Abstract

Phospholipids derived from plants are promising for drug delivery applications. This study aimed to develop liposomes from cost-effective, plant-derived soy lecithin to enhance the cytotoxicity of curcumin (CUR) against a panel of human cancer cells. The optimized curcumin-loaded liposomes (CUR-Liposomes) were characterized and exhibited a nanoscale size of 105.7 nm, and a high negative zeta potential of -49.9 mV. The key finding from the in vitro cytotoxicity assay was that CUR-liposomes demonstrated significantly enhanced anticancer activity compared to free CUR, as evidenced by lower half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values across all tested cancer cell lines, including multidrug-resistant MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7/ADR), colon (Caco-2), lung (A549), prostate (PC3), and pancreatic (PANC-1) cancer cells. Notably, this enhanced cytotoxicity was not observed in normal Vero cells, suggesting a favorable selectivity profile. These findings demonstrate that liposomal encapsulation using plant-derived lipids is a viable strategy to improve the therapeutic efficacy and potential selectivity of CUR for cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, and the disease’s death rates remain relatively high even with increased global awareness and the availability of multitargeted treatment options1,2. Chemotherapeutic drugs are commonly used to treat cancer; nevertheless, these agents have significant side effects since they are harmful to both tumor and normal cells. Furthermore, most people cannot afford these agents due to their unreasonable cost. Additionally, these substances cannot be utilized to prevent cancer. Thus, searching for cancer therapy approaches that are both more effective and less harmful is at the forefront of the current research. Traditional plant-derived therapies are often free of harmful side effects and are usually inexpensive: CUR is one such drug that is safe, economical, and effective3. CUR, the main element in the Curcuma longa plant, has gained much interest as an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer agent over the last two decades. CUR’s unique anticancer efficacy is primarily mediated by inducing apoptosis and reducing tumor proliferation and invasion via a range of cellular signaling pathways4,5. CUR has been found to have antitumor activity against breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung cancer, brain tumors, and prostate cancer. Several studies have demonstrated its ability to target numerous cancer cell lines5.

Despite all the benefits listed above, CUR’s low water solubility, which leads to low chemical stability and poor oral bioavailability, limits its applications6; an additional obstacle is the limited cellular absorption of CUR. Owing to its hydrophobic nature, CUR tends to penetrate the cell membrane and bind to the fatty acyl chains of the membrane lipids via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen binding; this leads to a decrease in CUR’s availability within the cytoplasm5,7. To overcome all these obstacles and enhance CUR’s overall anticancer effectiveness, various delivery systems, such as liposomes, are used8,9.

Liposomes are phospholipid bilayer vesicles that can transport both hydrophobic and hydrophilic pharmaceuticals. Liposomes’ amphiphilic phospholipid bilayer is very similar to the mammalian cell membrane, allowing for efficient interactions between liposomes and cell membranes and, as a result, successful cellular uptake. Combining CUR with liposomes is a valuable strategy to overcome cancer cells’ multidrug resistance. This is because liposomes can increase CUR’s water solubility and bioavailability10, and CUR itself can overcome drug resistance by controlling multidrug-resistant cancer cells’ signaling pathways, decreasing the expression of proteins linked to drug resistance, reversing mechanisms of multidrug resistance, and increasing the sensitivity of multidrug-resistant cells11.

Phospholipid-based formulations have gained significant attention in recent years due to their safety, stability, and suitability for pharmaceutical applications. Soy lecithin, in particular, is considered an economical and widely available phospholipid source that can be used for cost-effective liposome preparation. Several previous studies have investigated liposomal formulations of CUR; however, many of these reports evaluated their cytotoxicity in only one or two cancer cell lines, which restricts understanding of how different tumor types may respond to free versus encapsulated CUR. To address this limitation in scope, the present study examines the effect of free CUR and CUR-loaded soy lecithin liposomes across a broader panel of human cancer cell lines, including MCF-7/ADR, A549, Caco-2, PANC-1, and PC-3, in addition to a normal Vero cell line. The liposomal formulation was prepared using the thin-film hydration method and characterized by particle size distribution, zeta potential, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and encapsulation efficiency. CUR in both forms was then tested on all selected cell lines to obtain a wider overview of its cytotoxic profile. This broader cell-line panel provides a more informative and translational perspective compared with earlier studies that relied on a limited number of cancer models.

