Abstract

This study examines the complexities of climate modeling, specifically in the Panj River Basin (PRB) in Central Asia, to evaluate the transition from CMIP5 to CMIP6 models. The research aimed to identify differences in historical simulations and future predictions of rainfall and temperature, examining the accuracy of eight General Circulation Models (GCMs) used in both CMIP5 (RCP4.5 and 8.5) and CMIP6 (SSP2–4.5 and 5–8.5). The evaluation metrics demonstrated that the GCMs have a high level of accuracy in reproducing maximum temperature (Tmax) with a correlation coefficient of 0.96. The models also performed well in replicating minimum temperature (Tmin) with a correlation coefficient of 0.94. This suggests that the models have improved modeling capabilities in both CMIPs. The performance of Max Plank Institute (MPI) across all variables in CMIP6 models was exceptional. Within the CMIP5 domain, Geophysical Fluid Dynamics (GFDL) demonstrated outstanding skill in reproducing maximum temperature (Tmax) and precipitation (KGE 0.58 and 0.34, respectively), while (Institute for Numerical Mathematics) INMCM excelled in replicating minimum temperature (Tmin) (KGE 0.28). The uncertainty analysis revealed a significant improvement in the CMIP6 precipitation bias bands, resulting in a more precise depiction of diverse climate zones compared to CMIP5. Both CMIPs consistently tended to underestimate Tmax in the Csa zone and overestimate it in the Bwk zone throughout all months. Nevertheless, the CMIP6 models demonstrated a significant decrease in uncertainty, especially in ensemble simulations, suggesting improvements in forecasting PRB climate dynamics. The projections revealed a complex story, as the CMIP6 models predict a relatively small increase in temperature and a simultaneous drop in precipitation. This indicates a trend towards more uniform temperature patterns across different areas. Nevertheless, the precipitation forecasts exhibited increased variability, highlighting the intricate interaction of climate dynamics in the PRB area under the impact of global warming scenarios. Hydrological components in global climate models can be further improved and developed with the theoretical reference provided by this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate projections are key to knowing how climate change could affect different parts of the world1. However, the accuracy and consistency of the climate models used are very important to the reliability of these forecasts2. Over the past ten years, the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) has made useful simulations of past and future climate situations using climate models3,4. The fact that GCMs are available and can be used is a big plus. GCMs let us figure out what the climate will be like in the future based on how many greenhouse gases (GHGs) are in the air. As part of the CMIP, these models are available to the public5,6,7. They provide a complete framework for analyzing and comparing climate projections. By using the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models, we can look at past simulations and future predictions of temperature and precipitation trends in the Panj River Basin in Central Asia. We can also look for any differences or changes between the two models8. These models provide a framework for understanding historical climate trends and projecting future conditions on large-scale domains. However, for regionally focused studies like the Panj River Basin, their coarse resolution may not fully capture localized climatic processes. Dynamically downscaled Regional Climate Models (RCMs) or kilometer-scale climate models, which provide higher spatial resolution, might offer a better representation of the regional climate8. While these approaches are beyond the scope of this study, they represent valuable opportunities for future research.

The climate in the Panj River Basin in Central Asia is changing in important ways like the temperature going up and the number of extreme events going up. These changes have important effects on policymakers. Over the past few decades, the temperature in the area has been steadily going up, leading to warming that has never happened before. Since the middle of the twentieth century, the average annual temperature in the Panj River Basin in Central Asia has gone up by about 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to new statistics. This rise is more than the world average, and it will have big effects on the ecosystems, water supplies, and people in the area. There have also been more extreme weather events in the Panj River Basin. Heatwaves are happening more often and are getting worse, which makes health risks related to heat worse and hurt agricultural output. On the other hand, there have been more powerful rainstorms and flash floods, which have caused damage to infrastructure, killed people and messed up transportation and communication networks. Policymakers need to know what effects climate change is having on these places and how to adapt to lessen the effects and make industries more resilient, so they are ready to deal with these effects as they get worse.

General Circulation Models (GCMs) have been widely utilized in numerous studies to analyze both historical and future climate dynamics. In Central Asia, for example, precipitation data from 30 GCMs in the CMIP6 framework were evaluated for the period 1951–2014 using Climate Research Unit TS 4.04 (CRU) datasets as a benchmark9. Jie et al.10 provided comprehensive insights into future precipitation trends based on historical simulations and projections under four combined SSP scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5) using 15 CMIP6 models. Similarly, Hua et al.11 explored potential future changes in meteorological, hydrological, and agricultural droughts in Central Asia by leveraging CMIP6 multi-model projections. Despite these advancements, there is a notable gap in literature: no comprehensive study has yet compared the historical simulations and future projections of CMIP5 and CMIP6 for the Panj River Basin (PRB) specifically, a region of critical ecological and economic importance.

Given the Panj River Basin’s vulnerability to climate variability and its role in regional water security, this gap is significant. The region’s increasing population and economic growth amplify the impacts of climate change, necessitating the most reliable climate knowledge to inform adaptation strategies. A systematic comparative analysis of CMIP5 and CMIP6 model projections is, therefore, urgently needed to enhance current adaptation measures and streamline climate change planning in this region.

