Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) represents a particularly aggressive subtype of breast cancer lacking expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), leading to restricted treatment options and unfavorable outcomes and prognosis. This research employs immunoinformatics and reverse vaccinology strategies to develop novel multi-epitope protein and mRNA vaccines targeting TNBC-associated antigens. By using a detailed scoring system, we identified seven extracellular proteins (TROP-2, EpCAM, MUC1, NECTIN4, Folate Receptor α, Mesothelin, α-Lactalbumin) and two intracellular proteins (MAGE-A, NY-ESO-1) as targets for the vaccine. Through a thorough process of predicting and validating epitopes, we discovered 18 MHC-I epitopes, 1 MHC-II epitope, and 2 B-cell epitopes with considerable binding affinity and population coverage (87.75% for the Persian-Iranian cohort), with an emphasis on the MHC-I pathway. The constructed protein vaccine demonstrated favorable physicochemical characteristics, structural stability, non-toxicity, and non-allergenic potential. TLR4 was found to be the primary pattern recognition receptor for adjuvant interaction, and molecular docking illustrated strong binding strength. In constructing the mRNA vaccine, we included N-5′ m7GCap, 5′ UTR, Kozak sequence, signal peptide (tPA), MHC epitopes, linker, MITD sequence, stop codon, 3′ UTR, and poly-A tail. Consequently, the design of the mRNA vaccine integrated optimized codon sequences with relevant regulatory components, achieving a Codon Adaptation Index of 0.93. Furthermore, we propose an innovative four-part mRNA vaccine approach to balance therapeutic effectiveness with clinical practicalities. Both vaccine formulations showed intense immune stimulation in silico, indicating their potential as promising candidates for immunotherapy against TNBC, which will require further experimental exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is the second-highest cause of death in the United States1, with significant impacts on medical resources and patient suffering. The most common cancers vary by gender, with prostate and breast cancers being prevalent in men and women, respectively2. Advances in breast cancer treatment, particularly early diagnosis and the use of hormone therapy and monoclonal antibodies, have significantly improved survival rates, with a 99% five-year survival rate for localized breast cancer3,4,5,6.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is among the most challenging subtypes of breast cancer to treat, making up around 10–15% of all breast cancer cases7. It is defined by the lack of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, making hormone-blocking therapy and anti-HER2 treatments ineffective. It is more common in younger women, particularly those under 40, Black women, and those with BRCA1 mutations8. TNBC presents considerable therapeutic difficulties because of a scarcity of targeted treatment choices and a poor prognosis compared to hormone receptor-positive subtypes, and often affects younger individuals who are not typically included in early diagnostic screening programs. As a solution, we designed a vaccine using a bioinformatics-driven vaccine design to stimulate the immune system against the surface antigens of Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) cells9,10,11. The five-year survival rate for metastatic TNBC remains disappointingly low, highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies12,13,14,15.

Traditional cancer treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, share a common complication: they can cause toxic damage to healthy tissues and normal cells due to their non-specific mechanisms. These complications can sometimes be more severe than the cancer itself, especially in advanced cases or among elderly and disabled patients, making treatment unfeasible. Hence, an optimal cancer treatment strategy should focus on precisely identifying cancer cells, akin to the adaptive immune system found in vertebrates. This approach utilizes the immune system to target cancer cell proteins through enhancement or manipulation, or by using synthetic or modified components of the immune system16,17,18,19,20.

Immunization stimulates the memory or the adaptive immune system to recognize specific antigens and mount a strong immune response while sparing healthy tissue. Cancer vaccines represent a rapidly advancing field within immunotherapy, with the potential to induce long-lasting anti-tumor immunity through epitope-based immunization. Identifying and targeting tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) expressed by TNBC cells can stimulate both cellular and humoral immune responses, effectively eliminating cancer cells. The effectiveness of protein vaccines against infections has been well established, and the widespread use of nucleic acid vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated their safety, typically resulting in fewer side effects than traditional cancer treatments. This indicates a promising direction for cancer treatment, particularly for TNBC21,22,23.

The introduction of reverse vaccinology and immunoinformatics has transformed vaccine development by facilitating the rapid identification of potential vaccine candidates through computational methods. These techniques allow for systematic screening of protein targets, prediction of epitopes, and optimization of vaccine design, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with traditional vaccine development24.

Several strategic options exist for achieving maximum immunization with cancer vaccines. One important consideration is the choice between a uni-epitope and a multiepitope vaccine. The multiepitope approach is considerably superior for three main reasons. First, it provides maximum population coverage. In cancer vaccine strategies, binding epitopes to the MHC system is essential for effectively presenting them to the immune system. Given the wide variety of alleles that code for the variable parts of MHC-I and II, each with different binding capabilities to peptides of various sequences, a vaccine composed of multiple epitopes is essential to ensure strong binding to as many MHCs as possible, considering the range of alleles present in the population25,26. Second, tumor heterogeneity and variation must be taken into account. Tumors in different individuals often exhibit a high rate of variation and mutation (especially in the case of TNBC). If the expression of a target protein decreases over time or is low, the presence of other target protein epitopes can help maintain ongoing antitumor immunization27. Third, the multiepitope approach allows for versatility in the immune response. Epitopes can stimulate immunogenicity against tumors through various pathways, including MHC-I, MHC-II, and B-cell activation26,28,29. This comprehensive approach, which targets multiple proteins and includes both MHC-I and MHC-II, is called a multi-target, multi-epitope, and multi-class (we named it a multi-TEC vaccine) vaccine. It enables a more adaptable and thorough immunization strategy25,26,27,28,29,30.

In terms of the vaccine delivery system, protein vaccines are primarily administered through subcutaneous or intramuscular injections. For cancer vaccines, researchers have also explored injection methods that target lymph nodes31,32. The primary solution for delivering nucleic acids into cells has been using a viral vector. Traditionally, viral vectors have been the main method for delivering nucleic acids into cells, and this approach was used to develop nucleic acid vaccines for COVID-19. While viral vectors are often employed to transfer DNA, they can also facilitate the transfer of mRNA. A more recent innovation involves using mRNA encapsulated in nano-lipid coating, a technique that was also used in the production of the COVID-19 vaccine, demonstrating both safety and effectiveness. A significant advantage of nano-lipid coatings is their ability to enhance the immune response, acting as an adjuvant33,34,35,36,37.

Concerning adjuvants and their role in immune system modulation, cancer vaccines harness the power of the immune system; however, many patients may experience immune suppression due to factors such as illness, chemotherapy, or psychological stress. Common adjuvants used in protein vaccines include Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF)38 and Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) agonists, which help to amplify the immune response. As part of the innate immune system, TLRs are critical in recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Specifically, TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 bind to various components from bacteria39. Our research involved using a TLR4 agonist and designing protein structures aimed at optimizing adjuvant placement for improved receptor binding.

For mRNA vaccines, proteins are synthesized within cells, so direct interaction with surface TLRs is unnecessary. Endosomal TLRs 3, 7, 8, and 9 bind nucleic acids. Two mRNA vaccine adjuvant strategies include using nano lipid particles (NLPs) for delivery, which can interact with cell surface TLRs40, and employing nucleotides like R848 as TLR7 and 8 agonists41.

Anti-immune checkpoint agents: If the vaccine proves successful in clinical trials, it should be accompanied by anti-immune checkpoint (ICP) agents, such as monoclonal antibodies against PD1, PDL1, or CTLA4. This is necessary because many cancer cells can activate the immune checkpoint pathways and suppress the activity of T cells against them42.

Despite advancements in cancer immunotherapy, significant challenges persist in developing effective vaccines against TNBC. TNBC’s heterogeneous characteristics, coupled with immune evasion mechanisms and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, create considerable obstacles that must be navigated through innovative vaccine design strategies. Hence, there is a pressing need to develop novel vaccines that can overcome these limitations and deliver effective therapeutic interventions against TNBC. In pursuit of the future of cancer treatment, we adopted a cancer vaccine strategy for this research. Initially, we identified target proteins and proposed a selection system for these targets, which future software applications could utilize. Next, employing bioinformatics tools and visually inspecting the secondary and tertiary structures of the target proteins, we identified MHC epitopes and developed an algorithm for their discovery, which could also be implemented by artificial intelligence (AI) software in the future. Finally, we designed protein and mRNA vaccines from both immunological and structural perspectives. Multi-target, multi-epitope, and multi-class features characterize our designed vaccines. These vaccines underwent thorough assessment by numerous bioinformatic tools to evaluate their features, function, and stability. As a novel approach, we propose dividing the epitopes used for constructing mRNA vaccines into four groups and designing four separate five-epitope mRNA vaccines for administration at two-week intervals. This innovation may represent a significant advancement in vaccine design and clinical application.

