Abstract

Rural left-behind women, as important potential participants in Digital Village Development, face multiple challenges including limited educational resources, weak digital skills, constrained economic conditions, and traditional socio-cultural barriers. These factors severely restrict the improvement of their digital literacy and their effective participation in digital village initiatives. Drawing upon the Socio-Technical Systems (STS) theory to understand the interplay between technology and social systems, and based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) theory to explore individual psychological processes, this study focuses on two key psychological variables—political trust and self-efficacy—to systematically explore how digital literacy influences the digital village participation of rural left-behind women through these intrinsic psychological mechanisms. The study aims to address the theoretical gaps in digital empowerment for marginalized groups and to provide solid theoretical and empirical support for promoting digital inclusion and targeted digital empowerment policies. This study utilizes field survey data from a major project funded by the National Social Science Fund of China. The sample was selected using a stratified random sampling method from several townships and villages in Shaanxi Province, yielding 1,083 valid questionnaires with an effective response rate of 91.3%. A Tobit regression model was applied to analyze the impact of digital literacy on participation in digital village initiatives. A panel conditional quantile regression was used to test the heterogeneity of this effect across different participation levels. Furthermore, a chained mediation model was employed to examine the mediating pathways of political trust and self-efficacy through which digital literacy affects digital village participation. The methodological framework is grounded in the SOR theory, providing an in-depth analysis of how digital technology stimuli influence participatory behavior through psychological states. The Tobit regression results show that digital literacy significantly enhances participation in Digital Village Development, the digital economy, and digital governance, but its effect on participation in digital benefit services is not significant. Conditional quantile regression reveals significant heterogeneity in the influence of digital literacy across different levels of participation. The chained mediation analysis indicates a significant direct effect of digital literacy (coefficient = 0.191, accounting for 60.72% of the total effect), alongside three indirect paths through political trust (17.17%), self-efficacy (16.53%), and the combined effect of political trust and self-efficacy (5.58%).These results reveal a complex multiple mediation mechanism through which digital literacy influences digital village participation among rural left-behind women. This study fills a research gap concerning the relationship between digital literacy and digital village participation among rural left-behind women and expands the application of the SOR theory in the context of Digital Village Development. The theoretical model proposed is not only suitable for the rural Chinese context but also holds universal significance for understanding digital empowerment mechanisms in marginalized populations. The findings emphasize that, beyond improving digital skills, enhancing political trust and self-efficacy is equally crucial. Accordingly, policymakers should design differentiated training and support strategies to comprehensively improve the digital literacy and participation capabilities of left-behind women, thereby facilitating the digital transformation of rural economies and societies. The sample of this study is limited to specific regions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. The analytical models do not encompass all potential influencing factors, and the complex role of socio-cultural contexts requires further exploration. Future research should expand the sample scope, incorporate multidimensional factors, and deepen the understanding and verification of digital empowerment mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the rapidly advancing digital era, the widespread adoption of information and communication technologies has emerged as a transformative force, reshaping societies and economies worldwide. While digitalization promises unprecedented opportunities for development, it also poses significant challenges, particularly for vulnerable and marginalized populations who often face a deepening digital divide1. This disparity in access, skills, and opportunities to effectively utilize digital technologies can exacerbate existing socio-economic inequalities, hindering inclusive growth and sustainable development, especially in rural areas2. Consequently, fostering digital inclusion and enhancing the digital literacy of all citizens has become a global imperative, recognized by international organizations and governments alike as fundamental to achieving comprehensive modernization.

Within this global context, China’s commitment to Digital Village Development represents a pivotal national strategy to leverage informatization for agricultural and rural modernization, echoing General Secretary Xi Jinping’s assertion that “without informatization, there can be no modernization; without modernization of agriculture and rural areas, there is no modernization of the entire country.” This strategic initiative, deeply rooted in socio-technical systems (STS) thinking, underscores the critical need to align technological advancements with human and organizational dynamics to ensure that digital transformation truly serves the needs of rural communities3. Central to this endeavor is the comprehensive enhancement of rural residents’ digital literacy, which is not merely about acquiring technical skills but about cultivating a core competency essential for active participation in the digital economy and governance, thereby injecting sustained momentum into rural revitalization4. However, despite these national efforts, significant disparities persist.This framework offers a clear explanatory path for understanding the dynamic interplay between skill acquisition, psychological empowerment, and behavioral engagement in the context of digital rural development.

Given the central role of individual capabilities in driving digital transformation, particularly within the frameworks of STS and Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) S-O-R, a fundamental construct for understanding rural residents’ digital engagement is digital literacy. Digital literacy refers to a set of core competencies and abilities that individuals in a digital society are expected to possess throughout their learning, work, and daily life activities. It encompasses multiple dimensions, including device operation and maintenance, information acquisition and evaluation, information interaction, content creation, as well as digital risk awareness and management5. Specifically, device access skills involve the operation and troubleshooting of digital devices; information acquisition includes browsing, filtering, and storing information; information evaluation emphasizes critical judgment of the authenticity, authority, and quality of information; information interaction covers communication, collaboration, and dissemination via digital platforms; content creation refers to the production, editing, and reprocessing of digital content; and digital risk management focuses on risk identification, privacy protection, and the implementation of security measures. Enhancing digital literacy not only facilitates the mastery of digital technologies but also equips individuals with the capabilities necessary for active and effective participation in the digital society, thereby holding significant theoretical and practical implications.

Despite the critical importance of digital literacy for the development of digital rural areas, enhancing digital literacy among rural residents faces numerous challenges. First, the uneven distribution of educational resources and the lack of targeted digital skills training constitute structural barriers to residents’ acquisition of digital competencies6. Second, factors such as prevailing sociocultural attitudes and varying levels of technology acceptance significantly constrain rural residents’ awareness and adoption of emerging digital technologies, thereby affecting their active participation in Digital Village Development7. Furthermore, some rural residents may develop technophobia and resistance due to insufficient understanding of the benefits of digital technologies, which undermines their motivation and willingness to improve their digital literacy. Therefore, promoting digital literacy in rural areas requires a multidimensional approach that comprehensively addresses challenges at institutional, cultural, and cognitive levels, recognizing that it is not merely a technical fix but a complex socio-technical endeavor demanding the harmonious alignment of technological systems with human and organizational capabilities.

Existing surveys8 indicate that the internet penetration rate and digital skills proficiency in rural areas of China are significantly lower than those in urban regions, reflecting notable deficiencies among rural residents in the application of digital technologies. This disparity, to a certain extent, limits their opportunities to participate in Digital Village Development. According to the Digital Divide Theory, unequal access to digital technologies and information exacerbates not only the urban-rural information gap but also further entrenches disparities in resource allocation and social opportunities9. More importantly, insufficient digital literacy may intensify information asymmetry, placing rural residents at a disadvantage in the digital economy, thereby widening the urban-rural divide. Therefore, it is imperative to systematically investigate strategies for enhancing digital literacy among rural residents, not just from a technical standpoint, but by understanding it as a holistic system that encompasses technology, people, and processes, providing theoretical support and practical guidance for bridging the digital divide and promoting comprehensive rural revitalization.

