Abstract

Product-harm crises can be categorized into two types on the basis of the number of enterprises involved: single-enterprise and group product-harm crises. Although the incidence of group product-harm crises is increasing, prior research has focused predominantly on single-enterprise product-harm crises, with limited attention paid to group product-harm crises, particularly their impact. This study aims to examine how a product-harm crises influence consumer boycott behaviour by investigating the mediating role of blame attribution and perceived betrayal, as well as the moderating role of social distance. Through a scenario-based experimental survey, three studies were conducted, collecting a total of 726 samples to test the hypotheses. The results indicate that consumers exhibit stronger boycott intentions in response to group product-harm crises than in response to single-enterprise product-harm crises. Crucially, this effect is mediated by blame attribution and perceived betrayal. Additionally, social distance moderates the relationships between product-harm crises and consumer boycotts, perceived betrayal, and blame attribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Product-harm crises often involve multiple brands or enterprises within an industry (Li et al. 2019). China’s 2008 melamine-contaminated milk powder crisis, which involved 22 dairy enterprises, is a prominent example (Li et al. 2019). Scholars (e.g., Cui and Yu, 2015; Li et al. 2019; Li and Zhao, 2024; Ursula and Bodo, 2013; Wang et al. 2012) have termed such incidents group product-harm crises, distinguishing them from single-enterprise product-harm crises, where only one enterprise is involved.

Although the topic of group product-harm crises is important, research on this phenomenon remains limited, particularly with respect to its impact (Li et al. 2019). Previous studies (e.g., Su et al. 2022; Yu et al. 2020) have demonstrated that negative events can trigger consumer boycotts. However, existing research has not sufficiently examined the underlying mechanisms through which different product-harm crises influence consumer boycott behaviour. To address this gap, the current study investigates these mechanisms by analysing consumer responses from both the emotional and cognitive perspectives.

Previous research has identified perceived betrayal as a critical emotional response following a product–harm crisis (Yalin and Min, 2022). This response can trigger additional negative emotions (e.g., anger, frustration, disappointment) and subsequent behavioural consequences (Lee and Selart, 2015; Rasouli et al. 2023). Compared with other emotional reactions, perceived betrayal more effectively captures the core emotional response to product-harm crises. However, existing studies have largely overlooked the role of perceived betrayal in influencing consumer boycott behaviour. To address this gap, the current study adopts perceived betrayal as the key emotional factor in examining how product-harm crises affect consumer boycotts.

Attribution refers to the cognitive process through which individuals interpret the causes of observable events (Kelley and Michela, 1980). When a crisis occurs, consumers naturally engage in attribution processes to make sense of the situation (Hegner et al. 2018; Isiksal and Karaosmanoglu, 2020; Septianto and Kwon, 2021). While numerous studies on product-harm crises have demonstrated that crisis-related information can shape cognitive responses through blame attribution (Carvalho et al. 2015; Cleeren et al. 2013; Xie and Keh, 2016), existing research has paid little attention to how individuals attribute blame specifically in the context of group product-harm crises. Therefore, the present study examines blame attribution as a cognitive factor that mediates the relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycott behaviour.

Consumer responses to crises vary significantly (Lee et al. 2021), as individuals perceive the psychological proximity of crises differently—some may view a crisis as being close to them, whereas others may consider it far away (Lee et al. 2021). According to construal level theory (CLT; Liberman et al. 2007), individuals assess events on the basis of psychological distance (Willems et al. 2017). CLT posits that the mental construal level of crisis-related information depends on one’s perceived psychological distance from the event (Huang and Ki, 2023). This distance, along with the associated construal level, ultimately shapes an individual’s evaluation, attitudes, and behavioural responses (Lee et al. 2021; Trope et al. 2007). However, no prior research has examined whether psychological distance moderates the relationship between product-harm crises and consumer reactions. To fill this gap, this study introduces psychological distance—specifically, social distance—as a moderator and investigates its role in shaping the impact of product-harm crises on consumer responses.

In summary, further investigation into the emotional and cognitive mechanisms underlying consumer boycotts—particularly in the context of product-harm crises—is warranted. To address this need, the present study makes three key contributions. First, it examines how different product-harm crises (single-enterprise product-harm crises vs. group product-harm crises) influence consumer boycott behaviour. Second, it explains the mediating roles of blame attribution (cognitive mechanism) and perceived betrayal (emotional mechanism) in this relationship. Third, it investigates whether psychological distance—specifically social distance—moderates the effects on consumer boycotts and their underlying cognitive and emotional responses.

Literature review and theoretical background

Product-harm crises

“Product-harm crises are discrete, unplanned, and well-publicized events involving defective and/or dangerous products” (Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994). In recent years, the Samsung smartphone battery explosion event has been a prominent example of a product-harm crisis (Lee et al. 2021; Yuan et al. 2020). A product-harm crisis generates significant negative consequences that extend beyond consumers to affect multiple stakeholders. These impacts include harm to the general public (Siomkos and Kurzbard, 1994), disruption to related industries (Hua et al. 2021), and adverse effects on various stakeholders (Hsu and Cheng, 2018), such as supply chain members (Tu et al. 2024).

Scholars have classified product-harm crises from multiple perspectives. For example, Ursula and Bodo (2013) created a category for situations where many enterprises are involved in a crisis simultaneously, such as China’s “baby milk powder scandal”. Other researchers (e.g., Li et al. 2019; Li and Zhao, 2024; Ren and Jing, 2013; Wang et al. 2012) have developed a binary classification system: single-enterprise product-harm crises (involving one violating enterprise within an industry) versus group (or industry) product-harm crises (involving two or more violating enterprises within an industry). Building on this literature, the current study defines a group product-harm crisis as an incident where products manufactured by multiple, potentially all, enterprises within an industry were found to be defective or harmful to consumers owing to the same underlying cause. This emphasis on a common cause is crucial, as situations where multiple enterprises experience product-harm crises for different reasons merely represent concurrent single-enterprise product-harm crises rather than a true group product-harm crisis (Cui and Yu, 2015).

Over the past three decades, the number of product-harm crises, particularly group product-harm crises, has risen significantly (Cleeren et al. 2013; Crouch et al. 2021; Li et al. 2019; Yalin and Min, 2022), making the analysis of their impacts increasingly critical. Despite their growing prevalence and importance, academic research has disproportionately focused on single-enterprise product-harm crises (Cleeren et al. 2017), leaving group product-harm crises substantially underexplored (Li et al. 2019). Given that different crises elicit distinct consumer responses (Baghi and Gabrielli, 2021; Nadeau et al. 2020), this gap in the literature is particularly noteworthy, as consumer reactions to group product-harm crises remain poorly understood. To fill this research gap, the present study specifically examines the impacts of group product-harm crises on consumer behaviour.

Consumer boycotts

A consumer boycott is defined as “a voluntary and deliberate abstention by consumers from purchasing, using, or dealing with a specific target, such as a product, organization, country, or even person, to achieve a certain objective” (Kim et al. 2022), and consumer boycotts have become an effective form of consumer activism (Ning et al. 2024). Existing research has identified diverse antecedents and motivations underlying consumer boycotts (Ning et al. 2024). For example, Zeng et al. (2021) categorized these driving factors into internal and external dimensions. Internal factors primarily pertain to psychological triggers, such as perceived betrayal (Yu et al. 2020), whereas external factors typically involve substantiated evidence of an organization’s unethical conduct (Klein et al. 2004). Empirical studies further demonstrate that corporate unethical behaviour serves as a critical catalyst for consumer boycotts (Ulker-Demirel et al. 2021). Specifically, when enterprises engage in egregious misconduct that inflicts tangible harm on consumers, such actions frequently precipitate widespread boycott initiatives (Klein et al. 2004; Park and Park, 2018). Notably, while product-harm crises are recognized as potential triggers for consumer boycott, the precise mechanisms through which such crises mobilize collective consumer resistance remain underexplored in the literature.