Materials and methods

This study employed various materials, including CUR (> 95% purity; molecular weight 368.38 g/mol), purchased from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India). Soy lecithin (SL) powder (molecular weight 643.97 g/mol) was obtained from bulk-supplements.com (Henderson, NV, USA). Cholesterol (CHOL; molecular weight 386.65 g/mol; and melting point 148–150 °C) was purchased from Advent Chembio Pvt. Ltd. (India). Chloroform (trichloromethane), ethanol (99%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide) were obtained from Alfa Chemical Stores (Egypt). Distilled water and saline solution were used throughout the experimental procedures. A549, Caco-2, PANC-1, PC-3, MCF-7/ADR, and Vero cells were obtained from the Egyptian Holding Company for Biopharmaceuticals and Vaccines Production (Vacsera, Cairo, Egypt).

Preparation of CUR solution

A solution was made by dissolving CUR in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to achieve a 1.2 mg/mL concentration. The mixture was subjected to vortex mixing for 2 min to ensure homogeneity.

Preparation of CUR-loaded liposomes

CUR-loaded liposomes were prepared using the thin-film hydration method. Briefly, soybean lecithin, cholesterol, and CUR were combined at a molar ratio of 6.15: 2.5: 0.6, respectively. The lipid and drug components were first dissolved in a chloroform solution. The organic solvent was then evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator maintained at 55 °C and 100 rpm for 30 min, forming a thin lipid film on the inner wall of the flask. To ensure complete removal of any residual solvent, the film was further dried under vacuum for an additional 15 min. The resulting thin film was subsequently hydrated with 23 mL of distilled water under gentle agitation. The coarse multilamellar vesicle (MLV) dispersion obtained was then sonicated in a water bath sonicator for 2 min and briefly vortexed to yield a homogeneous suspension of CUR-Liposomes12,13.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The molecular structure characterization of CUR-liposomes was analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy (JASCO 6100 spectrophotometer, Japan) at the Micro Analytical Center, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt.

1 mL of CUR-liposomes was centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm to extract the pellet for analysis. Spectra between 4000 and 400 cm−1 were obtained14.

Evaluation of CUR-lipid association

The interaction between CUR and the liposomal components was evaluated by analyzing changes in their concentrations in the supernatant before and after centrifugation. The concentrations of both CUR and soy lecithin (lipid) in the supernatant were quantified using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC Chromatograph YL- 9100 system) with a C-18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and 5% acetic acid in a ratio of 75:25, delivered at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Detection was performed at a wavelength of 425 nm.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS)

The CUR-liposomes’ particle size and zeta potential were assessed using a DLS Zetasizer Nano series Nano ZS ZEN3600 (Malvern Instruments, UK) analyzer that yields data on molecular weight, concentration, zeta potential, and particle size15.

Before measurements were performed, the samples were diluted 100 times. Adjust the refractive index, temperature, and detecting angle to 25 °C and 90 °C, respectively. Select the appropriate cuvette for the sample and begin the analysis using a Helium-Neon Laser beam.

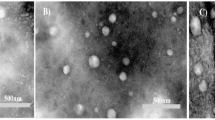

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Utilizing a JEM-2100 h TEM (JEOL, Japan; 200 kV) at the National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt, the CUR liposomes’ shape and microstructure were examined. Before imaging, the sample was made by placing a drop of transmittance negative stain, phosphor tungsten acid, over a copper grid coated with carbon and letting it air dry.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The thermal behavior and phase transition temperature of the CUR-liposomes formulation were analyzed using DSC (Labsys evolution, SETARAM, France) at the National Research Center, Cairo, Egypt. The sample was placed in a sealed aluminum crucible and subjected to a heating scan from 30 °C to 80 °C under a controlled atmosphere. This analysis allowed for the determination of the phase transition temperature (Tm) and other relevant thermodynamic parameters of the lipid bilayer, providing insight into the stability and physical properties of the liposomal formulation.

