Abstract

As a novel thinking approach to human resource management, employee experience (EX) has become a critical strategic focus in fundamentally reframing the employment relationship. However, the construct definition and measures of EX have not been adequately addressed in the existing literature. Based on self-determination theory, this study provides a conceptual foundation for EX and emphasizes its conceptual uniqueness. Furthermore, through two phases (six studies) of the scale development procedure, we developed and validated a 20-item EX scale (EXS). Specifically, we first identified five dimensions of EX through three qualitative studies (Phase 1): work-related, interpersonal harmony, organizational management, professional development, and remuneration package. Subsequently, we validated the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, predictive and incremental validity, and measurement invariance of the EXS through three quantitative studies (Phase 2). Our findings suggest that EX is related to similar constructs (job satisfaction, employee engagement, and workplace well-being) yet possesses unique characteristics and can significantly influence employees’ work-related consequences (turnover intention and organizational identification). Finally, the theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future directions of this study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Who matters most to the organization: shareholders, customers, or employees? There appears to be constant debate on this issue (Adams et al., 2011). In the traditional view of business, shareholders and customers are generally regarded as the most important interests (Rao, 2017), as shareholders provide capital and customers generate revenue. However, with the development of modern human resource management thinking, numerous researchers have emphasized that businesses require a reconstruction of the relationship with employees if they desire to achieve better survival and growth (Plaskoff, 2017). Certainly, various factors can affect the improvement of employment relationships (Li and Yang, 2023), and therefore, organizations are required to gain a deeper understanding of multiple factors, such as the needs, expectations, and emotions of employees (Plaskoff, 2017).

Employee experience (EX), an emerging but well-attended concept, emphasizes the integrated experience of the employee (Batat, 2022). EX occurs with a logic similar to the customer experience: it represents the totality of employee’s (customer’s) interactions with the company, from the first contact of potential recruitment (knowing about the brand) to the last interaction at the end of the employment (end of the purchase) (Tucker, 2020). The prevailing view on employee well-being is that when employees have a positive work experience, it not only increases the productivity and profitability of the company (Silvestro, 2002) but also significantly increases employees’ loyalty (Veloso et al., 2021), which in turn reduces turnover. Specifically, if employees have a positive experience at work, their job satisfaction will increase, which will lead to more active participation in their work tasks (Tucker, 2020). This, in turn, can further lead to an increase in the quality of the product or service they provide, thus increasing customer satisfaction (Gong and Yi, 2018) and contributing to the company’s development.

However, although the literature on EX has gained many important insights, there are still several gaps in current studies. First, achieving positive EX is centered on demonstrating care for employees in their work environment (Plaskoff, 2017), with identifying and satisfying employees’ needs being the primary factor in facilitating EX (Tucker, 2020; Yohn, 2020). Therefore, EX-related studies should focus more on employees’ individualized needs and preferences (Lee and Kim, 2023). In other words, employees typically value relatively subjective outcomes, such as well-being (Batat, 2022). Similarly, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) suggests that the fulfillment of employees’ basic psychological needs is an effective predictor of well-being and performance (Deci et al., 2017). However, the majority of current studies have explored the interaction perspective, focusing on the process of employees’ interactions with their organization, colleagues, and work environment (Batat, 2022). For example, through the logic of the interaction perspective, EX refers to employees’ responses to stimuli from multiple sources (Malik et al., 2023). Obviously, the interaction perspective, which emphasizes the passive acceptance and response of employees to external stimuli, is suitable for explaining the effect of EX on employees’ psychology or behavior. However, it is prone to ignore the importance of employees’ intrinsic motivation and subjective psychological needs.

Second, as mentioned earlier, EX covers various elements that are closely related to employees’ needs. However, due to the differences in the perspectives of existing studies, the components of EX currently exhibit a fragmented distribution and lack of systematic integration and sorting. For example, several scholars view organizational climate as a representative factor of EX (Farndale and Kelliher, 2013; McCallum et al., 2024), while others view goal uncertainty, organizational culture, and individual insecurity as the core experience of employees to the organizational change (Roald and Edgren, 2001). Importantly, the definitional ambiguity also makes current studies prone to confuse EX with similar concepts such as job satisfaction (Batat, 2022) and employee engagement (Cornelius et al., 2022; Lemon, 2019), which in turn leads to the bias of the study results and misunderstanding of the concepts in subsequent studies.

Furthermore, although the importance of EX is growing, there is still a relative paucity of existing measures. Specifically, there is still no unanimous consensus on measures of EX (Yadav and Vihari, 2023; Yildiz et al., 2020). Most of the relevant studies rely on traditional interviews or case methods (Malik et al., 2023), which cannot comprehensively and precisely capture the complexity and dynamics of EX. Also, differences in various aspects, such as the level of economic development and cultural systems, may lead to significant differences in job needs and preferences among employees in different countries/regions (Fisher and Yuan, 1998). Therefore, relevant studies should focus more on the development of diversity measures. However, existing measures typically lack specificity and refinement to satisfy the measurement needs of EX in the context of different industries, organizational cultures, and employee groups, which limits the generalizability of the research results.

Therefore, to address the aforementioned gaps, this study focuses on the genuine needs of employees and attempts to advance studies on the construct definition and measures of EX. Specifically, we first reviewed relevant studies on EX and then systematically conceptualized it, and discussed the similarities and differences between EX and similar concepts. Second, as shown in Table 1, we identified the structural dimensions of EX and generated initial items in the first phase using web crawlers, open-ended questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews. Subsequently, through the quantitative approach in the second phase, we validated the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, predictive and incremental validity, and measurement invariance of the scale of EX (EXS). In conclusion, this study can provide practical diagnostic tools for companies, which can help managers accurately capture the dynamics of EX, identify the core issues involved, and then generate personalized intervention strategies. Especially in today’s rapidly iterative business environment, this study provides a decision support system for managers to transform from reactive response to proactive prediction.

This study provides several contributions to the literature on EX. First, through the clues provided by several studies (Lee and Kim, 2023; Plaskoff, 2017; Tucker, 2020; Yohn, 2020), we suggest that it is more appropriate to focus on the degree of satisfaction of employees’ intrinsic needs when studying employee well-being. For example, positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement (Yang et al., 2024). To this end, we attempted to conduct the study based on the SDT perspective to delve into the far-reaching effects of employees’ intrinsic needs, such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, on EX to bridge the limitations of the current studies in perspective. Moreover, unlike traditional studies that centered on the organization (such as job satisfaction and employee engagement), this study emphasizes the centrality of employees’ needs in the employment relationship from the perspective of employees’ subjective experience, echoing the trend of the experience economy era. In this regard, by introducing motivation theory into this study, we expand the traditional view of the interaction perspective and provide a more integrated and comprehensive theoretical framework for the literature on EX.

Second, by comprehensively integrating and summarizing the composition of EX, this study helps to bridge the fragmented distribution of EX in existing studies. For the first time, we used web crawler technology for massive text mining of employees’ online reviews, covering the authentic voices of employees from 30 companies and avoiding the selectivity bias of traditional questionnaires. Meanwhile, we also combined materials from open-ended questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, breaking through the limitations of traditional scale development procedures that typically rely on a single data source, which in turn enabled the dimensions of EX to reflect both breadth (massive text) and depth (individual narratives). Therefore, this study ensures that the composition of EX stems from the employees’ genuine needs rather than a single theoretical derivation, which helps to provide a clear theoretical foundation and object of study for subsequent research. Additionally, this study provides a clear definition of the concept of EX and distinguishes it clearly from similar concepts such as job satisfaction and employee engagement. In this regard, by analyzing the connotation and extension of similar concepts, this study helps to reduce the bias of research results and establish a clearer and more unified conceptual foundation.

