Abstract

As societies age, understanding the impact of comorbidities on postoperative outcomes following hip fracture surgery becomes increasingly critical. This single-center retrospective study examines the evolving risk factors for postoperative mortality following hip fracture surgery among older adults in Taiwan during its transition to an aged society. We analyzed data from 1,545 patients aged over 65 years who underwent hip fracture surgery at Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital between 2011 and 2020, comparing outcomes before and after 2018—the year Taiwan officially became an aged society. The overall one-year postoperative mortality rate was 6.0%. Significant predictors of increased mortality included advanced age, male sex, ORIF surgical approach, hepatic disease, coronary artery disease, and notably, in-hospital complications such as aspiration pneumonia and UGI bleeding. Our findings revealed that aspiration pneumonia’s impact on mortality intensified significantly in the post-2018 period, highlighting the changing risk profile as Taiwan’s population ages. This study provides critical insights for developing targeted interventions and specialized postoperative care protocols for elderly hip fracture patients, particularly focusing on respiratory care and dysphagia screening. These findings have important implications for healthcare systems adapting to demographic shifts toward super-aged societies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hip fractures are among the most common orthopedic injuries in older individuals, causing considerable physical and economic burdens1. The incidence of hip fractures in Taiwan was previously reported to be among the highest in the world2. However, recent research has suggested that the incidence of hip fractures in Taiwan has been steadily decreasing since 20032,3, possibly owing to the early diagnosis and effective treatment of osteoporosis4. Nevertheless, postoperative complications after hip fractures remain a concern. Several studies have demonstrated the association between mortality and postoperative complications such as aspiration pneumonia, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding, and urinary tract infections (UTI)5,6,7. Risk factors for these complications have also been adequately studied5,6,7,8,9.

Although hip fractures have become less prevalent in recent years and although the risk factors for hip fractures are well known, Taiwan’s population remains vulnerable to hip fractures and to complications following hip fracture surgery because Taiwan is an aging society. According to the National Development Council of Taiwan, the percentage of older adults in the population exceeded 14% in 2018; the percentage is expected to exceed 20% by 2025, making Taiwan a super-aged society (https://www.ndc.gov.tw/en/Content_List.aspx?n=85E9B2CDF4406753). The impact of an aging society extends beyond the clinical management of hip fractures to broader issues such as healthcare resource allocation, development of age-appropriate medical protocols, and the integration of multidisciplinary care teams to address the complex needs of elderly patients. Given the projected increase in the elderly population, research focusing on these aspects is vital for preparing healthcare systems to meet the demands of an aging society effectively.

The objectives of the present study were to compare and observe the correlations of the demographics, the comorbidities, the in-hospital complications and the 1-year mortality rates between the two groups: a group receiving surgical intervention before January 1, 2018 (as ageing society), and that receiving such intervention after January 1, 2018 (as aged society). By analyzing data spanning a decade, we seek to identify trends and predictors of mortality, providing insights that can inform clinical practice and healthcare policy in the context of an aging population. This research may contribute to the growing body of knowledge required to adapt medical care for the challenges posed by demographic changes, ultimately aiming to improve outcomes for older adults suffering from hip fractures.

Materials and methods

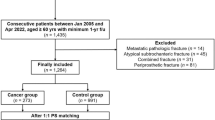

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in full compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (approval number: IRB108-207-C). Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of de-identified data, the Research Ethics Committee of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation waived the requirement for informed consent. We analyzed data from patients aged 65 years and older who underwent orthopedic surgery for hip fractures at our institution between January 2011 and December 2020. All patient information was anonymized prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 65 years or older and had undergone surgical treatment for traumatic hip fractures, including femoral neck fractures, intertrochanteric fractures, and subtrochanteric fractures. We excluded patients with pathological fractures secondary to malignancy, periprosthetic fractures, fractures resulting from high-energy trauma (such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights), patients who were treated non-operatively, and those with incomplete medical records or who were lost to follow-up within the one-year postoperative period. Additionally, patients who died during the index hospitalization due to causes unrelated to the hip fracture or its surgical management were excluded from the analysis of one-year mortality.

