Abstract

Several international epidemiological studies have established a link between obesity and upper gastrointestinal cancer (UGC), but Chinese evidence is limited. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of obesity, especially central obesity, while investigating its association with upper gastrointestinal diseases in the high-risk population of Yangzhong, a typical high-risk area for UGC in southeastern China. We conducted a cross-sectional study from November 2017 to June 2021 involving 6736 residents aged 40–69. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess independent factors influencing overweight/obesity and central obesity. We also analyzed the relationship between obesity and upper gastrointestinal diseases using multinomial logistic regression. The prevalence of overweight, obesity, waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR)-central obesity were 40.6%, 12.0%, 49.9%, 79.4%, and 63.7%, respectively. Gender, age, smoking, tea consumption, sufficient vegetable, pickled food, spicy food, eating speed, physical activity, family history of cancer, and family history of common chronic disease were associated with overweight /obesity and central obesity. Besides, education and missing teeth were only associated with central obesity. General and central obesity were positively associated with UGC, while general obesity was negatively associated with UGC precancerous diseases. There were no significant associations between obesity and UGC precancerous lesions. Subgroup analyses showed that general and central obesity was positively associated with gastric cancer but not significantly associated with esophageal cancer. Obesity is negatively and positively associated with gastric and esophageal precancerous diseases, respectively. In conclusion, general and central obesity were at high levels in the target population in this study. Most included factors influenced overweight/obesity and central obesity simultaneously. Policymakers should urgently develop individualized measures to reduce local obesity levels according to obesity characteristics. Besides, obesity increases the risk of UGC but decreases the risk of UGC precancerous diseases, especially in the stomach. The effect of obesity on the precancerous diseases of the gastric and esophagus appears to be the opposite. No significant association between obesity and upper gastrointestinal precancerous lesions was found in the study. This finding still needs to be validated in cohort studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity and overweight have become public health issues globally and are related to many chronic diseases, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes1,2. It is shown that from 1975 to 2016, the age-standardized worldwide prevalence of obesity (body mass index, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) increased from 3 to 12% in men and 7% to 16% in women. This change has increased obese adults by over 6 times, from 100 to 671 million3. From 1995 to 2016, an enormous absolute increase in obesity occurred among men (from 9 to 30%) in high-income countries in the West and women (from 12 to 35%) in Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa3. As in the world, overweight and obesity have become serious concerns in China. In 2018, among Chinese adults aged 18–69, an estimated 85 million people were obese (48 million for men and 37 million for women), 3 times the number of obesity in 20044. The age-standardized prevalence of obesity increased from 3.1 to 8.1%, and BMI increased faster in men than in women4. Most strikingly, during this period, rural men's BMI levels have always been lower than urban ones. However, the BMI level of urban and rural women changed in 2010 (the increased levels of BMI among rural women began to exceed that of urban ones). By 2018, rural women's BMI levels have surpassed urban women's4. Furthermore, a British study of over 112 million adults reported that the average BMI of women in rural areas increased by 2.09 kg/m2, and that of men increased by 2.10 kg/m2 from 1985 to 2017 worldwide. In contrast, women's average BMI in urban areas increased by 1.35 kg/m2, and men's increased by 1.59 kg/m2. This led to a higher BMI for rural women than their urban counterparts in regions such as East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania in 2017, especially in low- and middle-income countries5. Overall, significant increases in the BMI of rural residents contributed to a 60% increase in average BMI for women and a 57% increase in average BMI for men globally5. These findings challenge the current mainstream view of urban life and urbanization as the main driving force of the global obesity epidemic, reminding us that the obesity problem of rural residents is also worthy of attention.

Obesity has been confirmed to be associated with the risk of at least 13 cancers, including esophageal cancers (EC) and gastric cancers (GC)6. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 141 studies found that increased BMI was associated with a higher risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) both in men (RR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.33–1.74) and women (RR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.31–1.74)7. Another study found that EAC risk was greater with BMI (RR per 5 kg/m2 = 1.47, 95% CI 1.34–1.61)8. Besides, some studies reported an indisputable positive relationship between central obesity and EAC. For instance, the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition showed that waist circumference (WC) was strongly associated with EAC risk9. Singh et al.10 found that central adiposity increased the EAC risk (aOR = 2.51, 95% CI 1.54–4.06). In contrast, some previous studies have revealed that higher BMI and central obesity were associated with a lower risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), the most common form of EC in China8,11,12,13.

Overall, physical measurement indicators are positively correlated with GC risk. However, there is evidence that the association may differ when GC is divided into cardia gastric (CGC) and non-cardia gastric cancer (NCGC). Specifically, the risk of CGC increases with increasing BMI (RR per 5 kg/m2 = 1.23, 95% CI 1.07–1.40)14 and WC (RR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.19–2.54)15. The evidence for NCGC is conflicting, with studies suggesting that BMI and central obesity were not associated with it9,16 and a few reporting that central obesity was associated with its increased risk15.

