Abstract

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) is a local non-thermal ablative technique currently used to treat solid tumors. Here, we investigated the clinical potency and safety of IRE with an endoscope in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Pigs were electroporated with recently designed endoscopic IRE catheters in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Two successive strategies were introduced to optimize the electrical energy for the digestive tract. First, each organ was electroporated and the energy upscaled to confirm the upper limit energy inducing improper tissue results, including bleeding and perforation. Excluding the unacceptable energy from the first step, consecutive electroporations were performed with stepwise reductions in energy to identify the energy that damaged each layer. Inceptive research into inappropriate electrical intensity contributed to extensive hemorrhage and bowel perforation for each tissue above a certain energy threshold. However, experiments performed below the precluded energy accompanying hematoxylin and eosin staining and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assays showed that damaged mucosal area and depth significantly decreased with decreased energy. Relevant histopathology showed infiltration of inflammatory cells with pyknotic nuclei at the electroporated lesion. This investigation demonstrated the possibility of endoscopic IRE in mucosal dysplasia or early malignant tumors of the hollow viscus.

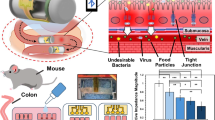

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancer is a major health concern worldwide with high incidence and mortality rates. Stomach and colorectal cancer are the 5th (5.7%) and 3rd (10.2%) most common cancers globally, representing the 3rd (8.2%) and 2nd (9.2%) leading causes of cancer-related death, respectively1. The cost of medical care for these cancers, especially asymptomatic cancers, is expected to increase substantially, becoming a growing social burden2. At the time of diagnosis, 30–50% of gastric cancers are at advanced stages, while approximately 6.3–9% show distant metastases3. Locally advanced unresectable and metastatic gastric cancer has a poor prognosis, with a 20–30% 5-year survival rate4. Thus, early detection via endoscopy and surgical resection are crucial for the management of GI cancer.

With the efficacy of perioperative chemotherapy depending on the surgical procedure remaining insufficient, the standard treatment for locally advanced gastric cancer remains unclear5. Advances in the development of endoscopic techniques have enabled local stent treatment, and image-guided percutaneous thermal ablation has been implemented for treating focal and locally advanced tumors since the 1990s6,7.

Recently, a new ablation technique called irreversible electroporation (IRE) was developed and includes electropermeabilization, which induces cell membrane perforation by an external electric field8. Electrical stimulation of the cell membrane changes the transmembrane potential and increases conductivity and permeability, resulting in permanent nano-sized aqueous pores on the cell membrane that eventually cause cell death9.

IRE possesses unique features that overcome the limitations of thermal ablation therapy, including the prevention of heat-generated damage to the surrounding normal tissue and incomplete ablation due to adjacent blood flow10. One distinct advantage is that the ablative effect is not affected by the heat sink effect because it uses non-thermal energy. Since tissue IRE first showed a potential ablative effect in the liver11, subsequent analogous studies have been reported in solid organs, including the pancreas12, prostate13, and kidney14.

IRE studies have mainly focused on solid organs using surgical or percutaneous methods. However, this investigation suggests the use of non-invasive IRE therapy on hollow viscus tissues. This is the first endoscopic in vivo animal IRE study performed in the upper GI tract. We aimed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of a newly designed endoscopic IRE for the GI tract in a swine model.

Results

Phase 1: Escalating voltage to investigate upper threshold energy of IRE

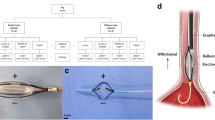

Figure 1 presents a drawing of the relevant endoscopic IRE procedures. A total of seven ablations were performed on each pig using the IRE equipment (Fig. 2). The duodenum and stomach were ablated at 1500 V and 2000 V, and the esophagus was ablated at 1500 V, 2000 V, and 2500 V. Based on the histopathological findings, the lowest electrical voltage to induce unfavorable events was 2500 V (1191 V/cm) in the esophagus, 2000 V (2000 V/cm) in the stomach, and 2000 V (952.4 V/cm) in the duodenum. The corresponding average electrical currents were 7.3, 4.0, and 5.8 A, respectively. Each electrical intensity above provoked hemorrhage in the stomach and perforation in the esophagus and duodenum (Fig. 3).

