Abstract

Objective

Determine if decreased rates of severe IVH in VLBW infants in California translated to decreased rates of infant death or PHH treatment among those with severe IVH, and to evaluate variations in neurosurgical treatment of neonatal PHH.

Study design

Retrospective observational cohort study of infants with severe IVH (grade III or IV) born at 220/7–316/7 weeks gestation with cranial imaging obtained within 28 days of birth and no congenital malformations. The primary outcome was a composite of PHH treatment or infant death.

Result

Severe IVH rates declined in California with a concurrent decline in PHH treatment or infant death. Regional variability was observed in PHH treatment or infant death (range 38.0–55.9%, p < 0.0001) and the rates of utilizing a “shunt-first” PHH-treatment approach (range 25.5–81.5%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

There is striking regional variation in the neurosurgical management of neonatal PHH and thus an urgent need to adopt standardized practices in IVH management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in very low birth weight (VLBW; <1500 g) infants [1, 2]. Preterm infants with severe IVH are at risk for developing hydrocephalus in the days to weeks following the hemorrhage. Infants with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH) requiring treatment with a shunt have the worst neurodevelopmental outcomes among those born preterm [1, 2]. Neurosurgical treatment of hydrocephalus requires invasive surgery for placement of a shunt and is associated with lifelong risk of treatment failure [3, 4]. Although optimization of perinatal care, including standardization of maternal antenatal steroid administration and decreased delivery room intubations, has lowered rates of severe IVH in VLBW infants in California, there are currently no interventions directed at treating severe IVH or preventing development of hydrocephalus once severe IVH has occurred [1, 5, 6]. Interventions instead are directed at treating hydrocephalus once it has developed in the days to weeks following severe IVH.

Management of PHH in preterm neonates often requires a temporizing treatment before a shunt can be placed due to the fragile condition of the preterm neonate. This is often achieved initially with bedside lumbar puncture or transfontanelle tap, and when progressive, with placement of a ventriculo-subgaleal shunt or ventricular access device for serial ventricular taps. Temporizing treatments are often utilized because PHH can manifest at an early post-natal age when infants are too fragile for permanent CSF diversion via shunt implantation, and the extent of blood products within the ventricles following IVH precludes placement of a shunt. Further, placing a shunt too early (prior to term equivalent age) is associated with a high risk of skin erosion and subsequent infection requiring shunt explantation [7,8,9]. Temporizing treatments allow a means to treat progressive ventriculomegaly, expedite clearance of blood products from the ventricles, and alleviate symptoms of intracranial hypertension in the weeks prior to permanent shunt placement [10]. Although there is no consensus on the threshold or timing for initiating temporizing treatment for developing PHH, emerging evidence supports earlier intervention with temporizing treatment in favor of improved neurodevelopmental outcomes [1, 2].

In this study, we sought (1) to determine if decreased rates of severe IVH in VLBW infants in California translated to decreased rates of infant death or PHH treatment among those with severe preterm IVH, reflecting better outcomes with earlier intervention, and (2) to evaluate regional variations in neurosurgical treatment of neonatal PHH in California. A population-level assessment of current care is needed as a starting point to inform evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice and actionable treatment recommendations.

Materials/subjects and methods

This is an observational cohort study utilizing clinical admissions and discharge data collected prospectively in the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative (CPQCC). The CPQCC collects prospective data from >90% of neonatal intensive care units in California, with 135 member hospitals, accounting for >95% of VLBW births in California. Data collected by CPQCC conforms to variable definitions developed by the Vermont Oxford Network (VON) with national and international reach. Data quality is high, due to standardized extraction, extensive training, audit, automated error detection, reconciliation, and low missingness (<2%).

Study population

This study included infants born between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2023, and cared for at a CPQCC-associated neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Infants born at 220/7–316/7 weeks gestation who had cranial imaging within 28 days of birth were included in the analysis. Gestational age in the dataset was determined by best available estimate in weeks and days. Infants with major congenital anomalies, those who died in the delivery room, and those without cranial imaging/IVH imaging data were excluded.

Outcome variables

Our primary outcome measure was a composite of PHH treatment or infant death. We selected this composite measure to mitigate survival bias in assessing PHH treatment, considering the competing risk of death in neonates with severe IVH, many of whom have an underlying diagnosis of PHH but do not survive to receive PHH treatment. Given that the majority of preterm neonates in our NICU who died during the birth hospitalization following severe IVH also had developing post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilation or hydrocephalus, we considered that the exclusion of neonatal deaths from the primary endpoint measure likely would exclude a large proportion of hydrocephalus cases, as hydrocephalus diagnosis in this cohort was identified by hydrocephalus treatment codes, in the absence of a discrete diagnostic code to identify hydrocephalus.

IVH grades were assigned I–IV according to the Papile classification system [11]. We defined permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion for hydrocephalus treatment by the Vermont Oxford Network (VON) surgical code for placement of ventriculoperitoneal or other CSF shunt (S901) or by the separately defined CPQCC variable “shunt placed for bleed”. We defined temporizing neurosurgical treatment for PHH by VON surgical codes for placement of a ventricular access device (S903), ventriculo-subgaleal shunt (S903), or external ventricular drain (S902).

Maternal and infant covariates

We considered the following maternal and infant factors in our analyses to control for all sources of confounding: maternal race/ethnicity, multiple births or gestation, cesarean delivery, lower gestation age at birth, small for gestational age status, outborn status, delivery room cardiac compressions or epinephrine administration, delivery room hypothermia, early bacterial sepsis, maternal antenatal magnesium sulfate, infant PDA, and infant NSAID exposure.

Statistical analysis

We computed the rates of PHH treatment or infant death, as well as rates of temporizing and permanent PHH treatment (CSF shunt) among neonates with severe IVH. We utilized the Cochrane-Armitage test to test for trends in the rates of severe IVH diagnosis, the composite outcome of PHH treatment or infant death, temporizing neurosurgical treatment for PHH, and permanent neurosurgical treatment for PHH over the years 2008–2023. We completed survival analysis with Kaplan-Meier curves to assess the timing of infant mortality stratified by PHH treatment status (Log-Rank test).

We evaluated the conversion from temporizing to permanent neurosurgical treatment for PHH (i.e., patients who were initially treated with a temporizing treatment that went on to receive a shunt). In addition, we assessed rates of “shunt-first” treatment (no temporizing treatment prior to placement of shunt).

We carried out univariate analysis of infant and maternal variables associated with the composite outcome of PHH treatment or infant death. We then modeled individual risk factors for PHH treatment or infant death with multivariable logistic regression. We evaluated the association of hospital-level variables with PHH treatment or infant death for hospital of birth as well as CPQCC treating hospital (which differed for outborn infants). Hospital-level variables included American Academy of Pediatrics level of care (utilizing 2012 AAP NICU level of care classifications) and CPQCC region. We completed analyses with SASv9.4 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina) and R 2023.12.1.

Results

During the years 2008–2023, 74,195 neonates in the CPQCC prospective dataset met our study criteria. Of these, 17,146 neonates (23.1%) were identified to have any grade IVH on cranial imaging obtained within 28 days of life, 5431 (31.6% of 17,146) with severe (grade III or IV) IVH. 2506 infants (46.1% of neonates with severe IVH) met the composite outcome measure of PHH treatment or infant death—587 (23.4%) of these underwent neurosurgical treatment of PHH (Fig. 1).

Neonates aged less than 32 weeks gestation, without congenital malformation, and who had cranial imaging obtained within 28 days of birth were included in the analysis. The analysis was further restricted to neonates with IVH detected on cranial imaging, severe IVH on cranial imaging, and those with treatment (temporary, permanent, or both) for PHH.

The neonatal and maternal characteristics of our study cohort are presented in Table 1. Approximately half of the cohort was of Hispanic ethnicity, and 40% of the cohort was female. Mean maternal age at infant birth was 29 years. Seventy-five percent of infants were exposed to antenatal steroids prior to delivery. There was a 64% rate of Cesarean delivery, and the chorioamnionitis rate in the cohort was 13%. Seventeen percent received CPR or epinephrine in the delivery room, and 15% were hypothermic on arrival to the NICU. 66% were noted to have a PDA, and 33% of the cohort were treated with ibuprofen or indomethacin.

