Abstract

This paper examines the development of modern universities in China between 1840 and 1949—a period marked by the negotiation and coexistence of diverse value systems. During this time, the university spirit integrated diverse civilizational cores, which is reflected in the spatial design of the campuses. Taking 25 modern Chinese universities as research subjects. Employing a bifurcated historical methodology and the theory of cultural hybridity, the research traces the history of university construction and outlines the historical framework of university spirit through material forms. The research reveals that cultural hybridity follows a phased pattern of “encounter—appropriation—adaptation—integration—new ecological form.” In the semi-colonial context, diverse actors actively participated in dynamic processes of cultural hybridization, which profoundly shaped spatial forms. The transformation of the modern university spirit is reflected in the creative translation of spatial morphology. Based on these findings, the study proposes a dynamic model for campus heritage conservation, viewing the campus as a continuously evolving whole. Moving beyond the research paradigm of architectural history, it introduces a multi-threaded model of cultural hybridity, offering historical insights for cultivating a distinctive university identity in the era of globalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary universities, in their development process, tend to prioritize spatial expansion, efficiency, and administration, while paying insufficient attention to the inheritance and continuation of university spirit (Wu 2011). The standardized and instrumentalized mode of campus construction has consequently damaged or weakened the spatial atmosphere that once carried the university’s cultural and academic spirit (Wen 2015). For high-quality university development, material expansion and the cultivation of spiritual values should be complementary. Thus, the relationship between spatial development and the transmission of university spirit must be carefully managed. Addressing this contradiction requires a historical perspective: the interaction between material space and spiritual tradition is essentially shaped through the accumulation of seemingly ephemeral experiences over time. When campus construction neglects cultural continuity within the historical development trajectory, its spiritual legacy risks becoming an isolated system lacking historical depth and coherence. Harrod Perkin examined higher education from a historical perspective, noting that “One cannot understand the contemporary university without understanding the very different concepts of the university which have existed at different times and different places in the past” (Clark 1984). The development of university spirit requires drawing strength from historical foundations and finding a clear direction, and the rich historical connotations of the university spirit in modern China can address this need (Chu 2013). The shaping of modern Chinese university spirit occurred at a historical juncture marked by the collision and adaptation of Chinese and Western cultures. It did not originate solely from the West but emerged through innovations made by culturally aware intellectuals who synthesized Chinese and Western ideas within university practices (Chu 2004). This represents the practical wisdom of cultural adaptation, eventually materialized in spatial forms that embody cross-cultural dialogue. Studying the spatial forms of universities during this transformative period reveals the values held by scholars and administrators amid foreign influence, offering insights for fostering university spirit in the contemporary context of globalization.

With the evolution of economic conditions, social structures, and values, university spirit increasingly finds expression through physical space. As a material reflection of educational philosophy, the spatial forms of a university embodies specific cultural mechanisms through both its functional layout and symbolic systems, which in turn shape and reinforce the university spirit. The transformation of the modern Chinese university illustrates the dynamic interplay between spirit and material space. During the eastward transmission of Western learning, the replacement of the traditional academy system by the modern university system was primarily realized through the reconstruction of physical space. In the 19th century, China was significantly influenced by Western learning, leading to the collapse of the traditional Chinese academy model that had long served the imperial examinations and giving rise to the modern university. During this period, educational concepts and the way universities were run underwent drastic changes. The missionaries used education as a vehicle for religious outreach and established church universities on Chinese soil. Following the establishment of the Republic of China government, influential universities in Chinese society included not only church universities but also state universities and private universities, all of which played a significant role in shaping modern higher education in China. As a large-scale construction activity during this period, modern Chinese universities conveyed cultural values and educational ideals in a direct and enduring manner through campus architecture and other material carriers, subtly fulfilling educational functions (Wu 2020). Although the architectural form of these universities responded to societal changes with some delay, it effectively recorded the evolution of societal ideologies. Based on this historical trajectory, analyzing the localized adaptation of spatial forms in modern Chinese universities under the impact of foreign cultures reveals changes in the cultural subject’s educational vision. This, in turn, offers meaningful insights into the development of contemporary university spirit in the context of globalization.

In universities, spiritual culture, institutional culture, environmental culture, and behavioral culture are organically unified (Wang 2008). However, most early research on universities focused on the university spirit and system, with less attention given to the material form of universities (Jaspers 1961). In the 1980s, as universities expanded, the growing demand for campus construction shifted attention toward the material form of universities. Architectural theorist Richard Dober analyzed contradictions in numerous campus construction projects and provided valuable ideas and strategies for university planning and construction (Dober 1963, 1991, 1996). Chinese scholars have also been exploring ways to accommodate the continuous growth to plan for the continuous growth of university space in China (Lv 2002). Xu Weiguo’s Research on Modern Chinese University Campus was the first to systematically examine the development of modern university campuses (Xu 1986). Subsequent scholars have traced the evolution of modern university construction, focusing on the changes in campus architecture as a means of reflecting the history of modern educational architecture (Luo 1984; Xue 2005; Qiu 2006; Wang 2018; Dai 2008). Although previous research has completed the genealogy of campus architecture, it has not yet moved beyond the traditional research paradigm of “architectural history” and rarely explores the deeper mechanisms of interaction between spatial form and spiritual culture.

As research deepened, scholars began to study university ideology in relation to material form. Some scholars approached architectural form from the perspectives of history and anthropology, focusing on how university philosophy, architectural trends, and architects’ styles influence design (Turner 1984). Meanwhile, higher education researchers examined university architecture from a pedagogical standpoint, highlighting that the university system, academic activities, social culture, and university architecture are mutually influential and interdependent (Zhang 2005).

Values are not only reflected in architectural form but also in overall campus space planning. Chen comprehensively analyzed the evolution of spatial forms in modern and contemporary Chinese universities, considering the social value orientation of universities, and explored how university campus forms feedback into and reshape socio-political, economic, and cultural dynamics (Chen 2008). Similarly, Huang et al. analyzed the evolution of the campus axis space at Lingnan University to investigate changes in social value orientation in the construction of Chinese university campuses since modern times (Huang et al. 2021). Existing studies mostly focus on the analysis of university spatial form evolution through a single perspective of mainstream historical events, primarily from the viewpoint of elite discourse. It lacks an analysis of the role played by multiple actors in the interaction between the spiritual and material dimensions.

The construction of modern universities occurred against the backdrop of a dramatic collision between Chinese and Western cultures, which introduced a fusion of these influences into the research field of modern Chinese universities. However, most research in this area focuses on the exchange of Chinese and Western architectural and educational cultures, often using church universities as the entry point, with Western missionaries playing a dominant role in these exchanges (Sun 1995; Ma 2002; Chen 2007). Feng et al. highlighted that modern Chinese universities, from their planning structure to their architectural art, exhibit characteristics of the juxtaposition of Chinese and Western cultures (Feng and Lv 2016). Liu examined the influence of Western culture from the perspective of architectural technology and illustrated how Western technologies and expertise helped bridge China’s connection with the outside world in the early 20th century (Liu 2014). However, constrained by a static, structuralist analytical framework, they fail to account for the temporal and evolving characteristics of spatial form as a cultural carrier—particularly the dynamic role of local cultural subjectivity in the reconstruction of space.