We examined the patients’ medical records to monitor the occurrence of postoperative complications. Patient baseline characteristics and clinical data were collected from our institution’s database, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), operation date (before or after January 1, 2018), anesthesia method (general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia), surgical method (open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) or hemiarthroplasty), preoperative comorbidities (e.g., hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia, hepatic diseases, chronic kidney disease (CKD), coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), gastrointestinal (GI) diseases, and chronic lung disease (CLD)), and in-hospital postoperative complications (e.g., aspiration pneumonia, UTI, and UGI bleeding). The study outcome was 1-year postoperative mortality, and analyses were conducted to determine the related risk factors. Information on 1-year postoperative mortality was obtained through a combination of our hospital’s electronic medical record system, the National Health Insurance Database, and telephone follow-up interviews with patients or their family members when necessary. For patients who continued follow-up at our institution, mortality data was directly available from medical records. For those who did not return for scheduled follow-ups, we cross-referenced with the National Death Registry database through our hospital’s connection to the National Health Insurance system. In cases where electronic verification was not possible, research staff conducted telephone interviews with patients or their designated contacts. Initially, 1,587 patients met our inclusion criteria; however, we were unable to obtain reliable 1-year mortality data for 42 patients (2.6%) who were lost to follow-up due to relocation outside Taiwan or lack of response to telephone follow-up attempts. These patients were excluded from the final analysis, resulting in a study population of 1,545 patients.

All patients who underwent hip fracture surgery received standardized postoperative care according to our institution’s protocol. This comprehensive care plan included early mobilization initiated within 24–48 h postoperatively as tolerated by the patient’s condition. Pain management was administered through multimodal analgesia with regular assessment using visual analog scales. Prophylactic measures against common complications included deep vein thrombosis prevention (mechanical and/or pharmacological based on individual risk assessment), pneumonia prevention strategies (incentive spirometry, proper positioning, and pulmonary hygiene), and pressure ulcer prevention protocols. Nutritional support was provided with protein supplementation as needed, particularly for patients with low BMI or malnutrition risk. A multidisciplinary team comprising orthopedic surgeons, geriatricians, physical therapists, and nutritionists coordinated patient care throughout hospitalization. Discharge planning was initiated early during hospitalization with arrangements for appropriate rehabilitation services based on individual functional status and social support systems.

An independent-samples t-test was used to compare the demographic data of patients who received hip fracture surgery before January 1, 2018 (i.e., the “Pre-Aged Society Group” (PRASG)) with those of patients who received hip fracture surgery after January 1, 2018 (i.e., the “Post-Aged Society Group” (POASG)). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between 1-year postoperative mortality and relevant risk factors. Odds ratios (ORs) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived for each variable. We conducted subgroup analyses to verify the association between the risk factors and 1-year postoperative mortality by stratifying the patients into groups according to the date of hip fracture surgery (i.e., before or after January 1, 2018). All reported p-values were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were assessed for normal distribution. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (version 23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Sample size calculation: The aim of our study is to examine related factors associated with 1-year postoperative mortality among older adults following hip fracture surgery in Taiwan. We set the number of covariates as 15, events per variable as 10 and assume the prevalence of 1-year postoperative mortality as 10%. The is sample size needed would be 1500 (= 15*10/0.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1,545 patients who underwent hip fracture surgery were included in this study, with 663 patients in Period 1 (2010–2017) (PRASG) and 882 patients in Period 2 (2018–2022) (POASG) (Table 1). The mean age of the entire cohort was 78.84 ± 9.20 years, with no significant difference between the two periods (78.82 ± 9.12 vs. 78.85 ± 9.27 years, p = 0.956). The majority of patients were female (65.2%), with a similar gender distribution across both periods (p = 0.962). The mean BMI was 23.60 ± 4.94 kg/m², with a trend toward lower BMI in Period 2 that did not reach statistical significance (23.87 ± 5.05 vs. 23.40 ± 4.85 kg/m², p = 0.067). There was a significant change in surgical methods between the two periods (p < 0.001). The use of ORIF with CHS decreased markedly from Period 1 to Period 2 (21.4–3.1%), while ORIF with intramedullary nailing increased substantially (43.7–61.1%). The proportion of hemiarthroplasty procedures remained relatively stable (34.8–35.8%). The majority of patients (79.6%) underwent surgery within 48 h of admission, with no significant difference in surgical timing between periods (p = 0.36) (Table 1). Regarding perioperative risk factors, 36.6% of patients were classified as ASA III-IV, with a non-significant trend toward lower proportions of high-risk patients in Period 2 (38.9% vs. 34.9%, p = 0.107). Spinal anesthesia was used in approximately one-third of cases (33.7%), with similar rates across both periods (p = 0.698). The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (68.9%), diabetes mellitus (39.6%), dyslipidemia (39.4%), and gastrointestinal disease (37.9%), with no significant differences between periods. There was a non-significant trend toward higher prevalence of cerebrovascular disease in Period 2 (22.5% vs. 26.5%, p = 0.068). The prevalence of dementia was 14.5% overall, with a slight but non-significant increase from Period 1 to Period 2 (13.3% vs. 15.4%, p = 0.236). In-hospital complications included UTI (11.3%), UGI bleeding (4.0%), and aspiration pneumonia (1.9%), with similar rates across both periods. The overall one-year postoperative mortality rate was 6.0%, with no significant difference between Period 1 and Period 2 (6.5% vs. 5.6%, p = 0.444) (Table 1).

