Abstract

This paper examines how performance information affects public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in visible public goods (e.g., above-ground roads and parks) and invisible public goods (e.g., below-ground sewage systems) domains. Using a survey experiment with 1171 Chinese public officials, we find that in the visible domain, regardless of performance information, public officials prefer market-oriented indirect policy instruments (e.g., outsourcing) over government-oriented direct policy instruments (e.g., direct government provision), suggesting that avoiding blame is key motivations for understanding their policy preferences. In contrast, performance information plays a limited role in the invisible domain, with public officials prioritizing effectiveness and legitimacy in their choice of instruments. These findings suggest that performance management systems alone may not be sufficient to incentivize proactive governance. Thus, there is a need for balanced accountability mechanisms that encourage the implementation of appropriate instruments in different policy areas to achieve policy goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Performance management systems, as a tool for evaluating and regulating the performance of public officials and public entities, have become a cornerstone of modern governance, aiding in enhancing transparency and accountability (Van Dooren and Van de Walle, 2008, Moynihan, 2008). While the role of performance information in influencing politicians’ agenda setting (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015, Geys and Sørensen, 2018) and public managers’ strategic decisions (Cantarelli, Belle, and Belardinelli, 2020; Mikkelsen et al., 2023) has been extensively explored, there is a notable gap in understanding its effect on public officials’ policy preferences. Given that the disclosure of performance information is expected to ‘enhance policy control of the bureaucracy’ (Moynihan, 2008, 65) in order to improve overall social well-being (Li, 2023), exploring the impact of performance information on policy preferences across different policy domains becomes not just an academic matter, but an urgent issue in relation to constructing a more responsive and accountable bureaucracy.

In results-oriented performance management systems (Moynihan and Pandey, 2010), public officials are tasked with responding to performance challenges by selecting and implementing appropriate policy instruments (Bressers et al., 1998; Howlett, 1991). The arsenal of policy instruments available includes both direct and indirect measures (Song et al., 2017). Direct instruments, also known as “command-and-control”, involve straightforward governmental action to provide services or enforce regulations, often leaving public officials accountable for any failures. Conversely, indirect instruments, or “market-based” measures, utilize third parties to deliver services through incentives, subsidies, or information provision, thereby allowing public officials to shift responsibility for outcomes (Salamon and Elliott, 2002). However, despite the increasing use of performance management systems in the public sector and the critical role of public officials in implementing policy instruments, little is known about whether and how performance information affects public officials’ preferences for policy instruments.

The surprising scarcity of research in this area warrants attention for several reasons. Firstly, the role of performance management systems that are designed to enhance policy control in bureaucracies may not be universal. This is because public officials may strategically select specific policy instruments to respond to performance challenges based on the visibility of the policy goods (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015; Baekgaard et al., 2015). Secondly, policy instruments that are inconsistent with public officials’ preferences may fail. As Weber (1978) notes, public officials may have real authority in the government department because of their information strengths (see also Aghion and Tirole, 1997; Gains and John, 2010). Public officials may resist policy instruments that do not meet their preferences (Song et al., 2017; Kammermann and Angst, 2018). Finally, since different institutional settings usually lead to significant behavioral changes in policy implementers, it is necessary to explore the relationship between performance information and public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in a typical top-down regulatory regime (Chen et al., 2024).

We aim to fill this gap in the literature by examining whether and how performance information can affect public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. We define public officials’ preference for policy instruments as to whether they choose direct or indirect policy instruments (Song et al., 2017). We will discuss this topic in the domain of public goods that are visible or invisible to citizens or government leaders.

This paper will contribute to the existing literature in three distinct ways. First, this study draws on psychological insights into public officials’ policy preferences (Bressers et al., 1998) by integrating blame-avoidance theory and motivated reasoning theory, illustrating how public officials’ preferences for policy instruments may be shaped by the desire to avoid blame or claim credit. Second, we provide experimental evidence that the effect of providing performance information on public officials’ concrete preferences may be not universal. Specifically, this article investigates how performance information on visible (e.g., aboveground urban roads) and invisible (e.g., underground sewage pipes) public goods affects public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. Finally, this article expands our knowledge of performance information effects and public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the form of top-down regulation in China. Previous literature has extensively explored policy instrument preferences in Western democratic settings, often characterized by political fragmentation, power dispersion, and competitive elections (Petersen, 2020; Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018). However, China exhibits a unique blend of top-down authoritarian governance with high levels of administrative decentralization (Zheng, 2007). Overall, this paper promises to enrich our understanding of bureaucratic decision-making behavior in different institutional settings, especially in the form of top-down regulation.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a survey vignette experiment with 1171 public officials who work in city governments in China. In the experiment, public officials were randomly provided with comparative performance information (high-, average-, and low-performance scores) in visible and invisible public goods domains. Public officials were then asked to choose concrete policy instruments to respond to the performance information, as well as their evaluations of the effectiveness and legitimacy features of the selected policy instruments. This approach allows us to investigate the causal effects of performance information on public officials’ preference for policy instruments across policy domains.

Our findings provide novel insights into public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. In the visible public goods domain, the findings suggest that public officials prefer indirect instruments even when they receive high-performance scores, contrary to our hypothesis. At the same time, public officials also preferred indirect means when faced with low-performance scores. These results highlight the importance of blame avoidance motives as a key driver for understanding public officials’ behavior (Ma et al., 2025). Our findings also support the hypothesis that the effect of performance information on policy instrument preferences differs in the domain of visible and invisible public goods (Wang et al., 2021). Specifically, in the visible public goods domain, public officials consistently favor indirect instruments as a strategy to avoid potential blame, regardless of whether performance information is positive or negative. In the invisible domain, performance information has a limited impact on public officials’ preferences, and public officials prioritize effectiveness and legitimacy when choosing policy instruments. These results suggest that performance management systems alone may not be sufficient to motivate officials to take appropriate actions in different policy areas. Public managers need to carefully balance rewards and accountability to encourage proactive behavior and promote effective governance in both visible and invisible policy areas.

Theoretical framework

Public officials’ preferences for policy instruments and performance information effects

The critical challenge in the public sector is to motivate public officials to act in accordance with the policies established by politicians (Simon, 1947). However, scholars have long been worried about the power of public officials, arguing that they may stray from regulation and unduly influence elected politicians (Woodrow and Wilson, 1887; Meier, O’Toole Jr, and O’Toole, 2006; Weber, 1978). This worry is not unreasonable given that public officials may “exploit their information advantage over elected officials” (Moynihan, 2008, 35) to “manipulate politicians into accepting policies that are closer to their preferences” (Baekgaard et al., 2015, 461). When politicians initiate organizational change, it is ultimately the public officials who break down policy goals, recommend specific policy instruments, and oversee their implementation (Blom‐Hansen, Baekgaard, and Serritzlew, 2021; Gains and John, 2010). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the nuanced factors that influence public officials’ decision-making, especially their choices between direct and indirect policy instruments.

Direct policy instruments emphasize the formal authority of the government and involve actions such as regulations or direct provision of services, with public officials directly accountable for outcomes (Howlett, 1991). In contrast, indirect instruments use market mechanisms such as subsidies, taxes, or outsourcing to direct behavior through incentives and allocate responsibility to multiple actors(Song et al., 2017; Lambin et al., 2014). Direct instruments provide control and accountability, while indirect instruments provide flexibility by engaging non-government actors.

