Abstract

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is subject to amplifying feedbacks which can accelerate ice loss and lead to effectively irreversible retreat. We here analyse the distinct nature and risk of long-term ice loss for each individual drainage basin under different levels of warming. Depending on topographic and climatic conditions, we find that ice loss in some basins unfolds gradually with warming, whereas other basins are characterized by a critical threshold or tipping point beyond which large parts eventually disintegrate. A first threshold, potentially as low as 1–2 °C above pre-industrial levels, triggers the long-term collapse of ~40% of marine ice volume in West Antarctica. Marine-based sectors in East Antarctica, representing ~5 m of potential sea-level rise, are at risk of losing stability at 2–5 °C. Our results imply that the Antarctic Ice Sheet does not act as one single tipping element, but rather as several tipping systems interacting across drainage basins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is the largest ice sheet on Earth with a mass equivalent to nearly 60 m of global sea-level rise potential1. Its stability and future response to a warming climate is therefore highly relevant for coastal communities, infrastructure and ecosystems2. Under future anthropogenic climate change, the ice sheet is ‘projected to lose mass at an increasing rate throughout the twenty-first century and beyond (high confidence)’2, which could commit future generations to long-term sea-level rise3,4, with subsequent impacts including coastal erosion, ecosystem loss, human livelihood and infrastructure displacement, increased hazards from storm surges and potential groundwater salinification5. Ice loss from Antarctica would also affect the Southern Ocean and could lead to a weakening of Antarctic bottom water formation6, which would have cascading effects on the global ocean and climate7,8,9.

Palaeorecords and modelling suggest that Antarctica has undergone periods of large-scale and abrupt ice loss in the past10,11,12,13. During past interglacial warm periods that were only slightly (~1–3 °C) warmer than today despite broadly comparable (~300–400 ppm) atmospheric CO2 concentrations, the Antarctic Ice Sheet probably contributed several metres to global sea level14,15, implying substantial retreat of marine ice-sheet regions in both West12,16,17 and East Antarctica18,19,20. In particular, meltwater pulses due to accelerated ice-sheet retreat in Antarctica during the last glacial termination might have caused sea levels to rise at rates of up to ~0.7 m per century (or ~7 mm yr−1) (ref. 21).

On the basis of these palaeoreconstructions as well as modelling studies and process understanding, the Antarctic Ice Sheet is deemed a tipping element in the climate system22,23,24,25. This means that beyond a critical threshold (or several thresholds), self-sustaining feedbacks can lead to abrupt and often irreversible ice loss, with far-reaching impacts on the Earth system via global sea-level rise and changes in atmospheric and oceanic conditions and circulation patterns.

Observations indicate that in particular the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has been losing mass at an accelerating pace over the last decades, leading to increasing contributions to global mean sea-level rise26,27. The Amundsen Sea Embayment sector in West Antarctica shows first signs of destablization in response to ocean-induced thinning that reduces ice-shelf buttressing28,29,30. Also, in Wilkes Land in East Antarctica, increased ice discharge has been observed in response to recent warming31.

While palaeoreconstructions and climate modelling suggest that snowfall in Antarctica will probably increase with global warming32,33,34—which can mitigate some of the expected ice loss35,36—enhanced ablation, dynamical losses and amplifying feedbacks will probably dominate the overall mass balance in the future37,38.

Among the most prominent amplifying feedbacks are the surface melt–elevation feedback39,40, the melt–albedo feedback41, the marine ice-sheet instability42,43 (MISI) and the potential marine ice cliff instability11,44,45 (MICI); and further amplifying feedbacks have been suggested46,47,48. As surface melt is still very limited in Antarctica because of the cold surface temperatures, the melt–elevation and melt–albedo feedbacks are probably going to become more relevant under future, considerably warmer, conditions49. Current mass loss is dominated by ocean-driven subshelf melting50,51,52,53 and iceberg calving51,54. In marine ice-sheet regions, where the ice rests on bedrock below sea level, this can trigger MISI, an amplifying feedback between grounding-line retreat and the ice flux across the grounding line42,43. In fact, recent studies suggest that parts of the Amundsen Sea Embayment region in West Antarctica might already be undergoing unstable retreat55,56,57,58 or that large-scale irreversible ice loss might be imminent59,60. Other subglacial basins in East Antarctica are also at risk of undergoing rapid ice loss due to MISI61,62. If MICI, the mechanical failure and consequent self-perpetuating collapse of tall ice cliffs44, were to be triggered, this would further increase the potential of abrupt ice loss11,63. However, observational constraints on the related processes are limited and large uncertainties remain regarding the imposed risks64,65. Moreover, the conditions and potential stabilizing processes, such as mélange buttressing66 or glacial isostatic adjustment67,68, might counteract these instability mechanisms. Overall, the future long-term evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheets depends on the complex interplay of these amplifying and dampening feedbacks, as well as its interactions with other parts of the global climate system69,70,71.

Future projections of contributions of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to sea-level rise hence involve large uncertainties38,72: While projections with multiple models range from 3 cm to 34 cm (likely range; 11–12 cm median, depending on shared socioeconomic pathway (SSP) scenario) global sea-level contribution from Antarctica by 2100 relative to 1995–20145, uncertainties increase drastically when considering timescales beyond the twenty-first century. In fact, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently assessed that 7–14 m of global mean sea-level contribution from Antarctica by 2300 cannot be ruled out5,63 especially because of the structural uncertainties posed by the MICI.

Owing to the long response times of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, some changes might be triggered in the coming decades, which then unfold over much longer timescales of centuries to millennia. The effective long-term change can be quantified as sea-level commitment3,4,73,74,75. Here we focus on these long-term consequences of global warming, assessing the equilibrium response and potential critical thresholds for different drainage basins. Theory and modelling suggest that the Antarctic Ice Sheet displays hysteresis behaviour, meaning that changes can become practically irreversible and the initial ice volume cannot be regained even if temperatures were reversed76. For instance, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would probably not regrow to its modern extent unless temperatures were to be at least one degree lower than pre-industrial levels.

Owing to the heterogenous topography of Antarctica as well as the varying atmospheric and oceanic conditions, this overall hysteresis behaviour could, however, comprise or even obscure individual tipping points in different ice-sheet drainage basins. In this study, we disentangle the dynamic response for 18 individual drainage basins (Methods; Fig. 1) to quantify potential thresholds and the respective contributions to global sea-level rise and to reveal the respective key driving processes. We then assess the risk—here understood as a combination of critical threshold temperature and the corresponding impact through sea-level rise—revealing the most critical basins that warrant particular attention in monitoring and future research.

Map of Antarctica showing the 18 ice-sheet drainage basins as used in this analysis (thin black lines; ref. 84) as well as their sea-level potential (in metres sea-level equivalent, m SLE), illustrated by the size of the respective circles. Nested circles show the critical temperature levels at which the strongest ice loss occurs in the model simulations (circle colour) as well as the fraction of ice volume lost in the long term upon transgression of those thresholds with respect to the initial ice volume of the basin (circle size). Background shading shows the bedrock topography (tan–brown above sea level, white–blue below sea level); ice shelves are highlighted by grey shading. AP, Antarctic Peninsula. Observed Antarctic topography from the Bedmap2 dataset (ref. 95).

Long-term simulations of Antarctic ice loss per basin

Here we identify the dynamic regimes and critical temperature thresholds leading to large-scale long-term ice loss in the drainage basins of Antarctica using the fully dynamic Parallel Ice Sheet Model77,78 (PISM). To assess the inherent (long-term) stability behaviour of the ice sheet, we apply a methodology which has been adopted previously to study the stability of some of the major climate components of Earth—among them, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation79,80,81, the Greenland Ice Sheet82, or the Antarctic Ice Sheet as a whole (not considering the per-basin contributions)76. The applied methodology consists of idealized warming experiments, in which, starting from an equilibrium reference ice-sheet state, the global mean temperature—defined here as the globally averaged surface air temperatures over land and ocean—is incrementally ramped up until complete deglaciation of all ice basins is achieved (Methods). As the applied warming rate is slower than the typical ice-sheet response times, it is ensured that the system is able to follow the change while at the same time remaining as close as possible to equilibrium. At each full degree, this quasi-static simulation is extended under fixed global mean temperature levels, until volume changes become negligible and the ice sheet reaches a steady state. While computationally more expensive than, for example, often-used step-forcing experiments (which could introduce abrupt transient effects), this approach ensures that we can identify critical thresholds or tipping points systematically, as the quasi-static state changes are an important prerequisite for a true stability assessment. This complements simulations which are based on faster transient forcing and provides more fundamental understanding to put, for instance, the response of the ice sheet to global warming overshoot scenarios into context.

We start our simulations from a reference equilibrium state closely resembling the pre-industrial Antarctic Ice Sheet configuration (Methods; Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2). Note that, while the steady state is prerequisite for our methodology, observations show that the Antarctic Ice Sheet has been subject to notable changes over the last decades as a consequence of anthropogenic climate change and isostatic rebound following the last glacial termination, suggesting that the ice sheet is not in equilibrium any longer27,83. However, since the observational data which are needed to form the geometric and climatic boundary conditions for the simulations are only available from the second half of the twentieth century, we interpret the pre-industrial ice-sheet configuration as the closest analogue to this equilibrium state. Any temperature anomalies are therefore taken with respect to pre-industrial levels. The ice drainage basin boundaries used in the analysis are based on the Antarctic drainage divides developed by ref. 84 (Methods; Extended Data Table 1).

Gradual decline versus tipping dynamics

The (quasi-)equilibrium states that the Antarctic Ice Sheet approaches at increasing levels of global warming (Extended Data Fig. 3) reveal qualitatively different modes of ice-sheet response to warming for different regions of the ice sheet. To disentangle these different dynamic responses, we examine the relative ice volume loss per degree of warming for each ice-sheet drainage basin. Despite the linear increments in temperature forcing, the response in many cases is strongly nonlinear and exhibits steps and distinct peaks for all 18 drainage basins (Fig. 2, grey bars). Overall, the ice response can be broadly categorized into either a rather gradual ice volume loss with warming (here termed ‘gradual decline’) or a threshold-type response (‘tipping dynamics’). Examples for the first case are Abbot/Venable, West Antarctic Peninsula (George VI) and Ronne, which lose their ice volume almost linearly or in several increments with warming (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Table 2). Examples for drainage basins exhibiting a nonlinear tipping point behaviour are Dronning Maud Land, Enderby Land, Amery, West/Denman, Totten/Moscow and Filchner in East Antarctica, as well as the Thwaites/Pine Island basin in West Antarctica. For these drainage basins, only small changes occur throughout a relatively large warming range, followed by abrupt and large-scale ice volume decline thereafter, with near-complete volume loss at only very little additional warming. This also suggests that the ice loss in these basins is mainly driven by dynamic instability mechanisms, such as MISI or the surface melt–elevation feedback.

For each ice basin, blue dots show the initial (at pre-industrial temperature levels) sea-level relevant ice volume (Methods) and the remaining steady-state ice volume for each global warming level. Grey histograms indicate the long-term ice loss per degree of warming, with dark grey bars marking the strongest decline for the basin. Inset maps show the location of the basin within Antarctica84.

The remaining Antarctic drainage basins show a combination of gradual decline and tipping dynamics. For example, Ross West (Siple Coast), Cook/Ninnis/Mertz and Victoria Land show abrupt change around ~1–3 °C of global warming above pre-industrial levels and gradual decline at higher warming levels. In contrast, Brunt/Riiser-Larsen, Ross East (Byrd), Getz, North Antarctic Peninsula (Larsen C) and East Antarctic Peninsula (Larsen D–G) show a gradual decline for lower warming levels but exhibit notable threshold behaviour at warming levels exceeding 6 °C above pre-industrial levels.

To identify in which one-degree temperature interval the highest relative ice loss for each basin occurs, we here identify critical temperature levels based on peak prominence (Fig. 2, dark grey bars). Here we only consider those peaks in ice loss where the prominence exceeds a minimum fraction of 15% of the initial ice volume of the basin. Note that these critical temperature levels can either be tipping points (their transgression causing abrupt ice loss) or simply the levels for which the highest ice loss occurs for a particular basin. In fact, we find that this 15% significance mark is transgressed in all basins at least once. In case of a double peak (for example, for Amery, West/Denman and Getz), we identify the entire two-degree temperature interval as critical. The Ronne, Filchner, Cook/Ninnis/Mertz and West Antarctic Peninsula (George VI) basins exhibit even two distinct thresholds (Figs. 1–3).

Bottom panel: burning embers show—for each of the 18 Antarctic ice basins—the percentage of long-term (equilibrium) sea-level relevant ice volume loss compared with the respective initial ice volume, at different levels of global warming (in °C above pre-industrial temperature levels, interpolated between full degrees). White diamonds mark the one-degree temperature interval of the strongest decline (ice loss per degree of warming, see also Fig. 2). In some basins, two critical temperatures yielding peak volume loss are found—this can be interpreted as the respective basin having two tipping points. Top panel: sea-level potential for each basin, given by the initial modelled sea-level relevant ice volume in metres sea-level equivalent.

Critical thresholds for ice basin stability

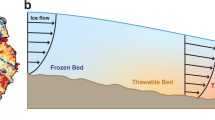

Of all Antarctic regions, the West Antarctic Thwaites/Pine Island, Ronne and Ross West (Siple Coast) basins are closest to their tipping points. With the lowest temperature threshold among all regions covered in our analysis, these basins are already at risk of substantial long-term ice loss below +1 °C of global warming above the pre-industrial reference temperature. At present, global mean warming has reached ~1.3 °C above the average temperatures of the second half of the nineteenth century. This suggests that these West Antarctic basins may already have passed a critical point at warming levels of the present, which could lead to their eventual disintegration (noting that this could take centuries to fully unfold)60,85. In the case of the Thwaites/Pine Island basin, this hypothesis has raised concern for several years55,56,57,58 and is consistent with ample observations reporting the highest ice loss from this region over the past decades26,51,86,87,88,89. We find that, upon transgression of its threshold, the Thwaites/Pine Island basin is committed to the loss of about 70% of its initial (that is, pre-industrial reference) sea-level relevant volume, translating into 0.9 m of long-term sea-level rise in the +1 °C equilibrium simulation. In this case, the ice loss is mainly caused by the onset of MISI90,91, with large-scale unstable retreat of the grounding lines occurring on the retrograde sloping bed portions, eventually slowing down on the prograde sloping bed regions (Fig. 4). The slow-down and subsequent stabilization can be supported by strong glacial isostatic rebound following the large-scale retreat92,93,94.

