Abstract

A ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite was synthesized and evaluated as a visible-light-driven photocatalyst for the reduction of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)). Structural and spectroscopic analyses (XRD, FTIR, TEM, FESEM-EDS, TGA, BET, PL, UV–Vis DRS) confirmed the successful integration of CdS and g-C3N4 within the Al-fumarate MOF framework, leading to enhanced light absorption, interfacial contact, and charge-transfer properties. Under optimized conditions (pH 3, catalyst dosage 0.4 g L−1, initial Cr(VI) 20 mg L− 1), the nanocomposite achieved a Cr(VI) removal efficiency of 86.8%, outperforming the single and binary reference systems. Scavenger experiments and band-structure analysis indicated that the dominant pathway proceeds via a cascade S-scheme mechanism, where electrons migrate from g-C3N4 to Al-Fu MOF and then to VB of CdS. The preserved CdS electrons (in CB) serve as the dominant reductive species for Cr(VI) photoreduction. The composite also retained its photocatalytic activity over repeated cycles, demonstrating structural stability and reusability. These findings highlight CdS@MOF@C3N4 as a promising photocatalyst for Cr(VI) removal and provide mechanistic insight into charge-transfer processes in ternary heterojunctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

The escalating levels of environmental pollution are intrinsically linked to the surge in industrial activities worldwide. The drive for improved living standards has led to the proliferation of various industries, which in turn contribute to environmental degradation1. It is imperative that we adopt responsible environmental practices to mitigate the impacts of industrial waste on ecosystems. Central to enhancing global water quality is the imperative to prevent discharges of hazardous materials and to establish effective wastewater treatment protocols2. Heavy metals, particularly chromium in its hexavalent form (Cr(VI)), represent significant pollutants, presenting substantial risks due to their toxicity, persistence in the environment, and bioaccumulation potential. Cr(VI) contamination in aquatic systems is associated with serious health implications, including skin carcinogenesis, respiratory ailments, immunotoxicity, and genotoxic effects3,4.

Extensive research over recent decades has focused on remediating heavy metal pollution, with chromium being a primary contaminant of concern, given its ubiquity. Chromium exists in several oxidation states: Cr(0), Cr(III), and Cr(VI). While elemental chromium (Cr(0)) is utilized in alloy production, hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) is notable for its high solubility in water, contrasting with trivalent chromium (Cr(III)), which tends to precipitate as hydroxides under neutral pH conditions5,6. In aqueous solutions, Cr(VI) can exist as chromate (CrO42−) or hydrogen chromate (HCrO4−), both of which demonstrate greater mobility relative to Cr(III). The contamination of surface waters with Cr(VI) often arises from inadequate waste disposal at mining operations. This situation necessitates the development of cost-effective and efficient remediation techniques to lower Cr(VI) levels in impacted water bodies7 .

Potential strategies for mitigation include physical adsorption using porous materials and the chemical reduction of Cr(VI) to the less toxic Cr(III). Additionally, photocatalysis presents an innovative approach, leveraging solar energy to facilitate the transformation of hazardous contaminants into innocuous products while minimizing secondary pollution and energy demands8,9. The advancement of these remediation technologies is critical for safeguarding water quality and public health. The photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) utilizing semiconductor-based nanocomposites represents a crucial area of research, notable for its operational simplicity and efficiency. These nanocomposite materials can effectively harness both sunlight and artificial light for the reduction of hexavalent chromium, resulting in a process that is not only efficient but also cost-effective, as they are reusable with minimal additional investment10,11. The photoexcited surfaces of these semiconductor nanocomposites display enhanced hydrophilicity, which facilitates the oxidation of water, given that the negative potential of water (1.23 V) exceeds that of most semiconductor materials12. Simultaneously, the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) occurs at the conduction band of the semiconductor, since the redox potential of Cr(VI) is sufficiently positive in relation to the valence band potential of the employed semiconductors13. Researchers have developed nanocomposites that effectively absorb both the ultraviolet (UV) and visible light spectra, maximizing the utilization of direct solar radiation. Furthermore, when these nanocomposites are combined with layered materials, they promote superior electron transport, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of the Cr(VI) photoreduction processes14.

Photocatalysis faces significant challenges, primarily linked to (i) the limited effectiveness of solar irradiation due to the dominance of semiconductors that primarily absorb in the ultraviolet and near-visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, and (ii) the detrimental effects arising from the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole (e−-h+) pairs15,16. To tackle these issues, researchers have investigated several strategies to enhance light absorption. These include various doping methods, the integration of photo-sensitizers, and the development of heterojunction systems that combine the main photocatalyst with electron or hole acceptors17. These structural advancements aim to reduce recombination rates and enhance overall photocatalytic performance.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have gained significant attention as effective photocatalysts due to their exceptional crystallinity, tunable band gaps, adaptable porous structures, and high surface areas18. They are used in applications like gas adsorption, drug delivery, chemical sensing, and as heterogeneous catalysts19. MOFs exhibit photocatalytic activity through uncoordinated metal clusters, organic linkers that can harvest light, and internal cavities that can host photoactive materials20. However, issues like low electronic conductivity and rapid charge recombination have prompted researchers to integrate MOFs with conductive materials or semiconductors (e.g., g-C3N421, TiO222, WO323, CdS24, COFs25, MoS226) to enhance their performance and stability. The incorporation of secondary and ternary components into these composites not only improves the stability of MOF-based photocatalysts but also expands their scope of applications.

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) is a two-dimensional material recognized for its narrow bandgap of approximately 2.7 eV, which imparts notable photocatalytic capabilities27. This material exhibits exceptional thermal and physicochemical stability, alongside being non-toxic and easily storaged, with availability from diverse sources28. Recently, g-C3N4 has emerged as a favorable candidate for the fabrication of heterostructured materials in combination with wide bandgap semiconductors. However, g-C3N4 is limited by its relatively low surface area and the rapid recombination of photoinduced charge carriers. The formation of heterojunctions has shown significant potential in enhancing the separation of charge carriers, thereby improving the photocatalytic efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts29,30.

In this context, cadmium sulfide (CdS), a narrow bandgap semiconductor with a range of 2.2 to 2.5 eV, has been extensively utilized in photocatalytic applications due to its broad-spectrum visible light absorption. Nonetheless, the photocatalytic activity of CdS nanoparticles is often compromised by several factors, including their tendency to aggregate, which diminishes both specific surface area and electron-hole pair separation efficiency. Consequently, the development of heterogeneous semiconductor systems has become an increasingly popular strategy to bolster the photocatalytic performance of CdS nanoparticles31,32.

Recent advances in heterojunction engineering have highlighted the importance of the step-scheme (S-scheme) charge-transfer mechanism for preserving strong redox potentials while enhancing charge separation. In an S-scheme heterojunction, selective recombination removes low-energy carriers at the interface, keeping the highly reducing electrons and highly oxidizing holes in their respective parent semiconductors, thereby maintaining high photocatalytic activity under visible light. This design principle has been successfully applied across a range of systems, from quantum-dot-based S-scheme photocatalysts to COF- and MOF-derived architectures, leading to prolonged carrier lifetimes and improved performance in both pollutant removal and solar fuel production33,34. Recent representative reports include a comprehensive review on quantum dots in S-scheme photocatalysts, studies demonstrating ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) to prolong carrier lifetime in Ni-MOF S-scheme systems, and S-scheme MIL-101(Fe)/BiOCl architectures that significantly boost Cr(VI) removal35,36. Building upon these advances, recent reports have highlighted that tailoring interfacial electric fields within S-scheme heterojunctions can further boost charge separation and redox kinetics under visible light37. Moreover, controlled structural modification of g-C3N4, such as inter-plane crystallization and alkali-metal incorporation, has been shown to improve carrier mobility and overall photocatalytic efficiency38.

