Abstract

Background/Objectives:

There has been an increasing global recognition of the need for effective strategies to prevent and control childhood obesity. In this study, we aimed to identify the effectiveness of an obesity prevention program focused on motivating environments in school.

Subjects/Methods:

In this school-based, prospective, quasi-experimental study, we enrolled three elementary (fourth graders) and two middle (seventh graders) schools located in Chungju, Korea. We assigned three of the schools to the intervention group and two schools to the control group. The intervention group received 1 year of environmental intervention. Diet- and exercise-related educational video content was provided by internet protocol television services during rest time, and various design materials were painted along the school staircase and hallway to encourage physical activities. Overweight and obese students were recommended to join the summer vacation obesity care program.

Results:

The final number of total participants was 768 (control 350 and intervention 418). After 1 year of follow-up, there was no significant difference in the overweight/obesity incidence rates and remission rates between the two groups. However, the intervention group showed a greater decrease in the body mass index (BMI) z-score (−0.11 (95% confidence interval (CI) −0.16 to −0.06), P<0.001), increase in height (1.1 cm (95% CI 0.8 to 1.4), P<0.001), reduction of body fat, and increase in muscle mass compared with the control group. In addition, blood pressure (BP) was significantly reduced, and significant improvement in physical fitness followed. In subgroup analysis, students of normal weight, boys and younger participants showed the most beneficial results in weight-related outcomes. In addition, the BP reduction was more pronounced in the higher BMI group, boys and older children.

Conclusions:

A simple environmental intervention could effectively influence children. By adding to previously studied strategies, we can develop a more effective obesity prevention program for children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious global health burdens of the 21st century. Globally, combined prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity had increased by 47.1% from 1980 to 2013.1 The problem affects many upper-/middle-income countries, and the prevalence is rapidly increasing in Asia and Africa.2 Obesity causes adverse health consequences, and is a major risk factor for diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, certain cancers and osteoarthritis.3, 4 Prior studies have provided good evidence that childhood obesity persists into adulthood and is associated with increased mortality.5, 6

Based on such a background, there has been an increasing global recognition of the need for effective intervention to prevent childhood obesity.2 Hence, schools, as a place of learning and real life for students, are recognized as an ideal setting for effective intervention.7, 8 Many attempts have been made to identify more effective and reliable programs in school-based settings.9, 10, 11 Despite methodological differences depending on their focus, the core features of earlier studies usually included didactic and intensive methods. Most prior interventions were provided by teachers or other staff who implemented health-promotion strategies using a curriculum of educational programs or physical classes, or by providing healthful foods.12, 13, 14 These types of interventions can be effective, but require large amounts of labor, funding and time. Furthermore, there is limited ability to generalize the results to other socially deprived regions. To date, only a few studies have evaluated the effects of school-based environmental interventions that encourage healthy behavior in students, and their effectiveness has not yet been validated.4, 15

In this study, we aimed to identify the effects of an obesity prevention program that focused on motivating environments in a school-based setting. After 1 year of intervention, we compared improvements in the body mass index (BMI) z-score and other weight-related outcomes in the intervention and control groups.

Subjects and methods

Study design and participants

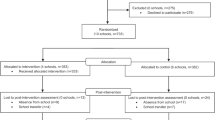

This was a school-based, prospective, quasi-experimental study. The participants were recruited by choosing the applicants after holding a briefing on the study objectives for students in elementary and middle schools in Chungju, Korea. Three elementary schools and two middle schools were selected, and the eligible participants were fourth graders in the elementary schools (aged 9–10 years) and seventh graders in the middle schools (aged 12–13 years) with the baseline results of anthropometry.

Schools were the unit for intervention. To avoid differences in baseline age, we used stratified method to allocate the schools into intervention and control groups. We matched the schools according to the same grades of participants at baseline; the elementary schools and middle schools constituted the respective pairs. Thus, two of the three elementary schools and one of the two middle schools were assigned to the intervention group.

A research briefing was held for the parents of participating students, at which prior consent was requested. If the parents were unable to attend, a letter was sent to obtain the consent of the student and parents. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul St Mary’s Hospital (KIRB-00465-005), Seoul, Korea.