Although the association between obesity and upper gastrointestinal cancer (UGC, EC/GC) is almost proven internationally, evidence from the Chinese-specific population and studies on the relationship between obesity and upper gastrointestinal diseases, especially for precancerous lesions/diseases, are limited. As we all know, the precancerous stage of UGC has important practical implications for the cost and prognosis of clinical interventions. Meanwhile, we have explored the current status of overweight and obesity in people at high risk of UGC in the previous literature17. However, we failed to include central obesity and multiple types of confounding variables due to study design limitations. Therefore, our study first focused on the prevalence of obesity, especially central obesity, among residents aged 40–69 (defined as the high-risk groups for UGC in China) from a high-risk area for UGC and then explored the relationship between upper gastrointestinal diseases and obesity. We used the secondary data from The National Cohort of Esophageal Cancer-Prospective Cohort Study of Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions based on High-Risk Population (NCEC-HRP) and rural Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Early Diagnosis and Treatment Project (UGCEDTP) implemented in Yangzhong to conduct this study.

Methods

Study design and population

Yangzhong is located in Jiangsu Province of southeast China, which has high morbidity and mortality of EC and GC18,19, and it has been listed as a project site in the UGCEDTP since 200618,19. The project mainly uses endoscopy and pathological diagnosis to find early UGC and its precancerous lesions among high-risk groups as much as possible and promote the tertiary prevention of UGC18,19. The project site has also been included in the NCEC-HRP in recent years20. Both programs target local people aged 40–69 years in regions with a high incidence of UGC. Additional details of the UGCEDTP and NCEC-HRP can be found elsewhere18,19,20. Therefore, Yangzhong was chosen for this continuity study because of its good experience in cancer screening and research projects, stable screening staff, and high incidence rate of UGC.

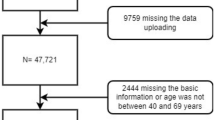

The sampling method for this study was multistage stratified cluster sampling19,21. The sample was taken in six health areas of Yangzhong (Baqiao, Youfang, Sanmao, Xinba, Xinglong, and Xilaiqiao). In the first stage, regions were stratified by income and geographic location. Three regions (townships/subdistricts) were randomly selected. In the second stage, five administration villages or communities were randomly selected from each site. In the third stage, each resident group was selected from the chosen sites. In the fourth stage, all residents (individuals with local household registration) aged 40–69 years were invited unless they were unwilling to participate or had a history of UGC/mental disorder or contraindication for endoscopy18,19,20. All participants were given informed consent. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The academic and ethics committee of Yangzhong People's Hospital approved the study (approval number: 202152). Participants with complete data on general information (demographic and socio-economic information), health-related characteristics, physical examination, and screening results from November 2017 to June 2021 were included in our study. Finally, 6736 high-risk (40–69 years) residents were included in our analysis, with 163 participants excluded as missing information on socio-demographic characteristics (age, marital status and education, etc.), height, weight, WC, and screening outcomes (Fig. 1).

Study procedure and data collection

Well-trained epidemiological investigators, physicians, and pathologists from the People's Hospital of Yangzhong conducted the cross-sectional study, including the questionnaire survey, anthropometrical measurements, endoscopy, and pathological diagnosis guided by the study protocol for NCEC-HRP and Technical Programme for the UGCEDTP20,22.

Firstly, a face-to-face questionnaire survey for eligible respondents is based on a structured and validated questionnaire (authorized by the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences) derived from the NCEC-HRP, with the whole process taking about 20–30 min. Survey respondents were asked about socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, marital status, residence, education, and average annual household income). Health-related characteristics included smoking (frequency, type, amount of cigarettes in a typical day, duration), drinking (frequency, type, amount of alcohol consumed in a typical day, and duration), tea consumption (frequency, type, amount of tea consumed in a typical day, duration and preference for tea temperature), and vegetable intake (frequency and consumption in a typical day), fruit intake (frequency and consumption in a typical day), scalding (frequency in the past year), pickled (frequency in the past year), leftovers (frequency in the past year), fried (frequency in the past year), irregular (frequency in the past year), and spicy diet (frequency in the past year), eating too fast (Yes/No), indoor air pollution (frequency of cooking and type of cooking fuel), missing teeth (Yes/No), diet taste (salty, medium, light), family history of cancer (Yes/No) and common chronic disease (Yes/No), were also collected. In addition, occupational and leisure-time physical activity (type and duration of physical activity per week) were recorded.

Secondly, physical measurements, including height, weight, hip circumference (HC), and WC, were done following the standard methods. The measurement methods of height and weight can be found in the literature mentioned above17,18. We measured the widest part of the pelvis as the HC, with accuracy to the nearest 0.1 cm23. WC was measured at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last rib and the top of the hip bone (umbilicus level) at the expiration's end, with accuracy to the nearest 0.1 cm23,24. The measurement was conducted by two experienced staff.

Thirdly, the endoscopic centre's clinical staff conducted an endoscopy and biopsy of suspicious lesions/high-incidence sites biopsy. Biopsy tissue at the gastric antrum was placed in a rapid urease assay reagent to determine whether Helicobacter pylori infection was present19. Pathologists then performed pathological diagnoses of the biopsied tissue. The examination procedure followed the technical program and the expert consensus recommendation on UGC20,22,25. Participants would be included in the follow-up process if diagnosed with precancerous lesions/diseases. If early-stage or advanced cancer is detected, targeted interventions would be made to interrupt the cancer process. Corresponding follow-up and treatment methods can also be found in the technical program20,22.

