Abstract

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are well-known for their distinctive optical, electronic, and antimicrobial properties, enabling versatile applications in biosensors, photonics, electronics, drug delivery, and antimicrobial treatments. The biological synthesis approach offers a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to traditional physical and chemical methods. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles synthesized from plant extracts are emerging as promising agents with notable medicinal potential. This study presents a cost-effective, simple, and eco-friendly approach for synthesizing silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) through the reduction of Ag+ ions to metallic silver (Ag0) using an aqueous extract of Alcea rosea leaves. The synthesized nanoparticles were characterized using various techniques, including UV–visible, FTIR, XRD, FESEM, and EDX. Biological activities were evaluated for their antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer assays. The AgNPs demonstrated moderate antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella sonnei, as evidenced by moderate minimum inhibitory and bactericidal concentrations, and mild DPPH free radical scavenging activity with an IC50 value of 80.05 ± 1.53 µg/mL. The nanoparticles exhibited significant anticancer activity against cervical cancer cell lines, with an IC50 of 54.46 ± 1.67 µg/mL. These findings suggest that the synthesized AgNPs have promising potential for medical applications, especially in drug development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanotechnology is a rapidly evolving scientific discipline focused on designing and manipulating materials at the nanometer scale (approximately 1–100 nm) to achieve novel structural and functional properties1. Noble metal nanoparticles have recently garnered significant attention due to their unique physicochemical behaviour, including optical, electrical, magnetic, and catalytic characteristics that are distinct from those of bulk materials2. These characteristics are primarily driven by quantum size effects and a very high surface-to-volume ratio. As a result, metallic nanoparticles are currently used in various fields, including photonic materials, electronic devices, and catalytic processes3. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, such as Cu, Fe, TiO2, CdS, Ag, Au, and Zn, exhibit distinctive physicochemical behaviours4. Among these, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have attracted considerable attention due to their unique properties, such as optical and magnetic polarizability5, electrical conductivity6, catalytic efficiency7, antibacterial activity8, and applications in DNA sequencing9. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) can be synthesized using different approaches, including chemical, electrochemical, and microwave-assisted procedures. However, many of these methods require hazardous chemicals and consume more energy, making the purification process difficult. Eco-friendly techniques have been developed by integrating biological principles into the synthesis process to overcome these constraints10. Naturally occurring sugars, polysaccharides, alkaloids, and flavonoids in plant extracts serve as environmentally safe reducing and capping agents in the green synthesis of AgNPs11.

Alcea rosea, also known as hollyhock, is a common ornamental plant in the Malvaceae family, which is distinguished by its large, colourful flowers. It is thought to have started in China or the tropical regions of Southeast Asia. Numerous pharmacological tests have demonstrated its analgesic, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties12. The roots of A. rosea have been used in Iranian traditional medicine to treat various conditions, including bronchitis, diarrhea, constipation, inflammation, and severe coughing13. Research on various Alcea species through ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology indicates that they may be used to treat a variety of illnesses. In herbal medicine, A. rosea is also used to treat snake bites, jaundice, malaria, rheumatism, and renal and urinary tract infections, as well as digestive disorders accompanied by vomiting and diarrhoea14.

Various plant extracts, including those from Dalbergia spinosa, Buddleja globosa, and Argemone mexicana, have been reported in the literature for the green synthesis of AgNPs. In this study, A. rosea leaf extract was used to synthesize AgNPs, which were characterized using UV–visible spectroscopy, FTIR, XRD, FESEM, and EDX. In addition, the synthesized nanoparticles were tested for their anticancer, antioxidant, and antibacterial activity. The main plant components, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, phenolic compounds, terpenoids, and other secondary metabolites, acted as both stabilizing (capping) and reducing agents during the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using A. rosea extract. Silver ions (Ag+) can be converted into metallic silver (Ag0) nanoparticles by electron donation from functional groups- OH, C=O, and NH2 present in these compounds. For example, flavonoids and phenolic compounds are strong antioxidants that can donate electrons or hydrogen atoms to this reduction process. Other biomolecules, such as proteins, polysaccharides, or alkaloids, also attach to the surface of the nanoparticles after their formation, creating a protective organic layer that not only prevents aggregation but also controls particle size. The biological capping molecules provide durability, size and shape uniformity, and better dispersibility of the nanoparticles in the solvent. As a result of this biological capping, the various phytochemicals of A. rosea extract not only participate in silver ion reduction but also control the shape and long-term stability of the synthesized nanoparticles15,16,17. To the best of our knowledge, little is known about the synthesis of AgNPs using leaf extract from A. rosea. This study might be the first to describe the synthesis of AgNPs for various biological applications utilizing A. rosea leaf extract. Figure 1a shows the A. rosea plant, while Fig. 1b highlights some of the active chemical compounds present in its leaves, which are responsible for reducing and stabilizing AgNPs during synthesis.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and instruments

The glassware in this study was made from Type 1 Class borosilicate glass. It included beakers, funnels, test tubes, Falcon tubes, volumetric flasks, 96-well microdilution plates, and conical flasks. The equipment utilized comprised a microplate reader (Epoch 2, Biotek Instruments, Inc., USA), a water bath (Clifton), a hot air oven (Griffin–Grundy), and a pH meter. Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB), neomycin, and resazurin were supplied by HiMedia (LOBA CHEMI Pvt. Ltd), while Nutrient Agar (NA) was also used. Various chemicals and reagents used in the bioassays included methanol, quercetin, ascorbic acid, and DPPH reagents. All were obtained from Merck and Sigma. Additionally, MTT reagent and LB powder from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, in India, were among other reagents used in this study.

Plant sample collection and preparation of aqueous extract

A. rosea were collected from the Kailali district, Nepal, on February 15, 2025. The coordinates of the collection site are 28° 49′ N and 80° 53′ E. The plant specimen was identified by experts at the Department of Botany, Dhangadhi, Kailali, on February 28, 2025. After collection, the leaves were carefully cleaned, dried in the shade, and ground into a fine powder using a grinding mixture. In a beaker, precisely 20 grams of the powder were dissolved in 200 mL of distilled water. The mixture was then heated to 50 °C for one hour and stirred using a hot magnetic stirrer. From 20 g of dried leaf powder, 0.8 g of dried extract was obtained, giving an extract yield of 4 %. The extract solution was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper (pore size 11 µm) to remove particulate matter. The concentrated extract was stored in an airtight amber vial at 4 °C and used within 1 week of preparation18.

Plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles

A 1:20 ratio of aqueous leaf extract to 0.2 M AgNO3 solution was used, and the mixture was placed on a magnetic stirrer for 20 minutes. The pH was then adjusted to 11 by adding 0.1 M NaOH and monitored with a calibrated digital pH meter. At room temperature, the reaction was stirred for an additional hour. The formation of AgNPs was indicated by a color change of the reaction mixture from pale yellow/brown to deep brown. Time, pH, and extract-to-metal ratio are examples of reaction parameters that were adjusted to control nucleation, growth, and stabilization since they have a significant impact on colloidal stability, uniformity, and particle size19.

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the nanoparticles was evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, with slight modification to previously reported protocols, where we assessed the ability of nanoparticles to suppress free radicals20. A 96-well plate reader modified from the colorimetric approach was used to measure the antioxidant activity. Each of the 96-well plates received 100 µL of nanoparticle solution. The initial reading was taken at 517 nm. Each 96-well plate was then filled with 100 µL of DPPH. Using a microplate reader, the final reading was taken at 517 nm. GraphPad Prism software was used to calculate the IC50 value.

where Acontrol = absorbance of the control, and Asample = absorbance of the sample.

Antibacterial assay

The agar well diffusion assay, with minor modifications, was used to evaluate the antibacterial activity21. Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) was used for the preparation of the bacterial inoculum. Commercially available Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) was dissolved in distilled water, heated, autoclaved, transformed into sterile Petri plates, and allowed to solidify. Following the solidification of the agar, several bacterial strains were added to the plates, and their concentrations were adjusted according to the McFarland standard (104 CFU/mL). The test samples were added to wells that had been carefully drilled into the agar together with a negative control (50% DMSO) and a positive control (neomycin). Each well received 60 μL of AgNPs(50 μg/mL), and the positive control was utilized at the same concentration. The inoculated petri plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours, and the zone of inhibition (ZOI) was measured using a scale. The assay were performed in duplicate, and the zone of inhibition values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The CLSI recommendations were followed in all antibacterial tests.

Resazurin microtiter assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of nanoparticles were calculated using a resazurin microtiter test22. Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Shigella sonnei were used as the test organisms. In each well of a 96-well microtiter plate, 100 μL of double-strength Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) was added, followed by the addition of 100 μL of the sample of nanoparticles to each well in the first row. After which, all wells were serially diluted by half from A to H, as indicated below. All samples were inoculated with 10 μL of bacterial culture (0.5 McFarland) and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Five microliters of 0.3 % resazurin were subsequently added to each well, after which the plate was incubated for an additional two hours. As a growth indicator, resazurin was utilized; pink wells showed bacterial growth, while blue wells showed no growth. The lowest concentration that prevented color change was MIC. Finally, 50 μL solutions were added to Mueller–Hinton broth agar plates to determine the MBC of the sample.

