Abstract

Disseminating debunking information is an effective strategy for addressing rumours on social media. This study investigates the role of emotions—specifically emotional valence and discrete emotions—in the sharing of debunking information, with a focus on the moderating effect of the reputation of the rumour’s subject. We tested the research model proposed in this study using data sourced from Sina Weibo. The results revealed that emotional valence, whether positive or negative, significantly enhances the likelihood of sharing debunking information. Additionally, anticipation, trust, anger, sadness, and disgust all exhibit significant positive effects on sharing. Notably, the influence of emotional valence is contingent on the reputation of the rumour’s subject; both positive and negative sentiments prove more effective when the subject has a positive reputation, while the effect of negative sentiments is amplified when the subject is associated with a negative reputation. Additionally, post hoc analyses underscore the critical moderating role of subject reputation in shaping the impact of discrete emotions such as fear, sadness, and trust. This study not only deepens our theoretical understanding of how emotions influence the sharing of debunking information but also provides practical insights for stakeholders, helping them develop more effective debunking information disseminating strategies based on the reputation of the rumour’s subject.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social media’s ability to facilitate the creation, access, and dissemination of information, combined with its interactive features—such as sharing, liking, and following—provides an ideal environment for the rapid generation and spread of rumours (Himelboim et al. 2023; Kushwaha et al. 2022). The proliferation of rumours on these platforms can have detrimental effects on users (Donovan and Wardle 2020) and has become a growing concern in recent years (Bhattacherjee 2023; Li and Chang 2022). For instance, COVID-19-related rumours have resulted in regulatory ambiguity, undermined trust in scientific authorities, and hindered the adoption of essential precautions by individuals (Sarraf et al. 2024).

To combat rumours, social media platforms are increasingly collaborating with third parties to publish debunking information (Pal et al. 2019). Although such information has been shown to effectively correct misconceptions and reduce the dissemination of rumours, its success depends on its wide dissemination (Yu et al. 2022). Debunking information must be shared broadly to reach users who are already exposed to the rumours and influence those who have not yet encountered the falsehoods circulating on social media. However, existing research demonstrates that debunking information is far less prevalent than rumours on these platforms (Lazer et al. 2018), which restricts its reach. Consequently, debunking information often fails to reach all users previously exposed to rumours, let alone potential audiences for these falsehoods, thereby limiting its corrective impact (Yu et al. 2022). Promoting the sharing of debunking information among social media users is, therefore, essential to maximising its corrective potential and curbing the spread of rumours.

Affective processing plays a pivotal role in shaping human behaviour and involves the unconscious evaluation of the pleasant or unpleasant aspects of a stimulus (Walla 2018). While humans can engage in cognitive processing to refine affective evaluations, the hedonic nature of social media environments often induces users to minimise cognitive effort during information processing (Lutz et al. 2023). As a result, social media users are expected to rely heavily on emotional cues when engaging with debunking information. In this context, emotional cues refer to the emotions expressed within the content of debunking information, primarily conveyed through text (Raab et al. 2020), which stimulates users’ affective information processing (Walla 2018) and further influences their sharing decisions (Wang et al. 2022a).

However, the role of emotions in the sharing of debunking information has yet to receive significant attention. Some existing studies have reported contradictory findings regarding the influence of emotions on the sharing of debunking information (Chao et al. 2021; Pal et al. 2023). Assessing the impact of emotions carries both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, we do not yet understand how emotions in debunking information influence users’ sharing behaviour. Examining the relationship between emotions and the sharing of debunking information expands our knowledge of social media users’ behaviour in this context. Practically, assessing the impact of emotions may directly influence the design of debunking strategies. If emotional cues trigger affective information processing that prompts users to share debunking information automatically or unconsciously, it becomes essential to consider the role of emotions when designing debunking content.

Additionally, when developing communication strategies for debunking information, it is crucial to account for the influence of different rumour contexts on the factors affecting the sharing of debunking information (Chao et al. 2024; Yu et al. 2022). Rumours are often fabricated in reference to a specific object, known as the subject of the rumour (Chao et al. 2023). The subject of the rumour varies across different rumours, and users may have pre-existing attitudes toward the subject before encountering the rumour and debunking information (Sandlin and Gracyalny 2018). Social media platforms often reinforce these pre-existing attitudes, facilitating either a positive or negative sense of confirmation (Bhattacherjee 2001; Winter et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2016). Consequently, the role of emotions embedded in debunking information may be moderated by users’ pre-existing attitudes toward the reputation of the rumour’s subject (Chao et al. 2023). However, existing literature has not sufficiently addressed this potential boundary condition, making it challenging to achieve a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between emotions and the sharing of debunking information.

In sum, the intricate interplay between emotion and the sharing of debunking information remains insufficiently explored. Existing studies that investigate the relationship between emotional valence and the sharing of debunking information report contradictory findings (Chao et al. 2021, 2023; Pal et al. 2023), while even fewer studies examine the role of discrete emotions in this context, particularly with regard to their arousal levels. Moreover, the boundary conditions that influence the effect of emotions on the sharing of debunking information have yet to be systematically assessed. To address these research gaps, we propose the following research questions:

-

RQ1: How do emotions (including emotional valence and discrete emotions) impact the sharing of debunking information?

-

RQ2: How does the reputation of rumour subjects influence the effect of emotions on the sharing of debunking information?

This study introduces a comprehensive research framework to explain the intricate relationship between emotion and the dissemination of debunking information. The primary aim is to explore how and under what conditions emotions influence the sharing of debunking information. Theoretically, this study advances our understanding of the role of emotions in debunking information-sharing behaviour. Furthermore, the findings offer practical implications for social media practitioners, enabling them to leverage emotional expressions to enhance the sharing and dissemination of debunking information, thereby facilitating the effective governance of rumours.

Literature review and theoretical foundation

Debunking information and its sharing on social media

Rumours are among the oldest forms of mass communication (Kapferer 1987). Foundational work by Allport and Postman (1947) described rumours as “circulating statements about current events… lacking sufficient evidence to confirm their authenticity.” DiFonzo and Bordia (2007) defined them as “unconfirmed information in circulation, often arising in ambiguous or threatening situations.” While definitions avoid judging truthfulness, this paper focuses on rumours confirmed as false. Such content spreads widely on social media, distorting facts, inciting panic, and even contributing to political instability (Hoes et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2022).

To address misunderstandings and effectively mitigate the proliferation of rumours on social media, institutions, organisations, platforms, and scholars have invested significant resources and proposed various interventions. Among these, fact-checking has been one of the most extensively discussed methods for debunking rumours in prior research (Martel and Rand 2024; Porter and Wood 2021). However, the effectiveness of fact-checking remains inconsistent, with some studies suggesting that fact-checking labels may even produce counterproductive effects (Pennycook et al. 2020). In the search for more effective strategies to combat rumours, an increasing number of scholars have turned their attention to the role of debunking information (Prike and Ecker 2023).

As a crucial stage in the rumour lifecycle, the dissemination of debunking information is widely regarded as an effective strategy for curbing or halting the spread of rumours (Nyhan and Reifler 2010). Previous studies indicate that debunking information, regardless of its format, can effectively correct misconceptions and significantly reduce public trust in the false claims propagated by rumours (Swire-Thompson et al. 2021). This effect is particularly pronounced when debunking information is presented in a coherent, professional, and detailed manner, as this enhances its corrective impact (Walter et al. 2020; Walter and Tukachinsky 2020). As a result, disseminating debunking information has emerged as a vital and effective approach to correcting misunderstandings, disseminating factual information, and preventing the further spread of rumours (Yu et al. 2022).

