Abstract

This cross-sectional study examined the knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) of training of vascular access in chronic hemodialysis patients among nephrology fellows in Southwest China. Nephrology fellows in Southwest China were recruited from June 1st to 10th, 2024. The demographic characteristics and KAP scores were determined using a self-designed questionnaire. Finally, 210 valid questionnaires were included. Among the participants, 37.6% were 36–40 years old, and 54.3% were females. The median knowledge, attitude, and practice scores were 19 (IQR: 17–20) (possible maximum of 20), 36 (IQR: 35–37) (possible maximum of 50), and 46 (IQR: 38–60) (possible maximum of 80), respectively. Knowledge and attitudes were correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.439, P < 0.001), as well as knowledge and practice (r = 0.645, P < 0.001) and attitudes and practice (r = 0.560, P < 0.001). Mediation analysis showed that the knowledge scores (β = 0.266, P < 0.001), attitude scores (β = 0.268, P < 0.001), gender (β=-0.149, P = 0.001), nephrology experience (β = 0.135, P = 0.005), and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=-0.374, P < 0.001) had direct influences on practice, while the knowledge scores (β = 0.130, P < 0.001), professional background (β=-0.186, P < 0.001), and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=-0.070, P = 0.006) had indirect influences on practice. The study indicated that nephrology fellows in Southwest China had good vascular access knowledge but moderate attitudes and practices. Specific areas would require training to improve the practice of vascular access for patients requiring maintenance hemodialysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a significant worldwide public health crisis that affects about 10% of the global population1 and 10.8% of the Chinese population, reaching 18.3% in Southwest China2. Age and related comorbidities (e.g., type 2 diabetes mellitus) are the major risk factors for CKD2,3. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) necessitates renal replacement therapies (RRTs) such as peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, and kidney transplantation4,5. Globally, hemodialysis is the predominant RRT method (80–90% of cases), while peritoneal dialysis accounts for 10–20%6. In patients requiring hemodialysis, establishing vascular access is crucial, as it directly impacts the effectiveness and safety of hemodialysis7,8,9, and the adequacy and sufficient amount of hemodialysis are critical determinants of patient outcomes10,11. Establishing vascular access requires training, knowledge, experience, and skills to ensure optimal hemodialysis outcomes12,13. Therefore, understanding the nephrologists’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward vascular access is vital for improving patient treatment quality and healthcare standards.

The KAP methodology involves a structured survey to examine participants’ KAP toward a particular subject through questionnaires. The KAP methodology helps identify issues, misconceptions, misunderstandings, and knowledge gaps and provides a basis for optimizing health education and training to improve disease management strategies14,15. Despite the undeniable importance of vascular access in nephrology7,8,9, several challenges remain regarding establishing vascular access and long-term access patency9,16,17. In addition, previous studies suggested that physicians and other healthcare providers involved in hemodialysis may lack adequate knowledge about vascular access may exhibit deviations from guidelines, and have non-standard practices18,19,20,21,22,23. Southwest China exhibits a high prevalence of CKD, but there is relatively little data about the KAP of nephrology fellows toward vascular access training. Thus, it is necessary to conduct a survey to determine the KAP of nephrology fellows in this region to understand their knowledge of vascular access, explore potential problems, and propose improvements to optimize their training. Such improvements could result in nephrologists with optimal practice of vascular access early in their career, ultimately improving the quality of CKD management.

In China, the duration of nephrology training is usually divided into 3-, 6-, or 12-month programs. The training is open to any healthcare provider who wishes to specialize in nephrology. Hence, the aim of this study was to investigate the KAP levels of nephrology fellows in Southwest China regarding vascular access. This study sought to provide references and recommendations to enhance nephrologists’ knowledge and practice of the quality of vascular access.