Reviewing the literature, a small body of research has examined the factors that affect public officials’ preference for policy instruments (Atkinson and Nigol, 1989; Capano and Lippi, 2017; Linder and Peters, 1989). For instance, Song et al. (2017) show that public service motivation (PSM) has a significant effect on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. Specifically, public officials with higher PSM tend to favor direct instruments, suggesting a preference for more direct governmental intervention. Kammermann and Angst (2018) show that policy core beliefs play a key role in shaping various instrument preferences. For example, free-market beliefs have a greater influence on the preference for specific policy instruments (e.g., regulation), while belief in the urgency of climate change affects both the preference for specific instruments and the preference for a mix of policy instruments. Moreover, Veselý and Petrúšek (2021) suggest that even though public officials show clear patterns of instrument preference like what would be expected by a theoretical typology, they do not tend to prefer specific instruments over others. This suggests that there is no consensus on the causes of public officials’ preferences for certain policy instruments. More importantly, despite the critical role of performance information in public administration (Cantarelli et al., 2023), knowledge of the effect of performance information on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments remains limited.

Moreover, distributive politics research shows that the performance of visible and invisible public goods have different appeals to public officials (Golden and Min, 2013; Mani and Mukand, 2007). Visible public goods are tangible and often easily observed by citizens and managers. For example, urban parks, roads, and bridges are all visible public goods. Moreover, their visibility is not just physical but also pertains to their prominence in policy discourse, such as large-scale policy initiatives, which are often prioritized by citizens, politicians, public managers, and public officials. Conversely, invisible public goods are those assets or policies less apparent, such as sewer systems, or less tangible like implementing new data privacy regulations. Both visible and invisible public goods are essential for societal well-being, but their differences in public awareness and policy emphasis reflect the broader dynamics of social and governmental priority setting.

Therefore, we argue that public officials may be inclined to focus on public goods that are visible to citizens to get votes, or are visible to superior leaders to gain promotion, especially in a political system like China’s, which is characterized by a form of top-down regulation (Patel, 2013; Yi and Woo, 2015). Because the interplay between central oversight and local discretion in China creates a governance environment of mutual checks and balances in which visibility becomes a mechanism for signaling to superiors. A recent study highlights how decentralization in China promotes local officials’ discretion in policy implementation, while local information asymmetries further incentivize them to prioritize visible and measurable outcomes (Chen et al., 2024). Thus, we anticipant that public officials may turn a blind eye to invisible public goods.

Moreover, previous research on policy instrument preferences and performance responsiveness has focused on public officials in non-authoritarian contexts (Acciai and Capano, 2021; Capano and Lippi, 2017). In such settings, electoral accountability and multi-stakeholder participation dominate. However, the Chinese case presents a different institutional logic. Specifically, in China’s authoritarian bureaucracy, political accountability is vertically structured and promotions depend on superior evaluations rather than voter support (Ma et al., 2025). In this scenario, visibility of public goods is a key signaling tool for career advancement rather than for electoral legitimacy. More importantly, decentralization in China does not imply local autonomy, but rather manifests itself as discretionary power under central supervision (Chen et al., 2024). Therefore, this study will contribute to the related literature by interpreting visibility and performance information differently in a centralized political context.

Comparable performance information and public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the visible public goods domain

With the emergence of behavioral public administration, understanding the motivations behind public officials’ decision-making processes has become increasingly nuanced. Central to this is the blame avoidance theory which posits that public officials are inclined to make decisions that protect their reputation (Howlett, 2012, 2014; Lee, 2004; Twight, 1991), especially in the face of potential blame for unpopular actions (Weaver, 1986). Blame avoidance has thus become a key motivation for understanding public officials’ behavior and policy preferences (Baekkeskov and Rubin, 2017, Li et al., 2021). On the flip side of the same coin, claiming credit is often considered part of blame avoidance theory, where public officials can establish reputations by associating themselves with positive outcomes and successful initiatives.

Concurrently, the literature on motivated reasoning suggests that individuals often process information in a way that aligns with their existing goals and beliefs (Stone and Wood, 2018; Baekgaard and Serritzlew, 2016). This theory is particularly evident in political contexts, where politicians and public officials tend to respond to performance information in ways that are consistent with their ideological beliefs (James and Van Ryzin, 2017). In top-down regulation regimes, this means that public officials may favor policy instruments that facilitate claiming credit for sound performance and thus advance reputation and career prospects, or that avoid blame for poor performance (Baekgaard, 2017).

In light of this, the visibility of public goods and their performance information may be a pivotal factor influencing the trade-off between blame avoidance and credit claiming among public officials (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015). Specifically, when public goods are highly visible and performing well, public officials may prefer direct policy instruments that present them with an opportunity to claim credit. This is because, in visible projects, the connection between the public officials’ actions and positive outcomes is direct and clear. For instance, in China’s top-down regulation regime, public officials’ promotions are controlled by their superior leaders; consequently, they often prioritize well-performing visible public goods and services to impress higher authorities, seeking promotion approval. Conversely, indirect policy instruments may dilute the public officials’ association with visible and positive outcomes, making credit claiming less straightforward. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: In the context of positive performance information of visible public goods and services, public officials may prefer direct policy instruments as a strategy for claiming credit, compared to neutral performance information.

Hypothesis 1 emphasizes the tendency of public officials to tie themselves to visible successful outcomes through direct action and provides a nuanced perspective for peering into public officials’ behavior, which is consistent with the principles of blame avoidance theory and motivated reasoning theory. However, a valid criticism may be that direct involvement necessarily increases the risk of future censure if performance declines. This is because direct policy instruments, such as regulation and administrative guidance, are usually associated with reform and reforms of well-being visible public goods and services run the risk of failure (Weaver, 1986; Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015). In contrast, indirect policy instruments such as outsourcing become a risk-averse strategy, as high performance can be maintained by third parties acting according to rules set by the public sector. Moreover, recent studies suggest that political dynamics may further amplify such risk-averse behavior. As Ma et al. (2025) demonstrate, public officials with stronger political connections or embedded in protectionist local networks may be especially motivated to avoid direct association with potentially failing projects. In such cases, indirect instruments serve as both a functional and political shield, allowing public officials to maintain plausible deniability while signaling compliance.

Therefore, we can readily expect that public officials may also prefer indirect policy instruments when receiving positive performance information on visible public goods and services. This aligns with prospect theory, which posits that individuals are risk-averse when facing potential losses but more willing to take risks to secure gains (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). When negative performance information emerges, visible public goods—such as poorly maintained roads or failing public parks—heighten public officials’ exposure to the public and higher authority scrutiny, creating a high-risk environment for blame. In politically sensitive environments, the stakes are even higher, especially for officials whose advancement depends on maintaining political alliances or avoiding damage to elite networks (Ma et al., 2025). Hence, the blame avoidance logic may be particularly strong among politically embedded actors, making indirect instruments a preferred strategy. In such scenarios, public officials are likely to opt for indirect policy instruments to shift responsibility to third parties, reducing personal accountability and minimizing the chance of blame.