Third, to bridge the limitations of EX in the measures, this study drew on authoritative scale development procedures (Carpenter, 2018; Morgado et al., 2018) to provide a comprehensive and reliable measure of EX. Specifically, this study utilized a mixed-methods research design that overcame the limitations of traditional interview or case methodology and provided a more scientific measure for subsequent studies. For example, the multi-source qualitative data collection helped to improve the comprehensiveness of the scale items; the rigorous quantitative data analysis procedures ensured the reliability and validity of the measures. In this regard, the present study contributes to a more accurate measurement and evaluation of EX and provides a solid empirical foundation for subsequent studies.

Furthermore, China is currently in a period of rapid economic growth, which has led to the unique characteristics of employees’ needs and experiences. Studies have demonstrated that China not only has the highest employee turnover rate in Asia (Lee et al., 2018) but also is one of the countries with lower job satisfaction globally (Nie et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019). Subject to cultural institutions, the needs and preferences of Chinese employees possibly differ significantly from those in Western countries (Fisher and Yuan, 1998). As the first study to explore EX in the Chinese context, we collected numerous authentic voices from Chinese employees that accurately reflect their needs and preferences. In this regard, this study provides a baseline for cross-cultural comparisons and helps to enrich and deepen the understanding of EX in different cultural contexts. Certainly, by identifying the components and measures of EX, this study provides concrete, practical guidance for organizations to evaluate EX more accurately, target the improvement of employee well-being, and ultimately provide powerful support for human resource management decisions.

Defining employee experience

The concept of employee experience

The concept of EX can be traced back to the birth of the “Experience Economy”. Customer experience was one of the first things that attracted the attention of management practices as the economic structure gradually transitioned from a service economy to an experience economy (Jain et al. 2017). Along with the advancement of related studies, researchers have also identified the critical role of human capital in creating customer experience, hence the birth of the concept of EX (Batat, 2022). As an extension of the customer experience, EX prompts organizations to rethink whether their employees are receiving the same attention and experience as their customers (Plaskoff, 2017). With this in mind, in exploring the concept of EX, we refer to the generative logic of customer experience to explore the deeper connotations of the concept of EX in terms of two different routes of EX: the horizontal employee journey and the vertical interaction factor.

Employee journey

The concept of employee journeys is derived from customer journeys. The customer journey represents the interaction between the company and the customer, with a key focus on how service processes and experiences are viewed from the customer’s perspective (Jain et al., 2017). Employee journeys are the vehicle for EX. Plaskoff (2017) states that EX stems from an employee’s engagement with all the touchpoints in their work journey; these touchpoints represent each significant phase of an employee’s career. Specifically, the employee journey is the collection of all touchpoints in the process, from when an employee contacts a company (recruitment) to when they leave the company (exit) (Tucker, 2020). In other words, from the time a potential employee views the job opening at a company to the time they leave the company, all factors that employees experience during this time constitute the complete concept of EX (Plaskoff, 2017).

Generally speaking, it is not consistent with the goal of economic rationality for the company to arrange work exactly according to the employees’ subjective experiences, as the employees may maximize their preferences or outcomes (Batat, 2022). However, as mentioned earlier, employees are typically more concerned with subjective feelings and experiences. Therefore, only employee journey design that relies on employees’ subjective feelings can truly reflect their needs and expectations (Plaskoff, 2017). Based on the above discussion, we suggest that the critical touchpoints for employee journeys lie in the critical needs that are most valued by employees rather than the phases at which managers generally focus on employee development.

Interaction factors

As previously stated, employment relationships are subject to the combined effects of multiple factors (Li and Yang, 2023), which means that employee behavior cannot occur in a vacuum. Interaction factors are all those factors that are likely to interact with employees in the horizontal track that is the employee journey, both internal factors within the organization (for example, supervisors, colleagues, and the physical environment) and external participants (for example, customers) (Batat, 2022; Plaskoff, 2017). Clearly, the impact of interaction factors on employees occurs throughout the employee journey (as shown in Fig. 1).

Construct definition

SDT suggests that the impact of various environmental factors on employee motivation and experience depends heavily on employees’ basic psychological needs (Deci et al., 2017). Further, basic psychological needs include three types: competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which are typically described as conditions that influence employee motivation, well-being, and performance. Therefore, creating workplace conditions in which employees perceive that their basic psychological needs are satisfied has already become a critical goal for modern companies. Combined with the SDT perspective, EX can be initially understood as whether the needs that employees value at work are being met.

Furthermore, we have been significantly inspired by the conceptualization of EX in existing studies. For example, based on the interaction process perspective, EX can be defined as “sum of an employee’s feelings across their interactions with an employer (Tucker, 2020)”, “the feelings, perceptions and emotions that an employee experiences through their involvement in work and within the organizational environment (Itam and Ghosh, 2020)”; from the perspective of emphasizing employee perceptions, EX can be defined as “employee’s holistic perceptions of the relationship with his/her employing organization (Plaskoff, 2017)”.

In summary, to unify these themes, we combine the ideas of SDT and define EX as the employee’s subjective experience of the satisfaction degree of their needs during this period, from the first contact with the company to the complete end of the interaction with the company.

Differentiation from related concepts

Based on the above definition, the concept of EX can be further distinguished from similar constructs. First, as the concept of EX is derived from customer experience, most issues regarding customer experience can be extended to employees. For example, are customers satisfied with the products or services provided by the company? Did the customer develop loyalty to the company’s brand? There are also, of course, significant differences between the two. Customer experience typically directly affects a company’s competitive advantage (Jain et al., 2017), whereas EX requires intervening in a company’s relevant outcomes by causing an impact on other factors (Plaskoff, 2017). Furthermore, EX may be one of the crucial foundations for generating customer experience (Maylett and Wride, 2017). On the one hand, employees are important vehicles for communicating products and services to customers; on the other hand, employees are typically more likely to perceive changes in customer experience.

Second, although both job satisfaction and EX focus on employees’ feelings at work, there are still some differences between the two. The EX emphasizes the integral feelings generated by employees during their work, including all aspects of the employee’s career cycle (Yohn, 2020). Examples include relationships with colleagues, the physical environment of the workplace, and interactions with customers (Batat, 2022). Job satisfaction is defined as the pleasant or positive emotional state that arises from an employee’s evaluation of their job (Ilies and Judge, 2004) and focuses primarily on the employee’s subjective appraisal and affective response. In contrast, EX covers a broader scope and is not limited to focusing on employees’ satisfaction with their current job content. For example, EX also focuses on employees’ pre-employment and post-employment phases (Plaskoff, 2017). Moreover, job satisfaction also stems from employees’ evaluations of their work experience (Ilies and Judge, 2004), and therefore, improvements in EX typically contribute directly to the increase in job satisfaction (Itam and Ghosh, 2020; Lee and Kim, 2023).