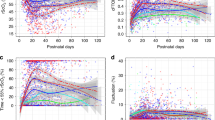

With rates of severe intraventricular hemorrhage among preterm neonates decreasing during the study period (from 9.63% in 2008 to 6.22% in 2023, p = 0.0014; Fig. 2A), we also observed decreased rates of the composite poor outcome of PHH treatment or infant death among neonates with severe IVH (from 48% in 2008 to 45% in 2023 (p = 0.0079) (Fig. 2B). Rates of temporizing and rates of “shunt-first” treatment for post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus among neonates with severe IVH did not decrease during the study period (Fig. 2B). However, there was a trend of decrease over time in the overall rates of shunts placed for post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus (from 10.5 in 2008 to 6.9 in 2023, p = 0.0137) (Fig. 2B). 357 infants with post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation following severe IVH (6.6% of severe IVH) received temporizing PHH treatment with ventricular reservoir, ventriculo-subgaleal shunt, or external ventricular drain placement, and 268 (75%) of these infants went on to subsequent permanent CSF diversion with a shunt. More than half of the infants who underwent permanent CSF diversion with a shunt (319/587, 54%) were treated with a “shunt-first” approach—without any prior temporizing CSF diversion (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A The rates of severe IVH among preterm neonates in CPQCC-associated NICUs decreased significantly during the study period (9.63% in 2008–6.22% in 2023), (p = 0.0014); B Rates of the composite outcome decreased significantly during the study period. In addition, there was a trend of decrease over time in the overall rates of shunts placed for post-hemorrhagic (Permanent PHH Treatment). Rates of temporizing and rates of “shunt-first” treatment for post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus among neonates with severe IVH did not decrease during the study period. p values: PHH or infant death (p = 0.0006; Permanent PHH Tx (p = 0.0137); Temporizing PHH Tx (p = 0.1712); Shunt 1st Tx: (p = 0.0719).

The composite outcome of PHH treatment or infant death was associated with younger gestational age at birth and lower birth weight (BW). The rates of PHH treatment or infant death were 74% for BW less than 500 g, 58% for BW between 500 and 749 g, 40%for BW between 750 and 999 g, and 33% for BW 1000 g and above. Among the significant maternal characteristics, higher rates of PHH treatment or infant death were associated with multiple births or gestations, cesarean delivery, and fetal malpresentation/breech. Administration of antenatal steroids and magnesium sulfate was associated with lower rates of PHH treatment or infant death. In addition, maternal race/ethnicity was associated with risk of PHH treatment or infant death.

Maternal and infant characteristics that remained associated with risk of PHH treatment or infant death in multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 2. Maternal race/ethnicity was associated with risk of PHH treatment or infant death, with maternal non-Hispanic white race at highest risk for the composite poor outcome and Hispanic race as the lowest. In our final multivariate model, multiple births or gestation, cesarean delivery, lower gestation age at birth, outborn status, delivery room cardiac compressions or epinephrine administration, and delivery room hypothermia were associated with higher risk of PHH treatment or infant death. Maternal antenatal magnesium sulfate, infant PDA, and infant NSAID exposure were associated with lower risk of PHH treatment or infant death.

