Abstract

Online platforms are rife with racial discrimination1, but current interventions focus on employers2,3 rather than customers. We propose a customer-facing solution: changing to a two-point rating scale (dichotomization). Compared with the ubiquitous five-star scale, we argue that dichotomization reduces modern racial discrimination by focusing evaluators on the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ performance, thereby reducing how personal beliefs shape customer assessments. Study 1 is a quasi-natural experiment on a home-services labour platform (n = 69,971) in which the company exogenously changed from a five-star scale to a dichotomous scale (thumbs up or thumbs down). Dichotomization eliminated customers’ racial discrimination whereby non-white workers received lower ratings and earned 91 cents for each US dollar paid to white workers for the same work. A pre-registered experiment (study 2, n = 652) found that the equalizing effect of dichotomization is most prevalent among evaluators holding modern racist beliefs. Further experiments (study 3, n = 1,435; study 4, n = 528) provide evidence of the proposed mechanism, and eight supplementary studies support measurement and design choices. Our research offers a promising intervention for reducing customers’ subtle racial discrimination in a large section of the economy and contributes to the interdisciplinary literature on evaluation processes and racial inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Evaluation processes, whereby an individual rates the quality of an offering (such as a person, goods or a service), are common in professional and social life, particularly in the quickly growing online-platform labour market. These evaluations are also consequential4,5,6,7; even marginal differences in customers’ ratings can have a considerable impact on workers. Importantly, investigators have consistently shown that racial disparities surface in evaluations, despite equal quality and performance1,6,8,9,10,11,12. Evaluators may associate racial minorities with negative stereotypes13, have implicit biases about minorities14,15,16, or hold racial minorities to a higher standard of evaluation17,18,19, each of which may lead to lower performance ratings for racial minority workers compared with similar white workers.

Current interventions to mitigate race-based disparities in organizational contexts, however, focus primarily on improving policies and strategies in selection and recruitment, as well as on implicit bias training2,3. It is not feasible to implement such approaches to reduce discrimination by customers in online labour markets, however, and the effectiveness of some common strategies is questionable3,20. Furthermore, other potential interventions, such as removing a worker’s identifying information, are less suitable for labour markets in which the customer interacts with the worker in person, which requires them to know the worker’s identity for safety purposes.

We examine a potential structural solution21,22,23 to reduce racial discrimination in customer evaluations of workers, specifically, switching from the widely used five-star rating scale to a dichotomous (for example, thumbs up or thumbs down) scale. Reducing the number of scale points seems promising; research has shown that shifting from a ten-point to a six-point rating scale lessened the extent of student discrimination against female professors in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Researchers proposed that the change was effective because the number 10 evokes the idea of ‘intellectual brilliance’, a key notion in academia, which in turn activated gender stereotypes about performance, whereas the number 6 does not elicit these associations24. Building on this scale-intervention methodology and sociological research about the role of evaluation structures on observed bias7,19,24,25, we propose that dichotomization of the scale used, and not simply reducing the number of scale points, will reduce racial discrimination in customer evaluations of workers. We reason that this is because dichotomous scales discourage the expression of modern racist beliefs that manifest as subtle discrimination.

Psychologists have shown that contemporary forms of racism are often less overt or outwardly hostile than historical forms26,27,28,29. Therefore, contemporary forms of racism increasingly manifest as subtle discrimination30, described as “negative or ambivalent demeanor and/or treatment enacted toward social minorities on the basis of their minority status membership that are not necessarily conscious and likely convey ambiguous intent”31 and “difficult to detect, low in intensity, and often unintentional but are nevertheless deleterious”31. Such subtle discrimination allows individuals to maintain a self-perception of being non-prejudiced while simultaneously demonstrating racial bias26,32,33,34,35.

We propose that multipoint scales, such as five-point rating scales, create conditions conducive to the emergence of subtle racial discrimination. Contemporary theories of prejudice posit that most individuals are not overtly racist and do not want to see themselves as such26,36. Therefore, we contend that evaluators holding modern racist beliefs will be inclined to slightly downgrade their evaluations of racial minorities (relative to white people) when using a five-point scale. For instance, a customer holding modern racist beliefs might opt to rate a racial minority individual who performs well with a four instead of a five. Such behaviour would not challenge this customer’s self-view of being non-prejudiced, because a four-star rating can be rationalized as a good rating.

Research has shown that the design of measurement instruments can implicitly suggest how an evaluator ought to make an assessment, influencing the level of differentiation they perceive to be appropriate23,24. Consequently, we argue that a dichotomous scale limits the subtle discrimination that occurs in multipoint scales, particularly among those holding modern racist beliefs. This is because dichotomization sends a signal to evaluators to focus solely on the distinction between good and bad performance, rather than including one’s personal beliefs as part of a more fine-grained assessment. As a result, it is less likely that individuals holding modern racist beliefs would give an unambiguously negative score (for example, thumbs down) to a racial minority who performed well, as this would challenge their self-perception of being non-prejudiced. To summarize, contemporary racial biases are more likely to manifest as subtle discriminatory behaviour on a five-point scale as opposed to a dichotomous scale.

Notably, our argument does not exclude the possibility that this intervention could be relevant to other groups frequently subjected to contemporary discrimination by evaluators, such as women10,17,19,37 or individuals with disabilities38, or that other potential mechanisms exist. However, across four main studies, we focused on racial discrimination by customers because of the predominance of racial discrimination in the online labour market demonstrated in previous research1,10,11,12,39. We return to the generalizability of our theory in the discussion.

In study 1, we use a quasi-natural experiment on a home-services labour platform to examine how an exogenous change to the rating system, from a five-star to a thumbs up/down scale, affected racial inequality in customers’ evaluations of workers and in workers’ income. In study 2, we present a pre-registered experiment in which we randomized a demographically and location-balanced online survey pool to rate, using either a five or a two-point scale, an organization with identical, highly performing white versus racial-minority workers. We also examine whether the proposed effect is stronger among participants holding modern racist beliefs. In study 3, we conduct a pre-registered experiment to examine our proposed mechanism: evaluators’ perceptions that the scale allows for inclusion of their personal beliefs and preferences in their evaluations. Finally, in study 4, we recruit individuals with modern racist beliefs and then experimentally manipulate the process of making a dichotomous evaluation, independently from the reduction of scale points. Supplemental analyses and experiments (Supplementary Information sections 1.2, 2.4, 4, 5, 9 and 10) address the robustness of the results, discuss potential alternative explanations, and test assumptions behind the empirical and theoretical approach. We end with a discussion of the broader impact that dichotomization has for customers, workers and platforms.

Dichotomization mitigates race inequality

Our first study examined an exogenous change to the rating scale used by ServicesConnect (SC, which is a pseudonym). SC operates an online platform that connects customers to small-business owners (workers) for various home service jobs, such as appliance repair, and electrical and maintenance services, in the United States and Canada (see Study 1 context for more details).

SC abruptly changed its customer evaluation system from a five-star rating scale to a thumbs up/down scale. Figure 1a shows the e-mail customers received when matched to a worker; Fig. 1b shows the rating e-mail customers received before the rating-scale change (up to five stars); and Fig. 1c shows the rating e-mail after the change (thumbs up/down). The change was not announced or explained to customers and was not motivated by events on the platform; instead, the leadership made the change in the hope of simplifying the evaluation process. Our data include 100,759 completed jobs and 69,971 customer ratings, with 55,713 occurring before the rating-scale change (on the five-star scale) and 14,258 occurring after the rating-scale change (thumbs up/down). There were only 20 female workers, so they were not included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics of study 1 are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

a, An artistic rendering of the e-mail SC customers received informing them of the worker who is matched to complete their job. In the thumbs up/down scale e-mail, the average star rating is replaced with the percentage of thumbs up ratings that the worker has received. b, The e-mail customers received after the job was completed asking them to leave a rating when the five-star scale was used. c, The e-mail customers received after the job was completed asking them to leave a rating when the thumbs up/down scale was used. Credit: face adapted by Glenn Dellon at dellondesign.com from chicagofaces.org.