Factors associated with 1-year postoperative mortality

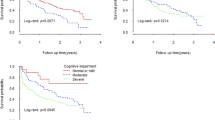

In the univariable analysis, several factors were significantly associated with increased one-year mortality: advanced age (OR: 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.06, p = 0.002), male gender (OR: 1.78, 95% CI 1.17–2.73, p = 0.007), ORIF with nail compared to hemiarthroplasty (OR: 1.95, 95% CI 1.17–3.25, p = 0.010), dyslipidemia (OR: 1.82, 95% CI 1.19–2.77, p = 0.006), hepatic disease (OR: 1.94, 95% CI 1.13–3.33, p = 0.016), chronic renal failure (OR: 2.49, 95% CI 1.61–3.86, p < 0.001), coronary artery disease (OR: 2.11, 95% CI 1.35–3.28, p = 0.001), cerebrovascular disease (OR: 1.85, 95% CI 1.19–2.88, p = 0.006), gastrointestinal disease (OR: 1.95, 95% CI 1.28–2.98, p = 0.002), aspiration pneumonia (OR: 8.74, 95% CI 3.96–19.27, p < 0.001), and UGI bleeding (OR: 7.09, 95% CI 3.88–12.98, p < 0.001). Lower BMI was associated with increased mortality (OR: 0.94, 95% CI 0.89–0.99, p = 0.014) (Table 2). After adjusting for potential confounders in the multivariable analysis, the factors that remained significantly associated with one-year mortality were lower BMI (OR: 0.95, 95% CI 0.90–0.99, p = 0.048), ORIF with nail compared to hemiarthroplasty (OR: 2.37, 95% CI 1.37–4.12, p = 0.002), hepatic disease (OR: 1.88, 95% CI 1.03–3.44, p = 0.041), aspiration pneumonia (OR: 4.87, 95% CI 1.92–12.34, p = 0.001), and UGI bleeding (OR: 5.03, 95% CI 2.54–9.96, p < 0.001). Age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.06, p = 0.054), male gender (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.98–2.53, p = 0.059), coronary artery disease (OR: 1.61, 95% CI 0.97–2.69, p = 0.066), and cerebrovascular disease (OR: 1.57, 95% CI 0.96–2.58, p = 0.075) showed borderline significance (Table 2).