Methods

Initially, we developed a scoring system to select protein targets from those previously identified in articles and chose seven extracellular proteins and two intracellular proteins, focusing on the MHC-I pathway, and designed multiepitope mRNA vaccines. Then we identify linear and conformational epitopes in extracellular proteins, linear epitopes in intracellular proteins, and B-cell conformational epitopes in extracellular proteins. Then, a protein vaccine was designed using MHCs and B-cell epitopes, linkers, adjuvants, and PADRE and evaluated to assess toxicity, allergenicity, optimal secondary and tertiary structures, stability, physicochemical parameters, and immune response. To design an mRNA vaccine, we utilized N-5′ m7GCap, 5 ′ UTR, Kozak sequence, signal peptide (tPA), MHC epitopes, linker, MITD sequence, stop codon, 3 ′ UTR, and poly-A tail. In addition to the 19 MHC epitope vaccine, we proposed a novel strategy for designing a multi-epitope mRNA vaccine in cancer immunotherapy. We divided the primary vaccine into four separate five-epitope vaccines to facilitate separate administration. A comprehensive workflow scheme of methods illustrates the four main processes, including target protein selection, epitope identification, protein vaccine design, and mRNA vaccine design, with key decision points and validation steps clearly indicated, implemented through systematic computational approaches (Fig. 1).

Graphical abstract: Diagram of the workflow of the proposed methodology of the steps used to reach the possible validity of the vaccine design for TNBC. Abbreviations: MHC, major histocompatibility complex; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; HTL, helper T lymphocyte; CAI, Codon Adaptation Index; CFD, Codon Frequency Distribution.

Target protein selection

Target protein selection was based on a scoring system with a maximum of 10 points, evaluated using four parameters: (1) cellular localization (5 and 3 points for extracellular, and intracellular antigens, respectively), (2) tumor specificity (0–2 points), (3) prognostic significance (1 point for poor prognosis), and (4) previous therapeutic targeting success (0–2 points). This led to the selection of nine target proteins: seven extracellular (TROP-2, EpCAM, MUC1, NECTIN4, Folate Receptor α, Mesothelin, α-Lactalbumin) and two intracellular (MAGE-A, NY-ESO-1). Protein sequences and structural data were sourced from UniProt and RCSB PDB.

In the first step, we should select proteins as targets. In the subsequent step, we should identify epitopes with the highest potential for binding to the MHC system within these targets. The ideal protein for targeting should be absent in healthy cells while being expressed on the surface of cancer cells. This allowed for precise targeting, damaging cancer cells while sparing healthy ones.

Given the importance of this feature, we might define the following conditions:

-

1.

A protein might be expressed exclusively in tumor cells, resulting from genetic mutations during the malignancy process, known as Tumor-Specific Antigen (TSA)43.

-

2.

Alternatively, a protein might be expressed in other cells throughout the body but is significantly more abundant in tumor cells, referred to as Tumor-Associated Antigen (TAA). Of course, there are variable degrees of expression. For instance, Trop-2 is typically found in embryonic cells and absent in post-embryonic cells. However, it is observable on the surface of breast cancer cells, particularly in TNBC, similar to other specific normal proteins found on the surfaces of embryonic cells43.

-

3.

Cancer Testis Antigens (CTAs) are a large group of cancer proteins exclusively expressed in testicular germ cells and not present in any cell type within a woman’s body. However, they can be found on the surface of cancer cells44.

-

4.

While some groups of proteins exist on the surface of normal cells, their expression may significantly increase in malignant cells. For instance, the HER2 receptor in breast cancer or proteins like mesothelin are more abundantly expressed and undergo structural changes in conditions such as mesothelioma, ovarian tumors, and TNBC45.

Based on a review of articles, several proteins emerged as potential targets. In alignment with our goal of incorporating a clinical perspective and prioritizing it, we have adopted a conservative clinical approach to selecting target proteins. The first step in this process is to ensure that the target proteins are as tumor-specific as possible. This means they should either not be expressed in healthy cells at all or should not be expressed in the healthy cells of individuals of the same age and gender. Our second conservative approach focuses on proteins successfully targeted by other methods, ensuring that the safety of targeting these proteins has been demonstrated, without aggregation during production until administration due to their large size.

We developed a scoring method utilizing the UniProt website, incorporating article reviews and structural analyses. We applied it to each candidate protein to select the top nine proteins as targets. Subsequently, we focused on identifying additional epitopes within proteins with higher scores.

Each candidate protein could accrue scores based on four features through our scoring system for selecting target proteins. The total scores available were 10, and the higher a protein’s score, the more suitable it was as a target. The scoring features are:

-

1.

The selected protein must either be extracellular and located on the cell surface or be a receptor whose extracellular portion can be targeted for immunization. We assigned 5 scores if the protein was extracellular, and 3 scores were awarded if the MHC-I system presented an intracellular protein, such as a cancer-testis antigen.

-

2.

Tumor-Associated (Specific) Antigen. Ideally, the protein exhibits specificity for cancer cells, is minimized or absent in healthy cells, thereby ensuring targeted immunity and minimizing harm to non-cancerous tissues. We assigned 0–2 scores based on the degree of tumor specificity of the protein. Assign 2 points for a protein completely absent in healthy cells of the specified age and gender. Assign 1 point for proteins that are transformed or highly expressed in tumors. Assign 0 points for proteins in normal cells involved in everyday functions.

-

3.

The target protein should have been associated with poor tumor prognosis, influencing its growth, proliferation, and metastasis. Immunization against such a protein could potentially halt tumor progression. We assigned one score for the target protein’s adverse role in prognosis and 0 for others.

-

4.

If previous studies have successfully targeted this protein for immunotherapy, it confirms its safety and suitability as a target. We assigned 0–2 scores based on the extent of prior success in targeting this protein. Two scores are assigned for proteins: a score of 2 for those against which immunotherapy has successfully passed trials and is now on the market, a score of 1 for those that have entered clinical trials, and a score of 0 for all others.

Selected proteins

Using the scoring system and reviewing the sequence and 3D structure of proteins, we selected 7 extracellular proteins (TROP-2, EpCAM, MUC1, NECTIN4, Folate Receptor α, Mesothelin, α-Lactalbumin) and 2 intracellular proteins (MAGE-A, NY-ESO-1) among numerous candidates mentioned in the articles. The features of selected proteins are summarized in Table 1.

Epitope identification

Epitope identification utilized various computational methods for comprehensive immunogenic coverage. Linear epitope prediction was conducted using IEDB tools for MHC-I (8–10 amino acids) and MHC-II (15–18 amino acids). Conformational epitopes were identified through structural analysis on Swiss Model and iCn3D, targeting surface-exposed areas. Safety evaluation of predicted epitopes was performed using ToxinPred and AllerTop to ensure non-toxicity and non-allergenicity. At the same time, population coverage analysis was done with IEDB tools to assess coverage among different ethnic groups.

The sequence of the protein and its extracellular part was identified using the “UniProt” website, and we evaluated the second and third structures of the proteins using the “RCSB PDB” website. Additionally, we utilized the “Swiss Model”81 and “iCn3D”82 websites to assess the third structure and surface of the target proteins, respectively. Finally, we employed the “IEDB” website to identify epitope sequences with high binding strength to MHC alleles and to verify this for selected epitopes83,84.

Linear epitope finding

In this step, the IEDB site was used to identify epitope sequences with the highest potential for binding to various MHC alleles. The IEDB software examined the binding strength of any part of the sequence of the target protein with the sequence of the MHC-I or MHC-II variable region, encoded by different MHC alleles. In that case, the software generated separate tables for MHC-I and MHC-II. These tables displayed the binding strength of any 8–10 sequence in the protein to different MHC-I alleles or 15–18 sequence in the protein to different MHC-II alleles (all of which could be adjusted manually) in descending order of binding strength.

