Abstract

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolour (L.) Moench) grown under rain-fed conditions is usually affected by drought stress at different stages, resulting in reduced yield. Determining the genetic control of root system architecture (RSA) in plants via multi-locus genome-wide association study (GWAS) is very important to improve moisture stress resistance in sorghum. The objective of this study was, therefore, to identify genomic regions underlying RSA traits in sorghum at the early growth stage among 200 genotypes. A total of 124 QTNs were identified on all chromosomes that are significantly linked with the nine root and shoot traits using one or more of the six ML-GWAS models, with a LOD score threshold of ≥ 3. Among these identified QTNs, a total of 38 significant QTNs were identified in at least two ML-GWAS models. Out of the 38 detected QTNs, 28 were co-located with previously reported QTLs for the RSA, while the remaining 10 QTNs were distinct. We identified 438 co-localized genes within a 65 kb window upstream and downstream of 38 QTNs for studied traits. Among these genes, 153 were uncharacterized or unknown while the rest of the genes have protein description. Moreover, 16 genes contained the QTNs intergenic region of within the gene’s sequences. These genes may regulate root development in the seedling stage. Further analysis on these genes might be important to explore the genetic structure of RSA of sorghum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] belongs to family Poaceae with chromosome number of 2n = 2 × 10 = 20. Sorghum arundinaceum is the most likely progenitor of sorghum, a multifaceted wild species originate in tropical Africa6. It is the world’s fifth most essential cereal crop in terms of total production and acreage with 40.25 million ha under farming and 58.7 million MT of grain production7. Sorghum, a main crop in several arid and semi-arid regions and faces several ecological challenges. It has acquired adaptive traits, including well-developed root systems, which enable it to thrive in these challenging environments.

Root systems, the buried foundation of plants, play a critical role in their growth, development, and resilience to environmental hassles, mainly drought8. The architecture of these underground structures, including traits like root length, angle, number, and dry weight, significantly effects a plant’s capacity to get water and nutrients from the soil9. Sorghum, a main crop in many regions, is progressively renowned for its drought tolerance, making it a valuable model for studying root system architecture10. Sorghum’s capacity to thrive in arid environments is partway attributed to its well-developed root system11. Breeding strategies to improve its drought tolerance and yield potential can be developed by scientists with deep understanding of the genetic basis of root system architecture (RSA) in sorghum1213. Similar finding can also contribute to the development of more resilient cultivars for other crops facing similar challenges.

Genome wide Association Study (GWAS) can pinpoint specific regions of the genome that contribute to phenotypic differences by analyzing the genetic variation in a large population of individuals14. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have appeared as a formidable tool for identifying genetic variants related with complex descriptor like RSA. These findings typically include scanning the entire genome for millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to find those that are statistically correlated with a specific descriptor. Recently, multi-locus GWAS concurrently considers the effects of multiple SNPs on a trait. This methodology can improve statistical power and provide a more inclusive understanding of the genetic architecture of complex descriptor. Several studies undertaking GWAS studies with both single and multi-locus in sorghum12,15,13. They reported in different genomic regions for root descriptors, which shows highly elasticity of the genotype and environment interaction. Different populations may harbor typical genetic variants that affect root traits. Furthermore, the interaction amongst genetic variants may differ across populations, directing to varying root trait phenotypes.

Genotypes that are more resilient to climate change-related stresses, such as drought and flooding can be identified by understanding population-specific genetic variation. RSA is a complex trait controlled by multiple genes, gene interactions, and the genetic basis, although it is very important. Besides to that RSA in sorghum remains relatively unknown. Hence, the fundamental objective of this study was to identify genomic regions underlying RSA traits in sorghum at the early growth stage.

Materials and methods

Genetic materials

This research utilized 200 drought-tolerant germplasms selected from a pool of 400 based on prior drought resistance experiments. These germplasms originated from the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (110 accessions), the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT; 91 accessions), and 13 Ethiopian released varieties. All seeds were obtained from the Melkassa Agricultural Research Center (Supplementary Table S1).

Root phenotyping design and procedure

Root phenotyping was conducted using custom-built root chambers in a randomized block design with three replications, scheduled across two experimental runs for 200 accessions (Supplementary Figure S1). Two consecutive experiments were performed: the first with 150 genotypes and the second with 50 genotypes. From the first experiment, 36 genotypes were selected and included in the second experiment, resulting in a total of 86 genotypes evaluated in the second run. Each experimental unit was replicated three times, while repeated accessions were replicated four times. The phenotyping system is described in detail by Demelash et al.16.

Plant growth conditions and measurements in greenhouse

This research employed the root chamber method in greenhouse conditions, as described by Demelash et al.16. The greenhouse temperature fluctuated between 16 °C (night) and 40 °C. Each chamber was filled with 1100 g of red, clay-textured soil, providing a clear contrast for root image analysis. Before sowing, root chambers were filled to capacity with water and allowed to stand for two days to ensure proper saturation. Seeds were treated with Apron Star 42WS fungicide before planting.

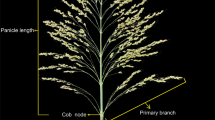

Three seeds were sown vertically at a depth of 3 cm, with the embryo facing downward towards the transparent Perspex (Fig. 1A). Plant moisture was maintained by weekly watering within the root chambers (Fig. 1B). Data collection commenced at the six-leaf stage when the first flush of nodal roots became visible (Fig. 1C and D). Prior to imaging the nodal root angle, shoot length (cm), shoot diameter (mm), and leaf area (cm2) were measured. Shoot length was determined from the soil surface to the ligule of the fifth leaf. Shoot diameter was measured 2 cm above the soil using a digital caliper. Leaf length (LL) and leaf width (LW) were measured for the 3rd, 4th, and 5th leaves. Leaf area was estimated using the formula: LA = LL × LW × 0.69 17. Shoot dry weight (g) was determined by drying fresh seedlings in an oven at 60 °C for 72 h.

After removing one side of the root chamber and the Perspex, the number of nodal roots was counted. The longest nodal root length was measured in centimeters. Root dry weight (g) was determined by oven-drying the roots at 60 °C for 72 h after thorough washing with tap water. The root-to-shoot ratio was calculated by dividing root dry weight by shoot dry weight. Root angles were measured using digital cameras (CANON SX610 HS) connected to two tables via Wi-Fi. Images were captured from both sides of each chamber. Root angle measurements were taken from the first flush of nodal roots, 2 cm from the plant base, relative to the vertical plane. The Opengelphoto software, developed by the University of Queensland18, was used to analyze the images and determine root angles.

Phenotypic data analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done using the procedure general linear model (GLM) using SAS statistical package (SAS, 2002). The ANOVA model for the experiment followed.

\({\text{Y}}{\mathbf{ij}}\,=\,{\text{m}}\,+\,{\text{t}}{\mathbf{i}}\,+\,{\text{bj}}\,+\,{\text{e}}{\mathbf{ij}}\)

Where, Yij = the observation on the jth block and the ith treatment; µ = common mean effect;

τi = effect of treatment i; and βj = effect of block j; and εIj = experiment error for treatments i in Rep j.

The phenotypic traits distribution violin plot was constructed using vioplot V0.5 R package1. Estimation of heritability in broad sense: Broad sense heritability (H2 expressed as the percentage of the ratio of the genotypic variance (σ2g) to the phenotypic variance (σ2p) as described in Allard19 as: h2 = \(\frac{{{\sigma ^2}g}}{{{\sigma ^2}P}}\)

Genome wide association study analysis

Seeds from purified plants were sown in cell trays within a greenhouse at the Melkassa Agricultural Research Center. Three seeds of each genotype were sown per tray. Ten-day-old leaf samples were collected from the three seedlings of each genotype. Pooled leaf samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at -80 °C, and subsequently transported to the Biosciences Eastern and Central Africa - International Livestock Research Institute (BecA-ILRI) hub in Nairobi. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from the frozen tissues using a modified CTAB protocol20. The gDNA samples were subsequently subjected to DNA sequencing through genotyping by sequencing technology using Diversity Arrays Technology Sequence technology.

Marker-trait association analysis was conducted using six ML-GWAS models: factored spectrally transformed multi-locus random-SNP-effect MLM (FASTmrMLM)21, multi-locus random-SNP-effectMLM(mrMLM)22, pLARmEB23, factored spectrally transformed multi-locus random-SNP-effect efficient mixed-model association (FASTmrEMMA)24, pkWmEB25 and iterative sure independence screening EMBayesian LASSO (ISIS EM-BLASSO)26, all of which were implemented in the “mrMLM.GUI)” R package24.

QTNs with a logarithm of the odds (LOD) score of at least 3.0 were considered significantly associated with RSA traits. This threshold corresponds to a p-value of 0.0002, calculated as Pr(χ21 > 3 × 4.61), where 3.0 × ln100 = 3.0 × 4.61 converts the LOD score to its corresponding likelihood ratio test statistic under the null hypothesis, which follows a chi-square distribution with 1 degree of freedom22.