AEB model

The awareness-perceived egregiousness-boycott (AEB) model (Klein et al. 2004) posits that a consumer boycott unfolds through a sequential process: individuals first become aware (A) of an enterprise’s misconduct, subsequently assess its perceived egregiousness (E), and ultimately decide whether to boycott (B). Within this framework, perceived egregiousness serves as an important variable that triggers a consumer boycott (Klein et al. 2004), and the impact of an individual’s awareness on boycotting is mediated by perceived egregiousness (Su et al. 2022). Specifically, individuals are more likely to boycott when they perceive an enterprise’s actions as morally reprehensible and harmful to others (Su et al. 2022).

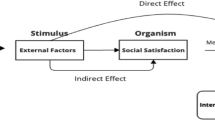

Negative events involving enterprises, such as a product-harm crisis, can amplify perceptions of egregiousness, eliciting strong negative emotional reactions that drive boycott behaviour (Makarem and Jae, 2016; Su et al. 2022). Empirical research has consistently validated the explanatory power of the AEB model in boycott contexts (He et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2021). Following a product-harm crisis, individuals typically progress through three distinct stages: they first gain awareness of the incident (A), then evaluate the egregiousness of the misconduct (E), and finally make boycott decisions (B) on the basis of this assessment. This sequential process demonstrates the applicability of the AEB framework in explaining boycott behaviour in product-harm crisis scenarios, making it an appropriate theoretical lens for the current investigation. While existing research has established that perceived egregiousness encompasses both affective and cognitive components (Lasarov et al. 2023), prior applications of the AEB model have predominantly emphasized emotional dimensions, particularly perceived betrayal (Su et al. 2022) and anger (Lasarov et al. 2023). To correct this theoretical imbalance, the present study extends the AEB framework by incorporating both emotional (perceived betrayal) and cognitive (blame attribution) factors. This research proposes that when a product-harm crisis occurs, consumers first become aware of the crisis and then judge whether the crisis was egregious, resulting in different emotions (perceived betrayal) and cognitions (blame attribution), which can lead to a boycott.

Blame attribution

Attribution theory examines how individuals explain the causes of specific events or outcomes (Weiner, 2000). It has become one of the most frequently adopted theoretical frameworks (Cleeren et al. 2017) for explaining an individual’s emotional and behavioural tendencies towards a crisis (Chung and Lee, 2021). The extent to which consumers attribute crisis responsibility to an enterprise significantly influences their attitudes and subsequent behavioural intentions (Aljarah et al. 2022; Chung and Lee, 2021; Kim and Woo, 2019). Antonetti and Maklan (2016) identified three sequential stages in consumer crisis response: crisis attribution, emotional responses, and behavioural intentions. Different attribution patterns generate distinct emotional responses, including anger and resentment (Fediuk et al. 2010), and they may even lead to retaliatory actions such as boycotts (Heijnen and van der Made, 2012; Kang et al. 2023). When confronting a product-harm crisis, consumers typically follow an “attribution-emotions-boycott intentions” decision-making process (Shim et al. 2021). Therefore, incorporating blame attribution as a cognitive component into the AEB model demonstrates both logical consistency and theoretical validity.

Perceived betrayal

Perceived betrayal is the psychological response triggered by the misconduct of interacting parties (Ward and Ostrom, 2006). It reflects the extent to which consumers perceive a violation of established relational norms by an enterprise (Grégoire and Fisher, 2008; Koehler and Gershoff, 2003). This emotion arises when individuals believe that relational expectations have been breached (Grégoire and Fisher, 2008) or when brands fail to deliver promised product benefits, leading to consumer disappointment (Lee et al. 2020; Reimann et al. 2018). The consequences of perceived betrayal are severe, often manifesting as anger, hatred (Tan et al. 2019), and extreme behavioural reactions such as vindictive complaints (Hutzinger and Weitzl, 2023) or retaliatory actions (Temessek Behi et al. 2024). Despite its significant impact, betrayal remains an understudied phenomenon in consumer research (Leonidou et al. 2018). However, recent studies (e.g., Gerrath et al. 2023; Yalın and Min, 2022; Ma, 2018; Rasouli et al. 2022; Su et al. 2022) have increasingly adopted perceived betrayal as a key mediator to explain how negative events influence consumer behaviour. Given its theoretical and practical relevance, this study integrates perceived betrayal as a critical emotional factor within the research framework.

Social distance

Social distance, which is a dimension of psychological distance, describes the degree of closeness between individuals and reflects the similarity and familiarity between the self and others (Liberman and Trope, 2014; Trope and Liberman, 2010). Empirical evidence suggests that psychological distance significantly influences consumers’ risk perceptions and subsequent behavioural intentions (Fuchs et al. 2024). While prior research has examined the role of psychological distance in crisis contexts—including temporal distance (Kim et al. 2020) and spatial distance (Chen et al. 2020)—the specific impact of social distance on consumer responses to product-harm crises remains unexplored. To fill this gap, the present study investigates the moderating role of social distance.

Hypothesis development

The relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycotts

An enterprise’s unethical behaviour directly shapes consumers’ attitudes and behaviours (Zhai et al. 2019), often inciting retaliatory actions such as boycotts (Delistavrou et al. 2020; Grégoire and Fisher, 2008; Yu et al. 2020). According to the AEB model, a consumer boycott is driven by perceived egregiousness (Wang et al. 2018). This perception intensifies with the severity of the unethical act (Wang et al. 2018), making it a critical predictor of boycott participation (Ulker-Demirel et al. 2021). Empirical evidence suggests that egregious violations are particularly likely to provoke a boycott (Wang et al. 2018), and the more egregious an enterprise’s behaviour is, the greater the likelihood of consumers participating in the boycott (Barakat and Moussa, 2017).

Compared with a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, a group product-harm crisis tends to have more severe consequences and broader societal impacts (Cui and Yu, 2015). Such crises not only damage the enterprises involved (Li and Zhao, 2024) but also ripple across the entire industry (Hansen, 2012) and even undermine trust in regulatory institutions (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Li and Zhao, 2024). Consequently, a group product-harm crisis will trigger consumers to have a greater sense of the egregiousness of enterprise behaviour. Additionally, when they face a group product-harm crisis, consumers’ perception of egregiousness is stronger, leading to a greater likelihood of boycotting. Empirical studies (e.g., Barakat and Moussa, 2017; Lasarov et al. 2023; Ulker-Demirel et al. 2021) support this reasoning. On the basis of the analysis above, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Consumers are more likely to participate in a boycott when facing a group product-harm crisis than when facing a single-enterprise product-harm crisis.

The mediating role of perceived betrayal

According to the AEB model, individuals typically become aware of enterprise behaviour, judge whether the behaviour is egregious, and then decide whether to boycott the enterprise (Klein et al. 2004; Su et al. 2022). Crucially, the perceived egregiousness and emotional reactions elicited by negative events may differ significantly depending on context (Su et al. 2022). According to associative network theory (Bower, 1981), during a group product-harm crisis, consumers are exposed to a large amount of negative information about the crisis in the industry, and they activate the information node of the negative evaluation of enterprises in the industry and form a negative view of the whole industry. This reinforces consumers’ perceptions of crisis severity, leading to heightened judgements of egregiousness and, consequently, intensified feelings of betrayal. In contrast, during a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, consumers do not form a negative assessment of the entire industry, thus attenuating perceived egregiousness and subsequent perceived betrayal. A product-harm crisis constitutes a violation of the psychological contract between enterprises and consumers (Ward and Ostrom, 2006), evoking perceived betrayal and often prompting retaliatory actions (Strizhakova et al. 2012). In this context, a consumer boycott represents a coping mechanism through which individuals seek psychological relief by expressing negative emotions (Kozinets and Handelman, 2004). Thus, when confronted with betrayal stemming from a product-harm crisis, consumers frequently resort to retaliatory measures (Romani et al. 2013), including boycotting the enterprise (Heijnen and van der Made, 2012; Su et al. 2022), to calm their negative emotions.

