Abstract

Studies on the symbol and feedback effects on the opinion based on the theory are lacking. Acknowledging that the media express their stance and opinion and that negative opinions are critical to policy change, this paper fills the gap in the literature by illustrating and comparing the effects of emotional and cognitive symbols and positive and negative feedback on the liberal and conservative newspapers’ negative opinions of South Korean President Park Geun-hye’s administration (Park administration) after the Sewol Ferry sank. This study used qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze the archival data, including 424 newspaper editorials and economic data published from April to December 2014. Multiple regression analyses were conducted following a content analysis of newspaper editorials, and network analysis was used to analyze the data. The results mostly supported the hypotheses that symbols and feedback affect the negative opinion on the political discourse, with new findings that deviate from the existing theories. The emotional symbols exerted a stronger influence on the negative opinion compared to cognitive symbols, regardless of the newspaper’s stance. The political system’s response to the positive and negative feedback was not definite; instead, it varied depending on the situation and newspaper perspective. The liberal newspaper responded to symbols and feedback more sensitively compared to the conservative one under the conservative administration. The conservative newspaper expressed more lenient negative opinions towards the conservative administration than the liberal newspaper, supporting the home team effect. These findings have practical and theoretical implications for future studies, highlighting the application of opinion networks in social science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some disasters, like Hurricane Sandy in the northeastern United States, can be politicalized in what is called “disaster politicizations” (Chung 2013). Since opinion is critical to policy, when politicians or bureaucrats face negative opinions from the media, they are more likely to try to affect policy change to avoid repercussions of negative publicity by interacting with people through media rather than face-to-face (Berelson et al. 1954).

Although a disaster usually does not become a nationwide major political issue on whether and how the government helps the weak and helpless victims, the Sewol Ferry Disaster became a political issue because of the numerous student victims and the upcoming election. Furthermore, a disaster usually does not become politicized due to victims’ weakness and helplessness (Schneider 1995); therefore, the Sewol Ferry Disaster is unique in this sense, and unlike other disasters, it has been a frequently discussed politicized disaster for many years. It also took longer to reduce people’s attention to the issue of the Sewol Ferry (Cho and Jung 2019). Therefore, it is still crucial to study the Sewol Ferry Disaster.

News articles tend to contain political bias that shapes opinion. The media’s negative opinion influences voters’ views and policy change. Thus, political media affect how politicians and policy entrepreneurs generate symbols while the political system responds to big events with feedback. Through disaster politicization, the Sewol Ferry Disaster changed the culture of disaster management and boosted its importance (Chae 2017; Cho 2017; Cho and Park 2023; Chung 2020). Following the Sewol Ferry Disaster, the culture and perspective on safety and disaster management changed and developed comprehensively. Thus, the Sewol Ferry Disaster informs further investigations on how media respond to disaster politicizations according to the symbol, feedback, and media’s political stance. This study employed an innovative method of an opinion network to describe opinion. Furthermore, through unique data analysis of the opinion network, this study evaluated the symbol and feedback effects on the policy stakeholders’ negative opinions of the Sewol Ferry Disaster, considering the newspapers’ ideologies.

Background: Sewol Ferry Disaster

South Korea has had a centralized bureaucracy for a long time, recognizing the citizens’ and media’s rights to expression (Cho and Jung 2019). Many issues from policies and disasters have emerged and stabilized over time as a result of media reports. Liberal newspapers tend to support liberal administrations, while conservative newspapers tend to support conservative administrations. In response to citizens asking the central government to address problems or causes of disasters and issues, the Korean administration, governments, and policy actors enacted policies by creating or reorganizing agencies, increasing budgets, drafting acts, and scapegoating individuals or organizations in charge when they encounter new problems (Cho 2017).

The Sewol Ferry Disaster occurred during the conservative administration on April 16, 2014. Due to the South Korean government’s ill-performed rescue efforts, the disaster claimed the lives of 295 people, including 246 high school students (Hwang 2015). When the Sewol Ferry Disaster occurred, victims’ innocence and helplessness induced empathy in people who wanted to help them. Facing a local election on June 4, politicians and the populace turned this disaster into a hot political issue. Opposing parties tried to use this tragedy to criticize the conservative Park administration, while the Park administration (president, ruling party, and the Blue HouseFootnote 1) tried to deny its responsibility. Many Korean media responded by focusing on the victims and their families. The liberal and conservative populace and media expressed different opinions offline and online.

Few empirical studies have investigated the symbol and feedback from different perspectives. Because of the lack of studies on disaster politicization, different perspectives of newspapers, the symbol of multiple streams approach (MSA), feedback in punctuated equilibrium theory (PET), and bias using the home team effect (HTE), this study aimed to investigate qualitatively and quantitatively how the symbol and feedback influenced negative opinion and how newspapers with different ideologies responded to the symbol and feedback based on negative opinion during the Sewol Ferry Disaster.

This paper provides an overview of the theoretical perspectives, followed by a case study of the events of the Sewol Ferry Disaster and the regression analysis evaluating the influence of symbols and feedback on newspapers’ negative opinions. The study compares liberal and conservative newspapers’ negative opinions of President Park’s administration to illustrate the HTE.

Theoretical background

Policy entrepreneurs utilize symbols to diminish the ambiguity of disaster politics, and the political system responds to them with feedback while the media describes them based on their political stances. The three theories reviewed in the following sections address all of these issues. When the disaster occurred, people were interested in why it happened and how the media and newspapers described the situation. Thus, MSA, PET, and HTE theories were appropriate for addressing the disaster and media response. MSA and PET are commonly used when accidents or events lead to sudden changes in policy outcomes (Cho 2017). MSA describes how the policy entrepreneurs utilize symbols to gain media attention, while the PET shows how the feedback influences the media’s attention and origination’s budget response. When explaining politically controversial issues, HTE is a proper way to understand the media’s perspective on controversial political issues.

Symbol and feedback in the policy process

Emotional and cognitive symbols for converging three streams in Multiple Streams Approach (MSA)

Symbols play an important role in the policy process, as they portray a simple message or idea and offer an argument to boost opinion cognitively and emotionally. During the policy process, politicians need to employ symbols to identify their legitimacy and integrity (Edelman 1964: 190). Kingdon (1984)Footnote 2 argued that new policies do not emerge merely because the time is right; rather, the three streams (problems, politics, and policy streams) usually align within a window of opportunity (Ruvalcaba-Gomez et al. 2023). Problems linger and receive attention depending on how participants frame or define them. Crises and disasters often elevate the standing of particular problems, competing for the attention of policymakers and citizens. A policy stream exists and rises to the fore when the policy window opens, and it is presented as a resolution to an identified problem based on their pet solutionFootnote 3. Various actors shape and modify proposed policies, waiting for the right time to emerge as their pet solution to a problem. The politics streamFootnote 4 is activated when policymakers are motivated and able to advance a particular policy. Using symbols, policy entrepreneurs boost the public opinion of controversial proposals to coupleFootnote 5 the streams and change policy when a policy window opens. The policy windowFootnote 6 is opened when problems, policy, and politics streams align (Burgess 2006; Rinfret 2011) in response to the occurrence of a focusing event (Simon 2010). Following MSA, the Sewol Ferry Disaster presents a unique opportunity to examine how symbols can couple the streams and change policy.

SymbolFootnote 7. Symbols occur in uncertain situations without certain meaning, while signs have a direct meaning (Veraksa 2013). When a policy window opens or needs to open, symbols are used to attract attention in MSA (Eckersley and Lakoma 2022; Ruvalcaba-Gomez et al. 2023; Zahariadis 2007). Carroll (1985) mentioned that policy entrepreneurs and policymakers utilize symbols with specific emotional repercussions and cognitive referents (Zahariadis 2007). The opponents of certain issues create new symbols that prevent an unfavorable issue from emerging (Bachrach and Baratz 1963; Bennett 1988; Schattschneider 1960). Thus, using familiar and positive or, alternatively, hostile or skeptical symbols facilitates mass reaction (Cobb et al. 1976). Although political symbols are neither immediate nor unanimous, they bring about change (Edelman 1964).

