Abstract

The relationship between obesity and the development of cardiovascular disease is well established. However, the underlying mechanisms contributing to vascular disease and increased cardiovascular risk in the obese remain largely unexplored. Since leptin exerts direct vascular effects, we investigated leptin and the relationship thereof with circulating markers of vascular damage, namely plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen (PAI-1ag), von Willebrand factor antigen (vWFag) and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). The study included a bi-ethnic population of 409 African and Caucasian teachers who were stratified into lean (<0.5) and obese (⩾0.5) groups according to waist-to-height ratio. We obtained ambulatory blood pressure measurements and determined serum leptin levels, PAI-1ag, vWFag and ACR, as markers of vascular damage. The obese group had higher leptin (P<0.001) and PAI-1ag (P<0.001) levels and a tendency existed for higher vWFag (P=0.068). ACR did not differ between the two groups (P=0.21). In single regression analyses positive associations existed between leptin and all markers of vascular damage (all P<0.001) only in the obese group. After adjusting for covariates and confounders in multiple regression analyses, only the association between leptin and PAI-1ag remained (R2=0.440; β=0.293; P=0.0021). After adjusting for gender, ethnicity and age, additional analyses indicated that leptin also associated with fibrinogen and clot lysis time in both lean and obese groups, which in turn is associated with 24- h blood pressure and pulse pressure. This result provides evidence that elevated circulating leptin may directly contribute to vascular damage, possibly through mechanism related to thrombotic vascular disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in sub-Saharan Africa.1 This increase may be attributed to Westernization which usually coincides with unhealthy dietary habits and a sedentary lifestyle.2 Obesity often predisposes the development of hypertension,3 and obesity-related hypertension is now considered a distinct hypertensive phenotype.4 Endothelial damage is one of many mechanisms linking obesity to cardiovascular disease5 and in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that leptin may be involved.6, 7

Physiological leptin levels promote nitric oxide production and endothelium-dependent relaxation by inducing nitric oxide synthase expression.8 Contrastingly, in pathological conditions such as obesity and related hyperleptinemia, the leptin-mediated production of nitric oxide seems impaired and thereby contributes to endothelial dysfunction and damage.6, 9 Assessment of circulating biomarkers of vascular damage may provide valuable information of the mechanisms at work. A damaged endothelium promotes the secretion of pro-thrombotic factors such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-110 and von Willebrand factor11 and results in leakage of albumin in urine as reflected by the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio.12

We therefore investigated leptin and the associations thereof with plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, von Willebrand factor and albumin-to-creatinine ratio as markers of vascular damage in a bi-ethnic sample of 409 teachers.

Methods

Study design

This study forms part of the Sympathetic activity and Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Africans study, which included 409 African and Caucasian school teachers working in the Potchefstroom district in the North-West Province of South Africa. The reason for the selection of this target population was to obtain a homogenous sample of participants from a similar socioeconomic class. Participants between the ages of 25 and 60 years were included. The exclusion criteria were a tympanic temperature above 37 °C, psychotropic substance dependence or abuse, regular blood donors and individuals vaccinated in the past three months. Participants received detailed information about the procedures and objectives of the study prior to their recruitment. All participants signed an informed consent form. The study complied with all applicable requirements and international regulations, including the Helsinki declaration of 1975 (as revised in 2008) for investigation of human participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus).

Cardiovascular measurements

Ambulatory blood pressure measurements (ABPM) were taken during the working week. At approximately 08h00, an ABPM apparatus (Meditech CE120 Cardiotens; Meditech, Budapest, Hungary) and two-lead ECG were attached on the participant’s non-dominant arm at their workplace. The ABPM apparatus was programmed to measure blood pressure at 30 min intervals during the day (0800–2200 h) and every hour during night time. Participants received ambulatory diary cards and were requested to indicate abnormalities such as nausea, headache or stress experienced during their normal daily activities. At 1630 h, participants were transported to the North-West University and admitted to the Metabolic Unit Research Facility. This facility consists of ten bedrooms, two bathrooms, a living room and a kitchen. Participants received a standardized dinner and at 2030 h they received their last beverage (coffee/tea and two biscuits). Thereafter they relaxed by reading, watching television or social interaction and were encouraged to go to bed at 2200 h. Participants were requested to refrain from alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption and exercise. At 0600 h, the ABPM apparatus was removed and subsequent measurements commenced. Electrocardiogram and 24 h blood pressure data were downloaded onto a database by using the CardioVisions 1.15.2 Personal Edition (Meditech, Budapest, Hungary). If <70% of the ABPM recordings for a particular participant were successful, the measurement was repeated the next day. The Actical activity monitor (Mini Mitter, Bend, OR, USA; Montreal, QC, Canada) was used to estimate physical activity. The monitor was fitted after all cardiovascular measurements were taken and worn around the waist by participants for 24 h. The physical activity index of participants was categorised according to high, moderate and low physical activity.

Anthropometric measurements

Height (stature), weight and waist circumference of participants were measured while being in their underwear by using calibrated instruments (Precision Health Scale, A & D Company, Tokyo, Japan; Invicta Stadiometer, IP 1465, London, UK). All measurements were taken in triplicate using standard methods.13 Subsequently, the body mass index and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) were calculated for each participant. We used a WHtR value of 0.5 as cutoff based on recent studies confirming the usefulness of this measurement.14

Biochemical measurements

After the cardiovascular and anthropometric measurements were completed, a registered nurse drew a fasting blood sample with a sterile winged infusion set from the antebrachial vein branches. EDTA whole blood and serum were stored at −80 °C. In serum, fasting samples for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose, γ-glutamyl transferase and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein were analyzed by using two sequential multiple analyzers (Konelab 20i TM, Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland; Unicel DxC 800; Beckman and Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). We determined leptin levels using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, MN, USA) and citrate von Willebrand antigen (vWFag) levels with a ‘sandwich’ ELISA assay. A polyclonal rabbit anti-vWF antibody and a rabbit anti-vWF-HRP antibody (DAKO, Johannesburg, South Africa) were used to form the assay. The 6th International Standard for vWF/FVII was used to create the standard curve against which the samples were measured.15 Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen (PAI-1ag) levels were determined with triniLIZE PAI-1 (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) antigen kit using ELISA. Plasma fibrinogen levels were determined with a viscosity-based clotting method using the STAGO FIB kit (STAGO diagnostics, Asnières, France). Clot lysis time (CLT) was determined by studying the lysis of a tissue factor-induced clot by exogenous tissue-plasminogen activator (t-PA). Changes in turbidity during clot formation and lysis were monitored as described by Lisman et al.16 Tissue factor and t-PA concentrations were slightly modified to obtain comparable CLTs of ~60 min. The modified concentrations were 17 mmol l−1 CaCl, 60 ng ml−1 t-PA (Actilyse, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) and 10 μmol l−1 phospholipids vesicles (Rossix, Mölndal, Sweden). Tissue factor was diluted 3000 times (Dade Innovin, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). CLT was defined as the time from the midpoint in the transition from the initial baseline to maximum turbidity, which is representative of clot formation, to the midpoint in the transition from maximum turbidity to the final baseline turbidity, which represents the lysis of the clot.