Precipitation patterns in the PRB are intricately influenced by topography, which determines when, where, and how precipitation occurs. Elevation and temperature variations further affect energy infrastructure and water security, posing challenges for hydropower, flood management, and irrigation systems7,8,9,10,15. For instance, precipitation over existing snowpack in mountainous regions often triggers valley river flooding and mudslides. Snow accumulation and storage in glaciers are critical for sustaining seasonal water flow. Any shifts in seasonal precipitation or temperature patterns could significantly impact the region’s hydrological and service sectors, leading to heightened risks of flooding and water scarcity12,13,14. Statistical evidence supports a significant rise in winter precipitation in the eastern Pamirs of Tajikistan since 1979, highlighting the region’s susceptibility to climate variability15.

This study aims to bridge the gap in knowledge by providing a comparative analysis of CMIP5 and CMIP6 models for the Panj River Basin. It evaluates how well these models reproduce historical weather conditions and predict future changes, with a focus on precipitation and temperature. By identifying biases, inconsistencies, and improvements in CMIP6 over its predecessor, the study offers critical insights into the reliability of these models for regional climate forecasting. Key findings reveal that CMIP6 demonstrates reduced uncertainty in precipitation bias bands, suggesting improvements in its ability to represent the diverse climate zones of the PRB. These findings are crucial for policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders working to mitigate or adapt to climate impacts in the region.

Through this analysis, the study contributes to understanding the advancements made in CMIP6, particularly its ability to simulate temperature and precipitation patterns more consistently. By comparing historical simulations and future projections, it highlights the extent of improvements in forecasting climate dynamics and variability. This work not only informs decision-making for climate adaptation but also sets the foundation for refining future climate models in the Panj River Basin and beyond.

Description of the study area and data

Panj River Basin (PRB)

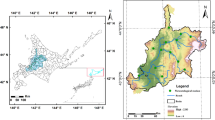

The Panj River Basin is in Central Asia, between latitudes 30°–40°N and longitudes 60°–80°E (see Fig. 1). Stretching 1,200 km along southern Tajikistan, it forms a natural boundary and a vital resource for the region. Covering an area of 114,500 square kilometers, the river is fed by glaciers and snowmelt from the Pamir Mountains, with peaks exceeding 7,000 m. The Panj River flows swiftly, descending over 6,600 m before joining the Vakhsh River to form the Amu Darya. Tajikistan controls two-thirds of the basin, yet its water benefits both sides of the border, supporting agriculture and communities. The river’s tributaries, such as the Gunt, Bartang, Yazghulom, and Vanj, further contribute to its flow.

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the Panj River Basin, generated using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission ((SRTM) data (https://dwtkns.com/srtm30m/) with ArcGIS software 10.2. GIS techniques enhanced and visualized terrain elevations to support climatic and geographic analysis. The software is available at (https://resources.arcgis.com/en/help/main/10.2/).

In the upper basin, rivers are largely fed by snow and glaciers melt during spring and summer, leading to peak flows in the summer. The lower basin is influenced by runoff from spring rain and snowmelt, and river flows are widely used for irrigation. The mean annual flow at the Panj River’s outlet is 1,026 cubic meters per second, with varying runoff across different regions of the basin. However, the area faces challenges, including insufficient irrigation infrastructure and the risk of natural disasters such as floods and mudslides, which are driven by climate conditions.

This study aims to compare the performance of the CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate models in capturing past and future temperature and precipitation patterns in the Panj River Basin. Understanding these differences is essential for improving climate adaptation strategies in this ecologically and economically critical region.

Gridded precipitation and temperature dataset

This study used MERRA-2, which includes precipitation and near-surface temperature with a 0.25-degree spatial resolution. The January 1981–December 2005 dataset provides a complete climate picture. The focal point was the Panj River Basin (PRB), which had long-term data scarcity13. The study validated the PRB model using the MERRA-2 datasets evenly spaced gridded structure due to data scarcity. This structure helps evaluate climate models in regions with little observational data. The product file specification document on the GMAO’s MERRA-2 website13,14 lists analyzed and diagnosed fields to help select variables. The GEOS IAU procedure improved temporal resolution beyond 6-hourly analysis intervals. A 0.625° × 0.5° horizontal grid was used to present three time-invariant and 39 time-varying product collections. Variables were on the native vertical grid (72 model layers or 73 edges) or interpolated to 42 standard pressure levels. Each variable is detailed in the MERRA-2 file specification. Importantly, MERRA-2 provides closed atmospheric budgets with analysis increment terms, like MERRA. It improves the dataset’s precision and completeness, making historical simulations and future projections of PRB climatic variables easier to study. The study is more scientifically sound because such detailed information is available.

Due to the binary nature of precipitation, its anomalies are more complex than temperature anomalies15. Many previous studies have shown that the correlation of observational data with gridded precipitation datasets is less accurate than with gridded temperature datasets16. In this study, we used the MERRA-2 dataset instead of observational data because, for a long period, there have been gaps in records at some meteorological stations in the Pyanj River Basin. In addition, in our previous study, we processed various gridded data in the mountainous area of Tajikistan, and the findings illustrated (Fig. 2) that the observed precipitation data was in good understanding with the precipitation data from the MERRA-2 dataset17. The MERRA-2 reanalysis dataset was chosen for this study due to its systematic approach to producing dynamically consistent climate data, particularly in data-scarce regions like the Panj River Basin. However, we acknowledge that reanalysis datasets have limitations, including uncertainties in precipitation fields derived from forecast outputs, which imperfections may influence in the underlying model. While MERRA-2 provides a valuable framework for climate monitoring, its use as the sole observational dataset introduces limitations, particularly for precipitation validation. Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating multiple observational datasets to discern whether the improved accuracy of CMIP6 is consistently realized across a broader range of metrics.