Methods

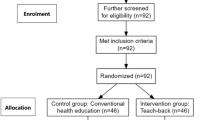

Study design and participants

Nephrology fellows in Southwest China were recruited in this cross-sectional study from June 1st to 10th, 2024. The inclusion criteria were (1) age ≥ 18 years, (2) training fellows (physicians) in medical institutions in Southwest China, and (3) undergoing nephrology training. This work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No. 291 of 2024). All participants were informed about the study protocol and provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Questionnaire introduction

The questionnaire was designed by the investigators according to the Chinese expert consensus on vascular access for hemodialysis (2nd edition). It was revised according to the suggestions of two nephrology experts to ensure content validity. The questionnaire was pilot-tested with 31 participants, yielding a Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient of 0.949, indicating good internal consistency. The final questionnaire was in Chinese (an English translation was attached as an Appendix) and consisted of four sections: demographics, knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The knowledge section included 10 questions scored 2 points for very familiar, 1 point for heard of, and 0 points for unclear, with a total score range of 0–20. The attitude section comprised 10 questions scored using a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (5 points)), with a total score range of 10–50. The practice section consisted of 16 questions scored using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from always (5 points) to never (1 point), with a total score ranging from 16 to 80. In the formal survey, the overall scale and subscales demonstrated good internal consistency. Cronbach’s α was 0.934, with the knowledge, attitude, and practice sections having coefficients of 0.831, 0.675, and 0.945, respectively. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value for the overall scale was 0.907.

Questionnaire distribution and data collection

An electronic questionnaire was generated using Wenjuanxing (Questionnaire Star). The WeChat groups of the nephrology educational institutions were used to distribute the questionnaire. The first page was the informed consent form, and its electronic signature was mandatory for accessing the survey itself. A given IP address was allowed to submit only one survey. Responses to all items were mandatory for submission. The participants were not given a strict timeframe to complete the questionnaire; they were instructed to complete it without stopping or pausing and to refrain from consulting any sources of knowledge. Based on the average reading speed of Chinese characters in native Chinese individuals, surveys that took < 120 s or > 8 min to complete were excluded. It was to minimize the possibility of a participant searching for the correct answers on the Internet or to avoid the participants answering in multiple bouts, which could introduce bias. There were 36 KAP items and 10 demographic items. Surveys with logical errors (e.g., impossible age) or completed using the same option for all KAP items were also excluded.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the distribution of the continuous variables. Continuous data with a normal distribution were presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs) and tested using Student’s t-test (two groups) or ANOVA (three or more groups). Continuous data with a non-normal distribution were presented as medians (25th −75th percentile) and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test (two groups) or the Kruskall-Wallis H-test (three or more groups). Categorical were presented as n (%) and analyzed using the chi-squared test. Correlations between dimension scores were assessed using the Pearson test if data were normally distributed and the Spearman test if not. P-values were retained to three decimal places, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using R 4.3.2 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, www.r-project.org).

Based on the KAP theoretical framework, a structural equation model (SEM) analysis was performed to verify whether attitudes mediated the relationship between knowledge and practice behaviors. Indirect and direct effects were calculated and compared. The model fit indices were root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) < 0.08, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.8, and comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.8. If these thresholds were not met, path analysis was applied to test for mediation effects. Stata 18.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the path analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 210 valid questionnaires were collected. The highest frequencies for each variable were age 36–40 years old (37.6%), female gender (54.3%), bachelor’s degree or below (80.0%), intermediate title (53.3%), working in nephrology (94.8%), ≥ 11 years of experience in nephrology (40.0%), 0.5–1 year of training in nephrology (48.6%), working in public tertiary hospitals (57.6%), and had a history of performing or leading vascular access-related procedures (56.7%) (Table 1).