Symbols are messages embedded in the news. They are employed to expand individuals’ understanding of an issue (Birkland 1997). Employing the symbols helps entrepreneurs couple three streams by reaching more people, evoking compelling emotions, and explaining their proposal efficiently (Zahariadis 2007). During ambiguity, political manipulation facilitates symbolic politics while commonality is condensed in the symbols (Zahariadis 2007). The media use a symbol at a particular time depending on the “dominant culture” (Riffe et al. 2005: 11). Using symbols helps entrepreneurs combine the three streams by reaching more people, evoking compelling emotions, and explaining their proposal efficiently (Zahariadis 2007). These symbols are also broadcasted via media to boost emotion. Ultimately, this emotional arousal brings about confrontational policy adoption (Zahariadis 2005). The examples above show how symbols boost the opinion via media and how policy entrepreneurs facilitate the development of their policy solutions.

The symbol affects people’s emotions and cognitions. Many researchers have suggested that a symbol has different functions (Veraksa 2013). Scholars have commonly employed emotional and cognitive functions (Elder and Cobb 1983; Veraksa 2013; Zahariadis 2007; Zahariadis 2014). Emotional symbols influence people’s positive and negative states and feelings (e.g., fear, love, joy, hate, and sorrow)Footnote 8 rather than appealing to their reason. Emotionally, symbols are sometimes used to define an issue (Cobb et al. 1976). The emotional function of a symbol delivers tension in uncertainty (Veraksa 2013). The cognitive symbol also provides information. The symbol functions cognitively by facilitating an individual’s interpretation capacity (Veraksa, 2013). Cognitive symbols influence people’s perception of mental reasoningFootnote 9 via simple information.

Positive and negative feedback of the political system in the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (PET)

Public policy feedback affects future policymaking through enhanced incentives and the value of political actors (Béland 2010; Larsen 2019). Positive feedback boosts the policy change, while negative feedback reduces the change (Cho and Jung 2019). This study also used positive and negative feedback from the PET to examine policy developments in the aftermath of the Sewol Ferry Disaster. PET is appropriate for understanding radical changes in individual policy systems after stable periods (Baumgartner and Jones 1991).

Beginning from evolutionary biology (Gould and Eldredge 1993; Jones and Baumgartner 2012),Footnote 10 one of the main concepts of PET is a sudden change in a stable equilibrium in policy, referred to as a policy monopolyFootnote 11. Only a few people, such as bureaucrats, politicians, and interest groups, can access the policy process. “Politics of the policy monopoly, incrementalism, a widely accepted supportive imageFootnote 12, and negative feedback” (Baumgartner et al. 2014: 67) maintain politics of equilibrium in subsystems. The policy monopoly suppresses change with negative feedback, although this does not always work (Baumgartner et al. 2014).

The political shock or policy entrepreneur usually provides positive feedback at the domestic level (Joly and Richter, 2023). “Positive feedback occurs when a change … causes future changes to be amplified” (Baumgartner et al. 2014: 64). In the meantime, political movements, government agenda improvement, and positive feedback cause the politics of punctuation (Baumgartner et al. 2014). Meanwhile, the proponents and opponents focus on different sets of images (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). When opponents compare new images with previous images, the policy monopoly will collapse (Baumgartner et al. 2014). In other words, even though a single image is broadly accepted and supported under the policy monopoly, if opponents raise a new image, the policy monopoly starts to collapse (Baumgartner and Jones, 1991, 1993). A political agenda supports the shift in public policies to a new equilibrium through positive feedback, while negative feedback dampens the changes (True et al. 2007). This amplification process overcomes the cognition and institutional frictionFootnote 13 embedded within the government (Jones et al. 2003; John and Jennings 2010), resulting in a large change to correct the deficiency of prior policy modification (Joly and Richter 2023).

When a policy monopoly collapses after an abrupt shock event, new policy actors dispute the rule to rearrange the balance of power (Baumgartner et al. 2014). After the shock event, the positive feedback that facilitates policy change drives the resulting policy change, reaching a new equilibrium along with negative feedback. However, people have difficulties discerning positive and negative feedback (Cho and Jung 2019).

Feedback. In PET, scholars assume that the “political system” (Cairney and Heikkila 2014: 367) reacts to feedback and returns to stability even after the drastic change. Feedback occurs continuously during the policy process and provides information to improve performance (Chung et al. 2019). Feedback is a critical learning activity in the policy system (Chung et al. 2019). Characteristics of the political or policy system are the main factors affecting policy change (Chung et al. 2019). Thus, policy change occurs in response to how the political system addresses the support and opposition of policy (Chung et al. 2019).

Positive and negative feedback affect change. When feedback occurs, determining whether it is positive or negative is critical (Larsen 2019). Political systems maintain their stability after major periodic changes using positive and negative feedback (Baumgartner and Jones 1991; Cairney and Heikkila 2014). Policy feedback effects represent the direction of mobilization (Larsen 2019). A large scale of change comes from positive feedback (Baumgartner et al. 2014) with dramatic disruption by creating new images and mobilizing other participants (van den Dool and Li 2023). In PET, positive feedback refers to influences or processes that tend to create change or speed it up. Footnote 14 Thus, when change emerges, positive feedback affects future change (Baumgartner et al. 2014). During the positive process, an expanding political issue encourages policy to reach a new equilibrium (True et al. 2007).

Negative feedback, on the other hand, refers to influences that reinforce the status quo and resist change or slow it down. Usually, under the monopoly policy, the policy is stable due to negative feedback. Negative feedback tends to diminish policy changes (True et al. 2007), supporting the system’s stability (Baumgartner et al. 2014) due to unnoticed new issues or inefficient processes (van den Dool and Li 2023). When opponents raise problems with a negative opinion, the policy monopoly collapses. However, the positive and negative feedback do not undoubtedly work against each other, leading to difficulties in determining whether the feedback effect increases or decreases the change over time (Larsen 2019).

Scholars have demonstrated different punctuations, which is the main concept in PET (Cho and Jung 2019). Mostly two dimensions, the X-axis representing time and the Y-axis representing punctuation, describe the change in policy punctuation (Baumgartner et al. 2009; John and Jennings 2010; John 2006). In academia, policy punctuations are commonly represented in two ways (Cho and Jung 2019), the budgets (Jones and Baumgartner 2005; Jones et al. 1998; Jones et al. 2003; Jones et al. 2009; Robinson et al. 2014; True 2000) and attention to word frequency (Fowler et al. 2017), speech (Baumgartner et al. 2009; John and Jennings 2010), media coverage (John 2006), court decisions (Robinson 2013; Wood 2006), bills and laws (Baumgartner et al. 2009), coverage of lawmaking and executive orders (Jones et al. 2003), and Google Trends (Cho and Jung 2019). In addition to these, this study introduces a negative opinion as another way to visualize the attention after the Sewol Ferry Disaster.

Influence of liberal vs. conservative newspapers’ opinions on the Home Team Effect (HTE)

Opinion, particularly a negative one, significantly influences politicians. Support and demand influence the political system and policy (Easton 1966). Generally, media outlets respond to the policy by reporting and analyzing issues of public concern (Barnes et al. 2008). Thus, their response influences policies (Harris et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2002; McCombs 2004; McCombs and Shaw 1972; Scheufele and Tewksbury 2007). Following a tragedy or a disaster, they care more about negative than positive opinions. Responses of the media to these tragedies or disasters depend on their political stand and ideology. Among the various media, the newspaper is a “workhorse” in the public information system, acting as a moving force because most information comes from the newspapers (Cutlip et al. 2006: 255). Newspapers fulfill their audiences’ needs, satisfying their motivation (Ryu 2018). Newspaper is commonly utilized to compare liberal and conservative newspapers’ political orientations (Valente et al. 2023).

Furthermore, newspapers tend to adopt a partisanship perspective on the controversial issue (Fico and Soffin 1995; Ryu 2018). Some newspapers’ political and ideological perspectives are salient through their liberal and conservative audience (Baek 1997; Kim and Choi 2016; Kwon 2016), especially in Korean editorials. Despite pursuing objectiveness and striving to present balanced perspectives, newspapers are biased (Kim 2018) based on their political stance. Although most media claim they are fair referees (Kang 1999), the incumbent administration and government could influence the media’s perception and opinions. When the newspaper expresses its opinion on politically controversial issues after the disaster, the newspaper could facilitate the policy change and respond differently. This means that the newspaper expresses its opinion following its audience’s stance because the audience would like to hear the news consistent with its preferences and perspectives. Therefore, this study employed the HTE.

HTE is a useful tool for scholars to predict or explain people’s behavior (Uribe et al. 2021; Van Reeth 2019). People generally support their preferred team (Erhardt 2023). The HTE, which states that individuals who support the incumbent government tend to perceive it as less corrupt than that supported by the opposition (Anderson and Tverdova 2003; Blais et al. 2017), could explain this phenomenon.Footnote 15 The “motivated political reasoning” explicates that “directional goals lead people to access and accept information which justifies their conclusion” (Blais et al. 2010: 2). This biases individuals’ perceptions and opinions (Kunda 1990, 1999; Taber et al. 2001). The newspaper is a for-profit firm motivated to provide slanted stories based on readers’ preferences (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2010). Partisan predisposition influences subjective political judgment (Blais et al. 2010). Much research has studied partisanship’s influence on political reasoning (Anduiza et al. 2013; Blais et al. 2010).

Media and opinion in the policy process

The news media play a crucial role in producing the language used to critique political bodies. Since people tend to pay attention selectively (Iyengar and Kinder 1987), mass media boost political agendas (Thesen 2013) by selecting and emphasizing certain issues (Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999; Thesen 2013). This means that audiences evaluate the leaders’ performance using specific information from the media (Scheufele and Tewksbury 2007). Media influence public knowledge of disaster recovery and public perceptions of disaster recovery successes and failures instead of reporting the situation objectively (Harris et al. 2001; Schneider 1995).

Opinion

Opinions are useful for analyzing the underlying structure of social networks, which initiate opinion networks (Zhou et al. 2009). The opinion, or the expression of “an individual’s attitudes, beliefs, or values” (Beebe and Beebe 2006: 179), can induce and foretell a policy change. Liu (2011) defined an opinion, in reference to the opinion miningFootnote 16 practices, as “a positive or negative sentiment, view, attitude, emotion, or appraisal about an entity or an aspect of the entity from an opinion holder” (Liu 2011: 15) (see Appendix 2 for more detail). Politicians and administrations create policies that reflect the media’s and citizens’ opinions. The media’s agenda influences the voter’s agenda (Cutlip et al. 2006). Increased media coverage of an issue influences public priorities (Cutlip et al. 2006). The surge of media attention, interests, concerns, and stronger opinion enhances the policy’s importance and increases the likelihood of policy change (Baumgartner and Jones 1993; Cutlip et al. 2006; McCombs and Shaw 1972; Wanta et al. 2004).Footnote 17

Furthermore, opposing parties often emphasize bad news to impose responsibilities on the government based on faults (Thesen 2013). Meanwhile, the media express their positive and negative opinions by describing positive and negative situations. Media use surveys to evaluate public opinion and determine the percentage of individuals who support and oppose an issue or candidate (Cutlip et al. 2006). The administrations and politicians are concerned about negative opinions (Thesen 2013) because negative opinions are critical to their election and influence the perception of their performance. The government bears greater responsibility due to the pressure to react to the news (Thesen 2013). For this reason, negative opinion is a critical part of the political message of media. Thus, the opinion could be an alternative way to show the punctuation of attention.

A negative opinion, which is also one of the main points for the newspaper to report, is necessary for politicians’ and bureaucrats’ reelections. Groups outside the government express their grievance to advance their interests (Cobb et al. 1976). Even after turning the public agenda into a formal one, grievance (Cobb et al. 1976) or negative opinion remains important because the advocacy group still emphasizes negative opinion during policy formulation, decision-making, and agenda setting (Simon 2010). Furthermore, the elected officials and politicians reflect on their constituents’ opinions and grievances to ensure their reelection (Weaver 1986). On the other hand, the media express their positive and negative opinions and describe positive and negative situations consciously and subconsciously. This could mean that newspapers tend to express negative opinions by describing the negative situation and stories. Studying the influence of positive and negative coverage in foreign nations, Wanta et al. (2004) showed that negative coverage influences the audience’s perception. This explains why the political system and administration try to reduce negative coverage, as a more negative opinion of the president’s administration is more likely to lead to policy change. Thus, I can extend this logic to assume that more negative opinions of an administration influence the citizens’ perceptions, thereby affecting the presidential and legislative parties’ support and elections.

Gaps identified from the theoretical background

Although MSA considers the symbol in the policy process, studies on the symbols are limited. Furthermore, it is difficult to understand how different symbols affect newspapers’ opinions. Although various studies have utilized PET, they have not fully applied PET terminology (Cho and Jung 2019). Most PET studies have focused on punctuation rather than on positive and negative feedback (Cho and Jung 2019) as the key concept (Baumgartner et al. 2014). Moreover, previous PET studies did not clearly show whether positive and negative feedback change attention or negative opinion. The discrepancy between the theoretical and empirical effects of positive and negative feedback (Larsen 2019) requires further empirical testing. In terms of the HTE, the newspaper has a different political ideology. Media can be biased (Kim 2018) and respond to government policy by explaining a situation from their perspective and delivering either a positive or negative opinion to the public. The newspaper has a very different political ideology. Newspapers respond to government policy by explaining a situation from their perspective and delivering either a positive or negative opinion to the public. The policies influence the media’s opinion. Thus, the media’s political preference also influences their perspectives through their political judgment and opinions.

Accordingly, policymakers and entrepreneurs employ symbols, and the political system responds to feedback to influence the media’s negative opinion after a disaster. Opinion is critical for policymakers, politicians, and even laypersons to understand their society’s policy change and further development. Additionally, under a conservative administration, liberal and conservative newspapers respond to these settings and environments after a disaster by expressing their positive and negative opinions. However, descriptive studies on symbols and feedback across different political ideologies are lacking. Thus, the mixed method is necessary to bolster the more descriptive and reliable studies of symbols and feedback. In sum, this study conducted a case study and regression analysis of an opinion network to assess the media’s negative opinion change following the emotional and cognitive symbols and positive and negative feedback depending on the media’s political viewpoint (see Fig. 1).

As shown in Fig. 1, three hypotheses and theoretical propositionsFootnote 18 address this study’s research question. These propositions and hypotheses portray emotional and cognitive symbols from MSA, positive and negative feedback in PET, and different political ideologies from HTE qualitatively and quantitatively. Thus, after conducting the case study based on the three propositions, I ran a regression analysis on the negative opinion to test the three hypotheses to reveal the effect of symbol and feedback and the different responses depending on the different newspapers’ political perspectives.