In vitro cell line study

A549, caco-2, PANC-1, PC3, MCF-7/ADR cells, and Vero cells from the Egyptian Holding Company for Biopharmaceuticals and Vaccines Production (Vacsera) in Cairo, Egypt, were used for the cytotoxicity test for both the CUR and CUR-liposomes samples. To create a full monolayer sheet, the cells were seeded at a density of about 1 × 105 cells/mL (100 µl/well) and dispensed in a 96-well tissue culture plate. They were then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Following the formation of a confluent sheet of cells, the growth medium was decanted from 96-well microtiter plates, and the cell monolayer was twice washed with wash media. The tested material was diluted twice in RPMI medium (maintenance medium) containing 2% serum.

For each cell line, the following control groups were included: Negative control: untreated cells (maintenance medium only), vehicle control: cells treated with DMSO at the same final concentration present in the highest CUR treatment (300 µg/mL), and positive control: cells treated with doxorubicin (DOXO) at concentrations of 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL. Each treatment concentration (including controls) was added at 0.1 mL per well. After being incubated at 37 °C, the plate was inspected. Physical indicators of toxicity, such as rounding, shrinkage, cell granulation, or partial or whole loss of the monolayer, were examined in the cells. A 5 mg/mL MTT solution in PBS was made (Bio Basic Canada Inc.). Each well received a 20 µL addition of MTT solution. To fully incorporate the MTT into the medium, place it on a shaking table and spin it at 150 rpm for five minutes. Allow the MTT to be metabolized by incubating it for four hours at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. Empty the media (if needed, dry the plate on paper towels to get rid of any residue).

Formazan, an MTT metabolic product, should be reconstituted in 200 µL of DMSO. To fully incorporate the formazan into the solvent, place it on a shaking table and spin it at 150 rpm for five minutes. At 560 nm, read the optical density; at 620 nm, subtract the background. There should be a direct relationship between optical density and cell number.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel’s Data Analysis ToolPak was used for statistical analysis. An unpaired t-test (assuming unequal variances) was performed to compare the cytotoxicity between free CUR and CUR-Liposomes in Vero cells, using the raw optical density (OD) values from three independent replicates (n = 3). The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Molecular structure characterization

The FTIR spectra of free CUR, free liposomes (soy lecithin and cholesterol), and CUR-Liposomes are shown in Fig. 1. The spectral analysis was conducted over the range of 4000–400 cm−116.

CUR spectrum

CUR exhibited characteristic peaks at ~ 3510 cm−1 corresponding to O–H stretching17 (phenolic group), ~ 1627 cm−1 assigned to C = O and C = C stretching (conjugated diketone and aromatic groups), multiple bands in the range of 1270–1020 cm−1 attributed to C–O stretching and C–H bending. These peaks confirm the presence of hydroxyl, carbonyl, and aromatic functionalities in the CUR structure18,19.

Free liposomes spectrum

The liposomes without CUR showed a broad band at ~ 3400 cm−1 due to O–H stretching (from phospholipid and cholesterol), strong C–H stretching bands at ~ 2920 cm−1 and ~ 2850 cm−1, and a sharp ester C = O band at ~ 1735 cm−120,21.

CUR-liposomes spectrum

The FTIR spectrum of CUR-liposomes exhibited a combination of peaks from both CUR and the liposomes structure. However, noticeable changes were observed: The O–H peak around ~ 3510 cm−1 became broader and less intense, indicating hydrogen bond formation between CUR and the lipid bilayer. The C = O and aromatic C = C peaks around ~ 1627 cm−1 were reduced and slightly shifted, suggesting interaction and possible encapsulation of CUR. The strong bands from the liposomes matrix, such as the C–H stretching (~ 2920 & 2850 cm−1) and ester C = O (~ 1735 cm−1), remained visible in CUR-Liposomes. The fingerprint region (~ 1230–1050 cm−1) also preserved the characteristic bands of phospholipids. These spectral changes confirm the successful encapsulation of CUR within the liposomal structure, with evidence of interaction between the active compound and the lipid components13,21.