Irreversible electroporation (IRE)–related equipment specifications. Presentation of endoscopic catheters for (a) stomach (electrode diameter: 1.57 mm; exposed electrode length: 20 mm; distance between two electrodes: 10 mm), (b) esophagus and duodenum (electrode length: 5 mm; electrode width: 1.34 mm; distance between two electrodes: 20.9 mm) (1500 V/cm) with (c) square-shaped electrical monopolar pulse wave (pulse frequency, 10 Hz; amplitude: 1000 V, 1500 V, or 2000 V; pulse duration, 100 µs; pulse interval, 100 ms, and a fixed pulse number of 40) showing the electric field intensity of the (d) needle-type catheter and (e) basket-type catheter created by using Epocode™ (The Standard Co. Ltd.).

Histologic findings of adverse events in the phase 1 study. (a) Partial loss of the muscularis propria and surrounding inflammation with necrotic changes were exhibited at the ablation site of the esophagus treated with 2500 V (1190.5 V/cm). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 20 × magnification. (b) Diffuse mucosal necrosis with extensive hemorrhaging in the submucosal layer were observed after ablation of the stomach at 2000 V (2000 V/cm). H&E, 40 × magnification. (c) The muscularis propria and submucosal layers showed complete destruction and submucosal hemorrhaging with congestion with ablation of the duodenum at 2000 V (952.4 V/cm). H&E, 20 × magnification. (d) normal esophagus. (e) normal stomach. (f) normal duodenum. H&E, 40 × magnification.

Phase 2: De-escalating voltage to investigate the intensity at which the superficial layer was damaged

Depending on phase 1 findings, electrical energy values (2500 V) causing transmural damage were excluded. Accordingly, the esophagus was electroporated at 2000 V and 1500 V, while the stomach and duodenum were ablated at 1500 V and 1000 V, respectively.

The ablation depth and damaged mucosal areas were recorded according to the electrical energy applied (Table 1). The electrical voltages corresponding to muscularis mucosa damage were 1500 V (714.3 V/cm), 1000 V (1000 V/cm), and 1000 V (476.2 V/cm), while those related to submucosal damage were 2000 V (952.4 V/cm), 1500 V (1500 V/cm), and 1500 V (714.3 V/cm) in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, respectively.

As Fig. 4 shows, the mucosal ablated area noted on gross tissue inspection after the application of 1500 V in the esophagus decreased significantly from a mean 18.3 mm2 to 8.2 mm2 (p = 0.0495) compared to that at 2000 V. In the stomach and duodenum, the electroporated area induced by 1000 V decreased significantly from 9.6 mm2 to 3.1 mm2 and 33.6 mm2 to 10.5 mm2, respectively (stomach: p = 0.0463; duodenum: p = 0.0495), compared to that induced by 1500 V (Supplementary Table S1).

Comparison of scatter plot of electroporated area and depth by organ with electrical intensity in the phase 2 study. (a) Damaged surface area of the mucosa at 24 h after irreversible electroporation using the Image J program (version 1.8, National Institutes of Health). (b) Histologic depth scoring as follows: 1, lamina propria; 2, muscularis mucosa; 3, submucosa 1 (half above); 4, submucosa 2 (half below); 5, muscularis propria. Bar indicates median (n = 3). The Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05) was used.

Electroporated depth decreased from the submucosa to the muscularis mucosa at 1500 V in the esophagus and 1000 V in the duodenum. The produced lamina propria (LP) layer depth after the application of 1000 V in the stomach was shallower than that after the application of 1500 V in the submucosal layer.

Immediate endoscopic view and tissue evaluation after 24 h

Immediately after IRE at 1500 V in the esophagus, the mucosa in contact with the electrodes turned whitish (Fig. 5a). Unlike in the esophagus, the stomach’s electroporated mucosa showed pale snowman-shaped edema, with an erythematous peripheral rim and erosion after IRE at 1000 V (Fig. 5f). In the duodenum, the ablated mucosa exhibited a rectangular-shaped erythematous change after electroporation at 1000 V (Fig. 5k).

