Abstract

Anticipation is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the beliefs or desires of cognitive agents with respect to the world surrounding them, and that can influence the behaviour and decisions of such agents. This paper addresses the status and the role of anticipation in the shaping of language structures. We sketch a preliminary theoretical framework for anticipation in language and linguistic research. Anticipation is presented as a neural mechanism that projects as a principle shaping cognitive processes. Anticipation is then shown to permeate a three-level architecture also shaping language use: the underlying cognitive structure, the middle-level information structure, and the surface discourse structure. It is suggested that anticipation in language may explicitly emerge as a relation between the informational (i.e. propositional and presuppositional) content of clauses and sentences. It is then suggested that anticipation plays a role across different language structures (e.g. subject–predicate and topic-comment structures; sentence types and multi-clausal discourses) and via different categories (e.g. Discourse Markers such as sentential adverbs, discourse connectives). It is proposed that this framework can capture several well-studied but recalcitrant linguistic phenomena in a unified manner by offering a model of how anticipations shape language use. The paper introduces preliminary evidence in support of these claims. First, clauses can minimally introduce anticipations as agents’ expectations about sentences and their content. Second, discourse structures can modulate anticipations without the explicit presence of categories expressing these anticipations (e.g. Discourse Markers). When present, however, these categories must match the anticipation types that relations between sentences express. It is thus suggested that anticipation patterns can emerge in language as conceptual/rhetorical relations in discourse. The paper concludes by discussing the consequences of our proposal for linguistic theories that address the topic of anticipation in language and cognition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Everything is achieved if it is anticipated;

without anticipation, it will fall.

— From Book of Rites: Doctrine of the Mean

Anticipation is a key psychological phenomenon and research topic in psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, sociology, economics, and other fields (Pezzulo et al., 2007; Clark, 2015; Hohwy, 2013; Akhmetzyanova, 2016; Poli, 2017). Due to the close relationship between language and psychology, linguists have also used the concept of anticipation in linguistic research. For instance, Lü (1982/1942–1944: 340) explained transitional sentences using notions such as “anticipation” and “deviation from anticipation”. Since Heine et al. (1991), research on anticipation has gradually become a key topic in linguistics. Some examples across linguistic sub-disciplines are as follows.

In phonology, it is generally acknowledged that prosodic and intonation patterns offer cues to sentences and their content (e.g. raising pitch in interrogative sentences: Pierrehumbert, 2016; Pierrehumbert and Hirschberg, 1990). Dynamic (formal) semantics theories suggest that agents interpret the meaning of “new” sentences against the meaning of “old” sentences, forming the context of discourse (e.g. Geurt, Beaver and Maier, 2024). Different syntactic frameworks propose that several grammatical structures provide syntactic prominence to semantically salient content (e.g. cleft structures, question-answer pairs, topic-comment structures; Miyagawa, 2022; Narrog and Heine, 2018). Language- and sentence-processing theories invariably assume that expectations about categories and the meaning of words guide how agents interpret the flow of conversation (Huettig and Janse, 2016; Vogelzang et al., 2017). Thus, it is generally acknowledged that the production and comprehension of language hinges on agents’ “expectations” or anticipations about language structure and use in discourse (Bock, 1996; Ferreira, 2010).

In this paper, we pursue a perhaps modest focus that, however, should provide a precise novel argument for anticipation as a guiding principle in linguistic research. We focus on the use of Discourse Markers in a variety of linguistic structure types, beginning from English examples (1)–(2) in Table 1:

Anticipation patterns in language can emerge at the level of clauses as minimal predicative structures; mono-clausal and multi-clausal sentences can also convey this information (cf. Heine et al., 1991). In (1), the first clause (i.e. We made a promise) reports a claim that some speakers/agents made a promise; the second clause (i.e. and I kept it) confirms this fact, with the third clause offering a reason for pursuing this promise (i.e. because it’s gonna save lives). In (2), the clause but she stayed away clarifies that the expectations of individuals/agents about “Adele” did not materialise (i.e. the clause Everybody was hoping that Adele would come).

Via (1)–(2), we also introduce “Discourse Markers” such as so, but and suddenly (e.g. Heine et al., 2021; Traugott, 2022). Discourse Markers may belong to different syntactic categories (e.g. clausal/sentential connectives, adverbials), but share a function as categories connecting other grammatical structures (e.g. phrases, clauses, sentences) and introducing semantic relations among these structures (e.g. coordination for and, causal relation for because). Thus, (1)–(2) offer preliminary, minimal evidence that language includes structures and categories expressing agents’ expectations about information in discourse (i.e. “anticipations”).

Several studies have analysed anticipation patterns and their sub-types, but mostly have focused on single Discourse Markers (e.g. Yulin, 2008; Zhu et al. 2013; Lu 2017; Lu and Zhu 2019; Aikhenvald, 2012; Delancey, 2001; López, 2017; Chen and Jiang, 2019; Qiang, 2020). These studies, however, do not fully address how anticipation patterns emerge across grammatical/discourse structures and which categories and structures can jointly realise these patterns. They do not explore the role of sentence types and predicative structures in implicitly defining anticipation patterns that Discourse Markers seem to explicitly express. Furthermore, these studies do not address how these linguistic patterns instantiate anticipation as a cognitive phenomenon. Agents can use sentences such as (1)–(2) to express their non-linguistic expectations regarding real-life events in context (e.g. Poli, 2019). However, previous studies do not fully explore how such non-linguistic expectations (i.e. anticipations) find expression in language use.

The goal of this paper is therefore to introduce a three-tier cognitive architecture in which anticipation plays a key role, in cooperation with the mechanisms that regulate language across different languages (e.g. sentence-building, information structure modulation, cohesion principles in discourse). We suggest that anticipation in language emerges in the form of relations among the informational and interactional content of clauses, sentences and discourses. We then suggest that these relations may be explicitly expressed via Discourse Markers (cf. (1)–(2)). From these suggestions, we sketch two predictions regarding how anticipation can act as a guiding principle in language structures and their use. The paper reaches this specific goal via these sub-goals. In the section ‘Anticipation: definitions and role in cognition’, we offer an overview of anticipation as a notion defining our proposed model of cognitive architecture. In sections ‘Anticipation in cognitive structure systems’, ‘Anticipation and information structure: presuppositions and propositions’, and ‘Anticipation and discourse structure’, we analyse how anticipation emerges at cognitive, information and discourse structure levels. In the section ‘Discussion and conclusions’, we discuss these results and conclude.

Anticipation: definitions and role in cognition

Research investigating anticipation spans across fields such as philosophy, psychology, and linguistics. Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, proposed that all knowledge that can shape cognition and determine empirical knowledge could be called a kind of preconception. This is the meaning of Epicurus’ term “prolepsis” (Kant, 2002: 146–147), and the historical precursor to the modern concept of anticipation. In psychology, Searle (2007: 4) defines anticipation as “making advance estimates of the future” (cf. also Akhmetzyanova, 2016; Pezzulo et al., 2007). Rang (2021: 3) proposes that anticipation is prior knowledge formed because of experiences concerning forthcoming environmental stimuli or events (cf. van Dijk & Rietveld, 2021; Nadin Mihai, 2016). Yang (2021: 347) suggests that anticipation is a fusion of individual experiences and memorised past events, which can support decision-making and judgement for future events (cf. Sutton, 2008).