Period-stratified analysis of mortality risk factors

When stratifying the analysis by period, we observed both similarities and differences in mortality risk factors between Period 1 (2010–2017) (PRASG) and Period 2 (2018–2022) (POASG). In the multivariable analysis for PRASG, significant predictors of one-year mortality included ORIF with nail compared to hemiarthroplasty (OR: 3.42, 95% CI 1.41–8.34, p = 0.007), hepatic disease (OR: 2.98, 95% CI 1.26–7.08, p = 0.013), aspiration pneumonia (OR: 5.85, 95% CI 1.25–27.46, p = 0.025), and UGI bleeding (OR: 6.72, 95% CI 1.93–23.34, p = 0.003) (Table 3). In POASG, the significant predictors in the multivariable analysis were advanced age (OR: 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.10, p = 0.017), coronary artery disease (OR: 2.40, 95% CI 1.20–4.80, p = 0.013), aspiration pneumonia (OR: 6.06, 95% CI 1.71–21.49, p = 0.005), and UGI bleeding (OR: 4.71, 95% CI 1.96–11.28, p = 0.001). Male gender (OR: 1.76, 95% CI 0.91–3.41, p = 0.091), ORIF with nail (OR: 1.98, 95% CI 0.96–4.09, p = 0.063), and cerebrovascular disease (OR: 1.86, 95% CI 0.95–3.62, p = 0.069) showed borderline significance. Notable differences between periods included the emergence of age as a significant predictor in POASG but not in PRASG, and the significant impact of hepatic disease in PRASG but not in POASG. Coronary artery disease became a significant predictor in POASG (OR: 2.40, 95% CI 1.20–4.80, p = 0.013) but was not significant in PRASG (OR: 1.00, 95% CI 0.45–2.24, p = 0.997). The impact of surgical delay (> 48 h) showed a non-significant trend toward increased mortality in PRASG (OR: 1.86, 95% CI 0.86–4.04, p = 0.118) but not in POASG (OR: 0.59, 95% CI 0.25–1.39, p = 0.225). Similarly, UTI was associated with a non-significant trend toward increased mortality in PRASG (OR: 2.16, 95% CI 0.87–5.36, p = 0.097) but not in POASG (OR: 1.04, 95% CI 0.42–2.56, p = 0.927). Both aspiration pneumonia and UGI bleeding remained strong predictors of mortality across both periods, with comparable effect sizes. The point estimate for aspiration pneumonia was slightly higher in POASG (OR: 6.06 vs. 5.85), while the point estimate for UGI bleeding was higher in PRASG (OR: 6.72 vs. 4.71), though these differences were not statistically tested for interaction.

Discussion

Demographic factors and comorbidities in patients with hip fractures

Our study, as outlined in Table 1, showed that the POASG had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including HTN, DM, hepatic diseases, and CVAs, compared to the PRASG. This rise in comorbidities might be linked to advancements in medical care that have enabled earlier diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases. Despite the increased burden of comorbidities in the POASG group, the 1-year postoperative mortality rate was similar to that of the PRASG. This stability in mortality rates could be attributed to improvements in surgical techniques, anesthesia, and rehabilitation protocols, which have enhanced patient outcomes10,11. In Table 2, our study identified several nonmodifiable risk factors associated with elevated 1-year postoperative mortality, including advanced age, male sex, ORIF treatment, hepatic diseases, and CAD, consistent with findings from other studies12,13,14. These results highlight the necessity for personalized care for patients with these risk factors. Subgroup analysis results in Table 3 indicate significant associations between ORIF treatment, low BMI, and dyslipidemia with increased 1-year postoperative mortality in the PRASG; conversely, male sex, ORIF treatment, and CAD were significantly linked to increased mortality in the POASG. The association of male sex with higher mortality, particularly in the POASG, could be related to the aging Taiwanese population, impacting the quality of care and increasing the likelihood of complications such as infection15. Lower BMI was significantly associated with a higher 1-year postoperative mortality rate in the PRASG but not in the POASG, as shown in Table 3. This shift in the impact of BMI on surgical outcomes suggests evolving health profiles in the elderly and the need for adaptable BMI assessment approaches16,17. Dyslipidemia’s link with higher mortality in the POASG, but not in the PRASG, points to a complex relationship between lipid levels and mortality, highlighting the need for further research in this area18,19. Finally, CAD emerged as a risk factor for 1-year postoperative mortality in the POASG, underscoring the need for evolving clinical strategies to manage CAD in perioperative care.