Measures

Anthropometry

Each student was assessed before and after intervention. The height was measured without shoes using a scale-mounted stadiometer (BIKI-200; Jawon Medical, Seoul, Korea). The weight and body fat were measured in light clothing without shoes with an ioi 353 analyzer (Jawon Medical) using bioelectrical impedance analysis. The BMI was calculated using the participant’s height and weight data (kg m–2), and the BMI z-score and percentile were determined based on the 2007 Korean standard growth table.16 The waist size and blood pressure (BP) were measured by an experienced nurse. The waist circumference (WC) measurement was performed with the participant standing erect with his/her arms at the side and feet together. The measurement was performed mid-way between the bottom of the rib cage and the iliac crest. The BP was measured with a mercury sphygmomanometer (Model CL4114, Youngpoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) using an appropriate cuff. The BP was measured twice, and the average was calculated.

Physical fitness

The student physical activity promotion system (PAPS) was performed in each school’s gymnasium before and after intervention to evaluate student health and fitness status. The PAPS is a registered name referring to a Korean system for evaluating students. This study used the standard methods of PAPS to evaluate cardiovascular endurance, flexibility, muscular/endurance strength and agility. All of the evaluation processes were performed by a specialized organization (Welltizen, Seoul, Korea).

Round-trip, long-distance running (15 and 20 m for elementary and middle school students, respectively) was performed to evaluate cardiovascular endurance. Upper-body bending, grasping and a standing long jump were performed twice to evaluate flexibility, muscular/endurance strength and agility, respectively. Each measured value was scored based on the standards suggested by the Korean Ministry of Education in 2009.17 The range of possible total scores is 0–100 (each event score is 0–20). Higher scores indicate a better fitness level.

Survey

A survey was performed in the school classrooms before and after the intervention to assess student health behaviors. For the elementary school students, two survey guides visited each classroom and instructed the students to complete the questionnaire in groups. For the middle school students, a nurse–teacher visited each classroom to collect responses from the students after handing out and explaining the questionnaire.

The questionnaire collected information on physical activity, sleeping, dietary habit, nutritional knowledge, physical self-image, self-respect, life quality and depression. The physical activity questions concerned the type and duration of exercise performed outside of the physical education class, the time spent at the television or computer and the methods of commuting to school. The dietary habit questions mainly concerned the frequency of eating specific foods (12 questions, possible score range of 0–60) and eating behaviors, such as regular meal, unbalanced diet, eating-out, habitual eating, eating when full, eating under stress, impulsive eating and others (16 questions, possible score range of 0–48). Higher scores indicate the presence of more desirable habits. These life habit questions were constructed by modifying and supplementing the questionnaire suggested by the Youth Health Behavior Survey of the Korean Ministry of Education and the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity.18

A parental questionnaire was conducted before the intervention in the form of a home correspondence. It consisted of nine questions about the child, such as birth weight, delivery method, breastfeeding status and past history. It also contained 11 questions about the child’s family, such as parental height and weight, family morbidity, diet, physical activity level and socioeconomic status. These questions were constructed by modifying the questionnaire suggested by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity.18

Intervention

The participants in the intervention group received environmental intervention in addition to the usual school curriculum. The detailed contents of the intervention are shown in Table 1. Based on the pre-intervention results, personalized suggestions for improving physical strength and dietary habits and information on the daily caloric requirement were provided to individuals in the form of a handout. In each classroom, educational dietary and exercise videos and the daily lunch menu were presented 5–10 min a day by internet protocol television service for 1 academic year. Various design materials were also painted along the school staircase and hallway to encourage physical activities by the students.

During the vacation period, student daily life transitions from the school to the family and regional community. Therefore, an intervention centered on the school but continued in the community must be maintained. In particular, obese students require ongoing management during vacations. For students who are already overweight or obese (BMI⩾85th percentile), a once-weekly obesity care program was held during the 12-week summer vacation. Intensive exercise was not mandatory, but the program was instead intended to provide an extension of the school environment to continue learning and provide a place to exercise during vacation.

