Abstract

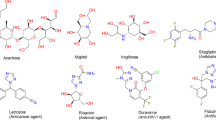

Twelve selected natural flavonoids (F1–F12) and their brominated derivatives (F1a–F12a) were investigated for their antidiabetic effects on α-glucosidase and α-amylase, as well as anti-glycation activity. The semisynthetic brominated flavonoids (F1a–F12a) were synthesized using brominating agents. Among the semisynthesized compounds, two semisynthetic compounds including 6,8-dibromoluteolin (F3a) and 6,8-dibromoalpinetin (F10a) were reported as new compounds. 8-Bromobaicalein (F4a, IC50 = 0.52 ± 0.05 µM) and 6,8-dibromoluteolin (F3a, IC50 = 0.99 ± 0.12 µM) were found as mixed-type potent agents on α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activities, respectively. In addition, 6,8-dibromochrysin (F1a, IC50 = 50.90 ± 0.98 µM) was found to be the most potent compound for inhibiting Bovine Serum Albumin - glycation (BSA-glycation) mediated methylglyoxal. The results of this study indicated that the introduction of bromine into flavonoids could benefit antidiabetic and anti-glycation due to the influence of the electronic effect and hydrophobic properties of bromine atoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a chronic metabolic disorder with a high global prevalence, is divided into two types namely type 1 DM which is generated by dysfunction of β-pancreatic cells, and type 2 DM which is caused by impairment of insulin secretion due to insulin resistance and results in disturbances in glucose homeostasis1,2. Type 2 DM is recognized as a major threat to human health and development and has emerged as one of the most prevalent public health issues3,4,5. In the case of type 2 DM, the condition could lead to an increase in blood glucose levels. The inhibition of the activities of α-glucosidase and α-amylase enzymes, which catalyze carbohydrate hydrolysis, is believed as one approach for controlling blood glucose levels6.

Over the last two decades, the demand for antidiabetic medications has risen quickly as DM becomes more prevalent7,8. One of the drugs used to treat type 2 DM and known to inhibit α-glucosidase and α-amylase activities, i.e. acarbose has some drawbacks including the side effects related to diarrhea and flatulence9. Moreover, its production still faces significant challenges that drive up manufacturing costs, one of which is through genetic engineering10.

On the other hand, diabetic patients tend to develop vascular complications, which are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality11. Chronic hyperglycemia resulting in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) facilitates diabetes-related complications, such as diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral neuropathy, atherosclerosis, and other complications12,13. The primary serum protein, albumin, has a number of roles and is very susceptible to several environmental factors, with glucose being one of the most significant14. During long-standing hyperglycemia states in DM, the steadily increasing glucose level tends to form covalent adducts with plasma proteins via a non-enzymatic process named glycation or Maillard reaction, resulting in the formation of AGEs15.

A class of compounds has been identified either to prevent the formation or to degrade existing AGEs, which have been manufactured and patented16,17. Aminoguanidine, which is known as the first AGEs inhibitor, could trap or scavenge the reactive carbonyl intermediates such as glyoxal and methylglyoxal (MG) in the glycation process18. However, a previous study revealed that the use of a high concentration of aminoguanidine was required to trap the reactive species due to its half-life in plasma is short19. This is one of the disadvantages of aminoguanidine which could generate serious toxicity when administered for diabetic nephropathy.

In terms of discovering effective drugs that could overcome the side effects of the reference drugs mentioned above, the researchers have a broad interest in studying the biological activities of natural products since they are well-known to have withdrawal symptoms20,21. Therefore, it is noteworthy to discover and further investigate the potency of secondary metabolites from natural products as new promising antidiabetic and anti-glycation agents.

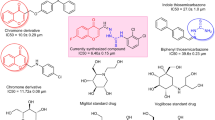

Flavonoids, one of the secondary metabolites, are known to possess antidiabetic and anti-glycation properties22,23. Due to their abundance in nature with known biological activities, flavones, flavonols, and flavanones can be highlighted among the several subclasses of flavonoids. Hence, it is exciting to explore the effectiveness of these constituents on antidiabetic and anti-glycation activities. Whereas, in this study, twelve selected natural flavonoids as portrayed in Fig. 1 were examined.

Moreover, halogenated secondary metabolites have received increased attention in drug discovery and medicinal chemistry in recent decades. The insertion of halogen atoms into the moiety structures of natural products or synthetic compounds has been known to affect biological activities24. Halogens, especially lighter fluorine and chlorine, are widely used substituents in medicinal chemistry25. In the case of bromine, many studies have been reported on the preparation of brominated flavonoids. In addition, a previous study reported that the brominated flavones exhibited better α-glucosidase inhibition compared with their parent compounds and found that the number of bromine atoms on the B-ring affected the biological activity26.

The introduction of bromine atoms into flavonoid structures could enhance the lipophilicity or hydrophobicity of compounds, which may improve membrane permeability and consequently bioavailability of compounds27. In comparison to the existing inhibitors, such as acarbose which is known to have limited bioavailability due to extensive metabolism in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by intestinal bacteria digestive enzymes which gives the drug side effects of the GI tract28. Moreover, several approved drugs currently in clinical use contain bromine atoms as part of their chemical structure27.

Hence, this study aims to investigate the effects of bromine atoms in the A-ring of the flavonoid scaffold on α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activities. Further investigation was carried out by performing the anti-glycation assay to examine whether those brominated flavonoids were also acting as glycation inhibitors which are further useful to treat diabetic complications. To date, this is the first report about the effects of those semisynthetic brominated flavonoids (flavones, flavonols, and flavanones) as antidiabetic and anti-glycation agents. All the selected natural flavonoids and their brominated compounds were examined on inhibitory activities against α-glucosidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and α-amylase from porcine pancreas. Moreover, since bovine serum albumin (BSA) could act as a model protein in the in vitro experiment, hence the study also focused on the activity of those compounds toward BSA-glycation mediated MG.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

In this study, four flavonoids including kaempferol (F5), pinocembrin (F8), pinostrobin (F9), and alpinetin (F10) were isolated from two plant materials. The isolation of F5 was carried out by further purification of the MeOH extract of the flowers of Impatiens balsamina L. using a silica gel column to yield F5 as a yellow powder (69%). On another hand, three flavanones including F8, F9, and F10 were isolated from the MeOH extract of the rhizome of Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. The purification of selected fractions by silica gel column and recrystallization furnished a colorless crystal of F8 (46%), pale-yellow powder of F9 (16%), and F10 (8.1%). The structures of these isolated flavonoids were identified by NMR analysis and compared with previously reported data29,30.