In-hospital aspiration pneumonia and 1-year postoperative mortality

As illustrated in Table 1, although the prevalence of aspiration pneumonia and 1-year postoperative mortality was similar in both the PRASG and POASG, a significant disparity was observed in the association between aspiration pneumonia and mortality. Notably, in the POASG, the adjusted OR for 1-year postoperative mortality was significantly higher. This divergence suggests that after 2018, following Taiwan’s transition to an aged society, the clinical implications of aspiration pneumonia in hip fracture patients have intensified. The change could be attributed to a combination of factors including an increase in age-related physiological vulnerabilities, such as diminished swallowing reflexes and reduced mobility, and an escalation in comorbid conditions in an older patient population20,21. The demographic shift towards an older society has evidently introduced new challenges in geriatric care, emphasizing the need for healthcare systems to evolve in response to these changes. Specifically, there is a pressing requirement to enhance the focus on preventing and effectively managing complications like aspiration pneumonia, particularly in the more recently treated patient cohort22. The results reflect the need for healthcare systems to adapt to the changing needs of an aging population, with a focus on preventing and managing complications like aspiration pneumonia more effectively in the POASG cohort.

Another critical aspect that warrants attention is the growing challenge of nursing workforce shortages, which has become a global issue with multifaceted causes. Research has indicated that a higher ratio of professional nurses is correlated with improved patient outcomes23. The incidence of aspiration pneumonia is known to be higher in settings where there is inadequate assistance with feeding, poor monitoring of swallowing difficulties, or insufficient attention to respiratory care - issues that can arise from a strained caregiver system24. The introduction of less qualified assistive personnel in place of professional nurses might lead to preventable mortalities and a decline in the quality of care. In Taiwan, the shortage of nurses has been escalating, as reported by Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare, with a deficiency rising from 1186 in 2018 to 3875 in 202225. This shortage in the nursing workforce could potentially explain the observed increase in aspiration-pneumonia-associated mortality after 2018. The lack of adequate professional nursing care in medical centers may compromise the management of postoperative complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, thereby impacting the mortality rates among this vulnerable patient population. These findings highlight the necessity for healthcare systems to address the evolving healthcare needs through enhanced pulmonary complication management and by addressing staffing challenges in the nursing sector. This approach is crucial for improving postoperative outcomes in elderly patients with hip fracture.

In-hospital UGI bleeding and 1-year postoperative mortality

In our study, we observed that UGI bleeding significantly increased postoperative mortality in both the PRASG and the POASG, despite a slight decrease in its incidence after 2018. This finding aligns with existing literature, where the incidence of postoperative UGI bleeding in similar patient cohorts is reported around 4%, and its association with high mortality rates is well-documented6,26. The consistent OR across both time periods underscores the severity of UGI bleeding as a complication, which remains a critical challenge in postoperative management despite medical advancements27. Our analysis suggests that the high mortality rate associated with UGI bleeding, despite its relatively lower incidence, is due to the complication’s severity and the difficulty in effectively managing it in a geriatric population. To address this, a comprehensive approach encompassing preoperative risk assessment, modifications like managing anticoagulation therapy, use of gastroprotective agents, vigilant postoperative monitoring, prompt intervention, and enhanced healthcare professional training is essential in reducing mortality associated with UGI bleeding in geriatric hip fracture patients28,29.

The “obesity paradox” in hip fracture mortality

The seemingly counterintuitive relationship between lower BMI and higher mortality following hip fracture surgery can be explained through several key mechanisms that parallel observations in other medical conditions. Lower BMI in elderly hip fracture patients often indicates underlying frailty, malnutrition, and reduced physiological reserves—all critical factors that compromise recovery from major surgical interventions. This relationship exemplifies what has been termed the “obesity paradox,” where moderate overweight status may actually confer survival advantages in certain clinical scenarios. Several mechanisms explain this association: patients with lower BMI frequently exhibit reduced muscle mass (sarcopenia) and nutritional deficiencies, limiting their capacity to withstand the metabolic demands of surgical recovery and rehabilitation, with cachexia associated with one-year mortality rates ranging from 20–40%30; higher BMI patients may possess greater metabolic reserves to withstand the catabolic stress response triggered by fracture and surgery; and extremely low BMI often signals pre-existing chronic illness or advanced age-related physiological decline. Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that while obesity increases fracture risk, moderate obesity (BMI < 35 kg/m2) may paradoxically provide protective effects during recovery31 through enhanced energy reserves and potentially beneficial adipokine profiles. Observational studies have consistently shown that sarcopenia and frailty independently associate with higher rates of adverse outcomes, with the coexistence of multiple frailty domains significantly amplifying the risk of one‐year mortality or readmission32suggesting that nutritional optimization and targeted rehabilitation strategies may be particularly important for lower BMI patients in the perioperative period.

Healthcare delivery changes and social factors influencing outcomes

The interpretation of our hip fracture outcomes must account for both healthcare delivery evolution and changing social conditions. Although we did not directly measure workforce numbers, institutional protocols and organizational structures significantly impact hip fracture care delivery and outcomes33. Despite global reports of surgical delays during COVID-19, our institution maintained consistent surgical timing with 79.6% of patients undergoing surgery within 48 h across both periods, aligning with observations from high-volume centers where operative timing remained largely stable under pandemic protocols34. Broader service-level enhancements likely contributed to outcome trends, including orthogeriatric co-management models associated with reduced complications and improved functional recovery35,36and early surgery combined with prompt geriatric assessment37. Our data reveals a significant shift in surgical methods between periods, with a marked decrease in compression hip screw usage (21.4–3.1%) and an increase in intramedullary nailing (43.7–61.1%), reflecting evolving surgical preferences that align with systematic reviews documenting advantages for intramedullary implants in unstable trochanteric fractures38,39. Additionally, observed trends in patient characteristics, such as slightly lower BMI in Period 2, may reflect enhanced preoperative optimization protocols that can affect both intraoperative risk and postoperative recovery37. Contextualizing our findings requires acknowledging the interplay of service organization, pandemic-related adaptations, multidisciplinary care models, surgical technique evolution, and patient optimization strategies in Taiwan’s transition to an aged society.

Strength and limitations

The current study has several strengths. First, our cohort study is the first to compare several factors associated with 1-year postoperative mortality in the aging population of Taiwan from 2010 to 2022. Second, our study included a large sample size of 1545 patients. Third, our study contributes to the understanding of the risks of mortality associated with hip fracture surgery in older Taiwanese individuals as the Taiwanese populace continues to age.

Despite its strengths, our study is not without limitations, and its findings should thus be interpreted with caution. First, we applied a retrospective design, which may have limited the study findings. Because the data were not collected specifically for this study, significant gaps existed in the data set, including patients’ baseline medications and baseline activities of daily living at hospital admission. Second, because only in-hospital data were accessible, complications occurring after discharge were not considered; therefore, our study likely underestimated the incidence of complications such as aspiration pneumonia and UGI bleeding. Third, retrospective single-centered study designs have limited external validity and may exhibit selection bias, limiting their generalizability to a broader population. Fourth, because the present study spanned 13 years, different people were involved at different times in patient care and data entry; this heterogeneity in record keeping and patient care may negatively affect the validity of our conclusions. We acknowledge the statistical limitations in our study, particularly the wide confidence interval (95% CI of 4.01 to 28.31) observed for some of our risk factors. This wide range indicates considerable uncertainty in the precision of our effect size estimates. This imprecision likely stems from the relatively small number of events in certain subgroups within our single-center dataset. In addition, due to the observational nature of the study, we could not control the distribution of each covariate. The low prevalence of in-hospital complications, such as aspiration pneumonia and UGI bleeding, may have contributed to wide confidence intervals. While our findings identify important associations between risk factors and mortality, the magnitude of these effects should be interpreted cautiously. Future multi-center studies with larger sample sizes would help narrow these confidence intervals and provide more precise effect estimates. Additionally, our statistical approach was constrained by the retrospective nature of our data collection and the inherent limitations of hospital-based records. These statistical limitations underscore the need for our results to be validated in larger, prospective cohorts before definitive clinical recommendations can be made.

Despite these limitations, this study still provides valuable insights into the changing patterns of mortality risk factors for hip fracture patients in the context of Taiwan’s demographic transition to an aged society, and offers important clinical implications for improving postoperative care strategies in this vulnerable population.