Colour shadings (red–blue) show the modelled equilibrium ice extent (elevations in metres above sea level, m a.s.l.) for different global warming levels (ΔGMT in °C, starting from the initial, pre-industrial state, shown as blue line) along the transects indicated in the central map panel. Black–grey colour shadings indicate the respective changes in the bedrock topography as it lifts up with reducing ice load (the initial, pre-industrial bedrock topography is shown as a grey line). Observed Antarctic bed topography shown in the central map panel from the Bedmap2 dataset (ref. 95).

For global warming levels between 2–3 °C, the Cook/Ninnis/Mertz basin in East Antarctica (associated with the Wilkes Subglacial Basin) is at risk of potentially losing 40% of its initial ice volume above flotation over time, resulting in a long-term rise in global mean sea level by about 1.2 m. Putting this in relation to the future scenarios (SSPs) commonly used, for example, in the IPCC, such warming levels are reached by the end of this century in all scenarios except for the most optimistic one (SSP1-1.9, ref. 5; note, however, that we are here considering the equilibrium response to fixed climate conditions to assess the long-term stability of the ice basins and only refer to SSPs for context). The underlying mechanism, where a comparably small perturbation at the Cook/Ninnis/Mertz basin outlet glaciers (coastal ‘ice plug’) can trigger long-term, self-amplified retreat has been previously investigated in model simulations61. A second threshold between 6–7 °C in this basin may lead to further loss of about 30% of its initial sea-level relevant volume and an additional contribution to sea-level rise of approximately 0.9 m. Owing to their dynamic connection, parts of the adjacent Victoria Land basin drain into the Southern Ocean through Wilkes Subglacial Basin once global warming levels between 4–5 °C are exceeded, leading to about 0.5 m of additional sea-level rise contribution.

Also in West Antarctica (for example, Abbot/Venable) and along the West Antarctic Peninsula (George VI) we find critical global warming levels between 3–5 °C above pre-industrial levels. Note that such warming levels could be reached by the end of the twenty-first century when following the IPCC emission scenario SSP2-4.5 and all higher scenarios (very likely range, ref. 5).

For global warming levels beyond 6 °C above pre-industrial levels, we find threshold behaviour in almost all regions in East Antarctica (that is, Filchner, Brunt/Riiser-Larsen, Dronning Maud Land, Enderby Land, Amery, West/Denman, Totten/Moscow, Cook/Ninnis/Mertz and Ross East (Byrd)), corresponding to a combined sea-level commitment of more than 26 m. Further critical thresholds are also found for Getz basin in West Antarctica and along the Antarctic Peninsula. In addition, Ronne and Cook/Ninnis/Mertz basins display a second critical threshold between 6–7 °C and Filchner basin a second threshold between 8–9 °C. Note that, in particular, the Getz and the Antarctic Peninsula basins are very small in terms of sea-level potential compared with the other basins and further small ice caps remaining at high altitudes for even higher temperatures also result in a threshold signal, but one that is dynamically less meaningful. Above +10 °C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, we find that Antarctica becomes virtually ice free in the long-term (as already shown in ref. 76; these very high warming levels are here only added for completion).

Risk assessment

Overall, the West Antarctic basins prove to be most vulnerable, large parts of which are at risk of crossing critical thresholds, potentially as low as 1–2 °C of global warming. In fact, about 40% of the present West Antarctic sea-level relevant ice volume (approximately 2.1 metres sea-level equivalent (m SLE)) is committed at this warming level. While several of the critical thresholds for East Antarctic basins are found beyond 6 °C of warming above pre-industrial levels, some significant thresholds occur between 2 °C and 5 °C (Figs. 1–3).

In a combined risk analysis, we assess the critical warming levels together with the respective long-term ice loss caused when crossing said critical warming levels, as well as the (present-day) total sea-level potential for each basin (Fig. 5). Together, the critical warming levels and respective committed sea-level impacts give a valuable first-order indicator for the risk level of a drainage basin, also in light of adaptation planning.

Shown for each Antarctic ice catchment basin is the critical threshold temperature (in °C of global warming above pre-industrial levels), that is, the one-degree interval in which the strongest ice loss occurs, versus the sea-level commitment of the tipped basin, given by the respective equilibrium ice volume loss within the critical temperature interval (metres sea-level equivalent, m SLE). The size of the circles corresponds to the initial ice volume of the basin and the colour to the ice-sheet region. The background shading denotes the associated relative risk level, given as the product of tipping likelihood (distance from threshold temperature) and tipping impact (sea-level commitment from tipping). Coloured bars on the right show the projected global mean surface temperature warming in 2081–2100 relative to the pre-industrial period, given by the median (dark) and 5–95% confidence interval (light), respectively, for five illustrative IPCC emission scenarios5. The observed present-day warming is shown in purple. AP, Antarctic Peninsula; EAIS, East Antarctic Ice Sheet; WAIS, West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Among the basins with the highest risks are Totten/Moscow, Filchner and Ross East (Byrd)—mainly because of their high sea-level commitment—and Thwaites/Pine Island, Ross West (Siple Coast) and Cook/Ninnis/Mertz (Wilkes Subglacial Basin)—mainly because of their respective low critical warming thresholds. Irrespective of this risk classification, however, it is important to keep in mind that substantial sea-level rise can occur even before reaching the critical warming levels identified here and that any sea-level commitment would have severe impacts on coastal ecosystems, infrastructures and populations2,5.

Importantly, while our analysis highlights the potential critical thresholds for each basin, our analysis is not to be misunderstood as sea-level projections, but rather an overarching stability analysis of the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the respective dynamic response of each basin (gradual decline versus tipping dynamics).

Additional feedbacks may be missing from our analysis, including MICI which is not included in our simulations. In future research, further interactions could be considered in a fully coupled Earth system model; however, while some first simulations with Earth system models including interactive ice sheets are emerging, this is not a viable option for the type of stability analysis presented here because of the given computational constraints. For the same reason, a full quantitative uncertainty analysis covering all relevant model parameter choices across all conducted equilibrium experiments is computationally not feasible; we have, however, explored a set of parametric uncertainties (for example, regarding the global-to-regional temperature conversion, surface mass balance, glacial isostatic adjustment and crucial ice-flow processes detailed in the model description), showing that our results are qualitatively robust (Methods; Extended Data Figs. 4–6). A representative model sensitivity ensemble for 2 °C of warming shows that, while parameter variations can affect the timing of ice loss, all simulations eventually approach one of two nearby equilibrium states which emerge as a robust property. For higher warming levels, internal dynamics due to parameter choices play less of a role and ice volume converges with mere differences in the timing of ice-sheet retreat (Extended Data Fig. 6). With additional computational power in the future, the grid resolution could also be refined. However, with the primary aim of identifying critical thresholds between equilibrium states (rather than classifying the transient ice-sheet behaviour in reaching these states), the model grid resolution used here is sufficient to capture the essential feedback dynamics. So, while model grid resolution can be a decisive factor for regional grounding-line dynamics and the precise timing of marine ice loss processes in transient sea-level projections, it is only of secondary importance here.

Overall, our results indicate that the Antarctic Ice Sheet should be viewed not as one (or two) monolithic tipping element(s), but rather as a network of dynamically interacting ice basins, many—but not all—of which show the potential for nonlinear thresholds and tipping behaviour. While our study focuses on the individual drainage basins, it also shows that there needs to be a better understanding of the dynamic clusters, defined as those regions responding coherently to a given temperature. This idea can be generalized to other potential tipping elements in the Earth system, where finding the ‘right’ scale of aggregation is crucial to disentangling the dampening and reinforcing feedbacks. This is especially important in the search of potential early-warning indicators for such large-scale disruptions in the Earth system.