Global climate models (GCMs)

This research evaluates the implementation of eight Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) models from two generations: CMIP5 and its revised iteration, CMIP6. We are primarily concerned with the Panj River Basin in Central Asia, which is currently experiencing significant water resource difficulties. We utilize monthly precipitation, maximum temperature (Tmax), and minimum temperature (Tmin) data from 2020 to 2099, obtained from the publicly accessible platform https://esgf-node.llnl.gov. To ensure simplicity, we have chosen the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios from CMIP5, along with their corresponding radiative forcing counterparts, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, in CMIP6. This enables us to directly compare future climate projections based on comparable emissions pathways. Through the examination of historical simulations and future projections, our objective is to evaluate the advancements in CMIP6 for this critical area.

Methodology.

To evaluate the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models’ ability to reproduce historical conditions, we compared them to the high-resolution (0.25° × 0.25°) Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2) reanalysis dataset. We concentrated on three important climate variables: mean annual precipitation, maximum temperature (Tmax), and minimum temperature (Tmin). We used both statistical and graphical metrics to assess the models’ previous performance across the Panj River Basin. To ensure that all datasets for comparison were compatible, we used bilinear interpolation to match coarser GCM resolutions to finer MERRA-2 resolutions (Table 1). Finally, this process allows us to confidently forecast future climate change for various CMIPs across the basin’s diverse climate zones.

GCM data

This study uses CMIP6’s Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) to investigate various future climate scenarios for the Panj River Basin, with a focus on two contrasting extremes: SSP2-4.5, representing a "middle-of-the-road" development path as outlined in18, and SSP5-8.5, reflecting a fossil-fuel intensive future described in19. These scenarios cover a wide range of possible radiative forcing targets that can be achieved through various mitigation policies, as described in20. The scenarios RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 from CMIP5 were compared with SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 from CMIP6. While these scenarios align in terms of radiative forcing targets, they are not directly comparable. RCPs are driven solely by radiative forcing trajectories, whereas SSPs incorporate socioeconomic narratives in addition to radiative forcing. SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 represent the best available options for comparing CMIP5 and CMIP6 outputs, given the overlap in radiative forcing levels at 4.5 W/m2 and 8.5 W/m2 by 2100. Moreover, eight GCMs were selected for this study based on their availability in both CMIP5 and CMIP6 frameworks and their relevance to the Panj River Basin. These models have demonstrated reliability in simulating climate dynamics in regions with complex topography. The selection ensures consistency and comparability of historical simulations and future projections while maintaining a practical scope for detailed analysis. However, the nuanced differences between these frameworks should be considered when interpreting the results. To ensure consistency, all data is resampled to a common resolution (0.25° × 0.25°), as previously mentioned. It is important to note that this bilinear interpolation method only enhances granularity and is not based on dynamic or physical modeling of the atmosphere. As such, it does not account for localized climate processes influenced by topography or other fine-scale phenomena. Dynamically downscaled Regional Climate Models (RCMs) could provide more accurate and physically consistent representations of regional climate dynamics, but their use is beyond the scope of this study.

This study uses the Köppen climate classification system, developed by Köppen21 and later modified22, to examine the various climatic conditions in the Panj River Basin (Figure 3). Peel et al.21 describe a well-established approach for categorizing regions based on temperature and precipitation patterns, which serves as a valuable tool for understanding regional environmental characteristics and potential vegetation types. However, Beck et al.23 pointed out limitations in regions with low station density, transition zones, and significant elevation changes. Therefore, careful interpretation is required when applying this classification to the Panj River Basin.

This classification, adapted from Köppen’s original work with slight modifications, divides the Panj River Basin into four distinct climate zones21.

-

Dry Steppe Climate (BSk): Warm summers, cold winters, and little overall precipitation.

-

Dry and Hot Summer (Dsa): Having hot, dry summers and relatively cold winters with slightly more precipitation than BSk zones.

-

Cold deserts (BWk) are characterized by extreme aridity, cold winters, and extremely hot summers.

-

Dry Summer (Csa): Warm to hot summers with little precipitation, and mild winters with more precipitation.

This analysis highlights the significant climatic variability within the Panj River Basin, emphasizing the importance of taking these diverse zones into account when evaluating future climate projections and their potential impacts on the region’s water resources and ecosystems, as discussed by21,22,23.

Statistical and graphical analyses

In this study, we employed the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) metric to evaluate the performance of GCMs in replicating historical climate variables. KGE was selected for its ability to integrate three critical components of model evaluation: Pearson’s correlation (measuring linear association), bias ratio (mean ratio), and variability ratio (standard deviation ratio). This combination makes KGE suitable for assessing both spatial and temporal performance of climate models. Additionally, KGE is less sensitive to outliers compared to other metrics, such as the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), and provides a more holistic evaluation of model accuracy23,24. This single metric combines three important statistical measures: Pearson’s correlation (r), spatial variability ratio, and normalized variance (Eq. 1). This comprehensive approach yields useful insights into model accuracy across multiple dimensions. KGE has several advantages, including being less sensitive to outliers and more accurate in describing overall model fit25. The values range from 1 (perfect match) to -∞, with no meaning assigned to 0. However, KGE values above 0.41, like the Nash-Sutcliff efficiency index, generally indicate reasonable performance, while values closer to 1 indicate high accuracy26. We calculate KGE for three climate variables (precipitation, Tmax, and Tmin) in each GCM and compare them to the reference dataset (1981–2005).

in which pGCM represents the standard deviation for MERRA-2 data and μref stands for the mean for GCM data.

The Taylor diagram27 provides a graphical representation of how well CMIP models reproduce the spatial patterns and variability of key climate variables when compared to MERRA-2 data. Three metrics are combined: the degree of correlation (R) reflects spatial pattern similarity, the centered root-mean-square error (CRMSE) indicates magnitude differences, and the ratio of spatial standard deviations (SD) assesses differences in variability. To assess the seasonal similarity between CMIPs and MERRA-2 precipitation, Tmax, and Tmin, we used statistical tests23: t-test for mean similarity, F-test for variance similarity, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test for distribution similarity28. The results of these tests are critical for understanding the accuracy of future climate projections based on these models.

Future projections

This study compares future climate projections (2020–2099) for Central Asia’s Panj River Basin using the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models under two emission scenarios: RCP4.5/SSP2-4.5 (medium impact) and RCP8.5/SSP5-8.5. We examine median and 95% confidence band projections for seasonal precipitation, Tmax, and Tmin at near (2020–2059) and far (2060–2099) future horizons. While 30-year averages are conventionally used in climate studies, 40-year periods were chosen in this study to capture a broader range of variability and reduce the influence of multi-decadal variability on regional climate projections. This approach is particularly relevant for regions like the Panj River Basin, where interannual and decadal climate variability can significantly influence long-term trends. This approach aids in the quantification of model uncertainty and the understanding of potential changes in various climate zones. Finally, we create maps that show the percentage change in precipitation and the absolute change in temperature to visualize the spatial distribution of projected impacts. This study aims to educate stakeholders about potential future climate challenges in the Panj River Basin and to support adaptation strategies.

Results

Evaluating skills of GCMs

Figure 4 illustrates performance analysis highlights distinct differences between CMIP5 and CMIP6 models in reproducing historical climate variables. While CMIP5 models generally exhibit superior performance in simulating Tmax and Tmin, CMIP6 models show noticeable improvements in reducing uncertainty and enhancing the accuracy of precipitation simulations. Among the CMIP6 models, the MPI model demonstrated exceptional skill in simulating Tmax, outperforming its CMIP5 counterpart. Similarly, the MIROC model in CMIP6 showed improved performance in reproducing Tmin compared to its earlier version. However, certain models, such as CNRM in both CMIP5 and CMIP6, showed suboptimal performance for Tmax simulations, indicating potential limitations in their parameterization schemes.

For precipitation, CMIP6 models generally exhibited enhanced historical simulation capabilities, with MPI emerging as the best-performing model across all variables. The analysis of KGE components reveals that models with higher correlation, lower bias, and better variability ratios contribute significantly to overall performance, as evidenced by the GFDL model in CMIP5 Fig. 5 focuses on the temporal components of the KGE metric, specifically Pearson’s correlation, mean ratio, and variability ratio, for different climate variables. These components provide a detailed assessment of the temporal accuracy of the models. The results indicate that models with values close to the optimum for these components significantly contribute to a higher KGE, as seen in the case of GFDL in CMIP5. This detailed analysis provides insights into the specific strengths and weaknesses of individual GCMs in simulating historical climate variables.

Taylor diagram

Figure 6 uses Taylor diagrams to examine the spatial performance of the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models in replicating annual precipitation, Tmax, and Tmin across the Panj River Basin. The left-hand panels display results for CMIP5, while the right-hand panels correspond to CMIP6. Models positioned closest to the reference circle exhibit higher spatial correlation and better variability replication. The MERRA-2 reference data is represented by a hollow circle on the x-axis, while colored circles represent individual models, and triangles represent the ensemble means for CMIP5 and CMIP6. For CMIP5, Tmax has the highest correlation (0.95), followed by Tmin (0.93) and precipitation (0.38). Similarly, for CMIP6, Tmax (0.96) and Tmin (0.94) show strong correlations, whereas precipitation simulations display a lower correlation (0.40). The analysis highlights that CMIP6 models slightly outperform CMIP5 in simulating Tmax and Tmin, but both frameworks show limitations in accurately replicating precipitation patterns. Overestimated precipitation variability is particularly notable in the MPI and INMCM models.

Seasonal variability

Figure 7 shows how well the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models capture seasonal variability in Tmax across different climatic zones. Compared to CMIP5 (represented by the red line), the CMIP6 MME median (blue line) is generally more consistent with the observed seasonal cycle (zero-bias line), except in the Bwk and Dsa zones. This trend is supported by narrower 95% confidence intervals for CMIP6 in these zones, which indicate lower uncertainty in its Tmax estimates. Notably, CMIP6 exhibits significantly less variation among individual models within these zones, implying greater consistency in simulations. While both CMIPs have higher uncertainty in Bwk zone simulations, they share a systematic bias: they underestimate Tmax in the Csa zone and overestimate it in the Bwk zone throughout the year. These findings highlight the ongoing challenge of accurately modeling seasonal Tmax variations across diverse climatic zones, with CMIP6 showing some advantages in terms of overall bias and uncertainty, especially in specific zones such as Bwk and Dsa.