Definition of variables

The formulae for BMI can be found in the previous literature17,18. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) = WC (cm)/HC (cm), and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) = WC (cm)/height (cm)23,26. Underweight/Normal weight, overweight, and obesity were defined as BMI < 24.0 kg/m2, 24.0 ≤ BMI < 28.0 kg/m2, and BMI ≥ 28.0 kg/m2, respectively, according to the Chinese classifications27. The WC cut-off points of the International Diabetes Federation for central obesity (WC ≥ 90.0 cm for men, WC ≥ 80.0 cm for women) were also used28. The WHR cut-off point for central obesity was 0.90 for men and 0.85 for women, respectively23. The cut-off point of WHtR for central obesity was 0.5 for both sexes29.

Smoking included current smokers (who have smoked cigarettes in the past 28 days and the consumption of cigarettes was up to 100 in their lifetime), ever smokers (who have not consumed cigarettes in the past 28 days, and the consumption of cigarettes was up to 100 in their lifetime) and never smokers (who have consumed the cigarettes less than 100 in their lifetime)19,21. Drinking included current drinkers (who have drunk alcohol at least once per week in the past year) and never-drinkers19,21. Tea drinking included current tea drinkers (who have drunk tea at least once per week in the past year) and never-tea drinkers. Adequate vegetable and fruit consumption was defined as consuming at least 300 g and 200 g, respectively, per day in the past year, according to the recommendations of the Chinese Dietary Guidelines30. The scalding diet was categorized into "Yes" (including self-reported consumption of scalding tea/food at least once per week in the past year ) and "No"31,32. Pickled, leftovers, fried, irregular and spicy diets were defined as the self-reported frequency of at least once a week in the past year18,19. We defined self-reported having the experience of cooking and using coal or wood as the main cooking fuel as indoor air pollution33. The occupational and leisure-time physical activity were merged and grouped into low, moderate, or high, whose definitions, specific consolidation, and grouping methods can be found in the previous studies1,34. Precancerous diseases in this study included reflux oesophagitis, gastric polyps, gastric ulcers, and intestinal metaplasia/atrophic gastritis diagnosed by endoscopy or pathology. Precancerous lesions included low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia diagnosed by pathology. Cancers are defined as EC and GC diagnosed by pathology.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0. As continuous data did not pass the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (P < 0.001), they were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Frequencies and percentages were used to express categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U and χ2 tests were applied to evaluate the differentials in the socio-demographic and health-related characteristics among different genders and obesity. Besides, differences in screening results for the population with different obesity status were assessed. Multivariate logistic regression was adopted to explore the independent factors influencing overweight/obesity and central obesity with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated. Besides, multinomial logistic regression was applied to explore the relationship between upper gastrointestinal diseases [others (reference), precancerous diseases, precancerous lesions and cancers)] and different types of obesity, with AOR and 95%CI estimated. There was no collinearity between all variables (VIF < 2); therefore, all variables were considered in the multivariate model. Only factors with P < 0.05 in the final multivariate regression analysis were considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic information of the study population

Table 1 shows the gender-stratified characteristics of the study sample. A total of 6736 participants (2947 men and 3789 women) [mean age, 56.0 (IQR, 25th–75th percentiles: 51.0–63.0) years] were analyzed in this study. Most participants were female (56.3%), married (93.6%), rural residents (78.0%), and nearly half had an education level of junior middle school (47.2%). More participants had an average annual household income of ≥ 110,000 Chinese Yuan (CNY) (34.9%). Differences in all presented characteristics were statistically significant for males and females (all P < 0.05), except for age, family history of cancer, and common chronic disease (P > 0.05). Besides, the median BMI was 24.2 (IQR: 22.2–26.1) kg/m2 [24.4 (IQR: 22.3–26.5) kg/m2 for men and 24.0 (IQR: 22.0–26.0) kg/m2 for women, P < 0.001], and the median WC was 84.0 (IQR: 78.0–89.0) cm [86.0 (IQR: 81.0–92.0) cm for men and 82.0 (IQR: 77.0–87.0) cm for women, P < 0.001)] among the participants. The median WHR was 0.9 (IQR: 0.9–1.0) [0.9 (IQR: 0.9–1.0) for men and women, P < 0.001], and the median value of WHtR was 0.5 (IQR: 0.5–0.5) [0.5 (IQR: 0.5–0.5) for men and 0.5 (IQR:0.5–0.6) for women, P < 0.001].

Prevalence of general and central obesity

Table 2 presents the prevalence of general and central obesity across different socio-demographic characteristics. The prevalence of overweight, obesity, WC-central obesity, WHR-central obesity, and WHtR-central obesity was 40.6%, 12.0%, 49.9%, 79.4%, and 63.7%, respectively. The prevalence of overweight and obesity was higher among males than females, while central obesity was higher among females than males. The prevalence of central obesity increases progressively with age, with obesity decreasing. Besides, married participants had higher rates of overweight and obesity but lower rates of central obesity. Urban residents had higher rates of overweight, obesity, and WC-central obesity but lower rates of WHR/WHtR-central obesity. There is an upward trend in overweight and obesity rates and a downward trend in central obesity as educational attainment and average annual household income increase. There were statistically significant differences in the distribution of general obesity and central obesity among participants with different socio-demographic characteristics, except for the distribution of WC-central obesity among people with different average annual household income, WHR-central obesity among people with different marital status and WHtR-central obesity among people with different residence had no significant difference (P > 0.05).

Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal diseases

Table 3 shows the distribution characteristics of upper gastrointestinal diseases under different obesity indicators. The prevalence of precancerous diseases, lesions, cancers, and others in the upper gastrointestinal tract was 42.0%, 8.5%, 0.7%, and 48.8%, respectively. The prevalence of precancerous diseases and lesions was lower in the overweight/obese population than in the under/normal-weight population, but the prevalence of cancers was higher (P < 0.05). The prevalence of precancerous diseases, lesions, and cancers was higher in the WHR centrally obese population than in their counterparts (P < 0.05). In addition, the distribution of upper gastrointestinal diseases in the WC centrally obese and WHtR centrally obese populations, although different, was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Distributional features of gastric and esophageal diseases can be seen in the supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Associated factors for overweight/obesity and central obesity

Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the influencing factors of overweight/obesity or central obesity (Table 4). After adjusting for all confounding variables, the result of the multivariate regression analysis showed that females (OR = 0.752, 95% CI 0.640–0.884), current smokers (OR = 0.761, 95% CI 0.642–0.902), and participants with moderate physical activity (OR = 0.854, 95% CI 0.767–0.950) had lower odds of overweight/obesity. There was strong evidence that participants aged 50–59 years (OR = 1.155, 95% CI 1.018–1.309), drinking tea (OR = 1.241, 95% CI 1.052–1.465), intake of sufficient vegetable (OR = 1.166, 95% CI 1.050–1.295), pickled food (OR = 1.247, 95% CI 1.127–1.380), spicy food (OR = 1.191, 95% CI 1.021–1.389), eating too fast (OR = 1.590, 95% CI 1.416–1.785) and having family history of cancer (OR = 1.110, 95% CI 1.003–1.230) or common chronic disease (OR = 1.321, 95% CI 1.194–1.462) were more likely to be overweight/obesity.

The result of the multivariate regression analysis showed that younger age, higher education level, and participants with moderate physical activity were protective factors for central obesity while drinking tea, intake of pickled food, and eating too fast were risk factors of central obesity (P < 0.05). Besides, females (OR = 3.083, 95% CI 2.611–3.640), ever-smokers (OR = 1.310, 95% CI 1.013–1.694), participants consuming spicy food (OR = 1.187, 95% CI 1.016–1.387) and having a family history of cancer (OR = 1.131, 95% CI 1.018–1.256) or common chronic disease (OR = 1.171, 95% CI 1.055–1.299) had higher odds of WC-central obesity. Current smoking decreased the risk of WHR/WHtR-central obesity. Intake of sufficient vegetable (OR = 1.240, 95% CI 1.090–1.409) and missing teeth (OR = 1.168, 95% CI 1.023–1.334) were risk factors for WHR-central obesity. Participants with a family history of cancer (OR = 1.134, 95% CI 1.020–1.260) or common chronic disease (OR = 1.166, 95% CI 1.050–1.294) were more likely to be WHtR-central obesity.

Association of upper gastrointestinal diseases with obesity indicators

Table 5 presents the multivariate logistic regression analysis of determinants related to obesity of upper gastrointestinal diseases. After fully adjusting, the result reported that being overweight or obese (OR = 0.889, 95% CI 0.801–0.987) was less likely to have upper gastrointestinal precancerous diseases but more likely to have UGC (OR = 2.103, 95% CI 1.078–4.101), which was similar with WHtR-central obesity (OR = 2.233, 95% CI 1.056–4.718). WC- and WHR-central obesity were not significantly associated with upper gastrointestinal diseases (P > 0.05). Subgroup analyses showed that those who were overweight or obese (OR = 0.855, 95% CI 0.772–0.946) and those who were centrally obese in WC (OR = 0.892, 95% CI 0.804–0.990) were less likely to have gastric precancerous diseases but more likely to have GC. Participants with WHtR-central obesity were more likely to have GC (OR = 2.997, 95% CI 1.124–7.995). Overweight and obesity (OR = 1.638, 95% CI 1.105–2.429), WC-central obesity (OR = 1.956, 95% CI 1.329–2.879), and WHtR-central obesity (OR = 2.281, 95% CI 1.459–3.566) were more likely to have esophageal precancerous diseases.

We reran the multinomial logistic regression model as a sensitivity analysis after combining cancers with precancerous lesions, and the association between obesity and precancerous diseases did not change substantially (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

The present study focused on describing the prevalence of obesity, especially central obesity, among high-risk residents in a typical high-risk area of UGC, southeastern China. Furthermore, we explored the determinants of obesity and the possible relationship between obesity and upper gastrointestinal disease. The study showed that nearly 50% of the participants were overweight/obese or WC-centrally obese, and most participants were WHR/WHtR -centrally obese. After controlling for the possible confounders, different factors were associated with overweight/obesity and central obesity. Overweight/obesity was significantly associated with precancerous diseases and cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. WHtR-central obesity was associated with UGC. Subgroup analyses showed that being overweight or obese and WC-central obesity were significantly associated with gastric precancerous diseases and GC. WHtR-central obesity was associated with GC. Being overweight/obese and WC/WHtR-central obesity was only associated with esophageal precancerous diseases. This study did not find a significant correlation between general obesity/central obesity and any precancerous lesions.