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices dimensions

The median KAP scores were 19 (IQR: 17–20) (possible maximum of 20), 36 (IQR: 35–37) (possible maximum of 50), and 46 (IQR: 38–60) (possible maximum of 80). The greatest knowledge scores were observed in age 36–40 (P < 0.001), associate senior or above titles (P = 0.003), nephrology background (P < 0.001), ≥ 6 years of work experience in nephrology (P < 0.001), > 1 year of training in nephrology (P = 0.039), and with experience of leading vascular access (P < 0.001). The greatest attitude scores were observed in males (P = 0.009), with a nephrology background (P < 0.001), ≥ 6 years of work experience in nephrology (P = 0.001), and with experience of performing or leading vascular access (P < 0.001). The greatest practice scores were seen in males (P < 0.001), age 36–40 (P < 0.001), associate senior or above titles (P < 0.001), nephrology background (P < 0.001), > 11 years of work experience in nephrology (P < 0.001), > 1 year of training in nephrology (P < 0.001), public tertiary hospital (P = 0.018), and with experience of performing or lading vascular access (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Among the knowledge items, the highest score was observed for K1 (97.6%, “The preferred choice for long-term vascular access should be autogenous arteriovenous fistula (AVF)”), while the lowest score was observed for K9 (39.5%), “Are you aware of recent research or guidelines regarding vascular access in nephrology?”) (Table S1). The details of the attitude and practice dimensions are also shown in Table S1. Figures 1, 2 and 3 present the distribution of the responses to the KAP questionnaire items.

Distribution of the responses to the knowledge items. K1. The preferred choice for long-term vascular access should be autogenous arteriovenous fistula (AVF). K2. When autogenous AVF cannot be established, the next choice should be arteriovenous graft (AVG), and tunnelled cuffed catheter (TCC) with a cuff and polyester sleeve should be the last resort. K3. Vascular access should follow the principle of “fistula first” to reduce unnecessary central venous catheter (CVC) use. K4. For the location selection of arteriovenous fistula, the principle is upper limb before lower limb; distal end before proximal end; non-dominant side before dominant side. K5. Monitoring of access blood flow includes duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, and pulsed Doppler ultrasound with variable speed flow. K6. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is the gold standard for diagnosing vascular stenosis in autogenous AVF. K7. Intervention is needed when the local stenosis rate exceeds 50% of the nearby normal vessel diameter and is accompanied by the following conditions: natural blood flow of the fistula is < 500 ml/min; cannot meet the required blood flow for dialysis prescription; increased dialysis venous pressure; difficult puncture; decreased adequacy of dialysis; and abnormal signs of the fistula. K8. Assess cardiac function through symptoms, signs, and echocardiography. Patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30% are not recommended for fistula formation surgery. K9. Are you aware of recent research or guidelines regarding vascular access in nephrology? K10. Before fistula surgery, it is necessary to assess the anatomical structure, vascular continuity, and dilatation of the vessels.

Distribution of the responses to the attitude items. A1. I believe that the choice of vascular access plays a crucial role in a patient’s treatment plan. A2. I believe that a thorough understanding of vascular access-related knowledge during training is essential for enhancing the overall quality of nephrology physicians. A3. I have sufficient confidence and ability to manage complications related to vascular access. A4. I believe that nephrology physicians should actively participate in research and clinical practice related to vascular access to improve patient treatment outcomes. A5. I am willing to share and exchange my experiences and insights in vascular access management with other medical colleagues. A6. I believe that patients’ understanding of and compliance with vascular access will affect the effectiveness of treatment. A7. Managing vascular access presents certain difficulties and challenges for me. A8. I believe that current clinical training on vascular access is inadequate. A9. Do you support the development of more detailed and personalized guidelines for vascular access management to improve the individualized treatment of patients? A10. Compared to traditional teaching methods, do you believe that teaching about vascular access needs to adopt more flexible teaching methods (such as group discussion, problem-based learning, case-based teaching, etc.)?.

Distribution of the responses to the practice items. P1. Do you often study the latest research or guidelines on vascular access in nephrology? P2. Do you actively seek out the latest information and techniques regarding vascular access in nephrology patients? P3.1 Can you independently perform arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation? P3.2 Can you independently perform AVF revision? P3.3 Can you independently perform arteriovenous graft (AVG) placement? P3.4 Can you independently perform placement/replacement of temporary deep vein catheters for hemodialysis? P3.5 Can you independently perform placement/replacement of semi-permanent deep vein catheters for hemodialysis? P3.6 Can you independently perform balloon angioplasty for AVF (under interventional or ultrasound guidance)? P4.1 Do you have knowledge of vascular intervention related to vascular access? P4.2 Do you have knowledge of ultrasound related to vascular access? P5. Do you often collaborate with other healthcare professionals in the team to develop and implement vascular access management plans for patients? P6. Can you assess and manage fistula maturity and complications effectively? P7. When dealing with complex cases, do you always consider using the most advanced methods of vascular access management? P8. Do you frequently perform vascular access-related surgeries or procedures, such as AVF creation or repair? P9. In your daily clinical practice, do you always encourage patients to actively participate in and manage their vascular access care? P10. Do you perform vascular access examination on patients as part of routine vascular access monitoring?.

