Abstract

Exercise-induced inflammation has been shown to influence iron metabolism. Conversely, ischemic preconditioning (IPC) has been proposed as a strategy to modulate post-exercise response, especially inflammation and neurotrophic factor secretion. In this study we analyzed the effects of a 14-days IPC intervention on the post-exercises changes of the selected Iron metabolism, inflammation and neurotrophic markers in the population of non-training healthy young man. Forty healthy, untrained young men voluntarily participated in this study and were randomly assigned to two groups: an IPC group (n = 20), which underwent a 14-day IPC intervention, and a placebo (SHAM) group (n = 20). Five participants from the IPC group and seven from the SHAM group did not complete the protocol and were excluded from the analyzes. Venous blood samples were collected at rest, immediately after and 2 h after the Wingate test. Selected inflammatory and neurotrophic markers were analyzed, including IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, LIF, BDNF, IGF-1, NGF, sAPPα, FSTL-1, and GDF-15. Additionally, serum levels of iron (Fe), hepcidin (Hpc), ferritin (Fer), erythroferrone (ERFE), and erythropoietin (EPO) were assessed. IPC increased resting ferritin (~ + 9%, p < 0.05), hepcidin (~ + 12%, p < 0.05), and erythroferrone (~ + 10%, p < 0.05) concentrations. The intervention also enhanced post-exercise IGF-1 (+ 8%, p = 0.03) and sAPPα (+ 10%, p = 0.04) release and reshaped cytokine profiles, with greater early elevations of GDF-15 and IL-15 (p < 0.05) and faster normalization of FSTL-1 within 2 h (p < 0.05). IPC further affected neurotrophic signaling, showing lower 2-h post-exercise BDNF levels (p < 0.05) and distinct IGF-1 kinetics (p < 0.01). Anaerobic performance remained unchanged (p > 0.05). Ischemic preconditioning induces coordinated alterations in iron metabolism and modulates inflammatory and neurotrophic responses to anaerobic exercise, without affecting physical performance in untrained individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay between exercise and inflammation is a major focus of contemporary research, particularly in understanding how physical activity modulates inflammatory responses and contributes to post-exercise recovery, both in recreational activity and sport performance. Recent studies have increasingly emphasized the inflammatory processes associated with high-intensity anaerobic exercise, which is characterized by high energy demands and substantial physiological stress, often resulting in a marked increase in circulating proinflammatory cytokines1,2,3,4,5,6. These physiological mechanisms are particularly evident during short-term, maximal anaerobic efforts such as those reproduced in the Wingate Anaerobic Test (WAnT), which serves as a well-established model for studying acute metabolic and inflammatory responses. Moreover, data shows that the post-exercise response can be influenced by iron status, which is one of the essential factors affecting human health7. Both iron deficiency and excess may contribute to the development of various diseases8. Conversely, both recreational physical activity and professional sports lead to a decline in body iron stores which is considered positive if the changes are in the physiological range9.

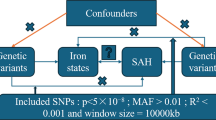

Research indicates that exercise can increase levels of IL-6, which in turn promotes the biosynthesis of hepcidin (HPC), a key regulatory protein involved in iron metabolism. Elevated HPC levels inhibit iron absorption from the digestive system and decrease its release from the liver into the bloodstream, leading to reduced serum iron levels. Since iron can exacerbate inflammatory processes, reducing its concentration through the actions of IL-6 and HPC may be advantageous. Serum hepcidin levels are regulated by various external factors (e.g., physical exercise) and hormonal secretions, such as erythropoietin (EPO) and erythroferrone (ERFE). Elevated EPO levels stimulate ERFE production, which in turn inhibits HPC synthesis in hepatocytes. The EPO/ERFE axis thus provides a signaling pathway that contrasts with the inflammatory cytokine pathway and contributes to the regulation of hepcidin during erythropoietic activation7,10,11. In this context, molecular pathways regulating iron homeostasis and those involved in neurotrophic signaling are interconnected, since mediators such as IL-6, EPO and IGF-1 participate in both erythropoietic adaptation and neuronal plasticity12,13,14. Building upon this interaction, several studies have shown that intense physical activity also promotes the expression and release of neurotrophic factors that mediate exercise-induced adaptations in the nervous and muscular systems. Exercises such as running, cycling, and swimming have been shown to elevate serum levels of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). These proteins promote synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and are considered crucial mediators of the beneficial effects of exercise on both muscular and cognitive performance15, influencing processes such as oxygen delivery, recovery, and fatigue resistance.

In light of these considerations, and in the context of ongoing efforts to identify methods to protect the body from the adverse effects of intense physical exercise, the present study aimed to evaluate the influence of a 14-day ischemic preconditioning (IPC) intervention on the acute post-anaerobic exercise response in markers of iron metabolism, inflammation, and neurotrophic factors in non-training individuals. We hypothesized that IPC modulates exercise-induced molecular signaling by attenuating inflammatory markers and enhancing neurotrophic factor release, and that observed changes are independent of daily physical activity levels. These findings may suggest that IPC could be a promising training procedure for modulating human health, particularly in non-trained individuals.

