Abstract

Adequate antenatal care (ANC) is crucial for improving pregnancy outcomes through preventive and promotive interventions. Despite WHO standards for regular check-ups, screenings, and counseling, compliance in Ethiopia’s pastoral areas, particularly Afar, is underexplored. This study assessed adequate ANC receipt and its associated factors among 704 women who delivered in public hospitals in Afar, Northeast Ethiopia. Data were collected from May 1 to 30, 2024, using structured interviews administered via Kobo Toolbox. Analysis was performed using STATA version 17. Bivariable with \(\:\text{P}-\text{v}\text{a}\text{l}\text{u}\text{e}\le\:0.2\:\)and multivariable with \(\:\text{P}-\text{v}\text{a}\text{l}\text{u}\text{e}\:\le\:0.05\) binary logistic regressions were performed. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals were reported to identify factors associated with adequate ANC. Only 34.8% of participants (95% CI: 31.3–38.4%) received adequate ANC. Key positive predictors included being married (AOR = 1.97), higher education (AOR = 1.53), higher household wealth (AOR = 1.89), awareness of ANC timing (AOR = 6.82), knowledge of pregnancy danger signs (AOR = 4.29), and understanding ANC visit frequency (AOR = 1.48). The findings reveal that only one-third of women received adequate ANC, underscoring the need for immediate interventions to improve ANC access and utilization in the Afar region to enhance maternal and child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) is the care that a woman receives during pregnancy, which helps to ensure healthy outcomes for women and newborns 1,2. It plays a crucial role in improving maternal health outcomes by providing essential preventive and promotive interventions throughout pregnancy 1. Receiving adequate ANC refers to a pregnant woman obtaining comprehensive ANC throughout her pregnancy, including frequency of visit, timing of visits, and essential content of visits. It is associated with various positive outcomes, including reduced risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, maternal infections, and death. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum of eight ANC contacts during pregnancy to address maternal and fetal health needs comprehensively with the first ANC contact taking place during the first trimester of pregnancy3.

Maternal health remains a significant challenge globally, with Ethiopia facing particularly high rates of pregnancy-related complications and mortality4,5. Inadequate ANC is associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes, including increased risks of maternal mortality, preterm birth, and low birth weight6. It contributes to maternal deaths from complications such as pre-eclampsia, and increases the likelihood of undetected infections like HIV, which can affect both mother and child. Additionally, inadequate ANC may lead to maternal nutritional deficiencies that impair fetal development7. For children, inadequate ANC is linked to higher risks of birth defects, developmental delays, and missed opportunities for critical prenatal interventions8.

In recent years, there has been a global initiative to enhance access to and utilization of ANC services, especially in low- and middle-income countries with suboptimal maternal and child health indicators 1. In Ethiopia, research indicates that no women attended eight or more ANC visits, while coverage of four or more visits ranged from 28.8 to 39.6% 9,10,11. Moreover, adherence to the recommended ANC schedule within Ethiopia is inconsistent, varying between 36.3% and 63.4% depending on the location12,13. Across different regions of Ethiopia, studies demonstrate varying degrees of adherence to recommended ANC visits. For instance, in Amhara1475.6% of women attended fewer than the recommended visits, whereas rates were much lower in other areas, such as 50.1% in Tigray1523% in Wolaita16and 44% in rural Southern Ethiopia17. According to a study conducted in the Afar region, nonadherence to recommended ANC visits was 57.0% 18.

Studies from Rwanda19India20Indonesia21and Nigeria22,23 highlight, that factors associated with the receipt of adequate ANC among women who gave birth in health facilities include women from middle to rich wealth categories, and those with health insurance are more likely to receive adequate ANC. Conversely, women with unwanted pregnancies, perceiving distance as a barrier, and receiving ANC from non-doctor healthcare providers are less likely to receive adequate care. In Ethiopia, factors contributing to inadequate ANC include rural residence, with studies showing a significant association with insufficient ANC components10,24,25. Additionally, factors like older age, higher education levels, urban residence, early initiation of ANC visits, and access to laboratory services are negatively associated with ANC dropouts, emphasizing the importance of these factors in ensuring adequate ANC utilization26,27.

Since 2022, Ethiopia has implemented the 2016 WHO model, requiring a minimum of eight ANC visits to ensure effective healthcare for pregnant women and their unborn children28,29. The FMoH prenatal care provision guideline specifies essential ANC services, including blood pressure screening, weight measurements, pallor check, fetal heartbeat, and position assessment, urine testing for infection and syphilis, blood group, hemoglobin, and rhesus factor screening. Additionally, pregnant women should receive iron/folic acid supplements, insecticide-treated bed nets, at least two doses of tetanus toxoid vaccination, deworming, nutrition counseling, and birth preparedness plans30,31.

However, there remains a significant gap in the quality of ANC service provision, with many pregnant women not receiving adequate ANC content as per national guidelines. To reduce inadequate ANC among women, training healthcare providers on ANC components is crucial24. Additionally, increasing awareness of WHO recommendations on ANC visits, especially focusing on rural women, is essential11. In Ethiopia, enhancing extensive education on ANC, especially for women reporting distance as a barrier and rural residents, is vital32. In the Afar region of Ethiopia, addressing factors like illiteracy, rural residence, substance usage during pregnancy, lack of dietary counseling, chronic medical problems, and food restrictions can help combat undernutrition among pregnant women attending ANC33.

