Abstract

In recent years great progress has been made in understanding the classification of lymphomas. The integration of morphologic, clinical, immunophenotypic, and molecular features provides a rational basis for defining disease entities and has led to worldwide consensus. Hematopathologists and dermatopathologists have worked together to define those lymphomas that are present most commonly in the skin. Some cutaneous lymphomas have distinctive features and differ from their nodal counterparts. This is most evident in the delineation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma and primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma. Both are very indolent, with low risk to spread beyond the skin. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma shows evidence of immunoglobulin class switching, as distinct from involvement by other extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of MALT type, which may involve the skin secondarily. Some have suggested that primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma may be considered a benign clonal expansion, probably driven by antigen. Many cutaneous lymphomas share biological and clinical features with their systemic counterparts. For example, primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma, leg type, exhibits a similar gene expression and molecular profile as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the activated B-cell type, especially for those cases arising in other extranodal sites. In addition, Epstein–Barr virus plays a role in many cutaneous lesions including mucocutaneous ulcer, plasmablastic lymphoma, and even some cases of marginal zone lymphoma. These EBV-driven conditions may present primarily in the skin, but also involve other mainly extranodal sites. Thus, it is evident that some cutaneous and systemic lymphomas are driven by common pathogenetic mechanisms, necessitating an integrated approach for the classification of lymphoma in all sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cutaneous lymphomas are heterogenous and show variations in histology, immunophenotype, and prognosis. At the time of presentation, cutaneous lymphomas may be primary or may involve the skin as a secondary site of involvement. Primary cutaneous lymphomas in many instances are distinct from morphologically similar lymphomas arising in lymph nodes. Their natural history is often more indolent than nodal lymphomas, and for that reason they often require different therapeutic approaches. Moreover, for many types of lymphomas, the site of presentation may be an indication of underlying biological distinctions. However, it is also apparent that genomic studies have shown unexpected links between lymphomas in diverse anatomic sites. Therefore, organ-specific schemes may impede our understanding of these common pathogenetic mechanisms. In addition, some lymphomas presenting primarily in the skin may be a manifestation of systemic disease, such as intravascular large B-cell lymphoma.

For optimal clinical management, the practicing dermatologist and dermatopathologist must have an appreciation of both primary and secondary cutaneous lymphomas. Moreover, it is important for clinical oncologists and dermatologists to speak a common language. This review will focus on those B-cell lymphomas either primary in the skin, or frequently having an initial presentation in the skin. The publication of the WHO-EORTC classification in 2005 was a culmination of a successful collaboration between hematopathologists and dermatopathologists to improve our understanding of cutaneous lymphomas [1]. With advances in our knowledge, appropriate updates have been made and incorporated in the new editions of the WHO Bluebooks for the classification of tumors of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues [2] and skin [3, 4].

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL)

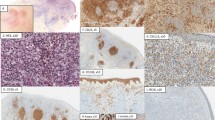

PCFCL is the most common type of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with a predilection for the scalp, forehead, and upper trunk (Table 1) [5]. Lesions are generally present as a single, raised nodule, with overlying intact epidermal surface and mildly erythematous appearance. Satellite lesions are common, but widespread cutaneous involvement does not occur. The infiltrate is based in the superficial dermis, with an intact grenz zone. The growth pattern varies, and may be follicular, follicular, and diffuse, or in some cases purely diffuse (Fig. 1). The cytological composition exhibits varying proportions of cells resembling centrocytes and centroblasts. Large centrocytes with dispersed chromatin and small nucleoli are especially common. However, confluent sheets of centroblasts or immunoblasts should be absent, and if present, a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma should be considered. Admixed small lymphocytes, notably T cells, are often abundant.

