Abstract

This paper examines how flouts and violations of conversational maxims are represented in translation and how this influences the different types of translational equivalence. A number of scenes from audiovisual media where there is a gap between one character’s intended meaning and another’s reply were examined by comparing the employment of conversational maxims in the source and target text. Additionally, the relation between the employed translation strategies, equivalence type, and the representation of the maxims was analyzed. The results showed that audiovisual translators tend to reduce ambiguity through strategies like addition and explicitation, which alters the features of the maxims found in the source text. Moreover, linguistic differences also make retaining ambiguity a challenge. Furthermore, while functional equivalence is often seen as the ideal type to convey the sense of a text, in cases where the text contains double meanings, the rendition of sense is no longer straightforward. As a result, translators must employ compensational strategies to maintain the ambiguity or explain its existence. The study concludes that the translators must pay attention to nuance to choose the best equivalents and phrasings for each given situation since even slight changes may change the implicatures of the text.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Communication is a cooperative act between a sender and a receiver where language is used to reach an understanding. Typically, the speaker will observe conversational maxims to convey their intention directly and explicitly (Farghal, 1995; Farghal and Kalakh, 2017). However, cooperative theory indicates that the speaker may flout or even violate these maxims while the receiver is still able to reach an understanding. This is achieved through cooperation and an understanding of implicatures where it is understood there may be a distinction between what is stated and the intentions behind the same statement (Wilson and Sperber, 2022). Moreover, implicatures are a universal and well-acknowledged aspect of communication. Unintentional violations may lead to the possibility of miscommunication. Disregarding cooperation, on the other hand, will result in miscommunication becoming a probability. Additionally, the intentional flouting and violation of maxims may be a form of manipulation, thus also violating the unspoken rule of cooperation to achieve a specific goal.

Although the concepts of conversational maxims and implicatures are universal, their application in different languages and cultures varies (Harris, 1995). Thus, they may pose a challenge to translators who desire to transfer them from one language to another. Moreover, since implicatures may contain more than one meaning, the translator may be forced to choose between the two. This is due to the likely lack of a rendition that is reflective of the two, meaning that the available equivalents may be insufficient renditions.

Translators must decide between different types of equivalence, such as literal, functional, and dynamic (Farghal, 1993). The distinction between semantic and functional equivalence separates the semantic content from what is meant by an utterance. This is similar to the notion of implicatures (Ervas, 2012). Yet when cooperation is broken, the literal and implied meanings no longer coexist, giving the utterance two separate meanings. In other words, the utterance now contains more than one sense or meaning, and this complicates the translator’s task. Here, the choice between literal and functional rendition no longer remains one between style and content; instead, it becomes one of two opposing interpretations, that intended by the speaker and that perceived by their partner in communication. This reflects the view of de Beaugrande (1978), who stated that segregating form and function when they should cooperate in equivalence could be erroneous.

Audiovisual media often attempts to emulate real speech in order for the dialog to sound natural and immersive to the viewer (Haider and Alrousan, 2022; Hassan and Haider, 2024). Since maxims are common in speech, they are thus also common in media. Furthermore, maxims are often flouted to achieve specific goals, such as implying double meanings or eliciting humor. In such cases, the translator must employ the strategies best suited for the situation and mode of translation they are working in while also working within the constraints of said mode.

This study attempts to answer the following research questions:

-

Are flouts of conversational maxims consistent between source and target texts in translation?

-

How do translation strategies and equivalence types affect the clarity of the intended and inferred meaning of the source text?

Literature review

Theoretical background

Blome‐Tillmann (2013) stated that when a person makes an utterance, it conveys a semantic meaning that could differ from its intended meaning, which can be understood through context and conventions. Grice (1975) dubbed such intended meanings as implicatures that coexist with the language maxims. These include quality, quantity, relevance, and manner. Furthermore, these maxims can be intentionally observed, challenged, flouted, or violated. Allott (2018) described conversational implicatures as indirect and unexplicit statements made by the speaker to imply their intended meaning in a way that is not reflected in the content of the utterance alone. Wang (2011) claimed that receivers must be aware of implicatures and their use in order to understand the language of the speaker properly. Lumsden (2008) argued that a degree of cooperation on the level of linguistics and extralinguistic goals is required in order for implicatures to become meaningful tools of communication. Van Tiel and Schaeken (2017) argued that the processing of an implicature is affected by its alternatives, which means that listeners may have an immediate understanding or may exert effort in decoding meaning.

Watzlawick and Beavin (1967) found that language operates on more than one level: the syntactic, related to structure; semantic, related to meaning; and the pragmatic, related to the persons creating and perceiving the communication. Hossain (2021) described communication as a cooperative social interaction that functions on the basis of logic, where meaning can be understood beyond what is said through pragmatics.

Rao (2017) argued that differentiating between implied connotative meanings and direct denotative meanings of words is essential to achieving communication. Omar (2012) stated that failure to recognize connotative meanings results in misinterpretation and, in turn, miscommunication. Matindas et al. (2020) found this especially true in nonliteral language use, such as proverbs, where the understanding of both connotative and denotative language is vital to understanding intentions. Czeżowski (1979) suggested that meaning stems from the relation of properties in addition to connotations of word usage. Khamidovna (2023) argued that connotative meaning requires analysis but can increase the effectivity and influence of an utterance. Roche et al. (2012), however, argued that cognitive alignment is mostly automatic, and context clues, including nonverbal cues, allow the receiver to process and understand the speaker’s intention. Jang et al. (2023) found that the perception of meaning compared to its intention is affected by speakers, receivers, and various contexts.

Although Taufiqi et al. (2021) found that maxims are typically obeyed in casual conversation, conversational maxims may also be flouted or violated intentionally; for instance, Attardo (1993) described jokes as a violation of the cooperative principle. Similarly, Ayasreh and Razali (2018) stated that obeying maxims reduces miscommunication while specific goals, such as manipulation, can be achieved through their violation. However, Syafryadin et al. (2020) argued that speakers may obey and violate maxims unconsciously, while Saygin and Cicekli (2002) stated that unintentional violations are indications of a failure to communicate.

Al-Qaderi (2015) found that conversational maxims were not restricted to the English language. Yet, transferring maxims from one language to another is more complex as Abualadas (2020) found that maxims are affected by cultural, social, and linguistic norms, requiring the translator to understand the observed and flouted maxims, interpersonal relations between the original speaker and receiver, and the target audience. Furthermore, Francesch and Payrató (2024) related implicatures to pragmatic ambiguity. This relates to the multiple interpretations that implicatures may prompt. Regarding ambiguity in translation, it was stated that one of four relations between the source and target texts can be found; an ambiguous ST with a TT that is ambiguous in a similar respect, an ambiguous ST with a TT ambiguous in a different manner, an ambiguous ST with an unambiguous TT, and finally an ambiguous TT for a nonambiguous ST. However, Frank (2015) argued that implicatures and ambiguity in the ST should be met with implicatures and ambiguity in the target text. Additionally, Al-Ananzeh (2015) explained that translators may face difficulties when interpreting implicatures as there is a disparity between what they convey and what they state. Aresta (2018) similarly argued that implicatures and maxims create a challenge in translation, and the quality of the rendition is affected by the translation strategies employed. Al-Shawi and Mahadi (2017) stated this is due to the additional indirect meaning, which is given as implicature, which needs to be maintained in the translation. Cui and Zhao (2017) similarly emphasized the importance of understanding and conveying the intended meaning beyond what is presented semantically. On a similar note, Gharabeh (2024) distinguished between strategies and errors in the translation of implicatures, asserting that a miscomprehension of the ST results in the employment of errors and misrepresentation of the text. Cho and Cho (2018) argued that although implicatures exist in more than one language, direct transfer is not always ideal, and some maxims must be altered to ensure the best reception from the target audience. Nurcholis (2022) argued that implicatures are universal, but maxims are not, which requires that the translator decodes and recodes the intended or implied meaning to avoid coherence shifts.

Leppihalme (1996) argued that wordplays are challenging not only to render but also to understand; thus, a translator must exert effort to provide a functional rendition. Valizadeh and Vazifehkhah (2017) found that non-equivalence may lead translators to choose between form or meaning in their translations by applying different strategies. Mustonen (2016) listed a number of wordplay components that may pose a challenge to translators, including homophony, homography, paronymy, and homonymy, in addition to idioms, allusions, malapropisms, naming, portmanteaus, and interdependence. Dealing with these, translators may require exact or partial rendering, omission, compensation, or translators’ notes.

Empirical background

Alduais (2012) tested the application of Grice’s implicature theory on the Arabic language by analyzing a recording of a natural recording and found that the observing and non-observing of maxims for communicative purposes is found in this non-English language, supporting the notion of its universality.

Simialrly, Hou et al. (2022) examined conversational implicatures in children’s literary texts and their translation and found that maxims can be used for stylization and characterization and, therefore, require strategies that reflect the style while also being accessible to the target audience. Moreover, Al-Shawi (2013) investigated the translation of euphemisms as a form of maxim flouting and found that retaining the implicitness of the source text reflects the intended softening of the meaning while explicating strategies to clarify the meaning, making it more understandable. In the same vein, Laharomi (2013) examined the translation of implicature as a result of the violations of conversational maxims from English into Persian and found that preservation was the most common strategy. Modification and explicitation followed in frequency and increased in translations that dated after the revolution, which shows the cultural influence on the rendering of implicatures.

Yastanti and Emzir (2020) investigated the strategies employed in translating implicatures in a Harry Potter novel and found that the strategies of calque, transposition, modulation, generalization, compensation, and linguistic amplification were the most frequent. Moreover, the results indicated that properly rendering implicatures increases the quality of the translation significantly. Likewise, Na’mah and Sugirin (2019) examined how subtitles dealt with implicatures by analyzing the film The Hobbit. The analysis showed that most implicatures were translated adequately, reflecting the intended meaning, with only 25% containing pragmatic shifts. This was achieved through various strategies, including adaptation, transposition, compensation, and more. Additionally, Abdi (2019) found that source text-oriented strategies are more effective in reflecting maxims in an understandable manner than target language-oriented strategies by examining the Persian translations of implicatures in the Lord of the Rings.

Machali (2012) found that conversational maxims can be used as a framework to analyze pragmatic equivalence through understanding implicature and explicature. Furthermore, Williyan and Charisma (2021) examined how the Indonesian subtitles on an English video can aid language learners in understanding implicatures through the use of strategies like borrowing and structure retention that result in pragmatic equivalence. Rahmawati et al. (2022) similarly found that using pragmatic equivalence is best suited for the accurate translation of violations of conversational maxims by examining the translation of the novel Divergent.

Methodology

Based on the Grice (1975) theory of implicature and cooperation, instances where dialogs involve misunderstanding based on the violation or flouting of conversational maxims are gathered and transcribed with their translations. The maxims are then analyzed in the source and target text, and the violations are compared. The intended and understood meanings are also examined and compared to what is reflected in the target text. This section includes the procedures taken in this study, from the selection of the data to its analysis.

Data selection

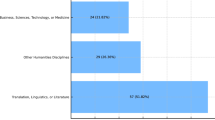

A variety of media that included unique language use was selected, as Table 1 shows.

The selected data was extracted from a diverse range of series to emphasize the role of context in language use and implicature. Many of the examined works fell under the comedy genre, as humor is often derived from the flouting of conversational maxims.

Procedures

Pieces of dialog that contained a gap between the intended and inferred meaning were extracted from various works of audiovisual media, including films and series. The dialog was then categorized based on the reason for ambiguity, such as lines with ambiguous syntax, phrases with double meanings, figures of speech, context-based ambiguity, and issues with word choice and specificity. Then, the lines were analyzed for flouts in conversational maxims. The translations of these lines were analyzed in the same manner. The various meanings and functions of the source and target texts were then compared, and mismatches were explained.

Data and analysis

This section includes the analysis of the selected data and showcases the many examples extracted from the different works.

Ambiguous syntax

The comedy film Airplane contains many jokes based on the violation of cooperation and a misunderstanding of implicatures based on syntax ambiguity. Table 2 showcases some of these incidents.

Example 1 includes a recurring joke from the film, which revolves around a character being told of news and inquiring about more details. The characters repeatedly ask the question, “What is it?” throughout the film. The pronoun “it” in this utterance refers to the news/situation/issue they are vaguely informed about. The other characters repeatedly misunderstand this question and assign the pronoun a different referent from their previous utterance. Through both specific and general context, the intended meaning is clear to the average person, including the audience, and such an utterance would not be seen as a violation of any maxim. The responding characters, however, violate the maxim of relevance by explaining clear concepts that they have not been asked about. This occurs thrice in the film: once, when he is told there is news from headquarters, a similar situation occurs when there is news from the cockpit, and finally, when he is informed his wife has been taken to hospital.

In examples 1a and 1b, the question implies, “What is the issue that the people in the headquarters/cockpit want to inform us about?” while the question in example 1c implies, “What happened to my wife that led to her hospitalization?” as well as an inquiry of her health and wellbeing along the lines of “How is she?”. Phrasing the questions in this manner would violate the maxim of quantity. Yet due to the other characters’ violation of maxims, “it” changes from “the situation/issue” to “headquarters,” “cockpit,” and “hospital.” Since “it” has no concrete meaning or referent, the intended/implied and received/implied meaning can both be derived from that utterance. This is not the case with the translation of this utterance. The translator misemployed explicitation, a common strategy found in subtitling. Explicitation involves making the ambiguous explicit, which results in the removal of the implicature, as it is impossible for something to be both implicit and explicit at once as the two concepts completely contradict each other. To make matters worse, not only does the rendition not reflect both intended and received meaning and instead reflect only one, but it is also the received meaning that is reflected. Thus, the meaning of the translated utterance is unrelated to the original meaning of the ST utterance, resulting in non-equivalence. This is an example of an error as opposed to a strategy as described by Gharabeh (2024). It is evident that the translator attempted to form the rendition based on context as “what is it?” would typically be rendered as  “what’s the problem/issue?”. This was changed based on the following line of dialog, which the translator misinterpreted as complete and properly informative context clues. Thus, the line was rendered as “What do you mean by headquarters/cockpit/hospital?”. If the translator had properly understood the implicatures and maxims, the misuse of explicitation could have been avoided, resulting in the rendition “What do you mean?” which better balances the intended and received meaning.

“what’s the problem/issue?”. This was changed based on the following line of dialog, which the translator misinterpreted as complete and properly informative context clues. Thus, the line was rendered as “What do you mean by headquarters/cockpit/hospital?”. If the translator had properly understood the implicatures and maxims, the misuse of explicitation could have been avoided, resulting in the rendition “What do you mean?” which better balances the intended and received meaning.

Example 2 contains another conversation where implicature is involved, and the receiver misunderstands the details. In this example, a flight attendant asks a nervous passenger if this is their first time flying. Since this question is typical and the implications are clear, it is simply phrased as “first time?”. The passenger misinterprets that question as “first time (feeling nervous)?” instead of “first time flying?” and answers accordingly. In this example, the translator did not resort to strategies that alter the directness of the question. Thus, the ambiguity is maintained. Since the translator did not mistakenly explicitate, both the intended and received meanings can be inferred from the rendered line.

