Abstract

While play and playfulness are essential for development, its benefits may extend across many aspects of life. Despite the growing interest in the intrapersonal benefits of playfulness, research is sparse on its social consequences in organizations. In this research, we devise and test an expanded model of the social implications of employee playfulness by examining how employee playfulness affects peer perceptions and subsequent social reactions. Through a pre-registered experiment and a multi-wave field study (N = 603), our results show that employee playfulness can evoke peer authenticity perceptions about the focal employee; particularly, when team competitive climate is high. These perceptions contribute to several social benefits for the playful employees, including enhanced leadership judgments, increased social support, and decreased social undermining by peers. Our work expands the understanding of social reactions to employee playfulness by elucidating the underlying mechanisms and identifying key contextual moderators. We discuss the practical implications of our findings, and suggest avenues for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Across cultures and throughout history, playfulness has been fundamental to the successful functioning and adaptability of various species. All mammals play, as do some birds, octopuses, and a few other animals (e.g.,1,2). As Darwin proposed, play is a ubiquitous phenomenon across many animal species and as an extended phenotype, shaped by genetic and evolutionary pressures (cf.2). Play is one of the six primary subcortical bio-emotional systems, found in all mammals to support neuronal growth and emotional homeostasis4. Because of its benefits for survival and reproduction, playfulness has evolved as an adaptive trait that promotes social bonding, creativity, and exploration3,4.

Playfulness has persisted in humans over time and is regarded as part of human nature4. Early studies on playfulness (e.g.,4,5) started to view it as an essential part of human nature, but one predominantly encouraged in children, as adults spend less time playing1,6 and are expected to prioritize responsibility. Research (e.g.,7,8) has increasingly recognized that playfulness, an inherent human trait, persists throughout adulthood. This body of work has explored the diverse manifestations of playfulness in various adult contexts. However, much of this research remains limited to educational and clinical settings, with a strong focus on intrapersonal outcomes. Our work extends this understanding to the workplace, a setting rich in interpersonal interactions, to explore how playfulness shapes interpersonal consequences.

Historically, play and work have been seen as opposing forces (e.g.,9,10). While some scholars challenge this dichotomy (e.g.,2), and a growing body of research highlights the benefits of integrating play into work11,12, there is little understanding of whether exhibiting playfulness in the workplace is socially acceptable. For narrowing this gap, we utilize signaling theory to explain how coworkers perceive and respond to employee playfulness, particularly within highly competitive work environments.

Our research makes three key contributions. First, we shift the focus from intrapersonal benefits of playfulness to its interpersonal consequences within organizational settings. Specifically, we theorize and demonstrate how playfulness serves as a social signal that shapes relational dynamics and interpersonal outcomes in the workplace. Second, we address the underexplored area of authenticity in horizontal, peer-to-peer interactions, showing how playfulness influences coworkers’ perceptions of authenticity and affects interpersonal responses within teams. Third, our research enriches signaling theory by examining how the interpretation of coworker playfulness is shaped by the competitive context in which it occurs. This shifts the focus from the sender’s credibility to the receiver’s contextual frame, offering a more socially grounded and interactional perspective on signal interpretation in organizational settings.

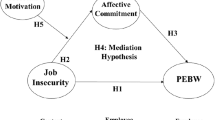

Hypotheses development

Coworker playfulness and perceived coworker authenticity (H1)

Signaling theory13,14 provides a strong theoretical framework for understanding how playfulness influences coworkers’ psychological and behavioral reactions in the workplace. Signaling theory, which emphasizes the reduction of information asymmetry between parties14, is particularly relevant in workplace contexts where coworkers often possess limited insights into each other’s true intentions and values15. Despite frequent social and professional interactions, employees may have limited knowledge about their coworkers, who are often expected to conform to role expectations and suppress aspects of their authentic or core selves in the workplace. It creates information asymmetry between coworkers, and brings about uncertainty in their interaction (e.g., co-workers may conceal malicious intentions to gain personal advantage at the expense of others16). To interact in effective manner, employees are motivated to deal with such information asymmetry in understanding other coworkers, specifically whether the coworker to be authentic or not. Authenticity indicates acting consistently with one’s true and core values17,18 and signifies trustworthiness19,20. An individual with genuine intentions is less likely to conceal malicious motivations towards others. However, authenticity is inherently unobservable20, so coworkers rely on observable signals to infer it.

Following the notion of signaling theory, we propose that playfulness serves as an effective signal of authenticity. To begin with clarification in playfulness, we refer to prior research to regard play as the actual behavior and playfulness as the personality trait that reflects interindividual differences in the disposition to play21. We conceptualize playfulness as “an easy onset and high intensity of playful experience along with the frequent display of playful activities”(22, p. 989). In the following, when we mention play, we regard it as a behavioral manifestation of playfulness or displays of playfulness. Moreover, playfulness is a multifaced trait serving diversified functions, such as other-directed (i.e., social functions), lighthearted (i.e., nonserious, improvise), intellectual (i.e., creativity), and whimsical (i.e., amusement)23. We take such a trait, playfulness, to be an effective signal of authenticity for several reasons: First, playfulness is highly observable. Even in zero-acquaintance settings, participants can accurately infer playfulness from “thin slices” of behavior24,25. Therefore, playfulness fulfills the key criteria of a signal13. Second, playful individuals are often spontaneous and intrinsically motivated22,26. In the workplace, playful employees who prioritize their playful nature over strict adherence to team roles may signal alignment with their intrinsic values26. This aligns closely with perceptions of authenticity, which involves acting consistently with one’s core self17. Research further indicates that uncalculated, spontaneous actions are more likely to be perceived as genuine expressions of one’s true self27. These evidences support that one’s playfulness could function as a credible and reliable signal of authenticity. Therefore, we propose:

H1

A coworker’s playfulness is positively related to peer authenticity perceptions of the focal coworker.

The moderating role of team competitive climate (H2)

Signaling theory13,14 further highlights that the environment significantly influences the value of the signaling process. In our research, we define team competitive climate as a critical environmental factor that influences the effectiveness of playfulness in signaling authenticity. Team competitive climate reflects the level of team members’ shared perceptions that external rewards depend on comparisons of their performance against that of other team members28,29. Competitive team climate could influence the strength of information asymmetry among coworkers and employees’ motivation to deal with such information asymmetry. On one hand, highly competitive team functions in a way more like ‘the jungle’, employees usually view each other more as rivals than cooperators30 and prioritize performance31. This emphasis on competition reduces the likelihood of employees openly expressing their core selves, thus exacerbating information asymmetry among coworkers. On the other hand, the more competitive a team is, the stronger motivation for team members to deal with this information asymmetry. In highly competitive team environments, characterized by a ‘jungle law’ mentality, the consequences of poor interpersonal decisions are more severe. Mistakes in interactions can result in harsher punishments or missed opportunities. This creates a stronger incentive for coworkers to actively seek and interpret signals—such as playfulness—that help them infer authenticity and reduce the risks of careless behavior in interactions.

