Abstract

This study aims to compare the applied efficacy of barbed suture versus non-barbed suture, as well as various stitching techniques, for laparoscopic cholecystoduodenostomy (LCD) in rabbits (imitating infants) to determine the most viable suture option. LCD was performed in a total of 45 male New Zealand white rabbits. The rabbits were equally divided into three groups: the SFB group (single-layer full-thickness running suture using barbed sutures), the SSB group (simple seromuscular layer running suture using barbed sutures) and the PDS group (single-layer full-thickness running suture using PDS sutures). The incidence of anastomotic complications, and histopathological outcomes were evaluated and compared across the groups. The mean duration for LCD was 9.6 ± 1.2 min in the SFB group and 10.8 ± 1.5 min in SSB group, both significantly shorter than the 12.0 ± 0.9 min observed in the PDS group (P < 0.001). Three cases of bile leakage were found in SFB group. H&E staining clearly revealed two cases of ectopic mucosal tissues at the anastomotic muscular layer in the SFB group. The collagen fibers, transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-β1), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) of anastomotic tissues at all examined time points post-surgery were generally higher in SFB group than in the other two groups, with some statistically significant differences. No significant differences were observed between the SSB group and PDS group. The findings demonstrate that for barbed sutures, full-thickness technique was inferior to PDS sutures due to a higher bile leakage rate, whereas the seromuscular technique achieved difficult to hepatic duct. As a result, barbed sutures are not recommended for use in infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital choledochal cyst (CCC) is a common and priority disease in pediatric surgery1. While CCC is extremely rare in Western populations (1 in 100,000–150,000)2, the incidence is generally higher across Asian populations, with certain regions reporting rates as elevated as 1 in 10003. This biliary malformation, caused by multiple factors, is primarily treated through complete excision of the cyst and reconstruction of the biliary tract which is considered the gold standard for CCC4. Currently, laparoscopic cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy is the recommended surgical approach5. However, as the most critical and challenging component of the procedure, the laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy is technically demanding6. Anastomosis-related complications such as bile leakage, anastomotic stenosis are the most common postoperative complications and can lead to severe consequences. Despite numerous efforts to enhance the safety of hepaticojejunostomy and streamline the anastomosis procedure, the use of mechanical staplers remains challenging. Consequently, manual anastomosis continues to be regarded as the most reliable suture technique. Currently, absorbable monofilament sutures such as polydioxanone suture are commonly used in biliary duct reconstruction. In recent years, the introduction of knotless absorbable barbed suture in laparoscopy has significantly reduced the complexity of intracorporeal suturing and knot tying7 as well as decreased the suture time8. Subsequently, barbed suture has demonstrated successful application in various pediatric surgical procedures, including laparoscopic pyeloplasty9 and thoracoscopic/laparoscopic diaphragmatic reconstruction10. However, the application in pediatric hepaticojejunostomy remains controversial. Strictly speaking, there is limited literature on the use of barbed sutures in hepaticojejunostomy. While generally considered safe for application in adults with relatively large bile duct diameter and thick bile duct wall, barbed suture may increase the risk of postoperative bile leakage in children11. This view reflects clinical intuition rather than conclusive evidence. Therefore, we designed a rabbit cholecystoduodenostomy model to validate our hypothesis regarding the increased risk of bile leakage in infants. To address this issue, we proposed a suture method that can effectively reduce the probability of bile leakage. Our goal is to provide experimental basis for selecting appropriate suture techniques in laparoscopic procedures.