In linguistics, Narrog and Heine (2018) consider anticipation as an abstract principle within human cognition connected to social conventions, the knowledge states of the agents in speech acts and contexts (cf. also Dahl, 2001; Heine, 1997: Ch. 1; Heine et al., 1991; Heine & Kuteva, 2007: Ch. 1). Lu, (2017: 40) defines anticipation as the prior understanding of discourse information by agents, including foreknowledge and prediction, which may or may not correspond to fact. Poli (2017: 260) proposes that anticipation is future-oriented information acting in the present, affecting language and other forms of cognition. By combining these different definitions, we propose the following definitions in Table 2:

The definitions in Table 2 suggest that anticipation is the cognitive guide for subjective behaviour and decisions (Gregory, 2021; Poli, 2017; Searle, 1983). Pro-anticipation thus holds when an agent’s anticipation matches facts, while counter-anticipation holds when an agent’s anticipation diverges from facts (Zhu et al. 2013; Lu 2017; Lu & Zhu 2019). Anticipation as a psychological phenomenon, therefore, involves anticipating agents, anticipated events, the content and transmission mode(s) of anticipation, and the interaction of agents’ behaviour(s) with events in context (Poli, 2019; van Dijk & Rietveld, 2021). Six aspects define anticipation as a cognitive phenomenon, as we summarise in Table 3:

The sixth and last property, implicitness/explicitness, allows us to illustrate how anticipation can emerge in language use. Consider (3)–(4) in Table 4:

An agent who uses (3) to present future plans for blog posts informs readers that the agent expects to return to a given topic. The use of the future tense auxiliary form will implicitly signal that the agent considers this event reasonably certain (e.g. López, 2017; Roberts, 2012). An agent who uses (4) to announce future plans for “dinner-tasting” events expresses explicit emphasis on this plan via the adverbial definitely, since adverbials are another category that can function as Discourse Markers (e.g. Traugott, 2022: Ch. 2). In (3)–(4), agents introduce their expectations about future plans as pro-anticipations (i.e. positive expectations); while (3) introduces an implicit pro-anticipation, (4) introduces an explicit pro-anticipation.

Anticipation, as argued in philosophy and cognitive psychology, seems to permeate cognitive processes (Goldstein, 2018). In linguistics, theories of Information Structure (e.g. Lambrecht, 1994; Kadmon, 2001; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004; Zimmermann and Féry, 2010; Roberts, 2012) suggest that the interplay of phonology and syntax/discourse structure shapes how speakers form “expectations” about information structure (i.e. our anticipations). Cognitive linguistics models (e.g. Croft and Cruse, 2004; Evans and Greene, 2006; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004; Langacker, 2008; Evans, 2019) suggest that cognitive processes and their principles guide language use at the level of information structure and also surface in Discourse Structure. They thus suggest that categories such as Discourse Markers, among many others, can express “expectations” in language.

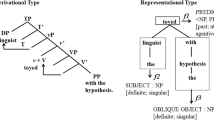

Works focusing on discourse grammar suggest that one can distinguish between discourse grammar, the domain of propositional content, and “thetical” grammar, the domain of interactional (i.e. speech act-based) content (e.g. Heine, 2023; Heine et al., 2017; Narrog and Heine, 2018; Heine & Kuteva, 2007; Kaltenböck et al., 2011). For these works, anticipation and grammatical markers belong to thetical grammar. Nevertheless, they also assume that anticipations operate on discourse structures. Crucially, all these models converge in assuming that language structures must include anticipation as a principle guiding language use. We present the architecture of language that underpins these proposals via Fig. 1:

Upward arrows indicate how anticipation projects from cognition to language structures; downward arrows indicate how these structures piggyback on cognitive principles for the production and interpretation of their structures (e.g. the cognitive context, to be defined in section ‘Anticipation and information structure: presuppositions and propositions’; anticipation). The horizontal bar encapsulating the “Anticipation” principle and its types indicates that this is a general cognitive principle; we provide evidence for its neural substrates in Section Anticipation in Cognitive Structure Systems. The horizontal bars encapsulating key Information Structure types (e.g. comment-focus) and Discourse Structure types (e.g. subject–predicate) indicate that these are general linguistic structures which should thus include anticipation as one of their guiding principles.

At a non-linguistic level, cognitive structures such as perception, attention, general knowledge, and reasoning generate anticipation(s)about events. For instance, agents can pay attention to an event of a football player dribbling a defender and preparing to strike the ball. The agents can make anticipations about the outcome of this action (e.g. a goal) by combining perceptual information (e.g. the striker’s direction, the defenders’ positions), general knowledge (e.g. the likeliness of a shot being successful) and reasoning (e.g. other factors playing a role). If agents observe events in the present, they can ultimately make guesses about events in the future, even though these guesses may turn out to be fallacious.

Anticipation can thus guide language use via information shaping agents’ intentions, beliefs, and concepts. For instance, agents who may use (1)–(4) in discourse can express their intentions about saving lives in some future (e.g. (1)), hoping that a certain Adele would come (cf. (2)), returning to blog posts (cf. (3)), and returning to try dinner (cf. (4)). A unifying trait about these multi-clausal sentences is that the linguistic expression of anticipation implicitly passes through the content they express. Discourse Markers, in this regard, seem instead to explicitly state the implicit anticipations that sentences define via their content. Anticipation, hence, seems to underpin different types of cognitive processes, including language (e.g. Goldstein, 2018: 107). If the cognitive architecture in Fig. 1 aptly models these principles, then two general and falsifiable predictions emerge about anticipation and language use, as we illustrate in Table 5:

However, anticipation apparently takes different forms at each level of this architecture. Therefore, our research questions are still in need of answers. To these answers, we turn.

Anticipation in cognitive structure systems

Traditional cognitive science views the brain as a passive, stimulus-driven device that receives input from the senses and assembles it into coherent experiences (Piccinini, 2015; Pylyshyn, 1984; Rescorla, 2020). However, recent research has found that the brain actively and constantly predicts relevant inputs (Clark, 2015: 58). Therefore, although anticipation is not a new concept, psychology and cognitive neuroscience have paid renewed attention to it in the past decade. Contemporary cognitive science regards anticipation as a bottom-up mechanism driven by the subject’s expectations and highly sensitive to uncertainty (Clark, 2015: VI). It can be said that in language and other cognitive systems, anticipation is a principle that affects mental processes in a hardly detectable and yet pervasive manner. We motivate this theoretical claim in the remainder of this section.

There are two key theories regarding the brain’s processing of anticipations: the Free Energy Theory Model and Predictive Processing Model. The concept of “Free Energy” originates from physics and measures the energy that a system can output in a specific thermodynamic process (Britannica, 2022). Within cognitive science, it refers to the difference between how the world is mentally represented and how the world actually works (Friston, 2009, 2010, 2013; Friston et al., 2010; Torres-Martínez, 2023a, b). The more accurate, error-free the match is, the lower the amount of information-based free energy is required. The Free Energy Theory suggests that minimising prediction errors during its interaction with the environment reflects a core task of the system.

Clark (2013a, b) (cf. also Clark 2015, Clark 2018) proposes instead the Predictive Processing Model. This model suggests that the brain is a predictive engine; before stimuli become sensory input, the brain has already formed hypotheses regarding their most likely form and meaning. The brain only needs to process the deviations between actual perception and anticipations, i.e. anticipation errors. At the same time, the brain uses anticipation errors to adjust and improve the quality of subsequent anticipations. Incoming stimuli from bottom-up perception are processed within a set of prior beliefs or assumptions that come from top-down, downward propagating cognitive processes (e.g. memory). Mismatches or errors between signals and anticipations propagate upward to cognitive systems (e.g. language, memory) to adjust subsequent anticipations. This cycle continues as long as the brain processes information.

The Free Energy Theory and Predictive Processing Model find support in several psychological experiments with a neurophysiological basis. In order to merge models into one theoretical apparatus, Barrett and Simmons (2015) proposed the Embodied Predictive Interception Coding (EPIC) model through numerous experiments. This model focuses on representing the hierarchical organisation of the neurophysiological systems that support predictive processing. It also models the transmission and processing of information and prediction errors within the system, i.e. “predictive/anticipatory coding”. Figure 2 below shows how this coding occurs:

Intracortical architecture and intercortical connectivity for predictive (i.e. anticipatory) coding (figure reproduced: thanks to Open Access license from Barrett and Simmons (2015: 27).

According to the EPIC model and its anticipatory coding illustrated in Fig. 2, the brain cortex contains both anticipation neurons and anticipation error neurons. Anticipation neurons in the deep layers of the granular cortex drive active inferences by sending sensory anticipations projecting to the upper layers of the granular non-uniform and granular cortex (green lines). Anticipation error neurons in the upper layers of the granular cortex compute the difference between anticipated and received sensory signals and send anticipation error signals, which are then projected back to the deep layers of the granular cortex (red lines). Pyramidal cells dynamically adjust the gain of anticipations and anticipation errors. Based on the relative confidence in downward anticipations or the reliability of incoming sensory signals, the weights of these signals can increase or decrease.