Moreover, playfulness is likely to be a more effective signal in competive climates. The logics that playfulness as a more effective signal in competitive climates are as follows. In highly competitive climates, norms strongly prioritize performance and seriousness29,30, making playful behaviors stand out as a significant deviation from these norms. This deviation increases the cost for employees to exhibit playfulness, as it risks being perceived as unaligned with workplace priorities. However, this very cost enhances the credibility of playfulness as a signal of authenticity. Employees displaying playfulness in such environments demonstrate a willingness to stay true to their intrinsic nature despite external pressures, reinforcing perceptions of authenticity among their coworkers. In contrast, in less competitive climates, where norms are more relaxed and self-expression is more common, playfulness does not carry the same signaling strength. The behavior aligns more closely with existing norms, making it less distinctive or impactful in signaling authenticity. These considerations lead to the second hypothesis:

H2

Team competitive climate moderates the relationship between a coworker’s playfulness and perceived coworker authenticity, such that the relationship is more positive when team competitive climate is high (vs. low).

The mediating role of perceived coworker authenticity (H3)

Following the signaling theory, we propose that once authenticity is inferred, as a lower information asymmetry between coworkers, coworkers will naturally adjust their behaviors in response. Three essential and complementary behavioral outcomes during workplace interactions are focused in our framework. As for leadership judgement, we take it as coworkers’ natural response to be more willing to follow the one they perceived as authentic. Prior literature largely supported that individuals are prone to trust those they perceive as authentic19,20. Coworkers trust those perceived with high authenticity to be more prone to take their suggestions, follow their instructions, in other words, exhibit willingness in followship. What’s more, authenticity has been found to be a highly regarded leader alike trait32,33, for employees being tired at figuring out what leader’s true intentions are. It has further been proved that individuals tend to trust more on authentic ones to confer them with higher status34 and regard them as owning higher leadership effectiveness15. Therefore, we argue that coworkers will confer higher leadership judgments on individuals perceived as authentic, particularly when they also display playful behaviors.

Regarding social support and social undermining, they separately represent a typical prosocial behavior and a counterproductive behavior. To find out the interpersonal reactions of individuals, researchers normally link these two behaviors together (for example,35,36. Social support refers to psychological or material resources provided through a social relationship with a focal individual37. We contend that coworkers are likely to support employees they perceive as authentic for displaying playfulness at work. Specifically, when employees are perceived as authentic, they are seen as genuine, honest, and trustworthy38. This perception could create a sense of comfort and safety for their peers18,39,40, making it easier for them to connect and build rapport with authentic employees. In addition, the sincerity of authentic individuals41 may motivate peers to work collaboratively toward shared goals and explore how to support their authentic colleagues. Empirical evidence suggests that organizations perceived as authentic tend to garner greater support from stakeholders. This is because authenticity contributes to the development of positive social images42,43,44. Accordingly, we posit that playful employees are prone to be perceived as authentic to receive support from coworkers.

Social undermining is a counterproductive behavior to hinder the focal employee from building and maintaining good relationships, achieving success at work, and building a good reputation45. Employees may be more likely to engage in social undermining of colleagues who are: perceived as focusing primarily on personal gain (instrumental)46,47,48; harboring negative attitudes like cynicism (moral disengagement) or envy49,50;, or simply disliked51,52. When employees perceive a coworker as authentic, they view that person as genuine and honest. In addition, research indicates that because authenticity is generally regarded as a virtue34, authentic people tend to be seen as morally good and nonaggressive53,54. Authentic employees are likely to be perceived as friends rather than potential foes or nuisances. Hence, we argue that coworkers are less likely to “act against” such individuals. Concluding from above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3a

Perceived coworker authenticity mediates the influence of a coworker’s playfulness on leadership judgments.

H3b

Perceived coworker authenticity mediates the influence of a coworker’s playfulness on social support.

H3c

Perceived coworker authenticity mediates the influence of a coworker’s playfulness on social undermining.

Integrating the above reasonings together with H2, we therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H4a

Team competitive climate moderates the indirect effect of a coworker’s playfulness on leadership judgments via perceived coworker authenticity such that this indirect effect is more positive among teams with higher (vs. lower) competitive climate.

H4b

Team competitive climate moderates the indirect effect of a coworker’s playfulness on peer social support via perceived coworker authenticity such that this indirect effect is more positive among teams with higher (vs. lower) competition.

H4c

Team competitive climate moderates the indirect effect of a coworker’s playfulness on peer social undermining via perceived coworker authenticity such that this indirect effect is more negative among teams with higher (vs. lower) competition.

Overview of the present studies

We tested our theoretical model using a diverse set of research methodologies and samples. We first conducted a controlled pre-registered experiment (Study 1) to test our hypotheses and establish the validity of the hypothesized relationships. We then conducted a multi-time survey (Study 2) with team-based samples in real work settings to enhance the generalizability of our results. The datasets of the two studies are publicly available at: https://osf.io/j6284/?view_only=c22f24aa4ade4686a50bf085b16cf2a8/.

The research received ethics approval from the Chinese National Science Foundation (grant 72102040; 72202033). All studies reported in this article complied with all guidelines for the ethical treatment of human participants and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent were obtained from all the participants and there were no expected risks for participants involved.

Study 1

Study 1 (N = 354 full-time employees recruited via Prolific) was a 2 (high vs. low coworker playfulness) × 2 (high vs. low team competitive climate) between-subjects experiment. Participants rated their perceptions of coworker authenticity, leadership judgement toward coworker, and report their behavioral tendencies (i.e., support, undermine) toward coworker. They also complete attention-check and manipulation-check questions.

Sample and procedures

In study 1, we recruited full-time employees via the academic platform Prolific, which, it has been suggested, provides higher-quality data than other platforms55. We pre-registered the study, sample size, exclusion criteria and analysis plan (https://aspredicted.org/blind.php?x=6SF_SLY). The results of priori power analysis based on G*Power 3.1 suggest that a sample size of 327 is required to achieve 95% power at a significance level of 0.05. We targeted at 400 participants to prepare for attrition of careless or incomplete responses. Each participant received an honorarium of approximately 1.20 USD for their participation.

Initially, 403 eligible participants (full time employed and work in teams) completed the study. We followed the data exclusion criterion established in our preregistration: we excluded participants who failed the attention-check question (“Please select somewhat disagree for this question,” N = 36), those who reported that they had not answered the questions honestly (N = 5), those who expressed suspicion about the true purpose of the study (N = 5), and those who completed the experiment within a very short time (less than 2 min, N = 3). These exclusions yielded a final sample size of N = 354 (48% female; 55.6% Caucasian; 45.8% had bachelor’s degree; Mage = 29.67 years; Mwork tenure= 6.4 years).