Although existing studies have touched upon the relationship between spatial form and spiritual culture, most have reduced university spirit to a static concept and analyzed the evolution of university spatial form based on linear, forward-thinking approaches. This perspective overlooks the dynamic shaping process resulting from the collision between Chinese and Western cultures in modern times. This study takes modern Chinese church universities, government-run universities, and private universities as case studies. It focuses on both the strategic adaptation of Chinese and Western cultures by Western missionaries in China and the proactive participation of Chinese sponsors in cultural adaptation within their local contexts. The spatial form of universities during this period reflects the value transformation of intellectuals, government officials, and other multi-identity subjects under the influence of foreign cultures. It also offers insights into the spiritual development of contemporary universities in the context of globalization. Furthermore, this study explores how spatial forms are shaped through the complex negotiation of cultural subjects. By analyzing the material-spiritual framework, it provides a new dimension for the value assessment and protection of architectural heritage on university campuses, based on architectural history.

Theoretical basis

Cultural hybridity

“Hybridity” is derived from biology and botany, where “hybridization” refers to the process of mating. The concept was introduced into linguistic studies by Bakhtin and other scholars in the early 20th century. Bakhtin defined hybridity as the mixing of two social languages within a unified discourse (Young 2005). Said later emphasized the ubiquity of cultural hybridity and rejected cultural essentialism (Said 2012). Building on these foundations, Homi Bhabha developed a theory of cultural hybridity, arguing that cultural encounters inevitably produce a “threshold state”—a space that is neither one of total assimilation nor absolute resistance. The theory of hybridity views cultural interaction not as a one-way cultural transplantation, but as a dynamic process of negotiation. It shifts the analytical focus from the static nature of culture to the fluidity of negotiation (Bhabha 2012). In the development of modern Chinese universities, the appropriation of the Western university model might appear to be a one-way process of Western cultural colonization, but in reality, it implies a complex negotiation of power. Bhabha’s theory provides a powerful analytical lens for examining the cultural negotiations involved in the formation of modern Chinese universities, helping to explain the emergence and persistence of university spirit both under Western cultural influence and within localized practices.

Homi Bhabha’s theory of cultural hybridity, as a central strand of postcolonial theory, has become a vital tool for critical cultural analysis since its introduction into Chinese academia through translation in the 1990s (Wang et al. 2011). In the field of education, this perspective emphasizes moving beyond binary oppositions and focusing on self-awareness and cultural identity (Xiang 1999). Drawing on postcolonial theories, Chinese scholars are able to retrace the logic of subjectivity in processes of cultural appropriation, thereby challenging the dominance of Western educational paradigms (Chu 2005). However, the application of postcolonial theory in China remains rare in the field of architecture. To construct a material-spiritual research framework, this study requires an analytical paradigm capable of explaining how the theory of hybridity is spatialized and materialized in architectural practice.

Peter Burke pointed out in Cultural Hybridity that the concept of hybridity encompasses a broad range of terms and classifications (Burke 2009). He emphasized that cultural hybridization is a long-term, dynamic process, driven by mechanisms such as encounter, appropriation, and integration among diverse cultures (Burke 2016). Unlike postcolonial theorists such as Bhabha, who focus on deconstructing power discourses, Burke places greater emphasis on the material processes and historical outcomes of cultural interaction (Chen 2018). This study aims to apply the concept of “cultural hybridity” to analyze how Chinese and Western social values were negotiated, appropriated, and integrated in modern times. Specifically, how has Chinese higher education been impacted by this process, and how is it reflected in the spatial form of universities? This analytical framework helps the simplistic thinking of one culture’s absolute dominance in negotiation and encourages a more dynamic and gradual exploration of the interaction between Chinese and Western cultures.

Bifurcated history

Since the “semi-coloniality” of modern China was largely manifested through the cultural penetration of multiple imperial powers, as well as the resistance and coexistence exhibited by the resilience of local civilization, Bhabha’s theory—which is rooted in the colonial experience of British India—has limitations in fully addressing the specific historical context of China’s semi-colonial condition (Feng 1998). Moreover, China’s semi-colonial condition in the modern era was grounded in a deep reservoir of pre-colonial cultural resources. This historical specificity necessitates a critical adaptation of postcolonial theory in the Chinese context: rather than reducing hybridity to a simplified narrative of “cultural negotiation between East and West,” it is essential to reveal the intricate entanglement of multiple cultural subjectivities and their underlying ideological formations. Prasenjit Duara’s conception of “bifurcated history” provides a methodological breakthrough in this regard. At its core, this theory seeks to dismantle the linear narrative of history as a unidirectional evolution from “tradition” to “modernity,” highlighting instead the coexistence and interaction of multiple temporalities in historical processes, thereby enabling a diversified and multilayered narrative structure (Duara 1996).

In the transformation of modern Chinese higher education, institutions such as church universities led by Western missionaries, the Imperial University of Peking established by the Qing government, and academies restructured by private forces collectively formed a plural and parallel trajectory of institutional evolution. The positions taken by different actors in interpreting the same historical period can generate distinct historical narratives (Duara 2004). These modern educational initiatives were not simple linear replacements of one another, but rather merged into the modern university system through processes of negotiation. By reconstructing the historical staging framework, the theory of bifurcated (or complex) history treats cultural hybridization as a transient and cascading process. It breaks through the conventional paradigm of linear historical stages and effectively exposes the obscured contributions of diverse actors such as civic groups and religious organizations within dominant historical narratives (Wei 2006). Through the dual dimensions of spiritual inheritance and spatial form, this approach constructs a more comprehensive historical framework for systematically analyzing the developmental trajectory of modern higher education.

Methodology

Sample selection for the research

The university samples selected for this study were established between the late Qing Dynasty and the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and they encompass a diverse range of actors that influenced the transformation of modern higher education, including the Qing government, the Beiyang government, the Republican government, as well as overseas Chinese and industrialists. The samples are categorized into three types: state universities, church universities, and private universities, based on the organizations that initiated their construction. The criteria for selecting the samples are as follows: (1) selecting university campuses with significant scale and influence, which have preserved blueprints or historical construction materials, to ensure that the selected samples are representative and persuasive; (2) analyzing the campus construction ideology of the time based on the planning drawings. This is because, on the one hand, modern China was in a period of turmoil, with many campus buildings not constructed according to the original plans due to economic, wartime, and other disruptions. On the other hand, the planning drawings offer a more accurate reflection of the intended campus construction ideas without being limited by real-world constraints, making them more useful for analyzing the conceptual aspects of university planning during that era.

