Abstract

E. coli chaperonin GroEL forms nano-cages for protein folding. Although the chaperonin-mediated protein folding mechanism is well understood, the role of the conserved glycine and methionine-rich carboxy-terminal residues remains unclear. Bacteria with multiple chaperonins always retain at least one paralogue having the gly-met-rich C-terminus, indicating an essential conserved function. Here, we observed a stronger selection pressure on the paralogues with gly-met-rich C-termini, consistent with their ancestral functional importance. E. coli GroEL variants having mutations in their C-termini failed to functionally replace GroEL, suggesting the functional significance of the gly-met-rich C-termini. Further, our structural modelling and normal mode analysis showed that the C-terminal region shuttles between two cavity-specific conformations that correlate with the client-protein-binding apical domains, supporting C-termini’s role in client protein encapsulation. Therefore, employing phylogenetic, genetic, and structural tools, we demonstrate that the gly-met-rich C-termini are functionally significant in chaperonin-mediated protein folding function. Owing to the pathogenic roles of the chaperonins having non-canonical C-termini, future investigations on the client protein selectivity will enable understanding the disease-specific client protein folding pathways and treatment options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The bacterial chaperonin GroEL, with its cofactor GroES, constitutes an essential molecular machine for cellular protein folding in E. coli, and homologues exist in nearly all organisms1,2,3,4. GroEL forms a double toroidal tetradecamer of −900 kD, which has two solvent-filled cavities, one in each heptameric ring5,6. Extensive investigations have dissected the structure-function relationships of GroEL’s domains7,8,9 and the movements that they undergo during the ATP-driven cycles of client protein binding, encapsulation, folding, and release3,10. Although the GroEL cavities enable client protein folding, the precise role of the cavity is still debated1,3,4,11. Some models proposed that the cavities play an active role in enhancing the folding of the encapsulated client protein4,7,12, while others propose that the cavity acts as a passive receptacle13,14. Although chaperonin-client interactions have been attributed to the hydrophobic patches in the cavity rim1, a complete understanding of the mechanism by which client proteins are internalized and expelled post-folding is lacking.

The terminal 23 amino-acid residues of GroEL, which end with a highly glycine-rich peptide ((GGM)4M), are not resolved in crystal structures of the GroEL complex, suggesting that they are either disordered or exhibit a range of possible structures even when the protein is crystallised. Structural models of E. coli (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/P0A6F5) and Bacillus subtills (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/P28598) GroELs generated by the AlphaFold show extended carboxy termini. These models considered monomeric forms, not the energy-efficient oligomeric single-ring or bullet forms. The extended conformation of the carboxy termini would cause steric hindrance when monomers assemble into single or double ring conformations. In this paper, we refer to this terminal 23-amino-acid residue part of the protein as the carboxy terminal segments (CTSs). Crystal structures show a possible opening at the bottom of the cavity that could suggest that the two cavities are connected5,6. However, cryo-electron microscopy and SANS both demonstrated electron density at the base of the cavity, which would prevent client protein movement between the two heptameric rings, and it is generally agreed that this density arises from these CTSs15,16. This region becomes more ordered when ATP is bound17. Cryo-EM structures of a complex representing an early intermediate in protein encapsulation showed significant association between this C-terminal region and the bound client protein, implying that this region may have a role in the internalization of the client proteins18. Moreover, analysis of the folding of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in a single ring version of GroEL lacking the CTS suggested that denatured but not folded GFP could leak out from the bottom of the GroEL cage19, consistent with structural data showing that the CTS normally forms a barrier between the two cavities. Thus, the CTS may have multiple roles in the GroEL folding cycle, both in binding and internalizing client proteins and in preventing their leakage from the equatorial ends of the heptameric rings.

Genetic and biochemical studies have also analysed the role of this region. Exchanging CTSs between chaperonin homologues from organisms with different optimal growth temperatures has demonstrated that the CTS could act as a thermometer for group I20 and group II21,22 chaperonins. In contrast to the above findings, genetic studies in E. coli that demonstrated that GroEL can function without the terminal sixteen23 or twenty-seven residues24,25 suggest that the CTS is dispensable for chaperonin function. GroEL with a C-terminal deletion of 27 amino-acids was reported to support the growth of a groEL Ts mutant, bacteriophage morphogenesis, and growth of a groEL deletion strain, though this required high levels of the truncated GroEL24. GroEL with a further single amino-acid deletion failed to complement and was shown to be assembly deficient14,25.

Biochemical studies on a range of purified truncated GroEL molecules showed that deletion of the 23 C-terminal amino-acids caused reduced ATPase activity and chaperone activity with a range of client proteins. However, shorter deletions of seven or seventeen amino acids had very little effect on these properties26. Furthermore, GroEL variants with extended C-terminal segments showed client and extension size-specific variations in folding rates. These observations have been attributed to changes in either the cavity volume7,12 or ATPase activity13, suggesting that the GroEL C-terminus plays an important role in modulating the chaperonin reaction cycle12,13. Recent structural and biochemical studies have suggested that the CTS might form a sieve between the cavities19,27 and interact with client proteins, favouring their unfolding18,28,29. The fact that chaperonins tagged at the carboxy terminus with a hexa-histidine tag bind to Ni-NTA resin, as reported in several studies aimed at purifying chaperonin tetradecamers30 or the complex with bound co-chaperonins31, implies that the CTSs can reach close to the cavity rim, at least in the GroES-free trans ring, as this would be required to enable the (His)6 tag to bind to the Ni-NTA resin. Molecular dynamic simulations32 and predictive structural studies also show that the CTSs might reach the cavity rim and sometimes extend out of the cavity. Taken together, these studies suggest that the CTS plays an important role in GroEL-mediated protein folding by binding to the client proteins and exhibiting multiple conformational states. However, how the CTS contributes to GroEL’s function remains unclear. Therefore, we reevaluated the function of the CTS.

To understand CTSs’ functional relevance, we examined their conservation. The CTS of type I and type II chaperonins were observed to be highly conserved, with the variation usually in the number of repeating GGM motifs33,34. However, some CTSs in the bacterial chaperonins, especially multiple chaperonin genes in the same species, were observed to deviate from the gly-met-rich composition. Examples of bacteria encoding multiple chaperonin genes include several proteobacteria (with Bradyrhizobium japonicum encoding seven chaperonin genes), Cyanobacteria, and Actinobacteria2,3. The proteobacterial and cyanobacterial chaperonin CTSs were either gly-met-rich or pattern-free, while the actinobacterial CTS exhibited distinct divergence in their composition, encoding histidine-rich, glutamine-rich, or pattern-less CTSs2,35,36. Interestingly, the paralogues with a gly-met rich CTS were often observed to be essential, while others were often dispensable2,37, suggesting an essential role for gly-met-rich CTS.