We adopted a 2 (high vs. low coworker playfulness) × 2 (high vs. low team competitive climate) between-subjects design. Following the suggestion of Tse et al.56, we created our conditions based on the item descriptions of playfulness and team competitive climate scales. All participants were first asked to imagine a realistic workplace scenario in which they work in a sales team at a large organization together with a number of coworkers. Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions presented in the form of scenarios describing their team (i.e., team competitive climate manipulation) and a particular coworker (i.e., coworker playfulness manipulation). Participants then reported their authenticity perceptions about the coworker. Finally, participants were asked to judge the coworker’s leadership potential and their own behavioral intention to support or undermine the coworker. At the end of the study, participants were asked to complete attention-check and manipulation-check questions. They also reported demographic information and indicated their view of the purpose of the experiment.

Team competitive climate manipulation

We manipulated the team competitive climate by generating the following scenarios based on the item descriptions from the scale developed by Brown et al.28: In this team, your team leader usually [seldom] compares your results with those of other salespeople, and the amount of recognition you get in this team depends on [has nothing to do with] how your sales rank compared to others. Gradually, everyone is [never] concerned with finishing at the top of the sales rankings, and your coworkers frequently [hardly ever] compare their results with yours.

Coworker playfulness manipulation

To manipulate coworker playfulness, we adapted the scale descriptions from Proyer22. Participants were presented with a description of a coworker in the team named “Pat” (a gender-neutral name). Specifically, the participants read the following information: Pat, a colleague in your team, is [is not] a playful person. Pat frequently [seldom]

does playful things in Pat’s daily life. Pat sometimes completely [can never] forget(s) about the time and is [be nor] absorbed in a playful activity. It does not take much [It seems impossible] for Pat to change from a serious to a playful frame of mind, and others in the work team also [will never] describe Pat as a playful person.

Measures

The Supplementary Material file provides the full item lists of our manipulation check items (i.e., coworker playfulness) and items measuring the participant’s response (i.e., authenticity perceptions, leadership judgements).

Manipulation check of team competitive climate. We used four items from Brown et al.’s28 to assess the effectiveness of our manipulation of team competitive climate. Sample items included “Everybody is concerned with finishing at the top of the sales rankings” and “Your coworkers frequently compare their results with you” (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.97).

Manipulation check of coworker playfulness. We used five items developed by Proyer22 to assess the effectiveness of coworker playfulness manipulation. Sample items were “Others would describe Pat as a playful person” and “Pat frequently does playful things in Pat’s daily life” (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.98).

Perceived authenticity

On a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”), participants reported the extent to which they agree with each of the following three perceptions toward Pat: “authentic,” “sincere,” and “genuine.” These items were adapted from Gershon and Smith57. Cronbach’s of this scale was 0.82.

Leadership judgments

To assess leadership judgment of Pat, we adopted a 5-item scale from Cronshaw and Lord58. Participants reported the extent to which they agree with each of the descriptions in terms of Pat, such as “Pat has leadership skills” and “Pat fits my image of a leader” (from 1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.95).

Social support

To capture participants’ social support toward Pat, we used the 4-item scale from Caplan et al.59. Sample items included “I will provide money or other things if Pat is in need” and “I will give advice or information when Pat’s things get tough at work”. The participants responded to the items using a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = “very unlikely”, 7 = “very likely”; = 0.77).

Social undermining

To measure participants’ social undermining toward Pat, we adopted the 7-item scale from Duffy et al.60. Sample items were: “I will criticize Pat in front of others” and “I will give Pat the silent treatment”. The participants responded to the items on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = “very unlikely”, 7 = “very likely”; = 0.92).

Results of study 1

We first ran t-test to check the manipulation of team competitive climate and coworker playfulness. The t-test results showed that participants in the condition of high team competitive climate reported higher perceptions of competition in the team (M = 5.97, SD = 1.18) than those in the low team competitive climate (M = 2.66, SD = 1.66), t(352) = 21.53, p < 0.001. And participants in the high playfulness condition reported that Pat is more playful (M = 6.03, SD = 1.15) as compared to those in the low playfulness condition (M = 2.32, SD = 1.54), t(352) = 25.61, p < 0.001. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our team competitive climate and coworker playfulness manipulation.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation of the focal variables. Planned comparisons revealed that, as expected, the participants in the “playful coworker” condition rated the coworker as more authentic (M = 4.95, SD = 0.89) than those in the “non-playful coworker” condition (M = 4.71, SD = 1.03), t(352) = 2.43, p = 0.016, supporting H1. Furthermore, planned comparisons revealed a negative main effect of team competitive climate that the participants in the “low team competitive climate” condition rated the coworker as more authentic (M = 4.95, SD = 0.89) than those in the “high team competitive climate” condition (M = 4.70, SD = 1.02), t(352) = 2.49, p = 0.013.

Figure 1 illustrates a significant 2 (coworker playfulness) x 2 (team competitive climate) interaction effect on perceived coworker authenticity, F(1, 350) = 7.72, p = 0.006. As expected, the participants who work in the highly-competitive-climate team rated their playful coworker (vs. non-playful coworker) as more authentic, t(352) = 3.79, p < 0.001, d = 0.53. The coworker playfulness did not significantly affect authenticity perceptions when the team competitive climate is low, t(352) = 0.21, p > 0.10, d = − 0.03. These results supported H2.

To test the mediation effects, we adopted a bootstrapping procedure (5000 bootstrap samples) recommended by Hayes and Preacher61 to create the 95% confidence intervals. Specifically, we firstly conducted the following mediation analysis using Hayes and Preacher’s PROCESS macro (Model 4): The condition (high coworker playfulness = 1, low coworker playfulness = 0) was entered as the independent variable, perceived coworker authenticity as the mediator, and leadership judgements as the dependent variable. The mediation analysis revealed that high coworker playfulness (vs. low coworker playfulness) led to a higher level of leadership judgement of the coworker through the mediation of perceived coworker authenticity (indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95%CI [0.0001, 0.1002]), supporting H3a. Similarly, high coworker playfulness (vs. low coworker playfulness) led to a higher level of social support toward the coworker (indirect effect = 0.09, SE = 0.04, 95%CI [0.017, 0.169]) and a lower level of social undermining toward the coworker (indirect effect = − 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95%CI [−0.104, −0.007]) through the mediation of perceived coworker authenticity, supporting H3b and H3c.

To test H4a–H4c, we examined whether the indirect effects of coworker playfulness (coded: high = 1, low = 0) on the outcomes via perceived coworker authenticity varied as a function of team competitive climate (coded: high = 1, low = 0). We followed Hayes and Preacher61 recommendations for moderated mediation with multicategorical variables (Model 7), using bootstrapping (5,000 resamples) to estimate conditional indirect effects and their 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals.

For leadership judgments (H4a), the moderated mediation analysis revealed that high coworker playfulness (vs. low coworker playfulness) led to a higher level of leadership judgment of the coworker through the mediation of perceived coworker authenticity when team competitive climate was high (indirect effect = 0.08, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [0.003, 0.197]), but not when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = − 0.00, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.053, 0.041]). The index of moderated mediation was significant (index = 0.09, 95% CI [0.002, 0.222]), supporting H4a.