Birth hospital characteristics associated with risk of PHH treatment or infant death in our multivariable logistic regression model are as shown in Table 2. The CPQCC region in which the infant’s birth hospital was located was associated with risk of PHH treatment or infant death. Region 11 had the lowest rates of the composite poor outcome of infant death or PHH treatment and thus was set as the reference region. When compared to the reference region (region 11), birth hospital regions 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 10 were shown to have significantly higher odds of the composite outcome of infant death or PHH treatment. In addition, AAP NICU Level was a significant predictor of the composite outcome of infant death or PHH treatment (Table 2, p = 0.001). Infants born in level IV NICUs had highest risk of the composite poor outcome of infant death or PHH treatment (Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrates that the mortality in severe IVH occurred predominantly within the first 28 days of life. Infants who survived the initial weeks following hemorrhage and were subsequently treated with temporizing treatment in the following days and weeks had lower mortality than untreated infants. Similarly, those who survived to permanent PHH treatment had the lowest mortality rates. (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Among neonates treated for PHH in the CPQCC geographic regions, the mode of PHH treatment administered across perinatal regions in California varies significantly. We observed regional variation in the treatment of PHH with a “shunt-first” approach, ranging from as low as 25.5% to as high as 81.5% (Fig. 3A). We also observed variable rates of the composite outcome (PHH treatment or infant death) from 38.0% to 55.9% across perinatal regions (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 3). The CPQCC region reported is the region in which the infant’s birth hospital was located, thus reflecting perinatal care received at the birth hospital and not related to transfers to a different hospital if transfers occurred.

A Regional variation in percentage of neonates treated for PHH with no prior temporizing treatment (shunt-first) in the 11 CPQCC regions. p < 0.0001 B The rates of PHH or infant death differed significantly between the CPQCC regions in which the neonates were born. P < 0.0001. †Region 10 (Kaiser North) and 11 (Kaiser South) are not shown in the representation above as they span a wide range of California counties. Region 10 shunt-first rate = 48.28%, Region 11 shunt-first rate = 54.35%; Region 10 rate of PHH or death = 49.17%, Region 11 rate of PHH or death = 37.98%.

Discussion

We observed decreased rates of severe IVH in VLBW infants in California with an accompanying decrease in the rates of PHH treatment or infant death among VLBW infants with severe IVH within the study period. We show that as many as 75% of patients who undergo a temporizing treatment eventually go on to require permanent PHH treatment with a CSF shunt, which is consistent with prior studies. In our multivariate model, we show that differences in the birth hospital region play a significant role in the composite poor outcome. Additionally, our data suggests that higher AAP NICU levels may be associated with increased odds of the composite poor outcome—a finding that likely reflects the increased complexity of cases that are managed in these settings. Our data highlights regional variation in the rates of post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus or death following severe IVH across California. Considering the regional differences in the composite outcome of PHH or infant death, perhaps our most striking finding is the wide variation in neurosurgical care—with rates of shunt-first neurosurgical treatment approach ranging from 25.53% to 81.48% across California perinatal regions.

While many maternal, infant, and early postnatal characteristics are well established to be associated with higher mortality risk in VLBW infants or the risk of severe IVH in this population, the risk factors for subsequent PHH are less well-established. We identified maternal race/ethnicity as a risk factor for PHH treatment or infant death. Infants born to non-Hispanic white mothers had the highest rates of PHH treatment or infant death, while infants born to Hispanic mothers had the lowest rates of PHH treatment or infant death in this cohort. It is unclear what is driving this racial/ethnic disparity. While we hypothesized that region and NICU level might be underlying this trend, maternal race/ethnicity remained significant in our multivariate model when accounting for region and NICU level. It is possible that this simply reflects a higher rate of withdrawal of life-sustaining or supporting measures in non-Hispanic white infants than in Hispanic and Black infants. This trend has previously been observed in extremely low gestational age infants with severe perinatal brain injury [12].

In our multivariate model, we also identified factors protective against PHH treatment or infant death. The relationship of infant PDA to the composite outcome is not entirely clear, though the coding of PDA may be indicative of a PDA significant enough to require treatment. This would be consistent with the findings of the Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TIPP), which showed that prophylactic indomethacin reduced severe IVH risk in preterm infants, although ultimately there was no improvement in long-term outcomes with prophylactic indomethacin [13,14,15]. Antenatal magnesium sulfate and infant NSAID exposure were also associated with lower risk of PHH treatment or infant death in this cohort. Both represent potential neuroprotective approaches that may warrant further investigation.