In the typical bioinformatics approach, this output could be considered epitopes for in silico vaccine design; however, we included two additional stages to filter the results. Initially, we preferred epitopes on the surface of extracellular proteins to maximize their availability for immune system components. As the second point, we considered the binding strength of epitopes with multiple alleles to achieve maximum population coverage.

Conformational epitope finding

Another type of epitope, known as a conformational epitope, was identified by examining the protein’s tertiary structure. The protein surface was scanned using various methods to determine a binding site of suitable length. Amino acids that form a protrusion or crest on the protein surface can be considered suitable epitopes, which are accessible to the immune system. In the amino acid sequences, one may be on the surface. At the same time, the next is deep, or due to the juxtaposition of two linear forms, two adjacent amino acids on the surface may be far apart in the overall sequence. Using the Swiss Model site and the iCn3D site, we searched the surface of the target proteins and identified the best conformational epitopes.

MHCs epitope finding for intracellular target proteins

This study focused on cell surface proteins due to their accessibility to T cell receptors or antibodies after immunization. However, there is significant global attention on Cancer Testis Antigens, particularly the MAGE-A group and NY-ESO-1. After fragmentation by the proteosome, their fragments could be presented to the immune system via the MHC I system if they bind strongly to MHC I. For epitope discovery, we exclusively utilized the output of the IEDB site, selecting the strongest binding epitopes for NY-ESO-1. This choice reflects the necessity of epitopes that the MHC I system presents for successful immunization.

Regarding MAGE-A, complexity arose due to its multiple subtypes, with MAGE-A1, A2, A3, A4, and A6 potentially expressed in triple-negative breast cancer85. To address this complexity, we identified common sequences among MAGE-A1, A2, A3, A4, and A6, identifying three areas for further examination. After screening these areas using the IEDB site, only one epitope, YEFLWGPRAL, demonstrated strong binding affinity with HLA B*40:01.

Safety evaluation

Finally, the found epitopes were checked by “Toxinpred”86 and “AllerTop”87 sites for safety (to be nontoxic and nonallergenic).

B cell epitopes

We used the “IEDB” site with default parameters to find B-cell epitopes. However, the suggested epitopes were visually filtered using the “PDB” site. It was discarded if a suggested epitope was found to be deep, located in the helical section (even partially), or not extracellular. Only epitopes that were as exposed as possible and not in a helical structure were selected and evaluated by “Toxinpred” and “AllerTop” sites for safety.

Epitopes evaluation

After finding the epitopes and checking them for safety (nontoxic, not allergenic) and before going to the next stage and using them for protein vaccine design, two other evaluations were planned for the epitopes:

-

1.

Population coverage was another important consideration. We used the “IEDB” site to calculate population coverage. We entered all the alleles that had a strong binding with our epitopes into the software to see what percentage of the population of each race had at least one of these alleles, for the vaccine to be effective in that race84.

-

2.

For verifying the output of the “IEDB” site about the strength of the docking of our epitopes and MHC alleles, we used the HPEPDock88 site with default parameters to examine the docking of the epitope and allele which the “IEDB” site calculated a strong binding between them.

Protein vaccine design

The protein vaccine incorporated selected epitopes, adjuvants (HP91 from HMGB1 and RS09), appropriate linkers (AAY, GPGPG, KK, EAAAK), and PADRE sequence for enhanced immunogenicity. The adjuvant-TLR4 interaction was validated through molecular docking using the HPEPdock server. Stability optimization was achieved through our “Repeating Epitope Balancing” method, a strategy that improved overall vaccine stability as measured by ProtParam analysis.

Adjuvants

We identified two peptides as adjuvants for the protein vaccine: HP91 and RS09.

High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), a nuclear protein, is essential for preserving the structure and function of chromosomes. If released into the cytoplasm, it can be considered a signal of nuclear destruction and severe cell damage, initiating autophagy. Additionally, if parts of HMGB1 reach the extracellular space, they function as DAMPs, stimulating the immune system response through toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other mechanisms. Macrophages can actively secrete parts of HMGB1 in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharides, further stimulating the immune system89.

HP91 (DPNAPKRPPSAFFLFCSE) is a part of HMGB1 that can stimulate both cellular and humoral immune responses against protein antigens, leading to increased production of cytokines90. Alongside, RS09 is a synthetic peptide (APPHALS) that can be used as an adjuvant for cell surface toll-like receptors91. We examined the docking and binding strength of these two adjuvants with TLR4 by the HPEPDock site, and logically, the desired arrangement is that one locates the adjuvants at the surface of the protein to maximize availability for cell-surface TLR4. We tried our best to achieve this goal.

Linkers

We use the linker AAY between MHC-I epitopes and before them, GPGPG between MHC-II and PADRE, and before them48,92 KK between B-cell epitopes and before them92, EAAAK after or before adjuvants48,87, and 6xH at the end as a His tag.

PADRE

The Pan HLA DR-binding epitope is a 13-amino acid peptide that can strongly bind to almost all MHC-II HLA DR alleles. The peptide AAATLWKAAKFVA is commercially available and commonly used in research48, while the peptide AGLFQRHGEGTKATVGEPV is used in another article92. Although the presentation of PADRE to Helper T cells via MHC-II does not contribute to immunization against epitopes expressed by cancer cells, it can activate Helper T cells and thus the entire immune system.

Final structure

The antigen-presenting cells (APCs), especially dendritic cells, take up the protein vaccine through endocytosis. This uptake can occur at the injection site, or the vaccine protein may reach the lymph node and then be trapped by APCs or B cell receptors. Therefore, before endocytosis, there is no immune response or concern about the docking of the entire protein molecule, except for the interaction between the adjuvant and TLRs. This interaction is evaluated and found to be beneficial for stimulating the innate immune system. After protein processing in the cytosol by the proteasome (immunoproteasome for APCs), the epitopes are released. The MHC-I binding epitopes, through cross-presentation, induce immunization by stimulating the cloning of cytotoxic T cells whose receptor’s CDRs can bind with the epitope-MHC-I complex. These cloned cytotoxic T cells can then destroy cancerous cells containing that epitope. Meanwhile, the MHC-II binding epitopes induce immunization by activating helper T cells similarly, which in turn activate the entire adaptive immune system and B cells. If the intact protein vaccine reaches the lymph node, B cell epitopes can bind to B cell receptors and trigger antibody production against the epitope. The final sequence of the designed protein vaccine, along with its components and arrangement, is shown in Fig. 2. Furthermore, to replicate the immune response, we employed the “C-IMMSIM” website and its associated software93.

Another important factor of a protein vaccine is the stability of the vaccine. We used the ProtParam tool on the “Expacy” site to check the stability94. To achieve the most stable form, we created a method that we named “Repeating epitope balancing.” After arranging the epitopes (see result section, 3.3.1. Adjuvant TLR4 docking evaluation; and related figure), a repeat of one of the MHC I epitopes far from the first one was added to the MHC I area, and then the stability was measured. By this method, we found that some epitopes can increase stability, and so by repeating them, we can achieve a more stable form of vaccine.

mRNA vaccine design

The mRNA vaccine was constructed, and codon optimization was performed using GenScript tools, with evaluation of Codon Adaptation Index (CAI), GC content, and Codon Frequency Distribution (CFD).

In the design of mRNA vaccines, it is essential to utilize MHC-binding epitopes, while B-cell epitopes are not used. The antigen, whether a protein or a polysaccharide, must reach the B cell surface in lymphoid tissues to activate B cells and produce antibodies against it.

Considering the intracellular protein synthesis mechanism of mRNA vaccines, only the protein fragment can exit the cells by binding with MHC molecules after the proteasome processes the protein. No protein can exit the cells except through MHC-binding epitopes that bind to MHC molecules. Therefore, any protein structure intended to interact outside the cells, such as B-cell epitopes or adjuvants binding to cell surface TLRs, cannot be effective when encoded by an mRNA vaccine.

mRNA vaccine components

This is the structure of our mRNA-designed Vaccine from 5’ (N terminal) to 3’ (C terminal):

N-5′m7G Cap − 5′ UTR - Kozak sequence - Signal peptide (tPA) - MHCs Epitopes and linkers - MITD sequence - Stop codon – 3′ UTR – Poly (A) tail.