In examples 1 and 2, implicature exists through the omission of the obvious reference. This can be rendered in Arabic by maintaining the provided level of detail as it is the presence or lack of a direct referent that causes the ambiguity and not an issue of double meaning or specific or complex syntax.

Example 3 highlights an issue with grammatical ambiguity in spoken language. The character describes military flying and flying a passenger plane as entirely different acts. From the many synonyms of the word “completely,” the character uses the adverb “altogether.” Furthermore, it is used at the end of the sentence as opposed to before the word it is modifying. This results in the passengers misinterpreting this from an adverb as the phrase “all together,” which they understand as a call to parrot the utterance. In written form, the punctuation and spelling distinguish the meanings of the two phrases; the two are more easily confused in speech. Since the flouting of maxims here, precisely the maxim of manner, is an issue of syntax and word choice, their transfer into a different language is not possible due to linguistic gaps and differences. Thus, only one meaning can be rendered, which in this case was the intended meaning, as shown in the table.

Example 4 includes the issue of wording as well. This example is based on the wording and not grammatical and syntactical issues like punctuation and arrangement. Additionally, there is the issue of referent and pronoun confusion as well. Similar to the previous example, it could not be rendered to portray the intended and received meaning. The character here uses the phrase “make out of” to mean ‘understand.’ The other character misinterprets this as “create” and begins to describe things he can make through origami. This misinterpretation also comes from misunderstanding the referent of the pronoun, which is meant to represent the writings on the paper and not the papers as a physical item. The Arabic translation, “What is your opinion on this?” leaves room for the latter misunderstanding but not the first, which plays a bigger role in shaping the reply.

Table 3 contains more examples of ambiguous language where the referent or object of the sentence is unclear due to the violation of the maxims and implicatures.

In example 5, the implicature is of the omitted indirect object. In this scene, young children are instructed to dress themselves in their best clothes by being told to “put [their] best clothes on.” Since the children are of an age where they are not expected to either give or receive assistance in getting dressed, it is understood that the request implies dressing themselves. Since this expectation clearly explicates the order as “put your best clothes on yourself,” it would be a flouting of the quantity maxim. Yet, this reduction allowed for one of the mischievous children to purposefully twist the request by completing the prepositional phrase and adding a direct object of his choice. If the utterance had been constructed around the transitive verb “wear” instead of the ditransitive phrasal verb “put on”, or if the phrasal verb had not been segmented, leaving the preposition unattended at the end, this manipulation would not have been possible. Despite this, the Arabic translation replaces the phrasal verb with the regular verb “wear.” As this verb is not ditransitive, the addition of a second object is an impossibility. Although Arabic does not have a similar phrasal verb, using the looser term  “place/put” would have allowed the character to add a second object, but he would have needed to add the preposition in his tag. Thus, “put my best clothes on… the pig” would become “put my best clothes… on the pig,” which adapts the violation of the implicature and flouting of maxims into the Arabic language. This highlights the first issue in the translation. The second is a translation error, which stems from the translator misunderstanding the source text. Since the provided rendition does not allow for a second object, its position in the utterance must be altered to result in a semantically coherent sentence. Therefore, “the pig” is changed from an animal that will be put into clothes into a descriptor for a clothing item. The translator also used addition and explicitation, rendering it as “the pig outfit.” This is a mistranslation that does not align with the utterance and its follow-through. This error reflects what was stated by Omar (2012) regarding misinterpretation leading to miscommunication.

“place/put” would have allowed the character to add a second object, but he would have needed to add the preposition in his tag. Thus, “put my best clothes on… the pig” would become “put my best clothes… on the pig,” which adapts the violation of the implicature and flouting of maxims into the Arabic language. This highlights the first issue in the translation. The second is a translation error, which stems from the translator misunderstanding the source text. Since the provided rendition does not allow for a second object, its position in the utterance must be altered to result in a semantically coherent sentence. Therefore, “the pig” is changed from an animal that will be put into clothes into a descriptor for a clothing item. The translator also used addition and explicitation, rendering it as “the pig outfit.” This is a mistranslation that does not align with the utterance and its follow-through. This error reflects what was stated by Omar (2012) regarding misinterpretation leading to miscommunication.

This shows the role of phrasing and verb choice, including the transitivity of verbs as well as the segmentation of phrasal verbs in implicatures.

The film Marry Poppins contains a scene where the characters tell some jokes. Jokes are a form of maxim flouting that is socially acknowledged and accepted. Unlike unintentional flouts and violations, the double meanings in-jokes are intentional. This difference applies to jokes made by characters and those made through them. In other words, both meanings should be indicated in the utterance regardless of the response it garners.

The joke in example 6 relies on the ambiguity of referent. In this case, it is not that no reference has been provided in the utterance but that two potential referents were included. The phrase “A man with a wooden leg named Smith,” “can either be interpreted as composed of “a man with a wooden leg” as a singular syntactic unit or a noun phrase that contains a prepositional phrase with “named Smith” being a verb phrase, or it can be seen as if it composed of “A man” as a noun phrase, with “with a wooden leg named smith” as a prepositional phrase containing a verb phrase. These different interpretations of the syntactic distribution of the sentence elements result in different interpretations of meaning. In the first distribution, the name refers to the man; in the second, it refers to the leg.

The humor in this joke is derived from the fact that implicatures from general context and language use mean the first interpretation is what is typically expected; however, the following line goes against this supposition by showing the second interpretation is the goal.

Since the ambiguity in referent is syntactic and not a result of its omission, explicitation through addition and reduction strategies is not the greatest concern. The translator, therefore, must transfer both referents without omission or addition.

Although this transfer seems straightforward, the Arabic rendition showcased a hurdle in the transfer of the implicature. As ambiguity is built on grammar and syntax, and grammar and syntax are unique in each language, such differences indicate the transferability of this ambiguity is not necessarily possible or direct.

In this case, the structures of the English and Arabic sentences align nearly exactly. Still, there is a difference in the two languages’ grammatical systems that rendered the translation flawed. This difference is grammatical gender. The Arabic language has a gendered nature where each noun is classified into masculine or feminine, and the rest of the phrase must agree with its gender. Since Arabic grammatical gender only contains masculine and feminine distributions with no neutral options, even objects are referred to with gendered pronouns. While English has the feminine she, masculine he, and gender neutral it and they, Arabic only has the masculine and feminine. Finally, other parts of speech, such as verbs and adjectives, must agree with this gendering.

In the example, the two referents are a man and a leg. In Arabic, “man” is masculine while “leg” is feminine. The line is rendered as “a man with a wooden leg whose (feminine) name is Smith)”. Since the relative pronoun “whose” is feminine, it cannot refer to the masculine man but must refer to the feminine leg based on gender agreement rules. Thus, the intended referent is no longer obscured, removing the humor from the utterance. Since verbs are also gendered, avoiding the pronoun and using the verb “named” like the source text would result in the same issue persisting. In this particular case, the line can be changed to “with the name,” removing the direct link to the referent, which removes the need for grammatical agreement. However, in other similar cases where the reference is more direct, such as when it is in the position of a subject or object, the grammatical agreement is inevitable.

In addition to gender, grammatical agreement in Arabic also includes numbers indicating single, dual, and plural. Thus, if the two potential referents differ in either number or gender, no ambiguity can exist.

Table 4 contains another instance of ambiguous referents, which can lead to misinterpretation.

