Abstract

Excessive gestational weight gain may be associated with unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. We explored the impact of excessive weight gain on components of HDL metabolism in maternal plasma: sterol composition of HDL particles, distribution of HDL subclasses and SCARB1, ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes expressions and their associations with newborns’ characteristics. The study included 124 pregnant women, 58 with recommended and 66 with excessive weight gain. Concentrations of cholesterol synthesis marker, desmosterol, within HDL increased during pregnancy in both groups of participants. In women with excessive weight gain, levels of cholesterol absorption marker, campesterol, within HDL were significantly lower in the 3rd trimester compared to the 1st and 2nd trimesters. Relative proportions of large HDL 2b subclasses increased during pregnancy in women with recommended weight gain. Women with high pre-pregnancy BMI and excessive gestational weight gain had the lowest levels of β-sitosterol within HDL and the highest relative proportions of HDL 3a and HDL 3b subclasses in the 2nd trimester. Large HDL 2b particles were in positive correlation, while smaller HDL 3 subclasses and SCARB1 gene expressions were in negative correlation with APGAR scores. In conclusion, excessive weight gain could contribute to altered metabolism of HDL, and subsequently to poorer neonatal outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational weight gain is inherent to pregnancy and occurs due to the development of placenta and amniotic fluid, growth of fetal tissues and maternal metabolic changes1,2. It is essential for the safe completion of pregnancy, but excessive weight gain during this period may be associated with many unfavorable outcomes, both for the mother and the newborn, such as gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preterm delivery, macrosomia and childhood obesity1.

As outlined in the recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists3, what is considered healthy gestational weight gain greatly depends on pregestational body mass index (BMI). This underlines the importance of maintaining maternal metabolic health before and throughout pregnancy, to ensure a positive outcome.

Body weight changes are generally accompanied by alterations in lipoprotein metabolism, including high-density lipoproteins (HDL)4. In addition to the main role in the uptake and transport of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver5, HDL particles have several other protective effects: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, vasodilatory, and anti-thrombotic4,6. However, these roles may be reduced due to the growth of dysfunctional HDL particles, as a consequence of inappropriate weight gain7. Namely, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), the most measured HDL characteristic, normally increases by about 25% during pregnancy8, but it has been shown that in overweight and obese pregnant women its concentration does not increase to the same extent as in a healthy pregnancy7. Given that HDL has an essential role in the balanced intake and efflux of cholesterol from the trophoblasts, ensuring the fetus receives adequate amounts of cholesterol, lower HDL-C levels could be associated with poorer neonatal outcomes9. Besides HDL-C levels, changes in other, less investigated components of HDL particles are being increasingly examined.

Non-cholesterol sterols (NCS), even though not a part of the routine lipid profile determination, are promising markers of overall cholesterol metabolism. Namely, plasma levels of endogenous cholesterol synthesis intermediates (e.g. desmosterol, 7-dehydrocholesterol and lathosterol) are useful markers of the extent of cholesterol synthesis in the body, while phytosterols (e.g. campesterol and β sitosterol), which use the same intestinal absorption routes as exogenous cholesterol, can be applied as markers of cholesterol absorption. Additionally, recent studies indicate potential significance of determining these lipids within HDL particles, intending to monitor changes in HDL metabolism10. Since it has been previously known that NCS levels change in overweight and obesity11, assessment of NCS within HDL throughout pregnancy could more clearly indicate changes in HDL metabolism associated with gestational weight gain.

Changes in pregnancy-related HDL subclasses distribution are poorly studied, and even less is known about their association with gestational weight gain and newborns’ characteristics12. However, there is evidence that physiological pregnancy is accompanied by an increase in large HDL 2b subclasses, indicating proper functioning of the HDL metabolism13. On the other hand, the impact of obesity on HDL metabolism and particle redistribution toward small HDL 3 subclasses is well understood, as well as the outcomes of these changes4. Namely, in a physiological state, smaller HDL subclasses have a strong atheroprotective effect, given that these particles are responsible for cholesterol uptake, which leads to their transformation into larger particles and further catabolism back to smaller HDLs. However, in proinflammatory and hyperlipidemic conditions, commonly seen in obesity14, the composition of small HDLs alters and their functional properties diminish15, so the entire process of reverse cholesterol transport deteriorates. Considering that, it would be important to explore the direction of changes in HDL subclasses distribution in women with excessive weight gain during pregnancy and its possible effects on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes.