Here, we report investigations into the function of the chaperonin CTS. A phylogenetic analysis of 325 chaperonin sequences demonstrates that the CTS is likely to be a functionally significant part of chaperonins. To test this, we constructed and analysed a series of E. coli GroEL CTS variants and used normal mode analysis to study the possible confirmations of the CTSs in the E. coli GroEL oligomer. Our results suggest that CTSs are likely to assume cavity-specific conformations that coordinate with the motions of the apical domains, consistent with the proposed roles for CTSs in client-recognition and encapsulation.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis suggests functional relevance of chaperonin CTSs

About 30% of fully sequenced bacterial genomes encode multiple chaperonin genes2,3,38, with the majority of such examples belonging to actinobacteria. In the actinobacteria, one chaperonin paralogue has the gly-met-rich CTS, while the other paralogues have CTSs with different amino acid sequences, suggesting that the deviation in CTS composition is likely to be evolutionarily driven with an organism-specific relevance. Therefore, we examined the diversity of the chaperonins among 325 actinobacterial chaperonin paralogues. Chaperonin polypeptide sequences were retrieved from the UniProt database, and their meta data was sourced from literature (Supplementary data 1). The phylogenetic relationships of the full-length chaperonin polypeptide sequences were inferred using a neighbour-joining algorithm. In the resulting polynomial-time phylogenetic tree, the chaperonin sequences are grouped into three clades (Fig. 1a and S1). Interestingly, this classification is largely based on the chaperonins’ CTS composition; the three clades largely contained chaperonins having a) the classical gly-met-rich CTS, b) Histidine-rich CTS or c) pattern-free CTS (Fig. S1). The chaperonins in the gly-met-rich group exhibit shorter branch lengths than the his-rich group (Fig. S1), showing higher conservation of the former. This correlates with the observation that the chaperonins in the gly-met-rich group are largely essential, as this would lead to higher selection pressure and, hence, lower divergence39,40. The chaperonins in the third group exhibit greater divergence and may represent independent acquisitions by horizontal gene transfer, as most actinobacteria only have two chaperonin genes41 (Fig. S1). Our analysis is consistent with the hypothesis of an ancient chaperonin gene duplication in an ancestral actinobacterium followed by functional specialisation3,39.

a Phylogenetic relationships between 325 actinobacterial chaperonin sequences were inferred using a neighbourhood-joining algorithm and presented as a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree shows three clades. The yellow-coloured branch represents the E. coli GroEL sequence, which was included in the alignment. b Site specific conservation rates were calculated using ConSurf’s Rate4Site algorithm from the multiple sequence analysis and mapped onto E. coli GroEL sequence. The graph represents the normalized conservation scores (lowest score represents conservation, with a standard deviation of one) as a function of GroEL’s primary sequence. The domain regions of the equatorial (E), intermediate (I) and apical (A) domains and the CTS region (C) are indicated. c Sequence Logo depicting the diversity in the CTS region of the actinobacterial chaperonins, starting with the conserved Proline. d Scatter plot showing hydrophobicity of the chaperonin CTSs (GRAVY Scores) as a function of their average charges (pI). Each dot represents one CTS and the spots are colour coded in the same way as the three branches in the phylogenetic tree. A detailed phylogenetic tree with taxon names and node ages is presented in the supplementary information.

To test if the principal variation among the analysed chaperonin sequences was in their CTS regions, we used the full-length sequences of the chaperonins and calculated the residue‐specific divergence rates, using the rate4site algorithm41 and EMBOSS Cons. The resultant rates were mapped onto E. coli GroEL (Fig. 1b). As expected, the substrate binding helices H and I, residues involved in ATP binding hydrolysis (D52, D87 and D393), and a majority of the intermediate domains and inter-domain boundaries showed higher conservation with a divergence score close to zero, while the loop between helices N and O and flexible regions of apical domain showed lower conservation. Interestingly, the CTS showed high divergence compared to the rest of the sequence (Fig. 1b). EMBOSS Cons, which derives consensus sequence from an MSA, also showed CTS divergence (Fig. S2), in agreement with the Rate4Site analysis. This is consistent with a significant contribution of the CTS to the divergence in the chaperonin sequences, as observed in the sequence logo (Fig. 1c). To examine this further, we compared the residue-specific distance matrices of the full-length sequences with the CTS regions. The CTS regions showed higher overall divergence than the full-length sequences (Supplementary Data 2), indicating that much of the divergence in the chaperonins was contributed by the CTS regions.

We further analyzed the diverse actinobacterial CTS by plotting their average hydrophobicity (GRAVY) as a function of their charge (pI). Most of the CTS fell into one of three groups. The first group constitutes the gly-met-rich CTSs; these are tightly clustered with a mean pI around 4 and a GRAVY score between about 0.7 and -1.5. The second group constitutes charged-residue CTSs, which are relatively more dispersed with pI between 3 and 8 and a lower GRAVY score. The third group constitutes the pattern-free CTS, and these have variable hydrophobicity (Fig. 1d). The relative clustering of the first and second groups confirms that, as expected, the CTS’s physico-chemical properties largely agree with their phylogenetic relationships.

The GroEL carboxy terminus has an essential role in chaperonin function

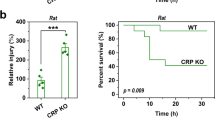

As the observations above suggested that the CTS may be important in chaperonin function, we tested the ability of a GroEL variant that lacks the thirteen-residue C-terminus (GroELΔC13) to functionally replace full-length GroEL. We tested this using a groEL deletion strain, AI9042, wherein the chromosomal groEL gene is replaced with a kanR cassette and groEL is expressed from a lactose-inducible Plac promoter in the shelter plasmid, pTGroEL7 (Camr, p15A Ori). Therefore, AI90 can lose the shelter plasmid, and become chloramphenicol sensitive only if the vector-borne chaperonin variants are functional. AI90 was transformed with plasmids expressing either GroEL or GroELΔC13 genes from a lactose-regulated promoter in the plasmid pTrc99A, and from an arabinose-regulated promoter in the plasmid pBAD24. The chloramphenicol sensitivity of the respective strains was assessed by serial dilution following the induction of the promoters regulating the vector-borne groEL variants. We observed that only the strains producing the full-length GroEL were able to lose the shelter plasmid and become chloramphenicol sensitive (Fig. 2a). As this method involved screening for the loss of resistance, and hence rare events would be hard to detect, we further attempted to P1 transduce the DgroEL::kanR marker from AI90 into E. coli MG1655 harbouring the plasmids encoding the same groEL CTS variants. The strain producing GroELwt formed kanR colonies at high frequency, but those producing GroELΔC13 failed to produce any kanR colonies.

