Abstract

An understanding of the extent to which target audiences consider different nutrition-related messages to be effective could assist campaign developers design more persuasive communications. Accordingly, this study sought to develop and assess the utility of the Perceived Effectiveness of Nutrition Messages Scale (PENMS). A longitudinal online survey was completed by Australian adults (n = 5,014 at Time 1 and 2,880 at Time 2). At T1, respondents saw one of two messages promoting healthy eating. They were then administered the PENMS, and asked how likely they were to engage in the behaviour specified in the message. Respondents completed the PENMS again at T2. An exploratory factor analysis was performed on PENMS scores and measures of reliability and validity obtained. Two factors were identified: ‘effects perceptions’ (Factor 1) and ‘message perceptions’ (Factor 2). Internal consistency of scores was 0.82 for Factor 1 and 0.70 for Factor 2. Test re-test reliability was 0.76 and 0.69 for Factors 1 and 2, respectively. Scores on both factors were moderately correlated with behavioural intentions. The favourable results for PENMS scores suggest the scale may be a useful tool for assessing the extent to which target audiences consider different nutrition-related messages to be effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global dietary patterns are neither healthy nor sustainable. In an analysis of the global dietary database, vegetable intake was found to be 40% below the recommendations made by the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems, fruit intake was found to be 60% below recommendations, and wholegrain intake 61% below recommendations1. By contrast, consumption of red and processed meat was 377% above recommended guidelines1. In Australia, the context of the present study, just 9% consume the recommended number of vegetable servings per day, 45% the recommend number of servings of fruit, and 72% the recommended amount of wholegrains2,3. Given the health benefits associated with consumption of plant-based foods, increasing intake is considered a public health priority4,5. It is also important for the sustainability of the planet, with plant-based foods causing the least damage to the environment6.

Health communication campaigns have the potential to produce favourable changes in health-related behaviours, including those relating to diet and nutrition7. However, messages about nutrition have been described as “bountiful in number, sometimes dull, and often confusing”8, limiting their effectiveness. Given persuasive health communications are those that attract attention, are easy to understand, and encourage changes in attitudes and behaviours8, there is considerable opportunity to improve the messages being disseminated by nutrition educators.

Perceived message effectiveness has been used in a variety of domains to assess target audiences’ assessments of the likely potential for messages to change attitudes and behaviour9,10,11. It has been found to be a valid indicator of actual message effectiveness12,13, which is promising due to the need to identify the likely effectiveness of messages before allocating scarce resources to the production and implementation of health communication campaigns14.

Measures of perceived message effectiveness typically comprise items assessing (i) message perceptions and (ii) effects perceptions9. The former relate to the target audience’s perceptions of the message itself; for example, whether they perceive it to be believable or easy to understand. The latter relate to the target audience’s perceptions of the likely effects of a message on people’s attitudes or behaviour. Previous research conducted in the area of alcohol control suggests that items assessing message perceptions may be less valid predictors of actual effectiveness than those assessing effects perceptions15, with measures of the former considered necessary but not sufficient9. For example, Noar et al.9 note that considering a message to be believable or interesting contributes to, but does not directly equate to, message effectiveness.

Although an understanding of the extent to which target audiences consider different nutrition-related messages to be effective could assist campaign developers design more persuasive messages, relevant measures only appear to have been developed in the areas of tobacco and alcohol control13,15. To facilitate rigorous assessments of the potential effectiveness of nutrition-focused messages in a manner consistent with approaches used in other health fields12,13,16, this study sought to examine the utility of a perceived message effectiveness measure developed in the context of promoting a healthy diet–the Perceived Effectiveness of Nutrition Messages Scale (PENMS).

