Abstract

This paper aimed to investigate how awareness of negative consequences, subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control dimensions influence pro-environmental behavioral intention to conserve four world heritage sites (Jeddah, Mada’in Saleh, Diriyah, and Jubbah) and to identify the spatial distribution of archeological sites in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from a simple random sample of local residents in the four sites that was then subjected to multiple statistical analyses to test the hypotheses. Two thousand, three hundred, and forty-two local inhabitants responded to the two thousand, seven hundred, and fifty questionnaires that were delivered, accounting for a response rate of 85.1%, resulting in two thousand, two hundred, and ninety valid questionnaires for data analysis after closely examining the survey. Structural analysis revealed significant relationships within the adapted model, particularly in the context of heritage relics. The findings of PLS-SEM showed a positive influence of attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and awareness of negative consequences on pro-environmental behavioral intention. In addition, the findings revealed that attitude significantly moderates the impact of awareness of negative consequences on pro-environmental behavioral intention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, academics and professionals have shown increased interest in managing and preserving heritage sites (Hsu et al., 2022). Heritage-based tourism promotes sustainable development, boosting local economies and preserving natural, cultural, and historic resources, with potential positive and negative impacts depending on management and development strategies (Zhao et al., 2020). Heritage refers to the inherited knowledge, skills, and experiences from the past, which will be beneficial and influential for future generations (UNESCO, 2002).

Historical sites represent the past and should be preserved for their historical, cultural, and ethnic significance. Cooperation with locals is crucial for conserving these sites as important resources for income (Oviedo and Puschkarsky, 2017).

The general assembly of states parties to the World Heritage Convention and the World Heritage Committee, which has overseen the United Nations educational, scientific, and cultural organization (UNESCO) since its founding in 1945, have been tasked with safeguarding the world’s numerous world heritage sites. A total of one thousand, one hundred and twenty-one heritage sites are registered in one hundred and sixty-seven nations as of 2021, encompassing cultural, natural, and mixed categories (De Ascaniis et al., 2018). Cultural World Heritage Sites are popular tourist destinations due to their universal qualities, requiring conservation and sustainable development for growth, as stated by the 1972 World Heritage Convention (De Ascaniis et al., 2018; UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2008).

In particular, UNESCO World Heritage Sites (WHSs) have been recognized as a component of the growth strategy, with the possibility of further sites being inscribed by 2030 (Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, 2016). The Hegra Archaeological Site (al-Hijr / Madā ͐ in Ṣāliḥ), At-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah, Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah, Rock Art in the Hail Region of Saudi Arabia, and Al-Ahsa Oasis, a Changing Cultural Landscape, are currently the eight WHSs that have been inscribed. Ḥimā Cultural Area, ‘Uruq Bani Ma’arid, Al-Faw Archaeological Area’s Cultural Landscape (Unesco, 2025). Being listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List (WHL), these Saudi Heritage Sites served as evidence that the Kingdom’s urban heritage should be preserved in order to serve as a testament to the region’s residents’ inventiveness, cultural capacity, and inventiveness (Ibrahim, 2018).

Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) define pro-environmental behavior as actions aimed at minimizing negative impacts on built and natural environments (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). Ramkissoon et al. (2012) suggest that enhancing pro-environmental actions can safeguard cultural and natural resources for future generations (Ramkissoon et al., 2012). The development of eco-conscious behavior in heritage tourism is crucial for preserving cultural assets, benefiting the local economy, and understanding the factors influencing pro-environmental behavior formation processes, thereby benefiting destination managers in promoting sustainable practices (Lee, 2011). The increasing number of visitors to cultural and historical sites may have negative impacts, necessitating a balance between visitor numbers, authenticity, and preservation (Alazaizeh et al., 2016). Jiang et al. (2023) highlight that heritage sites, offering genuine experiences, are often fragile, and pro-environmental behaviors are a significant factor in historic tourism (Jiang et al., 2023). Researching locals’ pro-environmental actions is crucial for sustainable tourism development, as they are key players in environmental protection at tourist destinations (de los Angeles Somarriba-Chang and Gunnarsdotter, 2012).

Heritage tourism requires sustainable management of heritage resources and positive attitudes from local populations towards environmental responsibility and cultural heritage protection (McKercher and Ho, 2011). According to certain academics, residents perform a vital role in managing heritage sites for community sustainability and conservation benefits (McKercher and Ho, 2011; Nicholas et al., 2009; Su and Wall, 2014). Cooperation and compromise among parties are crucial for preserving and managing registered sites, with active community participation being essential for enlisted cultural places (Jang and Mennis, 2021). The planned behavior theory research on pro-environmental behavioral intention in heritage sites, especially in Saudi Arabia, has received limited attention, and the relationship between intention and consequence awareness is understudied. Few studies have explored the creation and administration of heritage sites, nor have they assessed residents’ heritage responsibility behaviors in various contexts (Landorf, 2009; Zhang et al., 2024; Zhong and Chen, 2017).

Although previous research has linked tourists to eco-friendly practices (Liu et al., 2020; Li and Wu, 2020; Han, 2015), there is a dearth of comprehensive research on how to encourage locals to actively preserve the heritage environment and what elements influence heritage protection. Little is known about the willingness of locals to engage in heritage site preservation while they are there. At the same time, citizens’ involvement in maintaining these places is anticipated to improve the heritage sites’ cleanliness and quality by completing tasks.

To fill this gap, this study’s main objective is to develop a model integrating awareness of negative consequences into the TPB framework, determine the constructs influencing local residents’ pro-environmental behavioral intention, and investigate the moderating effect of attitudes between the awareness of negative consequences and pro-environmental behavioral intention. This work offered an extended version of the planned behavior model, a social-psychological model of altruistic conduct that has been frequently used to explain pro-environmental behavior, emphasizing the importance of residents’ understanding and appreciation of heritage resources, thereby promoting sustainable tourism development (Ramkissoon et al., 2012). Heritage protection has been identified as a sustainable strategy in the global agenda (Nurse, 2006; United Nations, 2012). While research on sustainable development is well established, cultural heritage is still not given enough attention in urban development literature (Nijkamp and Riganti, 2008), nor is there a scientific evaluation methodology to look into the relationship between sustainable development and heritage management (Appendino, 2017).

Using the literature on environmental psychology and tourism, a conceptualization of sustainable behavior in the specific context of heritage tourism is offered in order to understand the general and site-specific features of the sustainable conduct of visitors to cultural places. By addressing this important issue from a traditional cultural heritage resource protection and conservation perspective, this study broadens our understanding of the antecedents of heritage resource conservation practices.

This study has several contributions as follows: 1. This study is unique among prior research contributions since it is the first attempt in the heritage tourism area to analyze residents’ pro-environmental behavioral intention to protect heritage sites by extending the planned behavior theory. Therefore, this study examines awareness of negative consequences effects as an antecedent variable that influences pro-environmental behavioral intention. 2. The study’s conclusions support those of previous research and the relevant literature on sustainable tourism. 3. The results of this study have theoretical value because the process of determining people’s eco-friendly behavioral intentions to preserve world heritage sites was initially described in Saudi Arabia. 4. This study aids tourism organizations and heritage managers in developing sustainable heritage tourism plans based on responsible visitors’ behavior.

Tourist behavior and legal, financial, educational, persuasive, and civil measures supporting heritage management’s sustainability efforts may significantly influence the operationalization of sustainable tourism development at cultural sites. The text provides a summary of the relevant theory, discusses the questionnaire design, data collection process, and theoretical framework, and presents key findings, implications, limitations, and recommendations for further research.