The ability of groEL lacking the 13 c-terminal residues to functionally replace groEL was assessed in (a) the groEL deletion strain AI90; (b) the conditional expression strains LG6 and MGM100 and (c) temperature-sensitive strains groEL44 and groEL100. Serially diluted cultures of the indicated E. coli strains expressing either the wildtype (W) or the 13 residue carboxy termini lacking groEL variant GroELΔC13 (Δ) from a plasmid, or the vector only control (V), were spotted on LB agar plates supplemented as indicated. All the plates in a and b were incubated at 30 °C, while the plates in c were incubated at the indicated temperatures. The first and second plates in b and c represent permissive and restrictive growth conditions, respectively. Relevant genetic features of the strains in a and b are depicted schematically. In AI90, groEL has been replaced by the kanR cassette while a functional copy, regulated by lactose inducible Plac promoter, is provided on a shelter plasmid pTGroEL7 (p15A, camR). The ability of the incoming indicated groEL variants to allow loss of pTGroEL7 was assessed. In LG6 and MGM100, the chromosomal copies of the bicistronic groE operon are controlled by lactose-inducible Plac and arabinose-inducible PBAD promoters, respectively.

As this result was different to that reported previously24,25, we further assessed the function of GroELΔC13 in two groEL depletion strains, E. coli LG614 and MGM10043, wherein the chromosomal groESL operon is regulated by Plac and PBAD promoters, respectively. GroELΔC13 was expressed in E. coli LG6 from pBAD24 and in MGM100 from pTrc99A. Growth of the respective strains was assessed by serial dilution following repression of the promoters regulating the chromosomal groESL operon. GroELΔC13 rescued the growth of LG6, but not of MGM100 (Fig. 2b). The PBAD promoter that controls the expression of the groESL operon in MGM100 is known to be more tightly repressed than the Plac promoter in LG643,44, so this difference probably arises from weak expression of the chromosomal groEL gene in LG6, but not in MGM100. We confirmed this using reverse transcriptase PCR (Fig. S3).

To further assess if GroELΔC13can independently function as a chaperonin, we investigated its ability to complement two strains that carry temperature sensitive (Ts) groEL alleles, SV2 (groEL4445) and A7579 (groEL10046), which encode Ts chaperonin variants, GroEL E191G and S201F, respectively. GroELΔC13 was able to rescue the Ts phenotypes of these strains at their non-permissive temperature (Fig. 2c).

Taken together, these observations show that GroELΔC13 retains partial function, which can enable growth when sufficient full-length GroEL is present in the cell, even if it is at lower levels (as in LG6) or itself only partially functional (as in SV2 and A7579). However, when GroEL is present at too low levels (as in MGM100) or is absent (as in AI90), GroELΔC13 is not able to support growth. We therefore predicted that it would be impossible to delete the groEL gene from a strain only expressing GroELΔC13.

The CTSs exhibit correlated motions with the apical domains during the chaperonin cycle

Having established that the CTS regions are essential for chaperonin function under the conditions of our assay, we wished to study the structure and movement of the CTSs within the GroEL tetradecamer. In lieu of detailed structural information5,6, we used in silico approaches to study CTS dynamics. The suitability of these methods for studying GroEL dynamics was assessed by checking for their consistency with experimental findings (Supplementary Results). Structural models of GroEL protomers (one from each ring) with (GGM)4M carboxy terminus were generated using Modeller and COOT. Models with the lowest energy were selected and superposed to obtain GroEL tetradecamers (Fig. 3a) with a cis ring in the relaxed (R”) conformational state) and a trans ring in the tight (T) conformational state) ring (Fig. 3a). In these models, the CTSs assume cavity-specific conformations (Fig. 3a, b), similar to those seen in cryo-EM structures47, filling the void at the base of the cavities (Fig. S4). Since GroEL shuttles between T and R” states during its functional cycle48, we employed Normal Mode Analysis to generate successive states of structural intermediates to map the path taken to traverse between T and R” states. Large dynamics of the CTSs that were observed in the protomer (that are −4–10 times stronger than averaged atomic displacements in the rest of molecule (Fig. S5)), were both reduced (Fig. S6) and synchronized (Fig. S7) in the heptameric ring. In other words, the ring arrangement of protomers in GroEL restricts the dynamic movements of the CTSs. Major structural changes during the transitions were observed only in the apical domains and the CTSs (Fig. S5 and 6), consistent with both being functionally important and, in agreement with the hypotheses proposed earlier29, potentially linked.

a Molecular model of asymmetric GroEL-GroES complexes showing filling of the void by CTSs (red space filled). GroEL and GroES are in pale-blue and pink, respectively. One GroEL subunit in each ring is colour-coded to make the change in domain architecture easier to visualise. A, I and E represent apical, intermediate, and equatorial domains, respectively. b Conformational snapshots showing the series of conformations visited by the GroEL heptamer during transition from the T to the R” state. Domains in all the subunits are colour-coded as in (a). Two subunits were removed in the display to reveal the dynamics of CTSs inside the cavity. c Bottom view of the cavity showing the gradual opening of the aperture during the transition, and the dynamic movement of the CTSs. d Cartoon representations of single subunits from the two heptameric rings of GroEL in T and R” conformational states that were subjected to NMA. The rotation and transition of the CTSs are indicated. The helices F, H, I and M are indicated as αF, αH, αI and αM, respectively. e Residue level fluctuations in the torsion angles and displacements of alpha carbon atoms. Fluctuations in the indicated angles and displacements with respect to the T state that were calculated for all seven subunits were averaged and plotted as a function of the primary structure of a subunit. E, I, A, and G represent the regions of GroEL primary structure spanning the corresponding domains as colour-coded in the molecular model. The bold lines mark the regions and are scaled according to the size of the indicated helices.

To investigate the extent of the functional synchrony between the en bloc movements of the apical domains and the dynamics of the CTSs, correlations between the conformational paths taken up by these two segments were mapped using an elastic network model, PATH-ENM49. This showed that during the transition, the GroEL heptamer traverses through the known nucleotide-driven conformational intermediate states such as the R and R’ states (Fig. 3c and Movie S1). Similarly, the CTSs visited several conformational states, from the rim to the base of the cavity, (Fig. 3b), which triggered gradual opening of the aperture at the bottom of the cavity (Fig. 3c). These observations suggest that the two cavities are partitioned by the CTSs. Interestingly, in agreement with the known motions of the client-binding apical domains, the CTSs exhibited a positively correlated set of large and dynamic conformational transitions with an overall 70° rotation and 45 Å transition, although the constituent equatorial domains remained largely immobile (Fig. 3d and Movie S1). Further, the majority of the fluctuations in the torsion angles φ, ψ and α, and the movement of α carbon atoms calculated at every transition from the T state, were observed mostly in the apical domains and the CTSs regions (Fig. 3e), with a perfect anti-correlated motion being observed between these two segments (Fig. S7b), suggesting that they move into the cavity while GroEL moves from the T to R” state and vice versa (Movie S1). Although the helices H, I, F and M showed characteristic en bloc movements while they traversed large molecular distances, the CTSs exhibited dramatic movements as observed by the large fluctuations in all its torsion angles (Fig. 3e). Taken together, these observations support a mechanism where the CTSs exhibit large fluctuations in position that are correlated with the movements of the apical domains, consistent with the hypothesis that these two segments function in synchrony in client recognition and binding.

Hydrophobicity and flexibility are critical in E. coli GroEL’s Gly-Met rich C-terminus

As dynamic fluctuations appear to be a hallmark of the CTS from the analysis above, we next looked at the impact of altering the flexibility of the C-terminal regions. This was done both in silico and experimentally by replacing the glycine residues in the CTS with either alanine or proline. We also examined the effect of altering the hydrophobicity of the CTS, as this may have a role in the potential interactions with client proteins50,51. This was done by replacing all the methionine residues with aspartic acid. The resulting GroEL CTS variants, with (AAM)4M, (PPM)4M, or (GGD)4D CTSs, were modelled and subjected to NMA, as described above for the wild-type GroEL. The dynamics of the full-length proteins were largely similar to the wildtype molecules (Fig. S8). However, correlated dynamics of the CTS regions in these variants showed substantial deviations from the wildtype (Fig. 4a). Interestingly the three variants showed distinct dynamics in agreement with their flexibility and charge (Fig. 4a). The wildtype (GGM)4M and (GGD)4D tails, being flexible sequences, showed diffused dynamic patterns. However, the negative charge introduced by the aspartic acid in (GGD)4D, unlike the hydrophobic attraction in the wildtype (GGM)4M, appears to have resulted in repulsion within the carboxy termini, which is reflected in the increased dynamics and correlation. The alanine in (AAM)4M tails appears to have brought in rigidity to the structure, which is reflected in losing the positive coordination between the subunits. Likewise, the (PPM)4M showed higher rigidity and lower positive correlation (Fig. 4a).

a Pairwise correlation matrices showing differential displacement of the indicated 13 residue carboxy-terminal peptides of the GroEL CTS variants that are shown and colour-coded as in Fig. S6. A to G indicate the subunit chains in the heptameric ring. b Serially diluted cultures of groEL conditional mutant strains, E. coli LG6 and E. coli MGM100 that are expressing the indicated groEL CTS variants, were spotted on LB agar plates. The plates were supplemented as indicated and incubated at 30 °C.

Since alteration in the dynamic motions could be functionally significant, we engineered each CTS variant into GroEL and tested the resultant GroEL CTS variants for their ability to replace groEL in E. coli LG6 and E. coli MGM100. None of the three GroEL CTS variants rescued E. coli MGM100 under restrictive conditions, while all the variants rescued E. coli LG6 (Fig. 4b). This is the same phenotype as is displayed by GroELΔC13 and suggests that variations in the CTS that alter either hydrophobicity or flexibility have a similar effect on chaperonin function as that caused by complete loss of the CTS. This supports the hypothesis that the composition of CTS is critical to its function, consistent with its high conservation in house-keeping chaperonins.

In summary, the C-terminal segments were observed to assume cavity-specific conformations correlated to the apical domain conformations. This would enable these hydrophobic and structurally flexible CTS to bind and internalize the partially folded (molten globule-like) client proteins via their exposed hydrophobic surfaces (Fig. 5), in agreement with other observations18,19. Variations in the CTS that alter flexibility or hydrophobicity adversely affected their role in chaperonin function, suggesting the importance of these features in the C-terminus.

Discussion

GroEL-GroES mediated protein folding generally requires the formation of a tetradecameric double ring assembly that encloses two isologous cavities for encapsulating client proteins1,4,38, although some chaperonins can function as heptameric single rings52,53,54. Although the structural changes and functional contributions of the apical, intermediate and the equatorial domains to the chaperonin cycle have been established, the precise role of CTS remains contentious. Previous work suggested that the C-terminal twenty-seven amino acids were dispensable23,24,25. However, the extremely high conservation of the CTS3,12,33, together with recent in vitro data suggesting an important role in client protein encapsulation and possibly unfolding18,28,29, led us to re-examine this question using a combination of genetic and structural approaches.

Moreover, paralogues with atypical CTSs have often been demonstrated to be functionally distinct, adopting organism-specific roles which in some cases contribute to pathogenicity3,22,55,56,57. This suggests that the gly-met rich CTS may be a feature of chaperonins with a broader client range and a general function in protein folding. These chaperonins therefore appeared to have encountered tighter selection pressure in our phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). However, the chaperonins which have different C-termini are likely to have evolved to have more specialized roles2,3,56. Interestingly, although the Mycobacterial chaperonins having His-rich CTS have been shown to exist as lower oligomers58 and thus could not functionally replace E. coli GroEL59, a mutant lacking 18 C terminal residues has demonstrated enhanced ability to assemble into higher order oligomers60, suggesting that the His-rich CTS is evolved to provide a specialized or temporal oligomerization. Further, the observation that the chaperonins with pattern-free CTS are encoded by rapidly growing actinobacteria (Amycolatopsis nivea, M. chubuense, M. smegmatis etc.)2,3,56, suggests a potential correlation between chaperonin overproduction and growth rate, as was observed in E. coli61. We further investigated the functional significance of the gly-met-rich CTS in the essential chaperonins using genetic, structural, and computational tools61.

We found that GroELΔC13 could complement two Ts groEL mutant strains and allowed growth of a strain where the chromosomal groESL operon is switched off but expressed from a relatively leaky promoter (Plac in E. coli LG6). However, GroELΔC13 could not complement the loss of groEL in a strain where either repression of groESL was tight (MGM100) or groEL was knocked out (AI90) (Fig. 2). Despite numerous attempts we were unable to delete the groEL gene in strains expressing GroELΔC13. These observations suggest that at least the last 13 amino acids ((GGM)4M) are necessary for GroEL function. The reason for the discrepancy between these findings and those in some earlier studies on the in vivo activity of C-terminally truncated chaperonins23,24,25 is currently not understood, though it may relate to the different strain’s growth characteristics23, levels of chaperonin expression/activity23, or other experimental conditions used in the previous studies24,25. Given the significant contribution that the CTTs may make to the chaperonin mechanism, as demonstrated both in this paper and in earlier in vitro work17,19,28,29, this is an area that merits further study. As the expression of GroELΔC13 restored growth of LG6 and complemented both groEL Ts mutants, we suggest that mixed GroEL oligomers where a small proportion of the monomers lack the (GGM)4M CTS can function as chaperonins, but those where most or the entire GroEL oligomer is made up of GroELΔC13, do not.

Our structural models showed cavity-specific conformations of CTSs (Fig. 3a) that correlated with the aperture sizes at the base of their respective cavities (Figure S2). Therefore, we speculate that while the smaller aperture of the trans cavity may constrain and compel CTSs to protrude into the cavity, the larger aperture at the cis cavity provides space for them to adopt a more “flattened” conformation. This is consistent with the observations in the molecular dynamic simulations32 and cryo-EM studies28 that CTSs reach the rim of the cavity, where they might interact with the client proteins. The tendency of CTSs to dynamically associate in the trans cavity could be enhanced by (i) strong hydrophobic attraction among the CTSs, (ii) repulsion from the positively charged hydrophilic cavity and (iii) space constraints within the trans cavity (Fig. 3). Further, this association is in agreement with the proposed role of the CTS in the assembly of the GroEL tetradecamer24. The movement of the hydrophobic CTSs towards the opening of the client-capturing trans cavity and segregation in the client-encapsulating cis cavity, (Fig. 3c, S7b and Movie S1), suggests a functional linkage between the two CTS conformations and the synchrony with the en bloc movements of the client-interacting apical domains. The fact that mutating the CTSs in ways that are expected to alter their flexibility and degree of self-association resulted in the loss of chaperonin function (Fig. 4) further supports these proposed roles of the CTSs in in chaperonin function. Notably, these chaperonin constructs exhibited comparable properties (Fig. S6), indicating the observed loss-of function is due to the altered CTSs. The presence of charged residue-rich CTS in some extremophilic chaperonins62 and in organisms with multiple chaperonins3,36, is consistent with the hypothesis that those chaperonin homologues might have functionally diverged to take on the organism-specific roles.

Taken together, employing genetic and structural tools, we have demonstrated that the CTS plays an essential role in the function of GroEL, probably by recognizing the client and/or internalizing it (Movie S1). We therefore propose a model for the CTS’s mechanism of action (Fig. 5). In this model, the CTSs bind the unfolded clients with exposed hydrophobic patches. Upon ATP-induced conformational changes of the GroEL ring, these clients are pulled into the cavity by the flattening CTS. Clients can then fold in the hydrophilic cavity during ATP hydrolysis. Following further conformational changes upon ATP binding to the trans ring, the folded client that now has a polar surface is ejected from the cis ring due to repulsion from the hydrophobic CTSs that push the client outside the cavity. As the CTS is the major divergent sequence feature among the chaperonins in the organisms with multiple chaperonins that exhibit different client pools, it would be interesting to probe if the CTS plays a role in client selection.

As chaperones are involved in several pathogenic processes and implicated in some diseases (the “chaperonopathies”63,64), chaperone mechanisms and client repertoire are being explored in developing novel treatment options. For example, selective inhibition of Hsp90 complex assembly and Hsp90-oncogenic client interactions were effective as anti-tumour agents in vitro and in vivo; several peptidomimetic inhibitors of Hsp90-client interactions are already in various stages of the drug development process65,66. Similarly, chaperonin-based therapies are being explored as the stability67 and folding activity68 of human chaperonins have been implicated in carcinogenesis. As some of the chaperonins with diverged CTSs have been implicated in pathogenesis, understanding their mechanism of action has the potential to identify new treatment options against the diseases, such as by specific inhibition using CTS-specific nanobodies or siRNA.

Materials and Methods

Materials, bacterial strains, and growth conditions

Molecular biology procedures employed in this study were performed according to standard protocols69. All chemicals, enzymes and antibiotics were purchased from Sigma Inc. E. coli was cultured in standard LB broth supplemented as appropriate. The strains and plasmid vectors employed in this study are listed in Table 1. Briefly, in the groEL deletion strain, E. coli AI90, the chromosomal groEL gene is replaced with a kanR cassette and GroEL is supplied under lactose inducible Plac promoter control42 on a p15A, camR shelter plasmid, pTGroEL7. GroEL depletion strains E. coli LG614 and E. coli MGM10043 are derivatives of MG1655 wherein the chromosomal groESL operon is placed downstream of Plac and L-arabinose inducible PBAD promoters, respectively. The GroEL Ts mutant strains, E. coli SV245 and E. coli A757946 are derivative of E. coli K12 strains B178 (galE groESL+) and C600, and bear Ts alleles of groEL, namely, groEL44 and groEL100, that encode GroEL with point mutations at E191G and S201F, respectively. Plasmids pBAD2470 and pTrc99A71 were sourced from lab stocks.

Phylogenetic analysis

A total of 325 actinobacterial chaperonin paralogue sequences were retrieved from InterPro and KEGG databases and the retrieved entries were pruned to remove repetitions. The amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE alignment programme72 by 500 iterations of neighbour joining (NJ) algorithm. The alignment was scored with the gap penalties of 2.9 and hydrophobicity multiplied at 1.2. A highly conserved Proline near the C-terminus was identified (position 525 in E. coli GroEL) and the amino acid sequence after the proline were considered as CTS. A separate CTS alignment was generated as above. Evolutionary divergence between full-length and CTS sequences was modelled as the rate variation among sites using a gamma distribution with a shape parameter of one. Analyses were conducted using the Poisson correction model73. All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair (pairwise deletion option). A total of 639 substitutions in full-length sequences and 57 substitutions in the CTS sequences were observed. The full-length multiple sequence alignment was used in ConSurf to predict the CTS divergence and specific conserved regions among actinobacterial chaperonins. The evolutionary relations among the aligned sequences and a phylogenetic tree were inferred using the NJ algorithm with 500 rounds of boot strapping MEGA1174. The branches belonging to different CTS types were coloured using FigTree v1.4.4. The conservation profiles were mapped onto GroEL structures. The Isoelectric points (pI) and Hydrophobicity (GRAVY) were retrieved from ProtParam tool75 for each CTS sequence and their distribution was compared with the branching in the phylogenetic trees.

Generation of GroEL variants

Oligonucleotide primers employed in this study are listed in Supplementary table 1. The plasmid vectors pBAD/GSL61 and pTrc/GSL61 harbour the E. coli groES-groEL operon cloned into pBAD2470 and pTrc99A71. An opal stop-codon was introduced before 13 residues from the C-terminus in pBAD/GSL and pTrc/GSL using primers GroEL Stop F and GroEL Stop R, resulting in the plasmids pBAD/GroELΔC13 and pTrc/ GroELΔC13, respectively, that encode a GroEL variant lacking (GGM)4M CTS (GroELΔC13). Likewise, constructs expressing GroELΔC16 and GroELΔC28 were generated by introducing opal stop codons into the corresponding codons on pTrc/GSL. GroEL CTS variant clones were generated from pBAD/GSL and pTrc/GSL using synthetic oligonucleotide pairs, AAMF/AAMR, GGDF/GGDR and PPMF/PPMR, as reported to get the pBAD24- and pTrc99a-based GroEL CTS variant clones (Table 1). All the resultant plasmid clones were confirmed by restriction digestion and sequencing.