Method

Sample and procedure

As part of a larger project investigating the lifestyle behaviours of Australian adults (blinded for review17), an ISO-accredited web panel provider (Pureprofile) recruited 5,014 respondents aged 18–70 years to participate in the present study. This sample size was chosen to ensure a sufficient number of respondents remained in the sample after attrition (an attrition rate of 50% was expected; see below for details regarding the observed attrition). Quotas were applied to ensure the sample was representative of the Australian population in terms of gender and socio-economic status. Once quotas for certain demographic groups were filled, potential respondents belonging to the same demographic group were excluded from participation to maintain sample representativeness. Ethics approval was obtained from Curtin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2018-0096) and all respondents provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Respondents completed an online survey at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2: three weeks after T1). The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The sample was broadly representative of the national population in terms of age, gender, and socioeconomic status. An attrition rate of 43% was observed, with 2,880 respondents remaining in the sample at T2. There were no significant differences in attrition according to gender or socioeconomic status. A significant difference was observed for age, with those who remained in the sample significantly older than those who dropped out (44.28 vs 39.80 years; p < 0.001).

Scale development

As perceived message effectiveness has been extensively applied in the area of tobacco control, measures from this field were sourced to inform development of the PENMS13,16,18. Experts in nutrition and health communication fields (e.g., dietetics, social marketing, and behavioural psychology) reviewed these measures and selected items that had demonstrated ability to predict intentions and behaviours, as determined by previous research12,13,16,18. Consistent with the recommendations outlined in (i) the World Health Organization’s strategic communications framework for effective communications report19 and (ii) Noar et al.’s9 conceptualisation and systematic review of perceived message effectiveness, the selected items assessed a variety of persuasive constructs relating to both message and effect perceptions (e.g., believability, motivation to act). To ensure the developed scale was not overly burdensome to complete, we did not use multiple different items to assess the same persuasive construct. Instead, we chose those that had been found in prior work to be the most valid and reliable indicators of the construct being assessed9,12, 13,16,18.

The selected items were then adapted to ensure they referred to the behaviour being assessed (i.e., healthy diet). The final scale featured the text “Please indicate the extent to which you agree/disagree that this healthy diet message…”, followed by a series of six prompts: “makes me stop and think about my diet”, “makes me feel concerned about my diet”, “motivates me to improve my diet”, “is personally relevant”, “is easy to understand”, and “is believable”. Responses to items were made on a scale that ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The number of items chosen (n = 6) and the overall brevity of the scale is consistent with prior work conducted in the tobacco control space13 and serves to minimise response burden, especially when the scale is used in surveys that seek to measure multiple variables.

Measures

At T1, respondents were randomly assigned to view one of the following two messages promoting healthy eating: ‘Include fruit or vegetables in every meal’ or ‘Eat a diet of mainly plant foods’. The messages, presented in the online supplementary material (Figure S1), were developed by experts in nutrition and health communication and reflect the need to increase Australians’ consumption of fruit, vegetables, and wholegrains4,5. After exposure, respondents were administered the PENMS. They were then asked to indicate how likely they were over the next three weeks to engage in the behaviour specified in the message to which they were exposed (1 = Very unlikely to 5 = Very likely). At T2, respondents viewed the same message to which they had been assigned at T1 and completed the PENMS a second time.

Statistical analyses

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with direct oblimin rotation was performed on the scores from the PENMS using the data collected from those assessed at T1 (n = 5,014). EFAs were also conducted at the individual message level, with these results presented in the online supplementary material. Internal consistency of scores was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. As a test of criterion validity, correlation analyses were conducted to assess the relationships between each of the PENMS factors and respondents’ intentions to enact the behaviour promoted in the message to which they were exposed. Correlation analyses were also conducted assessing the relationship between each of the items on the PENMS.

Test re-test reliability was assessed using data from those who provided information at both time points (n = 2,880). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between T1 and T2 scores on each of the PENMS factors were calculated using two-way mixed effects models (type = absolute agreement)20. An ICC < 0.5 indicates poor reliability, values between 0.50 and 0.75 moderate reliability, values between 0.75 and 0.90 good reliability, and > 0.90 excellent reliability20. SPSS v29 was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and inter-item correlations. Initial analyses indicated the data were acceptable for factor analysis (Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ2(15) = 11,013.16, p < 0.001; Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index = 0.83). Two factors were found to underlie the PENMS, with Factor 1 accounting for 54% of the variance in the data and Factor 2 accounting for a further 17%. Factor 1 comprised four items primarily related to perceptions of effects (e.g., “this message makes me stop and think about my diet”; factor loadings: 0.46–0.76). Factor 2 comprised two items primarily related to message perceptions (e.g., “this message is easy to understand”; factor loadings: 0.69–0.78). Table 2 presents factor loadings. The item relating to personal relevance appeared to load onto both factors, although it was below the threshold of 0.40 for Factor 2 (Factor 1: 0.46; Factor 2: 0.37)21.

