Abstract

This research explored the link between teacher-student relationships and learning engagement, considering perceived social support as a mediator and academic self-efficacy as a moderator. A total of 930 college students completed the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale, Teacher-Student Relationships Questionnaire, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and College Student Learning Engagement Questionnaire. Mediating and moderating effects were investigated using SPSS19.0 and one of its process plugins 3.5. The findings indicated (1) teacher-student relationships positively predicted learning engagement; (2) perceived social support mediated the link between teacher-student relationships and learning engagement; and (3) academic self-efficacy moderated the initial phase of the pathway to the mediating role of perceived social support. Moreover, the mediating effect was more significant at elevated academic self-efficacy levels. Establishing harmonious relationships between teachers and students, nurturing students’ confidence in their academic abilities , and expanding students’ access to social support were essential to boosting the educational involvement of college students. The study findings will help educators enhance college students’ engagement in learning and provide recommendations for educators to conduct educational and teaching activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning issues are prevalent in education globally, and academic burnout significantly affects students’ academic performance, particularly in countries with low and middle incomes. Kaggwa et al. conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis, employing sophisticated methods and diverse databases, and revealed that burnout is experienced by nearly a third of college students from countries with low-to-middle incomes1. For example, in South Korea, more than 30% of college students experience considerable academic stress, resulting in mental anguish and learning burnout. Severe cases include thoughts of suicide and self-injury2. These findings underscore the severity of academic burnout. Thus, it is urgent to focus on methods to mitigate students’ burnout and enhance their intrinsic motivation and active participation in order to advance their academic achievements and continuously improve talent cultivation in colleges and universities. With the ongoing progress in positive psychology research, learning engagement—recognized as a protective factor in enhancing academic performance—has garnered increasing attention from the academic community3. Current studies indicate an inverse correlation between academic burnout and engagement in learning4. Furthermore, enhancing academic engagement may help alleviate symptoms of burnout, thereby promoting academic achievement5. Consequently, understanding the link between academic burnout and learning engagement is vital for creating effective strategies to enhance academic achievement. Learning engagement is a key determinant influencing education quality in higher education institutions and a major forecaster of student achievement and career outcomes6. Self-determination theory7 and social cognitive theory8 (SCT) have offered insights into the processes and determinants of student learning engagement. Although previous research this study proposed has sought to understand how teacher-student relationships affect learning engagement, much remains unknown about the underlying mechanisms. Investigating the link between teacher-student relationships and learning engagement with a focus on academic self-efficacy and perceived social support can provide novel insights and empirical support for understanding and enhancing students’ learning engagement, thereby effectively mitigating the adverse effects of academic burnout. With this as a foundation, this research seeks to explore the complex interactions among teacher-student relationships, perceived social support, academic self-efficacy, and learning engagement, thereby providing theoretical and practical guidance for improving academic achievement and reducing burnout.

Learning engagement

Schaufeli et al. first proposed the concept of learning engagement9. They posit that learning engagement entails an emotional and cognitive state related to learning, reflecting a person’s positive comprehension of the significance of learning and a condition of enthusiasm and immersion in the learning process. Learning engagement comprises three dimensions: dedication, vigor, and absorption. Dedication signifies robust engagement in learning and a complete affirmation of the significance of learning. Vigor involves a willingness to expend energy on learning, showing resilience to fatigue, and manifesting strong tolerance when encountering difficulties. Absorption entails experiencing full pleasure throughout the learning process, perceiving time as passing quickly, and feeling unwilling—from the depths of one’s heart—to detach from the learning state9. Fredricks et al. divided learning engagement into three distinct aspects: cognitive, affective, and behavioral10. Cognitive engagement is a state of high involvement in the cognitive strategies students use and their high involvement in utilizing psychological resources during the learning process. Affective engagement involves expressing various emotional responses during the learning process. Behavioral engagement occurs when individuals are highly involved in academic activities during learning. These three dimensions are interrelated yet independent, with heightened emotional involvement capable of directly influencing an individual’s level of study engagement and concurrently affecting their academic participation through interactions associated with cognitive activities.