Methods

Ice-sheet model

The model simulations used for the analysis have been carried out using a modified version of the Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM; www.pism.io), v1.0. PISM is an open-source, high-resolution, thermomechanically coupled and polythermal ice flow model77,78,96 which is widely adopted in the scientific community for simulating the evolution of ice sheets and glaciers to constrain projections of future sea-level rise. The model version adopted here is the same as in ref. 76. In simulations over the last two glacial cycles, this model configuration has been proven capable of adequately reproducing the dynamic evolution of Antarctica across its glacial–interglacial history, resulting in simulated present-day ice-sheet configurations reasonably close to observations97.

PISM is a hybrid shallow ice flow model in which ice flow velocities resulting from two stress balance approximations—the shallow ice and shallow shelf approximations—are superimposed over the entire ice-sheet/ice-shelf domain78. This ensures smooth and consistent transitions between the different flow regimes in the interior of the ice sheet, where flow is dominated by vertical shearing, in the ice streams, which are sliding on the bed and in the floating ice shelves, where flow is characterized by fast plug flow.

The simulations are performed using a regular rectangular grid with 16-km horizontal resolution. The vertical grid spacing is quadratic, ranging from 20 m at the ice base to 100 m at the top of the computational domain. While computational feasibility of our long-term simulations puts a strong limit on model grid resolution, PISM uses a subgrid-scale linear interpolation of the basal shear stress between adjacent grounded and floating cells to ensure a free and reversible grounding-line migration, which has been shown to compare well with full-Stokes results throughout a wide range of spatial resolutions—including the resolution used here—qualitatively as well as quantitatively98.

The sliding of the ice sheet over the underlying bedrock is represented by a generalized pseudoplastic power law, which relates bed-parallel shear stress τb and basal sliding velocity ub (ref. 99):

where q = 0.75 is the pseudoplastic sliding exponent and u0 = 100 m yr−1 is a reference velocity. The yield stress τc is determined according to the Mohr–Coulomb criterion based on the till friction angle (an heuristic shear strength parameter for the till material property) and the effective till pressure100. The former is iteratively optimized in the grounded-ice region to minimize the mismatch of modelled and observed ice surface elevations97.

Iceberg calving at the margins of the ice shelves is calculated on the basis of spreading rates (‘eigencalving’, ref. 101), using a proportionality factor of 1017 m s. To ensure numerical stability, we further apply a minimum thickness criterion of 50 m at the calving front102 and remove floating ice in cells which were marked as open ocean during the initial timestep.

The glacial isostatic adjustment of the bedrock and seafloor in response to changing ice loads are modelled using a viscoelastic Earth-deformation model103,104, assuming a spatially uniform upper mantle viscosity of 1021 Pa s (ref. 68) and a standard density of 3,300 kg m−3. As we here only consider equilibrium ice-sheet states, we find only little sensitivity of our results to variations in Earth model parameters. Lower mantle viscosities and lower flexural rigidity (thinner elastic lithosphere), however, can slow transient ice-sheet retreat and shift thresholds to slightly higher (<1 °C) temperatures (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b).

Climatic boundary conditions

At the ice–atmosphere boundary, we compute melt and runoff using a positive degree-day (PDD) scheme with melt coefficients of 3 mm PDD−1 and 8 mm PDD−1 for snow and ice, respectively, and a 5 °C standard deviation to account for diurnal cycles and synoptic variability, applying a sinusoidal yearly temperature cycle105,106. Higher melt factors or lower standard deviation lead to more ice loss for the same temperature forcing or to the same ice loss at lower temperatures. However, for a plausible range of uncertain PDD parameters, the corresponding shift on the temperature scale remains likely within the one-degree resolution of our analysis (Extended Data Fig. 4c).

Annual and summer mean surface air temperatures are thereby parameterized as a function of latitude and surface elevation97, based on multiple regression analysis of ERA-Interim data107. This allows the temperature field to adjust to a changing geometry by deploying a prescribed atmospheric temperature lapse rate Γ of −8.2 K km−1.

Surface accumulation is derived from the Regional Atmospheric Climate Model (RACMO v2.3p2; ref. 108) precipitation output, averaged over the period 1986–2005. Similar to the temperature parameterization, we introduce a climatic correction for precipitation as a modification from PISM v1.0. By scaling the reference precipitation pattern Pref with both the applied surface temperature anomaly and the model ice surface elevation change, this correction ensures that accumulation rates increase under warmer atmospheric conditions as expected from the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship and that geometrical changes have an influence on local precipitation through their effect on local surface temperatures97. The scaling of precipitation with respect to surface temperature change ΔT is exponential34:

with the exponential factor α′ = ln(1.05) ≈ 0.049 K−1 corresponding to a sensitivity α of 5% K−1 precipitation increase per degree of atmospheric warming under the assumption of a linear relationship for lower warming regimes, consistent with ref. 32. The scaling of precipitation with respect to surface elevation change Δh is also exponential97, where the exponential factor α × Γ corresponds to about 51% increase in precipitation per kilometre of elevation lowering and about 34% decrease in precipitation per kilometre of elevation gain:

The range of the sensitivity factor \(\alpha\) found among Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models is 5.46 ± 0.87% K−1 (Table A1 in ref. 34). Assuming an uncertainty of ±1% K−1 around our value of 5% K−1, we find slight shifts in the transient (quasi-static) response for a given temperature forcing (about ±0.5 °C), with thresholds still to be found in the same one-degree temperature intervals (Extended Data Fig. 4d).

Subshelf melting at the ice–ocean boundary underneath the ice shelves is computed using the Potsdam Ice-shelf Cavity Model (PICO; ref. 109). We drive PICO with observed ocean temperature and salinity data from ref. 110, averaged over the period 1975–2012. For the overturning strength coefficient and turbulent heat exchange velocity across the ice–ocean boundary we adopt parameter values of 0.5 Sv (kg m−3)−1 and 10−5 m s−1, respectively. These values are the same as in refs. 76,111 and slightly lower than the values used in refs. 60,109, resulting in a slightly conservative estimate of subshelf melt rates.

Reference ice-sheet state

We start the model simulations from a reference equilibrium ice-sheet state that resembles the pre-industrial Antarctic Ice Sheet geometry as closely as possible. This reference equilibrium state is based on an equilibrium state generated as part of the initial state model intercomparison activity focusing on Antarctica (initMIP-Antarctica; ref. 111) within the framework of the Ice Sheet Model Intercomparison Project for CMIP6 (ISMIP6), the primary CMIP6 activity focusing on the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. It was initialized from Bedmap2 geometry95, with surface accumulation from RACMO v2.3p2 (ref. 108), observed ocean temperature and salinity data from ref. 110 to drive PICO and run over 100 kyr (for more details, see Appendix B12 of ref. 111). Using our modified PISM version76, we extended this initMIP equilibrium simulation for another 150 kyr under the same climatic boundary conditions. In comparison to the model configuration used in ref. 111, in addition to some minor model updates and fixes, the modified model version accounts for glacial isostatic adjustment of the bedrock and adopts parameterizations of surface air temperature and precipitation that dynamically account for changes in ice-sheet geometry, with surface melt rates being now computed by a PDD scheme (see above and ref. 76 for details). A comparison of the model reference equilibrium state at the end of the 250-kyr spin-up with observational data of ice geometry95 and velocities112 is shown in Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

In light of recent observations, which show that the Antarctic Ice Sheet has undergone notable changes in recent decades due to anthropogenic climate forcing, we note that the ice sheet is probably no longer in equilibrium27,83. However, as observational data—which constrain the geometric and climatic boundary conditions in our model simulations—are only available from the second half of the twentieth century, we interpret the pre-industrial ice-sheet configuration as the closest analogue to this reference equilibrium state and therefore take temperature anomalies in all experiments presented here with respect to pre-industrial (~1850–1900) levels.