The EPIC Model thus provides strong support for the central role of anticipation within cognitive systems. Clark (2015: 58) furthermore points out that the calculation of prediction errors occupies an important role in the processing of information. Individuals generally pay attention to salient stimuli in dense perceptual signals that have “news value”. For instance, agents who play video games may focus only on visual information that is vital to their success (e.g. attacks against their characters). They may thus ignore all other visual information (e.g. luscious backgrounds and detailed visuals). Under this view, anticipation becomes a neural mechanism that projects at a cognitive level. In concise terms, the brain processes past and present perceptual information about the world to form anticipations about future information. The mind processes this information to form more abstract representations about the world, thus forming anticipations about the content of these representations and their relations.

Once anticipations are established, new anticipations are formed and evaluated as pro- or counter-anticipations. Pro-anticipations are maximised and counter-anticipations are minimised, as the brain tries to maintain a model of the environment as accurate as possible. We show this recursive, dynamic cycle in (5), Table 6:

Several works also offer evidence that events experienced in the past may serve as the cornerstone for building anticipations (e.g. Buckner, 2010; Grabenhorst et al., 2019; Monfort et al., 2015). Other works propose that memory, imagination, and anticipation share common brain mechanisms (e.g. Carroll, 2020; Mullally and Maguire, 2014; Spens and Burgess, 2024). Some works suggest that the key purpose of memory is not to recall the past but to predict the future (e.g. Josselyn and Tonegawa, 2020; Schacter, 2012; Vecchi and Gatti, 2020). Memory and computation of anticipations thus seem to constrain our understanding of the environment at a cognitive level (e.g. Cravo et al., 2017; Galli, Bauch and Gruber, 2011). From what we have learnt in the past, we make anticipations about the environment in the present and in the future. Language, as one amongst many cognitive systems, should also follow these basic principles.

Evidence that anticipation projects at a linguistic level as a guiding principle is perhaps abundant, though one must frame this claim carefully. Here, we only discuss some key illustrative results to maintain our discussion concise. In several EEG studies, the N400 and P600 responses show that when the brain encounters counter-anticipations (i.e. unexpected information), it generates additional neural responses to accommodate this information (e.g. Goldstein, 2018: 454; Yang, 2021: 356; Zhu et al., 2019). Sentence processing studies show that anticipating incoming linguistic chunks helps agents to reduce the influence of noise, ambiguity and other processing challenges (e.g. Kleinschmidt and Jaeger, 2015; McRae et al., 2005; Pickering & Garrod, 2007). When agents process grammatical structures, they form anticipations upon interpreting words and their meaning (e.g. Berkum et al., 2005; Freunberger & Roehm, 2016; Kuperberg and Jaeger, 2016). Case in point, Rothermich and Kotz (2013) found that when listening to speech, listeners develop anticipations about semantic content (i.e. “what” words and meanings to anticipate) and about prosodic timing (i.e. “when” to anticipate words; Breen, 2014 and references therein).

Overall, the dynamic understanding of language units in real-time discourse follows principles that seem to build on anticipation as their basic neural mechanism. Several linguistic works have built on these insights to claim that anticipation shapes how we develop a cognitive model of context in which we interpret language. Our minds constantly form anticipations about the subjective and objective world, and all these anticipations together form what is at times defined as an agent’s “world of anticipation” or “cognitive context” (Heine et al., 1991, Heine, 1997: Ch. 1; Narrog and Heine, 2018). Each agent’s world of anticipation is unique, with overlapping parts among different agents’ worlds referred to as shared anticipations, while the different parts belong to individual anticipations. From this world of anticipation, agents can use contextual, situational, socio-cultural, and cognitive information to establish a context of discourse interpretation (Assimakopoulos, 2017; Gardenförs, 2014: Ch. 2; Jiang, 2012: 86).

The cognitive context shapes how agents can evaluate anticipations mediated via the linguistic units (e.g. clauses, sentences) that express them. An agent who produces a sentence like (4), for instance, asserts a plan for an undefined future (cf. I will come back and sometime) regarding an action that the agent intends to perform (i.e. try their dinner). A Discourse Marker (i.e. definitely) also underlines the agent’s (pro-)anticipation that this action will happen. Another who successfully interprets (4), then, discovers that the other agent may have present complex plans or anticipations regarding future actions. The Free Energy and the EPIC models suggest that our neural architecture also works in a manner that expectations, plans, decisions and future events (that is, anticipations) can be explicitly expressed at a linguistic level. Agents understand language in real-time with the help of anticipation mechanisms, and process linguistic content via relations amongst this content that seem to reflect these mechanisms.

In their more recent formulation of Relevance Theory, Sperber and Wilson (1995) also suggest that agents form expectations in discourse (i.e. our anticipations). This is because the cognitive context receives information from five memory sources: recall, perception, encyclopaedic knowledge, deductive reasoning, and language decoding. Recall and perception associate sensory stimuli with conceptual categories: they allow agents to form anticipations (e.g. an agent seeing a pothole on the ground: Carroll, 2020). Encyclopaedic knowledge allows agents to form anticipations about sensory stimuli based on agents’ previous knowledge (e.g. an agent recognising a pothole as a danger: Gardenförs, 2014: Ch. 3). Deductive reasoning allows agents to make inferences about anticipations that may or may not match facts (e.g. agents avoiding a pothole to avoid danger; Lu, 2017: 40–42). Language decoding allows agents to match these assumptions with linguistic information in context (e.g. agents reading a message about the pothole and the danger it represents; Assimakopoulos, 2017).

This view of how anticipation projects from neural mechanism to cognitive principle corresponds to (part of) Prediction #1 from Table 5. Another part of prediction #1 can be stated as follows. If memory sources shape how languages express anticipations, then languages may express the type of these sources explicitly via grammatical and discourse structures. We believe that (6)–(10) in Table 7 offer such preliminary evidence:

An agent uttering (6) recalls some information (cf. the verbs I recall, I remember) about another agent’s passive status (i.e. my victim), and introduces anticipations about the second agent’s behaviour. An agent uttering (7) describes an individual called “Maggot” seeing some scenario in an unexpected manner (cf. the adverb suddenly): Maggot may see something not following his anticipations. An agent uttering (8) anticipates that snow does not fall in April. The adverb actually suggests that this anticipation based on general knowledge is violated, and the second sentence (i.e. It’s unbelievable) confirms this counter-anticipation. An agent uttering (9) infers that certain wolves lack knowledge of humans; the agent infers and thus anticipates that the wolves will not attack (cf. the connective so, the adverbial at all). In (10), the first sentence introduces a group of individuals in a good situation. The second sentence clarifies that they are not happy, contrary to their (and the agent’s) anticipations (cf. the connective but).

Overall, (6)–(10) suggest that memory can shape the cognitive context in which language is used, and the anticipation types that language can express, in line with prediction #1. Anticipation types at a linguistic level can therefore be defined as relations between agents’ expectations about previous, present and expected events, and the linguistic units (e.g. words, clauses, sentences, discourse) that express these expectations. There certainly are a wealth of works showing that linguistic anticipation types seem relevant for linguistic analysis (e.g. Heine et al., 1991; Heine et al., 2021; Traugott, 2022). As mentioned in the introduction, however, these works tend to propose a narrow focus on single Discourse Markers (e.g. well). Hence, they leave aside a discussion of exactly how this or other grammatical/discourse categories and structures relate to anticipation as a neural and cognitive phenomenon.

Overall, in this section, we have outlined a connection between anticipation as a neural mechanism and its projection in cognitive structure systems: chiefly the formation of cognitive contexts. Thus, we have offered preliminary evidence that anticipation is a guiding principle for the “bottom layer” in Fig. 1. We have then suggested that anticipation projects as a mechanism guiding the processing of language units and the contribution of language units, from words to discourses: it projects to the “middle” and “top” layers in Fig. 1. We provide a fuller proof that this suggestion and thus that the predictions of our model are also accurate in the next two sections.

Anticipation and information structure: presuppositions and propositions

Language and verbal communication represent the main channels of communication for humans (Bara, 2010: 12; Gardenförs, 2014; Levinson, 2024; Liu, 2012: 91; Sperber and Wilson, 1995). As a cognitive faculty, one could thus expect that language phenomena occur according to the guiding principle of anticipation. Marie, Vandenbergen, and Aijmer (2007) point out that “anticipation” and “deviations from expectations”, our pro- and counter-anticipation, form the core components of human communication. In order to explain this position, we fixate on some basic concepts to explain how anticipations emerge in language.

When agents communicate via language, they do so via speech communication acts (e.g. Gardenförs, 2014; Heine et al., 2021; Liu, 2012: 191; Sperber and Wilson, 1995; Traugott, 2022; Włodarczyk, 2013; Yu, 2022: 69; Zhou, 2016: 3). We can divide a speech communication act into four parts and suggest how anticipation shapes these parts via Table 8:

In language, contextual information can shape how agents operate when they produce their speech acts. Agents may implicitly or explicitly state this information (cf. (3)–(4)) and use it convey their beliefs and desires. However, this contextual information seems to hinge on how sentences can describe events and relations between these events, and how agents relate to these descriptions. In semantics and pragmatics, it is standardly assumed that these complex descriptions correspond to propositions and their implicit counterparts, presuppositions. Anticipations as linguistic patterns, under this view, can be analysed as relations amongst these information units. We provide definitions and supporting references in Table 9:

One illustrative example is as follows. In (10) from Table 7, the first sentence introduces a proposition as a description of an event in which some individuals are doing just fine (i.e. they are doing just fine). The second sentence introduces another proposition clarifying that these individuals have a feeling of unhappiness about this event (i.e. but they are not happy about that). Thus, the first sentence expresses a proposition as a complex, structured type of information unit. The first sentence also introduces a presupposition: people who do fine should be happy, in theory. The second sentence then introduces another proposition as a mental state about the first proposition. The Discourse Marker but thus introduces a relation between the pre- and propositions of one sentence, and the pre- and propositions of a subsequent sentence. This relation states that the second set of information units does not match the first set of information units: it is a counter-anticipation relation.

Theories of information structure suggest that in discourse, agents can contribute sentences during discourse turns with the purpose of introducing information units and shaping the context (Asher and Lascarides 2003; Lambrecht, 1994: 335; Zimmermann & Féry 2010). Linguistic Information structure theories suggest that syntactic structures underpinning sentences can determine how this content can be structured via various types of semantic structures, e.g. subject–predicate, topic-comment, and presupposition-focus structures (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004; Lambrecht, 1994; Levinson, 2024; Zimmermann & Féry, 2010). Each of these structures can introduce information about referents with different functions in discourse (e.g. subject, topic or focus of a sentence). Predicates and comments can ascribe information to these referents and the events in which they participate; focus structures can state that some event holds in context, rather than other similar events (cf. Roberts, 2012; Schwarzschild, 2020; Narrog and Heine, 2018: Ch. 1; Traugott, 2022).

Our architecture crucially postulates that these linguistic structures build on the (cognitive) context and of anticipation about events forming these contexts. The architecture thus predicts that agents may use different information structures to convey anticipations in language by taking the context as a starting point, cf. (11)–(13) in Table 10:

In (11), the complex NP any help…numbers introduces a complex referent acting as the subject, and the remainder of the sentence predicates a property of this referent. A first agent is addressing a second agent, and stating that the second agent’s help/support (i.e. the subject of the sentence) will be helpful (i.e. the predicate ascribed to this subject). In (12), a first agent states that the event of customers finding another agent’s shop via Tumblr is unlikely. Thus, this “shop-finding” event acts as a topic on which the first agent offers a comment on its feasibility. In (13), a first agent requires that a second agent use a car rather than a bike to pick the first agent up. We mark the NPs introducing these alternatives via italics: a car receives the main (prosodic) focus, and a bike the contrastive focus (Roberts, 2012; Schwarzschild, 2020).

Consider now the role of discourse markers and syntactic structures. In (11), the adverbial Discourse Marker certainly introduces an anticipation about the events being described. The first agent presupposes rather than asserts that the help that a second agent can offer is helpful, and asserts that this is certain. In (12), the cleft sentence as a type of (English) topic-comment structure introduces a relation between a proposition and the agent’s (presupposed) anticipation that the proposition describes an unlikely shop-finding event. In (13), the contrastive focus pattern highlights that the speaker/agent presupposes an event to happen, and requires a second agent to avoid this outcome. The counter-anticipation arises from the presupposed event (i.e. being picked up with a bike) being against the agent’s anticipations.

Building on these examples, we suggest that these information structures can implicitly express anticipations via their “structural packaging” of information units. Agents can process information about the context and form expectations and desires about events; they therefore compute anticipations. In spoken language, the packaging of this information must emerge via relational structures that map events and their participants onto propositions and presuppositions (i.e. information units). Thus, the bottom-up connection between cognitive and information structures is shaped by anticipations, as per predictions of our architecture. Our prediction #1, that anticipations shape language structures and their content, including categories expressing anticipation, finds some further preliminary support.

The top-down connection between information structure and cognitive structure, our prediction #2, can now be confirmed as follows. When agents use Discourse Markers, they can express anticipations explicitly, but Markers must match anticipations via their semantic content (cf. Asher and Lascarides, 2003; Zimmermann and Féry, 2010; Narrog and Heine, 2018). Failure to accommodate presuppositions results in incomprehensible communication: agents do not understand each other (Beaver et al., 2024). We offer some examples involving subject–predicate structures in (14)–(19) to illustrate this point (Table 11):

In (14), the mention of an individual who is eighty years old introduces the presupposition that this individual should not appear younger than this age. The second clause in (14) contrasts this presupposition with the assertion that this individual appears close to sixty. The adversative conjunction/ Discourse Marker but confirms that presupposition and assertion stand in a counter-anticipation relation. In (15), the coordinating conjunction/Discourse Marker and is used in the same underlying sentence for (14), and thus does not match the contrastive relation between presupposition and proposition. Hence, the sentence seems uninterpretable, i.e. it conveys paradoxical information.

A similar pattern occurs in (16)–(17): the first clause presupposes that the reason why an individual cannot manage complex tasks or projects, a reason/proposition clarified in the second clause. In (16), because matches the type of causal relation and pro-anticipation that connects the two clauses. In (17), the second clause introduces a proposition that introduces a paradoxical explanation. An individual lacking opportune skills can nevertheless perform certain tasks. Since because defines a pro-anticipation as a non-paradoxical relation between propositions and presuppositions, it cannot occur in this sentence.

In (18)–(19), the first clause he does not work much states that some individual’s workload is not conspicuous. The second clause introduced by the causal Discourse Marker because in (18) introduces the presupposition behind this assertion: the individual has few work duties. In (19), the second clause introduces the opposite presupposition and, therefore, creates an uninterpretable sentence. Thus, (18)–(19) suggest that the linear order of clauses and the presuppositions and propositions they introduce is not crucial. What matters is that explicit Discourse Markers match the anticipations that these units introduce as relations between these information units, or the corresponding sentences will be uninterpretable otherwise.

Overall, we now have evidence that cognitive structure defines the context that agents use to interpret and anticipate in language (bottom-up predictions). We also have evidence that mismatches in the use of Discourse Markers in the expression of anticipations cause presupposition failures as forms of “anticipation misuse” (top-down predictions). Our predictions #1 and #2 find some preliminary evidence supporting their validity. The aspect we address next is how anticipations can shape discourse structures.

Anticipation and discourse structure

In this section, we explore how linguistic anticipation emerges at the discourse level by analysing sentence types and their constituting clauses, and then discourses and their constituting sentences. We take the minority view that there is a structural continuity between sentential and discourse syntax and semantics (e.g. Asher and Lascarides, 2003; Cinque, 2020: Ch. 7; Jimenéz-Fernández, 2024; Miyagawa, 2022; Li, 2022). We also suggest that discourse and thetical grammars interact systematically (e.g. Heine et al., 2021). Briefly, the first grammar builds clauses, sentence types and the presuppositions/propositions they convey. The second grammar connects these units via anticipations. We show in this section that the realisation of anticipations at these language levels justifies these assumptions, thus offering further evidence in support of predictions #1 and #2.

Anticipation at the sentential level: sentence types and the shaping of discourse

We have suggested that semantic structures can introduce presuppositions and propositions at the minimal level of clauses (cf. Kadmon, 2001; Lambrecht, 1994; Xing, 1992, 1995, 2001; Geurts, Beaver and Maier, 2024). Sentences types can include one or more clauses and introduce different anticipation types as relations between the propositions/presuppositions that sentences introduce (Heine et al., 2021; Traugott, 2022: Ch. 2; Wang, 1985: 35). For single clauses, Anticipations thus can be minimally realised as relations between a mono-clausal sentence and its cognitive context, cf. (20)–(21) in Table 12:

In (20), the speaker-oriented adverb/Discourse Marker finally establishes that the agent/speaker was anticipating/presupposing a system that would work for him. In (21), as the Discourse Marker nevertheless suggests that the agent/speaker left a first venue even if this agent probably wished to remain, some event that happens defines a counter-anticipation. Thus, anticipations can minimally capture a relation between the cognitive context and the informational content (propositions, presuppositions) that a clause introduces in discourse. Discourse Markers (e.g. finally, nevertheless) can explicitly mark pro- and counter-anticipation relations arising in these contexts. These data thus offer evidence supporting prediction #2, as they suggest that sentences can add information to cognitive contexts, thus acting as minimal speech acts. They also support prediction #1, as they suggest that agents can use the cognitive context as “background” information on which they can form their anticipations.

Let us turn to multi-clausal sentences and the sentence types they form. Traditionally, four types of sentences are distinguished: declarative sentences, interrogative sentences, imperative sentences, and exclamative sentences (e.g. Lambrecht, 1994; Miyagawa, 2022). Wu (2015), taking into account the psychological states of knowledge, emotion, and intention, as well as communication modes, categorises sentences into eight types: declaratives, interrogatives, imperatives, commissives, expressives, responsives and announcements (cf. also Heine et al., 2021). We discuss these sentence types in order to show how these types can introduce anticipations in discourse in virtue of their structural properties.

Declarative sentences are standardly analysed as statements about events (e.g. Beaver et al., 2024). Speakers/agents’ intentions in using declarative sentences usually consist of informing hearers/agents about these events, so that the hearers may possibly acknowledge them. Pro- and counter-anticipations in declarative sentences can be expressed via single clauses (cf. (20)–(21)) but also via multiple clauses and sentences. When multiple sentences are combined to form minimal discourses, earlier sentences introduce anticipations for the evaluation of subsequent sentences (cf. (22)–(23) in Table 13:

In (22), the first mono-clausal sentence (i.e. I…neighbours) introduces the proposition that the agent was nice. This proposition entails that the event described in the second sentence is a temporally distant consequence of the first event, as the temporal (prepositional) phrase after ten years explicitly remarks. In (23), the adverb unexpectedly marks a counter-anticipation: a friend of the speaker/agent, “Lisa”, was not supposed to pass away. Declarative sentences and discourses can thus introduce propositional/presuppositional content and their relations, i.e. pro- or counter-anticipations. Discourse markers can then explicitly express anticipations explicitly, thus signalling agents’ attitudes about the described events. Such speech acts, we believe, lend further support to our prediction #2.

Let us move to interrogatives and their subtypes. Sub-types of interrogative sentences are based on the type of questions they pose: rhetorical questions, polar (yes/no) questions, and wh-questions (Lü, 1982; Siemund, 2013). We discuss these types via (24)–(26), in Table 14:

In (24), the anchoring clause aren’t you? Introduces the anticipation that the answer must be positive: the agent anticipates that another agent will admit their guilty acts. In (24a), the second agent categorically denies this anticipation and forms a counter-anticipation via a negative answer; in (24b), the second agent confirms this pro-anticipation via a positive answer. In (25), the question is about a person’s location: though the person’s location is not known, the first agent anticipates that another agent knows the missing person. The answer in (25a) confirms this latter anticipation, but the answering agent also admits to not knowing the location of the missing person. In (25b), the answering agent introduces a counter-anticipation by asking who is the person under discussion, thus rejecting the anticipation in the first answer.

In (26), the interrogative pronoun where presupposes that the answer is about a specific location. Thus, the agent/speaker anticipates an answer matching this type of content. A pro-anticipation is formed via (26a) (i.e. in my car), and a counter-anticipation is formed via (26b) (i.e. Tomorrow). In English, presuppositions can be introduced via morphologically complex pronouns (here, wh-ere for locations) and anaphors that establish constraints on the form and meaning of further categories in discourse (cf. Delancey, 2001; López, 2017). For interrogative sentence types, wh-words presuppose answers of a certain semantic type; in using these words, agents anticipate answers of a matching type. We thus believe that interrogatives confirm prediction #2: the use of certain linguistic structures and their content introduces anticipation about further sentences (or parts thereof) in discourse.

Imperative sentences are intentional requests made by the agent/speaker that an agent/hearer perform a certain action, while commissive sentences are intentional assurances made by agents about actions (cf. Zhu and Wu, 2008; Aloni, 2005; Hamblin, 1987; Traugott, 2022; Heine et al., 2021). Agents using imperative sentences anticipate that other agents will perform those actions; agents using commissive sentences anticipate that their requests and intentions will be acknowledged in discourse. Consider (27)–(28) in Table 15:

In (27) the agent, a higher-ranking officer, presupposes that the addressee will help and answer positively (e.g. Sir, yes sir in (27a)): a pro-anticipation is formed as a relation between a first sentence and the subsequent sentence. Failure to comply with these orders results in a counter-anticipation (e.g. Sir, no sir in (27b)). In (28), one agent requests a phone number, anticipating that a second agent will politely comply with the request (cf. please). The second agent complies with the request: a pro-anticipation is formed (cf. also the Marker Well). Imperatives thus introduce pro-anticipations in virtue of their structural status, and further sentences can add further anticipations based on imperatives’ content. Permissives follow similar anticipation patterns, although agents introduce requests rather than orders that other agents can comply with, via their actions. We propose that imperatives and permissives confirm prediction #2 in a nuanced manner: their use introduces anticipations about non-linguistic actions and linguistic continuations in discourse.

Agents who use emotive sentences can express emotions reflecting their psychological state towards propositions described by sentences (Wu, 2015: 81–82). Expressive sentences chiefly convey content describing the emotional states of agents in discourse (Wu, 2015: 106; Miceli and Castelfranchi, 2015: 20). Consider respectively (29)–(30) in Table 16:

An agent proposing the two questions in (29) explicitly introduces a pro-anticipation: that the agent answering the question promises to be happy. The second agent meets this pro-anticipation by answering in a positive if uncertain manner (i.e. Aye. Maybe). Thus, the second agent expresses emotions that approximately meet another agent’s anticipations. In (30), a first agent asks a second agent about feelings of disappointment; the second agent denies having such feelings. A possibility is that the second agent may have different feelings (cf. the focussed repetition of disappointed). The answer thus simply confirms that first agent’s pro-anticipation about receiving an informative (i.e. either positive or negative) answer to the question. As for interrogatives and imperatives, we believe this to be evidence in support of prediction #2.

Finally, agents can use announcement sentences to influence the external world and bring about changes in it through speech acts (e.g. Heine et al., 2021; Searle, 1983, 2007; Wu, 2015: 73, 208). Consider (31) in Table 17:

In a scenario in which a girl utters the reported speech in (31), one can anticipate that other agents did not meet the dress code of a given office. Hence, the girl establishes this formal requirement and possibly anticipates that the other agents ought to follow this requirement on future occasions. Thus, announcement sentences may pattern with imperatives and expressives in introducing pro-anticipations in contexts regarding non-verbal behaviour that can, however, affect verbal exchanges.

Overall, we now have evidence that information structure can shape linguistic content and anticipations via single clauses, sentences or discourse structures. This confirms the bottom-up prediction (i.e. #1) of our architecture. We also have evidence that discourse structure can shape how agents express linguistic anticipations as relations between the propositional/presuppositional content of sentences. This result confirms the top-down prediction (i.e. #2) of our architecture. We thus have evidence that our architecture can model data that were only partially addressed in previous accounts. Before we answer our research questions, we offer a further case study (Table 18).