As previously mentioned, HDL plays a key role in reverse cholesterol transport, a process that includes the transport of cholesterol from the extrahepatic tissues to the liver. Important components of this process are protein transporters, such as ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1). ABCA1 ensures the transfer of cholesterol and phospholipids from the cell membrane to lipid-free apolipoprotein A-I, while ABCG1 has a similar role, but its target lipid acceptors are large, spherical HDL particles16,17. On the other hand, scavenger receptors class B type I (SCARB1), are primarily expressed on the hepatocytes and involved in the bidirectional transport of cholesterol between HDL particles and cell membrane, thus regulating cholesterol levels in cells18,19. Altered expression of genes that encode these proteins has been shown to affect the metabolism of HDL particles20. However, knowledge about the impact of gestational weight gain on the expression of these genes is limited. Additionally, the question arises wheter such changes in gene expression during pregnancy and subsequent alterations of HDL structure and function could be related to the neonatal characteristics.

This study aimed to explore longitudinal changes in components of reverse cholesterol transport in pregnant women, according their gestational weight gain. In particular, we monitored the levels of HDL-C and NCS within HDL particles, distribution of HDL subclasses and the expressions of ABCA1, ABCG1 and SCARB1 genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) across trimesters among different weight categories of pregnant women, to investigate the impact of excessive gestational weight gain on metabolism and functionality of HDL. Additionally, the link between previously mentioned parameters and the newborns’ characteristics was examined.

Results

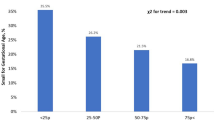

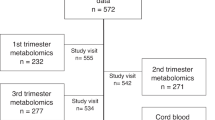

General characteristics of study participants who were stratified according to the weight gain during pregnancy are presented in Table 1. A total of 124 participants attended all medical examinations and had complete laboratory analyses, so they formed the final study group. 95 out of 124 women ended their pregnancies without any complication, while the remaining 29 developed one or more concomitant complications, which included: 12 cases of gestational hypertension, 10 cases of gestational diabetes, 8 cases of oligohydramnios, 4 cases of prolonged delivery, 2 cases of preterm delivery, 2 cases of morbidly adherent placenta, 2 cases of premature ruptures of membranes, 1 case of preeclampsia, 1 case of polyhydramnios and 1 case of placental abruption. The examined groups didn’t differ by age, pre-pregnancy BMI and smoking status. Also, there were no significant differences in the frequency of pregnancy or delivery complications, although we noticed a higher prevalence of complications in the group with excessive weight gain. As we expected, women in the excessive pregnancy weight gain group gained significantly more weight during this period compared to those who had the recommended weight gain. Additionally, we made a comparison of neonatal outcomes between groups. There were no differences in birth weight, length and APGAR scores in the first and fifth minute between newborns according to the maternal pregnancy weight gain, even if there was a numerically greater percentage of lower APGAR score cases in the group with excessive weight gain.

Table 2 shows longitudinal changes in levels of HDL-C and non-cholesterol sterols in HDL, proportion of HDL particles and SCARB1, ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA expression across trimesters in the group of pregnant women with recommended weight gain. HDL-cholesterol concentrations were significantly lower in the first trimester compared to the second and third trimesters. No major changes were seen in the levels of cholesterol synthesis and absorption markers, except for desmosterol and lathosterol in HDL, with the highest levels in the 3rd trimester. Relative proportions of HDL 2b subclasses were at the threshold of statistical significance with the lowest percentages in the 1st trimester. We found no differences among trimesters in the expressions of SCARB1, ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes.

Analogous analysis was conducted for the group of women who had excessive weight gain during pregnancy (Table 3). We found that the levels of HDL-C in the 1st trimester were significantly lower than the values in the other examined periods of pregnancy. Likewise, concentrations of desmosterol in HDL were the lowest at the beginning of pregnancy, with a trend of constant increase in 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Even though the levels of campesterol in HDL were not different in the first two trimesters, concentrations of this marker of cholesterol absorption were in significant decline in the 3rd trimester. A similar trend was observed for β-sitosterol in HDL, but without reaching statistical significance. Regarding HDL subclasses, we observed a significant difference only for HDL 3a. Relative proportions of these particles were lower in the 2nd trimester than in 1st and 3rd trimester. Differences in the expression of SCARB1 gene across trimesters were of borderline significance, with the highest value in the 2nd trimester.