Literature review

Tourism, the negative effects of cultural over tourism and the conflicts between residents and tourists

One of the biggest and fastest-growing sectors of the global economy is tourism. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), there will be over 1.8 billion foreign visitors by 2030 (Taiminen, 2018). From a regional and global standpoint, the tourist industry offers enormous benefits (Hosseini et al., 2021). According to World Travel and Tourism Council (2020), the tourism industry currently makes up a significant part of the economies of many countries worldwide and is essential to their growth (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2020). Due to its beneficial function in promoting various forms of development (physical, social and cultural, economic, and environmental) in many nations, tourism is a vibrant and significant business for many of them (Al-Saad et al., 2014).

According to Radojević (2015), international tourism is the biggest source of export revenue worldwide and plays a significant role in the balance of payments for the majority of countries (Radojević, 2015). In the short and medium term, the tourist industry is thought to be among the most prepared to boost the nation’s foreign exchange reserves, generate employment opportunities, and contribute to the targeted growth rates (Alsarayreh, 2019). Since the tourist sector contributes more than 10% of the global GDP and a comparable portion of global employment, its socioeconomic importance cannot be understated at this time, regardless of whether it is essential or unnecessary (Higgins-Desbiolles et al., 2019) for the human economy (World Economic Forum, 2019).

According to Apostolopoulos (1996), the tourism industry’s multiplier effects drive an economic chain reaction that starts with purchases from other businesses and continues with the expenditure of profits, employee benefits, and even dividends (Apostolopoulos, 1996). Because of its cross-cultural nature, tourism can promote tolerance and fraternalism across cultures and civilizations while also advancing the globalization process and eradicating prejudice and self-exaltation. Additionally, the money produced by the tourism supply chain can help support sustainable resource use by offsetting the cost of maintaining and protecting natural and cultural assets (Hosseini et al., 2021). Additionally, tourism is a useful strategy for reducing stress and anxiety from day-to-day living in human society (Büscher and Fletcher, 2017). Several definitions have been proposed in the literature thus far, even though excessive tourism is a relatively recent phenomenon and a subject of scientific study (Peeters et al., 2018; Milano et al., 2018; Milano et al., 2019; Mihalic, 2020).

The majority of specialists think it’s difficult to define over tourism in a way that is generally acknowledged (Żemła, 2020). The content is a rehash of previous impact studies, despite the term being new, according to research (Capocchi et al., 2020; Dredge, 2017; Perkumiene and Pranskuniene, 2019). Consequently, it may be said that attempts to explain over tourism are still not universally accepted by tourism researchers (Seyhan, 2023). Over tourism is defined as “the impact of tourism on a destination, or parts thereof, that excessively influences the perceived the quality of life of citizens and/or the quality of visitors’ experiences in a negative way” (UNWTO, 2018). “Scholars believe that this description sets it apart from mass tourism, where, for instance, the experience’s quality is not in jeopardy (Milano et al., 2019; Veríssimo et al., 2020).

Over tourism is defined even more broadly by Peeters et al. (2018) as “the impact of tourism, at certain times and in certain locations, exceeds physical, ecological, social, economic, psychological, and/or political capacity thresholds.” According to Majdak et al. (2023), the definitions above demonstrate two essential features of the phenomenon: a significant and excessive increase in the number of visitors to a certain region and a matching decrease in the standard of living for both locals and visitors [Majdak et al., 2023).

The aforementioned characteristics allow for the identification of two essential components that define the phenomenon being described: a notable and excessive rise in the number of visitors to a particular location, either permanently or temporarily, and the corresponding decline in the local community’s standard of living. It is also important to remember that unfavorable sentiments might impact not just the inhabitants who host the receiving sites but also the tourists themselves, who travel in an environment where tourist pressure is higher (Majdak et al., 2023).

Concerns regarding the possible, actual, and perceived harm that tourism may do to host locations have long been voiced by scholars and professionals (Seyhan, 2023; Hughes et al., 2021). According to Markusen (2003), the phrase “over tourism,” which first surfaced in the summer of 2017, is hard to describe exactly (Markusen, 2003). The academic literature, newspapers, and other publications swiftly embraced it (Frey and Briviba, 2021; Koens et al., 2018).

Up until now, there have only been a few scholarly articles written on this subject, but some worthwhile recent research has been done (Milano et al., 2019; Koens et al., 2018; Seraphin et al., 2020; Séraphin and Yallop, 2021). Although overtourism is not a new issue, it has grown significantly, as several authors have pointed out (Milano et al., 2019; Koens et al.,2018; Dodds and Butler, 2019; Goodwin, 2017). Cultural heritage can be viewed as an interaction link between archeology, the environment, and indigenous people that dates back thousands of years. It is more than just a legacy from the past; it is a tangible representation of former lives (Al-Saad et al., 2014).

Three main areas can be used to describe how tourism affects heritage sites: social and cultural, economic, and environmental (Mason, 2020). Degradation at heritage sites can be divided into three categories based on the situation: biological (pollution), physical-chemical (graffiti, waste, littering, and vandalism), and mechanical (wear, tear, and abrasion) (ICCROM, 2016; Ashworth, 1996). Tourists’ behavior negatively impacts historic centers, causing noise, waste, traffic congestion, and increased pollution (Frey and Briviba, 2021).

Additionally, research by Kuščer and Mihalič (2019) found that because of traffic, pollution, and overpopulation, locals in Ljubljana had unfavorable opinions of tourists and wanted to leave Slovenia’s capital. Additionally, the high volume of visitors causes art sites to be overused (Frey and Briviba, 2021). The authenticity that visitors seek and identify with a cultural site is often threatened or even destroyed by cultural over tourism (Frey and Briviba, 2021). When it comes to archeological sites, such as Petra, Jordan, or Machu Picchu, the sheer number of visitors and their misbehavior often lead to destruction (Haddad et al., 2019). The same negative pressures usually only damage historic floors or buildings, like Westminster Abbey in London, in historic city centers (Fawcett, 1998).

A cultural heritage site, such as an archeological monument, a historic structure, or an old artifact, cannot be replicated or restored in its original form if it has been damaged or altered, according to Benhamou (2011). Venice offers a remarkable illustration. The city’s air quality is very bad due to emissions from cruise ships, whose engines also run when they are anchored in port, and the exhaust fumes harm the buildings (Asero and Skonieczny, 2017). Nonetheless, there are also records of other types of cultural site destruction. In Seoul’s Ihwa Mural Village, locals demolished two of the most popular cultural attractions as a way to voice their displeasure with over tourism (Park and Kovacs, 2020).

Residents’ daily lives are greatly impacted by the trend, which also fosters hostile interactions between locals and tourists (Capocchi et al., 2020; Park and Kovacs, 2020). The identity of the local population is at risk due to the massive influx of tourists. Locals and visitors may become hostile as a result (Frey and Briviba, 2021).

As seen in many European towns, locals’ negative attitudes toward visitors increase as a result of the congestion caused by tourists (Kuščer and Mihalič, 2019). Additionally, it limits communication and the willingness to greet visitors. As a result, the likelihood of “good” crowding is reduced, which lowers the usefulness of tourists (Russo, 2000).

If the local community does not profit from tourism or if they see an imbalance between the positive effects of tourism and the negative effects of over tourism, residents may feel alienated. This can affect how locals tolerate tourists; in places like Venice, Dubrovnik, and Barcelona, locals have even demonstrated against over tourism (Kuščer and Mihalič, 2019).

