Abstract

Our study aims to describe the extent of caregiver burden and its associated factors among family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults in Lebanon in the context of multiple crises. During May–June 2024, a quantitative cross-sectional study was carried out in Lebanon involving 544 caregivers of older adults. Participants were recruited online via various social media platforms. Measures of the caregiving burden and related concepts were executed using validated scales and reports related to the care recipient’s situation. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were conducted to investigate factors associated with caregiver burden. The findings showed that most caregivers were females with lower education levels and facing financial difficulties. Among the participants, 28% reported a severe caregiving burden, 19% a moderate burden, and 24% a mild burden. The burden of caregiving was higher when the care recipient was financially dependent on the caregiver, had dementia or chronic musculoskeletal (reduced mobility) conditions, and was not able to socially integrate. The burden was also higher when the caregiver was older, lived in a remote region, was a part-time worker, had financial distress, provided care for a longer period, used maladaptive coping strategies, had no assistance, and received lower social support. This study showed that the financial difficulties of both the caregiver and the care recipient added to the usual burden of caregiving in the Lebanese context. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions and support systems to alleviate the burden on family caregivers in Lebanon, especially given the country’s rapidly aging population, the difficult multifaceted crisis, and the limited availability of formal care services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world’s older population is expected to continue to grow at an unprecedented rate due to advances in life expectancy and medical technology1. In the Arab world, the older population is growing rapidly, with Lebanon anticipated to have one of the highest proportions of older adults in the region by 20502. It is estimated that the Lebanese older population accounts for a minimum of 10% of the total population3 and could reach 27.1% by 20503,4, highlighting the pressing need for support systems.

Population aging in Lebanon can largely be attributed to declining birth rates, rising life expectancy, and substantial migration rates, intensifying the need for older adults’ care5. The increasing longevity of a population implies that a greater number of individuals will require assistance and care as they approach the end of their lives3. In Lebanon, where the government offers minimal to no support in this aspect, older adults primarily rely on their family members as the main source of security during their later years6. Lebanon’s ongoing economic challenges, which have severely devalued the Lebanese pound, have intensified the caregiving burden on families, who are culturally and practically expected to support aging relatives. Lebanese family members are traditionally expected to assist older relatives with everyday tasks, including household chores, shopping, bill payment, mobility, bathing, dressing, and medication management7,8, as well as providing emotional support and companionship7,9. However, due to the absence of prior qualifications, these caregivers may become physically and emotionally exhausted10,11.

According to research, informal caregivers encounter a significant burden while providing care to older adults with chronic illnesses or dependence12. Caregiving burden is defined as a complex response to the physical, psychological, emotional, social, and financial challenges associated with providing care13,14. It has been found that caregiver burden is associated with lower quality of life and higher depression levels15,16. Burdened caregivers may unintentionally reduce their level of care and overlook essential needs, increasing the importance of understanding these burden factors17.

In the literature, several factors that affect caregiver burden have been identified. Caregiver characteristics such as gender, age, educational level, monthly income, employment status, daily caregiving hours, caregiving duration, relationship with the care recipient, and cohabitation status have been linked to burden levels18,19,20,21,22,23. Regarding care recipient factors, previous studies indicated that age, gender, educational level, the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the degree of impairment in physical and daily functioning were the factors that predicted burden18,21,22. Additionally, social support has been shown to protect against caregiver burden, particularly among dementia caregivers24,25.

Moreover, stress is a major issue for caregivers, and one factor that affects how stressed they are is their ability to cope26. Various coping techniques may be adopted by caregivers in response to the stress of caring for persons with dementia. The caregiver coping mechanisms might increase or decrease the burden27. A cross-sectional study conducted among 57 caregivers of patients with dementia found that when coping with disruptive behaviors or depressive issues of dementia patients, caregivers sometimes resort to avoidance or wishful thinking28. Moreover, previous research revealed that maladaptive or dysfunctional coping strategies, mainly underlying avoidance strategies, would be associated with high levels of sadness and burnout in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers29.

In the Arab world, studies on caregivers of older adults remain scarce30. Despite the rising older adult population, few studies have focused specifically on the burden of caregivers for older adults in Lebanon. One study primarily compared the mean burden scores based on caregivers’ and older adult relatives’ characteristics, while another explored the relationship between caregiver health—assessed through three indicators: psychological well-being, role strain, and feeling helplessness—and various aspects of caring for older adults with impairments30,31. The first study did not investigate predictors of burden and was limited by its very small sample size (64 caregivers), while the second study was conducted quite some time ago (2005). Additionally, both studies lacked regional representation and did not investigate predictors of burden comprehensively. Another small-scale study of Lebanese dementia caregivers found that a large proportion of caregivers reported a severe level of burden (41%) though it sampled only a small, non-representative group32. Considering the aforementioned gaps, demographic shifts, and the economic crisis affecting the country, it is crucial to examine the care burden of older adult caregivers throughout all regions of Lebanon.

Hence, our study aims to describe the extent of caregiver burden and its associated factors among family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults in Lebanon. Conducting this research will provide valuable insights into the burden faced by caregivers of older adults, which could help healthcare authorities better meet their needs.

Methods

Study design and participants

During May–June 2024, a quantitative cross-sectional study was carried out in Lebanon involving caregivers of older individuals. Participants were recruited online via various social media platforms (WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram). The study’s inclusion criteria specified that participants had to be family caregivers providing support to community-dwelling older adults residing in Lebanon and had to have access to the internet to complete the survey.

Family caregivers may include spouses, sons, daughters, or other relatives who provide care for older adults living in the community (aged 65 years or older). Those caregivers should provide care without compensation and possess basic literacy skills However, participants who refused to participate were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Demographic data and other information were acquired from caregivers online using a Google Form, and the call for participation was made via social media platforms using the snowball technique. Caregivers were requested to fill out the three sections included in the questionnaire, which took around 20 min. The questionnaire was available in Arabic, Lebanon’s native language.

Sample size calculation

The minimum sample size was calculated using the G-Power software, version 3.0.10. Since the main dependent variable is continuous, the minimal sample size calculation was conducted based on a regression model. The calculated effect size was 0.0526, expecting a squared multiple correlation of 0.05 (R2 deviation from 0) related to the Omnibus test of multiple regression. The minimum necessary sample was n = 415, considering an alpha error of 5%, a power of 80%, and allowing 15 predictors to be included in the model.

Instruments

Caregivers were asked to fill out a questionnaire in three sections. The first and second sections collected demographic data and other characteristics for caregivers and care recipients (if applicable, as reported by the caregiver), respectively. The following information were collected for caregivers: gender, age, marital status, educational level, place of residence, living region (urban/rural), co-residing with the care recipient versus living separately, caregiver relationship with the care recipient (son/daughter, son/daughter-in-law, spouse, siblings, others), working status, working hours (part-time/full-time), being a health care professional, number of dependent children, and household monthly family income. Additionally, lifestyle factors including, smoking status (cigarettes and nargileh), physical exercise, and number of sleeping hours were collected. Caregivers were also questioned about whether they receive help from a home assistant in caring for the older adults, the time of caregiving per day (hours), and caregiving duration (years). Moreover, they were asked to indicate whether they intended to continue providing care for the older adults in the future.

For care recipient characteristics, caregivers were requested to report the following information: socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, educational level, and financial status, along with clinical data, including diagnoses of dementia and other chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), among others. Multiple chronic diseases in our research were defined as having two or more chronic diseases. Additionally, care recipients’ basic functional abilities and instrumental activities of daily living were assessed using two scales present in the questionnaire’s third section. Caregivers were also questioned about the ability of their care recipients to be left alone and to engage with their social environment.

The questionnaire’s third section comprised scales that assessed the functional autonomy of care recipients, along with scales that examined caregiver financial distress, burden, perceived social support, and adopted coping strategies. We received permission to utilize all the scales in our study. These scales included:

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-22)

is the most commonly used tool to assess caregiver subjective burden levels33. It evaluates the various impacts of caregiving, including physical, emotional, social, and economic aspects34. Each question on the ZBI-22 measures the respondent’s subjective burden by asking, “Do you feel or do you wish?” The answers to these questions are optional and scored from 0 to 4 (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = quite frequently, 4 = nearly always), except for question 22, which is scored differently (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely). The ZBI-22 total score ranges from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating a greater subjective burden. The Arabic version of the ZBI scale available at the Mapi Research Trust was used in our study35. The ZBI demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this research, as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.915.

The Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living (ADL),

consisting of six items, was used to assess the basic activities required for independence in self-care (hygiene, dressing, feeding, toileting, transferring, and sphincter continence)36. The validity of the Arabic version of the ADL scale has been demonstrated among Lebanese older adults living in nursing homes. Each item was rated on a scale of 0, 0.5, or 1, with 0.5 denoting partial independence37. Higher scores indicate greater functional independence in self-care activities.

The Autonomy in Daily Functioning-Contemporary Scale (ADF-CS),

comprising 11 items, was used to evaluate dependence in performing instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) in the modern community. These activities include using landlines and mobile phones, navigating beyond walking distance, shopping, housekeeping, managing medication, food preparation, traveling alone abroad, using television, managing finances, and operating household electrical devices. Each item on this scale has response options ranging from 1 (dependent) to 2 (partially dependent) to 3 (independent), with the total score calculated by summing responses across all items. A higher score reflects a greater level of functional independence in performing IADL. Following a thorough literature review and successive rounds of expert evaluation, we developed the ADF-CS items. Using a rigorous methodology, the scale was subsequently translated, cross-culturally adapted, and validated in Lebanon. It has demonstrated good psychometric properties and is thus effective for assessing functional autonomy in Arabic-speaking community-dwelling older adults. The results indicated high internal consistency of the ADF-CS (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.901) in addition to significant findings regarding its structural, convergent, and known group validity. Further details on the validation process can be found in an article that has been accepted for publication.

The Incharge Financial Distress-Financial Well-Being Scale (IFDFW)

is a validated instrument used to measure financial well-being/distress. It consists of eight items, and responses are rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 10. The total score ranges from 10 to a maximum of 80, and the lower the score, the greater the financial distress level38. We used the Arabic version of this scale, which has been already validated in Lebanon39.

The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief COPE-28)

is a 28-item scale that measures the degree to which a caregiver uses a coping strategy. The 28 items are divided into 14 different coping strategies (2 items for each domain). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with choices ranging from 1 (“I haven’t been doing it at all”) to 4 (“I have been doing it a lot”)40. Stress coping strategies can be classified as adaptive or maladaptive coping strategies. The maladaptive coping strategies included self-distraction, self-blame, substance use, venting, denial, and behavioral disengagement, while the adaptive coping strategies included planning, acceptance, active coping, positive reframing, religion, instrumental support, emotional support, and humor41. The maximum score of the maladaptive strategies is 48, whereas that of the adaptive ones is 64. The COPE-28 scale-Arabic version has been validated in Saudi Arabia42, and its Cronbach’s alpha was satisfactory in our study (α = 0.833).

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MDSPSS)

is a concise research instrument designed to evaluate perceived social support. It consists of a total of 12 items that are further divided into three subscales, with four items each, representing the dimensions of family, friends, and significant individuals. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The overall score is determined by summing up the scores of all the items. A higher score indicates an increased level of social support43. The MDSPSS-Arabic version was validated in Lebanon44.

Data management and analysis

The statistical software SPSS version 27.0 was used for data entry and analysis. Descriptive statistics were reported as means and standard deviations (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables (if non-normal distribution); frequency (n) with percentages (%) were displayed for categorical variables. A bivariate analysis was conducted to investigate differences in caregiver burden across various care recipient and caregiver characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test, Spearman’s correlation, and Mann-Whitney U test were executed due to the non-normal distribution of the caregiver burden. Variables showing a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariate analyses were subsequently included as independent variables in the multivariable models45. Multiple linear regression analyses were executed to investigate the potential factors associated with caregiver burden. The first model focused on care recipient characteristics, the second on caregiver characteristics, and the third merged both sets of variables. We assessed multicollinearity using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), all of which were below the recommended threshold of 5, indicating no issues with multicollinearity. Unstandardized regression coefficients (β) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. The statistical significance level was set at a P-value < 0.05 (two-sided).

Ethical consideration

The research received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Public Health, Clinical Epidemiology, and Toxicology—Lebanon (INSPECT-LB) under the reference number 2024REC-001-INSPECT-01–13. The investigators of the study adhered to the research ethics protocols delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association Assembly46. All caregivers provided online informed consent to confirm their voluntary participation. Besides, all participants had the right to decline participation, and their anonymity and confidentiality were carefully safeguarded and respected throughout the study.

Results

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the characteristics of care recipients and their bivariate association with the ZBI scores, which measure caregiver burden. The median age of care recipients was 75.5 ± 15 years. Most of the care recipients were females (70.4%), 44.5% were illiterate, and 37.5% were financially partially dependent on their caregivers. Regarding the health status of care recipients, about a quarter had dementia (24.6%), 58.8% had chronic diseases like CVD, 67.5% had hypertension, 44.9% had diabetes, and 25.4% had chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Additionally, 7.4% of care recipients had cancer during the past five years, and 8.8% suffered from bedsores. Furthermore, about 12% of the care recipients were completely incontinent, and most of them (88.4%) had multiple chronic diseases. The median scores for ADL and ADF-CS among the 544 care recipients were 4 (IQR: 3.5) and 18 (IQR: 8), respectively, suggesting moderate levels of independence. About a quarter of care recipients needed constant monitoring (25.9%), and 39.5% had a limited ability to integrate socially.

In bivariate analyses, caregiver burden was significantly associated with care recipients’ financial status, dementia, and several chronic diseases, including CVD, diabetes, and musculoskeletal conditions. Additionally, burden was associated with continence and health conditions like bedsores and functional disability, as evaluated by the ADL and ADF-CS scores. Finally, the ability to be left alone and social integration were found to be significantly associated with caregiver burden.

Table 2 presents caregiver demographic characteristics and their bivariate association with care burden. The median age of the caregivers was 40 (IQR = 15) years. Most caregivers were females (84%), married (66.9%), had a university level of education (36.9%), and were the sons or daughters of their care recipients (61.9%). About two-thirds of the participants lived in urban areas (61.2%), especially Beirut (30%), and were co-habitats with their care recipients (85.7%). Almost half of the caregivers were employed (55.3%), 24.1% worked full-time, 83.3% were not health care professionals, and 44.3% had a household family income of less than 250 USD per month.

Moreover, the majority of the respondents were non-smokers of cigarettes (74.4%) and nargileh (65.3%), slept less than 7 h (75.2%), and did not exercise regularly (86%). Participants’ median number of dependent children ± IQR and median financial distress ± IQR were 1 ± 2 and 25 ± 26, respectively. Bivariate analyses revealed that burden was positively associated with caregiver age but negatively associated with participants’ financial distress due to the reverse scoring of this scale. Additionally, gender, caregiver relationship and cohabitation with the care recipient, and household family monthly income were significantly associated with care burden.

Regarding caregiving characteristics, almost all caregivers (98.5%) would continue caring for older adults in the future. The median time of caregiving per day (hours) and caregiving duration (months) were 8 (IQR: 10) hours and 24 (IQR: 36) months, respectively. About one-third of caregivers (27.4%) were getting help taking care of older individuals. Both the time of caregiving per day and the duration of caregiving were positively and significantly correlated with care burden. A higher burden was also reported among caregivers not receiving assistance from a home aide (Table 3).

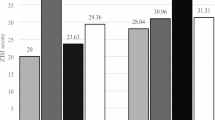

The ZBI scores for the 544 family caregivers who participated in this study showed a median of 29 (IQR: 23) and a mean of 31.27 (SD: 16.91). Figure 1 illustrates caregiver burden levels, categorized according to severity. The results showed that about a third of caregivers (27.8%) experienced severe burden (scores between 41 and 88), 18.6% experienced moderate burden (scores between 31 and 40), and 23.7% experienced mild burden (scores between 21 and 30).

Table 4 shows a statistically significant positive correlation between caregiver burden and maladaptive coping strategy scores (r = 0.27). A significant negative correlation was found between caregiver burden and social support scores (r = −0.18). No statistically significant correlation was found between caregiver burden and adaptive coping strategy scores (P-value > 0.05).

Table 5 reports the findings from the multiple linear regression analysis of caregiver burden. In the bivariate analysis, several characteristics of care recipients and caregivers showed a p-value < 0.2; they were included in Model 1 and 2, respectively. Caregivers reported higher levels of burden when caring for older adults who were financially dependent on them, had dementia or chronic musculoskeletal conditions, or were socially isolated (Model 1). Among the caregiver characteristics (Model 2), higher caregiver burden was significantly associated with older age, residing in the South/Nabatiyeh districts, co-residence with the care recipient, financial distress, and longer hour and duration of caregiving. Additionally, social support and maladaptive coping strategies retained significance in this model. After considering both care recipient and caregiver characteristics that were significant in the bivariate analysis (Model 3), all care recipient characteristics identified in Model 1 continued to show significance. However, for caregiver characteristics, only financial distress, caregiving duration (months), maladaptive coping strategies, and social support retained significance in model 3. Furthermore, place of residence (North/Akkar), working hours (part-time vs. full-time), and getting help from a home assistant became significant in this model. Model 3 explained 30.7% of the variance, compared to 17.6% and 19.3% explained by models 1 and 2, respectively.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the burden of home caregiving in Lebanon, revealing a significant impact on caregivers of care recipients with various diseases. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to assess the burden of home caregiving in Lebanon following multiple severe crises. Findings revealed that 70% of caregivers reported experiencing some level of burden: 28% reported a severe burden, 19% a moderate burden, and 24% a mild burden, with a mean ZBI score of 31.27, indicating an overall moderate burden. This level of burden aligns with findings from other Arab countries, where rapid aging trends have similarly placed heavy caregiving responsibilities on families who traditionally serve as primary support for older adults47. For instance, a cross-sectional survey conducted in Saudi Arabia among 384 caregivers found a mean ZBI score of 31.30 among caregivers, with 78.1% reporting musculoskeletal problems48. Likewise, a study conducted among 288 caregivers from rural lower Egypt reported a ZBI score of 35 ± 15, indicating a moderate burden level49. Our results indicate that the caregiver burden in Lebanon is comparable, if not exacerbated, due to economic strain and sociopolitical challenges unique to the country. Our findings are also close to those found by Chaaya et al. for dementia and highlight the challenges faced by family caregivers in Lebanon, where cultural and religious values emphasize the central role of family care for the older adults30. The high percentage of caregivers experiencing severe burden (28%) is particularly concerning, as it may lead to negative outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and poor physical health for the caregivers31. Further research may be needed to assess the prevalence of these mental health outcomes among Lebanese caregivers and to explore culturally appropriate interventions.

This study also provides a demographic snapshot of Lebanese caregivers, who are predominantly middle-aged women with a median age of 40, slightly younger than those reported in other Lebanese studies30,31. The significant gender imbalance, with women accounting for 84% of caregivers, reflects traditional caregiving roles. Over a third (36.2%) of caregivers have intermediate or lower education, and more than half (57%) live with their care recipients, suggesting a high level of direct involvement in daily care and thus a higher emotional implication. Despite their caregiving responsibilities, a majority (55%) maintain employment. These demographics mirror previous findings, suggesting a persistent caregiver profile over time in Lebanon30,31.

The care recipient population is predominantly female (70.4%) with a median age of 75.5 years, indicating a significant aging female demographic in need of care—consistent with previous Lebanese findings reporting 65% of care recipients were women31. A substantial portion (44.5%) of care recipients is illiterate, similar to the figures reported by the Central Administration of Statistics in Lebanon50; this gender and educational disparities in older age may impact their ability to navigate healthcare systems and understand medical information contributing to caregiver burden9. These educational barriers highlight the need for tailored communication methods to support health literacy among older adults, thereby potentially alleviating caregiver strain.

The health status of care recipients is concerning, with 88% having chronic diseases and 24.6% affected by dementia; this figure is higher than the overall prevalence of dementia (9%)51, probably because the sample only includes the older adults who need caregivers. These conditions place considerable physical and emotional demands on caregivers, highlighting the importance of interventions that support their physical and mental well-being to prevent burnout and enhance care quality.

Furthermore, financial challenges are pronounced, with a significant proportion of caregivers (44.3%) reporting a household income of less than 250 USD per month, which is well below the national poverty line and the minimum wage. Such a level of income significantly restricts access to healthcare and formal support systems, highlighting potential economic strain on families amid Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis52. More notably, the median IFDFW score was 25 (considered well below the expected average), suggesting high financial stress and low financial well-being39. Financial dependency of the care recipient is also a concern, with 37.5% being partially reliant on their caregivers for financial support53, reflecting the economic crisis in Lebanon that has exacerbated financial vulnerabilities, particularly among women and older adult populations. Taken together, these findings underscore the complex and multifaceted nature of older adults’ care in Lebanon, encompassing health, financial, and social dimensions that caregivers must address.

The burden of caregiving was higher when the care recipient was financially dependent on the caregiver, had dementia or chronic musculoskeletal conditions (reduced mobility), and was not able to socially integrate. Providing care for older adults with dementia or musculoskeletal pain could be both physically and emotionally demanding for family caregivers54,55. These findings align with previous research showing that caregivers of older adults with hip fractures often face a multidimensional burden55, and those caring for older adults with dementia also experience a heavy burden of psychological distress and depression56. The burden was also higher when the caregiver was older, lived in a remote region, was a part-time worker, had financial distress, was giving care for a longer period, had maladaptive coping strategies, had no help from an assistant, and had lower social support. These results are typically in line with those of other researchers30,31, they highlight the cumulative impact of Lebanon’s crises on caregiving, suggesting a “double burden” of caregiving coupled with economic strain57; participants experiencing financial distress and lacking support from a home assistant had multiple responsibilities and were culturally expected to fulfill the roles of caregiver, breadwinner, and emotional supporter58. Part-time workers reported higher levels of burden than full-time workers, possibly because they have more available time for caregiving tasks than the latter. The negative association found between subjective caregiver burden and social support is consistent with findings from a meta-analysis and a systematic review on informal caregivers of older adults22,25, both of which identified social support as a significant predictor of reduced subjective burden. Policy-level interventions targeting these stressors, such as financial assistance, social support networks, or respite care programs, could substantially reduce caregiver burden.

The coping maladaptive strategies’ role in reporting a higher burden from caregiving was expected, although this association was not previously studied in Lebanon or the Arab countries. The use of adaptive coping strategies was shown to help caregivers avoid becoming entangled in societal judgments and misconceptions in other populations (autistic children’s behaviors59), while maladaptive coping strategies may exacerbate stress and potentially increase feelings of burden60. Reducing maladaptive behaviors through appropriate caregiver training and support groups could be effective in the Lebanese context, helping caregivers manage stress more healthily61. Further research in Lebanon is nevertheless necessary to confirm this suggestion, in light of the Lebanese cultural, religious, and contextual specificities.

Strengths and limitations

Two notable strengths of this study are its broad sample representativeness and the use of validated scales, both of which enhance the validity of findings and reduce the risk of information bias. Using multivariable analysis techniques further lessens the possibility of confounding bias. The study has drawbacks, though. Its cross-sectional design makes it impossible to evaluate the causal links between dependent variables and participant characteristics. Furthermore, there is a risk of selection bias because the survey was distributed mostly through electronic platforms, especially given Lebanon’s patchy internet service. The distribution of the questionnaire across multiple social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram) may introduce sampling and participation biases. Since each platform attracts different user demographics and engagement patterns, and because the survey was more widely distributed or received more responses from certain platforms, the sample may not fully represent the broader target population. This may affect the generalizability of the findings, as the results may be disproportionately influenced by the characteristics of users from the more heavily represented platforms. Our study is also limited to Arab-language speakers, but we do not expect this bias to be high because the majority speaks Arabic. Moreover, the self-reported responses may introduce social desirability or recall bias, and the questionnaire’s length could have contributed to respondent weariness. This, in turn, may have led to non-differential information bias, potentially driving results toward the null and underestimating the findings. Further studies that consider these weaknesses are necessary to confirm the findings of the current study.

Public health implications

The results draw attention to important public health issues regarding caregiver stress in Lebanon. The intricate interactions between several elements that lead to elevated stress levels among caregivers emphasize the necessity of all-encompassing support networks and focused therapies. Public health measures must focus on three key areas: social integration, dementia and mobility management, and the financial independence of care recipients. The strain experienced by caregivers providing long-term care, those living in remote locations, or those of older age highlights the need for flexible caregiving support options and easily accessible and affordable respite care.

Moreover, the effects of financial hardship, made worse by Lebanon’s numerous crises, highlight how urgently caregivers need financial assistance and resources. Furthermore, the significance of social support, help, and adaptive coping techniques, emphasizes the possible advantages of caregiver education initiatives (psychoeducational programs, skills training, problem solving training, and stress management techniques) and community-based support systems.

Conclusion

This study showed that the financial difficulties of both the caregiver and the care recipient added up to the usual burden of caregiving. Given their critical position in healthcare systems and the societal expectations they encounter, public health initiatives should concentrate on reducing the various difficulties that caregivers bear, taking into account the economic and cultural context. Future research should explore interventions that incorporate culturally appropriate coping mechanisms, economic aid, and healthcare support for caregivers. Moreover, it is essential to conduct longitudinal studies to understand the long-term impact of the caregiving burden and evaluate the effectiveness of various support interventions.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADF-CS:

-

Autonomy in Daily Functioning-Contemporary Scale

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- Brief COPE-28:

-

Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- IFDFW:

-

InCharge Financial Distress-Financial Well-Being

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- INSPECT-LB:

-

Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Public Health, Clinical Epidemiology, and Toxicology—Lebanon

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- MDSPSS:

-

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- ZBI:

-

Zarit Burden Interview

References

Peiman, H., Yaghoubi, M., Seyed Mohammadi, A. & Delpishe, A. Prevalence of Chronic Diseases in the Elderly in Ilam. Iranian Journal of Ageing [Internet]. 2012 Jan 10 [cited 2024 Oct 31];6(4):7–13. Available from: http://salmandj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-470-en.html

United Nations, E. S. C. W. A. Building Forward Better for Older Persons in the Arab Region [Internet]. Beirut: United Nations; 120. Report No.: 9. (2022). p Available from: https://www.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/pubs/pdf/population-development-report-9-english_2.pdf

Hussein, S. & Ismail, M. Ageing and Elderly Care in the Arab Region: Policy Challenges and Opportunities. Ageing Int [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];42(3):274–89. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-016-9244-8

UNFPA-Lebanon. The rights and wellbeing of older persons in Lebanon [Internet]. UNFPA-Lebanon; 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.helpage.org/silo/files/ageing-in-the-arab-regionlebanonenglish.pdf

Abdulrahim, S., Ajrouch, K. J. & Antonucci, T. C. Aging in lebanon: challenges and opportunities. Gerontologist 55 (4), 511–518 (2015).

Sabbah, I., Vuitton, D. A., Droubi, N., Sabbah, S. & Mercier, M. Morbidity and associated factors in rural and urban populations of South Lebanon: a cross-sectional community-based study of self-reported health in 2000. Tropical Medicine & International Health [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2024 Oct 31];12(8):907–19. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01886.x

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dementia Caregiving as a Public Health Strategy [Internet]. Caregiving. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/caregiving/php/public-health-strategy/index.html

Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Czaja, S. J., Martire, L. M. & Monin, J. K. Volume 71,. Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Annual Review of Psychology [Internet]. 2020 Jan 4 [cited 2024 Oct 31];71:635–59. (2020). Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050754

Nassif, G. & Dakkak, S. Elder care in Lebanon: An analysis of care workers and care recipients in the face of crisis. IFPRI discussion papers [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 2]; (2023). Available from: https://ideas.repec.org//p/fpr/ifprid/2176.html

Kim, H., Chang, M., Rose, K. & Kim, S. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Oct 31];68(4):846–55. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x

Ferrara, M. et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in with Alzheimer caregivers. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes [Internet]. 2008 Nov 6 [cited 2024 Oct 31];6(1):93. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-93

Marinho, J. S. et al. DP. Burden, satisfaction caregiving, and family relations in informal caregivers of older adults. Front Med [Internet]. 2022 Dec 22 [cited 2024 Oct 31];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1059467/full

Haresabadi, M. et al. Assessing burden of family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia admitted in Imam Reza hospital- Bojnurd 2010. 2012 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];4(212):165–72. Available from: https://www.sid.ir/paper/186913/fa

Veenstra, C. Management of Cancer in the Older Patient. JAMA [Internet]. May 16 [cited 2024 Oct 31];307(19):2106–7. (2012). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.4814

McCullagh, E., Brigstocke, G., Donaldson, N. & Kalra, L. Determinants of Caregiving Burden and Quality of Life in Caregivers of Stroke Patients. Stroke [Internet]. 2005 Oct [cited 2024 Oct 31];36(10):2181–6. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000181755.23914.53

Muller-Kluits, N. & Slabbert, I. Caregiver burden as depicted by family caregivers of persons with physical disabilities. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk [Internet]. 2018 Oct 31 [cited 2024 Oct 31];54(4):493–493. Available from: https://socialwork.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/676

Liu, Z., Heffernan, C. & Tan, J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences [Internet]. 2020 Oct 10 [cited 2024 Oct 31];7(4):438–45. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352013220301216

Teahan, Á., Lafferty, A., Cullinan, J., Fealy, G. & O’Shea, E. An analysis of carer burden among family carers of people with and without dementia in Ireland. International Psychogeriatrics [Internet]. 2021 Apr [cited 2024 Oct 31];33(4):347–58. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-psychogeriatrics/article/abs/an-analysis-of-carer-burden-among-family-carers-of-people-with-and-without-dementia-in-ireland/BDB2A57C58745807E38F1719766EDA44

Ku, L. J. E., Chang, S. M., Pai, M. C. & Hsieh, H. M. Predictors of caregiver burden and care costs for older persons with dementia in Taiwan. International Psychogeriatrics [Internet]. 2019 Jun [cited 2024 Oct 31];31(6):885–94. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-psychogeriatrics/article/abs/predictors-of-caregiver-burden-and-care-costs-for-older-persons-with-dementia-in-taiwan/C99440354E239A78DCC1A2633BBC20EE

Tulek, Z. et al. Caregiver Burden, Quality of Life and Related Factors in Family Caregivers of Dementia Patients in Turkey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing [Internet]. 2020 Aug 2 [cited 2024 Oct 31]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1705945

Liew, T. M., Tai, B. C., Yap, P. & Koh, G. C. H. Contrasting the risk factors of grief and burden in caregivers of persons with dementia: Multivariate analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Oct 31];34(2):258–64. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5014

Choi, J. Y., Lee, S. H. & Yu, S. Exploring Factors Influencing Caregiver Burden: A Systematic Review of Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Chronic Illness in Local Communities. Healthcare [Internet]. 2024 Jan [cited 2024 Oct 31];12(10):1002. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/12/10/1002

Lucijanić, J. et al. A validation of the Croatian version of Zarit Burden Interview and clinical predictors of caregiver burden in informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a cross-sectional study. Croatian Medical Journal [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2024 Oct 31];61(6):527. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7821365/

Ruisoto, P. et al. Mediating effect of social support on the relationship between resilience and burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics [Internet]. Jan 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];86:103952. (2020). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167494319301955

del-Pino-Casado, R., Frías-Osuna, A., Palomino-Moral, P. A., Ruzafa-Martínez, M. & Ramos-Morcillo, A. J. Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2018 Jan 2 [cited 2024 Oct 31];13(1):e0189874. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0189874

Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J. & Skaff, M. M. Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures1. The Gerontologist [Internet]. 1990 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];30(5):583–94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

George, L. K., Gwyther, L. P. & Caregiver Weil-Being A Multidimensional Examination of Family Caregivers of Demented Adults1. The Gerontologist [Internet]. Jun 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];26(3):253–9. (1986). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/26.3.253

Huang, M. F. et al. Coping Strategy and Caregiver Burden Among Caregivers of Patients With Dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen [Internet]. 2015 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];30(7):694–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513494446

Iavarone, A., Ziello, A. R., Pastore, F., Fasanaro, A. M. & Poderico, C. Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. NDT [Internet]. Jul 29 [cited 2024 Oct 31];10:1407–13. (2014). Available from: https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S58063

Chaaya, M. et al. and family burden of care in Lebanon. BJPsych International [Internet]. 2017 Feb [cited 2024 Oct 31];14(1):7–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-international/article/dementia-and-family-burden-of-care-in-lebanon/5F12E0E26BF235E38040723B8313FEAA

Séoud, J. et al. The health of family caregivers of older impaired persons in Lebanon: An interview survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies [Internet]. 2007 Feb 1 [cited 2024 Oct 31];44(2):259–72. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020748905002567

Abou Mrad, Z. et al. The Difference in Burden Experienced by Male and Female Caregivers of Dementia Patients in Lebanon: A Cross-Sectional Study [Internet]. Research Square; [cited 2024 Oct 31]. (2022). Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1166948/v1

Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E. & Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. The Gerontologist [Internet]. 1980 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Nov 2];20(6):649–55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/20.6.649

Pinyopornpanish, K. et al. Investigating psychometric properties of the Thai version of the Zarit Burden Interview using rasch model and confirmatory factor analysis. BMC Research Notes [Internet]. 2020 Mar 2 [cited 2024 Nov 2];13(1):120. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-04967-w

Official, Z. B. I. The Zarit Burden Interview [Internet]. ePROVIDE - Mapi Research Trust. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 2]. Available from: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/zarit-burden-interview

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of Illness in the Aged: The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA [Internet]. 1963 Sep 21 [cited 2024 Sep 1];185(12):914–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

Nasser, R. & Doumit, J. Validity and reliability of the Arabic version of Activities of Daily Living (ADL). BMC Geriatrics [Internet]. Mar 29 [cited 2024 Sep 1];9(1):11. (2009). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-9-11

Prawitz, A. D. et al. Incharge financial distress/financial Well-Being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J. Financial Couns. Plann. 17 (1), 34–50 (2006).

Sacre, H. et al. Development and validation of the Socioeconomic Status Composite Scale (SES-C). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Aug 24 [cited 2024 Jan 4];23(1):1619. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16531-9

Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med [Internet]. 1997 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Nov 2];4(1):92–100. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Kasi, P. M. et al. Coping Styles in Patients with Anxiety and Depression. International Scholarly Research Notices [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Nov 2];2012(1):128672. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/128672

Alghamdi, M. Cross-cultural validation and psychometric properties of the Arabic brief COPE in Saudi population. Med. J. Malaysia. 75 (5), 502–509 (2020).

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment [Internet]. 1988 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Nov 2];52(1):30–41. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the multidimensional social support scale (MSPSS) in a community sample of adults. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. Jun 14 [cited 2024 Nov 2];23(1):432. (2023). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04937-z

Heinze, G. & Dunkler, D. Five myths about variable selection. Transplant International [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Apr 18];30(1):6–10. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/tri.12895

Williams, J. R. The Declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bull World Health Organ [Internet]. 2008 Aug [cited 2024 Sep 1];86(8):650–2. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2649471/

Abdelmoneium, A. O. & Alharahsheh, S. T. Family Home Caregivers for Old Persons in the Arab Region: Perceived Challenges and Policy Implications. Open Journal of Social Sciences [Internet]. Jan 14 [cited 2024 Nov 2];4(1):151–64. (2016). Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=63222

Alshammari, S. A. et al. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2024 Nov 2];24(3):145. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jfcm/fulltext/2017/24030/the_burden_perceived_by_informal_caregivers_of_the.1.aspx

Salama, R. A. A. & El-Soud, F. A. A. Caregiver burden from caring for impaired elderly: a cross-sectional study in rural Lower Egypt. Italian Journal of Public Health [Internet]. Dec 31 [cited 2024 Nov 2];9(4). (2012). Available from: https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/ijphjournal/article/view/22692

UNDP and CAS. The Life of Women and Men in Lebanon: A Statistical Portrait [Internet]. Lebanon: The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) of Lebanon. 62. (2021). p Available from: http://www.cas.gov.lb/images/PDFs/Gender_statistics/GENDER_EQUALITY_IN_LEBANON_REPORT.pdf

Phung, K. T. T. et al. Dementia prevalence, care arrangement, and access to care in Lebanon: A pilot study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2024 Nov 2];13(12):1317–26. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.04.007

Corriero, A. C., Aborode, A. T., Reggio, M. & Shatila, N. The impact of COVID-19 and the economic crisis on Lebanese public health: Food insecurity and healthcare disintegration. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Mar 25];24:100802. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352552522000512

Salti, N. & Mezher, N. Women on the Verge of an Economic Breakdown: Assessing the differential impacts of the economic crisis on women in Lebanon [Internet]. Lebanon: UN Women; Sep p. 20. (2020). Available from: https://arabstates.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20Arab%20States/Attachments/Publications/2020/10/Lebanons%20Economic%20Report%20Updated%201110%20FH.pdf

Wang, L., Zhou, Y., Fang, X. & Qu, G. Care burden on family caregivers of patients with dementia and affecting factors in China: A systematic review. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Apr 18];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.orghttps://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1004552/full

Lu, N., Liu, J. & Lou, V. W. Q. Caring for frail elders with musculoskeletal conditions and family caregivers’ subjective well-being: The role of multidimensional caregiver burden. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics [Internet]. Nov 1 [cited 2025 Apr 18];61(3):411–8. (2015). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167494315300285

Gumikiriza-Onoria, J. L. et al. Psychological distress among family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Uganda. BMC Geriatrics [Internet]. 2024 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Apr 18];24(1):602. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05190-z

Human Rights Watch & Lebanon Events of 2022. In: World Report 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/lebanon

Dumit, N. Y., Abboud, S., Massouh, A. & Magilvy, J. K. Role of the Lebanese family caregivers in cardiac self-care: a collective approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 2];24(21–22):3318–26. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ (2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12949

Salami, S. & Alhalal, E. Affiliate Stigma Among Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Role of Coping Strategies and Perceived Social Support. Journal of Disability Research [Internet]. 2024 Feb 20 [cited 2024 Nov 2];3:20240009. Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.57197/JDR-2024-0009

Muro Pérez-Aradros, C., Navarro-Prados, A. B., Satorres, E., Serra, E. & Meléndez, J. C. Coping and guilt in informal caregivers: a predictive model based on structural equations. Psychology, Health & Medicine [Internet]. 2023 Apr 21 [cited 2024 Nov 2];28(4):819–30. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2029917

Merlo, E. M., Stoian, A. P., Motofei, I. G. & Settineri, S. Clinical Psychological Figures in Healthcare Professionals: Resilience and Maladjustment as the Cost of Care. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Nov 2];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607783/full

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all caregivers who participated in this study.

Funding

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA developed the project idea. SK, CH, CBM, and ZB further developed the questionnaire. ZB performed the literature review, formulated the questionnaire, collected and analyzed the data, and organized and drafted the paper. SR, PS, MB, and LAA supervised the project. AH, RMZ, SR, MB, LAA, and HS critically read the article and gave their comments. PS oversaw the project from its inception until the manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barakat, Z., Sacre, H., Khatib, S. et al. Examining burden among caregivers of community-dwelling older adults in Lebanon. Sci Rep 15, 22775 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05626-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05626-5