With socio-economic development and continuous lifestyle changes, the obesity level of Chinese adults is increasing4,35. China Chronic Disease Risk Factor Surveillance (CCDRFS) data demonstrated that the prevalence of general obesity (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2) among Chinese adults (≥ 18 years) from 2013 to 2014 was 14% (males, 14.0% vs. females, 14.1%), and the prevalence of WC-central obesity (90 cm for men; 85 cm for women) was 31.5% (males, 30.7% vs. females, 32.4%)36. Moreover, since 2004, the prevalence of general and central obesity has increased by about 90% and more than 50%, respectively36. It was estimated by Li et al. that the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and WC-central obesity between 2007 and 2017 among Chinese adults increased from 20.3 to 20.8%, 31.9 to 37.2% and 25.9 to 35.4%, respectively37. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in this study was 40.6% and 12.0%, respectively, which were higher than the rates of 25.8% and 7.9%, respectively, found by Hu et al.38 and 26.97% and 7.13%, respectively, reported in Hunan Province, China recently39. In addition, the prevalence of overweight in our study was higher than that reported in previous studies, while obesity was similar to or lower than that in the same studies40,41. Nevertheless, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is more in line with our previous findings in the same context17. The prevalence of WC-central obesity in this study was 49.9%, much higher than that reported in different settings36,37,42. Similar findings were found in the prevalence of central obesity determined by WHR and WHtR43,44,45. Numerous studies regarding the prevalence of obesity and central obesity have been conducted in China. Due to the different survey subjects, definitions, and data sources, the findings varied. In brief, we found that more than half of the population in our study were overweight or obese, nearly half were WC-central obesity, and most were WHR/WHtR-central obesity. This high prevalence of different types of obesity indicates that obesity is a common occurrence in the high-risk population of UGC and deserves the attention of policymakers. Meanwhile, we also found that the prevalence of overweight in the survey population was dominant, giving a window of weight improvement. Therefore, it is urgent to adopt intervention strategies to slow or reverse the obesity trend of those people.

We found some independent factors that influence obesity. More specifically, gender, age, current smoking, consumption of adequate vegetable, and pickled food were independent factors related to being overweight or obese, consistent with our previous finding17. In addition, we found tea drinking, spicy food, eating too fast, moderate physical activity, and family history of cancer and common chronic disease were influencing factors for being overweight/obese and centrally obese. Green tea consumption is usually considered to improve obesity levels. Numerous studies have shown that tea and its bioactive polyphenolic constituent, caffeine, can prevent and treat some metabolic disorders, including obesity46,47,48. Tea may also prevent obesity by decreasing appetite, reducing food consumption, reducing digestive system absorption, and altering fat metabolism49. This inconsistent result may be partly attributable to the fact that the type of tea consumption was not categorized in this study but also to the fact that residents may increase the frequency of tea consumption after perceiving obesity. Consistent with previous studies50,51, we found that spicy food increased the risk of general and central obesity. Many previous studies have confirmed that eating too fast is one of the risk factors for obesity52,53,54. On the one hand, eating too fast may cause us to eat more food due to a lack of satiety, thus increasing the potential for overnutrition53. It may also cause elevated blood sugar and insulin resistance, culminating in overeating54. On the other hand, a decrease in chewing leads to a reduction in the activation of histamine neurons in the brain, whose function includes suppressing appetite and accelerating lipolysis of visceral fat cells54. Physical activity is known to be a protective factor for obesity55,56,57. Similarly, among participants with moderate physical activity, we found that the risk of overweight/obesity and central obesity was about 0.8–0.9 times that of participants with low physical activity. Compared with participants without a family history of cancer and common chronic disease, we found that individuals with a family history were more likely to be obese, consistent with other findings58,59. This result may be achieved by increasing the risk of high-risk chronic diseases and poor lifestyles60,61,62.

We also found some heterogeneity in the independent influences on central and general obesity. Firstly, the risk of overweight/obesity was higher in males than in females, while the females tended to be central obese, consistent with previous studies24,38,41. However, other studies have found that females tend to be overweight/obese2,29. One possible explanation for the difference might be rapid changes in female hormones, the onset of menopause, and decreased metabolic exertion and physical activity levels24,38,41,63. Secondly, we observed that the risk of being overweight/obese decreased with ageing. However, a positive association between central obesity and ageing was observed, consistent with previous studies1,24. The changes in subcutaneous fat, lean mass, visceral fat accumulation1,24,38,64,65, level of physical activity, and physical health may partly be the reason for the difference63. We also observed that a high education level was a protective factor for central obesity, which may benefit from relatively adequate health awareness and literacy. However, in some other studies, their relationship was positive, especially among men24,66. We found that ever-smokers were more likely to be centrally obese, as in the study by Wang et al.24. Hence, residents who quit smoking should combine appropriate education and supportive treatment to reduce obesity to avoid weight gain becoming a barrier to quitting67. Our study found a positive association between missing teeth and central obesity. Still, we did not observe a meaningful association in general obesity, which aligns with the study by Singh et al.68. Previous studies have shown that missing teeth may affect chewing function and fruit and fibre intake, thus adversely affecting weight management69.