To address this challenge, China has introduced a series of policy documents aimed at enhancing digital literacy and skills among the entire population. As early as October 2021, the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission issued the “Action Plan for Enhancing Digital Literacy and Skills Nationwide,” which called for the implementation of measures to improve digital competencies across the population10. In December of the same year, the “14th Five-Year National Informatization Plan” was released, identifying the enhancement of digital literacy and skills as one of the ten priority actions11. The 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2023 further emphasized “promoting digitalization in education and building a lifelong learning society and a learning power at the national level”12. Additionally, the “2024 Key Tasks for Improving Digital Literacy and Skills” explicitly recognizes the raising of digital literacy as a crucial undertaking to meet the demands of the digital era, improve national quality, and promote comprehensive human development. It is also regarded as an indispensable pathway for China’s transition from a major internet country to a strong cyber power, contributing to bridging the digital divide and fostering common prosperity13.

Despite strong national emphasis and active efforts to enhance digital literacy across the population, the report titled Survey and Analysis of Digital Literacy in Rural China under the Rural Revitalization Strategy published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences reveals that the digital literacy level of rural residents remains relatively low. Notably, the average digital literacy score of rural villagers is significantly lower than that of urban residents by 37.5%14. More importantly, existing research has paid limited attention to how digital literacy influences rural residents’ participation in Digital Village Development and the underlying mechanisms of this effect. To what extent does lower digital literacy constrain opportunities and equity for villagers’ participation in digital rural initiatives? How does digital literacy affect villagers’ psychological cognition and behaviors, thereby facilitating or hindering their engagement in Digital Village Development? These questions warrant further in-depth investigation. Therefore, this study aims to explore the impact of digital literacy on rural residents’ participation in Digital Village Development and its mechanisms, with a view to providing theoretical foundations and practical guidance for improving digital literacy and promoting digital rural construction.

In the context of Digital Village Development, while enhancing the overall digital literacy of rural residents is crucial, focusing on and empowering rural left-behind women may hold greater strategic significance. Accelerated urbanization and industrialization have driven a large portion of the young labor force to cities, resulting in phenomena of rural hollowing and population left behind, with many women remaining in rural areas15. According to the Seventh National Population Census, there are approximately 250 million rural women in China, representing a significant human capital potential16. As emphasized in the Opinions on Accelerating the Revitalization of Rural Talent, priority should be given to developing rural human capital, with particular attention to nurturing local talent17. Furthermore, the Implementation Opinions on the “Women’s Action for Rural Revitalization” clearly identify rural women not only as beneficiaries of rural revitalization but also as important agents of rural development18. Therefore, fully tapping into the digital literacy and skills potential of rural left-behind women is of substantial strategic importance for narrowing the urban-rural digital divide and advancing comprehensive rural revitalization.

According to the Opinions on Strengthening Care and Services for Rural Left-behind Women, rural left-behind women are defined as those whose husbands have been continuously working or doing business outside the village for more than six months, while they themselves remain living in rural areas, aged between 20 and 60 years. This official definition provides a clear target population for this study’s focus on improving the digital literacy of rural left-behind women19.

However, existing research indicates that rural left-behind women face multiple challenges in acquiring digital skills, expanding information channels, and participating socially, largely due to structural and institutional factors. On one hand, from the perspective of gender role theory, traditional gender divisions assign women primary responsibilities for household care and agricultural labor, limiting their available time and energy to engage in digital skills training20. On the other hand, the scarcity of educational resources and lagging digital infrastructure in rural areas restrict their access to adequate digital learning opportunities and technical support21. Collectively, these socio-cultural gender norms not only shape their time allocation and social roles but also exacerbate inequalities in digital skill acquisition, constituting a critical barrier to enhancing their digital literacy.

Based on the above analysis, enhancing the digital literacy of rural left-behind women and promoting their active participation in Digital Village Development holds significant theoretical and practical value. As a marginalized group within digital rural initiatives, rural left-behind women face substantial barriers to improving their digital literacy due to resource scarcity, limited social participation, and constraints imposed by traditional gender roles. Theoretically, this study contributes to broadening the research perspective at the intersection of digital literacy and rural revitalization by elucidating the mechanisms through which digital skills enhancement influences the socio-economic behaviors of left-behind women. Practically, the findings provide a scientific basis for the formulation of targeted digital empowerment policies, foster innovative models for cultivating digital capabilities among rural left-behind women, and support the implementation of rural revitalization strategies. Ultimately, this research aims to narrow the urban-rural digital divide and advance the goal of common prosperity.

With the deepening advancement of Digital Village Development, the subjectivity of rural left-behind women has gradually become more prominent, and their status in rural communication research has risen from the periphery to a central focus22,23,24,25. Effectively enhancing the digital literacy of rural left-behind women and promoting their active participation in digital rural construction has become an urgent issue for academic inquiry. However, existing studies have yet to adequately explore the relational mechanisms among digital literacy, political trust, and self-efficacy, leaving the dynamics through which these factors collectively influence the social participation of rural left-behind women insufficiently theorized.

A systematic review of the literature reveals that current research on Digital Village Development primarily concentrates on its theoretical connotations26,27,28, salient characteristics29,30, development level measurements31,32,33, and empirical summaries34,35. Studies focusing on the behavioral dimensions of rural actors remain relatively limited, often centering on villagers as a whole rather than segmented groups such as village cadres36,37,38,39,40, e-commerce operators41,42,43, and agricultural producers44,45. Notably, few studies systematically investigate the unique group of rural left-behind women. As vital connectors within rural family life, rural left-behind women play a key role in linking three generations, yet their distinct needs and participation pathways in the context of digital ruralization are underexplored.Furthermore, literature on participation behaviors in digital rural areas generally acknowledges the significant impacts of participants’ age46, educational attainment, political affiliation47, and income level48 on their engagement levels. Nevertheless, most studies overlook the profound influence of socio-cultural environments on rural left-behind women’s participation, particularly the moderating roles played by key family members such as husbands49, elderly relatives, and children50. This limitation results in an incomplete understanding of the digital engagement of rural left-behind women and the challenges they face, underscoring the need to broaden research perspectives.