Methods

A total of 45 healthy male adult New Zealand white rabbits (purchased from Tong Hui Co. Ltd., Baoding, China), each weighing between 3.0 and 3.2 kg, were used in this study. Sample size calculations adhered to the 3R principles. Based on the pilot data (barbed suture group bile leakage rate: 40% vs. PDS group: 0%), we performed a power analysis using freeware G*Power 3.1 (version 3.1.9.7). With an α level of 0.05 and 80% power, the calculation indicated that a minimum of 15 rabbits per group would be required. The rabbits were housed under controlled conditions (12-h light–dark cycle, room temperature 18–20 °C, relative humidity 50–60%) with free access to pelleted diet and water. They were kept in individual cages at least one week prior to surgery, and then underwent LCD. The two types of sutures used were barbed suture (Stratafix Spiral PGA-PCL Knotless Tissue Control Device, Ethicon, Inc.) and non-barbed suture (PDS II, Ethicon, Inc.). All the anastomoses were performed by the same team of surgeons to ensure consistency. Before randomization, each rabbit received a unique alphanumeric code (R01–R45). Randomization was performed using a permuted block design (block size = 6) via the Fisher-Yates random number table, implemented by a blinded researcher using SPSS v16.0. The allocation sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned. Then the rabbits were divided into three groups (15 rabbits in each group), and different suture materials and methods were used in LCD: the SFB group (single-layer full-thickness running suture using barbed sutures), the SSB group (simple seromuscular layer running suture using barbed sutures) and the PDS group (single-layer full-thickness running suture using PDS sutures). No stratification factors were applied as all rabbits shared identical baseline characteristics (weight, sex, breed).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No.2023-AE111). We confirmed that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines12 (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Establishment of animal model

All rabbits were fasted overnight before surgery but had free access to water. Anesthesia was induced by intravenous injection of 20% urethane (1 g/Kg). The rabbit was placed in a supine position, and laparoscopic entry was established using four-trocar technique. A 1 cm longitudinal incision was made in the gallbladder fundus using scissors, and the bile was evacuated. An adjacent section of the duodenal wall, below the gallbladder, was then opened to match the size of the gallbladder incision. The three groups of rabbits underwent LCD respectively as follows:

-

1.

Single-layer full-thickness running suture (SFB group and PDS group): Anastomosis was performed using 4–0 absorbable barbed suture or 4–0 polydioxanone suture. The running suture began on the left side of the intestinal incision, with the needle entering from the serosa and exiting from the mucosa. Subsequently, the needle was then inserted into the left side of the gallbladder incision, entering from the inner wall and exiting from the outer wall. The ends of the suture was knotted outside the anastomosis to secure it in place. Then the single-layer full-thickness running suturing was performed on the posterior wall from left to right. Upon completion of the posterior wall, the suture continued on the anterior wall, progressing from right to left. In PDS group, the two suture ends were knotted together upon completion, whereas in SFB group, an additional bite was taken to overlap the beginning of the suture line once the anastomosis was completed.

-

2.

Simple seromuscular layer running suture (SSB group): The needle was inserted into the intestinal serosa, passed obliquely through the seromuscular layer, and exited from the submucosa, then inserted below the submucosal layer of the gallbladder and exited from the serosa. The remaining procedure was identical to that described for the SFB group, with the anastomosis completed using one additional bite instead of a knot.

After surgery, each rabbit was returned to its own cage and maintained under the same breeding conditions as before. Due to the inherently visible differences between the compared suture techniques, complete blinding of the operating surgeons was not feasible. We minimized potential bias through two measures: first, all preoperative preparations (anesthesia, skin disinfection) followed identical protocols regardless of group assignment; second, postoperative care providers remained fully blinded to group allocations.

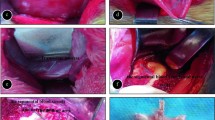

Histopathological staining

The endpoints were prespecified at postoperative days 3, 7, and 14. For each group, 15 rabbits were randomly allocated to these timepoints (5 per day) followed the aforementioned random number table algorithm to ensure unbiased distribution. The rabbits were euthanized in batches according to the subgroup assignment with an overdose of the intravenous anesthetic urethane. The anastomotic tissue specimens were collected to observe the histological changes (Fig. 1). Following collection, all specimens were assigned random identification numbers (S01–S45) to maintain blinding. The specimens were formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. They were cut into 4 μm slices and processed with Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson trichrome and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. Pathologists remained fully blinded to group allocations throughout the entire analytical process, from initial specimen examination to final scoring.

Observed Index

-

a.

Perioperative data: time for LCD, anastomotic complications.

-

b.