To explore the concomitant effects of pre-pregnancy BMI and pregnancy weight gain, we examined differences in levels of lipid markers within HDL particles, relative proportions of HDL subclasses, and SCARB1, ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA expression among groups of pregnant women who were stratified in four weight categories, in each trimester. The results showed that changes in examined parameters become significant during the 2nd trimester (Table 4), while we presented the values obtained in the 1st and 3rd trimesters in the supplementary section. We observed that levels of β-sitosterol within HDL in 2nd trimester were significantly higher in the group of women with normal pregestational BMI and recommended weight gain during pregnancy, compared to those with excessive weight gain, regardless of BMI before pregnancy. Also, in this period of pregnancy, we noticed the highest percentage of HDL 3a and HDL 3b particles in pregnant women with elevated pre-pregnancy BMI (≥ 25 kg/m2) and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. We didn’t find significant differences for these parameters in the 1st trimester, except for HDL 2b particles, whose prevalence was the lowest in women who had increased pregestational BMI before pregnancy and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Similarly, values of the tested parameters, measured in the 3rd trimester, did not differ among four weight categories of pregnant participants (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Finally, we estimated correlations between characteristics of newborns and maternal BMI, sterols within HDL, HDL subclasses and SCARB1, ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA expressions, across trimesters (Table 5). This analysis showed a significant positive association between maternal BMI in 1st and 3rd trimester and newborns’ weight. On the other hand, BMI in each trimester negatively correlated with 1 min APGAR score. Pregnancy weight gains during 2nd and 3rd trimesters were in positive correlation with newborns’ head circumferences, as well as levels of HDL-C with APGAR scores. Relative proportions of HDL 2b subclasses in 2nd trimester were in positive association with 1 min APGAR score, while the prevalence of these particles during 3rd trimester negatively correlated with newborns’ weight and length. Higher proportions of HDL 3a in 2nd and 3rd trimesters were associated with lower 5-min APGAR scores and higher newborn length, respectively. Relative proportions of HDL 3b subclasses in 3rd trimester positively correlated with newborns’ weight and length. Additionally, newborns’ weights and lengths were in positive association with proportions of maternal HDL 3c in 3rd trimester. Gene expressions of SCARB1 in 2nd trimester negatively correlated with 1 min APGAR score. Expressions of ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes during last trimester were in negative correlation with newborns’ head circumferences, whilst ABCA1 gene expressions were also negatively associated with birth length.

Discussion

In this study, we simultaneously followed longitudinal changes in several biomarkers of HDL metabolism in women with recommended and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Our results have demonstrated that excessive gestational weight gain is associated with characteristic patterns of changes in the metabolism of HDL particles, which were most prominent in the 2nd trimester. Finally, we found associations between HDL-related parameters in maternal plasma and newborns’ characteristics.

Gestational weight gain is intrinsic to pregnancy, but if exceeds the recommended limits, it may be associated with the development of pregnancy complications and poor neonatal outcomes21. Excessive weight gain in pregnancy may also lead to inadequate alterations of maternal lipid status7. Namely, HDL-C levels are expected to rise in pregnancy, reaching the peak during 2nd trimester22, which was demonstrated in both of our analyzed groups. When we stratified our participants according to the pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, we found no significant differences among groups. Noteworthy, the trend of lower HDL-C levels in all three trimesters was observed in groups with excessive weight gain, regardless of BMI before pregnancy. Previous studies have shown that pregestational BMI and excessive weight gain during pregnancy influence the decrease of HDL-C concentrations, thus increasing the risk for the development of complications, such as gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus and preeclampsia23,24. However, the results are inconsistent, as some studies found no differences in lipid parameters between pregnant women with recommended and excessive gestational weight gain7,25. Such discordant findings could be related to the fact that HDL-C might not be the most reliable biomarker of overall HDL metabolism. Having in mind the complexity of HDL’s structure and function, other more advanced indicators should be employed to comprehensively assess its alterations during pregnancy. More specifically, NCS levels within HDL particles could more precisely reflect the balance of cholesterol synthesis, absorption and cellular transfer during pregnancy. Likewise, the distribution of HDL particles indicates the changes in their metabolism and function, whilst determination of ABCA1, ABCG1 and SCARB1 gene expressions in PBMCs could point towards the interplay between HDL and cell membranes.

Although a small number of studies have examined changes in NCS levels during pregnancy, it is well known that lipoproteins, including HDL particles, contain cholesterol precursors26. Bearing in mind the observed increase of HDL-C in pregnancy, we could expect elevation of NCS in HDL as well. Indeed, the levels of cholesterol biosynthesis markers, desmosterol, within HDL increased during pregnancy, in both groups of participants. A similar trend was observed for concentrations of lathosterol in HDL, but only in the group of women with recommended gestational weight gain. However, we found a decrease of campesterol in HDL particles during 3rd trimester in women with excessive gestational weight gain. It is already known that overweight and obesity are associated with reduced cholesterol absorption10, and our findings support the hypothesis that excessive weight gain in pregnancy affects the balance between cholesterol synthesis and absorption. Thus, even if we did not find differences in total HDL-C levels, we did observe unique patterns of alterations of NCS in HDL particles with respect to the extent of gestational weight gain. We have previously demonstrated that NCS content in HDL is affected by pregestational BMI23, and our current results suggest that HDL’s sterol composition is influenced by gestational weight gain as well. Importantly, it has been shown that phytosterols exhibit significant effects on overall lipid metabolism and structure and function of lipoprotein subclasses27, thus it is possible that altered phytosterols’ composition of HDL particles diminish their functional capacity. Knowing that HDL plays many important roles during pregnancy28, decreased phytosterols within HDL, as observed in cases of excessive weight gain, might contribute to the development of pregnancy complications in this group.