A case study: anticipation chains in discourse

In (32), a man called “Dr. Tao” is described as preparing tea for the whole day. In the second sentence, the temporal Discourse Marker then clarifies that the events described in the first sentence occur afterwards. In this case, the second sentence seems to broaden the context and the set of anticipations in discourse, rather than introducing further pro- or counter-anticipations. In (33), the adverbial Discourse Marker of course in the second sentence introduces a pro-anticipation about the request in the first sentence: the second agent was expecting the request of “kudu” from the first agent. In (34)’s first sentence, an agent asserts to deserve something (far) more than another agent. The first agent acknowledges that some of the second agent’s merits were, however, surprising: the agent introduces a counter-anticipation.

In (35), the first sentence introduces a pro-anticipation about two agents sharing common interests. The second sentence introduces a new pro-anticipation (i.e. the agents becoming good friends) as a consequence of the first anticipation: this fact is explicitly captured via the Marker indeed. In (36), the first sentence introduces information about an unpleasant result for the agent (i.e. a counter-anticipation, cf. sadly). The second sentence introduces some more information about the context, thus confirming the counter-anticipation from the first sentence. In (37) we have the reverse pattern, as the first sentence introduces a pro-anticipation (i.e. something being a good idea). The second sentence explains that the agent entertaining the idea failed to realise it (i.e. we have a counter-anticipation via however, really).

In (38), the first sentence introduces the existence of a malignant tumour as a sad event for the agent: the sentence thus introduces a counter-anticipation. The second sentence adds more background about how this event came into being, cf. the temporal Marker when. Thus, the mini-text introduces a counter-anticipation chain. In (39), a long first sentence introduces a certain event of “deck-building” as a daunting task: the agent marks this as a counter-anticipation. The second sentence offers a detailed explanation about how this daunting task can be turned into a pro-anticipation, i.e. an event that the agent can expect in a positive manner. In (40), the first sentence introduces a counter-anticipation about author Philip Roth’s presence at an event (cf. however); the second sentence confirms this counter-anticipation by adding more information about the reasons for this absence (cf. furthermore).

Overall, sentence-forming (mini-)discourses can introduce anticipations as relations between their propositions/presuppositional content, i.e. the events they describe. Relations between anticipations form chains of anticipations in discourse in a potentially recursive manner. The cycle of anticipations and their alignments outlined in (5), Table 6 seems to emerge also at the language level. Thus, we have evidence that confirms the anticipation-based cognitive structure we proposed in section ‘Anticipation: definitions and role in cognition’, and we have evidence that it can account for the dynamic, iterative nature of anticipations at the linguistic level. Our predictions in Table 5 seem borne out also at a linguistic level, recursively. We can now turn to the discussion.

Discussion and conclusions

We believe that our proposal, although certainly restricted in its empirical range, nevertheless reaches three results that can provide answers to our research questions.

The first question pertains to how pro- and counter-anticipations emerge at a linguistic, i.e. sentential and discourse level. Our answer is that agents constantly form anticipations about future events based on cognitive context, which crucially includes memories of past and present events (Gardenförs, 2014; Narrog and Heine, 2018; Sperber and Wilson, 1995). In language, anticipations emerge as relations between the information units (presuppositions/propositions) that describe these events, and that clauses or larger predicative/grammatical structures can express (e.g. Roberts, 2012). Our proposal suggests that sentence types (declarative sentences) and information structures (e.g. subject–predicate structures) can determine how anticipations emerge in language. Sentence types and discourse structures, therefore, can present complex cyclic networks of anticipations. Our proposal thus seems consistent with models of language in which context and language interact systematically, via the guiding principle of anticipation (e.g. Lu, 2017; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004; Lambrecht, 1994; Geurt, Beaver and Maier 2024; Asher and Lascarides, 2003).

The second question pertains to which categories and structures jointly realize anticipation(s) at a linguistic level. Our answer confirms insights from previous literature in a nuanced manner, we believe. We have shown that adverbials like sadly and connectives like furthermore, then can capture pro- and counter-anticipations in language, as well as expanding the set of anticipations at stake (cf. section ‘A case study: anticipation chains in discourse’). Previous works on Discourse Markers offer similar claims to ours (e.g. Kaltenböck et al., 2011; Aikenvhald, 2015; Traugott, 2022; Heine et al., 1991; Heine et al., 2021). Crucially, our first answer and our examples suggest that sentences can introduce anticipation implicitly, in virtue of the content they introduce. Discourse Markers can explicitly select which anticipations are at stake, but anticipations nevertheless seem to connect linguistic structures at various levels.

The third question pertains to how linguistic patterns realise anticipation as a cognitive phenomenon. Our answer is that agents process implicit or explicit anticipations, add further linguistic units in discourse based on these anticipations, and then confirm or counter them according to their intentions (cf. again van Dijk & Rietveld, 2021; Poli, 2017, 2019; Searle, 1983, 2007). Anticipation thus acts as a guiding principle of cognition that can potentially make our experience of the world coherent (e.g. Clark, 2013a, b, 2018; Howhy, 2013). In language use, anticipation can also potentially make our linguistic experience coherent, since it allows us to combine informational and interactional content into unified linguistic meanings (i.e. propositions and presuppositions). Our answers hence address our research questions, and confirm that our predictions #1 and #2 are borne out, with respect to our target category. We also believe that our proposal introduces five innovations with respect to previous works on anticipation(s) in language.

First, we suggest that grammatical/discourse structures can implicitly shape anticipations, as per prediction #1. Again, multi-clausal sentence types inherently combine propositional and interactional content. Thus, they can capture anticipations via the modulation of this content that occurs via information structures (e.g. Lambrecht, 1994; Roberts, 2012). Anticipations, therefore, seem to emerge as a structural necessity: comprehensible discourse structures should be cohesive and coherent (e.g. Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004). Agents may implicitly strive towards coherent discourse, but may also insert categories that explicitly express agents’ anticipations about discourse and context to explicitly maximise coherence, also as per prediction #1. The innovation in our proposal is that we show how structure and categories can jointly define and maximise the expression of anticipations in language, as per prediction #2.

Second, we certainly suggest that Discourse Markers explicitly convey anticipations. However, we also suggest that mismatches in implicit anticipations yield uninterpretable structures. For instance, question-answer pairs form coherent units insofar as answers match the information presupposed in questions; otherwise, these pairs become incoherent (cf. (24)–(26) in Table 14). Similarly, sentences and texts/discourses implicitly define types of anticipations; the insertion of Discourse Markers not matching these types leads to uninterpretable sentences/discourses (cf. (14)–(19) in Table 11). The innovation in our proposal is that we show how language use can become incoherent if anticipations are not met; prediction #2 seems to receive further support.

Third, frameworks such as Rhetorical Structure Theory (e.g. Bateman, 2008; Mann & Thompson, 1987) or Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (e.g. Asher and Lascarides, 2003) have suggested that so-called rhetorical or discourse relations connect presuppositions and propositions to establish the conceptual, semantic coherence of discourse. We propose that rhetorical relations may be the linguistic counterparts to our notion of anticipation(s). Anticipation and anticipation chains thus seem to be relations among propositional and interactional content that can be recursively defined via the formation of increasingly complex discourse structures (e.g. Bateman, 2008; Asher and Lascarides, 2003). The innovation in our proposal is that we can potentially connect this view of anticipations to well-established research paradigms on discourse and rhetorical structure. We leave this more preliminary insight for future research; however, it deserves a full-fledged model beyond our preliminary proposal.

Fourth, our proposal seems to contribute to the debate regarding discourse grammar proposals (e.g. Heine et al., 1991; Narrog and Heine, 2018; Heine and Kuteva, 2007; Heine et al., 2021). If discourse grammar manages informational content and thetical grammar manages interactional content, then anticipations should act as the conceptual “glue” connecting these distinct content types. This integration is consistent with the cognitive architecture that we have introduced in Fig. 1, but also with the language architecture proposed in these works. Even if these two grammars may manipulate different types of content and the categories expressing this content, our architecture predicts that language use must bring these types together. We can thus conclude that anticipation in language establishes coherence/rhetorical relations among distinct and yet connected aspects of cognition. Again, further exploration of this topic must wait for future works.