An AAY linker links together selected epitopes, and preceding them are EAAAK and GPGPG linkers92,95. These linkers are specific to epitopes, allowing them to act separately. They are breakable, flexible, and strong. As previously mentioned, no peptide adjuvant has been selected, and the nano lipids used as carriers of the mRNA have the potential for immune system stimulation. Additionally, a Kozak sequence should be added as a translation initiation site, along with a start codon96 in the ORF and a stop codon97.

Two other sequences were added to the construct:

-

1.

The tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) secretion signal sequence (UniProt ID: P00750) was incorporated in the 5’ region. This signal peptide sequence is necessary for facilitating the secretion of epitopes after translation98.

-

2.

The MHC-I molecule targeting sequence (MITD) (UniProt ID: Q8WV92) was included in the 3’ parts of the mRNA vaccine. This sequence is required to guide epitopes to the MHC-I complex in the endoplasmic reticulum99.

Additionally, to stabilize the structure, it is essential to add a cap to the 5’ region, 120–150 bases of adenine (A Tail) to the 3’ end of the structure40, and untranslated regions of β globin in the 5’ region and untranslated regions of α Globin in the 3’ region (UTRs) to the mRNA vaccine structure96. The designed vaccine was named ZBR01.

Codon optimization tools are essential for improving mRNA vaccine translation within the host cell. Consequently, we employed the GenSmart codon optimization tool found on the “Genscript” website to achieve optimal expression of the mRNA vaccine in human cells. To assess the quality of the optimized structure, we employed the “GenScript” tools and calculated the CAI, the percentage of GC bases, and the CFD.

An innovative arrangement of four-part mRNA vaccine

We were facing a paradox: (as explained in the discussion section), more epitopes in a vaccine might seem advantageous from one perspective, while fewer epitopes were preferred from another. To address this, we proposed an innovative protocol: dividing epitopes into four groups (see Table 4) and designing a separate mRNA vaccine for each group.

To implement this, we divided the 19 epitopes into 4 groups. Initially, we repeated one of the most important of them and then arranged them into four groups of five epitopes each. This arrangement, based on a clinical perspective, ensures that the first vaccine includes epitopes from two target proteins, with epitopes from two other target proteins added to each subsequent vaccine (except for the last vaccine, which includes epitopes from three proteins.

Results

Target protein selection and validation

Nine target proteins were identified based on a comprehensive scoring system, with scores ranging from 6 to 9 points. These selected proteins encompass a variety of cellular localizations and functional roles in the pathogenesis of TNBC, thereby providing broad antigenic coverage for vaccine development. The selected target proteins, along with their features and scores determined by our scoring system, are shown in Table 1 in the methods section.

Epitope identification and characterization

Systematic computational screening identified 21 high-quality epitopes, comprising 18 MHC-I epitopes, 1 MHC-II epitope, and 2 B-cell epitopes. Population coverage analysis indicated 87.75% coverage for the Persian Iranian population, with substantial coverage across various ethnic groups, demonstrating the potential applicability of the vaccine design. Molecular docking validation using HPEPDock showed strong binding interactions between the predicted epitopes and their respective MHC alleles, with binding scores aligning well with IEDB predictions, thereby supporting the validity of the computational approach.

To ensure the avoidance of any toxicity, we utilized the “Toxinpred” site with default parameters for each epitope86, and to mitigate allergenicity, we employed the “AllerTop” site with default parameters for the evaluation of each epitope87. In the final selection process, we identified 18 MHC-I epitopes, 1 MHC-II epitope, and 2 B-cell epitopes from the targeted proteins. The list of epitopes, their originating proteins, and the MHC alleles with which they exhibit very high binding strength (as calculated by the IEDB site) are presented in Table 2, and conformational epitopes that were found by our team are shown in Fig. 3. The detailed results of epitope finding for the target proteins of TNBC are exhibited in the Supplementary Material 1 (Excel file) in terms of restricted MHC, median binding percentile, antigenicity, toxicity, and allergenicity.

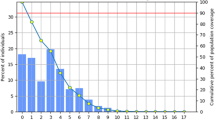

Population coverage of epitopes

The population coverage of these epitopes (population coverage by MHC I, II alleles that code MHC I, II that had strong binding with epitopes that were found in this study and are shown in the right column of Table 2 for Persian Iranian people was calculated to be 87.75% by the ‘IEDB’ site. The population coverage of these MHC alleles for other races was also calculated by the IEDB site and is shown in Table 3.

Docking between selected epitopes and HLA

As mentioned in the methods section, we utilized the HPEPDock site88 with default parameters to evaluate the docking between the epitopes and MHC alleles, which were calculated by the ‘IEDB’ site software, to exhibit strong binding. The results confirmed those obtained from the ‘IEDB’ site (see Fig. 4; Table 4).

Protein vaccine characterization

The final protein vaccine construct exhibited optimal physicochemical properties, with enhanced stability indicated by a reduction in the instability index from 42.22 to 37.84 following epitope balancing optimization. A comprehensive safety analysis indicated non-toxicity and non-allergenicity across all tested parameters. Structural analysis confirmed appropriate secondary structure composition and acceptable quality in tertiary structure prediction. Immune simulation studies indicated robust activation of immune system components, including sustained antibody production, cytokine release, and T-cell proliferation.

Adjuvant TLR4 Docking evaluation

We identified two peptides as adjuvants for the protein vaccine: synthetic peptide RS09 (APPHALS) and HP91(DPNAPKRPPSAFFLFCSE), which is a part of HMGB1. By checking the docking of each peptide using the HPEPDock site (http://huanglab.phys.hust.edu.cn/hpepdock/), we selected HP91 as the first option due to its better docking score (-223 vs. -140) and its ability to dock to any surface of TLR4 (see Fig. 5), but the shorter adjuvant RS09 has more chance to be whole length exposure at the surface of protein vaccine.

Physicochemical properties of protein vaccine

After designing and testing the protein’s stability using the ProtParam tool on the “Expasy” site, the results indicated instability within the protein molecule. Therefore, we developed a method called Repeating Epitopes Balancing, as explained in the method section. Out of our 19 MHC I epitopes, seven showed a positive effect on the stability of the whole protein vaccine molecule. By repeating four of them, we managed to reduce the instability index according to ProtParam from 42.22 (unstable) to 37.84 (stable). And other parameters produced by the “Expasy” site are shown in Table 5.

Safety of protein vaccine

Toxicity was assessed using the ‘ToxinPred’ site86. We conducted tests using all possible lengths: 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 amino acids. All sequences received SVM scores below 0.0, indicating they were non-toxic. Only sequences with lengths between 15 and 25 amino acids, particularly those from the HP91 adjuvant, received SVM scores ranging from 0.01 to 0.50. However, these scores can still be considered non-toxic, especially given that HP91 is a component of normal human proteins.

The allergenic potential was assessed using the “AlgPred” site100, which suggests that a protein is allergenic if its score exceeds 50; otherwise, it is considered non-allergenic. The result obtained was: ‘Submitted sequence is not allergenic.’ Predicted Score = 1.97. Additionally, another assessment was conducted using the “AllerTop” site87, which indicated ‘No evidence’ of allergenicity.

According to the NCBI site, only the HP91 adjuvant, which is a part of HMGB1, shows similarity to human proteins, while the other sequences are only similar to hypothetical or unnamed proteins.

The secondary structure prediction of the protein vaccine

After arranging epitopes, linkers, adjuvants, and PADRE as in Fig. 2 and repeating four MHC I epitopes for increasing stability, numerous arrangement trials for minimizing Helix, the final sequence has been achieved, and the secondary structure was calculated by the “I-TASSER” site101 is shown below:

APPHALSEAAAKAAATLWKAAKFVAGPGPGDLSLRCDELVRTHHIAAYYEFL

WGPRALAAYAQFHPTVTVAAYQEYHEHRHLAAYKETKIGDKIAAYLQVERTLI

YAAYVLVPPLPSLAAYSTAPPAHGVAAYETSDVVTVVAAYRMSAPKNARAAYL

VRPSEHALAAYSSVPSSTEKAAYKSNWHKGWNWAAYKEFTVSGNILAAYDTL

DTLTAFYAAYMSFEPAKERAAYTSTEITCSEKEAAYYYVDEKAPEFAAY

EYFVKIQSFAAYKETKIGDKIAAYETSDVVTVVAAYAQFHPTVTVAAYYEFL

WGPRALKKVKGTTSSRSFKHSRSAAKKTHSYKVSNYSRGSGGPGPGAGLFQRH

GEGTKATVGEPVEAAAKDPNAPKRPPSAFFLFCSE.