Based on the SCT, the learning process results from the interplay between the external objective environment and personal internal elements. The external objective environment influences external behavior through individual internal factors8. Learning engagement results from an individual’s internal regulatory mechanisms and the objective environment. Personal internal factors typically include individual characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and major), academic emotions11, academic performance12, and academic self-efficacy13. The objective environment typically encompasses the school atmosphere14, teacher-student relationships15, social support16, and school belongingness17, among other factors.

Teacher-student relationships and learning engagement

The bond between teacher and student is considered a crucial interpersonal connection within the educational setting. Teacher-student relationships evolve through daily interactions and communication, creating a psychological connection involving cognitive, emotional, and behavioral interactions18. Attachment theory suggests that children’s early experiences interacting with significant people in their life create a stable internal working model. Children develop corresponding response patterns in various contexts based on this model. With age, this working model extends to other attachment relationships, particularly teacher-student relationships18. The attachment expansion theory in teacher-student relationships also emphasizes the critical importance of this relationship in a student’s growth. This theory emphasizes that intimacy and satisfaction within teacher-student relationships positively influence students’ learning engagement19. Therefore, exploring how teacher-student relationships influence learning engagement holds significant theoretical importance.

Teacher-student relationships and learning engagement generally exhibit a significant positive correlation. Numerous studies indicate that active teacher-student relationships are effective in increasing student motivation, academic engagement, and academic achievement. Roorda et al., drawing on 99 studies, employed a meta-analysis to explore the link between the emotional aspects of teacher-student relationships, learning engagement, and academic achievement across preschool and high school students20. The findings indicated a strong correlation between the emotional quality of teacher-student relationships and learning engagement at different school stages. A higher quality of emotional engagement corresponds to stronger learning engagement and vice versa20. Other studies have further validated this point. Fernández-Zabala et al. examined environmental variables associated with school, family, peers, and learning engagement21. They revealed that teacher support had the closest relationship to learning engagement among these environmental factors. Valle et al. analyzed the links among school bullying, teacher-student relationships, and learning engagement and found that teacher-student relationships have a direct positive effect on learning engagement22. Positive relationships with teachers produce higher learning engagements. Conversely, adverse teacher-student relationships lead to reduced engagement22. Teacher-student relationships also represent an emotional connection, and positive connections increase students’ enthusiasm for learning. As teachers garner more positive feedback from students, their enthusiasm for teaching increases. This heightened enthusiasm contributes to more profound teaching content and diverse teaching methods. Students’ receptivity to learning significantly improves, yielding enhanced learning outcomes and fostering a virtuous cycle. By contrast, in an environment with low-quality teacher-student relationships, students’ motivation to learn will decrease, and over time, they may lose confidence in their studies, ultimately diminishing the effectiveness of their learning. Supported by these theories and empirical studies, this study proposed Hypothesis 1: Teacher-student relationships are positively related to learning engagement in college students.

Mediating role of perceived social support

Social support denotes the assistance provided to an individual by those around them to cope with stress23. Social support is commonly categorized as objective and perceived social support. Relatives, acquaintances, and close ones are widely favored sources of social support24. Perceived social support differs from objective social support, as it is subjective: it is perceived and experienced by the individual as being helped by those around them25. Individuals experiencing stress view social support as a safeguarding element. Self-determination theory views motivation as the central element of human health, proposing that satisfying basic needs enhances the actualization of self-functioning. Fulfilling basic needs stimulates individuals’ intrinsic motivation, facilitates self-growth, and fosters individual adaptation26. Ryan and Deci posit that facilitating the shift from extrinsic motivation to higher forms necessitates deliberating the roles of internal motivation, self-regulation, and well-being in fostering or impeding self-motivation and robust psychological growth27. These three social-environmental conditions exert a facilitative influence on fulfilling the three categories of self-need: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Needs of relatedness, or the desire for belonging, involve establishing intimate and secure relationships with others27. Research indicates a strong link between the feeling of being socially supported and desire for belonging28. In the educational setting, students need to develop and sustain connections with others, including teachers, peers, and partners, among which teacher-student relationships are paramount29. When students cultivate harmonious teacher-student relationships and perceive care and support from teachers, it fulfills their need for belonging30. Concurrently, perceived social support within an educational setting can boost student learning enthusiasm, enhance their involvement in learning, and elevate their academic achievements31. A study on social support and math anxiety indicates that increased social support leads to greater learning engagement32.