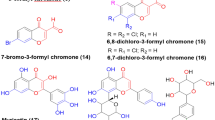

Several protocols to introduce the bromine atom on the A-ring of the flavonoid scaffold were carried out. The synthesis of bromoflavonoids including bromoflavones, bromoflavonols, and bromoflavanones is depicted in Fig. 2. The bromination of flavonoids is occurs selectively at the A-ring, specifically at C-6 and C-8 positions. This selectivity is influenced by the presence of electron-donating group (–OH) at 5- and 7- positions in the A-ring, as well as the double bond at C2=C3 in the C-ring. The presence of 5- and 7–OH groups (in F1–F3) increases the electron density in the A-ring, making it more susceptible to electrophilic attack by bromine31. In compound F4, the presence of additional –OH at C-6 further amplifies this effect. Even though B-ring also contains electron-donating groups (in F2, F3, F5, F6, F7, F11, and F12), the number of electron-donating groups are less than in the A-ring. Consequently, bromination preferentially occurs on A-ring.

To synthesize bromo derivatives of flavones (F1a–F3a), a modified method described by Hairani and Chavasiri was carried out32. The reaction was performed in the presence NaBr and oxone in acetone-H2O. The desired products F1a, F2a, and F3a were characterized by the absence of signals of 6- and 8- protons. The NMR spectral data of F1a, F2a, and F4a were also confirmed with those of the previous reports32,33,34. From this series, F3a is identified as a new semisynthetic compound. The selective bromination of baicalein at the C-8 position was carried out using a modified method described by Lee and coworkers using NBS in the presence of a catalytic amount of concentrated H2SO4 at room temperature to yield F4a and compared its NMR spectra with a previously reported data34. While, the preparation of F5a and F6a was performed by using NaBr and oxone in acetone-H2O, while, F7a could be attained by using Br2 in CH3COOH35. For bromoflavanones (F8a–F12a) could also be obtained by using NaBr and oxone in acetone-H2O at room temperature for overnight. Among these series, F10a was identified as a new semisynthetic compound.

Biological activity of natural flavonoids and their brominated compounds

In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory

All selected flavonoids and their bromo derivatives were screened in vitro for inhibitory α-glucosidase activity which was performed according to the previously described protocol32. Acarbose was used as a positive control. The inhibition results at 50 µM and IC50 values for the compounds that exhibited ≥50% inhibition toward α-glucosidase are described in Table 1. The criteria of IC50 value are categorized as follows: IC50 < 1 µM (very strong), IC50 = 1–10 µM (strong), IC50 = 10.1–30 µM (relatively strong), IC50 = 30.1–10 µM (moderate), IC50 = 100.1–200 µM (weak), IC50 > 200 µM (not active).

Table 1 shows various effects of bromine atoms on the inhibition of α-glucosidase. The introduction of bulky groups, such as bromine, can result in either antagonistic or agonistic behavior compared to the parent compound24. In this screening study, the brominated flavonoids generally exhibited enhanced activity relative to their parent compounds. Nonetheless, some derivatives displayed no significant effects from brominated flavonoids or demonstrated activity levels comparable to the starting material.

Among the flavones subclasses, baicalein (F4), which contains three –OH groups on the A-ring, exhibited the strongest inhibition, with 99.42% inhibition and an IC50 value of 0.58 µM. This result suggests that the number of the –OH groups on the A-ring of flavones may play a crucial role in enzyme inhibition, likely due to their ability to form additional interactions via hydrogen bonds and/or electrostatic interaction36. Although apigenin (F2) also possesses three –OH groups, one –OH group is located on the B-ring, consequently, the inhibitory activity of F2 was lower than that of baicalein (F4), showing 78.64% inhibition and an IC50 value of 22.74 µM. This finding supports the idea that –OH groups on the A-ring of flavones are more favorable for enzyme interaction. Notably, 5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone pattern appears to be particularly effective in enhancing α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, as stated by a previous study37. In contrast, luteolin (F3), which contains four –OH groups, exhibited only 34.37% inhibition. This suggests that the presence of the –OH group at the 3′-position on the B-ring may slightly reduce the inhibitory activity of the compound.

When comparing natural flavones and their bromo derivatives, the results showed that the introduction of bromine atoms at positions 6- and 8- on chrysin (F1a), apigenin (F2a), and luteolin (F3a) led to improved inhibitory activities compared to their parent compounds chrysin (F1), apigenin (F2), and luteolin (F3) with percentage inhibitions of 89.70, 81.98 and 95.08%, and IC50 values of 2.97, 15.32 µM, respectively. In contrast, brominated baicalein (F4a) showed only a slight increase or no significant effect in activity compared to its parent compound. This suggests that the introduction of a bromine atom at position 8- on flavones may have minimal or no beneficial effect on α-glucosidase inhibitory activity.

For flavonols, the results showed that the natural flavonols such as morin (F6) and quercetin (F7), which each contain five –OH groups, displayed better inhibitory activities than kaempferol (F5), which contains only four –OH groups. Although morin (F6) and quercetin (F7) have the same number of –OH groups, the differences in their positions significantly affect their ability to reduce α-glucosidase activity. Quercetin (F7), in particular, demonstrated strong inhibition with an IC50 value of 1.33 µM. This suggests that the catechol moiety (i.e., ortho –OH groups) present in F7 provides a greater advantage in α-glucosidase inhibitory activity over the meta –OH groups.