To further explore this topic, we analyzed HDL subclasses distribution throughout pregnancy. In line with previous observations, we noticed an increase in large functional HDL 2b subfractions in the group with recommended weight gain, while such rise was not seen in women with excessive gestational weight gain. Elevated proportion of HDL 2b subclasses could be expected in healthy pregnancy, due to the impact of estrogen on overall HDL metabolism29. Comparing further the relative proportions of HDL 2b among different weight categories, we noticed the lowest values in the group of women with excessive pre-pregnancy BMI and excessive gestational weight gain. Even though these differences did not reach statistical significance in every period of pregnancy, they could serve as a basis for more detailed studies of the influence of overweight and obesity in pregnancy on HDL subclasses distribution. On the other hand, when analyzing the distribution of smaller HDL 3 subclasses, we noticed a reverse trend. Relative proportions of HDL 3a particles were significantly lower in the 2nd trimester compared with early and late pregnancy in women with excessive gestational weight gain. Additionally, the prevalence of these subclasses, as well as HDL 3b, was the highest in women with excessive BMI before pregnancy and excessive weight gain during this period. According to these results, we can hypothesize that inadequate gestational weight gain leads to a redistribution of HDL subclasses towards smaller HDL 3 particles. It is known that obesity in general may cause this kind of reallocation4,30, which further leads to reduced protective role of HDL particles31.

Our study also analyzed changes in the expression of genes encoding the synthesis of proteins involved in cholesterol transport to and from HDL particles, across trimesters, as well as among four weight categories of pregnant women. We noticed a trend of increasing PBMC SCARB1 gene expressions throughout trimesters in women with excessive gestational weight gain, although with borderline statistical significance. Notably, similar trends, although without reaching statistical significance, were seen for ABCA1 gene expressions, while ABCG1 gene expressions tend to decline in the same group. Such findings could be associated with the observed redistribution of HDL subclasses in cases with excessive weight gain. Namely, it is possible that increased ABCA1 and SCARB1 gene expressions, by promoting formation and maturation of HDL particles, counteract detrimental effects of maternal hypercholesterolemia in pregnancies accompanied by obesity and excessive weight gain. On the other hand, decreased ABCG1 gene expression is in line with higher prevalence of smaller HDL 3b particles and compromised formation of larger HDL 3a subclasses, as seen in the 2nd trimester in this group, since this transporter is involved in cholesterol efflux to larger HDL particles32.

It is noteworthy that majority of differences among the groups were seen in the 2nd trimester. It is well known that a shift between anabolic and catabolic phases of pregnancy occurs in the 2nd trimester33, so it is reasonable to expect that any deviation from typical metabolism in pregnancy could be detected in this period. Accordingly, a thorough insight into the metabolic biomarkers in the 2nd trimester of pregnancy could be very useful for prediction of the development of complications and unfavorable outcomes.

Further, our focus was on examining correlations of neonatal characteristics with maternal BMI, pregnancy weight gain, and indicators of HDL metabolism. BMI in pregnancy positively correlated with birth weight and negatively with APGAR scores, which is an expected result considering that it is already well known that overweight and obesity in pregnancy increase the risk of macrosomia34,35 and less favorable neonatal outcomes36. Another expected finding was the positive association between HLD-C levels and APGAR scores. Such correlation could be explained by the role of HDL particles in cholesterol transfer to the fetal circulation, which is essential for adequate intrauterine development9,37.

Intriguing correlations were found for relative proportions of HDL subclasses and newborns’ characteristics. Namely, birth weight and height were in inverse association with relative proportion of HDL 2b particles, while in positive correlation with relative proportions of HDL 3b and HDL 3c. It could be assumed that these results reflect the impact of gestational weight gain on redistribution of HDL particles towards small HDL 3, with decreased functional capacity. This could further have long-term consequences for the offspring, including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus, as reported in previous studies38,39. These assumptions are supported by the negative association observed between relative proportions of HDL 3a and HDL 3b subclasses and APGAR scores.