Pearson correlation analysis

Knowledge and attitude were correlated (r = 0.439, P < 0.001), as well as knowledge and practice (r = 0.645, P < 0.001) and attitude and practice (r = 0.560, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis showed that the job title (β = 0.116, P = 0.046), professional background (β=−0.471, P < 0.001), and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=−0.178, P = 0.003) had direct influences on knowledge. The knowledge scores (β = 0.484, P < 0.001) had a direct effect on attitude, while the professional background (β=−0.228, P < 0.001) and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=−0.086, P = 0.006) had indirect influences on attitude. The knowledge scores (β = 0.266, P < 0.001), attitude scores (β = 0.268, P < 0.001), gender (β=−0.149, P = 0.001), nephrology working experience (β = 0.135, P = 0.005), and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=−0.374, P < 0.001) had direct influences on practice, while the knowledge scores (β = 0.130, P < 0.001), professional background (β=−0.186, P < 0.001), and experience of leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure (β=−0.070, P = 0.006) had indirect influences on practice (Fig. 4 and Table 3). The model had a good fit (Table S2).

Mediation analysis. “Jobtitle” refers to the professional title; “major” refers to the professional background; “experience” indicates the working experience in nephrology; “leadsurgery” means having experience in leading a vascular access-related surgery or procedure, signifying the ability to independently perform vascular access surgeries. The arrow originates from the factor influencing the factor pointed by the arrow. The numbers besides the arrows are the β coefficients. The rectangles are the observed variables. The circles are latent (or unobserved) variables that are included in the model to improve the fit. The numbers in the boxes are the variable weight.

Discussion

This study investigated the KAP of vascular access among nephrology fellows in Southwest China. The results suggested that they had good knowledge of vascular access but moderate attitudes and practices. Specific areas would require training to improve the practice of vascular access in patients requiring hemodialysis. Improving the KAP toward vascular access could translate into better vascular access outcomes.

In the questionnaire, “vascular access-related surgery or procedure” refers to the establishment of temporary/long-term dialysis access, such as autogenous arteriovenous fistula (AVF), arteriovenous graft (AVG), tunnel-cuffed catheter (TCC), non-cuffed catheter (NCC), etc. In China, most dialysis-related vascular access surgeries are performed by nephrologists, with a small proportion carried out by vascular surgeons, reflecting the healthcare context in China as the “Expert Consensus on Vascular Access for Hemodialysis in China” was mainly from nephrologists24. The present study revealed good knowledge of vascular access among the participants. Previous KAP studies on vascular access revealed rather moderate knowledge19,20,21,22,23, but it must be noted that the only studies available were performed in nurses of different curricula, while the present study was performed in physicians. Indeed, vascular access for hemodialysis requires operation and functional assessment, which is reserved in most countries for physicians and not nurses. The present study included only physicians and showed that having participated in vascular access was associated with higher knowledge, probably due to experience and knowledge gained while actually performing the procedure. In this study, the knowledge items with the lowest scores were about the monitoring of the vascular access patency and awareness of recent guidelines in nephrology, highlighting the need to train nephrology fellows about these points. Previous studies already advocated the need for specialized training on vascular access in dialysis departments7,12,25. Training on such aspects, especially the guidelines, would be required. A specific course could be dedicated to the guidelines, including monitoring the vascular access patency. Continuing education should also be undertaken to train healthcare providers working in nephrology about the latest guidelines and their revisions.