Endoscopic, gross inspection, and histopathology views after irreversible electroporation (IRE) in the phase 2 study. The first row represents the esophageal ablation effect at 1500 V (717.7 V/cm), the second row is the result of ablation of the stomach at 1000 V (1000 V/cm), and the third row shows the duodenal ablation results at 1000 V (478.5 V/cm). First column: endoscopic view immediately after IRE ablation of (a) esophagus, (f) stomach, and (k) duodenum. Second column: tissue gross inspection 24 h after IRE ablation of (b) esophagus, (g) stomach, and (l) duodenum. Third column: hematoxylin and eosin staining of electroporated (c) esophagus, (h) stomach, and (m) duodenum (black arrowhead; non-ablated area, yellow arrow head; ablated area). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 100 × magnification. Fourth column: magnified (× 300) H&E staining of (d) esophagus showing epithelial karyolysis (thin arrow) and some pyknotic nuclear changes in the submucosa (thick arrow), (i) stomach showing a fragmented nucleus, karyorrhexis (thin arrow) and pyknotic nucleus (thick arrow), and (n) duodenum presenting karyolysis (thin arrow) in the form of nucleus and some pyknotic nucleus (thick arrow) with glandular atrophy (*). Fifth column: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay of (e) esophagus, (j) stomach, and (o) duodenum. H&E: 100 × magnification.

After 24 h, all whitish changes in the esophageal ablation area disappeared, and the electroporated mucosa showed a pattern of epithelial peeling (Fig. 5b). In contrast, the erythematous rim and edematous mucosal changes in the stomach disappeared. Only slight erosion and erythema remained (Fig. 5g). Similar to in the stomach, there was no significant difference between the ablated area and normal mucosa, except for the rectangular-shaped erythema (Fig. 5l).

Histopathology and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay

Interestingly, the application of 1500 V in the esophagus induced partial separation of the squamous epithelium and karyolysis in the ablated epithelium. Inflammatory cells infiltrated the separated mucosa (Fig. 5c), while pyknosis was observed in the LP (Fig. 5d). The basal layer and basement membrane of the electroporated lesion were destroyed. On the other hand, the mucosal layer of the stomach ablated at 1000 V exhibited the loss of glandular epithelial cells with no histological damage at the submucosal layer, clear demarcation between the ablation margins (Fig. 5h) and shrunken, fragmented nucleus (Fig. 5i). The duodenum ablated at 1000 V showed glandular atrophy and inflammatory cells in the LP with a preserved SM layer (Fig. 5m,n).

The esophageal stratified epithelium was terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)–positive. The pyknotic nuclei in the LP and MM as well as the epithelial cytoplasm showing karyolysis were strongly stained (Fig. 5e). Likewise, the nucleus of the ablated mucosa in the stomach and duodenum was TUNEL-positive with the presence of pyknosis and karyorrhexis (Fig. 5j,o).

Discussion

In our two consecutive experiments, we successfully demonstrated that in vivo IRE ablation of the upper GI tract was both feasible and effective. While phase 1 of our study demonstrated adverse effects such as perforation and bleeding after the application of high electrical intensity, phase 2 showed that the electroporation could be accomplished safely if optimized energy was administered.

Our study results have several important clinical implications. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are widely accepted for treating gastric epithelial dysplasia. Nevertheless, there has been considerable debate regarding the best treatment and consistent application of ESD with risk of bleeding and perforation to the low grade dysplasia, which has a risk of cancer transformation less than 10%15,16. Thus, if some small neoplastic lesions are appropriately selected, we postulate that the therapeutic effect of IRE can be expected and maximized. However, IRE cannot completely replace the ESD technique in the stomach. Because the risk of metastasis and recurrence is high in cases of early gastric cancer that are larger than 2 cm or accompanied by ulceration, preferentially applying IRE is considered difficult17.