Materials and methods

Experimental overview

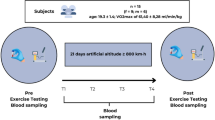

The study was designed as a single-blind randomized controlled trial with parallel groups. Participants were randomly assigned to two study groups undergoing either IPC or SHAM-controlled intervention (IPC vs. SHAM) for 14-consecutive days.

During the first visit (pre-intervention; one month prior the study) to medical examination took place and the planned research procedures and exercise tests were presented. In addition, a consultation with a dietician took place and a body composition assessment was performed to obtain population homogeneity.

Month later in the early morning, basic anthropometric characteristics were measured one more time (the subject’s age, height and bioimpedance body composition analysis—InBody 720, South Korea, Seoul, and venous blood samples were drawn. On the following day 2xWAnT Test was performed (according to the test specification). Standardized conditions were used for collecting blood samples according to the Delfan et al. and Saeidi et al.16,17 Blood samples were also collected immediately after (to 5 min), 2 h after finishing the test. Day after the test all participants started 14 subsequent days, either IPC or SHAM intervention. Day after ending last IPC or SHAM intervention all participants performed same 2xWAnT Test, with blood collected in the same time points as it was before the start of the intervention.

Blood samples were collected and secured in accordance standard procedures for this type of biological material. This allowed for the assessment of the post exercises-induced changes of the selected blood iron metabolism, neurotrophic and inflammation markers in response to 14-days of IPC training and Wingate Anaerobic Test. All laboratory analyzes where performed at the Gdansk University of Physical Education (Gdansk, Poland), or Synevo (Diagnostyka Laboratory, Poland; PN-EN ISO 15,189).

Participants

During the pre-screening 40 healthy young men was enrolled in the study (aged 20.3 ± 0.8). Participants were randomly assigned to two gropes: experimental (IPC; n = 20; aged: 20.2 ± 0.8 years) and control (placebo, SHEAM; n = 20; aged: 20.4 ± 0.7 years) (Fig. 1). All participants declared recreational participation in different forms of physical activity (ex. running, swimming, team sports but not more than 2 times per week for a duration not longer than 60 min) and had normal health status. Basic characteristics of studded population before and after 14-days of IPC intervention are shown in Table 1. Before starting the study, the participant was informed not to change her eating habits during the entire study period. To assess compliance with the guidelines three-day food records (two weekdays and one weekend day) were obtained before and after the study to assess changes in habitual dietary intake over time of the experiment17,18. During the analysis each food item decorated in the three-day food records was individually entered into diet analysis program for specific analysis of a total energy consumption and the amount of energy derived from proteins, fats, and carbohydrates19.

In line with the medical declaration and the medical assessments conducted prior to the research qualification, none of the participants had a history of known illnesses or reported any medication intake due to health issues in the six months leading up to the experiment.

One month prior to the study, all participants abstained from alcohol and any substances that could potentially affect the results and influence exercise performance (e.g., caffeine, guarana, theine, chocolate, and others). Additionally, two weeks before the study, following dietary consultations, all participants adopted a uniform eating pattern tailored individually to their sex, age, occupation, and physical activity levels.

The study protocol received approval from the Bioethics Committee of the University of Physical Education and Sport in Gdańsk (Resolution No. 2, dated December 16, 2024) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was registered as a clinical trial (NCT05229835, date of first registration: 14/01/2022).

All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and were informed about the study procedures. However, they were not made aware of the underlying rationale or objectives of the study to preserve their naivety regarding the potential effects of ischemic preconditioning procedures. Due to the impossibility of completing the study protocol five participants from the IPC population and seven participants from the SHAM population were excluded from the study and further analyzes (Fig. 1).

Remote ischemic preconditioning

The remote ischemic preconditioning (IPC) intervention was conducted under standardized conditions throughout the entire experimental period, following the protocols described by Mieszkowski et al. and Brzezińska et al.20,21. The procedure was administered every day at the same, morning hours (between 08:00 and 10:00 a.m. before any meal) with participants positioned supine on the medical couches in the Labolatory of Physiology Gdańsk University of Physical Education and Sport. Each participant underwent 14-consecutive days of either IPC or SHAM procedure. During whole experiment participant had no information about the groups and differences in their protocols. In the IPC group, bilateral pneumatic cuffs were placed proximally on both thighs and inflated to 220 mmHg to induce full arterial occlusion (IPC population). Participants assigned to the SHAM condition, both pneumatic cuffs were also applied bilaterally on the upper thighs but inflated to a sub-occlusive pressure of 20 mmHg, insufficient to impair arterial blood flow. Each session consisted of four cycles of 5-min occlusion (IPC/SHAM) followed by 5-min reperfusion. To stabilize cardiovascular parameters and ensure participant comfort, individuals remained in a supine position for 15 min before and after the IPC/SHAM procedure.

The effectiveness of arterial occlusion was confirmed using Doppler ultrasonography (Edan DUS 60, SonoTrax Basic, Edan Instruments GmbH, Langen, Germany) in order to ensure the effectiveness of each time vascular occlusion. All ultrasonographic assessments were performed by a physician certified in ultrasound imaging and conducted in accordance with the standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society.

Maximal anaerobic physical activity: Wingate anaerobic test

To induce intracellular damage associated with extreme physical effort, a Wingate Anaerobic test (WAnT) in adaptation on lower limbs was performed on a cycle ergometer (Monark 894E, Peak Bike, Sweden) according with the Bar-Or and Kochanowicz et all modifications22,23. Prior to testing, each participant underwent a standardized warm-up on the cycle ergometer (5 min at 60 rpm, 1 W/kg).