In political science and sociology, research on digital rural governance commonly identifies digital literacy, government trust, and self-efficacy as core endogenous variables influencing participation in digital rural initiatives. Modern political theory emphasizes that government credibility embodies the legitimacy of the state and forms the foundation of its relationship with the public. Government trust, as a critical public evaluation of the alignment between government values, decisions, and administrative actions with citizens’ expectations, directly affects rural left-behind women’s responsiveness to policies and willingness to engage51. Drawing on Trust Theory, government trust not only shapes individuals’ attitudes toward the state but also reinforces their identification with and compliance to public policies.Crucially, while digital literacy empowers individuals with enhanced information access and cognitive abilities, its influence on psychological perceptions and behavioral patterns is often mediated by intrinsic belief systems. This study particularly focuses on political trust and self-efficacy as key mediating variables.Specifically, Digital literacy enhances rural left-behind women’s capacity to access and comprehend government information, thereby increasing their trust in policies, improving their ability to evaluate such policies, and reducing cognitive uncertainties. This process stabilizes the coordinated relationship between the government and left-behind women, reflecting the pivotal role of information and resource acquisition in individual empowerment, as posited by Empowerment Theory. Simultaneously, self-efficacy—central to Social Cognitive Theory—determines individuals’ motivation and confidence in executing tasks. Empirical evidence suggests that enhanced self-efficacy significantly boosts rural left-behind women’s initiative in participating in digital rural construction, promoting a virtuous cycle between digital literacy and government trust52.

Based on the aforementioned literature and theoretical insights, this study aims to elucidate the interaction mechanisms among digital literacy, political trust, and self-efficacy, systematically exploring their impact pathways on rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development. The research intends to propose novel theoretical perspectives and practical strategies to support improvements in digital literacy and participation levels among rural left-behind women, thereby advancing the implementation of rural revitalization strategies.

To guide this investigation, the study addresses the following core research questions:

How does digital literacy influence the digital village participation behaviors of rural left-behind women?

What are the mediating mechanisms of government trust and self-efficacy in the relationship between digital literacy and digital village participation?

What are the differential manifestations of digital literacy’s influence on different levels of digital village participation?

To comprehensively address these questions and ensure robust findings, this study adopts a multi-faceted empirical strategy, leveraging a suite of complementary econometric models. This approach is specifically designed to account for the unique characteristics of our participation data, explore heterogeneous effects across different levels of engagement, and meticulously delineate complex mediating mechanisms.

This research offers several significant innovations and contributions. Theoretically, it represents a pioneering effort in systematically applying an integrated framework that uniquely synthesizes the SOR theory and the STS theory to the context of digital village participation. This integration fills a crucial research gap by providing a nuanced understanding of how individual psychological processes (as explained by SOR) interact with broader technical and social structures (as conceptualized by STS) to shape digital engagement. By innovatively incorporating political trust and self-efficacy as core mediating variables within this integrated analytical framework, the study precisely reveals the complex dynamic pathways through which digital literacy influences participation. This refined theoretical model not only expands the application boundaries of SOR theory in understanding social behavior within the context of digital transformation but also offers a novel socio-technical perspective for comprehending the digital empowerment mechanisms of marginalized groups, holding significant value for comparative research and theoretical generalization.

The findings of this study will provide empirical evidence for developing more targeted digital empowerment policies, particularly in assisting rural left-behind women’s digital capacity building within international development agendas. By clarifying the endogenous dynamic mechanisms of their digital village participation, this research not only contributes to the advancement of agricultural and rural modernization but also offers valuable theoretical and operational pathways for digital empowerment practices among vulnerable groups globally.

To systematically address these questions and provide a robust theoretical foundation, this study draws upon and integrates key theoretical perspectives. The subsequent section (Sect. “Theoretical framework”) will elaborate on the theoretical frameworks guiding this research, laying the groundwork for our investigation. Section “Hypotheses” will then present the detailed hypotheses derived from these frameworks. Following this, Sect. "Data sources and variable measurements" will describe the data sources, variable measurements, and the econometric models employed to rigorously test our hypotheses and investigate the complex relationships. Section "Results and discussion" will present and discuss the empirical results. Finally, Sect. "Conclusion and implications" will provide the conclusions and discuss their implications, while Sect. "Limitations and future research" will outline the study’s limitations and suggest directions for future research.

Theoretical framework

Addressing a critical gap in the existing literature, which often isolates individual psychological processes from broader socio-technical contexts in digital engagement research, this study proposes a pioneering theoretical framework designed to meticulously unravel the complex, multi-layered mechanisms through which digital literacy influences rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development. Our approach transcends conventional analyses by rigorously integrating two foundational theoretical perspectives: the micro-level explanatory power of the SOR theory and the macro-level contextual insights of the STS theory.

This synergistic integration not only enables a comprehensive, multi-faceted analysis but, crucially, provides a novel and robust lens to concurrently examine both the psychological underpinnings and the broader systemic forces that shape digital participation, directly underpinning the fundamental principles of our proposed chain mediation model. This model posits a sequential pathway: Digital Literacy → Political Trust → Self-Efficacy → Digital Village Participation. The theoretical foundations for each link and the overall chain are elaborated below.

Stimulus-Organism-Response theory

The SOR theory, primarily developed by Mehrabian and Russell53, posits that an external Stimulus (S) precipitates an individual’s internal Organism (O) state, which, in turn, manifests as a behavioral Response (R). This robust framework proves instrumental in dissecting the psychological and cognitive processes that translate external inputs into observable behaviors54,55. Within the specific context of rural digital inclusion, the SOR model provides a granular understanding of how individual predispositions and perceptions drive engagement.

In this study, digital literacy is precisely conceptualized as the primary external Stimulus (S), embodying an individual’s foundational capacity to effectively engage with and navigate the digital environment. The Organism (O) encompasses the intricate internal psychological states of rural left-behind women, specifically their political trust and self-efficacy. These mediating constructs critically shape their perceptions, evaluations, and motivations concerning digital technologies and governmental initiatives related to Digital Village Development. The Response (R) is subsequently operationalized as their active participation behaviors across various facets of Digital Village Development. Consequently, the SOR framework furnishes a detailed roadmap for analyzing the sequential psychological processes that bridge digital literacy to tangible participation outcomes in this unique demographic.

Socio-Technical systems theory

Originating from the pioneering work at the Tavistock Institute in the 1950s56, the STS theory emphasizes the inherent and inseparable interdependence between the technical subsystem (e.g., tools, processes, infrastructure, knowledge) and the social subsystem (e.g., people, roles, relationships, organizational culture). It fundamentally argues that optimal performance and sustainable development are achieved through “joint optimization,” where both components are designed, developed, and managed in a mutually supportive and adaptive manner57.

STS theory offers a critical macro-level lens for comprehending complex phenomena such as digital transformation within rural communities. It powerfully highlights that the introduction of new technologies profoundly reshapes social interactions, roles, and power dynamics, while concurrently, existing social structures and human capabilities significantly influence both the adoption and the eventual impact of technology. Applying STS theory thus underscores that sustainable digital development necessitates a meticulous consideration of how technology interfaces with human factors and social organization, decisively moving beyond a purely technological determinism to embrace a more holistic and integrated perspective58.

Integration of theoretical perspectives

While the micro-level focus of the SOR framework offers indispensable insights into individual behavioral pathways, its explanatory power remains constrained without a robust consideration of the broader environmental context. Conversely, STS provides a crucial macro-level understanding of technology-society interactions but frequently lacks granular insight into the specific individual psychological responses and motivations. Recognizing these complementary strengths and inherent limitations, our study innovatively synthesizes the micro-level focus of the SOR theory with the macro-level insights of the STS theory, thereby constructing a profoundly holistic and explanatory framework for analyzing digital village participation among rural left-behind women. This integration allows us to capture the dynamic interplay across different analytical levels59.

Specifically, the STS theory fundamentally enriches, contextualizes, and dynamically shapes each component of the SOR model:

Contextualizing the Stimulus (S): The availability, accessibility, and perceived usability of digital literacy-enhancing resources (e.g., tailored training programs, resilient digital infrastructure) are not merely exogenous stimuli. Instead, they are inherently and systemically shaped by the broader socio-technical system. STS enables us to comprehensively understand the systemic factors (e.g., responsive policy support, community-level technology adoption rates, the presence of social capital and networks) that critically determine the nature, efficacy, and ultimately the impact of these digital literacy stimuli.

Informing the Organism (O): The internal states of political trust and self-efficacy (Organism) are not developed in a vacuum; rather, they are deeply embedded within and influenced by the socio-technical environment. Political trust, for instance, is profoundly shaped by the perceived legitimacy, responsiveness, and fairness of the governmental social subsystem and its effective interaction with the technical subsystem (e.g., the transparency and user-friendliness of digital government platforms). Similarly, self-efficacy, while an individual psychological construct, is significantly bolstered or constrained by the perceived support from the social environment and the actual usability and reliability of the technical tools provided within the digital village ecosystem.

Framing the Response (R): Individual participation in Digital Village Development (Response) is not simply a personal, volitional choice but is powerfully influenced and bounded by the affordances and constraints intrinsic to the overall socio-technical system. The design principles of digital platforms, the nature and accessibility of digital services, prevailing social norms around technology use, and the collective benefits perceived within the community all play a decisive role in shaping, facilitating, or potentially hindering active participation.

This integrated framework, therefore, robustly posits that digital literacy and participation are not isolated individual phenomena but are profoundly embedded within, and reciprocally influenced by, the broader socio-technical fabric of the digital village. By systematically applying STS, our analysis of the SOR model rigorously considers the intricate reciprocal influences between the technical and social dimensions, leading to a significantly more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how to genuinely foster digital empowerment and sustained participation for rural left-behind women. This holistic approach transcends simplistic deterministic views, offering a powerful and robust lens to capture the dynamic and emergent properties of human-technology interaction within a complex and evolving social setting, ultimately contributing fundamentally to the “joint optimization” of Digital Village Development. The specific mechanisms and fundamental principles of our proposed chain mediation model, directly derived from this integrative theoretical lens, are further elaborated in the following section.

Underlying mechanisms of the chain mediation model

This section further elaborates on the core mechanisms and fundamental principles that underpin our proposed serial mediation model: Digital Literacy → Political Trust → Self-Efficacy → Digital Village Participation. Drawing upon the sequential Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) logic and the socio-technical system (STS) dynamics, our framework posits that the entire chain is driven by two overarching principles: The Principle of Digital Governance Transparency and The Principle of Socially Reinforced Empowerment.

The Mechanism of Digital Governance Transparency (Digital Literacy → Political Trust):

Enhanced digital literacy, conceptualized as an initial stimulus (S) representing improved individual interaction with the technical subsystem, empowers rural left-behind women to more effectively access, evaluate, and comprehend governmental information through digital channels. This improved access and understanding significantly reduce information asymmetry and foster greater transparency within the broader socio-technical system, particularly regarding governance and public services (components of the social subsystem). By providing reliable and accessible information, the well-functioning technical dimension enables a more accurate and positive perception of governmental actions and intentions, which is critical for cultivating political trust (an internal organismic state, O). This principle underscores how optimizing the technical system’s information delivery serves as a foundational catalyst, not merely for individual understanding, but for strengthening institutional trust and legitimacy within the social subsystem60,61.

The Mechanism of Socially Reinforced Empowerment (Political Trust → Self-Efficacy → Digital Village Participation):

This principle articulates the subsequent sequential links: Political Trust → Self-Efficacy and Self-Efficacy → Digital Village Participation. A higher level of political trust (an organismic state, O, reflecting belief in the social subsystem’s responsiveness, legitimacy, and support) creates a crucial psychological foundation. This positive expectation regarding institutional interaction subsequently leads to a significant increase in self-efficacy (another organismic state, O) among rural left-behind women. When individuals trust the system (a socio-technical environment), they perceive their participatory efforts as more likely to yield positive and secure outcomes, thereby reducing perceived risks and psychological barriers to engagement. This conducive social environment, fostered by trust, robustly encourages individuals to leverage their nascent digital capabilities, gain mastery experiences, and believe more strongly in their inherent ability to succeed. Consequently, this enhanced self-efficacy—a direct and profound result of interacting within a trusted socio-technical environment—directly translates into greater motivation, sustained effort, and perseverance in engaging with digital village initiatives (the behavioral Response, R). This principle, fully embodying the “joint optimization” spirit of STS, compellingly illuminates how a robust and trusted social environment is absolutely instrumental in fostering individual agency and strategically propelling active digital participation, demonstrating the powerful interplay between systemic trust and individual empowerment62,63.

In sum, our multi-layered theoretical framework robustly posits that digital literacy initiates a sequential psychological process where enhanced technical competence first cultivates a positive perception of the societal environment (political trust) within the socio-technical system. This newly cultivated trust then critically bolsters individuals’ belief in their own agency (self-efficacy), which ultimately drives active digital participation. This profoundly nuanced understanding provides a robust basis for explaining the dynamic interplay between individual capabilities, psychological states, and social structures in promoting digital inclusion, thereby contributing fundamentally and uniquely to the “joint optimization” of Digital Village Development and offering crucial insights for policy and practice.

This complex interplay forms the basis for the multi-layered hypotheses to be detailed in the following section.

Hypotheses

Drawing upon the integrated theoretical framework of the SOR theory and the STS theory, as discussed in Sect. 2, this section details the hypotheses exploring the complex interplay between digital literacy and rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development. We conceptualize digital village initiatives as dynamic socio-technical systems, where the effectiveness of technological tools is inherently linked to the social structures and human agency, thus influencing individual psychological states and behaviors as framed by the SOR model.

Digital literacy and participation in digital village development

This study draws upon the definition of digital literacy from the “14th Five-Year Plan for National Informatization” by the Cyberspace Administration of China64, which regards digital literacy as a comprehensive set of abilities that citizens in a digital society should possess in their learning, work, and daily lives. These abilities multidimensionally encompass the acquisition, creation, use, evaluation, interaction, sharing, innovation, protection, and ethical management of digital information. As key participants in digital rural construction, the digital literacy level of rural left-behind women directly influences their ability to effectively utilize digital technologies and integrate into and shape the modern rural socio-technical landscape.

Digital village participation is defined as a comprehensive process that involves the widespread application of digital technologies, information methods, and internet thinking to achieve modernization of rural governance, intellectualization of agricultural production, precision of rural services, and smart transformation of rural lifestyles (referencing the “China Digital Village Development Report”65. Specifically, it refers to the actual degree and depth of participation by rural women in digital agricultural production, digital governance collaboration, and the utilization of digital services.