Before argon plasma coagulation (APC) was applied to the digestive tract as an adjunctive ablation therapy for GI endoscopy, several experimental investigations were conducted on the effect of APC on depth according to gas flow or power range for safety18,19. Since then, APC has clinically confirmed the safety and effectiveness of EGC treatment in cases in which it is difficult to apply endoscopic mucosal resection20. A recent study reported that APC can be applied as its complication rate is lower than that of ESD in low-grade dysplasia lesions less than 2 cm and showed cost-effectiveness21. Therefore, it would be beneficial if an appropriate lesion could be selected with the adequate IRE parameters that are safe for the GI tract.

Recent advances in the IRE technique have provided an opportunity to improve the treatment and management of advanced malignancy. Therefore, IRE can also be attempted as a palliative treatment for obstructive lesions caused by locally advanced tumors that cannot be surgically resected22,23. Additionally, the unique IRE characteristics compared to those of coagulation therapy such as APC and RFA preserve organ structures such as nerves and vessels in the non-thermal area, which can reduce patient complications and maintain function, thereby improving quality of life24,25. Therefore, we believe that this new ablation technique paves the way for a new minimally invasive endoscopic treatment for GI malignancies, suggesting its potential clinical application for the treatment of GI neoplasms.

There are currently two standard ablative methods for the GI tract: RFA and APC. In RFA, heat is dissipated from the tissues around the vessels (diameter > 3 mm) due to blood flow, thus inducing the heat sink effect and increasing recurrence rates26. In contrast, short electrical pulses during IRE circumvent the heat sink effect while selectively preserving vital structures such as vessels, nerves, and ducts27. Thus, IRE is gaining attention as a therapeutic alternative to pre-existing ablation. To date, limited preliminary IRE studies have focused on the hollow viscus of the GI tract: one of the esophagus28, two of the stomach29,30, two of the small bowel31,32, one of the colon33, and one of the rectum34.

We observed that the electroporated depth differed among tissue types, even under the same electrical intensity, as reported in previous RFA studies35. Our experimental results showed that the esophagus required a higher energy intensity than the stomach or duodenum for the identical layer to be damaged. According to impedance data, the relatively small damage induced in the esophagus is interpreted as its average resistance being lower than that of the stomach and duodenum, decreasing the electrical conductivity and current flow.

Another finding was that the damage depth was shallower in the duodenum than in the stomach after the application of the same voltage, which is probably attributable to the wider electrode area and longer electrode interval distance inducing energy dispersion. The stronger the intensity of the electrical energy applied, the deeper the tissue damage in the same organ. According to Ohm’s law, the greater the amount of current flowing through the tissue, the stronger the electrical energy in tissues with the same impedance36.

Theoretically, IRE uses non-thermal energy, but secondary Joule heating also occurs above a certain energy threshold. We confirmed here that hemorrhaging occurred in the SM layer during ablation at 2000 V/cm in the stomach. According to a previous IRE study on vessels, a voltage of 115 V (3800 V/cm), pulse length of 100 µs, frequency of 10 Hz, and total of 10 pulses were set as the maximal conditions that did not induce thermal energy production, at a 3-mm carotid artery in the rat37. Therefore, it was assumed that thermal damage occurred beyond the referred maximal conditions because the vessel of the porcine submucosa is smaller than 1 mm38.

According to recent IRE heat generation studies, although the initial pulses of IRE are non-thermal, the temperature increases as the number of delivered pulses increases39,40. As a result, tissue resistance decreases and electrical current increases as the temperature increases during the IRE procedure. The preceding result is consistent with that of a study that reported increased electrical conductivity during IRE40,41. Studies have demonstrated that the increase in conductivity was caused by increased heat and cellular permeability as the delivered energy increased.

The present catheter-induced IRE investigation showed perforations in the esophagus and duodenum. In contrast, previous IRE studies performed on the biliary tract and ureter did not show perforations42,43. Our opposite results might have been attributable to the small electrode area (6.7 mm2) and electrical over-flowing current in the tissues between electrodes and thus thermal injury due to Joule heating. The current density of 1.13 A/mm2 (Joule heat) for the applied voltage of 2500 V in our study was approximately 3.3 times that of the other study42.) Converted to Joule heating, the electrical energy we applied to the esophagus (3.5 J) and duodenum (9.8 J) might have been sufficient to perforate the tissues. This originated from a geometrical electrode difference, while the thermal damage resulted from excessive current density.