Immunophenotypically, the cells express CD20 and PAX5 and are generally positive for the germinal center-associated marker BCL6, but BCL2 and CD10 are usually negative [6, 7]. CD10 is positive in fewer than 25% of cases, and usually expressed only in cases with a follicular growth pattern [7]. Positive staining for IRF4/MUM1 should prompt consideration for primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma (PCLBCL), leg type. PCFCL generally lack translocations involving BCL2, the hallmark of nodal follicular lymphoma [8]. However, cases positive for either a BCL2 break by fluorescence in situ hybridization, or BCL2 protein may be at higher risk for systemic disease, and may represent occult secondary involvement of the skin [9]. Moreover, the combination of staining for both BCL2 and CD10 is highly suggestive of secondary involvement [10]. CD10 deletion at 1p36 may be found in PCFCL [11]. This aberration is common to many types of B-cell lymphoma of follicle center derivation, including diffuse nodal variants with bulky inguinal lymphadenopathy and pediatric-type follicular lymphoma [12, 13]. These findings indicate that some molecular alterations may be common to B-cell lymphomas of diverse types.

PCFCL has an excellent prognosis. Most cases, presenting with a single cutaneous lesion, can be treated with local therapy, either surgical excision or local radiation [14]. This holds true even for cases of PCFCL with a relatively high content of large cells, typically large centrocytes.

PCLBCL, leg type

PCLBCL, leg type, as the name implies, frequently presents on the skin of the lower extremities [15, 16]. It is seen mainly in older patients and is more common in females than males. It has an aggressive clinical course, and requires systemic therapy, in contrast to PCFCL. Like PCFCL, there is grenz zone, without epidermal involvement. The cells show a sheet-like pattern of growth, without infiltrating T cells or stromal reaction (Fig. 2). Cytologically, the infiltrate is monomorphic, composed of round cells, and resembling either centroblasts or immunoblasts [15].

The immunophenotype of PCLBCL-leg type resembles that of the activated B-cell (ABC) type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The cells are positive for IRF4/MUM1, BCL2, and usually BCL6, but negative for CD10. FOXP1 is positive in most cases. The gene expression profile, as the immunophenotype suggests, is indicative of an ABC stage of differentiation [17, 18].

Recent studies have shown a similar pattern of somatic mutations in PCLBCL-leg type, ABC DLBCL, and primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system [19,20,21]. Mutations of MYD88 L265P are most common, but mutations in PIM1, and CD79B are also seen. Approximately one-third of PCLBCL-leg type show MYC rearrangement, but “double-hit” translocations are rare [22]. MYCR cases have an adverse prognosis. These common pathogenetic mechanisms are mainly associated with extranodal lymphomas of ABC type presenting in the skin, testis, and central nervous system [23, 24].

Borderline cases and histological progression

Not every cutaneous B-cell lymphoma biopsy fits neatly into PCFCL and PCLBCL-leg type. Some cases may require a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS), and the WHO classification allows for such cases in the skin [2]. For example, some tumors composed of sheets of centroblasts may fulfill the criteria for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of germinal center B-cell type (Fig. 3). They may exhibit aggressive cytological and histological features but lack the ABC phenotype of PCLBCL-leg type. Such cases were probably included in the series reported by Senff et al., in which 11 patients, classified as PCFCL, presented with lesions on the lower leg, and had an aggressive clinical course, similar to that of PCFCL, leg type [7]. Therefore, the pathologist needs to base the final diagnosis on both the histological features as well as the immunophenotype, and as always the clinical presentation and extent of disease are relevant. In addition, PCFCL may rarely show evidence of histological progression and “transformation” to a histologically more aggressive process.

Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (PCMZL)

PCMZL shares many features with extranodal marginal zone lymphomas in other sites, but also exhibits key differences, and should be recognized as an independent entity. PCMZL most often presents as cutaneous nodules on the extremities. Patients are at risk for local recurrences, but systemic involvement with involvement of lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow is exceeding rare. Edinger et al. noted that in fact marginal zone lymphomas presenting in the skin included two major types [25]. In one subset, the atypical B cells had evidence of class switching, and expressed IgG, and less commonly IgA. These cases arose in a T-cell helper type 2 environment and generally lacked CXCR3 expression [26]. A second subtype was generally positive for IgM. The IgM-positive cases were much more likely to represent cutaneous MZL as a secondary site of disease, with evidence of marginal zone lymphoma in other extranodal sites. The IgM-positive cases show histological differences as well [27]. They were more likely to involve the subcutis. In addition, the IgM-positive plasmacytoid cells were scattered in a polymorphous background, and less likely to show a perifollcular distribution.