The attitude and practice scores were moderate. Indeed, it has been reported that healthcare providers involved in hemodialysis may exhibit deviations from guidelines and have non-standard practices18,19,20,21,22,23, supporting the present study. The adequate practice of vascular access is necessary to ensure optimal dialysis outcomes7,8,9. The mediation analysis also showed that the professional background and participation in vascular access influenced attitudes, possibly for the same reasons as knowledge. A previous study showed that the professional category, knowledge, and experience influenced dialysis practice quality, but the study focused on using unfractionated heparin26. It has been reported that the barriers to implementing acute kidney injury management in China were inadequate knowledge and training, the absence of clinical protocols, and suboptimal multidisciplinary cooperation27, supported by studies performed in other countries28. Of note, in the present study, the participants exhibited low confidence in managing the complications of vascular access, declared having challenges in managing vascular access, and considered that their actual training was inadequate. Regarding practice, most participants declared being unable to perform or revise arteriovenous fistula or arteriovenous grafts, placing semi-permanent catheters, and performing balloon angioplasty. Surprisingly, only 70% of people strongly agree to share experiences with others. The present study does not have the data to determine why such a low percentage was observed. Still, it could be hypothesized that the participants felt that they did not have time to teach others among their professional and academic responsibilities. Another possible explanation could be that as fellowship trainees, they did not feel adequate or they felt too inexperienced to share their experience with others.

The present study had limitations. It was carried out in a single area in China, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The design was cross-sectional, providing only a snapshot of the KAP condition in time and preventing the observation of eventual changes in KAP with changes in training. Nevertheless, the results could constitute a historical baseline for a future evaluation of training activities. In addition, cross-sectional data cannot be used to determine causality. Nevertheless, a SEM analysis was used to provide a surrogate of causality, but the results must be interpreted cautiously because causality was statistically inferred rather than observed29,30,31. Finally, all survey studies are at risk of social desirability bias32,33.

Conclusion

In conclusion, nephrology fellows in Southwest China have good knowledge of vascular access but moderate attitudes and practices. Specific knowledge areas will require additional training in the future, especially regarding the monitoring of vascular access patency and awareness of recent guidelines in nephrology. The training curriculum could be adjusted to cover those areas, and continuing education should be offered. Improving the KAP toward vascular access could translate into better vascular access outcomes for the patients. A future study could examine the KAP toward vascular access in relation to vascular access outcomes.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and supplementary information files.

References

Jadoul, M., Aoun, M. & Masimango Imani, M. The major global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet Glob Health. 12, e342–e343 (2024).

Webster, A. C., Nagler, E. V., Morton, R. L. & Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease Lancet 389, 1238–1252 (2017).

Romagnani, P. et al. Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 17088 (2017).

National Kidney, F. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for Hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 66, 884–930 (2015).

Teitelbaum, I. Peritoneal Dialysis. N Engl. J. Med. 385, 1786–1795 (2021).

Bello, A. K. et al. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 378–395 (2022).

Lok, C. E. et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75, S1–S164 (2020).

Vachharajani, T. J., Taliercio, J. J. & Anvari, E. New devices and technologies for Hemodialysis vascular access: A review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 78, 116–124 (2021).

Lawson, J. H., Niklason, L. E. & Roy-Chaudhury, P. Challenges and novel therapies for vascular access in haemodialysis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 586–602 (2020).

Mutevelic, A., Spanja, I., Sultic-Lavic, I. & Koric, A. The impact of vascular access on the adequacy of Dialysis and the outcome of the Dialysis treatment: one center experience. Mater. Sociomed. 27, 114–117 (2015).

Murdeshwar, H. N., Anjum, F. & Hemodialysis StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Fatima Anjum declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.2024.

Zhang, H. et al. Expert consensus on the establishment and maintenance of native arteriovenous fistula. Chronic Dis. Transl Med. 7, 235–253 (2021).

Murea, M. & Woo, K. New frontiers in vascular access practice: from standardized to Patient-tailored care and shared decision making. Kidney360 2, 1380–1389 (2021).