Daily observation about the general condition of experimental rabbits, and necropsy of the deceased rabbits to determine the cause of death. The dead animals were excluded from the Masson and immunohistochemistry staining.

-

c.

Histopathological analysis of the anastomotic tissue: H&E staining was used to observe the general tissue structure of the anastomosis. The collagen content was determined by Masson trichrome staining and calculated as collagen volume fraction (CVF). The expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA and IL-6 were measured by the immunohistochemical method and calculated as average optical density (OD). For quantitative analysis, five random images at 40 × magnification were captured for each stained area and the average values were calculated. Image analysis software Fiji (ImageJ 2.14.0) was used to quantify the Masson and immunohistochemistry staining in anastomotic tissues.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS statistical software (SPSS for Windows, version 16.0). Measurement data were presented as mean ± standard deviation as they followed a normal distribution. After passing the homogeneity of variance test, the Students–Newman–Keuls test was used for multiple comparison between groups. Categorical variables were recorded digitally and analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

-

1.

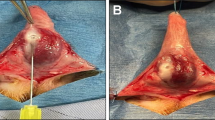

The operative outcomes of SFB, SSB and PDS groups

A total of 45 rabbits underwent LCD (Fig. 2). The mean anastomosis time for the SFB group was 9.6 ± 1.2 min, while for the SSB group it was 10.8 ± 1.5 min. Both of them were significantly shorter than the PDS group, which had a mean anastomosis time of 12.0 ± 0.9 min (P < 0.001). Regardless of the stitching method employed, barbed sutures consistently reduced operative time compared to PDS sutures. No statistically significant difference was observed between SFB group and SSB group (P = 0.073). Postoperative bile leakage occurred in 3 cases, all within the SFB group. One rabbit was diagnosed with anastomotic bile leakage on postoperative day3 during sampling of the anastomotic specimen. The other two rabbits died on the 4th day (day7 subgroup) and the 6th day (day14 subgroup), respectively. The cause of death was confirmed to be bile leakage followed by infection. No unexpected deaths or surgery-related complications were observed in SSB group and PDS group. Although the intergroup difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.096), the SSB and PDS groups demonstrated a clear clinical advantage with 0% bile leakage rates (0/15 each), contrasting sharply with the 20% rate (3/15) in the SFB group. (Table 1).

-

2.

The demonstration of ectopic mucosal tissues

H&E staining demonstrated the presence of ectopic mucosal tissues at the anastomosis in two cases within the SFB group (day3 and day7 subgroups, respectively). No such finding was observed in SSB or PDS groups (Fig. 3).

-

3.

The collagen fibers of SFB, SSB and PDS groups

Masson’s trichrome staining (Fig. 4) revealed that on the 3rd day after surgery, the collagen fibers in each group were thin, and no thick collagen fibers were formed. By the 7th day post-surgery, newly born collagen fibers were more abundant and disorderly arranged. On the 14th day, the collagen fibers showed increased proliferation and denser arrangement. There was no significant statistic difference in collagen content among the three groups (Table 2). However, a trend was observed in the SFB group, which consistently demonstrated higher collagen content compared to the other groups across all time points. This observation suggests a potentially more pronounced tissue reaction in the SFB group.

Masson’s trichrome staining sections of anastomotic tissue on the day3, day7 and day14 after surgery in the three groups (40 ×). Collagen fiber density progressively increased postoperatively in all groups, evolving from thin fibers (day 3) to disorganized proliferation (day 7) and dense arrangement (day 14). No significant intergroup differences in collagen content were found, though the SFB group showed a consistent trend toward higher values at all time points.

-

4.

Immunohistochemistry of SFB, SSB and PDS groups

Immunohistochemistry revealed that the expression of TGF-β1(Fig. 5) in SFB was higher than in SSB and PDS groups. A statistically significant difference was observed between the SFB and SSB groups on the 7th day post-surgery (P < 0.05). No significant difference was detected between the SSB and PDS groups (Table 2). Similarly, the expression of α-SMA (Fig. 6) was also consistently higher in the SFB group compared to the other two groups, with statistically significant differences at the 7th and 14th days post-surgery (Table 2). To further assess the inflammatory response associated with different sutures and suture methods, we compared the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in three groups (Fig. 7). The IL-6 levels in the SFB group were higher than those in the SSB and PDS groups at all three post-surgery time points, with all differences being statistically significant (Table 2). In summary, the expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA and IL-6 in SFB group were consistently higher than those in the SSB and PDS groups at all evaluated time points, with several statistically significant differences noted. No significant difference was observed between SSB group and PDS group. The proliferation of collagen fibers followed a similar trend to these findings (Fig. 8).