Warming scenarios

Starting from the reference equilibrium ice-sheet state, we deploy generic warming scenarios to assess the long-term stability behaviour and critical thresholds of the ice sheet in response to changing global temperatures. In these scenarios, a spatially uniform global mean temperature anomaly that is gradually increasing over time is applied to the boundary climate in the model until near-complete deglaciation of the entire ice sheet is achieved. The rate of change of the temperature increase of 0.0001 °C yr−1 is thereby slower than the typical response timescale of the ice sheet to ensure that the system can follow the change while remaining close to equilibrium at all times (‘quasi-static’ change). These simulations are then extended at each full degree under fixed global mean temperature levels until a real steady state is reached, that is, volume changes in response to the forcing have become negligible. Equilibrium simulations are run for at least 20 kyr and in higher warming regimes (above 6 °C of warming) for 50 kyr to account for the higher sensitivities, that is, the amount of ice loss per degree of warming.

Global mean temperature anomalies are translated into Antarctic regional (south of 66° S) atmospheric and intermediate-depth (500–2,500 m) oceanic temperature changes using constant scaling factors of 1.8 and 0.7, respectively, which are uniformly applied across the entire model domain and are derived from long-term, near-equilibrium simulations with the coupled climate model ECHAM5/MPIOM following an abrupt fourfold increase in CO2 (ref. 113). Despite different equilibrium climate sensitivities, we estimate similar scaling factors from similar long-term experiments with other climate models (MPIESM1.1, CESM1.0.4 and GISS-E2-R) participating in LongRunMIP114, with scaling ratios with respect to global mean temperature ranging between 1.8 to 2.3 and 0.7 to 1.0 for Antarctic regional atmospheric and oceanic temperature changes, respectively. Importantly, the ratio of Antarctic regional oceanic and atmospheric temperatures remains consistently between 0.4 and 0.5 across all analysed models. Sensitivity simulations based on the (transient) quasi-static experiment show that our results remain overall robust with respect to changes in the scaling factors within these ranges (Extended Data Fig. 5). Note that using regional scaling factors could also affect the timing of crossing respective thresholds, but the critical warming levels relevant for the equilibrium response are likely to be consistent with the ones derived here using the uniform scaling factors.

Basin analysis

The catchment basin boundaries used in the analysis are derived from the Making Earth System Data Records for Use in Research Environments (MEaSUREs) Antarctic Boundaries for IPY 2007–2009 from Satellite Radar (v2) dataset84 (Extended Data Table 1), using the most recent refinements developed for the latest Ice Sheet Mass Balance Intercomparison Exercise (IMBIE-3). The basin boundaries are defined on the basis of historical nomenclature plus modern digital elevation model95 and ice velocity data112 and adjusted to match the drainage boundaries of the major ice shelves.

Sea-level relevant ice volume

In our analysis we derive volume changes of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from changes in the ice thickness and bed elevation and convert these changes into units of metres sea-level equivalent (m SLE). This conversion assumes that only the grounded ice above flotation contributes to sea-level changes. For better comparison with previous studies (for example, refs. 38,115), we here follow the definition of ‘volume above flotation’ (Vaf), applied to the projected domain of the individual Antarctic ice basins. Our calculation is in line with the definition of Vaf given in ref. 116 (corrected equation 1, using an ocean area of 3.61 × 1014 m2). However, we have not used the additional suggested corrections by refs. 116,117, that intend to account for the changing density of the melted ice in the ocean, or for the effect of glacial isostatic adjustment on the sea-level contribution (often associated with the ‘water expulsion effect’). While the implied corrections can in places be substantial, the way of converting ice volume changes does not change the qualitative behaviour and threshold temperatures in our analysis.

Data availability

All data used for this assessment are publicly available. Antarctic surface mass balance data from RACMO2.3p2 can be downloaded from https://www.projects.science.uu.nl/iceclimate/publications/data/2018/index.php#vwessem2018_tc. Antarctic bedrock topography and ice thickness data are from the Bedmap2 compilation, available at https://secure.antarctica.ac.uk/data/bedmap2/. MEaSUREs Antarctic ice surface velocities are available from the National Snow and Ice Data Center at https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0484/. The MEaSUREs Antarctic Boundaries dataset (IMBIE basins) is available from the National Snow and Ice Data Center at https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0709/. The ocean temperature and salinity dataset can be retrieved at https://www.geomar.de/en/staff/fb1/po/sschmidtko/southern-ocean/. The PISM model output data generated and analysed in this study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17466786 (ref. 118).

Code availability

PISM is freely available as open-source code under the GPL license from www.pism.io. The code version used in this study is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3956431 (ref. 119). PISM input data are preprocessed using https://github.com/pism/pism-ais with original data citations. The Python scripts used to analyse the data and create the figures are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Morlighem, M. et al. Deep glacial troughs and stabilizing ridges unveiled beneath the margins of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nat. Geosci. 13, 132–137 (2020).

IPCC. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Clark, P. U. et al. Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 360–369 (2016).

Strauss, B. H., Kulp, S. A., Rasmussen, D. J. & Levermann, A. Unprecedented threats to cities from multi-century sea level rise. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114015 (2021).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

Li, Q., England, M. H., Hogg, A. M., Rintoul, S. R. & Morrison, A. K. Abyssal ocean overturning slowdown and warming driven by Antarctic meltwater. Nature 615, 841–847 (2023).

Fogwill, C. J., Phipps, S. J., Turney, C. S. M. & Golledge, N. R. Sensitivity of the Southern Ocean to enhanced regional Antarctic ice sheet meltwater input. Earth’s Future 3, 317–329 (2015).

Purkey, S. G. & Johnson, G. C. Warming of global abyssal and deep southern ocean waters between the 1990s and 2000s: contributions to global heat and sea level rise budgets. J. Clim. 23, 6336–6351 (2010).

Purkey, S. G. & Johnson, G. C. Antarctic bottom water warming and freshening: contributions to sea level rise, ocean freshwater budgets, and global heat gain. J. Clim. 26, 6105–6122 (2013).

Naish, T. et al. Obliquity-paced Pliocene West Antarctic ice sheet oscillations. Nature 458, 322–328 (2009).

DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature 531, 591–597 (2016).

Turney et al. Early Last Interglacial ocean warming drove substantial ice mass loss from Antarctica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 3996–4006 (2020).

Weber, M. E., Golledge, N. R., Fogwill, C. J., Turney, C. S. M. & Thomas, Z. A. Decadal-scale onset and termination of Antarctic ice-mass loss during the last deglaciation. Nat. Commun. 12, 6683 (2021).

Dutton, A. et al. Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods. Science 349, aaa4019 (2015).