Method and data

To increase the integrity of the study, I used the triangulation technique, utilizing various theories, data sources (Creswell 2013), and analyses due to the uniqueness of the opinion network. I conducted the analysis based on theoretical propositions and modified a theory from case study findings (Cavaye 1996). I utilized a qualitative case study based on theoretical propositions (Cavaye 1996; Cho and Jung 2019; Deslatte et al. 2023). Furthermore, I performed the content analysis of the newspaper editorials. I described how liberal and conservative newspapers employed symbols to criticize the Park administration and how liberal and conservative newspapers responded to each feedback with negative opinions. However, the case study is inferior to quantitative descriptions of symbols and feedback in newspapers with different political ideologies. To overcome this limitation, I compared the negative opinions of liberal and conservative newspapers using regression analysis and opinion network centrality.

Method and research design: opinion network

Opinion network combines network analysis and opinion mining to depict the relationship between an opinion of each actor. Social network analysisFootnote 19 can be applied to data obtained from opinion mining by measuring the relationship between actors (Wasserman and Faust 1994) using content analysis.Footnote 20 Merged network analysis, opinion mining, and content analysis form an opinion network to describe and visualize the positive and negative opinions to change and push a policy because it represents intensity and direction. Opinion networks usually describe diverse networks (e.g., Blex and Yasseri 2022; Ibitoye and Onifade 2022) of public opinions in data analysis (e.g., Wang et al. 2019). Despite the seminal study on opinion networks (Bamakan et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2009), the opinion network had been understudied and underutilized in social science compared to other network studies.

Opinion mining studies positive or negative opinions (sentiments) (Liu 2012)Footnote 21 within the message. Essentially, opinion mining focuses on the relationships between the agencies of organizations and individuals (Liu 2012). It evaluates the “emotion associated with attitude objects,” such as products, people, or issues (Krippendorff 2013: 245). Analyses of this type have been conducted in international affairs and text mining with computer programming. Opinion mining has often been a part of commercial analysis (Adedoyin-Olowe et al. 2014), for instance, to gather the opinions of consumers regarding an item or service on a given website. People or even objects are interrelated and form opinions about each other. Direction and intensity are the most common ways to evaluate people’s feelings and their depth (Cutlip et al. 2006). The direction of the opinion is an “evaluative quality of predisposition,” positive or negative, depending on the evaluation of the public (Cutlip et al. 2006: 206). Intensity refers to the strength of people’s opinion directions (Cutlip et al. 2006). However, opinion mining and network analyses do not simultaneously show the opinion, relationship, and direction between nodes.

Opinion networks demonstrate the positive and negative relationship and directionFootnote 22 between nodes by adding weights to the text data. Opinion networks can depict common relationships in the text after the content analysis, overcoming time limitation issues associated with the process of interviewing people to collect data. This analysis also allows visualizing the positive and negative opinions of nodes with direction. In the opinion network, nodes are the subjects or objects of opinion in sentences. Ultimately, the opinion network helps people see the relationships and their directions, unlike other network analyses (e.g., semantic networkFootnote 23). Thus, an opinion network can show the positive and negative opinions between people or objects. Links (edges or ties) represent positive or negative opinions with direction and weight between nodes (see Appendix 1 for more detail).

Data

I collected archival data from web searches, government records, and websites. The geographical and national scope of the study was South Korea, and the time scope of the analysis covered the period from April 2014 to December 2014. Subsequently, I analyzed the data based on a chain of evidence,Footnote 24 theoretical propositions (Cho and Jung 2019; Deslatte et al. 2023; Jung et al. 2023), and the systematic protocol to ensure the reliability of the case study (Yin 2014). Then, I conducted the regression analysis with opinion network data derived from the content analysis of the Hankyoreh (liberal) and Chosun (conservative)Footnote 25 newspaper editorials to evaluate different perspectives in the newspapers.Footnote 26 The South Korean editorials closely reflect the perspectives and opinions of their newspapers.Footnote 27 These newspapers usually publish three editorials daily on popular and critical topics that occurred the previous day. Thus, editorials provide condensed information on selected topics.

I employed a network data collection method using the word search “Sewol Ferry” to collect 192 online editorials from Chosun and 232 from Hankyoreh newspapers published from April 16, 2014, to December 31, 2014. Specifically, I applied hand-coded opinion mining and content analysis via an edge list (see Appendix 1).Footnote 28 The data were collected over 38 weeks, and each node and link were extracted from each sentence. The intercoder reliability of content analysis reached 82.99%.Footnote 29

Case study

Propositions

The three theoretical propositions are presented below. Proposition 1 concerning symbols from MSA considered problems, politics, and policy streams that existed before the Sewol Ferry Disaster. After the Sewol Ferry Disaster, many people blamed the Park administration, and policy entrepreneurs converged three streams to push their pet solutions using the symbol after the Sewol Ferry Disaster. The feedback in the PET of proposition 2 represents policy monopoly before the Sewol Ferry Disaster, reflecting the blameless image of the Park administration. However, after the Sewol Ferry Disaster, the political system produced positive and negative feedback across multiple venues and shifted the Sewol Ferry Disaster to macro-level politics with positive feedback and an increasingly negative opinion. After negative feedback, the punctuated attention stabilized. Meanwhile, consistent with proposition 3, responses to the symbol and feedback differed depending on the newspapers’ perspectives emerging from the HTE. Specifically, the conservative newspaper appeared more lenient than the liberal newspaper under the conservative administration.

Case study

Pre-disaster

Before the Sewol Ferry Disaster, problems could be detected due to governments’ weak supervision and loosely implemented marine safety laws (such as loose supervision of people on overcrowded vessels, poorly equipped safety facilities, renovation of ship structures, and skipped ship inspection) (Cho 2017). Regarding policy stream, the South Korean government and politicians dealt with problems by increasing budgets, creating special acts or organizations (such as task-related ministries and commissions), or redirecting the blame to or away from a person in charge (Cho and Jung 2019). Korean policy entrepreneurs can perceive these as popular pet solutions (Cho and Jung 2019). Concerning the politics stream, the ruling and opposing parties and their respective associates disagreed with each other even before the Sewol Ferry Disaster. Immediately following the presidential election, scandals surfaced, showing that the National Intelligence Service manipulated people’s opinions via social media to support the ruling party at that time (similar to President Park’s administration), as revealed through individuals’ pro-government replies to these published opinions.Footnote 30 When the ferry sank, questions about the legitimacy of President Park emerged. Civil societies questioned the legitimacy of President Park’s administration. Anti-government citizens distrusted the Park administration and the result of the election.

Under a policy monopoly, marine bureaucrats, politicians, and interest groups could access the marine policy process, while people did not show much interest in the marine industry or its safety protocols. People easily forget the lessons learned from previous disasters and accidents in Korea. At the beginning of President Park’s administration, the government restructured itself, creating an image of the Ministry of Security and Public Administration (MOSPA) by merging several organizations and emphasizing the term “security” in front of the public administration to highlight its commitment to safety (Chae 2014; Cho 2017; Cho and Jung 2019). Only a few politicians, bureaucrats, and interest groups decided on most issues and policies. While the liberal and conservative populaces actively responded to the Sewol Ferry Disaster, liberal and conservative media described the tragedy. These stable but incremental changes shifted to non-incremental changes in South Korea.

Post-disaster

The Sewol Ferry Disaster spurred the entire country to advocate for policy change. The media started to point out the problems and causes of the Sewol Ferry Disaster, focusing on the victims’ families, high school victims, and survivors while blaming the President, the Blue House, the ruling party, the government, bureaucrats, Korean Coast Guard (KCG), and persons related to the accident with diverse opinions (Cho 2017). Civil society organizations and politicians spread criticisms and negative opinions of President Park’s administration for the lax supervision and loosely implemented marine law that they believed led to the failed rescue efforts by consoling victims (symbols) and acting as policy entrepreneurs. In the meantime, they tried to resolve problems with their pet solutions. In the end, the national mood was so despondent that public employees and some citizens curtailed, postponed, and even canceled their leisure and recreational activities and ceremonies to grieve for deceased students, other passengers, and their relatives and families (Cho and Jung 2019).

