Abstract

Recent studies have focused on understand lung repair mechanisms, which are critical for treating respiratory diseases. In this study, we develop alveolar organoids to investigate the complex interactions between alveolar epithelial cells, niche fibroblasts and macrophages, which are essential for lung development, maintenance and repair, especially under physiological injury. Our results suggest that alveolar organoids may be a model for epithelial cell regeneration and the inflammatory response in lung tissue. Alveolar organoid studies can also serve as models for various lung injuries and demonstrate mechanisms in the injured human lung.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The distal lung is a complex organ with significant regional, structural, and functional differences. Lung tissue consists of various cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells, as well as alveolar type 2-supporting cells, known as alveolar niche cells. Alveolar epithelial cells are composed of type 1 (AT1) and type 2 (AT2) cells, AT1 cells constituting almost all alveolar regions and accounting for over 90% of the alveolar structure and gas-exchange area. AT2 cells function as progenitor cells that self-renew and differentiate into AT1 cells in the steady state and during regeneration after injury. Alveolar supporting niche cells can activate progenitor or terminally differentiated cells under certain conditions. During lung development, epithelial proliferation, differentiation, tissue regeneration, and repair are influenced by epithelial–mesenchymal communication1,2,3,4,5. Alveolar niche fibroblasts that are observed in alveoli, for example, PDGFR⍺+ mesenchymal and vascular endothelial cells have been identified as niche-supporting6,7. WNT signaling-related mesenchymal cells regulate stem cell properties and the cellular identity of AT2 cells8,9,10. These niche fibroblasts play crucial roles in alveolarization and regeneration, particularly in supporting AT2 cell self-renewal both in vivo and in vitro11,12,13,14,15. These processes involve complex interactions between alveolar epithelial cells and their niche cells. When the lungs are damaged, the maintenance and repair of alveolar epithelial cells and their niche cells depend on alveolar macrophages (AMs) in the affected tissue16,17. This various type of cell mixed conditions, alveolar epithelial cells and their niche cells how control or effect to AMs that remains to be accurately defined poorly understand in organoid system.

Alveolar epithelial and niche cells respond and reactive expression of these complex interactions when their exposed condition. Many researchers developed not only organoids composed of alveolar epithelial cells, but also the other cell composed lung organoids, which were fibroblast cell line or iPSCs derived from macrophage cells18,19,20,21. We aimed to study alveolar organoids (AOs) that specifically represent the alveolar region of the human distal lung and mimic the interaction between alveolar epithelial cells and their niche cells in our defined culture system. Our AOs derived from dissociated human lung cells reflect their donor alveolar conditions. Depending on their exposed condition, our AOs can observe their composed different cells and change cell expression patterns. These AOs are multicellular and maintain a consistent shape, producing subsequent epithelial cell generations under the condition of homeostasis with the use of some of the progenitor cells and was helped by their niche fibroblasts. Because alveolar progenitor cells usually do not activate their self-renewal potential and possessed latent regenerative capacity. When exposed to tissue injury, AOs trigger the AM-activated innate inflammatory response and induce pro-inflammatory signals. This study demonstrates that these inflammatory signals trigger epithelial cell regeneration and cause alterations in epithelial cell composition, similar to the response observed in human lung tissue.