All the results report two-tailed tests, and regression results are from ordinary least-squares regressions with and without controls (see Study 1 measures for details). We first examined whether ratings differed for workers likely to have been perceived as racial minorities (non-white) versus white using the original five-star scale (see Study 1 measures for details of coding a worker’s perceived race). White workers received on average 4.79 stars (s.d. = 0.66) and non-white workers received on average 4.72 stars (s.d. = 0.75); this difference is statistically significant (t(55,711) = 10.55, P < 0.001). Breaking this down into racial categories, we see that Asian workers averaged 4.73 (s.d. = 0.76), Black workers averaged 4.69 (s.d. = 0.77), Hispanic/Latino workers averaged (4.79, s.d. = 0.66) and white non-Hispanic/Latino workers averaged 4.79 (s.d. = 0.66). We include these individuals as non-white because they are an ethnic minority. Workers who were perceived to be outside these categories received on average 4.79 stars (s.d. = 0.66). We grouped racial and ethnic minorities into ‘non-white’ because we do not have a theory for differences across minority groups. We provide our main results by race/ethnicity in supplementary analyses (Supplementary Information section 1.2 and Supplementary Table 6).

Although the mean difference of 0.07 stars between non-white and white workers before the rating-scale change may seem small, a worker’s rating is economically significant because it affects the income that a worker receives for completing a job on the SC platform. A job’s revenue is constant within each service category and cannot be negotiated; however, the actual income earned by a worker is calculated by multiplying a job’s revenue by that worker’s ‘income rate’, which is part of a multi-tiered system based on a worker’s average rating before the focal job. For example, workers who have an average rating between 4.80 and 4.89 stars may earn 80% of a job’s revenue, whereas workers who have an average rating between 4.70 stars and 4.79 stars may earn 70% of the same job’s revenue. Thus, minor fluctuations in rating, even as little as 0.01 stars, may shift a worker into a different income rate. On SC, the rating differential in the five-star scale resulted in non-white workers earning the lowest income rate 38.4% of the time, whereas white workers earned the lowest income rate 31.1% of the time (t(68,683) = −18.87, P < 0.001). This translated to non-white workers making about 91 cents for each US dollar earned by white workers, on average, and persists when analysing worker income in the same service category.

To compare whether the rating-scale change reduced racial discrepancies in ratings, the dependent variable, ‘ratings’, must be on a common metric. Consistent with our theory and how the scale was redesigned, we formed a dichotomous dependent variable, ‘highest rating’, that takes the value of 1 when a customer submits the highest rating on the scale used (that is, five stars or a thumbs up) and 0 when a customer submits a lower rating.

With highest rating as the dependent variable, we find that in the original rating scale, non-white workers received five stars 83.4% of the time, whereas white workers received five stars 86.9% of the time (t(55,711) = 10.84, P < 0.001). After the rating scale was changed to a binary assessment (thumbs up versus thumbs down), the difference between non-white and white workers in ratings was eliminated; the interaction between worker race (white versus non-white) and scale type (rating-scale change) is significant (Table 1, model 1; b = 0.03, s.e. = 0.005, t(32,176) = 6.08, P < .001, 95% CI, [0.02, 0.04]) and substantively eliminates the negative main relationship between ‘highest rating’ and ‘non-white’. After the thumbs up/down scale was implemented, white workers received the highest ratings 95.9% of the time and non-white workers received it 95.4% of the time, with no evidence for a difference (t(14,256) = 1.23, P = 0.217).

This amelioration of racial differences in ratings after the scale change is robust to inclusion of controls for worker, customer experience, customer, location and service type (Table 1, model 2), as well as customer fixed effects (Table 1, model 3). In the Supplementary Information, we examine the relationship between worker race and rating for each scale separately (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) and the robustness of our results across different model specifications. Our results are robust to focusing our analyses on customers who used SC before and after the rating scale changed (Supplementary Information section 1.2 and Supplementary Table 4, models 1 and 2) and on ratings that occur immediately before and after the rating-scale change (Supplementary Information section 1.2 and Supplementary Table 4, model 3). Across these models, we see consistent evidence that the relationship between highest rating and non-white is substantively and statistically eliminated after the rating scale changed from five stars to thumbs up/down; this indicates that the dichotomization of the scale eliminated the racial difference in ratings.

Race-based ratings gap reduced immediately after rating scale changed

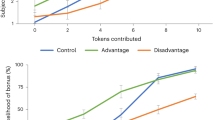

Although the rating-scale change was not randomized, it was an exogenous change. We use the quasi-natural experimental nature and exogeneity of the rating-scale change to better identify whether dichotomization is likely to be driving the elimination of the race-based differences observed in the five-star scale. Figure 2a plots the average value of the highest rating between non-white and white workers using 30-day increment buckets immediately before and after the rating-scale change. In the 30-day period before the change, non-white workers were significantly less likely to receive a five-star rating (highest rating = 1) relative to white workers (88.5% versus 92.4%, −3.9 percentage points; t(1,899) = 2.76, P = 0.006). However, in the 30-day period immediately after the rating-scale change, we do not find evidence for a difference in the likelihood of receiving a thumbs-up rating (highest rating = 1) related to a worker’s race (93.7% for non-white workers versus 94.1% for white workers, −0.4 percentage points; t(1,717) = 0.308, P = 0.758). The elimination of race-based differences in highest ratings immediately after the rating-scale change provides strong evidence that this effect is attributable to the shift from a five-star rating scale to a two-point (thumbs up/down) rating scale. Furthermore, it is also unlikely that confounding factors were present in this short window.

a, The average likelihood that a customer rates a completed job using highest rating (five stars or thumbs up) for white (dark grey) versus non-white (light grey) workers; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (n = 30,540). Observations were grouped into 30-day periods; negative values represent the five-star scale and positive values represent the thumbs up/down scale. Using the five-star scale, non-white workers had a lower likelihood of receiving the highest rating than white workers. Using the thumbs up/down scale, there is no evidence for a difference in the likelihood of receiving the highest rating after the rating-scale change. In the 30-day period before the rating-scale change, non-white workers were less likely to receive the highest rating (five stars) than white workers (88.5% versus 92.4%; −3.9 percentage points, t(1,899) = 2.76, P = 0.006, 95% confidence interval (CI), [−0.07, −0.01]). In the 30-day period after the rating-scale change, we do not find evidence for a race-based difference (93.7% for non-white workers versus 94.1% for white workers; −0.4 percentage points, t(1,717) = 0.308, P = 0.758). b, The marginal effects from Table 3 model 2 (n = 5,485). The sample includes workers who joined within 180 days of the rating-scale change. For workers who joined before the rating-scale change, only jobs completed before the change were analysed. Income is the normalized amount that workers received after completing the job, and error bars represent 95% CI. Using the five-star scale, white workers (crosses and solid line) earned a normalized income of 169.48 and non-white workers (triangles and dashed line) earned 136.67 (−32.81; t(4,939) = −3.27, P = 0.001, 95% CI, [−52.49, −13.14]). After the rating-scale change (to thumbs up/down), white workers earned 169.44 and non-white workers earned 179.00 (+9.56; t(4,939) = 1.15, P = 0.250, 95% CI, [−6.73, 25.85]).