Some universities underwent multiple versions of planning during the construction process, resulting in differences between the time of campus founding and the time of planning. During periods of complex ideological negotiation, planning ideas varied across different stages. In this study, we collected information on the founding time of the universities, the planning time (i.e., the completion time of the planning drawings used for spatial form analysis in this study), the founders, and the designers (Fig. 1). The aforementioned information provides the temporal background and identifies the key figures influencing the ideology and material form of modern universities. The information about the founders reflects the initial concept of the university within a specific era, playing a pivotal role in shaping the general direction of the university’s development. The information on university planners and designers reveals that individuals from different periods, due to their varied professional training and levels of expertise, approached design concepts differently. These differences had a significant impact on the planning and spatial form of the universities. This study uses the information of university founders as the basis for classification and divides universities into: government-run universities, church universities, and private universities. In different periods of modern times, the construction of these universities took on different scales (Fig. 1).

A deeper color shade on the chart indicates a higher number of universities of that type during the corresponding period. The entries highlighted in red among the campus planners represent key factors that significantly influenced the transformation of modern university spatial forms (Wu et al. 1971).

Research framework

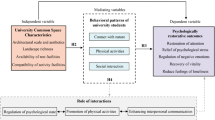

The prototype of Chinese universities can be traced back to academies (Shuyuan), while their Western counterparts originated from medieval monasteries. This study first analyzes the typical university spirit and spatial forms in China and the West prior to the onset of cultural hybridization, and then investigates the planning documents and historical materials of representative modern Chinese universities. These include archival records, institutional histories, and related literature. The aim is to explore, from the perspective of diachronism, how traditional Chinese educational systems were dismantled under the impact of Western culture, and how this continues to influence the transformation of contemporary universities (Fig. 2). The process of heterogeneous cultural hybridization typically occurs in three stages: contact with heterogeneous cultures, appropriation of fragments from these cultures, and integration of these fragments. During the integration phase, new ecotypes emerge (Burke 2016). The strategic adaptation of Chinese and Western cultures in modern China can be understood as following a similar process of cultural hybridization. This study examines the spatial evolution of various types of modern Chinese universities as an external manifestation of this process—depicting stages of encounter, appropriation, adaptation, integration, and renewal. By focusing on the roles of diverse historical actors—including Western missionary institutions, domestic governmental bodies, intellectuals, and the general public—it explores the ideological shifts induced by Sino-Western cultural hybridization and their corresponding transformations in university spatial configurations.

Tracing the earliest university spatial forms

The collegiate quadrangle plan in Western Europe

The earliest universities in the West can be traced back to the University of Bologna in Italy and the University of Paris during the Middle Ages. At that time, education was largely monopolized by religious theology, and the church was typically positioned at the center of university campuses. The layout of these universities followed an enclosed quadrangle model, also known as the monastic model, which combined teaching, living, and housing (Fig. 3). British educator John Henry Newman argued that while the monastic model of medieval universities isolated them from broader social and political life, it helped establish the university’s academic tradition of rationality and debate, as well as the spirit of self-government and freedom (Jaspers 1961). Following this model, Oxford and Cambridge Universities adopted similar designs, with libraries, churches, dining halls, and dormitories for teachers and students arranged in a collegiate quadrangle, fostering close-knit academic communities. The closed courtyard model was easy to manage and created a serious, independent academic atmosphere. However, after the Renaissance, universities began to moved away from the fully enclosed quadrangle model. For example, the University of Cambridge introduced a semi-enclosed square courtyard, opening up the internal and external landscapes, making the university more accessible. This shift reflected a growing openness, facilitating greater interaction between the university and the surrounding city, though it also created challenges with land use. The European university “academy school” layout had a profound influence on the spatial form of universities in North America and East Asian countries. For instance, in the early 19th century, the University of Tokyo in Japan featured many closed quadrangle and semi-enclosed courtyards (Fig. 3), demonstrating the lasting impact of this traditional planning method on university design worldwide.

The mall form of the United States

Western Europe’s “academy” layout had a profound influence on university design in North America during the colonial period. However, the demand for innovation and orderly growth in the United States gave rise to the “mall” form, which had a significant impact on modern university planning (Mayer 2015). North America’s abundant land resources allowed universities to be constructed away from city centers, often in suburbs, creating a quiet and independent academic atmosphere. As a result, the block-style college layout evolved into a suburban campus design. Universities began to emphasize comprehensive planning, shifting the focus from simply providing comfortable material spaces to ensuring the orderly growth of the campus. This led to the exploration of long axes and axisymmetric layouts (Wang et al. 2021), exemplified by the University of Virginia, which prominently featured a central axis with a rigorously symmetrical layout. In this context, spatial order in the United States was no longer a symbol of religious theocracy. After gaining independence, the United States began to pursue a societal model grounded in democracy and rationality. When Thomas Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, he envisioned the “ideal university” as a place that would promote equality and freedom, rather than hierarchical structures (O’Shaughnessy 2021). In a groundbreaking move, Jefferson’s campus design introduced the Rotunda, with the library as the center, breaking the traditional paradigm of religious belief as the core of education and placing emphasis on science and the humanities. The campus was designed around three buildings surrounding an open rectangular lawn, with the core buildings located at the short side of the rectangle. The layout incorporated a garden-like design with a rigorous symmetry (Fig. 3). This “mall” form became known as the “Academic Village” model in its later development.

The Chinese ancient academy

The traditional Chinese paradigm of li (ritual propriety) not only shaped the hierarchical structure of official education institutions (Guanxue) but also imposed strict spatial principles on the layout of academies (Shuyuan), emphasizing axial symmetry with core buildings located along the central axis. The spirit of the academy, which aimed to “teach students the way to be a human being and the way to learn”, required an integration of learning, living, and recreation. The formative structure of Chinese universities originated from the academies of the Song Dynasty, which embodied the creation and pursuit of the ancient Chinese university spirit. Mr. Hu Shi once noted that the abolition of the academy hindered the scholarly tradition of autonomous research, which had persisted for over a thousand years (Hu 1994). Confucian values of “Li” (ritual propriety), “Ren” (benevolence), and “Le” (harmony) shaped the academy’s functions, which included lectures in the form of lecture halls, rituals in the form of sacrificial halls, and book collections in the form of libraries, as well as lodging and cafeterias. This spatial form stands in contrast to the rigid hierarchical layout of official schools, which strictly followed the “temple on the left, school on the right(左庙右学)” principle (Fig. 3). With the rise of the official school system, the academy gradually became tied to the imperial examinations. However, its architectural form remained largely unchanged, with a focus on enlarging lecture halls and lodging areas, while the function of the book collection room was diminished (Li et al. 2014). The traditional Chinese academy combined knowledge and moral education, emphasizing that it was not only a space for academic research but also for cultivating personal virtue. In the academy, academic research and daily life were inseparable (Lou 2016). The integration of living and learning fostered an environment of self-study and interactive debate between teachers and students (Shang 2010). There are three types of architectural layout in traditional Chinese academies: tandem, juxtaposed, and tandem-juxtaposed (Fig. 3) (Kong and Bai 2011). Following the abolition of the imperial examination system in the late Qing period, the official education system was replaced by a modern school system, while the private education tradition was either absorbed into grassroots cultural practices or transformed into new-style academies that gradually integrated Western educational philosophies.