This study introduces a strategically engineered inorganic-organic ternary photocatalyst, CdS@MOF@C3N4, featuring a finely tuned band alignment and architecturally optimized interfacial coupling. In this architecture, g-C3N4 and CdS function as visible-light-active semiconductors, while the Al-fumarate MOF provides a porous scaffold and acts as an electron mediator. The intimate interfacial contact among these components is expected to favor directional charge migration and minimize recombination. Within such a ternary configuration, CdS can supply photogenerated electrons with high reduction potential, whereas g-C3N4 contributes strong oxidation capacity, thereby maintaining complementary redox functionalities under visible light. The incorporation of the Al-based MOF further enhances this cooperative effect by offering hierarchical porosity, abundant adsorption sites, and a redox-active coordination environment that can accumulate and shuttle charge carriers. This synergistic arrangement facilitates efficient electron transfer to adsorbed Cr(VI) ions and simultaneously stabilizes the semiconductor components against photocorrosion. By integrating CdS and g-C3N4 with an Al-fumarate MOF scaffold, we aim to construct a ternary cascade S-scheme heterojunction that (i) enhances visible-light absorption, (ii) promotes directionally selective charge migration, and (iii) preserves the high reduction potential of CdS electrons for efficient Cr(VI) photoreduction. Compared with binary systems, the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 is anticipated to deliver superior activity owing to its optimized band alignment, extended carrier lifetime, and the presence of multiple interfacial junctions that accelerate charge separation. Such rational heterostructure engineering underscores the potential of MOF-integrated nanocomposites as advanced photocatalysts for sustainable environmental detoxification under visible-light irradiation.

Experimental section

Synthesis of materials

Chemicals and synthesis protocols for CdS nanoparticles39, g-C3N4 nanosheets40, and aluminum fumarate MOF (Al-Fu MOF)41 were executed in accordance with established methods, with comprehensive details provided in the Supplementary Information (S1). The synthetic procedures for all materials are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1.

Synthesis of binary nanocomposite (MOF@C3N4)

To create the MOF@C3N4 binary nanocomposite42, 1.85 g of aluminum sulfate octadecahydrate (Al2(SO4)3·18H2O) was solubilized in 7 mL of deionized water. Subsequently, 0.06 g of g-C3N4 nanosheets was incorporated into the solution, followed by continuous stirring at 60 °C for 1 h to ensure homogenous dispersion. In a separate container, a mixture of 0.47 g of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 0.064 g of fumaric acid was prepared in 10 mL of deionized water, which was then incrementally added to the primary mixture while maintaining constant stirring. The reaction was sustained for an additional 2 h at a controlled temperature to facilitate the precipitation of a white solid. The resultant precipitate was collected via centrifugation, thoroughly washed multiple times with deionized water and ethanol to eliminate residual impurities, and subsequently dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 24 h, yielding the MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite.

Synthesis of ternary nanocomposite (CdS@MOF@C3N4)

The preparation of the CdS@MOF@C3N4 ternary nanocomposites34 involved the incorporation of varying masses of CdS nanoparticles into the established MOF@C3N4 binary matrix. In a standard procedure, 0.20 g of MOF@C3N4 was dispersed in 50 mL of deionized water and subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 1 h to ensure complete exfoliation and uniform homogenization. Concurrently, distinct quantities of CdS nanoparticles (0.10 g, 0.20 g, and 0.40 g) were each dispersed in 50 mL of deionized water and sonicated for 1 h. Following this, the MOF@C3N4 suspension was gradually integrated into the CdS dispersion while continuously stirring for 2 h to promote interaction. The resultant mixture underwent an additional hour of sonication to facilitate optimal contact among the components. The final precipitate was isolated via centrifugation, meticulously washed, and dried in an oven at 100 °C for 12 h to furnish the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposites.

Material characterization

The specimens were characterized morphologically using a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM: MIRA3 Tescan) integrated with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) for elemental analysis. Detailed structural characterization was performed via Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) using a Philips EM 208 S operating at 200 kV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained on a PHILIPS X’Pert Pro diffractometer, scanning the 2θ range of 5° to 70° with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TA Instruments SDT to assess thermal stability, ramping the temperature from 20 °C to 800 °C in an argon atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The functional groups present in the composites were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) on a BRUKER FTIR spectrometer, capturing spectra in transmission mode over the range of 4000 to 400 cm−1. Surface area measurements were carried out using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method by nitrogen adsorption-desorption on a BELSORP MINI II instrument. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) was performed with an S_4100 SCINCO spectrometer covering the wavelength range of 190–600 nm, employing BaSO4 as the reflectance standard. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded with a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm, while ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectra were measured using a UV-2601 spectrophotometer from Rayleigh.

Photoreduction experiments

The photoreduction of Cr(VI) was systematically studied by applying optimized catalyst quantities to Cr(VI) solutions of predetermined volume and concentration, utilizing a 100 mL beaker as the experimental setup. To establish adsorption equilibrium prior to light exposure, the suspensions were stirred in the dark for 30 min. Following this period, the samples were subjected to 1 h of illumination from a 200 W tungsten filament Philips lamp (λ > 400 nm) to facilitate photocatalytic reduction. Samples of 2 mL were periodically extracted during the illumination phase and subjected to centrifugation for solid-liquid separation. The reduction efficiency of Cr(VI) was quantitatively assessed using colorimetric analysis at 540 nm with a Shimadzu UV-Vis spectrophotometer, employing the diphenylcarbazide (DPC) method. The DPC reagent was prepared by dissolving 0.2 g of diphenylcarbazide in 50 mL of acetone, followed by the addition of 500 µL of concentrated sulfuric acid. The final volume was adjusted to 100 mL with deionized water. For optimal colorimetric response, the sample-DPC mixture was shaken for 30–60 s and allowed to stand for 30 min to ensure thorough color development43.

To ascertain the optimal conditions for Cr(VI) photoreduction, several parameters were evaluated, including catalyst dosages of 0.12, 0.4, and 0.7 g L−1, pH levels adjusted to 2, 3, and 4.5 with 0.1 M HCl, as well as Cr(VI) concentrations of 10, 20, and 30 mg L−1. The reusability of the synthesized photocatalysts was assessed through five successive catalytic cycles. Post-reaction, the catalyst was separated via centrifugation, washed multiple times with ethanol and ultrapure water, and dried at 60 °C for reuse. To elucidate the photocatalytic reaction pathways and pinpoint the key reactive species responsible for the degradation of inorganic pollutants, we conducted a series of systematic radical trapping experiments. To identify the key reactive species involved in the photocatalytic process, various scavengers were employed: silver nitrate (AgNO3), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and benzoquinone (BQ) all with mM concentration, to respectively deactivate electrons (e−)44, photogenerated holes (h+)45, hydroxyl radicals (•OH)46, and superoxide radicals (•O2−)47.

In each experimental setup, precise quantities of these scavengers were added to Cr-containing solutions in the presence of the photocatalyst. The mixtures were agitated thoroughly and left in the dark for 30 min to establish equilibrium conditions for radical-scavenger interactions. Following this incubation period, we initiated visible-light irradiation and collected aliquots at regular time intervals. The absorbance of each collected sample was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer to monitor the photocatalytic degradation process. The removal efficiency was calculated using:

where C0 and Ct denote the initial and time-dependent concentrations of Cr(VI) (mg L−1), respectively.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the nanostructures

The XRD patterns (Fig. 2a) provide critical insights into the crystallinity and phase purity of the materials examined. The patterns exhibit sharp, distinct peaks, indicative of a highly crystalline structure commonly associated with MOFs. Notably, the peak observed at approximately 8–10° 2θ aligns with the (011) plane of aluminum fumarate MOF, confirming the framework’s long-range order consistent with its expected crystallography. Aluminum fumarate MOFs, including variants like Al-MIL-53, typically display low-angle peaks due to their extensive unit cell dimensions and inherent porosity. Additional peaks in the range of 15–20° 2θ likely correspond to higher-order reflections (e.g., (020), (022) and (033)), further underscoring the periodicity of the crystalline framework. While the specific planes may vary depending on the polymorphic form of Al-Fu-MOF, the observed patterns adhere to established literature48.

The XRD pattern for g-C3N4 nanosheets reveals a prominent peak at 27–28° 2θ, attributed to the (002) plane. This peak signifies the interlayer stacking of graphitic layers, exhibiting a d-spacing of approximately 3.2–3.3 Å, which is characteristic of g-C3N4. Additionally, a weaker peak around 13° corresponds to the (100) plane, derived from the in-plane repeating units of the tri-s-triazine motif, indicative of structural ordering within the layers49. For CdS nanoparticles (JCPDS data 65-3414), the XRD analysis presents multiple sharp peaks that can be linked to either the wurtzite or cubic phases of CdS, contingent on the precise peak positions observed. A peak at roughly 25° 2θ, noted with a blue triangle, is likely associated with the (100) plane of the hexagonal wurtzite structure, which is prevalent for CdS nanoparticles. The peak in the 26–27° 2θ range can be assigned to the (002) plane of the wurtzite phase, potentially overlapping with the (111) plane of the cubic zinc blende phase, although wurtzite is the more typical phase encountered at this scale. Furthermore, peaks in the vicinity of 28–29° 2θ correlate with the (101) plane of the wurtzite phase, and additional peaks at approximately 43–45° and 50–52° 2θ correspond to the (110) and (112) planes of wurtzite, respectively, thus confirming the crystalline nature of the CdS nanoparticles50.