The expression of IL-6 on the day3, day7 and day14 after surgery in the three groups (IHC × 40). All groups exhibited rapid upregulation followed by downregulation postoperatively. SFB group showed significantly stronger immunostaining intensity than SSB/PDS group at all time points (*p < 0.05). No intergroup difference was observed between SSB and PDS groups.

Comparison of collagen content (CVF) and the expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA and IL-6(OD) among three groups at all time points. All parameters were quantitatively analyzed. SFB group exhibited consistently higher levels than SSB/PDS group (*p < 0.05 at indicated time points), while SSB and PDS groups showed comparable expression. Trends were largely consistent across all markers.

Discussion

Bile leakage is one of the most common short-term complications following laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy (LHJ), and is a primary cause of unplanned reoperation after CCC surgery in children13. Various factors contribute to postoperative anastomotic leakage, including perioperative systemic conditions of children, management of biliary infection, and technical aspects of the anastomosis14. Among these, the selection of anastomosis methods and materials is a critical factor directly related to the surgeon, offering potential for ongoing improvement. Stitching is widely acknowledged as one of the most challenging and time-consuming tasks in laparoscopy, partly due to the necessity of knot-tying within a confined space and limited range of motion. This challenge is even greater for pediatric surgeons operating on infants. A single knot failure can compromise the entire procedure15. Studies indicate that approximately 50% of laparoscopic suture failures are attributable to the slipping or unraveling of the knots16. Despite extensive training and simulation efforts, laparoscopic stitch remains difficult to master. In response, some surgeons have started utilizing barbed sutures, which feature self-anchoring, covered with barbs that prevent retraction once embedded in the tissue. This type of suture allows the incision to seal progressively during suturing, eliminating the need for repeated adjustment to suture tightness and the need to tie knots upon completion. The technique is theoretically easier and faster, and if proven safe for LHJ, it could reduce the difficulty of operation and make the surgery more accessible to a broader range of surgeons.

To simulate LHJ procedure in infant, LCD rabbit model using both barbed and non-barbed sutures was designed17. The results demonstrated that 3 cases with bile leakage were found in SFB group, with no other complications recorded. A noteworthy finding is that warrants discussion pertains to the safety of barbed suture, particularly the risk of anastomotic leakage in hollow organs. Some researchers speculated that the sharp barb may cut through the tissue18 or injury the seromuscular19, potentially causing anastomotic rupture. However, in applications within arthroplasty20, gynecological21 and plastic surgery22, where sutured tissues such as fascia, cartilage and tendon, lack exocrine function, barbed suture have demonstrated stable efficacy with few reports of increased wound dehiscence or infection. We selected TGF-β1, α-SMA, and IL-6 as biomarkers of inflammatory responses and tissue injury. TGF-β1, an early-phase multifunctional cytokine secreted by immune cells and fibroblasts, promotes monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, amplifying inflammatory responses23,24. It induces α-SMA expression, a key mediator of tissue repair and fibrosis25. IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine, serves as a rapid-response inflammatory mediator following tissue damage26. Pathological analysis of all rabbit anastomotic tissue samples found that there was a stronger inflammatory response of the anastomotic tissue in the SFB group compared to the other two groups at all post-surgical time points. Given that all groups received identical surgical conditions and postoperative care, and no systemic infections were observed in any case, this ruled out confounding by unrelated inflammatory stimuli. The localized inflammation surrounding the barbed suture was significantly greater than that around non-barbed sutures, consistent with current mainstream research27. More importantly, we identified ectopic mucosal tissue within the anastomosis in two specimens from full-layer anastomosis with barbed sutures group, which was not observed in the corresponding PDS group with smooth surface sutures. Based on these observations, we propose a potential mechanism to explain this phenomenon that during the suture process, the barbs passing through the tissue might abrade the edematous and fragile mucosal tissues, displacing them into the anastomotic seromuscular layer or outside the anastomosis. The ectopic mucosal cells could continue to secrete digestive juice, potentially exacerbating local inflammation, leading to poor anastomotic healing, or even abscess formation. While it is true that barbed suture may create larger hole compared to monofilament suture, our clinical observations suggest this factor alone may not fully explain the severe leakage cases we encountered. In practice, minor bile leaks resulting from needle perforations typically resolve with conservative management. However, in our experience with more severe cases requiring reoperation, we observed complete anastomotic dehiscence rather than simple suture tract leakage, implying the involvement of additional pathological mechanisms.