Despite its proven efficacy, a significant challenge persists in using debunking information to counter rumours: debunking information is far less prevalent than rumours (Lazer et al. 2018). Consequently, it struggles to reach all users who have been exposed to rumours, thereby limiting its effectiveness (Chao et al. 2024; Yu et al. 2022). The primary reason for this limitation lies in the low likelihood of social media users sharing or reposting debunking information, even when they are exposed to it. Research indicates that users often exhibit a “high cognitive, low behavioural” engagement pattern with debunking content, where they cognitively process the information but refrain from actively sharing it (Zhao et al. 2016). For instance, more than half of social media users do not engage in debunking posts, which hampers their dissemination and reduces their corrective potential (Chadwick and Vaccari 2019).

Consequently, addressing the barriers to facilitating the sharing and dissemination of debunking information requires urgent attention. Existing studies have explored various factors influencing the sharing of debunking information, which can be categorised into source-based characteristics, content-based characteristics, and receiver-based characteristics. Table 1 summarises key findings from the literature on debunking information sharing.

While these studies provide initial insights into the factors affecting the sharing of debunking information, they have not sufficiently addressed the persistent problem of its limited dissemination (Yu et al. 2022). Thus, further research is necessary to identify additional factors that influence the sharing of debunking information and to develop strategies to overcome these barriers.

Walla’s (2018) theoretical model of affective information processing offers a promising framework for investigating the factors that shape the dissemination of debunking information. According to the model, affective processing is an evaluative process that involves the unconscious assessment of the pleasantness or unpleasantness of a stimulus and serves as the foundation for shaping human behaviour. Cognitive processing, as articulated in the model, can also influence affective evaluation (Lutz et al. 2023). However, in the social media environment, users often minimise cognitive effort (Moravec et al. 2019) and primarily seek entertainment (Kim and Dennis 2019), especially when interacting with debunking information (Zhao et al. 2016). In this context, affective information processing becomes a critical determinant of user attitudes and behaviours. When the emotions conveyed by the publisher of debunking information are presented to users in textual form (Goldenberg et al. 2020), these emotions act as external stimuli that activate the user’s affective information processing (Wang et al. 2022a). Consequently, emotion is likely one of the key factors influencing the sharing of debunking information.

Emotions and the sharing of information

Emotions are subjective human experiences that encompass feelings and thoughts, reflecting a positive or negative evaluation of an entity or an aspect of that entity (Chung and Zeng 2020). In online communication, emotions play a pivotal role in persuasion and user responses (Sahly et al. 2019), with emotional appeals eliciting arousal and amplifying the spread of messages on social media (Berger 2011). Circumplex theories of emotion propose that all emotions are characterised by two orthogonal dimensions: valence, which describes the degree to which individuals perceive a stimulus as positive or negative, and arousal, which refers to the intensity of the physiological response elicited by the stimulus (Pool et al. 2016).

From the perspective of valence, emotionally charged content (both positive and negative) tends to be shared more frequently than content devoid of emotional expression (Song et al. 2016; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013). Negative events, in particular, evoke more intense and immediate emotional, behavioural, and cognitive reactions compared to neutral or positive events (Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013). This preference for negative information can be understood from an evolutionary perspective, as focusing on negativity is believed to confer survival advantages (Soroka et al., 2019). Negative sentiments serve as alerts to potential dangers (Shoemaker 1996) and possess diagnostic and vigilance value (Skowronski and Carlston 1989; Irwin et al. 1967), which are essential for avoiding adverse outcomes.

Conversely, people may also favour sharing good news imbued with positive sentiments. Information is often considered a form of social currency, wherein an individual’s willingness to share a piece of information depends on how others may perceive them after sharing it (Berger 2016). Positive information is more likely to be shared because it reflects favourably on the sharer, creating a positive impression (Berger and Milkman 2012). Moreover, positive sentiments broaden attention spans, enhance creative problem-solving, and facilitate the formation of social connections (Nikolinakou and King 2018; Fredrickson and Branigan 2001). Research on the emotional tone of advertisements (pleasant vs. unpleasant) demonstrated that a pleasant emotional tone significantly enhanced users’ perceptions of the advertisement, their attitudes toward the brand, and their likelihood of sharing the content (Eckler and Bolls 2011).

Unlike emotional valence, discrete emotions with varying levels of arousal offer deeper insights into the mechanisms through which emotion influences sharing behaviour (Flores and Hilbert 2023; Lee et al. 2023). Positive emotions, such as surprise, excitement, and happiness, as well as negative emotions, such as anger and anxiety, are classified as high-arousal emotions. Conversely, positive emotions like contentment and negative emotions like sorrow fall under the category of low arousal emotions (Ren and Hong 2019). Compared to content that induces low-arousal, high-arousal content elicits a stronger inclination to share and a heightened willingness to disseminate it (Berger, 2011; Berger and Milkman 2012; Nelson-Field et al. 2013). In the emotion wheel framework proposed by Plutchik (1980, 2001), eight fundamental discrete emotions are defined: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, joy, surprise, anticipation, and trust. These basic emotions serve as adaptive mechanisms for humans and are universally recognised across cultures (Xu et al. 2023). This study specifically investigates the effects of six discrete emotions—anticipation, trust, anger, fear, sadness, and disgust—on the sharing of debunking information.Footnote 1

While the role of emotions in information sharing has been extensively studied in other domains, limited research focuses on their role in the dissemination of debunking information. Unlike general information sharing, debunking information is inherently persuasive, as its primary aim is to correct existing misconceptions rather than simply convey new information. Thus, the sharing of debunking information constitutes a persuasive communication process, making it critical to examine the influence of emotion within this context. Chao et al. (2023) explored the effect of emotional cues through the lens of the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), while Pal et al. (2024) highlighted how the pleasure elicited by debunking information fosters a positive inclination to share it on social media. However, more recently, Pal et al. (2023) reported that emotionality did not predict the virality of debunking information. These contradictory findings underscore the need for further exploration of the role of emotions in the sharing of debunking information. Moreover, prior research has predominantly focused on the role of emotional valence (positive or negative) in debunking information sharing, with limited attention given to the influence of discrete emotions. Yet, discrete emotions may carry more valuable and nuanced information than emotional valence alone (Flores and Hilbert 2023).

Additionally, Rumours are often directed at a specific target, which may be a public figure, a corporation, or an organisation (Chao et al. 2023). Prior to being exposed to debunking information, users may be familiar with the rumour subject and develop a pre-existing attitude towards them based on the rumour subject’s prior reputation (Sandlin and Gracyalny 2020), which is reflected in their decisions to search, comment on, and share information on social media. Thus, the reputation of the subjects involved in a rumour may be one of the boundary conditions that determine the role of emotions in the sharing of debunking information.

Reputation of the rumour subject

According to Walker (2010), reputation is defined by five key attributes: it is based on perceptions, represents a composite of perceptions from all stakeholders, is comparable, is either positive or negative, and is stable and enduring. Based on these attributes, reputation can be described as the cumulative sum of perceptions about a subject’s image gathered by various stakeholders over time through multiple media channels (Mailath and Samuelson 2001). In the context of rumour propagation on social media, social media users act as stakeholders who, even before a rumour begins to spread, acquire information about the rumour subject through various media tools. This pre-existing exposure shapes their attitudes toward the rumoured subject. Therefore, we define the reputation of the rumour subject as the prior knowledge of the rumour subject’s reputation acquired by social media users through various media tools before the occurrence of the rumour event.

Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT) provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding the role of reputation. Originating from research on consumer satisfaction, ECT explains the relationship between people’s expectations and their actual experiences with a product, service, or relationship (Oliver 1980). The theory posits that individuals form expectations before encountering something new. When their actual experience aligns with these expectations, positive validation occurs (Bhattacherjee 2001). In this situation, the beliefs conveyed in a message match an individual’s pre-existing beliefs, minimising the cognitive effort required to process the information—referred to as cognitive fit (Hong et al. 2004). Cognitive fit enhances problem-solving performance. Conversely, when actual experiences contradict expectations, negative validation occurs (Bhattacherjee 2001). A mismatch between the message’s conveyed beliefs and the individual’s personal beliefs prevents cognitive fit, leading to less efficient and effective information processing (Vessey and Galletta 1991).

ECT has been widely applied in studies on organisational reputation. For example, research has demonstrated that when people’s expectations of an organisation’s reputation are met, they feel satisfied and continue to support the organisation (Bhattacherjee 2001). Additionally, ECT has been employed in studies of corporate reputation and employer branding. Eccles et al. (2007) found that consumers hold higher expectations of companies with strong reputations, and these expectations enhance their anticipation of high-quality products, ultimately increasing their willingness to purchase (Yoon et al. 1993). Similarly, a strong employer reputation leads the public to expect effective human resource management practices (Lee et al. 2020). A favourable employer reputation signals the organisation’s ability to provide a positive working environment for employees, fostering positive attitudes and expectations about its performance in employee relations.

In the context of debunking rumours, users’ prior knowledge of a subject shapes their perception of the subject’s reputation and forms their expectations. When a subject has a good or bad reputation, users develop corresponding positive or negative expectations. When these expectations align with or contrast against the emotional content of debunking information, users experience positive or negative confirmation, which can either enhance or reduce their engagement with the content. Thus, users’ perceptions of a subject’s reputation may significantly influence how they emotionally process debunking information.

In sum, we currently lack a deeper understanding of how emotions influence the sharing of debunking information. Specifically, there is insufficient evidence to establish the positive role of emotional valence in debunking information sharing. Additionally, discrete emotions with varying levels of arousal have not yet been examined for their effects on this process. Moreover, it remains unclear when emotions influence debunking information sharing, as there may be heterogeneity in the role of emotions based on differences in the reputation of the rumoured subject. These gaps in the literature highlight the need for further research on the role of emotions in debunking information sharing and the boundary conditions under which they operate.

This study draws on several theoretical frameworks, summarised in Table 2: affective information processing theory, emotional contagion theory, circumplex theory of emotion, the emotion wheel model, and ECT. These theories inform our research motivation, model, and questions. Our theoretical logic is as follows: The text of debunking content often expresses the author’s emotions. Based on emotional contagion theory, these emotional cues act as external stimuli (Chen et al. 2023; Raab et al. 2020). When received, they activate affective information processing, which involves unconscious evaluation and influences sharing behaviour (Lutz et al. 2023; Walla 2018). Drawing on circumplex theory of emotion (Pool et al. 2016) and the emotion wheel model (Plutchik 1980), we consider the impact of emotions from both valence and arousal perspectives. Finally, based on ECT (Lee et al. 2020), we examine how the rumour subject’s reputation moderates emotional influence.

Research hypotheses

Effect of emotions on debunking information sharing

Effect of emotional valence

Positive bias is prevalent on social media platforms, where individuals often prefer to express positive aspects of their true selves rather than focusing on negative traits (Reinecke and Trepte, 2014). Content imbued with positive sentiment tends to attract greater attention (Kissler et al. 2007) and elicits heightened states of arousal (Berger 2011). This heightened arousal influences feedback mechanisms, reciprocal behaviours, and social sharing tendencies (Berger and Milkman 2012; Dang-Xuan and Stieglitz 2012). In the context of debunking, embedding positive sentiments into content may significantly impact sharing behaviour. Users are more likely to share content that aligns with their desire to maintain a positive online image while constructively contributing to their social network (Berger 2016). Additionally, positive emotions in debunking information can foster social connectedness and encourage participation in social interactions, including liking, commenting, and sharing (Berger and Milkman 2012; Dang-Xuan and Stieglitz 2012). Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1a: Positive sentiment embedded in debunking information positively affects sharing compared to neutral sentiment.

In contrast, people are inherently inclined to pay greater attention to negative stimuli, a tendency deeply rooted in evolutionary biases and reinforced by past experiences (Rozin and Royzman 2001). This inclination has been observed across a wide range of contexts (Soroka et al. 2019). When debunking information that contains negative sentiments targeting the potential negative impact of a rumour, it leverages users’ inherent preference for attending to and reacting to negative stimuli (Soroka et al. 2019). This heightened attention increases the perceived urgency and importance of the message, making users more likely to share the information to prevent the spread of falsehoods or to protect their social networks from harm (Chao et al. 2023). Additionally, individuals strive to maintain or enhance a positive social identity as a means of boosting self-esteem (Brady et al. 2020). This positive social identity is often derived from favourable comparisons between the in-group and a relevant out-group (Brady et al. 2020). When debunking information includes negative sentiments against rumours or rumour mongers, users may express their disapproval of this by sharing the information, thereby reinforcing their positive social identity. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b: Negative sentiment embedded in debunking information positively affects sharing compared to neutral sentiment.

Effect of discrete emotions

The circumplex theory of emotion posits that the effects of emotional stimuli on attentional selection depend on their potential to stimulate emotional arousal rather than solely on emotional valence (Anderson 2005; Pool et al. 2016). High-arousal emotions are more likely to drive virality compared to low-arousal emotions (Berger and Milkman 2012).

Anticipation is a high-arousal positive emotion that emerges when individuals connect past experiences with the current situation (Gaylin 1979). Anticipatory emotions are often viewed as how we perceive future events (Mellers et al. 1999), specifically the emotion of anticipation triggered by the expectation of an impending reward (Kalat and Shiota 2007). In the context of debunking information, anticipation often arises from prompting users to take action—such as avoiding rumour spread or sharing debunking information—to promote a harmonious online space (Pal et al. 2023). This emotion may excite users about forthcoming results, findings, or investigations (Chen 2024), thereby increasing their willingness to share debunking information. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2a: The emotion of anticipation embedded in debunking information positively affects information sharing.

Trust is defined as the willingness to embrace vulnerability, contingent upon positive expectations of an object (Chen 2024; Dunn and Schweitzer 2005). Trust can exist between individuals, groups, and institutions (Butler 1991)Footnote 2and serves as a fundamental emotion underpinning the effective functioning of social systems (Bazerman 1994). Trust is generally considered a low-arousal emotional experience (Russell 1980). In trust-related situations, individuals tend to feel relaxed and stable, with mental activity remaining calm rather than tense or anxious (Russell 1980). In the context of debunking rumours, trust primarily manifests as trust in the information source or the entity responsible for debunking the rumour (Chao et al. 2023). Given the low-arousal nature of trust, this emotion may not inherently stimulate a stronger desire to share information. Specifically, a calmer, more rational emotional state generally reduces the urge to disseminate information widely. Therefore, we hypothesise:

H2b: The emotion of trust embedded in debunking information will have a negative impact on information sharing.