Example 7 is also based on semantic phrasal distribution. In this example, the speaker intends “guy with glasses” as a single noun unit that acts as an object. The receiver treats “guy” alone as the object, with “with glasses” being a prepositional phrase that describes the verb “hit” instead of referring to the noun “guy”. This ambiguity is only possible through the use of a preposition instead of a verb like “wearing.” Despite this, translation A replaces the preposition with the verb, which clarifies the speaker’s intention without any room for doubt or manipulation. Translations B and C do not commit the same error, and both properly employ a preposition. Translations B and C are nearly identical, with the only difference being that translation B used the “the” article while translation C is more generic. Since the phrasing is generalized, translation C is the closest to the source text.

Table 5 emphasizes the role of context in understanding or misinterpreting implicatures.

The examples above, 8 and 9, both contain instances of the use of the phrase “having a friend for dinner” in different contexts. When the average person uses this phrase, the intended meaning is “inviting a friend over to eat dinner with.” The phrase can be seen as a flout of the maxim of manner as it can convey an entirely different meaning, which is “eating a friend as dinner.” General context, however, implies that it is the first option as most people are not cannibals or would not mention this fact casually in the case they were, in fact, hoping to commit an atrocious crime. In fictional contexts, on the other hand, there may be reasons to assume the speaker may intend the second meaning. The examples in the tables were extracted from two films where this is the case. In the first film, the line is uttered by a cannibal who purposefully uses it as wordplay to invoke the second meaning. The second film features personified dinosaurs as the main characters. In this scene, a carnivore invites his herbivore friends over to share a meal with them, and they, however, worry that he may have other intentions due to their respective places on the food chain. Therefore, in the original utterance, it was the first meaning that was intended. However, it was the second meaning which was received.

In both instances, the writers intended the double meaning, but the interpretation varies among the characters. As aligned with the typical use of the original phrase, translations typically follow the first meaning, as the second is inconsequential. Since languages differ, wordplays and double meanings do not transfer from one to another. Thus, translators have to decide which of the potential meanings they should convey. Usually, this is determined by context.

In the first film, example 8 is rendered as “eating a friend for dinner” in translation A and “a friend will be my dinner” in translation B. Translation A substitutes the ambiguous “have” with the direct “eat” but retains the preposition “for.” Translation B, on the other hand, formally strays from the source text phrasing completely. Despite the different phrasings, the final meaning delivered by the two renditions is the same. The issue in rendition A is the substitution of the verb; however, the English verb “have” does not have a direct equivalent in Arabic that is used in the context of eating. Instead, Arabic equivalents for “have” simply mean “possess”. Furthermore, in Arabic, “have” does not connotate with hosting either. Therefore, modulation and direct translation both fail to convey both meanings.

In the second film, the phrase in example 9 is uttered multiple times as the characters who misunderstand its intention repeat it. Thus, the same wording is used to invoke one of the two differing meanings depending on the speaker. Additionally, some of the dialog exists in song form, resulting in the characters uttering this phrase in unison as it appears in the lyrics.

In examples 9 a and b, when the line is said by the carnivore, it is rendered with a literal word-for-word translation. This results in a somewhat unnatural Arabic sentence, as “have” is not used in this context. Still, the meaning can be somewhat understood in a way that reflects the speaker’s intention in a manner vague enough to allow for misunderstanding. In this context, however, since the other characters believe they were being lured into a trap, rendering the line as “inviting friends for dinner”, following the phrasing of example 8 B but replacing the verb, would be an acceptable rendition regarding both meaning and naturalness. Example 9c employs a different verb for “have” but does not differ in meaning from example 9b. In addition, these renditions use the preposition “ ,” which gives a closer meaning to “at dinner” than “for dinner,” like the preposition “

,” which gives a closer meaning to “at dinner” than “for dinner,” like the preposition “ “ used in Example 8, which could translate as “as dinner”. Using the same preposition as example 8 would be a better reflection of the source text and a more fitting equivalent. Example 9d is uttered by the herbivores, who are the friends referred to in the utterance. In this example, the characters are attempting to convince themselves that the utterance has no malicious intentions or implicatures and simply refers to an invitation. Thus, the line is rendered in the same way as examples 9b and c. Example 9e is uttered by the original speaker once again, so it is rendered in the same manner. However, the previous lyric, “it’s not a very nice thing to do” sung by the herbivores indicates that the second meaning should have been invoked as well, regardless of who actually sang the lyric. Yet, the speaker cannot be ignored entirely, and their intentions should be relevant to the translation as well. The final example, example 9e, is uttered by the herbivore friends who state that they do not want to be “friends for dinner.” This line is rendered directly without explicating the meaning in the same way as example 8.

“ used in Example 8, which could translate as “as dinner”. Using the same preposition as example 8 would be a better reflection of the source text and a more fitting equivalent. Example 9d is uttered by the herbivores, who are the friends referred to in the utterance. In this example, the characters are attempting to convince themselves that the utterance has no malicious intentions or implicatures and simply refers to an invitation. Thus, the line is rendered in the same way as examples 9b and c. Example 9e is uttered by the original speaker once again, so it is rendered in the same manner. However, the previous lyric, “it’s not a very nice thing to do” sung by the herbivores indicates that the second meaning should have been invoked as well, regardless of who actually sang the lyric. Yet, the speaker cannot be ignored entirely, and their intentions should be relevant to the translation as well. The final example, example 9e, is uttered by the herbivore friends who state that they do not want to be “friends for dinner.” This line is rendered directly without explicating the meaning in the same way as example 8.

The varying renditions of this line, which is identical in the source text in each incident, highlight the role of context in translation, showcasing how it is a process that goes beyond the word level. Additionally, these renditions showcase how context and linguistic variance inform different equivalence types. In example 1, since the intention of the character in the first film was clear, functional equivalence was employed. The second film, on the other hand, plays with the ambiguity of the phrase to a greater extent. Thus, the renditions lean towards formal equivalence, with functional equivalence taking a more subtle approach. Moreover, these renditions differ from the typical translation of this phrase as it appears in isolation or in its average context.

In example 10, the character flouts the maxim of manner when he wishes to be turned into a prince by a genie. The genie informs him of how his utterance can be interpreted in more than one way, leading him to rephrase his request. In example 10, the translation reflects the character’s intended meaning. The phrasing in the rendition is unambiguous and can only be interpreted in the way the character meant it. Thus, the flouting of the maxim is not transferred. This reflects the difficulty in rendering both meanings which was cited by Al-Shawi and Mahadi (2017). Example 11 is rendered the same as example 10, despite being uttered by a different character to convey a different meaning. The surrounding context, including dialog and imagery supports this second meaning. This means that the translation is not an adequate equivalent for the source text. Yet, rendering the line to reflect the new meaning would diverge from the original utterance, severing their relation, which means rendering the function alone is not ideal in this scenario either.

Double meaning/pun (Homophone-Hyphen)

The examples in Table 6 revolve around characters misunderstanding specific jargon.

In example 1, the setting is a conference for ghostwriters, which are writers who are hired to create works in the name of another person. One character confuses this jargon with the literal meanings of its components and assumes it refers to people who write about ghosts and are, therefore, called ghostwriters. Since most characters in the scene are aware of its actual meaning, it is translated directly into one of its Arabic equivalents. The chosen equivalent, however, is the “invisible writer,” which contains no reference or direct connection to ghosts. Thus, the inquiry on ghosts in example 1B seems nonsensical and irrelevant instead of simply misguided. In Arabic, the term has multiple equivalents, including the calque “ “ and the akin “

“ and the akin “ “ (ghosted writer), both of which would have better suited the scenario. This indicates that even direct and accurate translations may not be ideal based on context, and therefore, translators must also consider the best rendition among the set of equivalents, even if they are synonyms or varying terminology for the same concept.