Race-based income inequality is eliminated, but only for new workers

Given the link between a worker’s average rating and their income, we next examined whether the rating-scale change is related to the elimination of the race-based income inequality. We cannot disclose the raw dollar values for confidentiality reasons, but we normalized the revenue that SC charges for all completed jobs and then calculated the income as the revenue for a given job multiplied by the worker’s income rate. Table 2, model 1 shows the relationship between ‘income’ and ‘non-white’ before the rating-scale change. The negative estimate on non-white demonstrates that in the same service category, non-white workers received approximately 91 cents for each dollar earned by white workers.

After the rating-scale change, SC continued to base a worker’s income rate on their average rating to date, such that ratings received before the rating-scale change still affected their income. For non-white workers who joined the platform before the rating-scale change, their average rating included the lower ratings they were more likely to receive on the five-star scale. Thus, among workers who completed jobs and earned ratings before the scale change, worker income continues to be related to worker race, although the difference is attenuated because of the improvement in the race-based rating gap after the scale change (Table 2, model 2).

To isolate whether the elimination of the worker income difference is related to the rating-scale change, we must focus on the set of workers who joined SC after the scale change. These workers were only ever rated using the thumbs up/down scale and so were not subject to the race-related disparity in ratings on the original five-star scale. Among this set of workers, we see that there is no relationship between a worker’s perceived race and their income (Table 2, model 3). Non-white and white workers who were rated only on the thumbs up/down scale earned the same income when completing a similar job.

To better identify this relationship, we again use the quasi-natural experimental nature of the rating-scale change (Fig. 2a and Table 1). We identified workers who joined SC within 180 days of the rating-scale change and analysed the relationship between income and non-white. For workers who joined before the rating-scale change, we included only the jobs they completed before the rating-scale change (Table 3). Figure 2b plots the marginal effects from Table 3, model 2. This illustrates that the income received by white workers was not statistically different before versus after the rating-scale change (b = −0.048, s.e. = 9.065, t(4,939) = −0.01, P = 0.996, 95% CI, [−17.82, 17.72]). However, non-white workers received an increase to their income after the rating-scale change (b = 42.372, s.e. = 13.307, t(4,939) = 3.18, P = 0.001, 95% CI, [16.29, 68.46]), erasing the race-based income gap present in the period using the five-star rating scale.

Therefore, dichotomization of the scale is related to a reduction in racial inequalities in worker rating and thus income. Furthermore, the fact that the change occurred exogenously and the elimination of the racial differences in rating and income occur in the period immediately after the rating-scale change increase confidence that dichotomization is attenuating these differences.

Dichotomization in an online experiment

Although the results from study 1 are robust, we cannot causally establish that the observed rating differences were due to racial discrimination and not unobserved worker differences. We therefore conducted study 2 to replicate the effect we observed in the field with a causal, pre-registered, experimental paradigm that held worker quality constant. We also measured participants’ modern racist beliefs to examine whether the scale-equalizing effect is stronger among individuals holding these beliefs.

In this experiment, we randomly assigned 652 online-survey participants to one of four conditions, varying workers’ race (white (n = 328), non-white (n = 324)) and the rating scale used (five-star (n = 330), thumbs up/down (n = 322)) (Extended Data Fig. 1). We made several design choices to reduce socially desirable responding, which is common on online platforms and when studying race40. First, we sought a survey panel (Centiment) that is used primarily by marketing and business professionals (rather than those more commonly used by academics) to reduce non-naive responses and apprehension from survey participants about possibly being judged or evaluated by scientists, which might change their behaviour. Our institutional review board waived informed-consent procedures for this study (and the pilot, study F in Supplementary Information section 9) because we presented participants with minimal risk, and there was the potential for a consent form to change participants’ behaviour. Our study simply began by saying that we were “a new startup that uses a phone app to connect people to handymen and other service people, HomeServices. We are trying to get a better sense of how customers respond to different information. Please read each of the following four customer reviews.” For all the other experiments, we obtained informed consent from participants.

Participants read four positive customer reviews for a start-up home-services company. These reviews were accompanied by images of four white men in the ‘white’ condition or by images of two white and two non-white men in the ‘non-white’ condition (see study 2 in Methods and Fig. 3 for example stimuli). Importantly, all four positive reviews, and two of the white workers’ images, were consistent across conditions to ensure that the quality of the rated targets was identical in both worker-race conditions.

Participants in the non-white-workers condition viewed four customer testimonials including these two images. Participants in the white-workers condition in study 2 viewed four customer testimonials that displayed four white workers with identical customer testimonials. Full stimuli for studies 2 and 4 can be found on our OSF page (https://osf.io/mkbfp/). Credit: canva.com except faces, chicagofaces.org.

We presented participants with a group of four workers, rather than one individual worker, to reduce social desirability in responses that are especially common in online panels40,41. Specifically, presenting a group of individuals to rate, rather than a single individual, increases plausible deniability of potential discrimination, helping to reduce social desirability in responses38,40,42. In supplemental study C (Supplementary Information section 6), we show that white participants did indeed show significantly less social desirability when rating a group of workers that included two non-white workers versus when rating an individual non-white worker.

After reading the customer reviews, participants provided a rating of HomeServices Pro using a randomly assigned five-star or thumbs up/down scale. We asked participants to rate the organization rather than the workers to also reduce social desirability by creating psychological distance between participants and the rated targets, thereby increasing plausible deniability of potential discrimination43. Supplemental study D (Supplementary Information section 7) shows that white participants rating the organization (versus its workers) did indeed show significantly less social desirability in their responses.

At the end of the study, participants completed demographic measures in which we included an unobtrusive measure of participants’ modern racist beliefs using a single item (“How much employment discrimination do Blacks and other racial minorities face in the U.S.?”; 1 = none, 7 = a great deal, reverse-coded). This item has been included in established scales of contemporary racist beliefs, including symbolic racism44 and modern racism34. See study 2 in Methods for more details of the study design and supplemental study E (Supplementary Information section 8) for evidence of this measure’s construct validity.

We expected that using the thumbs up/down scale would result in less racial discrimination in participants’ ratings compared with using the five-star scale, specifically among participants with stronger modern racist beliefs. Following our pre-registered analysis plan, we conducted a linear regression predicting the standardized ratings from the scale condition (five stars = −1, thumbs up/down = 1), worker race condition (white = −1, non-white = 1), mean-centred participant modern racist beliefs, and all interaction terms (Supplementary Table 9). Supporting our predictions, we found a significant scale × worker race × modern racist beliefs three-way interaction effect predicting ratings (b = 0.05, s.e. = 0.02, t(644) = 2.32, P = 0.021, 95% CI, [0.01, 0.09], sr2 = 0.008). Results are consistent when using regression predicting the dichotomous highest rating as in study 1 (Supplementary Information section 2.3 and Supplementary Table 10).

To interpret the results, we decomposed this three-way interaction. Specifically, we examined the scale × worker race interaction effects at relatively high (+1 s.d.) and low (−1 s.d.) levels of participant modern racist beliefs (Fig. 4). Overall, this analysis showed that among those with stronger modern racist beliefs, using the thumbs up/down scale resulted in less racial discrimination in ratings compared with using the five-star scale (Supplementary Information section 2.2). Probing the interaction using the Johnson–Neyman technique45 showed that our predicted patterns of the scale × worker race two-way interaction effect were observed among participants with strong modern racist beliefs, that is, those who reported modern racist beliefs above 6.87 on the scale (10.28% of participants).