For social support (H4b), high coworker playfulness (vs. low coworker playfulness) led to a higher level of social support toward the coworker through the mediation of perceived coworker authenticity when team competitive climate was high (indirect effect = 0.18, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.077, 0.317]), but not when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = − 0.01, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.107, 0.085]). The index of moderated mediation was significant (index = 0.19, 95% CI [0.049, 0.366]), supporting H4b.

For social undermining (H4c), high coworker playfulness (vs. low coworker playfulness) led to a lower level of social undermining toward the coworker through the mediation of perceived coworker authenticity when team competitive climate was high (indirect effect = − 0.10, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.197, −0.028]), but not when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = 0.01, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.047, 0.063]). The index of moderated mediation was significant (index = − 0.11, 95% CI [−0.226, − 0.022]), supporting H4c.

Study 2

Study 1 provided initial support for the proposed causality of our model, while several limitations still need to be addressed. First, we assessed participants’ reactions based on their intentions rather than the actual instances of reactions at real work. Second, team competitive climate and coworker playfulness were created and captured using virtual scenarios. Given that evidence from more naturalistic settings can provide greater robustness and validity to the findings56, we thus conducted a multi-wave field survey to address these limitations and retest our hypotheses in Study 2.

Sample and procedures

Participants for Study 2 were recruited from a variety of organizations throughout China. We identified participants using a snowball sampling technique whereby an MBA student at a large university in northern China provided contact information of teams who were willing to participate in this study. A work team is defined as the smallest functional unit in the organization and has three or more employees working together with a unique manager62. Initially, we approached 92 team managers, 62 of whom consented to provide contacts of their team members. We then emailed their team members and informed them orally of the general nature of the study, assuring them that participation was voluntary and responses confidential. Finally, 289 of them consented.

We ran our study over a period of one month and used Wenjuanxing, a survey tool similar to Qualtrics, to host our surveys. Data were collected in two phases with an approximately two-week interval between each survey to minimize the common method bias63. In the Time 1 questionnaire, we asked participants to think about one colleague, write down this colleague’s abbreviated name, and describe this colleague’s playfulness, relative performance, gender, and how long they worked with this person. Participants also provided data on their perceived team competitive climate. In this phase, 249 team members provided complete responses (response rate = 86.16%). Two weeks later, we sent the Time 2 questionnaires to these respondents and asked them to recall and write down the abbreviated name of the colleague they provided in the last survey. Participants rated their perceived authenticity and leadership potential of this colleague and reported their social support and social undermining toward this colleague during the last two weeks. In this phase, 218 provided complete answers. The final sample for analyses included 249 responses (218 at Time 2) nested within 62 teams, with an average team size of 4.02. The average response rate across teams was 78.28% (SD = 22.02%). Among the participants, 40.8% were male and 58.7% had obtained a bachelor degree. The average age was 35.39 years (SD = 7.09) and the average organization tenure was 12 years (SD = 7.36).

Measures

The Supplementary Material file provides the full item lists of the following measures. All survey items presented to participants were in Chinese. All survey questions were translated following the back-translation procedures described by Brislin64.

Coworker playfulness

We adopted the 5-item scale as in Study 1 to measure coworker playfulness. Given our interest in individual perceptions of their playful coworkers, we used an other-reported approach to ask employees to indicate their agreement with descriptions about their nominated colleague. Sample items are “Others would describe him or her as a playful person” and “This coworker frequently does playful things in his/her daily life” (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.89).

Team competitive climate

We used a 4-item scale as in Study 1 to measure team competitive climate. Employees were asked to indicate to what extent team members compete with each other. Sample items included “Everybody is concerned with finishing at the top of the sales rankings” and “My coworkers frequently compare their results with mine” (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.77). We aggregated team members’ ratings to obtain a score for each team’s competitive climate. The results support the aggregation (F [61, 187] = 2.17, p < 0.001; ICC1 = 0.23, ICC2 = 0.54; Rwg = 0.74).

Perceived coworker authenticity

We measured perceived coworker authenticity using a 3-item scale as in Study 1. A sample item is “This coworker is authentic” (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.98).

Leadership judgments of coworker

To measure employees’ leadership judgments of their nominated coworkers, we used a 5-item scale as in Study 1. Sample items included “This coworker has leadership skills” and “This coworker fits my image of a leader” (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.97).

Social support toward coworker

We measured employees’ social support toward the nominated coworkers using 4-item scale as in Study 1. Sample items included “I provide money or other things if this coworker is in need” and “I give advice or information when this coworker’s things get tough at work” (1 = “never” to 7 = “all the time”; = 0.89).

Social undermining toward coworker

We measured employees’ social undermining toward their nominated coworkers using 7-item scale as in Study 1. Sample items include “I criticize this coworker in front of others” and “I give this coworker the silent treatment” (1 = “never” to 7 = “all the time”; = 0.98).

Coworker relative performance (control variables)

Given that prior research has shown strong relationship between relative performance and leadership potential65,66, social support67 and social undermining68. We controlled for the relative performance of the nominated coworkers. Coworker relative performance was assessed using a 4-item scale from Chen et al.69. Sample items are: “Compared with other employees, he or she is one of the better employees at work” and “Compared with other employees, his or her performance meets my supervisor’s expectations more than others” (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”; = 0.94).

Gender, education level, work tenure and relationship tenure (control variables). To rule out the potential influence of the nominated coworkers’ characteristics, we controlled for the gender, education level, work tenure of the coworker, and the relationship tenure between the employee and the coworker. Employees’ gender (0 = male, 1 = female), education level (1 = junior high school, 2 = senior high school, 3 = career/ technical institutions or 2-year community/junior colleges, 4 = bachelor’s degree, 5 = master’s degree, and 6 = doctor’s degree), work tenure (in years) were controlled in the analyses. As employees’ work tenure correlated highly with their age (r = 0.93, p < 0.01), we did not take their age as a control.

Results of study 2

Because employees were nested within teams, we used multilevel modeling70 to test our hypotheses in Mplus 8.4 software71. This approach can accommodate individual-level and team-level effects simultaneously. Coworker playfulness, perceived coworker authenticity, leadership judgments of the coworker, social support and undermining toward the coworker, and all the control variables were at the individual level (i.e., level-1), whereas team competitive climate was at team level (i.e., level 2). To obtain unbiased estimates of the individual-level main effects and the cross-level interaction effects, we group-mean centered all level-1 predictor variables and grand-mean centered the level-2 predictor variable72.

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliability coefficients of the Study 2 variables. We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) on our substantive multi-item variables (i.e., coworker playfulness, team competitive climate, perceived coworker authenticity, leadership judgments of coworker, social support toward coworker, social undermining toward coworker, and relative performance of the coworker) to establish whether the hypothesized 7-factor structure was tenable. Results in Table 3 show that the hypothesized 7-factor model fits the data well (χ2 [443] = 722.8, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.05) and better than alternative nested models with fewer factors (e.g., constraining relative performance of the coworker and perceived coworker authenticity to load onto one factor; all ps for chi-squared difference tests < 0.001; chi-squared differences ranged from 552.29 to 3203.86 with degrees of freedom ranging from 6 to 27).