Furthermore, grounded in equity theory and justice-based theory (Grégoire and Fisher, 2008), a product-harm crisis represents a fundamental violation of relational fairness between consumers and enterprises (Nguyen et al. 2018), which makes consumers feel betrayed (Koehler and Gershoff, 2003), subsequently triggering retaliatory responses such as vindictive complaints (Temessek Behi et al. 2024) to restore fairness and justice. These theoretical perspectives jointly suggest that the severity of enterprise violations directly amplifies perceived betrayal (based on equity theory), forming attitudes and behaviours that are detrimental to enterprises (based on justice-based theory). Building upon this theoretical foundation, we propose that different product-harm crises elicit varying degrees of perceived betrayal, which in turn differentially influences boycott intentions. Specifically, perceived betrayal serves as a key mediating mechanism linking product-harm crises to consumer boycotting. This proposition aligns with established empirical findings (e.g., Duman and Özgen, 2018; Su et al. 2022) demonstrating the mediating role of perceived betrayal in transforming negative events into punitive consumer actions. On the basis of the analysis above, the authors formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived betrayal mediates the relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycotts.

The mediating role of blame attribution

When confronted with egregious corporate behaviour, individuals tend to clarify why it occurred, which institutions or individuals caused it to occur (Cheng et al. 2017), and who is responsible for it (Hong and Shim, 2023). This evaluative process, known as blame attribution (Antonetti and Maklan, 2016), represents a fundamental psychological mechanism that shapes consumer responses to corporate crises (Wang et al. 2023). Research has demonstrated that consumers spontaneously generate causal attributions when processing crisis information, with a particular emphasis on identifying blameworthy parties (Isiksal and Karaosmanoglu, 2020; Septianto and Kwon, 2021). This attribution process serves not only to comprehend a negative event but also, more critically, to establish accountability for the transgression.

Empirical research has demonstrated a significant relationship between crisis severity and blame attribution (Antonetti and Maklan, 2016). Specifically, blame attribution is directly proportional to the severity of a crisis (Gilbert, 2022). The more severe a crisis is, the more an individual believes that the organization involved should take responsibility (Coombs, 2006; Coombs and Schmidt, 2000). Moreover, individuals generally attribute more blame to perpetrators as the severity of the consequences increases (Zhou and Ki, 2018). This pattern is particularly evident in product-harm crises, where Laufer et al. (2005) established that consumers attributed greater blame to enterprises as crisis severity increased. Relative to a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, a group product-harm crisis typically presents multiple characteristics, such as complicity, deliberation, and seriousness (Cui and Yu, 2015). Thus, when facing a group product-harm crisis, consumers may attribute more blame to the enterprises involved. When only one enterprise in an industry experiences a product-harm crisis, consumers may believe that the crisis occurred by chance, linking the causes of the crisis to factors outside the enterprise and thus reducing the blame placed on the enterprise. However, when facing a group product-harm crisis involving many enterprises, consumers have sufficient reason to believe that the factors of the enterprises themselves are the main cause of the crisis and that the enterprises should be blamed for it.

Research has shown that the degree to which consumers attribute the cause of a crisis to an enterprise significantly influences their attitudes and subsequent behavioural intentions (Aljarah et al. 2022; Chung and Lee, 2021; Kim and Woo, 2019). Blame attribution has serious consequences for an enterprise because it can cause negative word of mouth, decrease purchase intentions (Cleeren et al. 2013), and even trigger retaliatory actions (Weiner, 2006). The more that consumers attribute crisis responsibility to a certain brand/enterprise, the greater the degree to which they lose faith in that brand/enterprise (Klein and Dawar, 2004; Whelan and Dawar, 2016) and even develop intentions to boycott it.

The preceding analysis demonstrates that varying types of product-harm crises (single-enterprise vs. group) elicit differential perceptions of severity and egregiousness, which in turn lead to distinct patterns of blame attribution. These attribution differences ultimately trigger varying degrees of punitive consumer responses, particularly boycott behaviour. Building upon this theoretical foundation, this paper infers that different product-harm crises affect consumer boycotts through blame attribution. The authors formulate the following hypothesis:

H3: Blame attribution mediates the relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycotts.

The moderating role of social distance

The heuristic-systematic model posits that individuals employ both heuristic and systematic models to process information (Xie et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2020). Specifically, the systematic model relies on considerable cognitive effort to evaluate the content and effectiveness of information (Xie et al. 2023). In contrast, the heuristic model depends on external cues or easily available information to decide whether to accept the message (Xie et al. 2023).

Building on Wang et al.’s (2020) findings, we note that individuals employ distinct information processing modes depending on their perceived social distance from the product-harm crisis. Those perceiving a far social distance tend to process information heuristically, whereas those perceiving a close social distance tend to process information systematically. This distinction aligns with CLT, which posits that high-level construal representations of a product-harm crisis emphasize superordinate features and primary characteristics (Chen et al. 2020). Consequently, individuals with a far social distance focus on primary characteristics such as the number of implicated enterprises (Yalin and Min, 2022) while often overlooking specific details and secondary characteristics (Chen et al. 2020). The number of involved enterprises serves as a salient heuristic cue that significantly influences consumer judgements (Yalin and Min, 2022). In contrast, consumers employing low-level construal are more concerned with the incidental characteristics of the scandalized enterprises (Chen et al. 2020; Trump and Newman, 2017). Therefore, when consumers regard a crisis as being closer to them, they are more inclined to use the systematic information processing model, which requires greater cognitive resources and time investment to understand the information (Wang et al. 2020).

When an enterprise’s unethical behaviour harms consumers’ good friends (close social distance), the emotional factor dominates other factors in the consumers’ evaluation of the enterprise. This close social distance strengthens the relationship between consumers and the crisis and increases the impact of the crisis on consumers (Huang et al. 2011), leading to strong negative evaluations regardless of the number of enterprises involved in the crisis. In short, a close social distance alleviates the influence of the number of enterprises involved in a crisis on perceived betrayal and blame attribution because of the improved relevance between consumers and the crisis. Simultaneously, a close social distance between consumers and a crisis also reduces the impact of the number of enterprises involved in the crisis on consumers’ perceived egregiousness of the crisis, which affects consumer boycotts. Thus, consumers’ blame attributions, perceived betrayal, and consumer boycott intentions caused by a product-harm crisis do not vary significantly under different product-harm crises in the context of a close social distance. Therefore, we develop the following hypotheses:

H4a: Social distance moderates the effect of a product-harm crisis on consumer boycott intentions, such that a group product-harm crisis (vs. a single-enterprise crisis) elicits stronger boycott intentions only when consumers perceive the crisis as being far from them.

H4b: Social distance moderates the effect of a product-harm crisis on perceived betrayal such that a group product-harm crisis (vs. a single-enterprise crisis) generates greater perceived betrayal only when consumers perceive the crisis as being far from them.

H4c: Social distance moderates the effect of a product-harm crisis on blame attribution such that a group product-harm crisis (vs. a single-enterprise crisis) results in stronger blame attribution to the enterprise only when consumers perceive the crisis as being far from them.

Research overview

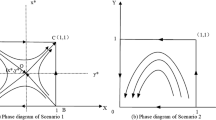

The present study constructed a model (see Fig. 1) and analysed the relationships among different variables through three studies (see Table 1). Study 1 examined the direct effect of a product-harm crisis on consumer boycotts, testing H1 via a sample of college students. H2 to H3 were tested in Study 2 with more diverse and representative samples to verify the mediating role of perceived betrayal and blame attribution. Study 3 used real enterprise(s) for data collection to validate the hypotheses proposed in this study (H1-H4) to improve the effectiveness of the research conclusions.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 was to verify the impact of a product-harm crisis on consumer boycotts (H1) using the college student samples. This initial investigation served to establish the foundational relationship between crises and punitive consumer responses (i.e., consumer boycotts) while maintaining high internal validity through standardized experimental conditions.

Method

Design

We used a between-subjects experimental design that manipulated the product-harm crises at two levels: single-enterprise product-harm crises vs. group product-harm crises. Referring to the manipulation methods of Cui et al. (2019) and Li et al. (2019) for group and single-enterprise product-harm crises, experimental materials were developed for this study, and they were presented in the form of news reports (see Appendix 1).

Procedure

The first step was to identify the subjects, and the second step was to randomly assign the subjects to different scenarios after stating the research ethics statement and obtaining their informed consent. In the third step, the participants were required to read background material containing a product-harm crisis and to complete corresponding questionnaires, including consumer boycotts and personal information, on the basis of their own judgement. Finally, we retrieved the questionnaires and expressed our gratitude.

Measures

This study adapted a questionnaire from the literature to improve content validity. Responses were collected with the help of a 7-point Likert scale anchored from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.” Consumer boycott intentions were measured using three items adapted from Duman and Özgen (2018) and Cossío-Silva et al. (2019). Sample items include “Buying a product of enterprise A is not an alternative for me” (in the situation of a single-enterprise product-harm crisis) and “Buying a product of these enterprises is not an alternative for me” (in the situation of a group product-harm crisis).

Participants and sampling

The data for this study were collected through questionnaires. Calder and Tybout (1999) noted that when studies focus on the causal relationship between variables, college students can be used as subjects for the sake of sample homogeneity. To minimize the influence of exogenous variables, ensure strong internal validity, and facilitate participant recruitment, this study adopted a college student sample. Notably, in product-harm crisis research, scholars such as Cui et al. (2019) and Yalin and Min (2022) have similarly utilized college student samples. Considering the convenience and ease of sample acquisition, this study adopted a convenience sampling method to conduct a survey at a university in Wuhan, China. This study was approved by the ethics committee and met ethical standards. Before completing the questionnaire, the participants were briefed on the purpose of the study. After ensuring anonymity and confirming that the responses would be used solely for academic purposes, all participants provided informed consent and voluntarily took part in the survey.

Prior to data collection, G*Power 3.1 software was used to estimate the sample size required for this research (Faul et al. 2007). Under conditions where a medium effect size=0.25, α = 0.05, and β = 0.20, this study required a minimum of 128 participants, with 64 participants in each group. The final sample comprised 194 undergraduate students (male = 49.00%, female = 51.00%; Mage = 21.63, SDage = 2.13; Nsingle-enterprsie = 95, Ngroup = 99).

Results

Reliability

A reliability test was carried out by analysing Cronbach’s α. The analysis revealed that the α (α = 0.839) of the consumer boycott measurement scale exceeded the critical value of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978), and the scale had high reliability.

Hypothesis test

A one-way analysis of covariance was used to examine H1. As predicted, the participants facing a group product-harm crisis expressed stronger boycott intentions (Mgroup = 4.791, SD = 0.742) than did those facing a single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Msingle-enterprsie = 4.060, SD = 0.784) (F(1.193) = 44.609, p < 0.000), confirming H1.

Discussion

Study 1 examined the impact of product-harm crises on consumer boycotts, finding that a product-harm crisis had a greater negative effect on consumer boycott intentions than did a single-enterprise product-harm crisis. However, this study had two limitations. First, while this study identified only the direct effects of different product-harm crises on consumer boycotts, it did not explore the underlying mediating mechanisms driving this relationship. Second, the reliance on college student samples may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader consumer populations. To address these limitations, Study 2 was designed to provide a more comprehensive examination of the phenomenon.

Study 2

Study 2 attempted to test and verify the results of Study 1 by employing a more diverse sample and introducing new experimental stimuli (see Appendix 2). Crucially, this study further examined the underlying psychological mechanisms by investigating the mediating roles of blame attribution and perceived betrayal. The experimental procedure remained consistent with that of Study 1 to ensure methodological comparability.

Method

Measures

The authors adapted questionnaire items from the literature to improve content validity. All the items were measured with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”.

Blame attribution was measured using three items adapted from Klein and Dawar (2004) and Malhotra and Kuo (2009). Sample items included “Enterprise A should be blamed for the crisis” (in the situation of a single-enterprise product-harm crisis) or “These enterprises should be blamed for the crisis” (in the situation of a group product-harm crisis).

Perceived betrayal was measured using three items adapted from Reimann et al. (2018), such as “I felt betrayed by enterprise A” (in the situation of a single-enterprise product-harm crisis) and “I felt betrayed by the enterprises” (in the situation of a group product-harm crisis).

Consumer boycotts. Consumer boycott intentions were measured using three items adapted from Duman and Özgen (2018) and Cossío-Silva et al. (2019); these were the same as the measurement scale used in Study 1.

Participants and sampling

To improve the generalizability of our findings, Study 2 employed a more diverse population sample. Specifically, the research team conducted intercept surveys at high-traffic public locations across Wuhan, China, including shopping malls, urban parks and other densely populated public spaces. The researchers applied a 1:5 intercept ratio (approaching every fifth passerby) to ensure sample randomness while maintaining efficient data collection. If the intercepted persons were willing to participate in the study, they were randomly assigned to different scenarios to complete the data collection.

Similarly, G*Power 3.1 software (Faul et al. 2007) was used to determine the appropriate sample size. The analysis revealed that this study required a minimum of 128 participants, with 64 participants in each group under conditions where a medium effect size = 0.25, α = 0.05, and β = 0.20. A total of 188 valid samples were collected in this study, which exceeded the minimum requirement. The subjects were randomly assigned to one of the two scenarios (Nsingle-enterprsie = 93, Ngroup = 95). Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Results

Reliability and validity

Scale reliability was evaluated through Cronbach’s α analysis. The results revealed excellent internal consistency across all measures, with coefficients surpassing the critical value of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978) (blame attribution: α = 0.820; perceived betrayal: α = 0.836; consumer boycott α = 0.779). The scales had high reliability.

Validity was determined by analysing item reliability, composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al. 2011). All validity indicators met the established standards: item reliability (SMC > 0.50), composite reliability (CR > 0.7), convergent validity (AVE > 0.5), and discriminant validity (the square root of the AVE was larger than the respective correlation with other variables). As presented in Tables 3 and 4, these results collectively demonstrated strong measurement validity for all study constructs.

Hypothesis test

To test H1, we conducted a one-way analysis of covariance. The analysis revealed a statistically significant main effect of the product-harm crisis on consumer boycott intentions (F(1.187) = 41.452, p < 0.000). The participants exposed to the group product-harm crisis reported significantly stronger boycott intentions (Mgroup = 4.968, SD = 0.647) than did those exposed to the single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Msingle-enterprsie = 4.351, SD = 0.667). These findings support H1, demonstrating that a group product-harm crisis elicited more pronounced consumer boycott responses in our expanded sample.

The bootstrapping method was used to examine the mediating effect of blame attribution and perceived betrayal. A 95% confidence interval (CI) of the parameter estimates was acquired by bootstrapping where the samples were run 5000 times. After controlling for the participants’ demographic characteristics, the analysis revealed that blame attribution (β = 0.558, SE = 0.102; not including zero at 95% CI: 0.361 to 0.762) and perceived betrayal (β = 0.482, SE = 0.075; not including zero at 95% CI: 0.342 to 0.632) played a mediating role. These results provide robust support for H2 and H3, demonstrating that both blame attribution and perceived betrayal serve as important psychological mechanisms underlying consumer boycotting.

Discussion

Study 2 employed an expanded sample and new experimental materials to replicate and extend the findings of Study 1. The results consistently demonstrated that a product-harm crisis significantly influenced consumer boycott intentions (H1), and this relationship was mediated by both perceived betrayal (H2) and blame attribution (H3). These findings establish dual psychological pathways through which product-harm crises affect consumer boycotting. While Studies 1 and 2 successfully explained the underlying mechanisms, they did not examine potential boundary conditions. To address this limitation, Study 3 was designed to investigate the moderating role of social distance. Additionally, recognizing that the use of fictional enterprises in Study 1 and Study 2—although methodologically common in prior research—might influence consumer responses, Study 3 incorporated real enterprises to increase validity and strengthen the practical implications of our findings.

