Abstract

This study aimed to assess its relationship between physical activity with health-related indicators in older population of the China. Cross-sectional data of 1,327 individuals aged 60–79 years were analyzed. Based on the Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Program, depressive symptom and loneliness were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Emotional versus Social Loneliness Scales, respectively. Sleep quality was evaluated through self-designed questionnaire and hypertension was defined as blood pressure > 140/90 mmHg. International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Long Form was conducted to assess the physical activity (minutes and frequency) in different domains (domestic, transport, work, and leisure). Multivariable-adjusted binary logistic regression models estimated for the prevalence of health-related indicators, considering PA level, duration, frequency, and combinations of different domains of PA. In the study, favorable associations were observed between moderate to high level PA and reductions in 4 health-related indicators, especially for active frequency. Moreover, a combination of transport, domestic, and leisure PA was found to be a general protective factor for health-related indicators. In summary, this study highlights the positive impact of PA on older adults’ health and provides valuable insights into the role of different PA patterns, offering a theoretical basis for developing PA guidelines, policies, and health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global population is undergoing a rapid and continuous process of ageing. By the year 2030, it is projected that approximately one in six people in the world will be aged 60 years or over1. Age-related chronic diseases are a significant and growing public health concern as populations worldwide2. Among them, Hypertension is a major global cause of premature death and significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease. According to the Global Hypertension Report, the number of people with hypertension worldwide affecting one-third of adults worldwide in 2019, and a mere 21% have their hypertension controlled3. In addition, increasing number of chronic diseases and transitioning social roles, making the older adults easily having mental health such as loneliness, depression, and poor sleep quality, which could seriously affect the quality of their life4. Globally, mental health is ranked as one of the largest contributors to non-fatal health losses5, about a quarter (27.2%) of suicide deaths occurred in people aged 60 years or older.

The burden of these chronic diseases places considerable strain on healthcare systems and family caregivers, making it crucial to develop effective prevention and management strategies.

Physical activity (PA) has long been recognized has been associated with lower chronic diseases in population6. PA is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles resulting in energy expenditure above a basal level7. The general definition includes more detailed aspects, such as the PA domains, intensity, duration, and frequency8. Two pooled prospective analyses of more than 660,000 older adults in other countries estimated that leisure-time PA within the recommended PA level range (7.5–15 metabolic equivalent task [MET] hours per week) were significantly associated with a reduced risk of mortality compared with participants who did not achieve these activity levels9,10. A recently randomized clinical trial (RCT) reported a 12-week aerobic exercise program reduced 24-h and daytime ambulatory blood pressure (BP) as well as office systolic BP in patients with resistant hypertension11. Moreover, a recently meta-analysis suggests that exercise programs positively affect various aspects of sleep in generally healthy older adults12.

However, most of the evidence is based solely on leisure-time PA or total PA. Actually, PA domains can be categorized as work PA, work PA, work PA, and work PA. Several studies confirming the risks of work-related PA for cardiometabolic health. A large cross-sectional study with more than 260,000 European adults observed the favorable associations between any domain (leisure-, transport- and work-) of PA and depressive symptom severity13. While in the context of a middle-income country, a study conducted in Brazil found that adults aged more than 18 years in the work and domestic domains were associated with an increased depression risk14.

Considering the emergent increase in the incidence of hypertension and mental health problems, there are few studies in China on the relationship between the domains and levels of PA and health-related indicators among the elder population. It is necessary to investigate how different domains of PA are associated with these health-related indicators, taking into account possible nonlinear relationships between them. Therefore, we investigated PA of older adults in various domains, including work-, domestic-, transportation-, and leisure-related activities. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of total PA with health-related indicators in older adults: hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and sleep quality. As well as the differences in the health effects of different combinations of activity domains on older adults.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional study analyzed from the Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Program enrolled in the General Administration of Sports of China in 2019. The National Physical Fitness Test Standard is a nationally representative survey that evaluated physical fitness across three dimensions: body composition, function, and quality. The survey encompasses various diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, heart disease, digestive system disorders, respiratory diseases, and osteoporosis15.

Based on the Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Program, the study conducted a community-based survey of population aged 60 to 79 in Henan Province, China in October 2020. The samples were divided according to region, sex, and every five-year-old (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75–79) into 16 groups with 80 persons per group. Random cluster sampling after stratification according to regional development was performed to select research objects. Inclusion criteria were as follows: Individuals without congenital or genetic diseases (such as congenital heart disease, paralysis, developmental delay, dementia), capable of self-care, possessing basic exercise skills, and demonstrating normal language, cognitive, and comprehension abilities, willing to participate and able to provide informed consent. Participants were excluded if they had a history of other chronic diseases other than the research, could not have normal language expression and thinking abilities, had contraindications to exercise, and failed to sign the informed consent.

Measures

The measurements of exposure (daily PA), outcome for 4 health-related indicators (depressive symptoms, hypertension, poor sleep quality, and loneliness), and covariates (age, sex, education, marital status, region, occupation, smoking and drinking status, and BMI) were respectively assessed across the study.

Assessment of daily physical activity

PA was assessed using the International PA Scale-Long Form (IPAQ-LF)16. The IPAQ-LF is a widely used instrument for assessing PA levels in adults, including older adults. It estimates the time spent being physically active in the last 7 days17,18,19,20. The questionnaire consisted of a 25-item PA survey with three different intensities of activities (low, moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activities) within four domains (work PA, transportation PA, domestic PA and leisure PA). The report of each activity comprised of two main components: average days per week (frequency) and average time per day (duration). The duration (minutes) for each activity per day was multiplied by the activity frequency (days) and the metabolic equivalent (MET) assignment (minutes) for that activity. Using the IPAQ scoring system, PA was graded for each older adult as high, moderate, and low-level PA (high-PA, mod-PA, low-PA) based on activity duration minutes, frequency, and intensity of each activity encountered8. The scoring protocol for the International IPAQ-LF was found in (https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/score), and the IPAQ-LF questionnaire was download in (https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/download).

Outcome assessment for 4 health-related indicators

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is widely used as a screening tool for major depressive disorder21. The questionnaire consisted of 9 items with 4-point Likert-scale responses. Scores were given on the scale of 0–27, and a cut-off of 10 was used to maximize sensitivity and specificity, with a sensitivity of 0.8822. In our study, a total score of < 10 indicated no/mild depression, while a score of ≥ 10 indicated moderate to severe depression.

Loneliness of participants was assessed by Emotional versus Social Loneliness Scales (ESLS) developed by Wittenberg and Reis23. Participants responded to each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often). Responses to the 10 loneliness items were summed to create an overall loneliness score, which could range from 10 to 50. The higher scores indicate a greater level of loneliness experienced over the past year. In our study, the results were divided into ≤ 21 groups and > 21 groups according to the median ESLS score.

Sleep quality was measured using the Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring questionnaire, the questions included “duration of daily naps” and “overall sleep quality in the past month”. The researchers assessed participants’ sleep quality using a five-point scale, ranging from “very good” to “very bad” based on their sleep status over the past month. Participants were then classified into two groups: poor sleep quality and good sleep quality, according to their self-reported assessments.

Following the blood pressure measurement protocol from the Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Program, blood pressure was measured for participants who reported unknown blood pressure status. The blood pressure of those with abnormal blood pressure was repeated three times, and the average of the three readings was recorded. Participants who self-reported hypertension and a history of medication use were exempt from further blood pressure measurements. Finally, hypertension was defined as blood pressure > 140/90 mm or self-reported.

Covariates

Patient demographics and social information were extracted from the fifth national physical fitness monitoring baseline questionnaire, including age (60–64, 65–69, 70–74, and 75–79), sex, education (no education, primary school, middle or high school, and college or higher), marital status (single or spouse), region (rural or urban area), occupation (managerial staff/ intellectual/soldier, businessman, manual worker/farmer or unemployed), smoking status (non-smoker, or current/former smoker), and current use of alcohol (yes or no). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and < 24 kg/m2 was classified as normal weight, ≥ 24 and < 28 kg/m2 as overweight, and ≥ 28 kg/m2 as obese24.

What’s more, sedentary time in the IPAQ-LF questionnaire was also included as.

a covariate. The IPAQ-LF typically asks participants for detailed information about their sedentary time to distinguish between sitting during work and leisure. The questionnaire inquired about how long participants usually sit each day on weekdays (Monday to Friday), covering all work-related activities such as using a computer, attending meetings, and reading documents. It also asks about sedentary time on weekends (Saturday and Sunday), which is generally associated with leisure activities like watching TV, reading, or using a computer for non-work-related purposes. By inquiring about the frequency and duration of daily sitting, the IPAQ-LF can calculate the total sedentary time for the week.

Statistical methods

We summarized baseline characteristics by PA levels using descriptive statistics, reporting median and interquartile ranges of non-normal distribution for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. We compared the baseline characteristics by PA levels using chi-square test for categorical variables. Next, we divided PA into four combined activity groups based on the four distinct domains of PA: patterns A (including work PA, domestic PA, and leisure PA); patterns B (including work PA, transportation PA, and leisure PA); patterns C (including transportation PA, domestic PA, and leisure PA); patterns D (including work PA, transportation PA, and domestic PA). This classification helps to better understand the impact of various types of PA on the health outcomes of the older adults and provides a foundation for developing targeted physical activity interventions.

A binary logistic regression model was used to analyze the odd ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and sleep quality for different PA levels, total PA, and different combined activity patterns of PA. To provides clearer insights that are easier to interpret and apply from a public health perspective, the study also assessed the associations of activity minutes and frequency with 4 health-related indicators with binary logistic regression model. All above models were adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, region, occupation, smoking and drinking status and BMI. Furthermore, to quantify the contribution of different PA levels to the burden of each outcome of health-related indicators, we calculated population attributable fraction (PAF), which can be interpreted as the proportional reduction in population prevalence during follow-up period if all participants had adopted a high-PA25.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the stability of the core findings under varying assumptions. First, to examine whether there was any influence on the results based on low-PA, we repeated the main analysis but only with older adults with moderate and high-level activity. Then, regression models that additionally adjusted for the sedentary time were fitted to examine the statistically independent role of sedentary time in the associations between PA and each of the health-related indicators.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 23.0 and R GraphPad Prism 7. A two-sided P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics review

The present study was approved by the Life Science Ethics Review Committee of Henan Academy of Sports Science, all participants was obtained provide approval before data collection, and signed the written informed consent. All the research involving human research participants have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

General characteristics of the participants

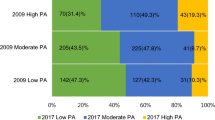

Data of 1,638 individuals were collected for the survey in 2020, after excluding 311 participants due to missing major variables, a total of 1327 participants were included in the final analysis. The baseline characteristics of included observations in the by different PA levels were presented in Table 1. 549 individuals (41.4%) in this study sample achieved high-PA, 767 (57.8%) achieved mod-PA, but only 11 (0.8%) attained low-PA. When PA levels was categorized, the statistical differences in PA levels were observed across groups with respect to age, region, occupation, education level, smoking status, and BMI (P < 0.05).

Association of daily physical activity with health-related indicators

Different daily physical activity levels

Figure 1 illustrated the association between PA levels and different health-related indicators. Results found that moderate to high-PA was associated with lower risk of hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality comparing Low-PA in both crude and adjusted models (P < 0.05).

The odds ratio of hypertension, sleep quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms for moderate to high-physical activity compared with low-physical activity in crude and adjusted models. Each box of forest plot indicates the odds ratio and confidence interval for each health-related indicator. *Adjusted for age, sex, marriage status, education, region, occupation smoking status, current use of alcohol and BMI. Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Different patterns of daily physical activity

Table 2 presented the different domains of PA and the related frequency and duration minutes per week. Among the domains of PA of the older population, family-related PA accounted for the highest proportion (92.9%), followed by leisure-related PA (60.4%), transportation-related PA (56.6%), and work-related PA (25.1%). However, work-related PA have the highest activity minutes, with a median activity minutes reach 420 min. According to the IPAQ-LF scoring protocol on PA intensity, frequency, and duration minutes, the median weekly frequency of PA among older adults in China is 5 days, with a median total of 2040 min.

To integrates different combined activity patterns, taking into account the interaction or synergistic effects among them. Our study divided the four domains of PA into four different combination patterns based on the results of Table 2. The results showed a similar trend in older adults with A (combination of work PA, domestic PA, and leisure PA) and D (combination of work PA, domestic PA, and transport PA) activity patterns, where PA was negatively associated with poor sleep quality, depressive symptoms, and loneliness, while no significant association was found with hypertension. Additionally, the pattern C (combination transport PA, domestic PA, and leisure PA) activity for PA provided the greatest health benefits, showing significant reductions in all 4 health-related indicators (Fig. 2).

Associations of different physical activity combined activity patterns with hypertension, sleep quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. Adjusted for age, sex, marriage status, education, region, occupation smoking status, current use of alcohol and BMI. Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Activity frequency and minutes

To explore the effects of the weekly PA frequency and duration minutes on 4 health-related indicators, as well as to examine the dose–response relationship, participants were grouped according to the frequency and activity minutes quartile shown in Table 2. The results indicated that, except for hypertension, higher weekly duration minutes among older adults were generally associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality, with a clear dose–response relationship observed. In contrast, weekly activity frequency was consistently linked to a reduced risk of hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality, with a similarly evident dose–response relationship (Table 3).

To explore the effects of weekly PA active minutes and related active frequency on 4 health-related indicators, participants were categorized based on quartiles of activity frequency and duration minutes, as presented in Table 3. The results indicated that, except for hypertension, a higher weekly duration of PA among older adults was generally associated with a reduced risk of depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality, demonstrating a clear dose–response relationship. Conversely, weekly activity frequency was consistently linked to a lower risk of hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality, with a similarly evident dose–response relationship.

Estimation of population attribution fraction

PAFs were estimated for 4 health-related indicators associated with PA (Fig. 3). The contribution of high-level PA to the health of older adults was orderly loneliness, depressive symptoms, sleep quality, and hypertension. These findings suggested that 12.60–63.89% health-related indicators outcome would theoretically not have occurred if all participants had increased to high-PA level.

Multivariable-adjusted population attributable fraction (PAF) for 4 health-related indicators by high-physical activity. Each box of forest plot indicates the population attributable fraction and confidence interval for each health-related indicator. Adjusted for age, sex, marriage status, education, region, occupation smoking status, current use of alcohol and BMI.

Sensitivity analysis

The robustness of the associations between moderate to high-PA and 4 health-related indicators were examined by sensitivity analyses (Fig. 4). In partition model, additional adjustment for sedentary time was not essentially changed the association between moderate to high-PA and each health-related indicator, which indicated these associations were statistically independent of sedentary time.

The association of moderate to high-physical activity with health-related indicators after additional adjustment for sedentary time. Activity frequency and minutes were divided into 4 groups, and differences between groups were compared using chi-square tests. Adjusted for age, sex, marriage status, education, region, occupation smoking status, current use of alcohol, BMI, and sedentary time. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Our comprehensive analysis highlights the benefits of PA in reducing hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality among the Chinese older population. Although activities were associated with lower risks of all health-related indicators prevalence, the reductions in loneliness, depressive symptom, and poor sleep quality showed dose–response associations with weekly activity minutes, whereas hypertension was more significantly impacted by the weekly PA frequency. Furthermore, subgroup analyses showed that higher levels of PA in the leisure, domestic and transport domains were related to lower hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality among older adults.

Consistent with other research results12,26, the probability of all 4 health-related indicators in our study decreased with level of PA volume. It is estimated 12.60–63.89% health-related indicators outcome would theoretically not have occurred if all participants had increased to high-PA level. Additionally, our study found the higher exercise minutes does not appear to significant reduction on risk of hypertension. However, as the frequency of exercise increases, the risk of hypertension gradually decreases. This suggested that long-term PA habits may be more effective in reducing the risk of hypertension than merely increasing the duration of exercise. A meta-analysis published in JAMA Psychiatry found for the first time a dose–response relationship between exercise and a reduced risk of depression. Even activity levels below public health recommendations can still provide significant mental health benefits27. Another large prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older participates in the United States suggested the continued reduction in risk for new onset hypertension, when the exercise doses of running (a vigorous exercise) or walking (a moderate exercise) exceeds 450 to 750 MET minutes per week (1.1 to 1.8 MET h/d)28. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommend higher-intensity activity (such as 300 min of moderate-intensity or 150 min of vigorous-intensity activity per week) will bring more health benefits, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression and anxiety29.

The independent effects of different domains of PA on health-related indicators have been widely reported. From different studies suggested that being PA through participation in any type of leisure time activity is associated with lower mortality risks for older adults10,14,30. Several cross-sectional data of Brazilian population showed higher domestic and transport PA levels were related to higher depressive symptoms (at distinct thresholds) in total population, while related to lower depressive symptoms among older adults. Such distinct effects may be explained on how older adults experience PA and deal with the detrimental effect of age on functional capacity14,30. Another higher level of transport and work PA were related to lower depressive symptoms in studies conducted in European countries13 and Korea31. One previous prospective cohort study of 9,350 Chinese adults had found that moderate domestic, transportation, and work PA were associated with a lower risk of new-onset hypertension, maintaining optimal domestic PA levels may be important for primary prevention of hypertension32,33,34.

Nonetheless, people’s activities tend to be multi-domain integrated. Therefore, the findings of previous studies regarding the relationship between health and DPA in single domain should be interpreted with caution, as these findings could have been affected by activity in other regions. Therefore, we conducted different active combination patterns based four domains of PA. Subgroup analysis of PA showed a negative association of different combined activity patterns with depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality in all models, except the pattern B (combination of work PA, transport PA, and leisure PA). The possible reason for the pattern B results is that different types of PA are mutually exclusive, resulting in a low sample size and statistical errors. Additionally, the pattern C (combination transport PA, domestic PA, and leisure PA) activity, which did not report work PA was also negatively associated with hypertension. Overall, the results of the above subgroup analysis showed consistency with the effects of a single PA domain, indicating that the effects of PA levels in different domains on health effects are independent of each other.

Our study has some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, our research data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals experienced restricted movement, changes in social routines, and increased anxiety, leading to lifestyle adjustments. The protective effect of high-level PA observed in our study could be a reflection of adaptive coping strategies, such as increased participation in health-promoting behaviors during this period. Furthermore, the stress of the pandemic might have contributed to mental health challenges, and individuals who engaged in regular, higher-level PA may have seen greater mental health benefits due to the stress-relieving effects of exercise. This also highlights the need to consider environmental and situational factors when interpreting the impact of physical activity on health outcomes in older adults. Secondly, in this study, the one-week PA of the participants was obtained through a questionnaire, so that the data may be biased. In addition to the corresponding measures taken during data acquisition, we performed data outlier elimination and data truncation. Finally, we briefly assessed the sleep quality of the participants, which may have resulted in the omission of some information, and future studies could include scales such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Conclusion

In summary, favorable associations were observed between moderate to high level PA and reductions in hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality. Our analysis also indicates that the decrease in these health outcomes demonstrated dose–response relationships with weekly activity frequency. Finally, a combination of transport, domestic, and leisure PA was found to be a general protective factor for health-related indicators. This study highlights the positive impact of PA on older adults’ health and provides valuable insights into the role of different PA patterns, which providing a theoretical basis for the formulation of PA guidelines, policies and health interventions.

Data availability

Data are available at Henan Scinece and Technololgy Report Service/Research and application of sports and health service platform,http://kjbg.hnkjt.gov.cn/index,for further information contact the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health; 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed Sep 20, 2024.

Khemka, S. et al. Role of diet and exercise in aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and other chronic diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 91, 102091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102091 (2023).

World Health Organization. Global report on hypertension: the race against a silent killer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. p. 1–276.(2023).

Yan, R. et al. Association between internet exclusion and depressive symptoms among older adults: Panel data analysis of five longitudinal cohort studies. EClinicalMedicine 75, 102767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102767 (2024).

Rehm, J. & Shield, K. D. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21, 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0 (2019).

Cao, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, P. & Wang, Y. Associations of sedentary time and physical activity with adverse health conditions: Outcome-wide analyses using isotemporal substitution model. EClinicalMedicine 48, 101424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101424 (2022).

Pender, N. J. Motivation for physical activity among children and adolescents. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 16, 139–172 (1998).

Andrea Di Blasio, Francesco Di Donato & Mazzocco., C. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) – Short and Long Forms.<scoring_protocol.pdf>.(2005).

Arem, H. et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: A detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533 (2015).

Watts, E. L. et al. Association of leisure time physical activity types and risks of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality among older adults. JAMA Netw Open 5, e2228510. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28510 (2022).

Lopes, S. et al. Effect of exercise training on ambulatory blood pressure among patients with resistant hypertension: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2735 (2021).

Vanderlinden, J., Boen, F. & van Uffelen, J. G. Z. Effects of physical activity programs on sleep outcomes in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-0913-3 (2020).

De Cocker, K., Biddle, S. J. H., Teychenne, M. J. & Bennie, J. A. Is all activity equal? Associations between different domains of physical activity and depressive symptom severity among 261,121 European adults. Depress Anxiety 38, 950–960. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23157 (2021).

Werneck, A. O., Stubbs, B., Szwarcwald, C. L. & Silva, D. R. Independent relationships between different domains of physical activity and depressive symptoms among 60,202 Brazilian adults. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 64, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.01.007 (2020).

Science, H. A. o. S. 2019 National physical fitness monitoring report of Henan Province. (2023).

Macfarlane, D., Chan, A. & Cerin, E. Examining the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the international physical activity questionnaire, long form (IPAQ-LC). Public Health Nutr 14, 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980010002806 (2011).

Chen, Y. et al. Relationship between fear of falling and fall risk among older patients with stroke: A structural equation modeling. BMC Geriatr. 23, 647. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04298-y (2023).

Czajkowski, P. et al. The impact of FTO genetic variants on obesity and its metabolic consequences is dependent on daily macronutrient intake. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113255 (2020).

Hur, S. A. et al. Minimal important difference for physical activity and validity of the international physical activity questionnaire in interstitial lung disease. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 16, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-265OC (2019).

Boon, R. M., Hamlin, M. J., Steel, G. D. & Ross, J. J. Validation of the New Zealand physical activity questionnaire (NZPAQ-LF) and the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ-LF) with accelerometry. Br. J. Sports Med. 44, 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.052167 (2010).

Kroenke, K. PHQ-9: Global uptake of a depression scale. World Psychiatry 20, 135–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20821 (2021).

Levis, B., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis. Bmj 365, l1476. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1476 (2019).

Russell, D., Cutrona, C. E., Rose, J. & Yurko, K. Social and emotional loneliness: An examination of Weiss’s typology of loneliness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 1313–1321 (1984).

You, H. et al. Association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among Chinese elderly-evidence from a community-based study. BMC Public Health 18, 1174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6086-1 (2018).

Mansournia, M. A. & Altman, D. G. Population attributable fraction. BMJ 360, k757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k757 (2018).

Del Pozo Cruz, B., Ahmadi, M., Inan-Eroglu, E., Huang, B. H. & Stamatakis, E. Prospective associations of accelerometer-assessed physical activity with mortality and incidence of cardiovascular disease among adults with hypertension: The UK biobank study. J Am Heart Assoc 11, e023290. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.023290 (2022).

Pearce, M. et al. Association between physical activity and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0609 (2022).

Williams, P. T. & Thompson, P. D. Walking versus running for hypertension, cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus risk reduction. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 1085–1091. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300878 (2013).

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979. Accessed Sep 20, 2024.

Lopes, M. V. V. et al. The relationship between physical activity and depressive symptoms is domain-specific, age-dependent, and non-linear: An analysis of the Brazilian national health survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 159, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.01.041 (2023).

Ryu, J. et al. The relationship between domain-specific physical activity and depressive symptoms in Korean adults: Analysis of the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Affect Disord. 302, 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.097 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Occupational physical activity and new-onset hypertension: A nationwide cohort study in China. Hypertension 78, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17281 (2021).

Li, R. et al. Transportation physical activity and new-onset hypertension: A nationwide cohort study in China. Hypertens Res 45, 1430–1440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-022-00973-6 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Domestic physical activity and new-onset hypertension: A nationwide cohort study in China. Am J Med 135, 1362–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.023 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Project Fund of the Henan International Joint Laboratory of Prevention and Treatment of Pediatric Diseases (No. YJZX202206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kaili Yan, Shengfang Gao, and Kaijuan Wang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, and Writing—original draft. Kaili Yan and Qiuyu Sun: Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, K., Gao, S., Sun, Q. et al. Association of daily physical activity with hypertension, depressive symptoms, loneliness, and poor sleep quality in aged 60–79 older adults. Sci Rep 14, 30890 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81798-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81798-w