Abstract

A phenylalanine (Phe)-restricted diet is the only effective treatment in patients with classical phenylketonuria (PKU) in Latvia. This study analysed the protein and Phe content of 28 foods, including some Latvian-specific foods, aiming to expand the range of foods given to the Latvian PKU population. After consultation with Latvian parents and patients a list of preferred foods for analysis was collated. Preference was given to local foods and products were no or limited information about protein and Phe content was available. All food samples were collected from November 2023 until May 2024. Foods were analyzed by protein and amino acid content and compared with international databases. Phe content is reported as mg Phe/100 g of product. The highest amounts were found in microgreens from peas 200 mg/100 g, nettle 210 mg/100 g, wild garlic 140 mg/100 g.The Phe amount in garden cress and sunflower seed microgreen was 150 mg and 140 mg/100 g. A lower Phe content was found in radish 100 mg/100 g and broccoli microgreens: 97 mg/100 g. This study demonstrates that microgreens, and traditional products like sorrel and nettles should be measured within a Phe restricted diet. Rhubarb, celery stalk, raisins and leeks can be eaten without measurement or restriction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inherited metabolic disorders (IMD) represent a diverse group of genetic conditions characterized by disruptions in metabolic pathways1. Phenylketonuria (PKU) is the most prevalent amino acid-related IMD, but other aminoacidopathies, such as tyrosinemia, homocystinuria, glutaric aciduria type 1, and maple syrup urine disease, also result from enzyme deficiencies affecting amino acid (AA) metabolism. Managing these IMDs typically involves adherence to a Phe-restricted diet, in PKU restriction of dietary Phe is essential to prevent the build up of toxic byproducts2,3.

PKU is a rare IMD caused by defects in the phenylalanine-hydroxylase (PAH) gene, catalyzing the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine4. PAH impairment causes phenylalanine accumulation in the blood and brain, with a broad spectrum of pathophysiological and neurological consequences. If PKU is left untreated, it causes severe intellectual disability – intelligence quotient (IQ) < 50/developmental quotients < 20–40, epilepsy, psychotic behaviours such as severe hyperactivity, destructiveness, self-injuring behaviours, and agoraphobia. Anxiety, depression, speech difficulties, and neurological impairments (movement difficulties, tremor) also occur5,6,7,8,9. According to European Society of Phenylketonuria and Applied Disorders (ES.PKU) guidelines, treatment should be started as soon as possible, ideally before 10 days from birth. A 4 weeks’ delay in starting treatment may lead to a decline in IQ score by approximately 4 points10,11.

In Europe, PKU prevalence rates vary widely, in Latvia is approximately 1:6190 newborns12, while the worldwide prevalence is 1:23,93013. The main treatment for PKU is a Phe-restricted diet; dietary restriction is severe with avoidance of foods such as meat, fish, eggs, lentils and peas, dairy products, grains, and aspartame-containing foods and medicine14. Patients with classical PKU have a low Phe tolerance of approximately 4 to 6 g of protein (200 to 300 mg Phe)/day; patients with mild PKU may tolerate approximately 7 to 10 g of protein and in case of mild hyperphenylalaninemia protein tolerance can be as high as 30 g/day of protein10,14. Around 85% of the Latvian PKU population have classical PKU, with approximately 15% with mild PKU15. A diet composed of < 30 g of protein will lead to nitrogen, vitamin and mineral deficiencies and to prevent this a Phe-free protein substitute, providing a comprehensive supply of vitamins, minerals and AA except Phe is taken 3 or 4 times a day. In classical PKU, they may provide up to 75% of total nitrogen requirements14.

The dietary recommendations of PKU in Latvia, are based on the ES.PKU guidelines, with foods divided into three groups:

-

foods that are unmeasured or allowed without restriction i.e. specialized low protein foods and fruits, vegetables, with a Phe content of ≤ 75 mg/100 g,

-

foods that can be consumed in limited quantities i.e. potatoes, green peas, corn, sour cream these are given in controlled amounts as part of an exchange system (Phe content > 75 mg/100 g and < 200 mg/100 g).

-

foods that are high in protein/Phe are prohibited i.e. meat, fish, dairy products (cheese, cottage cheese), legumes, cereals, nuts, seeds, eggs, gelatine, aspartame (Phe content of > 200 mg/100 g)10,14.

Based on E.S.PKU guidelines and the PKU dietary handbook, the Latvian dietary system uses indirect Phe calculation, where 1 g protein is equivalent to 50 mg Phe from fruits and vegetables10,14.

The PKU diet is strict and limiting, so knowledge and reliable dietary information about the Phe content of food is crucial for optimal dietary control. It is important to validate which foods can be incorporated into the diet safely and which should be consumed in limited and measured amounts14,16.

Dietary diversity is important, allowing variability, flexibility, and increasing the capacity to eat more foods socially17. Unfortunately, there is insufficient information about the Phe content of some specific Latvian foods, such as wild garlic, nettle, sorrel, and microgreens; these are used in substantial amounts in the diet and are not limited to food flavouring functions only.

Adherence to a low protein diet is frequently poor, and it is recognized as a challenge across most inherited metabolic disorders and different age groups, often worsening with age, especially in puberty17,18. This issue tends to be more pronounced in chronic conditions where the risk of acute metabolic decompensation is minimal, such as PKU, homocystinuria and tyrosinemia type I and type II. In contrast, for disorders like urea cycle disorders and maple syrup urine disease, poor dietary compliance can quickly lead to metabolic instability and its associated complications19,20.

A comprehensive database on the Phe content of all fresh vegetables/fruits commonly consumed in Latvia is lacking, and so the protein content is used as a proxy measure of Phe content. For example, there are two food databases - FRIDA is the Danish food composition database maintained by the National Food Institute at the Technical University of Denmark, and Fineli is Finland’s national food composition database, maintained by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Both databases are widely used for dietary assessment and research. For example, kohlrabi in the Fineli database contains information only about the protein content, but there is no data on the Phe content21. In the FRIDA database there is information on the Phe content in raw kohlrabi, but no information about when it is cooked or fried22.

The use of microgreens has increased worldwide, including Latvia, in recent years due to their impressive nutritional content23. The microgreens can be added to salads and desserts. Larger quantities are often consumed by adding them to drinks like to smoothies. Unfortunately, there is no data about their Phe composition.

This study aimed to analyze the amino acid (including Phe) content of common Latvian foods (such as a variety of mushrooms, nettle, sorrel, rhubarb, leek, and microgreen), assessing their suitability for inclusion in a Phe-restricted diet for PKU.

Methods

Food selection for nutrition analysis

Caregivers and patients with PKU were invited to identify foods lacking sufficient compositional data via an online form. Ten caregivers and five individuals submitted responses, listing foods (n = 55) that present challenges for adhering to the dietary management of PKU. Subsequently, a team of four dietitians and three pediatricians, one internist reviewed the list and, following discussions with the caregivers, reached a consensus on which Latvian foods should be analyzed for their Phe content. A total of 28 foods were selected, with preference given to locally grown products. The study was conducted between November 2023 and May 2024.

Foods were collected (wild, tinned or frozen), vacuumed, and stored at a temperature − 18 C till analysis. For the analysis one kg of food was prepared. Methods of collection and preparation techniques of foods are mentioned below: (Table 1)

Amino acid analysis

All foods were analysed by J.S. Hamilton Poland Sp. z o.o. (LVS EN ISO/IEC 17025:2017). Fourteen of the AA were analysed by PB-53/HPLC - determining the profile of AA (in total - with peptide bonds and free AA) using pre-column reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography ranging from 0.005 to 10%.

Phe was determined in the unoxidized sample, which was hydrolyzed with a hydrochloric acid solution (C = 6 N). The AAs were converted to the corresponding phenyl thiocyanate derivatives and determined by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet or diode array detector detection (wavelength 254 nm). The content of each AA in the test sample was determined by the internal standard method. The result was expressed as a mass fraction, in a percentage to two decimal places. Samples were analyzed according to the following norms and regulations: PB-116 ed. III of 11 August 2020 for crude protein. The protein content of all 28 chosen foods was given by their total nitrogen content. The study analyzed the full amino acid composition of foods, which is a key strength, offering valuable insights into protein quality and nutrition.

Other nutrients (total energy, protein, fat and carbohydrates) concentrations were analysed using those methods (Table 2).

Results

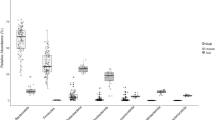

After analysis, all 28 foods were divided into two groups: foods with a Phe content < 75 mg/100 g (Table 3), which is considered low-Phe concentration and foods can be consumed without measurement or restriction, and foods containing more than 75 mg/100 g, so should be measured and controlled as a source of natural Phe in the diet.

Low Phe concentration was observed in foods like prepared wild mushrooms, such as cooked chanterelle, contained 56 mg/100 g of Phe and 1.8 g/100 g of protein. Cooked Boletus edulis (contained 52 mg/100 g of Phe and 2.6 g/100 g of protein. Very low Phe content was observed in frozen rhubarb (9 mg/100 g), fresh celery stalk (21 mg/100 g), boiled celery root (28 mg/100 g) and fresh leeks (37 mg/100 g).

Phe content in raisins depended on the variety. Black and Jambo raisins had a Phe content of ≤ 75 mg/100 g, so they could be given in a Phe-restricted diet without measurement. However, golden raisins contained a higher Phe content of 86 mg/100 g.

All other amino acid analysis is given in Supplement 1. (Table 3)

From our analysis microgreens peas (200 mg/100 g) and nettles (210 mg/100 g) had the highest Phe content (See Table 2). A high Phe content > 75 mg/100 g was also identified in wild garlic (140 mg/100 g), and sorrel (fresh and cooked 120 mg/100 g). Garden cress and sunflower seed microgreens contained 150 mg/100 g and 140 mg/100 g respectively, while radish and broccoli microgreens contained 100 mg/100 g and 97 mg/100 g. The highest concentration of Phe between cultivated mushrooms was observed in cooked Champignon (both brown and white): 150 mg and 100 mg per 100 g, respectively; Portobello mushrooms are also high in Phe: 120 mg/100 g. (Table 4)

Discussion

This is the first publication to describe the AA analysis of foods chosen by patients with PKU and caregivers in Latvia. These include specific foods like nettles and sorrel, which are used in traditional Latvian dishes, and microgreens, which have become more popular in recent years. The detailed analysis, including Phe, leucine, methionine, and tyrosine, might benefit other amino acidopathies requiring an amino acid-restricted diet.

Nutritional data describing the AA content in traditional foods not only helps to ensure safety and diversity of dietary treatment for patients with disorders of AAs but can also contribute to greater dietary accuracy and support. This allows people with PKU and other aminoacidopathies to safely eat traditional foods.

Expanding data on the nutritional value of local foods means that these foods can be safely incorporated into the Phe-restricted diet and can be used to provide healthy nutrition. One of the most difficult challenges for patients and their caregivers is to exclude high-protein foods from the diet, reducing their food choices. Another issue (particularly in Latvia) is the limited variety of special low-protein food available at the market. Also, there are concerns about the nutritional value of low-protein foods, which are high in carbohydrates and sugars20. Including low-Phe nutritious-rich products like rhubarb, and different types of mushrooms, celery root and stalk, leek, nettle, sorrel, and microgreens in limited amount helps to enrich both dietary variety and the micronutrient content24.

Microgreens are eaten fresh and frequently used as garnishes. They add vibrant colour, texture, and flavour to dishes while also offering health benefits25,26.

The microgreens contain an abundant amount of different phytonutrients, varying according to the nature of the plants that are selected to produce the microgreen. They are source of micronutrients such as magnesium, potassium, calcium, iron, vitamin A, vitamin B, C and vitamin K27. They also have reported antioxidant activity, anti-obesity, diabetic and cholinergic activity26,28,29. There is limited information about microgreen’s protein and AAs content. For example, in the FRIDA22, there is no available information, but in the USDA, only data about the protein content of broccoli microgreens is available. This information is controversial because they contain 0 g/100 g protein according to the USDA30, which is different from our data (the protein content is 2.1 g/100 g, and Phe content is 97 mg/100 g). More testing of microgreens is necessary28,31. Our data describing the protein content of broccoli and radish microgreens is like data that was published by Dereje et al. in 2023, who described the protein content as 2.23–3 g/100 g and 1.81–2.58 g/100 g respectively26. Recently published data by Boyle et al. also reported that broccoli microgreens contained Phe > 75 mg/100g32.

Surprisingly a high protein and Phe content was observed in golden raisins, Phe content was 86 mg/100 g. A mean for 3 different types of raisins was protein content 3.2 g/100 g and mean Phe concentration 65 mg/100 g. Similar results were reported by Boyle et al., where mean Phe content of raisins (all types) was 59 mg/100g32 This is also similar to the USDA, with available information describing their Phe content as 65 mg/100 g and protein content 3.07 g/100 g. Previously, it was reported that protein quantity was 2.2 g/100 g and Phe content was 97 mg/100g21,33, although in the PKU dietary handbook, raisins are included in the list of fruits and vegetables that are allowed without measurement in PKU14. The PKU diet is already very challenging, so it is important that any dietary advice should be practical and straightforward. It may cause confusion if there are different rules for different types of raisins, but at the same time it may underestimate the amount of Phe eaten34.

As we report, the Phe content of leeks is 37 mg and protein is 1.2 g per 100 g; in the FRIDA, Phe concentration was 50 mg/100 g, and protein content there is also reported higher – 2 g per 100 g, there is also data available about protein content in USDA about leeks – 1.57 g per 100 g, but there is no data about Phe concentration, data of protein in our study is similar to USDA information.

Mushrooms have a unique nutritional composition with positive health benefits. Mushroom’s dry matter is rich in carbohydrates, including both digestible (trehalose, glycogen, mannitol, and glucose) and non-digestible carbohydrates (chitin, mannans, and β-glucan). They are a complete protein source, containing all essential AAs, and are high in polyunsaturated fatty acids. As the only vegetative source of vitamin D, mushrooms also provide a good amount of B vitamins and various minerals, making them a powerhouse of nutrients for human physiological functions35,36,37,38. There is a wide range of Phe concentrations among different types of mushrooms. For example, boiled shiitake mushrooms contain only 64 mg of Phe/100 g, while cooked Portobello, white, and brown Champignon mushrooms contain 120 mg, 100 mg, and 150 mg per 100 g, respectively, and should be counted in a Phe-restricted diet. Traditional mushrooms for Latvian PKU patients, such as Boletus edulis and chanterelles, are low in Phe. However, there is limited information on the Phe content of Boletus edulis. Our data indicate a protein content of 2.6 g/100 g, which aligns with findings published by Jaworska et al.39 As of January 2025, there was no published information about the Phe content of Boletus edulis mushrooms, White mushrooms, and brown mushrooms in USDA and FRIDA databases. Previously, in Latvia, mushrooms like shiitake and white and brown Champignons were allowed without measurement, but Boletus edulis and Chanterelles were allowed in limited amounts in the PKU diet. The latest data on the Phe content of mushrooms suggests that repeated testing is needed to verify the Phe content in different types of mushrooms.

A low-protein diet can lead to a reduced feeling of satiety, which may cause individuals to consume larger quantities of other foods, such as potatoes, potentially impacting metabolic control. Incorporating various mushrooms into the diet could help individuals with PKU experience a greater sense of fullness due to their fibre content40. Many people with PKU often express that it is challenging to achieve satiety with low-protein foods and vegetables41,42,43,44.

Nutritional data about Latvian traditional foods like sorrel, wild garlic, and nettle are also very limited in international food databases; for example, there is no data about the Phe content of nettles in the USDA, FRIDA or Fineli.

A comparison of the data from our study with food databases is presented in Table 5 .

Without AA data, dietitians are unable to advise about the suitability of these products. Confidence in the Phe analysis is essential for patients with PKU. Reliable measurements ensure that dietary treatment maintains safe Phe concentrations, preventing neurological damage and supporting optimal cognitive and physical development. This confidence is vital for long-term management, where consistent monitoring is required to adapt to changes in a patient’s age, metabolism, and lifestyle.

Unfortunately, patients with PKU often exhibit neophobia, which makes introducing new products and flavours into their diets a challenging task. Therefore, it is crucial to incorporate as many allowed products as possible early in life, particularly during the first few years45. This strategy aims to expand the child’s menu to include items from both the allowed and in limited amount consumed food lists46,47,48.

One limitation of the study is that the nutrient analysis was conducted during just one season, which could be influenced by climate; therefore, it is recommended to evaluate the same local products collected across different seasons. Another limitation of this study is that the nutritional value of the products was analyzed in a single laboratory. To ensure confidence in the nutritional analysis, it is essential to repeat the analyses in a different laboratory.

The way foods were stored, duration of storage, and cooking technique can affect the nutrient content. For example, sorrel dries very quickly and consequently, it was not possible to deliver it raw to the laboratory. Therefore, it had to be frozen to ensure transportation, and this will affect the amount of water, protein and Phe in the product. Comparing fresh, frozen, and cooked forms of each food could help assess the impact of storage and preparation methods on protein and Phe content. Also standardized protocols for sample handling and transportation should be established to minimize nutrient loss.

By actively involving patients with PKU and their caregivers, our study ensures that the research is based on the real-life experiences of patients and the needs of the PKU community. It also helps develop practical dietary recommendations that can improve the quality of life for individuals with PKU.

This research expands the range of dietary options available to PKU patients, allowing them to maintain nutritional balance while adhering to the strict and limiting Phe-restricted diet.

Our work advances PKU dietary research, enhances patient support, and promotes healthier food choices tailored to specific medical needs.

Conclusion

It is important for patients with PKU to expand the range of foods, that can be added to their diet. Such foods like rhubarb, celery root, stalk and leek have the lowest Phe concentration and can be consumed without measurement, while foods like nettle, peas microgreens and champignons mushrooms have the highest Phe levels and should be counted in the low-Phe diet.

It is essential to continue assessing the nutrients in both traditionally used products and new foods entering the global market. This will provide patients with reliable and current information about the nutritional composition of food products. Also, it will improve patients’ adherence to a Phe-restricted diet; it is crucial to provide accurate and comprehensive information about the nutritional content of food products, including not only protein but also their phenylalanine concentration.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Methods of collection and preparation techniques of foods are available in Supplement 1. Information about applied methods of laboratory analyses is available in Supplement 2 and data about amino acid content in foods are provided in Supplement 3.

References

Hauser, S. I. et al. Trends and outcomes of children, adolescents, and adults hospitalized with inherited metabolic disorders: A population-based cohort study. JIMD Rep. 63, 581–592 (2022).

Gold JI, Stepien KM. Healthcare Transition in Inherited Metabolic Disorders-Is a Collaborative Approach between US and European Centers Possible? J Clin Med. 2022 Sep 30;11(19):5805.

Boyer, S. W., Barclay, L. J. & Burrage, L. C. Inherited metabolic disorders: aspects of chronic nutrition management. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 30, 502–510 (2015).

Orphanet Phenylketonuria. https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/716. Accessed 19 Nov 2024.

Woolf, L. I., & Adams, J. (2020). The Early History of PKU. International journal of neonatal screening, 6(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns6030059

Rovelli, V. & Longo, N. Phenylketonuria and the brain. Mol. Genet. Metab. 139, 107583 (2023).

Williams, R. A., Mamotte, C. D., Burnett, J. R., Prof, C. & Burnett, J. Mini-review Phenylketonuria: An Inborn Error of Phenylalanine Metabolism. (2008).

Whitehall, K. B. et al. Systematic literature review of the somatic comorbidities experienced by adults with phenylketonuria. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 19, 293 (2024).

Blau, N., Van Spronsen, F. J., Levy, H. L. & Phenylketonuria Lancet ;376:1417–1427. (2010).

van Wegberg, A. M. J. et al. The complete European guidelines on phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 12, 162 (2017).

Smith, I., Beasley, M. G. & Ades, A. E. Intelligence and quality of dietary treatment in phenylketonuria. (1990).

Unpublished data.

Hillert, A. et al. The genetic landscape and epidemiology of phenylketonuria. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107, 234–250 (2020).

MacDonald, A. et al. PKU dietary handbook to accompany PKU guidelines. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15, 171 (2020).

Kreile, M. et al. Phenylketonuria in the Latvian population: molecular basis, phenylalanine levels, and patient compliance. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 25, 100671 (2020).

Araújo, A. C. M. F., Araújo, W. M. C., Marquez, U. M. L., Akutsu, R. & Nakano, E. Y. Table of phenylalanine content of foods: comparative analysis of data compiled in food composition tables. In: JIMD Reports. Springer; 87–96. (2017).

MacDonald, A., Van Rijn, M., Gokmen-Ozel, H. & Burgard, P. The reality of dietary compliance in the management of phenylketonuria. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 33, 665–670 (2010).

Beghini M. et al. Poor adherence during adolescence is a risk factor for becoming lost-to-follow-up in patients with phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2024 May 9;39:101087.

MacDonald, A. et al. Adherence issues in inherited metabolic disorders treated by low natural protein diets. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 61, 289–295 (2012).

Lim, J. Y. et al. Exploring the barriers and motivators to dietary adherence among caregivers of children with disorders of amino acid metabolism (AAMDs): A qualitative study. Nutrients 14, 2535 (2022).

Food - Fineli. https://fineli.fi/fineli/en/elintarvikkeet/428. Accessed 25 Apr 2024.

Frida -. https://frida.fooddata.dk/food/search?lang=en&q=broccoli. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Lone, J. K., Pandey, R., & Gayacharan (2024). Microgreens on the rise: Expanding our horizons from farm to fork. Heliyon, 10(4), e25870.

He, Y. et al. Effects of dietary fiber on human health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 11, 1–10 (2022).

Sharma, S. et al. Vegetable microgreens: the Gleam of next generation super foods, their genetic enhancement, health benefits and processing approaches. Food Res. Int. 155, 111038 (2022).

Dereje, B., Jacquier, J. C., Elliott-Kingston, C., Harty, M. & Harbourne, N. Brassicaceae microgreens: phytochemical compositions, influences of growing practices, postharvest technology, health, and food applications. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 3, 981–998 (2023).

De Pascale, S. et al. Nutrient levels in Brassicaceae microgreens increase under tailored Light-Emitting diode spectra. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01475

Wojdyło, A., Nowicka, P., Tkacz, K. & Turkiewicz, I. P. Sprouts vs. Microgreens as Novel Functional Foods: Variation of Nutritional and Phytochemical Profiles and Their In vitro Bioactive Properties. Molecules 25, Page 4648 (2020).

Wojdyło, A., Oszmiański, J. & Czemerys, R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 105, 940–949 (2007).

FoodData Central. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/2480548/nutrients. Accessed 19 Jun 2024.

Rengasamy, R. et al. Molecules Microgreens-A comprehensive review of bioactive molecules and health benefits. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28020867

Boyle, F. et al. Determination of the protein and amino acid content of fruit, vegetables and starchy roots for use in inherited metabolic disorders. Nutrients 16, 2812 (2024).

Bolin, H. R. & Petrucci, V. Amino Acids in Raisins.

Evans, S. et al. Uniformity of food protein interpretation amongst dietitians for patients with phenylketonuria (PKU): 2020 UK National consensus statements. Nutrients 12, 2205 (2020).

Yadav, D. & Negi, P. S. Bioactive components of mushrooms: processing effects and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 148, 110599 (2021).

Rathore, S., Habes, M., Iftikhar, M. A., Shacklett, A. & Davatzikos, C. A review on neuroimaging-based classification studies and associated feature extraction methods for alzheimer’s disease and its prodromal stages. Neuroimage 155, 530–548 (2017).

Cardwell, G., Bornman, J. F., James, A. P. & Black, L. J. A Review of Mushrooms as a Potential Source of Dietary Vitamin D. Nutrients. ;10. (2018).

Samsudin, N. & Abdullah, N. Edible mushrooms from Malaysia; a literature review on their nutritional and medicinal properties. (2019).

Jaworska, G., Pogoń, K., Skrzypczak, A. & Bernaś, E. Composition and antioxidant properties of wild mushrooms boletus Edulis and xerocomus Badius prepared for consumption. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 7944 (2015).

Hess, J. M., Wang, Q., Kraft, C. & Slavin, J. L. Impact of agaricus bisporus mushroom consumption on satiety and food intake. Appetite 117, 179–185 (2017).

Pezeshki, A., Zapata, R. C., Singh, A., Yee, N. J. & Chelikani, P. K. Low protein diets produce divergent effects on energy balance. Scientific Reports 2016;6:1–13. (2016) 6:1.

Moon, J. & Koh, G. Clinical evidence and mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced weight loss. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 29, 166–173 (2020).

Li, T. et al. The effect of taste and taste perception on satiation/satiety: a review. Food Funct. 11, 2838–2847 (2020).

Daly, A. et al. The Impact of the Use of Glycomacropeptide on Satiety and Dietary Intake in Phenylketonuria. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092704

Białek-Dratwa, A., & Kowalski, O. (2023). Infant Complementary Feeding Methods and Subsequent Occurrence of Food Neophobia-A Cross-Sectional Study of Polish Children Aged 2-7 Years. Nutrients, 15(21), 4590. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15214590

Evans, S. et al. The influence of parental food preference and neophobia on children with phenylketonuria (PKU). Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 14, 10–14 (2018).

Tonon, T. et al. Food neophobia in patients with phenylketonuria. Original Article J. Endocrinol. Metab. 9, 108–112 (2019).

Evans, S., Daly, A., Chahal, S., MacDonald, J. & MacDonald, A. Food acceptance and neophobia in children with phenylketonuria: a prospective controlled study. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietetics. 29, 427–433 (2016).

Funding

The research is carried out within the framework of the European Union Recovery and Resilience Mechanism Plan and the state budget-funded project “RSU internal and RSU with LASE external consolidation” Nr.5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/005, implemented under Doctoral Grant to Olga Ļubina.

Linda Gailite received RSU Internal grant No 6-ZD-22/26/2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.Lubina wrote the main manuscript text. M.Auzenbaha design and reviewed the work.S.Laktina and L.Gailite worked on the interpretation of data, and L.Gailite also reviewed the manuscript.A. MacDonald and A. Daly substantively revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lubina, O., Daly, A., Auzenbaha, M. et al. Nutritional profiling of foods for Phenylketonuria. Sci Rep 15, 22538 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06633-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06633-2