Conversely, negative discrete emotions embedded in debunking information, such as anger, fear, sadness, and disgust, may also influence sharing behaviour. Anger is a high-arousal negative emotion associated with certainty (Smith and Ellsworth 1985) and often implies aggression (Plutchik 1980). The function of anger is to remove barriers to goal attainment or well-being, and individuals experiencing anger are often more impulsive in their responses (Bodenhausen et al. 1994) and more likely to take action to eliminate obstacles or resolve problems (Oh et al. 2021). Anger is mobilised and sustained when individuals feel the need to defend themselves, protect loved ones, or right a wrong (Nabi 2002). Additionally, when the moral values of a group are compromised, individuals involuntarily react with anger towards the source of this threat (Brady et al. 2020). In the context of debunking a rumour, the anger contained in the information can lead to a high level of arousal and increased engagement. Specifically, anger in debunking information will make it more likely that users will share the information to correct falsehoods in rumours and remove obstacles that threaten their interests (e.g., lives and health). Additionally, users may be more willing to share debunking information containing anger as a way to signal disapproval (against rumours and rumour mongers). Hence, we hypothesise:

H2c: The emotion of anger embedded in debunking information positively affects information sharing.

Fear is another negative emotion that is high arousal, but it is marked by uncertainty (Smith and Ellsworth 1985). Research suggests that fear can positively influence consumer attitudes, behaviours, and intentions (Tannenbaum et al. 2015). Messages that evoke fear by emphasising possible harmful consequences are effective in persuading recipients to take the message seriously (Dillard et al. 1996). In the context of debunking, fear refers to an avoidance reaction triggered by an immediate or perceived threat (Plutchik 1980; Association 2013). Thus, fear-based debunking information may prompt users to share it as a way of helping others avoid harm (Ren and Hong 2019). Therefore, we hypothesise:

H2d: The emotion of fear embedded in debunking information positively affects information sharing.

Sadness is a low-arousal negative emotion that reflects a sense of loss and extreme unpleasantness (Ren and Hong 2019). Unlike anger, which is associated with certainty, sadness evokes uncertainty and is characterised by a low level of anxiety (Smith and Ellsworth 1985). Prior studies have shown that social media posts expressing sadness often result in reduced engagement (Utz 2011) and negatively impact the dissemination of online news (Berger and Milkman 2012). In the context of debunking information, sadness, due to its low arousal and low-anxiety nature, makes it more difficult for individuals to make spontaneous judgments. As a result, users may process debunking information more cautiously and slowly, reducing their willingness to share it further. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2e: The emotion of sadness embedded in debunking information negatively affects information sharing.

The central relational theme of disgust is ‘being in close proximity or too close to an object or idea that is difficult to digest” (Malik and Hussain 2017). Disgust arises when something causes harm or has the potential to cause harm (Dobele et al. 2007). It is associated with a high degree of certainty about the present situation and an unpleasant emotional state (Ahmad and Laroche 2015). Similar to anger, disgust is a high-arousal and high-anxiety emotion (Brady et al. 2017), which can heighten user engagement. In the context of debunking information, expressions of disgust—like anger—often disparage the rumour-monger, sending a clear signal of disapproval (Brady et al. 2020). Sharing debunking information that conveys disgust may satisfy users’ desire to uphold a positive group image in response to a group threat by devaluing the out-group, thereby increasing their willingness to share. Based on this reasoning, we hypothesise:

H2f: The emotion of disgust embedded in debunking information positively affects information sharing.

Moderating the role of subject reputation in the effect of emotional valence

Rumours frequently target specific individuals or entities, referred to as the rumoured subject (Chao et al. 2023). Before encountering rumour and debunking information, users may already have pre-formed opinions about the rumoured subject and the events surrounding them (Sandlin and Gracyalny 2018). Social media platforms often reinforce users’ pre-existing attitudes by providing relevant information that aligns with their biases (Winter et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2016). As a result, users may decide to engage in debunking information based on their inclination to confirm or express their biases regarding public figures or entities (Sandlin and Gracyalny 2018). Given this dynamic, it is reasonable to hypothesise that the influence of positive or negative sentiment within debunking information on sharing behaviour may be moderated by users’ pre-existing perceptions of the rumour subject’s reputation. Specifically, users’ preconceptions about whether the rumoured subject is perceived positively or negatively may amplify or diminish the effect of emotional valence in shaping their willingness to share debunking information.

Based on the ECT, positive confirmation occurs when a user’s expectations align with their experience (Bhattacherjee 2001). When a subject possesses a favourable reputation, users tend to form positive expectations about that subject. These expectations are confirmed when the message conveys prevailing positive sentiments (Lee et al. 2020). This validation increases the persuasiveness of the message and enhances user engagement (Lee et al. 2020). Similarly, in the context of debunking information, a rumour subject with a positive reputation leads users to form favourable expectations (Chao et al. 2023). When the debunking information conveys positive emotions, such as trust and optimism, toward the subject, these expectations are reinforced, thereby increasing users’ willingness to share the debunking information. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3a: The positive reputation of the rumoured subject enhances the effect of positive sentiments.

The positive reputation of the rumoured subject may also amplify the impact of negative sentiments in debunking information. By blaming the rumour and its creators, debunking information containing negative sentiments may evoke the audience’s righteous indignation (Asif and Weenink 2022; Green et al. 2019; Peng et al. 2023). In this way, negative sentiments in debunking information may serve to maintain the subject’s positive reputation. When the subject has a positive reputation, the negative sentiments in debunking information can create a sense of positive confirmation among users, thereby increasing their willingness to share the debunking information. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3b: The positive reputation of the rumoured subject enhances the effect of negative sentiments.

Conversely, when the rumoured subject has a negative reputation, users tend to form negative expectations about that subject. Positive sentiments conveyed in the debunking information create an inconsistency between the user’s expectations and experience. According to ECT (Lee et al. 2020), a mismatch between the user’s beliefs and the message disrupts cognitive fit, reducing information processing efficiency and lowering the user’s willingness to share debunking information. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3c: The negative reputation of the rumoured subject weakens the effect of positive sentiments.

However, negative sentiments in debunking information do not confirm users’ negative expectations of the rumoured subject. As previously discussed, negative sentiments in debunking information are primarily aimed at expressing dissatisfaction with the rumour and its creator (Peng et al. 2023). In these cases, publishers of debunking information seek to enhance persuasiveness by evoking strong emotions in the audience (Peng et al. 2023). When the rumour subject’s reputation is negative, this effort to maintain the subject’s reputation by blaming the rumour and its creator becomes less effective, as it conflicts with the user’s expectations. Users may not perceive the subject’s reputation as worth defending. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3d: The negative reputation of the rumour subject weakens the effect of negative sentiments.

Figure 1 summarises these hypotheses.

Research methods

Data collection

Data were collected from Sina Weibo, a platform with 586 million monthly active users and an average of 252 million daily active users, making it a significant source of information and interaction in China (Wang et al. 2022a). Similar to Twitter (now officially renamed X), Weibo users can publish posts and interact through commenting, liking, and reposting (Zhang et al. 2022). We utilised the Sina Weibo business application programming interface (API) via a well-known social media data service, Zhiwei Data, Beijing, China, http://university.zhiweidata.com/) to collect the data. A keyword-targeting approach was employed to ensure dataset completeness, using different keyword combinations for repetition. Corresponding reposts were also captured using the URLs of the original debunking posts. The dataset included 626 rumours related to COVID-19, along with 16,934 original debunking posts and 242,973 reposts, spanning from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020. Examples of rumours and debunking posts are provided in Supplementary Table A1 of Supplementary Appendix A. Figure 2 illustrates the data collection and processing details.

Operation of variables

The dependent variable in this study was the sharing of debunking information, operationalised as the number of reposts per original debunking post. The independent variables included emotional valence and discrete emotions. Emotional valence was coded as a ternary variable, categorising sentiments into neutral, positive, and negative.

To improve classification efficiency, we developed a sentiment classifier to automatically identify the emotional valence embedded in the original debunking posts. First, three annotators manually labelled 5000 randomly selected original posts for emotional valence. The dataset was then divided into training and testing subsets with an 8:2 ratio. Sentiment classifiers were constructed using the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model, an advanced pre-trained language model introduced by Google that has become foundational in natural language processing (Devlin et al. 2019).

The performance of the classifier was assessed using accuracy and F1 scores. Various hyperparameter combinations were tested to optimise performance. The best-performing configuration (max_seq_length: 128, train_batch_size: 32, learning_rate: 4e−5, num_train_epochs: 3.0) achieved an accuracy of 0.801 and an F1 score of 0.789. These results demonstrate satisfactory performance compared to previous studies on social media sentiment analysis (accuracy: 0.803, F1 score: 0.665; Wang et al. 2022b). The trained classifier was subsequently employed to predict the emotional valence of all original debunking posts (examples are provided in Supplementary Appendix B).

Discrete emotions included four negative emotions (anger, fear, sadness, and disgust) and two positive emotions (anticipation and trust). These were operationalised as binary variables, with manual labelling performed to identify the presence or absence of each emotion. For instance, if a debunking post contained the emotion of anger, it was coded as “1”; otherwise, it was coded as “0” (see Supplementary Appendix B for examples of posts with different discrete emotions).

The subject’s reputation in the rumour was operationalised as a ternary variable. Professionals were invited to score the subject’s reputation based on established annotation rules (see Supplementary Appendix C for the annotation rules), with annotators assessing the reputation by considering the question, ‘Do you think this subject has a positive reputation?’, with ‘1’ being a definite no and ‘5’ being a definite yes (Sandlin and Gracyalny 2020). Scores below three were coded as negative reputations, above three as positive reputations, and exactly three as neutral reputations (Choi 2022).

In addition to these variables, several factors may influence the sharing of debunking information. We reviewed relevant literature and categorised these factors into rumour, information publisher, content, and contextual factors. Rumour factors included the rumour type (Song et al. 2021), importance, ambiguity (Allport and Postman 1947; Sun et al. 2022), polarity (Kamins et al. 1997), and the motivation of the rumour mongers (Metzger et al. 2021). Information publisher factors included the publisher’s identity type and the number of followers (Brady et al. 2017; Ferrara and Yang 2015; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013). Content factors included whether the information contained hashtags, URLs, pictures, or videos (Brady et al. 2017; Ferrara and Yang 2015; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013), and contextual factors included culture (Dobele et al. 2007).

The inclusion of these control variables served two purposes. First, they reduced systematic bias from confounding factors. By controlling for variables that could affect both the independent and dependent variables, we eliminated backdoor paths, allowing us to accurately identify the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. For instance, the polarity of a rumour could act as a potential confounder, as it might influence both emotional expression and sharing behaviour. Second, certain control variables, such as the presence of hashtags, URLs, pictures, or videos, were included to improve the precision of the estimates, even though they may not directly reduce systematic bias.

Annotation consistency tests were conducted for all variables requiring manual annotation, with results presented in Supplementary Appendix D. Table 3 provides a description of the key variables. The statistical and analytical results for the key variables are presented in subsequent sections.

Analysis methods

Methods for analysing data based on causal diagrams

Causal diagrams, which use graphs to represent the data generation process (Huntington-Klein 2021; Pearl 2009), were employed to guide data analysis. These diagrams consist of two elements: variables and causal relationships (Huntington-Klein 2021). Each variable is represented as a node, while causal relationships are indicated by arrows pointing from the causal variable to the outcome variable (Huntington-Klein 2021). These diagrams help identify core control variables and close backdoor paths, thereby enabling accurate causal inference (Chao and Yu 2023; Pearl and Mackenzie 2018).

Moreover, causal diagrams prevent errors such as inadvertently severing front-door paths or introducing new backdoor paths (Chao and Yu 2023; Pearl and Mackenzie 2018). Relationships between independent and dependent variables were identified by controlling for confounding variables (common causes of both independent and dependent variables) and other influencing factors (variables that independently affect dependent variables) while avoiding the inclusion of collider variables (common effects of independent and dependent variables).

Based on prior research (Allport and Postman 1947; Brady et al. 2017; Ferrara and Yang 2015; Kamins et al. 1997; Metzger et al. 2021; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013; Sun et al. 2022a), the core control variables included potential confounders such as rumour importance, ambiguity, polarity, and rumour mongers’ motivations (rumour factors), as well as the debunker’s identity (information publisher factors). Additional control variables, such as tags, URLs, reputation, and videos (content factors), were also included to improve the precision of the estimates.

Tests for moderating effects

The hypotheses in this study were tested using econometric methods (Wooldridge 2015), with regression techniques applied to analyse the data. A hierarchical regression approach was adopted to examine the main and moderated effects of the variables (Alashoor et al. 2022). This process involved two steps:

The main effect of sentiment is considered significant when the value of \({\beta }_{1}\) is statistically different from zero.

The second step of the test is as follows.

The moderated effect of reputation was considered significant if the interaction coefficient \({\beta }_{3}\) was statistically different from zero.

Data analysis and results

Descriptive statistics

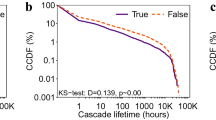

To visually illustrate the correlation between emotional valence and the dissemination of debunking information, a first-level repost network of the original debunking posts was constructed. This network was based on the sentiment prediction results obtained from the classifiers mentioned earlier. Reposting and spreading debunking information were represented as a graph, where the vertices denoted posts (either original or reposted), and the edges depicted the reposting relationships between them (Sarıyüce et al. 2016). The forwarding network was constructed using Gephi. In Fig. 3, each circle represents a propagation path originating from an original post, with different colours representing different emotional valences of the original posts. Larger circles indicate posts with higher repost counts.

The graph reveals that posts with positive sentiment (red) and negative sentiment (green) are more likely to be widely reposted compared to posts with neutral sentiment (blue). Specifically, in the first figure, the diameters of circles corresponding to positive and negative sentiment posts are significantly larger than those of neutral sentiment posts. Similarly, in the subsequent figures, the circles formed by reposts of debunking posts with neutral sentiment are consistently smaller compared to those of posts with positive and negative sentiment. This indicates that neutral posts elicit less enthusiastic responses and are less likely to be widely shared.

In summary, the network analysis demonstrates a clear correlation between emotional valence and the spread of debunking information. Posts with positive or negative sentiments tend to achieve broader dissemination compared to those with neutral sentiments, as observed through the transmission network constructed using complex network analysis.

To further investigate and translate these observed correlations into a reliable causal relationship, we utilised 5000 manually labelled data points for additional analysis. Table 4 provides a statistical summary of the variables, offering insights into the distribution and characteristics of the dataset (see Supplementary Appendix E for a complete statistical summary).

Regression analysis

We used Stata 14 to analyse the data. A negative binomial regression model was employed to perform the hierarchical regression as outlined in the analytical methods. This approach was chosen because the dependent variable, reposts, is count data and exhibited significant dispersion (M = 14.83; SD = 436.07). Initially, we examined the effects of emotional valence on the sharing of debunking information and the moderating role of rumour subject reputation in this relationship. Table 5 summarises the regression results.