Most of Jordan’s cultural heritage sites, particularly those situated in urban areas like the Jerash Archaeological Site, are showing signs of conflict between sustainable tourism and urban growth (Al-Saad et al., 2014). There was a dispute about the local use of the protected beach because of recent research conducted at two archeological sites on the French coast of Lac de Chalain. As noted by Wallace and Russell (2004), this tension at Lac de Chalain emerged when tourism growth ran counter to the goals of environmental preservation and archeology. Residents’ perspectives and attitudes about tourism development were found to be varied in small towns with cultural assets, according to research on the subject (Wise et al., 2017). Additionally, research by Kuščer and Mihalič (2019) found that because of traffic, pollution, and overpopulation, locals in Ljubljana had unfavorable opinions of tourists and wanted to leave Slovenia’s capital (Kuščer and Mihalič, 2019).

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

The theory of planned behavior

The theory of reasoned action suggests that an individual’s attitude and subjective norm significantly influence their behavioral intention, with volitional control predicting their behavior and decision-making (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). The TRA was initially designed to predict behavioral intentions under volitional control (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980), but was modified in 1985 to account for uncontrollable factors like lack of time, adding perceived behavioral control as a third predictive component (Ajzen and Madden, 1986).

The planned behavior theory, derived from the theory of reasoned action, suggests that individuals act rationally when considering the consequences of their choices (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the theory of perceived behavior (TPB) both suggest rational decision-making, but TPB incorporates perceived behavioral control as an antecedent of behavioral intention (Ajzen, 1991).

The theory of planned behavior suggests that human actions can be predicted by integrating psychological beliefs, including attitudes, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and intention, to predict outcomes (Ajzen, 1991; Armitage and Conner, 2001). The theory of planned behavior (TPB) explains human behavior as flexible, incorporating additional variables or changing routes to account for variation in behavior or intention, even after initial structures are considered (Clark et al., 2019). The concept suggests that by adjusting paths and adding new constructs, the theoretical mechanism of TPB and the roles of original variables can be better understood. With a mean effect size of 0.50 for behavioral changes and effect sizes ranging from 0.14 to 0.68 for changes in antecedent variables (behavioral, normative, and control beliefs, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention), Steinmetz et al. (2016) validated the efficacy of TPB-based interventions (Steinmetz et al., 2016). De Leeuw et al. (2015) demonstrated that attitudes, descriptive norms, and perceived control were the most important predictors of pro-environmental intents (De Leeuw et al., 2015).

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a widely recognized theory that predicts visitors’ pro-environmental intentions and activities in various tourism contexts (Li and Wu, 2020). TPB suggests that an individual’s behavior is primarily influenced by their intention to perform a specific activity, which is shaped by their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Han, 2015). The TPB, developed 30 years ago, is used to analyze pro-environmental behaviors like alternative transportation, waste recycling, water and energy conservation, and reduced carbon consumption (Jiang et al., 2019).

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) links pro-environmental conduct and intention, suggesting that changing intention can positively impact pro-environmental behavior. Therefore, protected area managers can identify factors influencing environmental behavior and suggest actions (De Leeuw et al., 2015).

Hypotheses development

Attitude and pro-environmental behavioral intention

Attitude is a personal factor influenced by positive or negative feelings during a particular behavior, encompassing psychological assessment of its effectiveness (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). Attitudes are considered reliable indicators of intentions, as supported by empirical research and the theory of TPB (Halpenny et al., 2018). Positive attitudes drive behavioral intentions, as per the expectation-disconfirmation paradigm (Wong and Tzeng, 2021). Environmental attitudes increase an individual’s inclination towards sustainable conduct, according to Hu et al. (2018). Attitude influences pro-environmental actions, with environmentally conscious visitors more likely to act responsibly and support sustainable practices, as suggested by Dixit and Badgaiyan (2016).

Researchers and policymakers are increasingly studying residents’ attitudes towards tourism, focusing on specific tourist destinations (Garcia Filho et al., 2016). Good attitudes toward tourism are found to increase support for tourism development and development within these spatial settings (Andereck and Vogt, 2000). Wu and Chen (2018) find that positive attitudes towards tourism, particularly the benefits it provides, significantly enhance residents’ behavioral intention to support tourism development (Wu and Chen, 2018). Ajzen and Fishbein’s (1980) study on Huangshan Mountain in China reveals that tourists’ environmental behavior attitudes positively impact their responsible environmental behavioral intentions (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Hasan et al. (2021) used the TPB partial utility framework to predict tourists’ actions at Lalbagh Fort in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Results showed attitude towards visits is not significant but significantly influenced behavioral intention. The study finds that positive attitudes towards the tourism industry positively impact citizens’ support for the Daming Palace Heritage Park, despite negative attitudes towards the industry (Hasan et al. (2021). Lee et al. (2021) and Rao et al. (2022) find strong support for heritage visitor intentions and a positive correlation between attitudes and preservation intentions (Lee et al., 2021; Rao et al., 2022). Lee et al. (2023) find that locals’ behavioral intention towards preserving agricultural historical tourist resources is significantly influenced by their attitude.

Using the norm activation model as the theoretical framework and an integrated theory of planned behavior, Arkorful et al. (2023) examine household waste separation behavior. The results showed that behavioral intention and attitude are positively correlated. According to research by Zheng et al. (2017), people’s propensity to engage in environmental protection practices is positively impacted by their attitudes regarding environmental protection.

In investigating tourists’ intentions to replace single-use plastics with reusable substitutions, Adam (2023) reports that attitudes toward reusable alternatives positively affected intentions to use reusable alternatives. On the other hand, in order to investigate the predictive validity of TPB in the pro-environmental setting, Juschten et al. (2019) collected data from 877 individuals. The results showed that attitude is the sole unimportant predictor of behavioral intention. Based on 900 useful responses from high-rise residents in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Razali et al. (2020) proposed a significant positive relationship between attitude and waste separation behavior. Nevertheless, they discovered that the attitude seemed to have the least impact on the behavior of waste separation. Based on the above, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1: Local residents’ attitudes affect positively their pro- environmental behavioral intentions.

Subjective norms and pro-environmental behavioral intention

Subjective norms in TPB refer to the social pressure to participate in a specific activity, influenced by significant individuals like family, friends, coworkers, or business partners, indicating the likelihood of approval or disapproval of a person’s behavior (Fenitra et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2023).

Subjective norms in tourism research positively impact tourists’ desire to behave sustainably by influencing their surroundings in tourist destinations (Wang et al., 2020). Social norms and subjective standards influence tourists’ travel intentions to heritage destinations, with family and friends being influential in shaping their decisions, often due to social pressure and approval concerns (Nyborg, 2020). Research shows subjective norms, such as eco-friendly hotel selection, waste disposal, and sorting garbage at destinations, positively impact TPEBI in tourism (Han, 2015; Hu et al., 2018; Bhati and Pearce, 2016). According to Fenitra et al. (2021), tourists’ intentions to behave sustainably are increasing in tandem with social pressure (Fenitra et al., 2021).

Friends and park visitors are key social groups influencing deviant behaviors, as evidenced by Bhati and Pearce’s (2016) study revealing that damaged tourism sites are more likely to be damaged by other visitors (Bhati and Pearce, 2016). Megeirhi et al. (2020) developed a VBN model to predict cultural heritage support, showing a positive correlation between subjective norms and TPEBI.

Subjective norms significantly influence residents’ attitudes and intentions towards behavior, as confirmed by Duarte Alonso et al. (2015) at a cultural heritage site. Rao et al. (2022) found that pro-environmental behavioral intentions are positively correlated with subjective norms at heritage destinations (Rao et al., 2022). However, Liu et al. (2020) argue that raising subjective norms does not encourage environmentally responsible behavior. Based on the above, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2: Local residents’ subjective norms affect positively their pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

Perceived behavior control and pro-environmental behavioral intention

Perceived behavioral control refers to how individuals perceive the ease or difficulty of a specific environmental activity (Wang et al., 2020), and it significantly influences sustainable behavior and may limit access to heritage sites (Hasan et al., 2021). Perceived behavioral control measures an individual’s ability to anticipate difficulties and control volitional elements (Mugiarti et al., 2022). This judgment is influenced by internal controllability, self-efficacy, and external factors like time, money, teamwork, and necessary skills (Gao et al., 2017).

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) is a significant predictor of intention and behavior, with perceived behavioral control more accurately predicting behavioral intention under both volitional and non-volitional control (Fauzi et al., 2019; Yadav et al., 2019). Perceived difficulty in an activity can be used to measure perceived behavioral control (Ajzen and Madden, 1986; Lee et al., 2021). For instance, it has been demonstrated that intentions to practice environmental conservation are positively and directly impacted by perceived behavioral control (Rao et al., 2022; Arkorful et al., 2023; Qiu et al., 2022). Studies show that perceived behavioral control influences behavioral intention in heritage tourism, particularly in visiting heritage buildings (e.g., Halpenny et al., 2018; Rao et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023; Duarte Alonso et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2022). However, different studies have found varying results on this topic (Pikturnienė and Bäumle, 2016; Tweneboah-Koduah et al., 2019).

Based on the above, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H3: Local residents’ perceived behavioral control affects positively their their pro- environmental behavioral intentions.

Awareness of negative consequences, attitudes and pro-environmental behavioral Intention

Environmental awareness refers to an individual’s awareness of potential harm to their environment, people, animals, habitats, and vegetation when they choose not to engage in environmentally friendly activities (Schwartz, 1977). Problem awareness is crucial for responsible behavior in tourism, and focusing on negative impacts should be a primary focus to encourage responsible tourism practices (Gao et al., 2017). Miller et al. (2010) find that providing tourists with environmental information boosts awareness, while non-climbers are more aware of the consequences of culturally insensitive climbing.

UNESCO World Heritage Site nominations aim to protect global cultural heritage by promoting public support, raising global awareness, and fostering local involvement (Zheng et al., 2014).

The WHS designation is often used as a promotional tool to boost visitor numbers, causing unexpected negative impacts on heritage communities (Yang et al., 2019). Visitors’ increased awareness and appreciation of heritage can lead to various benefits for sustainable tourism development (Wang et al., 2018). Experience is crucial in understanding heritage tourism, as it helps tourists conserve, safeguard, and improve cultural heritage places, leading to increased support for their preservation (Wang et al., 2018). Various studies on environmental behavior reveal strong correlations between attitudes, environmental awareness, and eco-friendly intentions and actions Yadav and Pathak (2017).

Numerous studies in the literature on environmental behavior have highlighted the significant relationships between attitudes toward behavior, environmental awareness, and eco-friendly intentions and actions (Yadav and Pathak, 2017; Meng and Choi, 2016; Chen and Tung, 2014). All of these researchers come to the same conclusion: behavioral attitudes are directly impacted by environmental awareness, and behavioral attitudes in turn drive pro-environmental intentions (Razali et al., 2020). All of these studies have concluded that environmental awareness directly impacts behavioral attitudes, which in turn drive pro-environmental intentions. Han (2015) found that pro-environmental behavioral intention is significantly influenced by awareness of negative consequences and the normative process. Meng and Choi (2016) found that tourists’ awareness of environmental consequences stimulated a positive attitude toward pro-environmental behavior.

In discussing the behavior of residents participating in environmental improvement, Zhou (2018) points out that many individuals have different attitudes toward the environment due to differences in their awareness of negative consequences, and incorporated the attitude of participation and awareness of results into the attitude dimension. Corsini et al. (2018) explore litter prevention behavior and found that awareness of negative consequences plays a crucial role in shaping attitude towards litter prevention.

Based on the above, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H4: Local residents’ awareness of negative consequences positively affects their pro- environmental behavioral intentions.

H5: Local residents’ attitudes moderate significantly the effect of awareness of negative consequences on their pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

Research methodology

Study areas

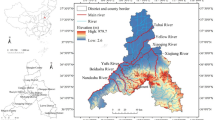

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is located in the far southwest of the continent of Asia, as Fig. 1 shows. It is bordered to the west by the Red Sea, to the east by the Arabian Gulf, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, to the north by Kuwait, Iraq, and Jordan, and to the south by Yemen and the Sultanate of Oman. The Kingdom occupies four-fifths of the Arabian Peninsula with an area estimated at more than 2,250,000 square kilometers; the current population of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is 37,045,930 people, equivalent to 0.46% of the total world population (General Authority for Statistics 2023).

Spatial distribution of archeological sites in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The spatial analysis approach was adopted to achieve the study objectives. ArcGIS Pro was used to prepare the study data, build a geographic database, and analyze it. The study relied on the following steps:

- Collecting archeological data، which consisted of digital spatial data.

- Creating a geographic database using ArcGIS Pro.

- Applying a number of spatial analysis tools، as follows:

Nearest neighbor method

The neighborhood relationship method depends on studying the distribution pattern of phenomena in the spatial area, which helps in understanding the distribution pattern, whether it is a random distribution or a concentrated, regular distribution, which helps in understanding the distribution patterns of phenomena (Abu Ayana, 1987). The following equation was applied in the study of neighborhood relationships:

R = Neighborhood connection.

D = Average distance between points (actual distance). The average is the sum of the distances between points and dividing them by the number of readings (measurements).

N = Number of service location points

A = the size of the search area

The value of the neighborhood correlation coefficient ranges between (0–2.5) where the quantitative significance has a clear and specific meaning between the distribution pattern. If the value is equal to zero, this means the peak of concentration, and if the value is equal to 2.5, this means the peak of separation and dispersion (Dawoud and Mu, 2012).

By applying the neighborhood relationship equation, we found that the distribution pattern of archeological areas takes the divergent pattern, and the value of the neighborhood hall coefficient reached 2.45, which expresses the actual reality of the distribution (see Fig. 1).

Directional distribution

The distribution trend (also called the standard ellipsoid of dispersion) expresses whether the spatial distribution of a phenomenon has a specific direction. Therefore, it is possible to obtain an ellipsoid that expresses the characteristics of a directional distribution, where the center of this ellipsoid coincides with the mean center point, and its major axis measures the value of the direction that most of the phenomenon’s components take (Bivand et al., 2013).

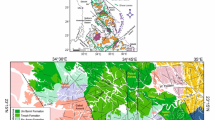

This analysis aims to know the distributional trend of our features by drawing an oval shape that represents the distribution trend of the features, and the center of the oval shape is the average center of the phenomenon (Dawoud and Mu, 2012). By applying the distribution direction analysis of the archeological sites, it was shown from Fig. 2 that the direction is northeast and the direction angle reached 84.05°.

The spatial mean

The spatial mean tool is the counterpart to calculating the arithmetic mean value for non-spatial data, that is, it determines where the location is located that is considered the geographical average of the locations of the individual phenomena under study. This function is one of the functions of central tendency aimed at revealing point patterns, with the aim of finding the average center, which represents the center of gravity for the spatial distribution of points.

The average center is the location that lies in the middle of the geographical locations of the components of the phenomenon under study. The location is calculated as an average of the coordinate values of the locations of the components of the phenomenon under study. This tool works to determine the central geographical location that lies in the middle of a group of points (Sharaf, 2006).

By applying the average center analysis, (Fig. 3), we find that the average center of archeological sites in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is located in the Medina region near the Hail and Qassim regions, meaning that it is located in the middle of the regions of the Kingdom as a result of the spread of the phenomenon in the spatial area.

Before and during the Islamic era, the Arabian Peninsula did not live in isolation from its natural geographical, human, and cultural surroundings. It contributed significantly to building neighboring civilizations, directly or indirectly, thanks to the successive population migrations it witnessed towards the northeast, and it also communicated with other peoples. It has been influenced by trade and the exchange of benefits with it since ancient times (Ezz El-Din and Abda, 2009).

The Arabian Peninsula is considered the key to understanding the spread of ancient man and his civilization in the ancient world by its central location between the continents of the ancient world (Asia, Africa, and Europe) and by its location in East Africa, which is considered, until now, the oldest place of human civilization. In addition, it reflects a series of climatic changes witnessed by all regions of the Kingdom during its previous eras and their effects on the path of man and his civilizations (Hourani, 2013; Magee, 2014).

A group of archeological sites was uncovered by travelers and explorers who visited the Arabian Peninsula, and later those working in the oil fields, some of which date back to the Stone Ages and beyond. Archeological surveys were also conducted after the establishment of the General Administration of Archaeology and Museums of Saudi Arabia, recording several sites in the regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Rice, 2002).

Archeological sites in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia are concentrated in many regions, and the competent authorities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia seek to preserve the historical and heritage richness and register the archeological and heritage sites on the World Heritage List (UNESCO). Four archeological sites have been selected that are distinguished by their historical and heritage value, which made them qualify. To be a source of cultural radiation and a distinguished tourist attraction worldwide (Ezz El-Din and Abda, 2009).

Historic Jeddah

Jeddah, a Red Sea coast city in western Saudi Arabia, is the economic center and top tourism destination. With a population of around 4,697,000, it is a gateway to Mecca and plays a significant role in the import and export of non-oil items (Aloshan et al., 2024; Rashid and Bindajam, 2015). The Historical Old Jeddah, located in the heart of modern-day Jeddah, is easily accessible and is also known as downtown Jeddah (Unesco, 2024; AlawiI et al., 2018). Jeddah, Saudi Arabia’s second-most populous city, is situated in a valley on the eastern bank of the Red Sea, facing the Al Sarawat Mountain range to the west (Boussaa, 2014).

Its historic district, Al-Balad, is rich in both tangible and intangible cultural assets, contributing to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s cultural capital assets and policy for their protection and improvement (Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, 2017; Throsby and Petetskaya, 2021). The Old City of Jeddah, a historic Islamic city with mosques, streets, Harahs, and Souks, became significant in 647 A.D. when Uthman Ibn Affan converted it into a port for Muslims performing the obligatory Hajj to Mecca (Spahic, 2021).

Al-Balad, a city known for its historical buildings and monuments, is home to the Old Jeddah Wall and several important mosques (Unesco, 2024; AlawiI et al., 2018). Its unique architectural and urban legacy is evident in neighboring Red Sea cities like Mossawa’, Sawaken, Alwajeh, and Yanbu (Orbaslı and Woodward, 2009; Bagader, 2014). The World Heritage List recognized Jeddah’s old center in 2012 as a commercial and pilgrimage city, maintaining its architectural characteristics and layout. UNESCO deemed the site universally valuable, citing its long human interaction legacy and connection to the Makkah pilgrimage (Unesco, 2024; Throsby and Petetskaya, 2021).

Mada’in Saleh

Mada’in Salih, located 500 km southeast of Petra, 400 km northwest of Medina, and 22 km north of Al-Ula, is the largest Nabataean site in Saudi Arabia’s north (Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, 2017). It is known for its rock-cut monumental tombs, similar to those in Petra (Saleh, 2013). Mada’in Saleh, located in the Wadi Al-Ula, is a 1621 ha site with numerous tombs, including Qasr Al-Farid, Qasr Al-Bint, Jabal Ithlib, Qasr AS-Sani, Jabal Al-Mahjar, and Khraymat tombs. It was once the capital of Lihyan and was a significant location along the Syrian pilgrimage route during the Islamic era. A railway station was built in the early 20th century (Saleh et al., 2021; Khairy, 2011). Known for its rock-cut tomb façades resembling the non-classical styles at Petra, Mada’in Saleh is the southern outpost of the Nabataeans in contemporary Saudi Arabia (Khairy, 2011).

Mada’in Saleh has a distinctive feature that is not found on other Nabataea sites. There are inscriptions and exact dates on most of the tombs carved in the outcrop cliffs. The social, cultural, and religious values of the Nabataeans are also shown by these inscriptions (Al-Talhi, Dhaifallah, 2000). In 2008 UNESCO proclaimed Mada’in Saleh as the first Saudi Arabian world heritage site because of its rock-cut monumental tombs, with their elaborately ornamented faÁades, of the Nabataean kingdom (Saleh, 141).

Diriyah

Diriyah, located in Saudi Arabia’s desert, is the symbolic birthplace of the Kingdom, serving as the first capital and inspiring numerous leaders throughout its history (Abdelrahman et al., 2023). The Historic Diriyah district holds significant historical significance as the capital city of the first Saudi State, founded in 1727 (Al-Othaymeen, 2013). Historic Diriyah, a significant historical site in Saudi Arabia, has historically shaped the country’s future and remains politically relevant today (Bay et al., 2022). Diriyah, a 1446 village, experienced rapid growth under Mohammed ibn Saud and Ibn Abdulwahhab’s partnership, reaching its peak in 1744 and ending in 1818 (Almogren, 2022).

Najdi’s urban fabric showcases unique planning and architecture, despite the harsh climate of the Arabian desert, showcasing people’s adaptability to hot and dry environments. Diriyah, despite Riyadh’s rise, maintains its cultural identity through ancient buildings and ruins, earning it the Kingdom’s crown gem and investment for future conservation projects (Klingmann, 2022). Diriyah, a significant urban settlement in the Wadi Hanifah Valley of the Najd region, was a significant hub of natural resources and human activity (Almogren, 2022).

Diriyah, a significant urban settlement in Najd’s Wadi Hanifah Valley, has managed to preserve its cultural identity despite Riyadh’s new power center status (Bay et al., 2022). Diriyah, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Najd region, is a significant urban settlement formed through human activities and natural resources fusion (Bay et al., 2022). Diriyah, situated in the Wadi Hanifah Valley, is a distinctive oasis community that showcases Saudi Arabia’s rich historical and cultural heritage. The Al-Diriyah Historic District significantly enhances Riyadh’s municipal identity and branding through humanitarian architecture (Almogren, 2022).

The city values cultural preservation, human dignity, inclusivity, and sustainability, fostering global connections and welcoming individuals from diverse backgrounds. Riyadh’s brand, Al-Diriyah, is reimagined as a symbol of cultural richness, integrating history and progress globally (Hanif and Riza, 2024). Al-Diriyah, a historic quarter in Riyadh, showcases the city’s urban development, cultural heritage, customs, and pride among locals, transcending architectural landmarks (Bay et al., 2022). The At-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah, also known as “Historic Diriyah,” is a UNESCO World Heritage site due to its historical and cultural significance (Almogren, 2022). Historic Diriyah, a World Heritage Site in Saudi Arabia, has seen significant growth since its inclusion in 2010, featuring Najdi architectural style mud-brick structures (Abdelrahman et al., 2023). Conservation and heritage management practices in Historic Diriyah pose challenges and obstacles, necessitating the urgent integration of sustainable development measures for long-term preservation and development (Bay et al., 2022).

Jubbah

Jubbah, located in the Nefud Desert 100 km north of Hail (Murad, 1980), is a significant ancient archeological site in Saudi Arabia, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site (Petraglia, 2015; Al-Hawas, 2003) due to its extensive collection of drawings and topics from different cultural periods [Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, 2017). Recent investigations reveal two ancient human settlement sites in Jubbah, dating back to the Middle Stone Age, located within Umm Sinman Mountain and its southern flank (Bakr, 2024). Umm Sinman Mountain in Jubbah, Hail, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most significant rock art sites globally. Jubbah, the largest rock art site in the Kingdom, is considered an open museum, featuring a large lake with rock shelters for hunters (Bakr, 2024).

Jubbah, a densely populated area with historical inscriptions and rock paintings, was a hub for cross-cultural contact, hosting various social, cultural, and religious events (Khan, 1998). Jubbah’s rock inscription sites, dating over 10,000 years BC, are the fourth Saudi archeological site on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. These inscriptions, executed through deep notching and drilling, represent prehistoric and historical local people’s daily activities, religious practices, and environmental interaction (Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage, 2017).

Sampling and data collection

The research population consisted of locals aged 18 and above from Hail, Medinah, Jeddah, and Riyadh, selected randomly. Five scholars reviewed and made minor changes to the questionnaire before its finalization, ensuring content validity. The survey was created and distributed in Arabic, and a sample of fifty residents participated in a pilot study. All items should be kept, according to the questionnaire’s pilot testing, since their Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were acceptable and above the suggested cut-off.

Participants were invited to fill out a web-based survey from September to November 2024. A number of volunteer academics, students and graduates participated in distributing the survey using social media’s web sites and emails, which keeps a sizable sample of poll respondents who are nationally representative in terms of age, gender, social standing, and educational level.

The study involved randomly selected participants, with a response rate of 85.1%, resulting in 2290 valid survey questionnaires for data analysis after a thorough review. The authors consulted the Deanship of Scientific Research at Hail University before using a structured questionnaire for data collection. The questionnaires were accompanied by a letter outlining the study’s objectives, guidelines, and confidentiality. A total of seven hundred and fifty questionnaires were distributed, and two thousand, three hundred and forty- two local residents answered them, representing an 85.1% response rate. After carefully reviewing the survey, two thousand, two hundred and ninety valid questionnaires were obtained for data analysis.

Research Instruments

In this study, the questionnaire was divided into two sections. The purpose of the first section of the questionnaire was to gather basic socio-demographic information from the respondents, including gender, age, occupation, and education level. The purpose of the second section was to measure the research constructs. Every item for each of the five components was modified based on results from earlier studies on environmental behavior. The final structured questionnaire included 22 items, measured using a five-point Likert scale, and multiple-choice questions about respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics. Validity and reliability were confirmed through pilot testing and factor analysis. The attitude items were adapted from Rao et al. (2022). The subjective norm items were adjusted from Duarte Alonso et al. (2015) to gauge the social pressure on local tourists to act or not to act on preserving heritage. Four items were used to measure this. The planned behavioral control items were adapted from Nyborg (2020) to appraise locals‘ ability to have self-control, including five items. Awareness of negative consequences was adapted from Han (2015). Including five items. The pro-environmental behavioral intention items were adapted from Harland et al. (2007); Wang and Li (2022), five items were used to measure this (see Table 1).

Data analysis

The study utilized the PLS-SEM technique to analyze the constructed model. Since 2013, PLS-SEM has gained popularity, but its full utilization in heritage tourism studies remains in its infancy (Avkiran, 2018). Thus, rather than using the more conventional covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) (Jöreskog et al., 1979), we implemented this relatively recent and widely used variance-based SEM approach of PLS (Sarstedt et al., 2021; Nitzl and Chin, 2017).

The PLS-SEM was utilized to evaluate the measurement and structural models in this investigation. The measurement model (outer model) relates to the relationship between the constructs and their indicators, whereas the structural model refers to the relationship between the latent constructs themselves. The use of PLS-SEM in this work is because it allows for simultaneous analysis of both measurement and structural models, resulting in more accurate calculations. It was used to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the analytical distinctness of constructs from one another, with the expectation that the items would load on their respective constructions (Kline, 2013).

We used PLS-SEM, just like other research. The PLS-SEM is a sophisticated variance-based, non-parametric method for analyzing multivariate data. Additionally, CB-SEM is recommended when theory testing is included, whereas PLS-SEM is thought to be more suitable for exploratory or prediction-oriented research and does not require multivariate normality (Hair et al., 2020). PLS-SEM has been used in numerous social scientific domains over the past 10 years, including strategic management (Hair et al., 2012) and hospitality and tourism (Rasoolimanesh and Ali, 2018), despite still being less popular than the extensively used CB-SEM.

Characteristics of respondents

Table 2 enumerates the sample’s characteristics. Males made up around 78.2 percent of all respondents. The age range of 21 to 30 represents 55.7% of the respondents. Approximately 75% were unmarried. A total of 53.1% of the population had a university school diploma. 47.9% of respondents are students. Moreover, 67.0% of participants stated that they visited heritage sites from 1 to 2 times per year.

Means and standard deviation

Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) for each construct. The mean value of attitude (4.71) indicates strong agreement with their attitude toward protecting heritage sites in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The scores of subjective norms (4.52) suggest that most of the residents agreed with the influence of their reference groups. The mean value of perceived behavioral control (4.48) indicates that most respondents had the sufficient abilities to participate in protecting heritage sites. The mean value of awareness of negative consequences (4.56) indicates how most of the residents in all cities studied are interested in the negative consequences of deteriorating the heritage.

Measurement model test: reliability and validity

The validity and reliability of constructs have been evaluated using a measurement model [167]. The reflective measurement model is evaluated to evaluate the measurement model. The measurement model is evaluated using the following methods: average variance extracted (AVE) for convergent validity, Fornell-Larcker criterion and cross-loadings for discriminant validity, composite reliability for internal consistency, and outer loadings of indicators for individual indicator reliability.

Three methods are used to assess measurement biases (Kock, 2011; Hair et al., 2017). First, if the latent variables’ composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values are greater than 0.70, it is said that their reliability is adequate (Hair et al., 2017). Second, when the average variances extracted (AVE) value of the latent variable is greater than 0.50 and the indicators load significantly on their respective latent variables with item loading of 0.6 or above, the latent variable’s indicators are considered to have convergent validity (Hair et al., 2017). Third, a latent variable satisfies the Fornell–Larcker criterion for discriminant validity when the square root of the AVE of each latent variable is greater than the correlation coefficients of that latent variable with other latent variables (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 4 demonstrates that the minimum values of Cronbach’s alpha (CR) and Cronbach’s r are both greater than the suggested 0.70, indicating that the items within each construct have a satisfactory level of internal consistency. Convergent validity was measured using the extracted average variance (AVE) and factor loadings for the constructs. A construct can be acknowledged as legitimate and approved if its AVE value is greater than 0.50. Considering the importance of these specifications, any latent constructions may be considered adequate or suitable.

The AVE scores and factor loading information demonstrate the great convergent validity of each measuring question. If the value of the cross-loading on the variable in question is the largest and most significant among the cross-loading values for other constructs, then the measuring indicator of the latent variable is valid and acknowledged as a measure of the latent construct. The cross-loading of each item, which represents the latent variable in this paper, is listed in Table 4. There is an attitude indicator in Column 1. It indicates that the ATT1 indicator appears to have a value of 0.755, and the ATT2 indicator appears to have a value of 0.777.

Among the indicators, these two exhibit the largest and most noteworthy loading values compared to the other indicators. This shows that, when compared to other indicators like ATT3 and ATT4, ATT2 and ATT1 are the best indicators for the attitude construct. Using the same technique, we may assess the item validity of the behavioral intention, perceived behavioral control, knowledge of consequences, and subjective norm constructs. Items SN3 and SN1 provide the best measure of the subjective norm construct. The items BC2 showed the largest loading for the perceived behavioral control construct and the knowledge of consequences construct, respectively, when compared to other items. Whereas the largest loadings for the awareness of negative consequences construct are found in items AC4 through AC3. There are adequate loading values for the pro-environmental behavioral intention variable for the BI4–BI5 items, which range from 0.810 to 0.781, and the BI1–BI2-BI3 items, which range from 0.738 to 0.781. These useful items are measures of each latent component in the measuring model depicted in the Fig. 4.

Discriminant validity

The degree to which each latent variable differs from the other components in the model is known as discriminant validity (Murad, 1980). Discriminant validity in PLS-SEM is evaluated using the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT), which is the ratio of the correlation between items measuring the same construct (within-trait) and those assessing distinct constructs (inter-trait). In addition to the fact that none of the associated bias-corrected confidence intervals should contain 1 (Hair et al., 2020), these values must be below 0.85 for conceptually distinct constructions and below 0.90 for conceptually similar constructs (Vinzi et al., 2010). The cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion are examined for discriminant validity. The Fornell-Larcker criterion states that each construct’s square root of its AVE must be greater than its highest correlation with any other construct in the model. As an alternative to AVE, cross-loadings can be used to evaluate the discriminant validity of reflective models. When examining cross-loadings, the outer loading of each indicator on a construct ought to be greater than the sum of its cross-loadings with other constructs (Murad, 1980). Tables 5 and 6 display the HTMT and FLC for each construct, respectively. The off-diagonal cell has no numbers whose values are equal to or greater than 0.85. This indicates that our model satisfies the discriminant validity criteria and employs both methodologies to exhibit good discriminant validity.

Assessment of structural model

The research model’s predictive power and relationships among components are evaluated using path coefficients and the coefficient of determination after establishing its validity and reliability. The multicollinearity test is used to determine whether the independent variables in the regression model are correlated. There should be no multicollinearity in a good regression model. One of the techniques used in this study to determine if multi-collinearity is present or not is the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) method. There is no sign of multicollinearity when the VIF value is greater than 10 and the tolerance is greater than 0.10. According to Table 7’s explanation, the multicollinearity test of all variables reveals that each independent variable’s VIF value is less than 10, which indicates that there is no multi-collinearity symptom or multicollinearity evident (the assumption is fulfilled). All variables are below 10 with a value tolerance of more than 0.1. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) with values between 1.233 and 1.947 fall below the 10.0 threshold. As a result, there was no multicollinearity problem.

The model’s goodness-of-fit and predictive ability were evaluated using R-square. The percentage of the endogenous variables’ variation that the exogenous variables in the model account for is denoted by R². The PLS algorithm approach was also utilized to ascertain the R-square values of the endogenous latent construct. Second, according to Falk and Miller (1992), all latent variable R-square values are more than the permissible level of 0.10 (see Fig. 4). The effect size of each path model effect can be ascertained using the f-square from Cohen (1988). It shows if an exogenous latent variable and an endogenous latent variable have a significant relationship or not. The degree of predictive accuracy is indicated by the corresponding R-square values of 0.313 and 0.465 for the three endogenous latent variables (attitude, pro-environmental behavioral intention). Cohen (1988) states that f-square values greater than 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, in that order, denote mild, medium, and significant impacts. The f-square values in Table 8 show the values of our model’s minor and considerable effects influences.

Model fit

Understanding variable interactions requires a structural equation model (SEM) fit, and the estimated model is compared to a reference model using a variety of fit indices. SRMR, d_ULS, d_G, Chi-Square, and NFI are among the indices used in this study to assess model fit and goodness-of-fit. Using the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), which shows the discrepancy between observed and expected covariances, the saturated and estimated models showed excellent fit.

The difference between the observed and model-implied covariance matrices, as shown by indices d_ULS and d_G, suggests that the estimated model fits the saturated model better. Both observed and model-implied covariances had significant p-values, according to the Chi-Square test, suggesting an inadequate fit. When compared to a null model using the Normed Fit Index (NFI), both the estimated and saturated models fit well (see Table 9).

Path analysis

The weights of sub-constructs and path coefficients were examined for statistical significance using a bootstrapping approach. After evaluating the proposed model’s hypothesized relationships, Table 10 presents the structural model’s results. The original TPB theory constructions are related to one another, according to hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. The fourth hypothesis suggests giving TPB structures an additional component of awareness of negative consequences. The findings indicated that every hypothesis was validated. The results show that pro-environmental behavioral intention was significantly predicted by attitude, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and awareness of consequences. The results also show that pro-environmental conduct is indirectly influenced by awareness of negative consequences through attitude. The coefficient’s value and the direct and indirect correlation between the construct’s influence and other constructs are shown numerically in the Table 10 and Fig. 4. The pro-environmental behavioral intention was significantly positively impacted by perceived behavioral control (t = 10.746 and p = 0.000), subjective norms (t = 8.822 and p = 0.000), attitude (t = 7.526 and p = 0.000), and awareness of negative consequences (t = 6.740 and p = 0.000). With improved pro-environmental behavioral intention, one’s attitude, awareness of negative consequences, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms all rise.

Discussion

This study examines local conservation of heritage sites in Saudi Arabia’s Hail, Madinah, Riyadh, and Jeddah using the planned behavior theory, incorporating awareness of negative consequences to explore pro-environmental behavioral intention in archeological sites, and addressing previous research shortcomings. The model effectively predicts residents’ heritage preservation behaviors, demonstrating its predictive relevance and acceptance of all four assumed relationships, considering the complex nature of heritage preservation issues. Research suggests that individuals are more likely to engage in pro-environmental activities if they perceive benefits or societal pressure, confirming that TPB may explain tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Subjective norms significantly influence pro-environmental behavioral intention to preserve heritage, acting as an influential construct in shaping this intention.

Reference groups can positively influence people to preserve heritage sites, with trustworthy members exerting significant pressure on others and gaining persuasive power. It is widely accepted and consistent with empirical evidence that subjective norms were an important predictor of pro-environmental behavioral intention to keep heritage destinations. This finding is in line with previous works (Rao et al., 2022; Bhati and Pearce, 2016; Duarte Alonso et al., 2015). One reason for our results could be that people think they won’t harm heritage because of the cultural and normative aspects of Saudi society. Thus, it makes sense to propose that the function of subjective norms can vary depending on the cultural environment, and that future research should take into account the impact of various national contexts.

This study shows that local visitors’ willingness for pro-environmental behavioral intention is positively impacted by perceived planned behavioral control. The study’s findings corroborate Ajzen’s (1991) assertion that PBC can directly or indirectly affect behavior through intention. This is supported by previous studies (Halpenny et al., 2018; Rao et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023; Duarte Alonso et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2022), and it indicates that PBC is accessible through a set of control beliefs that may impede or facilitate behavior. More importantly, it reflects that local tourists are more likely to intend to enact pro-environmental activities to keep heritage sites. Perceived behavioral control is the most potent predictor of several pro-environmental behaviors (Lizin et al., 2017). This shows that the majority of respondents in our survey, in the four research areas, are willing to be involved in world heritage conservation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, because they are well-informed about the prospects for heritage protection. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, people might invest enough time and money to actively participate in the conservation of world heritage sites. The government should work harder to encourage citizens to take part in historic conservation initiatives in order to remedy this.

On the other hand, findings indicate that attitude has a positive effect on pro-environmental behavioral intentions to keep heritage destinations. This result is consistent with earlier studies (Halpenny et al., 2018; Wu and Chen, 2018; Duarte Alonso et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2021). The conclusions of Kaiser et al. (1999) and Levine and Strube (2012) that attitude is a powerful predictor of intention to engage in pro-environmental behavior are supported by the results of this study. An individual with a favorable attitude toward the environment is more likely to engage in pro-environmental activities (Lakhan, 2018). According to our study’s interpretation of attitude in the TPB framework, citizens of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia are more inclined to defend the world’s heritage places when they believe that this conduct is significant and advantageous.

The pro-environmental behavioral intentions to keep heritage destinations were found to be highly impacted by environmental awareness of the consequences, according to our study. This indicates that people will have good intentions to keep heritage destinations when they are more environmentally conscious of the effects and consequences of dumping waste, capturing artifacts, drilling and staining that distort the surface of the archeological site, climbing on ruins, and touching antique sculptures and inscriptions. The majority of respondents know enough about the effects of irresponsible behavior at heritage sites on the environment. So they behave in a responsible way to keep world heritage sites while visiting.

Conclusion

By expanding the planned behavior theory, the current study has effectively created a thorough model that takes into consideration the crucial aspects in examining locals’ pro-environmental behavioral intention to preserve heritage sites. The TPB model was further expanded in this study by including awareness of consequences in the setting of domestic heritage tourism. It shown that pro-environmental behavioral intention may be more accurately predicted by the model and its components. All of the hypotheses regarding the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s citizens’ pro-environmental behavioral intention to preserve world heritage sites have been significantly supported by these findings. According to the results, each hypothesis was confirmed. We found that attitude, perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and awareness of consequences were important predictors of pro-environmental behavioral intention. The results also demonstrate that awareness of consequences through attitude indirectly influences pro-environmental behavior. This highlights how important it is to highlight these elements more in advertising campaigns and other promotional tactics meant to preserve Saudi Arabia’s historical sites. This theoretical understanding is crucial for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners in the field of heritage tourism, where supporting and advocating for the preservation of ancient sites should be the goal of all initiatives and tactics.

Implications, limitations and future research

This article presents a study using environmental psychology to enhance understanding of pro-environmental behaviors in heritage tourism, utilizing the theory of planned behavior to examine tourist intentions and fill a gap in current research. The research expands TPB’s applicability to analyze residents’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions in heritage tourism by corroborating endogenous constructs and perceived behavioral control, thereby enhancing its robustness. This study is unique in tourism research, incorporating planned behavior theory and awareness of negative consequences to examine residents’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions towards protecting historical assets in four Saudi Arabian cities. The study on sustainable tourism in Saudi Arabia highlights environmentally conscious behavioral intentions to protect cultural heritage in four cities, expanding on planned behavior theory. The study reveals that incorporating awareness of negative consequences into TPB improves locals’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

This study suggests that fostering residents’ affection for their local area can enhance their sense of responsibility toward preserving cultural heritage resources, thereby ensuring sustainable heritage tourism development. The study highlights the importance of awareness of consequences, attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and perceived behavioral control in persuading residents to protect heritage sites in KSA. The study emphasizes the importance of considering potential drawbacks when preserving heritage assets and the potential negative impacts of unethical behavior, such as not disposing of waste or touching antiques. The study reveals that subjective standards, including in-group norms, significantly influence behavioral intentions to protect archeological sites in the Kingdom, influenced by social pressures from significant companions.

To promote and advocate for the protection of archeological sites, awareness campaigns could be conducted, emphasizing certain subjective norms. The study suggests that pro-environmental behavioral intentions are partly influenced by attitudes, suggesting that prioritizing positive attitudes, encouraging self-education, and consistent government publicity campaigns are crucial for fostering environmental awareness. Society should promote environmental behavior by involving various parties, including the government, businesses, communities, schools, and establishments, through communication campaigns, educational initiatives, and collaboration on public transportation. Heritage management organizations should promote environmentally friendly behavior while visiting heritage sites by improving infrastructure and offering incentives, such as strategically placed public signs and strategically placed garbage cans to discourage littering.

Given the significance of the TPB constructions in elucidating the goal of responsible behavior at legacy sites, official bodies ought to endeavor to strengthen the attitudes of tourists toward the preservation of the environment of cultural destinations. Publicity and education initiatives, for instance, might highlight the special qualities and worth of these websites. People will understand that they can contribute to these destinations’ sustainable growth by adopting pro-environmental actions. This may encourage them to protect the environment at the location. It is possible to set up interactive installations to attract particularly families. People will experience social pressure to participate when family members or close friends are involved, which will motivate them to do the same. In order to encourage people to participate in heritage destination conservation, destination management should broaden their strategies. This could improve visitors’ perceptions of their capacity to act in ways that are environmentally friendly.

This study on tourism sustainability has limitations, including the use of a closed-ended questionnaire and the restriction on respondents’ responses for future investigations. Future research should employ a mixed-methods approach, incorporating experimental data, in-depth interviews, questionnaire surveys, and participatory observation, to gain more insightful results. The data utilized in this study were self-reported. It is suggested that future research use a variety of data collection methods, a wide range of measurements, and data triangulation in order to better accurately assess the constructions.

The study utilized SEM to analyze linear correlations between variables, focusing on asymmetric correlations. Future research should use a combination of models and respondent categories for more representative results. Additionally, incorporating additional moderation variables like income, education, and gender can help anticipate the effects of moderation. The study also used a cross-sectional design, which took a momentary look at how locals behaved at one particular moment. This method restricts the ability to identify causal links between pro-environmental activities and predictions. Longitudinal research would be more appropriate for determining causality and comprehending how behavior evolves over time.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Abdelrahman K, Hazaea SA, Almadani SA (2023) Geological-geotechnical investigations of the historical Diriyah urban zone in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: an integrated approach. Front Earth Sci 11:1202534. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1202534

Abu Ayana F (1987) Introduction to statistical analysis in human geography. Dar Al-Ma’rifah University, Alexandria (In Arabic)

Adam I (2023) Rational and moral antecedents of tourists’ intention to use reusable alternatives to single-use plastics. J Travel Res 62(5):949–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875221105860

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Ajzen I, Madden TJ (1986) Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol 22(5):453–474

AlawiI G, Jamjoum H, Samir H (2018) Enhancing the cultural tourism experience: the case of historical old Jeddah. In Proceedings of Islamic heritage. 177:39–50. 10.2495/IHA180041

Alazaizeh MM, Hallo JC, Backman SJ, Norman WC, Vogel MA (2016) Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan. Tour Manag 57:149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.008

Al-Hawas F (2003) The archaeological and architectural remains of the ancient city of Faid in the province of Hail in Saudi Arabia. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton

Almogren NBA (2022) Mud city: perceptions and misconceptions of Diriyah

Aloshan M, Elghonaimy I, Mesbah E, Gharieb M, Heba KM, Alhumaid MH (2024) Strategies for the preservation of historic areas within existing middle eastern cities: the case of historic Jeddah. Buildings 14(3):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14030717

Al-Othaymeen A (2013) Al-Diriyah origion and development during the era of the first Saudi state. Darah-King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Al-Saad S, Dhabi A, Emirate VA (2014) The conflicts between sustainable tourism and urban development in the Jerash Archaeological Site (Gerasa), Jordan. Doctoral dissertation, Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt

Alsarayreh MN (2019) Heritage tourism of archaeological sites in Jordan: Archaeological site employees’ perspectives. Afr J Hosp Your Leis 8(4):1–19

Al-Talhi Dhaifallah (2000) Mada’in Salih, a Nabataean town in North West Arabia: analysis and interpretation of the excavation 1986–1990. Doctoral Thesis, University of Southampton, School of Humanities, p 346

Andereck KL, Vogt CA (2000) The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J Travel Res 39(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104