While previous studies have explored ANC utilization rates in Ethiopia10,12,14,16,17,18,24,34,35,36,37,38there remains a dearth of comprehensive research assessing the receipt of adequate ANC and its associated factors based on a composite measure. Most existing studies focus on isolated indicators, such as the number of visits or timing alone. However, there is limited literature in Ethiopia that evaluates ANC adequacy based on a combination of critical WHO-recommended indicators, including the time of first visit, the number of visits (with a minimum of 8 contacts), and the content of ANC services received. In contrast to other communities pregnant women in pastoralist populations typically reside in scattered or difficult-to-reach locations, which can make it difficult to get to health facilities and services39. In addition, a lot of pastoralist societies travel throughout their lives in search of water and food for their livestock. Pregnant women may not always have access to healthcare services or may skip antenatal care sessions due to their mobility, which might interfere with continuity of care. Furthermore, women’s access to antenatal care services may be hampered by a lack of autonomy and decision-making authority, especially if they must obtain consent from male family members or encounter obstacles because of gender norms.

Our findings not only address this critical gap in the literature but also serve as a call to action for decision-makers, highlighting the need for context-specific interventions tailored to underserved, mobile, and rural populations. Given that public hospitals are key providers of maternal care in the region, assessing the adequacy of ANC received in these settings is crucial for improving maternal and child health outcomes. This study, therefore, seeks to address this gap by examining the factors associated with receiving adequate ANC in the Afar region, offering valuable insights for targeted interventions and policy recommendations.

Methods

Study area, design, and study period

The study was conducted in public hospitals of the Afar regional state, Northeast Ethiopia. Afar National Regional State is located in the northeastern part of Ethiopia and lies in the East African Great Rift Valley. It is bordered by the countries of Djibouti in the west and Eritrea in the north. According to the 2012 (EFY) Health and Health Related Indicators published by FMoH, Afar has 10 Hospitals, 96 Health Centers and 338 Health Posts. The tenth (10) Hospitals in the region are Abala Primary Hospital, Asaita Primary Hospital, Dalifage Primary Hospital, Kelewan Primary Hospital, Logia Health Center, Gawane Primary Hospital, Berhale Primary Hospital, Chifra Primary Hospital, Dubti General Hospital and Mohammed Aklie Memorial General Hospital40. An institutional-based cross-sectional study was carried out from May 1 to May 30, 2024.

Source and study population

The source population for this study comprised all women who received ANC during their index pregnancy and gave birth in public hospitals within the Afar Regional State, Northeast Ethiopia. The study population included all women who gave birth at the selected public hospitals during the data collection period and were able to provide the necessary information. Women were excluded if they had incomplete or missing medical records that prevented accurate assessment of their ANC attendance or if they were seriously ill during the data collection period.

Sample size determination and sampling procedures

The sample size was determined to address both objectives: assessing the magnitude of adequate antenatal care received and identifying the factors associated with it. The study utilized the maximum sample size calculated for the first objective, which was determined using the single population proportion formula. The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula with the following assumptions, drawn from a study conducted in Southern Ethiopia: 23% proportion of pregnant women who received adequate ANC utilization1695% confidence interval (CI), 4% margin of error and 10% allowance for non-response rate. Therefore, by adding a 10% non-response rate and multiplying the design effect of 1.5 becomes a final sample size of 704 women.

Where n = minimum sample size required for the study, Z = the standardized normal distribution (Z = 1.96) with a confidence interval of 95% and α = 0.05, P = the proportion of pregnant women who received adequate ANC utilization, d = degree of precision (the margin of error between the sample and population, d = 4% = 0.04).

The sample size for the second objective was calculated using a double population proportion formula by considering four variables from previous studies (Table 1).

There were ten public hospitals in the Afar region. Of the ten hospitals in the region, about 33% (Dubti General Hospital, Abala Primary Hospital, and Ayisaita Primary Hospital) were selected randomly and a proportional allocation was made for each selected hospital. The study was done in one month and the average number of deliveries per month in all selected public hospitals was 1860 (i.e. 660 women in Dubti Hospital, 630 women in Abala Primary Hospital, and 570 women in Ayisaita Primary Hospital) giving a sample of 250, 238 and 216 women, respectively. So, the systematic random sampling technique with a k value of 3 (1860/ 704) was used to get the respective respondents from each selected hospital. Particularly, the interval size (k) was calculated using the following formula.

Therefore, the interval size for each hospital was 3. So, select the first person randomly from one to three, and every third person was selected from the study population. Where N- women who gave birth at selected hospitals and n- sample size of each hospital (proportionally allocated).

Study variables and measurements

Dependent variable

The receipt of adequate ANC (categorized as Yes or No) was the dependent variable of this study.

Receipt of adequate antenatal care

It was determined using eighteen (18) components of ANC service utilization such as the total number of ANC visits (coded as none to seven, and at least eight), the timing of the first ANC visit (coded as yes or no and defined as the first ANC visit within the first three months of pregnancy), blood pressure, weighed, height, iron supplement, blood test (blood type), urine test, VDRL/syphilis test, symphonies-fundus, injection in the arm, anemia, fetal heart rate, counseled about complications/danger signs, family planning services, HIV counseling, and testing, discussed the place of delivery, and counseling about breastfeeding ever in their ANC visit. Each component has a binary response (1 = yes and 0 = no). Finally, the dependent variable was categorized as adequate if the women had received all the eighteen ANC components and codded as “1” and otherwise inadequate and coded as “0”. The definition of dependent variable is based on the WHO ANC guidelines and literature3,41,42.