“ (ghosted writer), both of which would have better suited the scenario. This indicates that even direct and accurate translations may not be ideal based on context, and therefore, translators must also consider the best rendition among the set of equivalents, even if they are synonyms or varying terminology for the same concept.

Example 2 also revolves around a character misinterpreting jargon as the literal meaning of its components. In this scene, characters visit a hotel that has dumbwaiters, which are small elevator-like compartments that are used to deliver food to hotel guests in their rooms. One character splits the word into two in example 2a, creating an adjective, “dumb,” and a noun, “waiter.” This resulted in them thinking that a human was responsible for food deliveries. The Arabic translation renders “dumbwaiter” in 2a as “food elevator” and “dumb waiter” in 2b as “waiter.” The renditions rely on direct translation and omission. This removes the relation between the two terms and results in an explanation to a character who simply does not understand an unfamiliar concept instead of a misunderstanding based on language.

In example 3, a sly character purposefully flouts the maxim of manner through the use of homophones. Like the previous example, the terms in question here are a single noun that is split into an adjective and a different noun. In this case, the terms are “redwood” and “redwood.” The character is accused of false advertising as he told his buyers that the wood that he was selling was redwood. The character denies this accusation and states that what he had said was “redwood” in reference to the color and not to the species sequoioideae commonly referred to as “redwood.” The translations render the original utterance as “redwood,” making no connection to Sequoioideae in Arabic, thus removing the violation of the maxim of manner. Translation A reemploys this translation when the character clarifies that what he stated was “redwood” and, therefore, is not a lie. Translations b and c, on the other hand, overcompensate and alter the utterance into overt violations of the maxim of quality. Translation B states “from a red tree,” while translation C is the least acceptable rendition with the most changes. Translation c uses addition and renders the two words as “I bought it, especially from a red forest.” Both renditions imply that the wood is naturally red, which is not the truth. This goes against the character’s implication that he never lied in the description of the wood.

Figures of speech

Figures of speech are commonly used to express a notion that is unrelated to its literal contents. Through cooperation and previous knowledge, figures of speech may be used effectively in conversation. The examples in Table 7 show how construing the literal and figurative meaning of a phrase may result in miscommunication.

In example 1, when a character who is planning to commit murder through deception is asked if what he has planned is something pleasant, he flouts the maxim of manner to answer truthfully without revealing his intentions. His nephew phrases his question as “Will I like the surprise?” this is supposedly a closed question that can only be answered as “yes” or “no.” Yet, the notion of conversational implicatures entails that yes/no questions can be answered indirectly with other sentences that imply one of the two. Therefore, he answers that the surprise is “to die for.” This is a commonly used idiom that is used to express a great deal of positivity. Due to its common usage and the nephew’s trust in his uncle, he does not recognize the sinister fact that it is being used in the literal sense. Arabic also contains figurative language that expresses extreme happiness with a connection to death; thus, dynamic equivalence is possible. This is reflected in the translations as translations A and B state, “You’ll die of happiness,” while translation C states, “You’ll love it to death.” While these renditions accurately convey the deadly notion of the promise, the addition of the terms “happiness” and “love” results in a form of dramatic irony that does not stem entirely from the flouting of the maxim of manner alone but the maxim of quality is flouted as well. This example highlights the points made by Frank (2015) regarding the importance of maintaining ambiguity and implicatures in the translation process.

Examples 2 and 3 contain other flouts of manner due to the use of figurative language. One character uses idioms to describe his observations, while another takes his utterances literally. In example 2, the first character describes a lion as blue, a figure of speech used to indicate sadness. The other character misinterprets this as a description of his appearance and argues that his actual color is golden. Since this color metaphor is not used in Arabic, the expression is culturally substituted in the translations. In translation A, the description is rendered as “pale,” a descriptor which, like that of the source text, can be applied to appearance, specifically color and emotion. Since the term can describe a sad emotional state, it is an accurate representation of the character’s intention, and since it can also describe appearance and color, it can logically trigger the other character’s reply, which was translated directly. Translation B takes a similar approach yet fails to achieve the same degree of coherence. The descriptor is rendered as “dimmed.” While this term can represent both an emotional state and physical appearance, its literal sense related to appearance does not correlate directly with color. Since the term greatly diverges from the original sense related to color, the response is changed. Instead of arguing that the lion is golden in color, the character claims he looks “lit/bright,” which is the opposite of dim. Aside from straying from the source material, there are two problems with this rendition. The first is that it does not accurately represent the character’s physical features, and the second is that this descriptor is also a use of figurative language that the character does have a grasp of and, therefore, cannot logically employ. Translation C strays furthest from the source text and uses functional equivalence, removing the figurative aspect of the description.

To portray flouts of the maxim of manner through the use of figurative language, formal and dynamic equivalence should be prioritized over functional equivalence. Functional equivalence works with the message and can, therefore, only relay the meaning understood by the translator. Formal and dynamic equivalence, on the other hand, retains various aspects of the original wording, which allows the transfer of figurative or indirect meaning.

Example 4 is a conversation between the same characters as examples 2 and 3. In this example, the sense of smell is invoked figuratively, but one character thinks it is a literal reference. The main issue in this misunderstanding is that the character believes the comment is literal and directed towards him. This can be achieved through renditions A and B; however, since rendition C employs addition to explicate the reference, the ambiguity is lost. Table 8 contains further examples of literal interpretations of figurative language.

One of the main characters in the film Missing Link is a sasquatch who has lived in isolation and, therefore, does not understand the nonliteral language that is commonly used by people. Another character uses figurative language regularly, which confuses the sasquatch.

In example 6, the human character tells the sasquatch, “You have my word,” a line repeated by the character like a catchphrase throughout the film. In its multiple uses, it is translated with functional equivalence as its intended meaning, “I promise.” This is the meaning that most people, including the characters, would understand. Yet, since the sasquatch is unfamiliar with this expression, he inquires what this given word is. After relinquishing the hope of explaining the figurative nature of the utterance, the character answers the inquiry by stating that the word is “trust.” In the phrasing “I promise,” there is no indirect or ambiguous wording to inquire about. Therefore, this rendition would not fit into the conversation as the “word” in question has been removed from the utterance. As shown in the examples above, most translations manipulated and altered phrases that caused similar issues for compensation or chose to ignore the caused issues. This translation took a different approach and committed to the natural-sounding functional equivalence but used parenthesis for clarification. The use of parenthesis and translators’ notes is a simple and low-effort way to overcome cultural and linguistic gaps without the need to alter or adapt the text. These methods are not perfect as they disrupt the flow and readability of subtitles while also pervading the limited space allowed for subtitles on the screen. Nevertheless, if they are used in sparsity, they can be a useful tool.

For the line discussed above, example 6, the addition in parenthesis is the literal word-for-word translation that makes the following dialog coherent and sensible. Adding this translation, besides the original translation used throughout the film, provided consistency that enabled the audience to link the line with its previous uses.

Example 7 is a line that occurs in isolation and not one that is repeatedly used. In this case, the literal word-for-word translation was the main translation, and its functional equivalent was the appendage provided in parentheses. Since the line only occurred in the dialog surrounding its formal components, formal equivalence was prioritized.

The cartoon The Amazing World of Gumball is set in the fictional Elmore City, which is inhabited by diverse humanoid creatures. Since one of these characters is a robot, he struggles with literal thinking. Examples 8–12 in the table above are taken from two episodes that feature this character. In one episode, he loses a bet and becomes the slave of the titular character for twenty-four hours as a result. In the other episode, the characters fear that his literal-mindedness and physical powers may pose a threat to humanity, and thus, they try to give him rules that would ensure he does not cause any harm. In both episodes, his failure to understand language use causes many problems.