Internal consistency and test re-test reliability

The McDonald’s omega associated with scores on the items comprising Factor 1 was 0.82. As Factor 2 comprised just two items, McDonald’s omega could not be calculated. Accordingly, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated and found to be 0.70. The McDonald’s omega associated with scores on the full scale was 0.83. These coefficients suggest good internal consistency for scores on Factor 1 and the full scale, and acceptable internal consistency for scores on Factor 2.

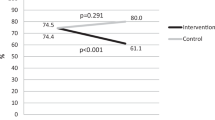

The ICC between Factor 1 T1 and T2 scores was 0.76 (95% CI 0.74, 0.78) indicating good test re-test reliability, while the ICC between Factor 2 T1 and T2 scores was 0.69 (95% CI 0.67, 0.71), indicating moderate reliability. The ICC for scores on the full scale was 0.77 (95% CI 0.75, 0.79).

Validity

Scores on both factors and the full scale demonstrated positive, moderate correlations with T1 enactment intentions (Factor 1: r = 0.40; Factor 2: r = 0.41; Full scale: r = 0.45; all p-values < 0.001), indicating good criterion validity. Correlations relating to each item individually are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

The present study aimed to develop and psychometrically evaluate a measure of perceived message effectiveness (PENMS) for messages promoting increased consumption of plant foods. Scale development was informed by work conducted in the tobacco control space and comprehensive systematic reviews of the literature on perceived message effectiveness12,13,16,18.

As per previous research15, two factors (Factor 1: ‘effects perceptions’ and Factor 2: ‘message perceptions’) were found to underlie the PENMS. These factors were largely distinct, with only the personal relevance item loading onto both factors. It is notable that this item loaded more strongly on the factor relating to effects perceptions (Factor 1) than the factor relating to message perceptions (Factor 2). This is in contrast with prior work by Noar et al.9 that suggested personal relevance is a construct that aligns with message perceptions. We recommend further work be conducted that interrogates this item further.

In terms of reliability, internal consistency of scores on the overall scale and Factor 1 was good, and internal consistency of scores on Factor 2 was acceptable. Test re-test reliability and criterion validity on the overall scale and each of the factors were good. Of interest is the finding that the correlations between enactment intentions and both message perceptions and effects perceptions were almost identical (message perceptions: r = 0.40; effects perceptions: r = 0.41). An understanding of the utility of both types of perceptions was raised by Noar et al.9 as a key direction for work in the area of perceived message effectiveness. The present study provides evidence to suggest that both perception types may be useful correlates of effectiveness.

The favourable results for scores on the PENMS suggest the scale may be a useful tool for assessing the extent to which target audiences consider nutrition-related messages to be effective. Given the abundant and increasing amount of nutrition information and misinformation being shared by competing sources, especially on social media22,23, the development of a scale that assesses nutrition messages for likely effectiveness assists with ensuring only the most impactful are disseminated. In addition, the PENMS offers those working in the nutrition space with a means of assessing the potential effectiveness of nutrition interventions in a manner that is consistent with message testing conducted in the tobacco12,13, 16 and alcohol control fields15.

This study had several limitations. First, a confirmatory factor analysis could not be conducted as Factor 2 comprised only two items and such a model is prone to estimation problems24. Second, we did not include measures of actual behaviour change and only assessed behavioural intentions. There was thus a lack of data to enable assessment of predictive validity. We recommend future research include measures of actual behaviour change to provide an indication of predictive validity. Third, an attrition rate of 43% was observed between T1 and T2. While this rate was smaller than anticipated, a difference was observed between completers and non-completers, with completers significantly older than non-completers. Finally, a web panel provider was used to recruit survey respondents, which would have excluded individuals without computer/Internet access or skills. Future research could consider using alternative recruitment methods. Study strengths include the large sample size and a sample that was broadly representative of Australia’s population in terms of age, gender, and socioeconomic status.