Independent variables

Regarding socio-demographic factors: Women’s age in the year were grouped as 15–24, 25–34, and 35–49, no formal education, primary, secondary, and higher education were categories for the education of mothers and their husbands, current marital status categorized as married and unmarried, employment status (not employed, employed and housewife), gender of HH (female and male), mass media exposure (almost daily exposure and infrequent/not at all), involvement in decision making (not involved at all and partially involved), husband support(no/yes), and household monthly income in Birr (≤ 1000, 1001–2000, 2001–3000 and ≥ 3001). Of the obstetric characteristics: gravidity (primigravida, multigravida, grand multigravida), parity (primiparous, and multiparous), history of adverse pregnancy outcome (yes/no), pregnancy intention (unintended/intended), and birth order (1, 1–4 and ≥ 5) was included16,19,24.

Additionally, of an information related factor: awareness about pregnancy-related complications (good/poor), awareness about danger signs of pregnancy (good/poor), awareness about starting time of pregnancy(good/poor), awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visit (good/poor), perception of ANC importance (very important/ somehow important/not important), and perception towards waiting time (long, moderate and short). Health insurance (yes/no), distance to nearest health care facility (big problem and not big problem), and ANC provider (Doctor, nurse or midwife, auxiliary midwife) were considered as health system factors16,19,24.

Mass media exposure

Respondent’s exposure to television, radio, and internet43.

Pregnancy intention

Respondents were asked whether their pregnancy of last birth was planned or not; labeled as “Intended” if the pregnancy was wanted at the time, “Unintended” If the pregnancy was wanted later /not wanted at all44.

Awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visits

Respondents were asked about the minimum number of recommended ANC visits throughout the pregnancy: Good awareness if answered the question correctly (\(\:\ge\:8\))45.

Awareness about starting time of pregnancy

Respondents were asked about the recommended time to start ANC follow-up during pregnancy: Good awareness if they answered \(\:\le\:12\) weeks otherwise poor awareness45.

Awareness about danger signs of pregnancy

Respondents were asked a question consisted multiple-choice responses about danger signs of pregnancy (such as bleeding) and those correctly mentioned \(\:\ge\:5\:\)were categorized as having good knowledge about it46.

Data collection tools, procedures, and quality control

The data was coded and collected using the digital data collection tool Kobo Toolbox. A structured questionnaire was the primary tool for gathering the data. It was developed in English based on a comprehensive literature review10,47 and then meticulously translated into Amharic and Afar’af local languages. This flexibility allowed data collectors to elaborate on their experiences. A team of ten Bachelor of Science qualified midwives was responsible for data collection. Three Master of Science qualified midwives were supervising the data collection process, ensuring adherence to the protocol and data quality standards. The researcher was also available on-site to provide guidance and address any questions that may arise.

A two-day training was given for data collectors and supervisors regarding the tool and procedures. Before 2 weeks of actual data collection, a pre-test was done on 5% of the total sample in one of the non-selected hospitals. Moreover, the English version of the questionnaire was translated into Amharic and Afar’af local language and then back to English by two language experts. Supervision was conducted daily to check for data completeness.

Data processing and analysis

Data cleaning and analysis were performed using STATA software version 17. Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and percentages, were calculated to characterize the study population concerning sociodemographic and other relevant variables. A multi-collinearity test was carried out to see the correlation between independent variables using co-linearity statistics (variance inflation factor [VIF])48 and the mean of VIF was less than 5 among independent variables (see S1). Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to assess the association between received adequate ANC and the predictors identified in the literature. It has been used in the literature as a first-step method of checking associations between predictor variables and the dependent variable before further analysis in a logistic regression model 49,50,51. Predictors which were not statistically significant were eliminated and not included in the proceeding logistic regression (Fig. 1).

The goodness-of-model fitness was tested by the Hosmer–Lem shows statistic test. A binary logistic regression model was used to test the association between the outcome and the explanatory variables. In the bivariable analysis, a p-value of less than 0.2 was used as the cutoff point to include variables in the multivariable analysis. The significant association was declared at a p-value less than 0.05 in multivariable analysis. Finally, the adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI was used to determine the strength and direction of the association for the significant variables identified n the multivariable analysis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board (ERB) of Samara University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Official letters of cooperation and support were received from the Afar Regional Health Bureau and the administrations of the selected hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, with confidentiality maintained through secure record-keeping and the omission of personal identifiers. For participants under 18 years old, who may not legally provide informed consent on their own, the study protocol included a process for obtaining parental or guardian consent along with the participant’s assent, where feasible. Additionally, data extracted for the study were used solely for the research objectives, and reports did not include identifiers of specific respondents. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Socio-demographic and obstetrics characteristics of the study participants

Among the total of 704 women, 682 women participated in the study making a response rate of (97%). The median age of participants was 25 years (IQR: 22–38), indicating that the middle 50% of participants were between 22 and 38 years old. Approximately half, 344 (50.4%), were aged between 35 and 49 years. The majority, 529 (77.6%), were married, and 265 (38.9%) were uneducated. Most of the women, 383 (56.2%), were housewives. The poorest segment constituted the largest proportion of the household wealth index, 273 (40.0%), and about a quarter, 175 (25.7%), were partially involved in decision-making. Over four-fifths, 564 (82.7%), intended to get pregnant, and 286 (41.9%) had a birth order of a fifth child or higher. The majority, 569 (83.4%), were multigravida, and 533 (78.1%) were multiparous (Table 2).