Increasing negative opinion with symbol from MSA

The death of young people aboard the ship and the families they left behind became symbols that evoked purity, innocence, and helplessness, which enhanced the public’s emotions and facilitated policy changes with positive opinions. Symbols related to the victims of the Sewol Ferry Disaster and their families boosted the citizens’ and liberals’ negative opinions of the Park administration and facilitated the coupling of the three streams: problems, policies, and politics. Most victims were poor high school students from Ansan, an impoverished region (Cho and Jung 2019). The liberal and conservative media and the opposing parties influenced policy change by broadcasting many touching stories about the victims, their families, those who survived the disaster, and missing bodies found following the Sewol Ferry Disaster (symbol). Newspapers depicted positive opinions of victims, including condolences, pities, sympathies, comforts, and commiserations, as emotional symbols because they briefly expressed the dominant culture in South Korea after the Sewol Ferry Disaster. Intermittent media accounts spotlighting the number of bodies found (cognitive symbols) kept the fading memory of the sunken ship alive. These symbols from policy entrepreneurs and media increased the negative opinion, facilitating the policy change by attacking the Park administration (see Tables 1 and 2).

Punctuation after increasing negative opinion following the feedback in PET

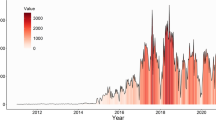

In the meantime, the media and opponents presented the sunken Sewol Ferry problems and ill-performed government actions, unlike the previous MOSPA safety image or impression. This led to the collapse of the policy monopoly. The Sewol Ferry Disaster caught the attention of many groups and citizens and shifted the issue from subsystem politics to the macro-political stage. Figures 2 to 4 show how budget and attention (newspaper editorials and Google Trends) drastically changed in response to the Sewol Ferry Disaster to emphasize punctuation.

Increasing Budgets of Public Order and Safety (Cho and Jung, 2019).

Concerning budget and attention, as the two ways to visualize the punctuation, Fig. 2 shows a larger budget change for Public Order and Safety. When focusing on safety without a public order budget, the safety-relevant budget increased by 17.9% (Heo 2014). This illustrates a vast punctuation in the safety-relevant budget. Footnote 31 The 17.9% increase Footnote 32 was higher compared to Wildavsky’s (1984) 10% and Kemp’s (1982) ± 10% criterion, the threshold criterion for punctuation. However, this budget change does not sufficiently capture a change in people’s attention.

On the other hand, this study revealed a change in attention as another way to view punctuation. Figures 3 and 4 show that the attention of liberal and conservative newspapers and people’s Google search to the Sewol Ferry Disaster changed abruptly in response to the Sewol Ferry sinking (Cho and Jung 2019). This proves the punctuation of the media’s attention.

The Number of Liberal (Hankyoreh) vs. Conservative (Chosun) Newspaper Editorials After Sewol Ferry Disaster (Cho and Jung 2019).

Google Trends for “Sewol Ferry” Searches in South Korea. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?geo=KR&q=sewol%20ferry.

These drastic increases in budget and attention (Figs. 2–4) contributed to the collapse of policy monopoly among bureaucrats, politicians, and interest groups within the marine industry and increased the interest of other groups and citizens in the policy after the Sewol Ferry Disaster.

Pet solutions and feedback

Pet solutions: Politicians also employed their traditional pet solutions that led to the resignation of Prime Minister Chung Hong-won, the pursuit of Mr. Yoo, the reorganization of the government structure, the dismantlement of the KCG as a scapegoat, the drafting of the new legislation, the creation of the commission for investigation, and increased budgets to prevent similar accidents from occurring (Cho and Jung 2019). These represent pet solutions (committees, reorganization, scapegoat, drafting acts) to condole victims and stabilize negative opinions and change. After the June 4 local elections, three Sewol ActsFootnote 33 were passed after the long and tedious debate and compromise between the ruling and opposing parties to prevent future disasters. Subsequently, efforts to retrieve missing bodies ended, and the Ministry of Public Safety and Security (MPSS) was established (negative feedback).

Feedback: From a different viewpoint of PET, the political system provided both positive and negative feedback that reinforces and undermines changes in policies (Cho and Jung 2019; Larsen 2019) regarding the Sewol Ferry sinking. Originally intended to reduce change, the two failed negative feedback responses turned into positive (Cho and Jung 2019). One was the resignation of Prime Minister Chung. President Park’s administration tried to avoid the criticisms after Prime Minister Chung resigned (negative feedback), accepting responsibility for the accident three weeks after the ferry sank. To make matters worse, neither of the two candidates for the prime minister was appointed for ethical reasons, increasing criticism of President Park’s administration (positive feedback). The controversy ended with the resigned Prime Minister being reassigned to his position 12 weeks after the disaster. This failure converted the negative feedback to positive feedback.

The other negative feedback was associated with the pursuit of Mr. Yoo. The president charged the owner of the Sewol Ferry’s company, Yoo Byung-eun, with crimes because he ordered the reconstruction of the Sewol Ferry before the accident. Many observers presumed that the remodeled boat was loaded above its capacity, one of the main contributors to the accident. President Park’s ruling party, the government, and the news media described Yoo Byung-eun as cunning. The government planned to recover the rescue mission operation costs by fining Yoo and his family while the ruling party drafted the Yoo Byung-eun Law (Kim 2014). However, the government failed to find him. His body was later found in a pile of dead homeless people, undermining the Park administration’s abilities. Thus, the Park administration intended to provide negative feedback, chasing Mr. Yoo, which converted into positive feedback guiding new policies (Cho and Jung 2019).

Subsequently, President Park’s administration decided to dismantle the KCG on May 19, 2014, due to the KCG’s poor performance in rescuing people and created the MPSS to maintain stability and absorb responsibilities from the KCG (positive feedback). After the June 4 local election, long debates on the Sewol Special Act included a special investigation by the committee comprising liberal and conservative politicians, which lasted until the end of September. Ultimately, they passed the three Sewol Acts on November 7, 2014, which could be viewed as positive feedback confirming the change (Cho and Jung 2019). In the meantime, officials announced the end of the mission to retrieve the bodies on November 11, 2014, while the Korean government established the MPSS, which merged both KCG and the National Emergency Management Agency, on November 19, 2014. These events could be described as negative feedback supporting new safety.

HTE from the content analysis

Meanwhile, the liberal and conservative newspapers’ reactions to each feedback and symbol varied (see Tables 1 and 2).

Tables 1 and 2 show the newspapers’ varied opinions and responses to symbols and feedback. The liberal newspaper tended to blame the conservative Park administration more and express more positive opinions and condolences to the victims, their families, and survivors compared to the conservative newspaper. This also implies that the conservative newspaper was more lenient towards the conservative Park administration compared to the liberal newspaper due to less negative opinion.

