Abstract

Plants deploy a sophisticated defense mechanism against pathogens through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and resistance (R) proteins, activating pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI). E3 ubiquitin ligases, notably U-box types like PUB22 and PUB23, modulate PTI by suppressing immune responses. The role of MusaPUB22/23 in immunity against Xanthomonas vasicola pv. musacearum (Xvm), the cause of banana Xanthomonas wilt (BXW) in East Africa, was investigated by knocking out these genes in the BXW-susceptible ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ cultivar. The gene targets used in this study, MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23, were identified through prior comparative transcriptomics analysis, which revealed their upregulation in susceptible versus resistant genotypes during early infection with Xvm. Gene edited plants exhibited mutations in both genes, with no significant growth penalties in most events. Several edited lines displayed complete resistance to Xvm infection, while others showed partial resistance, in contrast to the full susceptibility of wild-type controls. Resistance correlated with hydrogen peroxide accumulation and activation of key defense-related genes, indicating enhanced immune responses. This study identifies MusaPUB22/23 as susceptibility genes and provides strong evidence for their role in modulating immunity in banana. The results highlight the potential of gene editing as a promising strategy against BXW, addressing a crucial agricultural issue in East Africa while unraveling plant immunity regulation and paving the way for disease-resistant crop engineering targeting PUB genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants possess a sophisticated defense mechanism against invading pathogens, exhibiting a multi-layered immunity system based on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and resistance (R) proteins. The first line of defense, pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), initiates upon PRR recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). However, pathogens can evade PTI by secreting virulence effectors, leading to the activation of effector-triggered immunity (ETI) mediated by R proteins. PTI mediated by PRRs is effective against a broad range of pathogens, whereas ETI mediated by R proteins is typically effective against specific pathogens or strains. Both PTI and ETI involve complex signaling events, including ion influx, reactive oxygen species (ROS) bursts, activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), transcriptional reprogramming, phytohormone production, and callose deposition in the cell wall1.

In plant immune signaling, ubiquitination and protein phosphorylation regulate defense responses, with E3 ubiquitin ligases playing a crucial role2. E3 ubiquitin ligases, in particular, have emerged as key players in various facets of plant immunity, from pathogen perception to signal transduction and immune response3. Among these, U-box-type E3 ubiquitin ligases like PUB22, PUB23, and PUB24, localized in the cytoplasm, serve as a critical negative regulator of PTI. In Arabidopsis thaliana, PUB22 effectively attenuates PTI responses in coordination with PUB23 and PUB244. The significance of these E3 ligases is underscored by the enhanced resistance demonstrated by the pub22/pub23/pub24 triple mutants in Arabidopsis against pathogens like Fusarium oxysporum5. These ligases target proteins like Exo70B2, modulating immune responses by regulating ROS production and MAPK activation6. The degradation of Exo70B2 via ubiquitination redirects positive signaling toward vacuolar degradation pathways, effectively downregulating the immune response6. It has been shown that exo70B2 mutants showed increased susceptibility to pathogens6.

The significance of these findings extends beyond basic research, especially in addressing critical agricultural challenges. In East and Central Africa, the cultivation of banana faces a severe threat from banana Xanthomonas wilt (BXW), caused by Xanthomonas vasicola pv. musacearum [(Xvm), formally known as Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum (Xcm)]7, causing substantial economic losses8. BXW management is profoundly challenging, and effective management requires adherence to a set of cultural practices that farmers often neglect due to the associated high labor and doubts about the efficacy of these practices. To date, resistance to BXW is only found in wild-type banana progenitors such as Musa balbisiana (BB genome) and Musa acuminata subsp. Zebrina (AA genome)9, with all the cultivated varieties remaining highly susceptible. Traditional breeding for BXW resistance is hindered by cultivar sterility, low genetic diversity, and long generation times, making gene editing an attractive alternative. In this study, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to generate pub22/23 double mutants in a banana cultivar susceptible to BXW disease. These edited events exhibited enhanced resistance to BXW without affecting their growth, underscoring the potential of MusaPUB22/23 knockout in engineering disease-resistant crops. Molecular analysis of these edited events provided deeper insights into the role of MusaPUB22/23 in banana immunity. The successful editing of MusaPUB22/23 not only showcases the potential of targeting PUB genes for enhancing disease resistance in banana but also suggests a broader application of this approach across various crops. By precisely modifying key immune regulators such as PUB22/23, we offer a viable solution for advancing food security and addressing agricultural challenges in pathogen-prone regions.

Results

Gene target identification

The selection of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes for this study was based on the comparative transcriptomic analysis between the BXW-susceptible cultivar ‘Pisang Awak’ and the resistant wild-type progenitor ‘Musa balbisiana’ during the early stages of Xvm infection. This analysis revealed upregulation of MusaPUB22/23 genes in the susceptible cultivar compared to the resistant one10. Building upon this finding, this study aimed to disrupt the function of MusaPUB22/23 in the BXW-susceptible cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’(AAB genome), a dessert type of banana commonly grown in East Africa.

The relative expression patterns of MusaPUB22 (Ma07_g03320) and MusaPUB23 (Ma07_g03310) genes in the BXW-susceptible banana cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ and the resistant wild-type progenitor ‘Musa balbisiana’ during early Xvm infection provide insights into the functional role of MusaPUB genes in plant disease resistance. In ‘Sukali Ndiizi’, MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 were both upregulated (~ 10-fold and ~ 2-fold, respectively) in inoculated plants compared to uninoculated control plants at 12 h post inoculation (hpi) (Fig. 1a, b). In contrast, the expression of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in the BXW-resistant M. balbisiana plants remained unchanged between the inoculated and non-inoculated plants (Fig. 1a, b). These results signify the activation of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in the BXW-susceptible cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ in response to Xvm infection, suggesting their potentially critical role in disease development.

a, b Relative expression levels of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in BXW-susceptible and BXW-resistant banana genotypes. Mb, Musa balbisiana (BXW-resistant genotype). SN, Sukali Ndiizi (BXW-susceptible genotype). C, control; Xvm, Xanthomonas vasicola pv. musacearum. Control and Xvm represent uninoculated and inoculated, respectively. Data were presented as box-and-whisker plots (n = 3). c Primary protein structure of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23.

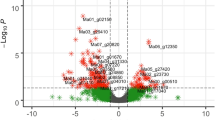

Phylogenetic analysis of PUB

The phylogenetic relationships of Musa E3 ubiquitin ligase with its homolog in other plant species, Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, M. acuminata, M. balbisiana, and Solanum lycopersicum revealed the presence of 144 E3 ubiquitin ligase genes in M. acuminata, 116 in Musa balbisiana, 65 in A. thaliana, 83 in O. sativa and 64 in S. lycopersicum (Fig. 2). Upon constructing the Clustal Omega phylogenetic tree, all members of E3 ubiquitin ligase were classified into seven categories, namely group I to group VII. The largest group was group V, predominantly comprising of genes of M. acuminata and M. balbisiana genes. The smallest group was group I, encompassing only twelve genes, with three representatives each from M. acuminata, M. balbisiana, A. thaliana, and S. lycopersicum. Focusing on the MusaPUB22/23 genes targeted for mutation in this study, Ma07_p03320 (MusaPUB22), Mba07_p03250 (MusaPUB22), Ma07_p03310 (MusaPUB23), and Mba07_p03220 (MusaPUB23), were classified in group VII along with AtPUB22 and AtPUB23.

Multiple protein sequence alignments of the U-box domain sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, M. acuminata, M. balbisiana, and Solanum lycopersicum were performed using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment program, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the ggtree package in R.

The primary protein structure of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in Musa spp. contains a U-box of 69 amino acids (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S1), characteristic of E3 ubiquitin ligase.

gRNA design and CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid construction

The alignment of the coding DNA sequences (CDS) for MusaPUB22 (Ma07_g03320 and Mba07_g03250) and MusaPUB23 (Ma07_g03310 and Mba07_g03220), obtained from the banana genome hub, reveals 97.5% nucleotide similarity. Both MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 exhibit a single exon, but the MusaPUB22 CDS spans 240 bp (Fig. 3a), while the MusaPUB23 CDS is 1239 bp long (Fig. 3b). Two gRNAs with canonical cut sites 84 bp apart, targeting the U-box region of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes, were designed. The gRNAs with the highest efficiency and minimal potential for off-target mutations were selected. Sequencing analysis of the target fragment from ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ confirmed the PUB22/23 sequences were identical with the reference genomes, and no SNPs were detected in the gRNAs (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b). Subsequently, the gRNAs, together with the high GC content plant codon-optimized Cas9 gene, driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, were integrated into the T-DNA region of the binary vector pMDC32 to yield the CRISPR/Cas9 construct pMDC32-Cas9-MusaPUB, where each gRNA is independently regulated by the OsU6 promoter (Fig. 3c).

Illustration of MusaPUB22 (a) and MusaPUB23 (b) gene structure. The positions of gRNA binding sites in target regions in MusaPUB22/23 genes are shown with black arrows (▼) indicating canonical cut sites for both guides. Orange boxes denote coding DNA sequences (CDS), while Blue arrows indicate the U-box. Red letters correspond to the gRNA binding sites in the targeted regions, while black letters (G/C) denote the single-nucleotide polymorphism at position 751 (position 1 at 5’ of gRNA1) in MusaPUB23. Purple letters indicate the protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) sequence. The primers used for amplifying and sequencing the MusaPUB gene are shown with their positions relative to the start codon position indicated in brackets. The region of coding sequence of the U-box is compressed in length in the diagram and is not to scale. c T-DNA region of binary plasmid construct pMDC32-Cas9-MusaPUB used for editing of banana. LB, Left border; RB, Right border, hpt, hygromycin phosphotransferase gene; 35S P, CaMV35S promoter, OsU6 p, Oryza sativa U6 promoter; 2 × 35S P, double CaMV35S promoter. d Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of T-DNA of the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and regeneration of edited events (1) Agro-infected embryogenic cell suspension on embryo development medium; (2) Embryos on embryo maturation medium; (3-4) Germination of embryos in selective medium containing hygromycin; (5) Well-rooted plantlets in proliferation medium; (6) Potted plants of gene-edited events in the greenhouse. The scale bar represents 1 cm for panels 1–5 and 10 cm for panel 5.

Generation of transgenic events

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was used to introduce the T-DNA into the embryogenic cell suspension of ‘Sukali Ndiizi’, and 53 putative transgenic events were regenerated (Fig. 3d). The PCR analysis of the regenerated events showed an amplified fragment of 587 bp, indicating the presence of the Cas9 gene in the events (Supplementary Fig. S3). These events were micropropagated in the proliferation medium to produce enough replicates for disease evaluation. Upon obtaining well-rooted plantlets, they were transplanted to soil in the pots and acclimatized in the greenhouse for subsequent phenotyping.

Detection of edits in transgenic plants

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of MusaPUB22/23 was confirmed through analysis of edits in 12 independent events, along with the wild-type control plants. This involved amplifying the target sites, cloning the PCR product into a vector, and performing Sanger sequencing of 10 clones per sample. All events contained at least one mutated allele for each gene (Fig. 4). Predominantly, the mutations were deletions ranging from −1 to −255 bp or insertions (+1 or +49 bp) or substitutions. The frequency of each mutation type is detailed in Fig. 4.

a Mutations in targeting the MusaPUB22 gene. b Mutations in targeting the MusaPUB23 gene. Red nucleotides indicate the gRNAs, and purple nucleotides indicate the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). Black dashes (—) represent deletions, green nucleotides denote substitutions, and blue nucleotides indicate insertions. C, wild-type non-edited control sequences; P2-P50, independently edited events. The number of indels as deletions (‒), insertions (+), and substitutions (S) are indicated on the right panel. * indicates a big insertion in PUB22-25, and the sequence of the insert is written in blue. The first nucleotide in gRNA1 of MusaPUB22/23 is underlined to indicate the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); ‘A’ in MusaPUB22 and ‘G’ in MusaPUB23.

For the MusaPUB22 gene target, all the events tested exhibited mutations at both target sites, confirming the effectiveness of both gRNAs (Fig. 4a). Event P26 showed mutations alongside a wild-type (WT) sequence, detected in 1 out of 10 sequenced clones, suggesting that not all alleles may have been mutated. In contrast, event P25 showed uniform mutations across all ten clones, with + 49/− 1 mutations (Fig. 4a). Events P2, P20, and P50 exhibited big deletions, with the largest deletions being − 48, − 80, and − 83 bp, respectively (Fig. 4a). Events P6 and P39 showed chimeric mutations. Except for event P26, no WT sequence was detected, indicating that all three MusaPUB22 alleles were likely edited (Fig. 4a). However, further deep sequencing would be necessary to confirm this conclusion. The close proximity of the forward sequencing primer, PUB_Seq_F, to gRNA1 in the sequencing of the MusaPUB22 gene may have limited the detection of some of the edits closer to the primer, particularly deletions in the 5’ direction.

For the MusaPUB23 gene target, events P25, P33, P39 and P50 displayed mutations only at the target site 2, while event P45 showed mutations exclusively at the target site 1 (Fig. 4b). Events P6, P33, P39 and P50 showed a WT sequence alongside mutations, suggesting that not all alleles may have been mutated. Except for these four events (P6, P33, P39, and P50), the WT sequence was not detected, indicating that all three MusaPUB23 alleles may have been edited. Events P2 and P45 showed uniform mutations across all 10 clones, with very big deletions, − 75 and − 50, respectively (Fig. 4b). Event P1 displayed a very big deletion of − 255 bp (Fig. 4b). Event P26 featured a 1 bp substitution in addition to the deletions. Events P6 and P35 showed chimeric mutations (Fig. 4b).

Assessment of plant growth in pub22/23 edited events

Twelve edited events, along with wild-type controls, were assessed for their growth parameters, including plant height, pseudostem girth, number of functional leaves, and total leaf area at 90 days after planting to determine any potential adverse effect of MusaPUB22/23 allele knockout. Most of the edited events displayed a normal appearance, exhibiting no discernible morphological or phenotypical disparities compared to the control plants (Fig. 5a–d). Notably, only two events produced off-type plants (P20 and P50), characterized by relatively shorter height and smaller total leaf area. This observation suggests that the knockout of MusaPUB22/23 alleles primarily led to a consistent and normal growth pattern in most edited events, with only marginal deviations detected in a few events.

Assessment of disease resistance in pub22/23 edited events

To assess the response of pub22/23 double mutants to the bacterial pathogen Xvm, twelve edited events, along with wild-type control plants, underwent evaluation for disease resistance under greenhouse conditions. Upon artificially challenging with Xvm infection, the wild-type controls exhibited pronounced disease symptoms like drooping, wilting, and necrosis within 22.6 ± 6.5 days post inoculation (dpi) with a 100% disease incidence (Table 1). Subsequently, these symptoms progressed to encompass the entire plant, culminating in complete wilting within 38 ± 4.3 dpi (Fig. 6 and Table 1), confirming their susceptibility to Xvm infection. In contrast, four edited events (P2, P5, P35, and P50) exhibited complete resistance against Xvm, displaying no disease symptoms development upon Xvm challenge (Fig. 6 and Table 1). These events showed no growth deformity. In addition, event P39 demonstrated a substantial 93.3% disease resistance, with the manifestation of disease symptoms confined solely to the inoculated leaf with a very low disease severity index of 6.6%. The remaining seven events (P1, P6, P20, P25, P33, and P45) showed partial resistance against Xvm, while one edited event (P26) exhibited susceptibility similar to the control non-edited event. The sequencing result of event P26 indicated that not all alleles of MusaPUB22 were knocked out. This comprehensive evaluation unveils a spectrum of disease resistance levels among the edited events, signifying the efficacy of the pub22/23 mutations in conferring protection against Xvm infection.

Reactive oxidative burst study

To gain insights into the basic mechanism underlying pathogen infection in the pub22/23 events, a reactive oxidative burst assay was conducted. The accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was assessed as the signal molecule released during Xvm-infection and an indicator of programmed cell death (PCD) phenotype. The five events (P2, P5, P35, P39, and P50) exhibiting enhanced BXW-resistance were stained with the 3′diaminobenzidine (DAB) combined with image analysis of digital leaf photographs by the Image J program. Upon Xvm infection, the cut leaves of edited plants displayed more browning compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 7). These findings suggest that during the Xvm infection, pub22/23 edited events exhibited PCD associated with H2O2 accumulation.

a Reactive oxidative burst assay of pub22/23 edited events and non-edited control upon infection with Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum (Xvm) followed by diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. Photomicrographs showing the difference in browning intensity between the leaves of edited events compared to non-edited control plants. All images were captured at 300 dpi with a resolution of 2600 × 1595 pixels. Scale bar corresponds to 100 pixels, equivalent to 2.6 cm at the displayed resolution. b Graphical representation of browning intensity of edited and non-edited control leaves after Xvm infection, followed by DAB staining. Data were presented as box-and-whisker plots (n = 3).

Assessment of defense-related gene activation in pub22/23 edited events upon Xvm infection

The activation of key defense signaling genes, including Pathogenesis related protein (PR1), antimicrobial peptide (AMP, Vicilin), Respiratory burst oxidase homolog A and C (Rboh-A and Rboh-C), Oxidative Signal-Inducible1 (Oxi1), MYB family transcription factor 4 (MYB4), Leucine-rich repeat (LRR), Polyamine oxidase-like and Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase 6-like (PPKL) was evaluated in the selected edited events (P2, P5 and P50) at 12 hpi (Fig. 8). The relative expression of Rboh-A, Rboh-C, Oxi1, and Polyamine oxidase-like genes, pivotal players in plant pathogen response involving oxidative burst, were higher in the edited events compared to both Xvm-inoculated and uninoculated wild-type controls. PR1 gene, known for its toxicity to invading bacterial pathogens, exhibited a remarkable activation, up to 30-70-fold in the edited events. In addition, other defense genes, PPKL involved in plant defense signaling, MYB transcription factors crucial for various biological processes, including responses to plant pathogen attacks, LRR serving as intracellular receptors for pathogen recognition, and Vicilin as AMPs, were also observed to be activated in edited events compared to wild-type controls upon Xvm infection. These findings collectively indicate that the mutation of MusaPUB22/23 activated the defense signaling genes, resulting in robust and stable resistance against Xvm.

a Respiratory burst oxidase homolog A (Rboh-A). b Respiratory burst oxidase homolog C (Rboh-C). c Oxidative Signal-Inducible1 (Oxi1). d Pathogenesis-related R protein (PR1). e Leucine-rich repeat (LRR). f Antimicrobial peptide (AMP, Vicilin). g MYB family transcription factor 4 (MYB4). h Polyamine oxidase-like. i Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase 6-like (PPKL). Data were presented as box- and -whisker plots (n = 6).

Discussion

This study delves into the intricate defense mechanisms employed by plants, mainly focusing on the role of PUB22 and PUB23 in regulating PTI against pathogens. The study explores the involvement of these genes in banana immunity against Xvm, the causative agent of BXW. By utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 tool, MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 were disrupted in the BXW-susceptible banana cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’, resulting in resistance to Xvm without compromising growth, a promising avenue for addressing critical agricultural challenges posed by BXW.

The research findings align with previous studies elucidating the sophisticated defense mechanisms plants employ against pathogen invasion. Comparative transcriptomic analysis and functional validation highlighted the role of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in the context of BXW resistance10. The study revealed the upregulation of these genes in the susceptible cultivar compared to the BXW-resistant wild-type progenitor, suggesting their involvement in disease susceptibility, corroborating findings from other plant species like Arabidopsis4. This reinforces the rationale behind the selection of MusaPUB22/23 for the current study.

The phylogenetic analysis of Musa E3 ubiquitin ligase genes revealed distinct categorization into seven groups, similar to previous reports from maize11 and banana12, with MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 classified within group VII, alongside their homologs from Arabidopsis thaliana. This classification, coupled with the presence of a U-box domain of 69 amino acids, points to their role as E3 ubiquitin ligases involved in ubiquitin proteasome-mediated degradation. This study showed the presence of 144 E3 ubiquitin ligase genes in M. acuminata and 116 in M. balbisiana; however, a previous report in banana (M. acuminata) reported only 94 genes12.

The edited pub22/23 banana events demonstrated enhanced resistance against Xvm infection, similar to the enhanced disease resistance observed in the triple pub22/23/24 mutants of Arabidopsis4. The pub22/23 banana edited events showed normal growth parameters, indicating the potential of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 in immune responses to bacterial pathogens without compromising plant growth. All BXW-resistant edited events (P2, P5, P35, P39, P50; Table 1) showed mutations in all alleles of MusaPUB22. Notably, events P2 and P5, which exhibited knockout of all three alleles in both MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes with no WT sequence and no chimerism, were fully resistant to Xvm infection and displayed no growth defects. However, sequencing of additional clones or deep sequencing could provide further insight into mutations present in these edited events. Future studies will focus on assessing the stability of these edited events, including the presence of mutations and the long-term durability of the disease resistance trait.

The results of this study shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying disease resistance in the edited banana plants, particularly in response to Xvm. Upon recognition of PAMPs by PRRs, a cascade of reactions is triggered, leading to PTI as the first line of plant immunity. Further analysis revealed a notable enhancement in oxidative burst or accumulation of H2O2 in pub22/23 edited events compared to wild-type controls upon pathogen infection, indicating an activation of PTI. This observation mirrors findings from pub22/23/24 Arabidopsis mutants, suggesting that the disruption of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes enhanced one of the earliest immune responses, including the generation of ROS as part of the oxidative burst and hypersensitive response (HR), leading to programmed cell death13. Gene expression patterns demonstrated the upregulation of key PTI marker genes in BXW-resistant edited events in response to pathogen challenge.

Overall, these results demonstrate the role of E3 ubiquitin ligases MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 as negative regulators of plant immunity. The activation of PTI pathways in pub22/23 edited events contributes to resistance to BXW disease. The findings advance our understanding of plant immunity and offer practical avenues for addressing agricultural challenges such as BXW in banana cultivation. By leveraging CRISPR/Cas9 technology to enhance disease resistance, this study represents a step towards sustainable and resilient agriculture, paving the way for future research in crop improvement and agricultural sustainability. However, field trials will be essential to validate these findings since the observed results were in greenhouse conditions. In addition, because PTI is involved in broad-spectrum disease resistance, the edited banana plants may also show resistance to other diseases, such as the devastating Fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense Tropical Race 4 (Foc TR4) and black Sigatoka caused by Mycosphaerella fijiensis. Testing these edited events against such diseases could further demonstrate their potential for broader agricultural impact.

Methods

Plant material

The ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ banana cultivar, also known as the apple banana, is widely cultivated in East and Central Africa but is highly susceptible to BXW disease. Originally classified within the Kamaramasenge subgroup, a 2003 study using flow cytometry and chromosome counts revealed that ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ is a triploid cultivar belonging to the AAB genome group14. For this study, ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ was selected due to its agricultural significance.

As embryogenic cell suspensions (ECS) are preferred explants to generate gene-edited plants, ECS of ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ were generated using immature male flowers15. The ECS were maintained by regular subculture every 10-14 days in the liquid callus induction medium (CIM) at 28 ± 2 °C on a rotary shaker at 95 rpm in the dark chamber.

Relative expression of MusaPUB transcript in susceptible and resistant banana

The second fully open leaf of one-month-old in vitro plantlets of the BXW-susceptible banana cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ and the BXW-resistant wild-type progenitor Musa balbisiana were inoculated with Xvm. The inoculated leaf sample was collected 12 h post-inoculation (hpi). Total RNA was extracted from the leaves using a Qiagen Plant RNeasy Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions to determine transcript accumulation of MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using LunaScript® RT SuperMix cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England BioLabs inc, Cat. E3010L) according to the instructions in the user manual. The cDNA was diluted 10 times, and 5 µl was used for qRT-PCR with primers PUB22_qPCR_F and PUB22_qPCR_R and PUB23_qPCR_F and PUB23_qPCR_R (Supplementary Table S1) using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; www.lifetechnologies.com). The qRT-PCR analysis was performed in a QuantStudio5 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Musa primers, Musa 25S_F and Musa 25S_R (Supplementary Table S1) were used as the internal control. The 2-ΔCt method was used to calculate the relative gene expression levels16.

Target gene identification and phylogeny

Protein sequences containing the U-box domain, belonging to the Interpro protein family IPR003613, were downloaded for five plant species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Solanum lycopersicum, Musa acuminate, and Musa balbisiana from GreenphlyDB (https://www.greenphyl.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi). The individual proteins from the pangenome clusters were retrieved using the mapping files provided under the download section within GreenphylDB. The PUB protein identifier for the proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana was obtained from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). The file providing the protein IDs and the PUB protein numbers from Arabidopsis are provided in the supplementary information (Supplementary Table S2). The protein sequences were aligned using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment program, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the ggtree package in R. The categories in the phylogenetic tree are based on the categories for the Arabidopsis genes11.

gRNA designing and plasmid construction

Banana homologs of the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MusaPUB22 gene (Ma07_g03320 and Mba07_g3250) sequences and MusaPUB23 gene (Ma07_g03310 and Mba07_g3220) were downloaded from banana genome A (Musa acuminata ‘DH-Pahang’ V2) and genome B (Musa balbisiana ‘DH-PKW’ V1.1) through the banana genome hub (http://banana-genome-hub.southgreen.fr), respectively. To identify the conserved region, the four gene sequences were aligned using Multalin (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/). Two gRNAs were initially designed with an 84 bp spacing between the canonical cut sites using the Alt-R Custom Cas9 crRNA design tool (https://eu.idtdna.com/site/order/designtool/index/CRISPR_CUSTOM). To assess their specificity, the gRNAs were checked for any potential off-target sites using the Breaking Cas tool (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/breakingcas/). The targets for editing in ‘Sukali Ndiizi’were sequenced to eliminate the potential impact of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on gRNA activity. The gRNAs were ordered for synthesis only after confirming the sequence in the ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ cultivar.

To confirm the conservation of the gRNAs in the cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’, which may have a different sequence from the reference genome (Musa acuminata ‘DH-Pahang’ V2 and Musa balbisiana ‘DH-PKW’ V1.1) used for initial gRNA design, the target region was sequenced. Primers flanking the two gRNAs, primers PUB_Seq_F and PUB_Seq_R (Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Fig. S2a), designed from a highly conserved region in the U-box, were used to amplify the target region in ‘Sukali Ndiizi’.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of the banana cultivar ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method17. The PCR was carried out in a final reaction volume of 20 μl, comprising 2 μl 10X PCR buffer, 0.4 μl dNTP mix (10 mM), 0.5 μl of 10 mM of each primer, 0.1 μl Hotstar Taq DNA polymerase (www.qiagen.com), 1 μl DNA (200 ng/μl), and 15.5 μl nuclease-free water. The PCR program was 95 °C for 5 min, then 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel and stained with GelRed. The PCR products were then directly purified (amplicon pool) and sequenced. The sequences were aligned using SnapGene software (WWW.snapgene.com). No SNPs were found in the gRNA target regions, confirming the accuracy of the gRNAs. gRNA1: AGTCAGGATACTGCACTCGG and gRNA2: ACTGTGCCTGGTGCTCCAAG, with their corresponding reverse sequences, were synthesized as oligos after adding the appropriate adaptors to the 5’ end (Supplementary Table S1), and cloning was performed18.

Five plasmids were used to produce the multiplexed CRISPR construct: pYPQ131, pYPQ132, pYPQ142, pYPQ167, and pMDC32. Plasmids pYPQ131 (Addgene, Plasmid #99886) and pYPQ132 (Addgene, #99889) are Golden Gate entry vectors for cloning gRNA oligos. Each plasmid contains the gRNA scaffold, the OsU6 promoter, and the tetracycline-resistant gene. Plasmid pYPQ142 (Addgene, Plasmid #69294) is a Golden Gate vector for multiplexing two gRNAs and contains a spectinomycin-resistant gene. The plasmid pYPQ167 (Addgene, Plasmid #69309) is a Gateway entry vector carrying a plant codon-optimized Cas9 gene without promoter and terminator and a spectinomycin resistance gene as a selection marker.

The synthesized oligos were annealed and inserted into the BsmBI sites of pYPQ131 and pYPQ132, resulting in pYPQ131_gRNA1 and pYPQ132_gRNA2. The cloning reaction was transformed into E. coli strain DH5α and confirmed by sequencing. To assemble both gRNAs together, the cassette containing the gRNAs, the OsU6 promoter, and terminator from pYPQ131_gRNA1 and pYPQ132_gRNA2 were cloned by Golden Gate reaction using the BsaI and T4 DNA ligase enzymes into the entry vector pYPQ142 to yield pYPQ142_gRNA1_gRNA2. The resulting reaction was confirmed by digestion with NcoI and EcoRI. The correct clone containing the gRNA sequences with OsU6 promoters, alongside the Cas9 entry vector pYPQ167, was cloned into the Gateway destination binary vector pMDC32 (Addgene, Plasmid #32078) in a multi-site cloning reaction by LR clonaseTM (Invitrogen, New Zealand) recombination reaction, resulting in the construct pMDC32_Cas9_MusaPUB. After confirmation by restriction digestion with KpnI, the correct clone was transformed into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 by electroporation and selected on LB medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/l) and rifampicin (25 mg/l). The transformed Agrobacterium was checked by colony PCR for the presence of the plasmid construct and used for editing experiments. The plasmid pMDC32_Cas9_MusaPUB contains the hpt gene as an in planta selection marker, the Cas9 gene, and two gRNAs, each driven by the rice OsU6 promoter.

Generation of the gene-edited events

The gene-edited events were generated by delivering the T-DNA of the plasmid pMDC32_Cas9_MusaPUB into the ECS of ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ using the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation system15 with minor changes. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 harboring the construct pMDC32_Cas9_MusaPUB with a hygromycin selection marker gene was used for transformation. The Agro-infected cells were regenerated on a selective medium containing hygromycin (25 mg/l). The regenerated, edited events were maintained and multiplied by sub-culturing every 6–8 weeks on proliferation medium for further analysis.

PCR analysis to confirm the presence of the Cas9 gene

Genomic DNA was extracted from 100 mg of fresh leaf samples collected from putative edited and wild-type plantlets using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method17. The presence of the transgene in all hygromycin-resistant events was assessed through PCR analysis, utilizing the primers 35S_F and Cas9_R (refer to Supplementary Table S1). The PCR was performed in a 20 µl reaction volume comprising of 1 µl genomic DNA (100 ng/µl), 2 µl of 10X PCR buffer, 0.4 µl of dNTP mix (10 mM), 0.5 µl of 10 mM of each primer, 0.1 µl HotStar Taq polymerase (www.qiagen.com), and 15.5 µl nuclease-free water. PCR amplification conditions were initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. After amplification, 10 µl of the PCR product was resolved on 1% agarose gel stained with GelRed.

Detection of edits in transgenic plants

Genomic DNA from the Cas9 positive events and wild-type plants were used for PCR amplification of the target regions in the MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes. A single plantlet of each event was used for cloning. To differentiate MusaPUB22 and MusaPUB23 genes, the primer pair PUB23_Seq_F and PUB_Seq_R was used to amplify the MusaPUB23 gene, while primers PUB_Seq_F and PUB22_Seq_R were used to target the MusaPUB22 gene. Due to the higher level of conservation within the region targeted by the primers PUB_Seq_F and PUB22_Seq_R, four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at positions 751 (position 1 at 5’ of gRNA1), 774, 804 and 920 were also considered to differentiate SNPUB22 and SNPUB23 within the target region in ‘Sukali Ndiizi’ (Supplementary Fig. S2a and S2b).

The PCR was performed following the conditions described under the gRNA design and plasmid construction section. After amplification, 10 µl of the PCR product was resolved on a 1% agarose gel stained with GelRed. Before sequencing, the PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification Kit (Qiagen). The purified products were cloned into pCR™8/GW/TOPO® (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, transformed to DH5α chemical competent E. coli cells and selected on LB plates containing spectinomycin. Ten clones from each transgenic event were Sanger sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 sequencing system from Thermo Fisher. The sequencing reaction was set up as follows: a reaction mixture containing 2.5 µl of plasmid DNA clone, 1.5 µl of 5X sequencing buffer, 0.5 µl of Big Dye Terminator, 1 µl of 10 mM of specific primers (PUB_Seq_F and PUB22_Seq_R, PUB23_Seq_F and PUB_Seq_R, Supplementary Table S1), and 4.5 µl of nuclease-free water. The reaction was amplified in a thermal cycler using the following conditions: initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 10 s, annealing at 50 °C for 10 s, extension at 60 °C for 4 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 4 min. Following amplification, the sequencing product was purified, resuspended in 10 µl HiDi® formamide, and sequenced using an ABI 3130 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, California, USA). The sequence analysis, including alignments and chromatogram visualization, was performed in Geneious version 7.1.9 (Auckland, New zealand) software using the default parameters in the assemble to reference feature.

Growth analysis of pub22/23 edited events

Twelve gene-edited events were randomly selected to assess their plant growth. Three replicates of well-rooted plantlets for each independent edited event, along with the wild-type control, were transferred to sterile soil in small plastic disposable cups (size 150 ml) and acclimatized for 4 weeks in a humidity chamber. Following acclimatization, the plants were transitioned to bigger pots (10 liters in size) and grown in the greenhouse under controlled conditions for a duration of 90 days, maintaining a temperature range of 25–30 °C19.

At the end of the 90-day growth period, various parameters were recorded, including plant height, pseudostem girth, total number of functional fully opened green leaves, and length and width of the fully developed second leaf from the top. The total leaf area (TLA) was calculated19,20.

In which L = Length of the middle leaf, W = width of the middle leaf, and N = total number of leaves in the plant.

Disease evaluation of pub22/23 edited events under greenhouse conditions

To assess the resistance to BXW disease, three-month-old plants of 12 edited events and wild-type control plants were evaluated under greenhouse conditions. Three replicates of each edited event and control non-edited plants were injected with 100 µl of the bacterial culture of Xvm (Ugandan strain) in the midribs of the second fully opened leaf, starting from the top. The onset of disease symptoms, including leaf drooping, wilting, necrosis, and complete wilting of plantlets, was diligently recorded over 60 days post-inoculation (dpi). Disease severity was quantified on a scale of 0–5, where 0 denoted no symptoms, and subsequent ratings reflected increasing levels of severity: 1 indicated only the inoculated leaf wilting, 2 denoted 2 to 3 leaves wilting, 3 represented 4 to 5 leaves wilting, 4 signified all leaves wilting but the plant remaining alive, and 5 indicated the entire plant succumbing to the disease. The relative resistance of edited events to BXW disease was calculated19.

DSI (%) = [Σ (Disease severity scale) X no. of plants in each scale)/(total number of plants) X (maximal disease severity scale) X100

Resistance (%) = (Reduction in wilting in event /Proportion of leaves wilted in control) X 100

Reactive oxidative burst analysis in pub22/23 edited events

To investigate hydrogen peroxide production in edited plants following Xvm infiltration, a histochemical staining assay using DAB (3,3’-diaminobenzidine) solution was performed21,22. Fully opened green leaves of six-weeks-old in vitro plantlets of the edited events and wild-type control plants were infiltrated with 100 µl of fresh Xvm culture. The infiltrated leaves were incubated for 12 h post-infection (hpi), after which they were cut and incubated in DAB solution in 15 ml falcon tubes wrapped with aluminum foil for 12 h on a shaker (70 rpm) at room temperature. After incubation, the DAB solution was removed, and samples were washed with a bleaching solution (ethanol: acetic acid: glycerol in the ratio of 3:1:1) for 30 min in a water bath at 95 °C to remove chlorophyll. The bleaching solution was refreshed, and the samples were further incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the samples were removed from the bleaching solution, stored in 70% ethanol, and photographed using an SMZ1500 stereomicroscope (Carlsbad, CA, USA) equipped with a high-zoom Nikon camera. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA) was employed to analyze the pixel intensity of browning in the photographs.

Relative expression of defense genes in pub22/23 edited events

One-month-old selected edited events (P2, P5, and P50) and wild-type control plants were inoculated with a fresh culture of Xvm. Leaf tissues were collected at 12 hpi. Total RNA was extracted from leaf tissues of three edited events (P2, P5, and P50) and wild-type plantlets using the Qiagen Plant RNeasy Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using LunaScript® RT SuperMix cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England BioLabs inc, Cat. E3010L) according to the instructions in the user manual. The cDNA was diluted 10 times, and 5 µl was used for qRT-PCR with primers listed in Supplementary Table S1 using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; www.lifetechnologies.com). qRT-PCR was performed in a QuantStudio5 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with primers for Pathogenesis related R protein (PR1), antimicrobial peptide (AMP) (vicilin), Respiratory burst oxidase homolog A and C (Rboh-A and Rboh-C), Oxidative Signal-Inducible1 (Oxi1), MYB family transcription factor 4 (MYB4), Leucine-rich repeat (LRR), Polyamine oxidase-like and Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase 6-like (PPKL) (Supplementary Table S1). For each sample, three technical replicates were used. Musa primers, Musa 25S_F and Musa 25S_R (Supplementary Table S1), were used as the internal control, and normalization was performed using the untreated control. The relative expression levels of the defense genes were calculated using the 2-ΔCt method16.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were conducted with three independent biological replicates, defined as independent experiments performed on different days using distinct biological samples (e.g., different plants or independently regenerated events). Disease evaluation data were collected and analyzed using Minitab Statistical Software, version 16 (Pennsylvania, USA). Differences in disease resistance between various edited events and wild-type control were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and means separated by Fisher’s Test. Statistical significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05.