Results

2D to 3D culture conditions for human AOs

We developed a straightforward procedure for isolating single cells from human lung tissue, based on a recently reported culture media approach22. We used tissue dissociated cells derived from the distal parenchymal regions of human lungs from surgery patients in all experiments (n = 198, Fig. 1A and S1A). The dissociated cells consisted of different cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, and stromal cells. Although we provided human distal parenchymal tissue, the composition of dissociated cells varied depending on the donor. We optimized the 2D culture step to enrich specific cell subtypes and increase the collection of proliferative cells from different donors. The 2D cultured cells exhibited colony-forming morphology, starting from a single cell and progressing to clonal groups with over 80% confluence on the culture plate containing small airway growth media (SAGM) (Fig. 1A). Cell morphology appeared typical of AT2-like cells, cuboidal in shape (Fig. 1B). To induce self-organization into AOs, we used human donor-derived cells, including specific niche cells from the alveolar tissue region. Dissociated suspension cells were embedded in Matrigel for 3D culture with SAGM for 7 days. Subsequently, we switched to a defined alveolar differentiation medium containing FGF7, FGF10, dexamethasone, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthin (IBMX) for 20–30 days (Fig. 1A and B). During the first 7 days, AO growth is characterized by cell proliferation, leading to an increase in cell numbers. in the differentiation state, AOs exhibited specific morphologies of AT1 and AT2 cells, along with an air cavity (Fig. 1B bottom). We focused on optimizing the cell culture methods for cells from different donor origins and the formation of AOs. Thus, AOs should consist primarily of alveolar-specific epithelial cells, including AT1 and 2 cells. We used histological techniques to confirm that the AOs consisted of mature AT2 cells expressing pro-surfactant protein C (pro-SPC), surfactant protein C (SPC), human type II alveolar epithelial cell surface marker 280 (HTII-280), and ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 3 (ABCA3) (Fig. 1C). Additionally, AT1 cells expressing HTI-56, podoplanin (PDPN), and aquaporin 5 (AQP5) were observed in our AOs(Fig. 1C). We confirmed alveolar-specific epithelial cell marker patterns in the whole protein expression of AOs using western blotting (Fig. 1D). When cells from the 2D culture system were used, AOs retained similar characteristics and potential across all organoids in Matrigel from the same donor, despite variations in organoid size (Figure S1C). Consequently, these multiple organoid combinations were well suited for Western blot analysis. Both AT2 (HTII-280, pro-SPC, SPC, and ABCA3) and AT1 (HTI-56, advanced glycosylation end-product receptor [AGER], and AQP5) cell markers were expressed in AOs, despite variations in their specific protein amounts (Fig. 1D and F). We performed immunoblotting to determine the presence of matrix-producing fibroblasts (SMA and COL1A1), alveolar niche fibroblast markers (lipofibroblasts, PDGFR⍺ and FGF10), and SHH-expressing myofibroblasts marker, such as GLI1, which formed a portion in AOs. AT2 cells are located near PDGFR⍺ mesenchymal cells, which facilitate AT2 cell proliferation and differentiation into AT1 cells in ex vivo 3D organoid cultures6. To further assess the locations of various mesenchymal cell types, we performed immunostaining for these markers, such as PDGFR⍺ and FGF10, and assessed the proximity of niche cells to the AT2 cells in AOs (Fig. 1E). Only GLI-1-expressing myofibroblasts stained the entire outer structure of the AOs, and PDGFR⍺ double-positive GLI-1 cells were observed in cell clusters inside the AOs. Additionally, these cell clusters expressed both PDGFR⍺ and FGF10. Next, to quantify the composition of AOs cells, we assessed AOs dissociated to single cells and flow cytometry. These data represented donor dependent cell type composition variable and similar pattern of alveolar epithelial cell differentiation rate with alveolar niche cell amounts (Fig. 1F). The observations of these alveolar niche cell markers (FGF10, GLI-1, and PDGFR⍺) indicate that spatially restricted alveolar niche signaling derived from the mesenchyme may affect AT2 cell behavior and alveolarization.

Alveolar organoids (AOs) generation and characterization. (A) Schematic overview of the alveolar organoids (AOs) generating protocol for human lung tissue derived cells. (B) Representative brightfield image of 2D progenitor cells (top left and right) and 3D AOs at different stages of differentiation, early (bottom left) and late (bottom right); scale bar: notation for each. (C) In mature AOs, the expression of alveolar epithelial cell-specific proteins for type 1 (AT1) and type 2 (AT2) cells was examined using immunostaining analysis; scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Western blot analysis for expression of alveolar region-specific cell markers in mature AOs from each of four different donors; n = 4. (E) Immunostaining analysis for expression of niche cell markers in AOs; scale bar: notation for each. (F) Compare the percentage of cellular composition of AOs from different donors evaluated by FACS.

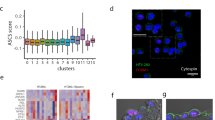

Formation capacity of AOs between alveolar epithelial and niche cells

To examine the formation of AOs and contribution of alveolar niche cells, we assessed the differentiation of alveolar progenitor cells into AOs, with or without a sorting process. LysoTracker (LT)-green, a fluorescent dye that preferentially binds acidic organelles and labels lamellar bodies, is commonly used for live-cell imaging and cell sorting of AT2 cells23,24,25,26,27. Sorted HTII-280 + cells comprised < 5% of tissue isolates, with significant variation between donors due to clinical background and comorbidities affecting lung regeneration potential28. In this study, we expanded the cells in culture dishes to obtain sufficient primary cells for organoid formation and expansion. The AT2 cell origin composed primarily of alveolar cells (LT-positive cells, LT+), with approximately 90% composition. The percentage of AT2-sorted cells varied between 5% and 45% depending on the donor in 2D culture (Fig. 2A and S2A). Thus, the 2D culture step also selection function, as some donors cannot form AOs in Matrigel, which is a prerequisite for subsequent 3D culture. Next, we divided AT2 cells into LT + and AT2 + or AT2- subsets, isolating progenitor cells for differentiation into alveolar epithelial cells. The cells positive for both markers comprised 15.1–42.3% of AT2 + LT + cells and 38.4–84.3% of AT2- LT + cells within these primary 2D cultured cells (Fig. 2B and S2B). The double-positive cells were insufficient to differentiate AOs in our protocol, but LT + AT2- cells differentiated into AOs similar to non-sorted cells and showed differences in organoid maintenance during long-term (40 days) culture. Immunostaining of sectioned samples demonstrated the expression of functional AT2 (HTII-280 and SPC) and AT1 (HTI-56 and AQP5) markers (Fig. 2C). To compare alveolar niche cell expression in AOs, both PDGFR⍺ and FGF10 were expressed in AOs obtained from non-sorted cells (Fig. 2D, E). During human alveologenesis, alveolar niche cells regulate the proliferation, differentiation, and regeneration of alveolar epithelial cells. In our culture system, the niche cell marker FGF10, which aids in the growth of AOs during differentiation, is located close to or clustered inside AOs during organogenesis, unlike AOs generated from AT2-LT + sorted cells (Fig. 2E). Non-sorting culture conditions offer benefits for maintaining alveolar epithelial cell homeostasis in organoid cultures.