The predicted means of the standardized ratings as a function of scale condition, worker race condition and participant modern racist beliefs (at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean) in study 2 (n = 652). Error bars represent 95% CI. Participants with higher modern racist beliefs (+1 s.d.) who used the five-star scale rated non-white workers more negatively than white workers (b = −0.18, s.e. = 0.08, t(644) = −2.27, P = 0.023, 95% CI, [−0.34, −0.02], sr2 = 0.008). Participants with higher modern racist beliefs (+1 s.d.) who used the thumbs up/down scale did not differ in their ratings by worker race (b = −0.01, s.e. = 0.08, t(644) = −0.12, P = 0.906, 95% CI, [−0.16, 0.14], sr2 < 0.001). Participants with lower modern racist beliefs (−1s.d.) who used the five-star scale did not significantly differ in their ratings by worker race (b = 0.12, s.e. = 0.08, t(644) = 1.55, P = 0.123, 95% CI, [−0.03, 0.26], sr2 = 0.004). Similarly, participants with lower modern racist beliefs (−1s.d.) who used the thumbs up/down scale did not differ in their ratings by worker race (b = −0.07, s.e. = 0.08, t(644) = −0.90, P = 0.369, 95% CI, [−0.23, 0.08], sr2 = 0.001). This analysis was two-sided.

Interpretation of rating scales

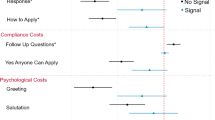

Study 3 was designed to directly examine our proposed mechanism: the perception that a five-star scale allows for the inclusion of raters’ personal opinions and beliefs (relative to a thumbs up/down scale). This study also clarifies that the mechanism underlying our observed effect is distinct from that driving the findings of ref. 24, which was that gender bias is reduced when using a six-point scale compared with a ten-point scale owing to associations between a rating of 10 and brilliance. To this end, we designed a four-condition, between-subjects experiment that randomly assigned participants to view one of four scales: five stars, thumbs up/down, six-point and ten-point. We then asked participants about the extent to which the rating scale would: first, allow participants to express their personal opinions and beliefs; second, encourage participants to focus on whether the target of the rating is good or bad quality; and third, capture customers’ biased opinions and beliefs about the target being rated.

We predicted that the thumbs up/down scale would be perceived as less suitable for expressing customers’ personal opinions, promoting a greater focus on judging good or bad performance, and capturing customers’ biased opinions and beliefs less compared with the five-star scale, as well as the six-point and ten-point scales. Although not included in our pre-registration, we were also interested in exploring how our measures differed when comparing the six-point and ten-point scale conditions, because this would allow us to examine whether our proposed mechanism is distinct from those of ref. 24. Specifically, we reasoned that if our proposed mechanisms are distinct from those driving the effects in ref. 24, we would expect there to be no differences in our dependent measures when comparing the six-point and ten-point scale conditions.

Following our pre-registered analysis plan, we conducted a series of three separate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) predicting our dependent measures from our rating-scale condition. In line with our predictions, participants reported that their personal opinions would be included less when using a thumbs up/down scale compared with scales with more points (Fig. 5a): five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 6.65, P = 0.010 partial eta squared (ηp2) = 0.005), six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 25.62, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02) and ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 41.37, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, and F(1, 1,431) = 33.60, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02 when contrast coding to compare all three multipoint scales to the thumbs up/down scale condition).

a–c, Bar graphs showing mean perceptions of expression of personal opinions (a), a focus on good versus bad (b) and capturing biased opinions (c) by scale condition in study 3; n = 1,435. Error bars represent 95% CI. The mean expression of personal opinions of the thumbs up/down scale was significantly lower than the five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 6.65, P = 0.010, ηp2 = 0.005), the six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 25.62, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02) and the ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 41.37, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03). The mean focus on good versus bad of the thumbs up/down scale was significantly higher than the five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 39.34, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03), the six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 79.55, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05) and the ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 90.09, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06). The mean capturing of biased opinions of the thumbs up/down scale was significantly lower than the five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 9.12, P = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.006), the six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 7.54, P = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.005) and the ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 5.18, P = 0.023, ηp2 = 0.004). All tests were two-sided.

Participants also reported that they would focus more on only good versus bad performance when using a thumbs up/down scale compared with a five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 39.34, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03), a six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 79.55, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05) and a ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 90.09, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, and F(1, 1,431) = 103.10, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07 when contrast coding to compare all three multipoint scales with the thumbs up/down scale condition; Fig. 5b).

Finally, again in support of our predictions, participants reported that biased opinions and beliefs are less likely to be captured in ratings using a thumbs up/down scale compared with a five-star scale (F(1, 1,431) = 9.12, P = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.006), a six-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 7.54, P = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.005) and a ten-point scale (F(1, 1,431) = 5.18, P = 0.023, ηp2 = 0.004, and F(1, 1,431) = 10.90, P < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.008 when contrast coding to compare all three multipoint scales with the thumbs up/down scale condition; Fig. 5c).

Notably, we did not find any differences in our three dependent measures when comparing those in the six-point versus ten-point scale conditions (0.165 < P < 0.656). These results indicate that our proposed mechanisms are likely to be distinct from those driving the effects present in ref. 24.

Dichotomous thinking with a five-point scale

In study 4, we designed a pre-registered experiment that manipulates the experience of dichotomization independently from the constraint that dichotomous scales introduce as a result of having fewer scale points. We did this by creating an intervention that instructed participants to focus only on whether the work itself was good or not when using the five-point scale. We then compared these ratings to the ratings of the non-white workers using the original five-star scale.

To ensure that we reached our sample of interest, we conducted a prescreen survey to identify white participants who had relatively high modern racist beliefs, and then exposed these participants to the non-white-worker condition from study 2. We then used a two-condition between-subjects design in which participants were randomly assigned to use either a five-star scale or a five-star scale with an intervention (intervention condition) to rate the company that employed the workers. In the intervention condition, participants were presented with a five-star scale and were also told “when answering this question, please focus ONLY on whether the work itself was good (5 stars) versus not (other values)”.

The purpose of the extra instructions in the intervention condition was to emulate an experience of using a dichotomous scale, without actually reducing the discretion of the five scale points. We predicted that participants in the intervention condition would rate the company more positively than participants using the five-star scale without the intervention would.

As per our pre-registered analysis plan, we conducted a t-test predicting ratings with our rating-scale conditions. As predicted, participants in the intervention condition (mean = 4.55, s.d. = 0.62) rated the company more highly than those in the five-star-scale condition (mean = 4.37, s.d.= 0.77, t(526) = 2.96, P = 0.003, 95% CI, [0.06, 0.30], Cohen’s d = 0.26). Importantly, participants in the intervention condition were still free to choose ratings that were not five stars (those who chose one star, n = 1; two stars, n = 1; three stars, n = 9; and four stars, n = 93). Nonetheless, we saw that participants holding modern racist beliefs were significantly more positive in their evaluations of non-white workers when the process of dichotomous thinking was induced (that is, a focus on whether the work was good or bad). Overall, these results indicate that instructing raters to focus on dichotomization, namely good versus bad performance, may help to reduce racial bias in ratings in a manner similar to using an explicitly dichotomous scale.

Conclusion and discussion

Our research combined a quasi-natural experiment in the field with three online survey experiments and eight supplemental studies to demonstrate that dichotomizing a rating scale attenuates consequential racial disparities in customers’ evaluations of workers. Dichotomous rating scales prompt customers to focus on whether the work itself was good or bad, and thus reduce the expression of subtle racism that occurs when scales are conducive to more fine-grained differentiation.

The current investigation focused on an intervention in the context of racial disparities, given that racial discrimination on online platforms has been robustly demonstrated1,10,11,12. However, we expect that a structural change in rating scale might also reduce similar group-based modern discrimination along other dimensions, such as gender, age and disability. Furthermore, we would expect similar findings to emerge beyond the domain of customer evaluations, especially in contexts in which quick, subjective performance evaluations occur, when group membership is made salient to one-time evaluators (for example, the use of photographs). We expect that this would be most readily observed in a context in which evaluators are not aware they are being studied, and in which researchers have sufficient power to detect small but consequential effects, such as through field data.

It is important to note that our studies focus on male workers; therefore, it is an open question whether these results differ when considering female workers or the intersectionality of race and gender. Future work investigating the generalizability of our findings on this issue would be fruitful46. In our context, workers and customers were matched on a first-come, first-served basis, and customers could cancel once they were assigned a worker. Therefore, future research should also explore whether and how customer choice between workers may affect observed discrimination and explore ways to mitigate discrimination that occurs in cancellations. Future research can also examine whether these effects hold outside the online evaluation context, whether and how the characteristics of the evaluators matter, and how the nature of the relationship between the evaluator and the evaluated individual may affect these findings. For instance, it would be useful to move beyond customers and online contexts to examine these effects among evaluators who repeatedly interact or have relationships with those being evaluated, such as at an in-person workplace.

We note that our results demonstrate a reduction in subtle discrimination consistent with contemporary racism that is observable in evaluations; we did not document changes in individuals’ biased beliefs or attitudes, which remains an important and pressing area of research, along with research that examines explicit forms of racism. We also note that our data do not include communications between workers and customers, customer demographics or workers’ self-disclosed racial identity. However, these characteristics are unaffected by the scale change and thus are unlikely to explain our results. Moreover, evaluations in the field study were conditional on having a job completed, thus customers who hold more-explicit racist attitudes may have cancelled. In our studies, it is also possible that people were exhibiting xenophobia rather than (or as well as) racism; for instance, in the experiments, participants may have assumed that Jose was Mexican or Kareem was Arabic. Although our methods were not able to tease this apart, the moderating effect of the ‘racist belief’ measure in study 2 indicates that the discrimination observed in the study was indeed driven by racism. However, it is possible that participants were also exhibiting anti-immigrant discrimination, which is also important to address. Finally, we note differences between the field study and our experiments, including the statistical power in the field study to detect small differences by race, complete anonymity/naivety, and real customers in the field study, as well as a paradigm in the lab designed to reduce social desirability (ratings of a platform based on worker reviews, rather than evaluations of individuals’ work).

These findings offer insights to researchers and practitioners on how to reduce certain racial inequalities. There has been little success in finding solutions for eliminating racial discrimination, particularly among individuals who hold stronger racist beliefs2 and for customers, who, unlike employees, are not subject to training, selection or recruitment processes. However, given the growing evidence of racial inequality in rating systems and their impact on workers in the gig economy, this problem is especially important to address. The difference we find in the online labour-market ratings (study 1), comparing white and non-white racial-minority workers on a five-star scale, might seem small, but these differences result in significant racial inequality regarding income. Using the five-star scale, non-white workers earned 91 cents for every dollar earned by white workers for doing the same work, because ratings were used to determine a worker’s income. Our research suggests a simple practical solution: dichotomizing the rating scale, which leads evaluators to focus on whether the worker exhibited good versus bad performance, reducing the expression of modern racist beliefs in the evaluation. This is consequential because the five-star scale is common in customer evaluation systems and dictate the dispersal of resources. For instance, many popular platforms use a five-star evaluation scale. The familiarity of the five-point scale may lead to its further diffusion and adoption.

Beyond racial inequality, it is useful to consider the broader potential externalities of dichotomization. Concerns include that moving from a five-star scale to a thumbs up/down scale will remove the detail available to customers and cause rating inflation. In the field study (study 1), after the rating-scale change, about 96% of ratings were thumbs up. Putting aside the possibility that workers on this platform are all high quality, customers and platforms may be concerned by this apparent inflation of performance ratings. However, it is worth noting that, similar to most consumer-facing platforms, ratings on SC were already inflated in the five-star scale. More than 85% of ratings were five stars before the change in rating scale, so it is unclear whether this inflation will hinder customer experience. Moreover, the inflation observed using the five-star scale indicates that a five-star scale is unlikely to yield extra and valuable information relative to a dichotomous scale. Illustrating this point, SC more recently started connecting customer complaints to specific jobs, and only 4.5% of completed jobs received a complaint (see Supplementary Information section 1.2). This likelihood corresponds to the percentage of thumbs-down ratings we observed (4.3%), and importantly, this is unrelated to worker race (see Supplementary Information section 1.2). One empirical advantage in our field setting is that, similar to many labour-market platforms, customers are matched to only one worker. However, some platforms allow customers to select a worker from a list. In this design, rating inflation may affect customers’ reliance on worker race and should be addressed in future research.

Another practical concern is that rating inflation may hinder the ability of the platform to manage workers and adjudicate performance in a detailed way. To better assess the full range of worker performance, platforms might also consider giving customers a direct way to raise quality concerns or suggestions for improvement, expanding the number of dimensions on which customers dichotomously rate workers, and setting up more in-depth assessments, such as through standardized, ‘secret shopper’ evaluations completed by trained experts. However, more research is needed to determine whether these alternative suggestions mitigate racial discrimination.

Overall, evaluation processes that use dichotomized scales show promise for reducing racial inequalities in evaluations and hence income relative to the ubiquitous five-star scale. Our results show that such dichotomization of rating scales is related to an elimination of the race-based rating and income inequalities that were present using the five-star scale.

Methods

Experimental studies were approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board, protocol 39570 “Understanding discrimination in the gig economy”, approved on 8 March 2022. This includes alterations to consent and debriefing requirements for study 2 (and the associated pilot), consistent with the Canadian federal research ethics guidelines, the Tri-council policy statement ‘Ethical conduct for research involving humans, 2nd edition (TCPS 2)’, articles 3.7 A and B, and the University of Toronto’s guidelines regarding deception and debriefing in research. Rice University and Yale University also supplied reciprocal research ethics board approval.

Study 1 context

Our first study used archival data from an online labour-market platform operating in the United States and Canada, which we refer to as SC (a pseudonym). Workers must apply for approval to work on the platform and are rigorously evaluated by SC in an interview, a verification of skills and a background check. A customer creates a job on SC by completing a survey to detail the job they want completed. Jobs fit into one of 15 unique service categories (such as appliance repair or maintenance) and usually take around a couple of hours to complete. The cost of a job is constant within the service category and is non-negotiable.

SC uses a simple algorithm to match customers to workers. The algorithm prioritizes a small set of workers on the basis of a worker’s number of jobs completed, a worker’s average rating, and whether the worker has another job in that area on the customer’s preferred day. Prioritized workers have 15 min to accept the job on a first-come, first-served basis. If the job is not accepted in 15 min, any worker who is approved to work in that service category can accept the job on a first-come, first-served basis.

Customer characteristics and worker demographics are not recorded, nor are they direct inputs into the algorithm, so the customer–worker match is unrelated to customer and worker demographics. Moreover, customers have no control over the matching process and do not choose between workers. Once a worker accepts the job, the customer receives an e-mail message providing the worker’s name, photo, average rating to date and number of jobs completed to date (Fig. 1a). The organization does not provide workers’ demographic information to customers, but the worker’s photo is e-mailed, which can lead to the automatic perception of race47,48.

After the job has been completed, the customer receives another e-mail that gives them the opportunity to evaluate the worker. SC updated the customer rating process overnight by changing the rating scale from five stars (Fig. 1b), for which customers could choose an integer star rating to assess the worker, to a two-point scale (Fig. 1c), for which customers choose either a thumbs up or a thumbs down. The management at SC thought that this change would simplify the rating process. They did not communicate their intentions to change the rating scale, nor did they communicate any reasons for the scale change to customers.

We examined a total sample of 100,759 completed jobs, and customers chose to rate workers for 69,971 of these jobs (our main analytical sample). Analysing completed jobs makes our examination of inequality in this context arguably conservative, because results are conditional on customers not cancelling the job once assigned to a worker. We examine the rating selection processes in Supplementary Information section 1.2 (Supplementary Table 5). Of the total sample, 20,679 jobs occurred after the rating scale was changed. This setting provides an unobtrusive, well-powered examination of race dynamics in an online labour platform.

Study 1 measures

Highest rating

The main outcome of interest is the evaluation that a customer gives to a worker. On the original rating scale, customers could choose one of five different outcomes (1–5 stars in integers), responding to the message: “We are proud to work with our terrific contractors. Please take a second to rate them below! RATE YOUR CONTRACTOR!” On the new rating scale, customers could choose one of two different outcomes (thumbs up or thumbs down), responding to the question: “Would you be happy to be matched with this contractor again?” Given that we are interested in the relationship between workers’ perceived race and customer ratings across these two different scales in a regression, we needed a dependent variable that is comparable across both scales (that is, a single metric). We formed a dependent variable labelled ‘highest rating’, which takes the value of 1 if the customer submitted the maximum rating on the scale used (five stars or thumbs up) and 0 if the customer submitted any other rating (1–4 stars or thumbs down). Supplemental study A (Supplementary Information section 4) addresses the question stem difference between the five-star scale and the thumbs up/down scale as a potential alternative explanation for the results.

Income

Customers pay the same amount in the same service category, and this amount cannot be negotiated. A worker’s income is a percentage of this total amount, for which the percentage is determined by the worker’s average rating to date (their income rate). An income rate is applied after a worker has completed their first few jobs. The income represents the total dollar amount earned by a worker. This measure is normalized and we do not provide its summary statistics because we cannot disclose the raw dollar figures.

Intervention period

Rating-scale change takes the value of 1 if customers submitted their rating using the thumbs up/down scale and 0 if customers submitted their rating using the five-star scale.

Worker perceived race

SC does not collect workers’ demographic information. After a customer–worker match, SC sends customers an e-mail that contains a picture of the worker who will be completing the work (Fig. 1a). Pictures can lead to an automatic perception of race14,48. To mimic the data-generation process, we are not interested in a worker’s actual racial identity, but instead how customers are likely to perceive the worker’s race. We achieved this by having two coders independently review the profile photo of each worker on SC and record their perceptions of the individual’s race. Agreement between coders was initially 94%; in cases of disagreement, the coders discussed the photos to reach a consensus. ‘Non-white’ takes the value of 1 when a worker was perceived by our coders as non-white, and 0 when a worker was perceived as white. Hispanic/Latino workers and workers whose race was coded in a rare category (for example, Pacific Islander) or ‘other’ were included in the non-white category. We included these workers in our non-white category to be conservative in our estimates, but we also note that results are consistent no matter how this group is categorized (as white or non-white). Of the 100,759 completed jobs, 11% were completed by Asian workers, 16% were completed by Black workers, 2% were completed by Hispanic workers, 69% were completed by White workers, and 3% were completed by workers categorized as ‘non-white other’.

Control variables

Results are consistent with and without covariates and across specifications. We describe the covariates used in the main analyses below and detail several robustness models in Supplementary Information section 1. At the customer level, we controlled for a customer’s experience with SC at the time the worker accepts the focal job. ‘Experienced customer’ takes the value of 1 if the customer has requested an above-the-median number of jobs at the time the worker accepts the job, and 0 otherwise. We also include fixed effects for the metropolitan area (location) where the customer lives, based on ZIP codes. We include fixed effects for the job’s service category. At the worker level, we controlled for the number of jobs a worker has completed and their rating at the time they accept the job. Experienced worker takes the value of 1 if the worker has completed more than the median number of jobs, and 0 otherwise. Highly rated worker takes the value of 1 if the worker’s average rating at the time of accepting the job is above the median relative to other workers, and 0 otherwise. Our results are unaffected by using continuous controls (Supplementary Information section 1 and Supplementary Table 7).

Study 2

We designed an experiment to test whether using a two-point scale can causally ameliorate the racially biased evaluations observed in a five-point scale. We also wanted to test whether the effect was especially prominent among individuals holding modern racist beliefs. To replicate and extend the findings of study 1 using a causal paradigm, all information was held constant across conditions, except for worker race and rating scale.

Empirical approach and pilot testing

When we considered experimental designs, we made several empirical choices that were necessary deviations from the field context and warrant explanation here. Specifically, unlike in our field study, which was completely unobtrusive (that is, customers did not know they were being examined), studying individuals’ racist beliefs and behaviours in lab experiments can be challenging because white Americans are motivated to appear less prejudiced36,49. This is particularly an issue on online survey platforms40; participants on online platforms know they are being studied and have often completed many social-science studies, meaning they are not naive. As a result, we expected that socially desirable responses would be prevalent, making the detection of a small effect especially difficult in a lab experiment40,41, where we would also not have as much power as we did in the large-scale field observations.

Therefore, we made two main empirical deviations from the field-study context to help reduce possible demand effects and social desirability pressure in the experimental study, both of which have been substantiated by supplemental studies (Supplementary Information sections 6–9). These changes should allow more precision in our models. First, to help obfuscate the purpose of the study, we exposed participants to reviews of four workers, rather than to a single worker. Supplemental study C (Supplementary Information section 6) documents that white participants did indeed show less social desirability in responses when rating a group of racial-minority workers versus rating an individual racial-minority worker.

Relatedly, our instructions in our main experiment asked participants to rate the platform (HomeServices Pro) rather than rate the workers. Although it is possible that when rating the organization respondents are thinking about organizational reputation versus their own beliefs, this measure should show high convergence with individuals’ beliefs about the status of individuals from racial groups affiliated with the organization. This argument is supported by literature showing that people project their own biases onto others, and this increased distance between the rater and rated target can help to better identify individuals’ honest stereotypical beliefs by reducing social desirability43. Supplemental study D (Supplementary Information section 7) shows evidence that white participants show less social desirability in responses when instructed to rate the organization versus its workers.

Supplemental study E (Supplementary Information section 8) addresses two more empirical issues. First, we examined whether a single-item measure for modern racist beliefs showed convergent validity with longer-established measures of contemporary racist beliefs (Supplementary Table 11). This is because we include this single item in the main experiment to help reduce participants’ awareness of the purpose of the study. Second, in this supplemental study we also document evidence for our assumption that when participants are using a five-star scale, they feel more encouraged to include their personal beliefs and opinions in their evaluations, but when they are using a thumbs up/down scale, they feel less encouraged to do so.

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/31P_L85). Data and materials are located in our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/). All studies received university institutional review board approval (ERB protocol 39570). We also note that we ran a pilot test of the full study 2 that showed results consistent with those reported here (Supplementary Information section 9 and Supplementary Table 12).

Participants

On the basis of a pilot study, we predetermined to collect 650 complete responses in which participants passed a bot-check question, with the intention of recruiting approximately 150 participants for each cell of the design. We recruited US-based adult participants using the Centiment panel service, which balances participant recruitment based on demographics and location. We collected a total of 807 responses, 652 of which were complete. We focused our analyses on these 652 responses (from 311 men, 330 women, 5 non-binary/third gender and 6 who preferred not to say; mean age = 49.86, s.d. = 16.98). Results with incomplete data and failed bot checks are consistent with those reported here. We chose not to measure participants’ race in this study because doing so might shape how participants respond to the racist-beliefs measure, also positioned in the demographic section. However, we note that the panel was balanced on demographics and location to be representative of the US population.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 2 used a two (race: white versus non-white) by two (rating scale: five-star versus thumbs up/down) between-subjects experimental design. In our research design, participants were unaware they were in an academic research study, which is particularly important for studies of racist beliefs40. Specifically, we told participants that we were a new start-up company called HomeServices Pro that uses an app to connect people with home-service providers and that the survey was designed to help us learn about how customers respond to different information. After reading this introduction, participants were asked to read four positive customer testimonials in randomized order (for example, “Overall, I’m pleased with the tile work that Matt did in my bathroom.”). Each customer testimonial had a photo of the worker being referenced (from the Chicago Face Database50). To manipulate worker race, participants were randomly assigned to read identical customer testimonials that either referred to four separate white workers (the white workers condition) or two white workers and two racial-minority workers (one Black and one non-white Hispanic/Latino man; the non-white workers condition; see Fig. 3 for example stimuli). The manipulation therefore varied only whether participants viewed two more white workers or racial-minority workers.

Next, participants were asked: “Based on these reviews, what rating would you give HomeServices Pro?”. They were then randomly assigned to use a thumbs up/down or a five-star scale to respond (Extended Data Fig. 1). We standardized these ratings with respect to each scale and combined them to be able to compare participants’ ratings on the same metric, as specified in the pre-registration. Even so, results are consistent when running the same analysis as study 1 using a dichotomous outcome variable (Supplementary Table 10).

Participants subsequently reported their gender and age and then were asked three questions about their political opinions in randomized order, in which our measure of modern racist beliefs was embedded. We measured participants’ modern racist beliefs with the single item: “How much employment discrimination do Blacks and other racial minorities face in the U.S.?” (1 = none to 7 = a great deal), adapting items from the symbolic racist-beliefs scale (“How much discrimination against blacks do you feel there is in the United States today, limiting their chances to get ahead?”44) and modern racist-beliefs scale (“Discrimination against Blacks is no longer a problem in the United States”34). Separate t-tests showed that this measure was not affected by scale condition (t(650) = −1.28, P = 0.200, Cohen’s d = −0.10) or worker race condition (t(650) = −0.14, P = 0.892, Cohen’s d = −0.01). This measure was reverse-coded such that higher values represented greater modern racist beliefs (reluctance to acknowledge the existence of racial discrimination; mean = 3.69, s.d. = 1.79). The last two questions about political opinions were filler questions about economic conservatism based on questions that appeared in the Pew Research Center survey on political polarization from 2001 (see all the measures on OSF). Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Study 3

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/5Y4_7D4). Data and materials are available from our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/).

Participants

We predetermined to collect 1,500 complete responses from US-based adult participants through Prolific on the basis of a pilot study. We collected a total of 1,589 responses, 1,503 of which were complete. Following our pre-registration plan, we excluded from our analyses the responses from 50 participants who were suspected of taking the survey more than once (based on time stamps and duplicated IP addresses; we did not observe any duplicated Prolific identities). We also excluded from our analyses the responses from 18 participants who did not provide the correct answer to our reading-comprehension check question. This left us with a final sample size of 1,435 (693 men, 706 women, 28 non-binary/third gender and 8 who preferred not to say; mean age = 39.85, s.d. = 13.31; 923 white, 202 Black, 96 Latino, 145 Asian, 7 Native American, 2 Pacific Islander, 60 multi-race or ‘other’). Results with incomplete data and failed reading-comprehension checks are consistent with those reported here.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 3 used a four-condition (rating scale: five-star versus thumbs up/down versus six-point versus ten-point) between-subjects experimental design. Participants were randomly assigned to view one of the four rating scales and were presented with our three dependent measures: expression of personal opinions, focus on good versus bad, and captures biased opinions. We first measured participants’ perceptions of expression of personal opinions, which read: “Please look at the commonly used question in the image above. When using this question to rate an object or target, to what extent do you agree that it would… (a) allow you to sufficiently express your opinions, (b) allow you to freely express your feelings about the object or target, (c) encourage you to use your own opinions in your evaluation and (d) make you feel like it’s legitimate to include your own opinions and beliefs in your evaluation” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.91). On the same page, participants were asked about their focus on good versus bad performance with the question: “Continuing to think about the image we showed you above, to what extent does it encourage you to focus only on whether the object or target is good versus bad (NOT including your personal opinions)?”. Finally, on the subsequent page, participants were again shown their randomly assigned rating scale and were asked: “When customers use this question to rate an object or target, to what extent do you agree that it would… (a) capture customers’ biased opinions?, (b) allow customers to freely express their biased feelings about the object or target, (c) encourage customers to use their biased opinions in their evaluation, and (d) make customers feel like it’s legitimate to include their biased opinions and beliefs in their evaluation?” (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.90). These four items constituted our measure of ‘captures biased opinions’, assessing the extent to which participants thought each of the four rating scales allowed for biased opinions (such as racist beliefs) to be included in one’s ratings. We intentionally made customers the referent of this measure, rather than the focal participant, to reduce potential social desirability in responses when asking about one’s own biased behaviour43.

As an exploratory measure, we assessed participants’ level of exposure to the rating scales they were asked about when evaluating products and services (1 = I never use this scale, 7 = I always use this scale; Supplementary Information section 3).

Participants subsequently responded to our reading-comprehension check question and reported their gender, age, race, political conservatism, level of education, English proficiency, voluntary comments about the study and Prolific identity before exiting the survey website. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Study 4

Pre-registration

We pre-registered the design and analysis plan for this study (https://aspredicted.org/4LB_F65). Data and materials are available from our OSF folder (https://osf.io/mkbfp/).

Participants

We conducted prescreen surveys of white US-based participants on Connect, which contained a single-item measure of modern racist beliefs from study 2 along with five filler questions. We identified white participants who had relatively strong modern racist beliefs by selecting those who responded with a 5, 6 or 7 on the modern racist beliefs scale, and invited them to participate in study 4. For study 4, we predetermined to collect 570 responses on the basis of a pilot study. We ended up with a total of 580 responses, 571 of which were complete. Following our pre-registration plan, we excluded from analyses the responses of five participants who were suspected of taking the survey more than once (based on time stamps and duplicated IP addresses), 29 responses from participants who indicated they were not white, 6 response from participants who incorrectly answered an open-ended bot-screening question, and three responses from participants who incorrectly answered our third bot question (all passed the second bot question). This left us with a final sample of 528 white participants (283 men, 244 women, 1 preferred not to say; mean age = 43.12, s.d. = 12.75). Results with incomplete data and failed bot checks are consistent with those reported here.