Regression analysis and opinion network

The previous section described a case study and content analysis of newspapers’ responses to different types of symbols and feedback depending on their stance after the Sewol Ferry Disaster. This drove me to conduct the opinion network and regression analysis to uncover a more rigorous relationship. A case study could not assess how each media’s negative opinion reflected the symbols and feedback while controlling for other variables. To increase reliability, validity, and objectivity, I further examined whether negative opinions of newspapers with different ideologies reflected symbols and feedback using regression analysis and opinion networks.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

Korean citizens expressed their condolences, pities, and sympathies and comforted victims and victims’ families, especially high school victims and survivors, after the Sewol Ferry Disaster. Symbols convert complex ideas into simple ones by simplifying a situation with emotion and cognition. Innocent, helpless, and unblameable victims are symbolic during disasters (Schneider 1995). Just as a person, word, phrase, or speech can be a symbol (Edelman 1964; Schneider 1995), mentioning the victims delivered a symbolic message quickly and effectively during the Sewol Ferry Disaster. Society’s consensus or division on issues is intertwined with people’s emotions, which is a useful starting point for analyzing a mass response (Edelman 1964). During disaster, victims, their families, high school victims, and survivors were offered condolences, pities, sympathies, and comforts and thus represented a symbolic element of innocence and helplessness with positive opinions to boost people’s emotions, such as affective states and feelings. In the meantime, the media reported the number of retrieved bodies to the public. This study considered the number of found-missing bodies as a cognitive symbol because people might easily understand information about the number of found-missing bodies. Expressing condolences to the victims, their families, and survivors (emotional symbols) and sporadically discovering the victims’ bodies (cognitive symbols) triggered people’s emotions and cognition. The policy entrepreneurs used these symbols to further blame President Park’s administration and employed them to couple streams (Zahariadis 2007).

Accordingly, hypothesis 1 was generated to investigate how emotional and cognitive symbols (victims) influence the negative opinion of President Park’s administration, which initiated the policy change during the agenda-setting and policy formulation to avoid taking the blame. Thus, I assumed that the symbols, as one of the manipulating strategies of policy entrepreneurs, play an important role in blaming President Park’s administration. I tested the influence of emotional and cognitive symbols on the negative opinion of liberal and conservative newspapers by pushing for policy change, considering symbols have an emotional and cognitive effect.

Hypothesis 1.1: Emotional symbols (positive opinion of the victims) increase the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 1.2: Cognitive symbols (the number of retrieved bodies) increase the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 2

The political system experienced and responded to both positive and negative feedback. Thus, responses of the Park administration, the politicians, policy actors, and the media to the Sewol Ferry Disaster produced positive and negative feedback. Considering that the negative feedback reduced the negative opinion by stabilizing and reaching equilibrium while the positive feedback increased the negative opinion by encouraging people’s attention increase, hypothesis 2 was proposed to examine how the positive and negative feedback influenced the negative opinions of liberal and conservative newspapers.

Hypothesis 2.1: The resignation of Prime Minister Chung (positive feedback) increased the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 2.2: Chasing Mr. Yoo (positive feedback) increased the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 2.3: Announcing the Dismantling of KCG (positive feedback) increased the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 2.4: Passing Bills and Ending Mission (positive and negative feedback) did not influence the negative opinion of President Park’s administration because both feedback responses were canceled out.

Hypothesis 2.5: Establishing MPSS (negative feedback) decreased the negative opinion of President Park’s administration.

Hypothesis 3

Considering prior results, I wanted to compare how newspapers with different ideologies (liberal and conservative news) responded to emotional and cognitive symbols and positive and negative feedback under the conservative administration. From the HTE’s perspective, the newspapers can be biased. Under the conservative administration, the liberal newspaper would be expected to express a negative opinion of the conservative administration more frequently than the conservative newspapers. Expanding on hypotheses 1 and 2 of the case study, I proposed the following:

Hypothesis 3.1: Under the conservative administration, the conservative newspaper is more lenient towards the conservative Park administration and thus less likely to express a negative opinion of President Park’s administration when responding to emotional and cognitive symbols than the liberal newspaper.

Hypothesis 3.2: Under the conservative administration, the conservative newspaper is more lenient towards the conservative Park administration and thus less likely to express a negative opinion of President Park’s administration when responding to positive and negative feedback than the liberal newspaper.

Variable and measurement

Dependent variable: negative opinion as a forecast of policy change

Regarding the dependent variable, this study analyzed the negative opinions of the agencies and actors after the Sewol Ferry Disaster because they can influence policy change and politicians’ reelection and reputation. Due to the poor performance of the government and relevant agencies and people, many negative opinions dominated the entire nation. The negative opinion toward President Park’s administration provoked policy change, as described in the above case study. Citizens, media, and social advocates offered condolences, which served as symbols, to victims of the Sewol Ferry Disaster, while the three Sewol Acts and other policies or feedback were created to respond to a grievance. These influenced the negative opinions of the liberal and conservative newspapers. Accordingly, this study considered the magnitude of negative opinion as an indicator of the policy change after the Sewol Ferry Disaster. I used centralityFootnote 34 [degree centrality of each node (in-degreeFootnote 35and sum of weight)] to measure certain variables. For the measurements of all variables, see Table 3.

Control variables

Regarding control variables, the government influenced the degree of blame imposed on President Park’s administration. However, the entire government, except for the chief of ministries, did not represent President Park’s administration because most bureaucrats were not affiliated with President Park or political parties. Thus, I separated the negative opinion of the government and used it as a control variable because, in South Korea, government employees are prohibited by law from enrolling in political parties. Especially, KCG (a government agency populated by government employees) was given the greatest responsibility for the accident. I also separated the KCG from the government and controlled it to investigate the different negative opinions on the Park administration in the liberal and conservative newspapers. In addition, economic factors could have influenced blame attributed to President Park’s administration; thus, I controlled for them.

Furthermore, the partisan shift also influenced policy change (John 2006). Thus, I controlled for the partisan shift before and after the June 4 local election. I used the measurements in Table 3 to control for these variables.

Results and findings

Table 4 describes the data. I collected the data from newspapers, government documents, the Korea Composite Stock Price Index (also called KOSPI), and editorials from Hankyoreh’s and Chosun newspapers’ websites. Then, I conducted the content analysis with the second coder (see Appendix 1 for more detail). Because the dependent variable was the negative opinion, the values were all 0 or less than 0. These values show that the conservative newspaper blamed President Park’s administration less than the liberal one, while the conservative newspaper used emotional symbols less than the liberal newspaper (see Table 4), consistent with the previous analysis (see Table 1).

I analyzed the data based on prior studies and data, as shown in Table 5. The overall analysis showed that emotional symbols have more influence on the negative opinion of liberal rather than conservative newspapers, while cognitive symbols had no effect on the negative opinion in both liberal and conservative newspapers. Additionally, the negative opinion on the positive and negative feedback varied depending on the situation.

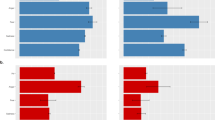

Explanations of emotional and cognitive symbols from MSA influence on negative opinion

Regarding Hankyoreh and Chosun newspapers, Table 5 shows that emotional symbols were used significantly more than cognitive symbols to blame President Park’s administration, regardless of the newspaper’s perspective.Footnote 36 This indicates that media reacted more sensitively to emotional than cognitive symbols. Figure 5 illustrates that Hankyoreh’s negative opinion dropped slightly below – 0.4, while the negative opinion of Chosun decreased to around – 0.3. These findings support that emotional symbols, rather than cognitive symbols, influenced the negative opinion of President Park’s administration, particularly in the case of the liberal newspaper Hankyoreh. Regarding hypothesis 3, under the conservative administration, the liberal newspaper would be more likely to employ symbols compared to the conservative one, implying that the conservative newspaper was more lenient compared to the liberal one.

Explanations of positive and negative feedback in PET and its effects on negative opinion

The results in Table 5 show how the liberal and conservative newspapers responded to the positive and negative feedback under the conservative administration. The liberal newspaper Hankyoreh (then supporting the opposing party) reacted more sensitively to the positive and negative feedback compared to the conservative newspaper Chosun (then supporting the ruling party).Footnote 37 On the other hand, the conservative newspaper responded to the resignation of Prime Minister Chung. The newspapers’ different responses imply that they were not objective, further suggesting that positive and negative feedback responses do not always work in unison. While the positive feedback should theoretically facilitate the change, the positive feedback on the prime minister’s resignation, which might have originally intended to reduce negative opinion, increased the negative opinion of both newspapers, whereas the failed policy of negative feedback seemed to boost the negative opinion regardless of the newspaper’s perspective.Footnote 38 This positive feedback transformed from negative feedback and boosted the negative opinion of President Park’s administration in both newspapers.