Comparison organoid formation ability between sorted and non-sorted cells. (A) Ratio of cell composition of the LysoTracker-positive cell (LT) and the HTII-280-positive cell (AT2); n = 5. (B) Ratio of cell composition in LT-positive cell; LT + HTII-280 + = red bar and LT + HTII-280- = gray bar; n = 5. (C) Immunostaining analysis comparing the AT1 (HTI-56, Aquaporin-5) and A2 (SPC, HTII-280) between non-sorted and AT2-LT + sorted cells. Fluorescence images were captured using a confocal microscope; scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Comparison of expression of alveolar niche cell markers (PDGFR⍺, FGF10) between non-sorted cells and AT2-LT + sorted cells using immunostaining analysis.; scale bar: 100 μm. (E) Immunostaining analysis comparing the expression of AT1 (PDPN) and niche cell (FGF10) between non-sorted and AT2-LT + sorted cells; scale bar: 20 μm and Three-dimensional visualization of the immune-stained structure from bottom of E, shown from a different angle to highlight the spatial organization of PDPN and FGF10 expression in alveolar epithelial cells and niche cells.

Capacity of human AOs for progenitor cell maintenance

We established 2D and 3D culture steps to enhance the use of AOs, although limitations still exist. The organoid-forming efficiency varied between individual donor samples. Despite achieving 78.9% success in AO formation efficiency when transitioning from 2D to 3D culture (Figure S1B), the number of organoids formed differed among individual donors. In some cases, fewer than ten organoids were formed in each Matrigel dome. These organoid-forming efficiency difference dependent on donor had a same result sorting alveolar progenitor cell. We set up hypothesis that alveolar progenitor cells already effected their niche cells and their environments. To account for this progenitor cell variability, we grouped donors with similar organoid formation capabilities and quantified the organoid formation efficiency for three individual donors (Figure S1C). To determine whether there is donor variation in progenitor cell proliferation capacity, we tested the propagation of AOs that serially passaged and regenerated the AOs by single-cell dissociation. Subsequently, we compared thrice-passaged AOs (3rd organoids) to maintain the same donor character, resulting in 3D structures consisting of mature AT2 cells expressing HTII-280 and AT1 cells expressing CAVEOLIN (CAV) in both 1 st and 3rd organoids (Fig. 3A). We determined that the expression type markers for alveolar epithelial type 1 and type 2 cells using western blotting in 3rd organoids (Fig. 3B). The three independent donor-derived AOs underwent complex organoid formation processes and successfully maintained alveolar epithelial cell characteristics up to the third passage. However, the efficiency and number of organoids gradually decreased slightly during subsequent passages. Subsequently, we confirmed that passaged AOs retained their capacity for differentiation from progenitor cells and assessed the expression of these markers through western blotting for early and late differentiation stages in 3rd organoids (Fig. 3C). We hypothesize that alveolar niche cells may influence epithelial differentiation of donor-dependent variations in organoid development. Organoid-specific protein expression showed donor-dependent variation, with alterations in the differentiation levels of alveolar epithelial cell from early to late stages of alveologenesis. These variations were linked to the expression levels of niche cell markers, such as GLI1 and FGF10. Donors with higher expression levels of alveolar epithelial cell markers also exhibited a higher presence of niche cells than other donors (Fig. 3D). Thus, these results observed represent as a human alveolar tissue, when alveolar progenitor cells exposed their niche cells amounts, progenitor cell differentiation potency to AOs formation will affect a correlation between the presence of niche cells and epithelial differentiation.