Using a questionnaire tested on over 900 university students, Feng et al. explored perceived teacher support, students’ information and communication technology self-efficacy, and their participation in online English courses within a mixed learning setting, particularly in a mobile-aided foreign language teaching environment33. The study revealed that students’ information and communication technology self-efficacy positively influenced their online English education, and teachers’ sense of support influenced their learning engagement33. Rautanen et al. conducted a three-wave tracking survey of elementary school students in grades four to six using random intercept cross-lagged panel models over three periods34. The results revealed a reciprocal link between learning engagement and teacher support. Following the self-determination theory and prior empirical research, it can be inferred that teacher-student relationships may influence students’ learning engagement via perceived social support. However, research exploring how perceived social support mediates the link between college students’ teacher-student relationships and learning engagement is limited. Therefore, investigating perceived social support as a mediator between college students’ teacher-student relationships and learning engagement holds substantial innovative potential and can address the shortcomings of existing research.

Therefore, Hypothesis 2 posits that perceived social support mediates teacher-student relationships and college students’ learning engagement.

Moderating role of academic self-efficacy

A mediation effect analysis of perceived social support helps to show how teacher-student relationships influence students’ learning engagement. However, it ignores the conditions under which the relationship influences students’ learning engagement and the different roles that students’ energy and resources play in the teacher-student relationship’s influence on their learning engagement. Academic self-efficacy is a crucial moderating factor that reflects individual variance in resources and energy and warrants focus. Academic self-efficacy denotes an individual’s self-assessment of their ability to accomplish academic activities, signifying a rise in self-efficacy within the realm of learning35. The prevailing view is that academic self-efficacy encompasses two elements: academic ability and academic behavior. The academic community has extensively researched academic self-efficacy, primarily focusing on academic environment variables such as academic performance, pressure, and procrastination36,37,38. Self-efficacy, a crucial element of SCT, represents the assessment of one’s capacity to perform a particular assignment. Bandura classified self-efficacy into efficacy expectations and outcome expectancies39. Based on Bandura’s SCT, individuals’ self-efficacy not only directly influences their behavior and motivation but also indirectly affects behavioral performance by regulating the influence of external factors40. In educational settings, students’ academic self-efficacy can serve as an internal resource and driving force, affecting how they leverage external support resources, particularly social support from teachers.

As significant role models in a student’s schooling environment, teachers have verbal persuasions and rich life experiences that directly or indirectly influence students’ academic self-efficacy development41. In a study involving over 800 graduate students as participants, scholars investigated the interplay among teacher-student relationships, students’ academic procrastination behavior, and academic self-efficacy. The results revealed that academic self-efficacy correlates positively with teacher-student relationships42. Self-determination theory states that individuals’ intrinsic motivation and behavioral performance are contingent not only on external environmental support but also on the fulfillment of psychological needs and levels of self-efficacy. Even with strong teacher-student relationships and strong perceived social support, students lacking sufficient academic self-efficacy may still be unable to fully capitalize on these external resources to enhance their learning engagement. Research indicates a strong link between academic self-efficacy and learning engagement, which may be further enhanced by moderating extrinsic factors such as teacher-student relationships and perceived social support. For instance, Bandura found that students possessing higher academic self-efficacy tend to engage more in learning activities and derive greater benefit from teacher feedback and support35. Academic self-efficacy correlates with students’ positive emotions toward teachers, resulting in their perception of enhanced social support43. Conversely, when students report lower academic self-efficacy, they experience more negative emotions toward teachers, resulting in a perception of reduced social support44. Therefore, academic self-efficacy is a crucial factor influencing both students’ learning engagement and their benefits from teacher-student relationships. When students possess higher academic self-efficacy, they tend to translate teacher support into positive learning motivation, thereby enhancing their engagement in learning. Conversely, low self-efficacy may prevent students from fully utilizing these support resources, leading to insufficient engagement in learning. Based on the above analysis, this study proposed Hypothesis 3: Academic self-efficacy positively moderates perceived social support and teacher-student relationships.

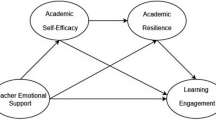

This study constructed a moderated mediation model with teacher-student relationships influencing learning engagement through the mediating role of perceived social support, and academic self-efficacy moderates the first half of the model (as depicted in Fig. 1).