Different intervention levels were performed according to age group. The intervention lasted 1 school year from May 2014 until follow-up measurements in April 2015.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the mean difference between two groups in the change in BMI z-score from baseline to 1 year later. Secondary outcomes were other weight-related outcomes (for example, weight, WC, percent body fat, and prevalence, incidence, and remission rates of overweight or obesity), BP and physical fitness. Finally, the changes in physical activity and dietary habits were analyzed.

The body weight categories according to BMI percentiles used in this study were as follows: underweight (<5th percentile), normal (⩾5th to <85th percentile), overweight (⩾85th to <95th percentile) and obese (⩾95th percentile, or BMI ⩾25). The incidence rate of overweight (obesity) during the intervention was defined as the number of newly diagnosed, overweight (obese) students during follow-up relative to the number of students underweight and normal (overweight) at baseline. The remission rate of overweight (obesity) was defined as the number of students that were no longer overweight (obese) at follow-up divided by the number of all overweight (obese) students at baseline.

Sample size and power

A sample size of two clusters per group with 200 individuals per cluster achieved 83% power to detect a difference of 0.25 in BMI z-score between the control and intervention groups when the s.d. was 0.5 and the intracluster correlation was 0.002 with a significance level of 0.05.19 In this study, owing to the lack of the individuals per cluster in the one intervention school, we recruited one more cluster in the intervention group. Finally, the five schools (two schools in the control group and three schools in intervention group) were included.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means±s.d., or mean (95% confidence interval (CI)). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (%). Baseline differences between two groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test or a chi-square test. In the same group, differences between pre- and post-intervention were examined using a paired t-test. Changes in outcomes of continuous variables were compared between two groups using a linear mixed model analysis. A generalized estimating equation was used to compare the results of categorical variables. Adjustments were made for age and sex. Subgroup analysis was performed after categorizing the subjects according to body weight categories, sex and age. All data were analyzed using PASW Statistics version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistically significant differences were considered at a P-value<0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The initial total number of eligible participants was 884: 404 elementary (fourth grade) and 480 middle (seventh grade) school students. Eleven students could not participate in the student PAPS because of absence or injury, and 53 could not complete the survey. Thus, 820 students (397 elementary and 423 middle school students) participated at baseline. Of these, 52 students (3 transferred and 49 absent or injured) were missing after 1 year of intervention. Therefore, a final number of 768 students were analyzed in this study: 365 elementary (fifth grade) and 403 middle (eighth grade) school (Figure 1).

The baseline characteristics of the students in both groups are shown in Table 2. At baseline, 18.8% of the controls and 14.8% of the intervention group exhibited obesity; this percentage was higher than that reported in student health inspection statistics in Korea in 2014; the obesity prevalence in fourth and seventh graders was 9.3% and 11.0%, respectively. There was no significant difference in age, sex, BMI, degree of obesity and body composition between the two groups. However, the WC and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) were significantly greater in the control group, and BP was higher in the intervention group. At baseline, the intervention group showed a lower score in most types of physical fitness, except for cardiopulmonary endurance, and a lower score in eating behavior than the control group.

Vacation obesity care program

Among the 113 overweight and obese students in the intervention group, only 30 (26.5%) participated in this program at least once. Among these, only 12 students (10.6%) completed the vacation program according to the completion criterion of over 70% attendance.

Change in degree of obesity after intervention

After 1 year of intervention, 3.5% of obese students in the intervention group improved their BMI classification, resulting in an increased proportion of overweight subjects. However, we did not observe a significant difference in the change of BMI classification between the intervention and the control groups. In addition, the overweight/obesity incidence rates and remission rates did not statistically differ between the two groups (Table 3).

Change in weight-related outcomes and height

Table 4 shows the change from baseline in both groups and the mean difference between groups (treatment effect) after intervention. After 1 year, the intervention group showed a significant reduction in BMI z-score compared with the control group (−0.11, (95% CI −0.16 to −0.06); P<0.001). Although the change in mean body weight increased similarly in both groups, the difference in height increase in both groups affected the BMI. Notably, the intervention group showed a significantly greater height increase, with an average change of 1.1 cm per year, compared with the control group (P<0.001). In addition, a significant improvement in body composition with increased muscle mass and decreased fat mass was observed. However, WC and WHtR were significantly increased in the intervention group.