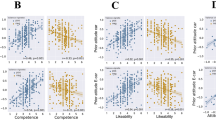

As shown in Model 2 of Table 5, both positive sentiment (β = 1.449, p < 0.001) and negative sentiment (β = 1.454, p < 0.001) have significantly positive effects on reposts compared with neutral sentiment. These findings provide support for H1a and H1b.

The regression results after including the interaction term are shown in Model 3 in Table 5. The results indicate that positive reputations significantly moderated positive sentiment (β = 1.667, p = 0.001). However, the moderating effect of negative reputations on positive sentiment is not statistically significant (β = −0.278, p = 0.714). By contrast, positive reputations have a significantly positive moderating effect on negative sentiment (β = 1.321, p = 0.003), and similarly, negative reputations have a significantly positive moderating effect on negative sentiment (β = 2.081, p = 0.006). These findings support H3a and H3b, while H3c and H3d were not supported.

Next, we examined the effect of different discrete emotions on the sharing of debunking information. The results are shown in Models 1 and 2 in Table 6.

As shown in Model 2 of Table 6, three negative emotions (anger, sadness, disgust) and two positive emotions (anticipation, trust) significantly influence the sharing of debunking information (anticipation: β = 0.831, p < 0.001; trust: β = 1.018, p = 0.001; anger: β = 0.508, p = 0.004; sadness: β = 3.423, p < 0.001; disgust: β = 1.246, p < 0.001). The effect of fear on sharing, although positive, is statistically insignificant (β = 0.120, p = 0.810). These findings support H2a, H2c, and H2f, but H2b, H2d, and H2e are not supported.

We further explored the moderating role of subject reputation. Due to limited literature, we conducted post hoc analyses. Model 3 in Table 6 shows that subject reputation moderates the effects of fear, sadness, and trust. Positive reputation significantly moderates trust (β = 1.986, p < 0.001) and fear (β = 2.533, p = 0.014). For sadness, a positive reputation has a stronger moderating effect (β = 6.096, p < 0.001) than a negative reputation (β = 3.591, p = 0.005). Robustness checks confirm the reliability of these results (Supplementary Appendix F).

Discussion

Main findings

This study examined the impact of emotional valence and discrete emotions on the sharing of debunking information, along with the moderating role of rumour subject reputation. The primary findings are summarised in Table 7 and discussed in four key areas.

The role of emotional valence in debunking information sharing

Our findings indicate that both positive and negative sentiments significantly increase the sharing of debunking information compared to neutral sentiments. This result aligns with prior studies (Chao et al. 2021, 2023), demonstrating that emotional valence in debunking information has effects similar to those observed in other forms of information transmission (Berger and Milkman 2012; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013). Previous research suggests that emotional stimuli attract users’ attention, which in turn influences their information processing (Voinea et al. 2024). Positive sentiment may encourage sharing through its association with enhanced attention, cognition, and critical thinking (Fredrickson and Joiner 2002; Ferrara and Yang 2015). Therefore, when users encounter debunking information containing positive sentiments, they are more likely to engage in cognitive processing and social communication, which motivates sharing. Furthermore, individuals often prefer sharing content that projects them in a positive light to their social groups (Berger 2016). Consequently, debunking information with positive sentiment becomes more shareable as it aligns with users’ desire for positive self-presentation.

The influence of negative sentiments on sharing and debunking information can be attributed to two primary factors: Fear of rumour consequences and social pressure to hold negative views of rumour mongers. Evolutionarily, negative sentiments are prioritised, as they help in survival (Flykt 2006; Öhman et al. 2001; Soroka et al. 2019). When users perceive threats or risks associated with rumours, negative sentiments may trigger protective behaviours, such as sharing debunking information to mitigate potential harm (Lovett et al. 2013; Syn and Oh 2015). Additionally, sharing debunking information with negative sentiment may stem from alignment with social norms. Social groups often express strong disapproval of rumour mongers, and users influenced by social identity theory may share content to align themselves with the values of their group (Rimal and Real 2005; Lee et al. 2011).

The role of discrete emotions in the sharing of debunking information

Our findings showed that three negative emotions (anger, sadness, and disgust) and two positive emotions (anticipation and trust) significantly increased the sharing of debunking information. As expected, anticipation played a significant role in facilitating the sharing of debunking information. As a high-arousal emotion, anticipation reflects the expectation of a positive outcome (Plutchik 1994). This emotion enhances emotional well-being and triggers positive emotional responses (Tellis et al. 2019), which can lead recipients to form favourable perceptions of the sharer (Isen 2008). These favourable perceptions likely encourage users to share debunking information containing anticipatory emotions. Similar to anticipation, trust, a low-arousal emotion, also positively influenced the sharing of debunking information. In the debunking process, trust is typically expressed by highlighting the credibility of the source or the debunking information itself. In the context of COVID-19, individuals exposed to rumours often experience heightened emotions such as worry, fear, scepticism, or anxiety (Meng et al. 2021). This uncertainty drives users to seek reliable information. Debunking information that conveys trust satisfies this need for certainty, making it more impactful and persuasive and, consequently, more likely to be shared.

Anger, a high-arousal negative emotion, was also found to significantly promote the sharing of debunking information. In the Chinese context, anger is often expressed by proposing punishments for rumour-mongers and disseminators (Peng et al. 2023). This expression of anger fosters unity among social media users, increasing their trust and support for debunking efforts. Additionally, anger motivates users to take action to protect their interests or those of others. Sharing debunking information containing anger aligns with users’ negative attitudes toward rumour mongers, further incentivising sharing behaviour. The positive effects of disgust were consistent with expectations. By emphasising the personal responsibility of rumour mongers and disseminators, disgust reinforces trust in debunking efforts (Peng et al. 2023). When users encounter a rumour, disgust elicits aversion toward both the rumour and the rumour monger, motivating users to share information that actively counters the rumour. Contrary to expectations, sadness, a low arousal emotion, also positively influenced the sharing of debunking information. This aligns with findings by Robertson et al. (2023), who observed that sadness positively impacted news consumption. A plausible explanation is that sadness may evoke sympathy towards subjects with either positive or negative reputations, thereby increasing users’ willingness to share debunking information. This finding offers an alternative perspective on the influence of negative sentiment on debunking information sharing, which is further elaborated in Sections “The influence of the rumour subject reputation on the role of emotional valence” and “The impact of rumour subject reputation on the role of discrete emotions”.

In contrast, while the effect of fear on sharing was positive, it was not statistically significant. This result aligns with Robertson et al. (2023), who found that fear exerted a significant negative effect on news consumption. The effect of fear appears to be highly context-dependent. In the context of COVID-19, fear was primarily induced by conspiracy theories (e.g., the claim that Chen Quanjiao from Wuhan Virus Research Institute revealed the director’s identity, with the insinuation that “the truth is chilling”). Exposure to conspiracy theories often reduces pro-social behaviours and erodes trust in scientific information (Van der Linden 2015), thereby decreasing the likelihood of sharing debunking information.

The influence of the rumour subject reputation on the role of emotional valence

Our findings revealed that the positive effects of positive sentiments on the sharing of debunking information were significantly amplified when the rumoured subject had a positive reputation. This moderation may be explained using ECT (Lee et al. 2020). When subjects are perceived positively, the sentiment in the debunking message aligns with users’ prior beliefs. This congruence enhances the emotional connection with the information, making it more likely to be shared. Conversely, when the subject has a negative reputation, positive sentiments fail to evoke favourable emotions in users due to their pre-existing negative impressions, which act as barriers to sharing the debunking information.

