Abstract

Working-time reduction emerges as a promising measure for fostering a well-being economy, as it allows to reconsider time allocation between paid labour and other activities, potentially improving human and environmental well-being. This study investigates the motives for and planned time use of additional leave in the context of a flexible benefits plan, a specific form of working-time reduction that is increasingly popular among employees and employers. Despite its popularity, little is known about the rationale behind this choice and its potential to create socio-environmental benefits. Data were collected from a Belgian media company in 2022 using a mixed-methods approach, comprising a survey (N = 241) and semi-structured interviews (N = 13). The findings reveal that a mix of motives matters for choosing additional leave, including push, pull, personal and contextual factors, as well as the specifics of the flexible benefits plan. While the desire for more leisure emerges as a primary driver, difficulties in taking up the standard amount of leave present a key barrier. Employees plan to use their extra leave for diverse activities, mainly personal and social activities, household tasks, travel, and ad-hoc pursuits. However, preferences vary based on parental status, with couples having children primarily intending to use the leave for caregiving responsibilities. Notably, the primary activities for intended time use align with increased well-being and have relatively low environmental impacts, although positive effects may be partially offset for well-being (such as when paid work is replaced with unpaid care or household work) or for the environment (such as when spending the extra leave on environmentally intensive (travel) activities). These findings tentatively suggest that choosing additional leave in flexible benefits plans could contribute to a well-being economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The well-being economy—an economy in which human and ecological well-being are prioritised rather than material growth—is emerging as a fresh paradigm for policy development (Fioramonti et al. 2022). This is especially so given the outdatedness of certain assumptions in mainstream economics and given the urgency of various contemporary crises (Coscieme et al. 2019; Llena-Nozal et al. 2019). The quest for such an economy requires to design and evaluate measures that can contribute positively to both human well-being and environmental sustainability.

In this respect, a measure worth investigating is working-time reduction (WTR), which is a reduction in the total amount of paid working time over the life course (Pullinger, 2014). Within the well-being economy literature, working-time reduction has explicitly been cited as a policy option because it enables a crucial aspect of such an economy: enhancing work–life balance and quality of work (Fioramonti et al. 2022). Moreover, particular shorter workweek projects have been explicitly mentioned in the context of moving towards a well-being economy, including the cases of Finland (Fioramonti et al. 2022), Scotland (Statham and Smith, 2021), and Iceland (Hayden and Dasilva, 2022). Working-time reduction owes its increasing popularity to its many potential benefits across various domains, including well-being and the environment—two primary domains of interest for a well-being economy—as well as employment and gender equality (De Spiegelaere and Piasna, 2017; Hanbury et al. 2023; Kallis et al. 2013; Pullinger, 2014; Skidelsky, 2019).

In terms of well-being, happiness economics suggests that reducing consumption or income—which may follow from reducing working time—does not necessarily harm well-being: the conventional finding that subjective well-being is strictly positively correlated with consumption has been proven to be outdated (Diener et al. 1993; Easterlin, 2015; Veenhoven, 1991). Moreover, the growing body of literature on subjective well-being sheds light on other important drivers. Amongst others, well-being has been investigated by time-use researchers (Gershuny, 2011; Krueger, 2009). It is often found that the way in which individuals allocate their time has profound implications for well-being, for example, through leisure activities (Brajša-Žganec et al. 2011; Robinson and Martin, 2008), caregiving activities (Freedman et al. 2019; Urwin et al. 2023) or employment status (Hoang and Knabe, 2021).

Regarding environmental impacts, reduced working time can yield benefits via two main pathways: by reducing income levels and hence consumption levels—the “income” effect—and by promoting less environmentally intensive uses of the additional non-working time—the “time use” effect. A systematic literature review by Antal et al. (2020) revealed that the majority of studies find shorter working time to reduce environmental pressures primarily due to the income effect, that is, by assuming a corresponding decrease in income. While the income effect is clear, the time use effect remains contentious and may even be negative due to rebound effects, underscoring the need to examine how people spend their time differently—when reducing working hours—to assess the environmental impact.

The potential dual advantage for socio-environmental outcomes positions working-time reduction as a relevant strategy in cultivating a well-being economy. However, the ultimate set of benefits that can be realised will hinge upon several factors. First, the type of working-time reduction is a key determinant for potential benefits. A reduction in paid working time can vary across a series of dimensions and, therefore, take on diverse forms. For instance, a distinction can be made between employees who individually choose to reduce working hours (i.e., opting for part-time work) and those who participate in a collectively organised WTR scheme (such as the companies that take part in WTR trials that have gained popularity since the COVID-19 pandemic and that are organised in multiple countries). Furthermore, working hours can be significantly reduced (e.g., when transitioning from a 38-h workweek to 32 or 30 h) or only marginally (e.g., an increased number of vacation days), and it can be accompanied by full salary retention or (partially) proportional salary loss. The choices regarding the different dimensions play a major role in the ability to create benefits in diverse domains. Second, the potential benefits depend on how individuals reallocate their time to alternative activities instead of working. This is particularly true for impacts on well-being (as supported by a substantial body of literature linking time use to well-being) and the environment (given the potential (rebound) effects of time use).

One specific type of working-time reduction worth investigating is the choice for additional leave that employees make within the framework of flexible benefits plans (also known as cafeteria systems). A flexible benefits plan is a flexible compensation system that enables employees to select the benefits they want within a number of categories—such as mobility, financial products, or work–life balance—ensuring that their final benefits package aligns better with their personal needs and preferences (Vandekerckhove and Lenaerts, 2022). Flexible benefits plans originated in the United States during the 1980s, became popular in the Netherlands during the 1990s, and have firmly established themselves as a prevalent practice in Belgian companies over the last two decades (Bloom and Trahan, 1986; Delsen et al. 2006). A key driver of their popularity lies in their tax efficiency: they enable the conversion of part of the gross salary into net salary benefits, which results in lower employer taxes compared to providing cash bonuses. Consequently, the tax advantages of such plans reduce the tax burden on employers and shift some of the fiscal impact to the state or welfare system. This is particularly noteworthy in Belgium, which has one of the largest labour tax wedges in the OECD (OECD, 2023). An employee’s choice for additional leave in a flexible benefits plan can be seen as an individual WTR choice within a scheme that is collectively available to all employees in their company. Moreover, it can be considered as working-time reduction at the margin since it concerns additional leave days (rather than a more structural reduction of daily or weekly working time) and because the number of days to be chosen is usually limited to a maximum per year. Finally, the financial impact of this choice is rather limited as it usually does not affect an employee’s salary directly, although usually, it does entail a (financially optimal) conversion of the cash bonus. Despite the potential benefits and rising popularity of additional leave options, with employers ever more incorporating them into compensation packages and employees showing heightened demand for leisure, especially post-COVID-19 (MetLife, 2023), studies examining these choices, especially within the context of flexible benefits plans, remain scarce.

In this study, we conduct a comprehensive analysis of motives for and planned time use of additional leave, chosen by employees within the context of a flexible benefits plan. We aim to tackle the following research questions: first, what motives play a role in the choice for additional leave (RQ1)? Second, how do employees who choose additional leave plan to use the additional non-working time (RQ2)? The second research question is further divided into two sub-questions: how do leave-choosing employees plan to use the extra time in general (RQ2a), and (how) can leave-choosing employees be clustered into distinct groups based on their planned time use (RQ2b)? By providing an in-depth investigation of additional leave preferences, this research offers valuable insights into the rationale behind an increasingly popular option and contributes to a relatively underexplored field of literature. Moreover, there are reasons to assume that motives and intended time use can translate into actual time use and behaviour, which in turn can affect an individual’s well-being and environmental impact. Despite the uncertain and untestable nature of this assumption in our study, exploring motives and planned time use is pertinent to gain preliminary insights into the potential socio-environmental impacts of this choice, thereby adding to the findings from other authors who explored the potential to create well-being and environmental benefits through reducing working time (Buhl and Acosta, 2016; Neubert et al. 2022; Persson et al. 2022) or engaging in particular activities (Isham et al. 2019). However, these socio-environmental insights should be interpreted with caution since our data do not allow for a rigorous quantification of such effects. We collected both survey data (N = 241) and interview data (N = 13) in a Belgian company operating in the media sector and applied a mixed-methods approach comprising both quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques. Although various authors have argued to employ such a mixed-methods approach for analysing working time preferences, its application in practice is limited (Campbell and van Wanrooy, 2013; Gerold and Nocker, 2018) and—to the best of our knowledge—non-existent in the context of flexible benefits plans (Fagan, 2001; Reynolds and Aletraris, 2006; Van Wanrooy and Wilson, 2006).

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section “Literature analysis” discusses existing literature regarding motives and time use. The case study, data gathering, and data analysis are discussed in the section “Methods”, after which results are presented and discussed in the sections “Results” and “Discussion”. Finally, the section “Conclusion” concludes.

Literature analysis

Two relevant bodies of literature are investigated concerning motives (RQ1) and time use (RQ2). First, the literature specifically on flexible benefits plans is considered. However, this strand of literature is relatively limited, outdated, and primarily focused on aspects beyond employee-level motives and time use—such as HRM, employer-level insights, and determinants of choices made in cafeteria systems. Therefore, we will primarily draw from the broader literature on working-time reduction, which offers a more comprehensive discussion of motives and time use.

Motives

The WTR literature has predominantly explored motives for (not) reducing working hours (RQ1) through qualitative methods, often employing interviews with individuals who have recently chosen to voluntarily and significantly decrease their paid working time. This investigation occurs predominantly at the individual level, examining choices such as part-time work (Balderson et al. 2021; Hanbury et al. 2019; Lindsay et al. 2020), or at the company level, within policies that allow employees to select between a wage increase or additional leisure time (Gerold and Nocker, 2018). Additionally, Hiemer and Andresen (2019) qualitatively explored reasons for overemployment (i.e., stated rather than revealed preferences), while Björk et al. (2020) and Persson et al. (2022) quantitatively probed motivations for working less. All motives can be broadly grouped into one of three categoriesFootnote 1. First, push drivers encompass negative aspects of work that increase employees’ desire to reduce the amount of working time. Examples include work intensity and lack of control over worktime organisation. Second, pull drivers relate to employees’ desire for more leisure time, either in general or to be spent with particular people—such as friends and family or oneself—or on specific activities—such as leisure activities or unpaid work. Third, barriers include reasons that either reduce or impede employees’ desire to reduce working time. These barriers include both intrinsic motivations, such as when employees enjoy their work so much that they prefer to dedicate a minimal amount of time to it, as well as external obstacles, such as when employees desire to reduce working time but feel hindered from doing so because of occupational demands, perceived norms or financial constraints. While pull drivers focus on improving personal well-being, push drivers indicate efforts to tackle shortcomings in professional well-being. From a well-being perspective, external barriers are particularly concerning as they suggest professional well-being issues that employees find challenging to address. Moving to an environmental perspective, environmental motives are seldom explicitly cited as primary motivation by so-called “downshifters”, individuals who consciously reduce paid working time, income, and aggregate consumption (Balderson et al. 2021; Frayne, 2015; Gerold and Nocker, 2018; Kennedy et al. 2013; Lindsay et al. 2020). However, such motives are found in specific niche movements like “voluntary simplifiers”, that is, individuals who resist a high-consumption lifestyle and opt instead for a lower-consumption but higher-quality way of life (Alexander and Ussher, 2012).

In the literature on flexible benefits plans, van den Brekel and Tijdens (2000) investigated motives of preferences for a series of choice options, including the option for additional leave in exchange for a salary reduction. Possible reasons for selecting this option ranged from the desire for extra leisure time to pursuing further education or (unforeseen) care responsibilities for sick family members. Conversely, reasons for not choosing this option included financial constraints, occupational pressures, or simply lacking the need or desire for additional leisure time. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution since stated preferences—i.e., claimed choices in hypothetical scenarios—rather than revealed preferences—i.e., actually observed choices—were studied. Additionally, the research employed a questionnaire format featuring a pre-determined list of potential motives, limiting the exploration of free-text answers.

Time use

To the best of our knowledge, time use changes in case of reduced working hours (RQ2) have not explicitly been analysed in the literature on flexible benefits plans. In the broader WTR literature, time use has been measured in various formats (quantitative vs. qualitative) and levels of detail, serving various research purposes. In this regard, the WTR literature investigating time use can be categorised into two groups.

On the one hand, several authors have specifically studied changes in time spent on different activities after the implementation of a structural reduction in working time. They have employed the time use data for assessing micro-level well-being indicators—such as work stress, work–life balance, and work-to-life conflict—or evaluating the policy’s broader, macro-level impacts on well-being. For instance, Mullens et al. (2020) employed a comprehensive approach, combining detailed quantitative time-use diaries (repeated measurements for a broad range of activities) with qualitative in-depth and focus interviews, to analyse the effects of a collective reduction of the workweek from 36 to 30 h in a Belgian women’s organisation in 2019. Amongst others, they investigated wishes, expectations, and actual changes in time use following the collective WTR policy (Mullens and Glorieux, 2024). Additionally, Hayden (2006) investigated how the 35-h workweek in France in 2000 affected time use, quality of life, and the economy by drawing on survey, economic, and interview data.

On the other hand, scholars have employed changes in time use as a particular method to estimate the environmental impacts of shorter working hours. Two perspectives and associated types of data sources for consumption have been used to estimate income and time use (rebound) effects at the micro-level, either quantitatively or qualitatively: a purchasing power perspective (based on expenditure data for categories) or a time use perspective (based on time use data for activities). The latter approach aims to assess the impact of reduced working hours on the environment by analysing changes in time allocation for a series of activities, each having a specific estimated environmental footprint. While the ultimate aim of these studies was to assess changes in environmental impact from shorter working hours, some of these studies can equally provide valuable insights into how time allocation shifts with reduced working hours, either through a purchasing power perspective (Devetter and Rousseau, 2011; Lindsay et al. 2020) or a time use perspective (Buhl and Acosta, 2016; Hanbury et al. 2019; Nässén et al. 2009; Nässén and Larsson, 2015; Persson et al. 2022).

Pooling the findings from both groups of authors described above, we first discuss what activities are more or less likely to change with a reduction in paid working time (relevant for RQ2a). The most significant activity changes were observed for time spent on domestic work, childcare (in the presence of children), and personal care (sleep and rest), while moderate changes were found for time spent on personal leisure (primarily hobbies, sports, and media), social leisure, education, and voluntary work. Findings regarding transport diverge across papers, from low or even negative effects of working-time reduction on daily transport (Devetter and Rousseau, 2011; Mullens et al. 2020; Nässén et al. 2009; Nässén and Larsson, 2015) to positive effects on time spent on travel and holiday patterns (Hayden, 2006; Lindsay et al. 2020; Persson et al. 2022). The few authors that explicitly investigated the impact on food consumption found that shorter working hours had a significant effect, which manifested amongst others in an increased preference for home-cooked and healthier meals, and a decline in the number of takeaway meals and eating out (Devetter and Rousseau, 2011; Lindsay et al. 2020). Second, all the studies described above were reviewed for subgroup comparisons regarding changes in time use (relevant for RQ2b). This was explicitly investigated by Mullens et al. (2020), who found that revealed time use changes differed depending on the family composition, and Persson et al. (2022), who found no significant differences in stated time use changes between different socioeconomic categories. However, some authors investigated subgroup differences with respect to other outcomes, including Hayden (2006) (who found that the extent to which workers were able to value their extra free time varied according to gender, income, and work schedule predictability), Nässén et al. (2009) (who investigated how the environmental effects differed based on income), Persson et al. (2022) (who analysed how motivations and socioecological outcomes varied across socioeconomic groups) and Buhl and Acosta (2016) (who investigated how time use rebound effects differed based on sufficient lifestyles and childcare).

Methods

Case study

We collected data from a Belgian media company operating across Europe. Since 2017, the company has offered a flexible benefits plan allowing employees to convert their cash year-end bonus into one or multiple benefits to be chosen from five categories: finance, mobility, multimedia, health, and well-being. The last category includes the additional leave benefit, which is limited to a maximum of ten days taking into account any transferred additional leave from the previous year. Employees are well informed by HR-staff about the plan’s financial advantage in general (i.e., a 15% increase in net value can be created by opting for benefits instead of a cash bonus), as well as the relative financial attractiveness of each benefit specifically (i.e., how much more net value can be created by choosing a particular benefit). Choices are made annually over a 2-week period in the final quarter and can not be altered thereafter. Employees can choose a combination of benefits up to the total value of their year-end bonus, with any remaining amount being paid out in cash at a less favourable tax rate.

Data gathering

Quantitative data

Two types of quantitative data were gathered and matched. First, administrative data were obtained in January 2022 from a company-level database for all Belgian-based employees (N = 1040). These records included basic socio-demographics (sex and age), job-related characteristics (seniority), and choices made for the flexible benefits plan of 2022 (choices were made in November 2021). Second, an online survey was conducted in March 2022 via Qualtrics to collect additional data pertinent to addressing the research questions. Following a brief introduction and request for informed consent, the survey consisted of four parts.

The first part of the survey included a series of individual and household socio-demographic characteristics (relationship status, number and age of children living in the household, education, and income).

The second part of the survey contained worktime characteristics (contractual number of weekly working hours, number of standard leave days, and number of additional leave days chosen in the flexible benefits plan). Respondents who indicated to have chosen at least one additional leave day were presented with an additional series of questions about the planned time used for the additional non-working time. Respondents had to indicate how likely they were to spend more, less or about the same amount of time on 18 specific activities (using a 5-point Likert scale), taking into account the additional non-working time created by the choice for additional leave. The selection of activities was based on the Belgian Time Use Survey (TUS) of 2013, which is a survey on how Belgians organise their time (Statbel, 2013). From the comprehensive TUS list, which is organised into main- and subcategories, activities were either copied (often with subcategories merged to limit the total number of activities), adjusted or omitted, resulting in a total of 12 activities. Moreover, 6 activities related to travel and food were additionally incorporated for environmental impact estimation purposesFootnote 2. The final list of activities is presented in Table 1.

In the third part of the survey, a series of job-related motives (push drivers, pull drivers, and barriers) and job evaluations were investigated. As a push driver, work intensity was measured. Regarding pull drivers, the degree to which respondents experience sufficient non-working time was measured for 10 specific activities that were selected based on the WTR literature on pull drivers (see the section “Motives”). For each activity, respondents had to indicate to what extent they felt they had sufficient time for it using a 5-point Likert scale. The list of activities is presented in Table 2. As barriers, we included the ideal worker norm (IWN), i.e., the expectation that employees prioritise work responsibilities over any external commitments (Bernhardt and Buenning, 2020), as well as two barrier items relating to the evaluation of the standard amount of leave days: “My number of standard leave days is more than sufficient for me” and “I find it difficult to use all of my standard leave on an annual basis”, each measured on a 5-point Likert scale of agreement. Finally, work–life balance was measured.Footnote 3

In the fourth and final part of the survey, a battery of personal characteristics was measured. This included materialismFootnote 4 and the following environment-related characteristics: importance of protecting the environment, number of environmental actions, and travel behaviourFootnote 5. The survey concluded with a question assessing respondents’ willingness to engage in a follow-up in-depth interview, providing them with the opportunity to elaborate in greater detail on their choice for additional leave.

All Belgian-based employees working in the company (N = 1040) received an invitation via mail to participate in the survey. The mail emphasised the importance of participation for both research- and HR-insights, and included an information letter that outlined the study’s purpose (examining motivations and usage of additional leave days) and the type of data collected (socio-demographic, job, and personal characteristics). The letter also informed employees of their rights, emphasising that participation was voluntary, data would be linked with existing company records, handled confidentially according to GDPR, and stored for at least five years solely for research purposes. A reminder was sent after two weeks. By the survey’s close (three weeks after the initial invitation), 337 employees had responded, resulting in a 32% response rate. After matching administrative data to survey data and conducting data cleaningFootnote 6, the final sample size was reduced to 241 respondents. The sample comprises 53.1% female and 46.9% male respondents with a mean age of 44.0 years, of whom 33.6% work part-time. Compared to the total workforce of the company, the sample is overrepresented by female employees (only 43.1% of all employees are female; p = 0.005) and part-time workers (only 27.3% of all employees work part-time; p = 0.028), but is representative in terms of age (mean age of 43.7 years; p = 0.700). Additional descriptive statistics for the sample are presented in Table 3. Regarding choices within the flexible benefits plan, 44.8% of respondents (N = 108) chose at least one additional leave day, with 10 days (24.5%) and 5 days (9.5%) being the most popular options. This deviates from the total workforce where only 34.7% made this choice (p = 0.000) and suggests a potential self-selection bias that should be considered when interpreting results.

Qualitative data

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in July and August 2022. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling: all survey respondents (i) who had expressed their openness towards a follow-up interview and (ii) who had an outspoken preference for additional leave (i.e., who had chosen at least 5 additional leave days within the flexible benefits plan) received an invitation for participation (N = 21). The final sample consisted of 13 participants which is in line with Guest et al.'s (2006) recommended number of interviews. Key characteristics of interviewees (aggregated across the sample) are presented in Table 4. At the beginning of the interview, participants were asked to read and sign an informed consent. Interviews were structured according to an interview guideline. The topic list included three main subjects to be discussed: motives (relevant for RQ1), planned time use (relevant for RQ2), and openness for part-time work (i.e., one other specific form of working-time reduction), each of which was scrutinised into greater detail using a question protocol. All interviews were conducted in Dutch, online (via MS Teams) and recorded, and lasted between 16 and 36 min. Videotapes of the interviews were transcribed afterward for further analysis.

Data analysis

We performed several quantitative analyses (based on the merged dataset), including descriptives and cluster analyses, and one qualitative analysis (based on the interviews).

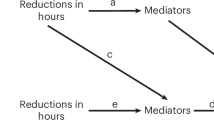

Cluster analysis based on motives

To explore the motives at play in the choice for additional leave (RQ1), we examined seven potential motives organised into three groups: push drivers (work intensity), pull drivers (desire for more time for specific activities, measured using three factors of experienced time useFootnote 7), and barriers (ideal worker norm, sufficiency of standard leave, and difficulty in taking up standard leave). We employed cluster analysis—a segmentation method for identifying homogenous groups of objects where objects are as similar as possible to each other within a cluster, but as distinct as possible from objects in other clusters (Sarstedt and Mooi, 2019), that is equally used in WTR researchFootnote 8. Björk et al. (2020), for instance, used this technique in a related context to explore how part-time workers can be grouped based on combinations of motives for part-time work. The cluster analysis was applied to the full survey sample (N = 241) to analyse whether employees can be categorised based on potential motives for choosing additional leave and, if so, what characterises each cluster. The seven motives listed above were selected as clustering variablesFootnote 9. The sample size exceeded 30 times the number of clustering variables, aligning with recommendations for good clustering solutions (Dolnicar et al. 2016). Additionally, clustering variables differentiated sufficiently with limited correlations between them (maximum absolute Pearson correlation equal to 0.392 (p = 0.05), well below the maximal value of 0.900 (Sarstedt and Mooi, 2019)). A hierarchical clustering method was applied, using Ward’s linkage as the linkage algorithm and squared Euclidean distance as the distance measure. Both graphical (dendrogram) and numerical criteria (Duda–Hart (DH) index and variance ratio criterion (VRC) index) were considered to decide on the number of clusters. Results for the three criteria are presented in Supplementary Information Table 6 and Supplementary Information Fig. 1. The three-cluster solution emerged as the best solution according to two out of three criteria (the dendrogram and the VRC index) and provided a good balance between cohesion within clusters and separation between clusters. Section “Cluster analysis based on motives” in the "Results" section presents the details of this solution.

Descriptives and cluster analysis based on planned time use

First, descriptive statistics for the planned time use activities were scrutinised as they provide more detailed insights into how leave-choosing employees intend to spend their additional non-working time (RQ2a). Additionally, to study whether leave-choosing employees can be categorised into groups that are internally homogeneous but distinct from each other based on planned time use (RQ2b), a cluster analysis was applied to this partial survey sample of employees who have chosen at least one additional leave day (N = 108). However, considering the limited sample size, the total number of planned time-use activities (18) was too much to be included as clustering variables in the cluster analysis. To reduce this number, a principal component analysis was applied to the 12 core activities deducted from the Belgian TUSFootnote 10. The resulting five factors were selected as clustering variablesFootnote 11. The relation between the number of clustering variables and the sample size was reasonable (with the sample size exceeding 20 times the number of clustering variables), the clustering variables differentiated sufficiently, and correlations between them were limited (maximum absolute Pearson correlation equal to 0.297 (p = 0.05)). Hierarchical clustering with Ward’s linkage and squared Euclidean distance was applied, and the number of clusters to be selected was decided on the basis of both graphical and numerical criteria. Results for the three criteria are presented in Supplementary Information Table 8 and Supplementary Information Fig. 2. The two-cluster solution came out as the best solution according to two out of three criteria (the dendrogram and the DH index) and was selected for further analysis. Details of this solution are presented in section “Descriptives and cluster analysis based on planned time use” in the "Results" section.

Template analysis

The interview data (N = 13) were analysed by means of template analysis. That is a flexible type of thematic analysis where a list of codes (“template”) is produced, representing themes expected to be identified in the textual data (King, 2004). Although template analysis has some aspects in common with thematic analysis, such as the flexibility it offers and the emphasis on constructing a hierarchical coding structure, it differs in that themes are developed and defined earlier on, and the number of coding levels is usually higher (Brooks et al. 2015). The software programme NVivo was used to sort, organise, and code the data throughout the four-step procedure. First, we familiarised ourselves with the data by transcribing and reading roughly through the data. Second, we based ourselves on the question protocol used in the interview guideline (structured along three main subjects, see the section “Qualitative data”) and the literature (see the section “Literature analysis”) to generate initial codes, which resulted in an initial template (presented in Supplementary Table 1)Footnote 12. Third, the initial template was used to code each interview transcript in the full dataset. Throughout this coding process, the initial template was revised: codes were modified, deleted, and added where necessary. In the last step, codes were revised and merged where appropriate, which resulted in the final template. Section “Template analysis” in the "Results" section presents this final template and discusses the emerging themes and codes that are relevant for RQ1 and RQ2.

Results

Cluster analysis based on motives

Table 5 compares the three resulting clusters (A–C) with respect to clustering, outcome, and profiling variables. Additionally, Figs. 1 and 2 graphically show how clusters significantly differ for clustering and outcome variables. For the clustering variables, we find that clusters significantly differ from each other (p < 0.001) for four out of the seven motives: work intensity, experienced time use for personal and social leisure, sufficiency of standard leave, and difficulty in taking up standard leave. First, cluster A scores significantly lower on work intensity compared to the other clusters. Additionally, respondents in this cluster, on average, experience relatively high levels of sufficient time for personal and social leisure as well as sufficient standard leave. However, they experience low difficulty in taking up this standard leave. Regarding outcome variables, respondents in cluster A have moderate preferences for additional leave: the fraction choosing additional leave (43.8%) and the mean number of additional leave days chosen (3.39) are in line with the total sample numbers. Moreover, cluster A significantly outperforms the other clusters with respect to mean work–life balance. Second, cluster B scores significantly lower on experienced time sufficiency for personal and social leisure as well as sufficient standard leave compared to the other clusters. Additionally, respondents in this cluster, on average, experience a relatively high work intensity and low difficulty in taking up this standard leave. All together, these motives reflect a need for additional non-working time which indeed translates into the outcome variables: with 65.6% choosing additional leave and the mean number of additional leave days chosen equal to 5.02, cluster B on average significantly outperforms the other clusters with respect to preferences for additional leave. Third, cluster C scores significantly higher on both barrier motives: on average, respondents in this cluster experience a high level of sufficient standard leave as well as high difficulty in taking it up. With respect to the other motives (experienced time use and work intensity), respondents in this cluster do not significantly differ from the other clusters. This experienced abundance of standard leave is reflected in the cluster’s significantly lower preferences for additional leave compared to the other clusters, both according to the fraction choosing additional leave (23.1%) as well as the mean number of additional leave days chosen (1.65). In summary, respondents in cluster A can be described as work–life balancers, respondents in cluster B as time-strapped leave seekers, and respondents in cluster C as leave-sufficient non-seekers. Looking at socio-demographic and job-related profiling variables, we find that the three clusters significantly differ with respect to sex, age, parental status, personal monthly salary, and seniority (p < 0.05) as evidenced by one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests. These findings are largely supported by multinomial logistic regression analyses conducted for robustness: all profiling variables, except age, remain significant, with effects being either fully similar (for sex and personal monthly salary) or partially similar (for parental status and seniority)Footnote 13. Time-strapped leave seekers (cluster B) are primarily represented by women (63.9%) who are significantly younger (mean age of 40.8 years) and have a significantly lower level of seniority (mean of 9.4 years) compared to the other clusters. The mean cluster salary of 2629 euros is in line with the total sample mean. Moreover, the majority of respondents in this cluster are parents (63.9%), with the youngest child having a relatively low mean age of 10.2 years. In contrast, leave-sufficient non-seekers (cluster C) are overrepresented by men (67.3%) with a mean age of 45.3 years and a mean seniority of 14.4 years. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the mean cluster salary (2923 euros) is significantly higher than in the other clusters. Regarding parental status, 55.8% of the cluster has children, with the youngest child on average being 13.8 years old. Finally, work–life balancers (cluster A) are fairly representative of the total sample: 56.2% of respondents in the cluster are women, with a mean age of 45 years and a mean seniority of 15.7 years. 53.9% of the cluster has children with the age of the youngest child on average equal to 15.4 years. However, the mean cluster salary is significantly lower at 2543 compared to the mean salary of leave-sufficient non-seekers (cluster C) despite similar means for age and seniority. This may suggest that clusters A and C significantly differ in other unobserved characteristics, such as occupational position or supervision, which in turn may partly explain differences in motives and preferences for additional leave. Finally, clusters significantly differ with respect to one environment-related profiling variable: time-strapped leave seekers (cluster B) perform significantly more trips within Europe by plane than leave-sufficient non-seekers (C). This could suggest that the desire and choice for additional leave translate into an increase in the environmentally impactful behaviour of plane travel. However, this conclusion should be made with caution since clusters do not differ on any other environment-related profiling variable. Such claims require a more in-depth investigation of planned time spending and potential motives at play in the choice, which is discussed in subsequent sections “Descriptives and cluster analysis based on planned time use” and “Template analysis”in the "Results" sectionFootnote 14.

Descriptives and cluster analysis based on planned time use

First, Fig. 3 shows descriptive statistics for the planned time use activities given the additional non-working time (N = 108). On average, leave-choosing employees primarily intend to spend (significantly) more time with the core family (80.6%) and friends (64.8%), as well as on resting (79.6%), hobbies (77.8%), and household chores (67.6%). Furthermore, over half of leave-choosing employees wish to spend (significantly) more time on two environment-relevant activities: inland trips (60.2%) and travelling within Europe (53.7%). The activities considered least interesting to spend (significantly) more non-working time on, are the consumption of takeaway meals (2.8%), volunteering (4.6%), and a second job (5.6%).

Second, the results of the cluster analysis are discussed. Table 6 compares the two resulting clusters (I and II) with respect to clustering, individual planned time use, and profiling variables. For the clustering variables, the two clusters significantly differ (p < 0.001) for the rest and media factor and the entertainment and social engagement factor. Looking into the details of the significant differences for individual planned time use variables, we find that cluster I primarily intends to spend more time on care activities (both childcare and other informal care), while cluster II wishes to spend more time on a broad series of other activities. This includes activities that are more socially oriented (social participation with friends and family) and more individually-oriented activities (resting, hobbies, media, and entertainment). Moreover, respondents in cluster II, on average, wish to spend more time on environment-relevant activities, including all three types of travel and going to a restaurant. However, they also wish to spend significantly more time on a less environmentally intensive activity compared to cluster I, i.e., cooking meals at home. Based on one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests for the profiling variables, we find that the two clusters significantly differ (p < 0.05) for two socio-demographic characteristics (age and household composition—i.e., relationship and parental status). Additionally, the clusters differ in sex and two job-related characteristics (personal monthly salary and seniority), although these differences are less pronounced (p < 0.10). In a robustness check using binary logistic regression, household composition remains the only significant profiling variableFootnote 15. Respondents in cluster I are relatively overrepresented by men (41.9% compared to the sample fraction of 34.3%), older (mean age of 43.4 years), and have a relatively high level of seniority (mean of 13.3 years) and salary (mean of 2718 euros). Regarding household composition, a significant majority live together with their partner and have children (72.6%). In contrast, cluster II is relatively overrepresented by women (76.1% compared to the sample fraction of 65.7%) who are on average younger (38.1 years), have a lower mean level of seniority (9.5 years) and salary (2522 euros). While couples with children remain the predominant household composition group (37.0%), a substantial portion of this cluster comprises childless singles and couples, with more than half of respondents (54.3%) having no children. Finally, clusters also significantly differ with respect to materialism (p = 0.018)—with cluster II on average being more materialistic than cluster I—but are similar for all environment-related characteristics. In summary, respondents in clusters I and II can respectively be described as in-house caregivers and outdoor leisure spendersFootnote 16.

Template analysis

Codes were organised into three main themes in the final template: (i) the choice for additional leave days within the flexible benefits plan, (ii) part-time work, and (iii) other choices made within the flexible benefits plan. Given the focus in this article on motives (RQ1) and planned time use (RQ2) specifically for additional leave, the discussion will be limited to the first main theme only. Table 7 shows the limited version of the final template (only findings for the additional leave days main theme are presented). The three key subthemes (drivers, barriers, and flexibility) are discussed in the following two sections.

Motives for additional leave

Two key subthemes within the choice for additional leave's main theme are drivers and barriers. Interviewees rarely mentioned a single, clearly demarcated motive for choosing additional leave: in most cases, the choice resulted from a mix of multiple motivations. Both pull and push factors were mentioned as primary motivations. Regarding pull factors, interviewees choose additional leave either because of a general wish for more leisure time or for performing specific activities, including quality time for self, informal work (primarily care responsibilities), social and leisure activities. Within this last domain, travel was also explicitly mentioned: while some interviewees intend to take supplementary, extended or more distant journeys, one interviewee also mentioned to use the extra time for travelling at a slower pace. Regarding push factors, interviewees indicated that work had been intense and that they needed additional non-working time to decompress or recover, with some of them having had firsthand experience with the detrimental effects of being overworked. Diverse causes were mentioned for this work intensity, including workload peaks, high availability requirements (the need to be on-call), and the experience of workload becoming heavier compared to before. A third motive for choosing additional leave relates to the flexible benefits plan itself: employees make the choice simply because it is offered in the plan and because it is financially advantageous. Fourth, the choice may be driven by a series of personal aspects. Specific personal beliefs regarding the income-leisure trade-off consistently play a key role for interviewees. They attach great importance to leisure time and the value of “life” in work-life balance, which was nicely summarised by an interviewee as follows: “I work to live, and not the other way around.” Moreover, several interviewees who are further along in their career paths referred to the transience of life. The following three quotes illustrate this: “It’s about ‘living now’, not about ‘maybe living tomorrow’. Especially because I’m not so young anymore”, “Life is already short, you know. Why wouldn’t you do it [choose additional leave]? […] When many people are falling ill around you or passing away […], that makes you think more about: what am I doing and what really matters to me? I don’t want to postpone things until I’m retired”, and “After a certain age, people say: take it easy. Because, what are we doing it [working] for anyway?” Finally, for some interviewees the choice is equally driven by contextual factors such as shifting work-life balance norms (prioritisation of life over work has become more acceptable compared to a decade ago) or a limited amount of standard leave days (because specific tasks included in their main job require to take up a substantial amount of standard leave). Beyond drivers, three groups of potential barriers emerged. First, interviewees indicated that they may reduce or eliminate their choice for additional leave in the future if other choices offered within the flexible benefits plan would be prioritised (without leaving sufficient budget for additional leave) or if the cash bonus would become necessary due personal financial reasons. Second, occupational demands may impede the choice for additional leave, namely when employees would feel unable to use up the amount of leave days in the previous year because of too much workload. Finally, personal reasons may hinder employees in their choice, such as when the amount of standard leave days would be considered to be more than enough, when employees love doing their job, or because of certain work ethics. It’s important to note that these barriers are largely hypothetical as interviewees were selected on the basis of an outspoken preference for additional leave, and as the majority of interviewees mentioned—either explicitly or implicitly—to attach great importance to this choice.

Flexibility

Beyond explicit motives, flexibility emerged as another important subtheme. A common thread across the majority of interviewees’ choice for and appreciation of additional leave resides in the flexibility it offers. The choice for additional leave creates a buffer or “a little extra” which can be flexibly used, both in terms of timing and how it is spent. The majority of interviewees stated to take up these flexible additional leave days last-minute as loose days, often on Wednesdays or Fridays. They do so when they feel the need (e.g., unforeseen care responsibilities (sick child), personal duties (shopping, hairdresser) or need for rest because of work intensity) or when a good opportunity presents itself (e.g., a day trip in case of good weather, or take leave a day earlier than planned if workload is finished earlier than expected), provided that the workload and planning allow them to. According to interviewees, this flexibility results in “peace of mind”, “breathing space”, and “a sense of freedom”. The popularity of the choice and, by extension, of the broader flexible benefits plan can be understood in the context of self-determination theory: a buffer of leave days provides employees with greater autonomy to decide how they spend their time and therefore fulfils one of the three fundamental psychological needs (next to competence and relatedness) (Ryan and Deci, 2000). However, throughout the interviews it became clear that flexibility is also at play in another respect: the company in the case study has specific organisational characteristics which require flexibility from employees. First, work tasks tend to be measured in output indicators rather than in working hours, which is a key characteristic of a post-Fordist working structure (Van Echtelt et al. 2006). This appears from employees’ perception regarding working hours (ignorance and overestimation of contractual working hours, and working hours are interpreted as moderately to highly flexible) and workload (assumed to be fixed per employee and non-transferable to colleagues when taking leave, such that taking up leave leads to work intensification). Second, the media sector in which the company operates is characterised by workload variability throughout the year, both predictable (e.g., workload peak before a school holiday) and unpredictable (e.g., breaking news). After a high-peak workload period, employees state to be in need of rest time to recover. Taken together: including a choice for additional leave in the context of a flexible benefits plan allows a company to provide appropriate compensation for the employee flexibility requirements that are—in this particular case study—sector-inherent, thereby meeting employees’ desire for flexibility.

Discussion

First, we discuss the findings related to motives (RQ1). To begin with, the cluster analysis suggests what factors are key motives for (not) choosing additional leave. Specifically, the subjective experience of a lack of time for personal and social leisure emerges as the primary driver—as it is, on average, the most experienced in the cluster of time-strapped leave-seekers. Conversely, the difficulty in taking up the standard number of leave days appears to be the primary obstacle—as it is, on average, the most experienced in the cluster of leave-sufficient non-seekers. The finding on the primary driver is corroborated by the qualitative interviews, where respondents expressed a desire for more leisure time for themselves and with others. Findings on both key motives align with Gerold and Nocker (2018), who identified gaining more free time as the main motivation for choosing the leisure option and noted post-Fordist work structures as a major obstacle to additional leisure. Beyond identifying key motives, the cluster analysis reveals socio-demographic differences between the clusters (based on regression analyses): compared to leave-sufficient non-seekers, time-strapped leave seekers are typically female, have more children, and earn a lower salary. While the overrepresentation of women and children aligns with previous findings on gendered WTR preferences, particularly for part-time work (De Spiegelaere and Piasna, 2017; International Labour Organization, 2018), the finding on income does not align with Gerold and Nocker (2018), who found actual income not to be significantly different between choosers and non-choosers of the leisure option.

Next, the interviews add to the findings from cluster analysis by revealing a range of other motives influencing the choice of additional leave. In line with literature on other types of working-time reduction, we find that push factors, pull factors, and a specific mindset that values life outside of work matter. The latter factor particularly aligns with Balderson et al. (2021), who found that a desire for reduced working hours often stemmed from the realisation that life is fragile and time is finite. Additionally, our interviews introduce a previously unexplored factor: the context of the flexible benefits plan can act as a driver (by offering the additional leave choice as convenient and financially beneficial) or a barrier (by providing other benefits and the cash bonus as alternative choices, which may be preferred over additional leave). This aligns partially with Gerold and Nocker (2018), who noted that employees might choose against the leisure option due to personal values, such as extrinsic (financial) motivations.

Second, findings for planned time use are discussed (RQ2). Regarding preferred activities for planned time use in general (RQ2a), the descriptive statistics show that leave-choosing employees primarily intend to allocate time for personal activities (resting and hobbies), spending time with others (both the core family, broader family, and friends) and performing household tasks. These results are consistent with the notion that choosers are mainly motivated by a desire for more personal and social leisure, a key finding from the motives analysis outlined earlier (RQ1). Moreover, these findings align with Mullens et al. (2020)—who found that extra hours were mostly spent on household work, personal care, and care for others—, Hayden (2006)—who found workers to largely devote the additional free time on previously existing activities, primarily resting and spending time with family and children—, and Hanbury et al. (2019)—who found that interpersonal relationships and leisure activities ranked among the primary substitution activities. Beyond these activities, employees also wish to spend their extra time on travel, including inland trips and travelling within Europe. This finding is supported by the interviews, where the majority of respondents either explicitly or implicitly mention travel. These findings align with Hayden (2006)—who found that the working-time reduction allowed more than one-third of employees to increase their short (weekend) trips, although this number marks subgroup differences based on company position—, Persson et al. (2022)—who found that employees reducing their working time report more short holiday trips, especially when working fewer days per week (rather than shorter working days)—, and Lindsay et al. (2020)—who found that financially secure downshifters altered rather than reduced their travel and holiday behaviour. Beyond confirming these findings on preferred activities, the interviews add to the quantitative analysis and to the literature by revealing that employees often choose extra leave to build in a buffer or to have flexibility: beyond planning for specific activities, a significant fraction of leave days seems to be filled last-minute without having concrete plans upfront.

Regarding subgroup differences within the group of leave-choosing employees (RQ2b), the cluster analysis suggests that a distinction should be made between couples with children, who predominantly plan to spend time on caregiving duties, and other employees, who wish to allocate their time to a broad range of activities. The interviews with parents corroborate these findings and offer further in-depth insights. While “structural” childcare duties were mentioned as a reason for taking additional leave, parents seemed to particularly value the flexibility it offered, as it enabled them to use the time off for unforeseen or last-minute activities with their children, including both caregiving (such as caring for a sick child) as well as quality time (such as spending a (half) day off with the core family in case of good weather). The importance of family structure for time spending is reflected in previous research by Mullens et al. (2020) and Buhl and Acosta (2016)—who performed separate analyses for respondents with versus without childcare responsibilities—and Hanbury et al. (2019)—who found parenting one of the main activities to spend the extra time on.

Combining results for motives and planned time use allows us to cautiously explore the potential of the additional leave choice in a flexible benefits plan for contributing to a well-being economy by creating benefits for well-being and the environment.

In terms of well-being, findings for both motives and planned time use suggest that employees primarily wish to spend time on leisure, including social activities (spending time with friends and family), both of which have been found to contribute to higher well-being (Brajša-Žganec et al. 2011; Robinson and Martin, 2008). Beyond these activities, household and (child) care tasks also emerge as important components of planned time use, particularly for parents. On the one hand, allocating extra time to these tasks can enhance well-being by improving work-life balance, particularly if it fosters a sense of greater control and allows a more relaxed approach, such as focusing on one task at a time instead of juggling multiple tasks (Mullens et al. 2020). Additionally, spending more time with children can strengthen family relationships, further contributing to overall well-being. On the other hand, to the extent that these tasks are viewed as a substitution of paid work with burdensome unpaid work (rather than enjoyable leisure activities), they may negatively impact well-being. Beyond the specific allocation of time to certain activities, the interviews reveal that employees choose extra leave days mainly because it provides them with greater autonomy over their time use. This aligns with Balderson et al. (2021), who found that full-time workers experienced their work scheme to lead to a loss of autonomy and consequently reduced their working time to gain more freedom. While the substitution activities matter for well-being, it is primarily this fulfilment of a fundamental psychological need that is expected to contribute to enhanced personal well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000). However, less clear-cut conclusions emerge when looking at two specific well-being measures: work intensity and work-life balance. While the interviews suggest that employees opting for additional leave perceive a relatively high work intensity, often citing it as a significant motivator for their choice, cluster analysis reveals no significant difference in work intensity between time-strapped leave seekers and leave-sufficient non-seekers. A similar observation holds for work–life balance, with no significant difference between the two clusters. Furthermore, independent samples t-tests reveal that employees who choose additional leave on average score significantly higher on work-intensity (p = 0.007) and lower on work-life balance (p = 0.004) compared to those who don’t. At first sight, these findings seem contradictory as working-time reduction is often motivated by and expected to contribute to well-being. They raise questions about the extent to which opting for extra leave, especially when such a choice is motivated by high work intensity, effectively translates into a reduction in work intensity. On the one hand, it is reasonable to expect that work intensity may not decrease, and could potentially even increase, when taking additional leave, given that it concerns a marginal WTR policy that is typically not accompanied by a structural reduction in workload. Furthermore, the post-Fordist organisation of work in this context could contribute to increased work intensity, irrespective of the marginal nature of the policy. Empirical evidence from several studies has confirmed this phenomenon: reductions in working hours were followed by heightened work intensity, thereby partly offsetting other well-being benefits (Hayden, 2006; Rudolf, 2014). However, caution is advised in interpreting these findings due to their reliance on cross-sectional data. Additionally, the cafeteria system had already been in place for 4 years when the study was conducted. Consequently, a causal interpretation of the results would be inappropriate. Instead of viewing the differences in work intensity and work-life balance as outcomes resulting from the choice for additional leave, they should be seen as descriptive characteristics of the two employee groups.

For assessing the potential environmental impacts of additional leave days within a flexible benefits plan, we explore two primary pathways: the income effect and the time use effect. Firstly, the traditional income effect is relevant in this case, though less pronounced compared to other types of working-time reduction (like part-time work). While additional leave days do not directly reduce an employee’s standard salary, they require a (partial) conversion of the cash bonus, thus decreasing the total monetary remuneration available for consumption. Consequently, by opting for additional leave instead of cash or other benefits offered in the flexible benefits plan, individuals forgo alternative consumption options. The extent to which this reduction in alternative consumption affects the individual’s environmental impact depends on the environmental intensity of the forgone consumption compared to that of the activities undertaken during the additional time off. This is where the time use (rebound) effect comes into play. A particular activity worth investigating is travel, as it is commonly associated with additional leave days—regularly referred to as “vacation days”—and tends to have a higher environmental impact than paid labour. Our results partly support this expectation: descriptive statistics indicate that over half of the respondents prioritise domestic and European travel, which rank as the sixth and seventh most preferred activities for additional leave. Interviews also reveal that choosers express either directly or indirectly a desire to spend (some of) their additional leave on travel. However, it is important to note that the five activities ranked higher than travel in terms of preference are generally less environmentally taxing, as they primarily consist of leisure activities and activities performed in and close to the home (Druckman et al. 2012). Moreover, last-minute buffer activities—which also represent a significant portion of how people “plan” to use their additional leave—such as spending time with friends and family or engaging in personal care, generally have a lower environmental impact. Beyond general findings on environmental impact, cluster analysis based on planned time use suggests that environmental effects are expected to be heterogeneous based on parental status: a reduction in working hours for employees with children is likely to result in lower environmental impacts compared to a similar reduction for childless employees. This is because caregiving, a binding activity common for parents, is associated with relatively limited environmental impacts and constrains the opportunities to engage in other more environmentally intensive activities such as travel (Druckman et al. 2012; Hanbury et al. 2019). Although the above findings suggest that additional leave days might lead to a neutral or even positive environmental impact, or at least not as negative as one would expect in a scenario where all extra leave is spent on travel, these conclusions should be approached with caution. The study’s data are insufficient for accurate estimations of changes in environmental impacts. Specifically, cross-sectional data on planned time use were collected (rather than panel data on actual time use changes), potentially leading to a hypothetical bias. Moreover, time use was assessed using broad categories of activities in a single survey (as opposed to more detailed categories obtained from time-use diaries), making it difficult to accurately estimate the environmental impact of a particular activity (e.g., the environmental impact of travel depends on a series of travel characteristics, including the destination, transportation mode, and activities performed during the holiday).

Conclusion

The pursuit of a well-being economy requires to think about economic reforms that prioritise both people and the planet. Examining measures that enhance both human and ecological well-being is therefore crucial. One such promising measure is working-time reduction. Existing well-being literature suggests that favouring more leisure over income can positively impact well-being, while studies on the link between working hours and environmental impacts indicate positive environmental effects of reduced working hours.

In this study we investigated one specific form of working-time reduction: the choice for additional leave in the context of flexible benefits plans. Despite its increasing popularity among employees and employers, little is known about the underlying rationale for making this choice and, consequently, its potential to generate socio-environmental benefits. We examined the motives behind this choice, how employees plan to spend the extra leave, and how subgroups of employees differ in planned time use preferences. Additionally, we explored the potential of the measure for fostering a well-being economy. Regarding motives, the results show that a vast array of motives play a role for (not) choosing additional leave, including push, pull, personal and contextual factors, as well as the specifics of the flexible benefits plan. A particular push factor and pull factor emerge as key motives: while the desire for more leisure is a primary driver, experiencing difficulty in taking up additional leave is a main barrier. Findings on planned time use reveal that employees wish to spend extra time on diverse activities—primarily individual leisure (resting and hobbies), social activities (spending time with the core family, friends, and the broader family), household tasks, and travelling—while they also keep extra days as an ad-hoc buffer. However, preferences differ depending on parental status, with couples who have children mainly planning to use the leave for caregiving duties. Regarding socio-environmental effects, the results tentatively indicate that additional leave may improve well-being by enhancing employees’ autonomy over time allocation and by fostering increased engagement in leisure activities. However, this benefit may be partially offset if paid work is replaced by unpaid household and care work. Additionally, while travel preferences are significant, employees mostly intend to replace paid labour with activities of relatively low environmental impacts compared to travel. Taken together, these findings suggest that opting for additional leave in a flexible benefits plan could be a valuable measure in the pursuit of a well-being economy. Nevertheless, findings on socio-environmental impacts should be interpreted with caution since the data used in the study do not allow for rigorous quantification of such effects.

The fact that revealed choices were investigated rather than stated preferences and that a mixed-methods approach was used, add to the strength of this study. However, several limitations restrict the scope of this study. First, it is confined to a case study of a single company, primarily comprising white-collar workers in a specific sector, thereby constraining the generalisability of findings. Moreover, the company under investigation had established collective labour agreements pertaining to two flexibility types—workplace flexibility (“hybrid work”) and worktime flexibility (“flextime”)—which offer all employees on average a similar and considerable level of flexibility. The consistent and widespread provision of flexibility among employees limits the possibility to explore one specific push driver described in the literature, namely the lack of flexibility. Second, cross-sectional data were gathered (amongst others leading to planned rather than revealed time use) at a point in time when the cafetaria system was already in place for a couple of years, potentially resulting in hypothetical bias and complicating the (causal) interpretation of results. Third, both the survey and interview sample suffer from a self-selection bias. A disproportionate representation of individuals with strong preferences for additional leave may overrepresent certain motives and planned activities, skewing the findings and limiting their generalisability to all employees. Fourth, findings from the interviews are further biased because of participant selection criteria (specifically, participants were selected on the basis of an outspoken preference for additional leave) and to be interpreted with care because certain questions were hypothetical (for example, “reasons why you would choose fewer or no additional leave days” while all interviewees had chosen at least five days). Finally, the quantitative data used in the analyses are largely self-reported and travel behaviour data may be biased because the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic—a time in which travel options were subject to restrictions. Future research should address these limitations, for instance, by expanding the sample with a diversity of companies (allowing to extend the models with both relevant micro- and macro-level characteristics), employing more comprehensive analyses (e.g., based on panel data) or exploring cleaner contexts (e.g., where the working-time reduction has not been implemented yet). Additionally, other forms of working-time reduction could be investigated and compared in a similar respect. Taken together, these insights would allow for a better understanding of the rationale behind reducing working time and the (causal) relationships between working time reduction, well-being, and environment, thereby contributing to the discourse on cultivating a well-being economy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to company and study participant privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

An overview of these motives can be found in the initial template constructed for template analysis (see the section “Template analysis”). This template is presented in Supplementary Information Table 1.

To cautiously infer environmental effects based on planned time use, the activity list was extended to include a set of activities that (i) have significant environmental impacts and (ii) are likely to be consciously altered when reducing time spent on paid labour. Regarding the first criterion, the most environmentally impactful consumption categories are housing (primarily housing fuel for heating and energy-using products, building structures for construction and demolition), transport (primarily ownership and usage of motor vehicles, air travel), and food (primarily consumption of meat and dairy) (Ivanova et al. 2016; Spangenberg and Lorek, 2002; Tukker et al. 2010; Tukker and Jansen, 2006; Wiedmann et al. 2006). Considering the second criterion, housing-related decisions are highly unlikely to be (consciously) altered in the event of working-time reduction (especially when it concerns a maximum of 10 additional leave days). Moreover, linking housing consumption categories to specific time-use activities—which is required given the planned time-use format of the survey question—is challenging. Consequently, the list of planned time use activities was extended with three activities relating to transport (commuting was not included, since it is illogical for employees to deliberately plan to choose additional leave for the purpose of reducing commuting) and three activities relating to food.

Supplementary Information Table 2 describes the measurement of work intensity, ideal worker norm, and work–life balance.

Supplementary Information Table 3 describes the measurement of materialism.

Supplementary Information Table 4 describes the measurement of environmental actions and travel behaviour.

Entries were discarded in case of missing or negative informed consent, incomplete responses, or inconsistency between administrative and survey data regarding the choice for additional leave.

The total number of experienced time use activities (10) was reduced using principal component analysis (PCA). Factors with eigenvalues > 1 were retained, utilising the orthogonal varimax rotation option, and items with an absolute factor loading of at least 0.4 for a single component were kept. After excluding the item “spending time with my core family”, three factors of experienced time use emerged for the remaining 9 items, collectively explaining 68.9% of the total variance with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index of 0.740. These factors are: personal and social leisure (4 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.779), non-care work and personal development (3 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.814), and care work (2 items, scale reliability coefficient = 0.669). Supplementary Information Table 5 shows factor loadings for each item and also the eigenvalues, percentage of variance explained, and cumulative percentage of variance explained.

As reversed causality is likely to be present between these motives on the one hand and the choice for additional leave on the other hand, using regression analysis to analyse the effect of motives on the choice would be inappropriate.

For each of the three factors of experienced time use resulting from PCA, mean scores across the items associated with the factor were calculated. These mean scores were subsequently used as clustering variables for the cluster analysis.

Factors with eigenvalues >0.97 were retained, utilising the orthogonal varimax rotation option, and items with an absolute factor loading of at least 0.4 for a single component were kept. After excluding the item “hobbies”, five factors of planned time use emerged for the remaining 11 items, collectively explaining 71.1% of the total variance with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index of 0.584. These factors are: personal development and social contribution (3 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.699), rest and media (2 items, scale reliability coefficient = 0.551), family and domestic responsibilities (3 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.484), entertainment and social engagement (2 items, scale reliability coefficient = 0.643), and second job (1 item). Supplementary Information Table 7 shows factor loadings for each item and also the eigenvalues, percentage of variance explained, and cumulative percentage of variance explained.

For each of the five factors of planned time use resulting from PCA, mean scores across the items associated with the factor were calculated. As the fifth factor (second job) consisted of a single item, the mean score for this factor coincided with the value of the item itself. These mean scores were subsequently used as clustering variables for the cluster analysis.

The objective was to create an initial set of codes based on existing literature, aiming to comprehensively address the three main subjects discussed in the interview. For the first subject (drivers and barriers), codes were generated drawing on six papers from the literature on motives for working-time reduction and one paper from the literature on motives for choices in flexible benefits plans (see the section “Motives”). The second subject (planned time use) was partially addressed by codes within the “pull factors” subtheme, and additional codes were generated based on the list of Belgian TUS activities. The third subject explored the link between the choice for additional leave and openness towards part-time work. As this aspect has not been explored in prior literature (to the best of our knowledge), no initial codes were generated for this particular subject.

To validate the findings on profiling variables, a multinomial logistic regression was conducted as a robustness check. Cluster membership based on motives was selected as the dependent variable (with three outcome values: clusters A–C), and the socio-demographic and job-related profiling variables that showed significant differences (p < 0.05) in the one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests—sex, age, parental status (number of children), personal monthly salary and seniority—were selected as independent variables. Parental status was represented by “number of children” instead of “age of the youngest child”, as the latter was not available for the full sample. The regression was run three times, each time adjusting the reference category. The results largely confirmed the initial findings based on one-way ANOVA and chi-square tests: all variables except for age remained significant for at least one of the three models. Consistent results were observed for sex and personal monthly salary across all models, while slight differences were noted for seniority and number of children. Detailed coefficients and significance levels are provided in the Supplementary Information Table 9.