In the subgroup analysis (Table 5), students with normal weight, boys and younger participants showed the most statistically significant improvement in BMI z-score and body composition. The obese group showed the greatest reduction in BMI z-score (P=0.05) and body fat mass (P=0.004).

Change in BP and physical fitness

The BP also showed significant improvement. In the subgroup analysis, this finding was more beneficial in the higher BMI classification group, boys and older students (Table 5). In addition, there was a notable improvement in physical fitness. At baseline, the intervention group exhibited lower values in all categories of PAPS than the control group. However, after intervention, score ranking results in most categories were reversed between the two groups (Supplementary Table S1). All of the subgroup analyses showed significant improvement, with a similar average change compared with the control group (Table 5).

Change in physical activity and dietary habits

To identify behavioral changes, main physical activities and dietary habits before and after the intervention were analyzed based on the survey (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). After 1 year of follow-up, more students in the control group showed an increase in BMI z-score compared with baseline than the intervention group (Δ BMI z-score>0): 192 (55.2%) students in the control group and 172 (41.2%) in the intervention group.

The students who showed an increase in the BMI z-score after 1 year had a tendency to have a higher frequency of bad eating behaviors at baseline such as night or frequent snacking, and eating when full. Moreover, these students showed a significant increase in the proportion of those having less vigorous physical activity time after 1 year, compared with students who did not show an increase in the BMI z-score (Supplementary Table S2).

When the intervention group and the control group were analyzed separately (Supplementary Table S3), this difference in change of vigorous physical activity was only significant in the control group students (P=0.045). Exercise outside of gym class showed reverse results between the control and intervention groups. The intervention group showed a decrease in the proportion of those engaging in less exercise time after 1 year of follow-up, regardless of the change in BMI z-score. In contrast, the control group showed an increase in proportion, regardless of the change in BMI z-score. This showed statistical significance when only the students with an increase in the BMI z-score was compared between the control and intervention group (P<0.001). Finally, the control group showed an increase in students who ate impulsively after 1 year, compared with the intervention group in which a similar proportion was maintained. This also showed statistical significance when only the students with an increase in the BMI z-score was compared between the two group (P=0.037).

However, we did not observe significant changes in the physical activities of television viewing and computer play, and dietary habits (except for impulsive eating).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that a simple environmental intervention could effectively motivate and influence children. Although we did not observe the significant difference in the overweight/obesity incidence and remission rates between the two groups, the intervention group showed significantly greater reductions in BMI z-score, increase in height, decline in body fat and increase in muscle mass compared with the control group. These physical improvements led to improvement in physical fitness and a reduction of BP. We also observed some favorable behavioral changes through an increase in physical activity and correction of bad dietary habits.

In the subgroup analysis (Table 5), students of normal weight, boys and younger participants showed the most beneficial results in weight-related outcomes. As this was a prevention program, improvement in the normal group and younger participants would exhibit a greater preventive effect after a longer follow-up. Compared with this result, BP reduction was more beneficial in the higher BMI classification group, boys and older participants. This could be a feature of the treatment part of this program.

In our study, WC and WHtR showed different results compared with other weight-related outcomes. The increase in WC could be considered as a result of the larger growth in the intervention group, but the WHtR, which is relatively non-age-dependent index, was decreased in the control group and increased in the intervention group.20 It could be a result from the baseline difference. At baseline, the WHtR value was significantly higher in the control group. However, after 1 year of follow-up, there was little difference in the WHtR between the two groups; 0.462±0.077 in control group vs 0.456±0.068 in intervention group (P=0.281).

Our study possesses strength in that it demonstrates not only the effectiveness of environmental intervention through various weight-related outcomes but also through improvements in rate of height increase, physical fitness and BP. Prior studies mainly compared the effects of intervention by using weight-related outcomes (for example, BMI, WC, percent body fat, skinfold thickness, and prevalence of overweight or obesity).10, 21, 22 However, we evaluated the effects by considering anthropometry as well as physical function. Moreover, we analyzed behavioral changes associated with the intervention.