This study found that being overweight/obese and WHtR-central obese were more likely to get UGC. Subgroup analysis showed that in addition to the same association between the above obesity types and GC, WC-central obesity was also positively associated with GC, consistent with previous studies' results70,71. Several previous studies have found a positive association between overweight and obesity and GC, particularly among men and non-Asian populations72,73,74. Relevant mechanisms include excessive fat accumulation, especially abdominal obesity leading to insulin resistance, high leptin, low adiponectin, altered ghrelin, and abnormally increased blood levels of insulin-like growth factor74,75. In addition, gastroesophageal reflux diseases, strongly associated with GC, appear more prevalent in obese individuals74,75,76. However, we did not find any significant association between any obesity type and EC, which is inconsistent with the results of previous related studies8,9,10,11,77,78. This may be related to the small number of EC cases in this study (n = 13). Besides, it is well known that there is heterogeneity in the association of ESCC and EAC with obesity, and combining them in this study due to the small number of cases may have obscured some of the associations. We found no significant association between obesity indicators and any precancerous lesions, including gastric and esophagus sites. Earlier studies in a local high-risk area found an inverse association between general/central obesity and ESCC and its precancerous lesions33,78. One explanation for this finding may be the differences in study design, origin and characteristics of the participants, and the type and number of confounding factors included. We found that being overweight or obese was a protective factor for upper gastrointestinal precancerous diseases. Subgroup analysis showed that both overweight/obesity and WC-central obesity reduced the risk of gastric precancerous diseases. A recent study by Bae et al. found that overweight is a protective factor for GC in adult Asians, which is consistent with the results of this study79. The reason for this phenomenon may be related to the fact that overweight or obese patients have a greater experience of consultation and care80, which undoubtedly increases their likelihood of detecting their precancerous diseases. It may also be associated with altered digestive or eating habits in people with precancerous conditions, which can lead to weight loss81. We found that overweight and obesity, as well as WC/WHtR-central obesity, increase the risk of precancerous esophageal diseases (reflux esophagitis). This finding was confirmed by the studies of Chang et al. and Friedenberg et al.82,83.

Although this study is the first to investigate a high-risk population in a high-risk area for UGC to describe the prevalence of different types of obesity and explore the possible association between obesity and upper gastrointestinal diseases through standardized screening data, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the target population was 40–69 years, not representing the whole population. Secondly, participants were recruited in Yangzhong, and the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. Thirdly, the cross-sectional study can describe the status of interested variables at a certain time but cannot determine the causal association between exposure and outcome. Fourth, the small number of cancer cases in this study did not allow for subgroup analyses of different pathological types of cancer. Therefore, further evidence is needed. We will further construct prospective cohort studies based on the NCEC-HRP and UGCEDTP to demonstrate their association among high-risk Chinese populations.

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence of general and central obesity in a high-risk setting of Yangzhong, southeast China. Overweight/obesity and central obesity were significantly associated with gender, age, smoking, tea consumption, sufficient vegetable, pickled food, spicy food, eating speed, physical activity, and family history of cancer and common chronic disease. Education and missing teeth were also significantly correlated with central obesity. These findings can inform the development of weight improvement measures by disease control and prevention departments. Obesity significantly increases the risk of UGC but decreases the risk of precancerous diseases, which mainly apply to the stomach. Obesity is not significantly associated with EC but increases the risk of esophageal precancerous diseases. However, no significant association between precancerous lesions and obesity was observed in this study. More studies are needed to verify the association between obesity indicators and upper gastrointestinal diseases in the Chinese population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Guo, X. et al. An update on overweight and obesity in rural Northeast China: from lifestyle risk factors to cardiometabolic comorbidities. BMC Public Health 14, 1046 (2014).

Omar, S. M., Taha, Z., Hassan, A. A., Al-Wutayd, O. & Adam, I. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and central obesity among adults in the Eastern Sudan. PLoS ONE 15, e0232624 (2020).

Sung, H. et al. Global patterns in excess body weight and the associated cancer burden. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 88–112 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural China: Findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–18. Lancet 398, 53–63 (2021).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature 569, 260–264 (2019).

Avgerinos, K. I., Spyrou, N., Mantzoros, C. S. & Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism 92, 121–135 (2019).

Renehan, A. G., Tyson, M., Egger, M., Heller, R. F. & Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371, 569–578 (2008).

Vingeliene, S. et al. An update of the WCRF/AICR systematic literature review and meta-analysis on dietary and anthropometric factors and esophageal cancer risk. Ann. Oncol. 28, 2409–2419 (2017).

Steffen, A. et al. General and abdominal obesity and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int. J. Cancer 137, 646–657 (2015).

Singh, S. et al. Central adiposity is associated with increased risk of esophageal inflammation, metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 1399-1412.e7 (2013).

Nimptsch, K., Steffen, A. & Pischon, T. Obesity and oesophageal cancer. Recent Res. Cancer Res. 208, 67–80 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Adult height, body mass index change, and body shape change in relation to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk: A population-based case-control study in China. Cancer Med. 8, 5769–5778 (2019).

Sanikini, H. et al. Anthropometry, body fat composition and reproductive factors and risk of oesophageal and gastric cancer by subtype and subsite in the UK Biobank cohort. PLoS One 15, e0240413 (2020).

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and stomach cancer. Available at https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/stomach-cancer-report.pdf (2018).

Murphy, N., Jenab, M. & Gunter, M. J. Adiposity and gastrointestinal cancers: Epidemiology, mechanisms and future directions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 659–670 (2018).

Du, X., Hidayat, K. & Shi, B. M. Abdominal obesity and gastroesophageal cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Biosci. Rep. 37 (2017).

Feng, X. et al. The prevalence and determinant of overweight and obesity among residents aged 40–69 years in high-risk regions for upper gastrointestinal cancer in southeast China. Sci. Rep. 13, 8172 (2023).

Feng, X. et al. Prevalence and coprevalence of modifiable risk factors for upper digestive tract cancer among residents aged 40–69 years in Yangzhong city, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11, e042006 (2021).

Zhu, J. H. et al. Analysis of Helicobacter pylori infection and its association with gastric diseases among a population aged 40–69 years in areas with high incidence of gastric cancer. Chin. J. Cancer Prev. Treat 30, 765–772 (2023) (Chinese).