The XRD pattern of the binary nanocomposite showcases a blend of peaks from both the MOF and g-C3N4 components, retaining the prominent g-C3N4 peak at 2θ = 27–28° alongside observable MOF peaks. This suggests effective integration of the components, with the crystalline phases of the individual components largely preserved. However, the observed reduction in peak intensity may point to potential structural interactions between components. Finally, the XRD pattern of the ternary nanocomposite incorporates peaks from all three constituent materials (MOF, g-C3N4, and CdS). The presence of CdS peaks alongside those from the MOF and g-C3N4 confirms the successful integration of CdS within the ternary nanocomposite. Nonetheless, slight peak broadening or shifts may infer structural interactions or partial distortion of the crystalline lattices resulting from the composite’s formation.

The FTIR spectra provide comprehensive insights into the chemical bonding and functional groups present within the synthesized materials and their composites (Fig. 2b). For aluminum fumarate MOF (Al-Fu-MOF), the spectrum features a prominent absorption band between 1600 and 1700 cm−1, indicative of the C = O stretching vibration associated with the fumarate linker. This confirms the presence of the organic component embedded within the MOF framework. Additionally, vibrations in the 500–700 cm−1 range are linked to Al-O stretching and bending modes, affirming the coordination of aluminum ions with the oxygen atoms of the fumarate ligand, thereby validating the successful synthesis of the Al-Fu-MOF structure51. In the case of g-C3N4, characteristic spectral features are observed between 1200 and 1600 cm−1, notably at 1240 cm−1, 1320 cm−1, 1410 cm−1, and 1570 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibrations of C-N and C = N bonds within the tri-s-triazine units. These bands are representative of the graphitic layered architecture of g-C3N4. A broad absorption band observed in the range of 3000–3500 cm−1 is associated with N-H stretching from uncondensed amino groups and O-H stretching from adsorbed water, corroborating the presence of surface functional groups consistent with the expected structure of g-C3N452. For CdS, minimal vibrational activity is apparent in the mid-infrared spectrum, as is characteristic of a binary inorganic semiconductor, where Cd-S vibrations primarily manifest in the far-IR region (below 400 cm−1). However, minor bands noted between 600 and 800 cm− 1 may be attributed to surface hydroxyl groups (Cd-OH) or adsorbed contaminants such as water or carbonates. A subtle band observed around 1000–1100 cm− 1 suggests the presence of sulfate (SO₄2−) or sulfite (SO₃2−) impurities, likely formed during synthesis in the presence of sulfur precursors, indicating surface oxidation of CdS nanoparticles53. The broadband in the 3000–3500 cm− 1 region resembles that in g-C3N4, arising from O-H stretching due to adsorbed water, confirming surface moisture rather than intrinsic to the CdS structure. These findings align with the crystalline wurtzite or zinc blende phases of CdS, where the absence of significant mid-IR bands suggests structural purity, with minor peaks reflecting surface phenomena rather than bulk attributes.

For the MOF@C3N4 composite, the spectrum encompasses features from both parent materials. The 1600–1700 cm− 1 band reaffirms the C = O stretching of the MOF fumarate linker, while the 1200–1600 cm− 1 region (including peaks at 1240 cm− 1 and 1410 cm− 1) validates C-N and C = N stretching from g-C3N4, alongside Al-O vibrational contributions in the 500–700 cm− 1 range from the MOF framework. The broadband between 3000 and 3500 cm− 1 from g-C3N4 also indicates retention of its surface functional groups, confirming the successful hybridization of the MOF and g-C3N4 while preserving their chemical structures. Notably, slight intensity variations may indicate interfacial interactions. For the CdS@MOF@C3N4 composite, the spectrum integrates distinct bands from all three components. The validation of MOF’s C = O stretching is evident in the 1600–1700 cm− 1 region, with C-N and C = N stretching from g-C3N4 confirmed within 1200–1600 cm− 1 (notably at 1240 cm− 1 and 1410 cm− 1), coupled with Al-O vibrations from the MOF in the 500–700 cm− 1 range. The 3000–3500 cm− 1 band reflects N-H/O-H stretching from g-C3N4, while the weak bands at 1000–1100 cm− 1 and 600–800 cm− 1 indicating surface sulfate/sulfite and hydroxyl groups, respectively, confirm CdS incorporation into the ternary composite. The retention of these spectral features, potentially accompanied by slight shifts or broadening, suggests that the ternary composite maintains the structural and chemical integrity of its constituents, with interfacial interactions enhancing the material’s complexity.

The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms (Fig. 2c) and BJH (Barrett-Joyner-Halenda) pore size distribution profiles (Fig. 2d) yield critical insights into the textural characteristics, specifically surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, of the MOF@C3N4 binary composite and the CdS@MOF@C3N4 ternary composite. Analyzing the provided graphs sequentially from left to right includes the isotherms for MOF@C3N4 (BET), MOF@C3N4 (BJH), CdS@MOF@C3N4 (BET), and CdS@MOF@C3N4 (BJH). For the MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite, the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm displays a Type IV profile characterized by a distinct H3 hysteresis loop, typical of mesoporous materials. A pronounced uptake at low relative pressures (P/P0 < 0.1) indicates the presence of micropores, likely derived from the aluminum fumarate MOF framework. The observed hysteresis loop in the intermediate P/P0 range (0.4–0.9) corresponds to capillary condensation within the mesopores, attributed to the g-C3N4 component54. The BET surface area, estimated from the adsorption branch, is approximately 351.61 m2 g− 1 (Table 1), indicative of the high surface area typical for MOF-based composites, though diminished compared to pure Al-Fu MOF (1032.2 m2 g− 1), potentially due to partial pore blockage or coverage by g-C3N4. The BJH pore size distribution curve shows a peak around 4–5 nm, confirming the presence of mesopores along with a minor contribution from micropores (< 2 nm), consistent with the hierarchical porous structure resulting from the integration of the MOF and g-C3N4.

In the case of the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite, the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm similarly conforms to a Type IV profile with a H3 hysteresis loop, but with markedly reduced nitrogen uptake in comparison to the MOF@C3N composite. The initial uptake at low P/P0 (< 0.1) is less pronounced, indicating a reduction in microporosity, likely due to the incorporation of CdS nanoparticles, which may obstruct or fill some of the MOF pores. The hysteresis loop within the P/P0 range (0.4–0.9) suggests retention of mesopores but with a diminished adsorbed volume, implying a loss of accessible pore volume55,56. The BET surface area drops significantly to around 258.19 m2 g− 1, attributed to the dense nature of CdS occupying pore spaces within the MOF@C3N4 matrix. The BJH pore size distribution reveals a broader range with a peak around 10–12 nm, suggesting a transition toward larger mesopores, likely a result of CdS nanoparticle aggregation or structural modifications induced by their presence. Additionally, the presence of a tail extending up to larger pore sizes (up to 50 nm) points to macroporous contributions, likely arising from interparticle voids in the ternary composite. The hierarchical porosity evident in both composites highlights the successful integration of their constituent materials, with the ternary composite displaying more intricate pore architecture due to the inclusion of CdS nanoparticles.

The morphological characteristics of the as-prepared samples were comprehensively examined using FESEM. At the same time, the surface elemental composition was analyzed through EDS and elemental mapping (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3a, the pristine CdS nanoparticles exhibit a nearly spherical morphology with uniform distribution and particle sizes in the nanometer range. The g-C3N4 nanosheets (Fig. 3b) display a stacked and wrinkled sheet-like structure, typical of exfoliated carbon nitride, which facilitates intimate interfacial contact with other components. The Al-Fu-MOF sample (Fig. 3c) presents a porous and irregular framework with aggregated nanocrystals, consistent with the high surface area and porosity characteristic of MOF materials.

FESEM images illustrating the surface morphology of (a) CdS nanoparticles (500 nm), (b) g-C3N4 nanosheets (500 nm), (c) Al-Fu-MOF (500 nm), (d) MOF@C3N4 binary nanocomposite (200 nm), and (e) CdS@MOF@C3N4 ternary nanocomposite (500 nm). (f) Elemental mapping images showing the homogeneous spatial distribution of C, O, N, Cd, S, and Al elements, and (g) the corresponding EDS spectrum confirming the coexistence of these elements in the CdS@MOF@C3N4 heterostructure.

Upon compositing g-C3N4 with Al-Fu-MOF, the binary MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite (Fig. 3d) shows the sheet-like C3N4 layers intimately integrated with the MOF particles, indicating successful heterojunction formation. The ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite (Fig. 3e) reveals a more compact and roughened surface morphology, where CdS nanoparticles are uniformly distributed and well-anchored on the MOF@C3N4 matrix, suggesting a strong interfacial interaction among the three components.

The elemental mapping of CdS@MOF@C3N4 (Fig. 3f) further confirms the homogeneous spatial distribution of C, O, N, Cd, S, and Al elements across the composite surface. The corresponding EDS spectrum and quantitative data (Fig. 3g) verify the coexistence of these elements, consistent with the expected composition of the ternary heterostructure. These results collectively demonstrate the successful construction of a well-integrated CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite with uniform elemental dispersion, favorable for efficient charge transfer in photocatalytic processes.

TEM imaging of the synthesized materials is illustrated in Fig. 4. Panel 4a presents the CdS nanoparticles, characterized by dense, high-contrast domains that are distinctly separated from the surrounding matrix (scale bar: 100 nm). In Fig. 4b, we observe the MOF@C3N4 binary composite, where the lamellar morphology of g-C3N4 is clearly seen in proximity to the porous structure of the MOF (scale bar: 500 nm), indicating successful physical integration of the two components. Figure 4c and d depict the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 material, with scale bars of 500 nm and 1 μm, respectively. In these images, the CdS domains are anchored onto the MOF@C3N4 matrix and are distributed across the g-C3N4 sheets and MOF particles, resulting in a compact, hierarchical architecture that maximizes interfacial contact. Collectively, the TEM micrographs validate the heterogeneous yet well-integrated morphology of the ternary system and provide direct visual confirmation of the close interfacial coupling that facilitates enhanced charge transfer within the composite.

The optical characteristics and band gap energies of the synthesized photocatalysts were analyzed using DRS, as illustrated in Fig. 5a, b. To determine the band gap energy (Eg), we applied the Tauc-Mott approach, plotting (αhν)2 versus photon energy (hν), where α represents the absorption coefficient and A is a proportionality constant. This relationship is expressed in the equation (αhν)2 = A(hν − Eg)57 (see Fig. 5b). The band gap for the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite was measured at approximately 2.10 eV, indicating a reduction compared to the individual components and their binary combination: CdS (2.26 eV), Al-Fu-MOF (3.60 eV), g-C3N4 (2.75 eV), and MOF@C3N4 (2.85 eV). This pronounced narrowing of the band gap in the ternary system implies an enhanced capacity for visible-light absorption.

The synergistic incorporation of CdS nanoparticles, Al-Fu-MOF, and g-C3N4 into a unified heterostructure fosters improved electronic interactions at the interface, thereby facilitating more effective charge transfer and light harvesting. Additionally, the creation of multiple heterojunctions, along with the resultant textured surface morphology, likely enhances light scattering and reflection, contributing to increased photocatalytic efficacy under visible light. This strategic band gap modulation is closely linked to the superior photocatalytic performance observed in the reduction of Cr(VI) utilizing the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite.

PL spectroscopy was employed to evaluate the efficiency of photoinduced charge carrier separation and the recombination dynamics within the synthesized photocatalysts, as illustrated in Fig. 6a (λex = 350 nm, λem = 430–450 nm). The pristine g-C3N4 exhibits the highest PL emission intensity, reflecting a rapid recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, which limits its photocatalytic activity. Although Al-Fu-MOF exhibits a wide band gap (3.60 eV) that prevents photoexcitation under visible light, a weak PL emission is still observed under UV excitation (λex = 350 nm), which can be attributed to LMCT or defect-related emission centers within the MOF framework. Upon coupling with Al-Fu-MOF, the PL intensity decreases noticeably in the MOF@C3N4 binary composite, indicating that the MOF framework effectively facilitates electron extraction from g-C3N4 and thus suppresses radiative recombination. This improvement demonstrates that Al-Fu-MOF provides additional charge-transfer channels and enhances carrier mobility through its porous and conductive network.

The incorporation of CdS into the MOF@C3N4 structure leads to a remarkable further quenching of the PL emission, confirming a much more efficient separation of photoinduced charge carriers and a substantial suppression of radiative recombination. This pronounced decrease in PL intensity evidences the formation of a cascade S-scheme heterojunction, in which the Al-Fu-MOF serves as an interfacial charge mediator that facilitates directional electron transfer between CdS and g-C3N4. Within this configuration, low-energy carriers undergo selective interfacial recombination inside the MOF bridge, while highly reducing electrons in the conduction band of CdS and strongly oxidizing holes in the valence band of g-C3N4 are preserved. Such spatial separation of high-energy electrons and holes across multiple junctions strengthens the built-in electric field, reduces the probability of charge recombination, and ultimately enhances the photocatalytic efficiency of the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 system58.

The progressive PL quenching from g-C3N4 to MOF@C3N4 and finally to CdS@MOF@C3N4 highlights the stepwise enhancement of charge separation and the key role of CdS in completing the cascade S-scheme architecture. The Al-Fu-MOF acts as an effective electron mediator, ensuring directional charge flow and stable interfacial contact among all components. These findings confirm the synergistic interaction between the three semiconductors and validate the efficient photophysical functionality of the designed heterojunction system59.

The thermal decomposition behavior of the synthesized nanocomposites was systematically examined using TGA, and the results are presented in Fig. 6b. The binary MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite exhibited four distinct weight loss stages. The initial weight loss of approximately 14.27% observed below 100 °C corresponds to the removal of physically adsorbed moisture and trapped volatile species within the porous MOF matrix. The subsequent minor weight loss of 2.12% in the range of 100–150 °C is attributed to the desorption of loosely bound solvents or weakly coordinated molecules. A third stage, between 240 and 340 °C, accounting for ~ 3.35% mass loss, likely arises from the partial decomposition of organic moieties, such as linker fragments in Al-Fu-MOF and residual functional groups in g-C3N4. The final and most significant degradation (~ 54.71%) occurred between 380 and 800 °C, associated with the collapse of the MOF framework and the thermal decomposition of g-C3N4, which typically degrades at elevated temperatures above 500°C60,61.

In contrast, the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite showed markedly enhanced thermal stability, as evidenced by a substantially lower total mass loss and a simplified degradation profile. Specifically, the total weight loss was limited to 23.55%, with only 7.25% occurring below 100 °C and a dominant stage of ~ 16.0% between 400 and 800 °C. This represents a 50.89% improvement in thermal resistance compared to the binary composite. The enhanced stability is primarily attributed to the incorporation of CdS nanoparticles, which play multiple stabilizing roles within the composite structure.

CdS, as a thermally robust II-VI semiconductor, exhibits high resistance to decomposition under inert or oxidative atmospheres at temperatures typically beyond 600°C62. When integrated into the MOF@C3N4 matrix, CdS nanoparticles promote strong interfacial interactions through electrostatic and possibly covalent bonding with both the g-C3N4 layers and the MOF framework. These interactions likely restrict the mobility of organic ligands and polymeric domains, delaying the onset of thermal degradation. Furthermore, CdS may act as a structural stabilizer or a nanoconfinement center, limiting the evolution of gaseous degradation products and impeding the thermal collapse of the porous framework63.

Such stabilization mechanisms are consistent with previous reports indicating that semiconductor nanoparticles can suppress thermal degradation by acting as thermal sinks and enhancing the rigidity of hybrid composites64,65. Therefore, the observed improvement in the thermal profile of CdS@MOF@C3N4 not only confirms the successful integration of CdS but also highlights its critical role in improving the structural integrity and thermal durability of the ternary nanocomposite.

Photocatalytic studies on Cr(VI) reduction

Structural optimization of the ternary photocatalyst

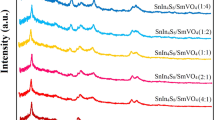

The rational design and compositional engineering of the MOF@C3N4 and CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposites were systematically explored to optimize photocatalytic performance under visible light (Table 2; Fig. 7). Initial efforts focused on the fabrication of a binary heterostructure comprising Al-Fu MOF and g-C3N4, aiming to exploit the high surface area and porosity of the MOF phase alongside the visible-light absorption capability and moderate conduction band position of g-C3N4. The enhancement in Cr(VI) photoreduction efficiency with increasing g-C3N4 content, from 13.02% at 1:1 to 25.39% at 1:3 mass ratio, can be attributed to improved interfacial contact, which facilitates vectorial charge transfer, and a greater density of photoactive surface sites. BET analysis corroborated this optimization, revealing a surface area of 351.61 m2 g− 1 and a mesoporous framework with dominant pore diameters around 4–5 nm, characteristic of hierarchical porosity, favoring both adsorption and reactant diffusion.

Nonetheless, the binary system exhibited limited charge separation efficiency, as evidenced by the strong PL intensity, implying a high rate of electron–hole recombination. Moreover, the bandgap of the MOF@C3N4 composite (~ 2.85 eV) restricted the effective utilization of the visible spectrum, imposing a fundamental constraint on photocatalytic efficiency.

To circumvent these intrinsic limitations, CdS nanoparticles were integrated into the binary framework to form a ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 composite. This strategic incorporation resulted in a multifold enhancement in photocatalytic activity, with the optimized sample (CdS: MOF@C3N4 = 2: 1/3) achieving a Cr(VI) removal efficiency of 86.79%, a more than threefold increase over the best-performing binary counterpart. The observed performance enhancement arises from a confluence of structural, optical, and electronic factors.

Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms revealed a reduction in surface area (to 258.19 m2 g− 1) and total pore volume (0.19 cm3 g− 1) in the ternary composite, suggesting partial pore filling by CdS nanoparticles. Yet, the shift in BJH pore distribution towards larger mesopores (~ 10–12 nm) and the emergence of macroporous features indicate the development of a more complex hierarchical network, which may facilitate enhanced photon scattering, accelerated mass transfer, and greater accessibility of active sites.

Optical characterization further substantiated the favorable modulation of the electronic structure. The introduction of CdS led to a noticeable bandgap narrowing to ~ 2.10 eV, significantly improving the absorption profile across the visible region. This modulation is indicative of strong interfacial coupling between CdS, g-C3N4, and the MOF phase, enabling extended light harvesting and more effective excitation of charge carriers.

PL spectroscopy provided critical insight into carrier dynamics. The ternary composite displayed marked emission quenching compared to the binary system, implying more efficient charge separation and suppressed radiative recombination. This behavior reflects the formation of energetically aligned heterojunctions that promote directional migration of photogenerated electrons, enhance the internal electric field, and prolong carrier lifetime, factors essential for facilitating redox reactions at the solid–liquid interface.

Collectively, these results highlight the efficacy of compositional tuning and heterojunction engineering in tailoring the electronic landscape, surface morphology, and optical absorption characteristics of the photocatalyst. The synergistic integration of CdS, MOF, and g-C3N4 into a structurally and electronically coherent ternary framework enabled a transformative enhancement in photocatalytic performance, positioning CdS@MOF@C3N4 as a promising platform for advanced Cr(VI) remediation under visible irradiation.

Effect of operational parameters on the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI)

Effect of pH

The pH of the solution is a critical factor in the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI). It strongly influences both the surface charge of the catalyst and the speciation of chromium in solution. As shown in Fig. 8a, the effect of pH on the photocatalytic performance was examined at three values: 2.0, 3.0, and 4.5.

At alkaline pH, the dominant species is CrO42−, which originates from the deprotonation of dichromate (Cr2O72−). Compared with dichromate, chromate ions have a higher redox potential. They also show weaker electrostatic affinity toward the catalyst surface, which diminishes their reducibility to Cr(III). Moreover, the catalyst surface becomes negatively charged in alkaline conditions. This causes electrostatic repulsion with the negatively charged chromate species. The concurrent precipitation of Cr(OH)3 further complicates the reduction pathway. These combined effects account for the significantly lower photocatalytic activity observed in alkaline environment66,67. Under highly acidic conditions (pH ≈ 2.0), the catalyst surface becomes strongly protonated, carrying an excessive positive charge. This not only restricts the effective interaction with Cr(VI) species but also destabilizes surface functional groups, which can impair catalytic activity. In addition, a high level of adsorption in the dark was observed at this pH, meaning that although chromium binds strongly to the catalyst surface, its photocatalytic reduction efficiency is limited. Strongly acidic conditions may also promote surface degradation or partial leaching of active components, further reducing long-term performance. These factors explain why pH 2.0 does not yield effective photocatalytic reduction despite the abundance of protons68.

In contrast, at pH 3.0, the system achieved the most favorable performance, with a removal efficiency of 79.86%. This improvement arises from a balance between sufficient proton availability, stable surface interactions, and the absence of severe surface degradation. Protons (H⁺) play a key role in facilitating electron transfer during the reduction of Cr(VI) to the less toxic Cr(III), while the surface of the catalyst remains stable and active under these conditions. Therefore, pH 3.0 was identified as the optimal condition for the photocatalytic process. By comparison, at pH 4.5, the removal efficiency decreased markedly to 39.46%, mainly due to the reduced proton concentration and altered chromium speciation, which weakened the driving force for the reduction reaction. Thus, it is evident that near-neutral conditions significantly diminish the overall efficiency of the process.

The pH-dependent reduction pathways can be described by the following reactions69:

Acidic conditions (pH < 3):

High proton concentrations accelerate the reduction of Cr2O72− to Cr3+, highlighting the role of H + ions in promoting the reaction.

Near-neutral conditions (pH ≈ 6–7):

Here, the lower concentration of protons slows the reduction rate, leading to decreased efficiency.

Alkaline conditions (pH > 7):

In alkaline media, the precipitation of Cr(OH)3 interrupts the reduction process and suppresses overall efficiency.

Effect of operational parameters on the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI): (a) solution pH; (b) catalyst dosage; (c) initial Cr(VI) concentration plus (d) time-dependent UV-Vis absorption spectra of Cr(VI) solution under optimized conditions (pH 3, 0.4 g L− 1 catalyst dosage, 20 mg L− 1 initial Cr(VI)).

Effect of CdS@MOF@C3N4 photocatalyst dosage

The concentration of the photocatalyst plays a pivotal role in determining the overall efficiency of photocatalytic processes. As illustrated in Fig. 8b, an initial increase in catalyst dosage enhances the available active surface area and promotes the generation of electron-hole pairs, which in turn significantly accelerates the reaction rate and improves the overall process performance. However, beyond the optimum dosage, further increases in catalyst concentration exert detrimental effects on the system. Although a higher catalyst loading provides additional active sites for charge carrier generation and the subsequent formation of reactive species, the excessive accumulation of particles leads to enhanced scattering and reflection of incident light. This phenomenon reduces the effective penetration of photons to the catalyst surface, thereby hindering the photocatalytic efficiency. Conversely, when the catalyst dosage is lower than the optimum level, the available active surface area is insufficient to sustain the reaction effectively, resulting in reduced removal efficiency70,71. Thus, establishing and maintaining the optimum catalyst concentration is critical for maximizing efficiency while avoiding unnecessary resource consumption.

Effect of initial Cr(VI) concentration

The efficiency of photocatalytic processes in pollutant removal is strongly influenced by the initial pollutant concentration as well as operational parameters. As shown in Fig. 8c, experiments conducted with initial Cr(VI) concentrations ranging from 10 to 30 mg L−1 demonstrated a pronounced decline in photocatalytic efficiency: from over 91.2% at 10 mg L− 1 to approximately 67.3% at 30 mg L− 1. This decrease in performance at higher concentrations can be attributed to critical threshold effects, where phenomena such as light attenuation and blockage of active sites on the catalyst surface become dominant. At elevated concentrations, pollutant molecules absorb and scatter incident photons, thereby reducing the effective photon flux reaching the catalyst surface. Consequently, the rate of photochemical reactions diminishes, surface interactions are hindered, and the overall stability of the photocatalytic system is compromised72.

Among the tested concentrations, 10 and 20 mg L−1 exhibited relatively high photocatalytic removal efficiencies. However, a key distinction was observed: at 10 mg L−1, dark adsorption accounted for nearly 27.07%, indicating a smaller contribution from true photocatalytic activity. In contrast, at 20 mg L−1, dark adsorption dropped to around 10%, highlighting the more significant role of visible-light-driven photocatalysis. This suggests that increasing the pollutant concentration to an optimum level enhances the interaction of Cr(VI) species with the illuminated catalyst surface, thereby accelerating the reaction rate and improving efficiency.

Therefore, the primary objective in achieving high photocatalytic performance under visible light is not to maximize dark adsorption, but rather to ensure the effective utilization of incident photons. Based on these findings, an initial Cr(VI) concentration of 20 mg L−1 was identified as the optimum value for subsequent experiments. Precise adjustment and control of pollutant concentration thus play a pivotal role in optimizing photocatalytic performance, leading to enhanced efficiency, reduced reaction time, and improved system stability in photocatalytic water treatment applications. The time-dependent UV-Vis absorption spectra recorded under these optimized conditions (pH 3, catalyst dosage 0.4 g L− 1, initial Cr(VI) concentration 20 mg L−1) further confirmed the efficient reduction of Cr(VI) species, as illustrated in Fig. 8d. The gradual decrease of the characteristic absorption band at 540 nm evidences the progressive conversion of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) during visible-light irradiation.

Role of scavengers in the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) by CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite

To investigate the functional role of reactive species in the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI), a series of carefully controlled experiments were conducted under optimized conditions (pH = 3, catalyst dosage = 0.4 g L−1, initial Cr(VI) concentration = 20 mg L−1). The experimental setup included the use of various electron and reactive species scavengers: AgNO3 served as an e− scavenger, EDTA targeted h+, DMSO quenched •OH, and BQ mitigated •O[2−73.

As illustrated in Fig. 9a, the introduction of AgNO3 led to a pronounced suppression of photocatalytic activity and a substantial decline in Cr(VI) removal efficiency. This effect arises because Ag+ ions readily capture photoinduced electrons and are reduced to metallic Ag0, thereby preventing these electrons from participating in the reduction of Cr(VI)74. Such a sharp decrease clearly underscores the dominant role of photoexcited electrons in the overall reduction mechanism. In contrast, the addition of DMSO, EDTA, and BQ, employed as scavengers for •OH, h+, and •O2− respectively, caused only marginal reductions in activity. This outcome highlights the limited involvement of these reactive intermediates in the reduction pathway. The relatively minor role of •O2− can be attributed to its low stability under acidic conditions (pH = 3), while •OH radicals and photogenerated holes, being strong oxidants, are inherently less relevant to the electron-driven reduction of Cr(VI). Collectively, these observations strongly support the conclusion that the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) is predominantly governed by direct electron transfer, with conductive nanomaterials serving as efficient platforms for electron migration and delivery to Cr(VI) species.

Stability and reusability of the synthesized photocatalyst

The photostability of the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite was rigorously assessed over five consecutive photocatalytic cycles (Fig. 9b). Each cycle represents the average of three independent repetitions, as summarized in Table S1 (part S3). The findings indicate that the nanocomposite exhibits a high degree of stability, demonstrating only a marginal reduction in photocatalytic efficiency relative to the initial cycle. This slight decline underscores the material’s robust resistance to repeated usage, affirming its viability for extended applications in wastewater treatment, particularly in the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III). During each cycle, the photocatalyst was subjected to centrifugation for recovery, followed by thorough washing with deionized water and ethanol, and then dried before reuse. After five successive cycles, the removal efficiency stabilized at approximately 63.09%, revealing only minimal activity loss. The observed performance degradation is likely attributable to a decrease in the availability of active photocatalytic sites following repeated reactions or to minor material losses encountered during the recovery and washing processes75. Overall, the consistent efficacy throughout multiple cycles provides substantial evidence of the structural integrity and reusability of the ternary composite. This durability is crucial for practical photocatalytic applications, significantly enhancing both the economic viability and environmental sustainability of deploying the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite in large-scale water treatment operations.

Stability assessment of the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite under acidic conditions

To assess the structural stability of the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite in acidic conditions, we conducted photocatalytic experiments optimized for the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) at pH 3. Following these experiments, XRD analysis was employed to evaluate the integrity of the nanocomposite structure under these conditions. The diffraction patterns indicated that while the peak positions remained constant, there were minor fluctuations in peak intensities. These variations can be linked to subtle changes in particle size or crystallinity; however, the lack of peak shifts signifies that the crystalline structure and existing phases of the composite were thoroughly maintained. This evidence supports that the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite demonstrates robust structural stability in strongly acidic media. Such durability is critical as it ensures that the physical and chemical properties of the photocatalyst are preserved during repeated photocatalytic cycles across diverse environmental settings, thus sustaining its catalytic efficacy. Figure S1 presents the stability profile of the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite in both acidic and non-acidic environments.

Proposed photocatalytic reduction mechanism of Cr(VI) over CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite under visible light irradiation

The photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) over the CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite can be best interpreted through a cascade S-scheme charge-transfer mechanism, in which the Al-Fu-MOF serves as a non-photoactive but electronically conductive mediator between CdS and g-C3N4. In this configuration, the MOF acts as a charge-transfer bridge that facilitates selective interfacial recombination and promotes efficient separation of photogenerated carriers, rather than contributing directly to light absorption. The Mott-Schottky analysis (Fig. 10) revealed flat-band potentials of − 1.12 V, − 1.28 V, and − 0.77 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for CdS, g-C3N4, and Al-Fu-MOF, respectively, corresponding to − 0.92, − 1.08, and − 0.57 V vs. NHE. Considering the characteristic 0.10 V difference between the flat-band and conduction-band potentials for n-type semiconductors, the conduction and valence band edges are estimated as CdS (− 1.02 / +1.24 V), g-C3N4 (− 1.18 / +1.57 V), and Al-Fu-MOF (− 0.67 / +2.93 V). These band-edge values, combined with the UV–Vis DRS-derived band gaps, establish a staggered energy alignment that drives directed charge migration and stepwise recombination under visible-light irradiation76.

Notably, the Mott-Schottky curve of the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 composite exhibited an almost flat response with large apparent 1/C2 values. This flattening arises from the combined capacitances of multiple interfacial junctions and indicates strong Fermi-level equilibration among the three components. Such behavior confirms the formation of an electronically coupled architecture consistent with the cascade S-scheme model. Upon visible-light illumination, CdS and g-C3N4 are photoexcited to produce electron-hole pairs, while the wide-band-gap MOF remains optically inactive but electronically engaged in charge mediation. Within this cascade S-scheme configuration, electrons from the conduction band of g-C3N4 migrate to the conduction band of the MOF and recombine with holes in the valence band of CdS, while holes remain primarily in the valence band of g-C3N4 for oxidation, as depicted in Fig. 11. These selective interfacial transfers annihilate low-energy carriers while preserving high-energy electrons in the conduction band of CdS and strongly oxidizing holes in the valence band of g-C3N477.

As a result, CdS provides highly reducing electrons (ECB = − 1.02 V vs. NHE) capable of converting Cr(VI) to Cr(III) (E⁰ = +0.51 V vs. NHE) through multielectron reduction pathways, while g-C3N4 supplies deep holes (EVB = + 1.57 V) that oxidize water or surface hydroxyls to •OH radicals (H2O + h+ → •OH + H+), maintaining charge neutrality and preventing carrier accumulation. This spatial charge separation and preservation of strong redox potentials synergistically enhance photocatalytic efficiency and stability, particularly mitigating CdS photocorrosion under continuous illumination. The combined optical, electrochemical, and photophysical results, including UV–Vis, Mott–Schottky, and PL quenching, collectively substantiate this cascade S-scheme mechanism, in which the Al-Fu-MOF operates as an interfacial “electronic fuse” that regulates charge flow, ensures Fermi-level alignment, and sustains efficient photoreduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) under visible light.

The band alignment dictates a cascade charge migration. Electrons photogenerated in the CB of g-C3N4 migrate into the CB of the MOF and subsequently transfer into the VB of CdS, where they recombine with CdS holes. This selective recombination eliminates carriers with insufficient redox potential and is the hallmark of the cascade S-scheme process. Meanwhile, holes photogenerated in the VB of g-C3N4 remain there and participate in oxidation reactions. As a result, highly reducing electrons are preserved in the CB of CdS, and strongly oxidizing holes remain in the VB of g-C3N4. These mechanistic deductions are further validated by the radical-trapping experiments. The addition of AgNO3, a well-known electron scavenger, markedly suppressed the photocatalytic reduction efficiency, confirming that photogenerated electrons in the conduction band of CdS are the dominant reducing species for Cr(VI) conversion. In contrast, the presence of benzoquinone (•O2− scavenger), isopropanol (•OH scavenger), and ammonium oxalate (h+ scavenger) produced only minor effects on the reaction rate, indicating that reactive oxygen species and holes play negligible roles in the reduction pathway. These observations strongly support the proposed cascade S-scheme mechanism, in which Cr(VI) reduction proceeds primarily via direct interfacial electron transfer from CdS through the MOF bridge to the adsorbed Cr(VI) species. The photocatalytic performance of the synthesized material for Cr(VI) removal under visible light was evaluated and compared with reported photocatalysts (Table 3).

Kinetic study of photocatalytic Cr(VI) reduction under visible light

The photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) over heterogeneous semiconductors is frequently analyzed using kinetic models to gain insights into the reaction mechanism and rate-limiting steps. Two common models are the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) equations. The pseudo-first-order model assumes that the rate is directly proportional to the concentration of the reactant and is expressed as83:

Where C0 and Ct represent the initial and time-dependent concentrations of Cr(VI), respectively, and k1 is the apparent rate constant. In contrast, the pseudo-second-order model assumes that the rate depends on the square of the concentration, and the integrated form can be written as:

Where k2 is the pseudo-second-order constant. By fitting the experimental data to both models, the adequacy of each kinetic description can be evaluated from the correlation coefficients (R²) and the linearity of the plots. In the present work, the reduction of Cr(VI) under visible light irradiation over the optimized CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite was examined using both models (Fig. 12).

The linear plots of ln(C0/Ct) versus time showed an excellent correlation (R2 = 0.96), whereas the pseudo-second-order fitting provided comparatively weaker agreement, indicating that the photoreduction process follows pseudo-first-order kinetics. The calculated apparent rate constant k1 confirms the rapid and efficient reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) under visible-light irradiation. This observation suggests that the process is primarily controlled by surface photogenerated charge transfer rather than by adsorption-driven interactions, which is in good agreement with the proposed cascade S-scheme charge-transfer pathway in the ternary heterostructure. The enhanced kinetics are thus attributed to efficient electron-hole separation, the strong reductive capacity of electrons retained in the CdS conduction band, and the synergistic mediation of MOF and g-C3N4 domains. Comparable findings have been documented in recent publications. For instance, Tian et al. explored the photocatalytic removal of hexavalent chromium using g-C3N4/MoS2 nanocomposites under visible light irradiation. They reported that the reaction kinetics fit well to a pseudo-first-order model, pointing toward efficient charge separation and visible-light absorption in the binary heterojunction system76.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the ternary CdS@MOF@C3N4 nanocomposite exhibits improved photocatalytic performance for Cr(VI) reduction compared with its binary and single-component counterparts. The enhanced efficiency is attributed to broadened light absorption, efficient interfacial charge migration, and suppressed electron–hole recombination enabled by the MOF-mediated cascade S-scheme heterojunction. Mechanistic analysis confirmed that electrons preserved in the CdS conduction band serve as the main reductive species for converting Cr(VI) to Cr(III), while the material maintained activity and stability over repeated cycles. Overall, the work provides a reliable basis for further development of ternary photocatalysts for heavy-metal remediation and contributes to a better understanding of charge-transfer dynamics in hybrid systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Saxena, V. Water quality, air pollution, and climate change: investigating the environmental impacts of industrialization and urbanization. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 236, 73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-024-07702-4 (2025).

Adesina, O. B., William, C. & Oke, E. I. Evolution in water treatment: exploring traditional self-purification methods and emerging technologies for drinking water and wastewater treatment: A review. World News Nat. Sci. 53, 169–185 (2024).

Sharma, P., Singh, S. P., Parakh, S. K. & Tong, Y. W. Health hazards of hexavalent chromium (Cr (VI)) and its microbial reduction. Bioengineered 13, 4923–4938. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2022.2037273 (2022).

Bucurica, I. A., Dulama, I. D., Radulescu, C., Banica, A. L. & Stanescu, S. G. Heavy metals and associated risks of wild edible mushrooms consumption: transfer factor, carcinogenic risk, and health risk index. J. Fungi. 10, 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10120844 (2024).

Hossini, H. et al. A comprehensive review on human health effects of chromium: insights on induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 70686–70705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-22705-6 (2022).

Staszak, K. et al. Advances in the removal of Cr(III) from spent industrial effluents. Mater 16, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010378 (2023).

El Hajam, M. et al. Statistical design and optimization of Cr(VI) adsorption onto native and HNO3/NaOH activated Cedar sawdust using AAS and a response surface methodology (RSM). Molecules 28, 7271. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28217271 (2023).

García, A. et al. A state-of-the-art of metal-organic frameworks for chromium photoreduction vs. photocatalytic water remediation. Nanomaterials 12, 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12234263 (2022).

Kumar, P. & Singh, J. Photocatalytic activity of nanomaterials in environmental remediation. in Nanomaterials in Environmental Remediation 251–282 (CRC Press, 2021).

Mishra, K., Devi, N., Siwal, S. S., Gupta, V. K. & Thakur, V. K. Hybrid semiconductor photocatalyst nanomaterials for energy and environmental applications: fundamentals, designing, and prospects. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 7, 2300095. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsu.202300095 (2023).

Saleh, T. A. Materials, nanomaterials, nanocomposites, and methods used for the treatment and removal of hazardous pollutants from wastewater: treatment technologies for water recycling and sustainability. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects. 39, 101231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoso.2024.101231 (2024).

Wu, Y. & Bi, L. Research progress on catalytic water splitting based on polyoxometalate/semiconductor composites. Catalysts 11 (524). https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11040524 (2021).

Li, S. et al. x., In situ construction of a C3N5 nanosheet/Bi2WO6 nanodot S-scheme heterojunction with enhanced structural defects for the efficient photocatalytic removal of tetracycline and Cr(VI), Inorg. Chem. Front 9, 2479–2497. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2QI00317A (2022).

Ye, L. & Xia, D. (eds) Layered Materials in Photocatalysis: Environmental Purification and Energy Conversion (Wiley-VCH, 2025).

Xu, D. et al. Progress and challenges in full spectrum photocatalysts: mechanism and photocatalytic applications. J Ind. Eng. Chem. 119, 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2022.11.057 (2023).

Sun, L. J. et al. A review on photocatalytic systems capable of synchronously utilizing photogenerated electrons and holes. Rare Met. 4, 2387–24041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-022-01966-7 (2022).

Balapure, A., Dutta, J. R. & Ganesan, R. Recent advances in semiconductor heterojunctions: a detailed review of the fundamentals of photocatalysis, charge transfer mechanism and materials. RSC Appl. Interfaces. 1, 43–69. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3LF00126A (2024).

Khan, M. S. et al. A review of metal–organic framework (MOF) materials as an effective photocatalyst for degradation of organic pollutants. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 6318–6348. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3NA00627A (2023).

Xiao, Y., Li, S., Xu, J. & Deng, F. Solid-state NMR studies of host–guest chemistry in metal-organic frameworks. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 61, 101633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2022.101633 (2022).

Jafarzadeh, M. Recent progress in the development of MOF-based photocatalysts for the photoreduction of Cr(VI). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 24993–25024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c03946 (2022).

Jiang, J. J., Zhang, F. J. & Wang, Y. R. Review of different series of MOF/g-C3N4 composites for photocatalytic hydrogen production and CO₂ reduction. New. J. Chem. 47, 1599–1609. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2NJ05260A (2023).

Azadi, A., Pourahmad, A., Sohrabnezhad, S. & Nikpassand, M. Synthesis of zeolite Y@ metal–organic framework core@ shell. J. Coord. Chem. 73, 3412–3419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jccs.202200172 (2020).

Azari, B., Pourahmad, A., Sadeghi, B. & Mokhtary, M. Green synthesis of SiO2 from Equisetnm arvense plant for synthesis of SiO2/ZIF-8 MOF nanocomposite as photocatalyst. J. Coord. Chem. 76, 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958972.2023.2166408 (2023).

Zhu, C. Y. et al. Constructed CdS/Mn-MOF heterostructure for promoting photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B. Dyes Pigm. 219, 111607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2023.111607 (2023).

Qi, L. et al. Enhanced generation and effective utilization of Cr(V) for simultaneous removal of coexisting pollutants via MOF@COF photocatalysts. ACS ES&T Eng. 4, 870–881. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestengg.3c00491 (2024).

Bahadori, N., Sohrabnezhad, S., Foulady, R. & Pourahmad, A. Different photocatalytic activity of MoS2 layered-structure@fumarate-based metal-organic framework nanocomposite for two dyes, ChemSelect 10, e202501081. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202501081 (2025).

Li, X., Li, Y. & Zhang, L. Recent advances over the doped g-C3N4 in photocatalysis: a review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 482, 214429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216227 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. g-C3N4-based photocatalytic materials for converting CO2 into energy: a review. ChemPhysChem 25, e202400075. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.202400075 (2024).

Luo, Y. et al. g-C3N4-based photocatalysts for organic pollutant removal: a critical review. Carbon Res. 2, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44246-023-00045-5 (2023).