PCMZL frequently shows evidence of plasmacytic differentiation and can become more progressively plasmacytic over time with local cutaneous recurrences. Cases with these histological features historically were sometimes referred to as immunocytoma, but are part of the morphological spectrum of PCMZL [28]. The cells are positive for cytoplasmic kappa or lambda light chains, and frequently downregulate CD20 and PAX5. Expression of IgG4 is relatively common [27, 29]. As with other forms of MZL, there may be evidence of antigen drive, and a link to infection with Borrelia burgdorferi was shown in some cases [30], but generally not found widely in subsequent work. Borrelia can also elicit marked cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and may simulate lymphoma in some cases [31].

PCMZL also differ from other extranodal marginal zone lymphomas of mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) at the genetic level. Translocations that are relatively common in extranodal MALT lymphomas are very rare in cases presenting in the skin, overall seen in fewer than 10% of cases [32]. The most common recurrent translocation in cutaneous cases is t(14;18)(q32;q31), involving IGH and MALT1. It is seen in up to 15% of cases [33].

The prognosis in PCMZL is excellent, with disease-specific survival greater than 95% [14]. Patients should be managed conservatively, and indeed, it could be questioned whether most cases of PCMZL actually represent a benign clonal expansion of B cells to an unknown antigenic stimulus [34]. The distinction between PCMZL with IgG/IgG4-positive plasma cells and cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia can be challenging [35]. No doubt some cases previously diagnosed as cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia with monotypic plasma cells would be interpreted today as part of the spectrum of PCMZL [35]. In PCMZL well-formed germinal centers are generally present, and the monotypic plasma cells have a perifollicular distribution, mimicking a reactive process. A recent study identified recurrent alterations in FAS [36], suggesting that genetic sequencing may be a useful diagnostic tool in the future.

Cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas, positive for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

Gibson et al. reported four cases of cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type following solid organ transplantation, identifying this lesion as a new form of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) [37]. The cases reported included both children and adults, and presented mainly as subcutaneous nodules. The cells showed marked plasmacytic differentiation, with light chain restriction. In their original report most of the cases were positive for IgA. Unlike other cases of PTLD, the lesions lack necrosis, and histologically resembled cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas negative for EBV (Table 2). The lesions appeared to show a latency 2 phenotype, being positive for EBER RNA, with few cells positive for latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), but negative for EBV-associated nuclear antigen-2 (EBNA2).

More recently, Gong et al. reported an expanded spectrum of EBV-positive marginal zone lymphoma [38]. These cases arose in a variety of settings of immune deficiency including other forms of iatrogenic immune suppression besides solid organ transplant, immune senescence associated with advanced age, and congenital immune deficiency. The clinical spectrum was also broader than that reported by Gibson et al. While four cases presented in skin and subcutaneous sites, other sites of involvement included parotid gland, lung, breast, and lymph node in one case. The immunophenotype differed somewhat from the prior series, since the cases expressed IgG and IgM, and did not show preferential expression of IgA.

Knowledge of EBV-positive MZL is important, because histological features closely resemble those of MZL, negative for EBV, and an association with EBV may not be suspected. A history of underlying immune deficiency should prompt studies for EBV with EBER in situ hybridization. LMP1 may be positive by immunohistochemistry in a small subset of the lymphoid cells, but it is not reliably positive to facilitate accurate diagnosis. As with other EBV-driven lesions, in a patient with a history of iatrogenic immune suppression, withdrawal of immune suppression may lead to regression. Rituximab therapy has also been used with success [38]. The genetic basis of EBV-positive MZL is largely unknown. Investigation for MYD88 L265P mutation was negative, showing no overlap with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia [38, 39]. However, it is unknown if other aberrations associated with MZL negative for EBV are present.

