Abstract

A catastrophic flood is a notorious phenomenon with severe consequences for individuals and governments. Purchasing flood insurance can be a viable solution to mitigate the effects of such disasters. This study examines the factors that influence the purchase intention and behavior of flood insurance among people living in flash flood-prone areas. By integrating the protection motivation theory, a comprehensive model is proposed. Based on convenience sampling, data were collected from 331 Malaysians living in flash flood-prone areas in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Partial least squares—structural equation modeling was employed to analyze the data. This study reveals that flood awareness has a positive impact on perceived severity (β = 0.137, f2 = 0.019) and vulnerability (β = 0.354, f2 = 0.143). However, past flood experience does not have a significant effect on response efficacy and cost. Additionally, flood insurance purchase intention is influenced by perceived severity (β = 0.121, f2 = 0.026), response efficacy (β = 0.487, f2 = 0.391), response cost (β = −0.153, f2 = 0.041), and functional value (β = 0.241, f2 = 0.094) but not by perceived vulnerability. Moreover, functional value (β = 0.149, f2 = 0.020) and purchase intention (β = 0.211, f2 = 0.040) significantly influence purchase behavior. This study provides a unique perspective on decision-making dynamics in a flood-prone region and offers valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers to enhance the insurance industry by integrating the factors of flood awareness, past experience, and functional value with protection motivation theory. This study suggests that flood insurance company managers adjust their policy guidelines to better serve their stakeholders in similar contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, floods are prevalent natural disasters including monsoons and flash floods, which pose a significant threat to homes, vehicles, livelihoods, and lives. Consequently, adapting to natural disasters, particularly floods, is a crucial challenge for people in building and maintaining sustainable societies (Richerta et al. 2016). Therefore, the important question arises: What compels citizens and businesses in emerging economies to battle with the invincible force of nature, particularly flood catastrophes? The answer lies in the fact that insurance can provide a sense of security during and after a disaster, serving as the backbone for people to safeguard their futures (Raza et al. 2020). According to Alam et al. (2020), insurance is crucial in managing risk at every level, aiding moderate-income individuals in coping with the financial consequences of climate-related perils, supporting adaptation actions, stabilizing regional revenues, and minimizing reliance on public resources for disaster recovery. Moreover, insurance facilitates private-public partnerships and helps individuals and communities recover from disasters swiftly, addressing a wide range of risks through specialized insurance products. In particular, flood insurance provides financial assistance to repair or replace damaged property, offers peace of mind, aids in the recovery and rebuilding processes, and contributes to community resilience. Studies have shown that those with insurance recover faster than those without insurance (Bradt et al. 2021). Insurance is the most effective way to address these obstacles (Tesselaar et al. 2022). Therefore, it is crucial for residents of flood-prone areas to understand the value of flood insurance and consider acquiring it to protect their homes and other valuables. Procuring an insurance policy can reduce the risk individuals face amidst unexpected costs, shielding them from the negative effects of financial burdens (Mamun et al. 2021).

Peninsular Malaysia has faced the devastating consequences of major floods since 1886, constituting a recurrent disaster that has resulted in significant socio-economic and humanitarian issues in the area, as reported by Lim et al. (2019). The impact of floods can be divided into two categories: short- and long-term. The short-term consequences of floods include loss of life, injury, destruction of infrastructure, and damage to businesses, crops, fisheries, animals, property, and infections. Conversely, the long-term consequences involve rebuilding homes, infrastructure, and roads, loss of commerce and industry, and of the financial burdens associated with insurance and other properties (Chan, 2015). Therefore, flood insurance is a useful tool for managing and recovering from disasters.

Previous research has examined insurance purchase intention and behavior by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) across various insurance types, such as Islamic insurance (Takaful) (Maduku and Mbeya, 2023; Rifas et al. 2023), health insurance (Mamun et al. 2021), and life insurance (Masud et al. 2021). However, fewer studies have examined individuals’ pro-environmental behavior toward flood insurance by applying Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). Nevertheless, by integrating PMT, Shafiei and Maleksaeidi (2020) explored the factors that motivate university students’ pro-environmental behavior. Veeravalli et al. (2022) identified factors influencing flood damage mitigation behavior among business owners, providing valuable insights into enhancing such behavior and mitigating flood damage in the future. However, their findings were limited to the context of Kampala, where frequent but not severly damaging flooding occurs. Moreover, their study revealed a counterintuitive result: a negative relationship between flood experience and mitigation efforts. Heidenreich et al. (2020) examined the effectiveness of flood protection workshops for individual households in flood-prone locations in Germany. However, the absence of a control group compromised their study’s validity, and a causal association between the constructs was not established. Ndifon et al. (2020) studied the factors that influence the adoption of mobile-supported health insurance services (MHIS) and participation in health insurance schemes in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). However, their proposed model only accounts for 58% of the variance in MHIS adoption in LMIC, indicating that other behavioral factors may also play a role in this phenomenon.

The theoretical implications of PMT are extensive, yet there exists a gap in the literature regarding the relationship between PMT and pro-environmental behavior in the context of insurance purchases. This theory, initially created by Rogers (1975) in the field of health psychology, PMT clarifies how people react to threats via threat appraisal and coping appraisal. As the acquisition of flood insurance serves as a protective measure against flood risk, PMT offers a solid basis for comprehending the motivations behind individuals’ decision to engage in this behavior. Although PMT has been extensively utilized in health (Wang et al. 2019; Ndifon et al. 2020) and disaster preparedness (Heidenreich et al. 2020; Hudson et al. 2020; Veeravalli et al. 2022), its significance in pro-environmental behavior concerning insurance uptake has yet to be fully examined. Existing research has limited focus on the psychological and motivational factors that influence insurance purchases. This study addresses that gap by employing PMT to evaluate flood insurance purchasing behavior among people affected by flooding. This research provides an enhanced comprehension of the cognitive mechanisms that promote insurance purchase by integrating the essential elements of PMT, threat appraisal (perceived vulnerability and severity), and coping appraisal (response efficacy and cost). Threat appraisal entails evaluating the level of risk, while coping appraisal indicates a person’s perceived capability to undertake protective measures (Ndifon et al. 2020; Savari et al. 2022). Moreover, this research includes flood awareness, previous flood experiences, and functional value as key components in the framework. The study advances theory and practice through the application of PMT to guide policies that encourage flood insurance purchase, strengthen disaster resilience, and improve the sustainability of the environment in Malaysia, especially as a growing economy. This study aims to address the following research objectives:

-

To examine the effects of individuals’ flood awareness on threat appraisal.