Moreover, among the brominated flavonols, F5a and F6a displayed relatively strong inhibitory activity and performed better than their parent compounds, with IC50 values of 13.89 and 8.28 µM, respectively. In contrast, brominated quercetin (F7a) did not have a crucial effect on α-glucosidase activity, in fact, its activity slightly declined compared to the parent compound. This reduction might be attributed to the increased molecular bulk, which could hinder the ability of a compound to access the active site of the enzyme. Nevertheless, F7a (IC50 = 3.90 µM) still showed a better effect than both F5a and F6a. In certain cases, the hydrophobicity of a compound plays an important role in enzyme interaction by enhancing hydrophobic interactions at the binding site. The octanol-water partition coefficient (log P) is commonly used to describe the hydrophilic or hydrophobic nature of a compound. A comparison of the calculated log P (cLog P) values showed that F7a (1.701) is more hydrophobic than F6a (1.331), which may account for a stronger inhibitory activity of F7a due to increased hydrophobic interactions with the enzyme.

Most of the natural flavanones and their brominated derivatives showed weak α-glucosidase inhibition, with the exception of compounds F11a and F12a, which demonstrated relatively strong activity. This observation indicates that the absence of a double bond at the C-2 and C-3 positions in flavanones reduces their α-glucosidase inhibitory potential. Compound F11a (IC50 = 13.63 µM) showed stronger inhibition than F12a (IC50 = 16.70 µM), likely due to the replacement of the –OH group at 4′-position with a -OMe group in F12a, which may slightly diminish its activity.

According to the findings, the structure-activity relationship of natural and brominated flavonoids can be rationalized into several important points, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Furthermore, a Lineweaver-Burk plot was established to illustrate the kinetic inhibition of α-glucosidase in the presence of F4a. The plot of 1/v versus 1/[p-NPG] for F4a, gave straight lines that intersected at the same point in the second quadrant, indicating that F4a acts as a mixed-type inhibitor (Fig. 4). This result indicates that F4a could bind to both the free enzymes and the enzyme-substrate complex, thereby reducing the catalytic activity of α-glucosidase.

In addition, the equilibrium binding constants of F4a to the free enzyme (Ki) and the enzyme-substrate complex (Kis) were determined using secondary plots from the Lineweaver-Burk analysis. Specifically, plots of the slope (Km/Vm) and y-intercept (1/Vm) versus various concentrations of F4a were used. From these calculations, the Ki value was found to be 1.37 µM, while the Kis value was 2.53 µM. The higher Kis value compared to Ki suggests that F4a has a greater binding affinity for the free enzyme than for the enzyme-substrate complex.

In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity

The α-amylase assay was performed in 96-well microplates using a final volume of 200 µL, following a previously described method with some modification38,39. Screening at 50 µM (Table 1) showed that flavone and flavonol subclasses demonstrated better inhibition of α-amylase compared to flavanones. This difference may be attributed to the presence of a double bond at positions C-2 and C-3 in flavones and flavonols, which could enhance their inhibitory effect on the enzyme. In contrast, flavanones exhibited relatively lower inhibition. Compounds that showed ≥70% inhibition of α-amylase were subsequently selected for their IC50 determination.

Among natural flavones, increasing the number of –OH groups generally enhanced the level of inhibition. For example, chrysin (F1), which has two –OH groups on the A-ring, showed only 22.59% inhibition. Nevertheless, the activity of the compound with an additional –OH group on the A-ring (F4) was four times greater than that of F1. Even higher inhibitory activity was observed when the additional –OH groups were present on the B-ring, compounds F2 (with one additional –OH) and F3 (with two additional –OH groups) exhibited IC50 values of 13.18 and 2.18 µM, respectively. These results indicate that –OH groups increase the number of interactions between the compound and the enzyme, leading to stronger inhibition. A similar trend was also observed among natural flavonols. Kaempferol (F5), consisting of four –OH groups, had an IC50 value of 10.43 µM, while quercetin (F7) with five –OH groups displayed an IC50 value of 11.16 µM. In contrast, morin (F6) demonstrated weaker activity than F7 due to the different position of –OH groups (meta). Furthermore, the results revealed that luteolin (F3) was more active than quercetin (F7) which indicates that the presence of an –OH group at the 3-position on the C-ring is not essential for α-amylase inhibitory activity. This finding aligns with a previous study indicating that –OH groups at the 4′- and 5′-position on the B-ring significantly increase the inhibitory activity against α-amylase37. In contrast, natural flavanones and their brominated derivatives displayed weak or negligible activity toward α-amylase, with percent inhibition ranging from 12.85 to 51.13%.

The introduction of bromine atoms into the flavonoid scaffold provided varied effects on α-amylase inhibition. Among the tested compounds, F3a displayed the highest inhibitory activity, with an IC50 value of 0.99 µM – approximately six-fold more potent than the reference drug acarbose (IC50 value of 6.73 µM).

Based on these findings, the structure-activity relationship of natural and brominated flavonoids can be summarized into several key points as depicted in Fig. 5.

The Lineweaver-Burk plot was also generated to illustrate the kinetic inhibition of α-amylase in the presence of F3a. The plot of 1/v versus 1/[CNP-G3] for F3a showed the straight lines intersecting at the same point in the second quadrant, indicating that F3a acts as a mixed-type inhibitor (Fig. 6). This suggests that F3a can bind to both the free enzymes and the enzyme-substrate complex, thereby reducing the catalytic activity of α-amylase.

Moreover, the equilibrium binding constants of F3a to the free enzyme (Ki) and the enzyme-substrate complex (Kis) through plots of slope (Km/Vm) and vertical intercept (1/Vm) versus F3a with various concentrations were also determined. The Ki value was found to be 0.18 µM, while the Kis value was 0.37 µM, suggesting that the affinity of F3a with the free enzyme was higher than that with the enzyme-substrate complex.

In vitro BSA-glycation mediated methyglyoxal (MG) inhibitory activity

An elevated glucose level is known as the typical indicator of diabetes mellitus (DM), in which glucose as a reducing sugar, promotes the non-enzymatic glycation of various proteins, particularly plasma proteins such as albumin14. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is commonly used as a model protein for in vitro glycation studies. Glycation of BSA can be induced by highly reactive dicarbonyl species such as methylglyoxal (MG), which react with proteins to form irreversible heterogeneous advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). In this study, the effect of the tested compounds was evaluated using an in vitro BSA-glycation mediated by MG.