However, public officials may sometimes find it difficult (if not impossible) to keep their distance from underperforming public goods and services with high visibility (Dixon et al., 2013; Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015). More particularly, when visible public goods signal low-performance information, it creates a sense of urgency (Kotter 1995) and positions public officials on a burning platform (Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018), where they “are likely to be met with immediate blame” (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015, 553). At this point, choosing indirect instruments may be seen as a risky strategy for inaction (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015). Public officials may thus choose direct instruments (even those that may be less useful) to reverse poor performance by placing themselves “in opposition to the poorly performing program or organization” (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015, 553). Nonetheless, given that blame avoidance is generally considered to be the main motivation for understanding the behavior of public officials, we propose the following hypothesis to test:

Hypothesis 2: In the context of negative performance information in the visible public goods domain, public officials may prefer indirect policy instruments as a strategy for avoiding blame, compared to neutral performance information.

Different responses of public officials to the performance information in the (in)visible public goods domain

Because of the different levels of opportunity to claim credit and risk of blame in the area of visible and invisible public goods and services, public officials may dynamically adjust their policy instrumental strategy accordingly (Baekgaard et al., 2015).

Initially, when policy domains transition from visible public goods to invisible public goods, public officials’ inclinations towards direct or indirect policy instruments may undergo alteration. Specifically, public officials may be less willing to use direct instruments to claim credit for well-performing invisible public goods. In this scenario, public officials’ preferences for policy instruments appear to be minimally influenced by performance information concerning invisible public goods. This can be comprehended readily as invisible public goods are inherently challenging to observe directly, leading to their reduced significance in the subjective perceptions and assessments of citizens, politicians, and superior leaders (Wang, 2016). However, recent research on regulatory behavior in China suggests that this relative inaction may be broken down by campaign-style enforcement mechanisms. As Wang et al. (2021) note, intensive short-term regulatory campaigns, such as centralized environmental inspections, can bring previously neglected areas (including invisible or technical issues) to the forefront of bureaucratic attention. Under such top-down pressure, even normally “invisible” issues may gain temporary visibility and urgency, prompting government officials to demonstrate compliance and responsiveness through direct policy instruments.

Similarly, poorly performing invisible public goods do not put pressure on public officials to take immediate action. Nonetheless, in the context of regulatory activities, these potential problems may be quickly recharacterized as pressing political responsibilities. In this case, public officials may shift from passive to active policy engagement, not because of bottom-up demands, but due to the top-down signaling effect of short-term enforcement mechanisms (Wang et al., 2021). Thus, public officials may have more freedom in choosing which policy instruments to use, because, at this point, they are not driven by motives of claiming credit or avoiding blame.

Additionally, given the complexity of public administration and the heterogeneity of individual characteristics, public officials’ preferences for policy instruments may be unpredictable, and difficult to inscribe their explicit trajectories in the invisible public goods domain. For instance, public officials with high PSMs often act in the public interest (Andersen et al., 2013), and they may be directly involved in the provision of invisible public goods regardless of their performance. Meanwhile, outsourcing advocates among public officials may be inclined to exploit the low-cost advantages of the private sector in response to poorly performing invisible public goods (Boardman et al., 2016). Nonetheless, given the stark contrast between public officials’ incentives to claim credit and avoid blame in the realm of visible public goods, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: Public officials may exhibit a stronger inclination towards direct policy instruments when visible public goods perform well, compared to when invisible public goods do.

Hypothesis 4: Public officials may exhibit a stronger inclination towards indirect policy instruments when visible public goods perform poorly, compared to when invisible public goods do.

This article also tests public officials’ consideration of the effectiveness and legitimacy characteristics of policy instruments when choosing them. In a general sense, effectiveness refers to the ability of a policy instrument to achieve a specific policy goal, while legitimacy means a policy instrument is acceptable to policy makers’ colleagues and policy experts (i.e., internal legitimacy) or by citizens (i.e., external legitimacy). Regarding the basis of recognition and acceptance of legitimacy, this article refers to the institutional structures around the instrument and the congruence of those structures with prevailing norms and values (Schoon, 2022). Reviewing the literature, Hood and Margetts (2007) show a decision maker’s choice of an instrument is influenced by its effectiveness features. Bemelmans-Videc et al. (2011, 8) state that the legitimacy of a policy instrument is crucial for democratic life because it may refer to the degree to which government choices are perceived as “just” and “lawful” in the eyes of the involved actors (see also Capano and Lippi, 2017). More directly, Capano and Lippi (2017) state that effectiveness and legitimacy features are the two primary factors that influence decision-makers’ choice of policy instruments. Therefore, to comprehensively understand the causal effect of providing performance information on policy instrument preferences, we will also examine the considerations of effectiveness and legitimacy features by public officials.

The institutional setting

In this study, we delve into how performance information presentation influences public officials’ policy preferences in China’s political-administrative system. While Western bureaucracies often contend with institutional resistance (e.g., from unions or legislatures) when using performance measurements for fiscal rewards or sanctions (Peters, 2018), China’s approach is characterized by a top-down imposition of performance incentives (Li, 2018). This system limits local discretion in policy instrument selection and implementation due to the central government’s dominant resource capacity and intent on performance improvement. Nevertheless, understanding these constrained choices is vital, as they illuminate the nuances of policy effectiveness in an authoritarian governance context and provide a theoretical foundation for examining similar bureaucratic behaviors in other governance systems. Moreover, the differentiation between visible and invisible public goods becomes particularly pertinent here, considering the promotion tournament (Li and Zhou, 2005) mechanism, where Chinese public officials prioritize projects like bridges, roads, and parks that are highly visible to their superiors for career advancement.

To examine our hypotheses, we need a context that can provide data on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments embedded in positive-, neutral- (as a reference category), and negative-performance information in visible and invisible public goods domains. In addition, an ideal context should include information on the implementation of performance management systems in local governments and the autonomy of public officials to choose different policy instruments in response to performance challenges. One context that meets these criteria is the Urban Infrastructure Development Plan (UIDP), which has been led by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (SCPRC) since 2013. The plan calls for local governments to strengthen urban infrastructure, including urban roads, underground pipeline networks, ecological gardens, underground sewage pipes, and waste treatment (SCPRC, 2013). First, because the main goal of the UIDP was to promote urban infrastructure renewal and, ultimately, economic development, the performance management system became part of the plan to monitor operations and impose accountability (Deslatte, 2020; Fan and Zhang, 2004). In this performance management system, provincial governments released detailed annual performance reports that show how each city government ranks relative to the others.

Second, from the pool of policy instruments that were provided by the central government, public officials in local government can choose specific policy instruments to a certain extent according to the actual situation of their cities. Finally, motivated by political promotion, public officials may adjust their policy instrument strategies for the following year, especially if the ranking of their city is below the expected target (Li and Zhou, 2005). In such a high-stakes context, performance information is expected to have important implications for the careers of public officials. Thus, this context provides an ideal test case because city governments in China increasingly rely on quantitative indicators to assess the performance of urban public goods. Moreover, despite being under the regulatory control of higher levels of government, city government public officials have some discretion in choosing policy instruments to achieve policy goals.