Therapeutic endoscopists will be interested in the destruction of neoplastic lesions in the mucosal layer. Since the submucosa is responsible for the regeneration of vessels, nerves, and tissues, previous RFA studies set the criteria for the appropriate ablative energy based on histology confirming the absence of damage to the submucosa44. Accordingly, 714.3–952.4 V/cm in the esophagus, 1000–1500 V/cm in the stomach, and 476.2–714.3 V/cm in the duodenum could be considered suitable electrical intensities to target intramucosal lesions with minimal damage to the submucosa.

This study has several limitations, one of which is that the ablation was performed in normal tissues. Tumor cells and tissues have different structures and are known to be more vulnerable to heat and electrical environments45. Additionally, the junctions of tumor cells are leaky and have a lower impedance than those of normal cells46,47. Therefore, the damaged tissue depth, damaged area, and required electrical energy for ablation of a specific layer may differ in tumor environments, and it can be predicted that tumor tissue ablation would be attempted at a lower electrical field than normal tissue ablation. Second, the number of animals per group was reduced to three because the primary goal was to examine IRE feasibility and safety under various conditions. Although the number of experiments was small to reveal statistical significance regarding measured depth and area, there was no difficulty in confirming the tendency because of the accuracy and precision revealed in the scatter plot. Third, we assumed that the energy supplied from the generator would be entirely transformed into tissue damage in this study. However, there may be a difference between the energy supplied from the generator and the energy actually applied to the tissue. This is because energy loss occurs through heat generation due to tissue impedance during electroporation or due to improper contact between the tissue and electrodes. Therefore, to reduce energy loss, it may be more accurate to measure the actual current flowing in the tissue and compare it with the damage.

In conclusion, endoscopic IRE in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum was feasible, effective, and safe. Our research demonstrated that endoscopic IRE could be a new ablation therapy and option for upper GI tract neoplasms. However, further histological assessments of IRE, including ablated width, depth, and adverse events, should be preceded by appropriate electrical parameters before its clinical application.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Korea University College of Medicine (nos. KOREA-2019-0146, KOREA-2021-0017) and conducted in accordance with the relevant animal guidelines. All experimental procedures and data acquisition, interpretation, and analysis regarding live animals were also performed following the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Study design

The study consisted of two consecutive phases. Phase 1 comprised an experiment to determine the detrimental IRE energy levels for the GI tract. The esophagus and duodenum were sequentially ablated at 3-cm intervals from the esophagogastric junction and pylorus, respectively, and the stomach was electroporated in the antrum. The selection of 1500 V as the initial baseline and upscaling at 500-V intervals were chosen based on previous studies42,48.

The appropriate energy of IRE to ablate the superficial layer were investigated in phase 2. The selected voltage was 500 V less than the undesirable voltage selected in phase 1, and the electrical voltage was gradually lowered in 500-V decrements until the intensity that electroporates the mucosal layer was identified.

Experimental animal model of IRE

To prepare the endoscopic IRE animal model, eight female YLD pigs (12 wk, 40 ± 2 kg; XP-bio Inc, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were acclimated to the animal facility (one pig/cage, 50% relative humidity, 23 °C temperature, 12-h light/dark cycle) for 7 days and fed lab hog chow no. 38075 (Cargill Agri Purina Inc, Gyeonggi-do, Korea).

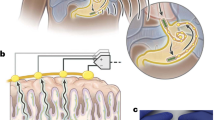

Endoscopic IRE procedure

On the day of the experiment, the pigs were subjected to general anesthesia (induction: azaperone 2–8 mg/kg, xylazine 1–3 mg/kg, alfaxalone 2–6 mg/kg, atropine 0.5 mg/kg; maintenance: 2% isoflurane) with additional drugs (enrofloxacin 5 mg/kg, ketoprofen 3 mg/kg) and an endotracheal tube (6.5 Fr, Henan Tuoren Medical Device Co., Henan, China) was inserted. Following intubation, a 25-cm-long overtube (Guardus®, US Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio, USA) was inserted into the esophagus, and endoscopy (GIF-Q260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was performed through the overtube. The duodenum, stomach, and esophagus were sequentially ablated using the IRE catheter (Fig. 1).