Furthermore, employee engagement as a valid predictor of job satisfaction (Saks, 2019) also differs significantly from EX. Employee engagement is defined as an employee’s affective and intellectual commitment to the organization or the autonomy that an employee demonstrates at work (Saks, 2006). Conceptually, employee engagement focuses more on reflecting employees’ responses to work-related factors, whereas the EX emphasizes employees’ perceptions. In other words, EX is possibly an antecedent of employee engagement (Tucker, 2020); that is, employees typically base their subsequent responses on perceptions. Similarly, EX is usually viewed as an effective means of enhancing employee well-being (Batat, 2022). Workplace well-being, which includes affect and satisfaction related to work (Zheng et al., 2015), differs significantly in focus from EX, which emphasizes employees’ integral feelings and experiences of their work from multiple perspectives, such as cognitive, affective, social, and economic (Plaskoff, 2017), whereas workplace well-being focuses more on the employee’s positive affective experiences at work and satisfaction with work, that is, it focuses more on the affective dimension.

Phase 1: scale development

Morgado et al. (2018) state that the first step in scale development should be item generation, where it is necessary to identify what is included and excluded from the definition in this phase. As mentioned earlier, EX involves highly subjective characteristics (Batat, 2022); therefore, the most authoritative voice on EX should originate from the subject of the experience, that is, the employee. In other words, scale development for EX should begin with employees expressing their most concerned job needs (qualitative studies), followed by empirical testing (quantitative studies). Therefore, we divided the scale development and validation process into two phases.

To acquire richer materials in qualitative studies, we designed three studies in the first phase. First, we collected the online review texts through web crawler technology; second, we further acquired materials about EX through open-ended questionnaires; and finally, we explored the dimensional composition of EX through semi-structured interviews. Moreover, at the end of the first phase, we generated initial items for EXS by integrating the above materials.

Study 1: textual analysis of online reviews

Sample and procedure

We take acquisition of employees’ online reviews as the basis of Study 1. Online reviews about the company published by employees are not only closely related to job satisfaction and employee turnover, but also the first step for potential employees to generate EX (learn about the company) (Stamolampros et al., 2019). After comparison, we chose ZHILIAN (https://www.zhaopin.com/) as the source of online employee reviews. ZHILIAN is a representative human resource service platform in China, similar to Glassdoor. Moreover, to enhance the representativeness of the sample companies, we refer to the “Best Employers Ranking” published by ZHILIAN and Peking University (ZHILIAN, 2023), and select the top 30 companies as the sample companies.

First, we acquired all the online reviews of the sample companies through the Houyi Collector (https://www.houyicaiji.com/), which yielded 32,927 materials. Subsequently, the first author conducted a preliminary screening of these reviews and removed the invalid content, which yielded a total of 31,541 reviews. To ensure the reliability of the data, we arranged two groups of master’s degree students (two from each group, both majoring in human resource management) to conduct a secondary screening of the online reviews. Specifically, the two groups examined the review materials item by item separately and marked the review contents that were irrelevant to the topic. When both groups marked a review (1364), we removed it; when the marking occurred in only one group, a secondary determination was made by the second author (623 were removed). Finally, we obtained 29,554 reviews related to the topic, totaling 899,754 words.

Results

To further analyze the online review texts, we performed word-splitting on the ANSI-encoded TXT texts with the help of Rost CM6 software. Subsequently, we performed word frequency analysis on the word-split text and used it as the basis for subsequent analysis. Through the above steps, we obtained the word cloud of employee online reviews, as shown in Fig. 2.

Specifically, to increase the informational intensity of the text, we present only the keywords with a frequency of more than 500 times (40) in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2, the environment has the highest frequency (9899 times), and climate has the lowest frequency (515 times). Subsequently, based on the Chinese cultural context, we further combined semantically similar/identical high-frequency keywords such as wages/salary and atmosphere/climate. Finally, as shown in Table 2 (non-italicized section), we obtained 25 job needs that are of more concern to employees.

Study 2: open-ended questionnaire

Sample and procedure

We completed the collection of the open-ended questionnaire and all subsequent questionnaires (Studies 4 and 5) through the Chinese survey platform Credamo (https://www.credamo.cc/#/) and randomly embedded attention-checking questions in the questionnaire (Ward and Meade, 2023). As a well-known online survey provider in China, Credamo is similar to MTurk and has been proven to be able to provide higher-quality data for survey studies in China (Del Ponte et al., 2024).

At the beginning of the open-ended questionnaire, we first introduced participants to the conceptual connotations of EX. Secondly, we listed several descriptions of EX with the help of materials from Study 1. For example, “The harmonious working climate provided by the company gives me a good experience” and “The generous salary provided by the company gives me a good experience”. Finally, we provided three open-ended questions: I. What do you value most about the experience provided by the company? II. What do you think the company you work for needs to be improved compared to other companies in the same industry? III. What are the reasons you choose to continue working at this company? Participants were encouraged to describe their thoughts as much as possible. Specifically, question I was designed to understand the needs that employees are most focused on at work. Question II was designed because we speculated that EX might be influenced by how employees compare to similar groups. Question III examined the reasons for employee retention.

Initially, we obtained 121 questionnaires, and 99 participants’ responses were retained through quality screening measures, including 1397 textual materials. Participants included 60 females (60.61%) and 74 (74.75%) with undergraduate degrees or above. Participants’ ages were distributed primarily between 28 and 32 years old (N = 30, 30.30%) and 33–37 years old (N = 30, 30.30%). Participants’ tenure was concentrated in 1–6 years (N = 44, 44.44%) and 7–12 years (N = 33, 33.33%). Furthermore, 69 participants were married (69.70%), and 44 participants were general staff (44.44%).

Results

Through the same data screening procedure as in Study 1, we finally obtained 1228 valid textual materials. Subsequently, the first author organized the textual material to align the keywords with those in Study 1 as much as possible. Eight new keywords appeared after word frequency counting through the Rost CM6 software (see the italicized section in Table 2).

Taken together, through word-frequency analysis of the textual material from Studies 1 and 2, we obtained 33 need factors that employees are most concerned about at work.

Study 3: semi-structured in-depth interviews

Sample and procedure

We collected and organized experts’ comments on the interview outline via focus group interviews (including a professor in the field of human resource management and two human resource management managers) before conducting the semi-structured interviews. After several rounds of discussion, we finalized an interview outline containing seven questions (for example, please talk about the most impressive positive and negative events during your work, and please talk about what your ideal work is in your mind). Moreover, given that the interview topics involved employees’ reviews of the company, which may lead employees to hide their genuine thoughts, all the participants we selected were acquaintances or employees recommended by acquaintances.

We first pretested two participants and adapted the interview outline. Before the formal interviews began, we determined the time and place of the interviews based on the participants’ requests and only allowed one researcher to be present, which helped to create a relaxed and trustworthy environment for the participants. At the beginning of the formal interview, we read the confidentiality agreement to the participants and obtained their informed consent. After that, we audio-recorded the interviews with the participants’ permission.

It is worth emphasizing that at the end of each interview, the research group organized the interview materials and started the next interview only after they finished organizing it. In other words, Study 3 followed the idea of synchronizing data collection and analysis. When the interview reached the ninth employee, we found that no more new ideas emerged. Subsequently, we invited three additional participants for interviews, but no new ideas emerged. Therefore, we concluded that continuing to increase the sample of interviews would not help to generate additional themes, and this interview had reached the theoretical saturation point (Zheng et al., 2015). Finally, the nine formal interview participants provided over 80,000 words of textual material, and the average duration of the formal interviews was 61.33 min.

Participants in Study 3 included five females and four married employees. On average, the participants had a monthly salary of 8166.67 CNY, were 28.11 years old, and had a tenure of 5.22 years. All of the participants had undergraduate degrees or above. Six participants were general staff, and three participants were basic supervisors. Participants came from different industries, for example, educational training (3), information technology (3), and manufacturing (2).

Coding strategy

We employed the Grounded Theory approach to coding the textual material from Study 3, which included open coding, categorization, and axis coding (Walker and Myrick, 2006). First, we assembled two coding groups; group R1 consisted of two master’s degree students who had been involved in the data screening process in Study 1, and group R2 consisted of the first author and one other master’s degree student. Second, before formal coding began, all coders participated in the training, which included familiarization with the coding rules, coding practice, discussion, and clarification of any ambiguities. The coding training was conducted using textual material from the two interviewed pretest participants. Furthermore, if there was disagreement between the coding results of the two groups, group discussions were held under the guidance of R3 (a professor in the field of human resource management) to reach a consensus.

We followed the guidelines of Díaz et al. (2023) and employed an iterative coding procedure to code the interview material. Specifically, R1 first analyzed the textual material, including highlighting text segments and conceptualizing them. When R1 was completed, R2 began analyzing the same textual material. Notably, R2 can view the text segments marked by R1 while analyzing but cannot view the concepts generated by R1. When the coding iteration finished, R3 adjudicated the coding results. For example, whether R1 and R2 conceptualized the same textual material consistently and whether R2 created new fragments and concepts based on R1. When the adjudication was completed, we calculated inter-rater reliability (IRR) based on the adjudication results. We continued to reference the guidelines of Díaz et al. (2023) and employed Krippendorff’s α to evaluate IRR. This method of statistical measurement is particularly suitable for studies with multiple raters and different levels of measurement (Krippendorff, 2018). Specifically, we calculated Krippendorff’s α coefficients by entering the scoring data provided by R3 into the web-based statistical package K-Alpha Calculator (Marzi et al., 2024).

Results

During the open coding, both groups conceptualized phenomena that emerged from the original interview material. For example, “Our company’s attendance system is particularly strict, and it feels inhumane to deduct money for even one minute of lateness. Take me, for instance. I live pretty far from the company, and it takes me almost an hour to commute every day.” It can be conceptualized as a “too strict attendance system”, “lack of humanistic care”, and “long commuting time”. After open coding, we extracted 41 concepts from the original interview material in total. It is worth emphasizing that after analyzing the textual material of the first interview participant, Krippendorff’s α coefficient between R1 and R2 was 0.76, which is below the satisfactory threshold (0.80; Krippendorff, 2018). Therefore, we discussed the marked text segments and concepts until consistency was reached. Subsequently, the new iterative procedure of open coding continued from the textual material of the second participant (Díaz et al., 2023). Overall, based on all textual material, Krippendorff’s α coefficient between R1 and R2 in the open coding section was 0.86, suggesting that the degree of consistency between R1 and R2 exceeded contingency.

The categorization section needs to analyze the associations between all the concepts. In other words, the two groups need to identify similar concepts and summarize them into a unified label. For example, “vacation/leave,” “overtime policy,” and “work schedule” can be summarized into the label “work arrangement.” In this section, we identified 12 categories in total. Moreover, Krippendorff’s α coefficient between R1 and R2 was 0.90, which is acceptable.

Axial coding builds on the categorization section, which primarily develops major categories by discovering and establishing associations between categories. Employing the same iterative procedure as the above section, we obtained five major categories in total through this section. Specifically, work-related represent factors directly related to the work itself, including job content and nature, work arrangement, and work burden. Interpersonal harmony focuses on interpersonal relationships and interactions within the organization and consists of care and affective connection, dynamic interpersonal relationships, and communication and cooperation. Organizational management is concerned with the macro-management aspects of the organization, including management system and process, as well as corporate culture and values. Professional development focuses on the personal growth and career development of employees, for example, growth resources and support, as well as career paths and opportunities. The remuneration package involves a sense of material fulfillment for employees, including salary and performance, as well as benefits and security. Moreover, the Krippendorff’s α coefficient between R1 and R2 in this section was 0.92, which meets the acceptable standard.

The example of the coding process for Study 3 is shown in Table 3. Finally, we randomly selected one participant’s textual material and invited two master’s degree students who had not participated in the coding section described above to code it, and no new concepts emerged. Therefore, the dimensional construction of EX is relatively well-established.

Initial scale development

Following the guidelines of Morgado et al. (2018), we generated initial items for the EXS employing a combination of inductive and deductive approaches. Specifically, we extracted 41 items in the interview material and 14 items in other similar scales (Yadav and Vihari, 2023; Yildiz et al., 2020). Ultimately, we identified an initial EXS that included 55 items.

Further, we optimized the items according to Carpenter’s (2018) recommendations. First, we sent the 55 items mentioned above to a professor in human resource management and two Ph.D. candidates in psychology and invited them to carefully evaluate the content adequacy of the items based on the concept of EX (seven items removed at this step). Next, we invited two human resource management managers and five general staff to check the remaining items for clarity of presentation, ease of understanding, no ambiguity, and practicality (seven items removed at this step). Finally, we sent the remaining items to the employees who had participated in the semi-structured interviews and refined the formulation of these items based on their comments (no items were removed at this step). After these procedures, we finally obtained 41 items as the initial EXS and conducted subsequent tests.

Phase 2: scale validation

To further validate the scale items, we designed three studies in the second phase. First, in Study 4, we reduced the items using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), further validated the construct validity of the EXS using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and tested the measurement invariance of the EXS across critical demographics (such as gender, age, and education) using multi-group CFA (MGCFA). Second, in Study 5, we tested the convergent and discriminant validity of the EXS by choosing the previously discussed related constructs (job satisfaction, employee engagement, and workplace well-being). Finally, in Study 6, we tested the predictive and incremental validity of the EXS (the explanation of EX for organizational identification and turnover intention).

Study 4: item reduction and test of factor structure

Exploratory factor analysis

We recruited 400 full-time adult employees from China through Credamo. Through quality screening measures, we ultimately retained 357. We requested participants to report their degree of agreement with the EXS items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Furthermore, EFA was performed with principal axis factoring extraction and Promax rotation provided by SPSS software, as the factors were not uncorrelated (Carpenter, 2018).

Participants included 194 females (54.34%), 207 married (57.98%), and 290 (81.23%) who had undergraduate degrees or above. Participants’ ages were primarily distributed between 23 and 27 years old (N = 172, 48.18%) and 28–32 years old (N = 138, 38.66%), and the tenure of participants primarily concentrated in 1–6 years (N = 211, 59.10%) and 7–12 years (N = 114, 31.93%). Furthermore, the majority of participants were general staff (N = 254, 71.15%).

First, we conducted a reliability test for all items. The results showed that the Cronbach’s α of the EXS was 0.73. However, there were five items whose Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) values were less than the criterion of 0.50 (0.26, 0.31, 0.32, 0.35, and 0.41, respectively). With the removal of these five items, the overall reliability of the scale improved. The reliability of the remaining 36 items was 0.76. Furthermore, the result of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.83, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was p < 0.001, which implies that the data are suitable for factor analysis.