Mucocutaneous ulcer (MCU)

EBV-positive MCU was first described by Dojcinov et al. as a novel, extranodal, EBV-driven B-cell proliferation associated with decreased immune surveillance [40]. In the original report, immunosenescence associated with advanced age was the main underlying cause, but some patients also had evidence of iatrogenic immune suppression for immune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis [41, 42]. All patients had localized disease, and there were no disease related deaths. Since that report, MCU was reported as a form of PTLD in patients who received iatrogenic immune suppression for a solid organ transplant [43]. Patients responded well to reduction of immune suppression, with or without rituximab therapy, and no patient had recurrence of the EBV-driven process. More recently two cases of cutaneous MCU were reported in patients who had received therapy for another unrelated primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder [44]. In this setting correct diagnosis was key to appropriate therapy, as rituximab led to regression in both cases.

The oropharyngeal mucosa is the most common site of presentation for MCU. Cutaneous presentations occur in ~25% of cases (Fig. 4) [40]. It appears that underlying tissue damage may be an early event in the development of the ulcerative lesion, and that local tissue damage may provide an appropriate microenvironment for EBV expansion. This explains the high incidence of gingival lesions in elderly patients who may have poor dentition.

Cytologically EBV-positive MCU differs significantly from EBV-positive marginal zone lymphoma. The EBV-positive cells are large and pleomorphic, usually with prominent nucleoli, often bearing a resemblance to Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells (Fig. 5) [40, 45]. They are scattered in a polymorphous background with numerous reactive T cells and histiocytes. However, plasma cells and eosinophils are usually few in number. The overlying mucosa or epidermis is ulcerated, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia at the margins of the lesion. It is important to assess the base of the lesion in making the diagnosis. It should be sharply circumscribed, usually with abundant reactive T cells at the deepest extent of the lesion. Diffuse infiltration of underlying soft tissue by EBV-positive B cells should raise concern for a more aggressive process, such as EBV-positive large B-cell lymphoma, NOS, etc.

The large EBV-positive B cells are usually positive for CD20, PAX5, and CD79a, but expression may be weak and variable. LMP1 is expressed in at least some of the EBER-positive population. CD30 and IRF4/MUM1 are both positive and CD15 is expressed with some frequency, up to 50% of cases. Thus, the immunophenotype of the lesional cells resembles that of classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL). It is likely that many cases historically reported as CHL, EBV-positive, in cutaneous or mucosal sites were probably examples of MCU [46]. PCR studies for immunoglobulin gene rearrangement show evidence of a monoclonal process in 35–40% of cases [40].

Plasmablastic lymphoma

Plasmablastic lymphoma is the most aggressive of the B-cell lesions that present primarily in skin and mucosal associated sites. Approximately 75% of case are EBV-positive. In contrast to EBV-positive MCU, EBV-positive cases express EBER, but are negative for LMP1 and EBNA2, and have a latency I phenotype. Plasmablastic lymphoma was originally reported in the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients [47], but since then has been associated with a variety of immune deficiency states including immune senescence, and both congenital and acquired immune deficiency [48]. Oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract are the most common sites of presentation, and nodal involvement is relatively rare, seen in fewer than 15% of cases. Cutaneous involvement is present in some cases [49, 50]. Plasmablastic lymphomas are clinically aggressive. Histologically, they are composed of a sheet-like proliferation of cells resembling immunoblasts, with varying degrees of plasmacytic differentiation. Cases with evidence of plasmacytic differentiation are more likely to have nodal involvement, and are less frequently seen in patients with HIV infection [48]. Finally, there is a third group of plasmablastic lymphomas that occurs in patients with a prior diagnosis of a more low grade plasma cell neoplasm, such as plasma cell myeloma [48, 51]. These are generally present in extranodal sites, but cutaneous involvement is uncommon. As will be discussed below, there are common genomic alterations in plasmablastic lymphoma in these various clinical scenarios.

