Abstract

This study examines the net societal impact of housing price fluctuations on mental health during a housing boom. Analyzing data from 31 Chinese provinces between 2008 and 2019, we identify a significant positive relationship between housing price returns and the rate of psychiatric outpatient visits, suggesting that rising house prices decrease mental health. The results remain robust after controlling for local firms’ stock returns. Placebo tests show that mental health impacts are primarily driven by housing price changes in the patients’ local neighborhoods. Moreover, using City-level data from a hospital in Shenzhen (where housing prices showed the sharpest rise between January 2015 and April 2019), we document a two-week lagged effect of housing price surges on mental health Deterioration, which takes slightly longer to manifest than the negative effect of stock market fluctuations. Overall, our findings suggest that housing booms deteriorate mental health and increase the societal burden on healthcare systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The extant literature on economic stressors and mental health exhibits pronounced recency bias and loss aversion focus, predominantly analyzing periods of negative wealth shocks - economic recessions, financial crises, natural disasters, and pandemics—where asset price depreciation amplifies psychological distress and negative mental health outcomes through mental accounting channels1,2,3,4. Catastrophic events like Hurricane Sandy created natural experiments demonstrating how housing displacement and income volatility activate prospect theory’s loss domain, disproportionately increasing mental illness prevalence5,6. The COVID-19 pandemic further revealed hyperbolic discounting in mental health responses to acute economic threats, with job losses and food insecurity disproportionately affecting minority groups through pre-existing inequality gradients7,8,9. However, these studies disproportionately focus on asset price declines and overlook the mental health implications of asset price growth, particularly in real estate markets. This gap is compounded by methodological limitations: prior related work heavily relies on individual-level, survey-based data, which are vulnerable to recall bias, subjective interpretation, and only capture long-term impacts10,11,12. Our research fills this literature gap by examining the effects of rapid housing price increases on psychiatric outpatient visits at both the national level (across 31 provinces) and the city level (using proprietary and high-frequency data from a Shenzhen hospital). Importantly, we provide a direct comparison between the impact of housing price fluctuations and stock market movements on mental health, highlighting the delayed and significant effects of the housing market. By analyzing proprietary hospital data, alongside rigorous heterogeneity and robustness tests, our study captures systemic, long-term stressors tied to housing booms in a high-growth housing market like China, thereby advancing the understanding of asset price fluctuations on public health.

Our focus on mental health is critical for two key reasons. First, existing studies primarily concentrate on the physical health impacts of asset price changes, leaving mental health effects largely underexplored. Second, mental disorders impose a significant burden on individuals and public healthcare systems, with limited public spending exacerbating the issue. For example, the OECD reports that despite accounting for 20–25% of the total disease burden in OECD countries, mental health receives a median of only 5% of health budgets, while low- and middle-income countries allocate less than 2%13. WHO reveals that low-income and middle-income countries allocate less than 2% of health budgets to mental health14. Therefore, as housing prices surge, the increased demand for mental health services could further strain healthcare systems, making it crucial to understand this impact and its broader implications.

The Chinese context—marked by rapid urbanization and speculative housing markets—offers critical insights for emerging economies facing similar challenges. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (hereafter “NBSC”), average residential house prices increased by 10.9% annually from 2008 to 2019. For instance, in Shenzhen, the average price of newly built commercial residential housing reached RMB 65,516/m2 in 2019, while the average annual disposable income was only RMB 62,522. This surge has created significant affordability challenges, as a decade of savings often proves insufficient to purchase even a small portion of a property. While empirical evidence on this trend is limited, anecdotes have already suggested a clear link between rising house prices and declining mental health. For example, in 2009, Sohu News reported that 70% of “mortgage slaves” were anxious. In May 2010, Sohu Health reported that a homeowner suffered from depression because his house was sold six months earlier for ¥500,000 less than he paid for it. In 2014, People’s Daily reported that a man in Zhengzhou suffered from severe depression because he could not afford a house. Four days after being rescued from a suicide attempt, he jumped to his death.

We propose that China’s housing boom affects residents’ mental health through two main channels. First, rising housing prices reduce expected utility, causing financial and welfare losses that lead to increased stress and anxiety15,16,17,18. Second, individuals often regret their property trading decisions during housing booms19,20. To capture how different groups are impacted, we divide the population into seekers (primarily renters or those aiming to buy) and holders (current homeowners).

For seekers, apparently, they face increasing financial challenges as housing prices continue to rise. They must cope with rising rental costs while also saving more to achieve homeownership, which strains their financial resources. Additionally, if seekers decide to purchase properties, they would face significantly higher mortgage loan amounts due to rising housing prices, which would ultimately reduce their future standard of living and overall utility. The housing boom exacerbates wealth inequality by disproportionately favoring property holders over seekers. As real estate appreciates faster than most other assets—with Shanghai’s market delivering over 10% annual real returns compared to near-zero returns on bank deposits21—homeownership becomes a critical, yet increasingly inaccessible, wealth-building tool. The resulting wealth gap entrenches seekers in a precarious position, reducing their long-term financial security and amplifying systemic inequality. Another major source of stress for seekers in China is the societal expectation that homeownership is essential for marriage21. In a culture where homeownership is tied to marital prospects, those unable to purchase a house face intense social and personal pressure. This issue is exacerbated by China’s one-child policy, which has led to a gender imbalance in which men significantly outnumber women. As a result, there is heightened demand for marriage-oriented homeownership, pushing parents with young sons to save more money to secure property and improve their sons’ competitiveness in the marriage market22,23.

In addition to marriage pressures, education concerns add another layer of financial strain for seekers. The “nearby enrollment” policy and the “school district system” have been implemented in China’s compulsory education system, making proximity to top schools a key factor in property values. Research shows that educational facilities significantly influence housing prices in China24,25. Homeownership located in areas with access to top schools, often referred to as “school district house” or “education real estate”, have gained popularity in the housing market. Due to the demand for quality education, families have to pay a premium for these properties, driving up the housing prices in these districts.

Overall, with rising housing prices, seekers face mounting difficulties. They contend with rising rents and struggle to save for homeownership, while higher mortgage loans lower their future living standards. These financial, societal, and educational pressures significantly increase the housing unaffordability problems in China, especially in top-tier cities like Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. As of January 2023, the housing price-to-income ratios in these cities stand at 47, 45, 40, and 37, far above the “Severely Unaffordable” threshold of 5.1 set by UN-HABITAT26.

For holders, the influence of housing price surges on mental health is multifaceted. On one hand, homeowners may experience improved mental well-being through perceived wealth gains, as rising property values relax budgetary constraints and enable increased investments in health management, leisure consumption, and stress reduction27,28,29,30. On the other hand, this wealth effect can be reshaped by market conditions and policy contexts30,31. In these cases, rising housing prices may paradoxically harm homeowners’ mental health by exacerbating financial anxiety and liquidity constraints.

This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in China, where most real estate properties serve as personal residences rather than investments. While rising housing values theoretically increase homeowners’ wealth, selling these properties easily is often impractical, making the gains largely unrealized. As a result, the unrealized paper wealth is unlikely to alleviate immediate budget constraintspressures. Moreover, holders may experience significant financial strain, as rising housing prices burden them with heavy mortgage obligations, effectively turning them into “mortgage slaves” with a substantial portion of their income dedicated to loan repayments. Besides, the linkage between homeownership and marriage market competitiveness imposes substantial psychological burdens on families with unmarried sons. Societal pressures to accumulate property assets may compel parents to purchase additional properties even when they already own one, thereby exacerbating the psychological strain caused by rising housing costs.

In addition to financial strain, holders may experience regret during periods of significant housing price fluctuations. Regret is triggered when individuals feel dissatisfied with an outcome, especially when they perceive better options are available32. During housing booms, regret can arise when holders sell their properties before prices rise, leading to feelings of missed opportunity. Similarly, hesitation in purchasing property before prices increase can induce significant mental stress. Even during a housing boom, holders may experience anxiety over the possibility of future price declines, further contributing to stress and potentially affecting their mental well-being.

Overall, while holders may experience conditional mental health benefits from perceived wealth gains, seekers endure severe financial, social, and psychological strain. This disparity raises critical questions about the net societal effect of housing price surges on mental health. According to our re-analysis on the data from the 2019 China Household Finance Survey and 2016 China Floating Population Survey, among urban households who report owning only one property, fewer than 50% hold urban-located housing, and a mere 7.54% own commercial housing (high-value, easily tradable assets with growth potential). Over half of China’s migrant population (54.99%) prioritizes purchasing homes in their destination cities, reflecting strong aspirations for urban integration. These statistics suggest that the wealth effect is only limited to a minority of holders, while systemic unaffordability of urban homeownership disproportionately harms renters, who constitute a far larger share of the population. Therefore, we hypothesize that the net societal effect of rising housing prices on mental health is negative.

H1: Ceteris paribus, the growth of house prices increases the number of psychiatric outpatient visits.

In addition to the mental stress from the housing market, a series of studies has documented the impact of stock prices on mental health in the developed countries such as the U.S. and U.K (e.g., refs. 33,34,35,36). The unique characteristics of China’s stock market necessitate the simultaneous inclusion into the housing price analyses. First, China’s stock market exhibits a decoupling from macroeconomic growth37,38. While China’s GDP grew at 6–10% annually (2008–2019), the Shanghai Composite Index exhibited extreme volatility, including crashes in 2008 and 201537. This disconnect arises from not only structural factors such as the dominance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in market indices, but also the prioritization of political objectives over profitability, and institutional weaknesses like poor corporate governance and speculative trading38.

Second, China’s stock market is characterized by heightened volatility and frequent bear markets, especially when compared to more developed markets39,40. This volatility is largely attributed to speculative trading41,42 and government intervention43 in this market. For instance, the Shanghai Composite Index reached a record high in June 2015, but then plunged, losing almost 40% of its value in a month.

Third, the Chinese stock market is dominated by retail investors (e.g., refs. 44,45). In 2022, over 99.6% of investor accounts in China are retail, with retail investors controlling more than 23% of the total stock holding value45. This level of retail participation is much higher compared to more developed markets, making the stock market fluctuations directly impact the financial wealth of millions of Chinese households. Collectively, long-term underperformance in the Chinese stock market—especially in the context of China’s rapid economic growth—can lead retail investors to feel that their investments are not yielding expected returns, creating frustration, uncertainty, and stress. Over time, this could translate into more significant mental health outcomes45.

Therefore, it is important to control for concurrent wealth effects incurred by the stock market and compare the differential impacts of housing (a more illiquid, necessity-driven, and socially embedded asset) and financial wealth (relatively more liquid) on mental health. However, unlike stock prices, which are publicly accessible and updated daily, real estate prices are updated less frequently. As a result, it may take longer for individuals to realize changes in property values and respond accordingly. Based on this, we propose our second hypothesis:

H2: The speed at which the real estate market affects the number of psychiatric outpatient visits is slower than that of the stock market.

Methods

Research design for national-level data analyses

For our National-level analysis, we collect data on psychiatric outpatient visits and other medical controls from the China Health Statistical Yearbook for 31 provinces over 13 years, from 2007 to 2019. The aggregated provincial-level data captures all psychiatric outpatient visits, regardless of specific diagnosis, to assess broad trends in mental healthcare utilization. Our key measure, PsychVisits_GR, represents the annual growth rate of psychiatric outpatient visits in province i for year t. Compared to Engelberg and Parsons (2016)34, who used new hospital admissions in California as a proxy for mental health issues, our approach has several advantages. First, hospitalizations typically occur only in cases of severe distress, so relying on such data may underestimate broader psychological impacts. Our measure, based on outpatient visits, is more likely to capture earlier or less severe psychological responses to housing price fluctuations. Second, calculating this measure for each province allows us to capture regional variations, providing a more comprehensive national assessment of mental health responses.

The residential house price data comes from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC). For residential house sales in a given area, the Bureau provides cumulative monthly data. To estimate monthly sales, we subtract the previous month’s figure (t-1) from the current month’s figure (t). These monthly prices are then averaged into annual prices. The independent variable, HRet, is calculated as the percentage change in housing prices from the previous year, adjusted for inflation to reflect real price changes.

Following Lin et al. 46, we use the following regression models.

In Model (1), our dependent variable is the annual growth rate of psychiatric outpatient visits (PsychVisits_GR), where i represents the province and t the year. The main independent variable is local housing market returns (HRet). The coefficient β1 captures the effect of housing price changes on residents’ psychological conditions. To test H2, Model (2) includes local stock market returns (LocalStockRet) to distinguish the effects of housing market fluctuations from those of the stock market. This provides a clearer understanding of how each market impacts psychiatric outpatient visits. The stock price and return data are sourced from the CSMAR database, and local firms’ headquarters data are from the WIND database.

We control for several factors that may influence the volatility of psychiatric outpatient visits in each province. Since the prior growth rate could affect the current year’s rate, we include lagPsychVisits_GR to account for autocorrelation. Additionally, as health is linked to economic conditions, we control for variables like the province’s GDP rank (GDP_Quintile) and consumer price index (CPI). We also include loan interest rate (Loan_Rate) to account for household borrowing costs and potential financial stress. Demographic factor may also matter, so we include the residential growth rate (ResidentialGrowth), urban population growth (UrbanPop_ShareGR), the proportion of females (Gender_FemPct), individuals with a college degree (Edu_CollegePct), and the percentage of single individuals over 15 (Marital_SinglePct). These factors are closely linked to healthcare utilization and patient numbers. We also account for healthcare services using HealthWorkGrowth (the annual growth rate of health workforce) and HealthExp_GDP (the proportion of total health expenditure relative to GDP). Additionally, we include the unemployment rate (UnempRate), recognizing its impact on mental health. For more details on variable definitions, refer to Supplementary Table 1. All economic data comes from the Wind and China Economic Information Center (CEIC) databases. We include year and province fixed effects to account for long-term changes and regional influences. Standard errors are clustered by province to ensure robust estimates. Observations for the first year and those missing control variables are excluded.

The final National-level sample includes 332 observations over 12 years across 31 provinces. To limit the influence of outliers, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 0.5th and 99.5th percentiles.

Research design for city-level data analyses

To gain more precision and insight into the short-term effects of housing market movements on mental health, we conduct additional tests using a unique dataset of outpatient visits for specific diagnoses from a renowned 3 A hospital in the Futian District of Shenzhen. We focus on Shenzhen due to its status as a top-tier city with significant housing price volatility, making it an ideal case study for these effects. In China, 3 A hospitals are the highest-ranked institutions (Grade 3, Class A) within a three-tier grading system. They provide advanced medical care, conduct cutting-edge research, and serve as regional hubs for complex cases, equipped with top-tier facilities and expertise to anchor the public health system. This unique data enables us to assess both the magnitude and speed of the spillover impact of housing market fluctuations on the mental health of Chinese residents in a representative urban environment. Building on Engelberg and Parsons’ (2016) framework34, we specify our model as:

LogVisitW is the natural logarithm of one plus the weekly number of outpatients diagnosed with mental disorder symptoms (i.e., anxiety, panic, sleep disorders, depression) at the Shenzhen hospital where we collected data. Diagnoses in the dataset were confirmed by licensed psychiatrists through clinical interviews and standardized screening tools. Following prior studies8,47,48,49, we narrow the focus to conditions typically more responsive to socioeconomic stressors based on WHO (1994)’s codes of International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (i.e., anxiety disorders (F40-F41), panic disorders (F41), sleep disorders (F51, G47), and depressive disorders (F32-F33)) rather than those with stronger genetic or neurobiological determinants (i.e., schizophrenia [F20-F29] and bipolar disorder [F30-F31]). HRetW represents the weekly residential housing market returns based on average weekly transaction prices of residential properties, scaled by the sample standard deviation in Shenzhen. t refers to the current week, and τ ranges from week t − 1 to week t + 4, allowing us to explore the short-term effects of housing price changes on mental health over a four-week period. Including week t − 1 ensures that future housing price fluctuations do not mistakenly appear to impact earlier psychiatric visits, improving model robustness. Year fixed effects account for annual mental health changes, while month fixed effects adjust for seasonal variations, such as increased depression toward the end of the year. We also control for the impact of China’s official holidays, as fewer outpatients seek treatment during these periods. These fixed effects isolate the specific relationship between housing market fluctuations and outpatient visits by eliminating other time-related factors.

To test H2, we control for stock market returns (StockRetW), using the weekly CSI 300 Index return from the WIND database. Daily stock market data is converted into weekly intervals and merged with the outpatient visit data to ensure a consistent time frame for analysis. Different from stock traders who monitor daily fluctuations, housing market participants typically respond to price changes over longer periods. Converting daily housing data to weekly intervals reduces noise and aligns with real estate’s slower decision-making cycles. This approach allows us to examine the effects of both housing market fluctuations and stock market performance on mental health outcomes within the same model, as reflected in Model (2).

Our sample for the City-level analysis consists of 220 weekly observations for housing market returns and 213 weekly observations for stock market returns from January 4, 2015(the first week of 2015) to April 24, 2019 (the last week of April 2019). Similarly, continuous variables are winsorized at the 0.5th and 99.5th percentiles.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital, Guangdong, China. The study was also registered with the China Clinical Trial Registration Center (Registration Number: ChiCTR2200063474).

Results

Main results for national-level data analyses

Table 1 presents summary statistics for key variables using National-level data. On average, the annual growth rate of psychiatric outpatient visits (PsychVisits_GR) is 12.5%, with a range from -30.3% to 88.6%, indicating significant variation in mental health responses to housing price fluctuations across provinces. The average house price during the sample period is 6308 RMB per square meter nationwide. The mean value of HRet is 0.117, showing an average annual housing price increase of 11.7%. Local stock market returns (LocalStockRet) averaged 26.3%, meaning investors in companies headquartered in their provinces earned an average return of 26.3%.

Figure 1 presents a parallel upward trend in both national average house prices and the number of psychiatric outpatient visits from 2007 to 2019. This preliminary evidence supports that at the provincial level, increases in housing prices are associated with a higher number of psychiatric outpatient visits

The figure shows the concurrent rise in national housing prices and psychiatric outpatient visits from 2007 to 2019. The blue line with circles represents average national housing prices measured in thousands of yuan. The red line with circles represents psychiatric outpatient visits measured in tens of millions (divided by 10 for scale).

Table 2 Column (1) presents the main regression result for estimating Model (1). The coefficient on HRet is significantly positive (β1 = 0.0760, p-value = 0.009), indicating that rising housing prices contribute to increased mental stress, reflected in higher psychiatric outpatient visits. When housing prices rise by an additional 1 percentage point, psychiatric visit growth increases by 0.076 percentage point. This result remains robust when stock market returns are included in Model (2). As shown in Table 2 Column (2), the positive association between housing market returns and psychiatric outpatient visit growth persists (β1 = 0.0660, p-value = 0.040). Consistent with prior findings, such as Engelberg and Parsons (2016), stock market returns show a significant but negative effect on mental stress (β2 = −0.0668, p-value = 0.050). This indicates that an 1% increase in local stock returns corresponds to a 0.067% decrease in psychiatric visit growth.

Among control variables, there is a negative serial correlation between PsychVisits_GR and its lagged value (lagPsychVisits_GR) (coefficient = -0.0016, p-value = 0.031), indicating a tendency for mental health visits to decline after an initial surge. PsychVisits_GR is positively correlated with HealthWorker_GR (coefficient = 0.5575, p-value = 0.026) and PsychBeds_GR (coefficient = 0.2121, p-value = 0.026), suggesting that better medical infrastructure attracts more psychiatric patients. Additionally, Gender_FemPct is positively associated with PsychVisits_GR (coefficient = 1.7681, p-value = 0.046), implying that women are more likely to experience mental health issues and seek help. Other control variables are not significant.

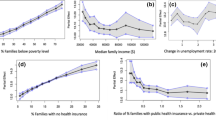

Placebo tests for national-level data

Most people tend to purchase homes near their current residence, making them particularly sensitive to local housing price fluctuations. To validate this assumption, we conducted placebo tests. In these tests, the dependent variable remains the same, but we replace the main independent variable, HRet (local housing market returns), with HRet_Other, which represents randomly assigned housing market returns from a different province.

Three different sampling methods were used to construct HRet_Other. In Method 1, we randomly selected housing market returns from any other province. In Method 2, we classified provinces into seven administrative regions (see Supplementary Table 2) and randomly selected housing returns from other regions, assuming that people generally avoid buying property outside their region. However, some residents do buy homes outside their region—for instance, Northeastern residents like purchasing property in Hainan and Hunan residents like buying property in Guangdong. To address this, we adjusted the regional groupings in Method 3 (see Supplementary Table 3). For each method, we conducted 1000 iterations. The simulated percentages of statistically significant coefficients for HRet_Other were 15% for Method 1, 10% for Method 2, and 9% for Method 3. These results suggest that housing price movements in distant regions, where residents have no plans to buy, have minimal impact on local mental health.

Heterogeneous analyses for national-level data

To investigate contextual variation in housing market effects, we classified provinces based on their historical housing price growth ever exceeded the 33.3% annual growth rate threshold during the period of 2008–2019, and re-estimated Model (1). Table 3 displays differential impacts across high-volatility versus moderate-growth regions. Provinces with extreme historical growth exhibit substantial mental health sensitivity to current price changes (β1 = 0.0938, p = 0.001), where a 1% annual housing price increase corresponds to a 0.094% rise in psychiatric visits. In contrast, regions with moderate historical growth show null effects (β1 = − 0.1324, p = 0.268). A coefficient difference test confirms significant inter-group divergence (Δβ1 = 0.2262, p = 0.0104), underscoring the critical role of regional market trajectories in moderating psychological responses.

In line with adaptive expectation theories, this heterogeneity indicates that markets with histories of volatile growth likely amplify stress through three mechanisms: (1) speculative pressures among households anticipating continued appreciation, (2) heightened wealth inequality perceptions, and (3) liquidity constraints from leveraging behaviors. Conversely, stable-growth regions may buffer price shocks through established social norms around housing as consumption (vs. investment) and lower financialization of residential assets.

Further, untabulated cross-sectional results show that residents in regions with higher housing price levels are more vulnerable to psychological stress from price fluctuations. This effect is particularly pronounced in provinces where residents show a heightened interest in housing market information (proxied by Internet searches for housing market), suggesting that increased awareness may amplify stress. Our findings also indicate that single females are more sensitive to housing price changes, highlighting the role of demographic factors like gender and marital status in how individuals respond to housing prices.

For robustness, we used an alternative dependent variable by scaling PsychVisits by the number of residents to control for population size. The main regression and cross-sectional results remained consistent.

Main results for city-level data analyses

Table 4 presents the summary statistics for the City-level sample. The standardized weekly growth rate of house prices (HRetW) was 0.016, while the standardized weekly return for the CSI 300 Index (StockRetW) was 0.031. Weekly visits in logarithm (LogVisitW) were 6.278. To put these numbers in perspective, the actual weekly transaction price for residential houses in Shenzhen averaged RMB 48,924, and the psychiatric department received an average of 562 patient visits each week during the sample period.

Figure 2 visually demonstrates the relationship between average weekly house prices and the number of outpatient visits for individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders during a period of significant housing market volatility (April 1, 2015, to December 31, 2015). The figure shows a distinct pattern, where house price movements appear to lead changes in the number of outpatient visits, suggesting a potential leading effect of housing market volatility on residents’ mental health.

The figure displays the temporal relationship between housing prices and psychiatric outpatient visits using weekly data from Shenzhen, April 1, 2015, to December 31, 2015. The blue line represents logarithmic psychiatric outpatient visits (LogVisitW) shown on the left y-axis. The red line represents logarithmic housing prices in Shenzhen (LogPriceHouseSZW) shown on the right y-axis.

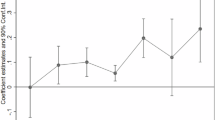

The results from estimating Model (3) are presented in Table 5. First, we test whether future house price fluctuations influence current health outcomes. As shown in Column (1), the results do not support the idea that health outcomes drive the housing market. We then examine the predictability of housing market returns in week t for psychiatric outpatient visits over the next four weeks. Columns (2) and (3) show no significant coefficient for HRetW during week t or t + 1, indicating no immediate impact of housing market returns on psychiatric visits. However, as shown in Column (4), the effect becomes significant two weeks later, with a positive coefficient for HRetW (α1 = 0.0579, p-value = 0.014), suggesting that an 8.271% growth (one SD) in house prices leads to a 5.79% increase in psychiatric outpatient visits two weeks later. However, for the full sample, we fail to find any prolonged increase in outpatient visits of mental illness after week t + 2, as shown in Columns (5) and (6).

To explore the heterogeneity of the effect, we sort the outpatients by gender and age. For age classification, we group individuals into four categories based on housing demand: children and students (0–22), youth (22–45), middle-aged (45–60), and retired individuals (60+). Using LogVisitW_Age(0–22), LogVisitW_Age(22–45), LogVisitW_Age(45–60), LogVisitW_Age(60+), LogVisitW_Male, and LogVisitW_Female as dependent variables, we re-estimate Model (3).

For the Age (0–22) group, house prices show no significant effect on mental health, likely because they do not face immediate housing needs. However, for youth (22–45), housing demand is higher, and they experience mental health pressures from the housing market more quickly. In this group, HRetW is significant and positive in week t + 1 (α1 = 0.0281, p-value = 0.064) and remains significant in week t + 2 (α1 = 0.0463, p-value = 0.038). Middle-aged and elderly individuals (45+) show a greater response to housing market returns in week t + 2, with coefficients of 0.0677 and 0.0566 for the Age (45–60) and Age (60 + ) groups, respectively. This aligns with the cultural tradition in China where older individuals, particularly parents, feel obligated to provide housing for their children, especially in marriage preparation. For the Age (60+) group, HRetW is also significant in week t + 4 (α1 = 0.0333, p-value = 0.084), suggesting that older individuals may receive housing market information more slowly.

In terms of gender, HRetW is significant and positive for both males and females in week t + 2. However, more women than men seek mental health treatment two weeks after house prices rise. This may be due to the higher incidence of psychiatric disorders among women50 or societal norms that discourage men from seeking help for mental health issues51.

City-level analyses by different types of psychological disorders

Table 6 demonstrates differential temporal impacts of housing market returns on different types of psychiatric visits. Sleep disorders show significant positive associations at t + 2 (α1 = 0.0599, p = 0.018), aligning with our baseline regression’s two-week response pattern. Anxiety displays both immediate (t + 2: α1 = 0.0529, p = 0.044) and persistent effects (t + 4: α1 = 0.0341, p = 0.030), consistent with its future-oriented symptomatology. Panic disorders exhibit the earliest response at t + 1 (α1 = 0.1116, p = 0.011), reflecting acute reactivity to perceived threats. Depression manifests rapid onset at t + 1 (α1 = 0.0452, p = 0.045), suggesting immediate emotional processing of financial stressors. These temporal variations reveal distinct psychopathological mechanisms: panic and depression demonstrate acute stress reactivity, while anxiety and sleep disorders show prolonged vulnerability. This has intervention timing implications for mental health services during economic volatility.

Complementary analysis of severe disorders reveals null effects for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia across all lags (p > 0.1), contrasting sharply with depression/anxiety disorders. This supports the clinical distinction between conditions with strong environmental sensitivity (depression/anxiety) versus those with predominant biological etiology (Sullivan et al.48; Kendler et al.49). The divergence underscores a spectrum of environmental vulnerability in psychiatric disorders, where housing market fluctuations primarily affect conditions mediated by psychosocial stress pathways.

City-level analyses by distinct phases of housing market

To examine how housing market conditions moderate mental health impacts, we conducted a temporal analysis leveraging distinct phases in Shenzhen’s housing market: a high-volatility growth period (Pre-2017 Q1) followed by market stabilization (Post-2017 Q1), as depicted in Fig. 3. Table 7 presents comparative results across these epochs.

The figure shows average quarterly logarithmic housing prices (LogPriceHouseSZ) in Shenzhen from 2015 Q1 to 2019 Q1. The blue line represents the trajectory of quarterly average housing prices during this period. Two distinct phases are visible: a high-volatility growth period (Pre-2017 Q1) followed by market stabilization (Post-2017 Q1).

During the volatile pre-2017 period, housing returns showed significant positive associations with mental health service utilization at t + 2 (α1 = 0.0523, p = 0.045), aligning with our primary findings of delayed psychological responses. Post-stabilization, these relationships attenuated to statistical non-significance across all lags (t + 2: α1 = 0.0473, p = 0.172). Between-period differences reached significance (p < 0.05) across temporal windows, confirming market volatility’s moderating role in stress responses.

This temporal heterogeneity reveals two critical insights: First, acute market uncertainty amplifies housing-related psychological strain, likely through mechanisms of financial anxiety and speculative pressure. Second, market stabilization corresponds with effect diminution, suggesting adaptive expectation formation buffers stress responses despite persistent price elevations. These findings underscore that psychological impacts of economic factors depend fundamentally on market context-rapid valuation shifts and instability prove more consequential than absolute price levels. The results advance understanding of temporal boundaries in stressor adaptation and carry implications for mental health resource allocation during economic transitions.

Controlling the stock market influence for city-level data analyses

To assess robustness, we estimate Model (4) with concurrent inclusion of HRetW and StockRetW, testing whether housing market effects persist after controlling for equity market dynamics in Table 8. We conduct this analysis for both the full sample and the subsample of local residents (LogVisitW_Local) the latter group captures visits by local Shenzhen residents (identified through healthcare insurance coverage).

Table 8 demonstrates that HRetW retains significant positive coefficients at t + 2 in both samples (full sample: α1 = 0.0619, p = 0.013; local sample: α1 = 0.0605, p = 0.017), confirming H1’s prediction of housing price effects on mental health utilization. Concurrently, StockRetW exhibits immediate negative effects in week t, e.g., in the full sample α2 = − 0.0208 (p = 0.090), where a one-SD CSI 300 decline (−3.23%) corresponds to a 2.08% visit increase—consistent with Engelberg & Parsons’ (2016) findings but demonstrating smaller magnitude than housing market impacts34. The negative effect of the stock market return is stronger for Shenzhen local residents’ mental health disorders, as in the subsample of local residents α2 = − 0.0238 (p = 0.050).

Crucially, the temporal dissociation between financial market effects—stock returns impacting mental health contemporaneously versus housing returns acting at t + 2—provides robust support for H2. This aligns with our information diffusion framework: real-time stock price visibility enables immediate psychological reactions, whereas housing market responses lag due to slower price discovery through infrequent transactions and delayed reporting. These results substantiate our prediction that housing market fluctuations predict mental health outcomes with delayed responsiveness compared to stock markets, reflecting China’s distinct socioeconomic context where real estate constitutes both wealth storage and social stability anchor.

Discussion

This study investigates the impact of house price changes on mental health during a housing boom in China, where the real estate market has surged over the past decade, making housing the most crucial asset for most families. We hypothesize that rising housing prices increase financial strain and heighten anxiety. As housing costs escalate, individuals experience stress related to housing affordability, which can trigger mental health issues. The cultural significance of homeownership in China—especially regarding education and marriage prospects—further intensifies psychological distress, leading to increased demand for psychiatric care.

Our analysis comprises National-level and City-level assessments. The National-level analysis utilizes provincial-level data to compare the influence of housing market changes against local stock price fluctuations, revealing that rising housing market returns are positively associated with increased psychiatric outpatient visits, while stock returns correlate negatively. To validate our results, we also perform placebo tests, which demonstrate that housing price movements from unrelated provinces have minimal effects on psychiatric health, reinforcing the localized impact of housing market fluctuations.

The City-level analysis, using proprietary data from a 3 A hospital in Shenzhen, reinforces these findings, showing that higher housing market returns lead to more mental disorder outpatient visits. Notably, the impact of housing price fluctuations on mental stress manifests two weeks later than that of stock market movements. The influence of rising house prices on anxiety levels is greater than that of declining stock prices. Our heterogeneity analysis indicates that stress related to housing market changes varies by age, gender, and distinct phases of housing market.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that house price growth adversely affects mental health in China, resulting in more outpatient visits. This research highlights the need for targeted interventions by policymakers to address these challenges and promote healthier communities amid rapid urbanization and economic change.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we utilize high-frequency, objective data to explore both short-term and long-term impacts on mental health. This approach addresses limitations noted in earlier research (e.g., Atalay et al.10; Baker et al.11; Wang & Liang29), which relied primarily on survey-based methodologies. By incorporating medical records (physician-rated health) alongside housing price data, we reduce biases related to survey studies and enhance the comprehensiveness of our findings. Our analysis of different time scales in housing market fluctuations brings attention to the urgent, short-term societal impacts on mental health that have often been overlooked. Our findings carry important policy implications for the development of strategies to support mental health in the context of rapidly evolving housing markets.

Second, we contribute to the literature on financial markets and health by systematically comparing the mental health effects of housing market fluctuations with those of stock market changes33,34,52,53, a comparison not commonly explored in depth. Our study reveals that housing price movements have a slower yet stronger impact on mental health compared to stock market volatility.

The third contribution of our paper lies in its demographic breakdown of the effects of housing market fluctuations on mental health. Our analysis to specific demographic groups, such as young adults (22–45) and women, exhibits heightened sensitivity to housing price increases. This adds depth to existing demographic literature, such as that by Heise et al.54. By identifying these vulnerable groups, our study underscores the need for targeted mental health interventions that consider demographic differences in experiences of housing market stress.

However, there are limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, while the study provides valuable insights into the Chinese context, particularly Shenzhen, the findings may not be easily generalizable to other countries or regions with different housing market dynamics and cultural expectations regarding homeownership. The 2015–2019 timeframe, while avoiding pandemic effects, is too brief to capture long-term housing market cycles or sustained mental health impacts. Secondly, due to ethical restrictions, our dataset lacks individual-level information on stock or housing ownership. We therefore can only conceptualize stock and housing market fluctuations as societal-level stressors. Even if only a subset of individuals holds stocks or property, aggregate shocks can propagate anxiety to non-holders through channels such as media amplification, household spillovers (e.g., stress affecting entire families). While rising housing prices could generate wealth effects for homeowners (Wang & Liang, 29), our findings emphasize the societal burden of volatility—particularly among non-owners and those indirectly exposed to market turbulence. Future studies incorporating individual ownership data could disentangle these dual mechanisms: wealth-driven psychological benefits for asset holders versus anxiety contagion in the broader population. Thirdly, due to data limitation, school district pricing cannot be disentangled from general housing prices, obscuring educational demand effects. Psychiatric outpatient data may underestimate mental health burdens by excluding mild or untreated cases. Provincial/city-level data obscure demographic and socioeconomic heterogeneity in housing price impacts. Fourthly, while our model accounts for temporal lags and economic confounders, we cannot fully rule out bidirectional relationships between mental health and housing prices. For instance, prolonged regional pessimism might dampen investment activity, indirectly affecting prices. However, such feedback loops are likely more salient over longer horizons than our short-term analysis captures. Future work could explore this dynamic using instrumental variables or multi-year longitudinal data. Lastly, our study does not directly assess individual-level psychological mechanisms (e.g., regret) that may underlie the connection between housing price fluctuations and psychological outpatient visits. Unmeasured individual psychological pathways (e.g., anxiety transmission) remain unresolved. Future research incorporating individual-level survey data or behavioral metrics would be better positioned to elucidate the mediating psychological pathways.

Data availability

National-level data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Code Ocean with the primary accession link ‘https://codeocean.com/capsule/0013395/tree’. City-level data are restricted due to institutional policies. Researchers interested in accessing these data should contact the corresponding author, who will coordinate with the relevant hospital authorities for data access approval. All requests are subject to review by the hospital’s ethics committee.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, C. C. et al. Stock or stroke? Stock market movement and stroke incidence in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 1974–1980 (2012).

Downing, J. The health effects of the foreclosure crisis and unaffordable housing: a systematic review and explanation of evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 162, 88–96 (2016).

Karanikolos, M. et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 381, 1323–1331 (2013).

Yilmazer, T., Babiarz, P. & Liu, F. The impact of diminished housing wealth on health in the United States: evidence from the Great Recession. Soc. Sci. Med. 130, 234–241 (2015).

Lowe, S. R. et al. Community unemployment and disaster-related stressors shape risk for posttraumatic stress in the longer-term aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. J. Trauma. Stress 29, 440–447 (2016).

Schneider, S. et al. Examining posttraumatic growth and mental health difficulties in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Psychol. Trauma 11, 127–136 (2019).

Ma, C., Smith, T. E. & Culhane, D. P. Generalized anxiety disorder prevalence and disparities among U.S. adults: The roles played by job loss, food insecurity, and vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Gerontol. 80, gbae181 (2025).

McKnight-Eily, L. R. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70, 162–166 (2021).

Yenerall, J. & Jensen, K. Food security, financial resources, and mental health: evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 14, 161 (2022).

Atalay, K., Edwards, R. & Liu, B. Y. J. Effects of house prices on health: new evidence from Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 192, 36–48 (2017).

Baker, E. et al. Mental health and prolonged exposure to unaffordable housing: a longitudinal analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55, 715–721 (2020).

Bound, J., Brown, C. & Mathiowetz, N. Measurement error in survey data. Handb. Econom. 5, 3705–3843 (2001).

OECD. A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health. https://doi.org/10.1787/4ed890f6-en (OECD Publishing, 2021).

World Health Organization (WHO). World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338. (2022).

Dohrenwend, B. S. Life events as stressors: a methodological inquiry. J. Health Soc. Behav. 14, 167–175 (1973).

Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M. & Prescott, C. A. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 156, 837–841 (1999).

Rabkin, J. G. & Struening, E. L. Live events, stress, and illness. Science 194, 1013–1020 (1976).

Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G. & Siegel, S. D. Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1, 607–628 (2005).

Bruine de Bruin, W. et al. Late-life depression, suicidal ideation, and attempted suicide: the role of individual differences in maximizing, regret, and negative decision outcomes. J. Behav. Decis. Mak 29, 363–371 (2016).

Yu, X. et al. Impact of rumination and regret on depression among new employees in China. Soc. Behav. Personal. 45, 1499–1509 (2017).

Glaeser, E., Huang, W., Ma, Y. & Shleifer, A. A real estate boom with Chinese characteristics. J. Econ. Perspect. 31, 93–116 (2017).

Wei, S.-J. & Zhang, X. The competitive saving motive: evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China. J. Polit. Econ. 119, 511–564 (2011).

Yang, S., Guariglia, A. & Horsewood, N. To what extent is the Chinese housing boom driven by competition in the marriage market?. J. Hous. Built Environ. 36, 47–67 (2021).

Feng, H. & Lu, M. School quality and housing prices: Empirical evidence from a natural experiment in Shanghai, China. J. Hous. Econ. 22, 291–307 (2013).

Wen, H., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, L. Do educational facilities affect housing price? An empirical study in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 42, 155–163 (2014).

Morgan, J. P. Guide to China. J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Retrieved from https://am.jpmorgan.com/content/dam/jpm-am-aem/global/en/insights/market-insights/guide-to-china.pdf. (2023).

Zhang, C. & Zhang, F. Effects of housing wealth on subjective well-being in urban China. J. Hous. Built. Environ. 34, 965–985 (2019).

Hamoudi, A. & Dowd, J. B. Physical health effects of the housing boom: quasi-experimental evidence from the health and retirement study. Am. J. Public Health 103, 1039–1045 (2013).

Wang, H. & Liang, L. How do housing prices affect residents’ health? New evidence from China. Front. Public Health 9, 816372 (2022).

Grewal, A. et al. The impact of housing prices on residents’ health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 24, 931 (2024).

Daysal, N. M. et al. Home prices, fertility, and early-life health outcomes. J. Public Econ 198, 104366 (2021).

Shepherd, L. & O’Carroll, R. E. When do next-of-kin opt-in? Anticipated regret, affective attitudes and donating deceased family member’s organs. J. Health Psychol. 19, 1508–1517 (2014).

Ratcliffe, A. & Taylor, K. Who cares about stock market booms and busts? Evidence from data on mental health. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 67, 826–845 (2015).

Engelberg, J. & Parsons, C. A. Worrying about the stock market: evidence from hospital admissions. J. Financ. 71, 1227–1250 (2016).

Lin, T. C. & Pursiainen, V. The disutility of stock market losses: evidence from domestic violence. Rev. Financ. Stud 36, 1703–1736 (2023).

Schwandt, H. Wealth shocks and health outcomes: evidence from stock market fluctuations. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 10, 349–377 (2018).

Rabener, N. Myth busting: The economy drives the stock market. CFA Institute Enterprising Investor. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2023/03/17/myth-busting-the-economy-drives-the-stock-market/. (2023).

Allen, F. et al. Dissecting the long-term performance of the Chinese stock market. J. Financ. 79, 993–1054 (2024).

Yang, Y. Comparison and analysis of Chinese and United States stock market. J. Financ. Risk Manag. 9, 44–55 (2020).

Liu, Z. & Wang, S. Understanding the Chinese stock market: international comparison and policy implications. Econ. Polit. Stud. 5, 441–455 (2017).

Hu, Y. Short-horizon market efficiency, order imbalance, and speculative trading: evidence from the Chinese stock market. Ann. Oper. Res. 281, 253–274 (2019).

Zhang, T., Li, J. & Xu, Z. Speculative trading, stock returns and asset pricing anomalies. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 61, 101165 (2024).

Hao, J., Xiong, X., He, F. & Ma, F. Price discovery in the Chinese stock index futures market. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 55, 2982–2996 (2019).

Leippold, M., Wang, Q. & Zhou, W. Machine learning in the Chinese stock market. J. Financ. Econ. 145, 64–82 (2022).

Agarwal, S. et al. Associations between stock market fluctuations and stress-related emergency room visits in China. Nat. Ment. Health 2, 909–915 (2024).

Lin, H., Ketcham, J. D., Rosenquist, J. N. & Simon, K. I. Financial distress and use of mental health care: Evidence from antidepressant prescription claims. Econ. Lett. 121, 449–453 (2013).

Catalano, R. et al. The health effects of economic decline. Annu. Rev. Public Health 32, 431–450 (2011).

Sullivan, P. F., Kendler, K. S. & Neale, M. C. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 1187–1192 (2012).

Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Sundquist, J. & Sundquist, K. The genetic and environmental etiologies of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a review of family and adoption studies. Psychol. Med. 49, 1969–1977 (2019).

Hammen, C. Risk factors for depression: an autobiographical review. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 14, 1–28 (2018).

Addis, M. E. & Mahalik, J. R. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am. Psychol. 58, 5 (2003).

Ma, W. et al. Stock volatility as a risk factor for coronary heart disease death. Eur. Heart J. 32, 1006–1011 (2011).

Qin, X. et al. Stock market exposure and anxiety in a turbulent market: evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 10, 328 (2019).

Heise, L. et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet 393, 2440–2454 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Shufang Lai acknowledges financial support by the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 72002093). Xin Liu acknowledges financial support by the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 71902033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. conducted the empirical analysis, prepared the data, and wrote the initial draft. X.L. contributed to manuscript writing, literature review, and helped secure funding. L.R. provided the core dataset and participated in results interpretation. S.L. contributed to research design, supervised the findings, and secured funding support. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. L.R. and S.L. are the corresponding authors for this paper. Y.X. and X.L. contributed equally and are therefore recognized as co-first authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Y., Liu, X., Ren, L. et al. Assessing the mental health impact of China’s housing boom through national and city-level data analysis. npj Mental Health Res 4, 24 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00135-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00135-9