Additionally, the reinforcement of negative sentiments by a positive reputation can be attributed to two plausible mechanisms: On the one hand, negative sentiments in debunking information often reflect disapproval of rumour mongers. This reinforces the positive perception of the subject, validating users’ pre-existing beliefs. By sharing debunking information that condemns the rumour and its creator while maintaining the subject’s positive reputation, users confirm their expectations and strengthen their alignment with the subject. On the other hand, certain negative sentiments, such as sadness, are closely associated with empathy (Cialdini et al. 1987). When users empathise with a subject they perceive positively, compassion—a pro-social emotion arising in challenging situations (Lazarus 1991)—is triggered. Compassion drives pro-social behaviours, such as sharing information that benefits others (Gross 2008; Nabi et al. 2019). In this context, users may share debunking information not only to refute rumours but also to express solidarity and support for the subject.

Unexpectedly, our analysis found that the positive impact of negative sentiments on debunking information sharing was amplified when the rumoured subject had a negative reputation. This finding may also be related to empathy. When users encounter debunking information expressing specific negative emotions, such as sadness, they may experience empathy despite their negative impressions of the subject. This empathetic response may drive users to share the information, highlighting the complex interplay between emotional valence and subject reputation in shaping sharing behaviour.

The impact of rumour subject reputation on the role of discrete emotions

Our findings indicated no significant difference in the impact of anger and disgust on the sharing of debunking information across different subject reputations. One explanation is that rumour-mongers, often central to rumours, are generally viewed negatively across contexts (Chao et al. 2023). Consequently, the roles of anger and disgust in driving sharing behaviour remain consistent, regardless of the reputation associated with the rumoured subject.

A positive reputation, however, significantly moderated the effect of fear. When rumours involve positively portrayed subjects, users’ belief in conspiracy theories embedded in the message may be diminished (Lewandowsky et al. 2017), thereby increasing user engagement. This suggests that positive reputations can alleviate the distrust or scepticism typically associated with fear-inducing content, encouraging sharing behaviour.

Additionally, the subject reputation played a critical moderating role in the effect of sadness. As discussed previously, compared to subjects with neutral reputations (where no clearly defined subject is present), rumours involving subjects with either positive or negative reputations evoke stronger sympathy through sadness. This sympathy drives pro-social behaviours, such as sharing debunking information to benefit others.

The moderating effect of a positive reputation on the relationship between trust and sharing was also significant. Due to confirmation bias, trust-based appeals are effective only when the rumoured subject is perceived as trustworthy. This reinforcing effect may be particularly pronounced in the context of COVID-19, which has been characterised by heightened ambiguity and uncertainty. Under such circumstances, the perceived reputation of the rumoured subject becomes a critical determinant of whether trust can effectively influence sharing behaviour. Specifically, in uncertain environments, trust’s ability to drive engagement depends heavily on whether users perceive the rumoured subject as credible and reputable. By contrast, the role of expectation in sharing behaviour did not significantly differ across subject reputations. Unlike trust, the effect of expectations expressed by the information publisher appears to depend more on the publisher’s attributes and less on the rumour subject’s reputation. Calls to action embedded with expectations often shift the focus away from the rumoured subject, redirecting attention towards a hopeful or positive future. This diversion of focus may weaken the influence of the rumour subject’s reputation, making it less relevant in determining the effectiveness of expectation-driven appeals.

Theoretical implications

This study offers key theoretical insights into how emotion influences debunking information sharing. First, we confirmed that emotional valence positively affects such sharing. Compared to neutral emotions, both positive and negative emotions significantly boosted debunking dissemination. This implies that the spread of debunking content mirrors general information patterns (Reinecke and Trepte 2014; Soroka et al. 2019), also shaped by emotion. It supports prior findings (Chao et al. 2021, 2023) despite earlier inconsistencies (Pal et al. 2023). By revealing how debunking information embedded with emotional content is passively shared, this finding provides additional evidence supporting theories of emotional contagion (Chen et al. 2023) and affective information processing (Walla 2018). This can also be explained by viewing social media as “attentional scaffolds” (Voinea et al. 2024) and “affective scaffolds” (Figà-Talamanca 2024). As attentional scaffolds, platforms capture attention via intermittent rewards and emotional cues; as affective scaffolds, recommendation systems intervene in users’ emotional and cognitive states, influencing behaviour. These mechanisms help emotion-rich debunking content better engage users and spread. This perspective reveals how platforms shape users’ emotional and cognitive responses through design, transforming emotions into drivers of user behaviour, which helps us better understand how emotions facilitate the sharing of debunking information.

Second, this study evaluates the effects of discrete emotions—such as anger, disgust, fear, sadness, anticipation, and trust—on information sharing. While prior research examined emotions broadly, few studies have analysed how specific emotions shape sharing. The findings show that certain negative emotions (anger, sadness, disgust) and positive emotions (anticipation, trust) have a significant positive effect on information sharing. These results align with existing research on high-arousal emotions, such as anger, disgust, and anticipation, which have been shown to stimulate greater engagement (Ahmad and Laroche 2015; Ren and Hong 2019; Tellis et al.). However, trust, a low-arousal emotion, was also found to positively influence debunking information sharing. This effect can be attributed to the heightened need for reliable information during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, sadness unexpectedly played a positive role, a finding that aligns with Nabi et al. (2019), who also observed that sadness has a facilitative effect on sharing. These results suggest that when a rumour involves a particular subject, the decision to share information may not solely be driven by emotional arousal. Rather, it may involve more complex emotional processing, including additional cognitive factors. These findings offer new directions for future research and contribute to the further development of circumplex theories of emotion (Pool et al. 2016).

Third, this study assessed the moderating effect of the rumour subject’s reputation on the role of emotional valence. This contributes to growing research on contextual factors that shape the link between emotion and debunking information sharing. Our findings are consistent with prior research on image repair and apologies, which demonstrate that the persuasiveness of apology videos and users’ perceptions of sincerity is closely tied to the apologiser’s prior reputation (Lee et al. 2020; Sandlin and Gracyalny 2018; 2020). Furthermore, this study supports calls to consider different rumour contexts when examining debunking information sharing (Yu et al. 2022). Doing so deepens our understanding of the heterogeneous role of emotional valence and extends the application of ECT (Lee et al. 2020) to new scenarios.

Fourth, this study explored the moderating role of the rumour subject’s reputation in the effects of discrete emotions. Post hoc analyses revealed potential moderating effects of subject reputation on the emotions of fear, sadness, and trust. These findings suggest that users’ pre-existing attitudes toward a rumour subject’s reputation can influence how emotions embedded in debunking information shape their decision to share it. For example, consider the role of sadness. According to emotional contagion theory (Chen et al. 2023) and affective information processing models (Walla 2018), sadness in debunking information typically induces a similar emotional state in the user, triggering affective processing that may inhibit the sharing of such information. However, our findings suggest that when a rumour subject is involved, sadness may not merely evoke a mirrored emotional state but could also elicit other emotions, such as sympathy, depending on the user’s pre-existing perception of the subject’s reputation. This interplay between sadness and reputation shapes the user’s emotional processing and may ultimately influence their sharing behaviour. These findings provide a new perspective for future research and contribute to the ongoing development of emotional contagion theory (Chen et al. 2023) and affective information processing models (Walla 2018). By demonstrating that pre-existing perceptions of subject reputation can modulate the influence of discrete emotions on sharing behaviour, this study highlights the importance of considering reputational and other contextual factors in understanding how emotions drive the dissemination of debunking information.