In view of this possibility, we modified the technique from a single-layer full-thickness running suture to a simple seromuscular layer running suture when using barbed sutures. This modification, implemented in the SSB group, aimed to minimize the risk of mucosal tissue abrasion by the barbs scraping. All the procedures in the SSB group were successful, with no cases of bile leakage post-surgery. The anastomosis time was comparable to that of SFB group, and also significantly shorter than that of PDS group. No ectopic mucosal tissue of anastomosis was found in pathological specimens, and the tissue inflammatory response was reduced compared to full-layer anastomosis. This reduction in inflammation could create a better local microenvironment conducive to tissue repair and regeneration28. These finding confirm that the method of simple seromuscular anastomosis using barbed suture is both feasible and effective, significantly improving the safety of barbed sutures. Meanwhile, the simple seromuscular anastomosis technique, where the needle emerges from the submucosa, preserves the submucosa blood supply, thus ensuring adequate oxygen supply for collagen synthesis. Theoretically, this technique may promote faster anastomosis healing and inhibit scar tissue hyperplasia. Besides, maintaining mucosal integrity can prevent leakage even when suture channel leakage risks exist.

However, it is important to note that performing laparoscopic seromuscular anastomosis has higher technical demands compared to full-layer anastomosis. Based on our clinical experience, the main technical point help achieve reliable suturing is on the needle’s pathway through the tissue. After the needle tip vertically penetrates the serosal layer, it passes obliquely through the seromuscular layer and then emerges from the submucosa, rather than penetrating vertically through the entire muscular layer and then tunneling horizontally within the submucosa. This approach appears to facilitate the suturing procedure and reduces the likelihood of mucosal entrapment. We strongly recommend two key strategies to achieve the target surgical proficiency: (1) initial training using ex vivo animal tissue models, and (2) proctorship by experienced surgeons during initial clinical cases.

Furthermore, reports have indicated that bile leakage in the bilioenteric anastomosis sutured with barbed suture tends to occur at both corners of the anastomosis. Some surgeons have considered that the absence of a barbed surface on the extremities of the suture results in loosening of the initial stitch. They have suggested that the leaks could be avoided by capturing a larger amount of tissue in the first needle passages29. However, in the context of rabbit cholecystoduodenostomy, the wall of the gallbladder and duodenal is thin, and there is no excess surrounding tissue. Our approach involves tying a knot outside the incision with moderate tension at the start of the suturing process. This tension need not be excessive, as it will still achieves a good sealing effect, and no anastomotic stenosis or abdominal adhesions related to this procedure have been observed in our study groups.

Regrettably, in pediatric LHJ—particularly in infants—the hepatic ducts are exceptionally thin and fragile, unlike the tear-resistant gallbladder walls of rabbits. This makes precise seromuscular suturing technically unachievable in clinical practice. Thus, barbed sutures should be strictly avoided in these cases. For older children, however, the hepatoduodenal ligament and bile duct tissues demonstrate sufficient thickness and mechanical resilience, well-developed intestinal walls. This anatomical advantage may warrant further investigation into the potential applicability of barbed sutures in these populations. This may require further exploration using large animal models, such as canine or porcine subjects. Nevertheless, our study proposes a novel problem-solving paradigm. Beyond biliary surgery, this technique may generalize to other scenarios requiring precise mucosal apposition, such as gastrointestinal or urinary tract reconstructions, especially in narrow surgical fields.