Results

Common method variance test

The Harman one-way test was employed. The findings indicated that the eigenvalues of 10 factors exceeded 1. The initial factor accounted for a fluctuation of 13.09%, falling beneath the critical value of 40%, signifying a lack of significant common method bias.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Correlation analysis was performed for each variable, examining further the associations between teacher-student relationships, academic self-efficacy, perceived social support, and learning engagement (Table 1). A positive association was found, indicating a connection between learning engagement, perceived social support, academic self-efficacy, and teacher-student relationships.

Testing the moderated mediation effect

Independent samples t-tests of the four variables—teacher-student relationships, academic self-efficacy , learning engagement, and perceived social support—revealed significant gender disparity in learning engagement (t = 1.992, df = 928, p < 0.05): female students were significantly more engaged in learning than their male counterparts. Consequently, gender was treated as a control variable, and Model 7—an SPSS macro developed by Hayes—was applied45. Findings revealed that the teacher-student relationship directly forecasts learning engagement. Additionally, incorporating perceived social support as the mediator factor and academic self-efficacy as the moderator factor into the regression equation, it was found that the teacher-student relationships positively predicted perceived social support. Both teacher-student relationships and perceived social support were significant positive predictors of learning engagement. Furthermore, bootstrap 95% CI [0.005, 0.030] regarding the mediating effects of perceptual social support excluded 0. This suggests that perceived social support partially mediates teacher-student relationships and learning engagement. Additionally, the interplay of teacher-student relationships and academic self-efficacy is a significant predictor of perceived social support. This implies that the influence of teacher-student relationships in perceived social support is moderated by academic self-efficacy, as illustrated in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

To elucidate how academic self-efficacy moderates the impact of the teacher-student relationships on perceived social support, simple slope tests were conducted, and simple effect analyses were plotted based on academic self-efficacy values, dividing them into high and low categories (see Fig. 3). The findings showed that teacher-student relationships significantly predicted perceptual social support when academic self-efficacy was low (bsimple = 0.160, 95% CI [0.012, 0.308]; p < 0.05). The positive predictive influence of teacher-student relationships on perceptual social support remained significant and was enhanced when academic self-efficacy was high (bsimple = 0.367, 95% CI [0.192, 0.542]; p < 0.001). As depicted in Table 3, this suggests that academic self-efficacy amplifies the impact of teacher-student relationships on perceived social support.

Discussion

This study, grounded in SCT, explored perceived social support as a mediator linking teacher-student relationships with learning engagement, as well as academic self-efficacy as a moderator of the first part of the model. It also explored how teacher-student relationships in the current educational context influence college students’ learning engagement and the underlying mechanisms of this effect. The findings have theoretical and practical significance, contributing to a deeper understanding of teacher-student relationships, college students’ learning engagement, and promoting students’ learning adaptation.

Active teacher-student relationships represent essential external social support for student learning. This study provided compelling evidence in support of Hypothesis 1, indicating that teacher-student relationships significantly predict college students’ learning engagement. This indicates that students are more inclined to demonstrate heightened participation in learning when they perceive a good relationship with the teacher. This consistency aligns with previous research findings, such as those of Li, who concluded that perceived teacher-student relationships directly impacted learning engagement after investigating the relationship among the perception of teacher-student relationships, growth mindset, learning engagement, and enjoyment of the foreign language for more than 400 English language learners46. The more harmonious the perceived teacher-student relationship is, the greater their learning participation46. The conscientious regulation of learning behaviors, such as adhering to a study plan and abstaining from social media use during study sessions, bolsters students’ intrinsic motivation for learning. However, additional efforts are required to ensure high grades, and how students engage with their learning environment significantly influences their academic success47. A significant antecedent variable that influences learning engagement is the teacher-student relationship, which constitutes a crucial factor affecting students’ interaction with the environment. While augmenting students’ learning engagement, the influence of interaction with the learning environment should be considered. When students perceive a deficiency in learning motivation or encounter study fatigue, beyond seeking positive internal resources, they proactively engage with academic counselors, course instructors, or even psychological counselors to garner supplementary external support and address situations involving inadequate learning participation.

Acting as a protective element, perceived social support contributes to learning engagement. Investigating the connection between perceived social support within teacher-student relationships and learning engagement enhances understanding of the theoretical mechanisms of learning engagement. Findings from this research corroborate Hypothesis 2, which stated that perceived social support mediates the link between teacher-student relationships and learning engagement. This implies that perceived social support provides an important “bridge” connecting teacher-student relationships and learning engagement. Students should fortify their communication with course instructors and counselors for augmented learning participation during routine academic endeavors. Simultaneously, course instructors and counselors should show they are engaged in. Students will likely feel more empowered to participate in their learning when they perceive that their teachers support them.

According to the research results and self-determination theory, A moderated mediation model was constructed to examine the influence of academic self-efficacy. The results demonstrated that academic self-efficacy moderates the initial phase of the mediation effect. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was verified. Teacher-student relationships do not have equal effect sizes on perceived social support, and teacher-student relationships do not have equal effect sizes on perceived social support. The lower level of self-identified academic self-efficacy, the smaller the effect size. Academic self-efficacy can play a moderating role, partly because individuals with robust academic self-efficacy frequently and proactively discuss learning issues with teachers. Teachers are receptive to interacting with students who actively seek guidance. Through positive interactions with each other, students and teachers are also constantly adjusting their learning and teaching methods. Students also perceive greater social support from their teachers. Individuals with robust academic self-efficacy have more positive resources and perceive increased social support. Rahim demonstrated that self-efficacy moderates the link between online teaching skills and student engagement, using self-efficacy as a moderating factor to examine the relationship48.

Moreover, people possessing strong academic self-efficacy have a more positive and optimistic view of their own learning ability and learning behaviors. They exhibit heightened empathy in their interactions with teachers, fostering increased resonance with them. This mutual understanding increases happiness and a perception of social support. Zhou and Yu demonstrated that social support was predictively correlated with e-learning self-efficacy and well-being among college students amidst the COVID-19 pandemic49. They were closely related and interacted with each other. Moderating effects of academic self-efficacy were also supported.

This study offers new insight into the prevention of and intervention in college students’ learning engagement problems, and educators should squarely address the significance of teacher-student relationships in enhancing their learning engagement. Furthermore, by constructing a moderated mediation model, this study clarified the pathway through which teacher-student relationships promote learning engagement. This suggests that educators must prioritize their relationships with students and pay attention to perceived timely social support. Individuals who perceive more social support often have increased academic self-efficacy and a more proactive and engaged approach to learning. Individuals perceiving less social support are assisted in re-experiencing and increasing their re-conceptualization of good teacher-student relationships, employing strategies such as situational reenactment and cognitive adjustment. Additionally, this study verified how academic self-efficacy moderates the link between teacher-student relationships and perceived social support. It inspired educators to work on students’ learning abilities and behaviors to improve their self-efficacy toward academics.

This study has a few shortcomings. First, it employed a cross-sectional design via questionnaire surveys; while it is grounded in relevant theories, direct causal inferences cannot be derived from the research results. In the future, a longitudinal tracking or experimental approach could be used to make causal inferences. Second, this study collected a limited amount of demographic information from participants. Subsequent research endeavors should collect further participant background information, encompassing factors such as family environment, which could be included to provide researchers with a better understanding of the overall condition of the subjects.

In summary, this study enhanced comprehension of how teacher-student relationships affect the academic engagement of college students by developing a moderated mediation model and thoroughly investigating the underlying mechanisms. In particular, teacher-student relationships are a safeguarding element influencing college students’ learning engagement. Perceived social support mediated the link between teacher-student relationships and learning engagement, while academic self-efficacy moderates this mediation model. Consequently, within student learning management, one can directly enhance one’s teacher-student relationships and depend on perceived social support as a connecting factor to boost learning engagement, thus increasing students’ participation rates. The evidence provided by this study suggests that academic self-efficacy strengthens the internal linkage at the stage from the teacher-student relationships to perceived social support. This result further substantiates the need for specialized educational teaching for college students with varied perceptions of teacher-student relationships. While conventional classroom learning is appropriate for every student, it neglects the students’ assessments of their academic task completion capabilities and the unique variances among them. Therefore, it is crucial to recognize the role of academic self-efficacy in shaping students’ engagement in learning. Improving student learning engagement requires not only dependence on the endeavors of educational institutions and families, but also appreciating the inherent resources and abilities of the students. Concerning effectiveness, the self-directed assistance students receive through educational involvement might surpass the aid provided by schools and families.

Methods

Ethical review

The Academic Committee of Huanghuai University approved this study. This study was executed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

Out of 950 questionnaires distributed at universities in Henan Province, China, 930 valid responses were collected, with the recovery rate of 97.9%. Of these, 462 (49.7%) and 468 (50.3%) were from male and female students, respectively. Only 160 (17.2%) participants were the sole child in their family, , and 770 (82.8%) had siblings. Class cadres numbered 204 (21.9%), and 726 (78.1%) were nonclass cadres. Regarding their choice of college major, 622 (66.9%) students made independent selections, 88 (9.5%) followed their parents’ wishes or others’ arrangements, and 220 (23.7%) accepted adjustment arrangements. Regarding residence, 674 (72.5%) were located in rural areas, and 256 (27.5%) in urban areas. Subjects’ ages ranged from 18 to 23 years, with an average age of 18.92 years (SD = 1.118).

Research procedure

Utilizing a cluster random sampling method, trained subject teachers utilized an online questionnaire platform called Wenjuanxing to conduct standardized measurements at the class level. Before the test was administered, the examiner explained the purposed of the survey to the students, clarified any concerns regarding confidentiality, and secured informed consent from every participant. Withdrawal was possible during the testing period, as participation was anonymous and voluntary. Students submitted their answers after checking for accuracy. As an expression of gratitude, the experimenter provided gifts such as pens, umbrellas, and notebooks to the participants.

Measures

Academic self-efficacy scale

This research utilized the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale formulated by Liang50. Comprising 22 items, it evaluates academic ability self-efficacy and academic behavior self-efficacy. The participants responded using a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.868.

Teacher-student relationships questionnaire

Pianta first created the Teacher-Student Relationships Questionnaire, which Qu later revised51,52. The updated survey comprises 23 items, categorized into four dimensions: intimacy, conflict, assistance, and contentment. Scores for the survey ranged from 1, indicating “strongly disagree,” to 5, signifying “fully agree.” The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.837.

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support

Wang developed the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, which encompassed three categories: family support, friend support, and other support53. Comprising 12 elements, the scale utilizes a seven-point scoring method, spanning from “strongly agree ” to “strongly disagree.” Total scores across all items are computed to gauge individuals’ overall perceived level of social support. Elevated scores indicate an increased perception of social support. The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.872.

College student learning engagement questionnaire

The College Student Learning Engagement Questionnaire assesses students’ learning engagement level54. There are 20 items in the questionnaire, including three dimensions: behavioral engagement, cognitive engagement, and emotional engagement. A five-point scale was used. Higher scores indicate higher learning engagement. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the overall College Student Learning Engagement Questionnaire and the three sub-scales (behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement) are 0.918, 0.825, 0.858, and 0.858, respectively. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.883.

Data analysis

Through the application of SPSS 26.0, an analysis of descriptive statistics and independent samples t-tests was conducted to assess undergraduates’ current academic self-efficacy, teacher-student relationships, perceived social support, and learning engagement. The interrelation between these variables was understood using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Furthermore, Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS version 3.5 was employed to conduct a moderated mediation analysis using Model 745. Specifically, this study examined how teacher-student relationships indirectly influence learning engagement through perceived social support as a mediator. Gender was controlled for, and a bootstrap analysis with 5,000 resamples was conducted to calculate the 95% confidence interval for the mediation calculation. Additionally, simple slope analysis was conducted to investigate how academic self-efficacy moderates this process, elucidating how academic self-efficacy moderates the mechanism of teacher-student relationships on perceived social support, which indirectly influences learning engagement.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kaggwa, M. M. et al. Prevalence of burnout among university students in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 16, e0256402 (2021).

Lee, M. & Larson, R. The Korean “examination hell”: Long hours of studying, distress, and depression. J. Youth Adolesc. 29, 249–271 (2000).

Wang, C., Xu, J., Zhang, T. C. & Li, Q. M. Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China’s hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 10–22 (2020).

Jeon, M.-K., Lee, I. & Lee, M.-Y. The multiple mediating effects of grit and learning agility on academic burnout and learning engagement among Korean university students: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. 1, 2710–2724 (2022).

Liu, H., Zhong, Y., Chen, H. & Wang, Y. The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: A conservation-of-resources perspective. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 3 (2023).

Ye, J. H. et al. The association of short-video problematic use, learning engagement, and perceived learning ineffectiveness among Chinese vocational students. Healthcare 11, 161 (2023).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134 (1985).

Locke, E. A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social-Cognitive View 169–171 (Englewood Cliffs, 1987).

Schaufeli, W. B. et al. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 33, 464–481 (2002).

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C. & Paris, A. H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109 (2004).

Turner, J. E., Husman, J. & Schallert, D. L. The importance of students’ goals in their emotional experience of academic failure: Investigating the precursors and consequences of shame. Educ. Psychol. 37, 79–89 (2002).

Kiuru, N. et al. Task-focused behavior mediates the associations between supportive interpersonal environments and students’ academic performance. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1018–1024 (2014).

Sökmen, Y. The role of self-efficacy in the relationship between the learning environment and student engagement. Educ. Stud. 47, 19–37 (2021).

Del Toro, J. & Wang, M. T. Longitudinal inter-relations between school cultural socialization and school engagement: The mediating role of school climate. Learn. Instruct. 75, 101482 (2021).

Pianta, R. C. & Steinberg, M. Teacher-child relationships and the process of adjusting to school. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1992, 61–80 (1992).

Legault, L., Green-Demers, I. & Pelletier, L. Why do high school students lack motivation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic amotivation and the role of social support. J. Edu. Psychol. 98, 567–582 (2006).

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M. & De Boer, H. The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 35, 641–680 (2020).

Wang, P., Gan, X., Li, H. & Jin, X. Parental marital conflict and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: The multiple mediating roles of deviant peer affiliation and teacher–student relationship. PLOS ONE 18, e0280302 (2023).

Ransom, J. C. Love, trust, and camaraderie: Teachers’ perspectives of care in an urban high school. Educ. Urban Soc. 52, 904–926 (2020).

Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L. & Oort, F. J. The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 493–529 (2011).

Fernández-Zabala, A., Goñi, E., Camino, I. & Zulaika, L. M. Family and school context in school engagement. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 9, 47–55 (2016).

Valle, J. E., Stelko-Pereira, A. C., Peixoto, E. M. & Williams, L. C. A. Influence of bullying and teacher–student relationship on school engagement: Analysis of an explanatory model. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas) 35, 411–420 (2018).

Heerde, J. A. & Hemphill, S. A. Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 47, 44–62 (2018).

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 52, 30–41 (1988).

Sarason, B. R. et al. Perceived social support and working models of self and actual others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 273–287 (1991).

Cho, H. J., Levesque-Bristol, C. & Yough, M. How autonomy-supportive learning environments promote Asian international students’ academic adjustment: A self-determination theory perspective. Learn. Environ. Res. 26, 51–76 (2023).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78 (2000).

Kang, H. W., Park, M. & Wallace, J. P. The impact of perceived social support, loneliness, and physical activity on quality of life in South Korean older adults. JSHS 7, 237–244 (2016).

Hajovsky, D. B. et al. A parallel process growth curve analysis of teacher–student relationships and academic achievement. J. Genet. Psychol. 185, 124–145 (2024).

Virat, M. Teachers’ compassionate love for students: A possible determinant of teacher–student relationships with adolescents and a mediator between teachers’ perceived support from coworkers and teacher–student relationships. Educ. Stud. 48, 291–309 (2022).

López-Angulo, Y. et al. Social support, gender and knowledge area over self-perceived academic performance in Chilean university students for Mac. Ión Universitaria. 13, 11–18 (2020).

Wang, R., & Ramel, M. R. M. Social support and mathematics anxiety: The mediating role of learning engagement. Soc. Behav. Pers. 51, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.12572 (2023).

Feng, L., He, L. & Ding, J. The association between perceived teacher support, students’ ICT self-efficacy, and online English academic engagement in the blended learning context. Sustainability 15, 6839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086839 (2023).

Rautanen, P., Soini, T., Pietarinen, J. & Pyhältö, K. Dynamics between perceived social support and study engagement among primary school students: A three-year longitudinal survey. Soc. Psychol. Edu. 25, 1481–1505 (2022).

Bandura, A. Regulative function of perceived self-efficacy in personnel selection and classification. In Rumsey, M. G., Walker, C. B. & Harris, J. H. (Eds.). Psychology Press. 279–290 (2013).

Dai, K. & Wang, Y. Investigating the interplay of Chinese EFL teachers’ proactive personality, flow, and work engagement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 1–15 (2023).

Huang, L. & Wang, D. Teacher support, academic self-efficacy, student engagement, and academic achievement in emergency online learning. Behav. Sci. 13, 704 (2023).

Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M. & Galand, B. Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: Comparing three theoretical frameworks. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 326–340 (2019).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37, 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 (1982).

Bandura, A. On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. J. Manag. 38, 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606 (2012).

Khoirunnisa, & Purwandari, E. Student engagement models: Parental support, academic self-efficacy, and the teacher–student relationship. Jurnal Iqra’: Kajian Ilmu Pendidikan 8, 481–494. https://doi.org/10.25217/ji.v8i2.4010 (2023).

Wang, Q., Xin, Z., Zhang, H., Du, J. & Wang, M. The effect of the supervisor-student relationship on academic procrastination: The chain-mediating role of academic self-efficacy and learning adaptation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052621 (2022).

Al Mulhem, H., El Alaoui, K. & Pilotti, M. A. E. Sustainable academic journey in the Middle East: An exploratory study of female college students’ self-efficacy and perceived social support. Sustainability 15, 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021070 (2023).

Wang, C. C. D. & Castañeda-Sound, C. The role of generational status, self-esteem, academic self-efficacy, and perceived social support in college students’ psychological well-being. J. Coll. Couns. 11, 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2008.tb00028.x (2008).

Hayes, A. F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav. Res. 50, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 (2015).

Li, H. Perceived teacher-student relationship and growth mindset as predictors of student engagement in foreign student engagement in foreign language learning: The mediating role of foreign language enjoyment. Front. Psychol. 14, 1177223. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1177223 (2023).

van Rooij, E. C. M., Jansen, E. P. & van de Grift, W. J. First-year university students’ academic success: The importance of academic adjustment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 33, 749–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-017-0347-8 (2018).

Rahim, N. B. The interaction between teaching competencies and self-efficacy in fostering engagement amongst distance learners: A path analysis approach. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 19, 31–57. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2022.19.1.2 (2022).

Zhou, J. & Yu, H. Contribution of social support to home-quarantined Chinese college students’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of online learning self-efficacy and moderating role of anxiety. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 1643–1662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09665-4 (2021).

Liang, S. Y. Study on achievement goals, attribution styles and academic self-efficacy of college students [Master’s Thesis]. Central China Normal University. (2002).

Pianta, R. C. Patterns of relationships between children and kindergarten teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 32, 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(94)90026-4 (1994).

Qu, Z. Y. The classroom environment in primary and secondary schools and its relationship with students’ school adaptation [Master’s Thesis]. Beijing Normal University (2002).

Wang, X. D. (Eds.). Manual of mental health rating scale[M]. Beijing: Chinese journal of Mental Health. 131–133) (Chinese journal of Mental Health Press, 1999).

Ni, K. X. Study on the relationship between college students’ learning engagement and subjective well-being – A case study of six universities in Chengdu [Master’s Thesis]. Chengdu University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.26986/d.cnki.gcdlc.2020.001297 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all the participants in this study for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YXW conceived the study, drafted the manuscript, and took responsibility for the manuscript as a whole. LY provided advice on study design and supervised the data collection. YXW and WWW participated in data collection and data analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wang, L., Yang, L. et al. Influence of perceived social support and academic self-efficacy on teacher-student relationships and learning engagement for enhanced didactical outcomes. Sci Rep 14, 28396 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78402-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78402-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The effect of social support on learning engagement among Chinese nursing interns: the mediating role of self-efficacy

BMC Nursing (2025)

-

The impact of teachers’ caring behavior on EFL learners’ academic engagement: the chain mediating role of self-efficacy and peer support

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

Unraveling the dynamics of online learning engagement: a Cambodian perspective

Educational Research for Policy and Practice (2025)