Alveolar organoids subculture and verification of niche fibroblast presence in AOs. (A) Immunostaining analysis of first (1 st) and third (3rd) passaged AOs from three different donors for caveolin-1 (green) and HTII-280 (red); n = 3; scale bar: notation for each. (B) Western blot analysis of alveolar cell-specific protein expression in 3rd organoids from two different donors; n = 2. (C) Early (E) and late (L) differentiated expression of alveolar cell-specific marker proteins was assessed by western blot; n = 2. (D) Densitometry comparing early and late differentiated AO western blot bands in Fig. 3C; n = 2.

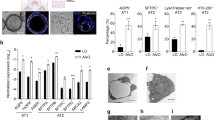

Innate inflammation response of AOs

Using naturally composed alveolar epithelial and niche cells in our culture system, we assessed how normal AOs respond to damage, such as acute tissue injury. We used bleomycin (BLM) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to treat the alveolar injury model. In animal studies, BLM is commonly used to induce lung injury, such as pulmonary fibrosis, and causes acute lung injury and inflammation16,29,30,31. LPS is a major pathogen-associated molecule and well-established activator of proinflammatory molecules32,33,34,35. In our AO system treated with or without BLM (1 µg/mL) and LPS (1 µg/mL) for one day, BLM- or LPS-induced inflammatory signals trigger innate immune system activation, as evidenced by AMs in 30-day differentiated AOs. To confirm these findings, we assayed for CD14+ (expressed primarily in immune cells, such as macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils), AM markers (CD206, mannose receptor), CD169, and CD163 in normal and treated AOs. When exposed to BLM and LPS, CD14 + cells exhibited increased expression levels, with an increase in the co-stained AM marker, CD206+ (Figure S3). The expression of CD206 + or CD169 + AMs was slightly increased, and their shape was altered in BLM-induced AOs, with a more dramatic increase in LPS-induced AOs than in untreated AOs (Fig. 4A and S4A). Here, we present AM expansion/elongation and migration between normal and induced damage conditions using macrophage immunostaining. The human lung upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]−6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF⍺]) when exposed to injury36,37,38,39. The BLM- and LPS-induced AOs increased the expression levels of the pro-inflammatory proteins, IL-6 and TNF⍺ (Fig. 4B and S4B). Additionally, a significant mediator of the inflammatory response, IL-1β maturation by caspase-1, is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by AOs. Moreover, IL-1β facilitated AT2 proliferation and SPC production in AOs (Fig. 4B and S4B). Inflammatory stimuli direct the fate of AT2 cells in injured lungs16,40. The activation of the inflammasome type-1 interferon (IFN) regulates that of other inflammasomes through the activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) signaling pathway18,41. We demonstrated that the activation of AOs sequentially induces the IFN signaling pathways downstream of the activated STAT1/2 signaling pathway (Fig. 4C).

Innate inflammation response of alveolar macrophage within AOs. (A) A comparison of the expression of macrophage markers (CD206 and CD169) between untreated and chemically induced immune responses (BLM or B: bleomycin, LPS); Scale bar: 200 μm (left) 50 μm (right). (B) Western blot analysis of AOs without or treated with chemicals that induce an immune response (BLM or B: bleomycin, LPS). (C) Western blot analysis of AOs by IFNα.

Discussion

Researchers have continually attempted to make organoids closely resemble their native tissues. Lung tissue retains its cell characteristics and functions effectively during the conditions of lung damage42. In this study, we emphasize the importance of combining alveolar epithelial cells with niche cells for the formation of predominant AOs. The propagation of these organoids during AT2 cell division (symmetric or asymmetric) with invading their niche cells, such as mesenchymal cells, should be a harmonious combination. However, previous studies using sorting techniques for alveolar progenitor cells or AOs have faced challenges of low differentiation efficiency and limited progenitor cell quantities18,19,20. Here, we present a combination culture of alveolar progenitor cells and niche cells, which avoids cell sorting and minimizes damage during AO formation. In our culture system, alveolar niche cells provide signaling factors close to AT2 cells to increase cell–cell interactions, supporting the retention of AO characteristics, prolonging cell survival, and promoting complete maturation. This mixed culture closely mimics alveolar tissue. Therefore, when injury signals are induced in AOs, they are used to model diseases by modifying progenitor cells and their niche cells. Generally, most AT2 cells possess latent regeneration potency43,44. Alveolar progenitor cells, actively suppress nearby cells until an injury is exposed26,45. The combined culture conditions of these cells can be applied to various organoid models for drug screening and lung disease modeling. Additionally, our AO culture protocol facilitates tracking of different alveolar mesenchymal cells, influencing stem cells and supporting their self-renewal or differentiation into AT2 or AT1 cells. Moreover, this protocol provides insights into the relationship between alveolar epithelial cells and niche cells. Finally, this study addresses the variability in AO yield among individuals and heterogeneity of organoid composition, suggesting the need for further standardization based on experimental objectives. Future studies should consider these variables when evaluating the properties of alveolar epithelial and niche cells in AOs. Although we present a general culture protocol for differentiating AOs, the optimal duration of exposure to alveolar differentiation media needs to be determined, as this varies based on cell composition, growth patterns, and individual differences. Improvements are also required in developing techniques that represent the interactions between organoid cells and their environment.