Research design and data collection

Although the UIDP meets our context needs, we need to further consider the challenges that are faced by cross-sectional studies. First, selection bias may result in the inability to isolate the effect of providing performance information, which may be systematically correlated with the personal characteristics of participants that are not included (James, 2011; Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018). For instance, public officials with different cognitive abilities may interpret performance information differently (Petersen 2020). Thus, even when faced with the same public goods domain, public officials may select different policy instruments in reaction to performance indicators. Reverse causality may be another problem because public officials’ preference for concrete policy instruments is likely to be correlated with differences between high- and low-performance scores (Petersen, 2020). For instance, high-performance scores may be a result of public officials’ willingness to implement a selected policy instrument, while low-performance scores may be due to public officials’ resistance to a selected policy instrument. In this case, reverse causality would greatly threaten the internal validity of the cross-sectional design.

To address these challenges, we conducted a survey experiment with public officials working in China’s city governments. Their primary responsibilities encompass a range of activities, notably the construction and maintenance of key municipal infrastructure, including urban roads, bridges, parks, and underground utility tunnels, among others. This survey experiment allows us to isolate the causal effect of performance information because we can manipulate the performance information that is provided to the public officials, and then examine how positive and negative performance information, relative to the neutral performance scores, influences a public official’s preferences for policy instruments.

This survey experiment was conducted on a professional crowdsourcing platform called Credamo, which has been recognized by leading public management journals (Liu et al., 2023). The Credamo platform’s unique internal system validates users through real-name registration, organizational affiliation matching and professional background screening. Only verified professionals with public sector backgrounds are eligible to take the survey, which ensures the validity of the data (Zhang et al., 2024). Screening questions about work experience, job title, departmental affiliation, and years of government service were added to the survey to verify identity. Inconsistent or unqualified responses were excluded. Additionally, we implemented a variety of quality control measures to improve the reliability of the data, including time-to-completion filters, attention checking items, and IP address/location verification to ensure that participants were located in mainland China. Only responses that passed all quality checks were retained in the final dataset. Due to the unavailability of the full sampling frame on Credamo, a precise response rate could not be calculated.

This survey ran for 3 weeks (protocols approved by an institutional ethics review board: CZLS2022041-A), from May 28 to June 17, 2021, with 1,171 municipal officials from 221 cities in China who participated via the Credamo app on their smartphones.

Based on the analysis results of G*Power 3.1 (at least 105 samples in each group when the effect size is 0.5, the alpha value is 0.05 and the power value is 0.95), our sample size (at least 190 samples in each group) is large enough to have sufficient statistical power to test the effect of providing performance information on a public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. Furthermore, we use a filter question in the questionnaire by asking subjects to select a specific answer, to exclude inattentive participants or bots.

Before the formal survey, we conducted two pilot surveys in the summer of 2020 and spring of 2021. The purpose of these pilot surveys is twofold: (1) the first pilot survey involved 104 participants and was used to explore the status of public officials’ preferences for policy instruments with a single question—“What do you think is the most effective policy instrument for the provision of urban infrastructure?”; and (2) the second pilot survey involved 202 participants and used a fictitious example to test whether randomizing performances would support our hypotheses. Based on these pilot surveys, we selected two public goods domains from the UIDP for manipulation: urban roads and underground sewage pipes. We selected these areas for two reasons: First, the work associated with these two public goods (also the simulated tasks in the tour experiment) is highly realistic for the Chinese public officials who need to deal with them in their daily work; and second, these services can be distinguished as visible (urban roads) and invisible (urban underground sewage pipes) public goods for our experimental manipulation.

Experimental design and treatments

Our survey experiment consists of two randomization processes: First, public officials are randomly assigned to one of the highest, middle (neutral), or lowest performance scores for the public goods; and second, the type of public goods (visible/invisible) that public officials are exposed to is also random. Drawing on Olsen (2015), this study did not include a control group without performance information because we were mainly concerned with the asymmetrical effects of providing positive and negative performance information on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments, rather than the effects without any performance information. Moreover, performance information is an integrated element of the decision-making process. Asking public officials to choose policy instruments without any performance information would be considered too far from reality. Thus, we used the experimental group with middle-performance scores as the reference category in the analysis.

To enhance internal validity, we treated the experimental vignettes as follows. First, we provided all participants with a uniform description of policy instruments, performance information, and the relationship between the two. This allows participants to have a common understanding of the key concepts in the experimental vignettes. Second, we informed participants that the performance ranking was relative to “similar cities (in terms of size, population, economy, etc.)” to make them aware that the ranking was comparable and reasonable. In addition, given the successful manipulation of experimental material in the pilot survey experiment and concerns that manipulation checks may “amplify, undo, or interact with the effects of a manipulation” (Hauser et al., 2018, 1), we did not use any manipulation checks in this study. In total, this experimental design provides us with six experimental groups, as shown in the experimental flow in Fig. 1.

Dependent variable: policy instrument preferences

To measure the public officials’ preferences for policy instruments, the respondents were asked to imagine that he/she was the manager of the city municipality and to answer the question “What do you think are the two most effective policy instruments to improve the performance targets of N-city in 2021?”. The participants were asked to select the two most appropriate options from among those classified as direct and indirect policy instruments. Based on Song et al.’s (2017) classification, we removed two policy instruments that were not explicitly listed in the UIDP—Voucher and Financial Support. In keeping with Song et al.’s (2017) measure of preference for policy instruments, we also included the “other” option in the questionnaire. The respondents were not allowed to continue answering questions that followed until they had selected any two options. During the survey, all the options are presented randomly to avoid threatening the validity of these results by presenting the options in a fixed order. Table 1 shows the classification of the policy instruments.

It is worth noting that the distinction between direct and indirect policy instruments is admittedly somewhat arbitrary (Song et al., 2017). Citing Song et al.’s (2017) example, “Information provision” involves both “Labeling” (an indirect instrument) and “Public information” (a direct instrument). Without making the distinction, we could not know whether respondents’ interpretations of these policy instruments are direct or indirect. To highlight the distinction between direct and indirect instruments, we initially used a more easily distinguishable name. For example, we use the term “Subsidy” instead of “Financial support” to indicate the indirect nature of the policy instrument. Furthermore, we provide a simple description of the policy instrument in the options of the questionnaire. For instance, the short description of “Outsourcing” as “Utilizing market mechanisms to contract out the provision of infrastructure to third parties” points to an indirect instrument. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that not all instruments may be perceived as equally distinct or equally important by respondents. As such, responses reflect perceived appropriateness rather than assumed mutual exclusivity or equivalence. We point this out in the limitation section of this paper.

Moreover, to test whether the experiment participants could identify the different policy instruments into two different categories (direct and indirect), we recruited 60 grassroots public officials with some experience in urban infrastructure development to conduct two different pilot surveys. 60 respondents were divided into two groups of 30 each, and they answered different questions. Specifically, Pilot Survey 1: 30 of the respondents were presented with ten policy instruments divided into two groups and asked, “How do you think the two groups of policy instruments could be categorized in a more comprehensive and relevant way?” Respondents were asked to rank 1 “Regulatory instruments (regulatory instruments such as laws, standards, licensing, etc.) versus economic instruments (market-based instruments such as taxes, subsidies, etc.)”, 2 “Direct instruments (instruments that directly influence the behavior of target groups such as laws, regulations, etc.) versus indirect instruments (instruments that indirectly influence the behavior of target groups such as information campaigns, outsourcing, taxes, etc.)”, 3 “Command and control tools (mandatory tools such as laws and regulations) versus voluntary tools (tools such as agreements, partnerships, and self-regulation)”, and 4 “Traditional tools (tools that have been used for a long time and are widely familiar) versus innovative tools (relatively new, experimental, untested tools)”. Pilot Survey 2: A further 30 respondents were presented with each of the ten policy instruments in the same way as the policy instrument options in the formal survey experiment, including a brief description of the policy instrument (see Appendix for more details) and were asked to rate them between options 1 “Direct Policy Instrument” and 2 “Indirect Policy Instrument”. The results of the two pilot surveys show that almost over 90 percent of respondents accurately identified the classification of direct and indirect policy instruments, as shown in Table 2.

