Abstract

This paper presents DATRAS (Dual Active Tilted Roller Actuation System), a compact robotic system for vascular interventions that integrates with electromagnetic actuation systems to enable complete teleoperation. DATRAS combines translation and rotation motion for intervention tools in a single module, simplifying design and control. The system also allows easy roller adjustment for various tool diameters and enables guidewire helical motion without additional components or specialized guidewires. Experimental validation using cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantoms demonstrates DATRAS’s effectiveness in controlling magnetic tip guidewire motion when combined with electromagnetic actuation. Weighing just 320 g, this lightweight device aims to enhance interventional procedures by facilitating easy manipulation of instruments through teleoperation. The actuator addresses current limitations in robotic intervention systems, exhibiting a potential reduction in radiation exposure and ergonomic risks for medical professionals, ultimately improving the efficacy of vascular interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetically controlled micro-scale robots and intervention tools, both untethered and tethered, offer unprecedented capabilities for minimally invasive medical procedures. These magnetically actuated micro-robots and magnetically controlled guidewires and catheters enable targeted drug delivery, remote diagnostics, and high-precision vascular interventions (VI) by navigating complex vascular geometries1,2,3,4,5,6,7 such as directed motion through neurological pathways for localized drug delivery, organ and tissue penetration as well as navigation through gastrointestinal tract for localized treatments. Magnetic actuation of VI tools offers precise control through complex biological structures as magnetic fields can penetrate biological tissues with minimal interaction and are safe over a wide range of operating frequency8,9,10. To leverage the benefits offered by magnetic manipulations, we have previously developed various EAS and magnetically responsive intervention tools, such as magnetic tip guidewires facilitating active tip steering inside complex blood vessels and treating various vascular diseases1,11,12,13. Our developed EAS and magnetic tip guidewire work together, enabling precise tip steering inside complex and tortuous anatomy. However, EAS and magnetic tip guidewire alone cannot accomplish a complete remote operation. A robotic actuator is required to manipulate and navigate the intervention tools inside blood vessels remotely. There are robots that enable remote actuation of guidewires and catheters, but they suffer from multiple limitations such as large physical footprint, complex mechanisms for multi-DOF actuation, fixed guidewire sizes, high setup time, and difficulty in portability, etc., which are discussed in more detail in the subsequent sections. This work reports on a compact actuator with two actively controlled tilted rollers or Dual Active Tilted Rollers (DATRAS) for VI tool manipulations that can work alongside an EAS to enable complete teleoperation. Figure 1 shows a schematic of an envisioned clinical setting of a robotic assisted VI procedure where our in-house developed magnetic tip guidewire and our in-house developed EAS were used to steer the guidewire.

Vascular diseases caused by plaque obstruction of blood vessels are among the leading causes of mortality worldwide14,15,16,17,18,19,20. This prevalence has drawn significant attention from the medical and scientific communities, spurring advancements in safer and higher efficacy treatment methodologies. Vascular interventions are minimally invasive procedures that have become the gold standard for treating many of these conditions21. These procedures involve navigating flexible, thin instruments such as guidewires and catheters through the vascular system to access and treat affected areas, and gaining safe access to affected vessels is the first critical step in the standard diagnostic and therapeutic procedures14,22,23. The procedural workflow typically involves the following steps. First, vascular access is established via the femoral artery using an introducer sheath. Next, a guidewire is advanced through the introducer and navigated to the target lesion under fluoroscopic guidance. However, these procedures are associated with inherent risks, not just for patients but also for medical professionals. The current standard for imaging during VI is X-ray fluoroscopy. This imaging modality exposes the interventionalists to a significant amount of radiation24. Chronic exposure to even low doses of X-ray radiation has been linked to severe health concerns, including left-sided brain tumors, cataracts, melanoma, and premature vascular and neurological aging13,25,26. To mitigate these risks, medical professionals employ protective equipment such as lead aprons, gloves, goggles, thyroid protection scarves, lead caps, etc. However, these protective gears are often heavy and cumbersome to wear, leading to their own set of problems. Studies have shown a significantly higher prevalence of orthopedic issues among professionals who regularly performed fluoroscopy-guided procedures13,26,27,28,29 wearing heavy protective gears.

Robotic systems for vascular interventions have emerged as promising solutions to address these challenges by enabling remote operation. These systems aim to distance the operator from the radiation source while maintaining or even enhancing procedural precision30,31,32 and reducing health hazards33,34,35,36,37. Early clinical data suggests that Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), which is one of the VI procedures performed with robotic assistance, can lower the risk of procedural complications by up to 50%38. Current robotic systems employ various mechanisms for tool manipulation, including rollers and grippers to actuate intervention tools such as guidewires or catheters inside vasculatures. Manipulation of these intervention tools primarily involves translation and rotation. During VI, interventionalists use their fingers to propel and twist the guidewire to navigate inside the blood vessel. Translation is the primary motion required to deliver a tool to a target region. Rotation helps with translation motion by reducing static friction while navigating through tortuous vessels14. Rotation also helps to reduce the ‘whip’ of the guidewires and thus reduces instabilities and chances of damaging blood vessels14. A rotating guidewire tip can help cross lesions or break down plaque deposits, enabling further progression through calcified lesions or occluded vessels by introducing a drilling force39. For passive guidewires, rotation is also used to select the desired branch at vessel bifurcation during navigation40. Hence, most robotic actuators aim to achieve 2 degrees of freedom (DOF) to facilitate translation and rotation. Many research studies have been carried out to develop and build vascular intervention robots to assist interventionalists34,39,41,42. Despite many efforts and advancements, existing robotic systems for VI still have the following limitations: (1) Robots have large physical footprints, occupy significant space in the operating room, and require extensive setup time. This issue generally originates from complex mechanism design. Robots that allow both translation and rotation have separate mechanisms for each degree of freedom, which leads to a large physical form factor. (2) Robots are not portable and modular. Many of them require large support structures next to the patient’s bed, such as a sliding table, sliding rail, or a robotic arm. Some examples of commercial robots using large supports or robotic arms are CorPath GRX (Corindus Vascular Robotics, MA, USA), Magellan (Hansen Medical Inc., CA, USA), R-One (Robocath Inc., Rouen, France), etc. Many of the robots are also made to accommodate only a fixed-size (diameter) guidewire, so they lack flexibility and, hence, fail to fit different-size intervention tools.

Most existing robots for VI use one of the following types of manipulation mechanisms: (1) friction wheels or roller mechanism, (2) reciprocating propulsion with a sliding platform, and (3) belt pulley and gear transmission mechanism. The CorPath GRX has two modules for 2 DOF: one module uses friction rollers to translate the guidewire, and another module rotates to achieve rotation of the guidewire, and the system also requires a robotic arm to place it next to the patient25. Similar types of robots43,44 with friction wheels and two modules for translation and rotation were built in a more compact form; however, these robots have gear transmission mechanisms that inherently suffer from backlash problems45,46, along with the possibility of position overshoot when a sudden stop is required as the rotation module rotates the entire translation module. Inertia and momentum can cause unwanted deviations in such a mechanism. Another research47 built a reciprocating device that can translate and rotate the guidewire; however, this robot uses a rather complex electromagnetic grasping mechanism to first clamp the guidewire and achieve 2 DOF through a reciprocating mechanism. Such grasping mechanisms require fine control of the grasp force on the tool; otherwise, they can damage the tool’s surface. The commercial robot R-One (RoboCath Inc., Rouen, France) also uses graspers and reciprocating motion to generate translation and rotation of the guidewire. These types of robots have a limited stroke length; therefore, their manipulation speeds and feeding amounts are limited. Because the grippers for this type of robot need to travel a certain distance (stroke length) to actuate the guidewire, the size of these robots is larger, and they need to be placed far from the insertion point, which introduces buckling issues for the catheter or guidewire48. Another research49 built a robot with a gripper transmission mechanism mounted on a sliding table or sliding rail, which further limits the stroke length and adds a greater number of mechanisms, thereby increasing the complexity. A commercial robot, Magellan50,51 (Hansen Medical Inc., CA, USA), operated with a belt-pulley mechanism to achieve translation and rotation. This mechanism is heavy, bulky, and involves complex controls. In addition to mechanical and control complexities, commercial robots for vascular interventions are expensive52,53,54. A similar type of robot combines both a sliding rail and pully transmission for tool manipulation26 and suffers from the same limitations.

A comparison sketch (Supplementary Fig. 1) of different robotic systems shows some of the limitations associated with the current state-of-the-art. Colored regions indicate the required components and features of the specific robot for operation. All other robots compared require two mechanisms for initiating translation and rotation, and they all need large-size support structures for installation. This comparison shows that DATRAS requires only one mechanism to generate 2 DOF, and it does not require any large support structure for installation and operation. Supplementary Table 1 shows a comprehensive comparison of DATRAS with commercially built robots, clearly showing how the mechanical design of DATRAS offers significant advantages over existing designs. All the previously mentioned limitations of existing robotic actuators for VI can potentially slow the growth of robot assisted VI. We draw inspiration from the present limitations and design an effective actuator that may encourage the growth of robot assisted VI by making actuators small, compact, and easy to set up and use.

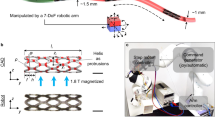

The proposed DATRAS design utilizes a single mechanism consisting of dual-active tilted rollers to impart both translation and rotation to a guidewire simply by changing the direction of rotation of the rollers. The inclusion of a lead screw mechanism to adjust the distance between the two rollers also enables the accommodation of guidewires of different diameters. DATRAS has a very competitive physical footprint compared to other robots. The overall structure and the working principles (Fig. 2) of DATRAS are simple and compact compared to other systems. DATRAS showcases the following contributions

-

The simplest mechanism to achieve translation and rotation of the intervention tools. The unified actuation approach significantly simplifies the overall design. This design also allows translation and rotation to be combined into a helical or screw-type motion, which is useful for overcoming high friction and sharp bends. The DATRAS also enables the accommodation of guidewires of different diameters using a small adjustable lead-screw mechanism.

-

Unlike many existing systems, the DATRAS does not require additional support structures, such as robotic arms or sliding rails, for installation and operation. This self-contained design can significantly reduce setup time and complexity, potentially improving workflow efficiency in interventional procedures.

-

The simplicity of mechanical design has the potential to reduce manufacturing costs remarkably compared to the existing robots. All the parts for this system are modular and can be easily 3D printed and modified if required. This modularity and cost-effectiveness could facilitate a wider adoption of robotic assistance in VI, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

a The overall dimension of DATRAS is showing its compactness. b (i) A translation motion is created by rotating the rollers in opposite direction with the same angular velocity. ii Rotating the rollers in the same direction with the same angular velocity makes a rotation motion of the guidewire. iii Rollers rotating with different angular velocities generate a helical motion of the guidewire.

Results

System kinematics

The actuator was designed based on two actively controlled tilted rollers. Friction-based roller systems do not require a specific stroke length and have no limit on feeding amount, and they can be installed close to the patients as there are no reciprocating parts moving forward and backward, which reduces the risks of tool buckling48,55. The motion of the intervention tool or the guidewire is created by the frictional force components at the contact points between the rollers and the guidewire. The tilted roller configuration decomposes the frictional force into two components: tangential and normal forces. To create a translational motion of the guidewire, DATRAS utilizes the tangential force components, and to create a rotational motion of the guidewire DATRAS utilizes the normal force components. A simplified kinematic relationship has been derived to relate the roller speeds to guidewire motion (Fig. 3). The guidewire is assumed to be a rigid body, so all points on the guidewire will have the same velocity, and the velocity is estimated by taking the average no slip velocities from the two rollers. The body velocity of the guidewire in the body frame \(({V}^{{body}})\) and the velocity in the inertial frame \(({V}^{{inertial}})\) are indicated in Fig. 3. The relationships between the body frame and the inertial frame are: \({{u}_{x}}_{1}=R{\omega }_{1}\cos \theta ,{{u}_{x}}_{2}=R{\omega }_{2}\cos \theta ,{{v}_{y}}_{1}=R{\omega }_{1}\sin \theta ,{{v}_{y}}_{2}=R{\omega }_{2}\sin \theta\), and the sign changes depending on the direction in which they are rotating.

A guidewire is inserted through the guide tube, and the roller rotation imparts either translation or rotation to the guidewire. The angular velocities (\({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2}\)) of the rollers are used to produce linear (\({V}_{t}\)) and angular velocity \((\Omega )\) of the guidewire. The guidewire body velocities \(({V}^{{body}})\) are on the left, and the inertial velocities \(({V}^{{inertial}})\) are on the right. Both rollers have the same radius \(R,\) and the guidewire radius is \(r\left({diameter}=d\right)\).

DATRAS generates a translation motion of the guidewire by rotating the rollers in the opposite direction. This translation motion is the tangential velocity \(({V}_{t})\) of the guidewire in the \(X\) direction, which can be expressed as

where \(\theta\) is the tilt angle of the rollers, and \({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2}\) are the roller angular velocities, and \(R\) is the radius of both rollers, as the rollers have the same dimensions. The normal velocity \(({V}_{n})\) in the \(Y\) directional velocity is \({V}_{n}=\frac{1}{2}({{v}_{y}}_{1}-{{v}_{y}}_{2})=\frac{R}{2}\sin \theta ({\omega }_{1}-{\omega }_{2})\). However, the effective \(Y\) direction velocity can be considered zero as the guidewire motion in the vertical direction is resisted by the guide tube. Therefore, considering infinite resistance from the guide tube’s wall, the normal velocity, \({V}_{n}\cong 0.\) In our setup \(\theta ={30}^{\circ }\), changing the tilt angle \((\theta )\) changes the magnitude of the propulsion force and the velocity components in the \(X\) and \(Y\) direction. A different tilt angle could be selected; for example, a \(\theta ={45}^{\circ }\) will decompose the friction force components into equal magnitudes and theoretically optimize both translation and rotation. However, this configuration also increases the vertical force component, which, while beneficial for initiating rotation, poses other problems. Excessive vertical force can lead to plastic deformation of the guidewire. Similarly, roller radius \((R)\) also impacts the system performance. While a smaller radius could reduce the overall size and weight of the device, it must maintain enough surface contact to generate sufficient friction for reliable force transmission. If the roller radius becomes too small, the contact area diminishes, resulting in reduced friction force. This reduction in friction can lead to slippage between the rollers and the guidewire, especially when the guidewire navigates through tortuous or high-friction regions of vasculatures. Suggesting the best \(R\) and \(\theta\) is not so straightforward, and as this work represents an early-stage proof of concept, we prioritized demonstrating the fundamental functionality and advantages of our design rather than optimizing various parameters.

To impart a rotational motion to the guidewire, the rollers are rotated in the same directions with the same angular velocities. This rotational velocity \(\left(\Omega \right)\) of the guidewire can be expressed by,

where \(r\) is the radius of the guidewire and \(d\) is the diameter. The inputs \(({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2})\) and the outputs (\({V}_{t}\) and \(\Omega\)) of the system can be expressed as

Equation (3) relates the angular velocities of the rollers with the linear and the rotational velocities of the guidewire. An angular speed differential between the two rollers will generate a helical motion of the guidewire. The pitch can be estimated as

The angular velocity difference between the two rollers, when rotating in the opposite direction, will result in a larger pitch or a translation dominant helical motion, and the angular velocity differential when the rollers rotate in the same direction will result in a smaller pitch or rotation dominant helical motion. Due to the roller’s tilted orientation even with one active roller, DATRAS can generate a helical motion (shown in Supplementary Movie 2).

The linear velocity model of the guidewire related to the roller speeds of the system was validated through simple experiments. The validation work was limited only to the linear velocity of the guidewire. Experimentally measuring the true angular velocity of the guidewire presents significant challenges due to its small diameter (0.36 mm) and high flexibility. The front portion of the guidewire, which includes a magnetic tip measuring 3 mm in length and 0.3 mm in diameter and weighing 1.6 mg, tends to bend under its own weight. This bending or displacement from the rotational axis is further exacerbated when the guidewire is rotated, resulting in off-axis and floppy motion at the tip, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 11. A high-speed optical system with motion-tracking capabilities could be employed to capture angular velocities. However, such non-contact, marker-free measurement systems are costly and may not be suitable for use in a surgical environment due to their complexity and potential interference with clinical procedures. Additionally, the practical value of obtaining precise angular velocity data is limited in real-world surgical scenarios, particularly when combined with an EAS. In systems where magnetic actuation methods such as the Niobe (Stereotaxis, St. Louis, USA), the Genesis (Stereotaxis, St. Louis, USA) and the Aeon Phocus (Aeon Scientific AG, Zurich, Switzerland) are employed, the steering of the guidewire is primarily controlled by the magnetic manipulation of the guidewire tip without rotating, allowing precise directional adjustments without relying heavily on rotational input from the rollers. This magnetic actuation offers a higher degree of control over the guidewire’s orientation, rendering the need for exact angular velocity less critical. On the other hand, linear velocity directly governs the guidewire’s forward motion through vasculatures, and the information on linear velocity can help to estimate the length of the lesions inside the vasculatures56,57 by knowing the distance traveled by the guidewire. A simple experiment was conducted to measure the linear velocity of the guidewire in relation to the speeds of the rollers. The experimental linear velocities (Supplementary Fig. 2) of the guidewire were measured related to some specific sets of roller velocities and were compared with the theoretical guidewire velocities. The guidewire linear velocities were measured with two different roller gaps \(({l}_{1}\) and \({l}_{2})\) to observe how the grip of the rollers on the guidewire affects its velocities. The desired roller velocities were directly fed to the motor controllers, and the controllers kept the motors running at the commanded velocities. The controllers were configured and tuned using the MAXON ESCON (MAXON Group, Sachseln, Switzerland) Studio GUI before the experiments. The roller velocities were varied from 1 to 21 RPM with a 2 RPM step size and the measured guidewire velocities were plotted against the associated theoretical velocities. Each experiment was repeated 5 times to observe the consistency of the system’s performance. Figure 4 shows the observed differences between the theoretical and experimental velocities. The experimental velocities tend to diverge from theoretical predictions, with the widening roller gap and increasing speeds. This suggests that certain unmodeled effects become more prominent at higher speeds, affecting the accuracy of the theoretical model.

a Experimental results with a roller gap of 0.35 mm show that for each experiment, the experimental values are very concentrated and do not have wide variations. As the velocity increases, the difference between the mean experimental and theoretical velocities increases. b A roller gap of 0.33 mm makes the experimental velocities more concentrated, and the variations are even smaller than the 0.35 mm gap. As the velocity increases, the difference between the mean experimental and theoretical velocities increases. However, this is less than the difference observed for a roller gap of 0.35 mm.

In the experimental setup, the guidewire had a diameter of 0.36 mm. When the rollers are pressed against the guidewire, the surface of the rollers undergoes small elastic deformation due to the roller surface being made of hard rubber. At the beginning, the roller gap was kept at 0.35 mm, and then it was reduced to 0.33 mm. The gap is adjusted by the lead-screw mechanism (1 mm pitch). For both cases, the guidewire velocities related to the roller RPMs were consistent with repeated experiments. No considerable variations were observed in experimental data for the lower speed range of 1–12 mm/s. However, higher speeds lead to more deviations from the theoretical values for both cases. Figure 5 shows the mean velocity (mean of five experiments) for each experiment against theoretical velocities, along with the associated roller or motor speeds. This plot better represents how the guidewire velocity is related to the roller speeds.

Decreasing the gaps between the rollers \(({l}_{1}\) and \({l}_{2})\) also decreases the mean error and the maximum error. In both cases, as the velocity increases, the errors also increase. For a tighter roller gap of 0.33 mm, a maximum error of 4.40 mm/s is produced for a maximum theoretical guidewire velocity of 21 mm/s.

A roller gap of 0.35 mm produced a maximum error of 6.70 mm/s, and a roller gap of 0.33 mm produced a maximum error of 4.40 mm/s. A smaller roller gap improves the grip of the rollers on the guidewire and friction between the rollers and the guidewire, thereby improving the transmission of force. Consequently, the experimental results show that \({l}_{2}=0.33{mm}\) produces less error compared to the roller gap \({l}_{1}=0.35{mm}\). These results indicate that the force transmission improves as the distance between the rollers decreases or the ‘pinch’ force of the rollers on the guidewire increases, and the system performs the best for slower velocities, which is important for vascular interventions. It is important to note that too much force can damage the guidewire and cause excessive friction at the contact, which can cause the guidewire to be stuck and the rollers to slip. It is, therefore, required to set up the rollers in such a way that they can hold the guidewire well with sufficient friction. While Figs. 4, 5 identify a basic linear trend in velocity error, they do not efficiently capture the nonlinearities across different speeds that arise due to many unmodelled real-world factors. Figure 6a shows residual analysis which is the difference between the theoretical velocities and the mean experimental velocities of the guidewire. At lower motor speeds (1 ~ 12 RPM), the residuals for both conditions (0.35 mm and 0.33 mm roller gaps) tend to be smaller, suggesting that the experiments aligned better with the theoretical predictions. As the motor speed increases, however, residuals fluctuate significantly, indicating a larger deviation between the theoretical and experimental velocities. This behavior suggests nonlinearities within the system that become more pronounced at higher speeds.

a The residuals are calculated as the difference between the theoretical velocities and the experimental velocities. The residuals for both roller gap conditions fluctuate as the motor speeds increase, indicating that the difference between the theoretical and experimental velocities is not constant across the speeds. This also indicates unmodeled nonlinearities. b The speed ratio is defined as the ratio of experimental mean velocities to theoretical velocities. The speed ratio for both roller gap conditions is generally below 1, indicating the underperformance of the system. However, for a roller gap of 0.33 mm, the speed ratio is more stable and closer to 1 (unity), suggesting more efficient performance.

Figure 6b also shows that at lower speeds for both roller gaps, the speed ratio is closer to 1(unity), indicating better efficiency of the system. The speed ratio (taken as the ratio of experimental mean velocities to theoretical mean velocities) curve for a roller gap of 0.33 mm is more stable due to better frictional engagement between the guidewire and the rollers. Both plots indicate divergence from the ideal behavior. Such deviations from theoretical predictions could be attributed to real-world inefficiencies or nonlinearities such as slip, dynamic friction effect or the change in friction behavior as the speed increases, mechanical hysteresis originating from the material deformation at the contact point of the guidewire and the rollers, etc.

We assume that at elevated speeds ( >12 RPM), the transition from static to dynamic friction reduces the effective frictional force between the rollers and the guidewire. At lower speeds, static friction dominates, ensuring near-ideal no-slip conditions. However, as speed increases, kinetic friction becomes predominant, causing partial slippage and velocity deviations. Additionally, misalignments of the coupler, motor shaft, and roller axes, due to the limitations of 3D printing in system assembly, result in non-uniform contact between the rollers and the guidewire, thereby reducing system efficiency. These effects are amplified at higher speeds, exacerbating slippage and reducing transmission efficiencies. Moreover, rubber rollers undergo elastic deformation under loading, which diminishes effective contact at higher speeds. At higher rotational speeds, this deformation becomes more pronounced, altering the contact area and force distribution in a nonlinear manner.

To enhance the system performance, the current rubber rollers can be replaced with other materials that have a higher friction coefficient to reduce slip. Materials with higher wear resistance can also maintain consistent contact properties over extended usage, minimizing performance degradation at higher speeds. We assume that rollers with surface textures can further improve grip and yield more consistent performance at higher speeds. Increasing the roller radius would enhance the surface contact area with the guidewire, improving frictional engagement and reducing the likelihood of slippage at higher speeds. However, this modification would increase the physical footprint of the system. A parametric study is planned to optimize the roller radius for a balanced design.

Theoretically modeling all nonlinearities, including an optimum roller gap and friction force, is challenging and will widely vary depending on the roller and guidewire material properties; hence, an in-depth analytical optimization method was not pursued. Instead, from the experimental data analysis, a potential velocity regime (1 ~ 12 mm/s) with errors less than 5 mm/s, which is less than 20% error for both roller gaps (0.33 mm and 0.35 mm) was suggested for a more reliable operation. As the guidewire is advanced in a slow and careful fashion for accessing blood vessels14,43 in a practical situation, the higher errors associated with higher velocities can be disregarded. Additionally, the control method is an open loop control, and a human operator operates the system without the need to keep a constant velocity. Instead, successfully executing navigation through vessels with translation and rotation motion capability was prioritized over precise velocity magnitudes.

System functionality

The fundamental motions created by DATRAS without using any magnetic field for active tip steering are demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 1 and Supplementary Movie 2. These movies show the guidewire’s translation motion and rotation as well as a helical motion inside a cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantom. These demonstrations show that the same number of degrees of freedom (translation and rotation) can be produced by DATRAS instead of designing complex and large mechanisms like the existing robots mentioned in the earlier sections. Besides having translation to reach the target region, a rotational motion can be useful to untwist a guidewire if it gets tangled or twisted while crossing complex regions. Kinking and twisting of the guidewire are highly undesirable, however, in the real world, it is impossible to have a smooth motion of the guidewire inside the blood vessel due to friction, vessel complexity, and the guidewire being very flexible. A rotational motion is used to retrieve the guidewire from a twisted position. Supplementary Movie 3 shows how rotational motion from DATRAS can be useful when a guidewire gets twisted due to excessive friction. This video shows a guidewire’s front portion getting twisted while traversing through a cerebrovascular phantom. Using rotation, the high static friction was overcome, and the guidewire was untwisted. On top of translation and rotation, DATRAS is also capable of producing a helical type of motion that other existing robots do not offer with their mechanisms. This motion helps convert the static friction into a dynamic friction regime, assists in crossing sharp bends, and can produce a penetration effect58 through blockages. Supplementary Movie 4 shows an uncoated cerebrovascular phantom with high vessel wall friction and a sharp, almost 90-degree bend easily crossed by a helical motion, while the translation motion had difficulty crossing the bend. A previous study14 also found that helical motion is useful for crossing challenging geometries without damaging vessel tissues; however, this study uses a special threaded guidewire to create helical motion.

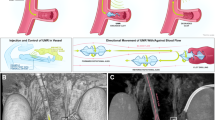

A successful demonstration of the functionalities of DATRAS was shown by executing combined operation with our in-house developed EAS by actuating our in-house developed magnetic tip guidewire inside a 2D phantom and more complex 3D geometries of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantoms in two conditions: (1) a lubricant coated set of phantoms representing a wet or realistic blood vessel friction conditions and (2) an uncoated set of phantoms representing higher friction conditions. Supplementary Movie 5 shows how our EAS assists the navigation of a magnetic tip guidewire inside a 2D phantom. DATRAS advances the guidewire and rotates it in the correct navigation direction. When a curved branch needed to be accessed, a magnetic field (20 mT) was applied to actively bend the guidewire to enter the branch and reach the target. The demonstration shows guidewire moving to a total of 3 targets. This phantom had no coating; therefore, it had more friction, and some slip is also observed in the video during faster roller rotations, where a lag between the roller rotation and guidewire motion is observed. Supplementary Movie 6 demonstrates navigation with EAS inside cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantoms. Without active bending of the tip of the guidewire, it is impossible to enter sharp curves. A combined operation of the DATRAS and EAS offers the highest degrees of freedom during navigation and enables remote operation as both systems are controlled remotely with joysticks. Our in-house EAS12 consists of 10 individually controlled electromagnetic coils. The magnetic torque \(({Nm})\) and the force \((N)\) at the guidewire tip can be expressed and calculated as

where \(M\) is the magnetic moment \(\left(A.{m}^{2}\right)\) and \(B\) is the applied magnetic field flux density at the location of \(M\) in Tesla \(\left(T\right).\) The currents required to generate the desired torque and force are calculated using the same approach as follow59

In addition to DATRAS’s functionalities, understanding the forces that derive the motion is essential. Figure 7 shows the components of friction forces responsible for creating motion (Fig. 7a showing translation and Fig. 7b showing rotation) acting at the contact points between the guidewire and the rollers. The total tangential force \(({F}_{x})\) and the normal force \(({F}_{y})\) are:

Here, \({\mu }_{s}\) is the static friction coefficient between the roller and guidewire surface, and \({N}_{1}\) and \({N}_{2}\) are the normal reactions that force the rollers to apply to the guidewire. The normal reaction forces depend on the material properties of the rollers and the guidewire as well as the type of contact formed at the point of contact, meaning how well the rollers grip the guidewire (distance between the rollers). The calculation of these normal reaction forces is highly nonlinear and challenging55 as they involve complex contact mechanics. Accurately measuring forces at the microscale interface between the rollers and guidewire also presents significant technical challenges. Introducing force sensors to monitor reaction forces could alter the system’s dynamics, compromising the simplicity and compactness of our design. An alternative way of approximating the propulsion forces is utilizing motor torque information. The fundamental principle underlying this approach is the conversion of motor torque \((\Gamma )\) to propulsion force at the contact point between the rollers and the guidewire. This relationship can be expressed as,

a When the rollers rotate in the opposite direction, the longitudinal force \({F}_{x}\) creates a linear motion, while the force component \({F}_{y}\) get canceled out by the reaction forces from the guide tube wall; hence, the velocity in \(Y\) direction is zero. When two rollers rotate at different speeds, there is a small moment \({M}_{y}\) acts around the \(Y\) axis. However, this moment gets canceled by the infinite lateral resistance from the guide tube wall. b When two rollers rotate in the same directions with the same speeds, the two \({F}_{y}\) components create a torque \({\tau }_{x}\) around the \(X\) axis, and the guidewire starts rotating.

The roller radius \(R\) is constant, so depending on the load (e.g., pinch force of the rollers, friction at the contact surface, environmental friction, etc.), torques \({\Gamma }_{1}\) and \({\Gamma }_{2}\) will change, and this will give us a more simplified method of approximating propulsion forces. Using such a simplified approach, propulsion force can be estimated in real-time without additional sensors, and monitoring of torque information can help to detect slip or increased friction from the environment, which can also be used to integrate with a haptic feedback system. Experiments were done to estimate the differences in the propulsion forces by actuating a guidewire inside a phantom coated with lubricant simulating real blood vessel friction properties and another uncoated phantom representing a harsher friction environment. As the frictional environment changes, the motor torque changes, and therefore the propulsion force changes. This approach provides a balance between experimental feasibility and system complexity, avoiding the need for additional experimental setups that could increase the overall physical and electrical footprint of the system. To enhance torque measurements in the future, integrating miniature strain gauges or piezoelectric force sensors within the roller assembly could provide direct measurement of contact forces and torques, further improving the system’s accuracy and reliability.

Motor torque \((\Gamma )\) is related to the motor current as,

Motor torque constant \(\left({K}_{m}\right)\) is acquired from the motor data sheet, and the motor current \((I)\) was recorded to calculate the required propulsion force for translation from Eq. (4). The guidewire was actuated inside a coated and uncoated cerebrovascular phantom, and motor current changes were recorded at 1 Hz. Figure 8a shows the cerebrovascular phantom with the guidewire trajectory. Figure 8b, c shows the guidewire propulsion force inside the coated and an uncoated cerebrovascular phantom, respectively. The peak propulsion force recorded in the coated phantom was 0.048 N, and the peak propulsion force was 0.059 N in the uncoated phantom. There are visibly more peaks (total 12) in the uncoated phantom that is over 0.048 N, and the mean propulsion force in the coated phantom is 0.014 N and 0.023 N for the uncoated phantom, which is about 1.6 times higher. This is due to increased vessel wall friction inside the uncoated phantom. Similarly, Fig. 8d shows the trajectory for the guidewire in a cardiovascular phantom. Figure 8e, f shows the propulsion force differences for the coated phantom and the uncoated phantoms. The maximum force for the coated phantom was 0.036 N, and the maximum force for the uncoated phantom was 0.054 N. In the uncoated phantom, 46 force peaks exceeded the maximum force of 0.036 N compared to the coated phantom. The mean propulsion force was 0.011 N for the coated phantom and 0.030 N for the uncoated phantom, which is 2.7 times higher. An increased travel time was observed for the two uncoated phantoms due to more resistance from the vessel wall. The cerebrovascular phantoms’ travel path had an average diameter of 5 mm, and the cardiovascular phantoms’ travel path had a mean diameter of 23 mm. Due to the larger diameter, it was relatively easier to advance the guidewire inside the coated cardiovascular phantom. In all the phantoms with different frictional environments, DATRAS was able to generate translation, rotation, and helical motion for the magnetic tip guidewire, and the guidewire was able to reach targets as well as correct itself when kinking or twisting happened.

a Traversed path in the cerebrovascular phantom. b The peak guidewire propulsion and the mean propulsion forces were 0.048 N and 0.014 N, respectively, for the coated phantom. c The peak for the uncoated phantom was 0.059 N with a mean propulsion force of 0.023 N. d Traversed path in the cerebrovascular phantom. e The coated phantom has a mean propulsion force of 0.011 N and a peak of 0.038 N. f The peak guidewire propulsion force in the uncoated cardiovascular phantom was 0.054 N, and the mean propulsion force was 0.030 N.

In all the experiments with coated and uncoated phantoms, the gap between the rollers was kept at 0.33 mm and was not varied. One notable limitation of the propulsion force analysis for different phantoms is that operator skills can introduce potential force variability during guidewire manipulation. Less experienced operators may inadvertently cause the guidewire to collide with vessel walls, leading to higher recorded forces that may be more reflective of manipulation techniques and skills rather than real intrinsic frictional characteristics of the phantoms. A more skilled operator might be able to navigate smoothly and avoid collisions, resulting in lower propulsion forces and shorter manipulation time. Nonetheless, we did notice guidewire getting more stuck on the wall of the uncoated phantoms during the experiments, which clearly indicates harsher frictional environments. Supplementary Movie 7 demonstrates the manipulation differences between the coated cerebrovascular and the uncoated cerebrovascular phantom with DATRAS combined with EAS. It was observed that by combining DATRAS with EAS, a curved target branch can be entered easily within 37 s, while in the uncoated phantom, all attempts failed to reach the target even after 2 min as the tip of the guidewire gets stuck with the vessel wall and twists severely. Movie 8 shows a similar experiment with the coated and the uncoated cardiovascular phantoms. For the coated cardiovascular phantom, entry to the target site was possible in 24 s, while the uncoated phantom took about 1 min 25 s. We applied a 20 mT magnetic field in the desired direction for all the experiments.

Figure 9a, b shows snapshots of one of the guidewire navigation experiments with DATRAS and EAS for all the phantoms. The start and the target points are marked in the figures. Figure 9a shows the guidewire inside the coated neurovascular phantom reaches the target in 40 s, while in the uncoated neurovascular phantom, the guidewire tip is still far from the target. At 20 s, buckling of the guidewire is observed in the high friction uncoated phantom. In Fig. 9b, the guidewire operates within a coated and uncoated cardiovascular phantom, and the guidewire reached the target at 40 s, but it failed to reach the target at 40 s inside the uncoated phantom. Buckling was also observed at 30 s and 40 s in the high friction uncoated phantom. This shows the difference in smoothness of guidewire manipulation in the coated and uncoated phantoms. In high-friction environments, the guidewire frequently gets stuck and experiences buckling if there’s a high propulsion force from the actuator. To overcome such situations, we use rotation and helical motion from DATRAS, which have been discussed before. Due to increased friction, navigating the guidewire inside the uncoated phantoms takes more time and effort.

a Guidewire reaches the target in 40 s in the coated cerebrovascular phantom, while in the uncoated phantom, it is still far from the target at 40 s and experiences buckling due to high friction. b Guidewire reaches the target in 40 s in the coated cardiovascular phantom and experiences buckling at 30 s and 40 s and fails to reach the target in 40 s.

In a real-world scenario during the operation, a significant change in propulsion forces would indicate changes in the frictional resistance of the environment. This information could be useful as a haptic input to understand the resistance from the environment and enhance the sense of realism of the operators. Based on varying friction conditions within the phantom, motor torque, and consequently propulsion force, change. These changes in motor torque magnitudes can be translated into haptic feedback, such as gamepad vibration intensities, where stronger resistance inside the phantom would result in more intense vibration amplitudes. In future work, we aim to correlate changes in motor torque or propulsion force with joystick vibration amplitude. We plan to integrate a programmable joystick with the current ros2_control framework, along with developing an algorithm that appropriately scales the motor torque or propulsion force changes into joystick vibration. This simulation of resistive forces through tactile feedback will enhance operational safety and provide a more intuitive control experience for the operator.

As the current system operates under open-loop control, this study emphasizes velocity metrics to validate the kinematic model. However, the positional precision of the guidewire is the ultimate determinant of clinical utility. Although the guidewire successfully navigated to target locations within the phantoms using the EAS, future studies should implement techniques to localize the guidewire tip and precisely estimate positional errors using closed-loop control. Positional accuracy in open-loop systems largely depends on the operator’s skills. Integrating X-ray or optical tracking of the guidewire within a 3D environment along with a closed-loop control algorithm will enable accurate quantification of position errors, significantly enhancing safety by preventing accidental vessel damage.

Transitioning from phantom-based experiments to clinically relevant models is essential for clinical readiness. While experiments with synthetic phantoms provide initial insights, they do not fully replicate the dynamic and biological complexities of real vasculature. The magnetic tip guidewire used in these experiments has been previously validated in animal studies. Similarly, we plan to conduct animal experiments with DATRAS once we have achieved a more stable system through precision CNC machining. These forthcoming animal experiments will be pivotal in demonstrating DATRAS’s potential for clinical transition, showcasing its applicability and effectiveness in real-world applications.

Discussion

The DATRAS robotic actuator for manipulating intervention tools presents a simple solution to overcome the limitations of complex and bulky mechanisms to create 2 DOF of the existing robots such as CorPath GRX (Corindus Vascular Robotics, MA, USA), Magellan (Hansen Medical Inc., CA, USA), R-One (Robocath Inc., Rouen, France) etc. for vascular interventions. By unifying translation and rotation mechanisms into a single and straightforward system, we substantially improved state-of-the-art, simplifying both the design and construction concepts of vascular intervention (VI) actuators. The actuator’s ability to perform inside complex environments has been demonstrated through cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantoms, underscoring its potential for real-world clinical applications. We also demonstrate the capability of DATRAS can be further enhanced by integrating an EAS. Integration with an EAS provides additional degrees of freedom by providing guidewire tip steering ability. By observing the motor torques, it is possible to distinguish changes in frictional resistance from the environment without additional sensors, which is an important feature that could be used in future development and the addition of haptics or force-feedback.

The most salient feature of the proposed DATRAS design is its mechanical simplicity compared to the existing VI robots offering 2 DOF for intervention tool manipulations. By discarding large moving parts or complex mechanisms for rotation and translation, DATRAS proposes and demonstrates a simpler solution over traditional designs. The use of only two actively controlled rollers to achieve the desired functionalities of DATRAS not only simplifies the mechanical design but also allows for a more straightforward kinematic description of the system’s motion. This simplification cascades into multiple benefits: reduced weight (320 g), improved portability, and elimination of the need for large support structures for installation. These factors collectively contribute to significantly reducing setup time, training requirements, and manpower needed for clinical deployment, potentially accelerating the adoption of robotic assistance in various vascular interventions.

There are several sources of discrepancy between the theoretical and experimental results, primarily due to limitations in the current fabrication process. DATRAS utilizes primarily 3D-printed components, selected for their flexibility and cost-efficiency in proof-of-concept stages. However, 3D printing inherently produces parts with small deformities, especially in areas that require high dimensional accuracies and tight tolerances. In particular, the coupler (Supplementary Fig. 3), which connects the motor shaft to the rollers, exhibited dimensional inaccuracies due to the tolerance limitations of 3D printing. The motor shaft features a double ‘D-cut’ shape with a diameter of 2.5 mm, a shape that is challenging to replicate precisely. The outer surface of the coupler also had defects, and its shape was not perfectly circular. This resulted in a loose fit and axis misalignment with both the motor shaft and the roller. These misalignments caused the rollers to rotate slightly off-axis, leading to non-uniform contact with the guidewire. Consequently, this introduced variation in force transmission by reducing the consistency of normal forces \(({N}_{1},{N}_{2})\) exerted on the guidewire.

Using Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) as the 3D printing material provided sufficient rigidity for proof-of-concept testing but lacked the mechanical robustness needed for prolonged operation or high precision. Elastic deformations in the 3D-printed components under operational loads exacerbated the misalignments and introduced unwanted vibration artifacts during roller rotation, which increased slippage. At elevated speeds, this off-axis rotation or vibration becomes more pronounced, leading to slippage and reducing the system’s efficiency in force transmission. Consequently, more discrepancies were observed at higher speeds. Other 3D-printed components, such as the sliding block for roller gap adjustment and motor mounts, exhibited minor warping and surface roughness. These imperfections introduced play in the sliding mechanism, reducing the consistency of grip on the guidewire, which in turn directly impacts the normal forces \(({N}_{1},{N}_{2})\) exerted on the guidewire.

While these mechanical issues have not severely impacted the performance of DATRAS, we are currently working on manufacturing all components with precision CNC machining. CNC milling will ensure tighter tolerances and enable the coupler to fit seamlessly with the motor shaft and the roller. This adjustment will eliminate axis misalignments and ensure consistent rotation, thereby improving the system’s overall stability and efficiency.

We will use aluminum for these components, which offers higher strength, rigidity, and wear resistance. Additionally, aluminum is non-magnetic, so it will not interfere with the EAS. We expect that precision CNC machining will allow us to fabricate a more stable and efficient system, effectively enhancing DATRAS’s functionality and reliability in operational settings.

A user-friendly, gamepad-operated control strategy was implemented to control the robot. To achieve precise low-level hardware control and seamless teleoperation, the Robot Operating System (ROS2) was used by implementing the ros2_control framework for sending velocity commands and the teleop_twist_joy package for configuring the gamepad. RViz and PlotJuggler were used to plot and intuitively visualize the motion of the rollers and the velocities when the user sends commands to the motors, and they are greatly beneficial for debugging purposes. Building the system with ROS2 will also help us extend this robot to a leader-follower teleoperation robot24 and integrate advanced vision systems and other sensors in the future.

At its current state, DATRAS operates on open-loop control, which is sufficient. However, a closed loop control will further reduce velocity errors in the future and help establish a fully autonomous operation along with open loop control. Implementation of closed-loop control will also require further investigations into propulsion force control. In the future, incremental steps will be taken to transition from open-loop to closed-loop control. Microforce sensors could be embedded within the roller assembly to measure and monitor excessive propulsion forces continuously. Additionally, vision-based feedback could be implemented for real-time tracking of the guidewire tip position and orientation, ensuring safe motion and precise steering to the desired target. Such closed-loop control would enhance the safety and reliability of operations, preventing damage to both the guidewire and the blood vessels. Additionally, integrating AI-based algorithms for autonomous path planning in DATRAS could substantially reduce the operator’s workload by autonomously navigating the guidewire and executing motor and control commands. However, before fully demonstrating AI’s capabilities in enhancing robotic-assisted vascular interventions, extensive validation is necessary to address safety and build operator trust.

There is also room to improve the current method of guidewire loading and unloading. Currently, users must manually insert the guidewire through the guide tube; automatic feeding of a guidewire through the guide tube by rotating the rollers is not feasible as the vertical force at the contact point between the two rollers pushes the guidewire downwards, preventing it from passing through the front guide tube, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12. Supplementary Fig. 12 also illustrates our plan to incorporate a CNC machined split guide tube to facilitate more convenient loading and unloading of the guidewire. This redesigned mechanism includes a simple sliding slot with a triangular locking notch. The guidewire can be easily placed on the bottom halves of the guide tubes, and the top parts can be slid over the bottom. This simplified approach will significantly ease the loading and unloading process compared to the current manual insertion procedure without adding complexity or bulk to the system. However, this redesigned mechanism should also undergo thorough testing and optimization to ensure its effectiveness and reliability in clinical applications.

The modularity of the design provides the flexibility to modify and scale the system with ease. Motors and controllers can be easily switched as needed, and all other parts can be readily modified and manufactured from different materials if necessary. The rollers can be replaced without the need to disassemble the entire system. Additionally, the use of the open-source ROS2 framework helps reduce costs related to software. This flexibility will aid in transitioning DATRAS from a prototype to production in the future, ensuring that it is cost-effective.

In summary, experimental results of DATRAS combined with the EAS in realistic phantoms demonstrate the potential for future teleoperation and a significant reduction in the physical footprint and mechanical complexity of vascular intervention robots. This will encourage broader adoption of robotic interventions, especially for procedures such as percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), treatment of peripheral artery disease (PAD), and neurovascular interventions like stroke thrombectomy. The ability of DATRAS to accommodate guidewires of varying diameters makes it versatile for various interventional procedures and offers a cost-efficient training tool for interventionalists to practice guidewire manipulation before performing actual procedures.

However, before DATRAS can be widely adopted clinically, it must undergo rigorous testing with animal models that realistically replicate the dynamic conditions of blood vessels. Additionally, the technical issues previously discussed must be addressed to enhance the system’s reliability and robustness for real-world applications. Future work will focus on overcoming these limitations through preclinical validation in animal models and enhancing the system’s mechanical robustness with an advanced closed-loop control. These steps are intended to bridge the gap between experimental validation and clinical deployment, ensuring that DATRAS meets the rigorous standards required for safe and effective vascular interventions.

Methods

Hardware design

The DATRAS’s main body was modeled in SolidWorks (Dassault Systems, France) and subsequently fabricated using Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) material through 3D printing on a Stratsys F170 (Stratsys Ltd., Eden Prairie, MN, USA). After fabrication, the system was assembled manually. The design focuses on balancing compactness and functionality, ensuring ease of use in clinical settings. Supplementary Fig. 4 highlights key features of the DATRAS, demonstrating its compact design and ergonomic form factor, enabling it to be handled and manipulated easily with one hand. DATRAS’s top view (Supplementary Fig. 4a) shows two rollers (UMC25-10-20, MISUMI CO., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) with a diameter of 25 mm and a length of 20 mm, forming the core mechanism. A detachable guide tube with a diameter of 5 mm is mounted to facilitate tool insertion, ensuring modularity in guidewire diameter variations. Additionally, DATRAS’s compact width of 73 mm emphasizes its overall portability.

From the front view (Supplementary Fig. 4b), the tilted motor mounts and the sliding block used to adjust the roller separation or gap can be seen. The roller spacing is adjusted using a lead screw mechanism with a 1 mm pitch, which is manually controlled. This setup allows precise changes in the roller gap to accommodate guidewires of various diameters, with good control over the gap between the rollers, which is essential for ensuring optimal friction-based propulsion without damaging the guidewire surface. The slender metal rods, each with a diameter of 1.60 mm, are visible in this view and are necessary to facilitate the sliding motion of the sliding block.

The side view (Supplementary Fig. 4c) provides insight into the overall DATRAS dimensions, 85 mm in length and 90 mm in height, while also showing insertion holes for slender metal rods and detachable supports for the guidewire. The final view (Supplementary Fig. 4d) shows the 3D-printed assembly of the completed DATRAS. The entire assembly with the rollers and the motors weigh about 320 g. The circuitry is implemented separately on a breadboard and not shown in the figures.

Motor selection

In the design of the DATRAS system, motor selection was driven by two primary requirements: the need for low-speed, high-precision actuation and the necessity to maintain a compact and lightweight form factor. Given that guidewire movements require fine low-speed control, we prioritized motors capable of delivering consistent, low-speed operation. Hence, we opted for MAXON (MAXON Group, Sachseln, Switzerland) motor drive solutions for our motors, gearheads, encoders, and controllers to ensure reliable and consistent operations while maintaining a small and compact physical footprint.

Control architecture

Two MAXON DC (MAXON DCX16S EB KL 18 V) motors integrated with a gearhead (GPX16LN 44:1) and an encoder (ENX10 EASY 1024IMP) were used to actuate the two tilted rollers. These components were selected for their high torque-to-size ratio and reliability in medical applications. The motors were controlled by MAXON ESCON 36/2 speed controllers, which offer high bandwidth current control for responsive torque regulation and precise speed control through closed-loop feedback from the encoders. The controllers can be easily used with MAXON ESCON Studio software to send velocity (RPM) commands directly. These controllers can also be easily configured via MAXON ESCON Studio, facilitating system tuning and diagnostics. The flexibility of these controllers allows for multiple operating modes, including speed, current, or position control, providing adaptability for various procedural requirements. However, user interaction with the DATRAS system is facilitated through a gamepad-based interface designed to enhance usability and provide intuitive control. The translation and rotation motion are controlled by the left joystick. One joystick axis controls the translation motion (forward and backward), and another one controls rotation (CW and CCW). The right joystick can be used to create a helical motion. A dead man’s switch has also been added for safety. Unless this button is pressed down, DATRAS will not operate, and letting go of this button will result in a halt of all operations. All these control configurations are indicated in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The control system follows a hierarchical structure, with high-level commands generated by the gamepad interface being processed by a ROS2-based control node running on a host Linux machine. To leverage the facilities provided by ros2_control packages, we used ros2_control velocity_controllers to forward the velocity commands to an Arduino Uno, which acts as an intermediate communication layer, converting the commands into appropriate signals for the MAXON ESCON controllers. We have also built a custom hardware interface for ros2_control to communicate with Arduino. This multi-layer approach allows for the flexible integration of advanced control algorithms in the future while maintaining low-level motor control precision. Supplementary Fig. 6 summarizes our description of the control and shows the overall control schematics of how the system operates.

We integrate several visualization tools to further assist in system development and operation. We created a Unified Robot Description Format (URDF) model of the rollers to enable visualization of the roller states in RViz, aiding in system monitoring and debugging. RViz provides a real-time 3D visualization of the roller states based on the encoder feedback, while PlotJuggler enables real-time plotting of roller velocities and the estimated guidewire velocity related to the roller velocities (see Supplementary Fig. 7). ROS2’s publisher-subscriber architecture facilitates the seamless integration of multiple components, allowing for easy system expansion to include additional sensors or actuators if required. This scalability is crucial for future developments in complex surgical scenarios.

Electromagnetic actuation system (EAS)

The electromagnetic actuation system was used to actively steer the tip of the guidewire inside the curved branches of the phantoms. We used an in-house developed system with 10 electromagnetic coils12. Eight of these coils are cylindrical shape, and the remaining two are circular air cores (see Supplementary Fig. 8.). The EAS can generate a maximum of 29 mT at 13 A of maximum current. The maximum uniform field region within the workspace was 25 mm×25 mm x 25 mm. We applied 20 mT for our guidewire tip steering. The system was controlled by a separate controller (Logitech G Saitek Pro Flight X56 Rhino, Logitech International S.A., Switzerland), as shown in the same figure.

Experimental setup

The experimental setup consists of DATRAS, EAS, a cardiovascular phantom, a neurovascular phantom, and a magnetic tip guidewire. Supplementary Fig. 9 shows the overall setup. The DATRAS and the EAS were controlled separately with joysticks. We used a Linux machine running Ubuntu 24.04 LTS (Noble Numbat) and ROS2 Jazzy Jalisco. Two CCD cameras (BFS-U3-32S4C-C USB 3.1, Blackfly S Color Camera; FLIR integrated Imaging Solutions, Richmond, Canada) were positioned orthogonally (one at the top and one on the side) near the EAS to capture the video streams of the guidewire manipulations. The guidewire was inserted through a micro-catheter. The micro-catheter helps with the insertion by reducing the friction at the entrance of the phantom. A Y-connector was used to prevent any kind of water leakage.

Magnetic tip guidewire

The magnetic tip guidewire was also developed in our lab in a previous work1. The main body of the magnetic tip consists of a silicone tube filled with a neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent magnet and a soft polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) based composite containing reinforced hard-magnetic NdFeB microparticles. Upon magnetic actuation, the magnetization properties allow the magnetic tip guidewire to align its body with the applied field direction, generating a magnetic torque for steering. The use of such magnetic tip guidewire adds additional degrees of freedom during intervention procedures and enhances guidewire manipulation capabilities.

Phantoms

The phantoms were made from Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and the manufacturing was outsourced (IMSystem Co., Ltd., Korea). The company was requested to make a set of coated cerebrovascular and cardiovascular phantoms simulating real vessel friction and another set of the same phantoms without any coating to simulate harsher friction environments. The coated phantoms had hydrophilic lubrication to represent true or similar endovascular behavior60. We filled the phantoms with water before all the experiments. Supplementary Movie 7 (cerebrovascular) and Supplementary Movie 8 (cardiovascular) show the manipulation differences between the coated and uncoated phantoms. For uncoated phantoms, manipulation is extremely challenging due to harsh friction, and we struggled to steer into the curved branches even with magnetic steering. These phantoms represent the shape of the real vessels, the branching, and the bifurcations. The two phantoms showing applications for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular cases are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 10. A combination of DATRAS, EAS, and magnetic tip guidewire can enable complete teleoperation in both cases.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Hwang, J. et al. An electromagnetically controllable microrobotic interventional system for targeted, real-time cardiovascular intervention. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 11, 2102529 (2022).

Soto, F., Wang, J., Ahmed, R. & Demirci, U. Medical micro/nanorobots in precision medicine. Adv. Sci. 7, 2002203 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Recent progress of micro/nanorobots for cell delivery and manipulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110625 (2022).

Choi, J., Hwang, J., Kim, J. & Choi, H. Recent progress in magnetically actuated microrobots for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001596 (2021).

Jeon, S. et al. Magnetically actuated microrobots as a platform for stem cell transplantation. Sci. Robot. 4.30, eaav4317 (2019).

Kim, E. et al. A magnetically actuated microrobot for targeted neural cell delivery and selective connection of neural networks. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb5696 (2020).

Hong, A., Petruska, A. J., Zemmar, A. & Nelson, B. J. Magnetic control of a flexible needle in neurosurgery. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 616–627 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Multifunctional biohybrid magnetite microrobots for imaging-guided therapy. Sci. Robot. 2.12, eaaq1155 (2017).

Sitti, M. & Wiersma, D. S. Pros and cons: Magnetic versus optical microrobots. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906766 (2020).

Yang, Z. & Zhang, L. Magnetic actuation systems for miniature robots: A review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000082 (2020).

Gharamaleki, N. L. et al. Electromagnetic manipulation system for semi-autonomous control of small-scale magnetic objects with sequential programming. IEEE Access 11, 35327–35335 (2023).

Gharamaleki, N. L., Kim, D., Lee, G., Kim, J. & Choi, H. Magnetic field control using an electromagnetic actuation system with combined air-core and metal-core coils. Adv. Intell. Syst. 202400462 (2024).

Hwang, J. et al. Shortwave infrared imaging of a quantum dot-based magnetic guidewire toward non-fluoroscopic peripheral vascular interventions. Small 2404251 (2024).

Dreyfus, R. et al. Dexterous helical magnetic robot for improved endovascular access. Sci. Robot. 9.87, eadh0298 (2024).

Gunduz, S., Albadawi, H. & Oklu, R. Robotic devices for minimally invasive endovascular interventions: A new dawn for interventional radiology. Adv. Intell. Syst. 3, 2000181 (2021).

Jeon, S., Nam, J., Lee, W. & Jang, G. Selective navigating and unclogging motions of an intravascular helical magnetic millirobot actuated by external biaxial rotating magnetic fields. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mech. 22, 1456–1464 (2017).

Hughes, J. W. et al. A deep learning-based electrocardiogram risk score for long term cardiovascular death and disease. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 169 (2023).

Miller, R. J. H. et al. Predicting mortality from AI cardiac volumes mass and coronary calcium on chest computed tomography. Nat. Commun. 15, 2747 (2024).

Shah, M. et al. Environmental and genetic predictors of human cardiovascular ageing. Nat. Commun. 14, 4941 (2023).

Herbert, R., Lim, H.-R., Rigo, B. & Yeo, W.-H. Fully implantable wireless batteryless vascular electronics with printed soft sensors for multiplex sensing of hemodynamics. Sci. Adv. 8.19, eabm1175 (2022).

Hooshiar, A., Najarian, S. & Dargahi, J. Haptic telerobotic cardiovascular intervention: A review of approaches, methods, and future perspectives. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 13, 32–50 (2020).

Chen, A. I., Balter, M. L., Maguire, T. J. & Yarmush, M. L. Deep learning robotic guidance for autonomous vascular access. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 104–115 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Adaptive wireless millirobotic locomotion into distal vasculature. Nat. Commun. 13, 4465 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Telerobotic Neurovascular Interventions with Magnetic Manipulation. Sci. Robot. 7.65, eabg9907 (2022).

Bergman, P., Blacker, S. J., Kottenstette, N., Saber, O. & Sokhanvar, S. Robotic-Assisted Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Handbook of Robotic and Image-Guided Surgery 341–362 (Elsevier, 2019).

Wang, S., Liu, Z., Shu, X. & Xie, L. Mechanism design and force sensing of a novel cardiovascular interventional surgery robot. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comp. Assist. Surg. 18, e2406 (2022).

Klein, L. W. et al. Occupational health hazards of interventional cardiologists in the current decade: Results of the 2014 SCAI membership survey. Catheterization Cardiovascular Interventions 86, 913–924 (2015).

Andreassi, M. G. et al. Occupational health risks in cardiac catheterization laboratory workers. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, e003273 (2016).

Guo, S. et al. A Novel Robot-Assisted Endovascular Catheterization System With Haptic Force Feedback. IEEE Trans. Robot. 35, 685–696 (2019).

Sun, Z., Guo, J., Guo, S. & Song, Y. Study on A Novel Strategy for Eliminating Tremor in Vascular Interventional Robot. in 2022 IEEE Int. Conf. on Mech. and Auto., ICMA 2022 1263–1268.

Zheng, L. & Guo, S. A magnetorheological fluid-based tremor reduction method for robot-assisted catheter operating system. Int. J. Mech. Auto. 8, 72–79 (2021).

Zhou, Y. J. et al. A real-time multifunctional framework for guidewire morphological and positional analysis in interventional X-ray fluoroscopy. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 13, 657–667 (2021).

Cha, H. J. et al. A robotic system for percutaneous coronary intervention equipped with a steerable catheter and force feedback function. in 2016 IEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2016, 1151–1156.

Zhao, Y. et al. Remote vascular interventional surgery robotics: A literature review. Quant. Imag. Med. Surg. 12, 2552–2574 (2022).

Al Nooryani, A. & Aboushokka, W. Rotate-on-retract procedural automation for robotic-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention: First clinical experience. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2018, 1–3 (2018).

Song, H. S., Yi, B. J., Won, J. Y. & Woo, J. Learning-based catheter and guidewire-driven autonomous vascular intervention robotic system for reduced repulsive force. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 9, 1549–1564 (2022).

Nguyen, C. C. et al. Development of a soft robotic catheter for vascular intervention surgery. Sens. Actuators A. Phys. 357, 114380 (2023).

Chakravartti, J. & Rao, S. V. Robotic assisted percutaneous coronary intervention: Hype or hope? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012743 (2019).

Nguyen, K. T. et al. Guide-Wired Helical Microrobot for Percutaneous Revascularization in Chronic Total Occlusion in-Vivo Validation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 2490–2498 (2021).

Abah, C., Chitale, R. & Simaan, N. Image-Guided Optimization of Robotic Catheters for Patient-Specific Endovascular Intervention. in 2021 Int. Symp. on Med. Robot., ISMR 2021, 1-8.

Chen, P., Wang, Y., Tian, D., Guo, Y. & Xu, K. The catheter and guidewire operating systems of vascular interventional surgical robots: A systematic review. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bio. 5, 180–195 (2023).

Kundrat, D. et al. An mr-safe endovascular robotic platform: Design, control, and ex-vivo evaluation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 3110–3121 (2021).

Fu, S. et al. A magnetically controlled guidewire robot system with steering and propulsion capabilities for vascular interventional surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2300267 (2023).

Razban, M., Dargahi, J. & Boulet, B. Image-based Intraluminal Contact Force Monitoring in Robotic Vascular Navigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.10762 https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.10762 (2020).

Morimoto, T. K., Hawkes, E. W. & Okamura, A. M. Design of a compact actuation and control system for flexible medical robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2, 1579–1585 (2017).

Omisore, O. M. et al. Towards characterization and adaptive compensation of backlash in a novel robotic catheter system for cardiovascular interventions. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 12, 824–838 (2018).

Cao, S. et al. A reciprocating delivery device-based endovascular intervention robot with multimanipulators collaboration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–12 (2024).

Li, N., Wang, Y., Zhao, H. & Ding, H. Robotic systems design in endovascular treatment. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot Bionics. 6, 367–383 (2024).

Mohamed, E. M. K. et al. Toward a versatile robotic platform for fluoroscopy and MRI-guided endovascular interventions: A preclinical study. in 2019 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. on Intell. Robots and Syst. (IROS), 2019, 5411-5418.

Rao, S. Endovascular robotic catheters: An emerging transformative technology in the interventional radiology suite. J. Radiol. Nurs. 35, 211–217 (2016).

Ghamraoui, A. K. & Ricotta, J. J. Current and future perspectives in robotic endovascular surgery. Curr. Surg. Rep. 6, 1–7 (2018).

Püschel, A., Schafmayer, C. & Groß, J. Robot-assisted techniques in vascular and endovascular surgery. Langenbeck’s. Arch. Surg. 407, 1789–1795 (2022).

Crinnion, W. et al. Robotics in neurointerventional surgery: A systematic review of the literature. J. NeuroInt. Surg. 14, 2021–018096 (2022).

Najafi, G., Kreiser, K., Abdelaziz, M. E. M. K. & Hamady, M. S. Current state of robotics in interventional radiology. CardioVas. Interv. Rad. 46, 549–561 (2023).

Baek, H., Cheon, B., You, J. M. & Kwon, D. S. Design and analysis of feeder mechanism for buckling prevention in robotic catheterization. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 9, 1467–1481 (2022).

Nejati-Aghdam, A. & Tavallaei, M. A. Modeling and prediction of a guidewire’s reachable workspace and deliverable forces. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 3, 227–234 (2022).

Wang, S., Liu, Z., Cao, Y., Zhang, L. & Xie, L. Improved precise guidewire delivery of a cardiovascular interventional surgery robot based on admittance control. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 19, 209–221 (2024).

Fischer, F., Gletter, C., Jeong, M. & Qiu, T. Magneto-oscillatory localization for small-scale robots. npj Robot. 2, 1 (2024).

Kummer, M. P. et al. Octomag: An electromagnetic system for 5-DOF wireless micromanipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 26, 1006–1017 (2010).

Kuhl, J., Hauschild, J. & Krause, D. Comparing friction of additively manufactured materials with animal blood vessels. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 7, 100061 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Convergence Research of Scientific Challenges through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and in part by the Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) Research and Development Program under Grant 2021M3F7A1082275 and Grant 24-KUJoint-04; and in part by the Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety under Grant RS-2023-00245686.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C. and A.M.M.B.C. conceived the idea and worked out the details. H.C. supervised the project and revised the manuscript. A.M.M.B.C. designed and built the system, planned and executed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. N.L.G. helped with building the circuits and figures for the manuscript and contributed to all the experiments. H.L. gave feedback on the system kinematics. J.K. helped with initial system development and gave important feedback on the system development. M.K., S.P., and S.Y. contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions