Abstract

Since the Chinese government proposed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, Chinese firms have been actively investing in countries participating in BRI. What kinds of firms are willing to respond to this geopolitical policy? According to resource dependence theory and resource-based view, this study examines the impact of CEO political connections on outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) in the context of BRI and its boundary conditions. The results show that CEO political connections can promote firm OFDI under BRI. However, a good institutional environment in the home region and host country weakens the positive impact of CEO political connections. Furthermore, central state ownership has a substitute role for CEO political connections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

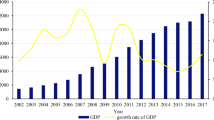

The Chinese government put forward the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, intending to promote the development of the regional economy and solve excess production capacity through government-leading investment (Li et al., 2022). Chinese companies respond to it actively. According to the 2021 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment, the investment flow of Chinese companies to countries along the Belt and Road reached 24.15 billion dollars, double that of 2012, accounting for 13.5% of 2021 China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) flow. So, why are firms affected by the government and then decide to invest in countries along the Belt and Road?

BRI is essentially a geopolitical policy (De Beule and Zhang, 2022; Lewin and Witt, 2022). Although its original intention is to use infrastructure construction projects to help host countries and Chinese multinational enterprises (MNEs) obtain economic benefits, it is widely assumed that these projects are diplomatic means to help the Chinese government gain political benefits (Zhang and Xiao, 2022; Luise et al., 2022). Therefore, the Chinese government encourages firms to participate in BRI. However, extant research has not clearly shown in what ways the government makes firms willing to respond to this initiative, in other words, what government-related factors influence firms to invest in countries along the Belt and Road.

The relationship between the government and firms can affect firms’ willingness to participate in BRI. The firm-government relationship is shown in many forms, including CEO political connections (Li et al., 2018; Sun and Ai, 2020; Wu and Ang, 2020; Marquis and Qiao, 2020). However, related studies are conducted in situations that are not affected by government policies, and scholars found mixed results. Some scholars argue that domestic political connections of the CEO or top management team (TMT) negatively affect OFDI. Sun and Ai (2020) found that CEO political connections increase MNEs’ operational costs because firms need to burden heavy human resource costs to maintain political connections. Marquis and Qiao (2020) argued that the communist ideological influence of Chinese founders, which portrays foreign capitalism as negative, may diminish firms’ capacity to attract foreign investments and pursue international expansion. Shirodkar et al. (2022) also found that TMT domestic political connections hinder OFDI. But Li et al. (2018), and Wu and Ang (2020) argued that political connections can promote OFDI. They took foreign ties into account because firm OFDI not only needs to obtain domestic resources but also needs to seek foreign resources and found that TMT domestic political connections and foreign ties have a positive interaction with OFDI (Li et al., 2018; Wu and Ang, 2020). These mixed conclusions may be due to the neglect of specific context. The success of firms’ OFDI hinges not only on the support of their home country’s government but also on obtaining permission from the host country, so only taking the CEO’s domestic political connections into account but ignoring the relationship between host countries and home countries is not appropriate. Therefore, our study is conducted in the context of the BRI, which naturally assumes a positive relationship between the home country and the host country as long as the BRI cooperation agreement is upheld, and we aim to examine the impact of CEO political connections on a firm’s OFDI under BRI.

Furthermore, the utility of CEO political connections depends on the conditions in the home region and host country, especially the institutional environment, which affects the fairness of laws and regulations. In regions with a weak institutional environment in the home country, Guanxi (Chen et al., 2013) may be very important in seeking resources. In a host country with a weak institutional environment, political connections may be more important in doing business. Here we further explore boundary conditions of CEO political connections’ effect.

There are three contributions to our study. First, our study supplements the factors affecting OFDI under BRI and its boundary conditions. From the perspective of the firm-government relationship, we find that it is CEO political connections that make firms willing to respond to BRI actively, in other words, the Chinese government uses CEO political connections to advance BRI. Also, scholars have drawn inconsistent conclusions about how CEO political connections affect OFDI (Li et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Sun and Ai, 2020; Wu and Ang, 2020; Marquis and Qiao, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Shirodkar et al., 2022) because they have not considered specific contexts. Our study takes BRI, a government initiative, into account to clear the relationship between CEO political connections and firm OFDI.

Second, our study contributes to the literature on the non-market strategy of MNEs by clarifying how non-market strategy in the form of CEO political connections affects a mixture of market and non-market strategies. Although OFDI is one of the market strategies, international expansion in designated countries based on a specific geopolitical policy can also regarded as a non-market strategy, as it seeks political legitimacy in the home country by responding to the government’s goals (Baron, 1995; Baron and Diermeier, 2007; Holburn and Vanden Bergh, 2014; Dorobantu et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2022). This study not only provides new evidence at this point but also extends our understanding of non-market strategies that firms employ.

Finally, our study supplements research on OFDI of emerging market firms under government policies, especially for firms with CEO political connections. Prior research found that good foreign ties between countries can provide good bridges for firms’ investment (Li et al., 2018; Wu and Ang, 2020), and our study more specifically analyzes firms’ OFDI in an emerging market by using foreign ties generated from a policy.

Theoretical development and hypotheses

CEO political connections and OFDI

The firm-government relationship has been studied deeply under resource dependence theory (Hillman et al., 2009; Ahammad et al., 2017). CEOs with broader social networks can better gain access to external resources (Zhang et al., 2022). If a firm’s CEO has political connections, the CEO can assist the firm acquire more resources from the government directly or indirectly than firms without political connections (Shi et al., 2014). These resources include not only valuable advice and experience on how to handle the relationship with the government, and visits of officials through their networks (Lester et al., 2008), but also perceptions of risks and opportunities within the political landscape, and utilization of favorable policies, incentives, and assistance (Peng and Luo, 2000; Hillman, 2005; Li and Zhang, 2007; Hillman et al., 2009). For BRI, firms with CEO political connections can obtain more intangible resources about BRI. The CEOs with political connections can attend some important government conferences, such as the Session of People’s Congress and People’s Political Consultative Conference, in which important policies, including BRI, are discussed. For example, they can learn from conferences that to cooperate with countries along the Belt and Road, firms should be concerned about the “Five Links”, i.e., policy coordination, infrastructure development, investment and trade facilitation, financial integration, and cultural and social exchange. These CEOs can also learn about the priorities in the cooperating mechanisms stated in contracts between China and a particular host country. After absorbing this knowledge, CEOs, along with their firms, can understand BRI better.

These resources can help the firm form advantages. First, CEOs with political connections have easier access to information related to investment under BRI, which reduces transaction costs. OFDI usually needs financing, such as bank loans, and other support from the home government, CEOs with political connections can help their firms obtain these resources easily. Second, a firm with political connections can better face political risks. The CEO can convince the domestic government to address risks present in the host country. Cases of Shell, Volkswagen, and Lockheed Martin have shown that, by using their domestic political connections and the relationship between governments in host countries, they have overcome regulatory obstacles, and achieved commercial success in Nigeria, China, and Russia (Frynas et al., 2006). Third, CEO political connections can help the firm enhance legitimacy. CEO who connects well to home government may become a member of business delegations and accompany political leaders to visit foreign countries. CEOs participating in state visits can improve the legitimacy and status of the firm, thus leading to better investment opportunities. Since CEO political connections can bring advantages of fewer transaction costs, lower political risks, and higher legitimacy, firms should take advantage to invest abroad (Popli et al., 2022).

Utilizing knowledge about BRI obtained from conferences that CEOs with political connections attend, firms can find more opportunities. For example, benefiting from policy coordination, firms can conduct some large projects by jointly formulating plans and measures for promoting regional cooperation and resolving problems in cooperation through communication; benefiting from infrastructure development, firms in transportation, electric power, construction, and communication industries have more opportunities; benefiting from investment and trade facilitation, firms can seize investment and trade opportunities by taking advantage of policies that remove barriers to investment and trade; benefiting from financial integration, firms have easier access to financing; benefiting from cultural and social exchange, citizens in countries along the Belt and Road can better understand Chinese culture, and firm foreign liability decreases.

Moreover, firms with CEO political connections also know that they should invest abroad with the help of government policies. The priorities in contracts between China and host countries can not only reduce the risks of infrastructure financing and construction but also gain support and incentives from countries along the Belt and Road. Without the support of the government, the efforts of firms alone are not enough to overcome the difficulties of cross-border logistics development caused by poor connectivity of logistics networks or low customs clearance efficiency (Dumitrescu, 2015; Wang and Chou, 2020). Research has found that due to the priority of facility connectivity of BRI, the flow of factor endowments of production is smoother, and production costs reduce significantly, thus total factor productivity increases and trade costs decline (Yang et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2022).

Taking these advantages, firms with CEO political connections invest more in countries along the Belt and Road. With fewer transaction costs, lower political risks, and higher legitimacy, OFDI under BRI becomes more facilitated, so firms are willing to do it. With a deeper understanding of BRI, firms with CEO political connections can seize opportunities brought by policies and participate in “Five Links” and priority projects actively; thus, the scale of their ODFI under BRI increases. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis:

H1: The firm with CEO political connections has a larger scale of OFDI under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The moderating role of institutional environment in the home region

The institutional environment is the “rule of the game” affecting firms’ economic activities, including laws, regulations, and customs related to politics, economy, and culture (North, 1990; Williamson, 1991; Dorobantu et al., 2017), which is different from CEO political connections but is related to it to some extent. CEO political connection is a type of Guanxi, which is an informal institution deeply rooted in Chinese culture and history and refers to the use of networks in personal relationships to gain favor (Park and Luo, 2001). Based on this conception, CEO political connection is a neutral term, not a derogatory term. Although there are some negative cases of using CEO political connections, such as illegal mediation or bribery, there are some positive cases, for example, CEOs participate in the formulation and implementation of government policies through legally recognized channels such as Congress. In this study, we tend to believe that CEO political connection refers to the good side of it. On the other hand, the institutional environment is a mix of formal institutions and informal institutions. The formal part of the institutional environment may prevent negative cases of using CEO political connections but does not prevent positive cases of using CEO political connections.

A good domestic institutional environment means that formal rules are clear and transparent, and firms need to gain opportunities through market competition (North et al., 2009; Holcombe, 2010). This market-supporting institutional environment can decrease transaction costs, and prompts firms to engage in transactions through the market as opposed to personal networks or political influence (Peng, 2003; Young et al., 2014). Sun et al. (2015) found that the more open the institution in the home country is, the larger the scale of the firm OFDI. So, in a better institutional environment in the home region, firms obtain government support for investment abroad more fairly, and the advantage of lower transaction costs brought by CEO political connections is reduced.

Contrarily, if the institutional environment in the home region is bad, it is difficult for firms to gain the home government’s support for OFDI. In this condition, CEO political connections are very important for firms seeking opportunities to invest abroad. CEOs with political connections can help firms find resources such as more bank loans, lower financing capital, and so on (Su and Fung, 2013), so these firms’ OFDI under BRI is smoother than that of firms without CEO political connections. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis:

H2: A good institutional environment in the home region weakens the positive effect of CEO political connections on OFDI under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The moderating role of institutional environment in the host country

Firms benefit from resources brought by CEOs, but this is not useful in all host countries. Foreign investors are typically inclined to invest in a country that offers a fair and competitive market, where the local government refrains from arbitrary intervention in business affairs (Henisz, 2000; Globerman and Shapiro, 2002; Bevan et al., 2004). Such a fair competition environment can ensure that institutions implement strict and fair policies for all market participants (Rothstein and Teorell, 2008); in other words, different investors are equal. Therefore, if the institutional environment in the host country is good, it is less likely that the local government discriminates against different foreign investors, and Chinese firms with different characteristics are treated as equal (Meyer et al., 2014). Thus, benefits generated from CEO political connections are reduced.

On the contrary, if the institutional environment in the host country is bad, foreign firms face a disadvantage when compared to local firms. Local government is more likely to protect local firms and discriminate against foreign firms by setting up some barriers for non-economic reasons. In this situation, firms with CEO political connections have to use resources brought by CEOs to contact local governments, and thus obtain better treatments and reduce political risks. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis:

H3: A good institutional environment in the host country weakens the positive effect of CEO political connections on OFDI under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The summary of the theoretical model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data and sample

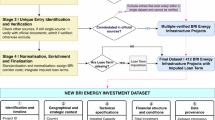

We collect macroeconomic data of countries participating in BRI and accounting and financial data of Chinese A-share listed companies from China Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR) databases. The data on CEO political connections are mainly from the CSMAR database, and missing values are supplemented manually according to the CEO’s profile. The data on the institutional environment in the home region is obtained from the Wind database, and the Report of Marketization Index of China, and the data on the institutional environment in the host country is obtained from the World Bank.

Our sample is A-share listed companies from the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange with companies with OFDI in countries participating in BRI from 2013 to 2021. Chinese government proposed BRI in 2013, so the starting year of our sample is 2013. We eliminate the following observations: (a) overseas subsidiaries in tax havens such as Cayman Islands and Bermuda, (b) firms with ST or *ST in the research year, (c) firms in the financial industry, (d) firms exiting overseas subsidiaries in the research year, and (e) observations with missing values. Finally, we obtained 3226 observations of company-host country-year.

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in our study is the scale of OFDI under BRI. It is measured by the number of overseas subsidiaries in a single host country (García-Canal and Guillén, 2008; Sun et al., 2015).

Independent variable

The independent variable is CEO political connections (Politics). Politics has many measures, such as lobbying and campaign contributions (Shirodkar et al., 2022), bribery (Shaheer et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2022), and whether the CEO is a member of Congress (Li et al., 2018; Wu and Ang, 2020; Zheng et al., 2022). In this study, we focus on how the CEO uses policy resources from Congress to affect OFDI under BRI, so lobbying, campaign contributions, and bribery are not our concern. Therefore, considering the actual situation in China and keeping consistent with previous studies (Li et al., 2018; Wu and Ang, 2020; Zheng et al., 2022), Politics is measured by a dummy variable. If the CEO is currently or ever served as government secretary or was elected as a member of the People’s Congress (NPC), or People’s Political Consultative Committee (CPPCC), the variable is coded as 1, otherwise 0.

Moderators

There are two moderators in our study, the institutional environment in the home region (Marketization) and the institutional environment in the host country (WGI). Since in China, different regions’ institutional environment is quite different (Xu et al., 2019), the institutional environment in the home region can be measured by the marketization index of the province where a firm is located in China (Gao et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019). The marketization index consists of five dimensions: the government-market relationship, the growth of a non-state-owned economy, the development level of the product market, the development level of the factor market, and the progress of market intermediaries and legal framework (Wang et al., 2007). The higher the marketization index is, the better the institutional environment of a province is. The institutional environment in the host country is measured by the World Governance Indicator (WGI) from the World Bank (Mastruzzi et al., 2007). WGI consists of six dimensions: voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. The higher WGI is, the better the institutional environment of a host country is.

One should note that the marketization index and WGI have some similarities and differences. One of the similarities is that both of them measure institutional environment (Mastruzzi et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019). The progress of market intermediaries and legal framework (a sub-indicator of the marketization index), and rule of law and control of corruption (two sub-indicators of WGI) measure the impact of the law, a part of the formal institution. However, the marketization index and WGI still have many differences. First, the marketization index only measures the institutional environment in provinces of China (i.e., the home country), and WGI measures the institutional environment in host countries. Second, the marketization index only presents the institutional environment of a given province of China, while WGI refers to the institutional environment of a given country. The marketization index emphasizes the impact of government by the sub-indicator, the government-market relationship, which is relevant to the research question of our study. It also includes a sub-indicator unique to and important for China, the growth of a non-state-owned economy, because the state-owned economy has a controlled position in the Chinese economy (Szamosszegi and Kyle, 2011), and state-owned enterprises are more likely to be bribe payers in the bad institutional environment (Shaheer et al., 2019), so considering the government-market relationship is necessary and important in China. However, WGI just emphasizes the importance of political stability and the absence of violence/terrorism and government effectiveness, focusing on the safety and efficiency brought by governments, and ignores the firm-government relations.

Controls

Given prior literature (e.g., Shirodkar et al., 2022; C. Wang et al., 2022; Xavier et al., 2014), we control some variables related to the macroeconomic characteristics of host countries (GDP per capita, GDP growth, Gini coefficient, Population density, CPI) and firms’ characteristics (Size, Adjusted ROA, Tobin’s Q, Book-to-market ratio, Net profit growth, Patent stock, Concentration, Separation ratio, R&D employee ratio). We also control industry-fixed effects and year-fixed effects. All variables about macroeconomic characteristics take a natural logarithm. Size is calculated by the logarithm of the firm’s total assets. Adjusted ROA is measured by subtracting the industry average ROA from the firm’s ROA. Patent stock is calculated by the logarithm of the patent stock of the company in the research year. Concentration is measured by the proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder. Separation ratio means the degree of separation of ownership and management. The R&D employee ratio represents the proportion of R&D employees in total employees.

Estimation procedure

Since the dependent variable is the number of overseas subsidiaries in the single host country, which is nonnegative, integer-valued, and over-dispersed, we use a negative binomial model. The negative binomial model is more suitable for nonnegative, integer-valued data than ordinary least squares, and relaxes the Poisson model’s use conditions to solve the over-dispersed problem (Cameron and Trivedi, 1998). To test hypotheses, we design the following regression models:

where i indexes firms, k indexes host countries, and t indexes years. OFDIi,k,t represents dependent variable, namely the scale of OFDI under BRI, Politici,t represents independent variables, namely CEO political connections, Marketizationi,t represents institutional environment in the home region, WGIi,k,t represents institutional environment in the host country, Xi,k,t represents all control variables mentioned above, and industryi and yeart represent industry-fixed effects and year-fixed effects. ɛi,k,t, ϕi,k,t and φi,k,t are residuals.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients. The mean of the scale of OFDI is 1.280, indicating that firms participating in BRI have, on average, more than one overseas subsidiary in countries participating in BRI. The scale of OFDI is significantly and positively correlated to CEO political connections, the institutional environment in the home region (Marketization), Gini coefficient, Size, Adjusted ROA, Book-to-market ratio, Concentration and Separation Ratio, and negatively correlated to GDP per capita, Patent stock and R&D employee ratio, but with no significant relationship with the institutional environment in the host country (WGI), GDP growth, Population density, CPI, Tobin’s Q or Net profit growth. These correlations indicate that OFDI under BRI is affected by host countries’ macro characteristics and firm features. From perspectives of strategy and competition, statistics analysis shows that both firms’ profitability (e.g., Adjusted ROA and Book-to-market ratio) and strategy (e.g., Patent stock and R&D employee ratio) influence their competitive advantages, and market sizes in host countries (e.g., GDP per capita) influence the competitive intensity. Firms not only consider these factors related to countries but also take the developmental priorities of BRI members into account. For example, some members need Chinese help with logistics networks and facility connectivity. With priorities in these aspects, to make the flow of factor endowments of production smoother, Chinese firms invest in these members more. The mean of Politics is 0.144, revealing that most CEOs of these firms do not have political connections. Politics is significantly and negatively correlated to the institutional environment in the home region and the host country. We still need further regression analysis to test our hypotheses.

Results of regression

Table 2 reports results from negative binormal regressions predicting the scale of OFDI under BRI. Model 1 contains control variables and two moderator variables. Model 2 includes the main effect of CEO political connections. Models 3 and 4 include two interaction effects, respectively. Model 5 is the full model, which includes all main effects and interaction effects.

Model 2 tests the main effect of CEO political connections. Politics is significantly and positively correlated to the scale of OFDI under BRI (b = 0.0820, p = 0.023), supporting H1 that if a CEO has political connections, the firm has a larger scale of OFDI under BRI. Firms with CEO political connections can obtain more resources and government support for OFDI under BRI, so they have fewer transaction costs, lower political risks, and higher legitimacy (Frynas et al., 2006; Popli et al., 2022). Resources brought by CEOs provide more investment opportunities in countries along the Belt and Road, so their scale of OFDI under BRI is higher.

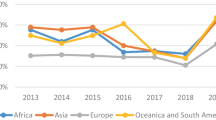

Model 3 tests the interaction between CEO political connections and the institutional environment in the home region. There is a negative and significant interaction between these two variables on the scale of OFDI under BRI (b = −0.1311, p = 0.002), and Fig. 2 also shows this result. This result supports H2 by showing that if the firm is located in a good institutional environment, the positive impact of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI is weakened. In the good institutional environment of the home region, firms obtain resources through market competition rather than personal networks or political power (Peng, 2003; Young et al., 2014), so CEO political connections are less useful in this condition.

Model 4 tests the interaction between CEO political connections and the institutional environment in the host country. There is a significant negative interaction between these two variables on the scale of OFDI under BRI (b = −0.1465, p = 0.000), supporting H3 that a good institutional environment of the host country weakens the positive effect of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI. Fig. 3 also shows this result. A good institutional environment in the host country provides a fair market competition environment that treats firms equally (Meyer et al., 2014), so foreign investors do not need to use CEO political connections to gain equal treatment, and benefits brought by CEO political connections are reduced.

Model 5 shows that when the main effect and interaction effects are included in the negative binormal regression model, the above results still hold.

Robustness checks

We conduct four robustness checks to corroborate our results. First, we use the one-year lag-independent variable to run models and check if the results still hold. Table 3 reports the results of this robustness check, indicating that all our hypotheses hold.

Second, we check whether our models have endogenous problems. We use the instrumental variable method to test our results. We use the mean of CEO political connections of companies in the industry (Industry politic mean) as the instrumental variable because it is correlated to a firm’s CEO political connections but exogenous to the scale of OFDI under BRI. Column (1) in Table 4 shows that CEO political connections in a firm are significantly and positively correlated to the industry average CEO political connections. Additionally, industry average CEO political connections are irrelative to the scale of OFDI under BRI; otherwise, firms in the same industry would have a similar scale of OFDI under BRI because of CEO political connections. Table 4 shows that all our hypotheses still hold.

Third, we deleted observations in 2020. Since the pandemic had a great impact on the economy in 2020, OFDI in 2020 may be different from that in other years, so we eliminated these observations. Table 5 shows that our hypotheses still hold.

Fourth, given there are many factors affecting the scale of ODFI under BRI, we consider more strategic and competitive factors. According to literature (Schüler-Zhou et al., 2012; de Alcântara et al., 2016; Ahmad et al., 2018; Clegg et al., 2018; Shuyan and Fabuš, 2019), we add seven factors whose data is available, i.e., multinational strategy (measured by the number of countries in which a firm invests worldwide), financial condition (measured by the amount of firm bank loan, indicating firm capability and competitive power), key provinces of BRI (meaning that whether the firm is located in provinces that the Chinese government particularly encourages to invest in countries along the Belt and Road), key industries of BRI (meaning that whether the firm is in industries that the Chinese government particularly encourages to invest in countries along the Belt and Road), export (measured by the natural logarithm of the host country’s exports), trade flows (measured by the natural logarithm of the host country’s exports and imports, indicating the degree of trade openness of the host country), trade openness (measured by dividing exports by imports). Table 6 shows the results, indicating that all our hypotheses still hold.

Further analysis

Extant literature shows that state-owned companies regard BRI as one of their political tasks, so they respond to BRI more actively (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2022; Liu and Wang, 2022). Therefore, we further analyze whether state ownership affects the relationship between CEO political connections and the scale of OFDI under BRI. We divide the sample into two groups: one is central-state-owned companies, and the other is non-central-state-owned companies. Table 7 reports the results. Only for non-central-state-owned companies, Politics has a significantly positive impact on the scale of OFDI under BRI (b = 0.0845, p = 0.037), and a good institutional environment in the home region and host country can weaken this positive impact (b = −0.1479, p = 0.002 and b = −0.1842, p = 0.000, respectively). There is no relationship between CEO political connections and the scale of OFDI under BRI for central-state-owned companies. Results indicate that central state ownership has a substitute role for CEO political connections. Only for non-central-state companies, CEO political connections are quite important.

Discussion

Anchored in the literature on resource dependence theory and resource-based view, this study provides empirical evidence about the impact of CEO political connections on the scale of OFDI under BRI.

Using firms investing along the Belt and Road as a sample, we find that CEO political connections have a positive impact on OFDI under BRI. This result is consistent with research conducted by Wu and Ang (2020) but is different from some other studies (Sun and Ai, 2020; Marquis and Qiao, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Shirodkar et al., 2022). The reason is that those studies do not take the specific context into account. Some scholars argue that political connections in the home country cause stakeholders’ unkindness in host countries because of political relations between countries, different cultures, etc. But when the BRI cooperation agreement is maintained between China and other countries, BRI represents a good relationship between China and host countries, the investment with the original intention of infrastructure construction is welcomed by stakeholders in host countries. With the consideration of both CEO domestic political connections and the relationship between China and host countries, our study concludes that CEO political connections can promote firm OFDI.

Moreover, the results highlight the moderating effect of the institutional environment and show that if firms are in a good institutional environment, the positive impact of CEO political connections weakens. It is consistent with many studies (Peng, 2003; Meyer et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015), because a good institutional environment supports firms to gain opportunities through fair market competition rather than CEO personal connections or influences. Therefore, the effect of CEO political connections weakens in the good institutional environment of both regions in China and host countries.

Implications for research

Our study has several theoretical contributions. First, our study supplements the influencing factors of OFDI under BRI and its boundary conditions. As BRI is a geopolitical policy, assessing how government-related factors affect investment in countries along the Belt and Road is important. This study finds a new factor, i.e., CEO political connections, to contribute to related literature. Although extant literature has investigated the relationship between CEO political connections and OFDI, results are mixed (Sun and Ai, 2020; Wu and Ang, 2020; Marquis and Qiao, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Shirodkar et al., 2022), so we clear this controversial point in the background of BRI.

Second, our study contributes to the literature on the non-market strategy of MNEs. In this study, we regard the OFDI under BRI as not purely for economic purposes but also for some non-economic purposes (Dorobantu et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2022), and focus on firm non-market strategy implementation through CEO political connections, not firm direct behavior. Therefore, we enrich the understanding of how firm non-market strategy affects a mixture of economic and non-economic international expansion.

Third, our study is beneficial to research firm OFDI in the emerging market. We analyze firms’ OFDI, which takes advantage of CEO political connections. Prior studies mainly analyze the influencing factors or consequences in the context of purely economic competition (Ahmad et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2021; Gao, 2023), but this study provides a new perspective, i.e., taking government policies into account. In the context of geopolitical policies, we find another factor affecting OFDI and its boundary conditions.

Implications for practice

Our study also has practical contributions. For OFDI under BRI, firms need to have CEO political connections, especially for non-central-state-owned companies. CEO political connections can bring firms resources, especially a deeper understanding of BRI, and thus firms can seize this opportunity brought by related policies. But firms should also consider the institutional environment in the home region and host country. If the institutional environment in the home region and host country is good, CEO political connections are less useful.

Limitations and future research

Although this study investigates the impact of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI and its boundary conditions, there are still limitations that need to be improved and deepened in further research.

First, this study only considers the impact of CEO political connections in the home country and does not deeply analyze inter-country contemporary political and economic tendencies of certain BRI members. In future research, we can consider the impact of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI, when countries pull out of the BRI, or countries optimize their role and cooperation among BRI members.

Second, in this study, we focus on how CEO political connections affect OFDI under BRI. Although we control many other factors, it is still worth further research. In future research, we can investigate more potential factors influencing OFDI under BRI, such as the absorptive potential of the host business entity, and the degree of competitive industry environment of the host country.

Third, our study emphasizes the benefits brought by CEO political connections, i.e., the CEO uses the political connections to promote OFDI under BRI. However, according to agency theory, it is likely that the CEO’s decision to OFDI deviates from the interests of shareholders because the CEO's political connections are the CEO’s personal network and resources, not the firm’s or shareholders’. Therefore, in future research, we can consider this, and analyze the impact of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI when the CEO hurts shareholders’ interests.

Fourth, our study emphasizes the benefit brought by CEO connections, i.e., CEO connections promote firm OFDI under BRI, but there is still a possibility that CEO connections may bring negative effects, such as lobbying, campaign contributions, and bribery, and these negative effects are also likely to affect firm OFDI under BRI. However, extant research usually studies these negative effects through scales and cases (Morgan, 1993; Shaheer et al., 2019; Earl et al., 2022), but in our study, it is hard to do this for all listed companies in China. Therefore, in future research, we will try to find other suitable research methods to further consider how the negative effects of CEO political connections influence firm OFDI under BRI.

Conclusions

Since the Chinese government proposed the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, firms in China have been actively investing abroad. This study investigates how CEO political connections affect the scale of firm OFDI under BRI, and finds that CEO political connections have a positive impact on OFDI under BRI. However, it is not always useful. If firms are located in regions with good institutional environments in China or invest in host countries with good institutional environments, the positive effect of CEO political connections on OFDI under BRI weakens.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are provided as supplementary files.

References

Ahammad MF, Tarba SY, Frynas JG, Scola A (2017) Integration of non-market and market activities in cross-border mergers and acquisitions: non-market and market activities in M&As. Br J Manag 28:629–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12228

Ahmad F, Draz MU, Yang S-C (2018) What drives OFDI? Comparative evidence from ASEAN and selected Asian economies. J Chin Econ Foreign Trade Stud 11:15–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCEFTS-03-2017-0010

Bai T, Chen S, Xu Y (2021) Formal and informal influences of the state on OFDI of hybrid state-owned enterprises in China. Int Bus Rev 30:101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101864

Baron DP (1995) Integrated strategy: market and nonmarket components. Calif Manag Rev 37:47–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165788

Baron DP, Diermeier D (2007) Strategic activism and nonmarket strategy. J Econ Manag Strategy 16:599–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2007.00152.x

Bevan A, Estrin S, Meyer K (2004) Foreign investment location and institutional development in transition economies. Int Bus Rev 13:43–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2003.05.005

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (1998) Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chen CC, Chen X-P, Huang S (2013) Chinese guanxi_ an integrative review and new directions for future research. Manag Organ Rev 9:167–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/more.12010

Clegg LJ, Voss H, Tardios JA (2018) The autocratic advantage: internationalization of state-owned multinationals. J World Bus 53:668–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2018.03.009

Cuervo-Cazurra A, Duran P, Arregle J-L, van Essen M (2022) Host country politics and internationalization: a meta-analytic review. J Manag Stud. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12853

de Alcântara JN, Paiva CMN, Bruhn NCP et al. (2016) Brazilian OFDI determinants. Lat Am Bus Rev 17:177–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/10978526.2016.1209080

De Beule F, Zhang H (2022) The impact of government policy on Chinese investment locations: an analysis of the Belt and Road policy announcement, host-country agreement, and sentiment. J Int Bus Policy 5:194–217. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-021-00129-2

Dorobantu S, Kaul A, Zelner B (2017) Nonmarket strategy research through the lens of new institutional economics: an integrative review and future directions. Strateg Manag J 38:114–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2590

Dumitrescu GC (2015) Central and Eastern European countries focus on the Silk Road Economic Belt. Glob Econ Obs 3:186–197

Earl A, Michailova S, Stringer C (2022) How Russian MNEs navigate institutional complexity at home. Int J Emerg Markets https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-01-2021-0140

Frynas JG, Mellahi K, Pigman GA (2006) First mover advantages in international business and firm-specific political resources. Strateg Manag J 27:321–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.519

Gao GY, Murray JY, Kotabe M, Lu J (2010) A “strategy tripod” perspective on export behaviors: evidence from domestic and foreign firms based in an emerging economy. J Int Bus Stud 41:377–396. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.27

Gao R (2023) Inward FDI spillovers and emerging multinationals’ outward FDI in two directions. Asia Pac J Manag 40:265–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09788-4

García-Canal E, Guillén MF (2008) Risk and the strategy of foreign location choice in regulated industries. Strateg Manag J 29:1097–1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.692

Globerman S, Shapiro D (2002) Global foreign direct investment flows: the role of governance infrastructure. World Dev 30:1899–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00110-9

Henisz WJ (2000) The institutional environment for multinational investment. J Law Econ Organ 16:334–364

Hillman AJ (2005) Politicians on the board of directors: do connections affect the bottom line? J Manag 31:464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304272187

Hillman AJ, Withers MC, Collins BJ (2009) Resource dependence theory: a review. J Manag 35:1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469

Holburn GLF, Vanden Bergh RG (2014) Integrated market and nonmarket strategies: political campaign contributions around merger and acquisition events in the energy sector: Research Notes and Commentaries. Strateg Manag J 35:450–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2096

Holcombe RG (2010) Review of violence and social orders: a conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Public Choice 144:389–392

Lester RH, Hillman A, Zardkoohi A, Cannella AA (2008) Former government officials as outside directors: the role of human and social capital. Acad Manag J 51:999–1013

Lewin AY, Witt MA (2022) China’s Belt and Road Initiative and international business: the overlooked centrality of politics. J Int Bus Policy 5:266–275. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-022-00135-y

Li H, Zhang Y (2007) The role of managers’ political networking and functional experience in new venture performance: evidence from China’s transition economy. Strateg Manag J 28:791–804

Li J, Meyer KE, Zhang H, Ding Y (2018) Diplomatic and corporate networks: bridges to foreign locations. J Int Bus Stud 49:659–683. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0098-4

Li J, Qian G, Zhou KZ et al. (2022) Belt and Road Initiative, globalization and institutional changes: implications for firms in Asia. Asia Pac J Manag 39:843–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09770-0

Liu B, Wang Q (2022) Speed of China’s OFDIs to the Belt and Road Initiative destinations: state equity, industry competition, and the moderating effects of the policy. J Int Bus Policy 5:218–235. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-021-00125-6

Luise C, Buckley PJ, Voss H et al. (2022) A bargaining and property rights perspective on the Belt and Road Initiative: cases from the Italian port system. J Int Bus Policy 5:172–193. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-021-00122-9

Marquis C, Qiao K (2020) Waking from Mao’s Dream: communist ideological imprinting and the internationalization of entrepreneurial ventures in China. Adm Sci Q 65:795–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839218792837

Mastruzzi M, Kraay A, Kaufmann D (2007) Governance matters VI: aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2006. The World Bank

Meyer KE, Ding Y, Li J, Zhang H (2014) Overcoming distrust: how state-owned enterprises adapt their foreign entries to institutional pressures abroad. J Int Bus Stud 45:1005–1028. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.15

Morgan RB (1993) Self- and co-worker perceptions of ethics and their relationships to leadership and salary. Acad Manag J 36:200–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/256519

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance, 1st edn. Cambridge University Press

North DC, Wallis JJ, Weingast BR (2009) Violence and social orders: a conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history, 1st edn. Cambridge University Press

Park SH, Luo Y (2001) Guanxi and organizational dynamics: organizational networking in Chinese firms. Strateg Manag J 22:455–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.167

Peng MW (2003) Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Acad Manag Rev 28:275. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040713

Peng MW, Luo Y (2000) Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: the nature of a micro-macro link. Acad Manag J 43:486–501. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556406

Popli M, Ahsan FM, Mukherjee D (2022) Upper echelons and firm internationalization: a critical review and future directions. J Bus Res 152:505–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.07.048

Rothstein B, Teorell J (2008) What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance 21:165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x

Schüler-Zhou Y, Schüller M, Brod M (2012) Push and pull factors for Chinese OFDI in Europe. In: Alon I, Fetscherin M, Gugler P (eds) Chinese international investments. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp 157–174

Shaheer N, Yi J, Li S, Chen L (2019) State-owned enterprises as bribe payers: the role of institutional environment. J Bus Ethics 159:221–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3768-z

Shi W (Stone), Markóczy L, Stan CV(2014) The continuing importance of political ties in China AMP 28:57–75. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2011.0153

Shirodkar V, Batsakis G, Konara P, Mohr A (2022) Disentangling the effects of domestic corporate political activity and political connections on firms’ internationalisation: evidence from US retail MNEs. Int Bus Rev 31:101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101889

Shuyan L, Fabuš M (2019) Study on the spatial distribution of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment in EU and its influencing factors. Entrep Sustain Issues 6:1280–1296. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.6.3(16)

Su Z, Fung H-G (2013) Political connections and firm performance in Chinese companies. Pac Econ Rev 18:283–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12025

Sun SL, Peng MW, Lee RP, Tan W (2015) Institutional open access at home and outward internationalization. J World Bus 50:234–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.04.003

Sun Z, Ai Q (2020) Too much reciprocity? The invisible impact of home political connections on the value creation of Chinese multinationals. Chin Manag Stud 14:473–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-12-2018-0788

Szamosszegi A, Kyle C (2011) An analysis of state‐owned enterprises and state capitalism in China. U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, Washington, DC

Tang Q, Gu FF, Xie E, Wu Z (2020) Exploratory and exploitative OFDI from emerging markets: Impacts on firm performance. Int Bus Rev 29:101661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101661

Wang C, Piperopoulos P, Chen S et al. (2022) Outward FDI and innovation performance of Chinese firms: why can home-grown political ties be a liability? J World Bus 57:101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101306

Wang X, Fan G, Zhu H (2007) Marketisation in China: progress and contribution to growth. In: Garnaut R, Song L (eds) China—linking markets for growth. ANU Press, pp. 30–44

Wang X, Feng M, Xu X (2019) Political connections of independent directors and firm internationalization: an empirical study of Chinese listed firms. Pac-Basin Financ J 58:101205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2019.101205

Wang Y, Chou C-C (2020) Prioritizing China’s public policy options in developing logistics infrastructure under the Belt and Road Initiative. Marit Econ Logist 22:293–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-019-00143-5

Williamson OE (1991) Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Adm Sci Q 36:269. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393356

Wu J, Ang SH (2020) Network complementaries in the international expansion of emerging market firms. J World Bus 55:101045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101045

Xavier WG, Bandeira-de-Mello R, Marcon R (2014) Institutional environment and Business Groups’ resilience in Brazil. J Bus Res 67:900–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.07.009

Xu D, Zhou KZ, Du F (2019) Deviant versus aspirational risk taking: the effects of performance feedback on bribery expenditure and R&D intensity. AMJ 62:1226–1251. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0749

Yang G, Huang X, Huang J, Chen H (2020) Assessment of the effects of infrastructure investment under the belt and road initiative. China Econ Rev 60:101418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101418

Yi J, Chen L, Meng S et al (2022) Bribe payments and state ownership: the impact of state ownership on bribery propensity and intensity. Bus Soc. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221124860

Young MN, Tsai T, Wang X et al. (2014) Strategy in emerging economies and the theory of the firm. Asia Pac J Manag 31:331–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-014-9373-0

Zhang C, Xiao C (2022) China’s infrastructure diplomacy in the Mediterranean region under the Belt And Road Initiative: challenges ahead? Mediterr Politics 0:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2022.2035135

Zhang M, Tao Q, Shen F, Li Z (2022) Social capital and CEO involuntary turnover. Int Rev Econ Financ 78:338–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.11.017

Zhang Z, Xue J, Qi B (2021) Ties, status, and internationalization of Chinese private firms. Chin Manag Stud. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-03-2020-0107

Zheng W, Ang SH, Singh K (2022) The interface of market and nonmarket strategies: Political ties and strategic competitive actions. J World Bus 57:101345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101345

Zhou KZ, Gao GY, Zhao H (2017) State ownership and firm innovation in China: an integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Adm Sci Q 62:375–404

Zhu H, Hui KN-C, Gong Y (2022) Uncovering the nonmarket side of internationalization: the Belt and Road Initiative and Chinese firms’ CSR reporting quality. Asia Pac J Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09835-8

Zou L, Shen JH, Zhang J, Lee C-C (2022) What is the rationale behind China’s infrastructure investment under the Belt and Road Initiative. J Econ Surv 36:605–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12427

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant no. 72072132.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shouming Chen and Yueqi Wang contributed to the study design. Yueqi Wanag contributed to data collection, methodology, software, interpretation of findings, and writing—original draft preparation. Shouming Chen supervised and acquired funding. Peien Chen contributed to writing—review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Chen, S. & Chen, P. CEO political connections and OFDI of Chinese firms under the Belt and Road Initiative. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1124 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03666-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03666-2