Based on the SOR theoretical framework, this study views digital literacy as a crucial external stimulus (S) influencing rural women’s digital village participation. Differences in digital literacy levels directly impact individuals’ cognitive and emotional states (O), which in turn drive their behavioral responses (R) in digital rural-related activities.Within the broader socio-technical system of the digital village, digital literacy empowers individuals to navigate and contribute to both the technical components (e.g., using apps, accessing information) and the social components (e.g., online community engagement, understanding policy information) of this evolving environment.

Integrated with the Uses and Gratifications Theory, digital literacy not only enhances rural women’s willingness to proactively utilize digital media to satisfy their information, social, and economic needs, but also boosts their motivation and depth of participation in digital rural activities. Consequently, digital literacy, as a fundamental ability and psychological cognitive condition, serves as a core driving force for promoting rural women’s engagement in digital rural construction.

While acknowledging that the development of digital literacy itself is subject to various constraints in rural environments, such as lagging infrastructure investment, shortages of educational resources, traditional cultural concepts, and gender role expectations, this study focuses on exploring the theoretical mechanisms through which acquired digital literacy influences their participation behaviors. Based on the aforementioned theoretical analysis and practical context, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: The digital literacy of rural women is positively related to their participation in digital rural activities.

Digital literacy, political trust and participation in digital village development

China’s unique social and cultural context, including its long historical traditions and cultural values, profoundly shapes public perceptions of government legitimacy and authority66,67. Political trust, reflecting the level of public confidence in the political system and its institutions, is widely considered a crucial psychological factor influencing citizens’ policy compliance, collective action participation, and support for government decisions68. In the context of Digital Village Development, political trust acts as a vital bridge between the government’s digital initiatives (part of the technical subsystem) and citizens’ acceptance and engagement (part of the social subsystem), influencing the overall effectiveness of the socio-technical system. Amidst the accelerating digital village construction in China, particularly for rural left-behind women in transition, their level of political trust in the government not only affects their acceptance of digital-inclusive agricultural policies but is also a vital prerequisite for their active integration into and participation in digital life, enabling them to benefit from digital development dividends.

This study adopts the S-O-R theoretical framework, widely applied in psychology and behavioral research, to understand the behavioral logic of rural left-behind women within the context of digital villages. In this framework, we regard digital literacy as an external Stimulus (S), which acts upon the internal psychological state of rural left-behind women – the Organism (O), specifically, political trust. Political trust, serving as a mediating variable, further drives and influences their Response (R) in digital village construction, manifested as active participation behavior.

Political trust is not a monolithic construct but a complex concept involving multiple facets. In examining the political trust of rural left-behind women, this study rigorously follows the main dimensional division of political trust among Chinese farmers as proposed by existing research69 and other scholars, namely: (1) Generalized Trust: primarily referring to farmers’ overall evaluation and general confidence in the government as a whole and its institutions; (2) Will and Capacity: focusing on farmers’ perceptions of the government’s willingness and ability to solve specific problems, uphold justice for farmers, and provide effective public services. These two dimensions of trust are interrelated but distinct in their focus, jointly forming a complete picture of rural left-behind women’s political trust. This study will explore the impact of digital literacy based on these two dimensions.

Specifically, enhanced digital literacy empowers rural left-behind women to more effectively access and evaluate governmental information through digital channels. This improved access reduces information asymmetry and fosters greater transparency within the socio-technical system, which is critical for cultivating political trust. For instance, by navigating official online platforms and understanding government announcements, they can form a more accurate and positive perception of government actions and intentions, thereby strengthening both their generalized trust and their perception of the government’s will and capacity to serve them.

Digital literacy70 plays a critical role in shaping the political trust of rural left-behind women, primarily influencing the dimensions of trust through the following two aspects: Firstly, enhancing digital literacy contributes to strengthening rural left-behind women’s “generalized trust.” Through digital channels, they can more effectively access macro information such as government policies and development goals, and utilize authoritative digital platforms to understand the overall image and performance of the government. This enhanced ability to acquire and evaluate information leads to a more accurate and balanced perception of the government as a whole and its institutions, reducing overall distrust caused by information asymmetry or bias, thereby improving generalized trust71. From an STS perspective, this improved information flow between the technical subsystem (digital channels) and the social subsystem (citizens’ perception of government) is crucial for fostering a cohesive and trusting environment. Secondly, digital literacy also significantly impacts their perception of the government’s “will and capacity.” Digital literacy enables them to conveniently access and utilize digital public services closely related to their daily lives, such as online government services, legal consultation, and complaint submissions. Through these specific interactions, rural left-behind women can directly experience the efficiency, responsiveness, and problem-solving abilities of government services. Successful experiences of expressing demands through digital platforms and receiving positive feedback reinforce positive evaluations of the government’s willingness and ability to solve specific problems and uphold justice. Relevant policies aimed at promoting digital inclusion in rural areas, enhancing the digitalization of public services, and encouraging grassroots governance transparency and participation provide technological support and channels, further strengthening this perception72.These positive interactions exemplify how effective design and implementation of the technical subsystem (digital public services) can positively influence the social subsystem (citizens’ trust and perception of government capability), illustrating the principle of joint optimization within the digital village.

In sum, grounded in the S-O-R theoretical framework, the external stimulus (digital literacy), by strengthening the mediating role of the organism (political trust), drives individual behavioral responses (participation in Digital Village Development).

Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Political trust mediates the relationship between digital literacy and rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development.

Digital literacy, Self-Efficacy and participation in digital village development

Self-efficacy, introduced by Bandura as a core concept of social cognitive theory, refers to individuals’ belief in their capability to perform specific tasks successfully. Within the context of Digital Village Development, it specifically denotes rural left-behind women’s confidence in their ability to acquire and apply digital skills to participate effectively in rural development activities73.

Using the SOR framework, digital literacy serves as the external stimulus (S) that initiates internal cognitive and affective processes within the rural women’s ‘organism’ (O), here represented by self-efficacy—i.e., their subjective perception of digital capability and confidence. This organismic state then drives their response (R), namely, the actual participation in Digital Village Development initiatives.

The formation of self-efficacy in rural women results from interaction between digital literacy and various contextual factors. Mastery experiences gained through hands-on use of digital tools directly enhance self-efficacy by providing tangible evidence of capability. Observational learning from peers participating in digital initiatives offers vicarious reinforcement. Moreover, social environmental support, including encouragement from family, community networks, and government digital inclusion programs, acts as facilitating stimuli that strengthen belief in one’s abilities. Government-engineered training and infrastructure improvements provide additional external resources that empower rural women to overcome technological barriers and thus develop higher self-efficacy74.This interaction highlights how components of the socio-technical system—both technical resources and social support—are critical for fostering individual belief in capability, contributing to a more effective social subsystem.