Organoid researchers have also been interested in the availability and stability of their organoids over time, including alterations in their capacity and characteristics during organoid culture or their survival limits. In this study, we focus on the ability of alveolar epithelial cell and niche cell interaction in organoids to maintain their tissue-like properties such as regeneration and homeostasis during passage. Our results demonstrated that 3rd generation AOs still express epithelial-specific proteins similar to the 1 st generation AOs from the same individual. In contrast, the alveolar progenitor cells used in 3rd generation AOs do not have unlimited self-renewal potential. Therefore, we cannot guarantee that this protocol will work for all samples, as some cells may not differentiate, pass through passaging successfully. However, when successful results were obtained in all three-time passaged, we observed higher organoid formation efficiency in samples derived from high expressed their niche cells to support alveolar progenitor cell differentiation. Recently alveolar studies have not had a standard to determine the variability in progenitor cell potency among different individuals. Therefore, in future studies, we will consider how variables like donor selection, culture conditions which niche cell presence could impact results.

AMs play a critical role not only in phagocytosis of cellular and pathogenic debris but also in tissue homeostasis by supporting the reconstruction of the alveolar structure. In our culture system, AMs are present in about 5% of AOs. This is independent of the rate of alveolar differentiation (Figure S4 C). We focused on the response of alveolar epithelial cells in organoids to pro-inflammatory signals, working to investigate how niche cells, such as AMs, contribute to the reconstruction of alveolar epithelial cells. Our results showed that AOs composed of various cell types form alveolar tissue. Additionally, upon exposure to injury, these cells can differentiate into a dynamic fate. We observed that before these alterations in cell composition, a pro-inflammatory response was upregulated within the organoids in response to an injury signal such as BLM or LPS. Additionally, innate immune cells, CD14 + cells46,47, and AMs such as CD206, CD163, and CD16948 were activated and amplified within the AOs. The activation of resident AMs, such as CD206, CD163, and CD169, may represent an attempt to counteract the homeostasis of AOs. These findings indicate that IL-1β mediates a pro-inflammatory response and generates novel AT2 cells16,18 when AOs are exposed to BLM- or LPS-induced conditions. Therefore, our AOs exhibited a normal immune response, and inflammasome activation is anticipated to be physiologically regulated by numerous mechanisms. For example, type-1 IFN, activated T cells, post-translational modifications of inflammasome components, and immunoglobulin G (IgG) immune complexes play regulatory roles in inflammasome activation16,17. These findings highlight how various inflammasomes function in AOs and indicate that AO-related studies can serve as broadly representative models for various lung injuries and demonstrate mechanisms in the human injured lung. In this study, we demonstrate the innate immune response of AOs involving AMs in the inflammatory system, without the influence of external environmental factors such as the microvascular network. Further studies examining AOs within vascular microenvironments are essential for understanding cell–cell signaling and enabling pharmacological screening, potentially advancing the use of AOs for cell-based therapies.

Methods

Dissociated cell from human lung tissue

Primary normal lung tissue was obtained from patients with advanced lung cancer by performing fine-needle aspiration or surgically resected biopsies at The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul ST. Mary’s Hospital. Chapping the tissue to a size of 1 mm3 in diameter, add type 1 collagenase (300 mg/ml, Gibco), elastase (0.04 U/ml, Worthington-Biochem), and trypsin from bovine pancreas (18 mg/ml, Sigma) to Hank’s buffer and incubate at 37 °C for 30 min. Remove any remaining large tissue using a 40 μm strainer. Remove red blood cells using red blood cell lysis buffer (Roche). The remaining cells were cultured with the SAGM(LONZA) containing 1% Anti Antibiotic-Antimycotic(A·A) (Gibco) supplemented with Y-27,632 (10µM, TOCRIS) for the first 2 days, then maintained without Y-27,632 in cell culture plates at 37 °C and 5% CO2 conditions. Subculture is performed when cells fill 80% of the plate area.