MTT assay

Cytotoxicity of Ag NPs was evaluated against cervical cancer (HeLa) and lung cancer (A549) cell lines using the MTT assay23. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) was used to seed 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate, which was incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, different concentrations of Ag NPs (400 to 50 μg/mL) were added, followed by a 48-hour incubation. Following treatment, the supernatant was carefully removed, and 100 μL of fresh DMEM, along with 20 μL of MTT solution (5 μg/mL), was added to each well. After 4 hours of incubation, purple formazan crystals were observed. These were subsequently dissolved by adding 100 μL of DMSO per well and incubating for 15 minutes at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. Each treatment was performed in triplicate, and each measurement was made in triplicate wells. GraphPad Prism was used to calculate the IC50 values. Positive control experiments were performed using cisplatin and doxorubicin under the identical experimental circumstances as the test substances.

The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula:

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control, and Asample is the absorbance of the sample.

Characterization of silver nanoparticles

UV–visible spectroscopy

There was a significant change in the colour of the solution, which turned brownish. This indicates the formation of AgNPs. The preliminary confirmation of AgNPs can be observed through the absorption that occurred in the UV–visible spectra between 300 and 600 nm. It was measured using a UV spectrophotometer [SPECORD 200 PLUS, (An Endress+Hauser Company)].

FTIR spectroscopy

Phytochemicals that had absorbed onto the nanoparticles and organic functional groups found in the aqueous extract were analysed using FTIR Spectroscopy (by PerkinElmer UV/VIS Lambda 365 Spectrophotometer) between 400–4000 cm⁻1. The presence of particular IR peaks at specific wave numbers shows that these compounds played a role in the synthesis and/or stabilization of the Metal Nanoparticles. Origin 2024 software was used to perform spectral smoothing and baseline correction.

XRD analysis

The crystallographic structure, grain size, and diffraction pattern of biosynthesized AgNPs were characterized through X-ray Diffraction Analysis (D2 Phaser) (Bruker, NAST, Nepal) at 30 kV Cu Kα with a 1.54 A° wavelength. The X-ray data were recorded within the 20°–80° range of 2θ. The average crystallite size of AgNPs was determined using the Scherrer Formula.

where, D = crystallite size of the particles in nm; k = dimensionless and has a value of almost one (0.9); β = FWHM, in radians; λ = wavelength of X-ray (0.15406 nm for Cu Kα); θ = Bragg’s angle (in radians).

FESEM analysis

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) (SU equipment, Korea) was employed to examine the surface morphology, grain size, and other physical properties of the biosynthesized AgNPs. The particle sizes were quantified using ImageJ software.

EDX analysis

The elemental composition of the synthesized AgNPs was examined using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy.

Statistical analysis

The results of the duplicate and triplicate tests were displayed as mean ± standard deviation. GraphPad Prism was used to calculate the IC50 and create accompanying graphs for the DPPH and MTT assays. FTIR, XRD, and UV–visible spectra were plotted using Origin. SEM images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Results and discussion

Nanoparticles possess many advantages in scientific research due to their large surface area and high reactivity. Green-synthesized AgNPs are promising materials that have been widely explored to address several modern biological, industrial, and environmental challenges. In this study, AgNPs synthesized using the aqueous extract of A. rosea were characterized using UV–vis spectroscopy, FTIR, XRD, SEM, and EDX techniques. The nanoparticles were evaluated for potential applications, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cancer treatment. The different sections of this report provide a comprehensive discussion of these findings.

UV–vis spectroscopy

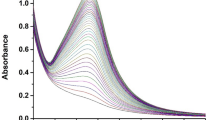

UV–visible spectroscopy is recognized as a vital analytical method that serves both qualitative and quantitative approaches. It is a rapid, preliminary technique commonly used to confirm the successful synthesis of nanoparticles derived from leaf extracts. The phytochemicals in leaf extracts act as reducing agents, which change metal ions into nanoparticles, and at the same time, the process of their formation, stabilization, and surface capping is facilitated. The biosynthesized AgNPs showed peak absorbance at 411 nm, which is in line with the results from previous research24. This absorption behaviour arises from the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, leading to surface plasmon resonance (SPR)25. Typically, AgNPs exhibit a distinct surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak in the range of 400 to 450 nm, confirming their successful formation26. The UV–vis absorption spectrum of the synthesized nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 2.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy was performed on the synthesized AgNPs and their leaf aqueous extracts. The changes in peak positions and intensities between the FTIR spectra of the AgNPs and leaf extract have confirmed the involvement of plant secondary metabolites in the synthesis of nanoparticles. An IR peak at 3670 cm⁻1 in plant extract is generally indicative of an (O–H) group, particularly a free or weakly hydrogen-bonded O–H stretching. It may be connected to alcoholic and phenolic substances, which act as reducing and capping agents during nanoparticle formation27. The vibrational peaks around 3359 cm⁻1 are most likely due to the O–H stretching vibration of an alcohol or carboxylic acid, or potentially the N–H stretching vibration of an amine28. The C–H stretching vibration is visible in the peak projected at 2914 cm⁻1, which might be due to the presence of terpenoids29. The stretching of the C–N group may be associated with the peak at about 1061 cm⁻1, whereas the stretching of the C–H group may be associated with the peak at 1403 cm⁻130. The FTIR spectra detected a characteristic peak at about 506 cm⁻1, which might have been caused by the stretching of the Ag nanostructure31. The outcome of the FTIR analysis implies the presence of these peaks, which are in accordance with the earlier reports, thus identifying a promising correlation that further supports our study32. Fig. 3 displays the FTIR spectra of the biosynthesized AgNPs and the leaf aqueous extract.

XRD analysis

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is an analytical technique that provides information regarding the crystalline characteristics of nanoparticles. The Debye–Scherrer equation is commonly used to determine the average crystallite size from the most intense XRD diffraction peak.

where k is the shape factor (taken as 0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (0.15406 nm), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak in radians, and θ is Bragg’s diffraction angle (in radians). The crystallite size was determined using the most intense diffraction peak at 2θ = 38.3º, for which the measured FWHM was β = 1.56º (0.0272 rad)33,34,35. Using Debye–Scherrer’s equation, the average crystallite size was calculated as 5.38 nm. A single strong and well-resolved peak was selected for the Scherrer analysis because it provides the highest signal-to-noise ratio and yields the most reliable FWHM measurement, which is standard practice. The diffraction peaks observed at 38.3º, 44.6º, 68.8º, and 77.6º correspond to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes of the face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure (JCPDS card 04-0783)36. The obtained XRD data are consistent with the previously published studies that validate the cubic structure of silver nanoparticles37,38. Comparable XRD patterns were found in Erigeron bonariensis39 and Alternaria solani40. The calculated crystallite size obtained from X-ray diffraction (XRD) is notably smaller than the particle size measured by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). The FESEM likely captures the entire particles, which may consist of multiple crystals, while XRD focuses specifically on the size of individual crystalline domains within those particles. This distinction highlights the unique strengths of each technique and the complementary information they offer in material analysis41. Fig. 4 displays the XRD spectra of the synthesized Ag NPs.

FESEM analysis

The morphological size and shape of AgNPs produced by the leaf aqueous extract of A. rosea were analyzed through the FE-SEM. With sizes ranging from 22 to 64 nm, the produced AgNPs were mostly spherical. The FE-SEM image with a 500 nm scale bar, which exhibited the maximum resolution, was used for particle-size measurements. A total of 52 nanoparticles were analyzed, and the average particle size was determined to be 35.37 nm. In the UV–visible spectra of biosynthesized AgNPs, a single SPR peak indicates the formation of spherical particles, which is further confirmed by the SEM image42. Reports have been made of the biosynthesis of spherical and smooth nanoparticles in Rheum emodi43 and the honey-mediated green synthesis of AgNPs44. The electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonding between the bioinorganic capping molecules attached to the AgNPs assist in the development of the SEM image. It is shown that some individual particles appear nearly spherical, but the SEM reveals a considerable degree of aggregation, making it challenging to determine their exact shape. Strong interparticle interactions and the presence of phytochemical capping agents, which encourage clustering, may be the cause of the aggregation45. The particle size is displayed in Fig. 5 at various resolutions from the FE-SEM picture, and a histogram of particle size distribution is shown in Fig. 6.

EDX analysis

The purity of AgNPs was examined using EDX color mapping, as shown in Fig. 7, which shows the necessary phases of carbon, oxygen, and silver in Fig. 8. The spectra revealed the existence of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and silver (Ag) as major elements, as shown in Table 1. For C, O, and Ag, the corresponding atomic percentages were 23.41%, 65.11%, and 11.49%, whereas the weight percentages were 10.97%, 40.66%, and 48.37%, respectively. The presence of Ag indicates successful nanoparticle formation, and high oxygen level probably reflects the stabilizing and capping phytochemicals form the plant extract.

Application of biosynthesized Ag nanomaterials

Antioxidant potential

The antioxidant potential of the synthesized AgNPs was assessed through the DPPH assay. Since DPPH can accept hydrogen, it can be used for assessing antioxidant activity46. It quickly accepts electrons from the antioxidant substance, thus turning the solution from violet to yellow47. In this manner, the DPPH free radical is converted into a stable diamagnetic molecule via reduction. In the current research, the radical-scavenging activity of AgNPs against DPPH increased with increasing concentration and reached maximum at higher concentrations. As shown in Table 2, the AgNPs exhibited an IC₅₀ value of 80.05 ± 1.53 μg/mL, while the standard reference compound quercetin showed a significantly lower IC₅₀ of 3.55 ± 1.61 μg/mL. The results indicate a significant scavenging effect dependent on the dose, even though the concentration of the AgNPs was at a lower level, thus verifying the antioxidant capability of the nanoparticles48. The stabilization of nanoparticles and additional bioactivities may be attributed to the presence of hydroxyl groups in flavonoids. Observed antioxidant effect may arise from mechanisms such as single-electron transfer, hydrogen donation, or metal ion chelation49. Pearson correlation analysis revealed a substantial and statistically significant negative correlation between absorbance and percent inhibition (r = -̅1.000, p < 0.01). The antioxidant effectiveness of the synthesized AgNPs is further confirmed by this inverse relationship, which shows that a decrease in absorbance is directly linked to an increase in free radical scavenging activity.

In vitro antibacterial potential

Agar well diffusion method

The antibacterial activity of biosynthesized AgNPs was assessed against four bacterial strains (S. aureus, S. sonnei, K. pneumoniae, and E. coli) using the agar well diffusion method. As shown in Table 3, AgNPs demonstrated antibacterial activity against all tested bacteria, with stronger effects against S. aureus and S. sonnei than against K. pneumoniae and E. coli, while neomycin consistently exhibited higher inhibitory activity. The unlabeled wells correspond to additional AgNPs samples evaluated in the assay. This pattern is consistent with other research that found Gram-positive bacteria are more vulnerable to green-synthesized AgNPs than Gram-negative bacteria50,51. Several mechanisms contribute to the antibacterial activity: (i) the dissolution of Ag⁺ ions, which interact with proteins that contain thiols and interfere with vital metabolic processes; (ii) the phytochemical-capped nanoparticles directly adherence to the bacterial cell wall, which disrupts the localized membrane; and (iii) increased intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes oxidative stress and damage to DNA and proteins. By facilitating binding to bacterial surfaces, the phytochemical elements that stabilize and reduce AgNPs may also improve the bactericidal response as a whole. When combined, these processes provide green-synthesized Ag NPs with their remarkable antibacterial power, making them attractive options for antimicrobial and medicinal uses, especially against infections that are resistant to drugs52. Fig. 9, depicts the antibacterial action of AgNPs, which involves membrane disruption intracellular penetration, ROS generation, and interference with vital cellular components, culminating in bacterial cell deaths. The representative plates displaying the antibacterial activity are shown in Fig. 10.

Proposed antibacterial mechanisms of AgNPs against bacterial cells.

MIC and MBC

The resazurin microtiter assay was used to assess the MIC and MBC of the synthesized AgNPs against the Gram-positive S. aureus and the Gram-negative S. sonnei. In metabolically active cells, the NADH dehydrogenase enzyme reduces the blue dye resazurin to the pink chemical resorufin. Since this enzyme is only present in viable cells, the assay serves as an effective method for assessing cell viability53. MIC and MBC of nanoparticles against S. aureus and S. sonnei are 6.25 µg/mL and 12.5 µg/mL, respectively. The produced AgNPs had relatively high MIC (6.25 µg/mL) and MBC (12.5 µg/mL) values when compared to a number of other green-synthesized silver nanoparticles. This implies that our AgNPs have a relatively reduced antibacterial efficacy. Variations in particle size, surface chemistry, and the nature of capping phytochemicals have been identified as reasons for these discrepancies. The abundance of organic chemicals generated from plants on the surface of the nanoparticles may have decreased the amount of active Ag⁺ ions available in our investigation, which would have decreased the antibacterial activity. AgNPs synthesized from Pogonatherum crinitum leaf extracts demonstrated comparable MIC and MBC values, according to the literature54. The MIC and MBC of the positive control neomycin against S. aureus and S. sonnei were found to be 0.78 µg/mL and 1.56 µg/mL, respectively. Table 4 presents the MIC and MBC values of the synthesized AgNPs and Neomycin, while the corresponding MIC assay plates are shown in Fig. 11, and the MBC assay plates in Fig. 12.

Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxic effects of biosynthesized AgNPs on A549 and HeLa cell lines were assessed in vitro using an MTT assay. IC50 values of AgNPs and standard drugs against various cancer cell lines are shown in Table 5. Representative photographs showing morphological changes in the HeLa and A549 cells before and after treatment with AgNPs at different concentration are presented in Fig. 13. Ag NPs at concentrations of 400 µg/mL, 200 µg/mL, 100 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL were applied to both cancer cells for 48 h, resulting in a clear dose-dependent inhibition of the cancer cells. Based on our findings, AgNPs show significant anticancer potential. As the concentration of AgNPs decreased, their anticancer capability also reduced. The results showed a dose-dependent inhibition, with the greatest inhibition being 39.37% for A549 and 49.07% for HeLa cell mortality at 400 µg/mL. The calculated IC50 values for A549 and HeLa were 54.46 ± 1.67 µg/mL and 92.93 ± 1.05 µg/mL, respectively, confirming the excellent therapeutic potential of AgNPs. Standard chemotherapeutic drugs were employed as positive controls to validate the assay. These data demonstrate that the nanoparticles possess substantial antiproliferative capability, notably against HeLa cells. Cisplatin revealed an IC₅₀ value of 56.74 ± 0.96 µg/mL, whereas doxorubicin showed an IC₅₀ value of 76.22 ± 0.33 µg/mL. These findings are consistent with previously reported results for the A549 cancer cell line55. Mechanistically, AgNPs employ several interconnected mechanisms to achieve their anticancer effects. One important mechanism of action is the compromise of mitochondrial integrity, resulting in reduced membrane potential and impaired oxidative phosphorylation. Because cancer cells are already metabolically dysregulated, they find it difficult to combat the oxidative stress caused by this mitochondrial malfunction, which leads to an excessive production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Elevated ROS levels subsequently activate intrinsic apoptotic mechanisms, including caspase-mediated DNA breakage and chromatin condensation, ultimately leading to programmed cell death. When taken as a whole, these pathways demonstrate AgNPs diverse cytotoxic capabilities and lend credence to their increasing acceptance as viable cancer treatment options. Furthermore, these processes might be further altered or improved in conjunction with the stabilizing and bioactive phytochemicals found in green-synthesised nanoparticles, which would help explain the selective toxicity noted in a number of investigations56. For both cell lines (A549: r = − 0.998, p < 0.01; HeLa: r = − 1.000, p < 0.01), Pearson correlation analysis showed a strong and statistically significant negative correlation between absorbance and percentage inhibition. This suggests that lower absorbance is directly linked to higher cytotoxic activity of AgNPs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a biological method for synthesizing AgNPs, using an aqueous extract of A. rosea, which is simpler, cost-effective, and inspired by nature. Formation of AgNPs was confirmed using various methods, such as UV–vis spectroscopy, FTIR, XRD, FE-SEM, and EDX analysis. The biosynthesized AgNPs showed moderate antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella sonnei, and moderate MIC and MBC values were obtained for both strains. Also, the synthesized AgNPs showed low antioxidant activity compared to the standard compound. Biogenic AgNPs also demonstrated good anticancer effects against both tested cell lines. This study emphasizes the importance of Nepalese medicinal herbs as an important resource for developing nanotechnology and the potential of secondary metabolites obtained from plants in the environmentally friendly synthesis of metal nanoparticles. The resultant AgNPs, which have been shown to possess antioxidant, antibacterial, and anticancer properties, present encouraging prospects for biomedical uses, including antimicrobial coatings, wound dressings, therapeutic formulations, and cancer treatment methods. Furthermore, they are appropriate for environmental uses such as surface disinfection, water purification, and pollutant monitoring due to their potent antibacterial and redox characteristics. These opportunities highlight the wider applicability of green-synthesized nanoparticles and motivate more research into their potential applications. However, the present work is limited by the lack of hydrodynamic size, zeta potential, and colloidal stability measurements, which were not possible due to the absence of DLS instrumentation. These characteristics are vital for determining dispersion stability, particularly in biomedical applications. Comprehensive DLS, zeta potential, and long-term stability investigations will be included in further studies to give a deeper comprehension of the colloidal behavior of the produced AgNPs. Additionally, the plant material could not be allocated a voucher specimen number because the authenticating institution does not issue specimen codes, which we admit as a methodological limitation.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Luo, G., Du, L., Wang, Y. & Wang, K. Manipulation and control of structure and size of inorganic nanomaterials in microchemical systems. Chem. Eng. Technol. 42, 1996–2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.201900067 (2019).

Mazur, M. Electrochemically prepared silver nanoflakes and nanowires. Electrochem. Commun. 6, 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2004.02.011 (2004).

Khursheed, R. et al. Biomedical applications of metallic nanoparticles in cancer: Current status and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 150, 112951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112951 (2022).

Jamkhande, P. G., Ghule, N. W., Bamer, A. H. & Kalaskar, M. G. Metal nanoparticles synthesis: An overview on methods of preparation, advantages and disadvantages, and applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 53, 101174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101174 (2019).

Taleb, A., Russier, V., Courty, A. & Pileni, M. P. Collective optical properties of silver nanoparticles organized in two-dimensional superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 59, 13350–13358. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.13350 (1999).

Alshehri, A. H. et al. Enhanced electrical conductivity of silver nanoparticles for high-frequency electronic applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 7007–7010. https://doi.org/10.1021/am3022569 (2012).

Jiang, Z. J., Liu, C. Y. & Sun, L. W. Catalytic properties of silver nanoparticles supported on silica spheres. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 1730–1735. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp046032g (2005).

Tang, S. & Zheng, J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: Structural effects. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 7, 1701503. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201701503 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. DNA sequence-dependent morphological evolution of silver nanoparticles and their optical and hybridization properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15195–15202. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja506150s (2014).

Ravichandran, V. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Artocarpus altilis leaf extract and study of their antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Mater. Lett. 180, 264–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2016.05.172 (2016).

Raveendran, P., Fu, J. & Wallen, S. L. Completely, “green” synthesis and stabilization of metal nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13940–13941. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja029267j (2003).

Dar, P. A. et al. Amelioration of hyperglycemia and modulation of antioxidant status by Alcea rosea seeds in diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol. 55, 1849–1855. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2017.1333127 (2017).

Ahmadi, M. et al. Alcea rosea root extract as a preventive and curative agent in urolithiasis. Indian J. Pharmacol. 44, 304–309. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7613.96298 (2012).

Raffi Shehzad, M. et al. Hollyhock. In Medicinal Plants of South Asia 381–391 (Elsevier, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102659-5.00029-X

Muniyappan, N. & Nagarajan, N. S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Dalbergia spinosa leaves. Process Biochem. 49, 1054–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2014.03.015 (2014).

Carmona, E. R. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Buddleja globosa leaf extract. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 10, 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2017.1360400 (2017).

Oni, B. A. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antibiotic removal from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Manage. 342, 118161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118161 (2023).

Hashemi, Z., Shirzadi Ahoodashti, M. & Ebrahimzadeh, M. A. Antileishmanial and antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Alcea rosea. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 6, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.22090/jwent.2021.03.007 (2021).

Regmi, B. et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 220–226. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijasbt.v9i3.39069 (2021).

Bhandari, D. P. et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of citrus essential oils from Nepal. Molecules 26, 6683. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216683 (2021).

Abbey, T. C. & Deak, E. What’s new from the CLSI subcommittee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing 29th edition. Clin. Microbiol. Newslett. 41, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2019.11.002 (2019).

Sarker, S. D., Nahar, L. & Kumarasamy, Y. Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth. Methods 42, 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.006 (2007).

Krishnaraj, C. et al. Acalypha indica Linn: biogenic synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their cytotoxic effects. Biotechnol. Rep. 4, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2014.08.002 (2014).

Tyagi, P. K. et al. Ascorbic acid and polyphenol-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Tagetes erecta L. J. Nanomater. 2021, 6515419. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6515419 (2021).

Khoshnamvand, M. et al. Biomimetic synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Alcea rosea leaf extract. J. Mol. Struct. 1179, 749–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.11.079 (2019).

Kamarudin, D. et al. Synthesis of PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles for polymeric membrane applications. Mater. Technol. 37, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10667857.2021.1908768 (2022).

Stozhko, N. et al. Green silver nanoparticles: plant-extract-mediated synthesis and properties. Physchem 4, 402–419. https://doi.org/10.3390/physchem4040028 (2024).

Mohamad Kasim, A. S. et al. Interrelations of synthesis method and polyethylene glycol coating on silver nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 10, 2475. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10122475 (2020).

Jonuškienė, I. et al. Eco-friendly biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Zinnia elegans L. Sustainability 17, 9451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219451 (2025).

Abambagade, A. M. & Belete, Y. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Moringa stenopetala. Afr. J. Biotech. 16, 1705–1716. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2017.16010 (2017).

Barzinjy, A. A. & Haji, BSh. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Portulaca oleracea. Micro Nano Lett. 19, e12198. https://doi.org/10.1049/mna2.12198 (2024).

Eltarahony, M. et al. Antibacterial, antifungal and antibiofilm activities of silver nanoparticles from lake-derived biofactories. Molecules 26, 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26103027 (2021).

Dhungana, S., Paudel, B. R. & Gautam, S. K. Synthesis and characterization of ZnTe nanoparticles. Nepal J. Sci. Technol. 17, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3126/njst.v17i1.25054 (2016).

Regmi, A. et al. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of cuprous oxide nanoparticles. J. Nepal Chem. Soc. 40, 5–10. https://doi.org/10.3126/jncs.v40i0.27271 (2019).

Gautam, S. K. et al. Estimation of particle size and band gap of zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Nepal Chem. Soc. 41, 46–50. https://doi.org/10.3126/jncs.v41i1.30448 (2020).

Mehta, B. K., Chhajlani, M. & Shrivastava, B. D. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles characterized by XRD. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 836, 012050. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/836/1/012050 (2017).

Singh, C. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Premna integrifolia. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 33, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/13102818.2019.1577699 (2019).

Ajitha, B., Reddy, Y. A. K. & Reddy, P. S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Lantana camara. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 49, 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2015.01.035 (2015).

Kumar, V. et al. Photo-induced biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and catalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 155, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.12.011 (2016).

Mostafa, Y. S. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from fruit peels and antifungal activity. Plants 10, 2363. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10112363 (2021).

He, K. et al. Method for determining crystal grain size by X-ray diffraction. Cryst. Res. Technol. 53, 1700157. https://doi.org/10.1002/crat.201700157 (2018).

Adebayo-Tayo, B., Salaam, A. & Ajibade, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Oscillatoria sp. Heliyon 5, e02502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02502 (2019).

Sharma, D. et al. Biosynthesis of hematite nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 206, 111841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111841 (2020).

Philip, D. Honey-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 75, 1078–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2009.12.058 (2010).

Song, J. Y. & Kim, B. S. Biological synthesis of Au/Ag nanoparticles using persimmon leaf extract. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 25, 808–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-008-0133-z (2008).

Kumar, R. & Shikha, D. Thrombogenicity and cytotoxicity of silver-doped hydroxyapatite. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 22, e14884. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijac.14884 (2025).

Kumar, R. et al. Silver-doped hydroxyapatite coatings with enhanced properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 11, 2622–2638. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.4c02471 (2025).

Srinithya, B. et al. Biofunctionalized silver nanoparticles using Sida cordifolia. Mater. Lett. 170, 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2016.02.019 (2016).

Lü, J. et al. Chemical and molecular mechanisms of antioxidants. J. Cell Mol. Med. 14, 840–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00897.x (2010).

Bakht Dalir, S. J. et al. Characterization and antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Heliyon 6, e03624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03624 (2020).

Gautam, S. K. et al. Antimicrobial study of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 128–132. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijasbt.v9i2.37822 (2021).

Gudikandula, K. & Charya Maringanti, S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles and antimicrobial properties. J. Exp. Nanosci. 11, 714–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/17458080.2016.1139196 (2016).

Elshikh, M. et al. Resazurin-based microdilution method for MIC determination. Biotech. Lett. 38, 1015–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-016-2079-2 (2016).

Zahra, S. A. et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Lactuca orientalis. Microsc. Res. Tech. 84, 1284–1295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jemt.23687 (2021).

Hublikar, L. V. et al. Anticancer potential of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles. Prog. Biomater. 12, 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40204-023-00219-9 (2023).

Bhusari, S. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles via Taxus wallichiana and their biomedical potential. Green Process. Synth. 12, 20230051. https://doi.org/10.1515/gps-2023-0051 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Department of Science, Kailali Multiple Campus, Far Western University, for providing laboratory facilities. For XRD data acquisition, we sincerely thank the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), Lalitpur, Nepal. We also express our heartfelt appreciation to Jeonbuk National University, Republic of Korea, for providing FESEM and EDX imaging support. Authors are greatly indebted to the Central Department of Chemistry, Tribhuvan University, for UV–vis, FTIR, antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer tests.

Funding

The study was conducted without financial support from external funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Indra Ojha: Methodological work, formal analysis, drafted manuscript, revised and edited. Prem Singh Saud: Data curation, modification, review supervision, and conceptualization. Dipak Raj Jaishi: Editing and revision, Yagya Raj Rosyara: Writing and editorial refinement, Anil Ojha: Writing and editorial refinement, Nepal Rama Devi: Composing and formal evaluation, Prem Raj Joshi: Manuscript drafting and critical evaluation, Hem Raj Pant: Writing, reviewing, editing, supervision, and conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted following the institutional guidelines of Far-Western University. Alcea rosea is not listed as an endangered species, nor is it included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The Plant Protection Act and the International Plant Protection Convention were followed, and no endangered plant species were harmed or disturbed during this study. As the study was carried out in Sudurpaschim, it met with all relevant local and federal regulations. Commercially obtained, verified A549 and HeLa cell lines were used for the in vitro anticancer investigations. Every experiment was carried out in accordance with accepted biosafety practices and with institutional approval.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ojha, I., Saud, P.S., Jaishi, D.R. et al. Plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Alcea rosea leaf aqueous extract and evaluation of the biological activities. Sci Rep 16, 6693 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37480-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37480-4