Information related and health system factors

The majority, 504 (73.9%), had good awareness of pregnancy-related complications, and 448 (36.4%) perceived the distance to a health facility as a significant problem. Most women, 571 (83.7%), considered ANC (antenatal care) to be very important. The primary providers were nurses or midwives, accounting for 390 (57.2%), and 289 (42.4%) did not have health insurance (Table 3).

Receipt of adequate antenatal care (ANC)

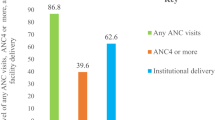

The magnitude of receipt of adequate ANC among women who gave birth at public hospitals was 34.8% (95% CI: 31.3-38.4%). Regarding individual ANC components, received iron supplement, weight, urine test, and injection in the arm were the most common items received by 91.2%, 86.8%, 83.6%, and 82.8% of respondents, respectively. The majority of participants claimed that they had counseled about HIV (78.4%), measured fatal heart rate (72.7%), counseling about pregnancy-related complications/danger-sign (71.1%), discussed place of delivery (67.3%), received family planning services (67.2%), attended ANC visit within the first three months (62.9%), and had blood pressure (61.4%). More than half of the participants reported that they had anemia test (57.8%) and blood type tests (56.2%). Less than half of the participants disclosed that they had a syphilis/VDRL test (46.5%) and symphysis-fundus measurement (43.3%). The least received ANC components as reported by the participants were height measurement (12.3%), and attended at least eight ANC visits (8.4%) (Fig. 2).

Pearson’s Chi-square test of association between received adequate ANC and predictors

Table 4 presents the results of the chi-square test used to compare differences in the receipt of adequate ANC by each factor. The adequacy of ANC received varied significantly by women’s age (X² = 9.76, df = 2, p = 0.008), marital status (X² = 7.46, df = 1, p = 0.006), education (X² = 14.71, df = 2, p = 0.001), and employment status (X² = 23.37, df = 2, p < 0.001). Additionally, it differed by the gender of the household head (X² = 28.76, df = 1, p < 0.001), mass-media exposure (X² = 23.19, df = 1, p < 0.001), and involvement in decision-making (X² = 46.88, df = 1, p < 0.001). Household wealth index (X² = 63.65, df = 2, p < 0.001), parity (X² = 11.23, df = 1, p = 0.001), and gravida (X² = 10.15, df = 1, p = 0.001) also showed significant differences. Pregnancy intention (X² = 8.87, df = 1, p = 0.003), birth order (X² = 26.23, df = 2, p < 0.001), awareness about the starting time of ANC visits (X² = 109.71, df = 1, p < 0.001), awareness about danger signs of pregnancy (X² = 42.71, df = 1, p < 0.001), and awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visits (X² = 13.06, df = 1, p < 0.001) were also significant factors. Lastly, the adequacy of ANC varied by ANC provider (X² = 6.14, df = 2, p = 0.046).

Factors associated with received adequate antenatal care (ANC)

Table 5 presents the results of bivariable analysis showing crude odds ratios (COR) and multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (AOR) between women’s characteristics and the receipt of adequate ANC. In the AOR analysis, marital status, education status, household wealth index, awareness about the starting time of ANC, awareness about danger signs of pregnancy, and awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visits were significantly associated with the receipt of adequate ANC.

Compared to unmarried women, married women were 97% more likely to receive adequate ANC (AOR = 1.97, CI = 1.11–3.49, p = 0.020). Women with secondary education or higher were also more likely to receive adequate ANC compared to uneducated women (AOR = 1.53, CI = 1.28–2.01, p = 0.049). Women from higher wealth index households had greater odds of receiving adequate ANC (AOR = 1.89, CI = 1.13–3.17, p = 0.015) compared to those from lower wealth index households. Women with good awareness of the recommended number of ANC visits were more likely to receive adequate ANC (AOR = 1.48, CI = 1.01–2.41, p = 0.049) than their counterparts. Those with good awareness of the starting time of ANC visits were 6.82 times more likely to receive adequate ANC (AOR = 6.82, CI = 4.02–11.57, p < 0.001) compared to women with poor awareness. Additionally, women with good awareness of pregnancy-related danger signs had significantly higher odds of receiving adequate ANC (AOR = 4.29, CI = 1.73–10.66, p = 0.002) compared to those with poor awareness. The Hosmer-Lem show test yielded a p-value of 0.252, indicating that the model is a good fit for the given data set (Table 5).

Discussion

Receiving adequate antenatal care(ANC) is an important indicator that has been globally reported on to assess maternal health. The current study gives a more comprehensive picture of received adequate ANC and its relations to selected factors in public hospitals of Afar regional state by indexing three indicators i.e., number of ANC visits based on the newly set WHO recommendation of a minimum of 8 contacts, time of initial visit and recommended contents of services received during the ANC visits.