During the testing phase, participants were instructed to pedal with maximum effort against a fixed resistive load of 75 g/kg of their total body mass for 30 s. Throughout the testing phase, verbal encouragement was provided from start to finish to help maintain the highest possible cadence during the Wingate Anaerobic Test. The cycle ergometers were linked to a personal computer that operated the MCE 5.1 software. The following WAnT metrics were recorded: peak power (W) and relative peak power (W/kg) (measured at 0.2-s intervals); mean power (W) and relative mean power (W/kg), calculated as the average power output over the 30-s test.

Sample collection and measurements of metabolite levels

Venous blood samples were collected according at three time points before and after the start of the experiment: immediately before, directly after, and 2 h following the double Wingate Anaerobic Test (WAnT), using 8.5 mL BD Vacutainer® SST™ II Advance serum tubes (Becton Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA) containing a coagulant for blood analysis. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 4000 ×g for 10 min, aliquoted into 500 μL portions, and stored at − 80 °C for a maximum of 6 months prior to analysis. The selected sampling time points were chosen to capture both the peak inflammatory response and the early recovery phase, reflecting the known rapid kinetics of cytokine responses (e.g. IL-6, IL-10 rises within minutes to hours post-exercise as demonstrated by Kochanowicz et al.24 and neurotrophic factor dynamics25.

The selected markers were analysed according to the medical diagnostic procedures referenced by European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. All inflammatory and neurotrophic markers—including BDNF, IGF-1, NGF, FSTL-1, GDF-15, IL-6, IL-10, IL-15, and LIF—were quantified using the MAGPIX® fluorescence-based detection system (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA) and corresponding Luminex® assay kits.

Serum sAPPα was messured using commercially available highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits—Human Soluble Amyloid Precursor Protein Alpha, sAPP Alpha GENLISA™ ELISA kit (Cat No#KBH3278) (Krishgen Biosystems, Cerritos, USA) on a Thermo Fisher Scientific ELISA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Basic hematological parameters and iron metabolism markers were analyzed in an accredited clinical laboratory (Synevo Laboratory, Bydgoszcz, Poland; PN-EN ISO 15,189) using fully automated clinical analyzers.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 13.3.0 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of data distribution, and Levene’s test was applied to verify the homogeneity of variances. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (2 × 2; group × time: pre vs. post intervention) was conducted to evaluate the effects of the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention on resting values of physical characteristics, hematological parameters, iron metabolism markers, inflammatory cytokines, neurotrophic growth factors, and anaerobic performance parameters.

To examine the acute exercise-induced changes in circulating inflammatory markers, neurotrophic factors, and iron metabolism indices in response to the double Wingate Anaerobic Test (WAnT), a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (2 × 3; group × time: pre, immediately post, 2 h post) was performed. If significant main or interaction effects were detected, Tukey’s post hoc test was used for pairwise comparisons.

In case where baseline imbalance between groups was identified, the data were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with baseline values as covariates and group as a fixed factor.

Effect sizes were calculated using eta-squared (η2) and interpreted as small (η2 < 0.06), moderate (0.06 ≤ η2 < 0.14) and large (η2 ≥ 0.14). The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

The appropriate sample size for analyzing the interactions between the effects was determined through a power analysis using GPower ver. 3.1.9.2. With a total of 28 participants (15 IPC and 13 SHAM), an effect size f = 0.40 (corresponding to a large group × time interaction observed in the present study) yielded a statistical power of 0.82 at α = 0.05.

Results

Table 2 presents the hematological parameters and related biochemical markers measured before and after the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention. Hematological indices and related biochemical markers remained largely stable following the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention, with no significant group × time interactions. A significant main effect of time (F(1, 26) = 58.15, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.69) and a group × time interaction (F(1, 26) = 7.36, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.22) were observed only for creatine kinase (CK), with CK levels decreasing markedly in both groups post-intervention (IPC: − 35%, p < 0.01; SHAM: − 19%, p < 0.01).

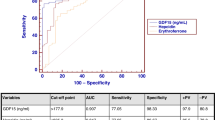

The concentrations of iron metabolism, inflammatory, and neurotrophic growth factors measured before and after the 14-day IPC or SHAM intervention are detailed in Table 3. ANOVA analysis revealed a significant group × time interaction for erythroferrone (F(1, 26) = 12.55, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.32), ferritin (F(1, 26) = 12.65, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.33), hepcidin (F(1, 26) = 8.87, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.25), and serum iron. Post hoc results showed that resting concentrations of erythroferrone, ferritin, and hepcidin increased by 10% (p < 0.01), 9% (p < 0.05), and 12% (p < 0.01), respectively, in the IPC group following the 14-day intervention. Baseline ferritin levels were 22% lower (p < 0.05) in the IPC group compared with SHAM (p < 0.05); however, after adjustment for baseline differences using ANCOVA, post-intervention ferritin remained significantly lower in the IPC group (F(1, 26) = 7.89, p = 0.009, partial η2 = 0.24), indicating that the observed effect was independent of initial variability.. An opposite trend was observed for resting iron concentrations, which increased by 33% (p < 0.01) in the SHAM group after the 14-day intervention, resulting in significantly higher post-intervention iron levels (p < 0.05) compared to the IPC group.