Continuing the seasonal bias analysis, Fig. 8 shows that CMIP6 Tmin estimates have lower uncertainty than CMIP5 estimates for most months. While both sets of models overestimate Tmin in the Bwk and Csa zones, particularly CMIP6, the Dsa zone has almost no median bias for either MME. Similar patterns emerge for precipitation (Fig. 9), with CMIP6 showing narrower uncertainty bands across all zones. Notably, CMIP5 overestimates Bsk zone precipitation more than CMIP6, despite having differences in simulating monsoon precipitation for the Bsk and Dsa zones. Notably, underestimation dominates in the Bwk zone, as evidenced by negative median and confidence intervals for both CMIP MMEs. These findings are consistent with the statistical evaluations summarized in Table 2. T-tests and F-tests show statistically significant differences between CMIP5 and CMIP6 seasonal MME for precipitation, Tmax, and Tmin in all zones except Bsk. This suggests that, while challenges remain in capturing seasonal patterns across all zones, CMIP6 has lower uncertainty and better agreement with observations than CMIP5.

Projected Tmax, Tmin and Precipitation

Future temperature projections for the study area differ between the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models, especially under different emission scenarios (Fig. 10). While these projections are presented as raw magnitudes rather than anomalies, the trends can still be visually interpreted relative to historical baseline values, highlighting the sharp increases in temperature and significant changes in precipitation patterns under the different scenarios. Notably, CMIP6 projections have significantly lower uncertainty (thinner confidence bands) than CMIP5, indicating higher confidence in their estimates. Interestingly, CMIP5 predicts a greater increase in Tmax under the lower emission scenario (RCP4.5) than the higher one (RCP8.5), whereas CMIP6 shows similar rising trends for SSP scenarios. By 2100, CMIP6 expects Tmax to be 23.3 °C and 26.4 °C under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, respectively, which is significantly lower than CMIP5 projections of 29.9 °C and 31.97 °C for RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. Both models, however, predict a sharp change in Tmax between historical data and future projections. In contrast to Tmax, CMIP6 consistently projects lower Tmin under both emission scenarios than CMIP5. By 2100, CMIP6 predicts Tmin to be -25.4 °C and -22 °C under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, respectively, as opposed to CMIP5’s higher values of -13.6 °C and -12.8 °C for RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. Similar to Tmax, CMIP6 exhibits lower uncertainty in Tmin projections than its predecessor. Overall, these contrasting projections highlight the ongoing challenges of long-term climate modeling, while also indicating potential improvements in uncertainty reduction and temperature trends with CMIP6. The spatial variability in temperature projections likely corresponds to known topographical influences on climate within the Panj River Basin. Elevation differences across the region play a significant role in modulating local temperatures, as higher altitudes typically experience lower temperatures and stronger temperature gradients. Additionally, the variability may be influenced by moisture distribution patterns, with mountainous areas experiencing orographic effects that alter temperature responses. These interactions between topography and atmospheric processes contribute to the observed heterogeneity in temperature projections. More research is needed to understand the reasons for these discrepancies and improve the accuracy of future climate predictions.

The CMIP5 and CMIP6 projections for future precipitation yield divergent perspectives (Fig. 11). While both predict an increase, CMIP6 predicts a larger rise (388 mm by 2100 for SSP2-4.5) than CMIP5. Interestingly, despite potentially larger changes, CMIP6 projections are more uncertain. Emission scenarios have a further impact on these trends: The observed miner decline in raw precipitation values under RCP8.5/SSP5-8.5 highlights greater variability in future projections, particularly for high-emission scenarios reaching 370 mm by 2100. While CMIP5 shows a slight decrease under RCP8.5, the magnitude is less significant. These opposing perspectives highlight the ongoing challenges of modeling future precipitation, emphasizing both the potential for larger increases and the need to reconcile discrepancies caused by different models and emission scenarios. Additional research is required to improve long-term precipitation forecasts and our understanding of climate change impacts.

Projected precipitation trends under medium and high emission scenarios: (a) Precipitation under RCP4.5/SSP2-4.5, and (b) Precipitation under RCP8.5/SSP5-8.5. Projections from CMIP5 (blue line) and CMIP6 (red line) are shown with 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas). The x-axis represents years, while the y-axis represents precipitation (mm).

Spatial changes in temperature and precipitation

The CMIP5 and CMIP6 models predict warming across the Panj River Basin in both near and far future scenarios under medium and high emission pathways, compared to the historical period (1981–2005). Figure 12 depicts these projected changes in annual Tmax. While both models predict rising temperatures, CMIP6 anticipates a larger increase. Across all three time periods, both models predict the highest temperature increase in the Khatlon region and the lowest in the Badakhshon region. This demonstrates the spatial variability in projected warming across the basin.

Like Tmax, the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models predict an increase in minimum temperature (Tmin) across the Panj River Basin for various future scenarios and timeframes compared to the historical period (1981–2005). As shown in Fig. 13, CMIP6 consistently predicts a higher Tmin rise than CMIP5, with both models predicting the highest increase in Khatlon and the lowest in Badakhshon (consistent with Tmax spatial patterns). Notably, the projected increases in Tmax are expected to be greater than those in Tmin.

Figure 14 shows a contrasting picture of precipitation changes. While both CMIP models provide projections for medium and high emission scenarios, they depict very different futures. While some regions, such as Ishkoshim, Roshtqala, Shugnon, and Southern Murghab, are expected to see significant increases (200–300%), others, such as Vanj, Darvoz, and Khatlon region, may experience decreases ranging from -40% to -67%. This demonstrates the highly localized nature of future precipitation changes in the basin.

Discussion

Numerous studies have extensively examined the performance of General Circulation Models (GCMs) from both CMIP5 and CMIP6 in accurately estimating historical climate conditions across various global regions29,30,31,32. Overall, these studies show that CMIP6 models outperform their predecessors, CMIP5. This improvement has been particularly noticeable in a variety of geographic areas, including Central and South America33, Colombia34, the Mediterranean region35, and the Tibetan Plateau36. The superiority of CMIP6 models has been reaffirmed in specific studies on extreme climate indices and events. Notable examples include improved simulations of extreme indices over East Africa37, extreme precipitation and temperature in the main river basins of South Asia38, and extreme precipitation across China39. Similar advancements have been observed in Australia40, the Western North Pacific, and East Asia41, where CMIP6 models provide a more accurate representation of climatic variables than CMIP5.

Specifically, studies focusing on cloud and vapor measurements over the tropical ocean have reported improved performance using CMIP6 models42. Furthermore, investigations into the spatial variability of precipitation and temperature over Bangladesh revealed that the CMIP6 Multi-Model Ensemble (MME) performed better than the CMIP5 MME43. In the context of Central and North India, CMIP6 GCMs demonstrated an improvement in replicating climatic conditions24, and a greater capability in estimating Indian summer rainfall was reported30. Similarly, improvements in modeling were seen in South Korea31. In the Central Asian context, CMIP6 datasets have been useful in revealing changes in the annual precipitation cycle as a result of global warming. Notably, a wetting trend in spring and a drying trend in summer were found29. Given the region’s susceptibility to drought, concerns about changes in drought conditions over Central Asia have been widely addressed44, emphasizing the importance of accurate and advanced climate modeling approaches in understanding and preparing for climate-related challenges in the region.

The study’s findings differ from those in other regions, indicating that the performance of CMIP6 General Circulation Models (GCMs) is comparable to that of CMIP5. GFDL and INMCM in CMIP5 have near-optimal Pearson’s correlation (r), mean ratio (β-1), and variability ratio (γ-1) values, leading to higher Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE). The Taylor Diagram shows that GCMs have the highest correlation with reference data for maximum temperature (Tmax) (0.96), followed by minimum temperature (Tmin) (0.94) and precipitation (0.40), demonstrating their robust ability to model Tmax and Tmin. Most models in both CMIPs reasonably simulate observed precipitation variability, except MPI and INMCM, which overestimate it significantly. The uncertainty in the CMIP6 ensemble is considerably narrower than in the CMIP5 ensemble, consistent with findings from temperature extreme simulations over Australia40. This suggests that CMIP6 GCMs produce more consistent simulations than CMIP5 GCMs, which can be attributed to the uniform use of forcing datasets and boundary conditions across all CMIP6 GCMs45. The study uses common GCMs for both CMIPs and provides a relative performance assessment using two metrics, r and KGE, to evaluate various properties of model execution. The integrated metric KGE, which assesses the model’s ability to construct spatial distributions, variables, and bias, is a reliable indicator of GCM capability.

The future of the Panj River Basin is uncertain due to conflicting climate model projections. When attempting to forecast tomorrow’s weather, it is apparent that there is a discrepancy between the predictions made by CMIP5 and CMIP6.

CMIP6 findings indicate that both moderate (RCP4.5/SSP2-4.5) and high (RCP8.5/SSP5-8.5) emission scenarios are associated with increased temperatures in the distant future (2061–2100). However, the rate of warming under the high emission scenario is significantly greater compared to the moderate scenario, reflecting the stronger radiative forcing associated with SSP5-8.5.

The disorder is intensified by precipitation. The Climatological Model Interim 6 (CMIP6) forecasts a perplexing decline in precipitation despite an anticipated rise in global temperature under high emissions.

The spatial distribution of projected climate changes shows that regions experiencing larger temperature increases, as seen in Figs. 12 and 13, also correspond to areas with reduced precipitation, as indicated in Fig. 14. This relationship suggests that decreased moisture availability may exacerbate temperature increases in certain regions, particularly in arid and semi-arid zones. Although there is some variability in precipitation patterns, the models do not show significant increases in precipitation in previously dry regions, nor do they show decreases in precipitation in wetter areas. Instead, the models highlight the complex interactions between temperature and moisture dynamics driven by regional topographic and climatic factors.

CMIP6 predicts a more uniform distribution of temperatures across the basin. Despite the overall increase in temperatures, there is a possibility that the difference between hotter and colder regions may decrease. However, there are regions with different levels of precipitation. Historical studies have reported a rise in mean annual air temperatures in the Pamir, with variations between the Eastern and Western regions. Seasonal fluctuations in temperature trends are observed, with some exceptions such as decreasing summer temperatures in Murghab. Precipitation patterns show contrasting trends: while overall precipitation in the Pamir is declining, specific locations such as Karakul (Eastern Pamir) and Ishkashim (Western Pamir) exhibit increasing trends. In the Eastern Pamir, precipitation is predominantly declining except for certain regions like Shaimak, which show upward trends. In contrast, precipitation trends in the Western Pamir are influenced by topography and elevation, resulting in localized increases in rainfall at specific heights. These patterns suggest complex interactions between topography, and atmospheric processes driving climatic variability in the region29,33,40,45.

Limitations and future work

This study evaluated CMIP5 and CMIP6 models for the Panj River Basin, providing valuable insights into regional climate dynamics. While the MERRA-2 dataset was used for validation due to its systematic consistency and suitability for data-scarce regions, its limitations, particularly for precipitation derived from forecast outputs, may introduce biases in topographically complex areas. Future studies should incorporate multiple observational datasets to enhance robustness and minimize dataset-specific biases.