Intrinsic laws of heterogeneous cultural hybridization: evolutionary laws of spatial forms in modern Chinese universities

Phase Ⅰ: from cultural encounter to cultural appropriation

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and even earlier, Western cultures sporadically entered China. At that time, the Chinese government still maintained full sovereignty over the extent and depth of cultural exchanges between China and the West (Shen 2017). However, after the Opium War, China’s indigenous culture experienced a significant impact from Western culture, and cultural exchange shifted from controllable interaction to the direct appropriation of Western ideas. During this period, the strong influence of Western culture facilitated the initial development of the modern university model in China. Official universities represented China’s early efforts to incorporate Western science and culture into its educational system. Meanwhile, missionary universities served as key sites for the introduction of Western religious and cultural practices. The spatial manifestation of this process is reflected in the juxtaposition of heterogeneous forms.

(1) Educational ideology and spatial formation of government-run universities

The educational activities led by the Qing government combined Western learning with traditional Chinese education, drawing inspiration from the education models of Western Europe and Japan. During the Self-Strengthening Movement and Hundred Days’ Reform, “Chinese Learning as Substance, Western Learning for Application” was initially proposed, as the government began absorbing Western knowledge systems for development. However, the overall educational philosophy remained under the control of traditional feudal ideologies (Wang and Zhou 1986). Rather than a fusion of Chinese and Western education, there was a juxtaposition of the two. This period’s teaching concepts are reflected in the spatial forms of educational institutions, where Western architecture was directly introduced to accommodate the Western curriculum, while traditional academies continued to serve as the primary carriers of education.

At this stage, the spatial form primarily continued the tandem and juxtaposed layout of traditional academies, with the local, direct incorporation of Western-style single-family buildings and the collegiate quadrangle. The spatial planning of government-run universities displayed a heterogeneous juxtaposition in the appropriation of Western culture: Western learning was independently embedded into the layout of the academy through Western architecture, while Chinese learning followed a one-way, progressive structure using traditional academy designs (Fig. 4a.c.1). In the planning structure, academies were transformed into “Xuetang”, with the axis arranged in a one-way, progressive manner parallel to each other. Sanjiang Normal School, for example, was not fully planned but instead featured a collage of Chinese and Western layout patterns (Fig. 4c.1). The Xigu Campus of Imperial Tientsin University, rather than being a reconstruction of a traditional academy, presented a multi-entrance courtyard layout surrounded by Western-style buildings in its overall spatial design (Fig. 4a.c.2). In terms of the functional architectural layout, traditional academies had minimal requirements for living conditions, with the living areas in academies remaining in the form of lounges arranged in rows and columns, characterized by closed, elongated courtyards. However, under the influence of Western education, campuses began to emphasize the physical well-being of students, incorporating playground spaces into the planning. Regarding the relationship between the campus and the surrounding urban environments, many academies transformed into “Xuetang” in the late Qing Dynasty were located in urban centers to better serve their communities, with the campus buildings often directly facing main city roads. Overall, during this time, the planning of educational spaces in China continued to retain the multi-courtyard layout of traditional academies, with main buildings emphasizing axial relationships. The influence of Western culture was limited to the implementation of Western-style buildings that fulfilled specific educational functions.

The green sections depict events related to the Qing government’s reform of traditional academies and their corresponding spatial forms. The blue sections illustrate events associated with missionary-led education and the resulting spatial forms. The yellow sections represent events in which the Qing government established new campuses at alternative sites, along with their respective spatial forms.

(2) Educational ideology and spatial formation of the church university

During this period, Western churches conducted educational activities in China under the guise of “missionary work,” and the educational philosophy of church universities was heavily influenced by theology. The imperialists in China promoted “Western learning,” distinct from that proposed by the Qing government, and sought to implement colonial education through theological means. Following the events of 1900, missionaries recognized the challenges with their approach and shifted from “preaching” to “education” as a way to address the growing demand for education in Chinese society (Teng 1980). The missionary activities of the church, along with theological ideals, were also reflected in the spatial design of universities at this stage. These universities were modeled after Oxford and Cambridge, adopting the collegiate system with layouts resembling the monastic model.

In the early stages, church education did not have a specifically planned space or architectural layout. The “quadrangle” model of Western functional composite was introduced into China through individual buildings. For example, the earliest building at St. John’s University followed the “quadrangle courtyard” model. The layout between buildings was disorganized, with free development and no clear geometric composition, and roads were simply attached to the buildings (Fig. 4a.1). The courtyards were enclosed by the buildings, but there was no clear hierarchy or structure to the courtyard arrangement. The functional layout aimed to create a close connection between living and learning, with dormitories for students and faculty located in close proximity to academic buildings. The relationship between the campus and the city was more closed off. The campus was connected to the main road of the city via a road, rather than through direct contact, and the rest of the campus interface was formed by natural elements such as mountains or water.

Initially, Western and Chinese university planning remained juxtaposed rather than truly hybridized. However, as universities matured, spatial forms moved from passive appropriation to active adaptation, eventually leading to the integration of architectural principles.

Phase Ⅱ: from cultural appropriation to cultural adaptation

After the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, church universities began to seek ways to localize themselves in China, shifting from simple appropriation to exploring adjustments and adaptations within the new cultural system. The West started to engage more deeply with traditional Chinese culture. The church’s promotion of “localization” led to more profound cultural negotiation between Chinese and Western traditions, which were reflected in the architectural forms and spatial compositions of church universities. Due to limited understanding of traditional Chinese architectural forms at the time, this localization primarily involved surface-level coordination of architectural design and adaptation to the environment. As Chinese society embraced Western educational ideology, there was a growing interest in integrating Chinese educational concepts with Western ones. However, in the construction of government-run universities, Western planning, layouts, and architectural styles—typically led by Western designers—still dominated. This situation reflected both the delay in how university forms responded to the ideological shifts of the time and the constraints imposed by the societal conditions of the era.

(1) Educational ideology and spatial formation of church universities

At this stage, church universities began to actively pursue localization and secularization in China, advocating for the spirit of academic freedom. During the planning and construction of these universities, clear campus layouts were developed, with American designers introducing the mall form of modern, open university planning from the United States into China (Fig. 5b.1). In terms of planning structure, landscape-based axis spaces emerged in church university designs. This broke away from the traditional single-axis, parallel development model, instead adopting a cross-double-axis spatial structure. This shift is evident in the plans of the University of Nanking and Lingnan University, where adjustments were made to the orientation of buildings on both sides of the axis (Fig. 5b.2), illustrating how Western construction models were adapted to the Chinese context. In terms of building layout, the “college system” model, characterized by quadrangles with multifunctional spaces, was replaced by a layout featuring distinct functional zones. These zones clearly separated living areas, teaching areas, offices, and sports facilities. Architecturally, Western designers began to experiment with integrating Chinese elements, such as Chinese-style roofs, with Western architectural features like circular arched corridors. Although this negotiation was somewhat awkward, it represented the first attempt at blending Chinese and Western cultures in architecture and reflected the cognitive limitations of the time. Additionally, the church universities’ pursuit of secularization and academic freedom led to a shift in the core campus architecture—from seminaries to auditoriums—reflecting the diminished role of theological functions. West China Union University, for example, emphasizes academic freedom and sought to break away from closed academic spaces. Spatially, this was manifested through the coexistence of closed “college system” layouts and open, landscape-based axis organization (Fig. 5a.c.1).

The green sections depict events related to the secularization of church universities and their corresponding spatial forms. The blue sections illustrate the influence of emerging modern Chinese educational ideologies on university development, along with the spatial forms that resulted. The yellow sections depict events in which China pursued cultural negotiation at the ideological level, while Western scholars simultaneously applied and adapted their educational and construction models in the Chinese context—along with the corresponding spatial forms that emerged.

(2) Educational ideology and spatial formation of government-run universities

During this period, bourgeois-democratic education gained dominance in China. In addition to the construction of church universities, state universities expanded, and private universities were initially established. The educational policies under of the Ministry of Education under the Republican government, combined with the weakening control of the central government due to warlord conflicts, allowed universities greater autonomy and provided more space for academic freedom to develop in China. Cai Yuanpei’s philosophy of “Educating Five Domains Simultaneously” transcended the “ Chinese Learning as Substance, Western Learning for Application” dichotomy, emphasizing freedom and harmonious development, while Mei Yi-qi’s educational approach focused on fostering cooperation among students. Influenced by Western educational thought, they sought to integrate these ideas with traditional Chinese academies’ focus on human-centered education. However, these new educational concepts were not immediately reflected in the spatial form of universities. At this stage, the spatial layout and architectural style of campuses still largely pursued a Westernized model.

The 1913 planning of Tsinghua University was designed by the American architect Murphy. The east side of the campus, designated as a preparatory school for students studying abroad in the United States, followed the planning system of Western universities. In contrast, the west side, which housed the comprehensive university, incorporated the traditional Chinese sequence of courtyards, with multiple rows of enclosed courtyards. This spatial layout, referencing the “college system” courtyard model, continued the traditional Chinese inward-facing, multi-courtyard organization (Fig. 5b.c.1). During the same period, Peking University, with its emphasis on academic freedom, lacked a clear plan and integrated into the city with a fragmented layout, similar to the design of medieval universities in Western Europe. Despite these differences in planning approaches, both universities shared a common feature: their new school buildings were constructed in the Western architectural style.

At this stage, the construction of Chinese universities was primarily influenced by Western scholars who adapted Western cultural models to fit the Chinese cultural environment. This is evident in the Sinicization of the “mall” form in campus spatial layouts, where elements of Chinese culture were integrated. Additionally, Chinese architectural elements began to appear in the style of university buildings, reflecting an early negotiation of Chinese and Western design principles.

Phase Ⅲ : from cultural adaptation to cultural integration

During this period, the construction of church schools began to focus on deepening cultural negotiation between the East and the West. In 1921, the American Christian Church mandated that church schools be fully Sinicized as soon as possible, pushing the integration of Eastern and Western cultures to a new level. Consequently, changes in the architectural form and layout of universities during this period became significant in reflecting this deeper cultural integration. The missionaries’ experiences in China fostered an appreciation for traditional Chinese art, enabling them to understand the differences between Chinese and Western cultures more objectively and contribute to the integration of Chinese and Western architectural traditions (Dong 1998). At this stage, designer Murphy played an essential role in advancing the development of modern architectural theory in China (Hong 2016). In terms of planning layout, the pursuit of an open university design led to further exploration of the mall form, with universities adapting it to local conditions. Axis elements within the campus plans were gradually enriched. In the planning and construction of universities founded by the Beiyang government, as well as private universities, both Western and Chinese designers who had studied abroad were invited to collaborate. As a result, the planning and layout of government-run universities, private universities, and church universities during this period showed increasing similarities.

(1) Educational ideology and spatial formation of church universities

After the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal sentiments advocated by the May Fourth Movement, church universities in China began to adjust their relationship with Chinese society, which was reflected in their architectural forms. From this point, church university architecture started to evolve towards a retro style, particularly with the introduction of palace-style architecture. Meanwhile, the planning structure became more diversified, with main axis elements becoming more complex and the spatial hierarchy more defined. Murphy’s long-term practice and accomplishments in China also reflected the deepening integration of Chinese and Western architectural cultures, as he explored the blending of Western engineering technology and rational design methods with traditional Chinese classical architectural forms. In terms of campus planning, while some church universities continued using the mall form with landscape as the central axial component, Murphy began to explore a new Chinese adaptation of the mall form. He incorporated traditional Chinese garden layout into the planning of Yenching University and used a combination of corridors and courtyards, reminiscent of the Chinese classical academy, in his plans for Ginling College (Fig. 6b.c.2). The planning structure of church universities at this stage positioned the main building as the core component along the main axis, similar to the axial design of traditional Chinese academies. With secularization, the core buildings along the main axis no longer emphasized religious functions. In terms of functional layout, living, and teaching spaces were no longer placed at the same spatial level. Instead, teaching spaces, sports areas, and dormitories were connected along axes. This arrangement shaped a progressive courtyard space, transitioning from open to private areas, thereby continuing the spatial sequence typical of the traditional Chinese academy model.

The yellow sections depict events related to the establishment of private universities, along with the corresponding spatial forms. The blue sections illustrate events related to the localization of church universities and the corresponding changes in spatial forms. The green sections illustrate events involving the participation of Chinese scholars educated abroad in the planning and design of university campuses, along with the spatial forms that emerged from these efforts.

(2) Educational ideology and spatial formation of private universities

Chinese designers who returned from overseas during this period applied their professional expertise to find a path of adaptation between folk culture and Western culture, reflecting this integration in the spatial form of private universities. As early as the end of the Qing Dynasty, the Chinese had begun to actively seek ways to blend Western culture with their own in private building construction, though without professional understanding or application. After the New Culture Movement, the “theory of education for national salvation” and “theory of educational independence” became prominent social trends. Visionaries such as Zhang Bo Ling and Chen Jia Geng linked national education with the patriotic movement for salvation and strength, leading to the establishment of private universities. These institutions provided an opportunity for professional designers to integrate Chinese folk culture with Western architectural elements. In their planning, designers adopted Western campus planning models while taking into account local natural environments to modify the layout. For example, Nankai University replaced the traditional grass on the main axis with ponds as a key landscape element (Fig. 6b.3), while Xiamen University’s design incorporated several radial centered around the sea (Fig. 6b.4). In terms of architectural design, Xiamen University combined the composition, structure, and walls of Western classical architecture with the regional style of southern Fujian, particularly in the use of glazed tile roofs. This marked China’s proactive and planned attempt to explore the negotiation between Chinese and Western architectural cultures, as well as an initial effort in the selective adaptation of educational architecture, where folk architectural culture and Western architectural culture engage in negotiated participation.