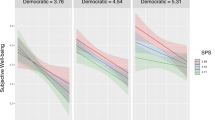

We subsequently conduct a multilevel path analysis. H1 predicts that coworker playfulness is positively related to perceived coworker authenticity. However, as shown in Table 4 (Model 1), this relationship did not emerge as significant (γ = − 0.08, SE = 0.06, p > 0.10). To test our moderation hypothesis, we subsequently examined how the relationship between coworker playfulness and perceived coworker authenticity is influenced by team competitive climate. As shown in Table 4 (Model 2), the interaction effect between coworker playfulness and team competitive climate on perceived coworker authenticity was significant (γ = 0.17, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). In Fig. 2, we plotted this interaction following the recommendations of Cohen et al.73. In line with H2, coworker playfulness had a stronger positive relationship with perceived coworker authenticity when team competitive climate was high (γ = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05). This relationship, however, was not significant when team competitive climate was low (γ = − 0.12, SE = 0.09, p > 0.10).

To test the mediation and moderated mediation hypotheses (i.e., H3a–H4c), we adopted the Monte Carlo method73 to create the 95% confidence intervals for the significance of the indirect effects and conditional indirect effects at high (+ 1 SD) and low (–1 SD) levels of team competitive climate. As found in the test of H1, coworker playfulness did not have a significantly positive effect on perceived coworker authenticity (see Model 1 in Table 4, γ = − 0.08, SE = 0.06, p >0.10), we conclude that H3a, H3b, H3c were not supported.

However, in line with H4a, the results show that when team competitive climate was high, the indirect effect of coworker playfulness on leadership judgments via perceived coworker authenticity was positive and significant (indirect effect = 0.03, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [0.001, 0.082], excluding zero). However, this indirect effect disappeared when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = − 0.03, SE =0.02, 95% CI [ − 0.106, 0.023], including zero). The difference between the indirect effects was significant (difference = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.006, 0.133], excluding zero). Thus, H4a is supported. Supporting H4b, the results showed that coworker playfulness had a more positive and significant indirect relationship with social support via perceived coworker authenticity when team competitive climate was high (indirect effect = 0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.007, 0.106],excluding zero) than it did when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = − 0.04, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [ − 0.102, 0.018], including zero). The difference between the indirect effects was significant (difference = 0.09, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.031, 0.161], excluding zero). H4c also received support. The results indicated that when team competitive climate was high, coworker playfulness had a negative and significant indirect relationship with social undermining via perceived coworker authenticity (indirect effect = − 0.06, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [ − 0.147, − 0.006], excluding zero). This indirect relationship was not significant when team competitive climate was low (indirect effect = 0.05, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [ − 0.021, 0.143], including zero). The difference between the indirect effects was significant (difference = − 0.11, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [ − 0.228, −0.025], excluding zero).

Discussion

Our research offers a new social influence perspective to understand the power of playfulness in organizations, with a focus on understanding how playful individuals are perceived and reacted to in the workplace. Across two studies, we found some evidence for the positive association between coworker playfulness and perceived coworker authenticity. Both studies yielded a significant interaction effect between playfulness and team competitive climate on perceived authenticity and this, in turn, impacts the social benefits that those playful employees receive. That said, an employee displaying playfulness is perceived as more authentic in a high-competitive team climate, which further leads to more social support, less social undermining, and higher leadership judgments from their peers. This indicates that team competitive climate may serve as a social context in which playfulness is evaluated. On a more general level, the findings suggest that playfulness can be an important factor in social evaluations within a team environment and, therefore, it might be fruitful to consider playfulness more frequently in this line of research.

Theoretical contributions

First, we advance the literature on playfulness by shifting the analytical lens from its intrapersonal benefits to its interpersonal consequences within organizational contexts. Prior research has established playfulness as a beneficial trait for the individual, such as enhancing positive affect74, happiness and aspirations75, and job satisfaction76—as well as fostering creativity74,75, emotional resilience74,77, and work engagement10,78. However, relatively little is known about how playfulness is socially interpreted by others in the workplace. By theorizing and empirically demonstrating how playfulness influences coworkers’ social evaluations and responses, our research reconceptualizes playfulness as a social signal—one that shapes relational dynamics and reputational outcomes, thereby extending its relevance well beyond self-oriented benefits.

Second, We contribute to the growing body of organizational research on authenticity by shifting attention to how authenticity emerges in horizontal, non-hierarchical interactions—a setting that has received little theoretical or empirical attention. Existing studies have predominantly focused on judgments of authenticity in relation to high-status or highly visible actors, such as leaders19,79 and organizations80,81. Yet coworkers, who are often the most proximate and frequent interaction partners, represent a critical but overlooked source of authenticity cues. Our research addresses this gap by theorizing that coworkers infer authenticity based on subtle, nonverbal cues—specifically, observed playfulness—and that these inferences shape both supportive and undermining interpersonal responses. This advances authenticity research by offering a new lens through which to understand how peer-based authenticity judgments are socially constructed and how they operate as relational mechanisms within teams.

Third, we further contribute to signaling theory by extending its application to relationally embedded workplace interactions and identifying team climate as a critical boundary condition for signal interpretation. Traditionally, signaling theory has been applied to short-term interactions—such as recruitment decisions, romantic attraction, or newcomer socialization21,82,83—where the signal sender and receiver often have little interpersonal history. In such situations, scholars have emphasized the sender’s credibility, focusing on the importance of signal clarity (i.e., how easily a signal can be understood) and signal cost (i.e., how difficult it is to fake), under the implicit assumption that signal meaning is relatively static and will be interpreted consistently across receivers.

However, workplace relationships are rarely this simple. Coworkers interact with one another repeatedly over time, in settings where norms, roles, and expectations evolve continuously. Yet, research has paid limited attention to how these contextual features shape the interpretation of signals in organizational settings. Our study fills this gap by showing that the perceived meaning of coworker playfulness is shaped by the competitive context in which it occurs. We suggest that signal effectiveness is jointly determined by the characteristics of the signal and the interpretive context of the receiver. It is not only a matter of what signal is sent, but also where and how it is received. This perspective enriches signaling theory by: (a) extending its scope from short-term evaluations to ongoing, socially embedded interactions; and (b) shifting the emphasis from the sender’s credibility to the receiver’s contextual frame, offering a more interactional and socially grounded view of signal interpretation in organizations.

Practical implications

Our findings support the idea that playfulness has significant power in organizations. From a practitioner’s perspective, our research provides several insights. First, with increasing competitive pressures in the contemporary business world, employees may feel the need to suppress their natural instincts to play. However, we suggest that employees should not be afraid to express their playful nature in the workplace, as it can facilitate positive social effects, especially in a highly competitive work climate. An actor can have unique social power when perceived as authentic84. Aligned with this argument, our findings highlight the importance of authenticity in the workplace by suggesting that being perceived as authentic builds effective relationships and strong bonds between team members. Therefore, we recommend that employees strive to build a reputation as authentic colleagues, which can enhance their social influence. As authenticity is about being genuine to oneself, we suggest employees do not try to be someone they are not and embrace their unique qualities and let them shine through at the workplace. At the same time, of course, we encourage organizations to make room and allow for play and playfulness at work—taking their multifaceted nature into account (e.g., social play, intellectual play22).