All selected flavonoids (F1–F12) and their brominated derivatives (F1a–F12a) were evaluated for their anti-glycation potential. According to the screening result at a concentration of 500 μM (Table 2), several flavonoids and their brominated derivatives significantly inhibited BSA-glycation mediated by MG, with percent inhibition ranging from 93.40 to 99.75%, surpassing that of the positive control, aminoguanidine hydrochloride (79.66%). Flavones and their brominated derivatives exhibited inhibition ranging from 35.56 to 97.82%, while inhibition ranging from 60.85 to 99.75% was shown by flavonols and their brominated derivatives. In addition, flavanones and their brominated compounds displayed inhibition in the range of 11.90–96.53%.

Among natural flavones, the increasing trend in percent inhibition was observed by increasing the number -of OH groups with the order: chrysin (F1) < apigenin (F2) < baicalein (F4) < luteolin (F3). This phenomenon indicates that the –OH groups play a crucial role in inhibiting the glycation process because of their ability to form intermolecular hydrogen bonds. A higher number of hydrogen bonds is associated with lower energy barriers, thereby enhancing inhibitory activity40. Moreover, the C=O group on the C-ring may facilitate intermolecular H-bond formation, in which the flavonoid could effectively hinder the AGEs formation40. In addition, previously, it has been reported that the –OH group at the 5-position on the A-ring was essential for trapping MG by flavonoids41.

Furthermore, two brominated flavones (F1a and F2a) exhibited stronger anti-glycation activity than their parent compounds (F1 and F2). This implies that the presence of bromine atoms on the A-ring may enhance the activity, possibly due to the fact that halogens can act as hydrogen bond acceptors and contribute favorably to molecular binding. In contrast, F4a, which contains one bromine atom at the 8-position on the A-ring, exhibited lower inhibition compared to its parent compound (F4). This described that the presence of bromine atom at the 8-position did not give a beneficial effect on the activity. Notably, the introduction of bromine atom at the 6-position on the A-ring of flavone appeared to enhance the inhibition of the glycation process. However, this outcome only occurred for flavone containing two –OH groups on the A-ring and one additional –OH group on the B-ring. For example, 6,8-dibromoluteolin (F3a) with two more additional –OH groups on the B-ring displayed no increased effect compared with its parent compound luteolin (F3). This specified that the inhibition was favored when the inhibitor was not a bulky compound that may offer steric hindrance.

In the case of natural flavonols, a similar trend was observed, where an increased number of –OH groups correlated with greater inhibition of glycation. The percent inhibition followed the order: kaempferol (F5) < morin (F6) < quercetin (F7). Albeit F6 and F7 contain the same number of –OH groups, due to the different positions, the activity showed a slightly dissimilar effect. This denotes that the catechol moiety on the B-ring was favored over the meta–OH. In addition, the introduction of bromine atoms at 6- and 8- positions of flavonols (F5a–F7a) exhibited a decrease in inhibition compared with their starting materials. This due to the bulky compounds were generated from this series of derivatives leading to the difficulty of accessing the inhibition.

For flavanones, the importance of the –OH group at the 5-position of flavonoids was also observed when investigating pinocembrin (F8) containing two –OH group at 5,7-positions, and pinostrobin (F9) with one –OH group at 7-position and one -OMe group at 5-position, displayed a significant difference in the inhibition. The same result was also observed when the 7–OH was replaced by 7-OMe which was possessed by alpinetin (F10), which revealed that the –OH group at the 7-position played a crucial role in inhibiting the glycation process. Furthermore, the increase of the number –OH groups in flavanones was also essential for the activity, for instance, pinocembrin (F8) contained two –OH groups on the A-ring with inhibition of 47.60%, then underwent slightly increased inhibition for naringenin (F11) which contained one more additional –OH group on the B-ring with inhibition of 56.89%. But then slightly reduced the inhibition level once the –OH group at 4-position in the B-ring was replaced by -OMe, even though compound F12 contained one more –OH group at 3′-position on the B-ring. This revealed that the –OH group at the 4′-position in the B-ring of flavanone was favored over the 3′-position. As stated in a previous study the presence of one –OH and one -OMe group showed varied activity depending upon the position of the –OH substituent, whereas a compound with an ortho hydroxy was found to be a not good inhibitor42.

Subsequently, several selected compounds that exhibited percent inhibition ≥ 80% were further investigated for their IC50 values by varying the concentrations as depicted in Table 2. The criteria of IC50 value is categorized as follows: IC50 < 10 µM (very strong), IC50 = 10.1 – 100 µM (strong), IC50 = 100.1 – 200 µM (relatively strong), IC50 = 200.1 – 300 µM (moderate), IC50 = 300.1–500 µM (weak), IC50 > 500 µM (not active).

According to the results, 6,8-dibromochrysin (F1a) showed the highest inhibition with an IC50 value of 50.90 µM, followed by compounds F2a (IC50 = 57.01 µM), F6a (IC50 = 61.22 μM), F11a (IC50 = 64.51 µM), F7 (IC50 = 68.47 µM), F3a (IC50 = 79.48 µM), and F3 (IC50 = 85.63 µM), in which these compounds displayed strong inhibition toward the BSA-glycation process mediated MG. It seems that the anti-glycation activity tends to favor less bulky compounds. Additionally, morin (F6) showed a relatively strong effect as an anti-glycation agent with an IC50 value of 132.45 µM. All of these selected compounds showed 2- to 6-fold greater potency compared to the standard drug aminoguanidine hydrochloride (IC50 = 240.05 µM).

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that brominated flavonoids can act as promising agents for the treatment of diabetes and its complications. Among the tested compounds (flavonoids and their brominated derivatives), F4a was found as a very strong inhibitor toward α-glucosidase, while the new semisynthetic compound F3a exhibited the highest inhibition against α-amylase. Both compounds show great potential as lead compounds for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). In addition, F1a–F3a, F6a, and F11a displayed strong inhibitory effects, outperforming the standard drug. Moreover, in terms of discovering new potent for treating diabetes mellitus complications, the anti-glycation property of flavonoids and their brominated derivatives was examined and found that F1a exhibited the highest inhibition. Overall, the introduction of bromine atoms into the flavone scaffold offers a promising approach for developing new antidiabetic and anti-glycation agents. Bromine may act as a hydrogen bond acceptor, enhancing the binding affinity of the compound to the enzyme. Moreover, the presence of a bromine atom in flavonoid structure may also increase the hydrophobic interactions between compound and enzyme, further contributing to biological activity. Another issue related to the bulky compound once the bromine atom is inserted into flavonoid moiety also could explain why the activity decreases. However, further studies are required to fully elucidate the biomolecular mechanism through which brominated flavonoids exert their antidiabetic effects and to assess their potential as effective treatments for diabetes and related complications. It is also crucial to evaluate the cytotoxicity of these compounds against normal cell lines which is essential for their potential use as therapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Materials

Plant materials

Two plant materials were used in this work including the rhizomes of Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. which was purchased from the herbal drug store in Bangkok-Thailand, and the flowers of Impatiens balsamina L. was collected from Indonesia.