Culturing human lung progenitor cells derived AOs

Dissociated lung progenitor cells were resuspended into SAGM (LONZA) containing 1% A·A (Gibco) and a final concentration of 60% growth factor-reduced Matrigel (CORNING) was added. 50 µl drops of cell/Matrigel mixture with 3 × 103 lung progenitor cells each were pipetted into the well centers of 24-well plates. After 30 min gelation at 37 °C for the drops to form domes, 500 µl SAGM was added to overlay the domes. The medium is replaced with fresh media once every 2 to 3 days, and after 7 days, it is replaced with alveolar differentiation medium. Organoids formation requires around 3 ~ 4 weeks. They were passaged at 7 ~ 14 days. The following Alveolar differentiation medium composition at the indicated concentration: F-12 media, B-27 supplement, N2 supplement, CaCl2 (0.8 mM, Sigma), BSA fraction 5 (1%, Gibco), HEPES (15 mM, Gibco), IBMX (100µM, Sigma), dexamethasone (50nM, Sigma), 8-BrcAMP (100µM, Sigma), FGF7 (10ng/ml, PEPROTECH), FGF10 (10ng/ml, PEPROTECH), A·A (1%, Gibco).

Cell maintenance and subculture

Human lung progenitor cells were maintained in SAGM (LONZA) containing 1% A·A and enzymatically passaged (1:2) when cells fill 80% of plate area. By a brief PBS wash followed by treatment with ACF enzymatic dissociation solution (STEMCELL, Cat. #05427) for 3 min in CO2 incubator. Cells were dissociated and centrifuged (1500 rpm for 3 min) with ACF enzyme inhibition solution (STEMCELL, Cat. #05428). After removing the supernatant, human lung progenitor cells were resuspended and seeded with SAGM containing 1% A·A, 10µM Y-27,632 (TOCRIS) in culture dish. Replace with fresh media once every 2–3 days and use SAGM containing 1% A·A.

Organoid maintenance and subculture

AOs were allowed to formation for 3 ~ 4 weeks. AOs were subcultured within 3–4 weeks of the culture dates. AOs were collected by dissolving the Matrigel with Cell Recovery Solution (The Well Bioscience) 15 min at 37 °C in an CO2 incubator. After 15 min organoid were enzymatically dissociated by a brief PBS wash followed by treatment with Accutase (CORNING) for 15 min at 37 °C in an CO2 incubator. After 15 min dissociated into single cells by pipetting. Dissociated single cells were re-doming in 60% Matrigel.

Regulation of organoid immune response

To assess the inflammatory response and immune cell activation, AOs are treated with chemical compounds. The AOs are cultured within Matrigel domes and treated with a mixture of media and specific chemical compounds. The compounds used for treatment are IFNα (10ng/ml, R&D systems), LPS (1 µg/ml, Sigma), and Bleomycin (1 µg/ml, Tocris). Each compound is administered separately, and the organoids are incubated for 24 h in an CO2 incubator. After incubation, the Matrigel is removed, and the AOs are isolated and lysed.

Immunofluorescence staining

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min. The fixed samples are either sectioned or stained whole. Before staining, the samples are permeabilized with Triton X-100. Subsequently, the samples are washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After PBS washes, the samples are incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies a at room temperature for 1 h. Following another PBS wash, the samples are stained with Hoechst 33,342 for 10 min to mark nuclei and then imaged under a confocal microscope (LSM900 or LSM800) to detect signaling.

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer (LPS Solution). Proteins were separated in Bolt™ Bis-Tris Plus Mini Protein Gels, 4–12%, 1.0 mm, Invitrogen™ NuPAGE™ SDS-PAGE gel system and transferred to PVDF membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-rad) according to the manufacturer’s guidance. Signal was detected and analyzed by the LAS-3000 imaging system from Fuji. Detected signals were densitometry analysis using ImageJ, a public domain program from the National Institutes of Health that allows image processing.

Flow cytometry (cell sorting)

Cells were dissociated with animal component-free cell dissociation kit (STEMCELL) for 3–5 min at 37 °C and dissociated to single cells by pipetting. After centrifugation, the cells were incubated in PBS with lysotracker green (1:4000, Invitrogen) at room temperature with block the light. After washing in PBS, primary was incubated with the sample at room temperature for 30 min. After washing in PBS, fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody was incubated with the sample at room temperature for 20 min. For organoids, use the same single cell dissociation method used for organoid subcultures for FACS analysis. The organoid dissociation cells were fixed/permiabilized by incubating it with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD Biosciences) for 15 min at room temperature. the samples are washed with PBS and incubated with primary antibodies a at room temperature for 1 h. After PBS washes, the samples are incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies a at room temperature for 30 min. The following secondary antibodies at the indicated dilutions: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 488 (1:1000), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 546 (1:1000). The antibodies were diluted in PBS. The stained cells were filtered through a 35 μm nylon mesh Cell Strainer Snap Cap (Falcon) to remove cell clumps. All the samples were sorted by FACSAria Fusion (BD). Fluorescence was used to detect FITC and PE autofluorescence.