Evaluation of CUR-lipid association

The concentrations of both CUR and soy lecithin (lipid) in the supernatant were quantified using HPLC, the CUR-liposomes formulation was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 8 min to separate the liposomal pellet from the supernatant. The molar concentrations (µmol/mL) of both CUR and lipid in the supernatant, before and after centrifugation, were calculated using their respective molecular weights (CUR: 368.38 g/mol; soy lecithin: 643.97 g/mol). The change in lipid-to-CUR molar ratio was calculated as follows: Change in Molar Ratio = (Lipid/CUR molar ratio AFTER centrifugation) / (Lipid/CUR molar ratio BEFORE centrifugation). For our formulation, the lipid-to-CUR molar ratio in the supernatant decreased from 5.72 to 0.25 µmol/µmol after centrifugation, resulting in a change ratio of 0.04. This significant reduction indicates substantial co-precipitation of CUR with the liposomal lipid during the centrifugation process.

Determination size and zeta potential

The particle size and zeta potential of CUR-Liposomes were determined by a DLS Zetasizer Nano series Nano ZS ZEN3600 (Malvern Instruments, UK) analyzer, which provides information on particle size and zeta potential. DLS analysis revealed that the average hydrodynamic diameter of the CUR-loaded liposomes was 105.7 nm, as shown in Fig. 2a, with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.201, suggesting a relatively uniform size distribution. The single, well-defined peak suggests a monodisperse population of nanoparticles with minimal aggregation. The measured hydrodynamic diameter reflects the particle size in suspension, including the solvation layer, and is typically larger than the physical diameter observed under TEM, due to the contribution of the solvation layer and potential interparticle interactions in aqueous dispersion, while TEM measures the dry-state physical diameter of individual particles. These results confirm the nanoscale size and good homogeneity of the liposomal formulation.

The zeta potential of the CUR-loaded liposomes was measured to evaluate their colloidal stability. The results showed a high negative zeta potential value of -49.9 mV, with a major peak at -51.2 mV accounting for 95.5% of the total distribution, as shown in Figure 2b. This high magnitude of surface charge indicates strong electrostatic repulsion between particles, suggesting excellent stability of liposomal dispersion and a low tendency for aggregation over time. These values are within the optimal range for stable nanoparticle suspensions (±30 mV or more)22,23.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM provided additional confirmation of the sample’s detailed morphology. Any material structure change can be highlighted with this method. A drop from the liposomal dispersion was applied onto carbon-coated copper that was set on filter paper to create the sample. Before imaging, let it air dry for a few seconds, then apply a drop of transmittance-negative stain. As illustrated in Fig. 3, because of CUR, the TEM pictures showed black patches inside the liposomes, which suggested the existence of electron-dense components. Its breadth ranges from 13.6 nm to 37.5 nm, and it likewise had a multilamellar appearance, demonstrating the creation of concentric lipid bilayers within the liposomes. TEM scans demonstrated that the size range of CUR-Liposomes was within the range of their therapeutic potential24.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC analysis has been performed on our sample to study the effect of temperature on the synthesized liposomes, mainly to determine the phase transition temperature. In Fig. 4, the thermogram revealed a broad endothermic transition around 45 °C, which corresponds to the main phase transition temperature (Tm) of the lipid bilayer. This transition reflects the change from a gel phase (ordered structure) to a liquid crystalline phase (disordered structure), indicating increased fluidity of the liposomal membrane. This influential parameter reflects the liposomes permeability toward the drug by describing the membrane fluidity.