This study assessed the receipt of adequate ANC and associated factors among women who gave birth in public hospitals of Afara regional state, Northeast Ethiopia. Although adequate ANC services enhance the likelihood of a positive pregnancy outcome, only 34.8% of women in this study received adequate ANC. Notably, nearly two-thirds of the women began ANC within the first three months of pregnancy, but fewer than one in ten reached the newly set WHO recommendation of a minimum of 8 contacts. Furthermore, married women, secondary and above education attendant women, women belonging to higher wealth index groups, women who had a good awareness about the starting time of ANC, had a good awareness about danger sign, and women who had a good awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visits were significant predictors of received adequate ANC among women who gave birth in public hospitals of Afar regional state, Northeast Ethiopia.

According to this study, 34.8% of women received adequate ANC, which aligns with findings from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (33%)52Northwest Ethiopia (32.7%)53and Hosanna Town’s public health facilities, Ethiopia (31.38%)54. However, this percentage is higher than in studies conducted in Bangladesh (22%)55Rwanda (27.6%)19and Southern Ethiopia (23.13%)16and significantly higher compared to Nigeria (5%)56 and slum residents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (11%)57. The disparity could be attributed to differences in measurement tools, study time and population, healthcare infrastructure, cultural practices, education, geographical accessibility, government policies, healthcare costs, community support, political stability, socioeconomic status, and the varying cutoffs used to define adequate versus inadequate ANC.

It was lower than the findings from studies conducted in Nepal (43%)58Slum Aligarh (45.1%)59and Mexico (71.4%)60. This discrepancy could be due to differences in healthcare infrastructure and accessibility, as the Afar region may have fewer healthcare facilities, a limited number of trained healthcare providers, and more challenging geographical conditions that limit access to ANC services.

According to factors associated with received adequate ANC, women’s marital status was found to have significant positive association with the received adequate ANC. Married women were more likely to receive adequate ANC than their counterparts. The finding of this study is in line with previous study in low-middle income countries61. In Afar, married women often receive stronger social support from their spouses and extended family, which is crucial in navigating the challenging healthcare landscape. This support includes financial assistance for transportation to healthcare facilities, encouragement to attend ANC visits, and help in overcoming cultural barriers that might otherwise discourage regular ANC attendance. Additionally, in a region where healthcare infrastructure is limited, the role of a supportive spouse in facilitating access to care becomes even more critical, making married women more likely to receive adequate ANC compared to their unmarried counterparts62. In low- and middle-income countries, where barriers to healthcare can be more pronounced, the support provided by a spouse can significantly enhance a woman’s ability to seek and receive adequate ANC61.

Participants’ educational level was also found to be a strong predictor of received adequate ANC. Women with secondary and above education were more likely to receive adequate ANC compared to those with no formal education. This was in line with the study conducted in Iran63 that women with higher education had increased the received adequacy of ANC. This is also consistent with the study conducted in Mexico60Bangladesh55East Africa64Sao Tome & Principe47and in Ethiopia16,54,57. This can be the fact that education empowers women with knowledge about the importance of ANC, enabling them to make informed health decisions and navigate the healthcare system more effectively65. Educated women are more likely to understand the benefits of regular ANC visits, recognize early signs of pregnancy-related complications, and adhere to recommended healthcare guidelines. Additionally, educated women often have greater financial independence and decision-making power within their households, enabling them to access healthcare services more readily. These factors contribute to a higher likelihood of receiving adequate ANC.

Moreover, women who belonged to the high wealth index group were 1.89 times more likely to receive adequate ANC than those who belonged to the low wealth index group. The finding of this study is in line with previous studies16,19,47,52,55,57,58,60,63,64which concluded that financial components seem to affect the health seeking activities of women in many ways. This finding underscore how economic stability influences access to and quality of healthcare services. Women from higher wealth index groups typically have greater access to resources and services, which enhances their likelihood of receiving adequate ANC. Wealthier households often have better access to transportation, healthcare facilities, and financial resources, which are crucial for receiving comprehensive ANC.

The current research demonstrates a significant relationship between women’s information-related factors and the likelihood of receiving adequate ANC. Specifically, women who had good awareness about the starting time of ANC visit were 6.82 times more likely to receive adequate ANC than their counterparts. Similarly, women who had good awareness about danger sign of pregnancy were 4.29 times more likely to receive adequate ANC than those who had poor awareness about danger sign of pregnancy. Furthermore, women who had good awareness about the recommended frequency of ANC visits were more likely to receive adequate ANC. These findings were confirmed by the study conducted in rural Ghana66 and in Ethiopia16,52,67,68,69which reported that women who had good awareness about information related factors were higher odds of receiving adequate ANC compared to those in their counterparts. Awareness plays a crucial role in ensuring timely and adequate ANC. Women who are knowledgeable about the optimal time to start ANC visits are more proactive in seeking care, leading to a higher likelihood of receiving adequate ANC. Similarly, understanding the danger signs of pregnancy empowers women to prioritize their health, making them more likely to obtain necessary care. Additionally, being aware of the recommended frequency of ANC visits further enhances the chances of receiving adequate care.

The primary strength of this study is its comprehensive assessment of adequate ANC using a composite index based on three key WHO-recommended indicators: the minimum of eight ANC contacts, timing of the first visit, and the content of ANC services received. This multidimensional approach offers a more accurate and holistic evaluation of ANC adequacy compared to using a single measure. Moreover, the study contributes valuable insights by focusing on the Afar Regional State, an under-researched area characterized by pastoralist and hard-to-reach communities. Nonetheless, the study has certain limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between the associated factors and ANC adequacy. Additionally, some data relied on mothers’ self-reports, which may introduce recall bias and affect the accuracy of information regarding ANC visits and services. The study was also limited to public hospitals, potentially excluding women who accessed care in private facilities or did not seek formal health services.

