Abstract

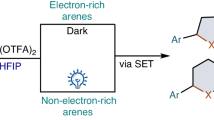

The isoperfluoropropyl group (i-C3F7) is an emerging motif in pharmaceuticals, agrichemicals and functional materials. However, isoperfluoropropylated compounds remain largely underexplored, presumably due to the lack of efficient access to these compounds. Herein, we disclose the practical and efficient isoperfluoropropylation of aromatic C-H bonds through the invention of a hypervalent-iodine-based reagent-PFPI reagent, that proceeds via a Ag-X coupling process. The activation of the PFPI reagent without any catalysts or additives was demonstrated in the synthesis of isoperfluoropropylated electron-rich heterocycles, while its activity under photoredox catalysis was shown in the synthesis of isoperfluoropropylated non-activated arenes. Detailed mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations revealed a SET-induced concerted mechanistic pathway in the photoredox reactions. In addition, the unique conformation of i-C3F7 in products, that involved intramolecular hydrogen bond was investigated by X-ray single-crystal diffraction and variable-temperature NMR experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

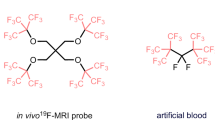

As a result of the unique metabolic stability, cell permeability, and lipophicity observed for fluoroalkyl compounds1,2,3,4,5,6,7, the efficient introduction of polyfluoroalkyl motifs in commonly used building blocks has attracted intense attention8,9,10,11. As the earliest widely studied fluoroalkyl group, trifluoromethyl group (CF3) is now widely accepted as one of the privileged functional groups for modern medicinal chemists. Numerous efforts from research groups around the world have been devoted to this field, and a plethora of sophisticated trifluoromethylating methods have been reported in the past two decades12,13,14. Depending on the desired transformation, different reagents for nucleophilic, radical, or electrophilic trifluoromethylation are used (Fig. 1a). As a large analog of the CF3, the isoperfluoropropyl group (i-C3F7), featuring a stronger electron-withdrawing effect and more steric hindrance, is normally considered as a “super” CF3 group and plays a unique role in bioactive compounds, functional materials, and organocatalysts (Fig. 1b)15,16,17,18,19,20,21. For instance, pyrifluquinazon and nicofluprole are commercially available insecticides with excellent activity against broad-spectrum pests. Meanwhile, i-C3F7 can be applied to the development of inverse agonists with better selectivity for identification of biologic-like in vivo efficacy17, and it is reasonable to think that i-C3F7 would have potential application for the design and preparation of candidate pharmaceuticals. Nevertheless, unlike introducting CF3 into organic molecules, which has diversified over the years, the primary methods of incorporating i-C3F7 have been limited to a few isoperfluoropropylating reagents, such as isoperfluoropropyl iodide (i-C3F7I) and isoperfluoropropyl metal (i-C3F7M) reagents.

Generally, i-C3F7I is the most convenient and commercially available i-C3F7 source22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Unlike their analogous alkyl halide, the formation of a Nu-i-C3F7 bond via direct SN2 type displacement is unfavorable due to strong electron repulsion and steric hindrance between fluoroalkyl and incoming nucleophiles, the formation of an energetically adverse i-C3F7 carbocation transition state structure (Fig. 2a). i-C3F7I is easier to be initiated than the linear isomers by heating or a large number of reducing agents, generating i-C3F7 radical for further conversions24,25,26,27,28. Recently, a series of metal-catalyzed isoperfluoropropylation using i-C3F7I as i-C3F7 source have also been reported (Fig. 2b)22,23. Nevertheless, most of these methods suffered from some limitations such as the need for harsh reaction conditions, and the use of metal catalysts and iodine active species to interfere with the isoperfluoropropylation process. Several attempts for synthesizing nucleophilic i-C3F7M reagents were reported (Fig. 2b). For instance, Burton and co-works realized the synthesis of Cu-i-C3F7 from i-C3F7I with the assistance of cadmium29. In 1968, Burnard et al. found that hexafluoropropylene (HFP) reacted with silver fluoride to form an isoperfluoropropyl carbanion (Ag-i-C3F7)30. Although these organometallic reagents were unstable and sensitive to moisture, a series of metal-catalyzed nucleophilic isoperfluoropropylation were developed31,32,33. Very recently, Qing’s and Wu’s group reported an efficient oxidative isoperfluoropropylation of unactivated alkenes, arenes, and arylboronic acid with HFP-derived Ag-i-C3F7, and stoichiometric oxidants and metal were necessary for this strategy34,35,36,37.