-

To examine the effects of past flood experiences on coping appraisal.

-

To examine the effects of threat and coping appraisal on the intention to purchase flood insurance.

-

To examine the effect of functional value on individuals’ flood insurance purchase intention and behavior.

-

To examine the effect of flood insurance purchase intention on purchase behavior.

Both theoretical and practical aspects drove the prioritization of the research objectives. PMT guided the selection, emphasizing essential constructs like threat appraisal, coping appraisal, and behavioral intention as primary criteria. Furthermore, the objectives were put together in a coherent order, commencing with awareness, experience, and functional value before advancing to motivational effects and purchasing behaviors. To put these objectives into action, survey questions were created that directly corresponded to each one. Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized as a statistical technique to examine the relationships between these constructs, confirming the empirical validity of the proposed framework. This strategy permitted a systematic analysis of flood victims’ decision-making processes, providing insights into their insurance-purchasing behaviors. To accomplish these objectives, this study, conducted in Klang Valley, Malaysia, explores the factors influencing the intention and behavior of purchasing flood insurance.Moreover, the three additional constructs integrated with PMT–flood awareness, past flood experiences, and functional value–offers valuable insights into how individuals respond to flood-related threats and develop protective behaviors. Consequently, policymakers, insurance agencies, and flood and disaster management organizations can develop specific strategies to enhance the financial protection of communities in flood-prone areas. This will enable government agencies to reduce the financial burden of floods, resulting in more effective disaster management.

The remaining sections of this paper are structured as follows. Section 'Literature review' describes a literature review, including key terms and concepts, theoretical foundations, and hypothesis development. Section 'Methodology' outlines the research methodology. Section 'Findings' describes the data analysis and results. Section 'Discussion' outlines the findings, implications, limitations, and recommendations for further research. Finally, Section 'Conclusion' concludes the study.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation

The PMT, originated by Rogers (1975), outlines how people evaluate threats and choose to engage in protective actions, like grabbing flood insurance, through analyzing their coping techniques when faced with anxiety-provoking occurrences. This theory posits that people protect themselves through threat and coping appraisals. Threat appraisal is a cognitive process in which individuals assess the severity and vulnerability of perceived threats (Bijani et al. 2022). In this research, it is indicated by perceived severity (the potential harm from floods) and perceived vulnerability (the likelihood of experiencing floods). In between, coping appraisal involves evaluating an individual’s ability to perform risk-preventive behaviors (Ndifon et al. 2020). In this research, it is indicated through response efficacy (the belief that flood insurance is an effective safeguard) and response cost (the perceived financial strain that may discourage purchase). Neisi et al. (2020) contended that PMT is a theoretical framework that can accurately predict real-world behaviors by identifying psychological mechanisms and understanding the reasons for protective choices.

This study enriches the model by adding flood awareness, past flood experience, and functional value to bridge the gaps in current studies and elevate PMT’s capability to forecast flood insurance purchases. Increased flood awareness raises flood risk recognition, resulting in a greater threat assessment, which leads people to view floods as an imminent danger. Additionally, Bekkers et al. (2023) identified a correlation between awareness of ransomware threats and responsiveness. Previous encounters with flooding, as individuals who have directly experienced flooding tend to recognize the seriousness of the disaster, impact their coping appraisal by shaping their views on the efficacy and cost of flood insurance as a safeguard (Yan and Tao, 2021). This enhancement fortifies PMT by integrating direct experience as a factor in risk perception and coping strategies. Functional value evaluates if people see flood insurance as advantageous in ways apart from merely reducing risk (Dangelico et al. 2021). This research enhances the comprehension of the psychological and practical factors affecting flood insurance uptake, rendering PMT more pertinent to actual decision-making in flood-prone areas through the integration of these additional constructs.

PMT has been extensively utilized to investigate behaviors in the context of risk management (Marikyan et al. 2022), environmental (Shafiei and Maleksaeidi, 2020; Bijani et al. 2022; Savari et al. 2022), and health-related (Ndifon et al. 2020) contexts. Additionally, researchers have integrated PMT into studies on flood-related behaviors. For example, Ghaniana et al. (2020) evaluated the psychosocial aspects influencing farmers’ adaptation intentions in Iran. Similarly, researchers have also investigated the interaction between risk perception and self-efficacy in flood risk adaptation (Hudson et al. 2020). Veeravalli et al. (2022) further explored key components such as flood experience, risk attitudes, business characteristics, and risk communication in regulating behavior to mitigate flood damage among SMEs. However, their study was limited to Uganda. Additionally, Banerski and Abramczuk (2023) examined motivational factors for undertaking measures to mitigate flood risk, incorporating fear and self-protective knowledge as additional constructs in their research model. Nonetheless, although PMT has been utilized for flood mitigation behaviors, limited studies have examined its influence on intention and behavior related to purchasing flood insurance. This research fills these gaps by utilizing PMT to explore how threat and coping assessments, alongside flood awareness, previous flood experiences, and functional value, affect people’s choices about flood insurance. This research enhances theory by broadening PMT’s relevance to risk management concerning natural disasters and offers practical guidance by offering concrete ideas for insurance companies and policymakers to create more impactful flood insurance awareness initiatives and policies that resonate with vulnerable communities.

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to address the findings of existing literature, concentrating on the flood insurance perspective. A summary of the literature review is presented in Table 1, revealing a dearth of studies on flood insurance in Malaysia and highlighting the need for additional research in this area. Therefore, it is essential to conduct comprehensive studies that explore the factors influencing purchase intention and flood insurance behavior in Malaysia to increase awareness of the subject. Furthermore, the majority of the reviewed studies used a quantitative approach but lacked theoretical integration. Consequently, further research is required to examine the factors influencing victims’ intentions to purchase flood insurance by integrating theoretical concepts. While PMT has been extensively utilized in decision-making related to risks, the majority of earlier studies have mainly concentrated on disaster preparedness (Heidenreich et al. 2020; Hudson et al. 2020; Veeravalli et al. 2022) or health-related behaviors (Ndifon et al. 2020), instead of flood insurance purchasing behavior. To address these gaps, this study extends PMT by incorporating flood awareness, past experience, and functional value—factors that are not typically integrated into the PMT framework in the flood insurance context. The research specifically investigates the intention to purchase flood insurance by focusing on PMT’s essential constructs like perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, response efficacy, and response cost, while also incorporating additional elements (flood awareness, past flood experience, and functional value) to provide more profound insight into purchasing behavior.