Our study has several additional limitations. Firstly, surgeon blinding was impractical, but other steps were standardized, and postoperative observers were blinded to minimize bias. Secondly, the controlled conditions of our healthy animal model enabled precise evaluation of surgical technique effects, though we acknowledge the need for validation in more clinically diverse populations. Future studies will therefore focus on validating these results in both diseased animal models and heterogeneous populations to further assess translational potential. Thirdly, this study primarily focused on early complications (particularly bile leakage) within the 14-day postoperative period. While our preliminary findings showed no significant tendency toward anastomotic stenosis (as evidenced by absence of abnormally high fibrosis or progressive inflammatory response), this observation period was too short to properly evaluate this common long-term complication. Further studies with extended follow-up are needed to assess potential stenosis risks associated with different suturing techniques. Finally, while this study primarily focused on evaluating the feasibility of barbed sutures and comparing different suturing techniques (using PDS suture as the control group), we did not investigate the potential impact of different suturing methods when using PDS sutures. This represents an important area for future research.

Conclusion

This study identified that during the suturing process with barbed sutures, the ectopic mucosa in rabbit anastomosis may be scraped off by the barbs, potentially increasing the probability of anastomosis leakage. However, the risk can be effectively mitigated by employing a simple seromuscular anastomosis, which proves to be both safe and reproducible. The findings provide a practical reference for suture and technique selection in laparoscopy, though barbed sutures are not recommended for infant hepaticojejunostomy due to hepatic duct without seromuscular layer.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cazares, J., Koga, H. & Yamataka, A. Choledochal cyst. Pediatric Surg. Int. 39(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-023-05483-1 (2023).

Baison, G. N., Bonds, M. M., Helton, W. S. & Kozarek, R. A. Choledochal cysts: Similarities and differences between Asian and Western countries. World J. Gastroenterol. 25(26), 3334–3343. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i26.3334 (2019).

Miyano, T. & Yamataka, A. Choledochal cysts. Curr. Opin. Pediatrics 9(3), 283–288. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008480-199706000-00018 (1997).

Liem, N. T. Laparoscopic surgery for choledochal cysts. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sci. 20(5), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-013-0608-0 (2021).

Section of Laparoscopic& Endoscopic Surgery, Branch of Pediatric Surgery, Chinese Medical Association. Guideline for laparoscopic hepatojejunostomy for choledochal cyst in children. Chin. J. Pediatric Surgery. 38(7), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3006.2017.07.002 (2017).

Farello, G. A. et al. Congenital choledochal cyst: video-guided laparoscopic treatment. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 5(5), 354–358 (1995).

Manigrasso, M. et al. Barbed suture and gastrointestinal surgery. A retrospective analysis. Open Med. (Warsaw Poland) 14, 503–508. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2019-0055 (2019).

Velotti, N. et al. Barbed suture in gastro-intestinal surgery: A review with a meta-analysis. Surg. J. R. Coll. Surg. Edinb. Ireland 20(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2021.02.011 (2022).

Yilmaz, O. et al. Successful outcomes in laparoscopic pyeloplasty using knotless self-anchoring barbed suture in children. J. Pediatr. Urol. 15(6), 660.e1-660.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.07.023 (2019).

Lukish, J. et al. Utilization of a novel unidirectional knotless suture during minimal access procedures in pediatric surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 48(6), 1445–1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.004 (2013).

Lee, J. S. & Yoon, Y. C. Laparoscopic treatment of choledochal cyst using barbed sutures. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 27(1), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2016.0022 (2017).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18(7), e3000410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410 (2020).

Diao, M., Li, L. & Cheng, W. Recurrence of biliary tract obstructions after primary laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy in children with choledochal cysts. Surg. Endosc. 30(9), 3910–3915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4697-5 (2016).

Wellner, U. F. & Keck, T. Leakage of hepaticojejunal anastomosis: Reoperation. Visceral Med. 33(3), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1159/000471909 (2017).