Equipment and instruments

1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) spectra were recorded with a JEOL spectrometer (JNM-ECZ500R/S1) while 1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 AVANCE spectrometer, and chemical shifts were recorded in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J) were given in Hertz. The LC-QTOF-MS/MS analysis was performed on an Agilent HPLC 1260 series coupled with a QTOF 6540 UHD accurate mass (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The fluorescence intensity was measured by the EnSight Multimode Plate Reader PerkinElmer.

Chemicals

Chrysin, apigenin, luteolin, baicalein, quercetin hydrate, naringenin, and hesperetin were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry company, while morin was bought from Fluka and used without further purification. Other synthetic reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich company or otherwise stated. All solvents used in this study were purified by standard methods, except for those which were reagent grades. The progress of the reaction was monitored by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) using TLC silica gel 60 F254 Merck. Purification of semisynthetic compounds was performed by column chromatography using silica gel (70-230 mesh) of SiliaFlash® G60 (Canada). α-Glucosidase (Sigma G5003) derived from Baker’s yeast, α-amylase from porcine pancreas type VI-B, 4-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside (p-NPG, Sigma N1377), 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl α-D-maltotrioside (CNP-G3), methylglyoxal solution, acarbose, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Aminoguanidine hydrochloride was used as a positive control for anti-glycation and was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry company.

Methods

Isolation of kaempferol (F5) from impatiens Balsamina L. flowers

The dried and powdered Impatiens balsamina L. flowers (272 g) was done by maceration in MeOH for three days at room temperature, filtered, and concentrated by a rotary evaporator. This step was repeated three times to obtain the dark brown MeOH crude extract (97.62 g, 36%). This crude extract was then partitioned with EtOAc and H2O and separated. EtOAc fraction was then concentrated to obtain 38.82 g of EtOAc extract. Subsequently, this fraction was subjected to silica gel column which was initially eluted with hexane-EtOAc and EtOAc-MeOH by increasing polarity to give five fractions (1–5). The precipitate from the fraction 1 was then collected and washed with hexane:EtOAc (1:1) to give kaempferol (F5) as yellow powder (92 mg). Fraction 2 (1.46 g) was then further purified by using silica gel column and eluted with hexane-EtOAc to give six subfractions (2a–2f). Subfractions 2d and 2e formed precipitates. Washing the precipitate using hexane:EtOAc (1:1) gave 1.0 g of kaempferol (F5).

Kaempferol (F5): yellow powder (0.4%), 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 12.47 (s, 5–OH), 10.80 (s, 3–OH), 10.12 (s, 7–OH), 9.37 (s, 4′–OH), 8.04 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), and 6.19 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 175.9, 163.9, 160.7, 159.2, 156.2, 146.9, 135.7, 129.5, 121.7, 115.5, 103.1, 98.2, and 93.5.

Isolation of pinocembrin (F8), pinostrobin (F9) and alpinetin (F10) from Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. rhizomes

The extraction of the dried and powdered Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. rhizomes (5.0 kg) was done by maceration in MeOH for three days at room temperature, filtered, and concentrated by a rotary evaporator. This step was repeated three times to obtain the dark brown MeOH crude extract (700 g, 14%). This crude extract was then subjected to silica gel column which was initially eluted with hexane-EtOAc and EtOAc-MeOH by increasing polarity to give seven fractions. Washing the precipitate in fraction 5 using EtOAc gave pinocembrin (F8) as pale-yellow solid 113 g (16%). After recrystallization of precipitates from fractions 2, 3, and 4 with hexane and EtOAc, pinostrobin (F9) as colorless crystal 320 g (46%) was attained. In addition, recrystallization of the precipitate in fraction 6 using CH2Cl2 and MeOH, furnished alpinetin (F10) as a pale-yellow solid 57 g (8.1%).

Pinocembrin (F8): pale-yellow solid (16%), 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ (ppm) 12.16 (s, 5–OH), 9.76 (s, 7–OH), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (m, 3H), 6.00 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.57 (dd, J = 13.0, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.17 (dd, J = 17.0, 12.5 Hz, 1H), and 2.81 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ (ppm) 196.8, 167.4, 165.2, 164.1, 140.0, 129.4, 127.3, 103.2, 96.9, 95.9, 79.9, and 43.5.

Pinostrobin (F9): colorless crystal (46%), 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 12.02 (s, 5–OH), 7.42 (m, 5H), 6.08 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.42 (dd, J = 13.5, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.09 (dd, J = 17.0, 13.0 Hz, 1H), and 2.83 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 196.3, 168.5, 164.3, 162.9, 138.5, 129.0, 126.3, 103.3, 95.3, 94.4, 79.4, 55.8, and 43.5.

Alpinetin (F10): pale-yellow solid (8.1%), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 10.57 (s, 7–OH), 7.49 (dd, J = 6.5, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (m, 3H), 6.04 (dd, J = 35.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (dd, J = 12.5, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 2.98 (dd, J = 16.5, 12.5 Hz, 1H), and 2.62 (dd, J = 16.5, 3.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 187.4, 164.4, 164.1, 162.2, 139.2, 128.5, 128.3, 126.5, 104.5, 95.7, 93.4. 78.1, 55.6, and 44.9.

Synthesis of bromoflavones

Bromination of chrysin, apigenin and luteolin was performed according to the previously method32. 6,8-Dibromochrysin (F1a) was obtained by reacting Chrysin (F1,1 mmol) in acetone:water 5:1 and NaBr (3 mmol). After cooling, oxone (3 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The final solution was treated with Na2S2O3 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was recrystallized from MeOH to yield 92% yellow powder as a brominated product (F1a). The same procedure was applied for synthesizing 6,8-dibromoapigenin (F2a) and 6,8-dibromoluteolin (F3a).

While the brominated baicalein (F4a) was obtained by mixing 1 mmol baicalein (F4) and 1 mmol N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) in 4.0 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF) in the presence of 5.0 µL concentrated H2SO4 as described by a previously method34. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h before extraction with EtOAc. The precipitated product was washed with 10% aqueous NaHSO4 solution, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was recrystallized from MeOH to the target compound (58%) as a yellow powder.

6,8-Dibromochrysin (F1a): yellow powder (92% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 8.10 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (m, 3H), and 7.14 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 181.6, 163.5, 157.5, 157.1, 152.3, 132.6, 130.3, 129.3, 126.5, 105.2, 105.1, 94.6, and 88.5.

6,8-Dibromoapigenin (F2a): yellow powder (95% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 8.00 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (s, 1H), and 7.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 181.5, 164.3, 161.8, 157.2, 157.1, 152.2, 128.8, 120.8, 116.3, 116.1, 104.9, 94.4, and 88.4.

6,8-Dibromoluteolin (F3a): yellow powder (97% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 7.52 (d, J = 10 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), and and 6.89 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 181.3, 164.4, 157.4, 157.1, 152.2, 150.3, 145,9, 121.1, 119.4, 116.1, 113.7, 104.7, 102.7, 94.5, and 88.4. HRMS m/z (ESI+): calculated for C15H8Br2O6 ([M+H]+): 442.8766, found 442.8756.

8-Bromobaicalein (F4a): yellow powder (58% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMS0-d6) δ (ppm) 8.12 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (m, 3H), and 7.06 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 182.2, 163.0, 151.6, 146.7, 146.4, 132.3, 130.7, 129.7, 129.4, 126.4, 104.7, and 87.0.

Synthesis of bromoflavonols

The preparation of 6,8-dibromokaempferol (F5a) and 6,8-dibromomorin (F6a) were performed by using a previously method.32. By mixing the flavonol (1 mmol) with NaBr (3 mmol) and oxone (3 mmol) in acetone and H2O (5:1) for 3 hours. Then, the reaction was stopped by pouring the mixture into H2O and treating with Na2S2O3. The filtration was carried out and washed the residue with H2O. Recrystallized the residue with MeOH to get the desired product.

While 6,8-dibromoquercetin (F7a) was obtained as described by a previously method35. The target compound was synthesized by mixing quercetin (F7, 1 mmol) with diluted Br2 (1 mL in 5 mL CH3COOH) at 35°C for 3 days. Filtered the precipitate, washed with H2O, and recrystallized from MeOH to get the product.

6,8-Dibromokaempferol (F5a): light yellow powder (34% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.41 (s, 5–OH), 10.29 (s, 3–OH), 9.88 (s, 7–OH), 8.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), and 6.96 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 175.5, 159.8, 156.9, 156.4, 150.9, 147.8, 136.1, 129.8, 121.6, 115.8, 104.3, 93.7, and 88.0.

6,8-Dibromomorin (F6a): light yellow powder (53% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.53 (s, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), and 6.40 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm) 176.2, 160.6, 159.7, 156.8, 156.4, 153.0, 147.7, 136.9, 134.1, 110.7, 104.4, 103.9, 98.6, 98.2, and 86.0.

6,8-Dibromoquercetin (F7a): light yellow powder (36% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ (ppm) 7.32, (d J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), and 6.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ (ppm) 195.5, 160.0, 159.6, 154.6, 147.0, 145.1, 124.8, 121.9, 117.3, 115.2, 108.9, 101.6, 91.7, and 90.9.

Synthesis of bromoflavanones

Flavanone (1 mmol) was mixed with acetone and H2O (5:1), then NaBr (3 mmol) was added and stirred for 5 minutes. Subsequently, oxone (3 mmol) was added to the mixture solution and stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The mixture was poured into H2O, then treated with Na2S2O3 and filtered. The residue was then washed with H2O. Recrystallized the residue with MeOH to obtain the target compound.

6,8-Dibromopinocembrin (F8a): white powder (69% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.54 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (m, 3H), 5.78 (dd, J = 12.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (dd, J = 17.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), and 2.99 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 196.5, 159.3, 158.5, 157.7, 138.2, 128.8, 126.5, 102.9, 91.0, 90.0, 79.2, 79.1, and 41.2.

6,8-Dibromopinostrobin (F9a): yellow powder (75% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.46 (m, 5H), 5.59 (dd, J = 12.5, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.17 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.5 Hz, 1H), and 3.04 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 196.7, 162.5, 159.3, 158.1, 137.5, 129.2, 129.1, 126.0. 106.3, 98.7, 97.0, 79.6, 61.1, and 42.8.

6,8-Dibromoalpinetin (F10a): white powder (87% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.54 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (m, 3H), 5.74 (dd, J = 12.5, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.16 (dd, J = 16.5, 12.5 Hz, 1H), and 2.85 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 187.6, 158.8, 157.4, 157.3, 138.5, 128.7, 128.6, 126.3, 109.8, 101.1, 95.7, 78.8, 61.1, and 43.8. HRMS m/z (ESI+): calculated for C16H12Br2O4 ([M+H]+): 426.9181, found 426.9170.

6,8-Dibromonaringenin (F11a): white powder (65% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.34 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (dd, J = 13.0, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (dd, J = 17.0, 12.0 Hz, 1H), and 2.88 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 197.0, 159.2, 158.5, 158.0, 157.9, 128.3, 128.3, 115.4, 102.9, 90.8. 89.9, 79.3, and 41.2.

6,8-Dibromohesperetin (F12a): white powder (98% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 6.95 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (dd, J = 12.0 , 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.33 (dd, J = 17.0, 12.0 Hz, 2H), and 2.90 (dd, J = 17.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H);13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 196.9, 159.3, 158.6, 157.8, 148.2, 146.6, 130.5, 117.9, 114.1, 112.1, 102.9, 90.9, 90.0, 79.2, 55.8, and 41.3.