We also noticed that reduced expressions of ABCA1 and ABCG1 genes in the 3rd trimester were associated with higher head circumference. In addition, ABCA1 gene expression negatively correlated with birth height. As we previously postulated, increased expressions of these genes in PBMCs might reflect an adverse vascular milieu in women with excessive weight gain during pregnancy, which could also explain the observed associations with less favorable neonatal outcomes. Equally important, we observed that during late pregnancy mRNA ABCA1 levels correlated with birth height in the opposite direction compared to the relative proportions of HDL 3 subclasses, which could strengthen our hypothesis that excessive weight gain leads to a reduced cholesterol efflux to small HDL 3 particles. ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins are also expressed in placenta and involved in cholesterol transport from maternal to fetal circulation40. Previous studies have reported differences in lipid profile of maternal and cord blood37, which are likely caused by modulations of activities of cholesterol transporters. It should also be mentioned that an association between higher expression of placental ABCA1 gene and preterm delivery has been shown41. Accordingly, elevated gene expressions of cholesterol transporters in maternal PBMCs might indicate metabolic perturbations that could lead to the development of pregnancy and delivery complications.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, we did not explore the possible influence of the existing pregnancy complications on the observed alterations of HDL metabolism. However, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of pregnancy complications between the groups with recommended and excessive weight gain. Nevertheless, future research should examine the influence of weight gain in a cohort of pregnant women without any gestational complications. Second, a high proportion of pre-pregnancy smokers was observed in both groups of participants. It is well known that smoking affects HDL metabolism, by lowering levels of HDL-C and altering the distribution of HDL subclasses42. Studies also suggest that pre-pregnancy smoking may be associated with unfavorable neonatal outcomes43. Considering those facts, further studies that explore the simultaneous effects of smoking and excessive weight gain are needed. Further, the study design comprised the analyses of HDL-related biomarkers in maternal, but not in cord blood. To fully explore the effects of obesity and weight gain in pregnancy, HDL metabolism-related indicators should be determined in cord blood as well. In addition, potential changes in the examined gene expressions should be explored in placenta. However, given that maternal blood and PBMCs are the most accessible biological samples in pregnancy, identification of potential biomarkers of pregnancy and delivery complications in maternal blood is of paramount importance.

In conclusion, our results have shown a significant decrease of cholesterol absorption markers in HDL particles, in parallel with an increase of PBMCs SCARB1 gene expressions and a shift towards smaller HDL subclasses throughout trimesters of pregnancy which is characterized by excessive gestational weight gain. Relative proportions of smaller HDL 3 subclasses and PBMCs SCARB1 gene expressions negatively correlated with APGAR scores at the delivery. The obtained findings suggest that excessive weight gain could contribute to altered metabolism of HDL, and subsequently to less favorable neonatal outcomes. Further studies are needed to explore causality between the observed metabolic changes and thereby to verify our current findings.

Material and methods

Participants

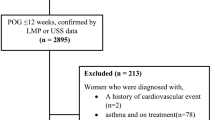

This longitudinal study is a part of a larger research project (HIgh-density lipoprotein MetabolOMe research to improve pregnancy outcome—HI-MOM), which included pregnancies monitoring in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic “Narodni front”, Belgrade, Serbia. The study participants were enrolled during their first medical check-up at the beginning of pregnancy and followed till delivery, through scheduled clinical and laboratory examinations at the end of each trimester. Exclusion criteria for participation in the research were: multifetal pregnancies, any acute conditions recorded at medical examinations, chronic liver or kidney diseases, malignant diseases before pregnancy and/or use of lipid-lowering drugs. Blood pressure, weight and height of pregnant women were measured at each medical check-up. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Values above 25 kg/m2 are considered elevated, according to the World Health Organization recommendations44. In addition, weight gain was monitored throughout the trimesters, based on which pregnant women were divided into two categories: recommended and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. According to the guidance of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the recommended pregnancy weight gain for underweight women (pregestational BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) is 12.7–18.1 kg. For those women with pre-pregnancy BMI within the range of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, the recommended weight gain in pregnancy is 11.3–15.9 kg. Overweight women (pregestational BMI: 25–29.9 kg/m2) should keep their gestational weight gain between 6.8 and 11.3 kg, while for obese women (pregestational BMI > 30 kg/m2), the recommended pregnancy weight gain is 5–9.1 kg3. Anthropometric data for newborns were collected at the delivery and include weight (g), height (cm), head circumference (cm) and APGAR score values obtained 1 min and 5 min after birth. The parameters that make up the total APGAR score, as a method for assessing the vitality of a newborn, are as follows: skin color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, and respiration45. Although APGAR score values above 7 are considered reassuring45, we chose cut-off 9 because only one newborn had an APGAR score at the first and fifth minute below 7. The study was conducted according to the ethical principles defined in the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of Gynecology Clinic “Narodni front”, as well as by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Belgrade and Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade. All participants signed an informed written consent form before enrollment.