In example 8, when the main character wishes their principle would “get lost”, he is simply expressing his annoyance. The temporarily enslaved robot mistakes this for a literal desire and an order as well. Thus, he expels the principle to a faraway wood where he is unaware of his location, or put literally, lost. Since the expression “get lost” is not used in Arabic to mean “leave alone,” the translation substituted the line with “I wish he would get out of our lives.” This sentence expresses the character’s annoyance in a way that could lead the Robot to expel the principle to a faraway area. In example 9, the character says their teacher needs to “chill,” which means she needs to be calmer. The robot assumes this is an order involving physical temperature, so he traps her in a freezer. The translation deals with this line through the use of addition that brings the expression nearer to a natural Arabic one. The line is therefore rendered as “needs to cool her nerves,” which could lead to the Robot’s misunderstanding. Example 10 similarly uses addition, or in this case, explicitation, rendering “hand” as “helping hand,” which is more natural in Arabic. This expression, as opposed to simply translating the utterance as “ask for help,” retains the pivotal “hand,” which leads the Robot to an amputation attempt. These examples highlight the importance of understanding both the connotative and denotative meanings of nonliteral language, as argued by Matindas et al. (2020).

Examples 11 and 12 do not have similar expressions in Arabic but are translated literally. This results in unnatural expressions but maintains the coherence links between what is said and shown on screen. This shows how foreignization strategies may be chosen to overcome flouts in maxims when translating figurative expressions.

Context/schema

Table 9 shows how the sense of a word is affected by the context in which it is used, which aligns with what was stated by Blome‐Tillmann (2013).

In example 1, when a character in a beauty pageant is asked about her perfect “date,” she mistakes the word referring to a romantic get-together with its homonym that refers to a day of the year. This indicates flouts in manner and relevance. When translating polysemic words like homonyms, translators often check the surrounding linguistic context to determine which meaning to represent in the translation. Since the answer provided for this question is a day and month, the translation renders the question as “What is your favorite day of the year?”. This rendition fails to recognize the larger context, which is the flouting of maxims. The character’s answer, which involved a day and month, was not an indication of the true meaning of the phrasing but of her misunderstanding and confusion of homonyms. This highlights the importance of a schematic approach to the context that goes beyond the linguistic level of the immediately surrounding lines.

Example 2 involves the word “shoot” used in a basketball setting. In basketball, shooting refers to throwing the ball in an attempt to score it through the hoop. Thus, it is translated to indicate such in its many uses in the film. Yet, in one scene, another interpretation of this word is invoked as one of the players is a trigger-happy gunslinger. When this character is told to shoot the ball, he misinterprets this order and fires at the ball with a gun. In this instance, the translation for the word shoot still only represents its initial meaning; thus, the character’s action seems inexplicable. Since this rendition reflects the speaker’s intent, it is not a mistranslation, but it is an incomplete one that only partially represents the context. Using a vaguer term like “ ” “release it,” where “it” could potentially refer to the ball or bullet, can result in better text-scene coherence.

” “release it,” where “it” could potentially refer to the ball or bullet, can result in better text-scene coherence.

Table 10 contains further examples where context informs interpretation.

In the dialog of this scene, two gangsters are discussing the appointment of one of them to look after their boss’s wife. In the conversation, one of them flouts the maxim of manner when he says he was asked to “take care of” the wife. This line could be interpreted as “care for,” which was the intended meaning, but it is also used as a euphemistic way to say “kill.” Due to the nature of their work, the second interpretation is as plausible as the first. This results in the second character’s confusion, so he asks for an elaboration.

Example 3 is the original statement that caused the confusion. Translations A and B both translate this line directly as “take care of.” Since the ambiguity is the result of potential euphemism, a literal translation is sufficient to require inquiry. In example 2, the other character repeats the words to indicate he did not receive the message his companion was trying to send. Translation B renders this line literally the same way as it was before; translation A, on the other hand, renders it as “deal with her?” explicating the area of confusion. In example 4, the character rephrases his utterance to better align with his intentions and lessen the ambiguity. Both translations explicitate “take her out” as “accompany her” in translation A and “take her out for a walk” in translation B. These renditions clear up the confusion caused by the previous lines and enable the two characters to finally stand on the same page and continue their conversation. An interesting issue in example 4 is the fact that the phrasing “take her out” flouts the maxim of manner in the same way as example 3. The speaker uses the phrase in a literal manner but neglects the fact it is also used as an idiomatic expression, which means “kill or severely injure.” Although this phrasing has the exact same issues as the original, this is not pointed out in the dialog. Thus, the translations rendered their intended meaning without emphasizing its ambiguity, unlike the previous example. This indicates that different strategies are used based on whether or not the flouts of maxims are acknowledged in the scene or have plot relevance.

Word choice/specificity

Table 11 shows examples where word choice alters the specificity and clarity of an utterance.

In this film, the main character is provided with his every wish by a magical power. However, many of his wishes backfire as he flouts the maxims of manner and quantity in his wishes.

In example 1, in his desire to end world hunger, he wishes that everyone could have “as much food as they want.” In his wish, he fails to recognize the gluttonous and irresponsible potential of human nature, which leads people to “want” more than they “need” or even fail to make good decisions regarding nutrition, thus wanting foods that they would enjoy eating rather than ones that would provide necessary nutrients. Therefore, this wish causes a rise in obesity and similar health issues. Translation A, however, renders the wish as “enough food.” If the character had phrased his wish this way, it would not have led to overeating as the supply would have matched the necessity and not exceeded it. Translation B omits the term “as much,” which would seem like it would alter the meaning as it is directly linked with quantity, but the impact is minuscule as the wish is still linked with human desire, which is often excessive. Example 2 similarly deals with human greed. In an attempt to end homelessness, the character wishes that everyone can live in their dream house. Since most people’s dream houses are big and private, providing such housing is spatially inefficient, which has negative consequences, with housing spreading out to far-off uninhabited areas like deserts. While translation A properly reflects the source text, translation B alters the line into “live in the place they dream of.” Changing the chosen aspect from house to place does not align with the resulting consequence, as no one dreams of living in a desert. This shows how minuscule alterations, which are typical of subtitling, affect conversational maxims. In example 3, the character wishes to end the senseless war by removing any motivations for war. Instead of removing wars, the wish simply detaches war from reason, which results in more wars. Translation A contains an error in negation, resulting in a mistranslation regardless of wording, while translation B is a proper rendition of the source text. In example 4, the character hopes to remove the negative effects of global warming by wishing to reverse it. Instead, now its consequences have swung to the opposite extreme. This is translated as “reverse” and “flip,” both of which are acceptable renditions that follow the wording of the source text.

Table 12 contains additional examples of this issue.

In example 5, the main character tells the robot to no longer take his orders. He soon regrets this after realizing he needs to undo the order given before. The translation states, “Don’t do what I say,” which may be seen as a functional equivalent of the source, “You no longer take orders from anyone.” Still, this rendition is not a proper equivalent as it contains too many flaws that can be exploited. In the original utterance, “no longer” indicates that all following orders will be nullified, “take orders” indicates any order no matter how it is delivered, and “from anyone” indicates that neither the character nor anyone else can give the robot orders. This phrasing leaves no room for any loopholes for the characters to abuse to their benefit. The phrasing in the translation can easily be manipulated. “Don’t do what I say” is not connected to a time, and it can thus be argued that this command nullifies the previous command the characters try to cancel. Additionally, this phrasing only deletes commands made by the speaker, which implies that the robot may still take orders if they were made by someone else. Finally, this phrasing is linked to speech, which means it does not apply to other forms of communication, such as writing.