Study 3

This study employed actual enterprises in its experimental design to increase validity and mitigate potential biases associated with fictional enterprises. By utilizing real-world cases rather than fictional stimuli, we sought to increase the authenticity of consumer responses, improve the generalizability of the findings, and strengthen the practical implications of our results for business management and policy-making.

Method

Pretest

A pretest was conducted to validate the social distance manipulation. Following Huang et al.’s (2011) methodology, 60 undergraduate participants evaluated two product-harm crisis scenarios differing only in victim identity: close friends versus strangers. The participants responded to the item “Do you feel that the crisis is close to you?” (1 = very close, 7 = very distant). The results demonstrated a significant manipulation effect (t(58) = 19.081, p < 0.05), with the friend condition being perceived as having a closer social distance (Mfriend = 1.800, SD = 0.664) than the stranger condition (Mstranger = 5.230, SD = 0.728). The results show that the social distance design was successful.

Design

Study 3 used a 2 × 2 between-subjects experimental design featuring the following: crisis type: single-enterprise product-harm crisis vs. group product-harm crisis; and social distance: close vs. far. To enhance external validity, this study utilized actual enterprise cases rather than fictional scenarios. All the experimental materials are provided in Appendix 3.

Procedure

The experimental procedure followed the same rigorous protocol established in Studies 1 and 2, maintaining methodological consistency across all investigations. The participants were randomly assigned to conditions and completed the study under standardized experimental controls.

Measures

The measurement items for all scales (perceived betrayal and blame attribution) remained consistent with those employed in Study 2. For manipulation checks, the participants’ perceptions of crisis type were assessed using a single-item measure adapted from Tu et al. (2013), while social distance was evaluated through a one-item scale derived from Huang et al. (2011). In line with Muhamad et al. (2019), we implemented a newly developed 7-point Likert scale to assess consumer boycott intentions to highlight the essence of boycotts. The measurement used four items, such as “I plan to boycott products of the enterprise” (in the situation of a single-enterprise product-harm crisis) and “I plan to boycott products of the enterprises” (in the situation of a group product-harm crisis).

Participants and sampling

Data were collected through both online and offline survey methods, which constitute established approaches for obtaining representative samples across diverse demographic groups (Peer et al. 2022). An online research platform facilitates broad participant recruitment, whereas offline data collection enables rigorous quality control. Specifically, offline data were collected from a shopping mall located in Wuhan, China, characterized by a high population density, whereas online data were obtained through the Credamo online survey platform (www.credamo.com). To ensure sample randomness, the participant selection method and procedure for offline data collection were consistent with those used in Study 2.

According to G*Power 3.1 software (Faul et al. 2007), this study required a minimum of 210 participants under conditions where a medium effect size = 0.25, α = 0.05, and β = 0.05. The study ultimately obtained 344 valid responses, exceeding this minimum requirement (see Table 2).

Results

Manipulation check

An independent samples t test revealed significant differences in the participants’ perceptions of the number of enterprises involved across crisis conditions (t = −20.357, p < 0.05). The participants in the single-enterprise product-harm crisis condition perceived significantly fewer enterprises involved (M single enterprise = 2.610) than did those in the group product-harm crisis condition (Mgroup = 6.050). These results confirm the effectiveness of our experimental manipulation, demonstrating that the participants clearly distinguished between the two crisis types in terms of the scale of enterprise involvement.

An independent samples t test revealed significant differences in the participants’ perceptions of social distance between the close and far contexts (t = −13.809, p < 0.05), with the participants in the close condition reporting significantly lower scores (Mclose = 2.120) than those in the far condition (Mfar = 4.360). A one-sample t test was used to judge whether the manipulation of social distance met expectations. Specifically, the participants in the distant condition scored significantly above the midpoint of the 7-point scale (t = 9.710, p < 0.05; Mfar = 4.360), demonstrating that the participants in this condition accurately perceived the crisis as being far from them. Conversely, the participants in the close condition scored significantly below the midpoint of the 7-point scale (t = −10.773, p < 0.05; Mclose = 2.120), indicating that the participants in this condition correctly identified the crisis as being close to them. These results provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of our social distance manipulation.

Reliability and validity

To evaluate scale reliability, we calculated Cronbach’s α coefficients for all measurement instruments. All the α values obtained exceeded the widely accepted threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978), demonstrating adequate internal consistency.

The validation analysis incorporated four indicators: item reliability (SMC > 0.50), composite reliability (CR > 0.70), convergent validity (AVE > 0.50), and discriminant validity (the square root of the AVE was larger than the respective correlation with other variables). Data analysis revealed that all scales met these criteria, confirming robust measurement validity.

Hypothesis test

Direct effect

After considering the demographics of the participants as covariates, we conducted a one-way analysis of covariance to examine H1. As predicted, the participants exposed to a group product-harm crisis expressed significantly stronger boycott intentions (Mgroup = 5.914, SD = 0.837) than did those exposed to a single-enterprise crisis (Msingle-enterprsie = 5.191, SD = 1.274) (F(1.344) = 42.396, p < 0.000). These results confirm H1, demonstrating that a group product-harm crisis elicits more pronounced consumer boycott responses.

Mediation effect

To examine the mediating effects of blame attribution and perceived betrayal, we conducted bootstrapping (5000 samples) while controlling for demographic variables. The results indicated that both blame attribution (β = 0.537, SE = 0.072; not including zero at 95% CI: 0.398–0.678) and perceived betrayal (β = 0.400, SE = 0.072; not including zero at 95% CI: 0.259–0.541) acted as mediators in the relationship between the crisis and consumer boycott intentions. These findings provide empirical support for H2 and H3, confirming that product-harm crises affect consumer boycotting through the mediating roles of blame attribution and perceived betrayal.

Moderating effect

A two-way analysis of variance indicated that, after controlling for demographic characteristics, there was a significant interaction effect between product-harm crises and social distance on consumer boycott intentions (F(1344) = 12.039, p = 0.001). Further analysis revealed that in the far social distance condition, the participants exposed to a group product-harm crisis reported significantly greater boycott intentions than did those exposed to the single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Mfar group = 5.821, SD = 0.785 vs. Mfar single enterprise = 4.849, SD = 1.260, F(1187) = 35.199, p < 0.05). Conversely, in the close social distance condition, no significant difference emerged between the group product-harm crisis (Mclose-group = 5.985, SD = 0.872) and the single-enterprise product-harm crisis in terms of consumer boycott intentions (Mclose-single enterprise = 5.852, SD = 1.023) (F(1155) = 0.746, p = 0.389). Hence, H4a is supported.

A significant interaction effect between crises and social distance on perceived betrayal emerged (F(1344) = 8.005, p = 0.005). Simple effects analysis revealed that, in the far social distance condition, the participants in the group product-harm crisis scenario reported significantly greater perceived betrayal (Mfar group = 5.811, SD = 0.597) than did those in the single-enterprise product-harm crisis scenario (Mfar single enterprise = 5.111, SD = 1.045; F(1187) = 27.332, p < 0.05). Conversely, in the close social distance condition, no statistically significant difference in perceived betrayal was observed between the group product-harm crisis (Mclose group = 5.935, SD = 0.707) and the single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Mclose single enterprise = 5.814; SD = 0.774; F(1155) = 1.003, p = 0.318). Therefore, H4b is confirmed.

A significant interaction effect between crises and social distance on blame attribution was observed (F(1344) = 11.979, p = 0.001). Simple effects analysis demonstrated that in the far social distance condition, the participants exposed to the group product-harm crisis exhibited significantly stronger blame attribution to the enterprise (Mfar group = 6.225, SD = 0.524) than did those encountering the single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Mfar single enterprise = 5.374, SD = 1.031; F(1,187) = 43.153, p < 0.05). In contrast, a close social distance eliminated this differential effect. No statistically significant disparity between the group product-harm crisis (Mclose-group = 6.241, SD = 0.612) and the single-enterprise product-harm crisis (Mclose-single enterprise = 6.040, SD = 0.738; F(1155) = 3.381, p = 0.068) emerged. These findings provide empirical support for H4c.

Discussion

Study 3 extended the investigation to real enterprises. The findings demonstrated congruence between the results obtained with real enterprises and those derived from fictional scenarios. Specifically, replicating prior findings, a group product-harm crisis elicited significantly stronger consumer boycott intentions than did a single-enterprise product-harm crisis. Crucially, the differential impact of crisis type on boycott behaviour was mediated by perceived betrayal and blame attribution.

Further analyses confirmed the boundary effect of social distance. Specifically, social distance significantly moderated the effects of product-harm crises on three key outcome variables: perceived betrayal, blame attribution, and consumer boycott intentions. The results demonstrated that in the far social distance conditions, a group product-harm crisis (vs. a single-enterprise product-harm crisis) elicited stronger consumer boycott intentions, higher levels of perceived betrayal, and greater blame attribution. However, these differential effects disappeared in the close social distance conditions, where no significant differences between the group product-harm crisis and the single-enterprise product-harm crisis emerged across all three variables (i.e., consumer boycott intentions, perceived betrayal, and blame attribution). These findings indicate that social distance moderates the direct relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycott intentions and the indirect relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycott intentions through the mediating variables of perceived betrayal and blame attribution. The main reason for these results is that a close social distance improves consumers’ perceived relevance of a crisis and enhances their sensitivity to the crisis, leading to altered information processing models (Wang et al. 2020). Moreover, emotional responses triggered by a close social distance outweigh other cognitive factors in shaping consumer reactions (Huang et al. 2011). Consequently, when the social distance is close, the impact of the number of enterprises involved in a crisis on consumer response is no longer significant.

General discussion

Key findings

With the increasing involvement of enterprises in product-harm crises (Cui and Yu, 2015; Yalin and Min, 2022), scholars have categorized such crises into group product-harm crises and single-enterprise product-harm crises (Cui and Yu, 2015; Li and Zhao, 2024; Wang et al. 2012). However, research has focused predominantly on single-enterprise product-harm crises, leaving group product-harm crises relatively underexplored (Li and Zhao, 2024). Grounded in the AEB model, this study constructed a novel conceptual model to test how different product-harm crises affect consumer boycotting and what moderating effect social distance has. Through three studies, the main findings of this research are as follows.

First, this study revealed that consumer boycott intentions are significantly stronger in group product-harm crises than in single-enterprise product-harm crises, primarily driven by differences in consumers’ perceptions of the egregiousness of different product-harm crises. Compared with a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, a group product-harm crisis has a more severe impact (Cui and Yu, 2015), leading consumers to perceive the egregiousness of enterprise behaviour and thus intensifying their boycott behaviour. According to the AEB framework, the perceived egregiousness of a group product-harm crisis serves as a key driver of stronger consumer boycott intentions. This result is consistent with those of previous studies (e.g., Barakat and Moussa, 2017; Klein et al. 2004; Seyfi et al. 2023; Ulker-Demirel et al. 2021), which established a robust link between perceived egregiousness and consumer boycotts.

Second, this study demonstrated that blame attribution (a cognitive factor) and perceived betrayal (an emotional factor) serve as key mediators in the relationship between product-harm crises and consumer boycotts. Specifically, crises influence consumer boycotts by triggering feelings of betrayal while simultaneously shaping consumers’ attributions of blame. These findings reinforce the dual role of cognitive and affective mechanisms in explaining consumer responses to enterprise crises, which aligns with prior research (e.g., Lim and Shim, 2019; Rasouli et al. 2023; Su et al. 2022; Temessek Behi et al. 2024; Zasuwa, 2024).

Third, the results revealed that, relative to a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, a group product-harm crisis leads to greater blame attribution to enterprises, stronger perceived betrayal, and more intense consumer boycott intentions but only under situations of greater social distance. When social distance is close, the differential impact between group and single-enterprise product-harm crises becomes non-significant. This finding suggests that social distance moderates the intensity of crisis effects on blame attribution, perceived betrayal, and boycott behaviour. One possible explanation is that a closer social distance weakens the influence of primary cognition cues (e.g., the number of enterprises involved in the crisis) while reinforcing the influence of secondary cognition cues (e.g., the degree of impact of the crisis) on behaviour (Lu and Qiu, 2024). This is consistent with the interpretation of consumer behaviour at different distances within the theoretical framework of CLT (e.g., Trope and Liberman, 2010).

Theoretical implications

This study makes significant contributions to the literature from multiple perspectives. First, it contributes to theoretical research on group product-harm crises. While existing research has predominantly examined single-enterprise product-harm crises (Cleeren et al. 2017; Li and Zhao, 2024), the current study addresses the under-researched phenomenon of group product-harm crises. Drawing on the AEB model, we develop a new theoretical framework to systematically analyse how different crises influence consumer boycott behaviour. Our research demonstrates that distinct crises evoke varying cognitive and emotional responses in consumers, leading to differential behavioural outcomes. Specifically, we identify that variations in perceived egregiousness across crisis types generate distinct patterns of cognitive processing (blame attribution) and emotional reactions (perceived betrayal), which in turn shape subsequent consumer behaviours (consumer boycotting) (Aljarah et al. 2022; Lim and Shim, 2019; Barakat and Moussa, 2017; Su et al. 2022). These findings substantially extend the current knowledge of product-harm crises by establishing meaningful distinctions between group product-harm crises and single-enterprise product-harm crises and mapping their differential psychological and behavioural consequences. Furthermore, by employing consumer boycotting as a key outcome variable, this study broadens the scope of product-harm crisis research and enriches our understanding of its multifaceted impacts.

Second, this study makes significant theoretical contributions by explaining the emotional and cognitive dual-process mechanisms underlying crisis responses. Emotions are usually related to subsequent behavioural tendencies (Karl et al. 2021); therefore, many scholars have made efforts to explore and understand emotions during a crisis (Farmaki, 2021; Schoofs and Claeys, 2021). This study chooses perceived betrayal, which better explains consumer emotions, as the mediator variable (Lee and Selart, 2015). Furthermore, by incorporating both cognitive (blame attribution) and affective (perceived betrayal) pathways into the AEB framework, we develop a more comprehensive model of how product-harm crises influence consumer boycotting. The significant mediating effects that we observed demonstrate the empirical validity of this extended AEB model, thus making two key contributions: enriching our understanding of the psychological mechanisms through which product-harm crises operate and theoretically advancing the AEB model by incorporating dual processing pathways.

Third, this study significantly advances our understanding of consumer boycott behaviour by identifying social distance as a critical moderating variable. Our findings establish social distance as a key boundary condition for the effect of product-harm crises on consumers’ subsequent responses. The results provide consistent evidence that consumers’ social distance affects their attitudes and behaviours (Trope and Liberman, 2010). This study explains the boundary conditions from the perspective of information processing patterns and CLT. Specifically, we demonstrate that a closer social distance prompts more systematic information processing (Wang et al. 2020), leading to a deeper comprehension of crisis characteristics. This theoretical integration makes two important contributions: it enriches CLT by applying it to product-harm crisis scenarios, and it provides a strong framework for explaining individual differences in crisis response.

Practical implications

The present study has several practical implications. First, our findings reveal significant variations in consumer emotions, cognitions, and behavioural responses across different product-harm crises. Thus, managers involved in a product-harm crisis should fully consider these differences and develop tailored response strategies on the basis of the crisis typology. The results demonstrate that group product-harm crises generate more severe impacts than do single-enterprise crises. Therefore, group product-harm crises should attract more attention from crisis managers, who should expend more effort to manage such crises.

Second, this study highlights the pivotal role of blame attribution and perceived betrayal in shaping consumer responses to product-harm crises (Aljarah et al. 2022; Fannes and Claeys, 2023; Rasouli et al. 2023; Yalin and Min, 2022). Notably, our findings reveal that, compared with a single-enterprise product-harm crisis, a group product-harm crisis elicits significantly stronger perceived betrayal and greater tendencies to attribute blame to the involved enterprises. These insights underscore the critical need to incorporate both blame attribution and perceived betrayal as key considerations in crisis management strategies. Building on these findings, we propose that effective crisis management should aim to mitigate negative impacts by strategically addressing these psychological mechanisms (i.e., blame attributions and perceived betrayal). Menon et al. (1999) demonstrated significant cross-cultural variations in attribution patterns, with East Asian consumers showing a greater propensity to attribute causality to collectives than North American consumers do. It could be inferred that there are differences in blame attribution for a group product-harm crisis in different cultures. Consequently, targeted crisis management strategies should be designed on the basis of different cultures. In the context of a collectivist culture, macro-level interventions involving industry associations and government entities may prove most effective, whereas in the context of an individualist culture, enterprise-focused response strategies are likely to yield better outcomes.

In addition, this study further identifies perceived betrayal as a critical psychological mechanism influencing post-crisis consumer responses. Our findings suggest that strategically mitigating perceived betrayal could effectively reduce the negative impact of product-harm crises. For example, environmental uncertainty serves as a key antecedent of perceived betrayal (JinSoo et al. 2013). Building on these insights, reducing uncertainty through information disclosure can reduce perceived betrayal and thus decrease the impact of a product-harm crisis.

Third, our findings reveal that the impact of a group product-harm crisis on consumer boycotting, blame attribution, and perceived betrayal is significant only in situations of a far social distance. Consumers tend to evaluate product-harm crises on the basis of their perceived relationship with the crisis. These results have important managerial implications for crisis response. For example, crisis managers should prioritize consumers who perceive a close social distance to the crisis and design targeted strategies around them.

Limitations and future research directions

This research has some limitations that offer directions for future research. First, this study analysed the influence of different crises on blame attribution. Specifically, to what extent do consumers attribute responsibility for different product-harm crises to enterprise(s)? However, owing to the diffusion of responsibility or the punishment effect (Keshmirian et al. 2022), as the number of individuals involved in an event increases, the perceived responsibility assigned to each individual decreases. This research content differs from the themes reflected in diffusion of responsibility theory. In the future, the influence of a group product-harm crisis can be analysed in the context of diffusion of responsibility theory.

Second, this study emphasized the moderating role of social distance. The key distinction between group and single-enterprise product-harm crises lies in the number of enterprises involved. Whether the number of enterprises involved affects consumers’ perceptions of psychological distance needs to be researched further. Additionally, since the level of construal varies depending on the type of crisis (Lee et al. 2021), another interesting area of future research is whether different product-harm crises can trigger different psychological distance perceptions.

Third, consumers exhibit varied responses following a product-harm crisis. This study specifically examined three key reactions: perceived betrayal, blame attribution, and boycott behaviour. However, additional responses—such as panic buying—warrant further investigation in future research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of post-crisis consumer behaviour.

Finally, prior research has demonstrated that consumer‒enterprise relationships significantly influence post-crisis responses (Grégoire and Fisher, 2008; Su et al. 2022; Temessek Behi et al. 2024). While this factor was intentionally controlled for in Studies 1 and 2 through the use of fictional enterprises, Study 3 incorporated real enterprises in the scenario design, and the relational factors may have affected the conclusions of this study. Future research should explicitly account for these relational factors to strengthen the findings of this study.

Conclusion

Through three experimental studies, this research systematically examined how different product-harm crises (single-enterprise product-harm crises vs. group product-harm crises) influence consumer boycotting through the mediating mechanisms of blame attribution and perceived betrayal. This study further revealed the moderating role of social distance in this process. These findings extend the application of the AEB framework to product-harm crisis contexts, offering both theoretical contributions and practical insights for crisis management and mitigation strategies.

Data availability

We have uploaded the data of our study to the submission system. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the website required by the journal.

References

Aljarah A, Dalal B, Ibrahim B, Lahuerta-Otero E (2022) The attribution effects of CSR motivations on brand advocacy: psychological distance matters! Serv Ind J 42(No.7):583–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2041603

Antonetti P, Maklan S (2016) An extended model of moral outrage at corporate social irresponsibility. J Bus Ethics 135:429–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2487-y

Baghi I, Gabrielli V (2021) The role of betrayal in the response to value and performance brand crisis. Mark Lett 32(No.2):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-021-09559-7

Barakat A, Moussa F (2017) Using the expectancy theory framework to explain the motivation to participate in a consumer boycott. J Mark Dev Compet 11(No.3):32–46

Bower GH (1981) Mood and memory. Am Psychol 36(No.2):129–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129

Calder BJ, Tybout AM (1999) A vision of theory, research, and the future of business schools. J Acad Mark Sci 27(No.3):359–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399273006

Carvalho SW, Muralidharan E, Bapuji H (2015) Corporate social ‘irresponsibility’: Are consumers’ biases in attribution of blame helping companies in product–harm crises involving hybrid products? J Bus Ethics 130(No.3):651–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2258-9

Chen T, Tang Y, Qing P (2020) When brand scandal spills over brands from the same region of origin: moderating role of psychic distance. Eur J Int Manag 14(No.3):461–475. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2020.107040

Cheng P, Wei J, Ge Y (2017) Who should be blamed? The attribution of responsibility for a city smog event in China. Nat Hazards 85(No.2):669–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2597-1

Chung S, Lee S (2021) Crisis management and corporate apology: the effects of causal attribution and apology type on publics’ cognitive and affective responses. Int J Bus Commun 58(No.1):125–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417735646

Cleeren K, Dekimpe MG, Van Heerde HJ (2017) Marketing research on product-harm crises: a review, managerial implications, and an agenda for future research. J Acad Mark Sci 45(No.5):593–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0558-1

Cleeren K, van Heerde HJ, Dekimpe M (2013) Rising from the ashes: How brands and categories can overcome product-harm crises. J Mark 77:58–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/23487413

Coombs WT (2006) The protective powers of crisis response strategies: managing reputational assets during a crisis. J Promot Manag 12(No.3-4):241–260. https://doi.org/10.1300/J057v12n03_13

Coombs WT, Schmidt L (2000) An empirical analysis of image restoration: Texaco’s racism crisis. J Public Relat Res 12(No.2):163–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1202_2

Cossío-Silva FJ, Revilla-Camacho MA, Palacios-Florencio B, Garzón-Benítez D (2019) How to face a political boycott: The relevance of entrepreneurs’ awareness. Int Entrep Manag J 15(No.2):321–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00579-4

Crouch RC, Lu VN, Pourazad N, Ke C (2021) Investigating country image influences after a product-harm crisis. Eur J Mark 55(No.3):894–924. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0689

Cui BJ, Yu WP (2015) Characteristics, causes and governance of hidden rules type product harm crisis. Soc Sci Front No.8, 44-53

Cui BJ, Yu WP, Wu B (2019) The influence of cluster product-harm crisis on category resistance. J Dalian Univ Technol 40(No.6):48–56. https://doi.org/10.19525/j.issn1008-407x.2019.06.006

Delistavrou A, Tilikidou I, Krystallis A (2020) Consumers’ decision to boycott “unethical” products: the role of materialism/post materialism. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 48(No.10):1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-04-2019-0126

Duman S, Özgen Ö (2018) Willingness to punish and reward brands associated to a political ideology (BAPI). J Bus Res 86(No.2):468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.026

Fannes G, Claeys AS (2023) Shaping attributions of crisis responsibility in the case of an accusation: The role of active and passive voice in crisis response strategies. J Lang Soc Psychol 42(No.1):3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X221108120

Farmaki A (2021) Memory and forgetfulness in tourism crisis research. Tour Manag 83:104210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104210

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(No.2):175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fediuk TA, Coombs WT, Botero IC (2010) Exploring crisis from a receiver perspective: Understanding stakeholder reactions during crisis events, In: Schwarz, A, Seeger, MW & Auer, C (eds). The handbook of crisis communication. London: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444314885.ch31

Fuchs G, Efrat-Treister D, Westphal M (2024) When, where, and with whom during crisis: the effect of risk perceptions and psychological distance on travel intentions. Tour Manag 100:104809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104809

Gerrath MH, Brakus JJ, Siamagka NT, Christodoulides G (2023) Avoiding the brand for me, us, or them? Consumer reactions to negative brand events. J Bus Res 156:113533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113533

Gilbert C (2022) To blame is human: a quantitative systematic review of the relationship between outcome severity of large-scale crises and attributions of blame. Risk Anal 42(No.9,):1980–1998. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13847

Grégoire Y, Fisher RJ (2008) Customer betrayal and retaliation: when your best customers become your worst enemies. J Acad Mark Sci 36(No.2):247–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0054-0

Hansen T (2012) The moderating influence of broad-scope trust on customer-seller relationships. Psychol Mark 29(No.5):350–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20526

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19:139–151. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

He H, Kim S, Gustafsson A (2021) What can we learn from# StopHateForProfit boycott regarding corporate social irresponsibility and corporate social responsibility? J Bus Res 131(No.3):217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.058

Hegner SM, Beldad AD, Hulzink R (2018) An experimental study into the effects of selfdisclosure and crisis type on brand evaluations-the mediating effect of blame attributions. J Prod Brand Manag 27(No.5):534–544. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-05-2017-1478

Heijnen P, van der Made A (2012) A signalling theory of consumer boycotts. J Environ Econ Manag 63(No.3):404–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2012.01.004

Hong S, Shim E (2023) Ethical public typology: How does moral foundation theory and anticorporatism predict changes in public perceptions during a crisis? J Contingencies Crisis Manag 31:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/jccm.12403

Hsu MYT, Cheng JMS (2018) fMRI neuromarketing and consumer learning theory: word-of-mouth effectiveness after product harm crisis. Eur J Mark 52(No.1/2):199–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0866

Hua LL, Prentice C, Han X (2021) A netnographical approach to typologizing customer engagement and corporate misconduct. J Retail Consum Serv 59:102366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102366

Huang M, Ki EJ (2023) Protecting organizational reputation during a para-crisis: the effectiveness of conversational human voice on social media and the roles of construal level, social presence, and organizational listening. Public Relat Rev 49(No.5):102389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2023.102389

Huang J, Wang XG, Tong ZL (2011) Effects of spatial and social distance on the evaluation for brand’s failure,. China Soft Sci 7:123–131

Hutzinger C, Weitzl WJ (2023) Double jeopardy: effects of inter-failures and webcare on (un-) committed online complainants’ revenge. Internet Res 33(No.7):19–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-02-2022-0115

Isiksal DG, Karaosmanoglu E (2020) Can self-referencing exacerbate punishing behavior toward corporate brand transgressors? J Brand Manag 27(No. 6):629–644. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00204-8

JinSoo L, Pan S, Tsai H (2013) Examining perceived betrayal, desire for revenge and avoidance, and the moderating effect of relational benefits. Int J Hosp Manag 32(No.March):80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.04.006

Kang J, Faria AA, Lee J, Choi WJ (2023) Will consumers give us another chance to bounce back? Effects of precrisis commitments to social and product responsibility on brand resilience. J Prod Brand Manag 32(No.6):927–941. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-03-2022-3899

Karl M, Kock F, Ritchie BW, Gauss J (2021) Affective forecasting and travel decision-making: an investigation in times of a pandemic. Ann Tour Res 87:103139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103139

Kelley H, Michela JL (1980) Attribution theory and research. Annu Rev Psychol 31(No.1):457–501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325

Keshmirian A, Hemmatian B, Bahrami B, Deroy O, Cushman F (2022) Diffusion of punishment in collective norm violations. Sci Rep. 12(No.1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19156-x

Klein J, Dawar N (2004) Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. Int J Res Mark 21(No.3):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.003

Klein J, Smith NC, John A (2004) Why we boycott: consumer motivations for boycott participation. J Mark 68(No.3):92–109. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.3.92.3

Kim C, Kim W, Nakami S (2022) Do online sales channels save brands of global companies from consumer boycotts? A geographical analysis. J Retail Consum Serv 68:103069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103069

Kim S, Jin Y, Reber BH (2020) Assessing an organizational crisis at the construal level: How psychological distance impacts publics’ crisis responses. J Commun Manag 24(No.4):319–337. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-11-2019-0148

Kim Y, Woo CW (2019) The buffering effects of CSR reputation in times of product-harm crisis. Corp Commun: Int J 24(No.1):21–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-02-2018-0024

Koehler JJ, Gershoff AD (2003) Betrayal aversion: When agents of protection become agents of harm. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 90(No.2):244–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00518-6

Kozinets RV, Handelman JM (2004) Adversaries of consumption: consumer movements, activism, and ideology. J Consum Res 31(No.3):691–704. https://doi.org/10.1086/425104

Lasarov W, Hoffmann S, Orth U (2023) Vanishing boycott impetus: Why and how consumer participation in a boycott decreases over time. J Bus Ethics 182(No.4):1129–1154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04997-9

Laufer D, Gillespie K, McBride B, Gonzalez S (2005) The role of severity in consumer attributions of blame: defensive attributions in product-harm crises in Mexico. J Int Consum Mark 17(No.2-3):33–50. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v17n02_03

Lee HM, Chen T, Chen YS, Lo WY, Hsu YH (2020) The effects of consumer ethnocentrism and consumer animosity on perceived betrayal and negative word-of-mouth. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 33(No.3):712–730. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2019-0518

Lee SY, Sung YH, Choi D, Kim DH (2021) Surviving a Crisis: How crisis type and psychological distance can inform corporate crisis responses. J Bus Ethics 168:795–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04233-5

Lee WS, Selart M (2015) How betrayal affects emotions and subsequent trust. Open Psychol J 8(No.1):153–159. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101508010153

Leonidou LC, Aykol B, Hadjimarcou J, Palihawadana D (2018) Betrayal in buyer-seller relationships: exploring its causes, symptoms, forms, effects, and therapies. Psychol Mark 35(No.5):341–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21090

Lewis JD, Weigert A (1985) Trust as a social reality. Soc Forces 63(No.6):967–985. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578601

Li Q, Wei HY, Laufer D (2019) How to make an industry sustainable during an industry product harm crisis: the role of a consumer’s sense of control. Sustainability 11(No.1):3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113016

Li Y, Zhao M (2024) The research on the impact of industry governance on trust after group product-harm crisis. Heliyon 10(No.15):e35229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35229

Liberman N, Trope Y (2014) Traversing psychological distance. Trends Cogn Sci 18(No.7):364–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.001

Liberman N, Trope Y, McCrea SM, Sherman SJ (2007) The effect of level of construal on the temporal distance of activity enactment. J Exp Soc Psychol 43(No.1):143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.009

Lim JS, Shim K (2019) Corporate social responsibility beyond borders: U.S. consumer boycotts of a global company over sweatshop issues in supplier factories overseas. Am Behav Sci 63(No. 12):1643–1664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219835241

Lu Y, Qiu J (2024) Influence of cognitive and emotional frames on Weibo users’ information dissemination behavior in natural disaster emergencies: The moderating effect of psychological distance. Libr Inf Sci Res 46(2):101298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2024.101298

Ma L (2018) How to turn your friends into enemies: causes and outcomes of customers’ sense of betrayal in crisis communication. Public Relat Rev 44(No.3):374–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.04.009

Malhotra N, Kuo AG (2009) Emotions as moderators of information cue use: citizen attitudes toward Hurricane Katrina. Am Politics Res 37(No.2):301–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X08328002