Logically, digital literacy—comprising both fundamental IT operation skills and advanced information evaluation and utilization abilities—enhances rural women’s self-efficacy by equipping them with the knowledge and experience to feel competent in digital tasks. As their digital literacy improves, they encounter fewer uncertainties and gain confidence, which psychologically empowers them to engage more actively in Digital Village Development behaviors such as online agricultural management, e-commerce, and participation in inclusive digital finance75.

Therefore, self-efficacy mediates the impact of digital literacy on digital village participation by internalizing external stimuli into confident agency, consistent with the SOR model’s pathway of Stimulus → Organism → Response.

Consequently, this study proposes:

H3: Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between digital literacy and rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development.

Digital literacy, political trust, Self-Efficacy and participation in digital village development

This study posits a sequential mediation model wherein digital literacy (S) influences political trust, which in turn shapes self-efficacy (O), subsequently impacting participation (R) in Digital Village Development.This complex pathway unfolds within the dynamic socio-technical system of the digital village, where individual psychological states and behaviors are continually influenced by the interaction of technical tools and social structures.

Digital literacy equips rural left-behind women with crucial skills and cognitive abilities requisite for effective digital engagement76. As an initial stimulus (S), enhanced digital literacy is anticipated to foster positive cognitive and affective responses conducive to digital participation77.

Within the ‘organism’ (O), political trust—defined as confidence in the political system and its institutions78—is posited as the primary mediating psychological state. Congruent with H2, digital literacy may bolster political trust by improving access to and comprehension of governmental information and by facilitating positive experiences with digital public services79. Elevated political trust fosters a sense of stability and perceived legitimacy concerning government-led digital initiatives.This trust, a key element of the social subsystem, is critical for the seamless operation and acceptance of the technical subsystem’s offerings within the digital village.

This cultivated political trust is theorized to establish a more conducive environment for the development of self-efficacy. For rural left-behind women, trust in governmental digital initiatives can diminish perceived risks associated with new technologies80 and augment the perceived value of participation. Such a supportive context encourages engagement in activities yielding mastery experiences and facilitates vicarious learning from peers; both are recognized as critical antecedents of self-efficacy within Social Cognitive Theory81. Essentially, political trust can lower psychological barriers, rendering individuals more receptive to leveraging their digital literacy and cultivating confidence in their digital capabilities.This demonstrates how a robust social subsystem, characterized by trust, can positively reinforce the individual’s interaction with the technical subsystem, leading to enhanced self-efficacy.

Consequently, while digital literacy directly contributes to skill acquisition, its impact on self-efficacy is potentially amplified within a context of political trust. Heightened self-efficacy—an individual’s conviction in their digital capabilities82—subsequently motivates more active engagement in Digital Village Development (R), such as e-commerce or online learning initiatives83.This sequential process, where digital literacy (interaction with technology) builds trust (social acceptance) which in turn boosts self-efficacy (individual belief), culminating in participation, exemplifies the principles of joint optimization at play in creating an effective socio-technical system for rural development.

This model refines the SOR framework by delineating a sequential process within the ‘organism’ (O): digital literacy (S) impacts political trust, which then influences self-efficacy, ultimately triggering the behavioral response (digital village participation).

Based on this conceptualization, we propose:

H4: Political trust and subsequently self-efficacy sequentially mediate the relationship between digital literacy and rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development.

Data sources and variable measurements

Data sources

The data utilized in this study were obtained from a rural field survey conducted by the research team of the National Social Science Fund Major Project titled “The Role and Function of New Media in Rural Governance under the Rural Revitalization Strategy.” The survey was carried out in Shaanxi Province between July and September 2023. Drawing upon the definition of rural left-behind women provided in the “Guidelines on Strengthening Care and Services for Rural Left-Behind Women”84, which specifies women aged between 20 and 60 who reside and live in rural areas while their husbands work or engage in business outside for more than six consecutive months, this study specifically focuses on this demographic as its research subjects. Shaanxi Province was selected based on findings from the Western Digital Economy Research Institute, which highlight that although Shaanxi’s overall digital economy development level remains below the national average, its growth rate is comparatively high, ranking fifth nationwide in digital economy expansion in 2022. This distinctive profile provides a robust empirical basis for the present research.

To ensure the representativeness of the survey sample, the research team consulted with relevant experts in the field of rural revitalization and comprehensively considered various influencing factors, including regional digital economy development levels, geographical location, desired sample capacity, and sample response rates. Based on these considerations, four cities in Shaanxi Province – Xi’an, Yulin, Xianyang, and Tongchuan – were selected as the survey areas for distributing electronic questionnaires. All survey personnel were master’s or doctoral candidates specializing in New Media from “Project 985” universities and had undergone professional survey training.

To ensure the statistical reliability of the research findings, the team conducted a rigorous a priori sample size calculation. Specifically, we set the significance level (α) at 0.05, statistical power (1 - β) at 0.80, and selected a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5). Based on the sample size calculation formula, the required sample size per group was approximately 63. Considering four research variables, the recommended total sample size should be at least 252 cases. The study ultimately obtained 1083 valid samples, which not only significantly exceeded the minimum recommended sample size but also controlled the 95% confidence interval error within ± 3%, ensuring extremely high validity of the statistical conclusions.

This study employed a Stratified Multi-Stage Probability Sampling method. Through a rigorous statistical sampling procedure, system bias and random error were minimized to the greatest extent possible. The sampling process adhered to the principles of probability sampling, ensuring the randomness and representativeness of the sample. The specific steps were as follows: First, from the four cities of Xi’an, Xianyang, Yulin, and Tongchuan, two townships were purposefully selected based on geographical location and socioeconomic characteristics, forming a stratified sampling frame. Within each township, 4–5 villages were randomly selected using Simple Random Sampling, with randomness ensured by a random number generator. In each village, 20–40 rural left-behind women were selected using Systematic Random Sampling to maximize the reduction of sampling bias.

During the survey implementation, the research team collaborated with village committees and women’s federations and followed a standardized survey protocol: (1) obtaining face-to-face informed consent; (2) administration by professionally trained local interviewers; (3) providing small monetary compensation for participation; and (4) personalized follow-up for special circumstances. A total of 1186 electronic questionnaires were ultimately collected. After strict quality screening, 1083 valid questionnaires were obtained, resulting in a valid response rate of 91.3%. Criteria for excluding invalid questionnaires included: consistent selection of the same response for all items and abnormally short response time for single items (< 30 s).

The study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants provided informed consent prior to the study, and the research protocol received academic approval from the School of Journalism and New Media, Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Formal ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board was waived for this study. This procedure is in compliance with the 2023 revision of China’s “Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans,” which exempts research from formal review if it exclusively uses fully anonymized data and poses no risk of harm to participants—conditions that this study fully meets.

Variables

Participation in digital village development

The dependent variable of this study is the digital village participation of rural left-behind women, measured based on the framework proposed in the China Digital Village Development Report65. This construct comprises three main dimensions that capture participants’ engagement in Digital Village Development activities: digital economy, digital governance, and digital benefit services.