Complementation studies

The ability of the GroEL carboxyl terminus variants to functionally replace E. coli GroEL was assessed in E. coli groEL conditional mutant strains LG614,42, essentially as reported earlier59 and MGM10043, Ts mutant strains, SV245 and A757946, and deletion stain AI9042, essentially as reported earlier59. Briefly, E. coli LG6, wherein the chromosomal groESL operon is under the control of Plac, was transformed with the pBAD24-derived clones of the groEL CTS variants, and the activity of the cloned genes was scored in the presence of 0.2% L-arabinose, while E. coli MGM100, wherein the chromosomal copy of groE is under the control of PBAD was transformed with the pTrc99A derived clones of groEL CTS variants, and their activity was scored in the presence of 0.2% D-lactose. Plates with either 0.2% D-lactose or 0.2% L-arabinose were included as positive controls, as these are permissive conditions for the strains E. coli LG6 and E. coli MGM100, respectively. For the complementation studies with groEL ts mutant strains, the strains E. coli SV2 and E. coli A7579 were transformed with pBAD24 derived clones of groEL CTS variants (Table 1) and the cultures expressing GroEL variants were spotted onto two LB agar plates supplemented with 0.2% L-arabinose. One of the plates was incubated at 30 °C and the other was incubated at 42 °C, representing permissive and restrictive conditions, respectively. Likewise, E. coli AI90 was transformed with plasmids expressing wildtype groEL pTrc/GSL, groEL CTS variants, pTrc/GroELΔC13, pTrc/GroELΔC16 and pTrc/GroELΔC28, and the vector control, pTrc99A. The resultant transformants were cultured in LB supplemented with Amp, Kan, and 0.2% D-lactose, serially diluted and spotted onto three sets of LB agar plates, the first set supplemented with Amp, Kan, and 0.2% D-lactose and the second set supplemented with Amp, Kan, Cam, and 0.2% D-lactose. The plates were incubated at 30, 37, and 42 °C.

Reverse transcriptase assay PCR to assess expression levels of GroEL

A semi-quantitative expression assay was employed to assess the expression levels of chromosomal and vector-borne groEL genes in E. coli MGM100 and E. coli LG6. For this, E. coli MGM100 and E. coli LG6 were transformed with pTrc/GSL and pBAD/GSL, respectively, and were cultured in LB supplemented with 0.2% D-lactose and 0.2% L-arabinose, respectively, to induce the vector-borne groEL. The cultures were recovered in late-log phase, and the total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent extraction method. 1 μg of total RNA from each culture was reverse transcribed with MMLV reverse transcriptase, using vector-specific primers that bind downstream of the Multiple Cloning Site on the vectors; pTrc R for MGM100 + pTrc/GSL culture and pBAD R for LG6 + pBAD/GSL cultures. These primers, therefore, specifically reverse transcribe the vector-borne mRNA but not the chromosome-borne mRNA. For the amplification of the resulting cDNA, a forward primer GroELRTF was employed, which binds within groEL gene upstream of the C-terminus and with the corresponding reverse primers, either pTrc R or pBAD R, results in a product of about 300 bp, the intensity of which is proportional to the levels of corresponding mRNA. The PCR-amplified products were resolved on 3% agarose gel.

Homology modelling of E. coli GroEL Caboxy terminal sequence region

Since the crystal structures of E. coli GroEL lack the CTSs5,6, we have modelled these regions into E. coli GroEL. Three-dimensional co-ordinates for E. coli GroEL subunits from the cis and the trans cavities, which represent relaxed (R”) and tight (T) conformational states, respectively, were sourced from the crystal structure, PDB ID: 1AON6. CTSs were modelled into these subunit monomers using Modeller 9.1476 and short contaCTS were corrected using the Crystallographic Object-Oriented Toolkit (Coot) 0.877. The models with low Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) were selected, superimposed onto the co-ordinates of E. coli GroEL using the iSuperpose application hosted at Mobyle portal at Ressource Parisienne en BioInformatique Structurale (RPBS), to obtain symmetric and asymmetric tetradecamer models of GroEL with CTS and the resulting models of GroEL tetradecamers were used for further analysis.

Normal mode analysis of the GroEL rings

To understand the transitions of the CTSs between the two conformations, Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) with PATH-ENM was performed on the GroEL protomer and heptamer models, in T and R” states, following the methods reported earlier49,78,79. PATH-ENM built two ENM potentials for each reference structure and combined them into an interpolated mixed potential. At each transition, therefore, the mixed potential had two minima: one for each structure and one saddle point representing the transition state. Ultimately, the transition paths between two end structures were generated using this Mixed Elastic Network Model (MENM). Transitions of the CTSs between the two end states were generated by calculating the contribution of each normal mode to the observed conformational change using Elastic Network Model80,81. The individual normal modes and their deformations were visualized using Pymol 1.3. Additionally, NMA using Molecular Modelling Toolkit (MMTK) package with C-alpha force field was performed on the GroEL protomer and heptamers. In each case, modes with the least deformation energy and eigenvalues were considered for calculating atomic displacements and for further analysis. Molecular fluctuations and correlated movement of the alpha carbons in the molecule were calculated following covariance analysis82,83,84.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All material and other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The plasmids generated in this study will be submitted to Addgene at our lab’s page - https://www.addgene.org/plasmids/articles/28253031/.

References

Horwich, A. L. & Fenton, W. A. Chaperonin-assisted protein folding: a chronologue. Q Rev. Biophys. 53, e4 (2020).

Lund, P. A. Multiple chaperonins in bacteria- why so many? FEMS Microbiol Rev. 33, 785–800 (2009).

Kumar, C. M., Mande, S. C. & Mahajan, G. Multiple chaperonins in bacteria-novel functions and non-canonical behaviors. Cell Stress Chaperones 20, 555–574 (2015).

Hayer-Hartl, M., Bracher, A. & Hartl, F. U. The GroEL-GroES Chaperonin machine: a nano-cage for protein folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 41, 62–76 (2016).

Braig, K. et al. The crystal structure of the bacterial chaperonin GroEL at 2.8 A. Nature 371, 578–586 (1994).

Xu, Z., Horwich, A. L. & Sigler, P. B. The crystal structure of the asymmetric GroEL-GroES-(ADP)7 chaperonin complex. Nature 388, 741–750 (1997).

Tang, Y. C., Chang, H. C., Chakraborty, K., Hartl, F. U. & Hayer-Hartl, M. Essential role of the chaperonin folding compartment in vivo. EMBO J. 27, 1458–1468 (2008).

Weissman, J. S., Rye, H. S., Fenton, W. A., Beechem, J. M. & Horwich, A. L. Characterization of the active intermediate of a GroEL-GroES-mediated protein folding reaction. Cell 84, 481–490 (1996).

Yang, D., Ye, X. & Lorimer, G. H. Symmetric GroEL:GroES2 complexes are the protein-folding functional form of the chaperonin nanomachine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E4298–E4305 (2013).

Horwich, A. L., Farr, G. W. & Fenton, W. A. GroEL-GroES-mediated protein folding. Chem. Rev. 106, 1917–1930 (2006).

Lorimer, G. H. A quantitative assessment of the role of the chaperonin proteins in protein folding in vivo. FASEB J. 10, 5–9 (1996).

Tang, Y. C. et al. Structural features of the GroEL-GroES nano-cage required for rapid folding of encapsulated protein. Cell 125, 903–914 (2006).

Farr, G. W., Fenton, W. A. & Horwich, A. L. Perturbed ATPase activity and not “close confinement” of substrate in the cis cavity affects rates of folding by tail-multiplied GroEL. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5342–5347 (2007).

Horwich, A. L., Low, K. B., Fenton, W. A., Hirshfield, I. N. & Furtak, K. Folding in vivo of bacterial cytoplasmic proteins: role of GroEL. Cell 74, 909–917 (1993).

Chen, S. et al. Location of a folding protein and shape changes in GroEL-GroES complexes imaged by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature 371, 261–264 (1994).

Thiyagarajan, P., Henderson, S. J. & Joachimiak, A. Solution structures of GroEL and its complex with rhodanese from small-angle neutron scattering. Structure 4, 79–88 (1996).

Clare, D. K. et al. ATP-triggered conformational changes delineate substrate-binding and -folding mechanics of the GroEL chaperonin. Cell 149, 113–123 (2012).

Chen, D. H. et al. Visualizing GroEL/ES in the act of encapsulating a folding protein. Cell 153, 1354–1365 (2013).

Ishino, S. et al. Effects of C-terminal truncation of Chaperonin GroEL on the yield of in-cage folding of the green fluorescent protein. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15042–15051 (2015).

Nakamura, T., Tanaka, M., Maruyama, A., Higashi, Y. & Kurusu, Y. A nonconserved carboxy-terminal segment of GroEL contributes to reaction temperature. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 68, 2498–2504 (2004).

Gao, L., Imanaka, T. & Fujiwara, S. A mutant chaperonin that is functional at lower temperatures enables hyperthermophilic archaea to grow under cold-stress conditions. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2642–2652 (2015).

Luo, H. & Robb, F. T. A modulator domain controlling thermal stability in the Group II chaperonins of Archaea. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 512, 111–118 (2011).

McLennan, N. F., Girshovich, A. S., Lissin, N. M., Charters, Y. & Masters, M. The strongly conserved carboxyl-terminus glycine-methionine motif of the Escherichia coli GroEL chaperonin is dispensable. Mol. Microbiol 7, 49–58 (1993).

Burnett, B. P., Horwich, A. L. & Low, K. B. A carboxy-terminal deletion impairs the assembly of GroEL and confers a pleiotropic phenotype in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 176, 6980–6985 (1994).

McLennan, N. F., McAteer, S. & Masters, M. The tail of a chaperonin: the C-terminal region of Escherichia coli GroEL protein. Mol. Microbiol 14, 309–321 (1994).

Machida, K., Kono-Okada, A., Hongo, K., Mizobata, T. & Kawata, Y. Hydrophilic residues 526 KNDAAD 531 in the flexible C-terminal region of the chaperonin GroEL are critical for substrate protein folding within the central cavity. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6886–6896 (2008).

Piana, S. & Shaw, D. E. Atomic-level description of protein folding inside the GroEL Cavity. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 11440–11449 (2018).

Weaver, J. et al. GroEL actively stimulates folding of the endogenous substrate protein PepQ. Nat. Commun. 8, 15934 (2017).

Weaver, J. & Rye, H. S. The C-terminal tails of the bacterial chaperonin GroEL stimulate protein folding by directly altering the conformation of a substrate protein. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23219–23232 (2014).

Teshima, T., Mashimo, S., Kondo, A. & Fukuda, H. Affinity purification and immobilization of fusion chaperonin GroEL-(His)6 and its utilization to mediate protein refolding. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 86, 357–362 (1998).

Kohda, J., Kondo, A., Teshima, T. & Fukuda, H. in Progress in Biotechnology Vol. 16 (eds I. Endo, T. Nagamune, S. Katoh, & T. Yonemoto) 119–124 (Elsevier, 2000).

Dalton, K. M., Frydman, J. & Pande, V. S. The dynamic conformational cycle of the group I chaperonin C-termini revealed via molecular dynamics simulation. PLoS One 10, e0117724 (2015).

Hirtreiter, A. M. et al. Differential substrate specificity of group I and group II chaperonins in the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 1152–1168 (2009).

Klunker, D. et al. Coexistence of group I and group II chaperonins in the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33256–33267 (2003).

Lapidus, A. et al. Complete genome sequence of Brachybacterium faecium type strain (Schefferle 6-10). Stand. Genom. Sci. 1, 3–11 (2009).

Kong, T. H., Coates, A. R., Butcher, P. D., Hickman, C. J. & Shinnick, T. M. Mycobacterium tuberculosis expresses two chaperonin-60 homologs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 2608–2612 (1993).

Kumar, C. M. S. & Mande, S. C. Prokaryotic Chaperonins: Multiple Copies and Multitude Functions (Springer Nature, 2017).

Kumar, C. M. S. in Prokaryotic Chaperonins: Multiple Copies and Multitude Functions (eds C. M. Santosh Kumar & Shekhar C. Mande) 39–51 (Springer Singapore, 2017).

Goyal, K., Qamra, R. & Mande, S. C. Multiple gene duplication and rapid evolution in the groEL gene: functional implications. J. Mol. Evol. 63, 781–787 (2006).

Hughes, A. L. Contrasting evolutionary rates in the duplicate chaperonin genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. leprae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 1343–1359 (1993).

Mayrose, I., Graur, D., Ben-Tal, N. & Pupko, T. Comparison of site-specific rate-inference methods for protein sequences: empirical Bayesian methods are superior. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1781–1791 (2004).

Ivic, A., Olden, D., Wallington, E. J. & Lund, P. A. Deletion of Escherichia coli groEL is complemented by a Rhizobium leguminosarum groEL homologue at 37 degrees C but not at 43 degrees C. Gene 194, 1–8 (1997).

McLennan, N. & Masters, M. GroE is vital for cell-wall synthesis. Nature 392, 139 (1998).

Chapman, E. et al. Global aggregation of newly translated proteins in an Escherichia coli strain deficient of the chaperonin GroEL. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15800–15805 (2006).

Tilly, K., VanBogelen, R. A., Georgopoulos, C. & Neidhardt, F. C. Identification of the heat-inducible protein C15.4 as the groES gene product in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 154, 1505–1507 (1983).

Wróbel, B., Yosef, Y., Oppenheim, A. B. & Oppenheim, A. Production and purification of SV40 major capsid protein (VP1) in Escherichia coli strains deficient for the GroELS chaperone machine. J. Biotechnol. 84, 285–289 (2000).

Clare, D. K., Bakkes, P. J., van Heerikhuizen, H., van der Vies, S. M. & Saibil, H. R. Chaperonin complex with a newly folded protein encapsulated in the folding chamber. Nature 457, 107–110 (2009).

Hyeon, C., Lorimer, G. H. & Thirumalai, D. Dynamics of allosteric transitions in GroEL. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18939–18944 (2006).

Zheng, W., Brooks, B. R. & Hummer, G. Protein conformational transitions explored by mixed elastic network models. Proteins 69, 43–57 (2007).

Gomez-Tamayo, J. C. et al. Analysis of the interactions of sulfur-containing amino acids in membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 25, 1517–1524 (2016).

Pal, D. & Chakrabarti, P. Non-hydrogen bond interactions involving the methionine sulfur atom. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 19, 115–128 (2001).

Viitanen, P. V. et al. Mammalian mitochondrial chaperonin 60 functions as a single toroidal ring. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 695–698 (1992).

Chatellier, J., Hill, F., Foster, N. W., Goloubinoff, P. & Fersht, A. R. From minichaperone to GroEL 3: properties of an active single-ring mutant of GroEL. J. Mol. Biol. 304, 897–910 (2000).

Sun, Z., Scott, D. J. & Lund, P. A. Isolation and characterisation of mutants of GroEL that are fully functional as single rings. J. Mol. Biol. 332, 715–728 (2003).

Colaco, C. A. & MacDougall, A. Mycobacterial chaperonins: the tail wags the dog. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 350, 20–24 (2014).

Mande, S. C. & Kumar, S. C. M. in Prokaryotic Chaperonins: Multiple Copies and Multitude Functions (eds C. M. Santosh Kumar & Shekhar C. Mande) 67–80 (Springer Singapore, 2017).

Fan, M. et al. The unusual mycobacterial chaperonins: evidence for in vivo oligomerization and specialization of function. Mol. Microbiol 85, 934–944 (2012).

Qamra, R., Srinivas, V. & Mande, S. C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis GroEL homologues unusually exist as lower oligomers and retain the ability to suppress aggregation of substrate proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 605–617 (2004).

Kumar, C. M. et al. Facilitated oligomerization of mycobacterial GroEL: evidence for phosphorylation-mediated oligomerization. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6525–6538 (2009).

Ansari, M. Y. et al. A novel function of Mycobacterium tuberculosis chaperonin paralog GroEL1 in copper homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 594, 3305–3323 (2020).

Kumar, C. M. S. et al. Chaperonin Abundance Enhances Bacterial Fitness. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 669996 (2021).

Gao, L. & Fujiwara, S. in Prokaryotic Chaperonins: Multiple Copies and Multitude Functions (eds C. M. Santosh Kumar & Shekhar C. Mande) 113–128 (Springer Singapore, 2017).

Rappa, F. et al. HSP-molecular chaperones in cancer biogenesis and tumor therapy: an overview. Anticancer Res. 32, 5139–5150 (2012).

Conway de Macario, E., Yohda, M., Macario, A. J. L. & Robb, F. T. Bridging human chaperonopathies and microbial chaperonins. Commun. Biol. 2, 103 (2019).

Paladino, A. et al. Chemical perturbation of oncogenic protein folding: from the prediction of locally unstable structures to the design of disruptors of Hsp90-client interactions. Chemistry 26, 9459–9465 (2020).

Serwetnyk, M. A. & Blagg, B. S. J. The disruption of protein-protein interactions with co-chaperones and client substrates as a strategy towards Hsp90 inhibition. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 1446–1468 (2021).

Braxton, J. R., Shao, H., Tse, E., Gestwicki, J. E. & Southworth, D. R. Asymmetric apical domain states of mitochondrial Hsp60 coordinate substrate engagement and chaperonin assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 31, 1848–1858 (2024).

Caruso Bavisotto, C. et al. Curcumin Affects HSP60 Folding Activity and Levels in Neuroblastoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21020661 (2020).

Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E. F. & Sambrook, J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory., 1982).

Guzman, L. M., Belin, D., Carson, M. J. & Beckwith, J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4121–4130 (1995).

Amann, E., Ochs, B. & Abel, K. J. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene 69, 301–315 (1988).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinforma. 5, 113 (2004).

Zuckerkandl, E. & Pauling, L. in Evolving Genes and Proteins (eds Vernon Bryson & Henry J. Vogel) 97-166 (Academic Press, 1965).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Gasteiger, E. et al. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003).

Webb, B. & Sali, A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 54, 5 6 1–5 6 37 (2016).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Zheng, W. A unification of the elastic network model and the Gaussian network model for optimal description of protein conformational motions and fluctuations. Biophys. J. 94, 3853–3857 (2008).

Chilukoti, N., Kumar, C. M. & Mande, S. C. GroEL2 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals the importance of structural pliability in chaperonin function. J. Bacteriol. 198, 486–497 (2016).

Zheng, W., Brooks, B. R. & Thirumalai, D. Allosteric transitions in the chaperonin GroEL are captured by a dominant normal mode that is most robust to sequence variations. Biophys. J. 93, 2289–2299 (2007).

Yang, Z., Majek, P. & Bahar, I. Allosteric transitions of supramolecular systems explored by network models: application to chaperonin GroEL. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000360 (2009).

Ichiye, T. & Karplus, M. Collective motions in proteins: a covariance analysis of atomic fluctuations in molecular dynamics and normal mode simulations. Proteins 11, 205–217 (1991).

Hollup, S. M., Salensminde, G. & Reuter, N. WEBnm@: a web application for normal mode analyses of proteins. BMC Bioinforma. 6, 52 (2005).

Tiwari, S. P. et al. WEBnm@ v2.0: Web server and services for comparing protein flexibility. BMC Bioinforma. 15, 427 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Arthur Horwich, Millicent Masters, Alan Fersht, Costa Georgopoulos, and Ariella Oppenheim for the GroE mutant strains, E. coli LG6, MGM100, SV2 (groEL44), and A7579 (groEL100), respectively. We thank Chris Bunse, Damon Huber, Jayaraman Gowrishankar, Jayant Udgaonkar, Sandhya Visweswaraiah, and Abhijit A. Sardesai for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK (BB/S017526/1), CMSK’s Royal Society Newton International Fellowship (NF161469), and the Department of Biotechnology, India (BT/PR3260/BRB/10/967/2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M.S.K., S.C.M., and P.A.L. conceptualized the idea. C.M.S.K. conducted the experiments and A.M.M. assisted in Phylogenetic analysis. C.M.S.K., S.C.M. and P.A.L. supervised the investigation, discussed the findings, and written the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Frank Robb and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Antonio Calabrese and Laura Rodríguez Pérez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, C.M.S., Mai, A.M., Mande, S.C. et al. Genetic and structural insights into the functional importance of the conserved gly-met-rich C-terminal tails in bacterial chaperonins. Commun Biol 8, 555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07927-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07927-x

This article is cited by

-

GroEL/ES chaperonin unfolds then encapsulates a nascent protein on the ribosome

Nature Communications (2025)