Plasmablastic lymphoma is a mature B-cell neoplasm that shows evidence of plasma cell differentiation phenotypically. The cells are negative for CD20 and PAX5, but variably positive for CD79a, CD38/CD138, IRF4/MUM1, and cytoplasmic immunoglobulin. CD30 is frequently positive, correlating with EBV-positivity. CD56 is usually negative, contrasting with the usual CD56 expression seen in plasma cell myeloma. Proteins associated with immune checkpoint inhibition (PD-1, PD-L1) are frequently expressed in the microenvironment, indicating a failure of immune surveillance [52]. A common feature of plasmablastic lymphoma is frequent MYC rearrangement, and MYC protein is usually positive by immunohistochemistry [51, 53, 54]. MYC rearrangement is a common secondary event in plasma cell myeloma [55, 56].

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LYG)

LYG is an EBV-positive extranodal lymphoproliferative disorder that nearly always presents in the lung, with other frequent sites of involvement being the kidney, liver, and central nervous system [57]. Cutaneous manifestations are common, but in most instances, EBV-positive B cells are not found in the skin [58]. The most common pattern of cutaneous involvement resembles subcutaneous lobular panniculitis, with an infiltrate composed mainly of T cells and histiocytes. Only in large nodular skin lesions are EBV-positive cells found with any frequency. It is doubtful that LYG isolated to the skin ever occurs, but as noted in this review, a variety of EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders can involve the skin, including MCU, EBV-positive marginal zone lymphomas, and plasmablastic lymphoma.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma has distinctive clinical and biological features [59]. The neoplastic cells are confined to the lumina of small blood vessels in extralymphatic sites. Skin involvement is relatively common, although most patients have widespread disseminated disease at presentation [60]. In rare cases the cells have localized within hemangiomatous lesions of the skin [61]. Patients require systemic chemotherapy. However, patients presenting with cutaneous disease have a better prognosis in most series, most likely due to early detection and treatment.

Cutaneous manifestations include erythematous patches and plaques with a predilection for the trunk and lower extremities. The lesions may have a telangiectatic appearance [62]. Lymph node involvement is rare. Brain and skin are the most frequently affected sites, but bone marrow involvement may be seen [60]. The patients commonly exhibit fever, constitutional symptoms, and mental status changes. The diagnosis is often elusive, because mass lesions are not produced, and the histologic findings are subtle. A subset of patients may present with hemophagocytosis, a finding more commonly seen in Asian countries [63].

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma has a mature B-cell phenotype but is commonly CD5-positive (Fig. 6). The checkpoint inhibitor PD-L1 is positive in about half of the cases [64]. The majority of cases are positive for IRF4/MUM1 and negative for CD10, suggesting an ABC phenotype. In keeping with the ABC origin, a high prevalence of MYD88 and CD79B mutations have been seen [65]. The lack of expression of the lymphocyte integrin CD29 has been postulated to play a role in the intravascular distribution, and failure of the cells to leave the circulation [63].

B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL/LBL)

Precursor neoplasms include both B-ALL/LBL and T-ALL/LBL. Both are considered systemic disorders that may as either leukemia or lymphoma. Despite many common biological features, such as an immature lymphoid phenotype and positivity for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT), differences in lineage and molecular pathogenesis lead to differences in clinical features. B-ALL/LBL more commonly involves the skin than T-ALL/LBL [66, 67].

B-ALL/LBL most commonly affects children and young adults. Frequent sites of cutaneous involvement are the head and neck region and may be the initial presenting site of disease. However, the risk of subsequent systemic disease is high, although leukemic involvement is relatively infrequent [68].

Clinically, the lesions appear as erythematous nodules, without epidermal involvement. The atypical cells percolate diffusely in the dermis, often with an Indian-file pattern. The cells resemble lymphoblasts with fine chromatin and sparse cytoplasm (Fig. 7). The cells are positive for TDT, and express CD79a and CD10. However, other more mature B cell associated antigens, such as CD20 are usually negative.