Hypothesis development

Flood awareness on perceived severity and vulnerability

Flood awareness refers to an individual’s ability to perceive, experience, or be aware of events in their immediate environment (Kazaure, 2019). Masud et al. (2021) defined flood awareness as information sharing, opinion sharing, and exposure through observations to enhance awareness. The concern here is whether individuals are familiar with flood awareness, such as the causes of floods, flood zones, and the time taken to recover from disasters. Individuals with higher awareness levels are likely to have a better understanding of the seriousness of potential harm they may face. A previous study found that desktop security awareness positively affects perceived threat severity (Hanus and Wu, 2016). In addition, information security awareness was found to have a significant and beneficial effect on employees’ perceived severity (Bauer and Bernroider, 2015). People who are more aware of flooding are more likely to perceive its severity and are more likely to recognize the actual risks. This can lead to a greater perception of vulnerability, particularly when people understand that they live in areas where floods may occur at any time, causing property damage, loss of life, and disruption to daily routines. Flood awareness can help people perceive their vulnerability. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1-2. Flood awareness is positively associated with perceived severity and perceived vulnerability.

Past (flood) experiences on response efficacy and cost

Past experiences are defined as an individual’s most recent and frequent encounters with casualties and damage (Lindell and Hwang, 2008). Those with significant experience tend to exhibit high response efficacy. For example, individuals who have previously experienced flood disasters can effectively improve their future responses as a precautionary measure. Li et al. (2019) discovered that past experiences with information security practices influence response efficacy. Furthermore, researchers discovered that farming experience had a favorable effect on response efficacy while adversely affecting response costs. This is due to the fact that farming experience strengthens farmers’ literacy on the risk in agriculture and risk-management measures, thereby improving their assessments while lowering their perception of costs (Yan and Tao, 2021). Additionally, people who have previously experienced flooding may have a better understanding of the challenges and costs associated with responding to such events. Consequently, they may have more realistic expectations regarding response costs. Moreover, they may recognize that preparing for floods can be time-consuming, requires financial investment, and involves inconveniences. Those with prior experience with flooding are likely to be more aware of these obstacles. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3-4. Past (flood) experiences are positively associated with response efficacy and response cost.

Perceived severity and purchase intention

Perceived severity refers to the extent to which individuals perceive possible harm (Marikyan et al. 2022; Ndifon et al. 2020). Previous studies have examined the perceived severity of a specific situation to understand how individuals’ anxiety influences their behavior. Individuals often feel or believe that they are highly susceptible to the negative consequences of an event because of the severity of potential harm. Consequently, they are more inclined to take proactive steps to reduce these risks (Delfiyan et al. 2020). According to Rainear and Christensen (2017), perceived severity positively influences pro-environmental behavioral intention. Furthermore, it was discovered that perceived severity has a significant and favorable impact on rural women’s forest conservation actions (Savari et al. 2022). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5. Perceived severity is positively associated with flood insurance purchase intention.

Perceived vulnerability and purchase intention

Perceived vulnerability refers to individuals’ perceptions of their susceptibility to harm (Janmaimool, 2017; Ndifon et al. 2020). Rainear and Christensen (2017) defined perceived vulnerability as the degree to which people believe they are at risk of experiencing the negative effects of climate change. According to Pakmehr et al. (2020), individuals exhibit protective motivation if they seriously consider threats. Thus, people living in flood-prone areas who perceive themselves as vulnerable to flood-related harm are more likely to have flood insurance to protect themselves. Researchers have demonstrated that perceived vulnerability positively affects forest protection behavior by modeling environmentally responsible behavior (Savari et al. 2022) and decision-making for blockchain adaptation (Marikyan et al. 2022). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6. Perceived vulnerability is positively associated with flood insurance purchase intention.

Response efficacy and purchase intention

Response efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in the effectiveness of protective resources to mitigate potential risks (Janmaimool, 2017; Marikyan et al. 2022). According to Ndifon et al. (2020), response efficacy relates to the perceived capacity to prevent threats associated with the inability to afford proper protective measures. Individuals are more inclined to consider obtaining flood insurance as a viable solution if they believe that it is an effective means to protect their homes and belongings from flood-related damage. Thus, belief in response efficacy can increase willingness to obtain flood insurance. Furthermore, past research has shown that response efficacy has a favorable influence on behavioral intentions from various perspectives (Marikyan et al. 2022; Savari et al. 2022). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7. Response efficacy is positively associated with flood insurance purchase intention.

Response cost and purchase intention

Response cost refers to any perceived cost of protective measures or actions, encompassing both monetary and non-monetary factors such as effort, time, and discomfort (Bockarjova and Steg, 2014). It reflects an individual’s perception of the costs involved in pursuing a behavioral intention (Ndifon et al. 2020). Undoubtedly, acquiring flood insurance entails financial investment in the form of premiums. The need for such coverage, the process of making informed decisions, and the potential for discomfort stem from a lack of familiarity with the fundamental principles of insurance. Individuals facing high response costs are more inclined to reconsider purchasing flood insurance. Savari et al. (2022) investigated pro-environmental behavior and emphasized the negative effects of response costs on forest conservation behavior. Shafiei and Maleksaeidi (2020) confirmed that response cost directly influences pro-environmental behavior, exerting a significantly negative effect. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8. Response cost is negatively associated with flood insurance purchase intention.

Functional value on purchase intention and behavior

The functional value determines the perception of an individual on a product or service by considering price, quality, durability, and dependability. This can be described as the value obtained from utilitarian, functional, or performance aspects (Dangelico et al. 2021; Khan and Mohsin, 2017). Similarly, if individuals perceive high functional value in flood insurance, it is more likely to positively influence their intentions to purchase it. For example, if a person believes that flood insurance policies provide good value for money and are of high quality, their intention to purchase increases. Han et al. (2017) demonstrated that monetary and performance values, except for convenience value, play a vital role in influencing the intention to purchase electric vehicles. Khan and Mohsin (2017) revealed that functional value (price) has a significant relationship, whereas functional value (quality) has an insignificant relationship with consumer behavior regarding green product choice. Additionally, before purchasing flood insurance, individuals compare the price and quality of insurance policies, viewing insurance as a safeguard. Research on green purchasing behavior indicates that functional value enhances the frequency of green product purchases (Dangelico et al. 2021). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H9-10. Functional value is positively associated with the intention and behavior toward flood insurance purchases.

Flood insurance purchase intention

Purchase intention is defined as an individual’s willingness to exert effort to carry out a behavior (Aziz et al. 2019). In other words, it represents the likelihood that a person will engage in certain behaviors. If individuals have a strong intention to obtain flood insurance, it can be inferred that they recognize the significance of securing insurance coverage. Consequently, their intentions are likely to be manifested in the form of a purchase. Mamun et al. (2021) explored the relationship between intention and health insurance purchasing behavior using the TPB and found a positive effect on purchasing behavior. Similarly, Masud et al. (2021) and Wu et al. (2023) confirmed a substantial relationship between intention and purchase behavior. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H11. Flood insurance purchase intention is positively associated with flood insurance purchase behavior.

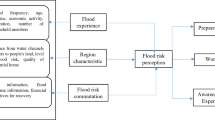

Based on the foundation of PMT and a review of the existing literature, Fig. 1 illustrates the proposed hypotheses, forming associations between exogenous and endogenous variables.

Methodology

This study employed a quantitative approach to investigate the relationships among the integrated variables in the framework. We used PLS-SEM, specifically the Smart-PLS software, to analyze the measurement and structural models. PLS-SEM is extensively used as a non-parametric and multivariate technique for estimating path associations with latent variables (Hair et al. 2019). PLS-SEM has been used for exploratory research when the framework is complex and incorporates various dimensions or factors (Hair et al. 2019).

Population and sample

This surveyed Malaysians living in the flood-prone areas of Klang Valley. As all survey questions related to individuals, they served as the “unit of analysis” in this study. According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (2023), the population of the Klang Valley is approximately 7 million. This study used G-Power software to determine the sample size, with input parameters including an effect size (f2) of 0.15 and the power 1-β err Prob was 0.8. This study required 109 sample size to validate the research model with eight variables, according to G-Power. Consequently, more than 109 responses were considered statistically appropriate. Due to the large population size and to avoid constraints that come with a small sample size, data were collected from 331 respondents aged over 18 years. According to Mamun et al. (2021), this age group is known as adults who can financially support their families, friends, or others. Convenience sampling was used to collect data using personally distributed (face-to-face) questionnaires. The survey was conducted from the beginning of the 4th of September to 27th of October, 2023, among residents of flood-prone areas in Klang Valley. Mamun et al. (2021) deemed this technique appropriate because of the specific attributes of the sample, which included working people and an insurable age group. Before distributing the questionnaire, it was validated by academics, managers, and residents of flood-prone areas. The questionnaire outlined the study’s purpose and reporting protocol, and all respondents provided informed consent before participation. A total of 331 valid responses were obtained.

Instruments

Data were collected via self-administered questionnaires. A 5-point Likert scale was applied, from a range of strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The measurement instrument was adopted from previous studies. The researchers carried out a pilot study by gathering 40 samples, and the outcomes were favorable, permitting us to move forward with the final data collection. Table 2 presents the survey instruments and measurement items used in this study.

Common method bias (CMB)

Common Method Bias (CMB) is a critical issue that affects the reliability of research results. CMB arises when data are gathered from a single source (Spector, 2006). In this study, Harman’s single-factor analysis was used to address issues related to CMB (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). This study conducted seven-factor analyses and found an overall variance of 19.417%, indicating that CMB was not an issue. Additionally, CMB was examined by assessing the full collinearity of each construct, as suggested by Kock (2015). Hair et al. (2019) recommended that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values be below 3. The results presented in Table 3 show that all values were below 3, indicating the absence of CMB.

Multivariate normality

The online resource, Web Power (https://webpower.psychstat.org/models/kurtosis/), was employed to examine the normality of multivariate. Upon conducting the multivariate skewness and kurtosis analyses as per Mardia’s techniques, it was revealed that the p-values of both skewness and kurtosis were below the accepted level of 0.05, confirming the non-normality of the data.

Findings

Demographic details

Demographic information (included in Supplementary Material 1, Table S1) shows that out of the 331 respondents, more male respondents (50.8%) participated compared to female respondents (49.2%). The majority of respondents were married (52.6%), followed by single (31.1%), divorced (11.2%), and widowed (5.1%). Most respondents (31.1%) were 36–45 years old, followed by 26–35 years old (26.9%), 46–55 years old (20.2%), 18–25 years old (12.4%), 56–65 years old (7.9%), and over 65 years old (1.5%). Approximately 47.4% of respondents earned between RM2001 and RM4000 per month, while 25.4% earned between RM4001 and RM6000 per month, and 13% earned between RM6001 and RM8000 per month. Most respondents (67.7%) were full-time employees. Most respondents held a bachelor’s or equivalent degree (35.3%), followed a diploma or equivalent (29.6%), and a secondary school certificate (20.5%). Regarding location, 24.2% were residents of Klang, followed by Hulu Langat (23.9%), Kuala Lumpur and Petaling (19.9%), and Gombak (12.1%). Most respondents (68%) were aware that they lived in flood hotspot locations. Regarding the frequency of flooding issues on their property in five years, 68.3% experienced flooding one to two times, 19.9% experienced flooding three to four times, and only 10.6% reported never experiencing flooding. The majority (78.5%) suffered losses due to floods, with 57.1% experiencing damage to furniture, 47.1% to vehicles, 45% to household appliances, and the remaining 18.4% to building structures. Approximately 42.3% of respondents believed that they knew what to do if a flood occurred tomorrow. Finally, 64.7% of respondents approached relevant agencies to learn more about flood risk, safety, and insurance.

Assessment of measurement model

The measurement model was evaluated by assessing the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs incorporated in the research model.

Reliability and validity

We examined the reliability of the constructs by evaluating Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (CR). According to Hair et al. (2019), Cronbach’s Alpha and CR values should be higher than 0.70. The results presented in Table 4 show that all values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating the constructs’ adequate reliability. The convergent validity of the constructs was assessed by checking the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with a recommended value exceeding 0.50 (Hair et al. 2019). Table 4 shows that all AVE values surpass the recommended threshold, indicating adequate convergent validity. We also examined the collinearity among the constructs by evaluating VIF values. According to Hair et al. (2019), VIF values should be less than 3. Table 4 illustrates that all VIF values were below the recommended threshold, indicating that the constructs were free from collinearity.

Discriminant validity of the constructs was assessed using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion, cross-loading, and the Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. As per the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (1981), each variable’s square root of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should exceed its correlation with other variables (Hair et al. 2022). Table 5 shows that all AVE values met this criterion, indicating sufficient discriminant validity. Furthermore, to achieve discriminant validity of the constructs, we examined the cross-loadings, as recommended by Hair et al. (2022). According to the results (included in Supplementary Material 1, Table S2), all constructs showed greater values for their corresponding indicators, indicating adequate discriminant validity. We also evaluated the HTMT to ensure the discriminant validity of the constructs. According to Franke and Sarstedt (2019), all HTMT values should be below the threshold of 0.90 to achieve discriminant validity. As shown in Fig. 2, the HTMT values were below 0.65, indicating adequate discriminant validity (Hair et al. 2019).

Assessment of structural model

We assessed the structural model by evaluating the results of hypothesis testing, the coefficient of determination (r2), and effect sizes (f2).

Hypothesis testing

Table 6 and Fig. 3 present the results of the hypothesis testing. According to the results, flood awareness had a significant and positive effect on perceived severity (beta = 0.137, p-value = 0.025), confirming H1. Similarly, flood awareness had a significant and positive effect on perceived vulnerability (beta = 0.354, p-value = 0.001), validating H2. However, past experiences of flood had an insignificant and negative effect on response efficacy (beta = −0.071, p-value = 0.200) and response cost (beta = −0.008, p-value = 0.459), rejecting H3 and H4, respectively. Nevertheless, perceived severity (beta = 0.121, p-value = 0.003), response efficacy (beta = 0.487, p-value = 0.001), and functional value (beta = 0.241, p-value = 0.001) had significant and positive effects on the intention to purchase flood insurance, thus, confirming H5, H7, and H9. However, perceived vulnerability (beta = −0.010, p-value = 0.404) and response cost (beta = −0.153, p-value = 0.000) had insignificant and negative effects on the intention to purchase flood insurance, thus rejecting H6 and H8. Finally, functional value (beta = 0.149, p-value = 0.007) and flood insurance purchase intention (beta = 0.211, p-value = 0.001) had significant and positive effects on flood insurance purchase behavior, thus validating H10 and H11, respectively.

The coefficient of determination (r 2)

According to Hair et al. (2019), r2 is a crucial metric for evaluating a structural model. A r2 value of 0.75 indicates a substantial impact, while 0.50 signifies a moderate impact, and 0.25 denotes a weak impact. The results of r2 presented in Table 6 reveal that the variances in perceived severity (r2 = 0.019) and perceived vulnerability (r2 = 0.125) were weakly correlated with flood awareness. The variances in response efficacy (r2 = 0.005) and response cost (r2 = 0.000) were weakly explained by past experiences with flooding. The variance in the intention to purchase flood insurance (r2 = 0.454) was moderately explained by perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, response efficacy, response cost, and functional value. The variance in flood insurance purchase behavior (r2 = 0.093) seemed to be weakly explained by functional value and the intention to purchase health insurance.

The effect size (f 2)

Cohen (1988) classified the effect size (f2) as small (0.2), medium (0.15), or large (0.35). The results of the effect sizes presented in Table 6 show that response efficacy (0.391) exemplified a large effect on the intention to purchase flood insurance, and flood awareness (0.143) had a medium effect on perceived vulnerability. Additionally, flood awareness (0.019) had a small effect on perceived severity. The effect sizes of past flood experiences (0.005 and 0.000, respectively) on response efficacy and response cost were small. Additionally, perceived severity (0.026), perceived vulnerability (0.000), response cost (0.041), and functional value (0.094) had small effects on the intention to purchase flood insurance. Finally, functional value (0.020) and the intention to purchase flood insurance (0.040) had small effects on flood insurance purchase behavior.

Multi group analysis

We employed Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the findings. Hair et al. (2021) suggested that PLS-MGA is an appropriate method for examining multiple moderating relationships, especially when analyzing subgroup differences. Moreover, the measurement invariance of the composite model (MICOM) method was employed prior to conducting MGA to evaluate the measurement invariance. The results of the MICOM analysis are included in the Supplementary Material (Table S3). The findings of the MICOM analysis show that all permutation p-values for gender and age are greater than 0.05, thereby establishing partial measurement invariance and continuing with the MGA analysis. As for the other two groups (education and income), several permutation p-values are less than 0.05, which confirms the lack of partial measurement invariance. Table 7 displays the MGA’s results. The results showed that the p-values of the path coefficients (difference: path coefficient for male vs. path coefficient for female) for gender were higher than 0.05, indicating no significant difference in all associations between male and female respondents. As for the respondents' age, the effect of past (flood) experience on response efficacy is significantly higher among the young people living in flood-prone areas (age 45 years or less) than that of the relatively older people living in flood-prone areas.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of core factors on flood insurance purchase intention and behavior in the context of a developing country like Malaysia. To achieve this, we developed 11 direct hypotheses. Among the direct hypotheses, eight were supported and three were rejected. This section highlights the key findings of this study.

According to the results, flood awareness had a significant positive effect on perceived severity (H1) and perceived vulnerability (H2). These findings align with previous studies by Bauer and Bernroider (2015) and Hanus and Wu (2016), which also established a correlation between awareness and perceived severity. The findings demonstrate that by enhancing flood awareness, individuals may have a greater understanding of the seriousness of flooding and recognizing the real risks associated with it. Disaster awareness is important for individuals residing in hotspots.

However, this study found insignificant effects of past flood experiences on response efficacy (H3) and response cost (H4). In terms of response efficacy, the findings indicated that some people may have developed a sense of fatalism owing to repeated flood events, which could have negatively affected their response efficacy. For example, past trauma may have hindered their belief. The variation in the severity of past flood experiences among respondents could also explain the lack of a significant effect. Some people may have had relatively minor past experiences that did not significantly influence their response costs. Moreover, the results regarding response cost are consistent with those of Li et al. (2019) and Yan and Tao (2021).

Nevertheless, this study found that perceived severity played an important role in influencing the intention to purchase flood insurance (H5). Typically, people with a higher level of perceived severity have a greater intention to behave proactively. Similarly, Savari et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2019) found that perceived severity significantly affected intention. Savari et al. (2022) stated that rural women’s perceived severity of forest degradation risks and potential future livelihood impacts increased their likelihood of exhibiting forest conservation behaviors.

According to this study’s findings, perceived vulnerability had an insignificant correlation with intention (H6). Other factors such as income, previous insurance experience, insurance costs, trust in insurance providers, and government policies may have overshadowed the influence of perceived vulnerability on purchase intention. These barriers include fear of illness and a lack of health insurance, which can exacerbate existing health disparities. In this case, perceived vulnerability did not influence the intention to adopt MHIS (Ndifon et al. 2020).

However, this study’s findings revealed that response efficacy played a pivotal role in flood insurance purchase intention (H7). This is consistent with the findings of Marikyan et al. (2022) and Savari et al. (2022). Marikyan et al. (2022) suggested that response efficacy had the strongest effect compared to other predictors in their study. When individuals perceive flood insurance as an effective policy for protecting their homes and belongings, they are more inclined to consider it as a viable solution, thereby increasing their intention to purchase flood insurance.

Nonetheless, the results showed an insignificant effect of response costs on the intention to purchase flood insurance (H8), which aligns with previous studies by Marikyan et al. (2022) and Savari et al. (2022). Residents of flood-prone areas require a high income to purchase flood insurance. This is due to the fact that they must pay regular premiums to keep the policy active, allowing them to file a claim in the future. Unfortunately, those with lower incomes and limited access to resources are often unable to afford this type of insurance, posing a significant barrier. Ultimately, this highlights how high costs can deter individuals from obtaining necessary protection.

However, functional value plays an essential role in fostering intention (H9) and purchase behavior (H10) toward flood insurance, as supported by the results of Han et al. (2017) for intention and Dangelico et al. (2021) for purchase behavior. These studies suggested that insurance policies should be well-developed in terms of quality and price. Consequently, individuals are more likely to purchase flood insurance to ensure that they are adequately protected during an unforeseen event in their lives.

Moreover, this study’s findings illustrate that purchase intention has a significant positive impact on flood insurance purchase behavior (H11), which is consistent with previous studies by Warganegara and Babolian (2022) and Wu et al. (2023). These findings imply that individuals with higher purchasing intentions are more likely to purchase flood insurance, emphasizing the need to understand and address purchasing intent to boost flood insurance purchases.

Theoretical implications

This study endeavored to broaden the scope of PMT by adopting a flood insurance perspective. The findings indicate that PMT can effectively elucidate and predict individuals’ responses to flood-related threats, thereby extending the applicability of the theory. Furthermore, this study enhances the existing knowledge by incorporating three additional constructs to examine flood insurance purchase intention and behavior. The inclusion of these constructs–flood awareness, past flood experience, and functional value–enriches the theoretical framework and contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the variables that influence flood insurance purchase decisions and subsequent actions, particularly functional value. This study highlights the central role that functional value, especially quality and price, plays in decision-making. Notably, many researchers have not considered this construct in their studies. Therefore, this study achieved better results by incorporating these constructs into the model.

Practical implications

This study’s findings hold considerable practical implications for policymakers, disaster management professionals, and insurance companies in encouraging the uptake of flood insurance. By recognizing the factors that influence the behavior of purchasing flood insurance, it allows the development of specific policies and incentive programs that encourage individuals and businesses in flood-prone regions to obtain coverage. This, in turn, can alleviate the financial burden on government agencies responsible for post-flood recovery efforts, enabling the effective allocation of resources for long-term resilience strategies for the communities.

These findings can help policymakers develop subsidy initiatives or tax breaks to make flood insurance more affordable for households with low incomes. Moreover, enforcing compulsory flood insurance in high-risk areas can provide financial security for the most at-risk communities. Enhancing regulatory frameworks to guarantee equitable claims processing and clear pricing can boost public confidence in insurance companies, leading to greater penetration. This research highlights the significance of functional value in the intention and behavior of purchasing flood insurance. Consequently, insurance firms can offer tailored, adaptable payment plans or microinsurance products designed for various income levels, particularly in emerging nations with low penetration. In addition, community-oriented education programs can be established to enhance awareness and dispel myths regarding flood insurance’s cost and advantages.

This study illuminates the importance of functional value in flood insurance purchase intention and behavior with the ultimate goal of assisting insurance firms in devising more effective marketing strategies, designing more appealing insurance offerings, and enhancing accessibility, particularly in emerging economies where insurance penetration remains low. Moreover, this study contributes to the advancement of methods for mitigating catastrophe risk by linking flood awareness, past experiences, and protective actions, indicating that disaster management agencies ought to work with insurance companies to offer post-flood enrollment initiatives for impacted residents. Community outreach initiatives can be enhanced by including actual case studies of flood survivors who gained from insurance, emphasizing the significance of proactive risk management. Through the adoption of these evidence-driven strategies, policymakers, insurers, and disaster management experts in Malaysia and other emerging nations can advance disaster readiness, boost flood insurance uptake, and reinforce financial resilience.

Policy implications

Recommending a flood insurance policy for Malaysia requires careful consideration of several factors. It is important to acknowledge that flood insurance is currently voluntary in this country. Existing flood disaster management policies are based on a top-down approach that does not fully meet the expectations of flood victims. Moreover, the government’s relief system for flood victims in Malaysia has proven ineffective, highlighting the need for improvement in the current strategy. While flood insurance is recognized as an effective measure for reducing the financial impact on individuals during floods, its penetration for residential properties in Malaysia remains low, despite severe annual flooding. A significant obstacle to adoption is cost, since numerous households, especially those in low-income brackets, find it difficult to afford coverage. To tackle this issue, the government might implement subsidies or tax exemptions to enhance the financial accessibility of flood insurance. Moreover, reinforcing regulatory systems to guarantee transparency and equity in claim resolutions could boost public confidence in insurance companies. This underscores the need for more comprehensive and integrated flood risk management, including the development of flood-resilience policies for Malaysian cities. Finally, the implications and insights drawn from this study must be considered to improve flood management systems in Malaysia. Therefore, developing a flood insurance policy that considers the voluntary nature of flood insurance, addresses inadequacies in existing disaster management policies, and seeks to increase the penetration of flood insurance in residential buildings is essential.

Limitations and future studies

Although this study provides valuable insights for researchers and practitioners, it has some limitations. First, its limited geographical scope on the flood-prone areas of Klang Valley may hinder the generalizability of the results to other regions or global contexts. Future studies should focus on other flood-prone areas. Second, although MGA identified differences between groups, the distinctions were not thoroughly investigated in this study. These differences should be considered in future studies. Third, the limited number of constructs examined in this study is another shortcoming of the integration of PMT. Thus, future studies could broaden the scope by including price and insurance literacy as independent variables and considering functional value as a moderator, which will provide an in-depth analysis. Finally, this study employed a quantitative approach; however, a mixed-methods technique might offer better results.

Conclusion

The increasing frequency and severity of global flooding have led to a greater reliance on flood insurance to protect individuals, particularly those living in flood-prone areas. While existing literature extensively covers flood-related studies, a limited number of these have integrated an insurance perspective, particularly regarding flood insurance. Therefore, this study examined the factors influencing flood insurance purchase intention and behavior in the context of an emerging economy like Malaysia, using PMT. Drawing upon empirical data gathered from 331 respondents residing in flood-prone areas of Klang Valley, this study significantly contributes to the existing body of knowledge by achieving five research objectives. First, it demonstrated that flood awareness significantly influenced threat appraisal. Second, past flood experience was found to have an insignificant influence on coping appraisal. Third, the study revealed that threat and coping appraisals, regarded as crucial constructs, significantly influenced the intention to purchase flood insurance, with the exception of perceived vulnerability. Fourth, functional value significantly influenced flood insurance purchase intention and behavior. Fifth, this study proves that intention plays a vital role in influencing purchase behavior. These findings provide valuable recommendations for practitioners to develop and implement strategies and educational campaigns to raise flood awareness among residents living in flood-prone areas of Malaysia. These campaigns should provide information on the frequency, severity, and potential consequences of flooding, along with the benefits of obtaining flood insurance. It is essential to collaborate with government agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and insurance providers to conduct workshops, seminars, and community outreach programs educating people on the importance of flood insurance.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material (S3. Dataset), further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

References

Alam Z, Begum H, Masud MM et al. (2020) Agriculture insurance for disaster risk reduction: a case study of Malaysia. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 47:101626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101626

Aziz S, Husin MM, Hussin N et al. (2019) Factors that influence individuals’ intentions to purchase family takaful mediating role of perceived trust. Asia Pac J Mark 31(1):81–104. https://doi-org.eresourcesptsl.ukm.remotexs.co/10.1108/APJML-12-2017-0311

Banerski G, Abramczuk K (2023) Persuasion illustrated: motivating people to undertake self-protective measures in case of floods using 3D animation focused on components of protection motivation theory. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 89:103575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103575

Bauer S, Bernroider EW (2015) The effects of awareness programs on information security in banks: the roles of protection motivation and monitoring. In: Tryfonas, T, Askoxylakis, I (eds) Human Aspects of Information Security, Privacy, and Trust 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 9190. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20376-8_14

Bekkers L, Goede S, Huurne EM et al. (2023) Protecting your business against ransomware attacks? Explaining the motivations of entrepreneurs to take future protective measures against cybercrimes using an extended protection motivation theory model. Comput Secur 127:103099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2023.103099

Bhattacharyya A, Hastak M (2024) Empirical causal analysis of flood risk factors on U.S. flood insurance payouts: implications for solvency and risk reduction. J Environ Manag 352:120075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120075

Bijani M, Mohammadi-Mehr S, Shiri N (2022) Towards rural women’s pro-environmental behaviors: application of protection motivation theory. Glob Ecol Conserv 39:e02303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02303

Bockarjova M, Steg L (2014) Can protection motivation theory predict pro-environmental behavior? Explaining the adoption of electric vehicles in the Netherlands. Glob Environ Change 28:276–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.010

Bradt JT, Kousky C, Wing OE (2021) Voluntary purchases and adverse selection in the market for flood insurance. J Environ Econ Manag 110:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102515

Chan NW (2015) Impacts of disasters and disaster risk management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods. In: Aldrich, D, Oum, S, Sawada, Y (eds) Resilience and Recovery in Asian Disasters. Risk, Governance and Society, Vol. 18. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55022-8_12

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge: New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Dangelico RM, Nonino F, Pompei A (2021) Which are the determinants of green purchase behaviour? A study of Italian consumers. Bus Strategy Environ 30(5):2600–2620. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2766

Delfiyan F, Yazdanpanah M, Forouzani M et al. (2020) Farmers’ adaptation to drought risk through farm–level decisions: the case of farmers in Dehloran County, Southwest of Iran. Clim Dev 13(2):152–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1737797

de Ruig LT, Haer T, de Moel H et al. (2023) An agent-based model for evaluating reforms of the National Flood Insurance Program: a benchmarked model applied to Jamaica Bay, NYC. Risk Anal 43(2):405–422. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3820691

Department of Statistics Malaysia (2023) Learn More about Your Area Today! (Online). Retrieved from https://open.dosm.gov.my/dashboard/kawasanku

Diakakis M, Skordoulis M, Kyriakopoulos P (2022) Public perceptions of flood and extreme weather early warnings in Greece. Sustainability 14(16):1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610199

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Franke G, Sarstedt M (2019) Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: a comparison of four procedures. Internet Res 29(3):430–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0515

Ghaniana M, Ghoochania OM, Dehghanpour M et al. (2020) Understanding farmers’ climate adaptation intention in Iran: a protection motivation extended model. Land Use Policy 94:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104553

Hair JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM et al (2022) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications

Hair JF, Hult GT, Ringle CM et al (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 1-197. Springer: Cham

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M et al. (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hampton S, Curtis J (2022) A bridge over troubled water? Flood insurance and the governance of climate change adaptation. Geoforum 136:80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.08.008

Han L, Wang S, Zhao D et al. (2017) The intention to adopt electric vehicles: driven by functional and non-functional values. Transp Res A Policy Pr 103:185–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.05.033

Hanus B, Wu Y (2016) Impact of users’ security awareness on desktop security behavior: a protection motivation theory perspective. Inf Syst Manag 33(1):2–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2015.1117842

Heidenreich A, Masson T, Bamberg S (2020) Let’s talk about flood risk—evaluating a series of workshops on private flood protection. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 50:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101880

Hossain MS, Alam GM, Fahad S et al. (2022) Smallholder farmers’ willingness to pay for flood insurance as climate change adaptation strategy in Northern Bangladesh. J Clean Prod 338:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130584

Hudson P, Thieken AH (2022) The presence of moral hazard regarding flood insurance and German private businesses. Nat Hazards 112:1295–1319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05227-9

Hudson P, Hagedoorn L, Bubeck P (2020) Potential linkages between social capital, flood risk perceptions, and self-efficacy. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 11(3):251–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00259-w

Janmaimool P (2017) Application of protection motivation theory to investigate sustainable waste management behaviors. Sustainability 9(7):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071079

Kazaure MA (2019) Extending the theory of planned behavior to explain the role of awareness in accepting Islamic Health Insurance (Takaful) by microenterprises in Northwestern Nigeria. J Islam Acc Bus Res 10(4):607–620. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-08-2017-0113

Khan SN, Mohsin M (2017) The power of emotional value: exploring the effects of values on green product. J Clean Prod 150(2017):65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.187

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kousky C, Netusil NR (2023) Flood insurance literacy and flood risk knowledge: evidence from Portland, Oregon. Risk Manag Insur Rev 26(2):175–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/rmir.12242

Landry C, Petrolia DR, Turner D (2021) Flood insurance market penetration and expectations of disaster assistance. Environ Resour Econ 79:357–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00565-x

Landry C, Turner D (2020) Risk perceptions and flood insurance: insights from homeowners on the Georgia Coast. Sustainability 12(24):10372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410372

Li L, He W, Xu L et al. (2019) Investigating the impact of cybersecurity policy awareness on employees’ cybersecurity behavior. Int J Inf Manag 45:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.017

Lim K, Zakaria N, Foo K (2019) A shared vision on the historical flood events in Malaysia: integrated assessment of water quality and microbial variability. Disaster Adv 12(8):11–20

Lindell MK, Hwang SN (2008) Households’ perceived personal risk and responses in a multihazard environment. Risk Anal 28(2):539–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01032.x

Maduku DK, Mbeya S (2023) Understanding family takaful purchase behaviour: the roles of religious obligation and gender. J Financ Serv Mark (Online Version) 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-023-00213-z

Mamun AA, Rahman MK, Munikrishnan UT et al. (2021) Predicting the intention and purchase of health insurance among Malaysian working adults. Sage Open 11(4):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061373

Marikyan D, Papagiannidis S, Rana OF et al. (2022) Blockchain adoption: a study of cognitive factors underpinning decision making. Comput Hum Behav 131:107207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107207

Masud MM, Ahsan MR, Ismail NA et al. (2021) The underlying drivers of household purchase behaviour of life insurance. Soc Bus Rev 16(3):442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-08-2020-0103

Mendes-Da-Silva W, Lucas EC, Carvalho JV (2021) Flood insurance: the propensity and attitudes of informed people with disabilities towards risk. J Environ Manag 294:113032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113032

Ndifon NM, Bawack RE, Kamdjoug JR (2020) Adoption of Mobile Health Insurance Systems in Africa: evidence from Cameroon. Health Technol 10:1095–1106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-020-00455-0

Neisi M, Bijani M, Abbasi E et al. (2020) Analyzing farmers’ drought risk management behavior: evidence from Iran. J Hydrol 590:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125243

Pakmehr S, Yazdanpanah M, Baradaran M (2020) How collective efficacy makes a difference in responses to water shortage due to climate change in Southwest Iran. Land Use Policy 99:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104798

Podsakoff PM, Organ DW (1986) Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manag 12(4):531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Raikes J, Henstra D, Thistlethwait J (2023) Public attitudes toward policy instruments for flood risk management. Environ Manag 72:1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01848-3

Rainear AM, Christensen JL (2017) Protection motivation theory as an explanatory framework for proenvironmental behavioral intentions. Commun Res Rep. 34(3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1286472

Raza SA, Ahmed R, Ali M et al. (2020) Influential factors of Islamic Insurance Adoption: an extension of theory of planned behavior. J Islam Mark 11(6):1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2019-0047

Richerta C, Erdlenbrucha K, Figuièresb C (2016) The determinants of households’ flood mitigation decisions in France—on the possibility of feedback effects from past investments. Ecol Econ 131:342–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.09.014

Rifas AH, Rahman AA, Buang AH et al (2023) Business Entrepreneurs’ Intention towards Takaful Participation to Mitigate Risk: A Study in Sri Lanka based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J Islam Account Bus Res (Online Version) https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-02-2022-0034

Rogers RW (1975) A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J Psychol 91(1):93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

Savari M, Naghibeiranvand F, Asadi Z (2022) Modeling environmentally responsible behaviors among rural women in the forested regions in Iran. Glob Ecol Conserv 35:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02102

Shafiei A, Maleksaeidi H (2020) Pro-environmental behavior of university students: application of protection motivation theory. Glob Ecol Conserv 22:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00908

Shao J, Hoshino A, Nakaide S (2022) How do floods affect insurance demand? Evidence from flood insurance take-up in Japan. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 83:103424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103424

Spector PE (2006) Method variance in organizational research: truth or urban legend? Organ Res Methods 9(2):221–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955

Suki NM (2016) Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: structural effects of consumption values. J Clean Prod 132:204–2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.087

Tesselaar M, Botzen W, Robinson PJ, Aerts JC (2022) Charity hazard and the flood insurance protection gap: an EU Scale Assessment under climate change. Ecol Econ 193:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107289

Thistlethwaite J, Henstra D, Brown C et al. (2020) Barriers to insurance as a flood risk management tool: evidence from a survey of property owners. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 11:263–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00272-z

Veeravalli S, Chereni S, Sliuzas R et al. (2022) Factors influencing flood damage mitigation among micro and small businesses in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 82:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103315

Wang J, Liu-Lastres B, Ritchie BW et al. (2019) Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: an application of the full protection motivation theory. Ann Tour Res 78:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102743

Wang P, Liu Q, Qi Y (2014) Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: a survey of the rural residents in China. J Clean Prod 63:152–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.007

Warganegara DL, Babolian R (2022) Factors that drive actual purchasing of groceries through e-commerce platforms during COVID-19 in Indonesia. Sustainability 14(6):1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063235

Wu M, Mamun AA, Yang Q et al. (2023) Modeling the intention and donation of second-hand clothing in the context of an emerging economy. Sci Rep. 13:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42437-y

Yan S, Tao X (2021) The impact of farmers’ assessments of risk management strategies on their adoption willingness. J Integr Agric 20(12):3323–3338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(21)63749-8

Zhang F, Lin N, Kunreuther H (2023) Benefits of and strategies to update premium rates in the US national flood insurance program under climate change. Risk Anal 43(8):1627–1640. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14048

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Ministry of Education, Malaysia (Grant Code: FRGS/1/2022/WAB02/UKM/02/3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahalasmi Radhakrishnan, Muhammad Mehedi Masud, and Zafir Khan Mohamed Makhbul: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft Preparation. Mohammad Nurul Hassan Reza, Abdullah Al Mamun: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Kembangan Malaysia approved this study (Ref. No. UKM/PPI/111/8/JEP-2023-463) on 28th July 2023, to conduct the survey on major flash flood victims living in Peninsular Malaysia. This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for participation was obtained from respondents who participated in the survey. The survey was conducted from the beginning of the 4th september to 27th october 2023 among residents of flood-prone areas in Klang Valley, Malaysia.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Radhakrishnan, M., Reza, M.N.H., Al Mamun, A. et al. Behavioral insights into insurance purchase among flash flood survivors in Malaysia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 783 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05129-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05129-8