The use of General Circulation Models (GCMs) limits the resolution of projections for the Panj River Basin. While GCMs are critical for global climate assessments, their coarse spatial resolution cannot fully capture localized climate dynamics, especially in regions with complex topography. Dynamically downscaled Regional Climate Models (RCMs) provide higher-resolution simulations that can better account for topographical and atmospheric processes. Integrating RCM outputs with GCM data in future studies could improve the accuracy of regional climate projections, reduce uncertainties, and support localized climate impact assessments.

Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) was used as the primary metric to evaluate model performance due to its integration of correlation, bias ratio, and variability ratio. While this offers a holistic assessment, future research could incorporate additional metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for detailed evaluation. Analyzing variations across quantiles of data series would also provide insights into the models’ ability to represent extremes and distributional variability.

Lastly, this study focused on raw outputs from CMIP5 and CMIP6 models to provide a direct comparison of their inherent performance and projections. While this approach avoids uncertainties introduced by post-processing methods, bias correction remains essential for aligning model outputs with observed data. Bias correction reduces systematic errors and improves reliability, but the choice of method may introduce additional uncertainties. Future work should explore the impact of bias correction on CMIP5 and CMIP6 outputs to refine projections and enhance their applicability for regional climate planning.

Conclusion

This study evaluated the suitability of the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models for producing climate projections for the Panj River Basin. While neither model outperformed the other in simulating the current climate, CMIP6 demonstrated lower uncertainty, which may justify greater confidence in its future projections. Both models predict rising temperatures and decreasing precipitation across the basin, with some discrepancies between their projections. This emphasizes the need to improve existing adaptation measures, especially considering potential changes outlined in CMIP6’s SSP scenarios. Low-precipitation regions are expected to see either a decrease or a negligible increase in precipitation, potentially exacerbating flood risks and water stress. Furthermore, climate homogeneity changes may have a significant impact on the basin’s biodiversity. Moving forward, climate modeling efforts should take advantage of the increasing availability of GCMs from both CMIP5 and CMIP6, allowing for more detailed comparisons and contrasts between different model iterations to refine projections and guide informed decision-making for the Panj River Basin.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from multiple public repositories. The MERRA-2 precipitation and near-surface temperature data were obtained from NASA’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO) website (https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-2/). The CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate models used in this study are available from the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) platform (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov). Specifically, data for CMIP5 (RCP4.5, RCP8.5) and CMIP6 (SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5) scenarios were downloaded from this platform. The topographic data used for the Panj River Basin were derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Digital Elevation Model (DEM), available at https://dwtkns.com/srtm30m/. No sensitive or personally identifiable information was used in this study, and no data de-identification was required.

References

Daron, J. D. et al. The role of regional climate projections in managing complex socio-ecological systems. Reg. Environ. Change 15, 1–12 (2015).

Gleckler, P. J. et al. Performance metrics for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008972 (2008).

Change, I. C. Contribution of Working Group I Fifth assessment report intergovernmental panel climate change. Phys. Sci. Basis 1535, 2013 (2013).

D.L. Hartmann. Chapter 11—Global Climate Models. Global physical climatology, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Boston, 325–360 (2016).

Chen, H., Sun, J. & Chen, X. Projection and uncertainty analysis of global precipitation-related extremes using CMIP5 models. Int. J. Climatol. 34(8), 2730–2748 (2014).

Taylor, K.E., et al., CMIP5 data reference syntax (DRS) and controlled vocabularies. PCMDI: San Francisco Bay Area, CA, USA, (2011).

Van Vuuren, D. P. et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Climatic change 109, 5–31 (2011).

Wu, T. et al. The beijing climate center climate system model (BCC-CSM): The main progress from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 12(4), 1573–1600 (2019).

Nashwan, M. S. et al. Development of climate-based index for hydrologic hazard susceptibility. Sustainability 10(7), 2182 (2018).

Nashwan, M. S. et al. Future precipitation changes in Egypt under the 1.5 and 2.0 C global warming goals using CMIP6 multimodel ensemble. Atmos. Res. 265, 105908 (2022).

Ziarh, G. F. et al. Integration of catastrophe and entropy theories for flood risk mapping in peninsular Malaysia. J. flood Risk Manag. 14(1), e12686 (2021).

Government of the Republic of Tajikistan was adopted the National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change in Tajikistan for the period up to 2030. October 2, Decree № 482 (2019).

Bosilovich, M.G., R. Lucchesi, and M. Suarez, MERRA-2: File specification. (2015).

Bosilovich, M. G. et al. Atmospheric water balance and variability in the MERRA-2reanalysis. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0338.1 (2017).

Haylock, M. et al. A European daily high-resolution gridded data set of surface temperature and precipitation for 1950–2006. J. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD010201 (2008).

Berezowski, T. et al. CPLFD-GDPT5: High-resolution gridded daily precipitation and temperature data set for two largest polish river basins. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8(1), 127–139 (2016).

Gulakhmadov, M. et al. Performance analysis of precipitation datasets at multiple spatio-temporal scales over dense gauge network in mountainous domain of Tajikistan. Centr. Asia. 15(5), 1420 (2023).

Fricko, O. et al. The marker quantification of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2: A middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 251–267 (2017).