Second, the results of the EFA indicated that the remaining 36 items were loaded on the five factors, respectively, and the scree plot also depicted a sharp decline between the fifth and sixth factors, suggesting that the data provided the five main factors. Additionally, based on the pattern matrix results, we removed eight items with factor loadings less than 0.50 (Harold et al., 2022) and five items with cross-loadings greater than 0.40 (Zheng et al., 2015). Finally, we again discussed the remaining 23 items through the expert grading method, removing three items with unclear or overlapping representations.

Finally, we obtained an EXS containing five dimensions and 20 items in total. The EFA results showed that the remaining 20 items were loaded on the five factors and totally explained 67.46% of the variance. Table 4 shows the content of the final EXS and its factor loadings.

Confirmatory factor analysis

We recruited 500 full-time adult employees from China through Credamo. It is worth emphasizing that existing studies commonly split data from the same sample randomly into two for use in both EFA and CFA, which leads to their typically good data fit. However, this practice may also result in the loss of the added strength of the CFA (Morgado et al., 2018). Therefore, we started the CFA survey two weeks after the EFA survey, and we did not allow duplication of participants between the two surveys. Similarly, we requested that participants score the degree of agreement with the EXS’s items (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

We ultimately retained 427 participants through quality screening measures. Participants included 220 females (51.52%), 269 married (63.00%), and 349 (81.73%) who had undergraduate degrees or above. There were more participants aged 28 or above (N = 235, 55.04%). Participants’ tenure mainly centered on 4–6 years (N = 183, 42.86%) and 7 years or above (N = 126, 29.51%). Moreover, the majority of the participants were general staff (N = 339, 79.39%).

Drawing on the study by Harold et al. (2022), we employed the five-factor model as the baseline model and compared the differences in goodness-of-fit metrics with the one-factor model (all items loaded onto a single factor) and the ten four-factor models (items of any two dimensions loaded onto one factor). As shown in Table 5, the results of CFA indicate that the five-factor model has a good fit to the data (χ2 = 249.72, df = 160, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.04) and significantly outperforms the other competing models. These results support the construct validity of the EXS. Furthermore, the EXS showed higher reliability again (Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

Measurement invariance

To further enhance the rigor of the scale validation methodology and generalizability of the findings, we tested the EXS’s measurement invariance across critical demographics employing the MGCFA. Additionally, the data used to test measurement invariance relied on the sample we used to conduct the CFA (N = 427).

We selected demographic variables by focusing on differences in needs (Deci et al., 2017). Specifically, gender and age are the groups most typically employed for comparison (Zheng et al., 2015). In the Chinese cultural context, gender is typically assigned different role expectations. For example, females need to focus more on work-life balance, while males need to place more emphasis on career development opportunities. Employees of different ages are usually at different career development stages, which leads them to have different career expectations. For example, younger employees are likely to be more concerned with career growth opportunities and work challenges, while older employees are likely to be more focused on job stability. Furthermore, tenure and position in the organization typically have a significant relationship with age. Thus, similarly, new employees are likely to be more concerned with self-learning and advancement (Brush et al., 1987), and the general staff is likely to place more emphasis on career development prospects.

According to human capital theory, employees with higher education typically have higher educational investments. As a result, they may develop higher career expectations as a way of balancing the educational investment previously paid (Brush et al., 1987). Furthermore, different marital statuses may also lead to changes in employees’ needs. Based on the cultural background considerations in China, married employees are usually required to take on more family responsibilities. For example, taking care of children and supporting parents, which may enhance their need for work-life balance. In summary, we attempt to test the measurement invariance of EXS across gender, age, education, tenure, marital status, and position to ensure the applicability of EXS across different groups.

We strictly followed a stepwise approach to test the three main levels of measurement invariance: (a) configural invariance, (b) metric invariance, and (c) scalar invariance. Specifically, as shown in Table 6, first, we tested configural invariance to determine whether the basic factor structure of the scale is consistent across groups. The results show that the factor structure of the EXS was consistent across all groups as expected, indicating that configural invariance was satisfied. Second, based on the confirmation of configural invariance, we further tested the metric invariance to ensure that the interpretations of the factor loadings were similar across groups. We evaluate this with the help of fit indices and analyze the differences in factor loadings across groups to determine whether there were significant cross-group measurement differences in EXS. The results showed that the variation in each of the fit indices was less than 0.01. Thus, the metric invariance of the EXS was supported. Finally, to confirm whether the observed differences truly reflect differences in the scale across groups, we conducted a test of scalar invariance. We explored in depth the stability and reliability of the scale across contexts by comparing the intercepts and factor loadings across groups, combined with changes in the fit indices. Again, the change in the various fit indices was less than 0.01, and thus, the scalar invariance of all items was validated.

Study 5: convergent and discriminant validity

We tested the convergent and discriminant validity of the EXS through the previously discussed related constructs, including job satisfaction, employee engagement, and workplace well-being. We expect that although EX is similar to these constructs, it is conceptually and empirically different from them.

Sample and procedure

Study 5 collected time-lag data from full-time adult Chinese employees via Credamo. Specifically, to avoid potential common method bias, we completed the survey at three-time points (one week apart). At the first time point (T1), participants completed reports of demographics and EX; at the second time point (T2), participants reported job satisfaction, employee engagement, and workplace well-being; at the third time point (T3), participants completed the two scales employed to test predictive and incremental validity (organizational identification and turnover intention).

At T1, 500 participants provided valid responses that passed the quality screening measures. One week later, we collected data from 428 participants at T2, retaining 409 participants via quality screening measures. Subsequently, 365 participants completed the survey at T3, with a final retention of 353 participants via quality screening measures. Participants included 190 males (53.82%), 223 unmarried (63.17%), and 268 (75.92%) who had undergraduate degrees or above. There was a higher percentage of participants aged 23–27 (N = 162, 45.89%) and 18–22 (N = 96, 27.20%). Participants’ tenure was primarily concentrated in 1–6 years (N = 184, 52.12%) and less than one year (N = 107, 30.31%). Additionally, a higher percentage of participants were general staff (N = 227, 64.31%) and basic supervisors (N = 76, 21.53%).

Measures

We followed the translation-back-translation procedure of Klotz et al. (2023) to translate all non-Chinese scales into Chinese. Furthermore, all scales were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

We used the 20 items in Table 4 to measure EX. In Study 5, EX had a Cronbach’s α of 0.85. Job satisfaction was assessed with the six-item scale from Tsui et al. (1992). The sample item was, “How satisfied are you with the nature of the work you perform (Cronbach’s α = 0.90)”. Employee engagement was assessed using the five-item scale from Saks (2006). The sample item was, “Sometimes I am so into my job that I lose track of time (Cronbach’s α = 0.85)”. Workplace well-being was assessed with the six-item scale by Zheng et al. (2015). The sample item was, “I find real enjoyment in my work (Cronbach’s α = 0.84)”.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity was validated when there existed correlations between the focus scales and similar constructs (Harold et al., 2022). Table 7 provides the correlation coefficients between all variables involved in Studies 5 and 6. The results indicate that EX was significantly and positively related to job satisfaction (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), employee engagement (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), and workplace well-being (r = 0.28, p < 0.01). Furthermore, all five dimensions of EX had significant positive relationships with EX (r = 0.63, 0.59, 0.67, 0.69, 0.70; p < 0.01). Thus, the above results support the convergent validity of EX.

