Abstract

Climate adaptation behaviors can mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on food production and ecological security, yet the complex climate–environment interaction mechanisms remain unclear. We develop a Climate Adaptation–Environmental Multi-factor Feedback Framework integrating life cycle assessment, scenario modeling, and metacoupling analysis to track climate-driven dynamics of the food–water–energy–carbon (FWEC) nexus and evaluate how adaptation reshapes this nexus across input, output, and spillover systems. Using China’s Loess Plateau, we quantify 2020 agricultural footprints and simulate a business-as-usual (BAU) pathway to 2050 along with 12 adaptation scenarios. Under BAU, cultivated area is projected to expand by 22.4%, while grain yield declines by 15.8%. Climate change may shift the food production center 41–62 km northwestward and 43–115 m upward, with 47–65% yield losses in most counties. Adaptation scenarios show substantial benefits for food security and environmental sustainability, and adaptation measures also create spillover effects on major grain-exporting countries by reducing externalized environmental costs. This leads to potential global annual reductions of ~43 Mm³ in water use, ~0.08 PJ in energy consumption, and ~17 Mt of CO₂ emissions. Our findings highlight the critical role of adaptation behaviors in shaping the global FWEC nexus and advancing sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of global climate change, climate variability affects crop yields and indirectly influences agricultural production through adaptation behaviors1. Since the beginning of the 21st century, global population growth and increasing living standards have led to greater demands for stable agricultural production and food security. Concurrently, the potential for arable land development is decreasing as the difficulty of land development and associated ecological risks are increasing. As a result, a key global challenge is to ensure global food security despite a growing population. However, food production system imposes significant environmental burdens through intensive water, energy, and chemical fertilizers consumption. Such resource-intensive practices amplify transboundary crises, including water scarcity, environmental degradation and global warming. Consequently, global challenges encompassing food crises, energy shortages, water scarcity, and climate change are increasingly threatening the sustainability of regions worldwide.

In 2015, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were proposed to promote global sustainable development, including zero hunger, clean water, affordable energy, and climate action2,3,4. Climate adaptation has become imperative to reconcile increasing food demands with limited resources while balancing the nexus between human development and ecological conservation. As climate change intensifies and related adaptation behaviors become more widespread, it is vital to quantify the synergistic effects between climate adaptation behaviors and environmental impact mitigation. Such insights are essential sustainable policy-making and agricultural decision-making3,4,5,6,7,8.

In agricultural systems, the interplay of agricultural inputs, irrigation, energy consumption, and crop productivity is tightly coupled with climatic conditions, such as temperature, solar radiation, and precipitation9. Variations in the climate system force humans to adapt to pursue better input-output ratios, leading to climate adaptation behaviors such as crop substitution, farmland relocation, and technology improvement. These behaviors feed back into the climate system. Within the metacoupled system, spillover systems are driven by complex flows of information and material10, triggering compensatory responses across broader socioeconomic structures and policy decisions. Such responses manifest in grain trade, technology initiatives, and international cooperation frameworks addressing interconnected food-climate crises11. Within this integrated system, food, water, energy, and carbon emissions form a tightly coupled FWEC nexus12,13. In this nexus, water enables food and energy production, energy drives food/water producing and distributing, and these processes collectively generate carbon emissions14,15,16 consequently influencing environment.

This study focuses on the relationships between climate adaptation behaviors and FWEC nexus on Loess Plateau in China. Characterized by fragmented topography, loose soil structure, concentrated rainfall, and intensive anthropogenic disturbances, such as deforestation, overgrazing, and cultivation on steep slopes, the Loess Plateau is one of the most severely eroded regions in the world; about 60% of the area experiences erosion, with typical erosion intensities of 50–100 t ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹. In this region, core agricultural zones serve as vital food production bases, including the Hetao Plain, the Fenwei Basin, and the Yellow River Irrigation District. As one of China’s “six major granaries”, the Loess Plateau produced approximately 55.7 Mt of grain in 2023 (about 6.84% of the national total). For broader context, the Yellow River Basin yielded about 243 Mt in 2022, accounting for roughly 35.3% nationwide. The Loess Plateau also faces acute population-resources-environment tensions and complex governance challenges. Ecological conservation, human–land system coordination, and sustainable development have consistently been fundamental challenges for the high-quality development of the Loess Plateau17,18. The region’s agricultural sustainability is tightly coupled with China’s broader sustainability goals.

Metacoupling is a natural extension of coupled-systems research. Within each coupled system, three components—agents, causes, and effects—are identified; flows connect different coupled systems, which, according to the direction of flows, can be classified into sending, receiving, and spillover systems. The concept was proposed in 2008 and, by 2013, matured into a more systematic and comprehensive framework for holistic analysis and explanation of multiple coupled human–natural systems across spatial and temporal scales19,20. The metacoupling framework has been applied to land use and urbanization21, grain trade12,22, environmental conservation23,24, farmer behavior/psychology25, and tourism26, and it has become an important approach for examining flows of environmental elements within and across systems. In the field of food production under climate change, unlike earlier single-factor studies15, a growing body of work integrates multiple factors into adaptation analysis, providing a framework to assess how adaptation behaviors in food production reshape interlinkages among multiple environmental issues and, in turn, feed back to the climate system27,28,29. Despite these insights, current research still falls short in evaluating adaptation costs and overall net effects; analyses of the resource nexus and its external influences remain largely static, and the impacts on spillover systems have been widely overlooked11, leading to an incomplete understanding of the environmental consequences of food production30.

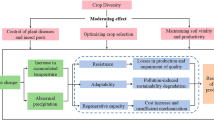

Unlike earlier studies applying static linkage frameworks31, this study uses a dynamic analytical framework (Fig. 1) to describe the evolving interactions between climate adaptation behaviors and complex environmental conditions. The study includes a life cycle assessment (LCA) of land use, water consumption, energy consumption, CO₂ missions associated with food production (including wheat, maize, rice, legumes, and tubers) across 341 counties on Loess Plateau. This assessment identifies the structure of the resource nexus. Building on prior research12,32, the metacoupling framework incorporates the roles of spillover systems and cross-regional flows in shaping the interactions between adaptation and environmental change.

The study analyzes the influence of complex natural and socioeconomic factors, including climate change, dietary transitions, irrigation technologies, farmland management strategies, and grain trade. FWEC linkages are analyzed across receiving systems (Loess Plateau), the sending systems (central government), and spillover systems (China’s major grain import partners). These analyses are guided by the metacoupling framework, which emphasizes interactions between natural and socioeconomic processes within and across system boundaries33. The metacoupling framework clarifies the interrelationships among sending, receiving, and spillover systems connected through different flows (such as grain trade and its associated water, energy, and carbon footprints)34,35. Previous studies have not fully considered the role of spillover systems36, highlighting the need to more completely describe the environmental consequences of food production37. Assessing spillover effects increases the conceptual linkage between climate adaptation and environmental issues, and reveals the hidden environmental costs embedded in food production and trade. These costs may escalate localized problems into national or global-scale crises. Exploring the potential synergistic effects within coupled system elements offers potential to mitigate negative environmental externalities while advancing global sustainability goals.

Results

Food–water–energy–carbon nexus on Loess Plateau

This study assessed the land, water, energy, and carbon footprints of food production at the county level across the Loess Plateau (Fig. 2). In 2020, the region produced 5.57 × 10⁷ tons of grain, utilizing 9081 kha of cultivated land. The associated water footprint was 3.91 × 10⁸ m³, the energy footprint was 2.01 × 10¹¹ MJ, and the carbon footprint reached 1.31 × 10⁷ tons of CO₂. Spatially, the southern and northern sub-regions along the Yellow River Basin accounted for the largest shares of water, energy, and carbon footprints that year, and they also exhibited the highest FWEC intensities. This pattern reflects not only their extensive irrigated cropland and river-valley plains but also constraints that raise per-unit footprints: drier climates in the north increase irrigation dependence, pumping heads, and conveyance losses (elevating energy use and CO₂); hilly/loess-gully terrain and fragmented plots in the south limit mechanization and water-use efficiency; loess soils with low water-holding capacity and high erodibility raise irrigation demand; and heterogeneity in high-standard-farmland projects and water-allocation policies shapes input intensity37,38.

Among the FWEC components, water is pivotal in agricultural production. Statistical analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the water footprint and both the carbon and energy footprints (p < 0.01). The green water ratio, defined as the proportion of natural precipitation in the water used in food production, serves as an indicator of irrigation dependency. It was strongly negatively correlated with all three footprint metrics. Counties with high water, energy, and carbon footprints are also likely to face water resource sustainability challenges39,40. The results also showed that counties with higher grain output are primarily distributed in a “J”-shaped pattern along the major river systems. Notably, while the main grain-producing areas experienced increases in yield in 2020 compared with previous years, there were no significant increases in land use, water footprint, energy footprint, or carbon footprint. This decoupling may result from land management and ecological restoration projects implemented in recent years across the Loess Plateau, including gully control and land reclamation, reforestation, and grassland restoration41,42. These interventions have improved environmental and agricultural conditions, contributing positively to regional water-energy-grain dynamics by optimizing agricultural input structures and increasing land productivity. Environmental impacts across the Loess Plateau show significant spatial heterogeneity (Fig. 2). Water resource sustainability tends to decline from south to north, with exceptions in some western counties. Concurrently, water, energy, and carbon footprints vary significantly across counties, reflecting heterogeneity in agricultural productivity, industrial development, farming practices, and water resource utilization.

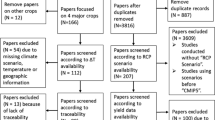

Impacts of climate change on food production

The AquaCrop model was applied in combination with LCA and a Random Forest (RF) modeling approach to project how grain yields and cultivated area change in response to future climate change across the Loess Plateau. The assessment utilized a consolidated 21-year dataset (2000–2020) of county-level food production and climatic variables to project grain yield and cultivated area in 2050 under three climate scenarios defined by the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs): SSP126, SSP245, and SSP585 (a fossil-fueled development pathway with high emissions)32.

The results indicate that climate change may adversely impact grain cultivation in the region. Among the 341 counties analyzed, 222 (65%) counties are projected to experience yield reduction by 2050. Under SSP126, SSP245, and SSP585 scenarios, cultivated areas are expected to expand by 24.5%, 22.4% and 31%, respectively, while grain yields are projected to decline by 10%, 15.8%, and 11.2%, respectively, between 2020 and 2050 (Fig. 3). Subsequently, projected changes in cultivated area and yields were integrated to compute the weighted spatial shift in the center of food production. Projections indicate a northwestward migrate of the production center by 41–62 km under climate change (Fig. 4c), with a concurrent vertical upward displacement of 43–115 meters (Fig. 4d). County-level vulnerability to climate impacts exhibits significant heterogeneity, driven by both historical trends and local agro-environmental conditions.

a Predicted percentage change in production, acreage and yield on Loess Plateau until 2050 under SSP245. b Spatial variation in yields projected through 2050 under SSP245. c Movement of planting weighted centroid on Loess Plateau until 2050 under SSP126, SSP245 and SSP585. d Vertical movement of the planting centroid until 2050 under SSP126, SSP245 and SSP585.

Under the SSP245 scenario, production efficiency of most counties is projected to decline by 47% to 65% between 2020 and 2050 (Fig. 4b). Geographically, this change shows an east-west decreasing gradient; more eastern counties are projected to experience yield increases, whereas declines are projected to be more prevalent in the west. In the east, modest warming, slightly wetter or more reliable growing-season water supply, and higher irrigation reliability—together with better soils and flatter terrain—reduce water stress and allow farmers to benefit from longer frost-free periods and CO₂-fertilization effects; combined with wider coverage of high-standard farmland and efficient irrigation, these factors help sustain or raise productivity. By contrast, many western counties face intensifying aridity and heat stress that raise crop evapotranspiration and shorten effective growth periods; thinner loess, severe erosion, and lower/ more variable precipitation increase irrigation requirements, pumping heads, and conveyance losses, tightening water–energy constraints and making yield declines more likely43.

Assessment of climate adaptation strategies

Given SSP245 is currently the most probable scenario, we used the actual situation in 2020 as the baseline and defined the projection for 2050 under the SSP245 scenario as the S1 scenario(The results of the SSP126 and SSP585 scenarios are presented in the supplementary Fig. 1.). Twelve adaptation scenarios (S2–S13) were subsequently developed by integrating different climate adaptation strategies (Table 1). By simulating food production and resource consumption under these scenarios, we evaluate and identify optimal climate adaptation measures(supplementary Table 1). Projections reveal significant variations in environmental indicators and food prodution (Fig. 5). The three scenarios with the lowest water footprint (ascending order) are S11 (dietary shift C: reducing per capita grain intake to 65 kg/year), S13 (upgrading to drip irrigation, combined with land consolidation and dietary shift C), and S10 (dietary shift B: per capita grain intake reduced to 80.5 kg/year). The three scenarios with the highest water footprint (descending) are S1 (climate change), S2 (climate change with reduced irrigation in normal-flow years), and S3 (climate change with rainfed irrigation in high-flow years). Notably, the scenarios with the lowest water footprint (S10, S11, and S13) simultaneously achieve the lowest energy and carbon footprints, demonstrating synergistic sustainability benefits.

Scenarios S10 and S11 exhibit the lowest water and food sustainability, primarily due to their substantially reduced crop yields—these include two of the three lowest-yielding scenarios fall into this group. The highest yields (and highest food sustainability) are seen under S4 (upgraded to drip irrigation), S5 (upgraded to sprinkler irrigation), and S13 (drip irrigation combined with land consolidation and dietary shift C)(supplementary Table 2). Notably, scenarios S4 and S5 are among those having higher energy and carbon footprints, indicating that crop yield increases are often driven by greater water and energy consumption, which may not be sustainable. Overall, the results show that among the 13 scenarios, 8 scenarios (S1–S6 and S8–S9) can not ensure water sustainability, 6 scenarios (S2–3, S6—reduced irrigation with conservation tillage, and S9–11) can not ensure food sustainability. Critically, only three scenarios simultaneously achieve both water and food sustainability. All of the remaining scenarios fail to meet both criteria (Fig. 5).

By type, we considered three dimensions and defined four classes of scenarios: production mode (S2–S8: reduced irrigation S2–S3; irrigation upgrades S4–S5; conservation tillage S6–S8), consumption-side adjustments (S9–S11), land consolidation (S12), and an integrated option (S13). This grouping helps reveal the trade-offs in Fig. 5: reduced irrigation (S2–S3) offers only limited relief to the water footprint and depresses yields; irrigation upgrades (S4–S5) deliver the highest yields and food sustainability but come with higher energy and carbon footprints; conservation tillage (S6–S8) strikes a balanced outcome—lower water/energy/carbon footprints with only moderate changes in yield; consumption-side adjustments (S9–S11) produce the largest footprint reductions, yet S10–S11 struggle to ensure food sustainability because output falls substantially; land consolidation (S12) improves water sustainability while maintaining moderate yields and achieving lower footprints than S4–S5; and the integrated scenario (S13) combines efficiency upgrades, structural measures, and demand-side adjustments to achieve both low footprints and high yields, making it one of the few scenarios that meets water and food sustainability simultaneously.

We conducted a localized sensitivity analysis around the SSP245 baseline using a first-order delta (Δ) approach, perturbing temperature and precipitation to reflect Loess Plateau conditions: L1 (mild hot–dry: +0.5 °C, −5%), L2 (moderate hot–dry: +1.0 °C, −10%), and L3 (severe hot–dry: +1.5 °C, −15%) with a storm-dominated rainfall regime (βp = 0.70; otherwise βp = 0.80). Each scenario (S1–S13) is assigned scenario-specific sensitivities to temperature and precipitation, denoted sT(temperature–ET sensitivity) and sP(precipitation–effective-rain transmission), and the yield response employs the scenario’s blue-water share (λ). For each scenario, we computed percentage changes in the FWEC footprints under L1–L3, summarized the overall sensitivity by the median across the three perturbations, and reported dispersion using the IQR.

The results reveal a stable ranking in the water-footprint response to hot–dry stress: S13 is least sensitive, followed by S4–S5, with S6–S8 and S12 in the middle, and S1–S3 most sensitive. This pattern reflects systematic differences among strategies in water-saving efficiency, rainfall dependence, and soil-moisture conservation: the integrated package (S13) layers irrigation upgrades, conservation tillage, and land consolidation, improving effective rainfall use while reducing rigid dependence on blue water; irrigation upgrades alone (S4–S5) markedly dampen water sensitivity but remain exposed to higher evaporative demand; conservation tillage (S6–S8) suppresses evapotranspiration via cover and enhanced infiltration, yielding intermediate effects; land consolidation (S12) increases storage and rooting depth and thus buffers shocks to a moderate degree; baseline and reduced-irrigation cases (S1–S3) depend more on rainfall and therefore react more strongly. Energy and carbon footprints scale almost proportionally with water (≈ 0.6× and 0.5× of the water change, respectively), indicating that pumping and power use dominate their variability. For yield, all strategies show declines under hot–dry conditions but to differing extents: diet-shift scenarios (S9–S11), with lower blue-water shares in crop/irrigation mixes, exhibit slightly smaller median losses (about −4.4%, −4.5%, and −4.6%, respectively) than the baseline S1 ( − 4.8%); the integrated package S13 offers the best trade-off between low footprints and limited yield loss. Scenario-wise minima, quartiles, and maxima are provided in the boxplots in the Appendix(supplementary Fig. 2).

Environmental costs of climate adaptation behaviors

While Climate adaptation behaviors may bring significant long-term economic and environmental benefits for the Loess Plateau, they may generate simultaneously impose near-term environmental pressures. To evaluate the environmental impacts of climate adaptation behaviors, a comprehensive footprint assessment of land consolidation projects one of the more proactive climate adaptation strategies in the region was conducted. The Master Plan for Comprehensive Management of the Loess Plateau (2010-2030) was used to define the project scale. Land consolidation projects were classified into four major components: sediment dam construction, slope-to-terrace conversion, water cellar installation, and dryland water-saving infrastructure. Following the ISO 14040 standard, the assessment cycle covered the material production phase, construction phase, and operation and maintenance phase (Fig. 6).

Across four land-consolidation types—sediment dam construction, slope-to-terrace conversion, water cellar installation, and dryland water-saving infrastructure—the contributions to total footprints are, respectively: water 52/28/6/14% (≈388/209/45/104 Mm³), carbon 48/22/12/18% (≈3.27/1.50/0.82/1.23 Mt), and energy 45/33/7/15% (≈65.7/48.2/10.2/21.9 PJ). Quantitative evaluation reveals that land consolidation projects on Loess Plateau generate a total projected water footprint of approximately 746 Mm³, with the construction phase accounting for over 80% of that total, indicating there is substantial pressure on regional water resource allocation during implementation. The total carbon footprint is approximately 6.81 Mt, with most emissions originating from material manufacturing and land reshaping. The total energy footprint is around 146 PJ, and is primarily concentrated in large-scale mechanized construction and transportation activities. In conclusion, material preparation constitutes a significant share of the water, energy, and carbon footprints transferring environmental burdens to supply regions nationwide(supplementary Table 3). The construction phase remains the most resource-intensive and carbon-emitting stage. While China’s central government provides considerable fiscal backing for these construction initiatives, land consolidation projects impose near-term environmental pressures for the Loess Plateau despite their long-term climate adaptation benefits44.