On the other hand, the positive feedback on Mr. Yoo, which might have also aimed to reduce negative opinions, did not influence either newspaper’s negative opinion of President Park’s administration.Footnote 39 In addition, announcing the dismantling of KCG only exacerbated the liberal newspapers’ negative opinion of President Park’s administration. Regarding passing the bills (three Sewol Acts) and ending the mission, when the positive and negative feedback was mixed, negative feedback tended to surpass the positive feedback in the liberal newspaper.Footnote 40 Establishing the MPSS might not be considered negative feedback because issues surrounding the Sewol Ferry Disaster could have been eliminated while new issues could have emerged. Furthermore, even though some populace argued that the Sewol Ferry was still critical, most people felt the Sewol Ferry issue was too tedious and obsolete.

Comparing the symbol and feedback influence on negative opinion from the HTE perspective

Table 6 shows that the conservative newspaper was more lenient than the liberal one when criticizing the Park administration.

Regarding hypothesis 3, the liberal newspaper was more likely to employ the symbols compared to the conservative one under the conservative administration. The results imply that emotional and cognitive symbols and positive and negative feedback do not always cause the same response, considering the ideology of unique media outlets, as shown in Tables 5 and 6. Emotional symbols raised negative opinions of President Park’s administration. Regarding the magnitude of emotional symbols, while both newspapers blamed the Park administration, the liberal newspaper Hankyoreh expressed stronger negative views than the conservative newspaper Chosun. This also shows that the liberal newspaper, contrary to the conservative newspaper, utilized emotional symbols rather than cognitive symbols to blame conservative President Park’s administration.

Tables 5 and 6 show that under the conservative administration, positive feedback could increase the momentum of policy change by boosting the liberal newspaper’s negative opinion rather than the conservative newspaper. Both tables show that liberal and conservative newspapers criticized the failed feedback, such as the prime minister’s resignation.Footnote 41 Furthermore, the liberal newspaper responded to dismantling KCG and establishing MPSS with significantly more negative opinions compared to the conservative newspaper. Thus, the liberal newspaper was more sensitive than the conservative newspaper during the conservative administration. These results generally support the HTE argument that people with opposing ideologies tend to oppose the opposition’s policies more strongly. In other words, the conservative newspaper is more lenient than the liberal newspaper under the conservative administration.

In addition, the control variable analysis supported this study’s argument. Interestingly, the conservative newspaper blamed the KCG rather than the conservative Park administration regarding the control variables in Table 5, while the liberal newspaper blamed the government. The government is interchangeably called conservative Park administration, even though not all government employees are partisans. Thus, the government could be another alternative target of the liberal newspaper as an opponent of the conservative Park administration. This implies that the liberal newspaper blamed the government as an entity linked to the Park administration. On the other hand, the conservative newspaper expressed its negative opinion of KCG, suggesting that the conservative newspaper believed that the Park administration was not directly responsible for the Sewol Ferry Disaster. Thus, it attributed responsibility to the KCG because the KCG had the primary and direct obligation to rescue students from the sinking ship but failed. Blaming the KCG instead of the Park administration indicates that the conservative newspaper supported the conservative Park administration, confirming the HTE.

Alternative analysis with opinion network

I added an alternative example to visualize the negative opinion changes to increase the understanding of the opinion network. To visualize hypothesis 2.4 in Table 5, Fig. 6 illustrates how the magnitude of the negative opinion of President Park in Hankyoreh decreased after the passing of the bills and the ending of the body-retrieval mission. Figure 6 illustrates how the liberal newspaper decreased its negative opinion under conservative administration based on the HTE. The figure depicts the reduced negative opinion of President Park and the liberal newspaper’s response to the feedback using the opinion network under the conservative administration. This helps scholars or laypersons understand the change more easily without a case study or regression analysis.

Discussion and conclusion

This study revealed the mechanisms underlying the use of the symbols in the MSA, feedback in the PET, and the newspapers’ reactions to the policy process in line with the HTE. I used qualitative and quantitative evidence to describe the use of symbols and feedback in the newspaper with different ideological perspectives after the controversial disaster. Although the newspapers influenced agencies and actors’ opinion networks throughout policy processes, studies on symbols in MSA and positive and negative feedback in PET using the opinion network are limited. Furthermore, how symbols and feedback work according to a newspaper’s political ideology has not been studied in public policy from the perspective of HTE. The qualitative case study described the story of the Sewol Ferry Disaster with the symbols and feedback, while the quantitative part of the study with an opinion network described the function of the symbols and feedback based on the newspaper’s ideology. The qualitative and quantitative studies clarified how different ideological perspectives of media react to symbols and feedback regarding negative opinions.

The qualitative and quantitative results overall supported the propositions and hypotheses revolving around the Sewol Ferry Disaster and identified further aspects that did not support the initial propositions and hypotheses. The case study results, regression analysis, and opinion network analysis yielded consistent results. The findings confirmed that in terms of the MSA, the policy entrepreneurs used primarily emotional symbols rather than cognitive symbols to increasingly blame President Park’s administration. Additionally, this study revealed that the liberal newspaper responded to the symbols more sensitively and that emotional symbols were more influential than cognitive symbols, regardless of the newspaper. These results support the importance of emotion in increasing policy actors’ awareness of their negative opinions. This finding also implies that the masses tend to respond to impressive speech rather than facts (Edelman 1964) and that emotional symbols boost negative opinions more than cognitive symbols.

Regarding the positive and negative feedback in PET, the opinion network depicted in the liberal newspaper reacted to the Sewol Ferry sinking more sensitively compared to the conservative newspaper. This also shows that even with the same feedback, negative opinions varied depending on the newspapers’ perspectives, suggesting that the opposing political newspaper stance with the current administration tends to be more sensitive than the supportive political newspaper stance of the current administration. In theory, positive feedback facilitates change by increasing negative opinions, while negative feedback thwarts change by decreasing negative opinions. However, this argument applied mostly to liberal newspapers under the conservative administration, even though the feedback effect depends on the situation. In other words, the failure of negative feedback could change to positive feedback through criticism. This is consistent with the claim that a definite effect of positive and negative feedback does not exist due to its time variance (Larsen 2019) and that it is difficult to discern positive and negative feedback (Cho and Jung 2019). Therefore, this study suggests reconsidering these issues.

Regarding HTE, the conservative newspaper was more lenient in responding to symbols and feedback responses compared to the liberal one under the conservative administration. Although the newspapers pursued their objectivities, their use of symbols and responses to feedback described in the newspaper did not always work simultaneously as expected. If they were unbiased and objective in pursuing objectivities, their responses to the symbols and feedback should have been the same. The findings of this study imply that the newspaper symbols and feedback responses differed according to their stances, consistent with HTE’s main argument. Thus, the research findings employing the method of opinion network and content analysis extended the application of MSA, PET, and HTE to the policy theories.

This research focused on the symbols and feedback employed in politics using opinion networks. The results of this study can help researchers determine and empirically test how symbols and feedback influence negative opinions (Larsen 2019). Ultimately, this study used the opinion network with the figure of nodes and links to describe differential responses of media with different ideologies. The findings provide qualitative and quantitative evidence supporting the dynamic effects of symbols and feedback on negative opinions within the MSA and PET frameworks. Additionally, this study added a negative opinion as another way to depict attention. Using the opinion network allowed us to quantitatively measure attention and opinion and visualize the opinion and punctuation in addition to budget and attention.

Additionally, regarding the data collection method, I collected opinion network data by merging opinion mining and network analysis with content analysis based on the protocol, significantly contributing to the works of many scholars and practitioners. This method of data collection helps scholars study media and government documents. Moreover, the opinion network can visualize the opinion change in the published text. It could be applied in technology to describe the positive and negative relationships between actors in news content with graphics. Thus, readers from all walks of life could easily and quickly understand the basic relationships between actors, agendas, and issues in political and practical situations without reading the entire text.

This study implies that public policy scholars and practitioners can apply this method to consider the media’s responses while accounting for their administration’s and newspapers’ political stances. Policy actors must consider the symbols and feedback of the policy and media stance when introducing or implementing policies.

A future study could analyze other controversial issues and their influence on the opinion of other types of media besides newspapers. The media influence the government’s performance and evaluation of people, the populace, or constituents. Even though this study examined the newspapers’ responses, future studies can employ opinion networks and big data to evaluate policy responses or address other issues in not only newspapers but also other media’s (social media, online websites, blogs, replies, and all online text) standpoints and opinions because the newspaper’s audience has been decreasing and becoming less influential. Future research could investigate the effects of other symbols and evaluate whether the feedback effects are canceled out, why they occur, when they are altered, and how positive and negative feedback can be discerned depending on the ideology, country, language, or geographical area.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available in the editorial section of the Hankyoreh's and Chosunilbo’s newspaper repositories at https://www.hani.co.kr and https://www.chosun.com, respectively.

Notes

The Blue House is the Korean equivalent of the White House.

“Couple” the stream is a terminology in public policies implying merging and manipulating the three streams to make a change.

According to Murray Edelman, as stated in his seminal text, The Symbolic Uses of Politics, “man is constantly creating and responding to symbols” (Edelman 1964: 178). Edelman mentioned that a “symbol can be understood as a way of organizing a repertory of cognition into meaning” (Edelman 1971: 34). As long as a symbol represents beyond objective content with a special meaning or value about an issue, symbol can be anything, “a word, a phrase, a gesture, an object, a person, an event” (Elder and Cobb 1983; Schneider 1995: 12), “acts, speeches and gestures” (Edelman 1964: 188) with embedded meaning or value about an issue. A symbol makes an idea easy to understand and transmits it by way of a “short cut” and “stereotyped” image, such as pictures and TV images (Birkland 1997: 12). This helps symbols define an issue (Cobb et al. 1976).

Emotion. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/emotion Accessed 8 September 2023

Cognitive. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/cognitive Accessed 8 September 2023

The main concept of “punctuated equilibria” originated from the “discontinuous tempos of change” (Gould and Eldredge 1977: 145).

Policy monopoly is defined as the situation in which only a few relevant people can access the policy process. A single widely acknowledged image that supports the policy is associated with policy monopoly (Baumgartner et al. 2014). Policy monopoly refers to “established interests tend to dampen departures from inertia until policy mobilization” (Baumgartner et al. 2014: 67). A policy monopoly is an image created from the supported policy image (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). When a broken policy monopoly brings about a shift in how the issue is defined, this issue is enforced to move from the subsystem to macro politics (True et al. 2007).

PET counts on the policy image mechanism as one way to understand policy (Baumgartner et al. 2014). Policy image consists of mixed components of the “empirical information and emotive appeals” (Baumgartner et al. 2014: 66) associated with “core political values” communicated to the public with simplicity and directiveness (Baumgartner and Jones 1993: 5-7; Baumgartner et al. 2014: 64).

Friction is another indicator of policy change. Friction delays reaction to issues until the pressure to overcome the resistance from the institution, which leads to punctuation (Baumgartner et al. 2014).

This is also called “feeding frenzy” and “bandwagon effect” (Baumgartner et al. 2014: 64–65).

The opinion mining’s essential objective is to extract the orientation and strength of sentiments from subjective information data because the sentiment information influences the opinion network (Zhou et al. 2009).

As one of the deductive approaches, theoretical propositions come from theoretical models (Cavaye 1996). A case study followed the outline of the researchers’ theoretical proposition for logical prediction and conclusion (Yin 2014). This is useful for theory development (Yin 2014) based on the tested propositions models (Cavaye 1996; Cho and Jung 2019).

The network analysis investigates the relationship between the senders and receivers, that is, starting points and ending points with a direction between them, although it can also show the relationship without opinion directions.

Most messages are assumed to reflect the psychological state (Riffe et al. 2014). Thus, content analysis has been employed in journalism, sociology, political science (Rowling et al. 2011), psychology, and economics (Riffe et al. 2014). On the other hand, content analysis can use different kinds of rhetorical objects as data (e.g., interviews, letters, diaries, journals, school essays, and newspaper stories) (Zullow et al. 1988). Because these measures are unobtrusive, they do not suffer limitations inherent in questionnaire or survey data collection.

Opinion mining is also as known as “sentiment analysis” (Liu 2012: 1). Sentiment is closely related to opinion. Sentiments can be individual evaluations, “usually measurements of positive or negative affect of one person for another” (Wasserman and Faust 1994: 37). Opinion mining has also been referred to as “sentiment analysis, opinion extraction, sentiment mining, subjectivity analysis, affect analysis, emotion analysis, review mining, etc.” with marginal different task (Liu 2012: 1).

Opinion network is based on the “implicit opinion orientation” in online context, unlike the traditional social network connecting people through “explicit” relationships, such as friendship, consumption, and employment (Zhou et al. 2009: 266).

Unlike the opinion network, the semantic network identifies the “most frequently occurring words in a text and determines the pattern of similarity based on their co-occurrence” (Doerfel and Barnett 1999: 592) without positive and negative relationship.

The chain of evidence covers “the links—showing how findings come from the data that were collected and in turn from the guidelines in the case study protocol and from the original research questions—that strengthen the reliability of a case study’s research procedures” (Yin 2014: 38).

I did not have to collect data from all media sources because studies indicate a high degree of similarity in issue content across different media outlets (Thesen 2013; Vliegenthart and Walgrave 2008). Since my interest here was not to compare different media, two representative newspaper sources with different political ideologies were sufficient to compare the effects of their different ideologies on the negative opinion.

Editorials in Korean and U.S. newspapers are written differently. The editorials in the U.S. do not necessarily share the same perspective as the newspaper articles. However, newspapers editorials in South Korea generally share the perspectives of the articles because editors and editorial writers are all considered representatives of newspapers.

“An edge list is a two-column list of the two nodes that are connected in a network” (Shizuka Lab 2013).

Although it utilizes a computer, it could cause errors due to computer’s reasoning limitations; thus, this study conducted the coding manually, which took several months. Two coders coded the data. The first coder was the author of this manuscript. The second coder was a judge and visiting scholar who majored in law and had multiple experiences as a judge in South Korea. To boost the data accuracy, two coders added or corrected mistakes and errors due to the missing nodes and opinions based on mutual agreement after checking intercoder reliability. In the end, 100% intercoder reliability was achieved after adjusting codes through discussion. This improved the data accuracy and increased the number of data without missing nodes and opinions.

Media, diversity, and content manipulation. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2015/south-korea Accessed 22 February 2016.

However, a few opponents have argued that most of the budget increase was derived from increased social overhead capital investment, such as road maintenance and construction building dam, rather than the expansion of safety projects and personnel (People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy 2014).

The Sewol Special Act (act to investigate the causes of the disaster for prevention of future disasters), the Government Organization Act, and the Yoo Byung-eun Act (Act on Regulation and Punishment of Criminal Proceeds Concealment).