Discriminant validity

We tested discriminant validity by proving that EX differs empirically from similar constructs. First, the results of CFA reconfirmed that EX exhibited a good fit to the data (χ2 = 269.39, df = 160, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.04). Second, we constructed six-factor models by juxtaposing the five dimensions of EX with similar constructs, and we constructed a series of new five-factor models by combining the five dimensions of EX with similar constructs. As shown in Table 8, the goodness-of-fit of any of the six-factor models was significantly better than the goodness-of-fit of the corresponding series of five-factor models. These results support the discriminant validity of EX.

Study 6: test of EX’s nomological network

Potential consequences of EX

As mentioned earlier, the interaction perspective is well suited to explain the effects of EX on employee psychology or behavior. Therefore, we explored the potential consequences of EX based on the logic of social exchange theory. Social exchange theory emphasizes the principle of reciprocity in interpersonal interactions (Ahmad et al., 2023), which states that individuals will evaluate the costs and gains in their interactions with others and expect to receive returns from others to build and maintain positive relationships (Cook et al., 2013). When individuals perceive that the benefits from relationships outweigh the costs incurred, they will tend to maintain and deepen the relationship; conversely, they may reduce inputs or terminate the relationship (Cropanzano et al., 2017).

On the one hand, when employees have a good experience in the organization (such as receiving respect, support, and developmental opportunities), they will perceive that the organization values and cares for them and thus consider the relationship with the organization to be worthwhile (Ahmad et al., 2023). As a result, employees will then tend to reciprocate the organization by increasing their organizational identification. Moreover, a good EX implies that employees’ psychological needs are satisfied, which will lead employees to consider that the organization fulfills its commitment to them (Cook et al., 2013), resulting in a willingness to give back to the organization and enhance their identification with the organization. Therefore, we hypothesize that EX and organizational identification are positively related (H1).

On the other hand, a good EX enables employees to experience the sincerity and efforts of the organization. Therefore, according to the logic of the reciprocity principle, employees are more likely to stay in the organization due to a sense of gratitude and responsibility to the organization and consider the decision to leave more cautiously even if they face external temptations or other difficulties (Cropanzano et al., 2017). In contrast, if employees encounter negative experiences in the organization (such as lack of support, unfair treatment, and hindered career advancement), they will perceive the costs in the organization as higher than the gains (Cook et al., 2013). According to social exchange theory, at this point, employees may reduce their engagement in the organization or even consider leaving in pursuit of better opportunities (Ahmad et al., 2023). In conclusion, a good EX can reduce frustration and dissatisfaction at work by satisfying employees’ material and psychological needs, thus reducing turnover intention. Therefore, we hypothesize that EX and turnover intention are negatively related (H2).

Sample and measures

We tested EX’s predictive and incremental validity using the sample from Study 5 (N = 353). In this process, predictive validity was established when EX was not only theoretically but also empirically related to the predictive construct. Furthermore, EX’s incremental validity was validated when EX still significantly predicted these criterion variables after controlling for similar constructs to EX.

We measured EX using the 20 items in Table 4. Organizational identification was measured using Smidts et al.’s (2001) five-item scale. The sample item was, “I feel strong ties with my company (Cronbach’s α = 0.84)”. Turnover intention was measured using Scott et al.’s (1999) four-item scale. The sample item was, “I would prefer another more ideal job than the one I now work in (Cronbach’s α = 0.79)”.

Tests of predictive validity

As shown in Table 7, the results of the correlation analysis indicated that EX was significantly positively related to organizational identification (r = 0.43, p < 0.01) and significantly negatively related to turnover intention (r = −0.42, p < 0.01). Therefore, the correlations between the main variables initially support us in conducting the next step of hypothesis testing.

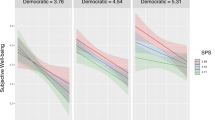

Subsequently, we further tested the predictive validity of EX through hierarchical regression. As shown in Table 9, after controlling for demographics, EX was significantly positively related to organizational identification (Model 2: β = 0.41, p < 0.01) and significantly negatively related to turnover intention (Model 6: β = −0.37, p < 0.01). Hypotheses H1 and H2 were supported. Furthermore, the value of ΔR2 indicated that besides the explanation of the dependent variable by demographic variables, EX significantly explained 16% of the incremental variance in organizational identification (Model 2: ΔR2 = 0.16, p < 0.01) and significantly explained 12% of the incremental variance in turnover intention (Model 6: ΔR2 = 0.12, p < 0.01). Thus, the predictive validity of EX was supported.

Tests of incremental validity

EX and job satisfaction are conceptually relatively similar (Batat, 2022), and the results of convergent validity also support the correlation between the two. Therefore, we chose job satisfaction as the most relevant competing construct with EX.

As shown in Table 9, first, after controlling for demographics, job satisfaction was significantly positively related to organizational identification (Model 3: β = 0.16, p < 0.01) and significantly negatively related to turnover intention (Model 7: β = −0.28, p < 0.01). Next, when we added EX to the regression model, the positive relationship between job satisfaction and organizational identification became not significant (Model 4: β = 0.08, ns), and the correlation coefficient between job satisfaction and turnover intention also decreased (Model 8: β = −0.21, p < 0.01). Furthermore, EX was significantly positively related to organizational identification (Model 4: β = 0.39, p < 0.01) and significantly negatively related to turnover intention (Model 8: β = −0.33, p < 0.01). Importantly, after considering both demographics and job satisfaction, EX still significantly explained 13% of the incremental variance in organizational identification (Model 4: ΔR2 = 0.13, p < 0.01) and 10% of the incremental variance in turnover intention (Model 8: ΔR2 = 0.10, p < 0.01). Thus, the above results provide evidence supporting the incremental validity of EX.

Discussion

Although EX has received widespread attention in practice, related academic studies are still insufficient. To stimulate studies in this area, we drew on SDT to establish a conceptual foundation for EX and developed an EXS consisting of 20 items. Specifically, through web crawling techniques, open-ended questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews, we identified five dimensions of EX: work-related, interpersonal harmony, organizational management, professional development, and remuneration package. Furthermore, we validated EXS through a series of rigorous quantitative studies. For example, measurement invariance, convergent and discriminant validity, and predictive and incremental validity. The results of this study not only help to promote employee well-being but are also strategically important for achieving sustainable corporate development.

Theoretical contributions

This study provides several theoretical contributions. First, previous studies have typically focused on the dynamic experience of employees based on the interaction perspective (Malik et al., 2023); for example, employees’ interactions with work factors affect their cognitive and emotional states (Batat, 2022). However, the advent of the experience economy has already made employees the focus of organizational concern (Plaskoff, 2017), and studies on EX have evolved from “the importance of EX” to “what is the experience that employees genuinely care about” (Lemon, 2019; Yadav and Vihari, 2023). For example, some studies have indicated that the degree of satisfaction of employees’ intrinsic needs is the critical determinant of EX (Plaskoff, 2017; Tucker, 2020; Yohn, 2020). Based on this, we provide a new direction for the literature on EX by introducing SDT into the study of employee well-being. Furthermore, this study echoes the trend of the experience economy era by taking an employee-centered perspective and summarizing the significant needs that employees are concerned about through a rich means of acquiring information.