Grant, G. R. et al. The amplitude and origin of sea-level variability during the Pliocene epoch. Nature 574, 237–241 (2019).

Golledge, N. R. et al. Retreat of the Antarctic Ice Sheet during the last interglaciation and implications for future change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094513 (2021).

Clark, P. U. et al. Oceanic forcing of penultimate deglacial and last interglacial sea-level rise. Nature 577, 660–664 (2020).

Wilson et al. Ice loss from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet during late Pleistocene interglacials. Nature 561, 383–386 (2018).

Blackburn, T. et al. Ice retreat in Wilkes Basin of East Antarctica during a warm interglacial. Nature 583, 554–559 (2020).

Iizuka, M. et al. Multiple episodes of ice loss from the Wilkes Subglacial Basin during the Last Interglacial. Nat. Commun. 14, 2129 (2023).

Golledge, N. R. et al. Antarctic contribution to meltwater pulse 1A from reduced Southern Ocean overturning. Nat. Commun. 5, 5107 (2014).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1786–1793 (2008).

McKay, D. I. A. et al. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Pattyn, F. et al. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets under 1.5 °C global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1053–1061 (2018).

Lenton, T. M. et al. (eds) The Global Tipping Points Report 2023 (Univ. of Exeter, 2023).

Rignot, E. et al. Four decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet mass balance from 1979–2017. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1095–1103 (2019).

Otosaka et al. Mass balance of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets from 1992 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1597–1616 (2023).

Turner, J. et al. Atmosphere–ocean–ice interactions in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica. Rev. Geophys. 55, 235–276 (2017).

Joughin, I., Shapero, D., Smith, B., Dutrieux, P. & Barham, M. Ice-shelf retreat drives recent Pine Island Glacier speedup. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg3080 (2021).

Rydt, J. D., Reese, R., Paolo, F. S. & Gudmundsson, G. H. Drivers of Pine Island Glacier speed-up between 1996 and 2016. Cryosphere 15, 113–132 (2021).

Shen, Q. et al. Recent high-resolution Antarctic ice velocity maps reveal increased mass loss in Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 8, 4477 (2018).

Frieler, K. et al. Consistent evidence of increasing Antarctic accumulation with warming. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 348–352 (2015).

Palerme, C. et al. Evaluation of current and projected Antarctic precipitation in CMIP5 models. Clim. Dynam. 48, 225–239 (2017).

Nicola, L., Notz, D. & Winkelmann, R. Revisiting temperature sensitivity: how does Antarctic precipitation change with temperature? Cryosphere 17, 2563–2583 (2023).

Medley, B. & Thomas, E. R. Increased snowfall over the Antarctic Ice Sheet mitigated twentieth-century sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 34–39 (2019).

Rodehacke, C. B., Pfeiffer, M., Semmler, T., Gurses, Ö & Kleiner, T. Future sea level contribution from Antarctica inferred from CMIP5 model forcing and its dependence on precipitation ansatz. Earth Syst. Dynam. 11, 1153–1194 (2020).

Coulon, V. et al. Disentangling the drivers of future Antarctic ice loss with a historically calibrated ice-sheet model. Cryosphere 18, 653–681 (2023).

Seroussi, H. et al. Evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet over the next three centuries from an ISMIP6 model ensemble. Earth’s Future 12, e2024EF004561 (2024).

Weertman, J. Stability of ice-age ice sheets. J. Geophys. Res. 66, 3783–3792 (1961).

Levermann, A. & Winkelmann, R. A simple equation for the melt elevation feedback of ice sheets. Cryosphere 10, 1799–1807 (2016).

Jakobs, C. L., Reijmer, C. H., van den Broeke, M. R., van de Berg, W. J. & van Wessem, J. M. Spatial variability of the snowmelt-albedo feedback in Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surface 126, e2020JF005696 (2021).

Weertman, J. Stability of the junction of an ice sheet and an ice shelf. J. Glaciol. 13, 3–11 (1974).

Schoof, C. Ice sheet grounding line dynamics: steady states, stability, and hysteresis. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jf000664 (2007).

Bassis, J. N. & Walker, C. C. Upper and lower limits on the stability of calving glaciers from the yield strength envelope of ice. Proc. R. Soc. A 468, 913–931 (2012).

Pollard, D., DeConto, R. M. & Alley, R. B. Potential Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat driven by hydrofracturing and ice cliff failure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 412, 112–121 (2015).

Bronselaer, B. et al. Change in future climate due to Antarctic meltwater. Nature 564, 53–58 (2018).

Golledge, N. R. et al. Global environmental consequences of twenty-first-century ice-sheet melt. Nature 566, 65–72 (2019).

Fyke, J., Sergienko, O., Löfverström, M., Price, S. & Lenaerts, J. T. M. An overview of interactions and feedbacks between ice sheets and the earth system. Rev. Geophys. 56, 361–408 (2018).

Garbe, J., Zeitz, M., Krebs-Kanzow, U. & Winkelmann, R. The evolution of future Antarctic surface melt using PISM-dEBM-simple. Cryosphere 17, 4571–4599 (2023).

Pritchard, H. D. et al. Antarctic ice-sheet loss driven by basal melting of ice shelves. Nature 484, 502–505 (2012).

Depoorter, M. A. et al. Calving fluxes and basal melt rates of Antarctic ice shelves. Nature 502, 89–92 (2013).

Jenkins, A. et al. West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat in the Amundsen Sea driven by decadal oceanic variability. Nat. Geosci. 11, 733–738 (2018).

Holland, P. R., Bracegirdle, T. J., Dutrieux, P., Jenkins, A. & Steig, E. J. West Antarctic ice loss influenced by internal climate variability and anthropogenic forcing. Nat. Geosci. 12, 718–724 (2019).

Greene, C. A., Gardner, A. S., Schlegel, N.-J. & Fraser, A. D. Antarctic calving loss rivals ice-shelf thinning. Nature 609, 948–953 (2022).

Joughin, I., Smith, B. E. & Medley, B. Marine Ice Sheet collapse potentially under way for the Thwaites Glacier Basin, West Antarctica. Science 344, 735–738 (2014).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H. & Scheuchl, B. Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3502–3509 (2014).

Favier, L. et al. Retreat of Pine Island Glacier controlled by marine ice-sheet instability. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 117–121 (2014).

Mouginot, J., Rignot, E. & Scheuchl, B. Sustained increase in ice discharge from the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica, from 1973 to 2013. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1576–1584 (2014).

Hill, E. A. et al. The stability of present-day Antarctic grounding lines—Part 1: No indication of marine ice sheet instability in the current geometry. Cryosphere 17, 3739–3759 (2023).

Reese, R. et al. The stability of present-day Antarctic grounding lines—Part 2: Onset of irreversible retreat of Amundsen Sea glaciers under current climate on centennial timescales cannot be excluded. Cryosphere 17, 3761–3783 (2023).

Mengel, M. & Levermann, A. Ice plug prevents irreversible discharge from East Antarctica. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 451–455 (2014).

Golledge, N. R., Levy, R. H., McKay, R. M. & Naish, T. R. East Antarctic ice sheet most vulnerable to Weddell Sea warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 2343–2351 (2017).

DeConto, R. M. et al. The Paris Climate Agreement and future sea-level rise from Antarctica. Nature 593, 83–89 (2021).

Edwards, T. L. et al. Revisiting Antarctic ice loss due to marine ice-cliff instability. Nature 566, 58–64 (2019).