IRE-associated equipment: IRE catheters and pulse generator

We prepared two types of catheters designed for IRE: the needle-type catheter (EPO-E1; The Standard Co. Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea), which was made with NiTi alloy wire for the stomach (Fig. 2a), and the basket-type catheter (EPO-G2; The Standard Co. Ltd.) for the esophagus and duodenum, which had three wheels, two of which consisted of rectangular electrodes (Fig. 2b). They all were capable of approaching the area to be ablated through a channel of the endoscopy. The pulse generator used in the IRE procedure was a BTX Gemini X2 (BTX®, Holliston, USA), which produced an electrical monopolar pulse with a maximum voltage of 3 kV (Fig. 2c). The impedance between the two electrodes was measured before applying electrical energy to the targeted area. To evaluate the current over the tissues, a current probe (TCPA300; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) connected to an oscilloscope (TDA3044B; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA) was clipped to an electrical wire from the pulse generator.

Simulated electrical field intensity of IRE

The electrical field distribution was acquired by calculating Laplace’s equation:

where \(\nabla\) is the gradient operator and \(\phi\) is the electric potential (volt). The boundary conditions were \(\phi \left(0\right)=0 \,{\rm and}\, \phi ({\phi }_{0})={V}_{0}\). The space between the tissue and air and between the catheter and air was considered insulated. The electrical field produced by the needle-type (Fig. 2d) and basket-type catheters (Fig. 2e) was simulated before the experiment using Epocode™ (The Standard Co. Ltd.), which was developed by OpenFOAM (Opensource Field Operation And Manipulation), an open-source computational fluid analysis-oriented software.

Histologic analysis and immunochemistry

Endoscopy confirmed the absence of bleeding or perforation in the lesions at 24 h post-ablation and then pigs were sacrificed. After the electroporated tissues were fixed in 10% formalin solution for 24 h. Next, the fixed tissues were mounted in paraffin and sliced into 3-µm-thick sections and analyzed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. An additional TUNEL assay (ApopTag® Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit, S7100, Millipore, Gaithersberg, MD, USA) was performed to assess tissue apoptosis. After fixation, the presence of brown stained cells was considered positive TUNEL assay findings.

Image analysis of electroporated surface area and ablation depth

The ablation area was measured using Image J software (version 1.8; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Adverse events were defined as extensive submucosal hemorrhage, muscularis propria damage, or perforation. Ablation depth was recorded as the deepest histological damaged layer. H&E- and TUNEL-stained tissue specimen slides were analyzed using a slide scanner (Leica SCN400; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and an image viewer (Leica SCN400 Image Viewer; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The scatter plots of damaged area and depth were represented using GraphPad PRISM® (version 5.1; GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). Non-parametric continuous and ordinal variables are expressed as median and interquartile range using SPSS® (version 24.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, N.Y., USA). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare depth and area by electrical intensity. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All relevant data are presented in the manuscript.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Peery, A. F. et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 156, 254-272.e211. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063 (2019).

Inoue, M. & Tsugane, S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad. Med. J. 81, 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330 (2005).

Ronellenfitsch, U. et al. Preoperative chemo(radio)therapy versus primary surgery for gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: Systematic review with meta-analysis combining individual patient and aggregate data. Eur. J. Cancer. 49, 3149–3158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.05.029 (2013).

Terashima, M. et al. Randomized phase III trial of gastrectomy with or without neoadjuvant S-1 plus cisplatin for type 4 or large type 3 gastric cancer, the short-term safety and surgical results: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG0501). Gastric Cancer 22, 1044–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-019-00941-z (2019).

Nagaraja, V., Eslick, G. D. & Cox, M. R. Endoscopic stenting versus operative gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 5, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.016 (2014).

Ahmed, M., Brace, C. L., Lee, F. T. Jr. & Goldberg, S. N. Principles of and advances in percutaneous ablation. Radiology 258, 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10081634 (2011).

Weaver, J. C. Electroporation of cells and tissues. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 28, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/27.842820 (2000).

Weaver, J. C. Electroporation: A general phenomenon for manipulating cells and tissues. J. Cell. Biochem. 51, 426–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.2400510407 (1993).

Patterson, E. J., Scudamore, C. H., Owen, D. A., Nagy, A. G. & Buczkowski, A. K. Radiofrequency ablation of porcine liver in vivo: Effects of blood flow and treatment time on lesion size. e. 227, 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199804000-00018 (1998).

Davalos, R. V., Mir, I. L. & Rubinsky, B. Tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 33, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-005-8981-8 (2005).

Martin, R. C. 2nd., McFarland, K., Ellis, S. & Velanovich, V. Irreversible electroporation therapy in the management of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 215, 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.021 (2012).

Valerio, M. et al. New and established technology in focal ablation of the prostate: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 71, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.044 (2017).

Pech, M. et al. Irreversible electroporation of renal cell carcinoma: A first-in-man phase I clinical study. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 34, 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-010-9964-1 (2011).

Rugge, M. et al. The long term outcome of gastric non-invasive neoplasia. Gut 52, 1111–1116. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.8.1111 (2003).

Yamada, H., Ikegami, M., Shimoda, T., Takagi, N. & Maruyama, M. Long-term follow-up study of gastric adenoma/dysplasia. Endoscopy 36, 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-814330 (2004).

Japanese Gastric Cancer Group. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018. Gastric Cancer 24, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y (2021).

Johanns, W., Luis, W., Janssen, J., Kahl, S. & Greiner, L. Argon plasma coagulation (APC) in gastroenterology: Experimental and clinical experiences. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-199706000-00006 (1997).

Watson, J. P., Bennett, M. K., Griffin, S. M. & Matthewson, K. The tissue effect of argon plasma coagulation on esophageal and gastric mucosa. Gastrointest. Endosc. 52, 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1067/mge.2000.108412 (2000).

Sagawa, T. et al. Argon plasma coagulation for successful treatment of early gastric cancer with intramucosal invasion. Gut 52, 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.3.334 (2003).

Back, M. K. et al. Analysis of factors associated with local recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric epithelial dysplasia: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 20, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01293-0 (2020).

Martin, R. C., Philips, P., Ellis, S., Hayes, D. & Bagla, S. Irreversible electroporation of unresectable soft tissue tumors with vascular invasion: Effective palliation. BMC Cancer 14, 540. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-540 (2014).

Maor, E., Ivorra, A., Leor, J. & Rubinsky, B. The effect of irreversible electroporation on blood vessels. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 6, 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/153303460700600407 (2007).

Field, W., Rostas, J. W. & Martin, R. C. G. Quality of life assessment for patients undergoing irreversible electroporation (IRE) for treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC). Am. J. Surg. 218, 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.03.020 (2019).

Blazevski, A. et al. Oncological and quality-of-life outcomes following focal irreversible electroporation as primary treatment for localised prostate cancer: A biopsy-monitored prospective cohort. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 3, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euo.2019.04.008 (2020).

Lu, D. S. et al. Influence of large peritumoral vessels on outcome of radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors. J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 14, 1267–1274. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.rvi.0000092666.72261.6b (2003).

Chen, X. Electric ablation with irreversible electroporation (IRE) in vital hepatic structures and follow-up investigation. Sci. Rep. 5, 16233. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16233 (2015).

Neven, K. et al. Acute and long-term effects of full-power electroporation ablation directly on the porcine esophagus. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.116.004672 (2017).

Lee, J. M. et al. Characterization of irreversible electroporation on the stomach: A feasibility study in rats. Sci. Rep. 9, 9094. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45659-1 (2019).

Ren, F. et al. Safety and efficacy of magnetic anchoring electrode-assisted irreversible electroporation for gastric tissue ablation. Surg. Endosc. 34, 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06800-3 (2020).

Phillips, M. A., Narayan, R., Padath, T. & Rubinsky, B. Irreversible electroporation on the small intestine. Br. J. Cancer. 106, 490–495. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.582 (2012).

Phillips, M. The effect of small intestine heterogeneity on irreversible electroporation treatment planning. J. Biomech. Eng. 136, 2. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4027815 (2014).