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected at three time points, by the end of each trimester, after overnight fasting. Serum and plasma were separated after centrifugation (1500 × g for 10 min) and samples were then frozen at − 80 ◦C until analysis. PBMCs were isolated from an EDTA whole blood sample using Ficoll-Paque™ PLUS medium (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA). PBMCs were used as material for the determination of gene expressions, due to their analytical reliability and accessibility by a minimally invasive method. RNA isolation was conducted with TRIzol™ reagent (Ambion, Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the samples were stored at − 80 °C until reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed.

Methods

Levels of HDL-C were measured in serum by routine enzymatic method at an automated analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Quantification of non-cholesterol sterols (NCSs): desmosterol, 7-dehydrocholesterol and lathosterol (cholesterol synthesis markers), as well as campesterol and β sitosterol (cholesterol absorption markers) within plasma HDL particles was carried out using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS) method, after a sample preparation procedure46. The first step was a removal of ApoB-containing lipoproteins from plasma by mixing 100 µL of sample and 500 µL of ApoB-precipitation reagent (BioSystems, Barcelona, Spain), which contained phosphotungstate (0.4 mmol/L) and magnesium chloride (20 mmol/L). After vortexing, 10 min of incubation and centrifugation (10 min at 600 rpm), we added 650 µL of supernatant to a glass tube with dried internal standard (50 µL of d6-cholesterol, 1 mg/mL). Next, in the tube was added 1 mL of 2% ethanolic KOH, followed by 30 min incubation at 45 ◦C. After period of incubation, we added in each tube n-hexane (2 mL) and HPLC-grade deionized water (500 µL) for extraction, vortexed for 30 s, centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 g and transferred upper, organic, lipid containing layer into new, clean tubes. After this procedure has been repeated three times, we added 4 mL of HPLC grade deionized water in tubes with organic layers, centrifuged (5 min at 1500 g), separated upper layers again into new glass tubes and evaporated for 30 min. The final step of preparation was reconstitution of the extracts with 20 µL of HPLC-grade methanol. After the preparation procedure, 10 µL of each sample were injected into Porochell 120 EC column (2.5 µm, 4.6 × 150 mm) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The mobile phase included acetonitrile, methanol and HPLC-grade deionized water with 0.1% of formic acid, in ratio of 80:18:2. Isocratic elution was carried-out at a mobile phase flow rate of 0.6 mL/min for 45 min and column temperature of 30 ◦C. For quantitative analysis triple quad mass spectrometer was used (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The principle of operation of this system, which has APCI as an ion source, is multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM).

The separation of HDL subclasses in plasma was conducted using vertical gradient gel electrophoresis. Detailed procedure was explained in earlier publications12,47. A casting system Hoefer SE 675 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Vienna, Austria) was used for the preparation of composite polyacrylamide gradient gels (3–31%). Electrophoretic separation was performed using Hoefer SE 600 Ruby [Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Vienna, Austria] unit. The conditions were as follows: temperature of 8 °C, Tris buffer (90 mmol/L of Tris, 80 mmol/L of boric acid and 2.7 mmol/L of Na2EDTA), pH 8.35. After the gel activation process (290 V for 50 min), 25 µL of plasma (30 µL) and 0.1% bromophenol blue in 40% sucrose (10 µL) mixtures were applied to the gels. High Molecular Weight Proteins (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Vienna, Austria) were used as calibrators for the HDL subclasses size. After 20h of electrophoresis separation, gels were fixed for one hour in a 10% trichloroacetic acid, and then washed for one hour in a 45% ethanol. This was followed by overnight staining in Sudan Black (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Gel lanes containing protein standards were detached and stained separately in Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). For densitometric scanning of gels and subsequent analysis, we used Image Scanner III (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Vienna, Austria] with Image Quant software (version 5.2;1999; Molecular Dynamics). Relative proportions (%) of HDL subclasses were determined based on the areas under the corresponding peaks at the densitometric scan for each sample.

Gene expression determination

RT and real-time PCR experiments were executed on the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed in real-time mode using SDS Version 1.4.0.25 software. RT was carried out with the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). For real-time PCR TaqMan® 5’-nuclease gene expression assays were utilised (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for the human SR-B1 (Hs00969821_m1), ABCA1 (Hs01059101_m1), and ABCG1 (Hs00245154_m1) genes, with beta actin (Hs99999903_m1) serving as the housekeeping gene. The data were presented as a ratio of the target gene mRNA to the mRNA of the housekeeping gene.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables that followed normal distribution (according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while asymmetrically distributed variables were shown as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were presented as relative frequencies and compared using the Chi-squared test. Differences between asymmetrically distributed data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test. Longitudinal changes throughout the trimesters were analyzed by the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with post-hoc Bonferroni correction, for normally distributed variables, and the Friedman test (non-parametric repeated-measures ANOVA) with Wilcoxon post-hoc test and Bonferroni correction, for these with the asymmetric distribution. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to examine the presence of associations between the analyzed parameters. The results were presented as Spearman’s correlation coefficient and 95% confidence interval, which was calculated using the bootstrap method. Correlations in which the confidence interval did not contain 0 were considered statistically significant.

Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for principal analyses. P values for post-hoc analyses were determined according to Bonferroni correction. Statistical analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics 18 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethics considerations.

References

Champion, M. L. & Harper, L. M. Gestational weight gain: Update on outcomes and interventions. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 20, 1–10 (2020).

Langley-Evans, S. C., Pearce, J. & Ellis, S. Overweight, obesity and excessive weight gain in pregnancy as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A narrative review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 35, 250–264 (2022).

Weight Gain during Pregnancy. American College of obstetricians and gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion No. 548. Obstet. Gynecol. 121, 210–212 (2013).

Stadler, J. T. et al. Obesity affects HDL metabolism composition and subclass distribution. Biomedicines. 9, 242 (2021).

Darabi, M. & Kontush, A. High-density lipoproteins (HDL) novel function and therapeutic applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1867, 159058 (2022).

Boyce, G., Button, E., Soo, S. & Wellington, C. The pleiotropic vasoprotective functions of high density lipoproteins (HDL). J. Biomed. Res. 32, 164 (2018).

Scifres, C. M., Catov, J. M. & Simhan, H. N. The impact of maternal obesity and gestational weight gain on early and mid-pregnancy lipid profiles. J. Obes. 22, 932–938 (2014).

Wild, R., & Feingold, K. R. Effect of pregnancy on lipid metabolism and lipoprotein levels in Endotext (ed. Feingold, K.R. et al., eds.) (MDText.com, Inc., 2023).

Woollett, L. A., Catov, J. M. & Jones, H. N. Roles of maternal HDL during pregnancy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1867, 159106 (2022).

Vladimirov, S. et al. Can non-cholesterol sterols indicate the presence of specific dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism in patients with colorectal cancer?. Biochem. Pharmacol. 196, 114595 (2022).

Mashnafi, S., Plat, J., Mensink, R. P. & Baumgartner, S. Non-cholesterol sterol concentrations as biomarkers for cholesterol absorption and synthesis in different metabolic disorders: a systematic review. J. Nutr. 11, 124 (2019).

Zeljkovic, A. et al. Changes in LDL and HDL subclasses in normal pregnancy and associations with birth weight, birth length and head circumference. Matern. Child Health J. 17, 556–565 (2013).

Huang, D. et al. Association of maternal HDL2-c concentration in the first trimester and the risk of large for gestational age birth. Lipids Health Dis. 21, 71 (2022).

Vekic, J., Stefanovic, A. & Zeljkovic, A. Obesity and dyslipidemia: a review of current evidence. Curr. Obes. Rep. 12, 207–222 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. High-density lipoprotein subclasses and their role in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: A narrative review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 7856 (2024).

Du, X. M. et al. HDL particle size is a critical determinant of ABCA1-mediated macrophage cellular cholesterol export. Circ. Res. 116, 1133–1142 (2015).

Trajkovska, K. T. & Topuzovska, S. High-density lipoprotein metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport: Strategies for raising HDL cholesterol. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 18, 149 (2017).

Shen, W. J., Asthana, S., Kraemer, F. B. & Azhar, S. Scavenger receptor B type 1: Expression, molecular regulation, and cholesterol transport function. J. Lipid Res. 59, 1114–1131 (2018).

May, S. C. & Sahoo, D. A short amphipathic alpha helix in scavenger receptor BI facilitates bidirectional HDL-cholesterol transport. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102333 (2022).

Tall, A. R., Yvan-Charvet, L., Terasaka, N., Pagler, T. & Wang, N. HDL, ABC transporters, and cholesterol efflux: implications for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 7, 365–375 (2008).

Perichart-Perera, O. et al. Metabolic markers during pregnancy and their association with maternal and newborn weight status. PLoS One. 12, e0180874 (2017).

Hong, B. V., Zheng, J. & Zivkovic, A. M. HDL function across the lifespan: from childhood, to pregnancy, to old age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 15305 (2023).

Derikonjic, M. et al. The effects of pregestational overweight and obesity on maternal lipidome in pregnancy: Implications for newborns’ characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 7449 (2024).

Lu, Y. et al. Establishment of trimester-specific reference intervals of serum lipids and the associations with pregnancy complications and adverse perinatal outcomes: A population-based prospective study. Ann. Med. 53, 1632–1641 (2021).

Adank, M. C. et al. Is maternal lipid profile in early pregnancy associated with pregnancy complications and blood pressure in pregnancy and long term postpartum?. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 221, 150-e1 (2019).