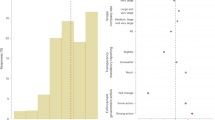

In constructing the dependent variable, we excluded the “other” option, which potentially implied doing nothing, because none of the respondents had selected it. Hence, we construct a 1–3 index to measure the public officials’ preferences for policy instruments: if a respondent chooses two direct policy instruments, then a value of 1 is assigned; if a respondent chooses one direct and one indirect policy instrument, then a value of 2 is assigned; and if a respondent chooses two indirect policy instruments, then a value of 3 is assigned. Figure 2 shows the percentage of observations of direct and indirect policy instruments.

Two questions are included to examine the public officials’ evaluations of the effectiveness and legitimacy of the chosen policy instruments. After measuring the preference for policy instruments, the respondents are asked to what extent they agree with the statements that “I chose these two policy instruments because they are effective and more likely to achieve specific policy ends” (effectiveness) and “I chose these two policy instruments because they are legitimate and more likely to be recognized and accepted by colleagues, policy experts, or the public” (legitimacy). The respondents are asked to access each statement on a Likert five-point scale, ranging from 1 “completely disagree”, 2 “disagree”, 3 “neither disagree nor agree”, 4 “agree”, and 5 “completely agree”.

The demographic characteristics of our sample are shown in Table A1 in the Appendix. As the Chinese government does not disclose the overall data of public officials, we did not compare our sample to Chinese public officials.

Empirical findings

Balance test

Table 3 reports these results from the balance test, showing that there are no systematic differences between the groups receiving each treatment. Notably, gender and PSM are slightly higher in the negative performance group for both all and visible public goods, but this did not impact these results according to subsequent simple effect analyses.

Main effect test

Table 4 shows that for policy instrument preferences, the main effect of performance information (positive, neutral, and negative) is not significant (p = 0.70), while the main effect of the type of public goods (visible and invisible) is significant (p < 0.05). Additionally, there is a significant interaction between performance information and the type of public goods at the 0.05 level of significance (p < 0.05). Therefore, it cannot be simply assumed that the type of public goods has a primary effect on policy instrument preferences. Instead, interaction effect tests are required to analyze the impact of public goods type on policy instrument preferences at different levels of performance information.

Interaction effect test

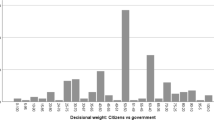

Figure 3 shows the findings for the three treatment groups (positive, neutral, and negative performance information) in the context of visible public goods. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, these results indicate that when public officials are provided with high-performance scores for visible public goods, they are more likely to choose indirect instruments than direct ones, compared to when provided with neutral performance scores (see Model 1 in Table 5, Cohen’s d = 0.246). This suggests that rather than leveraging direct instruments to claim credit for positive outcomes, public officials may prefer indirect instruments to preserve the high-performance status quo and minimize the risk of future blame. These findings align with blame avoidance theory and the notion that officials are inherently risk-averse. While direct involvement could offer opportunities to claim credit, it also exposes officials to potential blame if performance deteriorates later (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015). This challenges the assumption in Hypothesis 1 and highlights the complex interplay between blame avoidance and credit claiming in shaping policy preferences.

Public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the visible public goods domain by performance group (high, average, and low), PI performance information. Note: The asterisks on the straight line show significant differences between treatment effects (p-Values from the t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Confidence intervals for the individual effects are at 95%.

For the low-performance group in the context of visible public goods, we find a statistically significant positive effect on the public officials’ preferences for policy instruments when compared to the neutral performance group (see Fig. 3 and Model 1 in Table 5; p = 0.046, Cohen’s d = 0.197). This suggests that when visible public goods are poorly performing, public officials are more inclined to choose indirect instruments to minimize the risk of future blame, supporting Hypothesis 2. Hence, while previous studies conducted in democratic systems demonstrated that low-performance information sends an urgent signal to policy actors, who are likely to apply direct instruments to reverse low performance (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015; Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018), public officials in China (at least in our case) have a contrary response to low performance in a highly salient policy domain. This suggests that, in visible policy areas, public officials appear to be more wary of underperforming public goods, and they tend to use indirect instruments to shift responsibility.

Furthermore, Table 5 confirms these results using ordered logistic regression. The coefficients show that, regardless of the inclusion of control variables such as gender, age, level of education, major, work pressure, job satisfaction, and PSM, providing positive performance information and negative performance information has a positive effect on the public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the domain of visible public goods. The OR values indicate that providing positive performance information about visible public goods makes public officials 1.6 times (i.e., 60 percent higher) more likely to choose indirect instruments when compared to neutral performance information about visible public goods. Meanwhile, providing negative performance information about visible public goods makes public officials 1.5 times (i.e., 50 percent higher) more likely to choose indirect instruments when compared to neutral performance information about visible public goods. Thus, although our effect size is about 0.2, which indicates a small effect, it is certainly not trivial.

We also examined the effect of providing performance information on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the domain of invisible public goods. Compared to the neutral performance information subgroup, it exhibits no statistically significant difference between public officials’ preferences for direct and indirect policy instruments, as Appendix Table A3 and Figure A1 show.

These results in Fig. 4 reveal significant differences in public officials’ preferences for policy instruments across visible and invisible public goods. Specifically, public officials show a stronger preference for indirect instruments when receiving both positive and negative performance information about visible public goods, compared to invisible ones. Hypothesis 3 predicted that public officials would favor direct instruments to claim credit for positive performance in visible public goods. However, the findings indicate that even with good performance, public officials still prioritize indirect instruments. This suggests that their focus may remain on avoiding the risks of future performance decline, even when managing successful visible public goods. However, these results align with Hypothesis 4, which proposed that public officials would prefer indirect instruments in response to poor performance in visible public goods. By outsourcing responsibilities, public officials can distance themselves from potential criticism while maintaining service delivery through third parties. In the neutral performance information subgroup, public officials show no statistically significant preference for direct or indirect policy instruments in both visible and invisible public goods domains.

Public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the (in)visible public goods domain by performance group (positive, neutral, and negative), PI performance information. Note: The asterisks on the straight line show significant differences between treatment effects of visible and invisible public goods (p values from the t-test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). The estimated models that are used in this figure are presented in the Appendix in Table A3.