Morlighem, M. et al. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet may not be vulnerable to marine ice cliff instability during the 21st century. Sci. Adv. 10, eado7794 (2024).

Schlemm, T., Feldmann, J., Winkelmann, R. & Levermann, A. Stabilizing effect of mélange buttressing on the marine ice-cliff instability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Cryosphere 16, 1979–1996 (2022).

Colleoni, F. et al. Spatio-temporal variability of processes across Antarctic ice-bed–ocean interfaces. Nat. Commun. 9, 2289 (2018).

Whitehouse, P. L., Gomez, N., King, M. A. & Wiens, D. A. Solid Earth change and the evolution of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Nat. Commun. 10, 503 (2019).

Kriegler, E., Hall, J. W., Held, H., Dawson, R. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Imprecise probability assessment of tipping points in the climate system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5041–5046 (2009).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. Nature 575, 592–595 (2019).

Wunderling, N. et al. Climate tipping point interactions and cascades: a review. Earth Syst. Dynam. 15, 41–74 (2024).

Bamber, J. L., Oppenheimer, M., Kopp, R. E., Aspinall, W. P. & Cooke, R. M. Ice sheet contributions to future sea-level rise from structured expert judgment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 11195–11200 (2019).

Levermann, A. et al. The multimillennial sea-level commitment of global warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13745–13750 (2013).

Golledge, N. R. et al. The multi-millennial Antarctic commitment to future sea-level rise. Nature 526, 421–425 (2015).

Klose, A. K., Coulon, V., Pattyn, F. & Winkelmann, R. The long-term sea-level commitment from Antarctica. Cryosphere 18, 4463–4492 (2024).

Garbe, J., Albrecht, T., Levermann, A., Donges, J. F. & Winkelmann, R. The hysteresis of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Nature 585, 538–544 (2020).

Bueler, E. & Brown, J. Shallow shelf approximation as a ‘sliding law’ in a thermomechanically coupled ice sheet model. J. Geophys. Res. 114, F03008 (2009).

Winkelmann, R. et al. The Potsdam Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM-PIK)—Part 1: Model description. Cryosphere 5, 715–726 (2011).

Rahmstorf, S. & England, M. H. Influence of Southern hemisphere winds on North Atlantic deep water flow. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 27, 2040–2054 (1997).

Rahmstorf, S. et al. Thermohaline circulation hysteresis: a model intercomparison. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gl023655 (2005).

Van Westen, R. M., Kliphuis, M. & Dijkstra, H. A. Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk1189 (2024).

Robinson, A., Calov, R. & Ganopolski, A. Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 429–432 (2012).

Hanna, E. et al. Short- and long-term variability of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 193–210 (2024).

Mouginot, J., Scheuchl, B. & Rignot, E. MEaSUREs Antarctic Boundaries for IPY 2007-2009 from Satellite Radar, Version 2. Basins as prepared for the Ice sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (IMBIE) 2016. National Snow and Ice Data Center (2017); https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0709/versions/2

Akker et al. Present-day mass loss rates are a precursor for West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse. Cryosphere 19, 283–301 (2025).

Paolo, F. S., Fricker, H. A. & Padman, L. Volume loss from Antarctic ice shelves is accelerating. Science 348, 327–331 (2015).

Gardner, A. S. et al. Increased West Antarctic and unchanged East Antarctic ice discharge over the last 7 years. Cryosphere 12, 521–547 (2018).

Shepherd, A. et al. Trends in Antarctic Ice Sheet elevation and mass. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 8174–8183 (2019).

Smith, B. et al. Pervasive ice sheet mass loss reflects competing ocean and atmosphere processes. Science 368, 1239–1242 (2020).

Rosier, S. H. R. et al. The tipping points and early warning indicators for Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica. Cryosphere 15, 1501–1516 (2021).

Sutter, J., Gierz, P., Grosfeld, K., Thoma, M. & Lohmann, G. Ocean temperature thresholds for Last Interglacial West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2675–2682 (2016).

Gomez, N., Pollard, D. & Holland, D. Sea-level feedback lowers projections of future Antarctic Ice-Sheet mass loss. Nat. Commun. 6, 8798 (2015).

Konrad, H., Sasgen, I., Pollard, D. & Klemann, V. Potential of the solid-Earth response for limiting long-term West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat in a warming climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 432, 254–264 (2015).

Larour, E. et al. Slowdown in Antarctic mass loss from solid Earth and sea-level feedbacks. Science 364, eaav7908 (2019).

Fretwell, P. et al. Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica. Cryosphere 7, 375–393 (2013).

The PISM Authors. PISM, a Parallel Ice Sheet Model: User’s Manual (version 1.0) (2017); https://www.pism.io

Albrecht, T., Winkelmann, R. & Levermann, A. Glacial-cycle simulations of the Antarctic Ice Sheet with the Parallel Ice Sheet Model (PISM)—Part 1: Boundary conditions and climatic forcing. Cryosphere 14, 599–632 (2020).

Feldmann, J., Albrecht, T., Khroulev, C., Pattyn, F. & Levermann, A. Resolution-dependent performance of grounding line motion in a shallow model compared with a full-Stokes model according to the MISMIP3d intercomparison. J. Glaciol. 60, 353–360 (2014).

Schoof, C. & Hindmarsh, R. C. A. Thin-film flows with wall slip: an asymptotic analysis of higher order glacier flow models. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 63, 73–114 (2010).

Bueler, E. & van Pelt, W. Mass-conserving subglacial hydrology in the Parallel Ice Sheet Model version 0.6. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 1613–1635 (2015).

Levermann, A. et al. Kinematic first-order calving law implies potential for abrupt ice-shelf retreat. Cryosphere 6, 273–286 (2012).

Albrecht, T., Martin, M., Haseloff, M., Winkelmann, R. & Levermann, A. Parameterization for subgrid-scale motion of ice-shelf calving fronts. Cryosphere 5, 35–44 (2011).

Lingle, C. S. & Clark, J. A. A numerical model of interactions between a marine ice sheet and the solid earth: application to a West Antarctic ice stream. J. Geophys. Res. 90, 1100–1114 (1985).

Bueler, E., Lingle, C. S. & Brown, J. Fast computation of a viscoelastic deformable Earth model for ice-sheet simulations. Ann. Glaciol. 46, 97–105 (2007).

Reeh, N. Parameterization of melt rate and surface temperature in the Greenland Ice Sheet. Polarforschung 59, 113–128 (1991).

Calov, R. & Greve, R. A semi-analytical solution for the positive degree-day model with stochastic temperature variations. J. Glaciol. 51, 173–175 (2005).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Van Wessem et al. Modelling the climate and surface mass balance of polar ice sheets using RACMO2—Part 2: Antarctica (1979–2016). Cryosphere 12, 1479–1498 (2018).

Reese, R., Albrecht, T., Mengel, M., Asay-Davis, X. & Winkelmann, R. Antarctic sub-shelf melt rates via PICO. Cryosphere 12, 1969–1985 (2018).

Schmidtko, S., Heywood, K. J., Thompson, A. F. & Aoki, S. Multidecadal warming of Antarctic waters. Science 346, 1227–1231 (2014).

Seroussi, H. et al. initMIP-Antarctica: an ice sheet model initialization experiment of ISMIP6. Cryosphere 13, 1441–1471 (2019).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J. & Scheuchl, B. Ice flow of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 333, 1427–1430 (2011).