Helix 130/399 = 32.6%, Strand 197/399 = 49.3%, Coil 72/399 = 18%.

The tertiary structure prediction of protein vaccine

We utilized the “I-TASSER” site for predicting the secondary and tertiary structures, as well as generating the Ramachandran plot.

Five models for the third structure were suggested by the “I-TASSER” site. Among the top five models, they were fairly similar, and based on the suggested parameters, the first model was chosen.

Because it showed no similarity to any known proteins, prediction of the third structure is challenging for most sites, and although the parameters of this site’s models do not indicate high accuracy for third structure prediction, they are deemed fairly acceptable (Fig. 6).

Model #1 details: C-score: -6.890, TM-score: 0.150+-0.012.

The figure displays the most accurate third structure prediction of the protein vaccine, viewed from different angles by rotation along three axes. The structure is depicted in ribbon style with rainbow coloring, where violet represents the N-terminal and red denotes the C-terminal. This visualization was generated using the ‘I-TASSER’ site, a free online software available at https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER.

The residue index was also created by the ‘I-TASSER’ site, showing good stability (see Fig. 7, bottom right). PDB files generated by the ‘I-TASSER’ site were then opened using Swiss-PdbViewer for surface view (Fig. 7, left) and Ramachandran plot analysis (Fig. 7, top).

The tertiary structure of the protein vaccine is not an important matter for MHC epitopes, because the protein vaccine should be divided into epitopes in the immunoproteasome of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) cells, but it is desired that the adjuvants and B cell epitope are in the surface of protein molecule for docking with Toll-like receptors before entering the APCs in the periphery and affecting the B Cell receptors in lymph nodes. Predicted solvent accessibility suggested by the “I-TASSER” site indicates that the HP91 adjuvant has a good score, and B-cell epitopes have fairly good scores. Evaluating their positions in the third structure further confirms this.

Simulation of the immune response against a protein vaccine

To simulate the immune response, we utilized the “C-IMMSIM” site and its software93. Initially, we examined our protein vaccine and obtained results. Subsequently, for comparison purposes, we randomly altered the sequence of amino acids of epitopes to use as a control group and obtained results for the control group. The parameters used were as follows: Time step of injection: 1, what to inject: vaccine (no LPS), Adjuvant: 100, Number. Ag. to the injection: 1000. The reactions of immune system components against the control and vaccine are depicted in Fig. 8.

Simulation of immune system component responses to the designed protein vaccine (left column) and a control protein (right column). (A) Antibodies production, (B) Cytokines production, (C) Plasmablast population, and (D) T helper cell population. Created using the ‘C-IMMSIM’ site, free online software available at https://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM.

mRNA vaccine development and innovation

Briefly, the design of the mRNA vaccine achieved optimal parameters, including a CAI of 0.93, a GC content of 60.23%, and a CFD of 0%. Additionally, secondary structure predictions indicate that the mRNA can fold stably, with a minimum free energy of -395.04 kcal/mol.

Our innovative four-part vaccine strategy addresses the clinical challenge of balancing vaccine efficacy with safety monitoring. This is accomplished by dividing the epitopes into four separate vaccines, each targeting complementary protein combinations while preserving their therapeutic potential.

Optimization of mRNA vaccine

The length of our mRNA vaccine codon sequence (CDS) was 1056 nucleotides. The nucleic acid sequence of the mRNA vaccine is shown in Supplementary Material 2.

We employed the “GenScript” tools and calculated the CAI, which was estimated to be 0.93 (Fig. 9A). Since a CAI value exceeding 0.8 is considered acceptable, our result meets this criterion.

The optimal percentage of GC bases for efficient expression of the vaccine sequence in human cells should ideally fall within the range of 30–70%. After structure optimization, the average percentage of GC bases was calculated to be 60.23% (Fig. 9B).

Regarding CFD, a value of 0% was obtained (Fig. 9C). This indicates that rare consecutive codons, which can potentially reduce translation efficiency or halt translation altogether, were not present. Therefore, the result of CFD suggests that the codon usage does not impede translation efficiency or function.

ZBR01 mRNA vaccine stability and nucleic acid distribution parameters. (A) Codon Adaptation Index (CAI). (B) CG content. (C) Codon distribution frequency. Generated using GenSmart, a free online software available at https://www.genscript.com/gensmart-free-gene-codon-optimization.html.

Prediction of mRNA secondary structure

The RNAfold tool from the “ViennaRNA” package can be utilized to forecast the secondary structure of the mRNA vaccine102. This software utilizes the McCaskill algorithm to determine the predicted minimum free energy (MFE) of the secondary structure. The tool provides measurements for the minimum free energy (MFE) structure and the secondary structure of the center, along with their respective minimum free energy values. Additionally, the server evaluates the free energy of the structure. For input, we utilized the optimal codons of the structure. The findings indicate that the mRNA will be stable when it is formed with a minimum free energy (MFE) of -395.04 kcal/mol for the overall structure (Fig. 10A) and − 354.60 kcal/mol for the secondary center structure (Fig. 10B).

Secondary structure of mRNA vaccine ZBR01. (A) Minimum Free Energy (MFE) secondary structure. (B) Centroid secondary structure coloring based on base pairing probabilities. Created using the ‘ViennaRNA’ package, a free online software available at http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi.

Innovative four-part mRNA vaccine results

We divided the epitopes into four groups, as mentioned in the method section, to resolve the paradox of the effectiveness aspect vs. the clinical aspect. The first, the more epitopes that can be synthesized by the mRNA vaccine, the more effective the vaccine is, from a clinical aspect. In order to check safety and side effects more easily, the number of proteins targeted by the vaccine must be lowered. The result of dividing the epitopes into four groups is presented in Supplementary Table (1) in Supplementary Material 2. The methods mentioned above were used to design four mRNA vaccines. Their features are shown in Supplementary Table (2) in Supplementary Material 2. The secondary structures of these vaccines are shown in Fig. 11.

Secondary structures of four mRNA vaccines (ZBR11-14). Created using the ‘ViennaRNA’ package, a free online software available at http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi.

Discussion

Using the immune system or its components represents the ultimate solution for cancer treatment. Immune strategies can specifically target cancer cells. The adaptive immune system, developed for accurately identifying antigens and creating memory-based strong reactions against them, offers the best potential for precisely targeting cancer cells and avoiding damage to normal cells19,20. Among various methods, we focused on developing cancer vaccines and aimed to propose the best approach for their production and clinical utilization. Among several immunotherapy fields, we chose the cancer vaccine field, utilizing immunization against epitopes of cancer cell-specific or associated proteins, focusing on the MHC-I pathway, and designing multiepitope mRNA vaccines. A comprehensive understanding of tumor-associated antigens and their immunogenic potential is essential to creating effective immunotherapeutic strategies against TNBC. Our study applied reverse vaccinology and immunoinformatics approaches to design multi-epitope vaccines targeting proteins associated with TNBC. The reverse vaccinology approach has demonstrated remarkable success in vaccine development for various diseases, including infectious diseases and cancer. Recent studies have effectively utilized this methodology for cancer vaccine development against conditions such as oral cancer, KRAS-mutated cancers, and pancreatic cancer. Modern immunoinformatics tools’ computational efficiency and predictive accuracy enable the rapid identification of vaccine candidates, reducing development time and costs24,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110.