Reliable RSA-associated QTNs were identified as those detected by at least two models. Major QTNs were defined as those detected in two or more models and explaining phenotypic variation (R2) greater than 10%. Kinship was calculated as described by VanRaden27 and included to account for population structure. Log Q-Q plots of p-values were examined to assess the models’ ability to control for population structure and familial relatedness. Manhattan and Q-Q plots were generated using the CMplot V4.5 R package28.

Colocalization with previously detected QTLs for RSA traits and identification of candidate genes

The co-locations of significant QTNs with previously identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) were determined using the Sorghum QTL Atlas database29 within the range of linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay. Candidate genes were identified using Biomart tools30 within the Phytozome website31.

Pairwise LD (r2) values were estimated between 17,637 SNPs across all chromosomes using TASSEL V5 software32. LD decay was plotted as r2 against physical distance (kb) between markers, with a smoothing algorithm applied to visualize the trend developed by Marroni et al.33.

The search was conducted within a 65 kb LD decay distance of the QTN-localized genomic regions in the V3.1 sorghum genome reference34. The average LD decay in core Ethiopian sorghum panel is approximately 65 kb, as reported by Girma et al.35. The SorghumBase online database36 was also consulted for detailed gene descriptions. Significant QTNs identified in intergenic regions were mapped onto the consensus map of sorghum using Mapchart V2.337.

Results

Phenotypic variation

Phenotypic variability analysis of the sorghum accessions revealed significant genetic variation for all four root traits: nodal root angle, nodal root number, root dry weight, and nodal root length (Fig. 2). A wide range of values was observed for these traits (Supplementary Table S2): nodal root angle (14.5° to 27.33°), nodal root number (6.33 to 15.67), nodal root length (40.0 to 72.00 cm), and root dry weight (0.29 to 1.0 g). Similarly, shoot traits exhibited substantial variation among accessions with varying shoot dry weight (0.78 to 2.43 g), shoot length (7.0 to 18.53 cm), leaf area (8.56 to 35.46 cm2), and shoot diameter (2.5 to 5.78 mm). Our analysis revealed high broad-sense heritability for nodal root angle (0.93), root length (0.89), and nodal root number (0.92), but moderate heritability for root dry weight (0.40) (Fig. 2). High heritability was also estimated for all shoot traits.

Violin plot of root and shoot traits distribution and heritability across 200 sorghum accessions at seedling stage: RA = Root angle, RL = Root length, RN = Root number, RDW = Root dry weight, RSR = Root shoot ratio SDW = Shoot dry weight = Root shoot ratio, SFW = Shoot fresh weight, SL = shoot length, LA = Leaf area, SD shoot diameter.

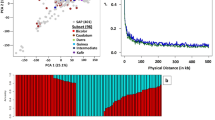

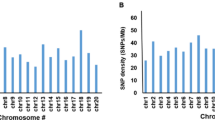

SNP markers and linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay analyses

A total of 21,010 SNP markers were identified across the 200 sorghum accessions. Following exclusion of markers with > 25% missing values, and MAF < 0.01 a subset of 17,637 SNPs was identified and missing values inferred using the Beagle 5.0 software package38. Linkage disequilibrium analysis identified that the LD decays to background levels within 65 kb and r2 = 01 within 30 kb (Fig. 3).

Multi-locus GWAS

Multi-locus models Q–Q plots (Supplementary Figure S2) indicated coherent with optimal trends, inferring that the false-positive errors were controlled well and the results of the MLM model were consistent all traits. All identified QTNs were considered independent loci, as they were physically separated beyond the estimated LD decay distance (65 kb) and showed no significant linkage disequilibrium with one another. This suggests that each QTN represents a distinct genomic region contributing to trait variation. A total of 124 QTNs were identified on all chromosomes that are significantly linked with the nine root and shoot traits using one or more of the six ML-GWAS models, with a LOD score threshold of ≥ 3 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). Among the identified QTNs, the large number was observed for root to shoot ratio, leaf area and shoot length 39, 31, and 30, respectively. While the least number of QTNs were for shoot diameter followed by root dry weight and root angle. Out of the six models involved (Table 1), pKWmEB detected the highest (41 QTNs), followed by pLARmEB (39 QTNs), whereas FASTmrEMMA detected the lowest number of QTNs (12 QTNs). Among 189 QTNs, a total of 38 significant QTNs were identified in at least two ML-GWAS models (Table 2).

Out of the 38 significant markers, three were detected for root angle, two for number of roots, one for root dry weight, and four for root length (Table 2; Fig. 4). Chromosome Chr03 harbored the highest number of QTNs identified (nine QTNs), followed by Chr01 and Chr07 (six QTNs each), and Chr05 (five QTNs) and Chr06 (four QTNs). With one QTN each, chromosomes Chr04, Chr08, and Chr09 had the least number of QTNs detected (Fig. 3). Overall, the LOD value ranged from 3.10 to 10.42, and the proportion of phenotypic variance explained.

Manhattan plot showing p-values and genome-wide associations for root system architecture all traits (A) root angle, (B) root length, (C) root number, (D) root dry weight, (E) shoot dry weight, (F) root to shoot ratio, (G) leaf area, (H) shoot diameter and I) shoot length …. Each marker median of the − log10(p) values from the multi-locus random-SNP-effect mixed linear model (mrMLM), factored spectrally transformed multi-locus random-SNP-effect MLM (FASTmrMLM), and factored spectrally transformed multi-locus random-SNP-effect efficient mixed-model association (FASTmrEMMA) approaches were used to draw the Manhattan. The dots are indicated by light colors quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs); all QTNs commonly identified by three approaches are indicated by pink dots with dotted vertical lines.

Co-location with previously reported root trait QTLs

The genomic locations of the new QTNs identified were compared with previously mapped QTLs for the RSA reported in Sorghum QTL Atlas database29 and recently published GWAS in reference genome V3.112,39,15,13,40. Out of the 38 detected QTNs, 28 were co-located with previously reported QTLs for the RSA, while the remaining 10 QTNs were distinct (Table 3). Particularly, S5_59063690 for root angle co-located with previously reported root angle QTL (QRTAN5.1) by Mace et al.41. This QTN also co-located with previously reported root length studied by Bekele et al.3 and root dry weight studied by Mace et al.41. Similarly, S10_50183939 QTN for root length co-located with previously reported root length QTLs by Bekele et al.3 and Wang et al.42. S1_49944842 root number QTN co-located with previously reported root network surface area QTL studied by Parra-Londono et al.43. Root to shoot ratio QTNs (S3_7815517 and S5_6152059) co-located with previously reported QTLs for root angle and root dry weight studied by Lopez et al.44 and Mace et al.41. Some shoot trait QTNs also co-located with previously reported root trait QTNs (Table 3).

Candidate genes and annotation

We identified 438 co-localized genes within a 65 kb window upstream and downstream of 38 QTNs for studied traits (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4). Among these genes, 153 were uncharacterized or unknown proteins such as co-located with shoot length (39 genes), leaf area (42 genes), root to shoot ratio (19 genes), nodal root length (18 genes), the number of nodal roots (2 genes), nodal root angle (11 genes), and root dry weight (10 genes). The rest of the genes have protein description such as Sobic.001G348900 (serine protease), Sobic.007G012001 (ubiquitin), Sobic.007G012100 (BETA-GALACTOSIDASE) and Sobic.007G011700 (Putative Bile acid beta-glucosidase) for root angle QTNs. Moreover, Sobic.001G331200 (indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase), Sobic.005G145100 (Phospholipase A2), and Sobic.010G170500 (LEUCINE-RICH REPEAT-CONTAINING PROTEIN) for root length. Glycosyltransferase, Sobic.003G105600 and Sobic.005G060000 (No apical meristem (NAM) protein), Sobic.001G242800 (Auxin-induced protein) and more others traits.

A total of 16 QTNs were identified within gene regions across various chromosomes (Fig. 5). For example, on chromosome Chr02, the QTN S2_67930521 was associated with leaf area (LA) in the Sobic.002G303300 gene. Other QTLs were found on Chr03 (S3_67077302, S3_72444802), Chr04 (S4_66946984), Chr05 (S5_6152059), Chr06 (S6_51711752), Chr07 (S7_1078535, S7_1163493), Chr10 (S10_50183939, S10_7405759), and Chr11 (S11_50183939). These QTNs were associated with various traits, including leaf area, root length, root number, root dry weight, and root surface area.

Linkage groups and chromosomal positions of significant quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) and intragenic genes identified for sorghum root system architecture (RSA) traits. The QTNs and genes are labeled on the right side of the chromosomes, and trait name abbreviations display different traits. QTNs and candidate genes on each chromosome are highlighted with different colors.

Discussion

Sorghum is a main crop in dry regions and its yield is significantly influenced by moisture stress. Root architecture plays a critical role in a plant’s ability to adapt to various environmental stresses. The structure, growth patterns, and distribution of roots significantly influence a plant’s access to water, nutrients, and oxygen, as well as its anchorage in the soil. Several early-stage root traits have been shown to be associated with maturity stage and grain yield in sorghum4918. Hence, understanding these traits at early stage and their genetic basis can significantly enhance early breeding programs for sorghum.