Procedure, manipulation and measures

Study 4 used a two-condition (rating scale: five-star versus five-star with intervention) between-subjects experimental design. The design of the study was similar to that of study 2, except: first, all participants were asked to rate a company with two non-white workers and two white workers (the non-white workers condition in study 2; see Fig. 3 for example stimuli); second, study 4 did not include a measure of racist beliefs (because we measured this separately before recruiting participants); and third, study 4 included a ‘five-star with intervention’ condition and omitted the thumbs up/down scale condition. Thus, all participants viewed customer testimonials of four workers of a company (including racial-minority workers) and were asked to rate the company using the scale they were randomly assigned to. Participants then completed a demographics questionnaire, completed three bot-check questions, and exited the survey website. Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Our manipulation of the five-star scale was identical to that in study 2. In the intervention condition, participants saw the same five-star scale with the extra text: “when answering this question, please focus ONLY on whether the work itself was good (5 stars) versus not (other values)”. In a separate pre-registered study (https://aspredicted.org/JMQ_X39; Supplementary Information section 11) with a separate sample of 287 participants, participants in the intervention condition rated the scale as making them feel significantly less open to including their opinions and beliefs (mean = 4.19, s.d. = 1.79) than participants in the five-star scale condition (mean = 5.40, s.d. = 1.48), t(285) = −6.23, P < 0.001, 95% CI, [−1.59, −0.82], Cohen’s d = −0.74. Furthermore, participants in the intervention condition (mean = 5.70, s.d. = 1.41) reported that the scale would encourage them to focus on good or bad performance significantly more than those in the five-star scale condition (mean = 5.16, s.d. = 1.58), t(285) = 3.07, P = 0.002, 95% CI, [0.20, 0.89], Cohen’s d = 0.36. Overall, this separate pre-registered experiment ensured that we designed a successful intervention in study 4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Detailed data and code for study 1 are not available owing to the data-use agreement between the lead authors’ institutions and ServicesConnect (not the company's real name). This agreement was executed by the relevant departments of Yale University and the University of Toronto, and abided by the university norms of data access and scientific research. The data-use agreement does not allow for any limitation regarding the topics that the researchers can study. Per the agreement, SC can review produced research to ensure that no confidential information is included, and relatedly, researchers cannot share the data, because it is considered highly sensitive by SC. Although SC does not allow for the data to be shared or posted, the authors will collect detailed data requests for three months after the publication date. They will then send a summary version of received requests to SC for their review. If SC allows data to be shared per this request, the authors will contact the requestors. All data and materials for studies 2–4 and supplemental studies A–H are available from the OSF repository at https://osf.io/mkbfp/. Pre-registration documents for applicable studies are also available from the OSF repository.

Code availability

A log of the code for the results of study 1 is available from the project’s OSF site (https://osf.io/mkbfp/). Data, experimental materials and R codes used to produce analyses and figures for studies 2–4 and all supplemental studies are also available from the OSF site.

References

Edelman, B., Luca, M. & Svirsky, D. Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: evidence from a field experiment. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 9, 1–22 (2017).

Chang, E. H. et al. The mixed effects of online diversity training. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7778–7783 (2019).

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F. & Kelly, E. Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. Am. Sociol. Rev. 71, 589–617 (2006).

Dellarocas, C. The digitization of word of mouth: promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Manage. Sci. 49, 1407–1424 (2003).

Luca, M. Reviews, Reputation, and Revenue: The Case of Yelp.com. Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working Paper No. 12-016 (Harvard Business School, 2016).

Small, M. L. & Pager, D. Sociological perspectives on racial discrimination. J. Econ. Perspect. 34, 49–67 (2020).

Botelho, T. L. From audience to evaluator: when visibility into prior evaluations leads to convergence or divergence in subsequent evaluations among professionals. Organ. Sci. 35, 1682–1703 (2024).

Parsons, C. A., Sulaeman, J., Yates, M. C. & Hamermesh, D. S. Strike three: discrimination, incentives, and evaluation. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 1410–1435 (2011).

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S. & Wormley, W. M. Effects of Race on Organizational Experiences, Job Performance Evaluations, and Career Outcomes. Acad. Manage. J. 33, 64–86 (1990).

Hannák, A. et al. Bias in online freelance marketplaces: evidence from TaskRabbit and Fiverr. In CSCW ’17: Proc. 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (eds Lee, C. P. & Poltrock, S.) 1914–1933 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2017).

Hangartner, D., Kopp, D. & Siegenthaler, M. Monitoring hiring discrimination through online recruitment platforms. Nature 589, 572–576 (2021).

Cui, R., Li, J. & Zhang, D. J. Reducing discrimination with reviews in the sharing economy: evidence from field experiments on Airbnb. Manage. Sci. 66, 1071–1094 (2020).

Berger, J., Cohen, B. P. & Zelditch, M. Status characteristics and social interaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 37, 241–255 (1972).

Greenwald, A. G. & Banaji, M. R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 102, 4–27 (1995).

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S. & Shelton, J. N. A lesson in bias: the relationship between implicit racial bias and performance in pedagogical contexts. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 63, 50–55 (2016).

Lowery, B. S., Hardin, C. D. & Sinclair, S. Social influence effects on automatic racial prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 842–855 (2001).

Biernat, M. & Kobrynowicz, D. Gender- and race-based standards of competence: lower minimum standards but higher ability standards for devalued groups. J. Pers. Soc.Psychol. 72, 544–557 (1997).

Foschi, M. Double standards for competence: theory and research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 21–42 (2000).

Botelho, T. L. & Abraham, M. Pursuing quality: how search costs and uncertainty magnify gender-based double standards in a multistage evaluation process. Admin. Sci. Q. https://doi.org/10.1177/000183921769435 (2017).

Dobbin, F., Schrage, D. & Kalev, A. Rage against the iron cage: the varied effects of bureaucratic personnel reforms on diversity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 80, 1014–1044 (2015).

Thaler, R. H. & Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (Penguin, 2009).

Camilleri, A. R. & Larrick, R. P. Metric and scale design as choice architecture tools. J. Public Policy Mark. 33, 108–125 (2014).

Schwarz, N. Self-reports: how the questions shape the answers. Am. Psychol. 54, 93–105 (1999).

Rivera, L. A. & Tilcsik, A. Scaling down inequality: rating scales, gender bias, and the architecture of evaluation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 248–274 (2019).

Abraham, M., Botelho, T. L. & Lamont-Dobbin, G. The (re)production of inequality in evaluations: A unifying framework outlining the drivers of gender and racial differences in evaluative outcomes. Res. Organ. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2024.100207 (2024).

Dovidio, J. F. & Gaertner, S. L. Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychol. Sci. 11, 315–319 (2000).

McConahay, J. B. & Hough, J. C. Symbolic racism. J. Soc. Issues 32, 23–45 (1976).

Pettigrew, T. F. & Meertens, R. W. Subtle and blatant prejudice in western Europe. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 25, 57–75 (1995).

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S. & Hunter, B. A. Sexism and racism: old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 199–214 (1995).

Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M. & Dovidio, J. F. Formal and interpersonal discrimination: a field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 815–825 (2002).

Jones, K. P., Peddie, C. I., Gilrane, V. L., King, E. B. & Gray, A. L. Not so subtle: a meta-analytic investigation of the correlates of subtle and overt discrimination. J. Manage. 42, 1588–1613 (2016).

Dovidio, J. F. & Gaertner, S. L. Affirmative action, unintentional racial biases, and intergroup relations. J. Soc. Issues 52, 51–75 (1996).

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M. & Unzueta, M. M. Deny, distance, or dismantle? How White Americans manage a privileged ddentity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 594–609 (2014).

McConahay, J. B. in Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism (eds Dovidio, J. F. & Gaertner, S. L.) 91–125 (Academic, 1986).

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M. & Malle, B. F. Social dominance orientation: a personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67, 741–763 (1994).

Apfelbaum, E. P., Sommers, S. R. & Norton, M. I. Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 918–932 (2008).

Penner, A. M. Race and gender differences in wages: the role of occupational sorting at the point of hire. Sociol. Q. 49, 597–614 (2008).