Our primary objective was to outline and execute the stages involved in designing an mRNA vaccine targeting cancer cell proteins, utilizing current bioinformatics capabilities. This process also included bioinformatics testing to model the properties of the designed protein vaccine and its corresponding mRNA. The methodology for designing the multi-epitope protein vaccine followed a framework that was utilized in previous in silico studies28,29,30. However, this study diverged in its objective, focusing on mobilizing the immune system to combat cancer instead of addressing a pathogenic infection. Recent advancements in bioinformatics and AI have transformed mRNA vaccine design, enabling systematic targeting of cancer-specific antigens while addressing scalability and personalization111,112,113,114. Through these analyses, we aimed to confirm the proper functionality of the vaccines theoretically. Additionally, our goal was to structure these stages to enable a bioinformatics system to perform these processes autonomously. Based on our study and the review of articles, we concluded that we should be able to follow a framework for automated development to bioinformatics-driven design of personalized mRNA cancer vaccines. Our framework consists of three computational design stages, supported by theoretical modeling and literature review111,112,113,114,115, as such a process is summarized in Table 8.

1- Selecting target proteins for each type of cancer. This selection should be based on how specific these proteins are in a particular tumor, how much they are expressed in the tumor, and the possibility of altered forms of the protein expressed in the tumor. The objective was to identify neoantigens that exhibit low cross-reactivity with healthy proteins of cells, thereby minimizing the associated risks of autoimmune responses111,112,113,116,117. It was also important to consider how we selected the target proteins. Given the vast number of these proteins, our team recommended creating a scoring protocol for selection.

Additionally, it was strongly recommended that the production of the cancer mRNA vaccine should be personalized and based on the protein produced by the tumor, as different tumor types might produce various proteins at different stages or even in other individuals, necessitating patient-specific biomarkers of patient and tumor genome analysis111.

2- Identifying epitopes in the target protein. In vaccine design, an epitope must be identified that could strongly bind to one of the MHC alleles (allele that codes MHC) of the MHC system, allowing it to be presented to T Cells. One less emphasized point in contemporary bioinformatics approaches in articles was that if the relevant epitope exists in the body’s proteins, the corresponding T-cell clone that reacts to the complex of that epitope and MHC has already been inactivated in the body during the tolerance process111,116. Therefore, it was necessary to target tumor-specific or altered proteins as much as possible, and the bioinformatics approach must be planned accordingly.

Ultimately, we might obtain numerous epitopes, and another computational approach was to find epitopes with maximum binding affinity to different alleles, meaning that if an epitope could strongly bind to two alleles, it was preferable to an epitope likely to bind strongly to one allele116. This consideration should also be included in the programming algorithm.

Another noteworthy point was that vaccines designed based on the binding of multiple epitopes to MHC system alleles should ideally be personalized, as specific individuals might lack these alleles, leading to variable results. Although multi-epitope vaccines enhanced this coverage, personalization still yielded better results116.

3- Designing mRNA capable of producing the epitopes within cells. The design must ensure maximum stability and high cell transcription efficiency in terms of the cap and other components. It should also easily enter the cell; fortunately, innovations in nano lipid coating have provided a significant advantage111,113.

After these three stages, the bioinformatics design of an mRNA vaccine is complete. We must design and produce a DNA template to proceed with its construction. After amplification in the in vitro transcription process, it could be used to produce mRNA.

Personalization of mRNA Vaccines was a noteworthy item. Perhaps one of the most important conclusions drawn from studying the design process of mRNA vaccines for cancer was that if an mRNA vaccine is specifically tailored for each individual with cancer (both for the person and the type and stage of cancer), it will undoubtedly be more effective. However, considering the complexity of the process, the cost of producing a personalized vaccine for each individual is significantly higher than designing a general vaccine for a population suffering from a specific type of cancer. Nevertheless, with technological advancements, these costs are continuously decreasing to the point where the added effectiveness of a personalized vaccine outweighs its production costs114,115,118,119.

Additional steps and costs in producing a personalized vaccine are summarized as follows:

1- Obtaining Necessary Information: While designing a vaccine for a specific geographical population with a particular type of cancer, we can rely on previously obtained data available in scientific databases or literature reviews. Producing a personalized vaccine requires genetic information from both the cancer cells and the affected individual at every stage of the disease114,117,120.

Obtaining a sample from the patient is relatively easy and can be done using a simple oral swab. The challenging and costly part is acquiring a sample of the cancer cells. Although the standard method involves biopsy through surgery for tumors and bone marrow sampling for hematologic malignancies, today, fine-needle biopsy and core needle biopsy under imaging guidance have emerged as a minimally invasive, cost-effective alternative, reducing complications and enabling repeated sampling during treatment monitoring. In certain cases, circulating tumor cells or tumor-derived DNA can be isolated from blood samples via liquid biopsy, which provides a non-invasive method to characterize tumor heterogeneity and guide therapy. In the future, the entire process may be performed robotically, reducing human error117,120,121,122,123,124.

The second costly step is genetic testing, which is continuously becoming less expensive while increasing in accuracy and the number of genes that can be analyzed. Currently, such tests are often conducted for many types of cancer, especially for targeted therapy purposes125.

Ultimately, this stage should yield outputs, including information about the patient’s proteins, identification of active proteins based on available databases, the individual’s MHC alleles, and tumor proteins and their expression by expression by mRNA study, and using pre-existing databases114,117,120.

2- Vaccine Design: The design process is currently expensive, but if all the required information is provided and a proper algorithm is developed, artificial intelligence (AI) can handle large datasets. This would reduce costs to nearly zero as the entire process is automated. By inputting the data generated in the first step, the mRNA vaccine is designed, and the corresponding DNA template is determined113,114,116.

-

3- Vaccine Production: In this stage, aside from the issue of production scale, which is inherently more expensive in personalized production vs. mass production, we also have the production of a DNA template specific to each individual114,119,122,123.

As mentioned, our approach integrates clinical insight with bioinformatics. Since each individual may have different cancer states at various stages and different MHC alleles, achieving complete coverage and efficacy across an entire population may not be possible. Therefore, while the current method of designing cancer vaccines is considered highly successful and is entering clinical trials, we ultimately need to advance toward producing personalized mRNA vaccines for cancer. The primary challenge today is the high cost of this process. Methods for HLA typing of individuals involved in cancer and liquid biopsies to obtain cancer cells are becoming more affordable. In addition, bioinformatics should enable the development of an AI-based program that can design personalized vaccines with minimal costs by utilizing information on the proteins expressed by the tumor and the patient’s MHCs. We aim to propose algorithms for selecting proteins and the optimal vaccine structures, allowing us to obtain the final DNA sequence for the in vitro transcription process. In the next phase, biotechnology experts must identify the least costly solution to create a personalized vaccine for each patient. Ultimately, it seems that with continuous technological advancements and automation of processes, costs will consistently decrease. In any case, the correct and effective form of the cancer mRNA vaccine is the personalized vaccine111,113,114,115,116,117,120,121,122,123,124.

On the other hand, we identified TLR4 as the primary pattern recognition receptor for vaccine adjuvant interaction, aligning with extensive literature emphasizing its critical role in cancer immunotherapy. TLR4 activation promotes dendritic cell maturation and enhances antigen presentation, promoting both innate and adaptive immune responses, and resulting in robust CD8 + T-cell responses substantial for anti-tumor immunity. The receptor’s ability to recognize DAMPs and PAMPs, alongside the dual signaling pathways of TLR4, including myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88)-dependent and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent pathways, through NF-κB, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and T-cell priming, activates comprehensive immune stimulation, making TLR4 an optimal target for vaccine adjuvant interaction. In the context of cancer vaccination, TLR4 agonists have demonstrated significant potential in clinical trials, with several compounds currently under evaluation for various cancer types23,126,127,128,129,130,131.

By incorporating multiple target proteins such as TROP-2, EpCAM, MUC1, NECTIN4, Folate Receptor α, Mesothelin, α-Lactalbumin, MAGE-A, and NY-ESO-1, we achieve comprehensive antigenic coverage against TNBC heterogeneity. This multi-target approach reduces the likelihood of immune evasion through antigen-loss variants, a common mechanism of cancer vaccine resistance. We adopt a conservative approach in selecting tumor-specific target proteins to align with our clinical goals. They should either be absent in healthy cells or lacking in those of the same age and gender. Additionally, we focus on proteins successfully targeted by other methods, ensuring their safety and avoiding aggregation during production due to their large size. A conservative clinical approach focuses on targeting tumor-specific proteins, ideally those not expressed in healthy cells of the same age and gender. We emphasize targeting proteins with established safety profiles from previous studies. The value of immunotherapy lies in specifically targeting cancer cells while sparing healthy ones. Additionally, attempting to target multiple epitopes is impractical due to challenges in assessing safety and efficacy in clinical studies, as well as the complexity of long mRNA sequences.

Our innovative four-part mRNA vaccine strategy addresses a fundamental challenge in cancer vaccine development: balancing epitope diversity for enhanced efficacy with maintaining clinical feasibility for safety evaluation. This approach enables the systematic assessment of individual vaccine components while preserving the overall therapeutic potential, thereby representing a novel contribution to cancer vaccine design methodology. Our design achieves high population coverage (87.75% for the Persian-Iranian population), demonstrating its broad applicability across diverse ethnic groups. This characteristic is crucial for developing globally applicable cancer vaccines that can benefit patients regardless of their genetic background. While our computational analysis provides strong evidence for vaccine efficacy, experimental validation in vitro and in vivo studies remain essential to confirm immunogenicity, safety, and translation to therapeutic potential, as one of our study’s limitations. Future studies should focus on evaluating vaccine-induced immune responses in relevant animal models and ultimately in clinical trials.

Like all scientific investigations, our study had certain limitations that deserved careful consideration. We had detailed these aspects and proposed specific strategies for future research to address them. The first limitation was our reliance on computational immuno-informatics. While these tools are effective in identifying and prioritizing candidate proteins and epitopes related to cancer antigens, they are predictive in nature and may not fully capture the biological complexities of the immune system. Subsequent research should focus on confirming these computational predictions using experimental approaches. This includes conducting in vitro assays, such as ELISPOT or flow cytometry-based T-cell activation analyses, to confirm the antigenicity and immunogenicity of the predicted epitopes. Additionally, in vivo validation using murine or patient-derived xenograft models of TNBC could provide insights into the actual immune response dynamics and antitumor efficacy. The integration of multi-omics datasets, including transcriptomic and proteomic profiles, will also help refine epitope prediction accuracy and enhance translational relevance. The second limitation concerned the exclusion of several proteins due to constraints associated with industrial and biosafety considerations during vaccine design. While this conservative selection ensured feasibility and safety in manufacturing, it might have restricted our exploration of potentially promising antigens. Future research could adopt a tiered evaluation approach by including these excluded proteins in preliminary in silico and in vitro phases, followed by safety and toxicity screenings. Incorporating scalable bioprocess modeling and assessing adjuvant compatibility could further aid in developing a broader range of vaccine candidates. The third limitation was related to the restricted scope of molecular docking analyses performed on epitopes and HLA molecules. To maintain focus and clarity, only representative epitopes were included in the docking simulations. Future computational analyses should expand these studies to encompass all predicted epitopes and a broader range of HLA alleles across diverse ethnic populations. Fourth, combining docking with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations could also provide insights into binding stability, flexibility, and solvent effects, enhancing robust predictions. Beyond these primary limitations, a few additional factors warrant acknowledgment. The fifth limitation involved the lack of peptide-MHC presentation validation using mass spectrometry, which could confirm whether the predicted epitopes are naturally processed and presented. The sixth limitation was that we did not fully explore cancer heterogeneity within TNBC, as different molecular subtypes may exhibit distinct antigenic landscapes. Future research should integrate patient-specific datasets and stratify analyses by subtype to improve individual-level predictions. Lastly, incorporating dynamic immune network modeling could simulate cell-cell interactions and cytokine responses, bridging computational predictions with systems-level immune behavior. By addressing these limitations through the integration of experimental and computational approaches, future investigations can enhance the robustness, translational accuracy, and clinical feasibility of epitope-based vaccine strategies in TNBC.

Ultimately, our team recommends embracing innovation. The more epitopes we incorporated into the vaccine design, the stronger the immune response we could achieve against the tumor. On the other hand, from a medical perspective, the more limited the intervention (In this case, the intervention meant the proteins against which we wanted to create immunity), the easier it became to assess its effects and potential side effects. Additionally, long mRNA sequences might encounter challenges in terms of calculating their 3D structure, stability, ease of production, and cellular delivery. As a solution, we proposed producing multiple vaccines, each consisting of a segment of a personalized multi-target (targeting more than one protein), multi-epitope, multi-class (MHC I, II) vaccine. So, we propose splitting and converting large multi-epitope constructs (19 epitopes in our design) into smaller modules, for instance, four separate five-epitope vaccines to be administered at intervals. With this innovation, we not only benefit from the advantage of immunization against a large number of epitopes, but we also obtain smaller vaccines with the capability to calculate properties, as well as better construction, handling, and penetration into cells, making it easier to examine their positive and negative effects on immunization against tumor proteins.

The results of this study were very encouraging for designing a vaccine against cancer. Selecting the target protein, finding the epitope, designing the protein vaccine, and evaluating it using many simulation software was successful. Finally, designing and evaluating the mRNA vaccine were successful, and we concluded that a personalized cancer mRNA vaccine should be considered the ultimate goal.

Conclusion

This study developed multi-epitope protein and mRNA vaccine candidates for TNBC using immunoinformatics and reverse vaccinology approaches, focusing on their translational potential. Computational analyses indicated favorable profiles for immunogenicity, structural integrity, and population coverage, providing a strong foundation for further validation. The identification of TLR4 as a potential interacting receptor, along with the proposed framework for a four-component mRNA vaccine, suggests innovative directions for rational vaccine design in TNBC. However, these findings are still predictive and need extensive experimental confirmation. Future in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies are essential to assess safety, efficacy, and feasibility before any therapeutic applications can be considered. Integrating computational tools into vaccine research can streamline the discovery process while ensuring rigor in the subsequent validation stages. Ultimately, personalized mRNA vaccines represent a promising avenue for improving treatment outcomes and survival rates for TNBC patients.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33 (2022).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Wynn, C. S. & Tang, S. C. Anti-HER2 therapy in metastatic breast cancer: many choices and future directions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 41, 193–209 (2022).

Mosele, F. et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in metastatic breast cancer with variable HER2 expression: the phase 2 DAISY trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2110–2120 (2023).

Caswell-Jin, J. L. et al. Analysis of breast cancer mortality in the US-1975 to 2019. JAMA 331, 233–241 (2024).

Atlanta, American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & & Figs (2024–2025). https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2024.pdf (2024).

Lu, B., Natarajan, E., Raghavendran, B., Markandan, U. D. & H. R. & Molecular Classification, Treatment, and genetic biomarkers in Triple-Negative breast cancer: A review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 22, 15330338221145246 (2023).

Howard, F. M. & Olopade, O. I. Epidemiology of Triple-Negative breast cancer: A review. Cancer J. 27, 8–16 (2021).

Vihervuori, H. et al. Varying outcomes of triple-negative breast cancer in different age groups–prognostic value of clinical features and proliferation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 196, 471–482 (2022).

Mahmoud, R., Ordóñez-Morán, P. & Allegrucci, C. Challenges for triple negative breast cancer treatment: defeating heterogeneity and cancer stemness. Cancers (Basel). 14, 4280 (2022).

Basmadjian, R. B. et al. The association between early-onset diagnosis and clinical outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 15, 1923 (2023).

Punie, K. et al. Unmet need for previously untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: a real-world study of patients diagnosed from 2011 to 2022 in the United States. Oncologist 30 (2025).

Mattar, A. et al. Overall survival and economic impact of Triple-Negative breast cancer in Brazilian public health care: A Real-World study. JCO Global Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO-24-00340 (2025).

Hsu, J. Y., Chang, C. J. & Cheng, J. S. Survival, treatment regimens and medical costs of women newly diagnosed with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 12, 729 (2022).

Chapdelaine, A. G. & Sun, G. Challenges and opportunities in developing targeted therapies for triple negative breast cancer. Biomolecules 13, 1207 (2023).

Fico, V. et al. Surgical complications of oncological treatments: A narrative review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 1056–1067 (2023).

Ribas, A. Adaptive immune resistance: how cancer protects from immune attack. Cancer Discov. 5, 915–919 (2015).

Reddy, S. M., Carroll, E. & Nanda, R. Atezolizumab for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 20, 151–158 (2020).