Conclusions

This study reveals critical factors influencing one-year mortality following hip fracture surgery in Taiwan’s transition to an aged society, including advanced age, male sex, ORIF approach, hepatic disease, coronary artery disease, and notably, in-hospital complications like aspiration pneumonia and UGI bleeding. Despite methodological limitations, our findings highlight the need for targeted preventive strategies, enhanced postoperative monitoring, and comprehensive dysphagia screening for elderly patients. As Taiwan approaches super-aged society status by 2025, these insights contribute to developing multidisciplinary approaches addressing both surgical needs and complex medical challenges in this vulnerable population, ultimately improving outcomes in postoperative hip fracture care.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dong, Y. et al. What was the epidemiology and global burden of disease of hip fractures from 1990 to 2019? Results from and additional analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 481 (6), 1209–1220 (2023).

Sing, C. W. et al. Global epidemiology of hip fractures: secular trends in incidence rate, Post-Fracture treatment, and All-Cause mortality. J. Bone Min. Res. 38 (8), 1064–1075 (2023).

Wu, T. Y. et al. Trends in hip fracture rates in taiwan: a nationwide study from 1996 to 2010. Osteoporos. Int. 28 (2), 653–665 (2017).

Lee, M. T. et al. Epidemiology and clinical impact of osteoporosis in taiwan: A 12-year trend of a nationwide population-based study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 122 (Suppl 1), S21–S35 (2023).

Byun, S. E., Shon, H. C., Kim, J. W., Kim, H. K. & Sim, Y. Risk factors and prognostic implications of aspiration pneumonia in older hip fracture patients: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19 (2), 119–123 (2019).

Fisher, L., Fisher, A., Pavli, P. & Davis, M. Perioperative acute upper Gastrointestinal haemorrhage in older patients with hip fracture: incidence, risk factors and prevention. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (3), 297–308 (2007).

Pollmann, C. T., Dahl, F. A., Røtterud, J. H. M., Gjertsen, J. E. & Årøen, A. Surgical site infection after hip fracture – mortality and risk factors: an observational cohort study of 1,709 patients. Acta Orthop. 91 (3), 347–352 (2020).

Flikweert, E. R. et al. Complications after hip fracture surgery: are they preventable? Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 44 (4), 573–580 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Factors affecting the incidence of surgical site infection after geriatric hip fracture surgery: a retrospective multicenter study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 14 (1), 382 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Trends in comorbidities and postoperative complications of geriatric hip fracture patients from 2000 to 2019: results from a hip fracture cohort in a tertiary hospital. Orthop. Surg. 13 (6), 1890–1898 (2021).

Langmore, S. E., Skarupski, K. A., Park, P. S. & Fries, B. E. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents. Dysphagia 17 (4), 298–307 (2002).

Yong, E. L. et al. Risk factors and trends associated with mortality among adults with hip fracture in Singapore. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 (2), e1919706 (2020).

Kilci, O. et al. Postoperative Mortality after Hip Fracture Surgery: A 3 Years Follow Up. PLoS One 11(10), e0162097 (2016).

Tsai, C. H., Lin, C. L., Hsu, H. C. & Chung, W. S. Increased risk of coronary heart disease in patients with hip fracture: a nationwide cohort study. Osteoporos. Int. 26 (6), 1849–1855 (2015).

Schulz, R., Beach, S. R., Czaja, S. J., Martire, L. M. & Monin, J. K. Family caregiving for older adults. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71, 635–659 (2020).

Yang, T. I., Chen, Y. H., Chiang, M. H., Kuo, Y. J. & Chen, Y. P. Inverse relation of body weight with short-term and long-term mortality following hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17 (1), 249 (2022).

Kuzuya, M. Nutritional status related to poor health outcomes in older people: which is better, obese or lean? Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 21 (1), 5–13 (2021).

Zhao, Z., Fan, W., Wang, L. & Chu, Q. The Paradoxical association of lipids with survival and walking ability of hip fractures in geriatric patients after surgery: A 1-Year Follow-Up study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 3907–3919 (2023).

Kang, X., Tian, B., Zhao, Z. D., Zhang, B. F. & Zhang, M. Evaluation of the association between Low-Density lipoprotein (LDL) and All-Cause mortality in geriatric patients with hip fractures: A prospective cohort study of 339 patients. J. Pers. Med. 13 (2), 345 (2023).

Häder, A. et al. Respiratory infections in the aging lung: implications for diagnosis, therapy, and prevention. Aging Dis. 14 (4), 1091–1104 (2023).