Practical implications

This study offers insights for improving debunking dissemination and rumour management. First, understanding how emotional valence influences sharing is key to effectively countering rumours. Our findings show that both positive and negative sentiments significantly enhance sharing compared to neutral ones. Prior research suggests debunking content tends to show lower emotional expression than rumours (Chua and Banerjee 2018), which may be one of the factors limiting its dissemination scope. Based on our findings, framing social media as attentional and affective scaffolds (Figà-Talamanca 2024; Voinea et al. 2024) may help better leverage platform design to promote user engagement with debunking content. Platforms not only deliver information but also shape users’ emotional experiences, influencing engagement (Figà-Talamanca 2024; Voinea et al. 2024). Managers can use this operational feature to guide users’ emotions through emotionally framed debunking messages, encouraging sharing and dissemination.

Second, recognising the role of different discrete emotions allows for the tailoring of debunking information to specific contexts. Psychological studies have shown that distinct emotions exert unique influences on sharing behaviour (Nikolinakou and King 2018; Shiota et al. 2014b). This study revealed that high-arousal emotions such as anger, fear, disgust, and anticipation effectively promote sharing, while even low-arousal emotions like trust and sadness positively influence sharing behaviour. This suggests that arousal is not the sole determinant of how emotions influence debunking information sharing by eliciting emotions through the communication of positive emotions (such as anticipation—conveying a vision of a harmonious network environment, trust—emphasising the credibility of the rumour’s subject) or negative emotions (such as anger—expressing outrage at the negative consequences of the rumour, fear—highlighting the potential harm caused by the rumour, sadness—depicting the tragic circumstances of the rumour’s subject, disgust—condemning the behaviour of the rumour-monger), it is possible to effectively encourage users to share debunking information.

Third, the moderating role of the rumour subject’s reputation in the relationship between emotional valence and debunking information sharing supports the development of customised strategies. According to the findings of this study, the impact of emotional valence on the sharing of debunking information varied depending on the rumour subject’s reputation. Specifically, a positive reputation strengthened the effects of both positive and negative sentiments. Additionally, a negative reputation similarly amplified the role of negative sentiments but had no effect on positive sentiments. This suggests that when the subject’s reputation is positive, greater use of emotional expressions can promote the sharing of debunking information. Conversely, when the subject’s reputation is negative, using negative emotions is more effective in encouraging the sharing of debunking information. Therefore, organisations or public figures should focus on building and maintaining a positive reputation, as it enhances their effectiveness in refuting rumours through emotional debunking of information. In contrast, practitioners on social media platforms should tailor debunking information to include different emotions based on the rumour subject’s reputation, thereby facilitating the sharing and dissemination of debunking information.

Fourth, post hoc analyses revealed that the reputation of the rumoured subject had varying effects on the role of discrete emotions, further supporting the need for personalised debunking strategies. Overall, the heterogeneous role of discrete emotions, depending on the subject’s reputation, reflects a principle of punishing evil and promoting justice. Specifically, people are inclined to defend those with positive reputations. For subjects with positive reputations, the emotion of trust can inspire users to adopt more trusting beliefs, thus allowing the role of the trust emotion to be further strengthened. Additionally, the emotion of sadness also triggers users to be more sympathetic towards the subject because of the subject’s positive reputation, thus reinforcing the role of the emotion of sadness. In contrast, when the rumoured subject has a negative reputation, people are less likely to further promote sharing by envisioning a better future or emphasising their trust in the subject. At this point, sadness can have a greater impact by evoking sympathy. Therefore, when the subject has a positive reputation, the positive emotion of trust or the negative emotion of sadness should be used more often in the debunking information to promote sharing, whereas when the subject has a more negative reputation, sharing should be promoted through the expression of sadness.

Finally, these findings not only enhance our understanding of rumour debunking but also intersect with broader challenges related to protecting the infosphere, as highlighted by Mantello and Ho (2024). They underscore the need for a new cultural approach to counter misinformation. By incorporating the role of reputation in shaping emotional responses, this research highlights the importance of integrating emotional content and reputation management into communication strategies to enhance the effectiveness of debunking information. Furthermore, in light of the growing influence of adversarial AI in information warfare (Ho and Nguyen 2024), it is crucial for future debunking strategies to consider the ethical implications of emotional manipulation and the role of AI in disseminating or countering misinformation. Thus, the reputation of the rumoured subject, along with emotional expressions, must be considered in the design of more ethical and effective communication strategies.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. First, it is highly context- and culture-specific. This study was conducted within a Chinese cultural context and focused on sudden public health events, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, our conclusions may be limited to this specific scenario within an Eastern cultural framework during a public health crisis. Future research could explore these relationships in different cultural, social, and crisis contexts to further validate and generalise our findings. Second, this study focused exclusively on a single social media platform—Sina Weibo. While this platform is widely used in China, the applicability of these findings to other platforms, both within and outside of China, remains uncertain. Social media platforms often exhibit unique user dynamics, content formats, and engagement mechanisms. Future studies should examine whether the observed relationships hold across platforms with differing user bases, such as Twitter or Facebook. Third, we relied on a manually labelled measure of the rumour subject’s reputation. While this approach was tailored to the specific cultural and event context and validated using objective social media data (see Supplementary Appendix G), the manual nature of this process may raise concerns about reliability and scalability. Additionally, this method may not be fully generalisable. For domain-specific events, such as those in the entertainment or sports industries, individual differences may play a larger role in shaping perceptions of a subject’s reputation. Therefore, appropriate reputation measures should be used in different cultural and event contexts. Fourth, as this study was conducted within the specific context of COVID-19, this may be the primary reason for the absence of surprise and joy emotions in the debunking information. Future research could further evaluate the impact of surprise and joy on the sharing of debunking information in different rumour contexts. Finally, due to the lack of relevant literature, we did not explore the moderating effect of subject reputation on the influence of discrete emotions on debunking information sharing in sufficient depth. Future research should investigate and extend the findings of this study further, particularly focusing on the potential influence of contextual factors (e.g., rumour subject) on users’ affective information processing and subsequent behavioural decisions.

Conclusion

This study highlights the significant role of emotions in shaping the sharing behaviour of social media users regarding debunking information. Emotional expressions across varying valences were found to enhance the dissemination of debunking information. Additionally, discrete emotions with differing arousal levels demonstrated consistent positive impacts on sharing behaviour.

The reputation of the rumoured subject emerged as a critical factor influencing these dynamics. A positive reputation amplified the effects of diverse emotional valences, while a negative reputation intensified the impact of negative sentiments. Further analyses revealed that emotions such as fear, sadness, and trust may also be modulated by the subject’s reputation, highlighting the nuanced interplay between emotion and reputation in debunking information sharing.

These findings suggest that when developing communication strategies for debunking information, practitioners should carefully consider both the emotional expressions used and the reputation of the rumoured subject. Tailoring these elements can optimise the dissemination of debunking information and contribute to more effective rumour management practices.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

After pre-analysing the data from Sina Weibo, we found that out of all 5000 posts, only seven posts contained the emotion of joy, while two contained the emotion of surprise; therefore, we excluded the emotions of joy and surprise from our study.

Trust in IS research often refers to an individual’s belief in the reliability, honesty, and competence of another person or system (Gefen et al. 2003).

References

Ahmad SN, Laroche M (2015) How do expressed emotions affect the helpfulness of a product review? Evidence from reviews using latent semantic analysis. Int J Electron Commer 20(1):76–111

Alashoor T, Keil M, Smith HJ, McConnell AR (2022) Too tired and in too good of a mood to worry about privacy: explaining the privacy paradox through the lens of effort level in information processing. Inf Syst Res 34:1321–1814