Fifth, our proposal seems to shed more light regarding how theories of anticipation in cognition and language may be falsifiable. Prediction #1 can be proven wrong if anticipation does not shape our understanding of non-linguistic events, and linguistic structures lack implicit or explicit expressions of anticipation. This prediction can be falsified on a language-specific basis. If a language lacks language units expressing anticipation types (e.g. interrogative sentences, Discourse Markers), then the role of anticipation should be reduced if null, in that language. Prediction #2 can thus be falsified if a language does not shape non-linguistic anticipations and the use of categories in languages does not trigger uninterpretable structures. A falsifying case would involve uses of language in which “mismatches” between sentences’ content and Discourse Markers are acceptable (e.g. if sentences like (14)–(19) become interpretable). Previous works reject this falsification hypothesis (e.g. Heine, 2023); however, we believe that further empirical findings are necessary regarding this prediction.

In conclusion, this paper has offered a theory of how anticipation, a pervasive mechanism in human cognition, guides the use of language at the information structure and discourse structure levels. The paper has shown that anticipation shapes how agents intentionally make predictions about future events based on past knowledge and present beliefs, and how these anticipation patterns emerge at a language level. The paper has then suggested that agents express anticipation patterns in language by using clauses and sentences to convey information structures and the presuppositions and propositions that these structures convey. Anticipations emerge as semantic (i.e. coherence) relations among these linguistic information units, and can be expressed via dedicated though generally optional categories (e.g. Discourse Markers). We thus achieve our goal of connecting research on anticipation in cognitive science with its study in linguistics. We believe that from this result, several studies could be implemented to further develop a theory of anticipation in language. We, however, leave such endeavours for future research.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files https://osf.io/7w4js. The data are also available at https://osf.io/7w4js.

References

Aikhenvald A (2012) The essence of mirativity. LingTyp 16(3):435–485

Akhmetzyanova A (2016) The theoretical analysis of the phenomenon of anticipation in psychology. Int J Environ Sci Educ 11(10):1559–1570

Aloni M (2005) Utility and implicatures of imperatives. In: VV. AA (eds) Proceedings of DIALOR’05. SEMDIAL, Loria, Nancy, France

Altschuler D (2020) Tense and temporal adverbs: I learned last week that there would be now an Earthquake. In: Gutzmann D, et al. (eds.) The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley: New York. 1–18

Asher N, Lascarides A (2003) Logics of conversation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Assimakopoulos S (2017) Context in relevance theory. In: Blochowiak J, Grisot C, Durrleman S, Laenzlinger C (eds) Formal models in the study of language. Springer, Cham

Bara BG (2010) Cognitive pragmatics: the mental processes of communication. translated by John Douthwaite. Cambridge/MA: MIT Press, Cambridge MA

Barrett L, Simmons W (2015) Interoceptive predictions in the brain. Nat Rev Neur 16(2):419–429

Bateman J (2008) Multimodality and Genre: A Foundation for the Systematic Analysis of Multimodal Documents. London, Palgrave Macmillan

Beaver DI, Geurts B, Denlinger K (2024) Presupposition, Edward N. Zalta and Nodelman U (eds). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (Fall 2024 edn), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2024/entries/presupposition/

Berkum JV, Brown JA, Pienie Zwitserlood CM, Kooijman V, Hagoort P (2005) Anticipating upcoming words in discourse: evidence from ERPs and reading times. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 31(2):443–466

Bock K (1996) Language production: methods and methodologies. Psychol Bul Rev 3(4):395–421. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03214545

Breen M (2014) Empirical investigations of the role of implicit prosody in sentence processing. Lang Ling Com 8(2):37–50

Britannica T Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, June 15) Free energy. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/free-energy

Buckner R (2010) The role of the hippocampus in prediction and imagination. Ann Rev Psychol 61(1):27–48

Cañal-Bruland R, Mann DL (2024) Dynamic interactive anticipation–time for a paradigmatic shift. Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02135-9

Carroll J (2020) Imagination, the brain’s default mode network, and imaginative verbal artifacts. In: Carroll J, Clasen M, Jonsson E (eds) Evolutionary perspectives on imaginative culture. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46190-4_2

Chen Z, Wang M, Jiang Y (2022) Revisiting Guoran (as expected)—controvertial issues of default expectation markers. Cont Rhet 2(1):39–57

Chen Z, Jiang Y (2019) Counter-expectation and factivity: a case study on “reasonable” sentences. Stu Chi Lang 3(1): 296-310/382-383

Cinque G (2020) The Syntax of Relative Clauses: A unified analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Clark A (2013b) Are we predictive engines? Perils, prospects, and the puzzle of the porous perceiver. Behav Brain Sci 36(3):233–253

Clark A (2013a) Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behand Brain Sci 36(2):181–204

Clark A (2015) Surfing uncertainty: prediction, action, and the embodied mind. Oxford University Press, New York

Clark A (2018) A nice surprise? Predictive processing and the active pursuit of novelty. Phenom Cogn Sci 17(4):521–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-017-9525-z

Cravo AM, Rohenkohl G, Santos KM, Nobre AC (2017) Temporal anticipation based on memory. J Cogn Neurosci 29(12):2081–2089. 10.1162/jocn_a_01172

Croft W, Cruse DA (2004) Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Dahl Ö (2001) Grammaticalization and the life cycles of constructions. RASK: Int Tidsskrift Sprog Og Kommunikation 14(1):91–134

Davies M (2008-current) The corpus of contemporary American English (COCA). https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/

Defour T (2010) The semantic-pragmatic development of well from the viewpoint of (inter)subjectification. In: Davidse K, Vandelanotte L, Cuyckens H (eds). Subjectification, intersubjectification and grammaticalization. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, New York. pp. 155–196

Degen J, Trotzke A, Scontras G, Wittenberg E, Goodman ND (2019) Definitely, maybe: a new experimental paradigm for investigating the pragmatics of evidential devices across languages. J Prag 140(1):33–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.11.015

DeLancey S (2001) The mirative and evidentiality. J Prag 33(4):369–382

Dunbar RIM (2011) Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language. Faber & Faber, London

Engel AK, Maye A, Kurthen M, König P (2013) Where’s the action? The pragmatic turn in cognitive science. Trends Cogn Sci 17(2):202–209

Evans V (2019) Cognitive linguistics: a complete guide. Edinburgh. Edinburgh university press

Evans V, Green M (2006) Cognitive linguistics: an introduction. Routledge, New York

Ferreira VS (2010) Language production. WiRES Cogn Sci 1(6):834–844. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.70

Freunberger D, Roehm D (2016) Semantic prediction in language comprehension: evidence from brain potentials. Lang Cogn Neurosci 31(9):1193–1205. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2016.1205202

Friston K (2009) The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain? Trend Cogn sci 13(2):293–301

Friston K (2010) The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat Rev Neu 11(2):127–138

Friston K (2013) Active inference and free energy. Behav Brain Sci 36(3):212–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X12002142. 2013 Jun (Epub 2013) May 10. PMID: 23663424

Friston K, Daunizeau J, Kilner J et al. (2010) Action and behavior: a free-energy formulation. Bio Cybern 10:227–260

Galli G, Bauch EM, Gruber MJ (2011) When anticipation aids long-term memory: what cognitive and neural processes are involved? J Neurosci 31(12):4355–4356. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6369-10.2011. PMID: 21430135; PMCID: PMC6622893

Gardenförs P (2014a) The geometry of meaning: semantics based on conceptual spaces. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Geurts B, Beaver DI, Maier E (2024) Discourse representation theory. In: Zalta E, Nodelman U (eds). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/discourse-representation-theory/

Goddard C (2015) The complex, language-specific semantics of “surprise. Rev Cogn Ling 13(2):291–313. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.13.2.02god

Goldstein EB (2018) Cognitive psychology: connecting mind, research, and everyday experience (fifth edition). Cengage Learning, Inc., Boston

Grabenhorst M, Michalareas G, Maloney LT, Poeppel D (2019) The anticipation of events in time. Nat Commun 10(1):5802. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13849-0. PMID: 31862912; PMCID: PMC6925136