Andrade, C., Menon, V., Ameen, S. & Kumar Praharaj, S. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in psychiatry: practical guidance. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42, 478–481 (2020).

World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596176_eng.pdf. Accessed November 22, 20222008.

Salah, D. M. et al. Vascular access challenges in Hemodialysis children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 50, 11 (2024).

Alnahhal, K. I., Rowse, J. & Kirksey, L. The challenging surgical vascular access creation. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 13, 162–172 (2023).

Shamasneh, A. O., Atieh, A. S., Gharaibeh, K. A. & Hamadah, A. Perceived barriers and attitudes toward arteriovenous fistula creation and use in Hemodialysis patients in Palestine. Ren. Fail. 42, 343–349 (2020).

Malekshahi, M., Razi, A. R. & Abdullahi, S. R. Evaluation of knowledge and attitude of physicians, nurses, and patients regarding the importance of protection of vascular access in patients undergoing Hemodialysis and its prognostic role. Med. Rep. 6, 100036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hmedic.2024.100036 (2024).

Alsolami, E. & Alobaidi, S. Hemodialysis nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and practices in managing vascular access: A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Med. (Baltim). 103, e37310 (2024).

Chen, J., Lu, J., Fu, X. & Zhou, H. The knowledge, attitudes, and practices of arteriovenous access assessment among Hemodialysis nurses: A multicenter cross-sectional survey. Hemodial. Int. 28(3), 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/hdi.13160IF (2024).

Huang, S. & Liu, D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward arteriovenous fistulas for Hemodialysis among nurses. J. Vasc. Access. 26(2), 608–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/11297298241230110 (2025).

Meng, L., Guo, W., Lou, L., Teo, B. W. & Ho, P. Dialysis nurses’ knowledge, attitude, practice and self-efficacy regarding vascular access: A cross-sectional study in Singapore. J. Vasc. Access. 25(5), 1432–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/11297298231162766 (2024).

Vascular Access Working Group of Blood Purification Center Branch of Chinese Hospital Association. Expert consensus on vascular access for Hemodialysis in China (2nd edition)(in Chinese). Chin. J. Blood Purif. 18, 365–381 (2019).

Chen, H., Chen, L., Zhang, Y., Shi, M. & Zhang, X. Knowledge of vascular access among Hemodialysis unit nurses and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 11, 3494–3502 (2022).

Ockhuis, D. & Kyriacos, U. Renal unit practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and practice regarding the safety of unfractionated heparin for chronic haemodialysis. Curationis 38(1), 1447. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v38i1.1447 (2015).

Wu, Y. et al. Attitudes and practices of Chinese physicians regarding chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury management: a questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey in secondary and tertiary hospitals. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 50, 2037–2042 (2018).

Lameire, N. H. et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet 382, 170–179 (2013).

Beran, T. N. & Violato, C. Structural equation modeling in medical research: a primer. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 267 (2010).

Fan, Y., Chen, J. & Shirkey, G. Applications of structural equation modeling (SEM) in ecological studies: an updated review. Ecol. Process. 5, 19 (2016).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Fifth Edition) (The Guilford Press, 2023).

Bergen, N. & Labonte, R. Everything is perfect, and we have no problems: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792 (2020).

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A. & Tobin, K. E. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict. Behav. 73, 133–136 (2017).

Acknowledgements

First of all, I would like to give my heartfelt thanks to all the people who participated in this survey and this paper. I am also extremely grateful to all my workmates who have kindly provided me with assistance while I was preparing this paper. Finally, I am really grateful to all those who devoted much time to reading this thesis and gave me much advice, which will benefit me in my later studies.

Funding

This study was funded by the Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital Young Talent Fund (2022QN61). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yaling Zhang and Ming Li carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Yaling Zhang and Qiang He performed the statistical analysis and participated in its design. Yaling Zhang、Xingyu Chen and Hao Huang participated in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No. 291 of 2024). All participants were informed about the study protocol and provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., He, Q., Chen, X. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward training of vascular access in chronic hemodialysis patients among nephrology fellows in Southwest China. Sci Rep 15, 9997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94513-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94513-0