Accordingly, our study provides insights for organizations and managers. Prior research suggests that employees are more likely to misbehave with coworkers when the workplace climate is highly competitive (e.g.,85). However, we found that employees may show increased social support and decreased social undermining toward coworkers who displayed playfulness in a highly competitive team. In this way, we recommend that organizations and managers understand that interpersonal conflict may be reduced by encouraging play within a competitive climate. On the one hand, organizations should attach importance to playfulness in human resource practices since they may be biased by an assumption that play interferes with achieving financial objectives and maximizing profits. On the other hand, we suggest that managers should tolerate employees who exhibit playfulness and even encourage play in the workplace, especially in times when competition is exceptionally high in team functioning. This could do a great job of helping managers relieve from dealing with conflicts among employees.

Moreover, developing leaders is critical to the success of an organization, yet most HR professionals indicate that they will face significant challenges in developing leaders in the next 10 years86. Our findings suggest that a true leader is someone who can maintain their playful nature even in a competitive climate. Therefore, we offer new guidance for the HR system of leader selection and appointment. From a career-building perspective, employees who engage in play may expect benefits such as increased perceptions of leadership emergence. By recognizing the importance of playfulness in leadership, organizations can develop and promote leaders who can effectively navigate competitive climates while maintaining positive social perceptions among their peers.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

A key strength of this research is that we tested the hypotheses using the multi-method approach with samples from diverse social-culture backgrounds. An experiment and a field survey capitalize on their respective and complementary strengths of internal and external validity. Despite these strengths, several limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the study’s findings. First, concerns may be raised about the causality of relationships in the field study as we collected all the variables from one source. We attempted to minimize such concerns by separating the measures of focal variables in different waves and controlling for theoretically-relevant variables that could confound our proposed relationships. Additionally, these common method bias concerns can be counterbalanced by the randomized experimental design. Therefore, we believe that our findings were robust and likely free of reverse causality issues. Nevertheless, we encourage future researchers to test the proposed relationships using multiple methods, such as archival datasets and field experiments, to eliminate possible common method bias in our studies.

Second and interestingly, we found equivocal support for the hypothesized positive relationship between coworker playfulness and perceived coworker authenticity. Although coworker playfulness is positively related to perceived coworker authenticity in the experimental vignette study, this was not the case in the field study. Drawing on signaling theory13,14, we propose that these discrepancies stem from the nature of the relationships between observers and targets. Participants in Study 2 evaluated coworkers with whom they had prior familiarity (average dyadic tenure = 4.14 years), and such long-term familiarity introduces multiple information sources that can dilute the impact of any single trait cue. Another possible explanation for this inconsistent result might be due to cultural differences. All participants in the field study were recruited from China, whereas none were in the experiment. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that individuals from different countries would exhibit distinct perceptions and attitudes toward coworkers displaying playfulness at work. Despite these differences, the critical moderating role of team competitive climate is clear across both studies. However, we encourage further research on the boundaries of playfulness at work. For example, a question for future research is whether approaches such as implementing playful work designs11 are particularly appealing to more playful individuals. This has practical implications for organizations that seek to foster a positive and supportive work culture, as promoting playfulness among employees may be a way to enhance authenticity and positive social perceptions within teams.

Thirdly, the current study focused only on peer reactions toward coworker playfulness based on signaling theory . Future research could use a different theoretical framework to explore the social implications of playfulness. An interesting future avenue is to integrate social comparison theory and an emotion perspective to investigate how employees will react to a colleague who is more playful than they are. Social comparison theory states that one’s emotions (e.g., envy, contempt, admiration) will arise when an employee feels they do not perform as well as others in a characteristic or dimension, which triggers subsequent behavioral responses87). In this sense, scholars can explore how a playful employee induces certain emotions in their less playful peers and the resulting interpersonal outcomes. Furthermore, by playing at work, employees are able to develop the necessary social connections for work and personal relationships9. These connections are beneficial for health-related outcomes and promote collective cohesion88,89. Thus, future research could adopt a team-level perspective to examine how team members’ playfulness can break down barriers and connect with each other in a team, contributing to positive team outcomes.

Fourthly, as Altschuler90 notes, we do not know whether leaders will encourage their employees to unleash their playful nature or suppress their play and focus solely on technical tasks. In this case, it would be interesting to examine the implications of playfulness by switching from the coworker perspective to how a leader perceives a playful subordinate. On the one hand, play activities may be associated more with being childish4,5 or less focused on technical tasks in the workplace3. Hence, organizational managers may perceive playful employees as poor performers or interpret play as an unnecessary cost to organizations. On the other hand, play is suggested as a way to improve creativity and learning ability90,91. Playful subordinates would therefore generate positive perceptions in their leaders. We believe that examining these potential downsides and upsides of playfulness together from a leader’s perspective is a promising and important avenue for future research.

Finally, we propose a positive path in which employees displaying playfulness could enhance their leader potential in the eyes of coworkers. However, there may exhist alternative pathways where playfulness being interpreted negatively to undermine the focal employee’s leader potential. Indeed, as suggested by the correlation results in our Study 2, coworker playfulness had a positive yet insignificant relationship with leadership judgement (r = 0.06, p > 0.05, Table 2). This may indicate that the relationship can actually be influenced by both positive and negative pathways. We revolves around the positive societal effects of playfulness in workplace interactions here. Whereas, future research could further delve into the negative reactions for displaying playfulness at work to build more complete knowledge.

Data availability

The data that are reported in the present manuscript are made publicly available and can be openly accessed through Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/j6284/?view_only=c22f24aa4ade4686a50bf085b16cf2a8/ The data and data analysis scripts can also be requested from the primary corresponding author: qwang_ying@uibe.edu.cn. Additionally, another contact person can be reached at jiasuosuo@jxufe.edu.cn.

References

Shen, X., Chick, G. & Pitas, N. A. From playful parents to adaptable children: A structural equation model of the relationships between playfulness and adaptability among young adults and their parents. Int. J. Play. 6, 244–254 (2017).

Yarnal, C. M., Chick, G. & Kerstetter, D. L. I did not have time to play growing up… so this is my play time. It’s the best thing I have ever done for myself: What is play to older women? Leisure Sci. 30, 235–252 (2008).

Chick, G. What is play for? Sexual selection and the evolution of play. Play. Cult. Stud. 3, 3–26 (2001).

Saracho, O. N. & Spodek, B. Children’s play and early childhood education: insights from history and theory. J. Educ. 177, 129–148 (1995).

Barnett, L. A. Developmental benefits of play for children. J. Leisure Res. 22, 138–153 (1990).

Van Vleet, M. & Feeney, B. C. Play behavior and playfulness in adulthood. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass. 9, 630–643 (2015).

Mainemelis, C. & Ronson, S. Ideas are born in fields of play: Towards a theory of play and creativity in organizational settings. Res. Organ. Behav. 27, 81–131 (2006).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology (Springer, Berlin, 2014).

Statler, M., Roos, J. & Victor, B. Ain’t misbehavin’: Taking play seriously in organizations. J. Chang. Manag. 9, 87–107 (2009).

Glynn, M. A. & Webster, J. The adult playfulness scale: An initial assessment. Psychol. Rep. 71, 83–103 (1992).

Scharp, Y. S., Bakker, A. B., Breevaart, K., Kruup, K. & Uusberg, A. Playful work design: Conceptualization, measurement, and validity. Hum. Relat. 76, 509–550 (2023).

Bakker, A. B., Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K. & De Vries J. D. Playful work design: Introduction of a new concept. Span. J. Psychol. 23, e19 (2020).

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D. & Reutzel, C. R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manage. 37, 39–67 (2011).

Spence, M. Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 92, 434–459 (2002).

Dietl, E. & Reb, J. A self-regulation model of leader authenticity based on mindful self-regulated attention and political skill. Hum. Relat. 74, 473–501 (2021).

Wheeler, A. R., Halbesleben, J. R. & Whitman, M. V. The interactive effects of abusive supervision and entitlement on emotional exhaustion and co-worker abuse. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 86, 477–496 (2013).

Kernis, M. H. & Goldman, B. M. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 283–357 (2006).

Markowitz, D. M., Kouchaki, M., Gino, F., Hancock, J. T. & Boyd, R. L. Authentic first impressions relate to interpersonal, social, and entrepreneurial success. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 14, 107–116 (2023).

Weischer, A. E., Weibler, J. & Petersen, M. To thine own self be true: The effects of enactment and life storytelling on perceived leader authenticity. Leadersh. Q. 24, 477–495 (2013).

Wickham, R., Warren, S., Reed, D. & Matsumoto, M. Attachment and perceived authenticity across relationship domains: A latent variable decomposition of the ECR-RS. J. Res. Pers. 77, 126–132 (2018).

Chick, G., Yarnal, C. & Purrington, A. Play and mate preference: Testing the signal theory of adult playfulness. Am. J. Play. 4, 407–440 (2012).

Proyer, R. T. Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness: The SMAP. Pers. Individ. Differ. 53, 989–994 (2012).

Proyer, R. T. A new structural model for the study of adult playfulness: Assessment and exploration of an understudied individual differences variable. Pers. Individ Differ. 108, 113–122 (2017).

Brauer, K., Proyer, R. T. & Chick, G. Adult playfulness: An update on an understudied individual differences variable and its role in romantic life. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass. 15, e12589 (2021).

Brauer, K. & Proyer, R. T. Interpersonal perception of adult playfulness at zero-acquaintance: A conceptual replication study of self-other agreement and consensus, and an extension to two accuracy criteria. J. Pers. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12978.

Garrett, L. E. Acting authentically: using play to cultivate authentic interrelating in role performance. J. Organ. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2815.

Wickham, R. E. & Bond, M. H. Accuracy and bias in perceptions of relationship authenticity. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 47–57 (2020).

Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L. & Slocum, J. W. Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. J. Mark. 62, 88–98 (1998).

Fletcher, T. D., Major, D. A. & Davis, D. D. The interactive relationship of competitive climate and trait competitiveness with workplace attitudes, stress, and performance. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 899–922 (2008).

David, E. M., Kim, T., Rodgers, M. & Chen, T. Helping while competing? The complex effects of competitive climates on the prosocial identity and performance relationship. J. Manage. Stud. 58, 1507–1531 (2021).

Lee, W. J., Sok, P., Mao, S. & (& When and why does competitive psychological climate affect employee engagement and burnout? J. Vocat. Behav. 139, 103810 (2022).

Avolio, B. J. & Gardner, W. L. Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Q. 16, 315–338 (2005).

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R. & Walumbwa, F. Can you see the real me? A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadership Q. 16, 343–372 (2005).

Bai, F., Ho, G. C. C. & Liu, W. Do status incentives undermine morality-based status attainment? Investigating the mediating role of perceived authenticity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 158, 126–138 (2020).

Campbell, E. M., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J. & Dong, Y. Hot shots and cool reception? An expanded view of social consequences for high performers. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 845–866 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. Unintended consequences of being proactive? Linking proactive personality to coworker envy, helping, and undermining, and the moderating role of prosocial motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 250–267 (2021).

Jolly, P. M., Kong, D. T. & Kim, K. Y. Social support at work: An integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 229–251 (2021).

Leroy, H., Hoever, I. J., Vangronsvelt, K. & Van den Broeck, A. How team averages in authentic living and perspective-taking personalities relate to team information elaboration and team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 364–376 (2020).

Long, D. M. Tacticality, authenticity, or both? The ethical paradox of actor ingratiation and target trust reactions. J. Bus. Ethics. 168, 847–860 (2021).

Gardner, W. L., Fischer, D. & Hunt, J. G. Emotional labor and leadership: A threat to authenticity? Leadersh. Q. 20, 466–482 (2009).

Mehmood, Q., Hamstra, M. R. W. & Schreurs, B. Employees’ perceptions of their manager’s authentic leadership: Considering managers’ political skill and gender. Pers. Rev. 49, 202–214 (2019).

Pamphile, V. D. & Ruttan, R. L. The (bounded) role of stated-lived value congruence and authenticity in employee evaluations of organizations. Organ. Sci. 34, 2332–2351 (2023).

Beckman, T., Colwell, A. & Cunningham, P. H. The emergence of corporate social responsibility in chile: The importance of authenticity and social networks. J. Bus. Ethics. 86, 191–206 (2009).

Radoynovska, N. & King, B. G. To whom are you true? Audience perceptions of authenticity in nascent crowdfunding ventures. Organ. Sci. 30, 781–802 (2019).

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C. & Pagon, M. Social undermining in the workplace. Acad. Manag J. 45, 331–351 (2002).

Keeves, G. D., Westphal, J. D. & McDonald, M. L. Those closest wield the sharpest knife: How ingratiation leads to resentment and social undermining of the CEO. Admin Sci. Quart. 62, 484–523 (2017).

Sun, S. Is political skill always beneficial? Why and when politically skilled employees become targets of coworker social undermining. Organ. Sci. 33, 1142–1162 (2022).

Thoroughgood, C. N., Lee, K., Sawyer, K. B. & Zagenczyk, T. J. Change is coming, time to undermine? Examining the countervailing effects of anticipated organizational change and coworker exchange quality on the relationship between machiavellianism and social undermining at work. J. Bus. Ethics. 181, 701–720 (2021).

Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J. & Aquino, K. A social context model of envy and social undermining. Acad. Manage. J. 55, 643–666 (2012).

Ganegoda, D. B. & Bordia, P. I can be happy for you, but not all the time: A contingency model of envy and positive empathy in the workplace. J. Appl. Psychol. 104, 776–795 (2019).

Lagios, C., Restubog, S. L. D., Garcia, P. R. J. M., He, Y. & Caesens, G. A trickle-out model of organizational dehumanization and displaced aggression. J. Vocat. Behav. 141, 103826 (2023).

Yu, L. & Zellmer-Bruhn, M. Introducing team mindfulness and considering its safeguard role against conflict transformation and social undermining. Acad. Manag J. 61, 324–347 (2018).

Zhang, Y. & Alicke, M. My true self is better than yours: Comparative bias in true self judgments. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 47, 216–231 (2021).

Ebrahimi, M., Kouchaki, M. & Patrick, V. M. Juggling work and home selves: Low identity integration feels less authentic and increases unethicality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 158, 101–111 (2020).

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S. & Acquisti, A. Beyond the turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 70, 153–163 (2017).

Tse, H. H., Lam, C. K., Gu, J. & Lin, X. S. Examining the interpersonal process and consequence of leader–member exchange comparison: The role of procedural justice climate. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 922–940 (2018).

Gershon, R. & Smith, R. K. Twice-told tales: Self-repetition decreases observer assessments of performer authenticity. J. Personal Soc. Psychol. 118, 307–324 (2020).

Cronshaw, S. F. & Lord, R. G. Effects of categorization, attribution, and encoding processes on leadership perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 72, 97–106 (1987).

Caplan, R. D., Cobb, S., French, J. R. P., Van Harrison, R. & Pinneau, S. R. Job Demands and Worker Health (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, USA, 1975).

Duffy, M. K., Shaw, J. D., Scott, K. L. & Tepper, B. J. The moderating roles of self-esteem and neuroticism in the relationship between group and individual undermining behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 1066–1077 (2006).

Hayes, A. F. & Preacher, K. J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 67, 451–470 (2014).

Greenbaum, R. L., Bonner, J. M., Mawritz, M. B., Butts, M. M. & Smith, M. B. It is all about the bottom line: Group bottom-line mentality, psychological safety, and group creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 41, 503–517 (2020).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Brislin, R. W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216 (1970).

Dries, N. & Pepermans, R. How to identify leadership potential: Development and testing of a consensus model. Hum. Resour. Manage. 51, 361–385 (2012).

Pepermans, R., Vloeberghs, D. & Perkisas, B. High potential identification policies: An empirical study among Belgian companies. J. Manag Dev. 22, 660–678 (2003).

Beehr, T. A., Jex, S. M., Stacy, B. A. & Murray, M. A. Work stressors and coworker support as predictors of individual strain and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 391–405 (2000).

Smith, M. B. & Webster, B. D. A moderated mediation model of machiavellianism, social undermining, political skill, and supervisor-rated job performance. Pers. Individ Differ. 104, 453–459 (2017).

Chen, Z. X., Tsui, A. S. & Farh, J. L. Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: Relationships to employee performance in China. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 75, 339–356 (2002).

Raudenbush, S. W. & Bryk, A. S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Sage, California, 2002).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, 1998–2017).

Hofmann, D. A. & Gavin, M. B. Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. J. Manage. 24, 623–641 (1998).

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. & Aiken, L. Applied Multiple Regression/correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Erlbaum, NJ, 2003).

Yarnal, C. & Qian, X. Older-adult playfulness: an innovative construct and measurement for healthy aging research. Am. J. Play. 4, 52–79 (2011).

Proyer, R. T. Examining playfulness in adults: testing its correlates with personality, positive psychological functioning, goal aspirations, and multi–methodically assessed ingenuity. Psychol. Test. Assess. Model. 54, 103–127 (2012).

Yu, P., Wu, J. J., Chen, I. H. & Lin, Y. T. Is playfulness a benefit to work? Empirical evidence of professionals in Taiwan. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 39, 412–429 (2007).

Brauer, K., Sendatzki, R. & Proyer, R. T. Exploring the acquaintanceship effect for the accuracy of judgments of traits and profiles of adult playfulness. J. Pers. 92, 495–514 (2024).

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. et al. ECIE 2016 11th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Academic Conferences and Publishing Limited, 2016).

Zheng, M. X., Yuan, Y., van Dijke, M., De Cremer, D. & Van Hiel, A. The interactive effect of a leader’s sense of uniqueness and sense of belongingness on followers’ perceptions of leader authenticity. J. Bus. Ethics. 164, 515–533 (2020).

Deeds Pamphile, V. & Ruttan, R. L. The (bounded) role of stated-lived value congruence and authenticity in employee evaluations of organizations. Organ. Sci. 34, 2332–2351 (2023).

Portal, S., Abratt, R. & Bendixen, M. The role of brand authenticity in developing brand trust. J. Strateg. Mark. 27, 714–729 (2019).

Boulamatsi, A. et al. Newcomers Building social capital by proactive networking: A signaling perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 109, 1555–1570 (2024).

Jones, D. A., Willness, C. R. & Madey, S. Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Acad. Manage. J. 57, 383–404 (2014).

Cha, S. E. et al. Being your true self at work: Integrating the fragmented research on authenticity in organizations. Acad. Manage. Ann. 13, 633–671 (2019).

Ng, T. W. Can idiosyncratic deals promote perceptions of competitive climate, felt ostracism, and turnover? J. Vocat. Behav. 99, 118–131 (2017).

Westfall, C. Leadership Development Is A $366 Billion Industry: Here’s Why Most Programs Don’t Work (Forbes, 2019). https://www.forbes.com/sites/chriswestfall/2019/06/20/leadership-development-why-most-programs-dont-work/?sh=12bb454861de

Smith, R. H. Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research (Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, 2000).

Friedkin, N. E. Social cohesion. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 30, 409–425 (2004).

Schermuly, C. C. & Meyer, B. Good relationships at work: the effects of leader–member exchange and team–member exchange on psychological empowerment, emotional exhaustion, and depression. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 673–691 (2016).

Altschuler, M. & I’m a CEO and I play with puppies at work. Here’s why you should too. Money Magazine. (2017). http://time.com/money/4743055/im-a-ceo-and-i-play-with-puppies-at-work-heres-why-you-should-too/

Hunter, C., Jemielniak, D. & Postuła, A. Temporal and spatial shifts within playful work. J. Organ. Change Manage. 23, 87–102 (2010).

Funding

This research was supported by the grants funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72102040; 72202033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, reviewing and editing. L.G. contributed to the project administration, resources, writing the original draft and present manuscript. W.L. and R.T.P. contributed to writing the original draft and present manuscript. S.J. and Y.W. contributed to data analysis and the original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All studies reported in this article complied with all guidelines for the ethical treatment of human participants and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards, even though the authors’ affiliated institution does not have an Institutional Review Board. There were no expected risks for participants involved. Informed consent was obtained from every participant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, L., Liu, W., Proyer, R.T. et al. Understanding the social benefits for playful employees in the workplace. Sci Rep 15, 33834 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04967-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04967-5