Second, although several studies have discussed the concept of EX, they are mostly theoretical derivations (Batat, 2022; Itam and Ghosh, 2020; Plaskoff, 2017; Tucker, 2020), which is prone to detach the conceptual development of EX from practice. Through in-depth analysis and integration of relevant literature and practical materials, we clarified the concept of EX and its similarities and differences with similar concepts, and then we comprehensively organized the components of EX. In this regard, the present study helps to reduce the bias of findings and conceptual misunderstanding caused by vague definitions and deepens researchers’ understanding of the components of EX. Furthermore, compared with previous scale development studies (Yadav and Vihari, 2023; Yildiz et al., 2020), the present study not only employed multiple data collection approaches in the qualitative phase but also designed rigorous analytic procedures in the empirical testing phase. Through these efforts, this study helps to provide new research methodologies and technical safeguards for subsequent empirical studies, as well as practical tools and strategies for business managers.

Moreover, most of the previous studies have explored EX in the context of Western culture, ignoring the potential differences in EX in various cultural contexts. It is worth emphasizing that due to differences in cultural systems and economic development, there can be significant differences in the needs of employees in various countries (Fisher and Yuan, 1998). China is not only the country with the largest labor force in the world but also the country with the highest employee turnover rate in Asia (Lee et al., 2018). Therefore, it is an important attempt for us to conduct EX studies in the Chinese context. This study’s findings can contribute to the enrichment of cross-cultural studies of employee well-being and, more importantly, can provide insights for similar developing countries, thus deepening the theoretical discussions on EX.

Practical implications

This study’s findings also have several practical implications. First, through the development of EXS, this study provides a scientific tool for organizations to identify employee needs accurately. Through an in-depth analysis of the content of employees’ reviews of the company, our findings provide a comprehensive picture of employees’ job needs and preferences in the Chinese context. With the help of the scale items developed in this study, managers are able to systematically evaluate the quality of employees’ experiences at different touchpoints and identify weak aspects. For example, if an employee’s score on the professional development dimension is lower, the organization can target and optimize the training system or promotion path. This data-driven decision-making model not only helps to reduce employee turnover but also stimulates organizational identification by satisfying employees’ intrinsic basic psychological needs (for example, autonomy, competence, and relatedness; Deci et al., 2017), which leads to a change from control-based management to experience-based management, and ultimately to an improvement in the employment relationship.

Second, this study provides a direction for Chinese companies to build culturally appropriate management systems. Compared to Western employees, Chinese employees are more sensitive to interpersonal harmony and work-related dimensions due to the intertwining of rapid economic development and collectivist culture. For example, keywords such as colleague relationship and work environment, which appear frequently in online reviews, reflect employees’ expectations of interpersonal relationships and external conditions in the workplace. Therefore, organizations can dynamically adjust their management strategies based on employees’ real-time reviews. For example, improving the comfort of the workplace or retaining the necessary interpersonal interaction scenarios in the digital transformation. In this regard, this study not only helps alleviate the long-standing issue of high turnover rates in Chinese organizations but also can create an experience for employees that matches their needs, ultimately achieving a two-way improvement in organizational resilience and employee well-being.

Furthermore, this study provides a portable framework and methodology for cross-cultural human resource management. We integrated web crawlers, mixed research methods, and measurement invariance tests in the development of EXS, providing a standardized process for multinational corporations to conduct EX management. For example, when entering emerging markets, multinational corporations can refer to the dimensional framework of this study and localize the scale with the local cultural characteristics so as to quickly capture the core needs of employees. Meanwhile, the employee-centered perspective emphasized in this study can help companies carry out experience management throughout the whole cycle from recruitment to exit instead of limiting it to the traditional performance appraisal nodes. In this regard, the ideas in this study can help companies build a flexible human resource system in the context of diversification and then turn EX into a sustainable competitive advantage.

Most importantly, our study is conducive to drawing society’s attention to EX. As we mentioned earlier, there are huge differences in the situation of employees in regions with different development levels. For example, in regions with positive economic development, employees are more likely to focus on higher-level needs such as self-actualization. China is currently in a special period of sustained economic growth, and the contradiction between traditional local culture and rapid economic development tends to make companies neglect employees’ feelings when pursuing development. Therefore, this study starts from an employee-centered perspective and adheres to the employee needs orientation, which is conducive to the construction of an employee-centered mindset in Chinese companies.

Limitations and future directions

This study, like all studies, has several limitations. First, although we obtained abundant materials via web crawling techniques, there are also several drawbacks of online reviews based on the ZHILIAN platform. On the one hand, online reviews are more likely to be manipulated. For example, companies possibly spend money to delete negative reviews or employ paid posters to publish positive reviews. On the other hand, online reviews may also be subject to sample selection bias. It is important to acknowledge that employees who actively write reviews are typically at opposite poles of the experience spectrum: spreading unfavorable statements about the company because they are dissatisfied or glorifying the company because they are satisfied. As a result, online review content may also not fully reflect the normalized experience of the general staff. Second, although the Credamo platform’s paid sample service can improve the efficiency of data collection, the sample provided may not be fully representative of the overall population. For example, online platforms may appeal more to users in specific age groups, income levels, or interest groups. Additionally, participants in paid surveys may be more inclined to provide answers they think the researcher wants to hear rather than what they really think, resulting in response bias. Future research could further enhance the validity of the findings by combining intra-company human resource data, longitudinal tracking designs, and cross-platform data for triangulation verification.

Third, we did not explore the antecedents of EX in this study. In fact, differences in EX are also likely to be closely related to employees’ characteristics. Therefore, future research could further explore the potential triggers that lead employees to have different experiences, such as personality traits. Finally, to enhance the strength and representativeness of the sample, this study conducted surveys in Chinese companies. The scales we developed were also based on employee characteristics in Chinese companies, which possibly limits the generalizability of the findings. We encourage future studies to place EXS in different cultures to validate its cross-cultural validity further and to explore differences in the needs of employees across cultures.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams RB, Licht AN, Sagiv L (2011) Shareholders and stakeholders: how do directors decide? Strategic Manage J 32(12):1331–1355. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.940

Ahmad R, Nawaz MR, Ishaq MI et al. (2023) Social exchange theory: systematic review and future directions. Front Psychol 13:1015921. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015921

Batat W (2022) The employee experience (EMX) framework for well-being: an agenda for the future. Empl Relat 44(5):993–1013. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-03-2022-0133

Brush DH, Moch MK, Pooyan A (1987) Individual demographic differences and job satisfaction. J Organ Behav 8(2):139–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030080205

Carpenter S (2018) Ten steps in scale development and reporting: a guide for researchers. Commun Methods Meas 12(1):25–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1396583

Cook KS, Cheshire C, Rice ERW et al (2013) Social exchange theory. In: DeLamater J, Ward A (eds) Handbook of social psychology. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 61–88 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_3

Cornelius N, Ozturk MB, Pezet E (2022) The experience of work and experiential workers: mainline and critical perspectives on employee experience. Pers Rev 51(2):433–443. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2022-887

Cropanzano R, Anthony EL, Daniels SR et al. (2017) Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad Manag Ann 11(1):479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099

Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM (2017) Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psych 4:19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Del Ponte A, Li L, Ang L et al. (2024) Evaluating SoJump.com as a tool for online behavioral research in China. J Behav Exp Financ 41:100905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2024.100905