Examples 6 and 7 also deal with flaws in expression and loopholes. In example 6, the character sets a rule for the Robot that inhibits him from “raising” a “hand” against anyone. These restrictions are overcome by using other movements and body parts. This is properly reflected in the translation. In example 7, the characters test the effectiveness of their restrictions by telling the robot to “hurt” one of them. This is translated as “hit”. The word “hit” has a limited meaning that can be stopped through the placed constrictions. Therefore, when the Robot kicks and poisons the character, he is not following the given order. This means that this substitution for a near synonym or hyponym is an inadequate translation. This indicates that common subtitling strategies like reduction and substitution alter meaning when language is supposed to be taken literally. Therefore, literal or word-for-word translation is needed to retain the flouts of the maxim of manner.

Furthermore, loopholes should be considered in areas of relevance and should be accurately conveyed.

Conclusion

Translation is a process intrinsically linked to equivalence and context, as it is often considered a transfer of meaning and content. To infer and convey meaning, translation is a process of decoding and recoding. Furthermore, translation is an act of communication where the translator is the medium between the source text and the target audience. Communication involves linguistic aspects, but it is mainly an act of cooperation. Therefore, the translator utilizes general and specific context to understand and then render the meaning specific to the source text. Usually, this meaning is clear and direct, but violations and flouts of maxims may complicate this. Still, this does not mean that ambiguity cannot be cleared through context. This allows translators to choose the closest available equivalent of the intended meaning. Yet, if the ambiguity in the source text is intentional, the task is once again no longer simple. For instance, in the dialog of audiovisual media, the intended meaning of one character may be misinterpreted by another who continues the dialog based on this confusion. In such cases, translating the intended meaning alone is insufficient, as the perceived meaning must also be reflected to maintain cohesiveness and coherence in the scene.

Ambiguity can take form as the result of the flouting of conversational maxims such as the maxims of manner, quantity, and relevance, as well as breaking the cooperative principle. Linguistically, this is a result of syntax, grammar, wording, semantics, and word choice. Word choice is complicated in speech by areas like homophony, homonymy, and polysemy, where certain sounds could correspond with multiple senses and meanings. Regarding grammar and syntax, ambiguity may arise from unclear structures where the segmentation of phrases obscures which concepts are linked. Issues like verb transitivity level play a role in this as well. Additionally, some aspects may be implied or referenced indirectly. Furthermore, using pronouns may put another wedge between the wording and the referent. Thus, the lack of clear referents may be a result of segmentation or indirectness.

Due to linguistic differences, transferring such flouts cannot be direct. For example, words with different meanings sharing one pronunciation in a single language do not necessitate that they share a pronunciation in another. This causes the acknowledged challenge of translating wordplays and puns. Similarly, languages do not share grammar systems either. Thus, not all syntactic structures can be transferred, and the transfer of some may result in unnatural language. Moreover, the grammatical agreement persistent in Arabic may lessen the potential referents in a sentence. Although not discussed in this paper, diacritic markers could reduce the ambiguity resulting from complex syntactic distribution.

The transfer of flouts of conversational maxims is, therefore, a complicated process. First, the translator must navigate which maxims are being flouted. This is arguably the most important step, as a failure to recognize the flouts inevitably results in inaccurate or incomplete translations. After which, the area of ambiguity should be pinpointed as part of the decoding segment of the translation process. This allows the translator to infer both the intended and perceived meanings. After structure and meaning are dissected, the transfer process may commence. The translator must choose the best strategies to convey a proper equivalent of the source text. Additionally, they must be wary and avoid strategies that remove ambiguity, like the common strategies of addition and explicitation. If there is no direct proper rendition available, compensation becomes necessary, whether through translation strategies such as substitution, transposition, and modulation or translators’ notes. The translators must also be aware that certain strategies may be beneficial in some cases but detrimental in others.

Furthermore, equivalence in translation can take many forms, and the use of formal, dynamic, or functional equivalence can alter the effectiveness of the target text. For instance, formal and dynamic equivalence may be prioritized to maintain ambiguity, as functional is the most connected to meaning and intent. Additionally, foreignization may be employed to prioritize ambiguity over the naturalness of the utterance.

Regarding context, translators must grasp the wider context and not rely solely on the following line of dialog. Relying on misunderstanding would result in a gap between the intended meaning of the utterance and what is presented by the translator as its equivalent. While it is ideal to present both intended and received meaning and somewhat acceptable to only render the intended, it is an error to only render the received meaning as it does not align with the original utterance. Therefore, it is essential that translators employ a schematic approach that enables them to fully grasp the context.

Finally, the translators must pay attention to nuance to choose the best equivalents and phrasings for each given situation. Even slight changes may change the implicatures of the text, or one word may be a better fit even among its synonyms.

Therefore, it is recommended that translators dealing with conversational implicatures and the flouting of maxims thoroughly analyze the text, referring to both micro and macro contexts. This enables them to grasp all relevant meanings evoked by the source text. This provides guidance regarding which strategies should be employed. Here, it is important to note that the chosen strategy could cater to the specific example rather than what is typically recommended, highlighting the role of function and intention in translation. For instance, some cases may benefit from foreignization and literal translation, while adaptation may be better suited for others. However, translators must be aware of linguistic and cultural differences, recognizing when compensation strategies are necessary.

This paper focused on implicatures through the lens of language and translation strategies. While some allusions were made regarding culture, future research may place cultural aspects and differences at the forefront. Other researchers could also examine the effects of text type and translation mode on the quality of the translation of implicatures.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

12 May 2025

The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for the financial support under annual research grant number [KFU251649].' The original article has been corrected.

References

Abdi H (2019) Exploring the translator’s solutions to the translation of conversational implicatures from English into Persian: the case of Tolkien’s the Lord of the Rings. Iran J Appl Linguist 22(1):1–26. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-3013-en.html

Abualadas OA (2020) Conversational maxims in fiction translation: New insights into cooperation, characterization, and style. Indones J Appl Linguist 9(3):637–645. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v9i3.23214

Al-Ananzeh MS (2015) Problems encountered in translating conversational implicatures in the Holy Qurʾān into English. Int J Engl Lang Transl Stud 3(3):39–47. http://www.eltsjournal.org/archive/value3%20issue3/4-3-3-15.pdf

Al-Qaderi IAU (2015) A pragmatic analysis of applying violating the maxims to the Yemeni dialect. Int J Linguist 7(6):78–93. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v7i6.8762

Al-Shawi MA (2013) Translating euphemisms: Theory and application. J Am Arab Acad Sci Technol 4(8):123–132. https://doi.org/10.12816/0015328

Al-Shawi MA, Mahadi TST (2017) Challenging issues in translating conversational implicature from English into Arabic. Int J Comp Lit Transl Stud 5(2):65–76. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.5n.2p.65

Alduais AMS (2012) Conversational implicature (flouting the maxims): applying conversational maxims on examples taken from non-standard Arabic language, Yemeni dialect, an idiolect spoken at IBB city. J Socioll Res 3(2):376–387. https://doi.org/10.5296/jsr.v3i2.2433

Allott NE (2018). Conversational implicature. In: Aronoff M (ed) Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 1–27

Aresta R (2018) The influence of translation techniques on the accuracy and acceptability of translated utterances that flout the maxim of quality. Humaniora 30(2):176–191. https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.v30i2.33645

Attardo S (1993) Violation of conversational maxims and cooperation: the case of jokes. J Pragmat 19(6):537–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(93)90111-2