Plant growth measurements, qRT-PCR, and reactive oxidative burst assay results for edited events compared to control non-edited plants were visualized as boxplots using Minitab. For other experiments where statistical analysis was not applicable (e.g., molecular confirmation by PCR or sequencing), reproducibility was ensured by performing at least three independent experimental repeats with consistent results. Sample sizes (n) for each experiment are indicated in the respective figure legends or methods section. No data were excluded from the analyses. Experimental conditions were standardized across replicates to ensure consistency and reproducibility.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that underpin the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its supplementary materials. The sequencing data of edited events are submitted to Zenodo and are publicly accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15119408. Numerical source data underlying all graphs presented in the main figures are provided as supplementary data in excel file.

References

Peng, Y., van Wersch, R. & Zhang, Y. Convergent and divergent signaling in PAMP-triggered immunity and effector-triggered immunity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 31, 403–409 (2018).

Kong, L., Rodrigues, B., Kim, J. H., He, P. & Shan, L. More than an on-and-off switch: Post-translational modifications of plant pattern recognition receptor complexes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 63, 102051 (2021).

Zhou, B. & Zeng, L. Conventional and unconventional ubiquitination in plant immunity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 18, 1313–1330 (2017).

Trujillo, M., Ichimura, K., Casais, C. & Shirasu, K. Negative regulation of PAMP-triggered immunity by an E3 ubiquitin ligase triplet in arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 18, 1396–1401 (2008).

Chen, Y. et al. Root defense analysis against Fusarium oxysporum reveals new regulators to confer resistance. Sci. Rep. 4, 5584 (2014).

Stegmann, M. et al. The ubiquitin ligase PUB22 targets a subunit of the exocyst complex required for PAMP-triggered responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 4703–4716 (2012).

Tripathi, L. et al. Xanthomonas Wilt: A threat to banana production in East and Central Africa. Plant Dis. 93, 440–451 (2009).

Abele, S. & Pillay, M. Bacterial Wilt and drought stresses in banana production and their impact on economic welfare in Uganda. J. Crop Improv. 19, 173–191 (2007).

Nakato, G. V. et al. Sources of resistance in Musa to Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum, the causal agent of banana Xanthomonas wilt. Plant Pathol. 68, 49–59 (2019).

Tripathi, L., Tripathi, J. N., Shah, T., Muiruri, S. K. & Katari, M. Molecular basis of disease resistance in banana progenitor Musa balbisiana against Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum. Sci. Rep. 9, 7007 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Classification and expression profile of the U-Box E3 ubiquitin ligase enzyme gene family in maize (Zea mays L.). Plants 11, 2459 (2022).

Hu, H., Dong, C., Sun, D., Hu, Y. & Xie, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of U-Box E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase gene family in banana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3874 (2018).

Felix, G., Duran, J. D., Volko, S. & Boller, T. Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 18, 265–276 (1999).

Pillay, M., Hartman, J., Dimkpa, C. & Makumbi, D. Establishing the genome of ‘Sukali Ndizi’. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 11, 119–124 (2003).

Tripathi, J. N., Oduor, R. O. & Tripathi, L. A high-throughput regeneration and transformation platform for production of genetically modified banana. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1025 (2015).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-DDCt method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Stewart, C. N. Jr. & Via, L. E. A rapid CTAB DNA isolation technique useful for RAPD fingerprinting and other PCR applications. Bio Tech. 14, 748–751 (1993).

Ntui, V. O., Tripathi, J. N. & Tripathi, L. Robust CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing tool for banana and plantain (Musa spp.). Cur. Plant Biol. 21, 100128 (2020).

Tripathi, J. N., Lorenzen, J., Bahar, O., Ronald, P. & Tripathi, L. Transgenic expression of the rice Xa21 pattern recognition receptor in banana (Musa sp.) confers resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum. Plant Biotech. J. 12, 663–673 (2014).

Kumar, N., Krishnamoorthy, V., Nalina, L. & Soorianathasundharam, K. A new factor for estimating total leaf area in banana. Infomusa 11, 42–43 (2002).

Daudi, A. & O’Brien, J. A. Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide by DAB staining in Arabidopsis leaves. Bio Protoc. 2, e263 (2012).

Carril, P., Bernardes, D. S. A., Tenreiro Rogério, T. & Cristina, C. An optimized in situ quantification method of leaf H2O2 unveils Interaction dynamics of pathogenic and beneficial bacteria in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the CGIAR research program for roots, tubers, and bananas and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The authors would like to thank Sarah Macharia and Mark Adero for their assistance with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.T. conceived the idea, planned experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript; V.O.N. designed the guides, prepared the construct, and performed molecular analysis of the edited events; S.M. performed the sequencing of the edited events; T.S. worked on phylogenetic analysis; J.N.T. generated the edited events, evaluated edited events for plant growth and disease resistance, performed the statistical analysis, and prepared figures; all authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Leena Tripathi is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Biology, but was not involved in the editorial review of, nor the decision to publish this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jingyang Li, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: David Favero.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tripathi, L., Ntui, V.O., Muiruri, S. et al. Loss of function of MusaPUB genes in banana can provide enhanced resistance to bacterial wilt disease. Commun Biol 8, 708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08093-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08093-w