Hanna, G. B., Frank, T. G. & Cuschieri, A. Objective assessment of endoscopic knot quality. Am. J. Surg. 174(4), 410–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00129-3 (1997).

Joice, P., Hanna, G. B. & Cuschieri, A. Ergonomic evaluation of laparoscopic bowel suturing. Am. J. Surg. 176(4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00202-5 (1998).

Murphy, S. M., Rodríguez, J. D. & McAnulty, J. F. Minimally invasive cholecystostomy in the dog: Evaluation of placement techniques and use in extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Vet. Surg. VS 36(7), 675–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-950X.2007.00320.x (2007).

Giri, V., Yadav, S. S., Tomar, V., Jha, A. K. & Garg, A. Retrospective comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic pyeloplasty using barbed suture versus nonbarbed suture: A single-center experience. Urol. Ann. 11(4), 410–413. https://doi.org/10.4103/UA.UA_123_15 (2019).

Bülbüller, N. et al. Comparison of four different methods in staple line reinforcement during laparascopic sleeve gastrectomy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 6(10), 985–990 (2013).

Chan, V. W. K., Chan, P. K., Chiu, K. Y., Yan, C. H. & Ng, F. Y. Does barbed suture lower cost and improve outcome in total knee arthroplasty? A randomized controlled trial. J. Arthroplast. 32(5), 1474–1477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.015 (2017).

Raischer, H. B., Massalha, M., Iskander, R., Izhaki, I. & Salim, R. Knotless barbed versus conventional suture for closure of the uterine incision at cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Minimal. Invasive Gynecol. 29(7), 832–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2022.05.001 (2022).

Rosen, A. D. New and emerging uses of barbed suture technology in plastic surgery. Aesthet. Surg. J. 33(3 Suppl), 90S-S95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X13500048 (2013).

O’Kane, S. & Ferguson, M. W. Transforming growth factor beta s and wound healing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00120-3 (1997).

Barrientos, S., Stojadinovic, O., Golinko, M. S., Brem, H. & Tomic-Canic, M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regener. Off. Publ. Wound Heal. Soc. Eur. Tissue Repair. Soc. 16(5), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x (2008).

Hu, B., Wu, Z. & Phan, S. H. Smad3 mediates transforming growth factor-beta-induced alpha-smooth muscle actin expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29(3 Pt 1), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2003-0063OC (2003).

Tanaka, T. & Kishimoto, T. The biology and medical implications of interleukin-6. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2(4), 288–294. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0022 (2014).

Zaruby, J., Gingras, K., Taylor, J. & Maul, D. An in vivo comparison of barbed suture devices and conventional monofilament sutures for cosmetic skin closure: biomechanical wound strength and histology. Aesthet. Surg. J. 31(2), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X10395010 (2011).

Liu, X., Gao, P., Du, J., Zhao, X. & Wong, K. K. Y. Long-term anti-inflammatory efficacy in intestinal anastomosis in mice using silver nanoparticle-coated suture. J. Pediatr. Surg. 52(12), 2083–2087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.08.026 (2017).

Díaz-Güemes Martín-Portugués, I., Maria Matos-Azevedo, A., Enciso Sanz, S. & Sánchez-Margallo, F. M. Laparoscopic cholecystoduodenostomy in dogs: Canine cadaver feasibility study. Vet. Surg. VS 45(S1), O34–O40. https://doi.org/10.1111/vsu.12507 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. conceptualized and designed the study, provided study materials, managed the project and revised the manuscript; Y.L. worked on analysis of data, assisted with the animal experiments and wrote the manuscript; X.Y. and C.S. were responsible for the animal experiments and performed the in vivo surgery; C.Z. collected experimental data and prepared Figs. 2–6; L.Z. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The animal experiment was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No. 2023-AE111). The ARRIVE guidelines and ethical principles for animal experiments were adhered throughout the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Yang, X., Zhang, C. et al. Comparison of barbed suture and nonbarbed suture for laparoscopic cholecystoduodenostomy in rabbits: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 27150 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12652-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12652-w