Li, C., von Storch, J.-S. & Marotzke, J. Deep-ocean heat uptake and equilibrium climate response. Clim. Dynam. 40, 1071–1086 (2013).

Rugenstein, M. et al. LongRunMIP—motivation and design for a large collection of millennial-length AO-GCM simulations LongRunMIP—motivation and design for a large collection of millennial-length AO-GCM simulations. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 2551–2570 (2019).

Seroussi, H. et al. ISMIP6 Antarctica: a multi-model ensemble of the Antarctic ice sheet evolution over the 21st century. Cryosphere 14, 3033–3070 (2020).

Goelzer, H., Coulon, V., Pattyn, F., de Boer, B. & van de Wal, R. Brief communication: On calculating the sea-level contribution in marine ice-sheet models. Cryosphere 14, 833–840 (2020).

Adhikari, S., Ivins, E. R., Larour, E., Caron, L. & Seroussi, H. A kinematic formalism for tracking ice–ocean mass exchange on the Earth’s surface and estimating sea-level change. Cryosphere 14, 2819–2833 (2020).

Garbe, J., Albrecht, T., Winkelmann, R. & Donges, J. F. PISM model output data from Winkelmann et al. (Nature Climate Change, 2026) publication. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17466786 (2025).

Garbe, J. & other PISM authors. PISM version as used in Garbe et al. (Nature, 2020) publication (v1.0-hysteresis-antarctica). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3956431 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreements no. 820575 (TiPACCs) (R.W. and J.G.) and no. 869304 (PROTECT) (R.W.). This research was further supported by Ocean Cryosphere Exchanges in Antarctica: Impacts on Climate and the Earth system, OCEAN ICE, which is funded by the European Union, Horizon Europe Funding Programme for research and innovation under grant agreement no. 101060452, https://doi.org/10.3030/101060452 (R.W. and T.A.). This is OCEAN ICE contribution no. 20. This is ClimTip contribution no. 76; the ClimTip project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101137601 (R.W. and J.F.D.). T.A. and R.W. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in the framework of the priority programme ‘Antarctic Research with comparative investigations in Arctic ice areas’ (grant no. WI4556/4-1) and in the framework of the PalMod project (FKZ 01LP1925D and FKZ 01LP2305B), supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as a Research for Sustainability initiative (FONA). J.F.D. is grateful for financial support by the European Research Council (advanced grant project ‘Earth Resilience in the Anthropocene’, grant no. ERC-2016-ADG-743080) and the BMBF (project ‘PIK_Change’, grant no. 01LS2001A). Development of PISM is supported by NASA (grant nos. 20-CRYO2020-0052 and 80NSSC22K0274) and NSF (grant no. OAC-2118285). We further acknowledge the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the BMBF and the Land Brandenburg for supporting this project by providing resources on the high-performance computer system at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Potsdam-Institut für Klimafolgenforschung (PIK) e.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.W. conceived the study. R.W., with J.G., J.F.D. and T.A., designed the research. J.G. performed the experiments and analysis and produced the figures. All authors contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results. R.W. led the writing of the paper with contributions from J.G., J.F.D. and T.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Johannes Sutter and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of modelled and observed ice geometry.

a, Observed Antarctic ice surface elevation from the Bedmap2 dataset (ref. 95), regridded to 16 km. Grounding lines are shown in white. b, Modelled ice surface elevation of the reference equilibrium state serving as initial configuration for the experiments. Grounding lines are shown in white. c, Difference between modelled and observed ice surface elevations. d, Scatter plot comparing modelled and observed ice thickness for each model grid cell. The grey line illustrates where modelled ice thickness would perfectly match the observations. RMSE, root-mean-square error.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Comparison of modelled and observed ice velocities.

a, Observed Antarctic ice surface velocities derived from multiple satellite interferometric synthetic-aperture radar systems as part of the MEaSUREs dataset (ref. 112), regridded to 16 km. b, Modelled ice surface velocities of the reference equilibrium state serving as initial configuration for the experiments. c, Difference between modelled and observed ice surface velocity. d, Scatter plot comparing modelled and observed ice surface velocities for each model grid cell. The grey line illustrates where modelled ice surface velocities would perfectly match the observations. RMSE, root-mean-square error.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Equilibrium ice-sheet geometries under different warming levels.

Equilibrium ice-sheet surface elevations (in metres) for different warming levels (global mean temperature anomaly above pre-industrial level). Ice surface-height contours are delineated at 1,000-m intervals. Grounding-line locations of the pre-industrial reference equilibrium state are shown in red; ice shelves are highlighted in light blue. Blue shadings illustrate the bedrock depth in metres below the present-day sea level; brown shadings illustrate the bedrock elevation in metres above the present-day sea level (m a.s.l.) after full glacial isostatic rebound. EAIS, East Antarctic Ice Sheet; FRIS, Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf; IS, ice shelf; WAIS, West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Model sensitivity to parameter variations (based on the quasi-static experiment).

Sea-level relevant ice volume (in metres sea-level equivalent, m SLE) as a function of global mean temperature (GMT) change, based on the quasi-static experiment (using a warming rate of 0.0001 °C yr−1 above pre-industrial levels), showing the model sensitivity to various model parameters. The thick dark blue line shows the reference simulation. a, Sensitivity to variations in upper mantle viscosity η in the Earth-deformation model. b, Sensitivity to including the elastic component of the Earth-deformation model (elastic vs. non-elastic response). c, Sensitivity to parameters of the positive degree-day (PDD) surface melt scheme, varying the melt coefficients for snow fs and ice fi, and standard deviation of the PDD distribution σ. d, Sensitivity to the precipitation scaling factor α that relates precipitation changes to atmospheric temperature and ice surface elevation changes, respectively. In all panels, the light blue bars (with respect to the right-hand axis) indicate, for each full degree of warming, the temperature difference – that is, the ‘shift’ in GMT – relative to the reference simulation yielding the same ice volume for the respective parameter variation (in °C).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Global to regional Antarctic temperature conversion (based on the quasi-static experiment).

Sea-level relevant ice volume (in metres sea-level equivalent, m SLE) as a function of Antarctic mean surface temperature change, based on the quasi-static experiment (using a warming rate of 0.0001 °C yr−1 above pre-industrial levels), showing the model sensitivity to variations in the scaling factors used to convert global temperature changes into Antarctic regional surface air (θatm) and ocean (θocn) temperature changes, derived from long-term global climate model output (ref. 114). The thick dark blue line represents the reference simulation. The inset shows a zoom into the lower temperature regime, with ice volumes plotted as a function of circum-Antarctic ocean temperature change, the primary driver of ice loss at low warming levels.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Model sensitivity to parameter variations (based on equilibrium experiments).

Evolution of sea-level relevant ice volume (in metres sea-level equivalent, m SLE) in two representative sets of equilibrium simulations at 2 °C and 7 °C of global mean warming above pre-industrial levels, showing the model sensitivity to variations in critical ice-dynamical model parameters (flow enhancement factor for the SSA velocities ESSA; exponent in the ‘pseudo-plastic’ sliding law q; decay rate of the subglacial meltwater in the till layer Ċ) in two different representative temperature and stability regimes. The thick dark blue line shows the reference simulations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Winkelmann, R., Garbe, J., Donges, J.F. et al. Mapping tipping risks from Antarctic ice basins under global warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02554-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02554-0