This study identification of 189 QTNs across all chromosomes recommends a complex genetic architecture underlying the traits studied. Similarly, several recent studies also revealed QTNs in all ten sorghum chromosomes for root traits12,15,13. The varying number of QTNs associated with different traits highlights the trait-specific nature of genetic control. The uneven distribution of QTNs across chromosomes shows that certain regions of the genome may harbor more genes involved in these traits.

The differences in QTN detection by different MLM models suggest that the choice of model influence the identification of QTNs. pKWmEB and pLARmEB, which incorporate both population structure and kinship information, appear to be more effective in capturing the genetic architecture of these traits. Similarly, Elias et al.12 reported large number of QTNs detected from pLARmEB model in sorghum root traits at seedling stage. However, other study reported different model detection large number of QTN. For example, Kebede et al.15 reported the maximum number of QTNs from mrMLM model for sorghum root traits. This detecting a large number of QTNs in different MLM models across populations suggests a complex genetic architecture influenced by multiple factors, including population-specific genetic variation, environmental interactions, and model sensitivity. By carefully considering these factors and employing appropriate analytical approaches, researchers can gain valuable insights into the genetic basis of complex traits and develop more effective breeding strategies.

The overlap of 38 QTNs across multiple models provides evidence for the reliability of the identified QTNs. Several studies also identified QTNs for root system architecture in sorghum using multiple models. For example, Kebede et al.15 identified 38 QTNs and Elias et al.12 identified 17 QTNs. This suggests that these QTNs are likely to have genuine effects on the traits of interest.

LD decay was estimated within 30 kb at r2 = 0.1 and 65 kb within the background level of threshold. Several studies reported that from 10 kb to 200kb35,45. We used 65 kb LD block for further analysis of previously studied QTLs and co-located genes. The high degree of overlap between the newly identified QTNs and previously reported QTLs for RSA provides strong validation for the findings of this study. Root angle QTN (S5_59063690) co-located with previously reported root angle studied by Mace et al.41. Moreover, this QTN co-located with root length and root dry weight studied by Bekele et al.3 and Mace et al.41, respectively. Additionally, only two genes, namely Sobic.005G137300 and Sobic.005G137400 co-located within the LD decay of up-and down-stream of the QTNs. These two genes reported as protein function similar to Chalcone synthase WHP1 (Sobic.005G137300) and uncharacterized protein (Sobic.005G137400). Chalcone synthase (CHS) is a key enzyme in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway48. While its primary function is to catalyze the first committed step in flavonoid production, it also plays a significant role in root development. Kim et al.50 reported that chalcone synthase expression very sensitively in root by light or water stress which is similar to root developmental patterns in sweet potato roots. Moreover, McKhann and Hirsch46 reported that high levels of Chalcone synthase transcript in root tips and entire young roots. Several studies also reported that this gene play important roles in adapting to abiotic stresses, such as low temperature51, nitrogen deficiency4 and salinity52. Flavonoids produced by CHS can influence root cell differentiation and development47. Some report indicated that this gene interact with signaling pathways involved in root growth, branching, and the formation of specialized root structures53.

The S7_1078535 QTN for root angle was one of unique identified on chromosome 7. This QTN found with the intergenic region of the Sobic.007G011600 gene. This gene protein describes as Splicing factor 1/branch point binding protein// K-homology (KH) type RNA binding proteins. KH domain-containing RNA-binding proteins play significant roles in various aspects of plant growth and development, including root growth54. KH proteins can influence mRNA stability, splicing, and translation55. By binding to specific RNA sequences, they can regulate the levels of key proteins involved in root growth and development5,54. Some KH proteins participate in miRNA biogenesis, affecting the abundance and activity of miRNAs that regulate root development. Certain KH proteins interact with Auxin Response Factors, modulating their activity and thereby influencing auxin-mediated root growth responses5,56. Auxin is a plant hormone that regulates root growth, branching, and gravitropism. Zhang et al.57 described that RNA binding protein highly expression in adventitious roots. These QTNs could represent new targets for breeding programs aimed at improving RSA. Similarly, Elias et al.12 reported that QTN within the gene regions which involving hormones signaling such as auxin and abscisic acid.

Root length QTNs such as S10_50183939 co-located with previously reported QTNs for root length by Bekele et al.3 and Wang et al.42. A total of nine genes co-located around the up-and down-stream regions of these QTNs. However, this QTN found within the sequence of Sobic.010G170500 gene. This gene reported as protein function leucine-rich repeat-containing protein (LRR-CP). LRR-CPs are a large family of proteins characterized by the presence of leucine-rich repeats, which are highly conserved motifs that form helical structures58. These proteins are involved in the perception and response to plant hormones, such as auxin, cytokinin, and gibberellin59. Moreover, Putative auxin-induced protein gene Sobic.007G198100, also co-located with root length QTN (S7_62898522). This QTN (S7_62898522) co-located with previously studied root major ellipse axis and network convex area by Parra-Londono et al.43. These hormones play critical roles in root growth and development60.

Two QTNs identified for root number (S1_49944842 and S6_51711752). S1_49944842 QTN co-located with previously identified root network surface area by Parra-Londono et al.43. Two genes Sobic.001G265300 and Sobic.001G265200 found within the range of LD decay of this QTN. These genes identified as similar to Os08g0199400 protein and hypothetical protein, Sobic.001G265300 and Sobic.001G265200, respectively. S6_51711752 QTN found in intergenic region of Sobic.006G158800 gene. This gene is described as similar to OSJNBa0081C01.23 (neomenthol dehydrogenase / Monoterpenoid dehydrogenase) protein. neomenthol dehydrogenase is a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of terpenes, does not have a direct role in root development61. However, the terpenes they produce can indirectly influence root development through their interactions with the environment and other organisms2.

Only one unique QTN (S7_1163493) identified for root dry weight. This QTN co-located with 21 genes withn LD decay ranges. However, this QTN found in the intergenic region of Sobic.007G012800 gene. This gene characterized as Putative uncharacterized protein. This gene might be a candidate for further improving of root mass.

Significant number of co-located genes (34.9%) were uncharacterized protein. The presence of a significant number of uncharacterized or unknown proteins among the co-localized genes highlights the potential for novel gene discovery and functional characterization. For example, 13 genes (50%) root angle, 22 genes (55%) for root length, 15 genes (78.9%) for root number and 10 genes (47.6%) for root dry weight were uncharacterized protein.

Conclusion

This study gives a comprehensive analysis of the genetic basis of various traits in sorghum. The identified QTNs and co-localized genes offer valuable resources for plant breeding and contribute to our understanding of the genetic architecture of complex traits. The study provides strong evidence for the genetic basis of root system architecture (RSA) in sorghum such as co-location with previously reported QTLs and genes reported for root system architecture. The study contributes to our understanding of the genetic architecture underlying RSA in sorghum, providing valuable insights for future breeding efforts to improve root traits related to yield, water use efficiency, and stress tolerance. The association of QTNs with genes involved in known biological processes supports the validity of the QTL mapping approach and suggests potential mechanisms underlying trait variation. For instance, identifying genes related to auxin signaling and root development provides evidence for the involvement of these pathways in root architecture traits.The distribution of QTNs across multiple chromosomes indicates the polygenic nature of the studied traits. This polygenic architecture suggests that complex interactions between genes and environmental factors contribute to trait variation. The identification of QTNs in both coding and non-coding regions of the genome further emphasizes the complexity of gene regulation and its impact on trait expression. The presence of a significant number of uncharacterized or unknown proteins among the co-localized genes highlights the potential for novel gene discovery and functional characterization. The findings of this study have several implications for plant breeding. The identified QTNs can be used to develop marker-assisted selection (MAS) strategies for improving traits of interest. Additionally, the co-localized genes can serve as potential targets for gene editing or transgenic approaches to modify trait expression. Further functional characterization of these genes will provide a deeper understanding of their roles in trait variation and facilitate the development of targeted breeding strategies.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and the genotyping information deposited in https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.c59zw3rhk. Contact Temesgen Menamo, the corresponding author for additional information.

References

Adler, D. et al. vioplot: Violin Plot (2024). https://github.com/TomKellyGenetics/vioplot

Ali, M. et al. Overexpression of terpenoid biosynthesis genes modifies root growth and nodulation in soybean (Glycine max). Cells 11 (17), 2622 (2022).

Bekele, W. A. et al. Unravelling the genetic complexity of sorghum seedling development under low-temperature conditions. Plant. Cell. Environ. 37 (3), 707–723 (2014).

Bongue-Bartelsman, M. & Phillips, D. Nitrogen stress regulates gene expression of enzymes in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway of tomato. (1995).

Bardou, F. et al. Long noncoding RNA modulates alternative splicing regulators in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 30 (2), 166–176 (2014).

Poehlman, J. M. Breeding sorghum and Millet, in Breeding Field Cropsp. 508–555 (Springer, 1987).

Faostat, F., Agriculture Organization of the United Nations & Acceso FAO, Retrieved am from http://faostat3.fao.org/faostat-gateway/go/to/download/Q/QC/S. 20(2022). (2022).

Kang, J., Peng, Y. & Xu, W. Crop root responses to drought stress: molecular mechanisms, nutrient regulations, and interactions with microorganisms in the rhizosphere. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (16), 9310 (2022).

Cannon, W. A. A tentative classification of root systems. Ecology 30 (4), 542–548 (1949).

Singh, V., Hammer, G. & Van Oosterom, E. Variability in structure and function of sorghum root systems. in Global Issues, Paddock Action. Proceedings of the 14th Australian Society of Agronomy Conference. (2008).

Tari, I. et al. Response of sorghum to abiotic stresses: A review. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 199 (4), 264–274 (2013).

Elias, M. et al. Multi-locus genome‐wide association study reveal genomic regions underlying root system architecture traits in Ethiopian sorghum germplasm. The Plant Genome: p. e20436 (2024).

Menamo, T. et al. Genetic dissection of root architecture in Ethiopian sorghum landraces. Theor. Appl. Genet. 136 (10), 209 (2023).

Deja-Muylle, A. et al. Exploiting natural variation in root system architecture via genome-wide association studies. J. Exp. Bot. 71 (8), 2379–2389 (2020).

Kebede, A. et al. Multi-locus genome-wide association analysis for root and shoot traits at seedling stage in Ethiopian sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) accessions. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution: pp. 1–23 (2024).

Demelash, H. et al. Determination of root system architecture variation of drought adapted sorghum genotypes using high throughput root phenotyping. Rhizosphere: p. 100370 (2021).

Lafarge, T., Broad, I. & Hammer, G. Tillering in grain sorghum over a wide range of population densities: identification of a common hierarchy for tiller emergence, leaf area development and fertility. Ann. Botany. 90 (1), 87–98 (2002).

Singh, V. et al. Genetic control of nodal root angle in sorghum and its implications on water extraction. Eur. J. Agron. 42, 3–10 (2012).

Jain, S. & Allard, R. W. Population studies in predominantly self-pollinated species, I. Evidence for heterozygote advantage in a closed population of barley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 46(10): pp. 1371–1377 (1960).

Rogers, S. O. & Bendich, A. J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 5, 69–76 (1985).

Tamba, C. L. & Zhang, Y. M. A fast MrMLM algorithm for multi-locus genome-wide association studies. Biorxiv: p. 341784 (2018).

Wang, S. B. et al. Improving power and accuracy of genome-wide association studies via a multi-locus mixed linear model methodology. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 19444 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. pLARmEB: integration of least angle regression with empirical Bayes for multilocus genome-wide association studies. Heredity 118 (6), 517–524 (2017).

Wen, Y. J. et al. Methodological implementation of mixed linear models in multi-locus genome-wide association studies. Brief. Bioinform. 19 (4), 700–712 (2018).

Ren, W. L. et al. pKWmEB: integration of Kruskal–Wallis test with empirical Bayes under polygenic background control for multi-locus genome-wide association study. Heredity 120 (3), 208–218 (2018).

Tamba, C. L., Ni, Y. L. & Zhang, Y. M. Iterative sure independence screening EM-Bayesian LASSO algorithm for multi-locus genome-wide association studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13 (1), e1005357 (2017).

VanRaden, P. M. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91 (11), 4414–4423 (2008).

LiLin-Yin, C. M. Circ. Manhattan Plot (2024). https://github.com/YinLiLin/CMplot

Mace, E. et al. The Sorghum QTL atlas: a powerful tool for trait dissection, comparative genomics and crop improvement. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132 (3), 751–766 (2019).

Smedley, D. et al. The biomart community portal: an innovative alternative to large, centralized data repositories. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (W1), W589–W598 (2015).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (D1), D1178–D (2012).

Bradbury, P. J. et al. TASSEL: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23 (19), 2633–2635 (2007).

Marroni, F. et al. Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in Populus nigra Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD4) gene. Tree. Genet. Genomes. 7, p1011–1023 (2011).

Girma, G. et al. A Large-scale Genome-Wide association analyses of Ethiopian Sorghum landrace collection reveal loci associated with important traits. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 691 (2019).

Girma, G. et al. A comprehensive phenotypic and genomic characterization of Ethiopian sorghum germplasm defines core collection and reveals rich genetic potential in adaptive traits. Plant. Genome. 13 (3), e20055 (2020).

Gladman, N. et al. SorghumBase: A web-based portal for sorghum genetic information and community advancement. Planta 255 (2), 35 (2022).

Voorrips, R. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93 (1), 77–78 (2002).

Browning, B. L., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. A one-penny imputed genome from next-generation reference panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103 (3), 338–348 (2018).

Hufnagel, B. et al. Multi-trait association mapping for phosphorous efficiency reveals flexible root architectures in sorghum. BMC Plant Biol. 24 (1), 562 (2024).

Ramalingam, A. P. et al. Pilot-scale genome-wide association mapping in diverse sorghum germplasms identified novel genetic loci linked to major agronomic, root and stomatal traits. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 21917 (2023).

Mace, E. et al. QTL for nodal root angle in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) co-locate with QTL for traits associated with drought adaptation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124 (1), 97–109 (2012).

Wang, H. et al. Identification of QTLs for salt tolerance at germination and seedling stage of Sorghum bicolor L. Moench Euphytica. 196 (1), 117–127 (2014).

Parra-Londono, S. et al. Sorghum root-system classification in contrasting P environments reveals three main rooting types and root-architecture-related marker–trait associations. Ann. Botany. 121 (2), 267–280 (2018).

Lopez, J. R. et al. Modification of the CERES grain sorghum model to simulate optimum sweet sorghum rooting depth for rainfed production on coarse textured soils in a sub-tropical environment. Agric. Water Manage. 181, 47–55 (2017).

Menamo, T. et al. Genetic diversity of Ethiopian sorghum reveals signatures of Climatic adaptation. Theor. Appl. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03727-5 (2020).

McKhann, H. I. & Hirsch, A. M. Isolation of chalcone synthase and chalcone isomerase cDNAs from alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.): highest transcript levels occur in young roots and root tips. Plant Mol. Biol. 24, 767–777 (1994).

Xiong, C. et al. Flavonoids are involved in phosphorus-deficiency-induced cluster-root formation in white lupin. Ann. Botany. 129 (1), 101–112 (2022).

Yonekura-Sakakibara, K., Higashi, Y. & Nakabayashi, R. The origin and evolution of plant flavonoid metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 943 (2019).

Demelash, H. et al. Multivariate analysis of root system architectural traits of sorghum for drought tolerance. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution: pp. 1–10 (2023).

Kim, S. H., Mizuno, K. & Fujimura, T. Regulated expression of adpglucose pyrophosphorylase and chalcone synthase during root development in sweet potato. Plant. Growth Regul. 38, 173–179 (2002).

Shvarts, M., Borochov, A. & Weiss, D. Low temperature enhances petunia flower pigmentation and induces chalcone synthase gene expression. Physiol. Plant. 99 (1), 67–72 (1997).

Lijuan, C. et al. Chalcone synthase EaCHS1 from Eupatorium adenophorum functions in salt stress tolerance in tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 885–894 (2015).

Buer, C. S., Imin, N. & Djordjevic, M. A. Flavonoids: New roles for old molecules. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52 (1), 98–111 (2010).

Cho, H., Cho, H. S. & Hwang, I. Emerging roles of RNA-binding proteins in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 51, 51–57 (2019).

Reddy, A. Nuclear pre-mRNA splicing in plants. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 20 (6), 523–571 (2001).

Földi, M. The role of alternative splicing in plants. (2024).

Zhang, K. L. et al. Systematic characterization of the branch point binding protein, splicing factor 1, gene family in plant development and stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–20 (2020).

Torii, K. U. Leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases in plants: structure, function, and signal transduction pathways. Int. Rev. Cytol. 234 (0), 1–46 (2004).

Wang, G. et al. The diverse roles of extracellular leucine-rich repeat-containing receptor-like proteins in plants. Crit. Reviews Plant. Sci. 29 (5), 285–299 (2010).

Garay-Arroyo, A. et al. Hormone symphony during root growth and development. Dev. Dyn. 241 (12), 1867–1885 (2012).

Lange, B. M. & Srividya, N. Enzymology of monoterpene functionalization in glandular trichomes. J. Exp. Bot. 70 (4), 1095–1108 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to the sorghum research national program based at Melkassa Agricultural Research Center. We also like to thank to Jimma University for the phenotyping of the root architecture. Furthermore, we need to thank ICRISAT for genotyping the genetic material at BecA-ILRI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yirgalem Tsehaye: Genotypic data generation, original draft writes up and editing. Temesgen M. Menamo: Data analysis, original draft write-up, editing and supervision. Habtamu Demelash: Phenotypic data generation, original draft write-up and editing. Fetien Abay: Supervision, reviewing and editing. Taye Tadesse: Supervision, reviewing and editing. Kassahun Bantte: Supervision, reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsehaye, Y., Menamo, T.M., Demelash, H. et al. Multi-locus genome-wide association study reveals genomic regions underlying root system architecture traits early growth stage of sorghum germplasm. Sci Rep 15, 31727 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99012-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99012-w