The effect of childhood obesity programs on height increase is an outcome that is usually ignored or has shown no benefit. In this study, we observed significantly greater height increases in all intervention subgroups compared with the control group. Height increase was the main contributor to BMI improvement in this study. A negative relationship between growth hormone (GH) secretion and adiposity has long been recognized. Obese children have decreased spontaneous GH secretion as well as a blunted response of GH to stimulation tests.23, 24, 25 The defect in GH secretion is partially reversed after improvements in metabolism through weight reduction or a short-term reduced calorie diet.24, 26 We did not measure the GH. However, improvement in body composition, reduction in body fat and increase in muscle mass were shown in our results. Although little is known about the relationship between physical activity and growth, the increased activity may contribute to the positive results.27, 28 Other factors that could affect a child’s height such as parental height (father’s height: 172.9±5.0 cm in control group vs 173.0±5.3 cm in intervention group, P=0.827 and mother’s height: 160.0±5.3 cm in control group vs 160.2±5.3 cm in intervention group P=0.619) and socioeconomic status (data not shown, P=0.154) showed no difference between the two groups with the analysis from the parental questionnaire.

BP is also a commonly omitted outcome in obesity prevention studies. A pooled analysis of 23 obesity prevention studies showed that those targeting both diet and physical activity led to a significantly greater reduction in both systolic BP and diastolic BP than interventions focused on diet or physical activity alone; the pooled intervention effect was −1.64 mm Hg for systolic BP and −1.44 mm Hg for diastolic BP.29 We targeted both strategies and demonstrated a much greater reduction of BP than other studies. As Chungju is a rural city of an inland province in Korea with a high incidence of hypertension in adults, the effect may be maximized.30 Obesity is related to many cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension, dyslipidemia, abnormalities in left ventricular function, endothelial dysfunction and hyperinsulinemia/insulin resistance.3 With the prominent improvement in BP in our study, a synergistic effect with other beneficial factors that were not evaluated would amplify the results of risk reduction.31, 32

Behavioral changes in this intervention showed more prominent improvement in physical activity than the dietary habit. But television viewing and computer play, which are physical activities that have addictive traits showed limited results. In addition, low attendance and completion rate of the vacation obesity program was a problem. More multidirectional and in-depth assessment of psychiatric aspects as well as inducements for obese students should be reinforced.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the participants were limited to one region and a limited number of schools. Second, this was a quasi-experimental study. This study focused on changing the environment; as the characteristics of schools closely influence each other, it is difficult to conduct a randomized controlled study. Further studies targeting a larger number of schools are needed for group randomization. Finally, we did not perform blood tests for metabolic and hormonal changes or assess the pubertal status of participants, all of which could affect weight and growth.

However, our findings have the strength of a prospective study, and show that environmental interventions affect schools through various outcomes. Furthermore, we included participants from all BMI categories and demonstrated the effectiveness using subgroup analyses. Finally, our study was performed in a rural city with a high prevalence of obesity and hypertension in Korea. The majority of evidence regarding school-based obesity prevention was derived from studies in high-income countries and large cities.10, 21 For adoption by lower-/middle-income countries and rural areas, we need an intervention modality that is easy to apply, efficient and proven in that region.

In conclusion, a motivating environment in schools can effectively influence children. Our study focused on a simple change of environments in schools, but we included strategies regarding diet, physical activities, parental involvement, and more intense and ongoing approaches for students who were already obese. In addition to the schools, the regional health center and local government cooperated in creating a desirable environment for children. These enabled notable results. Our intervention could be introduced into lower-/middle-income countries as well as rural areas. Moreover, by adding to previously studied strategies, we can develop more effective obesity prevention programs for children.

References

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 766–781.

Chestnov O . Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2014.

Reilly JJ . Descriptive epidemiology and health consequences of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 327–341.

Han JC, Lawlor DA, Kimm SY . Childhood obesity. Lancet 2010; 375: 1737–1748.

Maffeis C, Tato L . Long-term effects of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality. Horm Res 2001; 55 (Suppl 1): 42–45.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ . Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 474–488.

Story M, Kaphingst KM, French S . The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child 2006; 16: 109–142.

Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J . School-based obesity prevention: a blueprint for taming the epidemic. Am J Health Behav 2002; 26: 486–493.

Lavelle HV, Mackay DF, Pell JP . Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to reduce body mass index. J Public Health (Oxf) 2012; 34: 360–369.

Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2015; 16: 547–565.

Group HS, Foster GD, Linder B, Baranowski T, Cooper DM, Goldberg L et al. A school-based intervention for diabetes risk reduction. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 443–453.

Kriemler S, Zahner L, Schindler C, Meyer U, Hartmann T, Hebestreit H et al. Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c785.

de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB . A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1397–1406.

Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby K, LaRocca RL . School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 28: CD007651.

Williamson DA, Copeland AL, Anton SD, Champagne C, Han H, Lewis L et al. Wise mind project: a school-based environmental approach for preventing weight gain in children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15: 906–917.

JS M SY L CM N Choe JM C, BK JW S . 2007 Korean National Growth Charts: reveiw of developmental process and an outlook. Korean J Pediatr 2008; 51: 1–25.

Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. The pilot school management report of physical activity promotion system, 2009.

Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. Childhood and adolescents obesity. 2012.

Ford AL, Hunt LP, Cooper A, Shield JP . What reduction in BMI SDS is required in obese adolescents to improve body composition and cardiometabolic health? Arch Dis Child 2010; 95: 256–261.

Weili Y, He B, Yao H, Dai J, Cui J, Ge D et al. Waist-to-height ratio is an accurate and easier index for evaluating obesity in children and adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15: 748–752.

Wang Y, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Bleich S, Cheskin L, Weston C et al. Childhood Obesity Prevention Programs: Comparative Effectiveness Review and Meta-Analysis. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2013.

Sobol-Goldberg S, Rabinowitz J, Gross R . School-based obesity prevention programs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21: 2422–2428.

Loche S, Cappa M, Borrelli P, Faedda A, Crino A, Cella SG et al. Reduced growth hormone response to growth hormone-releasing hormone in children with simple obesity: evidence for somatomedin-C mediated inhibition. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1987; 27: 145–153.

Williams T, Berelowitz M, Joffe SN, Thorner MO, Rivier J, Vale W et al. Impaired growth hormone responses to growth hormone-releasing factor in obesity. A pituitary defect reversed with weight reduction. N Engl J Med 1984; 311: 1403–1407.

Coutant R, Lahlou N, Bouvattier C, Bougneres P . Circulating leptin level and growth hormone response to stimulation tests in obese and normal children. Eur J Endocrinol 1998; 139: 591–597.

Kelijman M, Frohman LA . Enhanced growth hormone (GH) responsiveness to GH-releasing hormone after dietary manipulation in obese and nonobese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988; 66: 489–494.

Rogol AD, Clark PA, Roemmich JN . Growth and pubertal development in children and adolescents: effects of diet and physical activity. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 72: 521S–528S.

Malina RM . Physical activity and training: effects on stature and the adolescent growth spurt. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994; 26: 759–766.

Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Segal JB, Kim MT, Wang Y . Effect of childhood obesity prevention programs on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2014; 129: 1832–1839.

Lee HS, Park YM, Kwon HS, Lee JH, Park YJ, Lim SY et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among people over 40 years old in a rural area of South Korea: the Chungju Metabolic Disease Cohort (CMC) Study. Clin Exp Hypertens 2010; 32: 166–178.

Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur LA, Burrows T, Stewart L, Neve M et al. Impact of dietary and exercise interventions on weight change and metabolic outcomes in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167: 759–768.

Reinehr T, Andler W . Changes in the atherogenic risk factor profile according to degree of weight loss. Arch Dis Child 2004; 89: 419–422.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the R&D Program of the Society of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2013M3C8A2A02078508).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Kang, B., Lee, E. et al. Effect of an obesity prevention program focused on motivating environments in childhood: a school-based prospective study. Int J Obes 41, 1027–1034 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.47

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.47

This article is cited by

-

Effectiveness of Intervention Strategies to Increase Adolescents’ Physical Activity and Reduce Sedentary Time in Secondary School Settings, Including Factors Related to Implementation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Sports Medicine - Open (2024)

-

Waist circumference as a parameter in school-based interventions to prevent overweight and obesity - a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Long-term effects of adolescent obesity: time to act

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2018)

-

Epidemic obesity in children and adolescents: risk factors and prevention

Frontiers of Medicine (2018)