Spatial spillover effects of climate adaptation behaviors

Optimizing climate adaptation on Loess Plateau to achieve greater grain self-sufficiency may trigger a chain of spatial spillover effects in the context of international grain trade. As a major grain producer and consumer, China imported 142.62 million tons of grain in 2020, representing a 27.97% increase (31.18 million tons) compared to the previous year. Cereals accounted for 20% of these imports, equivalent to ~4.8% of China’s domestic food production. Using wheat as an example, China has historically sourced imports primarily from Australia (36.5%), the United States (25.8%), Canada (25.1%), Kazakhstan (6.6%), and France (4.4%)45. Imports require additional transportation energy; However, the emission intensity of domestic production generally exceeds that of major exporting countries. Therefore, in many cases, international grain trade can lead to a net reduction in global carbon emissions.

Given concerns about grain self-sufficiency and food security, the Chinese government has consistently sought to reduce import dependency. While imports bridge the gap from rising demand, expanding domestic food production requires substantial resource investments. International trade inherently transfers virtual land, water, and energy resources46, whose footprints depend on regional endowments, production inputs, and transport distances. Optimizing adaptation strategies in food production on Loess Plateau could simultaneously reduce China’s foreign imports reliance and mitigate global resource depletion. Specifically, these strategies are projected to reduce global water consumption by 43.1 Mm³, energy use by 0.08 PJ, and carbon emissions by 17 Mt CO₂ (Fig. 7). Trade flow analysis further confirms these localized adaptation strategies generate substantial spillover benefits at global scale.

a Major exporting countries; b Main driving factors of resource consumption of food production on Loess Plateau and exporting countries; c Differences of total water footprint, energy footprint and carbon footprint between international food trade versus self-sufficiency on Loess Plateau under different scenarios.

Discussion

This study focused on Loess Plateau, a typical region facing multiple pressures from climate change, food security, and ecological stress. A dynamic FWEC metacoupling analysis framework was applied to systematically investigate the integrated effects of climate adaptation behaviors on regional food security and environmental sustainability. Unlike previous studies using static frameworks11,47, our dynamic FWEC metacoupling approach maps agents–causes–effects within coupled systems and traces flows across sending, receiving, and spillover systems, thereby clarifying how adaptation reshapes both on-farm footprints and trade-mediated spillovers over time. It also described their cross-regional transmission mechanisms. The study clarified that, although climate adaptation measures such as land consolidation projects increased short-term water consumption, energy use, and carbon emissions, they significantly improved agricultural productivity and mitigated long-term climate-induced agricultural risks. As such, they contributed to reduced resource utilization and environmental pressures at regional and global scales. Implementing measures such as land consolidation requires prudent trade-offs between short-term costs and long-term benefits, especially in terms of material selection and construction technology optimization.

Scenario simulations further revealed that advanced irrigation technologies (such as drip and sprinkler irrigation) and conservation tillage practices have significant synergistic benefits in reducing the water, energy, and carbon footprints associated with agricultural production. Study results highlight that dietary adjustments and reduced food waste can substantially reduce resource consumption from the demand side of food production. At a policy level, it is essential to consider the combined influence of both production and consumption systems. Relying solely on supply-side adjustments is insufficient to balance the development of food security and environmental sustainability9,48.

At both theoretical and empirical levels, this study introduced the metacoupling system framework to analyze the international spatial spillover effects of climate adaptation behaviors on Loess Plateau. It also clarified how implementing climate adaptation strategies can indirectly influence resource consumption and environmental burdens in other regions through the global grain trade network49,50. Specifically, adaptation behaviors on Loess Plateau improved regional grain self-sufficiency and reduced dependence on international grain markets. This significantly reduced global water, energy, and carbon emissions. In grain-exporting countries, these measures are estimated to reduce annual water use by approximately 43.1 Mm³, energy consumption by 0.08 PJ, and carbon emissions by 17 Mt CO₂. These findings highlight the critical bridging role of international grain trade in coordinating global food security and climate adaptation. This further underscores the need to strengthen international cooperation within climate adaptation strategies51,52,53.

Based on the above findings, this study offers the following recommendations for management practices and policy-making. When promoting land-consolidation projects, irrigation infrastructure, and agricultural technology upgrades, China’s central and local governments should explicitly weigh short-term environmental pressures against long-term benefits54,55. For the Loess Plateau, this balance is especially relevant because construction activities account for most of the near-term water footprint, and sediment-retention (check) dam construction contributes the largest share of project-related water and carbon burdens. Accordingly, implementation guidance should emphasize construction-phase water management (closed-loop batching water, non-potable water for curing and dust suppression) and low-clinker blended cements/geosynthetics to curb immediate FWEC loads, while farm-stage measures—notably water-saving irrigation (drip/micro-irrigation) and conservation tillage—help lock in longer-term gains. Policy instruments should jointly target production and consumption: expand water-saving irrigation and soil-conservation practices; on the consumption side, introduce front-of-pack eco/footprint labels, public-procurement standards for lower-FWEC staples (e.g., in schools and hospitals), food-waste reduction measures (standardized date labels, near-expiry discounting, plate-waste monitoring), and dietary guidance that nudges higher shares of coarse grains and legumes. Internationally, trade policy should incorporate climate-adaptation considerations into global grain-market governance56—for example, adaptive tariff-rate and reserve mechanisms during climate shocks, MRV clauses for embedded footprints, and facilitation rules that ease the cross-border diffusion of water-saving technologies—thereby advancing global environmental benefits and food security49,57.

This study also has some limitations to be addressed in future studies. Data limitations prevented an in-depth analysis of more complex factors involved in international grain trade, such as trade policies, national agricultural policies, and agricultural endowments. In addition, assessments of environmental burdens during land consolidation project implementation could be further refined, given the complexity of the engineering processes and the difficulty of data acquisition. The scenario simulations in this study incorporate multiple influencing factors, but do not fully capture the complex interactions between natural environmental and socioeconomic conditions on Loess Plateau agricultural production systems. This study focuses on government-level adaptation behaviors and does not deeply analyze dynamic responses at the individual and household levels. It also does not consider the impacts of social factors on adaptation behaviors, such as poverty, equity, and social welfare.

Future research should broaden data sources by combining policy-text analytics of tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff measures with customs/price microdata to build a panel of international grain-trade and domestic agricultural policies, then embed these variables in a structural-gravity or metacoupling-consistent flow module to quantify their effects on adaptation strategies. Environmental-burden estimates for land-consolidation projects can be refined with process-based LCA using bills of quantities, contractor logs, and on-site metering of batching/curing/dust-control water, fuel, and electricity during construction. Socioeconomic and governance heterogeneity should be incorporated via household surveys and choice experiments to estimate adaptation-adoption functions, linked to organizational modes (enterprise operations, individual household farming, village collective management) and to multi-level interactions among central government, local authorities, and farming households (e.g., hierarchical models; difference-in-differences for staggered rollouts)58,59. From a social–ecological perspective, future work should evaluate distributional outcomes—equity, poverty, and welfare—under alternative adaptation portfolios and trade regimes, thereby providing decision-relevant evidence for comprehensive and sustainable development pathways60,61,62,63.

In summary, this study offers both a novel theoretical perspective and robust empirical evidence about the short-term costs and long-term benefits of climate adaptation measures, local impacts, and international spillover effects. It also provides clear policy directions and implementation pathways for governing food security and environmental sustainability at regional and international scales. These findings advance theoretical understanding in climate adaptation and food security research and provide a solid and specific foundation for future management practices and policy-making.

Methods

Multidimensional environmental impact assessment and prediction system for food production

To comprehensively assess the resource and environmental impacts of large-scale land consolidation projects on Loess Plateau, the LCA method was integrated with a footprint analysis. This approach retains the advantage of LCA in tracing material and energy flows across the full life cycle, including raw material acquisition, processing, transportation, use, and end-of-life disposal. However, it also incorporates the focused analytical strengths of indicators such as the water, carbon, and energy footprints. These methods were used to quantitatively estimate these footprints for Loess Plateau land consolidation projects. In addition, the land use and water, energy, and carbon footprints were calculated for county-level food production on Loess Plateau from 2010 to 2020. For the water footprint assessment, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) -recommended tripartite classification was applied: green water refers to rainwater runoff; blue water refers to surface and groundwater withdrawals; and grey water is the amount of water needed to dilute pollutants. The energy footprint focused on fossil energy consumption along the entire production chain; the carbon footprint emphasized CO₂-equivalent emissions64,65.

Data on natural geography, food production, and environmental impacts were combined with the AquaCrop model, RF model, and the LCA method to figure multidimensional environmental impact for food production (Fig. 8). The AquaCrop model was used to simulate grain yields under different scenarios; the LCA and RF models were used to predict land use and environmental impacts. Specifically, input variables included grain yield, climate conditions, and planting conditions; output variables included land use and water, carbon, and energy footprints. Given the unique characteristics of food production, the production cycle was decomposed into five key operational units: tillage and land preparation, seeding and seedling cultivation, irrigation management, fertilization, and harvesting and storage/transportation66.

To evaluate the accuracy of model predictions for food production data, the data samples from different years were divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. A Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and symmetric concordance index (λ) were used to measure the correlation and consistency between predicted and observed values. Mean error (ME), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE) were used to quantify the deviation between predictions and actual values. To further verify RF model performance, other machine learning methods were applied for a comparative analysis, including Bagging, Boosting, and a Support Vector Machine (SVM). The LCA method enabled a detailed analysis of each life cycle stage, while the RF model enabled the simulation and prediction of environmental impacts under different scenarios. This combination also facilitated an analysis of how different policy options, technological applications, or material usage impact environmental outcomes. Compared to the traditional linear analysis in LCA, the RF model helped identify the relative contribution of different variables to environmental impacts. Incorporating LCA outputs at different stages also improved the interpretability of the RF “black box” model.

Water footprint

Green water, blue water, and grey water use were evaluated throughout the food production process. The green and blue water footprints were calculated using the Penman–Monteith equation, as recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (40). This equation is based on daily meteorological data at the weather station level, combined with daily crop evapotranspiration coefficients for different types of grain crops during their respective growing seasons, as shown below:

Where WFgreen(m³) represents the amount of rainwater and soil moisture required for crop growth, and WFblue(m³) denotes the irrigation water demand of the crop.A (ha) refers to the cultivated area of the crop. ETgreen (mm·yr⁻¹) and ETblue (mm·yr⁻¹) represent the evapotranspiration from precipitation and from irrigation, respectively, during the crop growing period. ETc (mm·yr⁻¹) denotes the total crop evapotranspiration, and Pe (mm·yr⁻¹) is the effective precipitation available to crop.

Where P (mm/day) represents the total precipitation, and ET₀ (mm/day) is the reference evapotranspiration calculated using the Penman–Monteith equation. Δ (kPa·°C⁻¹) is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve, and Rn (MJ·m⁻²/day) is the net radiation at the crop surface, and G (MJ·m⁻²/day) is the soil heat flux, and γ (kPa·°C⁻¹) is the psychrometric constant; Tmean (°C) is the mean daily air temperature at 2 meters height, and u₂ (m·s⁻¹) is the wind speed at 2 meters height. es (kPa) is the saturation vapor pressure, and eq (kPa) is the actual vapor pressure. Kc is the crop coefficient, which reflects the difference in evapotranspiration between the crop and a reference plant surface. The Kc are calculated using linear interpolation based on the guidelines provided in FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 5667.

The grey water footprint refers to the volume of water required to assimilate pollutants generated by fertilization, in order to maintain ambient water quality within established environmental standards. The calculation is as follows:

Where α (%) represents the leaching rate of the pollutant, and F (kg) is the amount of fertilizer applied, and cmax (kg·m⁻³) denotes the maximum allowable concentration of the pollutant in the receiving water body, and cnat (kg·m⁻³) refers to the natural background concentration of the pollutant in the receiving water body. In this study, the grey water footprint was calculated based on a 10% leaching rate of nitrogen fertilizer68. The maximum allowable nitrate-nitrogen (NO₃-N) concentration in surface and groundwater was set at 10 mg/L, i.e., cmax = 0.01 kg·m⁻³, and the natural background concentration was assumed to be zero (cnat = 0).

Carbon and energy footprint

This study applies a life-cycle assessment to the crop production stage. Included processes are the upstream manufacturing of farm inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, seeds, plastic/mulch, irrigation pipes and pumps), on-farm irrigation (electricity/diesel), and field operations (machinery fuel and electricity). Post-farm stages—transport, storage, processing, retail, and household consumption—are excluded. County-level data on fertilizers, pesticides, seeds, machinery, and irrigated area are taken from provincial/municipal statistical yearbooks; irrigation events and volumes for each scenario are obtained from AquaCrop simulations. Energy use and CO₂ emissions for irrigation and machinery are computed by converting activity data with method-specific energy-intensity coefficients and emission factors corresponding to the irrigation method and field operation.

Agricultural production results in considerable carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions. The carbon footprint (CF) of irrigated agriculture was calculated using Eq. (9):

Where CFF、 CFI、CFM、CFH、CFS and CFP represent the CO₂ emissions from fertilizer application, irrigation, mechanical operations, labor inputs, seed inputs, and pesticide and herbicide use, respectively.

The total energy consumption (E) throughout the entire crop production chain was calculated using Eq. (10):

Where EW、EM、EL、EF、EP and EI denote the energy inputs for seed, machinery use, labor, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation, respectively.

Metacoupled systems

The theoretical framework of the metacoupling system69 indicates that systems are interconnected through the interactive transfers of elements, such as grain trade and capital and policy influence. This enabled the construction of a multi-level, multi-dimensional analytical model of cross-regional human-nature system interactions. The Loess Plateau, the Central People’s Government of China, other regions within China, and China’s major grain-importing countries are all coupled human-natural systems. Within each system there are interactions between humans and nature. For example, on Loess Plateau, there is grain production, energy and water consumption, and CO₂ emissions; in the central government, there are grain trade policies; and in the spillover systems, which are countries that export grain to China, there are water losses, land use, energy consumption, and CO₂ emissions. These are all interconnected through the flow of many elements.

This study deconstructed the system network within the research scope into three organically linked components: the sending system of the Central People’s Government, which provides policies and funding; the receiving system of the Loess Plateau, which carries out large-scale land consolidation and which relies on financial and policy support; and the spillover system involving countries exporting to China. While these countries do not receive direct financial or policy assistance from the Chinese central government, they benefit indirectly from the grain trade. This reduces the water, energy, and carbon footprints associated with their own food production; cross-border grain trade forms a unique “environmental burden transfer channel” within the system network. Major grain-exporting countries saw reductions in agricultural production activities due to import substitution. This objectively lowered their agricultural water intensity, fertilizer application density, and carbon emission intensity. This reflects the spatial restructuring of the supply-demand relationship for ecosystem services under globalization70.

Multi-scenario simulation

Different scenarios were set (Table 1) to simulate the effects of different factors on water, energy, and carbon footprints. The evaluation of food production and the associated environmental footprints under different scenarios on Loess Plateau considered factors such as climate change, irrigation techniques and methods, dietary structure adjustments, and water resource transfers in land consolidation projects71,72.

First, actual conditions in 2020 were set as the baseline before climate change, denoted as S0. For the climate change variable, different scenarios considered different levels of climate variability73. In addition to natural factors such as precipitation and temperature, socioeconomic factors were also considered, combining SSPs scenarios with The Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) scenarios. The SSP245, denoted as S1, was set as the forecast for future climate change, which also served as the baseline for subsequent simulations. The reference crop evapotranspiration ET₀ was calculated using the Penman–Monteith equation, using CROPWAT 8.0 software. Based on previous studies74, climate parameters were projected based on trends from 2000 to 2020. The AquaCrop model was used to predict crop yields. The model inputs included crop type, weather, soil type, groundwater, field management, and initial conditions.

To ground our scenarios in the current conditions of the Loess Plateau, we draw on evidence that most cultivated land is rainfed with high interannual precipitation variability, while the main grain belts are concentrated in irrigated districts along the Yellow River (e.g., Hetao, Fenwei Basin, Yellow River Irrigation District); at the same time, water-allocation and farmland-improvement programs on the Loess Plateau emphasize water-saving irrigation and conservation tillage to reconcile production with ecological constraints75,76,77,78,79. Accordingly, three management levers were considered for agricultural production modes: reduced irrigation volumes, application of conservation tillage techniques, and upgrading of irrigation systems. Much of the Loess Plateau is rainfed; however, the main grain-producing areas lie within irrigated zones near the Yellow River, so irrigation was included among the simulation factors. To reflect realistic field practice, we used AquaCrop to estimate yields under different irrigation/precipitation regimes. Specifically, scenarios limited irrigation to two events in normal years and to zero events in high-water years (rainfed only). From the consumption side, we also examined output requirements under dietary shifts and back-calculated the associated production needs. For each scenario, we computed the corresponding water, energy, and carbon footprints based on the assumed production technologies, and we evaluated production sustainability under dietary adjustments80,81,82.

Land consolidation variables were determined using the Master Plan for Comprehensive Management of the Loess Plateau. In the region, constructing check dams, slope-to-terrace conversion, water cellars, and dryland water-saving infrastructure all reduce water and soil erosion, improve the ecological environment and production conditions, and promote rational development and water and soil resource use. The Plan proposed the construction of 56,161 check dams, including 10,223 key dams and 45,938 small and medium-sized dams. In mountainous, highland, and hilly areas with serious erosion problems, a total of 39.12 million mu of land was proposed for terrace conversion. The Plan also included 3.85 million water cellars (1.23 million in the near term and 2.62 million in the long term) and 23.22 million mu of dryland water-saving infrastructure (7.38 million mu in the near term and 15.84 million mu in the long term).

Based on this, in AquaCrop we operationalize “land-consolidation projects” as improvements to micro-topography and infiltration–storage conditions that moderately enhance topsoil water-storage capacity and irrigation water-use efficiency. Concretely: we slightly increase Total available soil moisture (FC–WP, mm/m) by about +10–30 mm/m to represent improved field water-holding; raise the Maximum rain infiltration rate (mm/day) by +10–25% relative to baseline to reflect enhanced infiltration from land leveling/small basins/detention; increase the Maximum rooting depth (cm) by +10–20 cm to capture deeper exploitable soil after siltation/reshaping; and, in the implementation year, set Initial soil moisture depletion (%TAM) to +10 percentage points above baseline to represent construction disturbance and suboptimal field preparation, reverting this parameter to its normal level in subsequent years. The study also evaluated grain yields and water, energy, and carbon footprints generated from completing these engineering projects. The LCA was used to calculate the total water, energy, and carbon footprints generated during the material preparation, construction, and operation and maintenance phases of land consolidation projects (see Results).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article[and its supplementary information files]. Meteorological data used in the study, including temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and wind speed for the period 1986–2020, are from the National Meteorological Information Center of China through its Meteorological Data Sharing Service System. County-level agricultural data for the Loess Plateau (e.g., cultivated land area, fertilizer usage, grain yield, agricultural machinery usage, and irrigation status) are from provincial and municipal statistical yearbooks. Data on land consolidation projects, such as construction materials, project components, and workload estimates, are from the Master Plan for Comprehensive Management of the Loess Plateau. Carbon emission factors and energy intensity factors for each construction material are from the European Reference Life Cycle Database (ELCD), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the Ecoinvent database83. The remote sensing datasets used in this study include the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Globeland30 land cover dataset, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) products derived from Landsat 8 imagery. These datasets were processed using ArcGIS 10.8; steps included geometric correction, projection, and data extraction. Other statistical data were obtained through official data requests and online downloads from government departments. All data were standardized and subjected to spatial mapping and analysis. Socioeconomic data were harmonized at the county level for the Loess Plateau; environmental datasets were resampled or aggregated to a 10 km spatial resolution. After quality control of the meteorological series, short gaps were filled using linear/spline interpolation, while long gaps were spatially imputed with nearest-station IDW or thin-plate spline and then aggregated to growing-season and annual scales (with elevation lapse-rate adjustment during gridding). Landsat imagery was cloud/shadow masked using the QA\_PIXEL band, composited monthly, and summarized for the growing season. Globeland30 was reclassified to cropland and, together with DEM-derived topographic factors, resampled to 10 km resolution. Remote-sensing products were validated using confusion-matrix methods. County-level socioeconomic data were harmonized to a unified county boundary; administrative changes were handled via area-weighted backcasting; indicators were converted to per-capita or per-unit-arable-land terms and z-score standardized; finally, they were spatially matched to the 10 km environmental rasters via zonal statistics.

References

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010).

Schmidt-Traub, G. et al. National baselines for the sustainable development goals assessed in the SDG index and dashboards. Nat. Geosci. 10, 547–555 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Balancing green and grain trade. Nat. Geosci. 8, 739–741 (2015).

Pecl, G. T. et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 355, eaai9214 (2017).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Extreme climate events increase risk of global food insecurity and adaptation needs. Nat. Food 2, 587–595 (2021).

Hulme, M. et al. Framing the challenge of climate change in Nature and Science editorials. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 515–521 (2018).

Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG. Revised list of global Sustainable Development Goalindicators (2017).

Sela, S. et al. Towards a unified approach to prioritization of regenerative agricultural practices across cropping systems. npj Sustain. Agric. 2, 24 (2024).

Lesnikowski, A. et al. National-level progress on adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 261–264 (2016).

Fezzi, C. et al. The environmental impact of climate change adaptation on land use and water quality. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 255–260 (2015).

Rasul, G. & Sharma, B. The nexus approach to water–energy–food security: an option for adaptation to climate change. Clim. Policy 16, 682–702 (2016).

Gu, W. et al. Climate adaptation through crop migration requires a nexus perspective for environmental sustainability in the North China Plain. Nat. Food 5, 569–580 (2024).

Ringler, C., Bhaduri, A. & Lawford, R. The nexus across water, energy, land and food (WELF): Potential for improved resource use efficiency? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 617–624 (2013).

Liu, J. An integrated framework for achieving sustainable development goals around the world. Ecol. Econ. Soc. INSEE J. 1, 11–17 (2018).

Smajgl, A. & Ward, J. The Water-Food-Energy Nexus in the Mekong Region: Assessing Development Strategies Considering Cross-Sectoral and Transboundary Impacts (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Liu, J., Chen, S., Wang, H. & Chen, X. Calculation of carbon footprints for water diversion and desalination projects. Energy Procedia 75, 2483–2494 (2015).

Liu, Y., et al. Unequal impacts of global urban–rural settlement construction on cropland and production over the past three decades. Sci. Bull. 14, 1534 (2025).

Liu, Y. Modern human-earth relationship and human-earth system science. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 40, 1221–1234 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Framing sustainability in a telecoupled world. Ecol. Soc. 18, (2013).

Manning, N., Li, Y. & Liu, J. Broader applicability of the metacoupling framework than Tobler’s first law of geography for global sustainability: a systematic review. Geogr. Sustain. 4, 6–18 (2023).

Wu, X., Wang, S., Fu, B. & Liu, J. Spatial variation and influencing factors of the effectiveness of afforestation in China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 771, 144904 (2021).

Herzberger, A., Chung, M. G., Kapsar, K., Frank, K. A. & Liu, J. Telecoupled food trade affects pericoupled trade and intracoupled production. Sustainability 11, 2908 (2019).

Zhang, J., He, C., Huang, Q. & Li, L. Understanding ecosystem service flows through the metacoupling framework. Ecol. Indic. 151, 110303 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Synergies and tradeoffs among Sustainable Development Goals across boundaries in a metacoupled world. Sci. Total Environ. 751, 141749 (2021).

Dou, Y. et al. Understanding how smallholders integrated into pericoupled and telecoupled systems. Sustainability 12, 1596 (2020).

Chung, M. G., Herzberger, A., Frank, K. A. & Liu, J. International tourism dynamics in a globalized world: a social network analysis approach. J. Travel Res. 59, 387–403 (2019).

Abbass, K. et al. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 29, 42539–42559 (2022).

David Rolnick, P. L. et al. 2022. Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 2, Article 42, 96 pages (2023).

Rezaei, E. E. et al. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 831–846 (2023).

Dalin, C., Suweis, S., Konar, M., Hanasaki, N. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Modeling past and future structure of the global virtual water trade network. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L24402 (2012).

Fan, X., Zhang, W., Chen, W. W. & Chen, B. Land–water–energy nexus in agricultural management for greenhouse gas mitigation. Appl. Energ. 265, 114796 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nat. Sustain 1, 466–476 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. China’s environment on a metacoupled planet. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 1–34 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Spillover systems in a telecoupled Anthropocene: typology, methods, and governance for global sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 33, 58–69 (2018).

Schaffer-Smith, D. et al. Network analysis as a tool for quantifying the dynamics of metacoupled systems: an example using global soybean trade. Ecol. Soc. 23, 3 (2018).

Liu, J., Yang, W. & Li, S. Framing ecosystem services in the telecoupled Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 27–36 (2016).

Walker, R. V., Beck, M. B., Hall, J. W., Dawson, R. J. & Heidrich, O. The energy water-food nexus: strategic analysis of technologies for transforming the urban metabolism. J. Environ. Manag. 141, 104–115 (2014).

Li, Y., Li, Y., Fang, B., Wang, Q. & Chen, Z. Impacts of ecological programs on land use and ecosystem services since the 1980s: a case-study of a typical catchment on the Loess Plateau, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 33, 3271–3282 (2022).

Vora, N., Shah, A., Bilec, M. M. & Khanna, V. Food–energy–water nexus: quantifying embodied energy and GHG emissions from irrigation through virtual water transfers in food trade. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 2119–2128 (2017).

Van Valkengoed, A. M. & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 158–163 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Land use and landscape change driven by gully land consolidation project: a case study of a typical watershed in the Loess Plateau. J. Geograph. Sci. 29, 719–729 (2019).

Li, Y., Shi, Z., Wu, H., Li, F. & Li, H. Definition of management zones for enhancing cultivated land conservation using combined spatial data. Environ. Manag. 52, 792–806 (2013).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Liu, Y. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geograph. Sin. 73, 637–650 (2018).

FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TCL (2021).

Salmoral, G. & Yan, X. Food-energy-water nexus: a life cycle analysis on virtual water and embodied energy in food consumption in the Tamar catchment. Uk. Resour. Conserv. Recyc. 133, 320–330 (2018).

Long, H., Ma, L., Zhang, Y. & Qu, L. Multifunctional rural development in China: Pattern, process and mechanism. Habitat Int. 121, 102530 (2022).

Long, H., Zou, J., Li, T. & Liu, Y. Study on the characteristics and territorial types of rural transformation development: The case of “Southern Jiangsu-Northern Shanghai” transect. Geograph. Res. 31, 495–506 (2012).

Wheeler, T. & von Braun, J. Climate change impacts on global food security. Science 341, 508–513 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Towards the progress of ecological restoration and economic development in China’s Loess Plateau and strategy for more sustainable development. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 143676 (2021).

Gao, P. et al. Heterogeneous pressure on croplands from land-based strategies to meet the 1.5 °C target. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 420–427 (2025).

Gao, Y. et al. Cost-effective adaptations increase rice production while reducing pollution under climate change. Nat. Food 6, 260–272 (2025).

Nechifor, V. & Ferrari, E. Trading for climate resilience. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 804–805 (2020).

Liu, B. & Yang, Y. Large benefits of timely planting. Nat. Food 3, 495–496 (2022).

Liu, Y., Liu, X. & Liu, Z. Effects of climate change on paddy expansion and potential adaption strategies for sustainable agriculture development across Northeast China. Appl. Geogr. 141, 102667 (2022).

Niu, K. et al. Impacts of global trade on cropland soil-phosphorus depletion and food security. Nat. Sustain 7, 1128–1140 (2024).

Fuldauer, L. I. et al. Targeting climate adaptation to safeguard and advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 13, 3579 (2022).

Liu, Y., Fang, F. & Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 40, 6–12 (2014).

Zecca, F. & Saima, S. Pastoralism and women’s role in food security in the Ethiopian Somali region. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 371 (2025).

Liu, Y. & Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 548, 275–277 (2017).

Li, Y., Li, Y., Fan, P. & Long, H. Impacts of land consolidation on rural human-environment system in typical watershed of the Loess Plateau and implications for rural development policy. Land Use Policy 86, 339–350 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Synergies and tradeoffs among sustainable development goals across boundaries in a metacoupled world. Sci. Total Environ. 751, 141749 (2020).

Hultgren, A. et al. Impacts of climate change on global agriculture accounting for adaptation. Nature 642, 644–652 (2025).

White, D. J., Hubacek, K., Feng, K., Sun, L. & Meng, B. The water-energy-food nexus in East Asia: a tele-connected value chain analysis using inter-regional input output analysis. Appl. Energy 210, 550–567 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Prediction of aboveground grassland biomass on the Loess Plateau, China, using a random forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 7, 6940 (2017).

Li, X., Zhang, D., Zhang, T., Ji, Q. & Lucey, B. Awareness, energy consumption and pro-environmental choices of Chinese households. J. Clean. Prod. 279, 123734 (2021).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Requirements. Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56 (Food and Agriculture Organization, 1998).

Xue, J. et al. Quantification of wheat water footprint based on data assimilation of remote sensing and WOFOST model. Agr. For. Meteorol. 347, 109914 (2024).

Liu, J. Integration across a metacoupled world. Ecol. Soc. 22, 29 (2017).

Xu, Z. et al. Impacts of irrigated agriculture on food-energy-water-CO2 nexus across metacoupled systems. Nat. Commun. 11, 5837 (2020).

Pacetti, T., Lombardi, L. & Federici, G. Water–energy Nexus: a case of biogas production from energy crops evaluated by Water Footprint and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methods. J. Clean. Prod. 101, 278–291 (2015).

Zhuo, D., Liu, L. M., Yu, H. R. & Yuan, C. C. A national assessment of the effect of intensive agro-land use practices on nonpoint source pollution using emission scenarios and geo-spatial data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 25, 1683–1705 (2018).

Moore, F. C. et al. New science of climate change impacts on agriculture implies higher social cost of carbon. Nat. Commun. 8, 1607 (2017).

Xia, J., Mo, X. G., Wang, J. X. & Luo, X. P. Impacts of climate change and adaptation in agricultural water management in North China. Cabi Clim. Change Ser. 8, 63–77 (2016).

Liu, Z., Liu, Y. & Li, Y. Extended warm temperate zone and opportunities for cropping system change in the Loess Plateau of China. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 658–669 (2019).

Wang S., et al. Anthropogenic impacts on the Yellow River Basin. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1-16(2025).

Feng, W., Liu, Y., Chen, Z., Li, Y. & Huang, Y. Theoretical and practical research into excavation slope protection for agricultural geographical engineering in the Loess Plateau: a case study of China’s Yangjuangou catchment. J. Rural Stud. 93, 309–317 (2022).

Tian, P. et al. Response of soil erosion to vegetation restoration and terracing on the Loess Plateau. Catena, 227, 107103(2023).

He, M. et al. Evaluation of the environmental effects of intensive land consolidation: a field-based case study of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Land use policy 94, 104523 (2020).

Zhao, Z. G., Qin, X., Wang, Z. M. & Wang, E. L. Performance of different cropping systems across precipitation gradient in North China Plain. Agr. Meteorol. 259, 162–172 (2018).

Fan, S., Lay, S., Yu, H. & Shen, S. Dietary guidelines for Chinese residents (2016): evaluation and comparison. J. Zhejiang Univ. -Sci. B 17, 649–656 (2016).

Hess, T., Andersson, U., Mena, C. & Williams, A. The impact of healthier dietary scenarios on the global blue water scarcity footprint of food consumption in the UK. Food Policy 50, 1–10 (2015).

Wernet, G. et al. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21, 1218–1230 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42293270; 42401259; 42101202), and Chongqing Social Science Planning Project (2025NDYB075).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Q. and Y.L. designed the research study. Y.Z., L.Q. and X.L. performed the analyses, with additional support from X.L. for the metacoupled-analysis. L.Q., and Y.Z. produced the figures and wrote the original draft; L.Q. and Y.L. further revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, L., Zhang, Y., Liu, X. et al. Impacts of climate adaptation on food production and environmental sustainability across metacoupling systems. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 20 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-026-00129-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-026-00129-w