Shin, D., Lebovic, G. & Lin, R. J. In-hospital mortality for aspiration pneumonia in a tertiary teaching hospital: A retrospective cohort review from 2008 to 2018. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 52 (1), 23 (2023).

Uno, I. & Kubo, T. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia among elderly patients in a Community-Based integrated care unit: A retrospective cohort study. Geriatr. (Basel). 6 (4), 113 (2021).

Aiken, L. H. et al. Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 26 (7), 559–568 (2017).

Wu, K. F., Hu, J. L. & Chiou, H. Degrees of shortage and uncovered ratios for Long-Term care in taiwan’s regions: evidence from dynamic DEA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (2), 605 (2021).

Lidetu, T., Muluneh, E. K. & Wassie, G. T. Incidence and predictors of aspiration pneumonia among stroke patients in Western Amhara region, North-West ethiopia: A retrospective follow up study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 1303–1315 (2023).

Kim, S. H. et al. Risk of postoperative Gastrointestinal bleeding and its associated factors: A nationwide Population-Based study in Korea. J. Pers. Med. 11 (11), 1222 (2021).

Chen, G. Y. et al. Incidence of acute upper Gastrointestinal bleeding and related risk factors among elderly patients undergoing surgery for major limb fractures: an analytical cohort study. Healthc. (Basel). 11 (21), 2853 (2023).

Unnanuntana, A. et al. A multidisciplinary approach to post-operative fragility hip fracture care in Thailand - a narrative review. Injury 54 (11), 111039 (2023).

Chuene, M. A., Pietrzak, J. R. T., Sekeitto, A. R. & Mokete, L. Should we routinely prescribe proton pump inhibitors peri-operatively in elderly patients with hip fractures? A review of the literature. EFORT Open. Rev. 6 (8), 686–691 (2021).

Gingrich, A. et al. Prevalence and overlap of sarcopenia, frailty, cachexia and malnutrition in older medical inpatients. BMC Geriatr. 19 (1), 120 (2019).

Emami, A. et al. Comparison of sarcopenia and cachexia in men with chronic heart failure: results from the studies investigating Co-morbidities aggravating heart failure (SICA-HF). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 20 (11), 1580–1587 (2018).

Matsue, Y. et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of the coexistence of multiple frailty domains in elderly patients with heart failure: the FRAGILE-HF cohort study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22 (11), 2112–2119 (2020).

Patel, R. et al. REducing unwarranted variation in the Delivery of high qUality hip fraCture services in England and Wales (REDUCE): protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 11(5), e049763 (2021).

Macey, A. R. M. et al. 30-day outcomes in hip fracture patients during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the preceding year. Bone Jt. Open. 1 (7), 415–419 (2020).

Rowe, K. A. et al. Comparative outcomes and surgical timing for operative fragility hip fracture patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective cohort study. Geriatr. (Basel). 7 (4), 84 (2022).

Haskel, J. D. et al. Hip fracture volume does not change at a new York City level 1 trauma center during a period of social distancing. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 11, 2151459320972674 (2020).

Malik-Tabassum, K. et al. Management of hip fractures during the COVID-19 pandemic at a high-volume hip fracture unit in the united Kingdom. J. Orthop. 20, 332–337 (2020).

Mattisson, L., Bojan, A. & Enocson, A. Epidemiology, treatment and mortality of trochanteric and subtrochanteric hip fractures: data from the Swedish fracture register. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 369 (2018).

Quartley, M., Chloros, G., Papakostidis, K., Saunders, C. & Giannoudis, P. V. Stabilisation of AO OTA 31-A unstable proximal femoral fractures: does the choice of intramedullary nail affect the incidence of post-operative complications? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Injury 53 (3), 827–840 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.T.T. and T.G.G. drafted the work, W.T.W. contributed to interpretation of data, I.H.C. contributed to the conception, T.K.Y. contributed to design of the work, R.P.L. supervised the progression of work, J.H.W. contributed to the acquisition and analysis, and K.T.Y. revised and finally organized the work. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hualien Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (No. IRB108-207-C).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, KT., Guo, TG., Wu, WT. et al. Postoperative mortality following hip fracture surgery in older adults: a single-center retrospective study in the context of Taiwan’s transition to an aged society. Sci Rep 15, 22466 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06181-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06181-9