Statement

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB number: KC18 TNSI0033). All human samples were collected after obtaining a written informed consent from all patient donors, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All below described methods were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

This paper does not report original code.Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Min Jae Lim (ace3256@naver.com).

References

Chanda, D. et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell aging impairs the self-organizing capacity of lung alveolar epithelial stem cells. Elife 10 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.68049 (2021).

Correll, K. A. et al. Transitional human alveolar type II epithelial cells suppress extracellular matrix and growth factor gene expression in lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 317, L283–L294. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00337.2018 (2019).

Volckaert, T. & De Langhe, S. P. Wnt and FGF mediated epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk during lung development. Dev. Dyn. 244, 342–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24234 (2015).

Danopoulos, S. & Shiosaki, J. Al Alam, D. FGF signaling in lung development and disease: human versus mouse. Front. Genet. 10, 170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00170 (2019).

Aros, C. J., Pantoja, C. J. & Gomperts, B. N. Wnt signaling in lung development, regeneration, and disease progression. Commun. Biol. 4, 601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02118-w (2021).

Zepp, J. A. et al. Distinct Mesenchymal Lineages and Niches Promote Epithelial Self-Renewal and Myofibrogenesis in the Lung. Cell 170, 1134–1148 e1110, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.034

Green, J., Endale, M., Auer, H. & Perl, A. K. Diversity of interstitial lung fibroblasts is regulated by Platelet-Derived growth factor receptor alpha kinase activity. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 54, 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0095OC (2016).

Kugler, M. C. et al. Sonic Hedgehog signaling regulates myofibroblast function during alveolar septum formation in murine postnatal lung. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 57, 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2016-0268OC (2017).

Li, R., Li, X., Hagood, J., Zhu, M. S. & Sun, X. Myofibroblast contraction is essential for generating and regenerating the gas-exchange surface. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2859–2871. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI132189 (2020).

McGowan, S. E. & McCoy, D. M. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in myofibroblasts differs from lipofibroblasts during alveolar septation in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 309, L463–474. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00013.2015 (2015).

Choi, J. et al. Inflammatory Signals Induce AT2 Cell-Derived Damage-Associated Transient Progenitors that Mediate Alveolar Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 27, 366–382 e367, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.020

Barkauskas, C. E. et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3025–3036. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI68782 (2013).

Lee, J. H. et al. Lung stem cell differentiation in mice directed by endothelial cells via a BMP4-NFATc1-thrombospondin-1 axis. Cell 156, 440–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.039 (2014).

Lee, J. H. et al. Anatomically and Functionally Distinct Lung Mesenchymal Populations Marked by Lgr5 and Lgr6. Cell 170, 1149–1163 e1112, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.028

Nabhan, A. N., Brownfield, D. G., Harbury, P. B., Krasnow, M. A. & Desai, T. J. Single-cell Wnt signaling niches maintain stemness of alveolar type 2 cells. Science 359, 1118–1123. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam6603 (2018).

Katsura, H. et al. Human Lung Stem Cell-Based Alveolospheres Provide Insights into SARS-CoV-2-Mediated Interferon Responses and Pneumocyte Dysfunction. Cell Stem Cell 27, 890–904 e898, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2020.10.005

Youk, J. et al. Three-Dimensional Human Alveolar Stem Cell Culture Models Reveal Infection Response to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Stem Cell 27, 905–919 e910, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2020.10.004

van Riet, S. et al. Organoid-based expansion of patient-derived primary alveolar type 2 cells for establishment of alveolus epithelial Lung-Chip cultures. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 322, L526–L538. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00153.2021 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Transcription factor Etv5 is essential for the maintenance of alveolar type II cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, 3903–3908. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1621177114 (2017).

Kumar, V. Pulmonary innate immune response determines the outcome of inflammation during pneumonia and Sepsis-Associated acute lung injury. Front. Immunol. 11, 1722. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01722 (2020).

Heo, H. R. & Hong, S. H. Generation of macrophage containing alveolar organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells for pulmonary fibrosis modeling and drug efficacy testing. Cell. Biosci. 11, 216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-021-00721-2 (2021).

Lim, M. J. J. & Kim, A. A novel method for generating induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived alveolar organoids: A comparison of their ability depending on iPSC origin. Organoid Organoid. 3, e11. https://doi.org/10.51335/organoid.2023.3.e11 (2023).

Jacob, A. et al. Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells into Functional Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Cell Stem Cell 21, 472–488 e410, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.014

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Long-term expansion of alveolar stem cells derived from human iPS cells in organoids. Nat. Methods. 14, 1097–1106. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4448 (2017).