In vitro α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

The determination of α-glucosidase inhibitory of selected natural flavonoids and their brominated was performed according to the previously described protocol32. The stock solution of tested compounds and acarbose were dissolved in DMSO and further diluted with phosphate buffer pH 6.9, α-glucosidase and the substrate p-NPG were both dissolved in phosphate buffer pH 6.9. About 10 µL of the tested compound was inserted into a well of 96-wells microplate followed by adding 40 µL of α-glucosidase which was then preincubated at 37°C for 10 minutes by shaking at 500 rpm. Subsequently, 50 µL of substrate p-NPG was added, and the incubation was continued at 37°C for 30 minutes by shaking at 500 rpm. Finally, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 µL of 1 M Na2CO3. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a microplate reader. Inhibitory activity was calculated by Equation 1.

where A0 was the absorbance of blank (contained the same volume of the buffer solution instead of the tested compound); At was the absorbance of the reaction in the presence of a tested compound, α-glucosidase, and substrate p-NPG. The IC50 values were defined as the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the α-glucosidase activity under the assay conditions. The inhibition assay was performed in triplicate and in two independent experiments for all tested compounds.

In vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity

The ⍺-amylase assay was performed in 96-well microplates using a final volume of 200 µL as the previous method with some modification38,39. Unless otherwise stated, experiments were performed with phosphate buffer (0.1 mM) containing 0.02% NaN3 and adjusted to pH 6.0 with 2.0 M H3PO4. Stock solutions of α-amylase and CNP-G3 in phosphate buffer were prepared at concentrations of 1 mg/mL and 0.5 mM, respectively. Enzymatic reaction mixtures consisted of test compound (10 µL), potassium phosphate buffer (140 µL), an enzyme (20 µL), then preincubated in phosphate buffer at 37°C for 10 minutes by shaking at 500 rpm. Subsequently, the substrate (30 µL) was incubated at 37° C for 30 minutes. Enzymatic activity was detected by spectrophotometry at 405 nm. Inhibitory activity was calculated by Equation 1. The IC50 values were defined as the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the α-amylase activity under the assay conditions. The IC50 value was further determined for the tested samples that show the inhibition ≥ 70%. For all tested compounds, the inhibition assay was performed in triplicate and two-independent experiments.

Inhibitory kinetic analysis of selected compounds against enzymes

The inhibition types of 8-bromobaicalein (F4a) towards α-glucosidase and 6,8-dibromoluteolin (F3a) towards α-amylase were determined from Lineweaver-Burk plots. Typically, three different concentrations of each compound around the IC50 value were chosen. The inhibition type was determined using various concentrations of p-NPG substrate for α-glucosidase and CNP-G3 for α-amylase.

Anti-glycation activity

In brief, Bovine Serum Albumin solution (10 mg/mL) was prepared in 0.1 M of phosphate buffer pH 7.4 containing 0.02% NaN3. In addition, 14 mM methylglyoxal (MG) was prepared in a phosphate buffer. The test compound and standard inhibitor were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). About 20 µL of inhibitor, 80 µL of phosphate buffer, and 50 µL of 14 mM MG were mixed in the 96-well and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After preincubation, 50 µL of BSA was added to initiate the reaction. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 1 day. After incubation, each sample was examined for the development of specific fluorescence (excitation 370 nm; emission 450 nm) against a blank (without inhibitor) on a microplate reader and then calculated as Equation 2.

Afterward, the IC50 value was further investigated for the tested compounds that show inhibition ≥ 80%. For all tested compounds, the inhibition assay was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and in two independent experiments. The inhibition percentage and or IC50 values were calculated by using Microsoft Excel version 16.64 and a GraphPad Prism version 9. The data are expressed as means of two independent experiments ± standard deviations. cLog P values were obtained from ChemDraw Professional 16.0.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Rammohan, A., Bhaskar, B. V., Venkateswarlu, N., Gu, W. & Zyryanov, G. V. Design, synthesis, docking and biological evaluation of chalcones as promising antidiabetic agents. Bioorg. Chem. 95, 103527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103527 (2020).

Antar, S. A. et al. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; A gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 168, 115734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115734 (2023).

Abdul Basith Khan, M. et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes — Global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 10, 107–111. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.191028.001 (2020).

Chaudhury, A. et al. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: Implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 8, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00006 (2017).

Sun, H. et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119 (2022).

Gong, L. et al. Inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase: Potential linkage for whole cereal foods on prevention of hyperglycemia. Food Sci Nutr 8, 6320–6337. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1987 (2020).

Salehi, B. et al. Antidiabetic potential of medicinal plants and their active components. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9100551 (2019).

Zhao, Q., Xie, H., Peng, Y., Wang, X. & Bai, L. Improving acarbose production and eliminating the by-product component C with an efficient genetic manipulation system of Actinoplanes sp. SE50/110. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2, 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synbio.2017.11.005 (2017).

Dong, Y. et al. Reducing the intestinal side effects of acarbose by baicalein through the regulation of gut microbiota: An in vitro study. Food Chem. 394, 133561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133561 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Enhancement of acarbose production by genetic engineering and fed-batch fermentation strategy in Actinoplanes sp. SIPI12–34. Microb. Cell Factor. 21, 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-022-01969-0 (2022).

Wahidin, M. et al. Projection of diabetes morbidity and mortality till 2045 in Indonesia based on risk factors and NCD prevention and control programs. Sci. Rep. 14, 5424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54563-2 (2024).

Yingrui, W., Zheng, L., Guoyan, L. & Hongjie, W. Research progress of active ingredients of Scutellaria baicalensis in the treatment of type 2 diabetes and its complications. Biomed. Pharmacother 148, 112690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112690 (2022).

Khalid, M., Petroianu, G. & Adem, A. Advanced glycation end products and diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and perspectives. Biomolecules 12, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12040542 (2022).

Zurawska-Plaksej, E., Rorbach-Dolata, A., Wiglusz, K. & Piwowar, A. The effect of glycation on bovine serum albumin conformation and ligand binding properties with regard to gliclazide. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 189, 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2017.08.071 (2018).

Singh, V. P., Bali, A., Singh, N. & Jaggi, A. S. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 18, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1 (2014).

Rasheed, S., Sánchez, S. S., Yousuf, S., Honoré, S. M. & Choudhary, M. I. Drug repurposing: In-vitro anti-glycation properties of 18 common drugs. PLoS ONE 13, e0190509. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190509 (2018).