In urine, creatinine was determined with a calorimetric method and albumin with the measurement of immunoprecipitation enhanced by polyethylene glycol at 450 nm, with two sequential multiple analyzers (Konelab 20i TM, Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland Unicel DxC 800; Beckman and Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) with a coefficient variation of 1.7–3.3%. Albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) measured in an 8- h overnight urine sample is highly correlated with 24- h urinary albumin excretion.17, 18

Statistical analysis

For database management and statistical analyses, we used Statistica software version 12.0 (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA, 2010). A WHtR of 0.5 was used to categorise our study population into lean (<0.5) and obese (⩾0.5) individuals. A power calculation was performed and it was found that sample sizes of 127 and 282 participants are sufficient to determine biological differences of leptin and PAI-1ag concentrations, at a significance level of P=0.05 and a power of 99%. The distribution of leptin, ACR, glucose, C-reactive protein and γ-glutamyl transferase were normalized by a logarithmic transformation. The central tendency and spread of these variables were represented by the geometric mean and the 5th and 95th percentile intervals. Independent t-tests were done to compare means between groups and the χ2-test to compare proportions. We used Pearson’s correlations to investigate associations between markers of vascular damage and leptin and illustrated by scatterplots. We also performed partial correlations by adjusting for ethnicity, gender and age. Adjusted mean values of leptin were plotted by quartiles of PAI-1ag. Multiple regression analyses were performed to investigate independent associations, while adjusting for ethnicity, gender, age, WHtR, 24 h systolic blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein-to-total cholesterol ratio, serum glucose, C-reactive protein, current smoking, γ-glutamyl transferase, physical activity level and the use of anti-hypertensive medication.

Results

Comparison of lean and obese participants

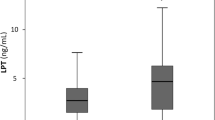

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study population stratified by WHtR. Leptin levels, 24- h systolic and diastolic blood pressure (all P<0.001) were all higher in the obese group compared with the lean group. The obese group had higher PAI-1ag (P<0.001) and a tendency for higher vWF (P=0.068), but no difference existed between the lean and obese groups for ACR (P=0.21).

Single and partial regression analyses

In single regression analyses (Figure 1), we found positive associations of PAI-1ag, vWFag and ACR with leptin (P<0.001) only in the obese group. After adjusting for ethnicity, gender and age, the association between PAI-1ag and leptin (r=0.18; P=0.002) remained, while the significant associations with vWFag (r=0.03; P=0.58) and ACR (r=0.08; P=0.20) in the obese group were lost. In exploratory analyses (Figure 2), we plotted PAI-1ag by quartiles of leptin after additionally adjusting for WHtR, confirming the positive association between PAI-1ag and leptin (P for trend=0.015) in the obese.

Single regression analyses of markers of vascular damage with leptin in the respective lean and obese groups. Solid and dashed lines represent the regression line and the 95% CI boundaries. ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; PAI-1ag, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen; vWFag, von Willebrand factor antigen.

Multiple regression analyses

The independent associations between PAI-1ag, vWFag, ACR and leptin in the respective WHtR groups are presented in Table 2. After adjusting for confounders, the above association between PAI-1ag and leptin in the obese group was confirmed (ß=0.293; P=0.0021). We also repeated the analyses in the obese Africans and Caucasians separately (Supplementary Table S1). By doing so, the relationship between PAI-1ag and leptin remained in the obese Caucasians (Adj R2=0.198; ß=0.321; P=0.042) and a similar tendency was seen in the obese Africans (Adj R2=0.037; ß=0.303; P=0.057).

Additional analyses

Because of the fact that we only found associations between PAI-1ag and leptin, we investigated whether leptin associates with markers of thrombotic vascular disease. After adjusting for ethnicity, gender and age, we found positive associations of fibrinogen and clot lysis time with leptin in the lean (r=0.33; P<0.001, r=0.28; P=0.002) and obese groups (r=0.24; P<0.001, r=0.32; P<0.001). Additionally, fibrinogen (r=0.20; P=0.030) and clot lysis time (r=0.19; P=0.045) were positively associated with 24- h pulse pressure in the lean group, whereas positive associations were seen between clot lysis time, 24- h systolic blood pressure (r=0.17; P=0.006) and 24- h pulse pressure (r=0.14; P=0.028) in the obese group.

Discussion

We explored the relationship between PAI-1ag, vWFag, ACR and leptin, and found a positive association between PAI-1ag and leptin in obese participants, independent of WHtR and blood pressure. Additional analyses indicated that instead of relating to vWFag and ACR as more structural markers of endothelial damage, leptin rather related, in addition to PAIag, to fibrinogen and clot lysis time, which in turn related to 24- h systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure, suggesting a potential role of leptin in thrombotic vascular disease.

Few studies addressed the relationship between leptin and circulating markers of vascular damage. Previous studies that support the association between PAI-1ag and leptin are limited and lack adjustment for ambulatory blood pressure19 and C-reactive protein,20 which are known to be related to PAI-1ag and leptin.21 In 74 hypertensive overweight individuals, leptin correlated positively with PAI-1, but the association disappeared after correcting for body mass index.22 In agreement with our finding, a study by Mertens et al.,23 consisting of 280 overweight and obese participants, found a positive association between leptin and PAI-1 activity independent of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue, percentage fat mass and insulin resistance. An independent association between PAI-1ag and leptin was also demonstrated in 61 non-diabetic women.24 A study on obese children showed no relationship between PAI-1ag and leptin; however, this relationship may not be established yet.25

The absence of associations of vWFag and ACR with leptin contradicts previous studies. The study by Mertens et al.23 also showed an association between vWFag and leptin, but only in men. Furthermore, positive associations between leptin and vWFag were found in 3640 overweight men26 and 51 obese women.27 In the latter study it was suggested that inflammation may be the mechanistic link between leptin and vWFag. However, the potential confounding effect of inflammation and blood pressure was not taken into consideration by the authors. When we included C-reactive protein as inflammatory marker in multiple regression analyses the relationship between vWFag and leptin did indeed seem confounded by C-reactive protein.

Regarding albuminuria, a positive association between urinary albumin and leptin was observed in chronic kidney disease patients.28 Results from the Framingham Heart Study showed that visceral adipose tissue was associated with microalbuminuria in men of which 30% were obese, but the authors did not investigate leptin.29 In a study on non-diabetic black Africans, leptin as well as ACR levels were higher in participants with four or more components of the metabolic syndrome compared with those without.30 However, associations between leptin and ACR were not reported.

Our main finding is therefore the independent association between PAI-1ag and leptin in obese individuals. The pathway(s) by which leptin may induce PAI-1 secretion remains undefined. Experimental studies provide evidence of a possible direct stimulatory effect of leptin. Incubation of human endothelial cells with leptin at concentrations greater than 50 ng ml−1 stimulates PAI-1 protein expression.31 Singh et al.31 suggested that the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 pathway may be involved. We recently demonstrated in this population group that a hyperleptinemic state is associated with sympathetic overactivity.32 Stimulation of sympathetic nerve activity by leptin may be a potential indirect pathway by which leptin promotes PAI-1 secretion.6 Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system activates PAI-1 gene expression through the α-adrenergic receptor.33 In addition, leptin may also stimulate PAI-1 secretion by inducing oxidative stress34, 35 and inflammation.36 Additional analyses after adjusting for ethnicity, gender and age, also demonstrated that leptin is associated with fibrinogen and clot lysis time and these hemostatic variables in turn associated with 24- h systolic and pulse pressure. The lack of associations with vWFag, and ACR may suggest that leptin does not directly induce vascular damage per se, but rather a pro-thrombotic state leading to thrombotic vascular diseases. The independent association in this study and the in vitro findings of Singh et al.31 suggests that leptin may directly stimulate PAI-1 secretion, but this seems to be activated only in obese and/or hyperleptinemic conditions. Consequently, PAI-1 may then contribute to vascular disease by inhibiting fibrinolysis.36

One could speculate on the absence of associations between, vWFag, ACR and leptin. vWF is secreted by endothelial cells either to act as an acute phase protein37 or to initiate platelet adhesion at sites of vascular injury.38 Endothelial damage will also contribute to vascular permeability and not the other way around.39 Therefore, albuminuria is preceded by a damaged endothelium and may not be as a direct result of elevated leptin. We therefore propose that leptin may directly contribute to changes by inducing PAI-1 secretion and a resultant pro-thrombotic pathway. However, if obesity is left unopposed, chronic exposure of endothelial cells to leptin and other cardiometabolic risk factors will take effect, and vascular damage may progress to the extent where the damaged endothelium secretes vWF38 and permit the movement of macromolecules such as albumin through the endothelial layer.39

Globally, obesity and related cardiovascular disease are reaching alarming proportions. Given the disruptive effect of obesity on the cardiovascular and endocrine systems,40, 41 studies aimed at identifying the mechanistic links between leptin and vascular alterations in the obese are of clinical relevance. These studies may provide the necessary information to appropriately treat and delay vascular alterations which is regarded as an early step in the development of cardiovascular disease.

This study has to be interpreted within the context of its limitations and strengths. This cross-sectional study investigated the associations between leptin and markers of vascular damage, and we therefore cannot infer causality. While our results were consistent after multiple adjustments, we cannot exclude the possibility that our associations were due to residual confounding. The possibility exists that vascular alterations could occur due to obesity and that leptin is only elevated as a consequence of obesity? However, we adjusted for a marker of obesity in order to demonstrate a potential direct effect of leptin on vascular alteration or damage independent of obesity. This was a specific target population study; therefore, results cannot be extrapolated to the general population. We did not account for gene mutations and genetic factors such as ABO blood groups which influence vWF levels.42 Further, we were unable to correct for muscle mass and lack sufficient dietary data to report on factors which may influence creatinine excretion. Additionally, we do not have the necessary data to investigate the potential influence of the menstrual cycle on circulating levels of leptin, PAI-1ag, vWFag and ACR. However, our main result remains robust after additional adjustment for estrogen and progesterone in multiple regression analyses (P<0.01). In general, we conducted a well-designed study under controlled conditions.

To conclude, our results show a positive association between PAI-1ag and leptin in obese humans, alluding to the mechanistic link between cardiovascular disease and obesity, possibly through leptin promoting thrombotic vascular disease. Given the global burden of cardiovascular disease, experimental studies should be aimed at the benefits of treating leptin resistance in the obese to decrease cardiovascular risk.

References

Van Der Merwe MT, Pepper M . Obesity in South Africa. Obes Rev 2006; 7: 315–322.

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW . Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 2012; 70: 3–21.

Hall JE, da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion J, Hamza S, Munusamy S, Smith G, Stec DE . Obesity-induced hypertension: role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 17271–17276.

Kotchen TA . Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Am J Hypertens 2010; 23: 1170–1178.

Grassi G, Seravalle G, Scopelliti F, Dell'Oro R, Fattori L, Quarti‐Trevano F, Brambilla G, Schiffrin EL, Mancia G . Structural and functional alterations of subcutaneous small resistance arteries in severe human obesity. Obesity 2010; 18: 92–98.

Wang J, Wang H, Luo W, Guo C, Wang J, Chen YE, Chang L, Eitzman DT . Leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction is mediated by sympathetic nervous system activity. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000299.

Payne G, Tune J, Knudson J . Leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction: a target for therapeutic interventions. Curr Pharm Des 2014; 20: 603–608.

Vecchione C, Maffei A, Colella S, Aretini A, Poulet R, Frati G, Gentile MT, Fratta L, Trimarco V, Trimarco B . Leptin effect on endothelial nitric oxide is mediated through Akt–endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation pathway. Diabetes 2002; 51: 168–173.

Korda M, Kubant R, Patton S, Malinski T . Leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295: H1514–H1521.

Brodsky SV, Malinowski K, Golightly M, Jesty J, Goligorsky MS . Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes formation of endothelial microparticles with procoagulant potential. Circulation 2002; 106: 2372–2378.

Felmeden D, Blann A, Spencer CG, Beevers D, Lip GY . A comparison of flow-mediated dilatation and von Willebrand factor as markers of endothelial cell function in health and in hypertension: relationship to cardiovascular risk and effects of treatment A substudy of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial. Blood Coagulation Fibrinol 2003; 14: 425–431.

Malik A, Sultan S, Turner S, Kullo I . Urinary albumin excretion is associated with impaired flow-and nitroglycerin-mediated brachial artery dilatation in hypertensive adults. J Hum Hypertens 2007; 21: 231–238.

Norton K, Olds T . Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Body Measurement for Sports and Health Courses. University of New South Wales Press: New South Wales. 1996.

Browning LM, Hsieh SD, Ashwell M . A systematic review of waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for the prediction of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: 0·5 could be a suitable global boundary value. Nutr Res Rev 2010; 23: 247–269.

Meiring M, Badenhorst PN, Kelderman M . Performance and utility of a cost-effective collagen-binding assay for the laboratory diagnosis of Von Willebrand disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 2007; 45: 1068–1072.

Lisman T, de Groot PG, Meijers JC, Rosendaal FR . Reduced plasma fibrinolytic potential is a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Blood 2005; 105: 1102–1105.

Dyer AR, Greenland P, Elliott P, Daviglus ML, Claeys G, Kesteloot H, Chan Q, Ueshima H, Stamler J . Estimating laboratory precision of urinary albumin excretion and other urinary measures in the International Study on Macronutrients and Blood Pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 160: 287–294.

Bakker A . Detection of microalbuminuria. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis favors albumin-to-creatinine ratio over albumin concentration. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 307–313.

Poli KA, Tofler GH, Larson MG, Evans JC, Sutherland PA, Lipinska I, Mittleman MA, Muller JE, D'Agostino RB, Wilson PW, Levy D . Association of blood pressure with fibrinolytic potential in the Framingham offspring population. Circulation 2000; 101: 264–269.

Devaraj S, Xu DY, Jialal I . C-reactive protein increases plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression and activity in human aortic endothelial cells: implications for the metabolic syndrome and atherothrombosis. Circulation 2003; 107: 398–404.

Abramson JL, Lewis C, Murrah NV . Body mass index, leptin, and ambulatory blood pressure variability in healthy adults. Atherosclerosis 2011; 214: 456–461.

Skurk T, Van Harmelen V, Lee Y, Wirth A, Hauner H . Relationship between IL-6, leptin and adiponectin and variables of fibrinolysis in overweight and obese hypertensive patients. Horm Metab Res 2002; 34: 659–663.

Mertens I, Considine RV, Van der Planken M, Van Gaal LF . Hemostasis and fibrinolysis in non-diabetic overweight and obese men and women. Is there still a role for leptin? Eur J Endocrinol 2006; 155: 477–484.

De Mitrio V, De Pergola G, Vettor R, Marino R, Sciaraffia M, Pagano C, Scaraggi FA, Di Lorenzo L, Giorgino R . Plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-I is associated with plasma leptin irrespective of body mass index, body fat mass, and plasma insulin and metabolic parameters in premenopausal women. Metab Clin Exp 1999; 48: 960–964.

Sudi KM, Gallistl S, Weinhandl G, Muntean W, Borkenstein MH . Relationship between plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen, leptin, and fat mass in obese children and adolescents. Metab Clin Exp 2000; 49: 890–895.

Wannamethee SG, Tchernova J, Whincup P, Lowe G, Kelly A, Rumley A, Wallace AM, Sattar N . Plasma leptin: associations with metabolic, inflammatory and haemostatic risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2007; 191: 418–426.

Guagnano M, Romano M, Falco A, Nutini M, Marinopiccoli M, Manigrasso M, Basili S, Davi G . Leptin increase is associated with markers of the hemostatic system in obese healthy women. J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1: 2330–2334.

Mills KT, Hamm LL, Alper AB, Miller C, Hudaihed A, Balamuthusamy S, Chen C, Liu Y, Tarsia J, Rifai N . Circulating Adipocytokines and Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e76902.

Foster MC, Hwang S, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, DeBoer IH, Robins SJ, Vasan RS, Fox CS . Association of subcutaneous and visceral adiposity with albuminuria: the Framingham Heart Study. Obesity 2010; 19: 1284–1289.

Okpechi IG, Pascoe MD, Swanepoel CR, Rayner BL . Microalbuminuria and the metabolic syndrome in non-diabetic black Africans. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2007; 4: 365–367.

Singh P, Peterson TE, Barber KR, Kuniyoshi FS, Jensen A, Hoffmann M, Shamsuzzaman AS, Somers VK . Leptin upregulates the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 392: 47–52.

Pieterse C, Schutte R, Schutte AE . Autonomic activity and leptin in Africans and whites: the SABPA study. J Hypertens 2014; 32: 826–833.

Miskin R, Abramovitz R . Enhancement of PAI-1 mRNA in cardiovascular cells after kainate injection is mediated through the sympathetic nervous system. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2005; 38: 715–722.

Bouloumie A, Marumo T, Lafontan M, Busse R . Leptin induces oxidative stress in human endothelial cells. FASEB J 1999; 13: 1231–1238.

Cheng J, Chao Y, Wung B, Wang D . Cyclic strain-induced plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) release from endothelial cells involves reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996; 225: 100–105.

Iwaki T, Urano T, Umemura K . PAI‐1, progress in understanding the clinical problem and its aetiology. Br J Haematol 2012; 157: 291–298.

Pottinger B, Read R, Paleolog E, Higgins P, Pearson J . von Willebrand factor is an acute phase reactant in man. Thromb Res 1989; 53: 387–394.

Vischer U . von Willebrand factor, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4: 1186–1193.

Satchell S, Tooke J . What is the mechanism of microalbuminuria in diabetes: a role for the glomerular endothelium? Diabetologia 2008; 51: 714–725.

Eppel GA, Armitage JA, Eikelis N, Head GA, Evans RG . Progression of cardiovascular and endocrine dysfunction in a rabbit model of obesity. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 588–595.

Cooper JN, Fried L, Tepper P, Barinas-Mitchell E, Conroy MB, Evans RW, Brooks MM, Woodard GA, Sutton-Tyrrell K . Changes in serum aldosterone are associated with changes in obesity-related factors in normotensive overweight and obese young adults. Hypertens Res 2013; 36: 895–901.

van Loon J, Kavousi M, Leebeek F, Felix J, Hofman A, Witteman J, de MAAT M . von Willebrand factor plasma levels, genetic variations and coronary heart disease in an older population. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10: 1262–1269.

Acknowledgements

The Sympathetic Activity and Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Africans study would not have been possible without the voluntary collaboration of the participants and the Department of Education, North-West province, South Africa. We acknowledge the technical assistance of Mrs Tina Scholtz, Sr. Chrissie Lessing and Dr Szabolcs Péter. We also acknowledge the contribution of Prof Muriel Meiring for the vWF analyses. This work was partially supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa; the Medical Research Council, South Africa; the North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa; and the Metabolic Syndrome Institute, France. Any opinion, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and therefore the NRF do not accept any liability in regard thereto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Hypertension Research website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pieterse, C., Schutte, R. & Schutte, A. Leptin links with plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human obesity: the SABPA study. Hypertens Res 38, 507–512 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2015.28

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2015.28

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Elevated leptin and decreased adiponectin independently predict the post-thrombotic syndrome in obese and non-obese patients

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Relations of body weight status in early adulthood and weight changes until middle age with hypertension in the Chinese population

Hypertension Research (2016)