Ethiopia has adopted the WHO recommendation of at least eight ANC contacts and developed national maternal health strategies, including the National Nutrition Program and the Sekoto Declaration, aimed at reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality. Despite these efforts, our findings reveal significant gaps in the implementation of these policies in Afar, particularly in ensuring adequate ANC coverage and quality. Challenges such as geographical barriers, limited healthcare infrastructure, and socio-cultural factors remain significant impediments.

This study underscores the importance of strengthening local-level implementation of maternal health policies through targeted community engagement, improved health worker training, and better resource allocation to pastoral and remote areas. Policy makers should prioritize awareness campaigns to improve maternal knowledge on ANC timing and content and develop supportive mechanisms to address economic and social barriers that limit ANC uptake. Enhancing the quality and comprehensiveness of ANC services in public hospitals is essential to achieving Ethiopia’s 2030 goals for maternal and child health.

Conclusions

While adequate ANC is crucial for optimal pregnancy outcomes, our study reveals that only approximately one-third of women had received adequate ANC in public hospitals of Afar regional sate, Ethiopia. Marital status, education status, household wealth index, awareness about the starting time of ANC, awareness about danger signs of pregnancy, and awareness about the frequency of recommended ANC visits were significantly associated with received adequate ANC. The findings of this study suggest that public hospitals in the region should prioritize improving ANC provision by targeting identified at-risk groups, including unmarried women, those with no formal education, economically disadvantaged women, and those lacking awareness about key ANC information. Addressing these factors through targeted interventions and enhanced education can help bridge the gap in ANC uptake and ultimately contribute to better maternal and neonatal health outcomes in the region. Additionally, strengthening healthcare providers’ adherence to ANC guidelines and enhancing the quality of ANC services in public hospitals is essential. This can be achieved through regular monitoring mechanisms to ensure compliance with WHO recommendations for adequate ANC.

Data availability

All data and materials related to this study are accessible. The datasets utilized or analyzed during the study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Central Statistical Agency

- ETB:

-

Ethiopian Birr

- HSDP IV:

-

Health Sector Development Program IV

- LMICs:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MDHS:

-

Mini Demographic and Health Survey

- mHealth:

-

Mobile Health

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TBAs:

-

Traditional Birth Attendants

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Organization, W. H. WHO antenatal care recommendations for a positive pregnancy experience: nutritional interventions update: multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy. (2020).

Unicef. (2023).

Organization, W. H. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: summary: highlights and key messages from the World Health Organization’s 2016 global recommendations for routine antenatal care (World Health Organization, 2018).

Kotch, J. Maternal and Child Health: Programs, Problems, and Policy in Public Health (Jones & Bartlett, 2013).

Lu, M. C. The future of maternal and child health. Matern. Child Health J. 23, 1–7 (2019).

Girotra, S., Malik, M., Roy, S. & Basu, S. Utilization and determinants of adequate quality antenatal care services in india: evidence from the National family health survey (NFHS-5)(2019-21). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23, 800 (2023).

Wu, H. The effect of maternal education on child mortality in Bangladesh. Popul. Dev. Rev. 48, 475–503 (2022).

Kassaye, Z. & Tebeje, B. Ethiopia pubilic health training initiative, (2005).

Pons-Duran, C. et al. Antenatal care coverage in a low-resource setting: estimations from the Birhan cohort. PLOS Global Public. Health. 3, e0001912 (2023).

Yehualashet, D. E., Seboka, B. T., Tesfa, G. A., Mamo, T. T. & Seid, E. Determinants of optimal antenatal care visit among pregnant women in ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of Ethiopian mini demographic health survey 2019 data. Reproductive Health. 19, 61 (2022).

Negash, W. D. et al. Magnitude of optimal access to ANC and its predictors in ethiopia: multilevel mixed effect analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 18, e0284890 (2023).

Tekelab, T., Chojenta, C., Smith, R. & Loxton, D. Factors affecting utilization of antenatal care in ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 14, e0214848 (2019).

Institute, E. P. H. (EPHI/FMoH/ICF Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (2021).

Getachew, T., Abajobir, A. & Aychiluhim, M. Focused antenatal care service utilization and associated factors in Dejen and aneded districts, Northwest Ethiopia. Prim. Health Care. 4, 2167–1079 (2014).

Haftu, A., Hagos, H., Mehari, M. A. & G/her, B. Pregnant women adherence level to antenatal care visit and its effect on perinatal outcome among mothers in Tigray public health institutions, 2017: cohort study. BMC Res. Notes. 11, 1–6 (2018).

Gebrekirstos, L. G., Wube, T. B., Gebremedhin, M. H. & Lake, E. A. Magnitude and determinants of adequate antenatal care service utilization among mothers in Southern Ethiopia. Plos One. 16, e0251477 (2021).

Belay, A., Astatkie, T., Abebaw, S., Gebreamanule, B. & Enbeyle, W. Prevalence and factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in rural areas of Southwestern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 22, 30 (2022).

Urmale Mare, K. et al. Factors affecting nonadherence to who’s recommended antenatal care visits among women in pastoral community, Northeastern ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Nursing Res. Practice 2022 (2022).

Tengera, O. et al. Factors associated with receipt of adequate antenatal care among women in rwanda: A secondary analysis of the 2019–20 Rwanda demographic and health survey. Plos One. 18, e0284718 (2023).

Thakkar, N., Alam, P. & Saxena, D. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care in india: results from 2019–2021 National family health survey. Plos One. 18, e0285454 (2023).

Sari, D. P. et al. Antenatal care utilization on low birth weight children among women with high-risk births. F1000Research 12 (2023).

Envuladu, E. A., Issaka, A. I., Dhami, M. V., Sahiledengle, B. & Agho, K. E. Differential associated factors for inadequate receipt of components and non-use of antenatal care services among adolescent, young, and older women in Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20, 4092 (2023).

Ilesanmi, B. B. et al. To what extent is antenatal care in public health facilities associated with delivery in public health facilities? Findings from a cross-section of women who had facility deliveries in Nigeria. BMC Public. Health. 23, 820 (2023).

Gelagay, A. A. et al. Inadequate receipt of ANC components and associated factors among pregnant women in Northwest ethiopia, 2020–2021: a community-based cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health. 20, 69 (2023).

Mengist, B., Endalew, B., Diress, G. & Abajobir, A. Late antenatal care utilization in ethiopia: the effect of socio-economic inequities and regional disparities. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2, e0000584 (2022).

Tariku, M., Tusa, B. S., Weldesenbet, A. B., Bahiru, N. & Enyew, D. B. More than one-third of pregnant women in Ethiopia had dropped out from their ANC follow-up: evidence from the 2019 Ethiopia Mini demographic and health survey. Front. Global Women’s Health. 3, 893322 (2022).

Woldeamanuel, B. T. & Belachew, T. A. Timing of first antenatal care visits and number of items of antenatal care contents received and associated factors in ethiopia: multilevel mixed effects analysis. Reproductive Health. 18, 1–16 (2021).

Organization, W. H. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: screening, diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis disease in pregnant women. Evidence-to-action brief: Highlights and key messages from the World Health Organization’s global recommendations. (World Health Organization, 2023). (World Health Organization, 2023). (2016).

Fmoh, E. (February, (2022).

Assegid, M. et al. Providing focused antenatal care. Antenatal Care Module 13 (2017).

Shiferaw, K., Mengistie, B., Gobena, T., Dheresa, M. & Seme, A. Extent of received antenatal care components in ethiopia: a community-based panel study. International J. women’s health, 803–813 (2021).

Mruts, K. B. et al. Achieving reductions in the unmet need for contraception with postpartum family planning counselling in ethiopia, 2019–2020: a National longitudinal study. Archives Public. Health. 81, 79 (2023).

Birara Aychiluhm, S., Gualu, A. & Wuneh, A. G. Undernutrition and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in pastoral communities of Afar regional state, Northeast Ethiopia. Pastoralism 12, 35 (2022).

Abebe, E., Seid, A., Gedefaw, G., Haile, Z. T. & Ice, G. Association between antenatal care follow-up and institutional delivery service utilization: analysis of 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Public. Health. 19, 1–6 (2019).

Negero, M. G., Sibbritt, D. & Dawson, A. Women’s utilisation of quality antenatal care, intrapartum care and postnatal care services in ethiopia: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Public. Health. 23, 1174 (2023).

Tsegaye, B. & Ayalew, M. Prevalence and factors associated with antenatal care utilization in ethiopia: an evidence from demographic health survey 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20, 1–9 (2020).

Abebe, G. F. et al. Determinants of early initiation of first antenatal care visit in Ethiopia based on the 2019 Ethiopia mini-demographic and health survey: A multilevel analysis. PLoS One. 18, e0281038 (2023).

Tegegne, T. K., Chojenta, C., Getachew, T., Smith, R. & Loxton, D. Antenatal care use in ethiopia: a Spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 19, 1–16 (2019).

Eba, K. et al. Mobile health service as an alternative modality for hard-to-reach pastoralist communities of Afar and Somali regions in Ethiopia. Pastoralism 13, 17 (2023).

Statistical, C. Population and housing census of Ethiopia. Administrative Report. Central Statistical Authority Addis Ababa.( Available online at: (2012). https://rise.esmap.org/data/files/library/ethiopia/Documents/Clean%20Cooking/Ethiopia_Census 202007 (2007).

Negash, W. D. et al. Multilevel analysis of quality of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 12, e063426 (2022).

Arsenault, C. et al. Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 National household surveys. Lancet Global Health. 6, e1186–e1195 (2018).

Vahabi, M. The impact of health communication on health-related decision making: A review of evidence. Health Educ. 107, 27–41 (2007).

Santelli, J. S., Lindberg, L. D., Orr, M. G., Finer, L. B. & Speizer, I. Toward a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: evidence from the united States. Stud. Fam. Plann. 40, 87–100 (2009).

Organization, W. H. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience (World Health Organization, 2016).

Organization, W. H. State of Inequality: Reproductive Maternal Newborn and Child Health: Interactive Visualization of Health Data (World Health Organization, 2015).

Vasconcelos, A. et al. Determinants of antenatal care utilization–contacts and screenings–in Sao Tome & principe: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Archives Public. Health. 81, 107 (2023).