Hayat, A. et al. A targeted review of current progress, challenges and future perspective of g-C3N4 based hybrid photocatalyst toward multidimensional applications. Chem. Rec. 23, e202200143. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202200143 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Research progress on synthetic and modification strategies of CdS-based photocatalysts. Ionics 29, 2115–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-023-05004-z (2023).

Shen, X. et al. Construction of C3N4/CdS nanojunctions on carbon fiber cloth as a filter-membrane-shaped photocatalyst for degrading flowing wastewater. J. Alloys Compd. 851, 156743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.156743 (2021).

Zhu, B. et al. Quantum Dots in S-scheme photocatalysts. Mater. Today. 82, 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2024.11.012 (2025).

Wu, X., Sayed, M., Wang, G., Yu, W. & Zhu, B. COF-based S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Adv Mater, 1045, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202511322

Liu, B. et al. Prolonging charge carrier lifetime in S-scheme heterojunctions via ligand-to-metal charge transfer of Ni-MOF for photocatalytic H2 production and simultaneous benzylamine coupling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 231, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2025.02.013 (2025).

Wang, C., You, C. & Rong, K. An S-Scheme MIL-101(Fe)-on-BiOCl heterostructure with oxygen vacancies for boosting photocatalytic removal of Cr(VI). Acta Phys-Chim Sin. 40, 2307045. https://doi.org/10.3866/PKU.WHXB202307045 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Pauling-type adsorption of O2 induced by S-scheme electric field for boosted photocatalytic H2O2 production. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 199, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2024.02.048 (2024).

Zhang, W., Zheng, D., Qu, Y., Meng, A. & Su, Y. Simultaneously improving inter-plane crystallization and incorporating K atoms in g-C3N4 photocatalyst for highly efficient H2O2 photosynthesis. Acta Phys-Chim Sin. 40, 2406005. https://doi.org/10.3866/PKU.WHXB202406005 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Highly efficient charge transfer in CdS-covalent organic framework nanocomposites for stable photocatalytic hydrogen evolution under visible light. Sci. Bull. 65, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2019.10.015 (2020).

Girma, S., Taddesse, A. M., Bogale, Y. & Bezu, Z. Zeolite-supported g-C3N4/ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposite: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity study for methylene blue dye degradation. J. Photochem. Photobiol A. 444, 114963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2023.114963 (2023).

Khorrami, M. A., Sohrabnezhad, S., Asadollahi, A., Nouralishahi, A. & Hallajisani, A. Enhanced photo-degradation of organic contaminants on CdS/magnetic aluminum fumarate metal-organic framework as a novel Z-scheme photocatalyst under visible light. Colloids Surf. A. 677, 132399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132399 (2023).

Jia, X. et al. g-C3N4-modified Zr-Fc MOFs as a novel photocatalysis-self-Fenton system toward the direct hydroxylation of benzene to phenol. RSC Adv. 13, 19140–19148. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA03055E (2023).

Khoshkholgh, Z. & Sohrabnezhad, S. Optimizing photocatalytic activity for chromium reduction: the role of MgAl LDH/triazine covalent organic framework/CdS nanocomposite. Emerg. Mater. 8, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42247-024-00833-8 (2024).

Nawaz, R., Jamal, M. A., Naseem, B., Munir, M. & Iqbal, M. Lanthanum/iron oxide nanocomposite for photo-ultrafast removal of Methyl orange dye and toxicity evaluation. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 47, 221 (2025).

Shah, B. R. & Patel, U. D. Mechanistic aspects of photocatalytic degradation of Lindane by TiO₂ in the presence of oxalic acid and EDTA as hole-scavengers. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105458 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Richards, D. S., Grotemeyer, E. N., Jackson, T. A. & Schöneich, C. Near-UV and visible light degradation of iron(III)-containing citrate buffer: formation of carbon dioxide radical anion via fragmentation of a sterically hindered alkoxyl radical. Mol. Pharm. 19, 4026–4042. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00501 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Conjugated π-linker engineering of covalent metal-organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalysis. Chin. J. Chem. 43, 2277–2284. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjoc.70113 (2025).

Thuy, U. T. D. et al. Cu- and Zn-promoted Al-fumarate metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. RSC Adv. 14, 3489–3497. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA07639C (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Protonation of g-C3N4 and its temperature-sensing properties. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Electron. 33, 6190–6200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-022-07794-w (2022).

Gurugubelli, T. R., Ravikumar, R. V. S. S. N. & Koutavarapu, R. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO-CdS composite nanostructures towards the degradation of Rhodamine B under solar light. Catalysts 12, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12010084 (2022).

Fouladi, M., Kavousi Heidari, M. & Tavakoli, O. Performance comparison of thin-film nanocomposite polyamide nanofiltration membranes for heavy metal/salt wastewater treatment. J. Nanopart. Res. 25, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-023-05727-0 (2023).

Li, W., Chen, Q. & Zhong, Q. One-pot fabrication of mesoporous g-C3N4/NiS co-catalyst counter electrodes for quantum-dot-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 10712–10724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-04672-w (2020).

Foulady-Dehaghi, R. & Sohrabnezhad, S. Hybridization of schiff base network and amino-functionalized Cu-based MOF to enhance photocatalytic performance. J. Solid State Chem. 303, 122549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2021.122549 (2021).

Chamanehpour, E., Sayadi, M. H. & Hajiani, M. A hierarchical graphitic carbon nitride supported by metal–organic framework and copper nanocomposite as a novel bifunctional catalyst with long-term stability for enhanced carbon dioxide photoreduction under solar light irradiation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 5, 2461–2477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00459-6 (2022).

Mel’gunov, M. S. Application of the simple bayesian classifier for the N2 (77 K) adsorption/desorption hysteresis loop recognition. Adsorption 29, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-022-00369-5 (2023).

Yan, R. et al. j., Effectiveness and mechanisms of CdS/porous g-C3N4 heterostructures for adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride wastewater in visible light, Appl. Sci. 14, 11372 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/app142311372

Zhang, B. et al. A novel S-scheme 1D/2D Bi2S3/g-C3N4 heterojunction with enhanced H2 evolution activity. Colloids Surf. A. 608, 125598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125598 (2021).

Yuan, L. et al. Metal–organic framework-based S-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts. Nanoscale 16, 5487–5503.https://doi.org/10.1039/D3NR06677K (2024).

Wang, X., Yu, J. & Zhang, H. S-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts: design principles and enhanced photocatalytic performance in MOF-based systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 504, 215674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2024.215674 (2024).

Sundari, S. S. K. et al. Effect of structural variation on the thermal degradation of nanoporous aluminum fumarate metal–organic framework (MOF). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147, 5067–5085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-021-10899-9 (2022).

Haris, F. F. P., Rajeev, A., Poyil, M. M., Kelappan, N. K. & Sasi, S. Development of a MOF-5/g-C3N4 nanocomposite: an effective type 2 heterojunction photocatalyst for Rhodamine B dye degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 60298–60313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-35230-5 (2024).

Korotcenkov, G. II–VI wide-bandgap semiconductor device technology: stability and oxidation. in Handbook of II–VI Semiconductor-Based Sensors and Radiation Detectors: 1, Materials and Technology 517–550 (Springer Int. Publ, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19531-0_18.

Li, X., Edelmannová, M., Huo, P. & Kočí, K. Fabrication of highly stable CdS/g-C3N4 composite for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of RhB and reduction of CO₂. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 3299–3313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-04208-x (2020).

Balaji, D. et al. A review on effect of nanoparticle addition on thermal behavior of natural fiber–reinforced composites. Heliyon 11, e41192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41192 (2024).

Chen, Y., Zhai, B., Liang, Y., Li, Y. & Li, J. Preparation of CdS/g-C3N4/MOF composite with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity for dye degradation. J. Solid State Chem. 274, 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2019.01.038 (2019).

Chen, C. et al. Enhancing dichromate transport and reduction via electric fields induced by photocatalysis. Science 28, 112327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.112327 (2025).

Sun, H. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) via surface modified g-C3N4 by acid-base regulation. J. Environ. Manage. 324, 116431 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116431 (2022).

Zeng, W. et al. A review on recent advances of adsorption and photoreduction of Cr(VI). Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 37, 2493057. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395940.2025.2493057 (2025).

Pattnaik, S. P., Mohanty, U. A. & Parida, K. A timely update on g-C3N4-based photocatalysts towards the remediation of Cr(VI) in aqueous streams. RSC Adv. 14, 36816–36834. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA07350A (2024).