Evidently, an active electrophilic reagent that behaves as a convenient source of the i-C3F7 and is amenable to direct isoperfluoropropylation of a broad range of substrates under mild conditions, while avoiding the use of prefunctionalized substrate or strong oxidants, remains synthetically desirable and challenging, and essential to facilitate the development of new classes of fluoroalkyl compounds with unexplored properties. Due to the strong electron-withdrawing effect of i-C3F7, the synthesis of stable electrophilic reagents is extremely difficult in theory. Hypervalent iodine benziodoxolone has emerged as a powerful tool for oxidative functional group installation38,39,40, and is generally considered environmentally benign and widely available alternatives to traditional transition-metal-based reagents. In view of our group’s interest in hypervalent iodine and fluorine chemistry41,42,43,44,45

, we envisaged that the merger of the i-C3F7 with a hypervalent iodine scaffold would provide a platform for the development of such a PFPI reagent (Fig. 2c).

Results and discussion

Synthesis of i-C3F7-iodine(III) reagent

The i-C3F7-iodine(III) reagent (PFPI) was synthesized in 71% yield by means of a two-step procedure (Fig. 2c). First, 2-iodobenzoic acid was treated with trichloroisocyanuric acid (TCICA) to give a hypervalent chloroiodine(III) intermediate. Inspired by the synthesis of Togni-reagent46,47, all our initial attempts to obtain the desired i-C3F7-iodane(III) by means of ligand-exchange reactions of the hypervalent iodine(III) intermediate with common TMS-i-C3F7 under various conditions failed (Fig. 3c). However, the treatment of the chloroiodine(III) intermediate with Ag-i-C3F7 based on our proposed Ag-X coupling strategy generated desired PFPI compound in good yield (Fig. 3a), which was characterized by 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectroscopy. The product can be purified by washing with diethyl ether to deliver an easy to handle, free-flowing off-white powder that can be stored under anhydrous conditions in the absence of light without significant decomposition for at least a month. In addition, other types of iodine(III) intermediate are also tested, and the i-C3F7-iodine(III) reagent can be obtained in 65% yield by ligand-exchange of the acetoxyiodine(III) intermediate (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, when we changed the substrate to chloroiodane(III) with amide skeleton in this reaction system, the quantitative decomposition of i-C3F7− iodine(III) was occurred with a Gibbs free energy equal to −1.4 kcal mol−1 (DFT calculated value, See Supplementary Data 3) and monofluoroiodane(III) was obtained as the main product (Fig. 3d), which revealed that the stability of the reagent is significantly related to the skeleton structure of iodine(III).

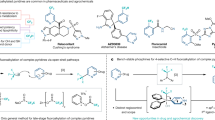

Metal-free electrophilic isoperfluoropropylation of electron-rich heterocycles with PFPI

It was found that the PFPI regent had unique reactivity compared with other fluoroalkyl-iodine(III) such as Togni-reagent in our early activity exploration. We proposed that the high reactivity of PFPI reagent comes from the strong electron-withdrawing effect of i-C3F7, which makes it easy to be reduced to radical anion through a single electron transfer process. At the same time, the large steric hindrance causes significant elongation of the C(i-C3F7)-I bond (2.282 Å, DFT calculated value), resulting in homolysis and release of highly active i-C3F7 radical. Motivated by these preliminary indications, we developed the isoperfluoropropylation of electron-rich heterocycle compounds and commenced with indoles, which were used as valuable building blocks in the synthesis of natural products and bioactive compounds48. We chose the commercially available N-methyl indole as a model substrate, and after screening reaction conditions (see SI, Table S1 and S2) we were pleased to observe that the reaction with 2 proceeded readily at room temperature in the absence of any catalyst or exogenous base, delivering the desired product 4 in excellent yield. As comparision, the use of Togni-reagents for similar reactions usually required Lewis acids such as Zn(NTf )2 for activation49,50. Subsequently, the scope of this direct C-H isoperfluoropropylation was explored (Fig. 4). Most of the electron-rich heterocycles could be transformed to the isoperfluoropropylated compounds 3 in good to excellent yields. In general, the isoperfluoropropylation took place selectively at the C-3 position of indoles and N-alkyl (-Me, -Et, -Bn, -i-Bu) indoles (4-11, 19-23) showed better reaction efficiency than those N-H indoles (12-18). With regard to the functional group tolerance, a diverse array of functional groups such as aldehyde (11), ether (12), ester (8, 14, 20), cyano (10, 18, 21), nitro (9, 22), and aryl halides (6, 7, 15-17, 19) were compatible with the reaction conditions. For 3-CHO indole, a mixture of 2-and 5-substituted products was obtained. In addition, pyrrole (26, 27), carbazole (28), thiophene (29, 30), thianthrene (31), and furan (32, 33) could all be smoothly isoperfluoropropylated with i-C3F7-iodine(III) reagent. A plethora of indoles derived from natural products, such as tryptophan (35), melatonin (36), and xanthotoxin (37), as well as the drug molecules zolmitriptan (34), successfully underwent the direct isoperfluoropropylation, which proved that complex architectures were well tolerated.