Rohaan, M. W., Wilgenhof, S. & Haanen, J. B. A. G. Adoptive cellular therapies: the current landscape. Virchows Arch. 474, 449–461 (2019).

Sengsayadeth, S., Savani, B. N., Oluwole, O. & Dholaria, B. Overview of approved CAR-T therapies, ongoing clinical trials, and its impact on clinical practice. EJHaem 3, 6–10 (2022).

Rando, H. M. et al. The Coming of Age of Nucleic Acid Vaccines during COVID-19. mSystems 8, e00928-22 (2023).

Pollard, A. J. & Bijker, E. M. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 83–100 (2021).

Oblak, A. & Jerala, R. Toll-Like Receptor 4 activation in cancer progression and therapy. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011, 609579 (2011).

Ramalingam, P. S. & Arumugam, S. Reverse vaccinology and immunoinformatics approaches to design multi-epitope based vaccine against oncogenic KRAS. Med. Oncol. 40, 283 (2023).

Zhang, L. Multi-epitope vaccines: a promising strategy against tumors and viral infections. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 15, 182–184 (2018).

Chao, P. et al. Pan-vaccinomics strategy for developing a universal multi-epitope vaccine against endocarditis-related pathogens. Front. Immunol. 16, 1524128 (2025).

Wittke, S., Baxmann, S., Fahlenkamp, D. & Kiessig, S. T. Tumor heterogeneity as a rationale for a multi-epitope approach in an autologous renal cell cancer tumor vaccine. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 523–537 (2016).

Basmenj, E. R. et al. Engineering and design of promising T-cell-based multi-epitope vaccine candidates against leishmaniasis. Sci. Rep. 13, 19421 (2023).

Koupaei, F. N. et al. Design of a multi-epitope vaccine candidate against vibrio cholerae. Sci. Rep. 15, 11033 (2025).

Alem, M. et al. Immuno-informatics voyage through molecular mimicry of heat shock proteins: potential IBD Immunopathogenesis. PLOS ONE. 20, e0333618 (2025).

Morisaki, T. et al. Lymph nodes as Anti-Tumor immunotherapeutic tools: Intranodal-Tumor-Specific Antigen-Pulsed dendritic cell vaccine immunotherapy. Cancers 14, 2438 (2022).

Song, K. & Pun, S. H. Design and evaluation of synthetic delivery formulations for Peptide-Based cancer vaccines. BME Front. 5, 0038 (2024).

Wilson, B. & Geetha, K. M. Lipid nanoparticles in the development of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 74, 103553 (2022).

Alameh, M. G. et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity 54, 2877–2892e7 (2021).

Lee, Y., Jeong, M., Park, J., Jung, H. & Lee, H. Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 2085–2096 (2023).

Deng, S. et al. Viral vector vaccine development and application during the COVID-19 pandemic. Microorganisms 10, 1450 (2022).

Khoshnood, S. et al. Viral vector and nucleic acid vaccines against COVID-19: A narrative review. Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022).

Hosseini, M. et al. Cancer vaccines for Triple-Negative breast cancer: A systematic review. Vaccines 11, 146 (2023).

Fitzgerald, K. A. & Kagan, J. C. Toll-like receptors and the control of immunity. Cell 180, 1044–1066 (2020).

Gote, V. et al. A comprehensive review of mRNA vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2700 (2023).

Shi, L. & Gu, H. Cell membrane-camouflaged liposomes and neopeptide-loaded liposomes with TLR agonist R848 provides a prime and boost strategy for efficient personalized cancer vaccine therapy. Nanomedicine 48, 102648 (2023).

Pisibon, C., Ouertani, A., Bertolotto, C., Ballotti, R. & Cheli, Y. Immune checkpoints in cancers: from signaling to the clinic. Cancers 13, 4573 (2021).

Srivastava, A. K., Guadagnin, G., Cappello, P. & Novelli, F. Post-Translational modifications in Tumor-Associated antigens as a platform for novel Immuno-Oncology therapies. Cancers 15, 138 (2023).

Nin, D. S. & Deng, L. W. Biology of cancer-Testis antigens and their therapeutic implications in cancer. Cells 12, 926 (2023).

Hayat, A. et al. Low HER2 expression in normal breast epithelium enables dedifferentiation and malignant transformation via chromatin opening. Dis. Model. Mech. 16, dmm049894 (2023).

Pavšič, M., Ilc, G., Vidmar, T., Plavec, J. & Lenarčič, B. The cytosolic tail of the tumor marker protein Trop2–a structural switch triggered by phosphorylation. Sci. Rep. 5, 10324 (2015).

McDougall, A. R. A., Tolcos, M., Hooper, S. B., Cole, T. J. & Wallace, M. J. Trop2: from development to disease. Dev. Dyn. 244, 99–109 (2015).

Kumar, S. et al. A candidate triple-negative breast cancer vaccine design by targeting clinically relevant cell surface markers: an integrated Immuno and bio-informatics approach. 3 Biotech. 12, 72 (2022).

Zaman, S., Jadid, H., Denson, A. C. & Gray, J. E. Targeting Trop-2 in solid tumors: future prospects. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 1781–1790 (2019).

Loibl, S. et al. Health-related quality of life in the phase III ASCENT trial of sacituzumab Govitecan versus standard chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 178, 23–33 (2023).

Pavšič, M. Trop2 forms a stable dimer with significant structural differences within the Membrane-Distal region as compared to EpCAM. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10640 (2021).

Landeros, N., Castillo, I. & Pérez-Castro, R. Preclinical and clinical trials of new treatment strategies targeting cancer stem cells in subtypes of breast cancer. Cells 12, 720 (2023).

Munz, M., Baeuerle, P. A. & Gires, O. The emerging role of EpCAM in cancer and stem cell signaling. Cancer Res. 69, 5627–5629 (2009).

Franken, A. et al. Comparative analysis of EpCAM high-expressing and low-expressing Circulating tumour cells with regard to their clonal relationship and clinical value. Br. J. Cancer. 128, 1742–1752 (2023).

Fang, W. et al. 737MO EpCAM-targeted CAR-T cell therapy in patients with advanced colorectal and gastric cancers. Ann. Oncol. 33, S880–S881 (2022).

Caizi, N., Shi, J. & Zhang, H. Vaccination therapy: an active approach towards Triple-Negative breast cancer. (Clausius Sci. Press. https://doi.org/10.23977/blsme.2022036 (2022).

Yamashita, N. & Kufe, D. Addiction of cancer stem cells to MUC1-C in Triple-Negative breast cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8219 (2022).

Kufe, D. W. MUC1-C oncoprotein as a target in breast Cancer; activation of signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 32, 1073–1081 (2013).

Yin, L. et al. Current progress in chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 162, 114648 (2023).

Bouleftour, W., Guillot, A. & Magne, N. The Anti-Nectin 4: A promising tumor cells Target. A systematic review. Mol. Cancer Ther. 21, 493–501 (2022).

Zeindler, J. et al. Nectin-4 expression is an independent prognostic biomarker and associated with better survival in Triple-Negative breast cancer. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 6, 200 (2019).

Powles, T. et al. Enfortumab Vedotin in previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl. J. Med. 384, 1125–1135 (2021).

Corti, C. et al. Future potential targets of antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. Breast 69, 312–322 (2023).

Zagorac, I., Lončar, B., Dmitrović, B., Kralik, K. & Kovačević, A. Correlation of folate receptor alpha expression with clinicopathological parameters and outcome in triple negative breast cancer. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 48, 151596 (2020).

Matulonis, U. A. et al. Efficacy and safety of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in patients with Platinum-Resistant ovarian cancer with high folate receptor alpha expression: results from the SORAYA study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 2436–2445 (2023).

Gajaria, P., Kadu, V., Patil, A., Desai, S. & Shet, T. Triple negative breast cancer: expression of folate receptor alpha in Indian population. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 49, 151598 (2020).

Spicer, J. et al. Safety and anti-tumour activity of the IgE antibody MOv18 in patients with advanced solid tumours expressing folate receptor-alpha: a phase I trial. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–11 (2023).

Faust, J. R., Hamill, D., Kolb, E. A., Gopalakrishnapillai, A. & Barwe, S. P. Mesothelin: an immunotherapeutic target beyond solid tumors. Cancers 14, 1550 (2022).