In conclusion, the PENMS provides nutrition educators with a validated tool to identify the likely effectiveness of messages promoting a healthy diet. The ability of the PENMS to assess people’s perceptions of the persuasiveness of nutrition messages can assist in optimising message outcomes and health campaign expenditure.

Data availability

To protect the privacy of individuals that participated in the study, the data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly. Please contact the corresponding author to request data from this study.

References

Development Initiatives, Global nutrition report: The state of global nutrition. (Bristol, Development Initiatives Poverty Research Ltd. 2021).

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Dietary behaviour 2020–2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/dietary-behaviour/latest-release (2022).

Galea, L. M. et al. Whole grain intake of Australians estimated from a cross-sectional analysis of dietary intake data from the 2011–13 Australian health survey. Pub. Health Nutr. 20(12), 2166–2172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017001082 (2017).

Aune, D. et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46(3), 1029–1056. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw319 (2017).

Aune, D. et al. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 353, i2716. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2716 (2016).

Nelson, M. E. et al. Alignment of healthy dietary patterns and environmental sustainability: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 7(6), 1005–1025. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.012567 (2016).

Wakefield, M. A., Loken, B. & Hornik, R. C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet Oncol. 376(9748), 1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 (2010).

Wilson, B. J. Designing media messages about health and nutrition: What strategies are most effective?. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 39(2), S13–S19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2006.09.001 (2007).

Noar, S. M. et al. Perceived message effectiveness measures in tobacco education campaigns: A systematic review. Commun. Methods Meas. 12(4), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1483017 (2018).

Baig, S. A. et al. UNC perceived message effectiveness: Validation of a brief scale. Ann. Behav. Med. 52(8), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay080 (2019).

Dillard, J. P., Weber, K. M. & Vail, R. G. The relationship between the perceived and actual effectiveness of persuasive messages: A meta-analysis with implications for formative campaign research. J. Commun. 57(4), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00360.x (2007).

Noar, S. M. et al. Does perceived message effectiveness predict the actual effectiveness of tobacco education messages? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 35(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1547675 (2020).

Brennan, E. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of antismoking television advertisements: Do audience ratings of perceived effectiveness predict changes in quitting intentions and smoking behaviours?. Tob. Control 23(5), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050949 (2014).

Yzer, M., LoRusso, S. & Nagler, R. H. On the conceptual ambiguity surrounding perceived message effectiveness. Health Commun. 30(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.974131 (2015).

Jongenelis, M. I. et al. Development and validation of the alcohol message perceived effectiveness scale. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28141-x (2023).

Wakefield, M. et al. Smokers’ responses to television advertisements about the serious harms of tobacco use: Pre-testing results from 10 low-to middle-income countries. Tob. Control 22(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050171 (2013).

Pettigrew, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of combinations of ‘why to reduce’and ‘how to reduce’alcohol harm-reduction communications. Addict. Behav. 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107004 (2021).

Stewart, H. S. et al. Potential effectiveness of specific anti-smoking mass media advertisements among Australian indigenous smokers. Health Educ. Res. 26(6), 961–975. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr065 (2011).

World Health Organization. Strategic Communications Framework for Effective Communications (WHO, 2017).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 (2016).

Stevens, J. P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2009).

Ruxton, C. H., Ruani, M. A. & Evans, C. E. Promoting and disseminating consistent and effective nutrition messages: Challenges and opportunities. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 82(3), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665123000022 (2023).

Diekman, C., Ryan, C. D. & Oliver, T. L. Misinformation and disinformation in food science and nutrition: Impact on practice. J. Nutr. Health Aging 153(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2022.10.001 (2023).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling 4th edn. (Guildford Press, 2016).

Funding

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council project grants APP1142620 and APP1129002. The National Health and Medical Research Council had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Funding acquisition. LB: Writing—review & editing. SP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors have approved this final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jongenelis, M.I., Booth, L. & Pettigrew, S. Development and validation of the Perceived Effectiveness of Nutrition Messages Scale. Sci Rep 14, 16870 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67751-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67751-x