While no consensus exists among neonatologists and pediatric neurosurgeons as to the ideal timing of intervention in the care for infants with severe IVH and developing PHH, there has been a recent trend toward earlier intervention. Following this trend, some centers initiate temporizing interventions based on cranial ultrasound measurements of ventriculomegaly, in the absence of overt symptoms of intracranial hypertension, while others wait until visible clinical symptoms of hydrocephalus are observed [2]. Historically, North American practice patterns have gravitated toward later intervention for post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilation, while our European colleagues have favored earlier intervention [1, 16,17,18]. Further, evidence is mounting that late intervention—after clinical signs have developed—is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes, supporting the rationale for earlier intervention based on radiographic parameters alone and not waiting for clinical symptoms to arise. The early versus late ventricular intervention study (ELVIS) compared the effect of intervention at a low ventriculomegaly threshold (VI of >p97 and AHW of >6 mm) with a high ventriculomegaly threshold (VI of >p97 + 4 mm and AHW of >10 mm) on their primary outcomes of death or severe neurodevelopmental disability [19]. Earlier intervention was associated with decreased odds of death or severe neurodevelopmental disability in preterm infants with PHVD [19]. Cizmeci and colleagues showed in a sub-study of the ELVIS trial that more brain injury and increased ventricular volumes were associated with late neurosurgical intervention in the care for infants with post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation [6]. In the high threshold group (i.e., late intervention), higher Kidokoro scores were observed (an MR-based measurement of brain abnormalities in preterm infants), compared to infants in the low threshold group [6, 20]. These results provided support for early intervention in the care for VLBW infants with PHH.

The neurodevelopmental implications of timing of treatment are further magnified when the question is raised whether to treat with a temporizing measure prior to permanent CSF diversion (vs. shunt-first approach). Neurosurgical treatment of post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus is broadly categorized by temporizing treatment or permanent neurosurgical intervention [2, 10]. Temporizing treatments involve cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion via the placement of a ventricular access device for serial ventricular taps, ventriculo-subgaleal shunt, or an external ventricular drain [1, 10, 21, 22]. The standard of care permanent neurosurgical treatment for neonatal hydrocephalus is a CSF shunt. A shunt-first approach necessitates waiting until an infant is close to term equivalency—which often equates to operating on an infant that has developed quite severe ventricular enlargement and overt symptoms of intracranial hypertension. In many academic centers, temporizing treatments are used to halt the progression of ventriculomegaly and alleviate symptoms of clinical hydrocephalus before they become severe—until the infant is large enough to be treated definitively with a shunt. Isaacs and colleagues, in a multicenter study by the Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network (HCRN) comparing neurodevelopmental outcomes following temporary and permanent CSF diversion in preterm neonates with PHH, observed lower cognitive scores in patients who underwent initial permanent CSF diversion compared to patients initially temporized [23]. Additionally, among the 106 patients included in their observational cohort study, permanent CSF diversion was the PHH treatment strategy in 14% of patients, while 86% initially underwent temporizing CSF diversion [23]. Our study highlights that contrary to standard practices in many academic centers and an emerging body of evidence favoring earlier interventions for PHH, a shunt-first approach is the current predominant practice in California. Further, the predominance of this “shunt-1st” practice pattern is highly variable across the state and may reflect regional variability in direct access to pediatric neurosurgical care. Our findings are consistent with national data, also reflecting significant variability in approaches to PHH management [24, 25]. In a multicenter cohort study of 41 referral Level 1 V NICUs across North America, Sewell et al. also demonstrated significant heterogeneity in the rates, types, and timing of interventions for neonates with PHH—with 36% with no surgical intervention, 16% with a temporizing intervention only, 19% with a “shunt-1st“ approach (contrasting our findings in California), and 30% with a temporizing intervention followed by a shunt [24]. While a significant limitation of our study is a lack of granular data regarding the post-menstrual age of infants at the timing of intervention either with temporizing CSF diversion or permanent shunt placement, we utilized analysis of trends in “shunt-1st” approach as a surrogate for late intervention, given the practical limitations that prevent a shunt from being placed early in the clinical course for VLBW premature infants. We recognize that this is an imperfect measure, but the best available surrogate for late intervention in this cohort. The neurodevelopment consequences of this practice pattern in California are not known but require further study.