In addition to the changes mentioned above, the concept of gender equality in education also began to influence university space during this period. The New Culture Movement brought the issue of equal education for men and women to the forefront, and the idea of coeducation gained worldwide acceptance. As a result, female dormitory spaces were introduced into campus plans, but they were typically positioned in more inward layouts, not part of the main axis space of the university, reflecting respect for women (Zhang and Chen 2021). This spatial arrangement reflected the evolving idea of educational equality that both China and the West were pursuing at the time. By this stage, cultural exchange between China and the West was no longer a one-way process of influence. The Chinese people began to engage more actively, contributing their own thoughts and initiatives.

Phase IV: from cultural integration to cultural renewal

The process of cultural hybridization inevitably generates new ecotypes, which are reflected in spatial forms (Burke 2016). Western churches in China gradually recognized Eastern culture and sought ways to blend Chinese and Western architectural styles. At the same time, domestic scholars who had received formal architectural education actively promoted this fusion, laying the groundwork for the emergence of a new architectural style referred to as “Chinese inherent architecture.” In terms of campus planning, Chinese scholars explored new layout models by incorporating elements from traditional Chinese academy designs. In 1929, the government of the Republic of China mandated that official buildings and public government structures adopt the “national inherent style.” This represented a significant step in the government’s initiative to integrate Chinese and Western cultures in the construction of government-run universities.

In 1927, the “Draft Educational Policy” marked the formal establishment of party-oriented education, which hindered the development of civic education and limited the liberalization of education. The solemnity of traditional Chinese official buildings and the rigorous use of axial space on university campuses aligned with the Kuomintang’s goal of implementing party education. However, due to the impact of the war against Japan, most college and university construction remained at the planning stage, with few projects being fully realized. Only Sun Yat-sen University and Wuhan University were largely completed among Chinese government-run universities. From the available drawings, it is evident that campus planning during this time emphasized monumental and ceremonial spaces. The courtyard layout of traditional governmental buildings and Western geometric compositional styles reflected the Kuomintang’s pursuit of spatial quality on campuses (Fig. 7b.c.4). In terms of architectural design, the “Chinese Inherent Form” combined traditional Chinese official architectural elements with advanced Western architectural techniques (Republic of China 2006). Overall, this phase focused on organizing composition and scrutinizing form, creating a grand spatial quality that balances both the “national” identity and the “university” attributes (Liu 2019).

The blue sections depict events related to the Nationalist Party’s implementation of party education and the corresponding spatial forms. The yellow sections illustrate events in which Chinese scholars explored new planning models through cultural negotiation between Chinese and Western paradigms, along with the spatial forms that resulted.

During this phase, Chinese scholars, driven by a pursuit of the spirit and symbols of traditional Chinese culture, selectively appropriated morphological symbols from classical official architecture to explore new planning and layout models for Chinese universities. In the 1930 planning of Tsinghua University, Yang Tingbao organized the core teaching area around a curved aqueduct inspired by the Piyong (辟雍) design (Fig. 7c.2). This is not a continuation of the enclosed spatial form of the academy, but rather a continuation of the symbolic elements of traditional Chinese culture. Water, symbolizing the source of wisdom and knowledge, flows through curved channels that encircle the campus, representing the flow and transmission of knowledge. This design embodies the educational philosophy of nurturing the pillars of the nation. Similarly, Hunan University expanded in concentric circles based on the Shuyua model, with Liu Shiying fully utilizing Yuelu Mountain and its surrounding natural and cultural resources to arrange the campus buildings and functions. The campus was harmoniously integrated with both Yuelu Mountain and the surrounding cityscape (Fig. 7c.3). The concentric circle layout and open campus structure at Hunan University reflected the institution’s pursuit of academic freedom (Wei et al. 2012). The emphasis on academics during this period also profoundly influenced campus planning. At Wuhan University and Sun Yat-sen University, which were built on hills, teaching buildings were strategically placed on hilltops to highlight the academic focus. In terms of functional layout, teaching groups became more emphasized, while living quarters were excluded from the axial composition, gradually separating learning and living areas. Even when the multi-entrance courtyard design of traditional Chinese academies was maintained, the contextualized scenario—where residence and study were integrated—began to fade, marking a shift away from the traditional Chinese educational model.

Conclusion and discussion

(1) The sustainability and flexibility of modern university spatial forms

The evolution of university spatial forms from the late Qing Dynasty to the founding of the People’s Republic of China represents a practical process of cultural hybridity theory. Using a multi-threaded historical methodology, this study traces the interplay between governmental planning intentions, Western missionary educational objectives, indigenous intellectual ideologies, and public perceptions under the semi-colonial context of modern China. This paper attempts to demonstrate how physical space reflects the dynamic process of cultural hybridity. Through extensive archival research and spatial analysis, this paper reveals that physical space embodies the core stages of cultural hybridity—encounter, appropriation, adjustment, integration, and renewal. Based on Burke’s framework, we refine the hybridity process by highlighting a distinct phase of spatial adjustment and adaptation between appropriation and integration. For example, Lingnan University’s reorientation of building axes, and the planning of Yenching University’s Weiming Lake area, reflect this adaptive process. While the Western narrative of landscape axes is maintained, elements such as curved bridges and pavilions from traditional Chinese gardens were introduced to dissolve the authority of strict axiality, thus transforming campus space into a physical interface of cultural negotiation.

The spatial forms of many universities in the modern era were shaped during this time, and even though construction continued after the founding of New China, most university campuses retained the patterns established in the modern era. Universities such as Lingnan University (now the site of Sun Yat-sen University), the University of Nanking (now the site of Nanjing University), National Sun Yat-sen University (now the site of South China University of Technology), and Wuhan University all preserved and continued the main axes of their modern-era planning. In modern university planning, the emphasis on ritual space as the main axis reflects a convergence of Chinese and Western concepts. The “ritual” space evolved from temples used for sacrificial functions to auditoriums designed for large-scale, secular activities. In contemporary university construction, the auditorium, combining both ceremonial and leisure functions, has become a central architectural element that is indispensable to university campuses.

After numerous collisions of planning ideologies, domestic scholars chose to preserve not only the open landscape layout of Western universities but also the landscape layout of ancient Chinese academies, while innovating the layout of university planning. These models, which represent variations of the traditional academy design, emerged from explorations in modern university space planning and serve as new ecotypes formed through cultural hybridization. After the founding of New China, planners further diversified campus spatial forms based on these hybrid foundations. The sustainability of cultural hybridity lies not in adherence to a single tradition but in the creative reinterpretation of spatial codes by active agents. In contemporary campus planning practice, it is essential to establish a mindset of dynamic evolution and innovation. Rather than merely replicating axial symmetry and courtyard enclosures from traditional architecture, planners should focus on adaptive spatial translation. For instance, the core value of the Piyong (imperial lecture hall) does not lie in its circular physical form, but in its function as a ritualized space for knowledge exchange. Planners may reinterpret this spatial spirit into flexible cultural corridors—arc-shaped public walkways that connect clusters of teaching buildings.