Luo, X. et al. The effects of irreversible electroporation on the colon in a porcine model. PLoS ONE 11, e0167275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167275 (2016).

Schoellnast, H. et al. Irreversible electroporation adjacent to the rectum: Evaluation of pathological effects in a pig model. Cardiovasc. Interven. Radiol. 36, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-012-0393-1 (2013).

Trunzo, J. A. et al. A feasibility and dosimetric evaluation of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for human colonic and rectal epithelium in a treat and resect trial. Surg. Endoscop. 25, 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1199-3 (2011).

Barkagan, M. et al. Effect of baseline impedance on ablation lesion dimensions: a multimodality concept validation from physics to clinical experience. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 11, e006690. https://doi.org/10.1161/circep.118.006690 (2018).

Maor, E., Ivorra, A., Leor, J. & Rubinsky, B. The effect of irreversible electroporation on blood vessels. Tech. Cancer Res. Treat. 6, 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/153303460700600407 (2007).

Schmidt, C. et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy reliably detects sepsis-related and treatment-associated changes in intestinal mucosal microcirculation. Br. J. Anesthesia. 111, 996–1003. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aet219 (2013).

Davalos, R. V., Bhonsle, S. & Neal, R. E. 2nd. Implications and considerations of thermal effects when applying irreversible electroporation tissue ablation therapy. Prostate 75, 1114–1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.22986 (2015).

van den Bos, W. et al. Thermal energy during irreversible electroporation and the influence of different ablation parameters. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 27, 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2015.10.020 (2016).

Ruarus, A. H. et al. Conductivity rise during irreversible electroporation: True permeabilization or heat?. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 41, 1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-018-1971-7 (2018).

Srimathveeravalli, G. et al. Feasibility of catheter-directed intraluminal irreversible electroporation of porcine ureter and acute outcomes in response to increasing energy delivery. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 26, 1059–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2015.01.020 (2015).

Ueshima, E. et al. Transmural ablation of the normal porcine common bile duct with catheter-directed irreversible electroporation is feasible and does not affect duct patency. Gastrointest. Endosc. 87(300), e1-300.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.05.004 (2018).

Ganz, R. A. et al. Complete ablation of esophageal epithelium with a balloon-based bipolar electrode: A phased evaluation in the porcine and in the human esophagus. Gastrointest. Endoscopy. 60, 1002–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02220-5 (2004).

Nikfarjam, M., Muralidharan, V. & Christophi, C. Mechanisms of focal heat destruction of liver tumors. J. Surg. Res. 127, 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2005.02.009 (2005).

Jones, D. M., Smallwood, R. H., Hose, D. R., Brown, B. H. & Walker, D. C. Modelling of epithelial tissue impedance measured using three different designs of probe. Physiol. Meas. 24, 605–623. https://doi.org/10.1088/0967-3334/24/2/369 (2003).

Keshtkar, A., Salehnia, Z., Somi, M. H. & Eftekharsadat, A. T. Some early results related to electrical impedance of normal and abnormal gastric tissue. Phys. Med. 28, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2011.01.002 (2012).

Guo, Y. et al. Irreversible electroporation in the liver: contrast-enhanced inversion-recovery MR imaging approaches to differentiate reversibly electroporated penumbra from irreversibly electroporated ablation zones. Radiology 258, 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10100645 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: HI14C3477), a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (Grant number: 2020R1A2C4002621), and a grant from Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea (Grant number: K2010001). The funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or preparation of the final report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J.J. and H.S.C. wrote the main manuscript text. H.S.C., H.J.J., and B.K. conceptualized the experiment. H.S.C. and B.K. acquired the funding. H.J.J., H.B.K., and J.M.L. collected the data. B.K., Y.S.S., J.H.K., S.Y.Y., and E.S.K managed the data. E.J.B., K.W.L., and S.H.K prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1. B.K., H.S.L., Y.T.J., and H.J.C. edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, H.J., Choi, H.S., Keum, B. et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of endoscopic irreversible electroporation for the upper gastrointestinal tract: an experimental animal study. Sci Rep 11, 15353 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94583-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94583-w