Digital Economy (DE): Refers to the integration of advanced information technologies—such as the Internet of Things, big data, and artificial intelligence—into rural economic activities, facilitating smart agriculture, e-commerce marketing, smart tourism, and inclusive finance.

Digital Governance (DG): Encompasses the application of digital tools to enhance data integration and sharing in village governance, including online disclosure of party affairs, village matters, financial management, e-government platforms, grid-based management, and smart emergency response systems.

Digital Benefit Services (DS): Covers digital applications aimed at improving the welfare of rural left-behind women, including “Internet + Education,” “Internet + Healthcare,” “Internet + Social Security,” and online public legal and social assistance services.

To assess the frequency and degree of engagement in these activities, specific behavioral indicators under each dimension were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Very Often”) (see Table 1 for details). The Likert scale allows for fine-grained measurement of participation intensity and reflects variability in individual engagement levels.

This measurement approach was chosen to capture the multidimensional and continuous nature of digital village participation more effectively than binary or categorical scales. The questionnaire was adapted with simplified language and practical examples appropriate to the respondents’ cultural and educational context to ensure clarity and data quality.

The scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.864, indicating high reliability.

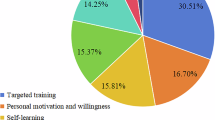

Digital literacy

According to the “2023 China Rural Digital Development Research Report,” as of November 2022, the number of mobile phone users in rural areas reached 290 million, with a mobile internet penetration rate of 56.9%85. This study measures the digital literacy level of left-behind women in rural areas based on the current status of mobile phone and internet penetration. Digital literacy is defined by referencing the “2022 National Plan for Improving National Digital Literacy and Skills” issued by the Cyberspace Administration of China, and is divided into six dimensions: Device Access (DA), Information Acquisition (IA), Information Evaluation (IE), Information Interaction (II), Content Production (CP), and Digital Risk (DR). Device Access refers to the use of smartphones as well as the ability to interconnect devices and troubleshoot faults; Information Acquisition includes skills to browse, search, and store digital information via mobile phones; Information Evaluation pertains to the ability to judge the authenticity of online information; Information Interaction involves online chatting, social interaction, and forwarding of information via mobile phones; Content Production indicates the capability to independently create and modify text, images, and videos; Digital Risk encompasses awareness of online risks and measures to protect personal information.

These six dimensions are operationalized through 14 binary-choice items (Yes = 1, No = 0), which specifically reflect the skills and behaviors across the defined dimensions.The specific items for each dimension are detailed in Table 2.To assess the internal consistency reliability of this 14-item binary scale measuring digital literacy, the Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20) was calculated. The overall scale yielded a KR-20 coefficient of 0.88, indicating excellent internal consistency for the measure in this sample.

The reason for selecting a binary scale is as follows: the target respondents are primarily rural left-behind women, whose cultural and digital literacy levels are relatively limited. The simple Yes/No format reduces cognitive burden, avoiding possible confusion and errors caused by multi-level scales; such design simplifies the questionnaire structure, improving survey efficiency and participation rates while reducing fatigue and omissions. Binary data also facilitates subsequent classification statistics and the application of entropy weighting methods, enhancing measurement stability and scientific rigor. Considering the rural survey environment constraints, the binary format is more suitable for paper-based or electronic questionnaires administered onsite, effectively ensuring data quality and validity.

To ensure scientific measurement, the entropy weight method was applied to normalize and weight the items in each dimension, integrating them into a composite digital literacy index that guarantees the objectivity and rationality of indicator weights. This design balances scientific rigor with the respondents’ actual acceptance capabilities, improving the measurement’s validity and applicability.

A pilot study involving 100 rural left-behind women was conducted to refine the digital literacy items and confirm their applicability. The pilot revealed that the proposed dimensions accurately reflected participants’ digital experiences. For example, smartphone use was prevalent (around 85.5% in the pilot sample), and participants reported engaging in activities consistent with the defined dimensions, from basic information access and interaction to aspects of content creation and risk management. This feedback supported the appropriateness of the 14-item binary scale for the main study.

Control variables

According to digital divide theory, individuals with differing background characteristics exhibit significant variation in their ability to access digital resources, acquire digital skills, and engage with digital technologies in productive and daily life activities. Failure to adequately control for these background variables may compromise the validity of empirical findings86. Accordingly, this study recognizes the distinctive family role of rural left-behind women as the “nucleus” spanning three generations—elders, middle-aged adults, and youth—and draws on prior literature to identify ten potential factors influencing their level of participation in the digital countryside87.

These factors encompass individual-level characteristics, including age, educational attainment, political affiliation, and monthly income; as well as family-level characteristics, such as spouse’s education level, spouse’s monthly income, co-residence with children, eldest child’s education level, eldest child’s monthly income, and the number of elderly household members. These ten variables are incorporated as control variables in the analysis to account for confounding influences on rural left-behind women’s digital village participation.

Mediating variables

This study employs political trust and self-efficacy as mediating variables influencing digital village participation among rural left-behind women. Both constructs represent subjective perceptions, necessitating precise measurement to minimize errors and ensure robust analytical results.

Political Trust(PT)was assessed using five specific indicators designed to capture multiple facets of participants’ trust in local township party committees and government78. Three general indicators measure overall political trust and respect within the rural community: (1)The degree to which respondents believe the township party committee and government genuinely care about farmers; (2) The perceived political prestige of the township party committee and government in the rural community; (3) The respect afforded to exemplary party members and cadres affiliated with the township committee and government.

To further refine this construct, two additional indicators differentiate political trust across two critical dimensions: Desire Dimension: Whether the township party committee and government are perceived as willing to act in farmers’ interests; Ability Dimension: Whether they are regarded as capable of effectively protecting and promoting farmers’ interests.

The combination of these indicators provides a comprehensive evaluation of political trust, addressing both affective and competence-based components. Each item reflects a specific belief or attitude, measured to capture nuanced participant perceptions.

All items were assessed on a five-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree/Strongly Oppose, 2 = Disagree/Oppose, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree/Support, and 5 = Strongly Agree/Strongly Support, with higher scores indicating greater levels of political trust. The use of a Likert-type scale allows for graded responses reflecting varying intensities of trust rather than a binary classification, enabling a more sensitive and continuous measurement of this subjective construct. The political trust scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.813.

Self-Efficacy(SE)was measured using the Chinese version of the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) developed by Schwarzer et al.88. The GSES consists of ten items reflecting a unidimensional construct further categorized into two conceptual subdomains: Outcome Expectations: Beliefs regarding the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes based on one’s actions; Efficacy Expectations: Confidence in one’s capability to execute behaviors necessary to produce those outcomes.

Example items capture concrete tasks such as overcoming difficulties, initiating actions, and persisting despite obstacles, reflecting the individual’s perceived capacity to succeed in various challenging situations relevant to rural life.

Responses to the GSES items utilize the same five-point Likert scale as described above (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating stronger perceived self-efficacy among respondents. The use of a Likert scale facilitates the measurement of individual differences in confidence levels along a continuous spectrum, enhancing reliability and discriminative power. The Chinese version of the GSES showed excellent reliability in this sample, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.875.

Additionally, special attention was given to ensure the questionnaire was clear and comprehensible to rural left-behind women respondents. The language was simplified and culturally adapted to align with their educational background and cognitive habits. Practical examples and contextual explanations accompanied key items to facilitate accurate understanding and response, thereby enhancing data quality and reliability.

Model specification

To thoroughly investigate the complex dynamics of rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development, and to ensure the robustness and depth of our findings, this study employs a multi-faceted empirical strategy. This approach integrates three distinct, yet complementary, econometric models, each designed to address specific aspects of our research questions and the inherent characteristics of our data. Primarily, given the bounded and censored distribution characteristics of our dependent variable, the Tobit regression model is utilized to provide unbiased and consistent estimates of the average effects. Subsequently, to capture the heterogeneous impacts of digital literacy across different levels of participation, quantile regression is employed. Finally, to delineate the sequential psychological mechanisms through which digital literacy influences participation, a chain mediation model is constructed. This comprehensive methodological framework allows us to move beyond simple correlational analysis, offering a more nuanced and statistically rigorous understanding of digital village participation.

Tobit regression model

To accurately capture the complex dynamics of rural left-behind women’s participation, and crucially, to address the bounded and censored distribution characteristics of our dependent variable, digital village participation (DVit), this study constructs a panel Tobit regression model based on the baseline regression framework. This initial analysis serves a critical purpose in robustly testing our foundational hypothesis H1, which posits a direct positive relationship between digital literacy and digital village participation. By providing unbiased and consistent estimates of the effect of digital literacy on the latent propensity for participation, the Tobit model ensures that our assessment of this direct relationship is statistically sound. Furthermore, this robust estimation of the direct effect forms a crucial baseline and validation for the more complex mechanisms explored in our subsequent quantile and chain mediation models, especially as it provides the most accurate average effect of the independent variable (digital literacy) on the dependent variable (digital village participation) while correctly accounting for the data’s specific distribution.

A significant proportion of our sample exhibits participation scores at the lower (1) or upper (5) bounds of the Likert scale, meaning traditional Ordinary Least Squares regression would yield biased and inconsistent estimates due to its inability to distinguish between observed boundary values and potentially more extreme underlying latent values, thus misrepresenting the true underlying relationships. The specific model is defined as:

Where:DVit is digital village participation (dependent variable).Diit is digital literacy (independent variable).Pt it (political trust) and Seit (self-efficacy) are the mediators.Xit represents control variables.µi denotes individual fixed effects, and εit is the random error term.c1 is intercept.

The observed Digital Village Participation (DVit) relates to the latent continuous variable (DVit*) as follows:

The core advantage and necessity of the Tobit model lies in its ability to simultaneously model both the probability of participation and the intensity of participation, thereby providing unbiased and consistent estimates of the effects of independent variables on the latent (uncensored) participation level. Through maximum likelihood estimation, with the lower censoring point set at 1 and the upper censoring point set at 5, the model effectively overcomes the limitations of traditional linear regression models in handling bounded dependent variables. The model not only corrects sample selection bias but also enables accurate marginal effect estimation, providing a more precise analytical tool for in-depth analysis of the nonlinear impact of digital literacy on digital village participation.

Quantile regression model

To comprehensively reveal the multidimensional impact mechanisms of digital literacy on digital village participation, this study selects five critical quantiles (0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 0.90) to construct a panel conditional quantile regression(CQR) model. Compared to traditional mean regression, quantile regression can profoundly analyze the heterogeneity and asymmetry of independent variables’ effects on dependent variables, exhibiting robustness to extreme values and providing a more nuanced perspective of effect analysis.

The model is specifically constructed as:

In model (3), Qτ represents the conditional quantile at specific quantile levels. The selection of five quantiles holds significant statistical meaning: the 0.10 quantile reflects low-participation characteristics, the 0.25 quantile captures participation features in the lower quartile, the 0.50 quantile represents median-level participation, the 0.75 quantile captures participation features in the upper quartile, and the 0.90 quantile reflects high-participation characteristics.

The model estimation employs the Least Absolute Deviation estimation method, generating 95% confidence intervals through Bootstrap method (5,000 resampling iterations). The analytical strategy includes comparing coefficient differences across different quantiles, analyzing the heterogeneity of independent variables’ impacts on dependent variables, and revealing potential nonlinear action mechanisms.

This multi-quantile panel data analysis approach not only enriches research methodologies but also significantly enhances the robustness and persuasiveness of research conclusions. By comprehensively portraying the multidimensional impacts of digital literacy on digital village participation and unveiling heterogeneous effects at different participation levels, this study provides deeper insights into the complex mechanisms of digital village participation, transcending the limitations of traditional mean regression.

Chain mediation model

To rigorously investigate the sequential mediating pathway through which digital literacy (Di) influences rural left-behind women’s participation in Digital Village Development (Dv), this study employs Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). SEM is a powerful multivariate statistical analysis technique particularly well-suited for examining complex causal relationships, including multiple mediation effects, within a single, comprehensive statistical model. This approach offers several advantages over traditional regression-based methods for mediation analysis, such as allowing for the simultaneous estimation of all hypothesized paths, accounting for measurement error (if latent variables were used), and providing global fit indices to assess how well the entire theoretical model fits the observed data.

Based on our integrated theoretical framework, we hypothesize a sequential mediation process: Digital Literacy (Di) → Political Trust (Pt) → Self-Efficacy (Se) → Digital Village Participation (Dv). In this SEM framework, the following relationships are specified and estimated:

Path 1 (Di → Pt): The effect of digital literacy on political trust, representing the initial step in the sequential process.

Path 2 (Pt → Se): The effect of political trust on self-efficacy, indicating how the first mediator influences the second.

Path 3 (Se → Dv): The effect of self-efficacy on digital village participation, representing the final link in the chain.

Direct Path (Di → Dv): The direct effect of digital literacy on digital village participation, controlling for both political trust and self-efficacy.

Control Variables: All control variables (Xit) are included and regressed on Political Trust, Self-Efficacy, and Digital Village Participation in the model to account for their potential confounding effects.

The primary focus of this analysis is the sequential indirect effect of digital literacy on digital village participation, transmitted first through political trust and then through self-efficacy. This specific indirect effect is calculated as the product of the three sequential path coefficients: (Path Di→Pt) × (Path Pt→Se) × (Path Se→Dv).

The statistical significance of this sequential indirect effect, along with all direct and other indirect effects, will be assessed using bootstrapping procedures (e.g., 5,000 resamples). Bootstrapping is highly recommended for mediation analysis in SEM as it does not rely on assumptions of normality for the sampling distribution of the indirect effects.

Furthermore, to evaluate the overall tenability of the proposed sequential mediation model, various model fit indices will be examined, including but not limited to the Chi-square (χ2) statistic, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Given the panel nature of our data, a panel SEM approach will be employed to appropriately handle the nested data structure and within-individual variance.