Chen, R. et al. The national cohort of esophageal cancer-prospective cohort study of esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions based on high-risk population in China (NCEC-HRP): Study protocol. BMJ Open 9, e027360 (2019).

Huang, F. et al. Analysis of the association between types of obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in residents aged 40–69 years. Mod. Prev. Med. 20, 2305–2310 (2023) (Chinese).

Wang, G. Q. & Wei, W. Q. Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Screening and Early Detection and Treatment Technology Programme (2020 Pilot Version) (People's Publishing House, 2020).

Zhang, J., Xu, L., Li, J., Sun, L. & Qin, W. Association between obesity-related anthropometric indices and multimorbidity among older adults in Shandong, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 10, e036664 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Epidemiology of general obesity, abdominal obesity and related risk factors in urban adults from 33 communities of Northeast China: The CHPSNE study. BMC Public Health 12, 967 (2012).

Ma, D. et al. Chinese expert consensus on screening and endoscopic management of early Esophageal Cancer (Beijing, 2014). Gastroenterology 20, 220–240 (2015) (Chinese).

Kromeyer-Hauschild, K., Neuhauser, H., Schaffrath Rosario, A. & Schienkiewitz, A. Abdominal obesity in German adolescents defined by waist-to-height ratio and its association to elevated blood pressure: the KiGGS study. Obes. Facts 6, 165–175 (2013).

Wang, H. & Zhai, F. Programme and policy options for preventing obesity in China. Obes. Rev. 14(Suppl 2), 134–140 (2013).

Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet 366, 1059–1062 (2005).

Alshamiri, M. Q. et al. Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) in predicting coronary artery disease compared to body mass index and waist circumference in a single center from Saudi Arabia. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2020, 4250793 (2020).

Chinese nutrition society. Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents. (People's Publishing House, 2016).

Sheikh, M. et al. Individual and combined effects of environmental risk factors for esophageal cancer based on results from the golestan cohort study. Gastroenterology 156(1416–1427), 32 (2019).

Islami, F. et al. A prospective study of tea drinking temperature and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 146, 18–25 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. A model to identify individuals at high risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precancerous lesions in regions of high prevalence in China. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 1538-1546.e7 (2017).

Hu, G., Tuomilehto, J., Silventoinen, K., Barengo, N. & Jousilahti, P. Joint effects of physical activity, body mass index, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio with the risk of cardiovascular disease among middle-aged Finnish men and women. Eur. Heart J. 25, 2212–2219 (2004).

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Geographic variation in prevalence of adult obesity in China: Results from the 2013–2014 national chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, 291–293 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Changes in the prevalence of obesity and hypertension and demographic risk factor profiles in China over 10 years: Two national cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 15, 100227 (2021).

Hu, L. et al. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, abdominal obesity and obesity-related risk factors in southern China. PLoS One 12, e0183934 (2017).

Hua, J. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among people aged 18 years and over between 2013 and 2018 in Hunan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4048 (2020).

Li, X. Y. et al. Prevalence and characteristic of overweight and obesity among adults in China, 2010. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 46, 683–686 (2012) (Chinese).

Wang, R. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and some associated factors among adult residents of northeast China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6, e010828 (2016).

Du, P. et al. Prevalence of abdominal obesity among Chinese adults in 2011. J. Epidemiol. 27, 282–286 (2017).

Muhammad, T., Boro, B., Kumar, M. & Srivastava, S. Gender differences in the association of obesity-related measures with multi-morbidity among older adults in India: Evidence from LASI, Wave-1. BMC Geriatr. 22, 171 (2022).

Srivastava, S., Joseph K J, V., Dristhi, D. & Muhammad, T. Interaction of physical activity on the association of obesity-related measures with multimorbidity among older adults: A population-based cross-sectional study in India. BMJ Open 11, e050245 (2021).

Cao, L. et al. Effects of body mass index, waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio and their changes on risks of dyslipidemia among Chinese adults: The guizhou population health cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 341 (2021).

Xu, R., Yang, K., Li, S., Dai, M. & Chen, G. Effect of green tea consumption on blood lipids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. J. 19, 48 (2020).

Gamboa-Gómez, C. I. et al. Plants with potential use on obesity and its complications. EXCLI J 14, 809–831 (2015).

Hayat, K., Iqbal, H., Malik, U., Bilal, U. & Mushtaq, S. Tea and its consumption: Benefits and risks. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 55, 939–954 (2015).

Sirotkin, A. V. & Kolesárová, A. The anti-obesity and health-promoting effects of tea and coffee. Physiol. Res. 70, 161–168 (2021).

Wang, M., Huang, W. & Xu, Y. Effects of spicy food consumption on overweight/obesity, hypertension and blood lipids in China: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Nutr. J. 22, 29 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Association of the frequency of spicy food intake and the risk of abdominal obesity in rural Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e028736 (2019).

Zhu, B., Haruyama, Y., Muto, T. & Yamazaki, T. Association between eating speed and metabolic syndrome in a three-year population-based cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 25, 332–336 (2015).

Nagahama, S. et al. Self-reported eating rate and metabolic syndrome in Japanese people: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 4, e005241 (2014).

Wu, N. et al. Analysis of the correlation between eating speed and obesity. Chin. J. Endocrine Metab. 38, 186–189 (2022) (Chinese).

