (2012).

Gonzalez, F. et al. New opportunities for the integration of microorganisms into biological pest control systems in greenhouse crops. J Pest Sci. 89, 295–311, doi: 10.1007/s10340-016-0751-x (2016).

Diaz-Montano, J., Fuchs, M., Nault, B. A., Fail, J. & Shelton, A. M. Onion thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): A global pest of increasing concern in onion. J. Econ. Entomol. 104, 1–13 (2011).

Pizzol, J. et al. Comparison of two methods of monitoring thrips populations in a greenhouse rose crop. J Pest Sci. 83, 191–196 (2010).

Gao, Y. L., Reitz, S. R., Wang, J., Xu, X. N. & Lei, Z. R. Potential of a strain of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) as a biological control agent against the western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Biocontrol Sci Techn. 22, 491–495 (2012).

Wu, S. Y. et al. Feeding on Beauveria bassiana-treated Frankliniella occidentalis causes negative effects on the predatory mite Neoseiulus barkeri . Scientific Reports 5, srep12033 (2015).

Parolin, P. et al. Secondary plants used in biological control: A review. Int. J. Pest Manag. 58, 91–100, doi: 10.1080/09670874.2012.659229 (2012).

Chailleux, A., Mohl, E. K., Alves, M. T., Messelink, G. J. & Desneux, N. Natural enemy-mediated indirect interactions among prey species: potential for enhancing biocontrol services in agroecosystems. Pest Manag. Sci. 70, 1769–1779 (2014).

Hodges, A., Ludwig, S., Osborne, L. & Edwards, G. B. Pest Thrips of the United States: Field Identification Guide. North Central IPM Center, Champaign, IL. http://www.ncipmc.org/alerts/chili_thrips_deck.pdf (2009).

Wang, Z. H. et al. Monitoring the insecticide resistance of field populations of western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis, in the Beijing area (in Chinese). Chin Bull Entomol. 48, 542–547 (2011).

Abbott, W. S. A method for computing the effectiveness of insecticides. J Econ Entomol. 18, 265–267 (1925).

SAS. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 9.22 (Cary, NC, SAS Institute 2010).

Acknowledgements

This study is financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program Key Special Projects (2016YFC1200603), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371942).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: X.Z., S.R., Z.L., and Y.G. Performed the experiments: X.Z., H.Y., and Y.G. Analyzed the data: X.Z., H.Y., and Y.G. Wrote the paper: X.Z., S.R., D.P., and Y.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Reitz, S., Yuan, H. et al. Pesticide-mediated interspecific competition between local and invasive thrips pests. Sci Rep 7, 40512 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40512

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40512

This article is cited by

-

Effects of elevated CO2 and spinetoram on the population fitness and detoxification enzymes activities in Frankliniella occidentalis and F. intonsa

Journal of Pest Science (2024)

-

Elevated CO2 affects interspecific competition between the invasive thrips Frankliniella occidentalis and native thrips species

Journal of Pest Science (2024)

-

Mechanism underlying avermectin-mediated acceleration of interspecific competition between Frankliniella occidentalis and Megalurothrips usitatus

International Journal of Tropical Insect Science (2024)

-

Population Performance of Thrips hawaiiensis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on Different Vegetable Host Plants

Neotropical Entomology (2021)

-

Effect of elevated CO2 on the population development of the invasive species Frankliniella occidentalis and native species Thrips hawaiiensis and activities of their detoxifying enzymes

Journal of Pest Science (2021)