(2) The decline and revival of university spirit after cultural hybridity

Historical practice shows that cultural collision can inspire creativity and drive social progress, but it also comes with certain costs, and the concept of cultural hybridization should not be overly glorified (Chen 2018). The traditional Chinese education model emphasizes the transmission of value-based knowledge, and the corresponding architecture of the academy creates a “scenario” that evokes specific emotions (Zhang 2005). In contrast, Western rational academic thinking—characterized by geometric composition and clearly defined functional zones—aligned with the requirements of the Republican government’s “Party education”. While this orientation facilitated the rationalization and scientization of Chinese universities, it also disrupted the immersive and emotionally engaging educational environments of traditional models. The planning model adopted by universities has often prioritized grand spatial narratives, resulting in the separation of living and learning, teaching and learning, and insufficient attention to human-scale considerations (Xiang 2007).

Despite the complex and pluralistic value systems of modern China, many universities successfully cultivated distinct cultural spirits, which continue to define their identities today as century-old institutions. Tracing the process of cultural hybridity reveals that their spiritual transformation was achieved through dynamic balancing of tradition and modernity, as well as local and global influences. In terms of educational philosophy, Confucian ethics and Western scientific rationality were creatively integrated. Cai Yuanpei’s advocacy for “freedom of thought and inclusiveness” combined the Confucian ideal of moral self-cultivation with Western notions of academic freedom. His “fivefold education” (moral, intellectual, physical, esthetic, and labor education) emphasized the full development of student individuality. Meanwhile, instead of wholly adopting Western models, educators such as Zhang Boling at Nankai University initiated “localization reforms” (tuohuohua), achieving a dialectical unity between global theories and local experiences. These educational ideologies also influenced campus planning and were reflected in spatial forms.

In the construction of modern universities, axial layouts and courtyard structures became key mediums of cultural translation. These spatial elements carried the logic of Western knowledge production while simultaneously preserving the emotional continuity of traditional education through transitional “grey spaces.” However, under the influence of shifting political, economic, and cultural conditions, contemporary university planning often fails to reflect its unique institutional spirit. Standardized classroom buildings replicate the physical spaces of knowledge production but lack the flexibility required for free academic exploration. Mechanistic functional separation enhances efficiency but disrupts the immersive continuity needed for moral and character development. Addressing this dilemma requires flexible spatial strategies in emerging projects. Avoiding mechanistic zoning, planners should pursue spatial integration and permeability to support freer academic engagement. For example, on the physical level, breaking the boundary between residential and academic zones—such as adding discussion nooks in dormitories or linking dining halls to makerspaces—can foster informal knowledge exchange. On the spiritual level, moral education can be materialized through perceptible spatial narratives—for instance, installing “dialogue corridors” with sages’ quotations in public spaces or embedding discipline-themed sculptures along campus axes. This “pedagogical spatiality” not only continues the traditional wisdom of environment-based education but also creates an integrated narrative that merges academic freedom with ethical cultivation.

(3) Reflections on the value conservation of university space heritage in contemporary city

The transformation of spatial forms in modern Chinese universities vividly illustrates the dynamic process of cultural hybridization between China and the West, bearing witness to their exchange in education, planning, and architecture. In the context of modern society, university land acquisitions and new building constructions are among the most extensive construction activities of the time (Wang and Zhang 2017). Unlike other modern construction efforts, these activities are more systematic. Modern Chinese university architecture reflects the transformation of Chinese architectural style, and the evolution of its spatial form reflects the history of modern campus planning. Moreover, they built in the suburbs laying the foundation for the development of urban suburban space and even affected the suburban spatial structure. In some cases, examining the evolution of university spatial forms during the modern era can help explain the early development of suburban space, offering meaningful historiographical value.

The core value of modern university heritage lies not in any fixed or essentialized identity, but in the hybrid processes through which it was historically produced. Contemporary heritage conservation should resist static approaches—such as reducing “Chinese-style axial layouts” or “Western-style domes” to simplified symbols of identity—and instead emphasize how these spatial forms are continually reshaped by multiple actors over time. The objective of conservation is not to restore an imagined “authenticity,” but to sustain the dynamic hybridity embedded in university spaces. In contemporary conservation, it is more important to focus on how space can continue to generate and reflect the spirit of the university, rather than attempting to preserve it as fixed in one historical period.” For instance, campus auditoriums—once seen as symbols of “cultural colonization”—can now serve as multifunctional public venues that host both graduation ceremonies and student debates, thereby activating the spatial potential for the university spirit to renew itself through practice. The cultural heritage embedded in modern campus construction should, in the contemporary context, go beyond merely serving faculty and student needs. Its broader public value must be recognized, transforming university spaces into urban cultural platforms that ensure the continuous revitalization of heritage.

Static conservation may not sufficiently reflect the evolving meanings of modern university campuses. These campuses are not fixed historical sites, but living spaces that have developed over time and still serve important roles today. Dynamic conservation should be seen as a basic approach to protecting the spatial heritage of modern universities. The goal is to sustain the cultural spirit of modern universities in contemporary contexts. Compared with static restoration or the preservation of individual buildings, this approach emphasizes the spatial logic of transformation and the contemporary expression of historical meanings. It offers a more effective response to the hybrid and continuously evolving nature of modern university spaces. The main principles of this approach include: the preservation and revitalization of the historical axis of the campus; the continuation of the scale of public spaces and the idea of “pedagogical spatiality”; the holistic protection of architectural heritage and the comprehensive utilization of its functions.

However, much of China’s modern university heritage is preserved in the form of historical building groups on conservation lists. This type of protection tends to focus on individual structures, often neglecting the overall layout. The value inherent in the spatial organization and structure has not been adequately recognized. More attention should be given to the integrated and dynamic conservation of modern university spatial heritage. For example, the designation of the historical and cultural district of Shandong University’s western campus (formerly Qilu University) as one of Shandong Province’s 35 historical and cultural blocks is considered a pioneering move. This approach not only aids in the comprehensive preservation of modern university spatial forms but also helps safeguard the spatial characteristics that embody the spirit of the modern university.

This study selected 25 research samples based on the availability of relatively complete historical records and campus planning documents. However, the total number of modern universities during this period far exceeds the scope of this selection. Therefore, the research results may not fully reflect the diversity of all modern universities in terms of spatial and ideological development. In addition, while the study attempts to examine the influence of multiple actors beyond mainstream historical events on university construction, the limited availability of non-official and grassroots sources poses certain challenges. Future research can expand the scope of university samples and further clarify the multiple social forces involved in modern Chinese campus construction based on oral history, local chronicles, etc., to provide a richer perspective for interpreting university architectural heritage in the context of globalization.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Bhabha HK (2012) The location of culture, 2nd edn. Routledge

Burke P (2009) Cultural hybridity. Polity

Burke P (2016) Hybrid renaissance: culture, language, architecture. Central European University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctt1d4txq4

Chen C (2007) Christian universities and the transformation of Chinese modern architectural form. Jinan J Philos Soc Sci 29(6):8

Chen J (2018) The concept of ‘hybridity’ and Peter Burke’s study of cultural history. Historiography Bimonthly (2): 74−84+159

Chen X (2008) The evolution of Chinese university. Doctoral dissertation, Tongji University, Shanghai