Yamauchi, Y., Yokoyama, S. & Chang, T. Y. ABCA1-dependent sterol release: sterol molecule specificity and potential membrane domain for HDL biogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 57, 77–88 (2016).

Shen, M. et al. Phytosterols: Physiological functions and potential application. Foods. 13, 1754 (2024).

Zeljkovic, A., Stefanovic, A., Vekic, J. Exploration of HDL-ome During Pregnancy: A Way to Improve Maternal and Child Health in Integrated Science for Sustainable Development Goal 3 (ed. Rezaei, N.) (Springer, Cham 2024).

Beazer, J. D. & Freeman, D. J. Estradiol and HDL function in women–a partnership for life. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107, e2192–e2194 (2022).

Davidson, W. S. et al. Obesity is associated with an altered HDL subspecies profile among adolescents with metabolic disease [S]. J. Lipid Res. 58, 1916–1923 (2017).

Blagojevic, I. M. P. et al. Overweight and obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: association with inflammation, oxidative stress and dyslipidaemia. Br. J. Nutr. 128, 604–612 (2022).

Dergunov, A. D. & Baserova, V. B. Different pathways of cellular cholesterol efflux. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 80, 471–481 (2022).

Formisano, E. et al. Characteristics, physiopathology and management of dyslipidemias in pregnancy: A narrative review. J. Nutr. 16, 2927 (2024).

Günther, V. et al. Impact of nicotine and maternal BMI on fetal birth weight. BMC pregnancy childbirth. 21, 1–6 (2021).

Lewandowska, M. Maternal obesity and risk of low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and macrosomia: multiple analyses. J. Nutr. 13, 1213 (2021).

Parveen, T., Hameed, F. & Kahn, J. A. The impact of maternal obesity on neonatal Apgar score and neonatal intensive care unit admissions in a tertiary care hospital. J. Surg. Pak. 34, 161–165 (2018).

Horne, H. et al. Maternal-fetal cholesterol transfer in human term pregnancies. Placenta. 87, 23–29 (2019).

Godfrey, K. M. et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5, 53–64 (2017).

Kankowski, L. et al. The impact of maternal obesity on offspring cardiovascular health: A systematic literature review. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 868441 (2022).

Roland, M. C. P., Godang, K., Aukrust, P., Henriksen, T. & Lekva, T. Low CETP activity and unique composition of large VLDL and small HDL in women giving birth to small-for-gestational age infants. Sci. Rep. 11, 6213 (2021).

Cheng-Mao, X. et al. Placental ABCA1 expression is increased in spontaneous preterm deliveries compared with iatrogenic preterm deliveries and term deliveries. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 8248094 (2017).

He, B. M., Zhao, S. P. & Peng, Z. Y. Effects of cigarette smoking on HDL quantity and function: implications for atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Biochem. 114, 2431–2436 (2013).

Salihu, H. M. & Wilson, R. E. Epidemiology of prenatal smoking and perinatal outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 83, 713–720 (2007).

Lim, J. U. et al. Comparison of world health organization and Asia-pacific body mass index classifications in COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon. Dis. 12, 2465–2475 (2017).

Cnattingius, S. et al. Apgar score components at 5 minutes: Risks and prediction of neonatal mortality. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 31, 328–337 (2017).

Vladimirov, S., Gojković, T., Zeljković, A., Jelić-Ivanović, Z. & Spasojević-Kalimanovska, V. Determination of non-cholesterol sterols in serum and HDL fraction by LC/MS-MS: Significance of matrix-related interferences. J. Med. Biochem. 39, 299 (2020).

Zeljkovic, A. et al. Does simultaneous determination of LDL and HDL particle size improve prediction of coronary artery disease risk?. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 109–116 (2008).

Funding

This work was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 7741659, HIgh-density lipoprotein MetabolOMe research to improve pregnancy outcome—HI-MOM). The authors appreciate support from the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation, Republic of Serbia (Grant Agreement with University of Belgrade-Faculty of Pharmacy No: 451–03-65/2024–03/ 200161 and No: 451–03-66/2024–03/ 200161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.Z.; methodology, M.D., M.S.M., J.M., T.A., M.M., M.M.T. and J.I.; validation, T.A.; formal analysis, M.D., J.V. and A.Z.; resources, D.A., M.S., T.G. and Z.M.; data curation, J.M. and S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and J.V.; visualization, M.D.; supervision, A.S., J.V., N.B.S. and A.Z.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Derikonjic, M., Vekic, J., Stefanovic, A. et al. Associations of excessive gestational weight gain with changes in components of maternal reverse cholesterol transport and neonatal outcomes. Sci Rep 15, 5716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90168-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90168-z