Song, Q., Liu, J., Dong, L., Wang, X. & Zhang, X. Novel advances in inhibiting advanced glycation end product formation using natural compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 140, 111750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111750 (2021).

Wang, L., Jiang, Y. & Zhao, C. The effects of advanced glycation end-products on skin and potential anti-glycation strategies. Exp. Dermatol. 33, e15065. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.15065 (2024).

Nagai, R., Murray, D. B., Metz, T. O. & Baynes, J. W. Chelation: a fundamental mechanism of action of AGE inhibitors, AGE breakers, and other inhibitors of diabetes complications. Diabetes 61, 549–559. https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1120 (2012).

Elosta, A. G. Natural products as anti-glycation agents: possible therapeutic potential for diabetic complications. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 8, 92–108. https://doi.org/10.2174/157339912799424528 (2012).

Thrikawala, V. S., Deraniyagala, S. A., Dilanka Fernando, C. & Udukala, D. N. In vitro α-amylase and protein glycation inhibitory activity of the aqueous extract of Flueggea leucopyrus Willd. J. Chem. 2018, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2787138 (2018).

Al-Ishaq, R. K., Abotaleb, M., Kubatka, P., Kajo, K. & Busselberg, D. Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: Cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9090430 (2019).

Zhou, Q., Cheng, K.-W., Xiao, J. & Wang, M. The multifunctional roles of flavonoids against the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and AGEs-induced harmful effects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 103, 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2020.06.002 (2020).

Hernandes, M. Z., Cavalcanti, S. M., Moreira, D. R., de Azevedo Junior, W. F. & Leite, A. C. Halogen atoms in the modern medicinal chemistry: Hints for the drug design. Curr. Drug Targets 11, 303–314. https://doi.org/10.2174/138945010790711996 (2010).

Wilcken, R., Zimmermann, M. O., Lange, A., Joerger, A. C. & Boeckler, F. M. Principles and applications of halogen bonding in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J. Med. Chem. 56, 1363–1388. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm3012068 (2013).

Dao, T.-B.-N. et al. Flavones from Combretum quadrangulare growing in Vietnam and their alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Molecules 26, 2531. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092531 (2021).

Potapskyi, E. et al. Introducing bromine to the molecular structure as a strategy for drug design. J. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.20883/medical.e1128 (2024).

Xu, S. M. et al. Method for evaluating the human bioequivalence of acarbose based on pharmacodynamic parameters. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060520960317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520960317 (2020).

Napolitano, J. G., Lankin, D. C., Chen, S. N. & Pauli, G. F. Complete 1H NMR spectral analysis of ten chemical markers of Ginkgo biloba. Magn. Reson. Chem. 50, 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.3829 (2012).

Poungcho, P., Hairani, R., Chaotham, C., De-Eknamkul, W. & Chavasiri, W. Methoxylated chrysin and quercetin as potent stimulators of melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 3281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073281 (2025).

Justino, G. C., Rodrigues, M., Florencio, M. H. & Mira, L. Structure and antioxidant activity of brominated flavonols and flavanones. J. Mass Spectrom 44, 1459–1468. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.1630 (2009).

Hairani, R. & Chavasiri, W. A new series of chrysin derivatives as potent non-saccharide α-glucosidase inhibitor. Fitoterapia 163, 105301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2022.105301 (2022).

Li, Y., Cai, S., He, K. & Wang, Q. Semisynthesis of polymethoxyflavonoids from naringin and hesperidin. J. Chem. Res. 38, 287–290. https://doi.org/10.3184/174751914X13966139490181 (2014).

Boonyasuppayakorn, S. et al. The 8-bromobaicalein inhibited the replication of dengue, and Zika viruses and targeted the dengue polymerase. Sci. Rep. 13, 4891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32049-x (2023).

Peng, M., Liu, F., Feng, X., Yang, F. & Yang, X. Synthesis of brominated quercetin derivatives using distinct brominating systems. Asian J. Chem. 26, 4701–4703. https://doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2014.16175 (2014).

Şöhretoğlu, D. & Sari, S. Flavonoids as alpha-glucosidase inhibitors: mechanistic approaches merged with enzyme kinetics and molecular modelling. Phytochem. Rev. 19, 1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-019-09610-6 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Wang, M. & Huang, G. Structure-activity relationship and interaction mechanism of nine structurally similar flavonoids and α-amylase. J. Funct. Foods 86, 104739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2021.104739 (2021).

Okutan, L., Kongstad, K. T., Jager, A. K. & Staerk, D. High-resolution alpha-amylase assay combined with high-performance liquid chromatography-solid-phase extraction-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy for expedited identification of alpha-amylase inhibitors: Proof of concept and alpha-amylase inhibitor in cinnamon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 11465–11471. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf5047283 (2014).

Sun, H. et al. Natural prenylchalconaringenins and prenylnaringenins as antidiabetic agents: alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase inhibition and in vivo antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 1574–1581. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05445 (2017).

Rezazadeh, S., Ebrahimi, A. & Nowroozi, A. The effects of structural properties on the methylglyoxal scavenging mechanism of flavonoid aglycones: A quantum mechanical study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1118, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2017.09.001 (2017).

Shao, X. et al. Essential structural requirements and additive effects for flavonoids to scavenge methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 62, 3202–3210. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf500204s (2014).

Taha, M. et al. Synthesis of 4-methoxybenzoylhydrazones and evaluation of their antiglycation activity. Molecules 19, 1286–1301. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19011286 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Chulalongkorn University–Graduate Programme Scholarship for ASEAN and NON-ASEAN Countries Academic Year 2019 for supporting Ms. Rita Hairani to study at Chulalongkorn University. Ms. R. Hairani is also grateful to Graduate School Thesis Grant, Chulalongkorn University for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. performed all experiments including preparation of all compounds, in vitro ⍺-glucosidase and ⍺-amylase inhibitory activity assay, as well as anti-glycation activity. W.C. designed the synthesis of bromoflavonoids, supervised the study, provided critical discussion, and prepared the manuscript to be published. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hairani, R., Chavasiri, W. Synthesis of promising brominated flavonoids as antidiabetic and anti-glycation agents. Sci Rep 15, 25517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09040-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09040-9