The vast regional variation in outcomes for VLBW infants with severe IVH, as well as the significant regional variation in neurosurgical practice patterns, identifies an opportunity for improvement. We anticipate that regional variation in the use of a shunt-first approach is likely indicative of variable access to pediatric neurosurgical care. Regions that have limited access to pediatric neurosurgical care may have neurosurgical care provided by a general (adult) neurosurgeon, as pediatric neurosurgical sub-specialty training (and board-certification) requirements are not uniform across the state but determined by each hospital’s credentialing board. Shunt placement by a general/adult neurosurgeon may be associated with a favored shunt-1st approach and a later timing of initial treatment for post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus. However, even these granular details are not currently known. Given this consideration, improved access to pediatric neurosurgical care and standardization of guidelines for thresholds for neurosurgical intervention may represent an initial step forward. In the current era of telehealth access, pediatric neurosurgical consultation can feasibly be provided even when neurosurgical provider is not physically present at the bedside. This may represent an opportunity for improvement to bridge gaps in access to pediatric neurosurgical care.

Regardless of the underlying driving factors, the observed variation in outcomes for severe IVH and neurosurgical practices for managing PHH represents an opportunity to evaluate associated neurodevelopmental outcomes and implement efforts to standardize neonatal and pediatric neurosurgical care [2, 25]. There is a clear need for regional and national collaboration between pediatric neurosurgeons and neonatologists that particularly focuses on this at-risk neonatal population. This was well demonstrated by a cross-sectional survey by Cohen et al. that showed approximately half of the neonatologists and pediatric neurosurgeon respondents did not agree on most aspects of PHH care [25]. Adoption of standardized practices for management of developing PHH in severe IVH will allow for prospective evaluation of outcomes and implementation of interventions for quality improvement.

This study should be viewed considering its design. Because of its observational nature, findings are subject to unobserved confounding, and causality should not be inferred. Nevertheless, many associations extend and confirm the existing literature. One limitation of our study is that the CPQCC does not collect data on lumbar punctures (LPs) completed during the infant’s hospitalization. Thus, we are unable to determine if LPs were utilized as a temporizing measure for the infants in the “shunt-first” category. However, given that infants for whom a temporizing measure is needed require regular and frequent treatment for weeks to months, it is unlikely and impracticable that LPs were carried out daily over an extended time prior to shunt implantation. Finally, while our findings reflect a population-based cohort of Californians, it is unclear how the findings may generalize to other regions in the United States. However, every 8th baby in the United States is born in California, a state with diverse geography, population, and health care delivery systems, supporting representativeness.

Conclusion

We observed declining rates of PHH treatment or infant death in at-risk neonates with severe IVH in California over a 16-year period— concordant with declining severe IVH rates. However, we observed significant regional variability in neurosurgical practice patterns for PHH across California, with the predominance of a “shunt-first” approach, consistent with later timing of intervention—an approach that a mounting body of evidence suggests leads to poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes.

This study highlights the urgent need to understand regional barriers in access to pediatric neurosurgical care and to adopt standard practices in the management of infants with severe IVH and developing post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus—across California and North America.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed for this study are sourced from the CPQCC and can be made available for reasonable requests.

References

Whitelaw A, Aquilina K. Management of posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F229–33.

El-Dib M, Limbrick DD, Inder T, Whitelaw A, Kulkarni AV, Warf B, et al. Management of post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the infant born preterm. J Pediatr. 2020;226:16–27.e3.

Paulsen AH, Lundar T, Lindegaard K-F. Pediatric hydrocephalus: 40-year outcomes in 128 hydrocephalic patients treated with shunts during childhood. Assessment of surgical outcome, work participation, and health-related quality of life. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16:633–41.

Mansoor N, Solheim O, Fredriksli OA, Gulati S. Shunt complications and revisions in children: a retrospective single institution study. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e2390.

Robinson S. Neonatal posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus from prematurity: pathophysiology and current treatment concepts. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9:242–58.