To explore whether policy instruments are chosen for their other features, we further examine the public officials’ evaluations of the effectiveness and legitimacy of their chosen policy instruments. Additional analysis shows that when provided with positive or negative performance information in the visible public goods domain, the effectiveness and legitimacy features of policy instruments are not the factors influencing public officials’ choice (Model 1 and Model 2 in Appendix Table A5). Moreover, additional analysis suggests that when provided with performance information in the invisible public goods domain, public officials choose policy instruments based on their evaluations of their effectiveness and legitimacy features. Specifically, public officials give a higher evaluation of the effectiveness of the chosen instruments when invisible public goods perform poorly (Model 3 in Appendix Table A5), while they give a higher evaluation of the legitimacy of the chosen instruments when invisible public goods perform well (Model 4 in Appendix Table A5). Overall, these results show that the effectiveness and legitimacy features of policy instruments influence public officials’ preferences for policy instruments only in the domain of invisible public goods.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, while we differentiate between visible and invisible public goods to explore public officials’ policy preferences, the distinction may be difficult to apply consistently in real-world practice, where performance information is often aggregated at the departmental level. This challenge reflects a broader limitation of experimental designs that simplify complex administrative realities. Second, although our stylized performance information helps isolate causal effects, it does not fully reflect the informational complexity public officials face in real settings (Mikkelsen et al., 2021). In practice, public officials often encounter multiple, conflicting, or evolving performance signals. Future studies could examine how officials process and prioritize diverse performance information over time. Third, our sample was not stratified by city size or region. While the sample is geographically diverse, its representativeness is limited. We addressed this through identity screening and quality control measures, but future research could improve generalizability through stratified or quota-based sampling strategies and integration with administrative data. Fourth, our measure of policy instrument preference was based on selecting two instruments from a predetermined list, categorized into direct and indirect types. Whilst this categorization is based on existing literature (Howlett, 1991; Song et al., 2017), we recognize that some instruments may not be entirely mutually exclusive, or may not be seen as equally important by all respondents. This may introduce measurement bias. Future research could explore weighted or ranked choice designs to better capture the rationale behind preferences. Finally, this study provides a cross-sectional snapshot of instrument preferences. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs and explore how officials sequence or combine instruments across time and policy domains.

Discussion and conclusion

Previous research has shown that providing performance information affects the perceptions, attitudes, and intended behaviors of politicians, public managers, and citizens (Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018; Nielsen and Moynihan, 2017; Petersen, 2020; Petersen et al., 2019; Olsen, 2015; James and Van Ryzin, 2017). However, knowledge about the effect of performance information on public officials’ policy preferences is limited. In this paper, we use a survey experiment to examine whether and how providing performance information in visible and invisible public goods domains affects public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. Based on our findings, this study extends the literature on authoritarian governance by examining how bureaucratic actors respond to institutionalized performance signals in authoritarian settings. Specifically, our findings shed new light on the existing literature in three important ways.

First, our findings suggest that positive performance information in the area of visible public goods leads public officials to favor indirect policy instruments over direct policy instruments. This result contradicts Hypothesis 1, which expects public officials to prefer direct instruments to claim credit for positive outcomes. Instead, the findings suggest that avoiding blame is more motivating for public officials than claiming credit, even when visible public goods are performing well. This finding challenges blame avoidance theory. While the credit-evoking component of blame avoidance theory suggests that officials should welcome visibility in success stories (Weaver, 1986; Hong et al., 2020), our results suggest that even positive outcomes discourage direct participation. One possible explanation is that because promotions in authoritarian settings are determined by superior evaluations rather than elections, the rewards of inviting credit may be less direct or less certain than the potential costs of failure. This suggests a need to rethink the conditions under which the logic of credit-claiming operates, particularly in systems where upward accountability dominates and reputational risk is asymmetric. Thus, even when positive results provide opportunities to enhance their status, public officials may strategically distance themselves from direct responsibility to avoid future uncertainty. The findings further suggest that public officials’ preferences for indirect instruments are not motivated by considerations of effectiveness or legitimacy, but rather by a desire to maintain a high-performing status quo without direct intervention. Politicians and public managers should be mindful of this tendency as it may discourage proactive governance and lead to missed opportunities for innovation or improvement through direct engagement (Weaver, 1986; Hong, 2020).

Second, with regard to the impact of providing information about the negative performance of visible public goods, the findings provide new insights. Our findings suggest that public officials prefer indirect policy instruments in such situations. These results support Hypothesis 2, suggesting that avoiding blame remains the main motivation for public officials’ choice of policy instruments, even in contexts where immediate corrective action is usually required. According to Prospect Theory, public officials should exhibit risk-averse tendencies when faced with negative performance information. The choice of indirect policy instruments allows them to transfer responsibility to a third party, thereby reducing personal accountability (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Weaver, 1986). While some research in decentralized political systems suggests that poor performance creates a sense of urgency that pushes public officials to use direct instruments (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015), our findings suggest a different dynamic in China’s centralized political system. Public officials may be reluctant to intervene directly in underperforming visible public goods, possibly because they fear stigmatization if the intervention fails. This dynamic coincides with layers of accountability in authoritarian bureaucracies that tend to encourage passive avoidance rather than positive correction (Mertha, 2009).

It should be noted that, although our experiment isolates the effect of performance information on policy instrument preferences, a potential limitation to consider is reverse causality. That is, public officials’ prior preferences may affect the actual performance of public goods over time. This concern is not unreasonable, as real-world governance often involves complex dynamics between instrument choice and performance. For example, officials who prefer indirect tools may manage outsourcing arrangements more skillfully, leading to better observed outcomes in projects that employ such tools. Conversely, officials who favor direct control may be more willing to take initiatives in areas where there are already signs of improvement, thereby consolidating performance gains. Thus, future research could further disaggregate these interactions using panel data or longitudinal field designs to capture the changing interplay between policy preferences and performance outcomes.

Moreover, further analysis suggests that public officials’ preferences for indirect instruments are not based on judgments about the effectiveness or legitimacy of the instruments (Capano and Lippi, 2017). Instead, the findings suggest that their main purpose in choosing indirect instruments might be to distance themselves from bad outcomes to avoid blame. While this strategy helps public officials avoid blame, it also undermines the core objective of performance management systems, which is to incentivize public officials to take action and improve through the publication of performance data (Mikkelsen et al., 2021). In practice, governments need to revisit the balance between rewards and accountability to ensure that public officials are motivated to actively engage in responding to poor performance without undue fear of being blamed, thereby promoting more active and accountable governance in visible policy domains.

The third contribution of this paper is to reveal differences in public officials’ preferences for policy instruments in the visible and invisible public goods domain. Currently, a large body of research on the impact of performance information and the behavior of public officials focuses on the visible (or salient) policy domain (Nielsen and Baekgaard, 2015; Nielsen and Jacobsen, 2018; Petersen, 2020). However, our findings suggest that public management research needs to incorporate the invisible policy domain. This paper shows that the disclosure of performance information in the visible and invisible public goods domains triggers different patterns in public officials’ preferences for direct and indirect policy instruments. Specifically, public officials are more inclined to choose indirect policy instruments in the visible policy domain, regardless of whether positive or negative performance information is provided. This suggests that in the visible policy domain, even for well-performing projects, public officials still prioritize indirect instruments to hedge against the risk of future performance decline and thus avoid possible liability. This is a departure from the behavioral patterns assumed by traditional theory and shows that public officials’ decisions in the visible domain are strongly driven by the motive to avoid blame.

