Abstract

In this study, we investigated the association between wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in different geographic regions of Taiwan in a large cohort. Participants (n = 120,424) residing in the four main geographical areas of Taiwan (North, Central, South and Eastern Taiwan) were enrolled from the Taiwan Biobank. Questionnaires were used to ascertain the presence of GERD based on self-reported physician diagnosis, and WBGT was assessed separately during working (8:00 AM to 5:00 PM) and noon (11:00 AM to 2:00 PM) periods. In Northern Taiwan, there is no significant association between WBGT and GERD during either the noon or working period. In Central Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year WBGT values per 1℃ increase during the noon period (odds ratio [OR], 1.055 [95% CI 1.008–1.105]; 1.062 [95% CI 1.013–1.114]; 1.059 [95% CI 1.009–1.111]) and working period (OR, 1.089 [95% CI 1.034–1.146]; 1.092 [95% CI 1.037–1.150]; 1.084 [95% CI 1.031–1.139]) were significantly associated with GERD. Similarly, in Southern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year WBGT values per 1℃ increase during the noon period (OR, 1.292 [95% CI 1.236–1.351]; 1.323 [95% CI 1.261–1.389]; 1.386 [95% CI 1.316–1.460]) and working period (OR, 1.238 [95% CI 1.190–1.288]; 1.247 [95% CI 1.196–1.301]; 1.259 [95% CI 1.204–1.318]) were significantly associated with GERD. However, in Eastern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year WBGT values per 1℃ increase during the noon period were significantly associated with GERD (OR, 1.067 [95% CI 1.015–1.122]; 1.089 [95% CI 1.041–1.138]; 1.107 [95% CI 1.058–1.158]), whereas the 1-, 3-, and 5-year WBGT values per 1℃ decrease during the working period were significantly associated with GERD. Increases in average WBGT values were significantly associated with GERD during both the noon and working periods in Central and Southern Taiwan, and the impact of WBGT was much stronger in Southern Taiwan. While a similar result was found in Eastern Taiwan during the noon period, a reverse correlation was found during the working period. Our findings suggest that heat stress may be associated with GERD, although the impact may differ according to regional characteristics. The causal relationship could not be confirmed due to the cross-sectional design of the study. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to establish the relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a gastrointestinal disorder in which regurgitation of gastric contents into the esophagus cause symptoms and/or complications1. Even though GERD is among the most common digestive diseases in Taiwan, with an estimated prevalence of up to 25% in the community2 and worldwide3 its pathogenesis is complex and has still not been fully elucidated4. Typical clinical features include acid regurgitation and heartburn, both of which can negatively affect the quality of life5. GERD has also been associated with the development of Barrett’s esophagus, which is a known precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma6 and has been linked to other diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease7 coronary heart disease8 and major depressive disorder9. The risk factors for GERD include those that are non-modifiable such as genetic factors10 and those that are modifiable such as lifestyle habits and daily diet11. With the increase in the global disease burden of GERD3 exploring and identifying these risk factors is of increasing importance.

Evidence has shown that global warming cause an unprecedented increase of ambient temperature over the past 50 years12. High temperatures can have an adverse impact on human and public health13. Also, occupational injury due to heat stress is an emerging and crucial health issue14. Increases in the risk of cardiovascular disease15 respiratory disease16 renal disease17 and even mortality18 have been associated with heat stress. Previous studies have also shown that an elevated temperature can lead to a higher rate of gastrointestinal infections19,20 possibly due to an increase in specific pathogens. For example, the rate of food-borne diseases due to Salmonella is increasing in Australia21.

The US military originally introduced the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) with the aim of reducing severe illnesses related to heat exposure22. Compared to ambient temperature, WBGT is a more accurate tool to assess how heat stress affects health by combining humidity and temperature, and it has been shown to be particularly relevant in people engaged in outdoor activities23. A recent study showed that the average global WBGT index continues to increase, and that this may be due to global warming24.

Taiwan is a small island spanning both tropical and subtropical zones, and hence the climate is diverse. Taiwan can be divided into four major areas based on administrative divisions, namely Northern, Central, Southern, and Eastern regions. Each region has distinct weather patterns attributable to the geographical environment, latitude, and even degree of urbanization and industrialization. Both the average and seasonal WBGT values in the South of Taiwan are higher than those in the other areas25.

Little research has investigated the associations among environmental factors, and especially heat stress using WBGT, and GERD. In this study, we enrolled community-dwelling participants from the Taiwan Biobank (TWB), and calculated their average WBGT values using a machine learning model with data on solar radiation, humidity and temperature. There were two main aims in this study: (1) examine the association between GERD and WBGT; and (2) explore how the association varied across the four main geographical areas of Taiwan.

Materials and methods

Subject recruitment from the TWB

The TWB was established by the Ministry of Health and Welfare with the objective of tackling chronic diseases and issues caused by the increasing age of the population, and to enhance healthcare services. The TWB provides comprehensive medical, genetic, and lifestyle data on people aged 30–70 years from around Taiwan who have never been diagnosed with cancer26,27. More details on the TWB can be found here: https://www.twbiobank.org.tw/. The establishment and operation of the TWB are overseen and approved by its Ethics and Governance Council and Institutional Review Board on Biomedical Science Research at Academia Sinica. Eligible participants were required to be of Taiwanese ethnicity, provide written informed consent. We further apply for an IRB to apply for these materials from Taiwan biobank for analysis. The present study was approved by the IRB of our institute (KMU-HIRB-E(I)−20240338, 2024/10/11), and it was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

After consenting to enrollment, data are collected from the participants using structured questionnaires, physical and fasting blood examinations, including height/weight/body mass index, history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, age, sex, and the use of tobacco and alcohol. The blood examinations include total cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), uric acid, glucose, hemoglobin, and triglycerides. eGFR was measured using the CKD-EPI creatinine Eq. (2021)28.

Blood pressure was also measured by a trained nurse following standard methods, with averages of three systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings utilized for analysis.

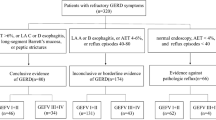

Study participants

The TWB included 121,364 enrollees at the time of this study. We excluded those residing outside the main island of Taiwan (n = 940), as they did not have WBGT data. The remaining 120,424 participants were enrolled. The enrolled participants resided in the four major geographic and administrative divisions areas of Taiwan, namely the North, Center, South, and East (Fig. 1). There are slight differences in the climate among these areas. According to the classification commonly accepted by the scientific community, the region between 23.5 degrees north latitude and 23.5 degrees south latitude is defined as the tropical zone, while the area of Taiwan north of 23.5 degrees north latitude is classified as the subtropical zone. Based on this classification, the climate in the South of Taiwan is tropical, and there are five cities/counties. The climate in the North and Center is subtropical, and there are four and seven cities/counties, respectively. Due to the length of the Eastern region, it encompasses both subtropical and tropical zones, and there are five counties.

Definition of GERD

Questionnaires were used to ascertain the presence of GERD based on self-reported physician diagnosis. The participants were asked, “Have you been diagnosed with GERD?”, and those who replied “Yes” were considered to have GERD. The participants were classified into GERD and non-GERD groups accordingly.

Assessment of WBGT

The Central Weather Bureau (CWB) manages 453 weather stations around Taiwan25. We collected data on hourly temperature provided by the CWB from 2000 to 2020. The WBGT was calculated as 0.7tnw + 0.2tg + 0.1ta, where ta is the dry bulb temperature, tg the globe temperature, and tnw the natural wet-bulb temperature. Data for each weather station were recorded, and two time periods were used for analysis: working (8:00 AM to 5:00 PM), and noon (11:00 AM to 2:00 PM) periods. WBGT levels for each hour were then used as the dependent variable to develop a land use-based spatial machine learning (LBSML) model to predict highly spatial-temporal variations in WBGT. As solar declination, rainfall, wind speed, and relative humidity can affect WBGT, these data were also recorded. Data on land use including parks, industrial and residential areas, lakes and reservoirs, roads and features of interest such as temples and restaurants were also collected. SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values were used to select important predictors. A light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM) algorithm with the selected predictors was then used to build the prediction model. The combination of temperature with land use/land cover prediction data significantly improved the performance of the LBSML model, with an R2 value as high as 0.9929. The LBSML model yielded spatial-temporal WBGT values with a high-resolution grid of 50 m × 50 m.

Linking data from the TWB and WBGT

To estimate heat exposure, TWB and WBGT data were linked at the township level by residential address of the participants. Annual average WBGT values were calculated, along with average WBGT values for 1, 3, and 5 years for each participant before enrollment. These WBGT values were used to assess both the long- (3- and 5-year) and short- (1-year) term effects of heat stress.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as percentage or mean ± (SD). Independent t-tests were used for comparisons of continuous data between groups, while chi-square tests were used for categorical data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons among groups. The association between WBGT and GERD was examined with logistic regression analysis. Variables that showed significance in univariable analysis for GERD in Table 1 (including WBGT, age, sex, smoking and alcohol history, diabetes, hypertension, fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, eGFR and uric acid) were subsequently included in multivariable analysis. A p value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. Data analysis was done with SPSS version 25 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY).

Path analysis was conducted using PROC CALIS (Covariance Analysis of Linear Structural Equations) in SAS to examine whether the 1-year average WBGT during the noon period and age were directly or indirectly associated with GERD, after adjusting for covariates including sex, smoking and alcohol history, diabetes, hypertension, fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, eGFR and uric acid. The analysis was stratified by geographic region—Northern Taiwan, Central Taiwan, Southern Taiwan, and Eastern Taiwan—to assess regional variations in the direct and indirect effects of ambient temperature on GERD. A similar path analysis was conducted to evaluate whether WBGT during the noon period and sex were directly or indirectly associated with GERD, adjusting for age and the same set of covariates. Additional path analyses were performed using extended exposure windows, including the 3-year and 5-year average WBGT during the noon period, and the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year average WBGT during the work period. Subsequently, individual path models were constructed in a stepwise manner to examine the potential direct and indirect associations between WBGT and each of the following factors: smoking, alcohol history, diabetes, hypertension, fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, eGFR and uric acid. In each model, WBGT and the variable of interest were included as predictors, with adjustment for the remaining covariates.

Results

If the 120,424 enrolled participants, 43,250 were men and 77,174 were women, and their mean age was 49.9 ± 11.0 years. A total of 16,468 (13.7%) were classified into the GERD group, and 103,956 (86.3%) into the non-GERD group. Regarding the region of residence, 33.4% of the participants resided in Northern, 19.2% in Central, 37.9% in Southern, and 9.5% in Eastern Taiwan. The average WBGT values at 1, 3, and 5 years before the survey year during the noon period were 27.25 ± 1.08, 27.11 ± 1.10, and 26.97 ± 1.10℃, respectively, compared to 25.02 ± 1.17, 24.93 ± 1.16, and 24.80 ± 1.16℃, respectively, during the working period.

Clinical characteristics of the GERD groups

More of those with GERD were female, older, and had higher rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and tobacco and alcohol use, along with higher fasting glucose, triglycerides and total cholesterol, and lower eGFR and uric acid than those without GERD (Table 1).

Comparisons of the clinical characteristics of the GERD group by geographic region

There were significant differences in age, sex, tobacco and alcohol use, diabetes, hypertension, systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings, body mass index and laboratory parameters among the participants in different geographic regions (Table 2). Compared to Northern, Central and Eastern Taiwan, the average WBGT values were higher in Southern Taiwan during both the working and noon time windows at 1, 3, and 5 years.

Associations between WBGT and GERD by geographic region

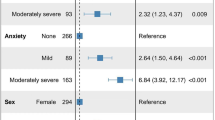

Associations between WBGT and GERD by geographic region were examined in multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 3), with adjustments for the significant variables shown in Table 1. In Northern Taiwan, there was no significant difference between WBGT and GERD during either the noon or working period. In Central Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ increase were significantly associated with GERD during both the noon period (odds ratios [ORs], 1.055 [95% CI 1.008–1.105]; 1.062 [95% CI 1.013–1.114]; 1.059 [95% CI 1.009–1.111], respectively) and working period (ORs: 1.089 [95% CI 1.034–1.146]; 1.092 [95% CI 1.037–1.150]; 1.084 [95% CI 1.031–1.139], respectively). Similarly, in Southern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ increase were significantly associated with GERD during both the noon period (ORs: 1.292 [95% CI 1.236–1.351]; 1.323 [95% CI 1.261–1.389]; 1.386 [95% CI 1.316–1.460], all p < 0.001, respectively) and working period (ORs: 1.238 [95% CI 1.190–1.288]; 1.247 [95% CI 1.196–1.301]; 1.259 [95% CI 1.204–1.318], all p < 0.001, respectively). In Eastern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ increase were significantly associated with GERD during the noon period (ORs: 1.067 [95% CI 1.015–1.122], p = 0.012; 1.089 [95% CI 1.041–1.138], p < 0.001; 1.107 [95% CI 1.058–1.158], p < 0.001, respectively). However, there was a reverse relationship between WBGT and GERD during the working period, and the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ decrease were significantly associated with GERD (ORs: 0.874 [95% CI 0.837–0.913], 0.899 [95% CI 0.859–0.940], and 0.894 [95% CI 0.854–0.935], all p < 0.001, respectively). The associations between WBGT and GERD at 1, 3, and 5 years during the noon and working periods by geographic region are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Forest plots of the association of WBGT in work period with GERD using multivariable logistic regression analysis stratification by geographic regions. In Central and Southern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ increase were associated with GERD, whereas in Eastern Taiwan, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year average WBGT values per 1℃ decrease were associated with GERD.

The path analysis results, presented in Supplementary Tables 1 to 6, illustrate that most of the direct effects of ambient temperature (WBGT), as well as its associations with individual variables—including age, sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hypertension, fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, eGFR, and uric acid—on GERD were observed across Central, Southern, and Eastern Taiwan during the noon or work period. Each variable was included as a predictor, with adjustments made for the remaining covariates. Although the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) values from the path analyses did not indicate a good model fit, the findings were generally consistent with those presented in Table 3, which shows the association between WBGT and GERD in Central, Southern, and Eastern Taiwan (excluding Northern Taiwan) using multivariable logistic regression analysis.

To assess the potential nonlinear relationship between the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year average WBGT (during both noon and work periods) and the risk of GERD across different geographic regions, a restricted cubic spline analysis with five knots was conducted using a logistic regression model (Fig. 4). The analysis adjusted for multiple covariates, including age, sex, smoking and alcohol history, diabetes, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, BMI, fasting glucose, hemoglobin, triglycerides, total cholesterol, eGFR and uric acid. The spline knots were placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles of the WBGT distribution in the study sample. The relationship between the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year average WBGT (during both the noon and work periods) and the risk of GERD exhibited nonlinear effects, with statistical significance observed for both the noon period (p < 0.001) and the work period (p < 0.001).

Nonlinear relationship between the noon period: 1-year (A), 3-year (B), and 5-year (C), and work period: 1-year (D), 3-year (E), and 5-year (F) average WBGT and the risk of GERD across different geographic regions. The relationship between the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year average WBGT and the risk of GERD exhibited nonlinear effects, with statistical significance observed for both the noon and work period using a restricted cubic spline analysis with five knots was conducted using a logistic regression model.

To assess potential clustering effects within geographic regions, we further used mixed-effects models. A clustering analysis of residence was conducted using a Generalized Linear Model (PROC GENMOD), adjusting for covariates, to assess clustering effects within geographic regions for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year average WBGT (during both noon and work periods) and its association with the risk of GERD. Our results (Table 4) showed no significant clustering effects (WBGT*Residence, Type 3 p > 0.05). The interaction term (WBGT*Residence) was used to test whether there is a heterogeneous effect between WBGT in different residential areas and the risk of GERD.

Discussion

This study demonstrated associations between WBGT and GERD during noon and working periods at 1, 3, and 5 years in different geographic regions of Taiwan. We found that in Central and Southern Taiwan, average WBGT values were significantly associated with GERD during both the noon and working periods, whereas this positive correlation was only seen during the noon period in Eastern Taiwan. In addition, the relationship between increased WBGT values and GERD was much stronger in Southern Taiwan than in Central and Eastern Taiwan. Interestingly, a reverse relationship between WBGT and GERD was observed during the working period in Eastern Taiwan, while no significant association was found between WBGT and GERD in Northern Taiwan during either the noon or working period.

No study to date has focused on the direct mechanism through which WBGT leads to GERD. A study from Korea reported that other environmental factors such as the levels of particulate matter with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm and carbon monoxide were identified as risk or aggravating factors for GERD30. Research on the link between high ambient temperature and GERD is limited, however some indirect evidence may support our findings. First, high ambient temperature can cause physical and heat stress, both of which are associated with mortality31,32. In addition, stress can cause GERD through alterations in brain-gut interactions33. Second, high temperatures can lead to dehydration. A previous study reported delayed gastric emptying in patients who were dehydrated34and that this could result in GERD. In addition, dehydration can result in decreased saliva flow rate and increased saliva osmolality35. Saliva is known to have a protective role against GERD by chemically neutralizing acid and protecting the epithelium36and this may lead to the development or progression of GERD. Third, a previous study showed reduced gastric emptying in a hot environment compared to a neutral environment37which may also result in GERD. WBGT combines temperature and humidity. As for humidity, previous study showed that high humidity may decrease parasympathetic nerve activity38. As we know, disturbances of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system had been seen as one of important pathogenesis for GERD39,40. Combine together, study also showed that long-term exposure to a humid heat environment harms health by impairing the gut microbiota and related metabolites41which gut microbiota may also serve a role in causing GERD based on recent studies42,43.

The lack of an association between WBGT and GERD in Northern Taiwan may be due to the specific characteristics of cities in this area. There are seven cities in Northern Taiwan, most of which are highly urbanized and developed. For example, Hsinchu City is known for its high-tech industry, and Taipei City is the capital and one of the most modern cities in Taiwan. According to data from Invest Taipei Office, about half of all residents are employed, and more than 70% of jobs are in service industries. Considering that most residents work and live in places with air conditioning, this may reduce the impact of environmental temperature on human health and at least partially explain our findings.

Another important finding is that the relationship between increased WBGT values and GERD was much stronger in Southern Taiwan compared to Central and Eastern Taiwan. Our analysis showed that the highest 1-, 3- and 5-year average WBGT values occurred in Southern Taiwan during both the noon and working periods. This may be because Southern Taiwan is the only region in which all of the studied cities were located in areas with a tropical climate. A previous study identified specific temperature thresholds in the temperature-mortality relationship44and upper temperature thresholds of life have also been discussed45. We consider that the impact of ambient temperature on GERD may also follow a similar pattern. Our findings may be explained by the baseline average WBGT in Southern Taiwan already exceeding a specific threshold, and therefore further increases in WBGT may be associated with a much greater risk of GERD. The above explanation is our hypothesis and needs more empirical evidence to confirm.

Our findings in Eastern Taiwan were different to the other regions, and a relationship between increased WBGT values and GERD was only seen during the noon period, whereas a reverse relationship was seen during the working period. This may be due to the distinct geographical environmental factors in Eastern Taiwan. Huadong Valley is the most heavily populated area of Eastern Taiwan. It is a long and narrow valley located between the Coastal and Central Mountain Ranges, stretching from Hualian City to Taitung City (https://maps.nlsc.gov.tw/T09E/mapshow.action? language=EN&lat=22.649242&lon=120.310989&zoom=18 from National Land Surveying and Mapping Center). A previous study found that an inversion layer can form and cover valley cities, thereby restricting the diffusion capacity of heat and pollutants46. Therefore, the maximum solar radiation around noon and the restricted diffusion in Eastern Taiwan may cause a rapid elevation in temperature during the noon period. Another study also showed that the urban heat island effect may be strongest at noon and then decrease in the afternoon in rural areas compared to urban areas in a typical valley city in China47. Taken together, we believe that there may be a relatively high temperature difference between the working period and noon period in Eastern Taiwan, but that it was masked by the average WBGT in our study. Consequently, the rapid increase in ambient temperature and humidity during the noon period in Eastern Taiwan may be a risk factor for GERD, but the average WBGT during the working period may be balanced and serve as a protective factor against GERD. Another possible explanation is that a high ambient temperature serves as a protective factor against GERD in specific situations. A previous study in Taiwan reported seasonal variations in the incidence of GERD, with the highest incidence during winter48 during which the ambient temperature may be relatively low. Possible explanations for this finding had been mentioned. For example, obesity is a known risk factor for GERD49 and body weight has been shown to fluctuate, with a low in summer and high in winter50. Also, lifestyle changes such as increased mean dietary intake of fat in the winter has also been reported51 which is also a known risk factor for GERD11. Based on these indirect evidences, we believe that a high ambient temperature may be a protective factor against GERD in some situations.

The inclusion of a large number of healthy volunteers from the TWB residing in different geographic areas around Taiwan increases the validity of our findings regarding the association between WBGT and GERD. Nevertheless, several limitations should also be mentioned. First, we could not assess the temporal relationship between WBGT and GERD due to the cross-sectional design of the study and the GERD diagnosis is not newly diagnosed. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to investigate the risk of WBGT for incident GERD, and whether WBGT change can reduce the incidence of GERD. Second, the participants with GERD were identified solely through self-reported questionnaires, which may introduce recall bias and misclassification, and so we could not assess severity. As detailed data on symptom frequency or duration were not available in our dataset, we were unable to perform subgroup or sensitivity analyses based on symptom severity. Furthermore, given the large sample size, non-differential misclassification of GERD status between cases and controls is likely, which would generally bias the estimated odds ratios toward the null and potentially lead to an underestimation of the true association. Nevertheless, we still observed a statistically significant association, suggesting that the true effect may be even stronger than reported. Nevertheless, moderate concordance has been reported between claims data and self-reported diseases in Taiwan52. However, incorporating clinical diagnoses or objective measures (e.g., endoscopy or pH) would enhance the accuracy of the diagnosis and reduce the potential for misclassifications. Third, we did not have information on the WBGT indoors. The use of dehumidifiers and air conditioners indoors can reduce extreme temperatures and humidity when they are high outdoors, and this may have underestimated the association between WBGT and GERD. Further stratified analysis by occupation (e.g., outdoor vs. indoor workers) may be warranted to improve this research limitation. However, a previous study demonstrated a strong correlation between outdoor and indoor temperatures when the outdoor temperature exceeds 12.7℃53. This correlation may also apply to WBGT, and thus the impact on our results may be minimal. However, the study lacks data on indoor WBGT, which may not fully capture the impact of indoor heat stress on GERD. In addition, since this study is based on an ecological research design and the Taiwan Biobank includes cross-sectional data, it may be challenging to explore the relationship between seasonal fluctuations and GERD incidence. The ecological design makes it difficult to investigate the association between seasonal fluctuations and GERD incidence. Future research should consider a cohort study design that tracks seasonal fluctuations in exposure and their impact on the incidence of GERD. Finally, there were more women than men in this study, possible due to their greater willingness to participate in research studies, and so our findings may not be generalizable to men. Besides, the study population is predominantly Taiwanese, and the findings may not be generalizable to other populations with different genetic, cultural, or environmental backgrounds.

In conclusion, higher average WBGT values were significantly associated with GERD during both the noon and working periods in Central and Southern Taiwan, and the impact of WBGT was much stronger in Southern Taiwan. A higher average WBGT value was also significantly associated with GERD in Eastern Taiwan during the noon period, however a reverse relationship was found during the working period, possibly due to specific geographical and environmental factors. Our findings suggest that heat stress may be associated with GERD, although the impact may differ according to regional characteristics. The causal relationship could not be confirmed due to the cross-sectional design of the study. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to better establish the temporal relationship between WBGT and incident GERD, involving repeated measures of WBGT and GERD symptoms over time, and the physiological mechanisms linking heat stress to GERD, such as the impact of dehydration on gastric emptying and saliva production.

Data availability

The data underlying this study are from the Taiwan Biobank. Due to restrictions placed on the data by the Personal Information Protection Act of Taiwan, the minimal data set cannot be made publicly available. Data may be available upon request to interested researchers. Please send data requests to: Szu-Chia Chen, PhD, MD. Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University.

References

Vakil, N. et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 1900–1920. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x (2006). quiz 1943.

Hung, L. J., Hsu, P. I., Yang, C. Y., Wang, E. M. & Lai, K. H. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in a general population in Taiwan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 1164–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06750.x (2011).

El-Serag, H. B., Sweet, S., Winchester, C. C. & Dent, J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut 63, 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269 (2014).

Kahrilas, P. J. GERD pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 70, S4 (2003).

Alzahrani, M. A. et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of GERD patients in the Aseer region, Saudi Arabia. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 12, 3217–3221. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_620_23 (2023).

Shaheen, N. J. et al. Diagnosis and management of barrett’s esophagus: an updated ACG guideline. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 117, 559–587. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680 (2022).

Lee, A. L. & Goldstein, R. S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in COPD: links and risks. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 10, 1935–1949. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S77562 (2015).

Chen, C. H., Lin, C. L. & Kao, C. H. Association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and coronary heart disease: A nationwide population-based analysis. Medicine 95, e4089 (2016).

Miao, Y. et al. Bidirectional association between major depressive disorder and gastroesophageal reflux disease: Mendelian randomization study. Genes 13, 2010 (2022).

Argyrou, A. et al. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease and analysis of genetic contributors. World J. Clin. Cases. 6, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.176 (2018).

Taraszewska, A. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms related to lifestyle and diet. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 72, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.32394/rpzh.2021.0145 (2021).

Gulev, S. K. et al. Changing state of the climate system. (2021).

Kovats, R. S. & Hajat, S. Heat stress and public health: a critical review. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 29, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090843 (2008).

Binazzi, A. et al. Evaluation of the impact of heat stress on the occurrence of occupational injuries: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 62, 233–243 (2019).

Burkart, K. et al. The effect of atmospheric thermal conditions and urban thermal pollution on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Bangladesh. Environ. Pollut. 159, 2035–2043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2011.02.005 (2011).

Michelozzi, P. et al. High temperature and hospitalizations for cardiovascular and respiratory causes in 12 European cities. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 179, 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200802-217OC (2009).

Glaser, J. et al. Climate change and the emergent epidemic of CKD from heat stress in rural communities: the case for heat stress nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 1472–1483. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.13841215 (2016).

Oudin Åström, D., Forsberg, B., Ebi, K. L. & Rocklöv, J. Attributing mortality from extreme temperatures to climate change in stockholm, Sweden. Nat. Clim. Change. 3, 1050–1054. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2022 (2013).

Ghazani, M., FitzGerald, G., Hu, W., Toloo, G. & Xu, Z. Temperature variability and Gastrointestinal infections: a review of impacts and future perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15, 766 (2018).

Zhao, Q. et al. High ambient temperature and risk of hospitalization for Gastrointestinal infection in brazil: A nationwide case-crossover study during 2000–2015. Sci. Total Environ. 849, 157836 (2022).

Hall, G. V., Hanigan, I. C., Dear, K. B. & Vally, H. The influence of weather on community gastroenteritis in Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 139, 927–936. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268810001901 (2011).

Budd, G. M. Wet-bulb Globe temperature (WBGT)--its history and its limitations. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 11, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.003 (2008).

Andrews, O., Le Quéré, C., Kjellstrom, T., Lemke, B. & Haines, A. Implications for workability and survivability in populations exposed to extreme heat under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health. 2, e540–e547. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(18)30240-7 (2018).

Kakaei, H., Omidi, F., Ghasemi, R., Sabet, M. R. & Golbabaei, F. Changes of WBGT as a heat stress index over the time: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urban Clim. 27, 284–292 (2019).

Hsu, C. Y., Wong, P. Y., Chern, Y. R., Lung, S. C. & Wu, C. D. Evaluating long-term and high Spatiotemporal resolution of wet-bulb Globe temperature through land-use based machine learning model. J. Expo Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-023-00630-1 (2023).

Chen, C. H. et al. Population structure of Han Chinese in the modern Taiwanese population based on 10,000 participants in the Taiwan biobank project. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 5321–5331. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddw346 (2016).

Fan, C. T., Hung, T. H. & Yeh, C. K. Taiwan regulation of biobanks. J. Law Med. Ethics. 43, 816–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12322 (2015).

Inker, L. A. et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C-Based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl. J. Med. 385, 1737–1749. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2102953 (2021).

Hsu, C. Y. et al. Estimating morning and evening commute period O(3) concentration in Taiwan using a fine Spatial-temporal resolution ensemble mixed Spatial model with Geo-AI technology. J. Environ. Manage. 351, 119725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119725 (2024).

Seo, H. S., Hong, J. & Jung, J. Relationship of meteorological factors and air pollutants with medical care utilization for gastroesophageal reflux disease in urban area. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 6074 (2020).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 386, 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 (2015).

Ebi, K. L. et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet 398, 698–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3 (2021).

Konturek, P. C., Brzozowski, T. & Konturek, S. J. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 62, 591–599 (2011).

Van Nieuwenhoven, M., Vriens, B., Brummer, R. J. & Brouns, F. Effect of dehydration on Gastrointestinal function at rest and during exercise in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 83, 578–584 (2000).

Walsh, N. P. et al. Saliva parameters as potential indices of hydration status during acute dehydration. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36, 1535–1542 (2004).

Bouchoucha, M. et al. Relationship between acid neutralization capacity of saliva and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 105, 19–26 (1997).

Neufer, P., Young, A. & Sawka, M. Gastric emptying during exercise: effects of heat stress and hypohydration. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 58, 433–439 (1989).

Watanabe, H., Sugi, T., Saito, K. & Nagashima, K. Mechanism underlying the influence of humidity on thermal comfort and stress under mimicked working conditions. Physiol. Behav. 285, 114653 (2024).

Dobrek, L., Nowakowski, M., Mazur, M., Herman, R. & Thor, P. DISTURBANCES OF THE PARASYMPATHETIC BRANCH OF THE. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 55, 77–90 (2004).

Milovanovic, B. et al. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 21, 6982 (2015).

Weng, H. et al. Humid heat environment causes anxiety-like disorder via impairing gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in mice. Nat. Commun. 15, 5697 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Investigating the causal relationship of gut microbiota with GERD and BE: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization. BMC Genom. 25, 471 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a genetic correlation and bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 15, 1327503 (2024).

Harlan, S. L. et al. Heat-related deaths in hot cities: estimates of human tolerance to high temperature thresholds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 11, 3304–3326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110303304 (2014).

Asseng, S., Spänkuch, D., Hernandez-Ochoa, I. M. & Laporta, J. The upper temperature thresholds of life. Lancet Planet. Health. 5, e378–e385 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. Valley City ventilation under the calm and stable weather conditions: a review. Build. Environ. 194, 107668 (2021).

Li, G., Zhang, X., Mirzaei, P. A., Zhang, J. & Zhao, Z. Urban heat Island effect of a typical Valley City in china: responds to the global warming and rapid urbanization. Sustainable Cities Soc. 38, 736–745 (2018).

Chen, K. Y., Lin, H. C., Lou, H. Y. & Lee, S. H. Seasonal variation in the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 338, 453–458 (2009).

El-Serag, H. B., Graham, D. Y., Satia, J. A. & Rabeneck, L. Obesity is an independent risk factor for GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis. Official J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterology| ACG. 100, 1243–1250 (2005).

Westerterp, K. R. Seasonal variation in body weight: an experimental case study. J. Therm. Biol. 26, 525–527 (2001).

Shahar, D. R. et al. Changes in dietary intake account for seasonal changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 53, 395–400 (1999).

Wu, C. S., Lai, M. S., Gau, S. S., Wang, S. C. & Tsai, H. J. Concordance between patient self-reports and claims data on clinical diagnoses, medication use, and health system utilization in Taiwan. PLoS One. 9, e112257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112257 (2014).

Nguyen, J. L., Schwartz, J. & Dockery, D. W. The relationship between indoor and outdoor temperature, apparent temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity. Indoor Air. 24, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12052 (2014).

Funding

This work was supported partially by the Research Center for Precision Environmental Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan and by Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant (KMU-TC114A01), and Kaohsiung Municipal Siaogang Hospital (kmhk-113-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, and supervision: H-PT, C-DW, S-CC and C-HK. Software and investigation: S-CC and C-HK. Resources, project administration, and funding acquisition: S-CC. Data curation: C-CC, H-YH, T-YW, W-YS, T-HL, H-PT, C-DW, S-CC and C-HK. Writing—original draft preparation: C-CC and S-CC. Visualization: C-DW, S-CC and C-HK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was granted approval by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUHIRB-E(I)-20240338), and the TWB was granted approval by the IRB on Biomedical Science Research, Academia Sinica, Taiwan and the Ethics and Governance Council of the TWB.

Consent to participate

Informed consent to participate was obtained from all of the participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, CC., Huang, HY., Wu, TY. et al. Association between wet-bulb globe temperature with gastroesophageal reflux disease in different geographic regions in a large Taiwanese population study. Sci Rep 15, 21339 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07073-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07073-8