Screening of reaction conditions for photocatalytic isoperfluoropropylation

Encouraged by the successful metal-free isoperfluoropropylation of electron-rich heterocycles, we next attempted to examine the C-H isoperfluoropropylation of various common arenes. Due to the relatively weak activity of non-activated arenes, their reaction with electrophilic reagents required relatively harsh reaction conditions. In 2019, Bao’ group developed an efficient Mo-catalyzed highly site-selective perfluoroalkylation of anilide derivatives by use of fluoroalkyl iodide, but these reactions need to be carried out at a high temperature and in the atmosphere of CO26. In our method, single electron transfer (SET) from an photoredox catalyst to the i-C3F7-iodine(III) is followed by C − I cleavage to deliver i-C3F7 radical that displayed unique reactivity profiles. To find the most suitable catalytic conditions for the isoperfluoropropylation of anilides, a plethora of metal and organic photoredox catalyst, such as fac-Ir(ppy)3, [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6, PTH and Eosin Y, were tested (Fig. 5). Having found the most suitable conditions for the generation of the i-C3F7 radical precursor from i-C3F7-iodine(III) 1 using [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 with appropriate redox potential (IrIV/IrIII* = −0.96 V vs SCE) as a photoredox catalyst (1 mol%), we optimized the C-H isoperfluoropropylation of i-C3F7 radical with benzanilide (2b) with respect to different reaction parameters (See SI, Table S3–S5). A condition-based sensitivity-screening approach revealed that the process is rather insensitive towards variations in concentration, temperature, oxygen and scale-up (See SI, Table S6–S10). Simple nitrogen sparging afforded comparable yields with a more rigorous 4 Å MS procedure (low water), whereas running the reaction in the presence of stoichiometric water completely suppressed the productive process (high water).

Experimental and computational mechanistic studies

Firstly, UV-visible analysis showed that only the iridium catalyst substantially absorbed at blue light (λ ≈ 450 nm) (Fig. 6a). We also conducted Stern-Volmer luminescence quenching experiments and found that the excited-state Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2* complex was efficiently quenched by PFPI 1 (Figs. 6b, 6c). A radical trap experiment by using 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethylpiperidinyl-1-oxide (TEMPO) as a probe and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies of the reaction of 2b and 1 with spin-trapping agent phenyl tert-butyl nitrone (PBN) demonstrated that an isoperfluoropropyl radical was involved in the reaction (Figs. 6d, 6e). Isotopic (H/D) competition experiments show that the C-H bond cleavage process was not a rate-determining step (Fig. 6f). Finally, subjecting a mixture of arenes, 43-1 and 43-2 bearing an electron-withdrawing group (−CN) to standard conditions produced 44-1 as the major product (88%) along with minor product 44-2 (35%), supporting an electrophilic process to the arene in the product-determining step (Fig. 6g).

For a better understanding of how the photocatalyst efficiently mediated the catalytic anilide isoperfluoropropylation, the energy profiles of the reaction were evaluated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and the results were summarized in Fig. 7. Consistent with Stern-Volmer fluorescence quenching experiments, our DFT calculations show that after blue light excitation of the [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]+ cation (IrL+), SET process from IrL+ in its lowest triplet excited state (3IrL*+) to 1 is −23.4 kcal mol−1 exergonic to form the oxidized radical cation IrL·++ along with the reduced radical anion A, thus favoring the oxidative quenching of 3IrL*+. Further SET oxidation of TMEDA with the oxidized radical cation IrL·++ regenerates the photo-catalyst cation IrL+ in the ground state along. Subsequently, the cleavage of the C-I bond proceeds almost without barrier and 2-iodobenzoate anion releases from the photo-generated A is −9.9 kcal mol−1 exergonic to form the i-C3F7 radical B. Once formed, the reactive radical B can be easily added to the para-site C-H bond of 1b to form a new C-C bond, which is 4.1 kcal mol−1 endergonic over a low barrier of 17.0 kcal mol−1 (via TS) to form the transient radical C. The final stage of the reaction involves the SET oxidation of intermediate C and deprotonation of aryl cation D to generate target product 39, with a Gibbs free energy of the two processes equal to −30.7 kcal mol−1 and −52.1 kcal mol−1 respectively.

DFT-computed Gibbs free energy profile (in kcal mol−1, at 298 K) in MeCN solution for photocatalyzed isoperfluoropropylation of benzanilide (2b) with PFPI reagent 2 at the TPSS-D3/def2-SVP + IEFPCM//TD-B3LYP/def2-TZVP + SMD level of theory. See Supplementary Data 3.

Substrate scope with respect to photocatalytic isoperfluoropropylation of non-activated arenes

With the viable reaction conditions in hand, the substrate scope of this visible-light-induced isoperfluoropropylation was examined (Fig. 8). Gratifyingly, the reaction of 1 with a variety of anilides afforded the corresponding isoperfluoropropylated products (38, 45-48) in moderate to excellent yields with highly para-site selectivity. Primary aniline derivates bearing different functional groups, such as choro (49), nitro (50), alkyl (50), PhO-(51), and N-substituted anilines were also applicable to the reaction (52-57). Polysubstituted aryl ethers and coumarins derivates as substrates worked smoothly to furnish corresponding products 58-60 and 61-65, respectively with good yields and functional group compatibility. Coumarins were clinically used as oral anticoagulants and the introduction of isoperfluoropropyl would significantly improve the liposolubility of molecules and thus promote drug metabolism. Noteworthy, indazole (66, 67) and benzo-[2,1,3]-thiadiazole (68) functionalities could be compatible under the photoredox condition, which couldn’t be isoperfluoropropylation under the previous catalyst free conditions.

The synthetic applications and X-ray single-crystal diffraction analysis of products

Our method could offer straightforward access to the 4-perfluoroisopropyl-2,6-dichloroaniline fragment on gram-scale, a key intermediate structure in total synthesis sequences towards broad-spectrum insecticide nicofluprole (Fig. 9a)51. The results confirm that the present protocol can serve as an efficient and practical strategy to obtain products. In 2021, Gilmour analyzed the conformation of a heptafluoroisopropylated arene and revealed the preference of the benzylic C(sp3)-F bond to be co-planar with the aryl ring52. Herein, the X-ray single-crystal diffraction analysis (See SI, Table S11-S20; Supplementary Data 1 and Data 2) of compounds 5 and 8 confirmed the connectivity of the molecules (Fig. 9b), and variable-temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectrum of compound 5 clearly depicts that i-C3F7-substituted indoles possess interesting conformation, which might find useful applications in medicinal chemistry (Fig. 9c). The space orientation of the central-site fluorine atom (F1) of the isoperfluoropropyl is affected by the hydrogen atom on the adjacent group. In the solution state at room temperature, the F1 of 5 showed two orientations and can freely convert between each other, which is reflected in the 1H NMR spectrum that the hydrogen atom of 4-site C(sp2)-H and 2-site -CH3 presented irregular wide peak signals, and the peak pattern becomes sharper after increasing the temperature (Fig. 9d). The result can also be confirmed by two sets of F1 signals in the VT 19F NMR (See SI, Fig. S11). The striking molecular conformation is probably due to the formation of a six membered ring based on an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the F1 on isoperfluoropropyl and the hydrogen on the adjacent group or carbon atom.

Conclusions

In summary, we have described the development of a hypervalent iodine-based PFPI reagent, which is easily accessible from commercial starting materials in two steps. The reagent can be engaged in metal-free electrophilic and photoredox radical isoperfluoropropylation. The mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations suggested a SET-induced concerted mechanistic pathway in photoredox reactions. Further studies of this air-stable and highly reactive solid reagent are underway in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of PFPI reagent

In a nitrogen-filled glove box, an oven-dried crimp cap vessel with Teflon-coated stirrer bar was charged with silver fluoride (0.64 g, 5.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and was brought under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen. To this vessel, anhydrous acetonitrile (20 mL) and hexafluoropropylene (1 atm, balloon and adequate) were added, and the mixture was stirred at ice-water bath in the dark until silver fluoride precipitate dissolved completely. Then this solution was added to another oven-dried vessel, which filling with 1-chloro-1,2-benziodoxol-3-(1H)-one (1.44 g, 5.1 mmol, 1.02 equiv.) and 4 Å molecular sieves (100 mg). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature in the dark for 1 h. The reaction mixture was filtered over a sintered-glass funnel with a tightly packed pad of Celite (0.5 cm thick) under dry nitrogen atmosphere, and the filter cake was rinsed with additional anhydrous acetonitrile (5–10 mL). The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and crude solid product washed with anhydrous Et2O (10–20 mL). Then, the product was obtained by anhydrous DCM leaching in ultrasonic generator under dry nitrogen atmosphere and vacuum evaporated of solvent. The solid was dried for 1 h under high vacuum to give 1-isoperfluoropropyl-1,2-benziodoxol-3-(1H)-one as off white solid (1.48 g, 71% yield).

General procedure for the metal-free isoperfluoropropylation of electron-rich heterocycles

In a 25 mL screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stirring bar, electron-rich heterocycles (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), PFPI reagent (166.4 mg, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and additives were dissolved in MeCN (2 mL). The reaction was stirred for 2 h at room temperature under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen. The reaction was quenched with 10 mL 5% NaHCO3 aqueous solution, then extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under a vacuum. The residue was further purified by column chromatography (PE-EtOAc) to afford corresponding isoperfluoropropylated products (See Supplementary Methods).

General procedure for the photocatalytic isoperfluoropropylation of non-activated arenes

Under an ambient atmosphere, in a 25 mL screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stirring bar, arenes (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), PFPI reagent (166.4 mg, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv), [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 (1.8 mg, 1 mol%), were dissolved in dry MeCN (2.0 mL). Subsequently, 4 Å molecular sieves (50 mg) and TMEDA (59.8 μL, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was added into the vial. The vial was sealed and the reaction was irradiated at 450 nm for 16 h, the temperature of the reaction systems was controlled within 25–35 °C by using the drum fan. After this, the reaction was quenched with 10 mL 5% NaHCO3 aqueous solution, then extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under a vacuum. The residue was further purified by column chromatography (PE-EtOAc) to afford corresponding isoperfluoropropylated products. (See Supplementary Methods).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files, or from the corresponding author upon request. For supplementary figures, see SI, Figure S1-S16. For X-Ray crystallography of compound 5 and compound 8, see Supplementary Data 1 and Data 2. For Cartesian coordinates of the structures, see Supplementary Data 3. For NMR spectra, see Supplementary Data 4.

References

Wong, D. T., Perry, K. W. & Bymaster, F. P. The discovery of fluoxetine hydrochloride (prozac). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4, 764–774 (2005).

Purser, S., Moore, P. R., Swallow, S. & Gouverneur, V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330 (2008).

Meanwell, N. A. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 54, 2529–2591 (2011).

Mueller, K., Faeh, C. & Diederich, F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 317, 1881–1886 (2007).

Berger, R., Resnati, G., Metrangolo, P., Weber, E. & Hulliger, J. Organic fluorine compounds: a great opportunity for enhanced materials properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3496–3508 (2011).

Zhou, Y. et al. Next generation of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals, compounds currently in phase II-III clinical trials of major pharmaceutical companies: new structural trends and therapeutic areas. Chem. Rev. 116, 422–518 (2016).

Meanwell, N. A. Fluorine and fluorinated motifs in the design and application of bioisosteres for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 61, 5822–5880 (2018).

Charpentier, J., Früh, N. & Togni, A. Electrophilic trifluoromethylation by use of hypervalent iodine reagents. Chem. Rev. 115, 650–682 (2015).

Li, Z., García-Domínguez, A. & Nevado, C. Pd-Catalyzed stereoselective carboperfluoroalkylation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11610–11613 (2015).

Qing, F. L. et al. A fruitful decade of organofluorine chemistry: new reagents and reactions. CCS Chem. 4, 2518–2549 (2022).

Liang, T., Neumann, C. N. & Ritter, T. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8214–8264 (2013).

Chu, L. & Qing, F. L. Oxidative trifluoromethylation and trifluoromethylthiolation reactions using (trifluoromethyl) trimethylsilane as a nucleophilic CF3 Source. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1513–1522 (2014).

Chachignon, H. & Cahard, D. State-of-the-art in electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation reagents. Chin. J. Chem. 34, 445–454 (2016).

Liu, X., Xu, C., Wang, M. & Liu, Q. Trifluoro-methyltrimethylsilane: nucleophilic trifluoromethyla-tion and beyond. Chem. Rev. 115, 683–730 (2015).

Hansch, C. et al. Aromatic substituent constants for structure-activity correlations. J. Med. Chem. 16, 1207–1216 (1973).

Duan, J. J. W. et al. Structure-based discovery of phenyl (3-phenylpyrrolidin-3-yl)sulfones as selective, orally active RORγt inverse agonists. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 367–373 (2019).

Marcoux, D. et al. Rationally designed, conformationally constrained inverse agonists of RORγt-identification of a potent, selective series with biologic-like in vivo efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 62, 9931–9946 (2019).

Verrier, Y., Rey, P., Buzzetti, L. & Melchiorre, P. Visible-light excitation of iminium ions enables the enantioselective catalytic β-alkylation of enals. Nat. Chem. 9, 868–873 (2017).

Thomas, A. A. et al. Mechanistically guided design of ligands that significantly improve the efficiency of CuH-catalyzed hydroamination reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13976–13984 (2018).

Eignerová, B., Sedlák, D., Dračínský, M., Bartůněk, P. & Kotora, M. Synthesis and biochemical characterization of a series of 17α-perfluoroalkylated estradiols as selective ligands for estrogen receptor α. J. Med. Chem. 53, 6947–6953 (2010).

Luo, C. et al. Development of an efficient synthetic process for broflanilide. Org. Process Res. Dev. 24, 1024–1031 (2020).

Liu, X. H. et al. Copper-mediated aerobic iodination and perfluoroalkylation of boronic acids with (CF3)2CFI at room temperature. J. Fluor. Chem. 189, 59–67 (2016).

Qi, Q. Q., Shen, Q. L. & Lu, L. Polyfluoroalkylation of 2-aminothiazoles. J. Fluor. Chem. 133, 115–119 (2012).

Qin, H. et al. Palladium-catalyzed C2-regioselective perfluoroalkylation of the free (NH)-heteroarenes. J. Org. Chem. 86, 2840–2853 (2021).

Straathof, N. J. W. et al. Rapid trifluoromethylation and perfluoroalkylation of five-membered heterocycles by photoredox catalysis in continuous flow. ChemSusChem 7, 1612–1617 (2014).

Yuan, C., Dai, P., Bao, X. & Zhao, Y. Highly site-selective formation of perfluoroalkylated anilids via a protecting strategy by molybdenum hexacarbonyl catalyst. Org. Lett. 21, 6481–6484 (2019).

Leifert, D. & Studer, A. Iodinated (perfluoro)alkyl quinoxalines by atom transfer radical addition using ortho-diisocyanoarenes as radical acceptors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 11660–11663 (2016).

Lee, J. W., Spiegowski, D. N. & Ngai, M. Y. Selective C-O bond formation via a photocatalytic radical coupling strategy: access to perfluoroalkoxylated (ORF) arenes and heteroarenes. Chem. Sci. 8, 6066–6070 (2017).

Nair, H. K. & Burton, D. J. Perfluoroisopropylcadmium and copper: preparation, stability and reactivity. J. Fluor. Chem. 56, 341–351 (1992).

Miller, W. T. & Burnard, R. J. Perfluoroalkylsilver compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 7367–7368 (1968).

Chambers, R. D., Cheburkov, Y. A., MacBride, J. A. H., & Musgrave, W. K. R. The fluoride ion-catalysed rearrangement of 3,6-difluoro-4,5-bisheptafluoroiso-propylpyridazine. J. Chem. Soc. D. 23, 1647-1647 (1970).

Ono, S., Yokota, Y., Ito, S. & Mikami, K. Regiocontrolled heptafluoroisopropylation of aromatic halides by copper(I) carboxylates with heptafluoroisopropyl-zinc reagents. Org. Lett. 21, 1093–1097 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Direct isoperfluoropropylation of arenediazonium salts with hexafluoropropylene. Org. Chem. Front. 3, 304–308 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Direct heptafluoroisopropylation of arylboronic acids via hexafluoropropene (HFP). Chem. Commun. 52, 796–799 (2016).

Tong, C. L., Xu, X. H. & Qing, F. L. Oxidative hydro-, bromo-, and chloroheptafluoroisopropylation of unactivated alkenes with heptafluoroisopropyl silver. Org. Lett. 21, 9532–9535 (2019).

Tong, C. L., Xu, X. H. & Qing, F. L. Nucleophilic and radical heptafluoroisopropoxylation with redox-active reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 23097–23106 (2021).

Tong, C. L., Xu, X. H. & Qing, F. L. Regioselective oxidative C-H heptafluoroisopropylation of heteroarenes with heptafluoroisopropyl silver. Org. Chem. Front. 9, 4435–4440 (2022).

Hari, D. P., Caramenti, P. & Waser, J. Cyclic hypervalent iodine reagents: enabling tools for bond disconnection via reactivity umpolung. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3212–3225 (2018).

Yoshimura, A. & Zhdankin, V. V. Advances in synthetic applications of hypervalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 116, 3328–3435 (2016).

Calvo, R., Comas-Vives, A., Togni, A. & Katayev, D. Taming radical intermediates for the construction of enantioenriched trifluoromethylated quaternary carbon centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 1461–1466 (2019).

Sheng, J. et al. Cu-catalyzed π-core evolution of benzoxadiazoles with diaryliodonium salts for regioselective synthesis of phenazine scaffolds. Org. Lett. 20, 4458–4461 (2018).

Sheng, J., Wang, Y., Su, X., He, R. & Chen, C. Copper-catalyzed [2+2+2] modular synthesis of multisubstituted pyridines: alkenylation of nitriles with vinyliodonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4824–4828 (2017).

Bao, Z. & Chen, C. Efficient synthesis of cyclic imides by the tandem N-arylation-acylation and rearrangement reaction of cyanoesters with diaryliodonium salts. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 107913 (2023).

Ge, C., Wang, B., Jiang, Y. & Chen, C. Diverse reactivity of the gem-difluorovinyl iodonium salt for direct incorporation of the difluoroethylene group into N- and O-nucleophiles. Commun. Chem. 5, 167 (2022).

Wu, C. et al. Wet carbonate-promoted radical arylation of vinyl pinacolboronates with diaryliodonium salts yields substituted olefins. Commun. Chem. 3, 92 (2020).

Allen, A. E. & MacMillan, D. W. C. The productive merger of iodonium salts and organocatalysis: a non-photolytic approach to the enantioselective α-trifluoromethylation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4986–4987 (2010).

Matousek, V., Pietrasiak, E., Schwenk, R. & Togni, A. One-pot synthesis of hypervalent iodine reagents for electrophilic trifluoromethylation. J. Org. Chem. 78, 6763–6768 (2013).

Kochanowska-Karamyan, A. J. & Hamann, M. T. Marine indole alkaloids: potential new drug leads for the control of depression and anxiety. Chem. Rev. 8, 4489–4497 (2010).

Wiehn, M. S., Vinogradova, E. V. & Togni, A. Electrophilic trifluoromethylation of arenes and N-heteroarenes using hypervalent iodine reagents. J. Fluor. Chem. 131, 951–957 (2010).

Niedermann, K. et al. Direct electrophilic N-trifluoromethylation of azoles by a hypervalent iodine reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 6511–6515 (2012).

Ogawa, Y., Tokunaga, E., Kobayashi, O., Hirai, K. & Shibata, N. Current contributions of organofluorine compounds to the agrochemical industry. iScience 23, 101467 (2020).

Martín-Heras, V., Daniliuc, C. G. & Gilmour, R. An I(I)/I(III) catalysis route to the heptafluoroisopropyl group: a privileged module in contemporary agrochemistry. Synthesis 53, 4203–4212 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21871158 and 22071129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. designed and guided this project. Y.W. is responsible for the plan and implementation of the experimental work. Y.J and Y.W is responsible for the theory calculations. Y.W. wrote the manuscript. F.W and B.W discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, F. et al. Direct electrophilic and radical isoperfluoropropylation with i-C3F7-Iodine(III) reagent (PFPI reagent). Commun Chem 6, 177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-023-00986-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-023-00986-3

This article is cited by

-

Selective radical-type perfluoro-tert-butylation of unsaturated compounds with a stable and scalable reagent

Nature Communications (2025)