Chiu, M. C. et al. A bipotential organoid model of respiratory epithelium recapitulates high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. Discov. 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-022-00422-1 (2022).

Wasnick, R. M. et al. Differential lysotracker uptake defines two populations of distal epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cells 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11020235 (2022).

n der Velden, J. L., Bertoncello, I., McQualter, J. L. & Va, & LysoTracker is a marker of differentiated alveolar type II cells. Respir Res. 14, 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-123 (2013).

Hoffmann, K. et al. Human alveolar progenitors generate dual lineage bronchioalveolar organoids. Commun. Biol. 5, 875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03828-5 (2022).

Fandino, J., Toba, L., Gonzalez-Matias, L. C., Diz-Chaves, Y. & Mallo, F. GLP-1 receptor agonist ameliorates experimental lung fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 10, 18091. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74912-1 (2020).

Kathiriya, J. J. et al. Human alveolar type 2 epithelium transdifferentiates into metaplastic KRT5(+) basal cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 24, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-021-00809-4 (2022).

Moore, B. B. et al. Bleomycin-induced E prostanoid receptor changes alter fibroblast responses to prostaglandin E2. J. Immunol. 174, 5644–5649. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5644 (2005).

Dagvadorj, J. et al. Lipopolysaccharide Induces Alveolar Macrophage Necrosis via CD14 and the P2X7 Receptor Leading to Interleukin-1alpha Release. Immunity 42, 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.007 (2015).

He, X. et al. TLR4-Upregulated IL-1beta and IL-1RI promote alveolar macrophage pyroptosis and lung inflammation through an autocrine mechanism. Sci. Rep. 6, 31663. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31663 (2016).

Banoth, B. & Sutterwala, F. S. Confounding role of tumor necrosis factor in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 4235–4237. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI98322 (2017).

Zhivaki, D. & Kagan, J. C. Innate immune detection of lipid oxidation as a threat assessment strategy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00618-8 (2022).

Ware, L. B. & Matthay, M. A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl. J. Med. 342, 1334–1349. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005043421806 (2000).

Ware, L. B. et al. Prognostic and pathogenetic value of combining clinical and biochemical indices in patients with acute lung injury. Chest 137, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-1484 (2010).

Frank, J. A., Parsons, P. E. & Matthay, M. A. Pathogenetic significance of biological markers of ventilator-associated lung injury in experimental and clinical studies. Chest 130, 1906–1914. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.6.1906 (2006).

Dos Santos, C. C. Advances in mechanisms of repair and remodelling in acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 34, 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0963-x (2008).

Katsura, H., Kobayashi, Y., Tata, P. R. & Hogan, B. L. M. IL-1 and TNFalpha contribute to the inflammatory niche to enhance alveolar regeneration. Stem Cell. Rep. 12, 657–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.02.013 (2019).

Kamata, H. et al. Epithelial Cell-Derived secreted and transmembrane 1a signals to activated neutrophils during Pneumococcal pneumonia. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 55, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2015-0261OC (2016).

Rodriguez-Castillo, J. A. et al. Understanding alveolarization to induce lung regeneration. Respir Res. 19, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0837-5 (2018).

Brody, J. S., Burki, R. & Kaplan, N. Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in lung cells during compensatory lung growth after pneumonectomy. Am. Rev. Respir Dis. 117, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1978.117.2.307 (1978).

Desai, T. J., Brownfield, D. G. & Krasnow, M. A. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature 507, 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12930 (2014).

Chong, L. et al. Injury activated alveolar progenitors (IAAPs): the underdog of lung repair. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 80, 145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-023-04789-6 (2023).

Wright, S. D., Ramos, R. A., Tobias, P. S., Ulevitch, R. J. & Mathison, J. C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 249, 1431–1433. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1698311 (1990).

Haziot, A., Tsuberi, B. Z. & Goyert, S. M. Neutrophil CD14: biochemical properties and role in the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in response to lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 150, 5556–5565 (1993).

Bain, C. C. & MacDonald, A. S. The impact of the lung environment on macrophage development, activation and function: diversity in the face of adversity. Mucosal Immunol. 15, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-021-00480-w (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Seung Joon Kim and their lab members for human lung preparation. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1I1 A1 A01059764), and a grant (RS-2024-00397603, RS-2024-00332142) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.K prepare human lung tissue. M.J. L and A.J. designed and conducted the all experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.J. and S.W.K. conceived and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41598_2025_1853_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material 1 We have added a scale bar to figure S3 . Could you please replace the relevant section with this updated version?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, M.J., Kim, S.J., Jo, A. et al. Enhanced application potential of alveolar organoids through epithelial and niche cell interactions. Sci Rep 15, 17538 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01853-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01853-y