In contrast, in the invisible policy domains, performance information has little or no effect on public officials’ preferences for policy instruments. This suggests that public officials exercise greater discretion in these domains, choosing policy instruments primarily on the basis of their effectiveness and legitimacy characteristics. Further analyses show that when invisible public goods perform poorly, public officials are more inclined to choose policy instruments they perceive to be effective, while when invisible public goods perform well, public officials place more emphasis on the legitimacy of the instruments (Capano and Lippi, 2017). This finding suggests that performance management systems alone may not be sufficient to motivate public officials to take positive action in different policy domains. In visible policy domains, the motivation to avoid responsibility may inhibit public officials’ positive interventions, while in invisible policy domains, public officials rely more on their subjective judgment of policy instruments than on external performance information. Therefore, governments should carefully consider how to optimize fault tolerance and immunity mechanisms to incentivize public officials to prioritize the effectiveness and legitimacy of policy instruments when choosing them (Yan et al., 2021), so as to achieve performance improvements in both visible and invisible public goods domains. This may include the use of process-based assessments, rewarding responsible risk-taking behavior and promoting accountability systems that focus on learning rather than punishment (Li et al., 2023). These measures can help to reduce concerns about liability and encourage more proactive behavior in visible areas.

Importantly, these findings also echo a broader discussion about how accountability works in authoritarian regimes. In Western decentralized polities, public officials are usually held accountable through elections and media scrutiny (Lau and Redlawsk, 2006; Woodhouse et al., 2022). In China, however, accountability is mainly enforced through bureaucratic oversight and top-down assessments. That is, Chinese public officials’ accountability avoidance behavior tends to be upwardly oriented and designed to satisfy the needs of their superiors rather than their constituents. Our findings suggest that public officials may prefer indirect tools even in performance-oriented administrative settings. This is because indirect tools offer protection from liability rather than being more effective. Thus, this risk-averse behavior implies to some extent that career advancement may depend on avoiding politically costly mistakes (Liu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). In sum, our finding contributes to understanding how authoritarian accountability mechanisms shape grassroots bureaucratic behavior.

Collectively, our findings suggest that the impact of performance information on public officials’ policy instrument preferences is context-dependent and varies with the visibility of public goods. This highlights that public officials’ decisions are not entirely driven by performance data; they also need to manage blame and risk. To promote active governance, governments need to seek to reduce public officials’ concerns about liability and encourage them to move from behind the curtain to the front of the stage so that they can implement policies responsibly. This includes creating an environment that empowers public officials to exercise discretion effectively and facilitates the selection of policy instruments that are best suited to addressing underperformance or sustaining positive outcomes—regardless of whether the policy area is visible or invisible to citizens, politicians, and leaders.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Acciai C, Capano G (2021) Policy instruments at work: a meta‐analysis of their applications. Public Adm 99(1):118–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12673

Aghion P, Tirole J (1997) Formal and real authority in organizations. J Polit Econ 105(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1086/262063

Andersen LB, Jørgensen TB, Kjeldsen AM, Pedersen LH, Vrangbæk K (2013) Public values and public service motivation: conceptual and empirical relationships. Am Rev Public Adm 43(3):292–311

Atkinson MM, Nigol RA (1989) Selecting policy instruments—neo-institutional and rational choice interpretations of automobile insurance in Ontario. Can J Polit Sci/Rev Can Sci Polit 22(1):107–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/s000842390000086x

Baekgaard M (2017) Prospect theory and public service outcomes: examining risk preferences in relation to public sector reforms. Public Adm 95(4):927–942

Baekgaard M, Blom‐Hansen J, Serritzlew S (2015) When politics matters: the impact of politicians’ and bureaucrats’ preferences on salient and nonsalient policy areas. Governance 28(4):459–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12104

Baekgaard M, Serritzlew S (2016) Interpreting performance information: motivated reasoning or unbiased comprehension. Public Adm Rev 76(1):73–82

Baekkeskov E, Rubin O (2017) Information dilemmas and blame-avoidance strategies: from secrecy to lightning rods in chinese health crises. Gov - Int J Policy Adm Inst 30(3):425–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12244

Bemelmans-Videc ML, Rist RC, Vedung EO (eds) (2011) Carrots, sticks, and sermons: policy instruments and their evaluation. Transaction Publishers

Blom‐Hansen J, Baekgaard M, Serritzlew S (2021) How bureaucrats shape political decisions: the role of policy information. Public Adm 99(4):658–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12709

Boardman AE, Vining AR, Weimer DL (2016) The long-run effects of privatization on productivity: evidence from Canada. J Policy Model 38(6):1001–1017

Bressers TAH, O’Toole JL (1998) The selection of policy instruments: a network-based perspective. J Public Policy 18(3):213–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X98000117

Cantarelli P, Belle N, Belardinelli P (2020) Behavioral public HR: experimental evidence on cognitive biases and debiasing interventions. Rev Public Pers Adm 40(1):56–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371x18778090

Cantarelli P, Belle N, Hall JL (2023) Information use in public administration and policy decision making: a research synthesis. Public Adm Rev 83(6):1667–1686

Capano G, Lippi A (2017) How policy instruments are chosen: patterns of decision makers’ choices. Policy Sci 50(2):269–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9267-8

Chen S, Yuan L, Wang W, Gong B (2025) Decentralization, local information, and effort substitution: evidence from a subnational decentralization reform in China. Governance 38(2):e12884

Deslatte A (2020) Positivity and negativity dominance in citizen assessments of intergovernmental sustainability performance. J Public Adm Res Theory 30(4):563–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa004

Dixon R, Christiane Arndt M, Mullers J, Vakkuri K, Engblom‐Pelkkala CH (2013) A lever for improvement or a magnet for blame? Press and political responses to international educational rankings in four EU countries. Public Adm 91(2):484–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12013

Fan SG, Zhang XB (2004) Infrastructure and regional economic development in rural China. China Econ Rev 15(2):203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2004.03.001

Gains F, John P (2010) What do bureaucrats like doing? Bureaucratic preferences in response to institutional reform. Public Adm Rev 70(3):455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02159.x

Geys B, Sørensen RJ (2018) Never change a winning policy? Public sector performance and politicians’ preferences for reforms. Public Adm Rev 78(2):206–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12824

Golden M, Min B (2013) Distributive politics around the world. Annu Rev Polit Sci 16:73–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052209-121553

Hauser DJ, Ellsworth PC, Gonzalez R (2018) Are manipulation checks necessary? Front Psychol 9:998

Hong S (2020) Performance management meets red tape: bounded rationality, negativity bias, and resource dependence. Public Adm Rev 80(6):932–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13213

Hong S, Kim SH, Son J (2020) Bounded rationality, blame avoidance, and political accountability: how performance information influences management quality. Public Manag Rev 22(8):1240–1263

Hood CC, Margetts HZ (2007) The tools of government in the digital age. Macmillan International Higher Education

Howlett M (1991) Policy instruments, policy styles, and policy implementation—national approaches to theories of instrument choice. Policy Stud J 19(2):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1991.tb01878.x

Howlett M (2012) The lessons of failure: learning and blame avoidance in public policy-making. Int Polit Sci Rev 33(5):539–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512112453603

Howlett M (2014) Why are policy innovations rare and so often negative? Blame avoidance and problem denial in climate change policy-making. Glob Environ Chang 29:395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.12.009

James O (2011) Performance measures and democracy: information effects on citizens in field and laboratory experiments. J Public Adm Res Theory 21(3):399–418. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq057

James O, Van Ryzin GG (2017) Motivated reasoning about public performance: an experimental study of how citizens judge the affordable care act. J Public Adm Res Theory 27(1):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw049

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory—analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Kammermann L, Angst M (2018) The effect of beliefs on policy instrument preferences: the case of Swiss renewable energy policy(sic)(sic)(sic)palabras clave. Policy Stud J 49:757–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12393

Kotter JP (1995) Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev 35(3):42–48. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2009.5235501

Lambin, Eric F, Meyfroidt P, Rueda X, Blackman A, Börner J, Cerutti PO, Dietsch T, Jungmann L, Lamarque P, Lister J (2014) Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land use governance in tropical regions. Glob Environ change 28:129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.007

Lau RR, Redlawsk DP (2006) How voters decide: information processing in election campaigns. Cambridge University Press

Lee BK (2004) Audience-oriented approach to crisis communication: a study of Hong Kong consumers’ evaluation of an organizational crisis. Commun Res 31(5):600–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650204267936

Li B (2018) Top-down place-based competition and award: local government incentives for non-GDP improvement in China. J Chin Gov 3(4):397–418

Li HB, Zhou LA (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89(9-10):1743–1762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009

Li J, Ni X, Wang R (2021) Blame avoidance in China’s cadre responsibility system. China Q 247:681–702

Li Q, Haodan Sun Y, Tao Y, Ye KZ (2023) The fault-tolerant and error-correction mechanism and capital allocation efficiency of state-owned Enterprises in China. Pac Basin Financ J 80:102075

Li Z (2023) Bureaucratic response to performance information: how mandatory information disclosure affects environmental inspections. Public Adm Rev 83(4):750–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13636

Linder SH, Peters BG (1989) Instruments of government: Perceptions and contexts. J Public Policy 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00007960

Liu B, Lin S, He S, Zhang J (2024) Encourage or impede? The relationship between trust in government and coproduction. Public Manag Rev 26(12):3501–3528

Liu B, Qin Z, Zhang J (2022) The effect of psychological bias on public officials’ attitudes towards the implementation of policy instruments: Evidence from survey experiments. J Public Policy 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X22000319

Ma L, Wang H, Chen S (2025) Local protectionism and national oversight: political connection and the enforcement of environmental regulation in China. J Chin Gov 10(1):106–127

Mani A, Mukand S (2007) Democracy, visibility and public good provision. J Dev Econ 83(2):506–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.06.008

Meier KJ, O'Toole LJ (2006) Bureaucracy in a democratic state: a governance perspective. JHU Press

Mertha A (2009) Fragmented authoritarianism 2.0”: political pluralization in the Chinese policy process. China Q 200:995–1012

Mikkelsen MF, Petersen NB, Bjørnholt B (2022) Broadcasting good news and learning from bad news: experimental evidence on public managers’ performance information use. Public Adm 100(3):759–777

Mikkelsen MF, Pedersen MJ, Petersen NBG (2023) To act or not to act? How client progression affects purposeful performance information use at the frontlines. J Public Adm Res Theory 33(2):296–312

Moynihan DP, Pandey SK (2010) The big question for performance management: why do managers use performance information? J Public Adm Res Theory 20(4):849–866. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq004

Moynihan DP (2008) The dynamics of performance management: constructing information and reform. Georgetown University Press

Nielsen PA, Baekgaard M (2015) Performance information, blame avoidance, and politicians’ attitudes to spending and reform: evidence from an experiment. J Public Adm Res Theory 25(2):545–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut051

Nielsen PA, Moynihan DP (2017) How do politicians attribute bureaucratic responsibility for performance? Negativity bias and interest group advocacy. J Public Adm Res Theory 27(2):269–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw060

Nielsen PA, Jacobsen CB (2018) Zone of acceptance under performance measurement: does performance information affect employee acceptance of management authority? Public Adm Rev 78(5):684–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12947

Olsen AL (2015) Citizen (Dis)satisfaction: an experimental equivalence framing study. Public Adm Rev 75(3):469–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12337

Patel D (2013) Unveiled: transparency and democracy. Econ Voting Natl Front Towards Subregional Underst Extrem Right Vote Fr 13:124

Peters BG (2018) The politics of bureaucracy: an introduction to comparative public administration. Routledge

Petersen NBG (2020) Whoever has will be given more: the effect of performance information on frontline employees’ support for managerial policy initiatives. J Public Adm Res Theory 30(4):533–547. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa008

Petersen NBG, Laumann TV, Jakobsen M (2019) Acceptance or disapproval: performance information in the eyes of public frontline employees. J Public Adm Res Theory 29(1):101–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy035

Salamon LM, Elliott OV (2002) The tools of government action: a guide to the new governance. Oxford University Press

Schoon EW (2022) Operationalizing legitimacy. Am Sociol Rev 87(3):478–503

SCPRC (2013) Views on strengthening urban infrastructure [2013] NO. 36. Beijing, accessed 6 June http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2013-09/13/content_5045.htm

Simon HA (1947) Administrative behavior: a study of decision-making processes in administrative organization. Macmillan, New York

Song M, Illoong Kwon SC, Min N (2017) The effect of public service motivation and job level on bureaucrats’ preferences for direct policy instruments. J Public Adm Res Theory 27(1):36–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muw036

Stone DF, Wood DH (2018) Cognitive dissonance, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias: applications in industrial organization. Handbook of behavioral industrial organization. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp 114–137

Twight Charlotte (1991) From claiming credit to avoiding blame: the evolution of congressional strategy for asbestos management. J Public Policy 11(2):153–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00006188

Van Dooren W, Van de Walle S (2008) Performance information in the public sector: how it is used. Springer

Veselý A, Petrúšek I (2021) Decision makers’ preferences of policy instruments. Eur Policy Anal 7(1):165–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1082

Wang H, Fan C, Chen S (2021) The impact of campaign-style enforcement on corporate environmental action: evidence from China’s central environmental protection inspection. J Clean Prod 290:125881

Wang W (2016) Exploring the determinants of network effectiveness: the case of neighborhood governance networks in Beijing. J Public Adm Res Theory 26(2):375–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muv017

Weaver RK (1986) The politics of blame avoidance. J Public Policy 6(4):371–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00004219

Weber M (1978) Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology, vol 1. University of California Press

Woodhouse EF, Belardinelli P, Bertelli AM (2022) Hybrid governance and the attribution of political responsibility: experimental evidence from the United States. J Public Adm Res Theory 32(1):150–165

Wilson W (1887) The study of administration. Polit Sci Q 2(2):6. https://doi.org/10.2307/2139277

Yan B, Wu L, Wang XH, Wu J (2021) How can environmental intervention work during rapid urbanization? Examining the moderating effect of environmental performance-based accountability in China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 86:106476

Yi DJ, Woo JH (2015) Democracy, policy, and inequality: efforts and consequences in the developing world. Int Polit Sci Rev 36(5):475–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114525214

Zhang J, Wen X, Mao H, Xu R, Zhang S (2025) Does public officials’ risk preference differ in self versus public decision‐making? It depends on decision framing and bet size. Public Adm 103(2):510–535

Zheng Y (2007) De facto federalism in China: reforms and dynamics of central-local relations, vol 7. World Scientific