Chu J (2005) Post colonialism research and the selection of educational development strategy in China. J Univ Sci Technol Beijing Soc Sci Ed (04):8−11

Chu Z (2004) What is the source of Chinese university spirit. Jiangsu High Educ (4):2–5. https://doi.org/10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2004.04.002

Chu Z (2013) The spiritual history of modern Chinese universities. People’s Education Press

Clark BR (1984) Perspectives on higher education eight disciplinary and comparative views. University of California Press

Dai J (2008) The research on modern educational architecture in Wuhan. Doctoral dissertation, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Dober RP (1963) Campus planning. Rheinhold

Dober RP (1991) Campus design. Wiley

Dober RP (1996) Campus architecture: building in the Groves of Academe. McGraw-Hil

Dong L (1998) Research on the architecture of Chinese church university: the intersection of Chinese and Western architectural culture and the composition of architectural form. Zhuhai Publishing House

Duara P (1996) Rescuing history from the nation: questioning narratives of modern China. University of Chicago Press

Duara P (2004) Sovereignty and authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian modern. Rowman & Littlefield

Feng G, Lv B (2016) Chinese modern university campuses under the integration of Chinese and Western cultures. Tsinghua University Press

Feng L (1998) Postcolonialism and its repercussions in China. Foreign Lit (01):67–76. https://doi.org/10.16430/j.cnki.fl.1998.01.015

Hong Y (2016) Shanghai College: an architectural history of the campus designed by Henry K. Murphy. Front Archit Res 5(4):466–476

Hu S (1994) Selected works on Hu Shi’s educational theory. People’s Education Press

Huang W, Lin G, Ren J (2021) Evolution of campus axis spaces and the cultural construction of Lingnan University. South Architecture (05):71−76

Jaspers KR (1961) Die idee der Universität. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg

Kong S, Bai X (2011) Ancient Chinese academy of architectural form: our Chinese academy of ancient case. Huazhong Archit 29(7):177–180. https://doi.org/10.13942/j.cnki.hzjz.2011.07.005

Li X, Pan F, Chen G (2014) The research on the derivation of architectural patterns of the folk academies impacted by official trend in Hubei and Hunan provinces. South Architecture (05):58−63

Liu W (2019) Luojia architecture record: the birth of a new campus for a modern national university. Guangxi Normal University Press

Liu Y (2014) Building Guastavino dome in China: a historical survey of the dome of the auditorium at Tsinghua University. Front Archit Res 3(2):121–140

Lou Y (2016) The fundamental spirit of Chinese culture. Beijing Book Co. Inc

Luo S (1984) The evolution of Tsinghua University campus architectural planning (1911−1981). N Archit (04):2–14

Lv B (2002) Principles of spatial sustainable growth and planning methodology of campus. City Plan Rev (05):24–28

Ma Q (2002) Western education ideology and campus architecture: tracing the original new campus architecture. Time Archit (02):10−13

Mayer FW (2015) A setting for excellence: the story of the planning and development of the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. University of Michigan Press

O’Shaughnessy AJ (2021) The illimitable freedom of the human mind: Thomas Jefferson’s idea of a university. University of Virginia Press

Qiu Y (2006) Study on education architecture of Chongqing. Master’s thesis, Chongqing University

Republic of China (2006) National capital design and technology commissione’s office: the city plan of Nanking. Nanjing Publishing House

Said EW (2012) Culture and imperialism. Vintage

Shang Y (2010) Academy culture and construction in college campus of China. Master’s thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology

Shen F (2017) History of Sino western cultural exchange. Shanghai People’s Publishing House Co., Ltd

Sun J (1995) Western learning, western education, modernization: reflections on Christian universities in China and related issues. J East China Norm Univ Humanit Soc Sci (02): 9-13+60. https://doi.org/10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5579.1995.02.002

Teng Y (1980) Church universities in old China. Jilin Univ J Soc Sci Ed (02):83−87

Turner PV (1984) Campus: an American planning tradition. Architectural History Foundation; MIT Press

Wang H (2018) Study of educational architecture in early-modern Nanjing (1840-1949). Doctoral dissertation, Southeast University

Wang J, Zhang S (2017) History of higher education institution: selected papers on the history of modern Chinese universities. Tianjin University Press

Wang L, Wang D, Pan Z (2021) Towards world-class universities: from campus planning and design. China Architecture & Building Press

Wang N, Sheng A, Zhao J (2011) Seeing the east again: postcolonial theory and thought. Chongqing University Press

Wang S (2008) An analysis of the connotation, characteristics and functions of university culture. China High Educ Res (05):66–67. https://doi.org/10.16298/j.cnki.1004-3667.2008.05.016

Wang Y, Zhou D (1986) Educational history of modern in China. Hunan Education Press

Wei C, Xu H, Lu J (2012) Heterogeneous isomorphism: from Yuelu academy to Hunan University. Archit J (03):6−12

Wei L (2006) The connotation of bifurcated history paradigm in Prasenjit Duara’s Chinese nationalism study. Guizhou Ethn Stud 6:75–80

Wen T (2015) Constitution patterns’ research of the campus space based on the culturing of university spirit. Doctoral dissertation, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an

Wu L (2011) The realistic dilemma and construction strategy of Chinese university model. China High Educ Res (03):5–8. https://doi.org/10.16298/j.cnki.1004-3667.2011.03.009

Wu L (2020) A historical reflection on Chinese modern university’s cultural character and lts contemporary significance. Jiangsu High Educ (2):15–22. https://doi.org/10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2020.02.003

Wu X, Liu S, China Jiao yu bu (1971) The first China education yearbook. Zhuan ji wen xue chu ban she

Xiang K (2007) The retrospect and prospect of contemporary university campus construction. Urban Plan Forum 1:66–70

Xiang X (1999) The postcolonial condition and comparative education. J Beijing Norm Univ Soc Sci 3:5–13

Xu W (1986) Research on modern Chinese university campus. Master’s thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing

Xue T (2005) The research of modern architecture in Shanghai Jiaotong University (1896-1949). Doctoral dissertation, Zhejiang University

Young RJ (2005) Colonial desire: hybridity in theory, culture and race. Routledge

Zhang W, Chen Q (2021) Research on the female’s spatial characteristics in the changing social context: a case study of modern universities. Mod Urban Res 36(3):6

Zhang Y (2005) Knowledge form with university architecture. Doctoral dissertation, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China [grant number 23VJXT019].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang Luyuan contributed to the conceptualization of the study, methodology development, formal analysis, data curation, and drafted the original manuscript. Liu Rui supported the methodology and formal analysis and provided data support. Wang Zhibo, Zheng Yingliang, and Ye Zhaoyi conducted investigations and contributed to writing the original draft. Tao Jin contributed to the overall conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and drafting of the manuscript, as well as reviewing and editing. Tao Jin also acquired funding, supervised the project, and managed the administration of the research. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Liu, R., Wang, Z. et al. Cultural hybridity and ideological shifts: shaping the campus space of modern Chinese universities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1510 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05781-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05781-0