Cell line cytotoxicity

The biocompatibility of synthesized CUR-liposomes as drug delivery systems in MCF-7/ADR cells (Table 1), A549 (Table 2), caco-2(Table 3), PANC-1(Table 4), PC3 (Table 5), and Vero cells (Table 6) in both different concentrations of CUR and CUR-liposomes was assessed using cytotoxicity assays. The histograms of all cell viability analyses are presented in Fig. 5. The cell viability assay, as demonstrated in Table 1; Fig. 5a, is effective in assessing the impact of drug candidates on cells and can help refine cell culture conditions. The results indicate that CUR-Liposomes impedes cell growth. The Mcf7ADR cell line was treated with varying concentrations of CUR and CUR-Liposomes (300, 100, 30, 10, 3, 1, and 0.3 µg/mL) separately. A comparison of cell viability across all concentrations of CUR-Liposomes with that of CUR shows a notable difference, with a decline in cell viability from lower to higher concentrations in CUR-Liposomes, while cell viability remains relatively stable at lower concentrations for CUR. The IC50 ± SD values for CUR and CUR-Liposomes were 249.85 ± 1.8 and 87.43 ± 1.18, respectively.

As presented in Table 2; Fig. 5b, the A549 cell line was also subjected to 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, 1, and 0.3 µg/mL of both CUR and CUR-Liposomes separately. The IC50 ± SD for CUR and CUR-Liposomes were 185.8 ± 0.95 and 44.43 ± 0.38. In Table 3; Fig. 5c, the Caco2 cell line was treated with the same concentrations of CUR and CUR-Liposomes separately. The IC50 ± SD results were 9.34 ± 0.04 for CUR and 2.44 ± 0.01 for CUR-Liposomes. In Table 4; Fig. 5d, the PANC1 cell line underwent exposure to CUR and CUR-Liposomes at the same concentrations. The IC50 ± SD values were 4.96 ± 0.02 for CUR and 1.89 ± 0.02 for CUR-Liposomes. In Table 5; Fig. 5e, the (Pc3) cell line was exposed to CUR and CUR-Liposomes at the same concentrations. The IC50 ± SD of both CUR and CUR-Liposomes was 6.1 ± 0.09 and 2.88 ± 0.05. For the normal Vero cell line, which was exposed to the same concentrations of CUR and CUR-Liposomes (as shown in Table 6; Fig. 5f), the IC50 ± SD was 16.9 ± 0.2 for CUR and 15.49 ± 0.05 for CUR-Liposomes.

The IC50 values obtained from cytotoxicity assays indicated that CUR-Liposomes was notably more effective than free CUR across all investigated cancer cell lines (MCF-7/ADR, A549, Caco-2, PANC-1, and PC3). In every instance, a lower concentration of CUR-Liposomes was necessary to achieve 50% inhibition of cell viability in comparison to free CUR, emphasizing the increased anticancer effectiveness of the liposomal formulation. Thus, it can be inferred that CUR-Liposomes formulations are biocompatible, and suitable for drug delivery systems25. Significantly, in Vero cells (a normal cell line), the IC50 values for CUR and CUR-Liposomes were quite similar (16.9 µg/mL and 15.49 µg/mL, respectively). Statistical analysis (unpaired t-test, p > 0.05) confirmed that this difference was not significant, indicating that liposomal encapsulation did not enhance toxicity toward normal cells. This trend indicates that although CUR-Liposomes boost cytotoxic effects in cancer cells, it retains a relatively safe profile in non-cancerous cells.

In summary, these findings reveal that the liposomal encapsulation of CUR enhances its anticancer effectiveness, enabling significant cytotoxicity at lower concentrations than free CUR, while not markedly increasing toxicity in normal cells26. The inclusion of the vehicle control (DMSO) confirmed that the solvent itself had no observable cytotoxic effect at the final concentration used. Additionally, doxorubicin, used as a positive control, produced the expected marked reduction in cell viability, confirming the responsiveness of the assay.

The morphological observations are shown in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, where each panel includes: untreated cells (negative control), DMSO-treated cells (vehicle control), doxorubicin-treated cells (positive control), free CUR-treated cells, and CUR-Liposomes-treated cells. Clear differences were observed between free CUR and CUR-Liposomes, particularly at higher concentrations, where CUR-Liposomes appeared to induce more pronounced morphological changes in cancer cells. Cytotoxicity, as represented by the IC50 values for free CUR and CUR-Liposomes across different cell lines, is evident in Fig. 12. While CUR-Liposomes generally exhibited lower IC50 values than free CUR in cancer cell lines, indicating enhanced cytotoxic potency, both formulations showed comparable effects in Vero cells. These findings suggest that liposomal encapsulation improves CUR cytotoxicity toward cancer cells without substantially increasing toxicity in normal cells.