Jakicic, J. M. & Davis, K. K. Obesity and physical activity. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 34, 829–840 (2011).

Oppert, J. M. et al. Exercise training in the management of overweight and obesity in adults: Synthesis of the evidence and recommendations from the European association for the study of obesity physical activity working group. Obes. Rev. 22(Suppl 4), e13273 (2021).

Pojednic, R., D’Arpino, E., Halliday, I. & Bantham, A. The benefits of physical activity for people with obesity, independent of weight loss: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 4981 (2022).

Van der Sande, M. A. et al. Family history: An opportunity for early interventions and improved control of hypertension, obesity and diabetes. Bull. World Health Organ. 79, 321–328 (2001).

Cederberg, H., Stančáková, A., Kuusisto, J., Laakso, M. & Smith, U. Family history of type 2 diabetes increases the risk of both obesity and its complications: Is type 2 diabetes a disease of inappropriate lipid storage. J. Intern. Med. 277, 540–551 (2015).

Valdez, R., Greenlund, K. J., Khoury, M. J. & Yoon, P. W. Is family history a useful tool for detecting children at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? A public health perspective. Pediatrics 120(Suppl 2), S78-86 (2007).

Bostean, G., Crespi, C. M. & McCarthy, W. J. Associations among family history of cancer, cancer screening and lifestyle behaviors: A population-based study. Cancer Causes Control 24, 1491–1503 (2013).

Sá, A. & Peleteiro, B. The effect of chronic disease family history on the adoption of healthier lifestyles. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage 33, e906–e917 (2018).

Zang, J. & Ng, S. W. Age, period and cohort effects on adult physical activity levels from 1991 to 2011 in China. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 13, 40 (2016).

Borkan, G. A. & Norris, A. H. Fat redistribution and the changing body dimensions of the adult male. Hum. Biol. 49, 495–513 (1977).

Cartwright, M. J., Tchkonia, T. & Kirkland, J. L. Aging in adipocytes: Potential impact of inherent, depot-specific mechanisms. Exp. Gerontol. 42, 463–471 (2007).

Ariaratnam, S. et al. Prevalence of obesity and its associated risk factors among the elderly in Malaysia: Findings from The National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2015. PLoS One 15, e0238566 (2020).

Sucharda, P. Smoking and obesity. Vnitr Lek 56, 1053–1057 (2010).

Singh, A. et al. Gender differences in the association between tooth loss and obesity among older adults in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 49, 44 (2015).

Chari, M. & Sabbah, W. The relationships among consumption of fruits, tooth loss and obesity. Community Dent. Health 35, 148–152 (2018).

Ilic, M. & Ilic, I. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 1187–1203 (2022).

Thrift, A. P. & El-Serag, H. B. Burden of gastric cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 534–542 (2020).

Lin, X. J. et al. Body mass index and risk of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 44, 783–791 (2014).

Ji, B. T. et al. Body mass index and the risk of cancers of the gastric cardia and distal stomach in Shanghai China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 6, 481–485 (1997).

Azizi, N. et al. Gastric cancer risk in association with underweight, overweight, and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 15, 2778 (2023).

Li, Q., Zhang, J., Zhou, Y. & Qiao, L. Obesity and gastric cancer. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 17, 2383–2390 (2012).

Kellerman, R. & Kintanar, T. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Prim. Care 44, 561–573 (2017).

Uhlenhopp, D. J., Then, E. O., Sunkara, T. & Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer: Update in global trends, etiology and risk factors. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 13, 1010–1021 (2020).

Lu, P., Gu, J., Zhang, N., Sun, Y. & Wang, J. Risk factors for precancerous lesions of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in high-risk areas of rural China: A population-based screening study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99, e21426 (2020).

Bae, J. M. Body mass index and risk of gastric cancer in Asian adults: A meta-epidemiological meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Cancer Res. Treat 52, 369–373 (2020).

Bottone, F. G. et al. Obese older adults report high satisfaction and positive experiences with care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 220 (2014).

Wei, L. P. et al. Body mass index and the risk of gastric cancer in males: A prospective cohort study. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 40, 1522–1526 (2019).

Chang, P. & Friedenberg, F. Obesity and GERD. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 43, 161–173 (2014).

Friedenberg, F. K., Xanthopoulos, M., Foster, G. D. & Richter, J. E. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 2111–2122 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the residents and staff involved in the present study.

Funding

This study was supported by the China Early Gastrointestinal Cancer Physicians Growing Together Program (Grant NO. GTCZ-2021-JS-32-0001), Zhenjiang City key research and development plan (Grant NO. SH2022051) and 2023 Jiangsu Province Preventive Medicine general Project (Ym2023031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F. drafted the manuscript. X.F., J.H.Z., Z.L.H., and J.Y.Z. contributed to the conception and design of the study. X.F., Q.P.S., S.H.Y. and H.J.Y. conducted data collection and fundamental statistical analysis. X.F., Z.L.H., J.H.Z., J.Y.Z. S.H.Y., Q.P.S. and H.J.Y. discussed the result and agreed on the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, X., Zhu, J., Hua, Z. et al. Prevalence and determinants of obesity and its association with upper gastrointestinal diseases in people aged 40–69 years in Yangzhong, southeast China. Sci Rep 14, 21153 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72313-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72313-2

This article is cited by

-

Coprevalence of modifiable gastric cancer risk factors and gastric health among Chinese high-risk groups

Scientific Reports (2025)