Gregory A (2021) Desire as belief. A study of desire, motivation and rationality. Oxford. Oxford University Press

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM (2004) An introduction to functional grammar (3rd edn.). Routledge, London

Hamblin CL (1987) Imperatives. Basil Blackwell, London

Heine B, Claudi U, Hiinnemeyer F (1991) Grammaticalization: a conceptual framework. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Heine B, Kaltenböck G, Tania Kuteva T, Long H (2017) Cooptation as a discourse strategy. Linguistics 55(4):813–855

Heine B (1997) Cognitive foundations of grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Oxford, accessed 19 Oct 2024

Heine B (2023) The grammar of interactives. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192871497.001.0001

Heine B, Kuteva T (2007) The genesis of grammar: a reconstruction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, accessed 16 Oct 2024

Heine B, Kaltenböck G, Kuteva T, Long H (2021) The rise of discourse markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hohwy J (2013) The predictive mind. Oxford, Oxford University Press

Huettig F, Janse E (2016) Individual differences in working memory and processing speed predict anticipatory spoken language processing in the visual world. Lang Cogn Neurosci 31(1):80–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2015.1047459

Huron D (2020) Psychological anticipation: The ITPRA theory. J Conscious Stud 27(3-4):185–202

Ippolito M, Kiss A, Williams W (2022) The discourse function of adversative conjunction. Proc Sinn und Bed 26(1):465–482. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2022.v26i0.1012

Jackendoff R (1972) Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass, 1972

Jiang J (2012) New thinking in verbal communication. China Book Press, Beijing

Jiang S (2008) The history of anticipation theory: from rational anticipation to kongming anticipation. Economic Science Press, Beijing

Jimenéz-Fernández Á (2024) To move or not to move: Is focus on the edge? J ling 57(1):1–32

Josselyn SA, Tonegawa S (2020) Memory engrams: recalling the past and imagining the future. Science 367:eaaw4325. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw4325. 202

Kadmon N (2001) Formal pragmatics: semantics, pragmatics, presupposition, and focus. Blackwell Publishers, Oxford

Kaltenböck G, Heine B, Kuteva T (2011) On thetical grammar. Stud Lang 35(4):848–893

Kant I (2002) Critique of pure reason, translated by LI Qiuling. Renmin University of China Press, Beijing

Kleinschmidt DF, Jaeger TF (2015) Robust speech perception: recognize the familiar, generalize to the similar, and adapt to the novel. Psychol Rev 122(1):148

Koktová E (1986) Remarks on the semantics of sentence adverbials. J Prag 10(1):27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(86)90098-6

Kuperberg GR, Jaeger TF (2016) What do we mean by prediction in language comprehension? Lang Cogn Neurosci 31(1):32–59

Lambrecht K (1994) Information structure and sentence form: topic, focus, and the mental representations of discourse referents. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Langacker RW (2008) Cognitive grammar: a basic introduction. Oxford University Press, New York

Levinson SC (2024) The dark matter of pragmatics: known unknows. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press

Li Y (2022) On the integration of morphology, syntax and structure—preface to multi-level study of causal expression in modern Chinese. In: Lu F (ed.). A multi-level study of causal expression in Modern Chinese. Shantou University Press, Shantou

Liu H (2012) Speech communication. Jiangxi Education Press, Nanchang

López CS (2017) Mirativity in Spanish: the case of the particle mira. Rev Cogn Ling 15(2):489–514

Lu F, Zhu B (2019) The Expectation Discrepancy Information and Category in Language. Journal of Changshu Institute of Technology 4(1):11–20

Lü S (1982) Outline of Chinese grammar. Commercial Press, Beijing

Lu F (2017) A Study of counter-expectation Markers in Modern Chinese. Beijing: China Social Science Press

Mann WC, Thompson, SA (1987) Rhetorical Structure Theory: Description and Construction of Text Structures. In: Kempen G (eds) Natural Language Generation. NATO ASI Series, vol 135. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-3645-4_7

Marie A, Vandenbergen S, Aijmer K (2007) The semantic field of modal certainty: a corpus-based study of English adverbs. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York

McHugh D (2023) Exhaustification in the semantics of cause and because. Glossa: J Gener Linguist 45(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.7663

McRae K, Hare M, Elman JL, Ferretti T (2005) A basis for generating expectancies for verbs from nouns. Mem Cogn 33(11):1174–1184

Meier C (2003) The meaning of too, enough, and so… that. Nat Lang Semant 11(1):69–107. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023002608785

Miceli M, Castelfranchi C (2015) Expectancy and emotion. Oxford University Press, New York

Miyagawa S (2022) Syntax in the Treetops. the MIT press, Cambridge, MA

Monfort S, Stroup HE, Waugh CE (2015) The impact of anticipating positive events on responses to stress. J Exp Soc Psychol 58(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.12.003

Mullally S, Maguire E (2014) Memory, imagination, and predicting the future: a common brain mechanism? Neuroscientist 20(1):220–234

Murga FG (2017) On adversative coordinative conjunctions. Theoria: Int J Theor Hist Found Sci 32(3):303–327

Nadin Mihai N (2016) Anticipation across disciplines. Springer Cham

Narrog H, Bernd H (eds.) (2018) Grammaticalization from a typological perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pezzulo G, Hoffmann J, Falcone R (2007) Anticipation and anticipatory behavior. Cogn Process 8(1):67–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-007-0173-z

Piccinini G (2015) Physical computation: a mechanistic account. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Pickering M, Garrod S (2007) Do people use language production to make predictions during comprehension? Trends Cogn Sci 11(1):105–110

Pierrehumbert JB (2016) Phonological representation: beyond abstract versus episodic. Ann Rev Ling 2(1):33–52

Pierrehumbert J, Hirschberg J (1990) The meaning of Intonational contours in the interpretation of discourse. In: Cohen P, Morgan J, Pollack J (eds). Intentions in Communication, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. pp. 271–311

Poli R (2017) Introduction to anticipation studies. Springer, Berlin

Poli R (2019) Handbook of anticipation: theoretical and applied aspects of the use of future in decision making. Springer, Berlin

Pylyshyn Z (1984) Computation and cognition. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Qiang X (2020) Non-specific and specific expectations in counter-expectation situations: a case study of jingran and pianpian. Stud Chi Lang 6(1):675–689. /767

Ran G (2021) The secret of the brain—psychological expectation. China Social Science Press, Beijing

Ranger G (2018) Indeed and in fact: the role of subjective positioning. In: Ranger G (ed.) Discourse markers. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp. 135–178

Rescorla M (2020) The computational theory of mind. In: Zalta EN (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 edn). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/computational-mind/

Roberts C (2012) Information structure in discourse: towards an integrated formal theory of pragmatics. Semant Pragmat 5(6):1–69

Rothermich K, Kotz SA (2013) Predictions in speech comprehension: fMRI evidence on the meter–semantic interface. Neuroimage 70(1):89–100

Schacter DL (2012) Constructive memory: past and future. Dialog Clin Neurosci 14(1):7–18. 22577300

Schwarzschild R (2020) The representation of focus, givenness and exhaustivity. In: Bhatt R, Ilaria Frana I, Menéndez-Benito P (eds.) Making worlds accessible. Essays in Honor of Angelika Kratzer. UMass ScholarWorks

Searle J (1983) Intentionality: an essay in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Searle JR (2007) Illocutionary acts and the concept of truth. In: Greiman D, Siegwart G (eds). Truth and speech acts: studies in the philosophy of language. Routledge, London. pp. 5–31

Shi A (1986) Presupposition of sentence meaning. Linguistic res 2(1):27–32

Siemund P (2013) Interrogative constructions. In: VV.AA. (eds) Varieties of English: a typological approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp. 237–257

Spens E, Burgess N (2024) A generative model of memory construction and consolidation. Nat Hum Behav 8(3):526–543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01799-z

Sperber D, Wilson D (1995) Relevance: communication and cognition. Blackwell, Oxford, 2nd.ed

Sutton J (2008) Material agency, skills and history: distributed cognition and the archaeology of memory. In: Knappett C, Malafouris L (eds.) Material agency: towards a non-anthropocentric approach. Springer, US. pp. 37–55