Secondary cutaneous involvement by B-cell lymphoma

Secondary involvement of the skin can be seen in virtually all subtypes of B-cell lymphoma. It is most common in those tumors that tend to present with advanced stage disease, e.g., Stage III or IV. As such, cutaneous involvement can be seen chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. This most commonly occurs at the time of relapse rather than presentation. A somewhat recurring issue is the distinction of PCFCL from secondary involvement of the skin by follicular lymphoma. As noted, expression of both BCL2 and CD10 is much more often seen with secondary involvement by nodal follicular lymphoma [10].

References

Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–85.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2017.

Elder DE, Massi D, Scolyer RA, Willemze R. WHO classification of skin tumours. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018.

Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, Berti E, Facchetti F, Swerdlow SH, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703–14.

Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Mitteldorf C. Cutaneous lymphomas: an update. Part 2: B-cell lymphomas and related conditions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:197–208. quiz 9–10.

Hoefnagel JJ, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, Fleuren GJ, Meijer C, Willemze R. Bcl-2, Bcl-6 and CD10 expression in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: further support for a follicle centre cell origin and differential diagnostic significance. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1183–91.

Senff NJ, Hoefnagel JJ, Jansen PM, Vermeer MH, van Baarlen J, Blokx WA, et al. Reclassification of 300 primary cutaneous B-Cell lymphomas according to the new WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas: comparison with previous classifications and identification of prognostic markers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1581–7.

Kim BK, Surti U, Pandya A, Cohen J, Rabkin MS, Swerdlow SH. Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular cytogenetic fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of primary and secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:69–82.

Lucioni M, Berti E, Arcaini L, Croci GA, Maffi A, Klersy C, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma other than marginal zone: clinicopathologic analysis of 161 cases: Comparison with current classification and definition of prognostic markers. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2740–55.

Servitje O, Climent F, Colomo L, Ruiz N, Garcia-Herrera A, Gallardo F, et al. Primary cutaneous vs secondary cutaneous follicular lymphomas: A comparative study focused on BCL2, CD10, and t(14;18) expression. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:182–9.

Szablewski V, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Baia M, Delfau-Larue MH, Copie-Bergman C, Ortonne N. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphomas expressing BCL2 protein frequently harbor BCL2 gene break and may present 1p36 deletion: a study of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:127–36.

Katzenberger T, Kalla J, Leich E, Stocklein H, Hartmann E, Barnickel S, et al. A distinctive subtype of t(14;18)-negative nodal follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by a predominantly diffuse growth pattern and deletions in the chromosomal region 1p36. Blood. 2009;113:1053–61.

Schmidt J, Gong S, Marafioti T, Mankel B, Gonzalez-Farre B, Balague O, et al. Genome-wide analysis of pediatric-type follicular lymphoma reveals low genetic complexity and recurrent alterations of TNFRSF14 gene. Blood. 2016;128:1101–11.

Senff NJ, Hoefnagel JJ, Neelis KJ, Vermeer MH, Noordijk EM, Willemze R. Results of radiotherapy in 153 primary cutaneous B-Cell lymphomas classified according to the WHO-EORTC classification. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1520–6.

Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, Maubec E, Bagot M, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144–50.

Vermeer MH, Geelen FA, van Haselen CW, van Voorst Vader PC, Geerts ML, van Vloten WA, et al. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas of the legs. A distinct type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with an intermediate prognosis. Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working Group. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1304–8.

Hoefnagel JJ, Dijkman R, Basso K, Jansen PM, Hallermann C, Willemze R, et al. Distinct types of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Blood. 2005;105:3671–8.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82.

Mareschal S, Pham-Ledard A, Viailly PJ, Dubois S, Bertrand P, Maingonnat C, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type by massive parallel sequencing. J Investig Dermatol. 2017;137:1984–94.

Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Lim KH, et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature. 2011;470:115–9.

Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, Johnson CA, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1396–407.

Schrader AMR, Jansen PM, Vermeer MH, Kleiverda JK, Vermaat JSP, Willemze R. High incidence and clinical significance of MYC rearrangements in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1488–94.

Deng L, Xu-Monette ZY, Loghavi S, Manyam GC, Xia Y, Visco C, et al. Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma displays distinct clinical and biological features for treatment failure in rituximab era: a report from the International PTL Consortium. Leukemia. 2016;30:361–72.

Kraan W, Horlings HM, van Keimpema M, Schilder-Tol EJM, MECM Oud, Scheepstra C, et al. High prevalence of oncogenic MYD88 and CD79B mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas presenting at immune-privileged sites. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e139.

Edinger JT, Kant JA, Swerdlow SH. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas have distinctive features and include 2 subsets. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1830–41.

van Maldegem F, van Dijk R, Wormhoudt TA, Kluin PM, Willemze R, Cerroni L, et al. The majority of cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphomas expresses class-switched immunoglobulins and develops in a T-helper type 2 inflammatory environment. Blood. 2008;112:3355–61.

Carlsen ED, Swerdlow SH, Cook JR, Gibson SE. Class-switched primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas are frequently IgG4-positive and have features distinct from IgM-positive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1403–12.

Duncan LM, LeBoit PE. Are primary cutaneous immunocytoma and marginal zone lymphoma the same disease? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1368–72.

Brenner I, Roth S, Puppe B, Wobser M, Rosenwald A, Geissinger E. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas with plasmacytic differentiation show frequent IgG4 expression. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1568–76.

Cerroni L, Zochling N, Putz B, Kerl H. Infection by Borrelia burgdorferi and cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:457–61.

Grange F, Wechsler J, Guillaume JC, Tortel J, Tortel MC, Audhuy B, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis simulating a primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:530–4.

Streubel B, Simonitsch-Klupp I, Mullauer L, Lamprecht A, Huber D, Siebert R, et al. Variable frequencies of MALT lymphoma-associated genetic aberrations in MALT lymphomas of different sites. Leukemia. 2004;18:1722–6.

Streubel B, Lamprecht A, Dierlamm J, Cerroni L, Stolte M, Ott G, et al. T(14;18)(q32;q21) involving IGH and MALT1 is a frequent chromosomal aberration in MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:2335–9.

Swerdlow SH. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:76–84.

Schmid U, Eckert F, Griesser H, Steinke C, Cogliatti SB, Kaudewitz P, et al. Cutaneous follicular lymphoid hyperplasia with monotypic plasma cells. A clinicopathologic study of 18 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:12–20.

Maurus K, Appenzeller S, Roth S, Kuper J, Rost S, Meierjohann S, et al. Panel sequencing shows recurrent genetic FAS alterations in primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma. J Investig Dermatol. 2018;138:1573–81.

Gibson SE, Swerdlow SH, Craig FE, Surti U, Cook JR, Nalesnik MA, et al. EBV-positive extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in the posttransplant setting: a distinct type of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder? Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:807–15.

Gong S, Crane GM, McCall CM, Xiao W, Ganapathi KA, Cuka N, et al. Expanding the spectrum of EBV-positive marginal zone lymphomas: a lesion associated with diverse immunodeficiency settings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1306–16.

Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, Cao Y, et al. MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. New Engl J Med. 2012;367:826–33.

Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer–a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:405–17.

Koens L, Senff NJ, Vermeer MH, Willemze R, Jansen PM. Methotrexate-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders presenting in the skin: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypical study of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:999–1006.

Satou A, Banno S, Hanamura I, Takahashi E, Takahara T, Nobata H, et al. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer arising in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate: Single center series of nine cases. Pathol Int. 2019;69:21–8.

Hart M, Thakral B, Yohe S, Balfour HHJ, Singh C, Spears M, et al. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer in organ transplant recipients: a localized indolent posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1522–9.

Craddock LN, Inda JJ, Longley BJ, Wood GS. EBV(+) mucocutaneous ulcers in the setting of pre-existing cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a report of 2 cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:78–81.

Gru AA, Jaffe ES. Cutaneous EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:60–75.

Kumar S, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kingma DW, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive primary gastrointestinal Hodgkin’s disease: association with inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:66–73.

Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413–20.

Colomo L, Loong F, Rives S, Pittaluga S, Martinez A, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with plasmablastic differentiation represent a heterogeneous group of disease entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:736–47.

Hausermann P, Khanna N, Buess M, Itin PH, Battegay M, Dirnhofer S, et al. Cutaneous plasmablastic lymphoma in an HIV-positive male: an unrecognized cutaneous manifestation. Dermatology. 2004;208:287–90.

Nicol I, Boye T, Carsuzaa F, Feier L, Collet Villette AM, Xerri L, et al. Post-transplant plasmablastic lymphoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:889–91.

Taddesse-Heath L, Meloni-Ehrig A, Scheerle J, Kelly JC, Jaffe ES. Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:991–9.

Laurent C, Fabiani B, Do C, Tchernonog E, Cartron G, Gravelle P, et al. Immune-checkpoint expression in Epstein-Barr virus positive and negative plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinical and pathological study in 82 patients. Haematologica 2016;101:976–84.

Valera A, Balague O, Colomo L, Martinez A, Delabie J, Taddesse-Heath L, et al. IG/MYC rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1686–94.

Montes-Moreno S, Martinez-Magunacelaya N, Zecchini-Barrese T, Villambrosia SGd, Linares E, Ranchal T, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma phenotype is determined by genetic alterations in MYC and PRDM1. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:85–94.

Kuehl WM. Modeling multiple myeloma by AID-dependent conditional activation of MYC. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:85–7.

Gabrea A, Martelli ML, Qi Y, Roschke A, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy JD Jr., et al. Secondary genomic rearrangements involving immunoglobulin or MYC loci show similar prevalences in hyperdiploid and nonhyperdiploid myeloma tumors. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2008;47:573–90.

Song JY, Pittaluga S, Dunleavy K, Grant N, White T, Jiang L, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis–a single institute experience: pathologic findings and clinical correlations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:141–56.

Beaty MW, Toro J, Sorbara L, Stern JB, Pittaluga S, Raffeld M, et al. Cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis: correlation of clinical and biologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1111–20.

Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Facchetti F, Mazzucchelli L, Yoshino T, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3168–73.

Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, Willemze R, Ilariucci F, Ambrosetti A, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant’. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173–83.

Rubin MA, Cossman J, Freter CE, Azumi N. Intravascular large cell lymphoma coexisting within hemangiomas of the skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:860–4.

Ozguroglu E, Buyulbabani N, Ozguroglu M, Baykal C. Generalized telangiectasia as the major manifestation of angiotropic (intravascular) lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:422–5.

Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks. Blood. 2018;132:1561–7.

Gupta GK, Jaffe ES, Pittaluga S. A study of PD-L1 expression in intravascular large B cell lymphoma: correlation with clinical and pathological features. Histopathology. 2019;75:282–6.

Schrader AMR, Jansen PM, Willemze R, Vermeer MH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Somers SF, et al. High prevalence of MYD88 and CD79B mutations in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;131:2086–9.

Sander CA, Medeiros LJ, Abruzzo LV, Horak ID, Jaffe ES. Lymphoblastic lymphoma presenting in cutaneous sites. A clinicopathologic analysis of six cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1023–31.

Chimenti S, Fink-Puches R, Peris K, Pescarmona E, Putz B, Kerl H, et al. Cutaneous involvement in lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:379–85.

Lin P, Jones D, Dorfman DM, Medeiros LJ. Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: a predominantly extranodal tumor with low propensity for leukemic involvement. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1480–90.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute. This work was completed with the support of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaffe, E.S. Navigating the cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: avoiding the rocky shoals. Mod Pathol 33 (Suppl 1), 96–106 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0385-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0385-7