† significant differences vs. IPC group after 14-days IPC intervention.

# significant differences vs. SHAM group before 14-days SHAM intervention.

No significant group, time, or group × time effects were observed in the resting concentrations of inflammatory markers or neurotrophic growth factors (Table 3) following the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention.

Table 4 presents pre- and post-intervention values of anaerobic performance parameters obtained from the Wingate Anaerobic Test (WAnT) in the IPC and SHAM groups.

Physiological parameters related to maximal anaerobic capacity remained comparable in both groups before and after the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention, with no meaningful changes observed (Table 4).

Table 5 presents the results of the two-way ANOVA assessing the effects of time, group, and their interaction on circulating inflammatory marker levels in response to WAnT conducted before and after the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention. Figure 2 complements Table 5 by illustrating the time-course changes in inflammatory marker levels at baseline (Pre), immediately after exercise (Post), and 2 h after exercise (2 h Post) across both intervention conditions.

Changes in serum inflammatory factor levels in response to Wingate anaerobic test (WAnT) before and after a 14-day ischemic preconditioning (IPC) or sham (SHAM) intervention. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: (A) FSTL-1, follistatin-like 1, (B) GDF-15, growth differentiation factor 15; (C) IL-6, interleukin-6; (D) IL-10, interleukin-10; (E) IL-15, interleukin-15, (F) LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; Gray bars represent the IPC group (n = 15); black bars represent the SHAM group (n = 13). Time points: I, before the WAnT (baseline); II, immediately after the WAnT; III 2 h after the WAnT.

Study design: GR, group factor ; T, time factor; IPC, ischemic preconditioning group (n = 15); SHAM, sham-controlled group (control group, n = 13); I, before the WAnT (baseline); II, immediately after the WAnT; III 2 h after the WAnT.

Significant difference detected at * p ≤ 0.05 or ** p ≤ 0.01.

Statistical markers

* significant difference between groups at the respective time point (p < 0.05);

# significant difference vs. baseline (p < 0.05);

## significant difference vs. immediately after the WAnT (p < 0.05).

Analysis of changes in inflammatory marker concentrations (FSTL-1, GDF-15, IL-10, IL-15, and LIF) in response to the Wingate Anaerobic Test (WAnT) revealed significant time-dependent effects both before and after the intervention.

Prior to the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention, ANOVA indicated significant time effects exclusively for FSTL-1, GDF-15, and IL-10. Specifically, FSTL-1 and GDF-15 demonstrated transient increases immediately post-exercise—by 8% (p < 0.01) and 17% (p < 0.01), respectively—followed by a return to baseline within 2 h. In contrast, IL-10 levels decreased by 7% (p < 0.05) at 2 h post-WAnT compared to baseline.

After the 14-day intervention, LIF showed a significant reduction, with concentrations dropping by 15% (p < 0.05) at 2 h post-WAnT compared to immediately post-exercise values. Notably, no such time effect was observed prior to the intervention. Following the 14-day intervention, significant group × time interactions were also observed for FSTL-1, GDF-15, and IL-15, indicating a distinct response pattern in the IPC group (Fig. 2).

Post-exercise concentrations of GDF-15 and IL-15 increased significantly in the IPC group—by 25% (p < 0.05) and 28% (p < 0.05), respectively—while only minor fluctuations were observed in the SHAM group. Post hoc analysis further revealed that, immediately post-exercise, GDF-15 and IL-15 concentrations were 33% (p < 0.01) and 42% (p < 0.01) higher, respectively, in the IPC group compared to SHAM. For FSTL-1, although both groups exhibited increased concentrations immediately post-WAnT, only the IPC group showed a significant 18% reduction (p < 0.01) back to near-baseline levels at 2 h. In contrast, FSTL-1 concentrations in the SHAM group remained elevated 2 h after exercise.

Table 6 summarizes the two-way ANOVA results for neurotrophic growth factors (BDNF, IGF-1, NGF, and sAPPα), showing the effects of group, time, and their interaction across three time points before and after the IPC/SHAM intervention. Figure 3 complements Table 6 by illustrating the time-course changes in neurotrophic growth factors marker levels at baseline (Pre), immediately after exercise (Post), and 2 h after exercise (2 h Post) across both intervention conditions.

Changes in serum levels of neurotrophic growth factors in response to Wingate aneerobic test (WAnT) before and after a 14-day ischemic preconditioning (IPC) or sham (SHAM) intervention. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: (A) BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; (B) IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; (C) NGF, nerve growth factor; (D) sAPPα, soluble amyloid precursor protein-α. Gray bars represent the IPC group (n = 15); black bars represent the SHAM group (n = 13). Time points: I, before the WAnT (baseline); II, immediately after the WAnT; III 2 h after the WAnT.

Study design: GR, group factor ; T, time factor; IPC, ischemic preconditioning group (n = 15); SHAM, sham-controlled group (control group, n = 13); I, before the WAnT; II, immediately after the WAnT; III 2 h after the WAnT.

Significant difference detected at * p ≤ 0.05 or ** p ≤ 0.01.

Statistical markers

* significant difference between groups at the respective time point (p < 0.05);

# significant difference vs. baseline (p < 0.05);

## significant difference vs. immediately after the WAnT (p < 0.05).

Significant time-dependent effects were observed for BDNF, NGF, and sAPPα prior to the 14-day IPC/SHAM intervention. Specifically, BDNF and sAPPα levels increased transiently by 13% (p < 0.05) and 8% (p < 0.05), respectively, immediately post-exercise. In contrast, NGF levels showed a marked decrease following the WAnT (− 17%, p < 0.01), followed by a return to baseline within 2 h. This response pattern for NGF remained consistent after the intervention, with a 15% decrease observed immediately post-exercise (p < 0.01) and full recovery to baseline by 2 h, regardless of group assignment.

After 14 days of the IPC/SHAM intervention, significant group × time interactions were observed for BDNF, IGF-1, and sAPPα. Post hoc analysis revealed divergent recovery profiles. In the SHAM group, BDNF concentrations increased by 19% (p < 0.01) from baseline to 2 h post-WAnT, whereas in the IPC group, a decrease of 18% (p < 0.01) was noted over the same time period (Fig. 3). As a result, BDNF levels were 28% lower in the IPC group compared to SHAM at 2 h post-exercise (p < 0.01). IGF-1 concentrations showed no significant changes prior to the intervention. However, following the 14-day IPC protocol, IGF-1 levels in the IPC group increased by 30% immediately post-exercise (p < 0.05), with a subsequent return to baseline within 2 h. In contrast, no significant post-exercise changes were observed in the SHAM group. Similarly, sAPPα levels in the IPC group increased by 11% (p < 0.05) immediately after WAnT, followed by a return to baseline by 2 h. However, this pattern was not observed in the SHAM group, where sAPPα concentrations exhibited a gradual increase over the 2-h recovery period.

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that a 10-day ischemic preconditioning (IPC) protocol attenuates marathon-induced inflammation, with significantly reduced increases in serum IL-6, IL-10, FSTL-1, and resistin concentrations. These responses were associated with baseline serum iron and ferritin levels, suggesting a regulatory interaction between inflammation and iron metabolism under IPC conditions 20. Building on these findings, the current study examined whether a 14-day IPC intervention could similarly modulate inflammatory and iron-regulatory responses, as well as neurotrophic signaling, in untrained individuals subjected to anaerobic exercise. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate such biomarker modulation in this population and exercise model.

Overall, the findings suggest that the IPC intervention elicited specific physiological modulations without inducing widespread alterations across the measured variables.

Hematological parameters and most biochemical markers remained stable throughout the intervention period which may be attributed to the short duration of the intervention and the similar physical status of both groups.. Interestingly, serum creatine kinase (CK) activity decreased significantly in both IPC and SHAM groups after the 14-day intervention (− 35% and − 19%, respectively). This reduction likely reflects a familiarization effect and lower susceptibility to exercise-induced muscle damage in untrained individuals rather than a specific IPC response, consistent with previous evidence showing attenuated CK release following repeated high-intensity efforts26,27. Iron homeostasis is essential for oxygen transport, erythropoiesis, and cellular metabolism. The post-intervention increase in erythroferrone (ERFE), ferritin, and hepcidin in the IPC group reflects a coordinated regulation of iron metabolism. ERFE, secreted by erythroblasts in the bone marrow, suppresses hepcidin expression to increase iron availability for erythropoiesis28,29. The 10% rise in ERFE observed after IPC likely indicates an enhanced erythropoietic drive and systemic iron mobilization under ischemic conditions.

The concurrent elevation in ferritin—a cytosolic iron storage protein and positive acute-phase reactant suggests an adaptive response to transient hypoxic and oxidative stress induced by repeated IPC exposure30. Ferritin overexpression during ischemic and inflammatory stress is known to limit the pool of redox-active iron, thus protecting cells from oxidative injury31,32. In our study, baseline ferritin concentrations were lower in the IPC group than in SHAM, but a significant post-intervention increase persisted even after adjustment for baseline variability, confirming a genuine intervention effect. The stable serum iron levels despite elevated ferritin further indicate enhanced intracellular iron sequestration as a protective mechanism33,34.

. Although the regulatory interplay between IPC and systemic iron metabolism remains to be fully elucidated, current evidence suggests that repeated ischemia–reperfusion cycles may activate hypoxia-sensitive signaling pathways involving hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) and erythropoietin (EPO). HIF-1α–driven EPO expression stimulates erythroferrone (ERFE) release from erythroblasts, which suppresses hepcidin and enhances iron availability for erythropoiesis11,35. Thus, the observed modulation of ferritin, ERFE, and hepcidin in the IPC group likely reflects a coordinated hypoxia-dependent adaptation rather than a direct effect on iron-handling tissues36.

In contrast, serum iron concentrations increased by 33% in the SHAM group following the 14-day intervention, whereas ferritin levels remained unchanged. This dissociation may reflect physiological fluctuations in iron availability in the absence of metabolic demand, tissue repair, or oxidative challenge. It has been proposed that physical inactivity or reduced systemic inflammation may suppress hepcidin expression, leading to enhanced dietary iron absorption and increased serum iron concentrations37. The absence of coordinated ferritin upregulation in the SHAM group suggests that the iron accumulation occurred passively, rather than as part of an orchestrated adaptive response.

Taken together, these findings indicate that repeated IPC not only modulates inflammatory and muscle damage pathways, but also actively influences iron homeostasis by promoting ferritin-mediated iron sequestration. This integrative response may serve to protect against redox imbalance and facilitate metabolic adaptation to ischemic stress, especially in untrained individuals with limited physiological tolerance to systemic inflammatory and oxidative challenges.

Regarding inflammatory and neurotrophic markers, baseline concentrations remained unchanged after the intervention. However, the response to acute anaerobic exercise revealed several IPC-dependent modulations. Before the intervention, transient post-exercise increases in FSTL-1 and GDF-15 and a decrease in IL-10 were observed, consistent with typical exercise-induced inflammation. After 14 days of IPC, GDF-15 and IL-15 rose markedly immediately post-exercise (+ 25% and + 28%, respectively), while FSTL-1 declined at 2 h post-exercise, indicating an altered cytokine dynamics suggestive of tissue-protective and recovery-related regulation. GDF-15, known to be associated with mitochondrial stress and metabolic adaptation, likely reflects an adaptive response to repeated ischemic stress38,39,40.

The absence of significant IL-6 or IL-10 changes may result from the brief, supramaximal nature of the exercise, which provides an insufficient systemic inflammatory stimulus in untrained individuals. The relatively low maximal anaerobic performance of the participants could further limit the extent of cytokine activation.

Neurotrophic factors showed modified post-exercise patterns following IPC. Before the intervention, BDNF and sAPPα increased transiently, consistent with exercise-induced neurotrophic activation41. After IPC, BDNF increases were blunted, while IGF-1 and sAPPα rose significantly immediately post-exercise, suggesting enhanced neuroplasticity and recovery mechanisms. IGF-1, a regulator of neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity42, may support neural resilience, whereas the post-exercise reduction in BDNF at 2 h could reflect increased utilization in neurorepair processes43.

Despite the observed biomarker modulations, anaerobic performance parameters remained unaltered in our cohort. This is in line with several previous studies suggesting that short-term IPC does not impair maximal anaerobic capacity44. Conversely, some investigations have demonstrated improved sprint ability, higher peak power output, or enhanced Wingate test performance following IPC45,46,47. These discrepancies arise from methodological variability across studies, including IPC duration, cuff pressure, timing of post-IPC exercise, and participant training status. In untrained individuals, limited neuromuscular efficiency and reduced tolerance to supramaximal exertion may hinder the translation of molecular adaptations into measurable performance gains. Hence, IPC in this population may act primarily through protective and recovery-related mechanisms rather than immediate ergogenic enhancement. Further studies are warranted to identify conditions under which these cellular benefits can translate into functional outcomes.

In conclusion, while the overall haematological and performance measures remained stable, the IPC intervention appeared to modulate some inflammatory, iron metabolism, and neurotrophic responses to acute exercise, indicating potential benefits in adaptive recovery mechanisms and which may underlie improved recovery and cellular resilience. Further research should explore longer durations, different IPC protocols, and the translation of these biomarker responses into functional outcomes. Understanding these mechanisms can inform training strategies and clinical interventions to harness IPC’s protective effects.

Perspective and limitations

Since it is very difficult to precisely control post-exercise inflammatory and iron metabolism responses, especially in untrained individuals, the present study nonetheless provides valuable practical insights. The observed alterations in systemic iron indices may be relevant in non-training populations, in whom elevated iron levels are often associated with the progression of various inflammatory and metabolic disorders, and even neoplastic risk48,49.

In addition, the moderate reduction in inflammatory activity, regardless of its aetiology, could be beneficial for individuals unable to engage in regular physical activity due to health limitationsy50,51.

However, several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, the short-term maximal anaerobic Wingate Anaerobic Test used in this study is a standardized and widely used laboratory model of supramaximal exercise, but by its nature it tends to elicit a transient, relatively localized inflammatory and neurotrophic response rather than a prolonged systemic cytokine activation.This characteristic may partly explain the modest changes in circulating cytokines observed in the present study. Future investigations could therefore complement the present findings by employing exercise models that include a greater eccentric component and/or higher total work (for example repeated-sprint or high-volume resistance protocols). Such protocols would allow researchers to determine whether the IPC-related modulations of iron metabolism, inflammation, and neurotrophic signaling observed here are preserved across exercise modalities that impose different combinations of mechanical and metabolic stress.

Second, the interpretation of the findings is constrained by the exclusive use of systemic markers, which necessitates extrapolating local muscle responses to the systemic level. Given the compartmentalized nature of inflammation and iron metabolism, this assumption should be treated with caution. The absence of muscle biopsies further limits the ability to determine whether the observed post-exercise alterations in iron storage, inflammation, and neurotrophic factor secretion originated primarily from skeletal muscle or from systemic regulatory pathways. Considering that the IPC intervention was applied bilaterally, it is likely that both local and systemic mechanisms contributed to the overall adaptive response. Future studies employing direct muscle sampling, microdialysis, or molecular imaging could better characterize tissue-specific adaptations and clarify mechanistic pathways linking ischemic preconditioning with iron homeostasis and cytokine signalling.

Performing short-term tests of maximal anaerobic power requires full effort and is often accompanied by discomfort such as dizziness, nausea and muscle soreness. For individuals who are not regularly active, achieving maximal energy output may be difficult, and the growing symptoms of fatigue can reduce effort intensity and motivation. This likely contributed to the attrition rate of about 30%, mainly due to the inability to complete all testing sessions. Although the post-hoc power analysis confirmed adequate statistical power for the principal outcome variables, the reduced sample size may limit the generalization of the results and justifies cautious interpretation in untrained populations.

Together, these considerations indicate that the present study should be regarded as an initial step toward understanding the integrative role of ischemic preconditioning in modulating systemic and cellular homeostasis in non-training individuals. Future studies employing more targeted exercise models, extended intervention durations, and tissue-specific analyses are warranted to clarify the mechanisms underlying the observed responses and their potential practical implications.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and available from the main author of the reasonable request.

References

Howatson, G. et al. Influence of tart cherry juice on indices of recovery following marathon running. Scand J. Med. Sci. Sports. 20, 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01005.x (2010).

Suzuki, K. et al. Impact of a competitive marathon race on systemic cytokine and neutrophil responses. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.Mss.0000048861.57899.04 (2003).

Bernecker, C. et al. Evidence for an exercise induced increase of TNF-α and IL-6 in marathon runners. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 23, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01372.x (2013).

Pagani, F. D. et al. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction after infusion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in conscious dogs. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci115873 (1992).

Halon-Golabek, M., Borkowska, A., Herman-Antosiewicz, A. & Antosiewicz, J. Iron metabolism of the skeletal muscle and neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 13, 165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00165 (2019).

Mieszkowski, J. et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning reduces marathon-induced oxidative stress and decreases liver and heart injury markers in the serum. Front. Physiol. 12, 731889. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.731889 (2021).

Stankiewicz, B. et al. Effect of single high-dose vitamin D(3) supplementation on post-ultra mountain running heart damage and iron metabolism changes: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152479 (2024).

Salonen, J. T. et al. High stored iron levels are associated with excess risk of myocardial infarction in eastern Finnish men. Circulation 86, 803–811 (1992).

Kortas, J. et al. Nordic walking training attenuation of oxidative stress in association with a drop in body iron stores in elderly women. Biogerontology 18, 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10522-017-9681-0 (2017).

Kautz, L. et al. Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat. Genet. 46, 678–684. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2996 (2014).

Pirotte, M. et al. Erythroferrone and hepcidin as mediators between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Am. J. Hematol. 96, 1275–1286. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26300 (2021).

Sergio, C. M. & Rolando, C. A. Erythropoietin regulates signaling pathways associated with neuroprotective events. Exp Brain Res. 240, 1303–1315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06331-9 (2022).

Sirén, A. L. et al. Erythropoietin prevents neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemia and metabolic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98, 4044–4049. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.051606598 (2001).

Alboni, S. & Maggi, L. Editorial: Cytokines as players of neuronal plasticity and sensitivity to environment in healthy and pathological brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9, 508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2015.00508 (2016).

Vecchio, L. M. et al. The neuroprotective effects of exercise: maintaining a healthy brain throughout aging. Brain Plast. 4, 17–52. https://doi.org/10.3233/bpl-180069 (2018).

Delfan, M. et al. Enhancing cardiometabolic health: unveiling the synergistic effects of high-intensity interval training with spirulina supplementation on selected adipokines, insulin resistance, and anthropometric indices in obese males. Nutr. Metab. 21, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-024-00785-0 (2024).

Saeidi, A. et al. Resistance training, gremlin 1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor in obese men: A randomised trial. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 129, 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2020.1856142 (2023).

Thomas, D. T., Erdman, K. A. & Burke, L. M. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics, dietitians of canada, and the American college of sports medicine: Nutrition and athletic performance. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 116, 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.006 (2016).

Saeidi, A. et al. Supplementation with spinach-derived thylakoid augments the benefits of high intensity training on adipokines, insulin resistance and lipid profiles in males with obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1141796. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1141796 (2023).

Mieszkowski, J. et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on marathon-induced changes in serum exerkine levels and inflammation. Front. Physiol. 11, 571220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.571220 (2020).

Brzezińska, P. et al. Direct effects of remote ischemic preconditioning on post-exercise-induced changes in kynurenine metabolism. Front. Physiol. 15, 1462289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1462289 (2024).

Bar-Or, O. The Wingate anaerobic test. An update on methodology, reliability and validity. Sports Med. 4, 381–394. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198704060-00001 (1987).

Kochanowicz, A. et al. Cellular stress response gene expression during upper and lower body high intensity exercises. PLoS ONE 12, e0171247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171247 (2017).

Kochanowicz, A. et al. Acute inflammatory response following lower-and upper-body Wingate anaerobic test in elite gymnasts in relation to iron status. Front. Physiol. 15, 1383141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1383141 (2024).

Cabral-Santos, C. et al. Inflammatory cytokines and BDNF response to high-intensity intermittent exercise: Effect the exercise volume. Front. Physiol. 7, 509. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00509 (2016).

Clarkson, P. M. & Hubal, M. J. Exercise-induced muscle damage in humans. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81, S52-69. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200211001-00007 (2002).

Hyldahl, R. D. & Hubal, M. J. Lengthening our perspective: Morphological, cellular, and molecular responses to eccentric exercise. Muscle Nerve. 49, 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.24077 (2014).

Ganz, T. et al. Immunoassay for human serum erythroferrone. Blood 130, 1243–1246. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-04-777987 (2017).

Reichert, C. O. et al. Hepcidin: homeostasis and diseases related to iron metabolism. Acta Haematol. 137, 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1159/000471838 (2017).

Kell, D. B. & Pretorius, E. Serum ferritin is an important inflammatory disease marker, as it is mainly a leakage product from damaged cells. Metallomics 6, 748–773. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3mt00347g (2014).

Mieszkowski, J. et al. Ferritin genes overexpression in PBMC and a rise in exercise performance as an adaptive response to ischaemic preconditioning in young men. Biomed Res. Int. 2019, 9576876. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9576876 (2019).

Brancaccio, P., Maffulli, N. & Limongelli, F. M. Creatine kinase monitoring in sport medicine. Br. Med. Bull. 81–82, 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm014 (2007).

Antosiewicz, J., Ziolkowski, W., Kaczor, J. J. & Herman-Antosiewicz, A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced reactive oxygen species formation is mediated by JNK1-dependent ferritin degradation and elevation of labile iron pool. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.023 (2007).

Borkowska, A. et al. JNK/p66Shc/ITCH signaling pathway mediates angiotensin II-induced ferritin degradation and labile iron pool increase. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030668 (2020).

Liu, Q., Davidoff, O., Niss, K. & Haase, V. H. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates hepcidin via erythropoietin-induced erythropoiesis. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 4635–4644. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci63924 (2012).

Li, Y., Huang, X., Wang, J., Huang, R. & Wan, D. Regulation of iron homeostasis and related diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 6062094. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6062094 (2020).

Constantini, N. W., Eliakim, A., Zigel, L., Yaaron, M. & Falk, B. Iron status of highly active adolescents: Evidence of depleted iron stores in gymnasts. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 10, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.10.1.62 (2000).

Dinh, W. et al. Growth-differentiation factor-15: A novel biomarker in patients with diastolic dysfunction?. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 97, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000058 (2011).

Xu, X. et al. Follistatin-like 1 as a novel adipomyokine related to insulin resistance and physical activity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa629 (2020).

Fischer, M. J. et al. Evaluation of mitochondrial function in chronic myofascial trigger points—A prospective cohort pilot study using high-resolution respirometry. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19, 388. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2307-0 (2018).

Voss, M. W. et al. Neurobiological markers of exercise-related brain plasticity in older adults. Brain. Behav. Immun. 28, 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.021 (2013).

Carro, E., Trejo, J. L., Gomez-Isla, T., LeRoith, D. & Torres-Aleman, I. Serum insulin-like growth factor I regulates brain amyloid-beta levels. Nat. Med. 8, 1390–1397. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1202-793 (2002).

Karege, F., Schwald, M. & Cisse, M. Postnatal developmental profile of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rat brain and platelets. Neurosci. Lett. 328, 261–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00529-3 (2002).

Paradis-Deschênes, P., Joanisse, D. R. & Billaut, F. Ischemic preconditioning increases muscle perfusion, oxygen uptake, and force in strength-trained athletes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 41, 938–944. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0561 (2016).

de Groot, P. C., Thijssen, D. H., Sanchez, M., Ellenkamp, R. & Hopman, M. T. Ischemic preconditioning improves maximal performance in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 108, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1195-2 (2010).

Salvador, A. F. et al. Ischemic preconditioning and exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 11, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0204 (2016).

Kochanowicz, M. et al. Single and consecutive 10-day remote ischemic preconditioning modify physical performance, post-exercise exerkine levels, and inflammation. Front Physiol. 15, 1428404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1428404 (2024).

Fleming, R. E. & Ponka, P. Iron overload in human disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1004967 (2012).

Prá, D., Franke, S. I., Henriques, J. A. & Fenech, M. Iron and genome stability: An update. Mutat. Res. 733, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.02.001 (2012).

Ohshima, H., Tazawa, H., Sylla, B. S. & Sawa, T. Prevention of human cancer by modulation of chronic inflammatory processes. Mutat. Res. 591, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.030 (2005).

Calder, P. C. et al. Inflammatory disease processes and interactions with nutrition. Br. J. Nutr. 101(Suppl 1), S1-45. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114509377867 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the members of the Student Research Group of Extreme Physiology at the Academy of Lomza and the Student Scientific Club of Research Innovations in Sports at the Gdańsk University of Physical Education and Sport for their valuable contributions to this study. Their dedication, technical support, and active involvement in the research procedures were instrumental in the successful completion of this project.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Student Science Clubs Create Innovations” Grant Program from the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education, Poland (No. SKN/SP/602410/2024), and by the Polish Minister of Science under the “Regional Initiative of Excellence” programme. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement and policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB, AK, AB, KG, MK, BS, JA and JM contributed to the conceptualization, PB, AK, KG AB, AD, JH, JA and JM contributed to the methodology, writing of the original draft and editing. PB, JM, AK, KG, AD, JH, BS and BM contributed to the investigation, JM, AK contributed to the project administration. JM, AK contributed to the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Physical Education and Sport in Gdańsk (Resolution No. 2, dated December 16, 2024) and complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed about the aims and procedures of the study and provided written informed consent before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brzezińska, P., Kochanowicz, A., Borkowska, A. et al. Ischemic preconditioning modulates iron metabolism, acute inflammatory and neurotrophic responses to anaerobic exercise in untrained individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 16, 7258 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36790-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36790-x