Midi, H., Sarkar, S. K. & Rana, S. Collinearity diagnostics of binary logistic regression model. J. Interdisciplinary Math. 13, 253–267 (2010).

Antwi, E. et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for gestational hypertension in a Ghanaian cohort. BMJ Open. 7, e012670 (2017).

Chen, C. & Zhang, J. Exploring background risk factors for fatigue crashes involving truck drivers on regional roadway networks: a case control study in Jiangxi and shaanxi, China. SpringerPlus 5, 1–12 (2016).

Gross, S. M., Biehl, E., Marshall, B., Paige, D. M. & Mmari, K. Role of the elementary school cafeteria environment in fruit, vegetable, and whole-grain consumption by 6-to 8-year-old students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 51, 41–47 (2019).

Hailu, G. A., Weret, Z. S., Adasho, Z. A. & Eshete, B. M. Quality of antenatal care and associated factors in public health centers in addis ababa, ethiopia, a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 17, e0269710 (2022).

Kassaw, A., Debie, A. & Geberu, D. M. Quality of prenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women at public health facilities of Wogera District, Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of pregnancy 9592124 (2020). (2020).

Tadesse Berehe, T. & Modibia, L. M. Assessment of quality of antenatal care services and its determinant factors in public health facilities of Hossana Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. Advances in Public Health 5436324 (2020). (2020).

Islam, M. M. & Masud, M. S. Determinants of frequency and contents of antenatal care visits in bangladesh: assessing the extent of compliance with the WHO recommendations. PloS One. 13, e0204752 (2018).

Fagbamigbe, A. F. & Idemudia, E. S. Assessment of quality of antenatal care services in nigeria: evidence from a population-based survey. Reproductive Health. 12, 1–9 (2015).

Bayou, Y. T., Mashalla, Y. S. & Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G. The adequacy of antenatal care services among slum residents in addis ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 16, 1–10 (2016).

Bastola, P., Yadav, D. K. & Gautam, H. Quality of antenatal care services in selected health facilities of Kaski district, Nepal. Int. J. Community Med. Public. Health. 5, 2182–2189 (2018).

Mehnaz, S., Abedi, A., Fazli, S., Ansari, M. & Ansari, A. Quality of care: predictor for utilization of ANC services in slums of Aligarh. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public. Health. 5, 1869–1873 (2016).

Heredia-Pi, I., Servan-Mori, E., Darney, B. G., Reyes-Morales, H. & Lozano, R. Measuring the adequacy of antenatal health care: a National cross-sectional study in Mexico. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 452 (2016).

Chilot, D. et al. Pooled prevalence and determinants of antenatal care visits in countries with high maternal mortality: A multi-country analysis. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1035759 (2023).

Hailegebreal, S., Gilano, G., Seboka, B. T., Ahmed, M. H. & Simegn, A. E. Spatial distribution and associated factors of antenatal care utilization in Ethiopia in 2019: Spatial and multilevel analysis. (2021).

Dadras, O. et al. Barriers and associated factors for adequate antenatal care among Afghan women in iran; findings from a community-based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Raru, T. B. et al. Quality of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa using demographic and health surveys: A multilevel analysis. Women’s Health. 18, 17455065221076731 (2022).

Islam, M. M. & Masud, M. S. Health care seeking behaviour during pregnancy, delivery and the postnatal period in bangladesh: assessing the compliance with WHO recommendations. Midwifery 63, 8–16 (2018).

Afaya, A. et al. Women’s knowledge and its associated factors regarding optimum utilisation of antenatal care in rural ghana: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. 15, e0234575 (2020).

Mebratie, A. D. Receipt of core antenatal care components and associated factors in ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. Front. Global Women’s Health. 5, 1169347 (2024).

Kebede, A. A., Taye, B. T. & Wondie, K. Y. Factors associated with comprehensive knowledge of antenatal care and attitude towards its uptake among women delivered at home in rural Sehala Seyemit district, Northern ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Plos One. 17, e0276125 (2022).

Deresa Dinagde, D., Feyisa, G. T., Afework, H. T., Chewaka, M. T. & Wada, H. W. Level of optimal antenatal care utilization and its associated factors among pregnant women in Arba minch town, Southern ethiopia: new WHO-recommended ANC 8 + model. Front. Global Women’s Health. 5, 1259637 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Samara University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences for its ethical review process. Authors also thank study participants, supervisors, data collectors and all staff members of the Afar Regional Health Office for their contributions throughout this work.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Kusse Urmale MareData curation: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Kusse Urmale MareFormal analysis: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Kusse Urmale Mare Investigation: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seif, Bizunesh Fantahun Kase, Kusse Urmale MareMethodology: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seif, Bizunesh Fantahun Kase, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, Kusse Urmale MareSoftware: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Kusse Urmale MareValidation: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Bizunesh Fantahun Kase, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, Kusse Urmale Mare Visualization: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Bizunesh Fantahun Kase, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, Kusse Urmale MareWriting – original draft: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Kusse Urmale MareWriting – review & editing: Abdu Hailu Shibeshi, Beminate Lemma Seifu, Bizunesh Fantahun Kase, Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, Kusse Urmale Mare.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shibeshi, A.H., Seifu, B.L., Kase, B.F. et al. Receipt of adequate antenatal care and associated factors among women delivering in public hospitals, Afar region, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 29197 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10535-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10535-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring satisfaction on ANC digital health among pregnant women: a qualitative study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2025)