Díaz J, Pérez J, Gallardo C et al. (2023) Applying inter-rater reliability and agreement in collaborative grounded theory studies in software engineering. J Syst Software 195:111520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2022.111520

Farndale E, Kelliher C (2013) Implementing performance appraisal: exploring the employee experience. Hum Resour Manage 52(6):879–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21575

Fisher CD, Yuan XY (1998) What motivates employees? A comparison of US and Chinese responses. Int J Hum Resour Man 9(3):516–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851998341053

Gong T, Yi Y (2018) The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychol Market 35(6):427–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21096

Harold CM, Hu B, Koopman J (2022) Employee time theft: conceptualization, measure development, and validation. Pers Psychol 75(2):347–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12477

Ilies R, Judge TA (2004) An experience-sampling measure of job satisfaction and its relationships with affectivity, mood at work, job beliefs, and general job satisfaction. Eur J Work Organ Psy 13(3):367–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320444000137

Itam U, Ghosh N (2020) Employee experience management: a new paradigm shift in HR thinking. Int J Hum Cap Inf Te 11(2):39–49. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJHCITP.2020040103

Jain R, Aagja J, Bagdare S (2017) Customer experience–a review and research agenda. J Serv Theor Pract 27(3):642–662. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-03-2015-0064

Klotz AC, Swider BW, Kwon SH (2023) Back-translation practices in organizational research: avoiding loss in translation. J Appl Psychol 108(5):699–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001050

Krippendorff K (2018) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Lee J, Chiang FFT, van Esch E et al. (2018) Why and when organizational culture fosters affective commitment among knowledge workers: the mediating role of perceived psychological contract fulfilment and moderating role of organizational tenure. Int J Hum Resour Man 29(6):1178–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1194870

Lee M, Kim B (2023) Effect of employee experience on organizational commitment: case of South Korea. Behav Sci 13(7):521. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13070521

Lemon LL (2019) The employee experience: how employees make meaning of employee engagement. J Public Relat Res 31(5–6):176–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2019.1704288

Li X, Yang P (2023) Facilitate or diminish? Mechanisms of perceived organizational support on employee experience of new generation employees. Psychol Rep. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231183621

Malik A, Budhwar P, Mohan H et al. (2023) Employee experience–the missing link for engaging employees: insights from an MNE’s AI-based HR ecosystem. Hum Resour Manage 62(1):97–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22133

Marzi G, Balzano M, Marchiori D (2024) K-Alpha calculator–krippendorff’s alpha calculator: a user-friendly tool for computing krippendorff’s alpha inter-rater reliability coefficient. MethodsX 12:102545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2023.102545

Maylett T, Wride M (2017) The employee experience: how to attract talent, retain top performers, and drive results. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

McCallum S, Haar J, Myers B (2024) Enhancing the employee experience: exploring a global positive climate to influence key employee outcomes. Evid Based HRM 12(2):387–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-03-2022-0070

Morgado FFR, Meireles JFF, Neves CM et al. (2018) Scale development: ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicol-Reflex Crit 30:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

Nie P, Ding L, Sousa-Poza A (2020) What Chinese workers value: an analysis of job satisfaction, job expectations, and labor turnover in China. Prague Econ Pap 29(1):85–104. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.pep.726

Plaskoff J (2017) Employee experience: the new human resource management approach. Strateg HR Rev 16(3):136–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-12-2016-0108

Rao MS (2017) Employees first, customers second and shareholders third? Towards a modern HR philosophy. Hum Resour Manage Int Digest 25(6):6–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-02-2017-0023

Roald J, Edgren L (2001) Employee experience of structural change in two Norwegian hospitals. Int J Health Plan M 16(4):311–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.643

Saks AM (2006) Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J Manage Psychol 21(7):600–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690169

Saks AM (2019) Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. J Organ Eff-People P 6(1):19–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-06-2018-0034

Scott CR, Connaughton SL, Diaz-Saenz HR et al. (1999) The impacts of communication and multiple identifications on intent to leave: a multimethodological exploration. Manage Commun Q 12(3):400–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318999123002

Silvestro R (2002) Dispelling the modern myth: employee satisfaction and loyalty drive service profitability. Int J Oper Prod Man 22(1):30–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570210412060

Smidts A, Pruyn ATH, van Riel CBM (2001) The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad Manage J 44(5):1051–1062. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069448

Stamolampros P, Korfiatis N, Chalvatzis K et al. (2019) Job satisfaction and employee turnover determinants in high contact services: insights from employees’ online reviews. Tourism Manage 75:130–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.030

Tsui AS, Egan TD, O’Reilly CA (1992) Being different: relational demography and organizational attachment. Admin Sci Quart 37(4):549–579. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393472

Tucker E (2020) Driving engagement with the employee experience. Strateg HR Rev 19(4):183–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-03-2020-0023

Veloso CM, Sousa B, Au-Yong-Oliveira M et al. (2021) Boosters of satisfaction, performance and employee loyalty: application to a recruitment and outsourcing information technology organization. J Organ Change Manag 34(5):1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-01-2021-0015

Walker D, Myrick F (2006) Grounded theory: an exploration of process and procedure. Qual Health Res 16(4):547–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285972

Ward MK, Meade AW (2023) Dealing with careless responding in survey data: prevention, identification, and recommended best practices. Annu Rev Psychol 74:577–596. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-040422-045007

Yadav M, Vihari NS (2023) Employee experience: construct clarification, conceptualization and validation of a new scale. FIIB Bus Rev 12(3):328–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145211012501

Yang CC, Chen HT, Luo KH et al. (2024) The validation of Chinese version of workplace PERMA-profiler and the association between workplace well-being and fatigue. BMC Public Health 24:720. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18194-6

Yildiz D, Temur GT, Beskese A et al. (2020) Evaluation of positive employee experience using hesitant fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. J Intell Fuzzy Syst 38(1):1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-179467

Yohn DL (2020) Brand authenticity, employee experience and corporate citizenship priorities in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Strateg Leadership 48(5):33–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-06-2020-0077

Zhang X, Kaiser M, Nie P et al. (2019) Why are Chinese workers so unhappy? A comparative cross-national analysis of job satisfaction, job expectations, and job attributes. PLoS ONE 14(9):e0222715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222715

Zheng X, Zhu W, Zhao H et al. (2015) Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J Organ Behav 36(5):621–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1990

ZHILIAN (2023) Top employers of the year 2023. https://best.zhaopin.com/#/bestemployer. Accessed 9 Mar 2025

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72071124), the Postgraduate Education Innovation Program of Shanxi Province (2024KY042), the Graduate Education Reform Project of Henan Province (2023SJGLX011Y) and the Graduate Education and Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project of Henan University (YJSJG2023XJ001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. SZ: Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study adhere to the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. According to the Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Beings (https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm) promulgated by China (Article 32: Research that does not cause harm to humans, and does not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests can be exempted from ethical review), the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the School of Economics and Management, Shanxi University, confirmed the exemption. Specifically, this study does not involve special categories such as minors, individuals with disabilities, prisoners, or other vulnerable populations, and the questions in the questionnaire have no adverse effects on the mental health status of the respondents. Furthermore, this study uses anonymized data to conduct studies, causes no harm to the human body, and involves neither sensitive personal information nor commercial interests. Therefore, this study was reviewed and granted exemption from ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Economics and Management, Shanxi University on October 10, 2023 (no exemption number was issued).

Informed consent