Cell viability of (A) MCF-7/ADR cells, (B) A549 cells, (C) Caco-2 cells, (D) PANC-1 cells, (E) PC-3 cells, and (F) Vero (normal) cells after exposure to 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, 1, and 0.3 µg/mL of CUR and CUR-Liposomes. Red bars represent CUR and green bars represent CUR-Liposomes, the values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Representative morphology of MCF-7/ADR cells. (A) Untreated cells (Negative Control). (B) Cells treated with DMSO (Vehicle Control; same final DMSO concentration used in the 300 µg/mL treatment). (C) Cells treated with DOXO at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively (Positive Control). (D) Cells treated with free CUR at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively. (E) Cells treated with CUR-Liposomes at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively.

Representative morphology of A549 cells. (A) Untreated cells (Negative Control). (B) Cells treated with DMSO (Vehicle Control; same final DMSO concentration used in the 300 µg/mL treatment). (C) Cells treated with DOXO at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively (Positive Control). (D) Cells treated with free CUR at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively. (E) Cells treated with CUR-Liposomes at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively.

Representative morphology of Caco2 cells. (A) Untreated cells (Negative Control). (B) Cells treated with DMSO (Vehicle Control; same final DMSO concentration used in the 300 µg/mL treatment). (C) Cells treated with DOXO at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively (Positive Control). (D) Cells treated with free CUR at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively. (E) Cells treated with CUR-Liposomes at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively.

Representative morphology of PANC1 cells. (A) Untreated cells (Negative Control). (B) Cells treated with DMSO (Vehicle Control; same final DMSO concentration used in the 300 µg/mL treatment). (C) Cells treated with DOXO at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively (Positive Control). (D) Cells treated with free CUR at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively. (E) Cells treated with CUR-Liposomes at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively.

Representative morphology of PC3 cells. (A) Untreated cells (Negative Control). (B) Cells treated with DMSO (Vehicle Control; same final DMSO concentration used in the 300 µg/mL treatment). (C) Cells treated with DOXO at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively (Positive Control). (D) Cells treated with free CUR at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively. (E) Cells treated with CUR-Liposomes at 300, 100, 30, 10, 3, and 1 µg/mL, respectively.

Conclusions

In this study, curcumin-loaded liposomes (CUR-liposomes) were successfully developed and characterized. The optimized formulation demonstrated enhanced anticancer activity across multiple human cancer cell lines while maintaining a safe profile in normal cells. These results highlight the potential of CUR-liposomes as an effective drug delivery system for cancer therapy. This plant-derived liposomal system represents a promising approach for enhancing curcumin’s therapeutic potential in cancer treatment. Future studies should focus on in vivo evaluation, long-term stability, and optimization of the liposomal formulation to further improve therapeutic efficacy and clinical applicability.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- A549:

-

Human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line

- Caco-2:

-

Colon cancer cells

- CUR:

-

Curcumin

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- DOXO:

-

Doxorubicin

- DSC:

-

Differential scanning calorimetry

- FTIR:

-

Fourier transform infrared

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- IC50:

-

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- MCF-7/ADR:

-

Human multidrug-resistant breast adenocarcinoma cells

- PANC-1:

-

Pancreatic cancer cells

- PC3:

-

Human prostate cancer cells

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30 (2020).

Zhou, V. et al. The role of curcumin in cancer treatment. Biomedicines 9, 1086 (2021).

Ravindran, J., Prasad, S. & Aggarwal, B. B. Curcumin and cancer cells: how many ways can curry kill tumor cells selectively? AAPS J. 11, 495–510 (2009).

Kunnumakkara, A. B. et al. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 1325–1348 (2017).

Teng, M., Hu, R. & Zhao, X. A review of curcumin and its derivatives as anticancer agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1033 (2019).

Nakamura, K. et al. Discovery of a new function of curcumin which enhances its anticancer therapeutic potency. Sci. Rep. 6, 30962 (2016).

Taira, M., Katagiri, K., Akiyama, R. & Yamada, K. Modulation of raft domains in a lipid bilayer by boundary-active curcumin. Chem. Commun. 50, 10112–10115 (2014).

Komal, K., Chaudhary, S., Yadav, P., Pramanik, R. & Singh, M. The therapeutic and preventive efficacy of curcumin and its derivatives in esophageal cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 20, 1329–1336 (2019).

Fang, T., Wang, Y., Li, R. J. & Zhao, L. Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 6027–6044 (2017).

Zheng, S. et al. Liposomal curcumin alters chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells to adriamycin via regulating MicroRNA expression. Gene 622, 1–9 (2017).

Sharma, K. G., Kumar, K. & Gupta, A. Curcumin effect on cancer cells’ multidrug resistance: an update. Phytother Res. 34, 2579–2591 (2020).

Zhang, Y. Thin-film hydration followed by extrusion method for liposome preparation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1522, 17–22 (2017).

Andra, V. V. S. N. L., Pammi, S. V. N., Bhatraju, L. V. K. P. & Ruddaraju, L. K. A comprehensive review on novel liposomal methodologies, commercial formulations, clinical trials and patents. Bionanoscience 12, 731–748 (2022).

Smith, B. C. Fundamentals of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (CRC Press, 2011).

Stetefeld, J., McKenna, S. A. & Patel, T. R. Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophys. Rev. 8, 409–427 (2016).

Priyadarsini, K. I. The chemistry of curcumin: from extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules 19, 20091–20112 (2014).

Tiernan, H., Byrne, B. & Kazarian, S. G. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging for the analysis of biopharmaceuticals. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 241, 118636 (2020).

Yeo, S., Kim, M. J., Shim, Y. K., Yoon, I. & Lee, W. K. Solid lipid nanoparticles of curcumin designed for enhanced bioavailability and anticancer efficiency. ACS Omega. 7, 36528–36539 (2022).

Hasan, M. et al. Growth-inhibitory effect of chitosan-coated liposomes encapsulating curcumin on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mar. Drugs. 18, 217 (2020).

Kumar, T., Ramesh, M., Li, M., Gao, Y. & Fang, Y. Stability and release performance of curcumin-loaded liposomes with varying content of hydrogenated phospholipids. Food Chem. 326, 126973 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. The stability, sustained release and cellular antioxidant activity of curcumin nanoliposomes. Molecules 20, 14293–14311 (2015).

Lankalapalli, S. & Tenneti, V. Drug delivery through liposomes. In Smart Drug Delivery (eds. Tekade, R. K.) 1–24 (IntechOpen, 2022).

Ahmed, S. A. et al. Development and characterization of soy lecithin liposome as potential drug carrier systems for doxorubicin. J. Pharm. Innov. 18, 772–783 (2023).

Le, N. T. T. et al. Soy lecithin-derived liposomal delivery systems: surface modification and current applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4706 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Preparation of curcumin-loaded liposomes and evaluation of their skin permeation and pharmacodynamics. Molecules 17, 5972–5987 (2012).

Ghoran, S. H. et al. Curcumin-based nanoformulations: a promising adjuvant towards cancer treatment. Molecules 27, 5236 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the central labs in the National Research Center (NRC) and Micro Analytical Center - Faculty of Science - Cairo University.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SAA **1#** corresponding author conceived, designed, and performed the experiments and analyzed the data, writing and reviewing and editing the manuscript; HIH **2** performed the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the original manuscript’s draft, and MHG **1** conceived and designed the experiments and analyzed the data; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, S.A., Helmy, H.I. & Gaber, M.H. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity of free curcumin and a liposomal curcumin formulation on various human cancer cell lines. Sci Rep 16, 6346 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36607-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36607-x