Cizmeci MN, Khalili N, Claessens NH, Groenendaal F, Liem KD, Heep A, et al. Assessment of brain injury and brain volumes after posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: a nested substudy of the randomized controlled ELVIS trial. J Pediatr. 2019;208:191–7.e2.

Reddy GK, Bollam P, Caldito G. Long-term outcomes of ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery in patients with hydrocephalus. World Neurosurg. 2014;81:404–10.

Stein SC, Guo W. Have we made progress in preventing shunt failure? A critical analysis. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:40–7.

Hauptman JS, Kestle J, Riva-Cambrin J, Kulkarni AV, Browd SR, Rozzelle CJ, et al. Predictors of fast and ultrafast shunt failure in pediatric hydrocephalus: a hydrocephalus clinical research network study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2020;27:277–86.

Kuo MF. Surgical management of intraventricular hemorrhage and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus in premature infants. Biomed J. 2020;43:268.

Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–34.

Dworetz AR, Natarajan G, Langer J, Kinlaw K, James JR, Bidegain M, et al. Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment in extremely low gestational age neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106:05–01.

Fowlie PW, Davis PG. Cochrane review: prophylactic intravenous indomethacin for preventing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:416–71.

Schmidt B, Seshia M, Shankaran S, Mildenhall L, Tyson J, Lui K, et al. Trial of indomethacin prophylaxis in preterms investigators. Effects of prophylactic indomethacin in extremely low-birth-weight infants with and without adequate exposure to antenatal corticosteroids. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:642–6.

Schmidt B, Davis P, Moddemann D, Ohlsson A, Roberts RS, Saigal S, et al. Long-term effects of indomethacin prophylaxis in extremely-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1966–72.

Kahle KT, Kulkarni AV, Limbrick DD, Warf BC. Hydrocephalus in children. lancet. 2016;387:788–99.

Riva-Cambrin J, Shannon CN, Holubkov R, Whitehead WE, Kulkarni AV, Drake J, et al. Center effect and other factors influencing temporization and shunting of cerebrospinal fluid in preterm infants with intraventricular hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9:473–81.

Leijser LM, Miller SP, van Wezel-Meijler G, Brouwer AJ, Traubici J, van Haastert IC, et al. Posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in preterm infants: when best to intervene?. Neurology. 2018;90:e698–706.

Cizmeci MN, Groenendaal F, Liem KD, van Haastert IC, Benavente-Fernández I, van Straaten HL, et al. Randomized controlled early versus late ventricular intervention study in posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation: outcome at 2 years. J Pediatr. 2020;226:28–35.

Kidokoro H, Neil JJ, Inder TE. New MR imaging assessment tool to define brain abnormalities in very preterm infants at term. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2208–14.

Christian EA, Jin DL, Attenello F, Wen T, Cen S, Mack WJ, et al. Trends in hospitalization of preterm infants with intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus in the United States, 2000–2010. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016;17:260–9.

Köksal V, Öktem S. Ventriculosubgaleal shunt procedure and its long-term outcomes in premature infants with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Child Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1505–15.

Isaacs AM, Shannon CN, Browd SR, Hauptman JS, Holubkov R, Jensen H, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of permanent and temporary CSF diversion in posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus: a Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2025;35:315–26.

Sewell E, Cohen S, Zaniletti I, Couture D, Dereddy N, Coghill CH, et al. Surgical interventions and short-term outcomes for preterm infants with post-haemorrhagic hydrocephalus: a multicentre cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025;110:10–6.

Cohen S, Mietzsch U, Coghill C, Dereddy N, Ducis K, Ters NE, et al. Survey of quaternary neonatal management of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40:883–92.

Funding

Support for this work was provided by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award, Stanford KL2 Mentored Career Development Award KL2TR003143 (Mahaney), and NICHD R01HD083368 (Profit).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Stanford Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study. Due to its retrospective observational nature and the absence of clinical interventions, parental consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahaney, K.B., Cheetham-West, A., Cui, X. et al. Wide variation in death rates and post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus (PHH) treatment in preterm severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). J Perinatol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02528-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02528-2