Kriegler, E. et al. Fossil-fueled development (SSP5): An energy and resource intensive scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 297–315 (2017).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Peel, M. C. et al. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth syst. sci. 11(5), 1633–1644 (2007).

Russell, R.J., Dry climates of the United States: I. Climatic map. 5 University of California Press (1931).

Baker, N. C. et al. Huang, A comparative study of precipitation and evaporation between CMIP3 and CMIP5 climate model ensembles in semiarid regions. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00398.1 (2014).

Gupta, V. et al. Assessment of precipitation extremes in India during the 21st century under SSP1-1.9 mitigation scenarios of CMIP6 GCMs. J Hydrol. 590, 125422 (2020).

Radcliffe, D. et al. PRISM vz CFSR precipitation data effects on calibration and validation of SWAT models. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 53(1), 89–100 (2017).

Knoben, W. J. et al. Inherent benchmark or not?. Comparing Nash-Sutcliffe Kling-Gupta Effic. Scores 23(10), 4323–4331 (2019).

Taylor, K. E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res. 106(D7), 7183–7192 (2001).

Sardeshmukh, P. D., Compo, G. P. & C.J.J.o.C. Penland,. Changes of probability associated with El Niño. J. Clim. 13(24), 4268–4286 (2000).

Jiang, J. et al. Future changes in precipitation over Central Asia based on CMIP6 projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 15(5), 054009 (2020).

Gusain, A., Ghosh, S. & S.J.A.R.,. Karmakar, Added value of CMIP6 over CMIP5 models in simulating Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Atmos. Res. 232, 104680 (2020).

Song, Y. H., Chung, E. S. & S.J.I.J.o.C.,. Shahid, Spatiotemporal differences and uncertainties in projections of precipitation and temperature in South Korea from CMIP6 and CMIP5 general circulation model s. Intl. J. Climatol. 41(13), 5899–5919 (2021).

Yazdandoost, F. et al. Evaluation of CMIP6 precipitation simulations across different climatic zones: Uncertainty and model intercomparison. Atmos. Res. 250, 105369 (2021).

Ortega, G. et al. Present-day and future climate over central and South America according to CMIP5/CMIP6 models. Intl. J. Climatology. 41(15), 6713–6735 (2021).

Arias, P. A. et al. Colombian climatology in CMIP5/CMIP6 models: Persistent biases and improvements. Rev. Fac. Ing. Univ. Antioquia 100, 75–96 (2021).

Bağçaci, S. Ç. et al. Intercomparison of the expected change in the temperature and the precipitation retrieved from CMIP6 and CMIP5 climate projections: A Mediterranean hot spot case. Turkey. 256, 105576 (2021).

Lun, Y. et al. Assessment of GCMs simulation performance for precipitation and temperature from CMIP5 to CMIP6 over the Tibetan Plateau. Intl. J. Climatol. 41(7), 3994–4018 (2021).

Ayugi, B. et al. Comparison of CMIP6 and CMIP5 models in simulating mean and extreme precipitation over East Africa. Intl. J. Climatol. 41(15), 6474–6496 (2021).

Zhu, X. et al. Extreme climate changes over three major river basins in China as seen in CMIP5 and CMIP6. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1187–1205 (2021).

Luo, N. et al. Added value of CMIP6 models over CMIP5 models in simulating the climatological precipitation extremes in China. Intl. J. Climatol. 42(2), 1148–1164 (2022).

Deng, X. et al. Evaluation of extreme temperatures over Australia in the historical simulations of CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Earth’s Fut. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF001902 (2021).

Chen, C.-A. et al. Evaluation and comparison of CMIP6 and CMIP5 model performance in simulating the seasonal extreme precipitation in the Western North Pacific and East Asia. Weather Clim. Extremes 31, 100303 (2021).

Jiang, J. H. et al. Improvements in cloud and water vapor simulations over the tropical oceans in CMIP6 compared to CMIP5. Earth Space Sci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EA001520 (2021).

Kamruzzaman, M. et al. Comparison of CMIP6 and CMIP5 model performance in simulating historical precipitation and temperature in Bangladesh: a preliminary study. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 145, 1385–1406 (2021).

Guo, H. et al. Space-time characterization of drought events and their impacts on vegetation in Central Asia. J. Hydrol. 564, 1165–1178 (2018).

Taylor, M. A. et al. Future caribbean climates in a world of rising temperatures: The1.5 vs 2.0 dilemma. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0074.1 (2018).

Funding

This research was sponsored by the following funding sources: Tianshan Talent Training Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous region (Grant No. 2023000137), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42230708/42361144887), the Research Fund for International Scientists of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42150410393), the K.C. Wong Education Foundation (Grant No. GJTD-2020–14), and Joint CAS-MPG Research Project (HZXM20225001MI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conceptual aspects of this work were collaborated upon by all of the authors. The overall layout of the research was drawn up by X.C., A.G., and T.L. The study was conducted by A.G., who also wrote the report. M.U.N., N.G., and M.G., M.R. contributed to the data management and analysis. M.R revised the manuscript structure. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gulakhmadov, A., Chen, X., Gulahmadov, N. et al. Modeling of historical and future changes in temperature and precipitation in the Panj River Basin in Central Asia under the CMIP5 RCP and CMIP6 SSP scenarios. Sci Rep 15, 3037 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86366-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86366-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Review of global climate models used for drought assessment and forecasting

Discover Water (2026)

-

Evaluating the performance of selected CMIP6 GCMs for simulations of historical temperature over Ethiopia

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2026)