Ayasreh A, Razali R (2018) The flouting of Grice’s conversational maxim: examples from Bashar Al-Assad’s interview during the Arab Spring. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci 23(5):43–47. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2305014347

Blome‐Tillmann M (2013) Conversational implicatures (and how to spot them). Philos Compass 8(2):170–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12003

Cho E, Cho S (2018) Grice’s maxims of conversation and their usefulness in translation studies. J Transl Stud 19(5):155–172. https://doi.org/10.15749/jts.2018.19.5.006

Cui Y, Zhao Y (2017) Implicature and presupposition in translation and interpreting. In: Malmkjaer K (ed) The Routledge handbook of translation studies and linguistics. Routledge, London, pp. 107–120

Czeżowski T (1979). Connotation and denotation. In: Pelc J (ed) Semiotics in Poland 1984–1969. Synthese library. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 73–80

De Beaugrande R (1978) The concept of equivalence as applied to translating. In: Beaugrande RD (ed) Factors in a theory of poetic translating. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, pp. 94–100

Ervas F (2012) The definition of translation in Davidson’s philosophy: semantic equivalence versus functional equivalence. TTR 25(1):243–265. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015354ar

Farghal M (1993) Managing in translation: a theoretical model. Meta 38(2):257–267. https://doi.org/10.7202/002721ar

Farghal M (1995) Euphemism in Arabic: a Gricean interpretation. Anthropol Linguist 37(3):366–378. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes2000.6.1.5

Farghal M, Kalakh B (2017) English focus structures in Arabic translation: a case study of Gibran’s The Prophet. Int J Arab-Engl Stud (IJAES) 17(1):233–251. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes2000.17.1.13

Francesch P, Payrató L (2024) Pragmatic ambiguity, implicatures, and translation. Stud Linguist 78(1):156–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/stul.12219

Frank DB (2015) Implications of implicatures for translation. Paper presented at the Bible Translation, Dallas, TX

Gharabeh T (2024) Strategies and errors in interpreting conversational implicatures of political discourse. Int J Linguist Transl Stud 5(3):147–167. https://doi.org/10.36892/ijlts.v5i3.496

Grice HP (1975) Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan JL (eds) Syntax and semantics: speech acts. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, pp. 41–58

Haider AS, Alrousan F (2022) Dubbing television advertisements across cultures and languages:: a case study of English and Arabic. Lang Value 15(2):54–80. https://doi.org/10.6035/languagev.6922

Harris JC (1995) The teaching of implicature to ESL learners. Master of Arts, California State University, San Bernardino, USA

Hassan S, Haider AS (2024) Options for subtitling English movie lyrics into Arabic. Stud Linguist Cult FLT 12(1):82–104. https://doi.org/10.46687/LHTD6033

Hossain MM (2021) The application of Grice maxims in conversation: a pragmatic study. J Engl Lang Teach Appl Linguist 3(10):32–40. https://doi.org/10.32996/jeltal.2021.3.10.4

Hou C, He B, Zhang Z, Yang Q (2022) Inferring conversational implicature: managing implicit and explicit information in the translation of English children lLiterature. Int J Educ Humanit 5(2):296–303. https://doi.org/10.54097/ijeh.v5i2.2192

Jang H, Braun B, Frassinelli D (2023) Intended and perceived sarcasm between close friends: what triggers sarcasm and what gets conveyed? Paper presented at the proceedings of the annual meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Sydney, Australia

Khamidovna NN (2023) The expression of connotative meanings in the structure of the English language. Paper presented at the integration conference on integration of pragmalinguistics, functional translation studies and language teaching processes, Italy

Laharomi ZH (2013) Conversational implicatures in English plays and their Persian translations: a norm-governed study. Int J Appl Linguist Engl Lit 2(5):51–61. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.2n.5p.51

Leppihalme R (1996) Caught in the frame: a target-culture viewpoint on allusive wordplay. Translator 2(2):199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.1996.10798974

Lumsden D (2008) Kinds of conversational cooperation. J Pragmat 40(11):1896–1908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.03.007

Machali R (2012) Gricean maxims as an analytical tool in translation studies: questions of adequacy. TEFLIN 23(1):77–90. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v23i1/77-90

Matindas FF, Samola N, Kumajas T (2020) Denotative and connotative meanings in English proverbs (a semantic study). J Engl Cult Lang Lit Educ 8(1):30–50. https://doi.org/10.53682/eclue.v8i1.1590

Mustonen M (2016) Translating wordplay: a case study on the translation of wordplay in Terry Pratchett’s Soul Music. Master’s Thesis, University of Turku

Na’mah I, Sugirin S (2019) Analysis of conversational implicature in the Hobbit movies subtitle. Paper presented at the eleventh Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2018), Bandung, Indonesia

Nurcholis IA (2022) Implicature and the role of the translator. At-Ta'lim: Media Inf Pendidik Islam 10(1):98–105. http://www.bokorlang.com/journal/28liter.htm

Omar YZ (2012) The challenges of denotative and connotative meaning for second-language learners. ETC 69(3):324–351. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42579200

Rahmawati W, Haryanti D, Laila M (2022) A pragmatic equivalence of violating maxims in novel translation of divergent. Al-Lisan: J Bhs 7(2):93–111. https://doi.org/10.30603/al.v7i2.2584

Rao VCS (2017) A brief study of words used in denotation and connotation. J Res Sch Prof Engl Lang Teach 1(1):1–5. https://www.jrspelt.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Csrao-Denotations-n-Connotations.pdf

Roche JM, Dale R, Caucci GM (2012) Doubling up on double meanings: pragmatic alignment. Lang Cogn Process 27(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2010.509929

Saygin AP, Cicekli I (2002) Pragmatics in human-computer conversations. J Pragmat 34(3):227–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(02)80001-7

Syafryadin S, Chandra WDE, Apriani E, Noermanzah N (2020) Maxim variation, conventional and particularized implicature on students’ conversation. Int J Sci Technol Res 9(2):3270–3274. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/cza8y

Taufiqi MA, Hanan A, Priangan A (2021) An analysis of conversational maxims in casual conversation. Masile 2(2):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1213/masile.v2i2.30

Valizadeh M, Vazifehkhah AE (2017) Non-equivalence at idiomatic and expressional level and the strategies to deal with: English translation into Persian in animal farm by George Orwell. Shanlax Int J Educ 5(4):31–37. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v9i4.4095

Van Tiel B, Schaeken W (2017) Processing conversational implicatures: alternatives and counterfactual reasoning. Cogn Sci 41(5):1119–1154. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12362

Wang H (2011) Conversational implicature in English listening comprehension. J Lang Teach Res 2(5):1162-1167. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.2.5.1162-1167

Watzlawick P, Beavin J (1967) Some formal aspects of communication. Am Behav Sci 10(8):4–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764201000802

Williyan A, Charisma D (2021) Translating conversational implicatures from English to Indonesian in Youtube video entitled The Team Meeting. ETERNAL (Engl Teach J) 12(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.26877/eternal.v12i1.8299

Wilson D, Sperber D (2022) On Grice’s theory of conversation. In: Werth P (ed) Conversation and discourse: structure and interpretation. Routledge, London, pp. 155–178

Yastanti U, Emzir AR (2020) Strategies in translating conversational implicature in Harry Potter and The Cursed Child Novel. Paper presented at the international conference on education, language and society, The Universitas Negeri Jakarta, East Jakarta, Indonesia

Acknowledgements

This research received grant no. 189/2023 from the Arab Observatory for Translation (an affiliate of ALECSO), which is supported by the Literature, Publishing & Translation Commission in Saudi Arabia. The authors thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for the financial support under annual research grant number [KFU251649].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions